Abstract

Convergent evolution is central to the study of adaptation and has been used to understand both the limits of evolution and the diverse patterns and processes which result in adaptive change. Resistance to snake venom alpha-neurotoxins (αNTXs) is a case of widespread convergence having evolved several times in snakes, lizards and mammals. Despite extreme toxicity of αNTXs, substitutions in its target, the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR), prevent αNTX binding and render species resistant. Recently, the published meerkat (Herpestidae) genome revealed that meerkats have the same substitutions in nAChR as the venom-resistant Egyptian mongoose (Herpestidae), suggesting that venom-resistant nAChRs may be ancestral to Herpestids. Like the mongoose, many other species of feliform carnivores prey on venomous snakes, though their venom resistance has never been explored. To evaluate the prevalence and ancestry of αNTX resistance in mammals, we generate a dataset of mammalian nAChR using museum specimens and public datasets. We find five instances of convergent evolution within feliform carnivores, and an additional eight instances across all mammals sampled. Tests of selection show that these substitutions are evolving under positive selection. Repeated convergence suggests that this adaptation played an important role in the evolution of mammalian physiology and potentially venom evolution.

Keywords: neurotoxins, convergent evolution, coevolution, venom resistance, tests of selection, ancestral reconstruction

1. Introduction

Convergent evolution has offered insight into the ways in which diverse organisms evolved to cope with similar selective pressures [1,2]. Within mammals, venom resistance has convergently evolved in marsupials, rodents, carnivores, eulypotyphlans and artiodactyls [3–9]. Old world mammals which prey upon and sustain bites from venomous snakes in the family Elapidae face envenomation with deadly alpha-neurotoxins (αNTXs, specifically three-finger toxins), which bind to the α1 domain of the muscular nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR), blocking nerve–muscle communication and causing rapid muscular paralysis and death. Despite this, the Egyptian mongoose, honey badger, domestic pig and hedgehogs regularly prey on Elapids and have convergently evolved mutations in their nAChRs which confer resistance to αNTXs and experience strong positive selection [3,10].

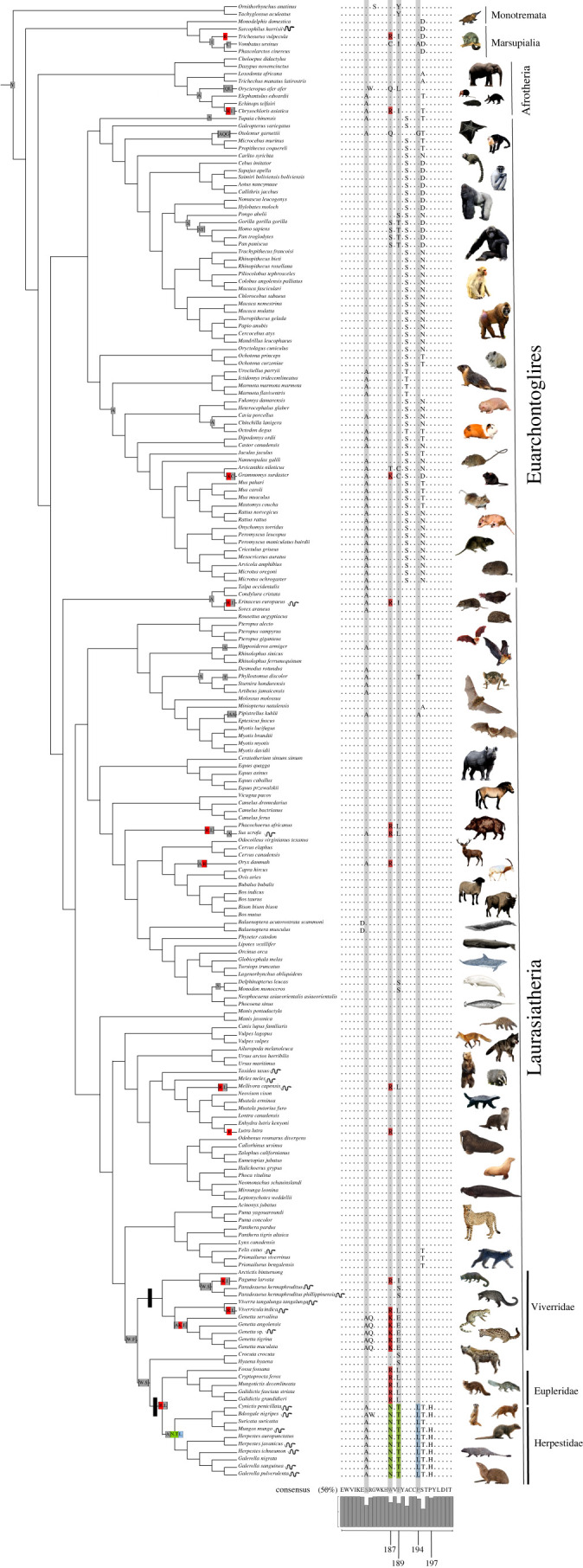

Mutations associated with αNTX resistance in mammals occur at four sites in the nAChR epitope, and function via three distinct biophysical mechanisms [9]. The first two sites 187 and 189, are aromatic amino acids (W187, F189) in most mammals, and directly interact with αNTX. Resistance at these sites is present either via steric hindrance mediated by a glycosylation (N187, T189) in mongooses or via arginine-mediated electrostatic repulsion (R187) in honey badgers, hedgehogs and pigs. The second two sites involved in mammalian resistance, 194 and 197 are prolines in most mammals, are necessary for αNTX binding, and replacement of either (e.g. P194 to L194, P197 to H197 in the Egyptian mongoose) results in the loss of αNTX binding [9]. Extensive experimental work has validated the function of these substitutions in diverse genetic backgrounds [10–20]. Hereafter, we refer to these mechanisms as electrostatic repulsion resistance, glycosylation resistance and proline resistance, respectively.

Other species of mongooses and meerkats in the same family (Herpestidae) are well-known to exhibit lack-of-avoidance, cooperative mobbing and predation upon venomous snakes (figure 1, electronic supplementary material, table S3) [7,9,10,22]. The newly published meerkat genome (GCA_006229205.1) reveals that meerkats share the same changes as the Egyptian mongoose (i.e. N187, T189 and L194) and likely enjoy the same protective glycosylation and partial proline-mediated resistance. αNTX resistance in related species of African feliform carnivores remains unexplored, including in the families Eupleridae (Malagassy carnivores) and Viverridae (civet cats), the latter of which contains many species that exhibit predatory and/or aggressive behaviour towards venomous snakes (figure 1; electronic supplementary material, table S3) [23]. While their ecology, biogeography and relatedness to resistant taxa suggest that snake venom may be an important selective pressure for many species in Herpestidae, Eupleridae and Viverridae, it is unknown if they are resistant to αNTX, and whether resistance is the result of an ancient adaptation at the base of these three clades or has evolved convergently in response to repeated selection pressure for venom resistance.

Figure 1.

The evolutionary tree of mammals showing the relationships between species for which the nAChR α1 subunit epitope was available. The nAChR epitope alignment from sites 175–198 is displayed for each species with dots denoting amino acids that do not differ from the consensus. Designated foreground clades (Herpestidae, Viverridae and Eupleridae) are marked with black rectangles. Sites highlighted in grey rectangles indicate signatures of positive selection in these clades (table 2). Mutations known to confer resistance are reconstructed onto their corresponding branches in colour based on the mechanism of resistance: electrostatic repulsion via a positively charged replacement (R or K) at site 187 is marked in red, steric hindrance via a glycosylation indicated by an N-T replacement at sites 187/189 is marked in green and replacement of prolines 194 and/or 197 (proline resistance) is marked in blue. Changes at functional and selected sites are mapped onto branches of the tree using a maximum-likelihood-based codon model ancestral state reconstruction [21]. Species known to prey on venomous snakes are denoted with a snake icon (citations and summary of interactions in electronic supplementary material, table S3).

To examine the evolution of αNTX resistance across these clades, we leveraged an exhaustive search of museum tissue samples from all species available from North American museums for Eupleridae, Viverridae and Herpestidae and sequenced the muscular nAChR. We also used bioinformatic searches to identify muscular nAChR sequences from additional species. Using a comparative phylogenetic approach, we leveraged maximum-likelihood tests of selection, as well as ancestral sequence reconstruction, to examine whether the species exhibited resistant nAChR, what mechanisms were present, and whether resistance mutations arose ancestrally or convergently across clades.

2. Methods

(a) . Tissues and DNA extraction

Thirty-nine tissue samples across 33 different species from Eupleridae, Herpestidae and Viverridae were obtained through specimen loans (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Genomic DNA was extracted as previously described [3] with a skin wash step for recalcitrant samples [24]. Previously designed primers were used to amplify 850 bp of the alpha subunit of the muscular nAChR gene (chrna1) that included the ligand-binding (and αNTX) epitope corresponding to residues 122–205 of the protein sequence [3] (see electronic supplementary material, Methods). Amplified PCR products were treated with ExoSAP-IT and Sanger sequenced by the University of Minnesota Genomics Center on an ABI 3730XL DNA Analyzer using BigDye Terminator v3.1 chemistry (Applied Biosystems, USA). Resulting DNA sequences were assembled, edited and aligned using Geneious v8.1 [3,25].

(b) . Bioinformatic retrieval of sequence

All mammalian sequences included in the NCBI orthologue database (accessed 24 May 2022) for the gene containing the muscular nAChR sequence, chrna1, were included in this dataset. Additional blastP searches were conducted using Viverrid, Herpestid and Euplerid sequences generated from this project. Results were filtered for duplicate species and a final dataset of 199 sequences was aligned using MUSCLE [25] and edited in Geneious v8.1. A 90 bp fragment (175–198aa) covering the acetylcholine/αNTX-binding epitope was used for analyses, as this was the longest fragment with complete data for most species (electronic supplementary material, table S3). Timetree was used to generate a phylogenetic tree, and missing species were subsequently added in Mesquite using existing topologies [26–29].

(c) . Tests of selection

We used a suite of likelihood-based codon models which use the ratio of non-silent substitutions to silent substitutions (dN/dS) to detect positive selection [21,30–35]. Because we were interested in selection specifically on branches of the tree leading to Viverridae, and Herpestidae + Eupleridae (figure 1), we used a branch-site test for positive selection identifying these lineages and all subtending branches as the foreground. Similarly, site tests were used to identify sites which exhibit signatures of selection [21,35]. Lastly, to discern signals of convergent versus pervasive selection, we employed a ‘drop-out’ site test in which we removed all species in Viverridae, Herpestidae and Eupleridae as well as honey badger (Mellivora capensis), pig (Sus scrofa) and hedgehog (Erinaceous europea) from the topology in Mesquite and re-run site tests [27,36]. Ancestrally reconstructed sequences were generated from the best-fit site model (M8) in PAML v4.6 (table 1) and aligned using MUSCLE v3.5 [21,26]. For complete details, see electronic supplementary material, methods.

Table 1.

Results of branch-site tests for positive selection on the CHRNA1 gene.

| model and log-likelihood | site classa | proportion of sites | w background | w foregroundb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| w2 = 1 | 0 | 0.746 | 0.0139 | 0.0139 |

| lnL = −1395.62 | 1 | 0.152 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 2a | 0.085 | 0.0139 | 1.0 | |

| 2b | 0.017 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| w2 > 1 | site class | proportion of sites | w background | w foregroundb |

| lnL = −1384.06 | 0 | 0.705 | 0.013 | 0.013 |

| 1 | 0.150 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 2a | 0.121 | 0.013 | 10.20 | |

| 2b | 0.026 | 1.0 | 10.20 |

aSite class 0 and 1 apply to foreground and background lineages and include sites under purifying selection (0 < w < 1) and neutral sites (w = 1), respectively. Site class 2 allows a proportion of positively selected sites (w > 1) in the foreground lineages, where 2a includes sites under purifying selection (0 < w < 1) in the background lineages and 2b includes neutral sites (w = 1) in the background lineages. 2Δln = 20, d.f. = 1, p < 0.0001. When Mellivora capensis, Sus scrofa and Erinaceous euopus are included in foreground branches 2Δln = 30, d.f. = 1, p < 0.0001.

bHerpestidae, Eupleridae and Viverridae were included in the foreground class.

3. Results and discussion

(a) . Evolutionary history of resistance in Herpestidae, Eupleridae and Viverridae

To assess αNTX resistance, we used aligned sequence data for the αNTX-binding epitope of nAChR (figure 1) and interpreted sequence data using extensive prior literature that has experimentally demonstrated the effects of specific amino acid substitutions on αNTX binding. We found that all newly sequenced nAChRs from species belonging to the family Herpestidae have N187, T189 and L194, H197 which confer strong glycosylation and proline resistance, respectively (figure 1) [10–20]. All Malagasy carnivores (Eupleridae) as well as two civets (Viverridae) have substitution R187 and I/L189 which confer electrostatic repulsion resistance (figure 1) [3,13,18,19]. Within civets (Viverridae), we found novel mutations (K187 and E189) which arose at the base of the genus Genetta (small African carnivores including the genet). Lysine (K) is one of only three positively charged amino acids and may mimic electrostatic repulsion resistance seen with R187; however, biophysical testing is needed to definitively assess the impact of K187 on αNTX binding and how this translates to whole-organism resistance.

To examine whether αNTX evolved convergently, we employed a codon model (CODEML) maximum-likelihood ancestral reconstruction of sequences implemented in PAML v4.6 [6,21,37]. Our ancestral reconstruction supports that electrostatic repulsion resistance via R187 arose once at the base of Eupleridae + Herpestidae and twice within Viverridae. Subsequent glycosylation resistance (N187, T189) as well as proline resistance (L194, H197) appears to have arisen later in Herpestidae (figure 1). Empirical work has shown that electrostatic repulsion resistance is less effective than either glycosylation or proline resistance [9,12,20]. Our data suggest that electrostatic repulsion resistance arose first at the base of Eupleridae + Herpestidae, and subsequent selection for increased resistance in Herpestids likely led to glycosylation and proline resistance. Interestingly, the Malagasy carnivores (Euplerids) are not sympatric with any αNTX producing snake besides sea snakes (for which we do not have any evidence of predation). As the Euplerids are restricted to Madagascar, and the R187 appears to have preceded the split between Euplerids and Herpestids (figure 1), the presence of this mutation in these species is most likely a remnant of selection pressure imposed prior to the isolation of this group on Madagascar, though further work should explore if these ancient substitutions have facilitated (or are maintained by) a contemporary ecological interaction such as exploitation of poisonous or venomous prey (e.g. frogs, scorpions and centipedes).

Across the clades Herpestidae, Eupleridae and Viverridae, mutations known to confer resistance have arisen at least four times (five, if we include K187 in civets). These results strongly suggest that species among all three clades have substantial αNTX-resistant nAChRs and warrant further investigation into their ecological interactions with venomous snakes, as well as their physiological ability to cope with venom.

(b) . Positive selection identified for substitutions

To test for adaptive evolution on nAChR in the clades we suspected of being venom resistant, we used codon model-based (CODEML) branch-site tests of positive selection in PAML v4.6 and explored additional methods and results in the electronic supplementary material [21]. Convergent foreground branches were specified as Eupleridae + Herpestidae, the base of Viverridae, and singular branches leading to honey badger, hedgehog and pig [3]. Because the latter three species and the mongoose have previously been shown to be under positive selection and may inflate the overall signal of selection, we performed branch-site tests with and without these species (figure 1). In both cases, we recovered a strong signal of selection in foreground lineages (2ΔL = 30, d.f. = 1, p < 0.0001; without honey badger, hedgehog and pig 2ΔL = 20, d.f. = 1, p < 0.0001; table 1). ‘Drop-out’ site tests showed no selection for a tree pruned of all lineages suspected of being under selection, (2ΔL = 2.4, d.f. = 1, p = 0.121), indicating that the signal of positive selection can be attributed to the foreground lineages [36].

Bayes empirical Bayes tests identified four sites to be evolving under positive selection in foreground lineages (table 2). Of these, three (187, 189 and 197) modulate αNTX binding in empirical studies [12–16,19,20]. Site 182 was identified as a site under positive selection, though no functional studies exist for this site (figure 1 denoted in grey).

Table 2.

Sites identified to be evolving under positive selection via different maximum-likelihood analyses. Italics indicate sites for which the probability that omega is greater than 1 is 95% or more.

| site | foreground specified PAML | foreground specified MEME | foreground unspecified PAML | foreground unspecified MEME | mutations | function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 182 | 0.96 | — | — | — | W, Q | unknown |

| 187a | 1.00 | — | 0.965 | — | Rb, Nc, K | Shb/Erc |

| 189a | 1.00 | 0.9911 | 0.776 | — | L, I, E, Tc | Shc |

| 195 | — | — | 0.990 | 0.955 | L | |

| 197a | 0.95 | — | — | — | H | Prd |

(c) . Mutations recovered in other mammals

Within our 199-mammal dataset, we found five new instances of independently evolved substitutions known to confer electrostatic repulsion resistance (R187) outside the three clades initially examined. In two of these instances, the Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) and the oryx antelope (Oryx dammah), R187 is not secondarily accompanied by the substitution I189 or L189 (figure 1). Empirical work has shown that nAChR loses affinity for αNTX with the R187 mutation alone, and that addition of the I189, or I189 by itself does not confer resistance despite its propensity to be paired with R187[19]. However, the presence of the single mutant R187 in these data suggests that the accompanying mutation I189 is likely not a necessary epistatic mutation and raises the possibility that it may have some function in resistance that is apparent in vivo that is not recovered in vitro [19]. Both the Eurasian otter and the oryx antelope are sympatric with αNTX producing snakes, though direct ecological links were not found in the literature for either species. While snake venom is by far the best-known source of nAChR agonists, we should resist the temptation to consider it the sole source of selection pressure for this receptor. Notably, the Eurasian otter is known to eat venomous catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus), and while catfish venom is not well studied, the acetylcholine receptor agonist atropine partially diminished the effects of bullhead venom in mice, suggesting the nAChR may be the targeted receptor for this venom [38–41]. Khan et al. [10] also found two species of freshwater fish that exhibit substitutions that confer αNTX resistance and suggest that this may be an adaptation to exposure to αNTXs secreted by freshwater cyanobacteria [15]. These hypotheses are both speculative and demand further examination on the source of nAChR-targeting toxins which may be driving selection for these substitutions.

Further investigations of species closely related to Oryx dammah revealed that all available species in the families Alcelaphinae and Hippotraginae also had an R187 mutation (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Notably, Kazandian et al. [42] suggest that venom spitting did not evolve as a response to trampling by ungulates, but instead was an adaptation that arose convergently as a response to predation by great apes [42]. These data may suggest an alternate source of selection pressure and a potentially coevolutionary relationship driving the evolution of spitting.

We found that the warthog, Phacochoerus africanus, shares the R187 and L189 mutation with its pig sister taxa (Sus scrofa), and that this mutation arose in an ancestor of these two species. Additional African species with charge-resistant mutations are the Cape golden mole (Chrysochloris asiatica, R187), a subterranean blind animal which may be especially susceptible to predation by burrowing snakes and is known prey of several species of Elapids, and the thicket rat (Grammomys surdaster; K187) [43–45].

The only non-African species with R187 was the Australian brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula). While this species is sympatric with αNTX producing elapids, mention of ecological interactions with venomous snakes in the literature is lacking. However, some species of elapids (Hoplocephalus stephensii) have been known to prey upon closely related pygmy opossums [46]. Mammalian resistance in Australian mammals is generally understudied and should be further explored. Additionally, several other species (wombats, bush babies and aardvarks) showed convergent mutations (K187, Q187 and C187) of unknown function, and further biochemical assessment is needed.

(d) . Conclusions

The evolution of resistance to αNTX in mammals has previously been categorized as a relatively rare adaptation only known in six mammals [3]. This work revealed 27 new species with amino acid changes known to cause resistance (experimentally validated across diverse taxa), and an additional 17 species with substitutions that are suspected to result in αNTX resistance [10–20]. In total, our work shows that convergent αNTX resistance has evolved at least 11 times within mammals. Further investigation of fauna that interact with αNTX producing snakes is needed to determine whether αNTX resistance translates to whole venom resistance, and whether these substitutions are the result of present or past ecological interactions with venomous species. Our analyses, along with other recent work, suggest that snake and other animal venoms are a source of strong selection pressure likely facilitated via complex coevolutionary interactions that may be the rule rather than the exception, particularly for animals which share habitat with many venomous snakes [5,19,47].

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Minnesota Supercomputer Institute and the University of Minnesota Genomic Center. Thanks to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), California Academy of Sciences (CAS), Denver Museum of Nature & Science (DMNS), Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH), University of Kansas (KU), Museum of Southwestern Biology (MSB), Berkeley's Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ) and Texas Tech University (TTU) for generously providing samples. A special thanks to Rafale Vianna Furer for their work on this project as an undergraduate at Macalester College. We are grateful for the valuable input by Yaniv Brandvain, Sharon Jansa, Emilie Richards, Kyle Keepers, Cathy Rushworth and Emma Roback. Finally, the authors would like to thank Georgia Hart, Natalie Coles, and Matt Holding whose conversations provided the fodder, curiosity and motivation for this work.

Data accessibility

All data (trees, alignments, control files, ancestral sequences, and gene trees) used in this manuscript can be found on the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.jh9w0vtf8 [48]; the accompanying READme.txt file provides a full description of all files included.

The data are provided in the electronic supplementary material [49].

Authors' contributions

D.H.D.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing; J.H.: data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, resources and writing—original draft; S.E.M.: funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision and writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was generously funded by the NIH TREM fellowship (grant no. K12GM119955), the UMN UROP and the Minnesota Herpetological Society.

References

- 1.Agrawal AA. 2017. Toward a predictive framework for convergent evolution: integrating natural history, genetic mechanisms, and consequences for the diversity of life. Am. Nat. 190, S1-S12. ( 10.1086/692111) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stern DL. 2013. The genetic causes of convergent evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 751-764. ( 10.1038/nrg3483) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drabeck DH, Dean AM, Jansa SA. 2015. Why the honey badger don't care: convergent evolution of venom-targeted nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mammals that survive venomous snake bites. Toxicon 99, 68-72. ( 10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.03.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drabeck DH. 2021. Resistance of native species to reptile venoms. In Handbook of venoms and toxins of reptiles, pp. 161-174. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drabeck DH, Rucavado A, Hingst-Zaher E, Dean A, Jansa SA. 2022. Ancestrally reconstructed von Willebrand factor reveals evidence for trench warfare coevolution between opossums and pit vipers. Mol. Biol. Evol. 39, msac140. ( 10.1093/molbev/msac140) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jansa SA, Voss RS. 2011. Adaptive evolution of the venom-targeted vWF protein in opossums that eat pitvipers. PLoS ONE 6, e20997. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0020997) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holding ML, Biardi JE, Gibbs HL. 2016. Coevolution of venom function and venom resistance in a rattlesnake predator and its squirrel prey. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20152841. ( 10.1098/rspb.2015.2841) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pomento AM, Perry BW, Denton RD, Gibbs HL, Holding ML. 2016. No safety in the trees: local and species-level adaptation of an arboreal squirrel to the venom of sympatric rattlesnakes. Toxicon 118, 149-155. ( 10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.05.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Thiel J, et al. 2022. Convergent evolution of toxin resistance in animals. Biol. Rev. 97, 1823-1843. ( 10.1111/brv.12865) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan MA, et al. 2020. Widespread evolution of molecular resistance to snake venom α-neurotoxins in vertebrates. Toxins 12, 638. ( 10.3390/toxins12100638) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones L, Harris RJ, Fry BG. 2021. Not goanna get me: mutations in the savannah monitor lizard (Varanus exanthematicus) nicotinic acetylcholine receptor confer reduced susceptibility to sympatric cobra venoms. Neurotox. Res. 39, 1116-1122. ( 10.1007/s12640-021-00351-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kachalsky SG, Jensen BS, Barchan D, Fuchs S. 1995. Two subsites in the binding domain of the acetylcholine receptor: an aromatic subsite and a proline subsite. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 10 801-10 805. ( 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10801) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barchan D, Ovadia M, Kochva E, Fuchs S. 1995. The binding site of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in animal species resistant to α-bungarotoxin. Biochemistry 34, 9172-9176. ( 10.1021/bi00028a029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asher O, Lupu-Meiri M, Jensen BS, Paperna T, Fuchs S, Oron Y. 1998. Functional characterization of mongoose nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α-subunit: resistance to α-bungarotoxin and high sensitivity to acetylcholine. FEBS Lett. 431, 411-414. ( 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00805-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barchan D, Kachalsky S, Neumann D, Vogel Z, Ovadia M, Kochva E, Fuchs S. 1992. How the mongoose can fight the snake: the binding site of the mongoose acetylcholine receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 7717-7721. ( 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7717) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takacs Z, Wilhelmsen KC, Sorota S. 2001. Snake α-neurotoxin binding site on the Egyptian cobra (Naja haje) nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is conserved. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18, 1800-1809. ( 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003967) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takacs Z, Wilhelmsen KC, Sorota S. 2004. Cobra (Naja spp.) nicotinic acetylcholine receptor exhibits resistance to erabu sea snake (Laticauda semifasciata) short-chain α-neurotoxin. J. Mol. Evol. 58, 516-526. ( 10.1007/s00239-003-2573-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dellisanti CD, Yao Y, Stroud JC, Wang ZZ, Chen L. 2007. Crystal structure of the extracellular domain of nAChR α1 bound to α-bungarotoxin at 1.94 Å resolution. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 953-962. ( 10.1038/nn1942) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris RJ, Fry BG. 2021. Electrostatic resistance to alpha-neurotoxins conferred by charge reversal mutations in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Proc. R. Soc. B 288, 20202703. ( 10.1098/rspb.2020.2703) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahman MM, Teng J, Worrell BT, Noviello CM, Lee M, Karlin A, Stowell MH, Hibbs RE. 2020. Structure of the native muscle-type nicotinic receptor and inhibition by snake venom toxins. Neuron 106, 952-962. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.03.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Z. 2007. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586-1591. ( 10.1093/molbev/msm088) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbour MA, Clark RW. 2012. Ground squirrel tail-flag displays alter both predatory strike and ambush site selection behaviours of rattlesnakes. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 3827-3833. ( 10.1098/rspb.2012.1112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voss RS, Jansa SA. 2012. Snake-venom resistance as a mammalian trophic adaptation: lessons from didelphid marsupials. Biol. Rev. 87, 822-837. ( 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2012.00222.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giarla TC, Voss RS, Jansa SA. 2010. Species limits and phylogenetic relationships in the didelphid marsupial genus Thylamys based on mitochondrial DNA sequences and morphology. Bullet. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2010, 1-67. ( 10.1206/716.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792-1797. ( 10.1093/nar/gkh340) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar S, Stecher G, Suleski M, Hedges SB. 2017. TimeTree: a resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1812-1819. ( 10.1093/molbev/msx116) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maddison WP, Maddison DR. 2021. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 3.70. See http://www.mesquiteproject.org.

- 28.Meredith RW, et al. 2011. Impacts of the Cretaceous terrestrial revolution and KPg extinction on mammal diversification. Science 334, 521-524. ( 10.1126/science.1211028) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agnarsson I, Kuntner M, May-Collado LJ. 2010. Dogs, cats, and kin: a molecular species-level phylogeny of Carnivora. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 54, 726-745. ( 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.10.033) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kosakovsky Pond SL, Frost SD. 2005. Not so different after all: a comparison of methods for detecting amino acid sites under selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 1208-1222. ( 10.1093/molbev/msi105) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kosakovsky Pond SL, et al. 2020. HyPhy 2.5—a customizable platform for evolutionary hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 295-299. ( 10.1093/molbev/msz197) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith MD, Wertheim JO, Weaver S, Murrell B, Scheffler K, Kosakovsky Pond SL. 2015. Less is more: an adaptive branch-site random effects model for efficient detection of episodic diversifying selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 1342-1353. ( 10.1093/molbev/msv022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kosakovsky Pond SL, Murrell B, Fourment M, Frost SD, Delport W, Cheffler K. 2011. A random effects branch-site model for detecting episodic diversifying selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 3033-3043. ( 10.1093/molbev/msr125) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murrell B, et al. 2015. Gene-wide identification of episodic selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 1365-1371. ( 10.1093/molbev/msv035) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murrell B, Wertheim JO, Moola S, Weighill T, Scheffler K, Kosakovsky Pond SL. 2012. Detecting individual sites subject to episodic diversifying selection. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002764. ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002764) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kowalxzyk A, Chikina M, Clark NL. 2021. A cautionary tale on proper use of branch-site models to detect convergent positive selection. bioRxiv. ( 10.1101/2021.10.26.465984) [DOI]

- 37.Yang Z. 2006. Computational molecular evolution. Oxford, UK: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruiz-Olmo J, Marsol R. 2002. New information on the predation of fish eating birds by the Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra). IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull 19, 103-106. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Narváez M, Cabezas S, Blanco-Garrido F, Baos R, Clavero M, Delibes M. 2020. Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) diet as an early indicator of recovery in defaunated river communities. Ecol. Indic. 117, 106547. ( 10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106547) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lanszki J, Sallai Z. 2006. Comparison of the feeding habits of Eurasian otters on a fast flowing river and its backwater habitats. Mamm. Biol. 71, 336-346. ( 10.1016/j.mambio.2006.04.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barthó L, Sándor Z, Bencsik T. 2018. Effects of the venom of the brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus) on isolated smooth muscles. Acta Biol. Hung. 69, 135-143. ( 10.1556/018.69.2018.2.3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kazandjian TD, et al. 2021. Convergent evolution of pain-inducing defensive venom components in spitting cobras. Science 371, 386-390. ( 10.1126/science.abb9303) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fielden LJ. 1989. Selected aspects of the adaptive biology and ecology of the Namib Desert golden mole (Eremitalpa granti namibensis). PhD thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bates MF, Wilson B. 2021. First record of a Cape cobra Naja nivea (Reptilia: Squamata) preying on an aardwolf Proteles cristatus (Mammalia: Carnivora). Afr. J. Ecol. 59, 266-268. ( 10.1111/aje.12792) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Broadley DG, Baldwin AS. 2006. Taxonomy, natural history, and zoogeography of the southern African shield cobras, genus Aspidelaps (Serpentes: Elapidae). Herpetol. Nat. Hist. 9, 163-176. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fitzgerald M, Shine R, Lemckert F. 2004. Life history attributes of the threatened Australian snake (Stephen's banded snake Hoplocephalus stephensii, Elapidae). Biol. Conserv. 119, 121-128. ( 10.1016/j.biocon.2003.10.026) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schield DR, et al. 2022. The roles of balancing selection and recombination in the evolution of rattlesnake venom. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 1367-1380. ( 10.1038/s41559-022-01829-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drabeck DH, Holt J, McGaugh SE. 2022. Data from: Widespread convergent evolution of alpha-neurotoxin resistance in African mammals. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.jh9w0vtf8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Drabeck DH, Holt J, McGaugh SE. 2022. Widespread convergent evolution of alpha-neurotoxin resistance in African mammals. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6296349) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Drabeck DH, Holt J, McGaugh SE. 2022. Data from: Widespread convergent evolution of alpha-neurotoxin resistance in African mammals. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.jh9w0vtf8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Drabeck DH, Holt J, McGaugh SE. 2022. Widespread convergent evolution of alpha-neurotoxin resistance in African mammals. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6296349) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

All data (trees, alignments, control files, ancestral sequences, and gene trees) used in this manuscript can be found on the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.jh9w0vtf8 [48]; the accompanying READme.txt file provides a full description of all files included.

The data are provided in the electronic supplementary material [49].