Abstract

In this study, red mud (RM) was used as a support for LaFeO3 to prepare LaFeO3-RM via the ultrasonic-assisted sol–gel method for the removal of methylene blue (MB) assisted with bisulfite (BS) in the aqueous solution. Characterization by scanning electron microscopy and the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller method indicated that LaFeO3-RM exhibited a large surface area and porous structure with a higher pore volume (i.e. 10 times) compared with the bulk LaFeO3. The XRD, XPS and FTIR results revealed that the support of porous RM not only dispersed LaFeO3 particles but also increased Fe oxidation capability, oxygen-containing functional groups and chemically adsorbed oxygen (from 44.3% to 90.3%) of LaFeO3-RM, which improved the catalytic performance in structure and chemical composition. MB was removed through the synergistic effect of adsorption and catalysis, with MB molecules first absorbed on the surface and then degraded. The removal efficiency was 88.19% in the LaFeO3-RM/BS system under neutral conditions but only 27.09% in the LaFeO3/BS system. The pseudo-first-order kinetic constant of LaFeO3-RM was six times higher than that of LaFeO3. Fe(III) in LaFeO3-RM played a key role in the activation of BS to produce by the redox cycle of Fe(III)/Fe(II). Dissolved oxygen was an essential factor for the generation of . This work provides both a new approach for using porous industrial waste to improve the catalytic performance of LaFeO3 and guidance for resource utilization of RM in wastewater treatment.

Keywords: red mud, perovskite, sulfate radical, fenton-like, dyes, waste utilization

1. Introduction

Dye wastewater from various industries has posed a serious threat to the ecological environment and human health due to its high toxicity and non-biodegradability [1]. Methylene blue (MB), as an artificial organic cationic dye, is widely used as a colouring agent and redox indicator [2,3]. However, the aromatic rings in it could cause carcinogenic and mutagenic effects [4]. Therefore, developing effective treatment of dye wastewater is of vital importance.

The current treatment methods for dye wastewater include adsorption [5,6], catalytic ozonation [7], membrane separation [8] and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) [9–11]. Among them, AOPs based on sulfate radical () are widely used to remove organic pollutants in wastewater [12]. Compared with OH·, has a higher redox potential (E0 = 2.5–3.1 V) [13] and can degrade pollutants in a wider pH range (4 < pH < 9) [14]. Normally, is produced through activation of persulfate (PS) by UV [15], heat [16], ultrasound [17] and transition metals [18–20]. However, the application of PS was limited due to its slow reaction rate, secondary pollution and low stability in water [13]. Therefore, bisulfite (BS) is attracting increasing attention for its low cost and environment-friendly characteristics. Recently, studies have found that BS can also be activated by UV [21] and transition metals [22,23] to produce . However, the application of the BS activation system is limited due to its low efficiency. Therefore, searching for an effective BS activation system has attracted increasing interest.

Recently, different heterogeneous iron-based catalysts have been widely studied in AOPs for their high catalytic activity and natural abundances [24–26]. LaFeO3, as an iron-based compound, has shown catalytic performance in the activation of PS. [27]. As an ABO3 perovskite oxide with Fe element in B sites, LaFeO3 could be used for activating PS through the redox cycle of Fe(III)/Fe(II) [28]. LaFeO3 shows higher catalytic activity than Fe2O3 in degrading diclofenac by activating PMS [29]. Therefore, LaFeO3 shows great potential for BS activation.

However, due to the high temperature required in the synthesis of LaFeO3, bulk LaFeO3 was non-porous and its specific surface area was usually below 10 m2 g−1, resulting in low catalytic activity [30]. Therefore, in order to improve the catalytic activity of LaFeO3, LaFeO3 was supported on porous supports to obtain supported perovskite catalysts with increased surface areas and porous structures. SiO2 [31,32] and Al2O3 [33] were found to be effective supports for LaFeO3. It is interesting to load LaFeO3 on porous supports due to their adsorption capacity, which allows the pollutants to be adsorbed on the surface and then degraded [32]. Therefore, the supported LaFeO3 catalysts could realize the synergistic effect of adsorption and catalysis. However, those supports used in previous studies are costly. Consequently, it is of vital importance to find cheap and easily available supports. A previous study suggested porous materials with randomly distributed pores and short pore lengths were more suitable as supports for LaFeO3 [31].

Red mud (RM) was considered a suitable support for LaFeO3 due to its large surface area, abundant randomly distributed pores and high stability in water [34]. As a typical solid waste produced in alumina production using the Bayer process, the production of RM reached 77 million tons globally in 2017 [35,36]. As a cost-free, environmentally friendly and functional material with application prospects, RM contains many residual bauxite minerals, including hematite, magnetite and titanium dioxide, which could be used as catalysts or adsorbents in dye water treatment [37]. The rich Fe2O3 (15.2%–62.8%) contained in RM makes it an ideal catalyst for the activation of BS [38,39]. Effective utilization of RM can reduce the landfill of RM, which can cause damage to the environment [40]. Therefore, loading LaFeO3 on RM could be an effective and environmentally friendly way to improve the catalytic performance of bulk LaFeO3. Simultaneously, the reduction and waste utilization of RM were also achieved in this way. In addition, this type of supported perovskite catalysts for BS activation has not been reported.

In this study, LaFeO3-RM was successfully synthesized using the ultrasonic-assisted sol–gel method. To understand the mechanism of the LaFeO3-RM/BS system on MB removal, the objectives of this study were: (i) to observe the surface morphology, pore structure and chemical compositions of LaFeO3-RM; (ii) to evaluate the catalytic activity of the LaFeO3-RM/BS system, including the feasibility, mineralization, reusability and stability; and (iii) to identify the main active species and explore the possible mechanism of MB removal in the LaFeO3-RM/BS system.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Chemicals

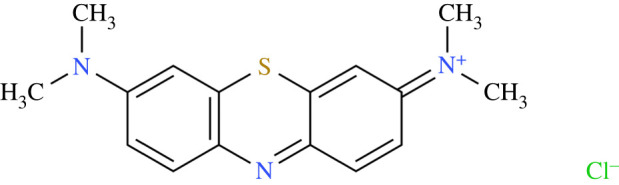

A sample of raw RM was obtained from a local RM landfill site in Shandong Province of China. Tert-butyl alcohol (TBA) and methanol (Me) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). MB (C16H18ClN3S, 98.5%; the structure is shown in figure 1), anhydrous citric acid (C6H8O7), ferric nitrate non-ahydrate (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O), lanthanum nitrate hexahydrate (La(NO3)3·6H2O), sodium bisulfite (NaHSO3), sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3), sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and hydrochloric acid (HCl) were purchased from Chengdu Cologne Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Sichuan, China). The reagents were all analytically pure (AR) and were used directly without further purification. Deionized water was used throughout the experiments.

Figure 1.

The structure of MB.

2.2. Preparation of LaFeO3-RM

LaFeO3-RM was synthesized via the sol–gel method. First, the raw RM was dried at 65°C, then it was ground and bagged with a 100-mesh sieve for further use. Then, Fe(NO3)3·9H2O (4.04 g) and La(NO3)3·6H2O (4.33 g) were dissolved into 40 ml deionized water under magnetic stirring. Citric acid (5.76 g) was added after the above solutions were fully mixed together. After that, 4 g of RM powder was added and stirred evenly. Then, the mixed solution was ultrasonically treated for 10 min every 10 min in a water bath of 70°C. After four cycles of ultrasonic treatment, the mixed solution was heated in a water bath of 70°C and mechanically stirred until the sol was formed. Subsequently, the sol was dried overnight at 105°C to obtain the dried red-brown gel. Finally, the dried gel was transferred to a crucible and heated in a muffle furnace at 600°C with a heating rate of 10°C min−1 to obtain the LaFeO3-RM. For comparison, LaFeO3 was also prepared via the same method described above. Also, a sample following the same synthetic method without LaFeO3 was denoted as RM-600.

2.3. Characterization

The morphology and surface elements of the samples (raw RM, LaFeO3 and LaFeO3-RM) were analysed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS) equipped with ZEISS Gemini 300. The specific surface area and N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of the samples were determined by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method using Micromeritics ASAP2460. The crystalline phases of the samples were determined by X-ray powder diffractometer (XRD, X’ Pert PRO) using Cu Kα radiation. The elemental composition and chemical valence state of the samples were determined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Scientific K-Alpha). The functional groups contained in the samples in the range of 4000–400 cm−1 were recorded using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FT-IR, Nicolet 670, USA).

2.4. Performance evaluation of LaFeO3-RM

MB was selected as a model pollutant, and decolorization of MB was tested to evaluate the removal activity of LaFeO3-RM. All experiments were carried out in 250 ml beakers at 25 ± 2°C under mechanical stirring with a double-blade impeller (300 r min−1) to ensure full blending and sufficient contact with air. The beakers were covered with aluminium foil to avoid light. First, 100 ml MB solution with an initial concentration of 60 mg l−1 was prepared, and 10 mmol l−1 of BS was added to the solution. Then, its pH was quickly adjusted to 7 with 0.1 M HCl and NaOH. After that, 0.5 g l−1 LaFeO3-RM was added to the solution to start the reaction (T = 0 min). At different time intervals (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45 and 60 min), 1.0 ml samples were quickly withdrawn with syringes and filtered through Millipore filters with a pore diameter of 0.45 µm. After that, the samples were transferred into 5 ml centrifuge tubes and 0.1 mol l−1 Na2S2O3 was quickly added to quench the reaction.

The effects of different operation parameters on the removal efficiency were also explored, including initial pH (3–11), BS concentration (1–20 mmol l−1) and initial MB concentration (10–80 mg l−1). Similarly, to further evaluate the active species in the reaction, TBA and methanol (MeOH) with different molar ratios were added to the reaction solution in the quenching experiment. The dissolved oxygen of the system was measured with a dissolved oxygen meter. The chemical oxygen demand (COD) of the MB solution after the reaction was measured using a COD analyser (RB-101H, Guangzhou Ruibin technology, China). Also, the total organic carbon (TOC) was measured using a TOC analyser (LB-CD-800S, LOOBO, China).

Cycle tests were also carried out to investigate the reusability of LaFeO3-RM. After each reaction, LaFeO3-RM was filtered, recovered and washed with ethanol and water. Then, it was dried in an oven at 65°C for the next cycle. The residual solution was filtered and collected, and the leaching of metal ions was determined by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, Aglient7800).

2.5. Analytic methods

The absorbance of samples was measured by UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV1780) at the maximum absorption wavelength of 664 nm, and the residual concentration in the MB solution was determined by a standard concentration versus absorbance curve. The removal efficiency of LaFeO3-RM was calculated according to equation (2.1):

| 2.1 |

In addition, the removal process was fitted by the pseudo-first-order kinetic equation (2.2):

| 2.2 |

where Ct represents the concentration of MB at time t (mg l−1), C0 represents the initial concentration of MB (mg l−1) and k1 represents the kinetic constant (min−1).

All experiments were repeated three times, and the data obtained were averaged for use in figures and tables. The corresponding experimental errors are shown by error bars, which were within ±5% [41].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of LaFeO3-RM

3.1.1. Surface morphology and pore structure characteristics

The surface morphologies of LaFeO3, LaFeO3-RM and raw RM are shown in figure 2. It can be seen that bulk LaFeO3 was mainly in a blocky-flake structure, with a relatively smooth surface and non-porous structure as mentioned in the introduction (figure 2a,b). However, with RM added for support, the morphology of LaFeO3-RM was significantly changed, exhibiting an obvious porous structure and high specific surface area (figure 2c,d). Some pores with sizes of 100–500 nm can be clearly observed on the surface of LaFeO3-RM. The surface morphology of raw RM showed a large number of spherical particles, which aggregate together (figure 2e). The element mapping of LaFeO3-RM proved the uniform dispersion of LaFeO3 on RM, where high contents of La, Fe and O were indicated in the selected area (figure 2f–i). The EDS spectrum and chemical composition of RM and LaFeO3-RM are summarized in figure 2j–k. It shows that the element contents of La and Fe increased significantly in LaFeO3-RM. As shown in figure 2k, LaFeO3-RM was mainly composed of elements of O, Fe, La, Al, Na and Si. The results further confirmed the successful support of LaFeO3 on RM.

Figure 2.

SEM images of LaFeO3 (a,b), LaFeO3-RM (c,d) and raw RM (e); element mapping of LaFeO3-RM (f–i); and EDS spectra of the RM (j) and LaFeO3-RM (k).

To further investigate the effect of RM support and LaFeO3 loading on the structure of LaFeO3-RM, N2 adsorption–desorption analysis was conducted. As shown in figure 3a, the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm of LaFeO3-RM was convex downward in the whole pressure range with no inflection point in the curve. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemists classification, the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm of LaFeO3-RM belonged to type IV, indicating the porous structure of LaFeO3-RM with both mesoporous and microporous characteristics. The nitrogen absorption curve continued increasing with relative pressure (P/P0) around 1, suggesting the existence of macroporosity in LaFeO3-RM [39]. Also, an H3 hysteresis loop was observed in the isotherm of LaFeO3-RM, indicating the presence of narrow-slit pores [42]. However, the isotherm of LaFeO3 was of type III, suggesting the non-porous structure of LaFeO3. Compared with LaFeO3-RM, the adsorption capacity of LaFeO3 was significantly lower. Furthermore, the isotherm of LaFeO3 crossed with P/P0 around 0.4, indicating a small surface area of LaFeO3. Figure 3b shows that RM exhibited a similar type IV isotherm as LaFeO3-RM, indicating that LaFeO3 has limited influence on the basic pore structure of RM.

Figure 3.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and pore size distribution of LaFeO3 and LaFeO3-RM (a) and RM (b).

The textural properties of LaFeO3, LaFeO3-RM and RM are shown in table 1. The specific surface area of LaFeO3 was only 9.8216 m2 g−1, suggesting a small surface area as mentioned in the introduction. However, the specific surface area of LaFeO3-RM was twice that of LaFeO3, exhibiting a relatively higher specific surface area. The reduction of the specific surface area of RM-supported materials could be due to the blockage of some small pores in the treatment process, which has been reported in previous literature [43]. Also, LaFeO3-RM exhibited a high pore volume of 0.114234 cm3 g−1, which was 10 times higher than the bulk LaFeO3, as shown in the pore size distribution curve in figure 3a, which indicates that the mesoporosity increased with the addition of LaFeO3. Furthermore, the LaFeO3-RM showed higher average pore diameters than the RM and bulk LaFeO3. The high adsorption capacity of LaFeO3-RM could provide a certain space for MB adsorption.

Table 1.

Textural properties of LaFeO3, LaFeO3-RM and RM.

| sample | SBET (m2/g) | V(cm3/g) | DBET (nm) | DBJH (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LaFeO3 | 9.8216 | 0.012537 | 2.9607 | 17.4172 |

| LaFeO3-RM | 20.6025 | 0.114253 | 15.5045 | 24.2370 |

| RM | 31.1584 | 0.132480 | 8.7172 | 18.6256 |

3.1.2. Chemical composition characteristics

The XRD patterns of RM, RM-600, LaFeO3-RM and LaFeO3 are shown in figure 4a. The composition of RM was relatively complex with phases determined as gibbsite (α-Al(OH)3), hematite (α-Fe2O3), anatase (TiO2), cristobalite (SiO2), lepidocrocite (FeO(OH)), nepheline (NaAlSiO4) and diaspore (β-AlOOH). As shown in RM-600, the increase of hematite and nepheline with the decomposition of related compounds indicates that the high temperature during the synthesis converted the hydroxide phase into the oxide phase. Also, the diffraction peak corresponding to the Al compound disappeared, indicating the Al compound was decomposed to an amorphous form [44]. After loading LaFeO3, the peak intensity of RM was reduced for the blockage of some small pores, as mentioned in the N2 adsorption–desorption analysis. As expected, LaFeO3-RM showed the main characteristic diffraction peaks of LaFeO3 at 2θ = 22.6°, 32.3°, 39.8°, 46.4°, 57.4°, 67.4° and 76.8°, which were basically consistent with the diffraction peaks of LaFeO3 standard card (PDF# 37-1493). Furthermore, the peak intensity of LaFeO3-RM was reduced compared with bulk LaFeO3, suggesting highly dispersed LaFeO3 on RM as observed in the element mapping of LaFeO3-RM.

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of RM, RM-600, LaFeO3 and LaFeO3-RM (a); XPS survey spectrum of LaFeO3-RM (b); high-resolution XPS spectrum of LaFeO3 and LaFeO3-RM for La 3d (c), Fe 2p (d) and O 1 s (e); FTIR spectra of RM, LaFeO3 and LaFeO3-RM from 400 to 4000 cm−1 (f).

The elemental composition and chemical valence of LaFeO3-RM were determined by XPS analysis, and the results are shown in figure 4b–e. Elements such as La, Fe, O, Al, Na, Si, Ti and C were detected on the surface of LaFeO3-RM, in which La was derived from LaFeO3; Al, Na, Si, Ti were derived from RM; Fe and O were attributed to both RM and LaFeO3; and C could be attributed to the amorphous carbon form by the pyrolysis of the citric acid (figure 4b). Figure 4c shows the high-resolution XPS spectrum of La 3d for LaFeO3 and LaFeO3-RM. For LaFeO3-RM, the peaks at 835.18 eV and 838.88 eV, and 852.08 eV and 855.78 eV corresponded to La 3d3/2 and La 3d5/2, respectively. The binding energy (BE) difference between La 3d3/2 and La 3d5/2 was 16.9 eV, indicating the presence of La(III) in LaFeO3-RM [45,46]. Compared with LaFeO3, the peaks of La 3d3/2 and La 3d5/2 in LaFeO3-RM both shifted to higher BE (+0.4 eV). In the Fe 2p spectrum, for LaFeO3-RM, the peaks at 724.8 eV and 724.02 eV corresponded to Fe 2p1/2, while the peaks at 711.2 eV corresponded to Fe 2p3/2 (figure 4d). The BE difference between Fe 2p3/2 and Fe 2p1/2 was 13.6 eV. Therefore, the two peaks were attributed to Fe(III) [46]. As expected, the peaks of Fe 2p3/2 and Fe 2p1/2 in LaFeO3-RM were also observed shift to higher BE (+0.4 eV) compared with LaFeO3, indicating the increase of Fe oxidation capability with RM as a support for LaFeO3 [47]. Figure 4e shows the spectrum of O 1 s for LaFeO3 and LaFeO3-RM. For LaFeO3, it was observed that the peaks at 529.4 eV, 531.3 eV and 533.0 eV were attributed to lattice oxygen (), chemically adsorbed oxygen (OH−) and adsorbed water (H2O), respectively [48]. For LaFeO3-RM, the peaks at 531.0 eV and 532.8 eV were attributed to lattice oxygen and chemically adsorbed oxygen, respectively. As expected, the peaks of O 1 s for LaFeO3-RM both shifted to lower BE, further indicating the high oxidation capability of Fe in LaFeO3-RM, which could be related to the high oxidation capacity of rich Fe2O3 in RM [49]. Furthermore, only the peaks of chemically adsorbed oxygen and adsorbed water were observed in LaFeO3-RM, while the peak of lattice oxygen disappeared. It was noted that the content of chemically adsorbed oxygen increased significantly from 44.3% to 90.3% with the support of RM. Chemically adsorbed oxygen played an important role in the catalytic performance of the catalyst [32]. Therefore, LaFeO3-RM was considered to be an ideal catalyst for its abundant chemically adsorbed oxygen.

The FTIR spectrums of RM, LaFeO3 and LaFeO3-RM in the range of 400–4000 cm−1 are shown in figure 4f. The four peaks at 3520 cm−1 and 1450 cm−1 for RM, 1390 cm−1 for LaFeO3, and 3520 cm−1 and 1401 cm−1 for LaFeO3-RM belonged to the hydroxyl (OH) groups. The peaks at 997 cm−1 for RM and 972 cm−1 for LaFeO3-RM corresponded to the Si-O groups. The peaks around 3425 cm−1 for LaFeO3 and 3446 cm−1 for LaFeO3-RM were attributed to stretching vibrations of La–O. For RM, the peaks at 460 cm−1 and 552 cm−1 were attributed to the stretching vibrations of Fe-O of Fe2O3. For LaFeO3-RM, the significantly higher intensity peak at 597 cm−1 was observed for the stretching vibrations of La-O corresponding to LaFeO3 and Fe-O corresponding to both LaFeO3 and Fe2O3 [50]. The result of FTIR analysis further confirmed the successful synthesis of LaFeO3-RM, as indicated in the above SEM analysis. It can be seen that, compared with bulk LaFeO3, there were abundant oxygen-containing functional groups of -OH and Si-O on LaFeO3-RM, which could promote the adsorption of positively charged substances, such as MB molecules, in the aqueous solution process [51].

3.2. Methylene blue removal under different systems

In order to identify the catalytic activity of LaFeO3-RM, the removal of MB under different systems was investigated. As shown in figure 5a, with the absence of BS, the untreated RM and LaFeO3 exhibited a weak adsorption effect on MB (less than 8.5%), while LaFeO3-RM had an obvious adsorption effect on MB with an adsorption removal efficiency of 12.10%, probably due to the high specific surface area, increased mesoporosity and abundant surface functional groups of LaFeO3-RM. Subsequently, the removal efficiency of MB with the presence of BS was calculated, and the results are shown in figure 5b. With the presence of BS alone, the removal efficiency was only 6.55% within 60 min, indicating that BS itself had limited degradation ability for MB, since BS could be oxidized by dissolved oxygen to form sulfate radicals, which could slightly degrade organic pollutants [52]. RM, LaFeO3 and LaFeO3-RM all showed catalytic effects on MB degradation, with removal efficiencies of 27.09%, 41.32% and 88.19%, respectively. For the RM/BS system, the rich Fe2O3 in RM provided Fe(III) to activate BS to generate for effective degradation of MB, which was proved in previous literature [49]. Figure 5c shows that the removal processes followed the pseudo-first-order reaction kinetic model, and the kinetic constant of LaFeO3-RM was six times higher than that of LaFeO3. Compared with bulk LaFeO3, the LaFeO3-RM/BS system showed significantly enhanced removal of MB. These results clearly indicate that BS was activated by LaFeO3-RM to produce some strong oxidation radicals such as and ·OH, which significantly increased the removal of MB [28].

Figure 5.

The removal efficiency of MB under different systems: the absence of BS (a) and presence of BS (b); curves of pseudo-first-order kinetic model on the MB removal by LaFeO3-RM, LaFeO3, RM and BS (c). Experimental conditions: initial pH = 7.0, [Catalyst] = 0.5 g l−1, [MB] = 60 mg l−1, [BS] = 10 mM l−1.

3.3. Effect of operating parameters on methylene blue removal

To further explore the performance of the LaFeO3-RM/BS system, the effects of initial pH, BS concentration and initial MB concentration on MB removal were also investigated, and the results are shown in figure 6.

Figure 6.

Effects of initial pH (a), BS concentration (c), initial MB concentration (d) and inorganic ions and HA (f) on MB removal; changes of solution pH during the reaction (b); curves of pseudo-first-order kinetic model on MB removal under different initial MB concentrations (e).

The initial pH had a certain effect on the removal efficiency of the AOPs system based on sulfate radical (). As shown in figure 6a, the removal efficiency of MB decreased sharply under strongly acidic conditions (pH = 3). is amphoteric and follows two balance equations:

| 3.1 |

k1 = 1.02 × 10−7

| 3.2 |

k2 = 0.65 × 10−12

The equilibrium constant of the above equations, k1 > k2, indicates that mainly exists as . Therefore, the decrease in removal efficiency under strongly acidic conditions might be caused by the inhibition of BS decomposition, resulting in the reduction of (equation (3.8)). The decrease in removal efficiency under alkaline conditions might be attributed to the formation of ·OH by the reaction of and water (equation (3.9)). In addition, the standard redox potential of was about 3.0 V, while that of ·OH was about 2.8 V. When the initial pH was greater than 9, almost all was converted into ·OH (equation (3.4)), leading to a lower degradation efficiency [23]. The equations are as follows:

| 3.3 |

and

| 3.4 |

Furthermore, the point of zero charges of LaFeO3-RM was determined to be 9.1, which could prevent the electrostatic attraction in the system under alkaline conditions [27]. As shown in figure 6b, pH decreased significantly in the LaFeO3-RM/BS system, indicating the generation of H+ in the reaction process. The above results indicate that the LaFeO3-RM/BS system could effectively remove MB under neutral and alkaline conditions.

As shown in figure 6c, the removal efficiency of MB increased when BS concentration increased from 1 to 10 mM l−1. However, with the BS concentration increased from 10 to 20 mM l−1, the removal efficiency of MB decreased gradually. When the BS concentration was 20 mM l−1, the removal efficiency of MB was only 78.81% within 60 min. It is probable that the reaction between BS and (equation (3.5)) and the self-quenching reaction of (equation (3.6)) led to the decrease of in the system, thus reducing the removal efficiency of MB [53]. Therefore, increasing the BS concentration within a certain range could promote the removal performance of the LaFeO3-RM/BS system, and excessive BS concentration could lead to a decline in the removal efficiency. The equations are as follows:

| 3.5 |

and

| 3.6 |

The effect of initial MB concentration (10–80 mg l−1) on the removal efficiency of MB was also investigated (figure 6c). When the BS concentration increased from 10 to 80 mg l−1, the removal efficiency of MB showed an obvious decrease from 100% to 72.41%, with pseudo-first-order kinetic constants reduced from 0.2113 to 0.0251 m−1, which suggests that the MB removal relied on the active sites on the surface of LaFeO3-RM (figure 6e). When the concentrations were low, MB molecules could quickly be adsorbed on the spare active sites and degraded. However, with the increased MB concentration, active sites of LaFeO3-RM were overloaded so that new MB molecules could only enter the sites after MB molecules that previously occupied the site were degraded. Therefore, in the case of pollutant concentration (60 mg l−1), 88.19% of MB was removed in 60 min under neutral conditions (pH = 7), with a small initial dosage of LaFeO3-RM (0.5 g/L) and an initial concentration of BS of 10 mM.

3.4. Feasibility of the LaFeO3-RM/BS system

It is well known that natural water contains a wide range of inorganic ions and humic acids (HA), which may affect the degradation process in AOPs [54]. In order to evaluate the feasibility of the LaFeO3-RM/BS system, the effect of inorganic anions (Cl−, , ) and HA on the removal efficiency of MB was investigated. As shown in figure 6f, the removal efficiency of MB hardly changed with increased ion concentrations of Cl− and . However, the removal efficiency of MB was significantly decreased when concentrations increased from 0 to 10 ppm. This was due to the fact that could react with free radicals to form lower active species ( ) (equation (3.7)), resulting in a decrease in MB degradation [54]. In addition, the removal of MB was inhibited with increased HA concentrations because HA could also quench free radicals to slow down the reaction [55]. In conclusion, the LaFeO3-RM/BS system still showed a relative high degradation efficiency despite all the effects, indicating its great feasibility for real wastewater.

| 3.7 |

3.5. Mechanisms studies

As reported, OH· and were the main active radicals in the BS activation system. Therefore, to determine the active radicals in the reaction, TBA and methanol (MeOH) were selected as specific radical scavengers for the quenching experiment. MeOH was used to scavenge both OH· and (kOH· = 0.8–1 × 109 M−1 s−1, KSO4·− = 0.9–1.3 × 107 M−1 s−1), but TBA was only used to scavenge OH· (kOH· = 3.8–7.6 × 108 M−1 s−1, KSO4·− = 4.0–9.1 × 105 M−1 s−1) [56]. As shown in figure 7a, when the molar ratios of MeOH/BS and TBA/BS were 50 : 1, the degradation efficiency of MB decreased by 58.93% and 2.49% within 60 min, respectively, compared with the control group, indicating that the main active radical involved in the system was .

Figure 7.

The effect of radical scavengers and O2 on MB degradation (a); XPS survey spectrum of used LaFeO3-RM before and after reaction (b); high-resolution XPS spectrum of LaFeO3-RM before and after reaction for La 3d (c), Fe 2p (d), O (e), N (f) and S (j).

In addition, the removal efficiency of the LaFeO3-RM/BS system under anaerobic conditions using a sealed conical flask was measured under the same experimental conditions. As shown in figure 7a, the removal efficiency was only 19.63%, with no obvious catalytic effect observed. By measuring the dissolved oxygen in the reaction process, it was found that the content of dissolved oxygen at 3 min in the normal system (5.4 mg l−1 O2) was nine times higher than in the sealed system (0.6 mg l−1 O2). This shows that O2 was involved in the reaction, which was ascribed to the abundant dissolved oxygen provided by the mechanical stirring impeller. The result indicates that dissolved oxygen was an essential factor for the generation of in the BS activation system [14]. Moreover, the leaching of Fe in the solution after the reaction was measured by ICP-OES. The leaching concentrations of Fe were low (0.042 mg l−1), suggesting that the reaction mainly occurred on the surface of LaFeO3-RM [29].

In order to further explore the mechanism of the LaFeO3-RM/BS system, the XPS analysis of LaFeO3-RM after the reaction is shown in figure 7b–f [29]. In the La 3d spectrum, the BE and full width at half maximum of peaks of LaFeO3-RM remained unchanged after the reaction, suggesting the unchanged valence state of La in the reaction (figure 7c). However, in the Fe 2p spectrum shown in figure 7d, the peaks at 710.1 eV for Fe 2p3/2 and 723.7 eV for Fe 2p1/2 were attributed to Fe(II), while the peaks at 711.8 eV for Fe 2p3/2 and 725.4 eV for Fe 2p1/2 were assigned to Fe(III). The relative amount of Fe(II) increased to 52.3% after reaction, indicating the Fe(III) in LaFeO3-RM played a key role in the activation of BS by the redox cycle of Fe(III)/Fe(II) [57–59]. As expected, the chemically adsorbed oxygen (OH−) of LaFeO3-RM decreased from 90.3% to 74.7% after the reaction, suggesting that chemically adsorbed oxygen directly or indirectly participated in the reaction, which further proved the importance of chemically adsorbed oxygen in the removal process.

Figure 7f–j shows that the peaks at 399.2 eV and 400.2 eV were attributed to N-C and N-H, respectively, while the peaks at 163.9 eV for S 2p3/2 and 165.1 eV for S 2p1/2 were attributed to thiol (R-SH). These bonds of N and S could be derived from the degradation products of the MB molecule (figure 7b), indicating that the reaction mainly occurred on the surface of LaFeO3-RM with the MB molecule first absorbed on the surface and then degraded.

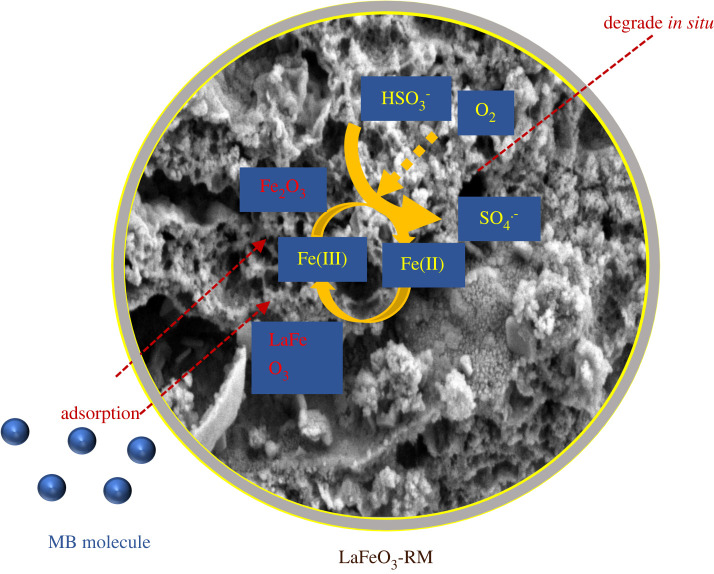

According to the experimental results above, we propose the removal mechanism of MB by the LaFeO3-RM/BS system as follows (figure 8). First, MB molecules were adsorbed on the surface of LaFeO3-RM. Then, BS in the solution aggregated on the surface of LaFeO3-RM and reacted with Fe(III) to generate , while Fe(III) was converted to Fe(II) (equation (3.8)) [60]. Subsequently, reacted with O2 to generate and then reacted with BS to generate (equations (3.9–3.10)) [61]. At the same time, Fe(II) reacted with the generated to further generate and Fe(III) (equation (3.11)), which eliminated the effect of excess Fe(II) on the reaction, and formed the redox cycle of Fe(III)/Fe(II) [62]. Therefore, the MB molecules gathered on the surface were degraded in situ by .

| 3.8 |

| 3.9 |

| 3.10 |

| 3.11 |

Figure 8.

The mechanism of MB removal in the LaFeO3-RM/BS system.

3.6. Mineralization, reusability and stability of LaFeO3-RM

The COD and TOC removal of MB were 36.5% and 21.7%, respectively, indicating that MB molecules were partially mineralized. Therefore, intermediates were generated in the degradation process. Some intermediates were measured by GC-MS, and the results are shown in the electronic supplementary material, table S1. According to the generated aromatic products, the chromogenic groups such as -S- and -N(CH3)2- were destroyed [63]. However, no polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon oxidation intermediates were generated, which have a high toxicity.

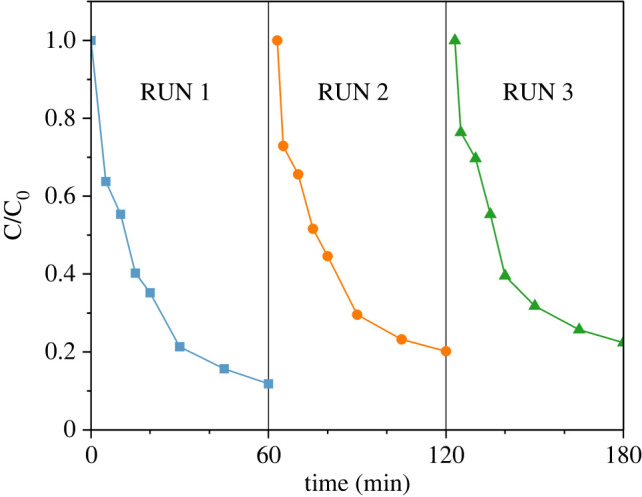

In order to investigate the reusability of LaFeO3-RM, it was washed, dried and collected for the next cycle. The results are shown in figure 9. After two and three cycles, the removal efficiency of MB was 79.89% and 77.64%, respectively, which were equivalent to 90.59% and 88.04% of the original removal efficiency. The decrease might be attributed to the residual adsorption of MB molecules on the surface of LaFeO3-RM, which blocked the active sites. Therefore, complete regeneration of the catalyst cannot be achieved through a simple washing process.

Figure 9.

The reusability of the catalyst.

In addition, the leaching of metal ions in the solution after the reaction was measured by ICP-OES, and the results are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Concentrations of heavy metal ions in solution after reaction.

| elements | As | Co | Hg | Mn | Ni | La | Cd | Cr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| concentrations (mg l−1) | ND | ND | ND | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.03 | ND | ND | 0.05 ± 0.03 |

It was observed that the leaching concentrations of metal ions were low or undetected (less than 50 ppm), which confirmed the environmental standard formulated by China (Discharge standards of water pollutants for dyeing and finishing of the textile industry (GB4287-2012)), indicating that LaFeO3-RM is a promising synergistic catalyst with low environmental risk.

The removal efficiency of supported LaFeO3 catalysts used in different heterogeneous Fenton systems for target pollutants in previous literature are shown in table 3. Comparing the result in this work with previous literature, the LaFeO3-RM/BS system showed an effective removal of MB, suggesting the superiority of RM as a support for LaFeO3. This could be because, in addition to dispersing LaFeO3 particles, the porous RM also increased the Fe oxidation activity of LaFeO3-RM, which improved the catalytic performance in structure and chemical composition.

Table 3.

The removal efficiency of the supported LaFeO3 catalysts used in different heterogeneous Fenton systems for target pollutants.

| ref. | target pollutants |

supported LaFeO3 catalyst |

oxidant |

reaction conditions |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| type | [pollutant] (mg L−1) | support | dosage (g/L) | type | dosage (mM) | radical | pH | time (min) | degradation rate | |

| this work | MB | 60 | RM | 0.5 | BS | 10 | SO4·− | 7 | 60 | 88.19% |

| [33] | acid orange 7 | 20 | Al2O3 CeO2 |

0.1 | PMS | 200 | SO4·− | 6.7 | 120 | 86.2% |

| [32] | rhodamine B | 9.58 | mesoporous silica | 2 | H2O2 | 8.8 × 103 | OH· | 5.56 | 60 | 80% |

| MB | 60% | |||||||||

4. Conclusion

In this study, LaFeO3-RM was successfully prepared via ultrasonic-assisted sol–gel method as a synergistic catalyst for MB removal. Characteristics including SEM, BET, XRD, FTIR and XPS of LaFeO3-RM revealed that the support of RM significantly improved the catalytic performance of bulk LaFeO3 in the porous structure, Fe oxidation activity, oxygen-containing functional groups and chemically adsorbed oxygen (from 44.3% to 90.3%). The effects of different conditions on MB removal, pH, BS dosage and initial MB concentration were investigated. The results showed that the LaFeO3-RM/BS system could effectively remove MB under neutral and alkaline conditions. In addition, the enhanced removal mechanism of LaFeO3-RM/BS was proposed. MB was removed through the synergistic effect of adsorption and catalysis of LaFeO3-RM, with the MB molecule first absorbed on the surface and then degraded by , which was generated through the activation of BS by LaFeO3-RM. Chemically adsorbed oxygen of LaFeO3-RM was significantly decreased from 90.3% to 74.7%, suggesting its importance in the removal process. The cycle and leaching tests of LaFeO3-RM indicated that LaFeO3-RM is an effective and promising synergistic catalyst with repeatability and stability.

Date accessibility

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available from Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.q573n5tmw [64].

The data are provided in the electronic supplementary material [65].

Authors' contributions

Y.L.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology and writing—original draft; X.M.: conceptualization, data curation, resources and writing—review and editing; Y.P.: formal analysis, validation and visualization; C.Z.: conceptualization, formal analysis and writing—review and editing; D.P.: formal analysis, methodology, project administration, supervision and writing—review and editing; Y.W.: formal analysis, investigation, validation and visualization; B.X.: formal analysis, validation and visualization.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (grant no. 2019YFC1905600).

References

- 1.Akbari Z, Ghiaci M, Nezampour F. 2018. Encapsulation of vanadium phosphorus oxide into TiO2 matrix for selective adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solution. J. Chem. Eng. Data 63, 3923-3932. ( 10.1021/acs.jced.8b00549) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramezani F, Zare-Dorabei R. 2019. Simultaneous ultrasonic-assisted removal of malachite green and methylene blue from aqueous solution by Zr-SBA-15. Polyhedron 166, 153-161. ( 10.1016/j.poly.2019.03.033) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tehrani MS, Zare-Dorabei R. 2016. Competitive removal of hazardous dyes from aqueous solution by MIL-68(Al): derivative spectrophotometric method and response surface methodology approach. Spectrochim. Acta Part a-Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 160, 8-18. ( 10.1016/j.saa.2016.02.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tehrani MS, Zare-Dorabei R. 2016. Highly efficient simultaneous ultrasonic-assisted adsorption of methylene blue and rhodamine B onto metal organic framework MIL-68(Al): central composite design optimization. Rsc Adv. 6, 27 416-27 425. ( 10.1039/C5RA28052D) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mavinkattimath RG, Kodialbail VS, Govindan S. 2017. Simultaneous adsorption of Remazol brilliant blue and disperse orange dyes on red mud and isotherms for the mixed dye system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 18 912-18 925. ( 10.1007/s11356-017-9278-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nourozi S, Zare-Dorabei R. 2017. Highly efficient ultrasonic-assisted removal of methylene blue from aqueous media by magnetic mesoporous silica: experimental design methodology, kinetic and equilibrium studies. Desalination Water Treat. 85, 184-196. ( 10.5004/dwt.2017.21207) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu EL, Shang SM, Chiu KL. 2019. Removal of reactive dyes in textile effluents by catalytic ozonation pursuing on-site effluent recycling. Molecules 24, 2755. ( 10.3390/molecules24152755) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.David PS, Karunanithi A, Fathima NN. 2020. Improved filtration for dye removal using keratin-polyamide blend nanofibrous membranes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 45 629-45 638. ( 10.1007/s11356-020-10491-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barikbin B, Arghavan FS, Othmani A, Panahi AH, Nasseh N. 2020. Degradation of tetracycline in Fenton and heterogeneous Fenton like processes by using FeNi3 and FeNi3/SiO2 catalysts. Desalination Water Treat. 200, 262-274. ( 10.5004/dwt.2020.26061) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moumeni O, Hamdaoui O, Daoui I, Amrane F. 2020. Oxidation study of an azo dye, naphthol blue black, by Fenton and sono-Fenton processes. Desalination Water Treat. 205, 412-421. ( 10.5004/dwt.2020.26351) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ponnusami V, Vikram S, Srivastava SN. 2008. Guava (Psidium guaiava) leaf powder: novel adsorbent for removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 152, 276-286. ( 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.06.107) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin XM, Ma YW, Wang Y, Wan JQ, Guan ZY. 2015. Lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) as an effective activator for degradation of organic dyes in water in the presence of persulfate. Rsc Adv. 5, 94 694-94 701. ( 10.1039/C5RA19697C) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waclawek S, Lutze HV, Grubel K, Padil VVT, Cernik M, Dionysiou DD. 2017. Chemistry of persulfates in water and wastewater treatment: a review. Chem. Eng. J. 330, 44-62. ( 10.1016/j.cej.2017.07.132) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Zhang BT, Teng YG, Zhao JJ, Sun XJ. 2021. Heterogeneous activation of persulfate by carbon nanofiber supported Fe3O4@carbon composites for efficient ibuprofen degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 401, 123428. ( 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123428) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang S, Wang P, Yang X, Shan L, Zhang W, Shao X, Niu R. et al. 2010. Degradation efficiencies of azo dye acid orange 7 by the interaction of heat, UV and anions with common oxidants: persulfate, peroxymonosulfate and hydrogen peroxide. J. Hazard. Mater. 179, 552-558. ( 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.03.039) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan CQ, Gao NY, Fu DF, Qu LS, Cui SB. 2018. Efficient degradation of paracetamol by uv/persulfate and heat/persulfate systems. Fresenius Environ. Bullet. 27, 5201-5211. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yousefi N, Pourfadakari S, Esmaeili S, Babaei AA. 2019. Mineralization of high saline petrochemical wastewater using Sonoelectro-activated persulfate: degradation mechanisms and reaction kinetics. Microchem. J. 147, 1075-1082. ( 10.1016/j.microc.2019.04.020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pu MJ, Guan ZY, Ma YW, Wan JQ, Wang Y, Brusseau ML, Chi H. 2018. Synthesis of iron-based metal-organic framework MIL-53 as an efficient catalyst to activate persulfate for the degradation of Orange G in aqueous solution. Appl. Catalysis a-General 549, 82-92. ( 10.1016/j.apcata.2017.09.021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rong X, Xie M, Kong LS, Natarajan V, Ma L, Zhan JH. 2019. The magnetic biochar derived from banana peels as a persulfate activator for organic contaminants degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 372, 294-303. ( 10.1016/j.cej.2019.04.135) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng H, Bao JG, Huang Y, Xiang LJ, Faheem RB, Du J, Nadagouda MN, Dionysiou DD. 2019. Efficient degradation of atrazine with porous sulfurized Fe2O3 as catalyst for peroxymonosulfate activation. Appl. Cataly. B Environ. 259, 118056. ( 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118056) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milh H, Yu XY, Cabooter D, Dewil R. 2021. Degradation of ciprofloxacin using UV-based advanced removal processes: comparison of persulfate-based advanced oxidation and sulfite-based advanced reduction processes. Sci. Total Environ. 764, 144510. ( 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144510) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dou RY, Cheng H, Ma JF, Qin Y, Kong Y, Komarneni S. 2020. Catalytic degradation of methylene blue through activation of bisulfite with CoO nanoparticles. Sep. Purif. Technol. 239, 116561. ( 10.1016/j.seppur.2020.116561) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun MY, Huang WY, Cheng H, Ma JF, Kong Y, Komarneni S. 2019. Degradation of dye in wastewater by homogeneous Fe(VI)/NaHSO3 system. Chemosphere 228, 595-601. ( 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.04.182) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu J, Zhou Y, Lei JY, Ao ZM, Zhou YB. 2020. Fe3O4/graphene aerogels: a stable and efficient persulfate activator for the rapid degradation of malachite green. Chemosphere 251, 126402. ( 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126402) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu J, Zhou Y, Zhou YB. 2021. Efficiently activate peroxymonosulfate by Fe3O4@MoS2 for rapid degradation of sulfonamides. Chem. Eng. J. 422, 130126. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tchinsa A, Hossain MF, Wang T, Zhou YB. 2021. Removal of organic pollutants from aqueous solution using metal organic frameworks (MOFs)-based adsorbents: a review. Chemosphere 284, 131393. ( 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131393) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao YF, Han FM, Chen Q, Wang D, Xue D, Wang H, Pu S. 2019. Efficient degradation of diclofenac by LaFeO3-catalyzed peroxymonosulfate oxidation-kinetics and toxicity assessment. Chemosphere 218, 299-307. ( 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.11.105) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng QQ, Zhou JB, Luo WJ, Ding LD, Cai WQ. 2020. Photo-Fenton removal of tetracycline hydrochloride using LaFeO3 as a persulfate activator under visible light. Ecotoxicol Environ. Safety 198, 110661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao YF, Zhang YF, Han FM, Guo HC, Huang Y, Li RY, Qi F, Ma J. 2018. Heterogeneous activation of peroxymonosulfate by LaFeO3 for diclofenac degradation: DFT-assisted mechanistic study and degradation pathways. Chem. Eng. J. 352, 601-611. ( 10.1016/j.cej.2018.07.062) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alpay A, Tuna O, Simsek EB. 2020. Deposition of perovskite-type LaFeO3 particles on spherical commercial polystyrene resin: a new platform for enhanced photo-Fenton-catalyzed degradation and simultaneous wastewater purification. Environ. Technol. Innovat. 20, 101175. ( 10.1016/j.eti.2020.101175) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li HL, Zhu JJ, Xiao P, Zhan YY, Lv KL, Wu LY, Li M. 2016. On the mechanism of oxidative degradation of rhodamine B over LaFeO3 catalysts supported on silica materials: role of support. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 221, 159-166. ( 10.1016/j.micromeso.2015.09.034) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao P, Hong JP, Wang T, Xu XL, Yuan YH, Li JL, Zhu J. et al. 2013. Oxidative degradation of organic dyes over supported perovskite oxide LaFeO3/SBA-15 under ambient conditions. Catal. Lett. 143, 887-894. ( 10.1007/s10562-013-1026-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu SH, Lin Y, Yang CP, Du C, Teng Q, Ma Y, Zhang D, Nie L, Zhong Y. et al. 2019. Enhanced activation of peroxymonosulfte by LaFeO3 perovskite supported on Al2O3 for degradation of organic pollutants. Chemosphere 237, 124478. ( 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124478) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang SH, Jin HX, Deng Y, Xiao YD. 2021. Comprehensive utilization status of red mud in China: a critical review. J. Cleaner Prod. 289, 125136. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu DY, Wu CS. 2012. Stockpiling and comprehensive utilization of red mud research progress. Materials 5, 1232-1246. ( 10.3390/ma5071232) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoon K, Cho DW, Tsang YF, Tsang DCW, Kwon EE, Song H. 2019. Synthesis of functionalised biochar using red mud, lignin, and carbon dioxide as raw materials. Chem. Eng. J. 361, 1597-1604. ( 10.1016/j.cej.2018.11.012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang S, Ang HM, Tadé MO. 2008. Novel applications of red mud as coagulant, adsorbent and catalyst for environmentally benign processes. Chemosphere 72, 1621-1635. ( 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.05.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng Y, Wu DL, Liao CZ, Deng Y, Zhang T, Shih KM. 2016. Red mud powders as low-cost and efficient catalysts for persulfate activation: pathways and reusability of mineralizing sulfadiazine. Sep. Purif. Technol. 167, 136-145. ( 10.1016/j.seppur.2016.04.051) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ioannidi A, Oulego P, Collado S, Petala A, Arniella V, Frontistis Z, Angelopoulos GN, Diaz M, Mantzavinos D. et al. 2020. Persulfate activation by modified red mud for the oxidation of antibiotic sulfamethoxazole in water. J. Environ. Manage. 270, 110820. ( 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110820) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo ZW, Bai G, Huang B, Cai N, Guo PR, Chen L. 2021. Preparation and application of a novel biochar-supported red mud catalyst: active sites and catalytic mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 408, 124802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li YY, Zhou YB, Zhou Y, Lei JY, Pu SY. 2018. Cyclodextrin modified filter paper for removal of cationic dyes/Cu ions from aqueous solutions. Water Sci. Technol. 78, 2553-2563. ( 10.2166/wst.2019.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horikawa T, Do DD, Nicholson D. 2011. Capillary condensation of adsorbates in porous materials. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 169, 40-58. ( 10.1016/j.cis.2011.08.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muhammad S, Saputra E, Sun HQ, Ang HM, Tade MO, Wang SB. 2012. Heterogeneous catalytic oxidation of aqueous phenol on red mud-supported cobalt catalysts. Indust. Eng. Chem. Res. 51, 15 351-15 359. ( 10.1021/ie301639t) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sushi S, Batra VS. 2012. Modification of red mud by acid treatment and its application for CO removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 203, 264-273. ( 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.12.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ben Hammouda S, Zhao FP, Safaei Z, Babu I, Ramasamy DL, Sillanpaa M. 2017. Reactivity of novel Ceria-Perovskite composites CeO2-LaMO3 (MCu, Fe) in the catalytic wet peroxidative oxidation of the new emergent pollutant ‘Bisphenol F': characterization, kinetic and mechanism studies. Appl. Cataly. B Environ. 218, 119-136. ( 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.06.047) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamashita T, Hayes P. 2008. Analysis of XPS spectra of Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions in oxide materials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 254, 2441-2449. ( 10.1016/j.apsusc.2007.09.063) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiao P, Zhong L, Zhu J, Hong J, Li J, Li H, Zhu Y. 2015. CO and soot oxidation over macroporous perovskite LaFeO3. Catal. Today 258, 660-667. ( 10.1016/j.cattod.2015.01.007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li XQ, Elliott DW, Zhang WX. 2006. Zero-valent iron nanoparticles for abatement of environmental pollutants: materials and engineering aspects. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 31, 111-122. ( 10.1080/10408430601057611) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mei Y, Zeng J, Sun M, Ma J, Komarneni S. 2020. A novel Fenton-like system of Fe2O3 and NaHSO3 for orange II degradation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 230, 115866. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ozkan DC, Turk A, Celik E. 2020. Synthesis and characterizations of sol-gel derived LaFeO3 perovskite powders. J. Materials Sci. Materials Elect. 31, 22 789-22 809. ( 10.1007/s10854-020-04803-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kazak O, Eker YR, Akin I, Bingol H, Tor A. 2017. A novel red mud@sucrose based carbon composite: preparation, characterization and its adsorption performance toward methylene blue in aqueous solution. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 5, 2639-2647. ( 10.1016/j.jece.2017.05.018) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun B, Guan XH, Fang JY, Tratnyek PG. 2015. Activation of manganese oxidants with bisulfite for enhanced oxidation of organic contaminants: the involvement of Mn(III). Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 12 414-12 421. ( 10.1021/acs.est.5b03111) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Das TN. 2001. Reactivity and role of SO5 center dot- radical in aqueous medium chain oxidation of sulfite to sulfate and atmospheric sulfuric acid generation. J. Phys. Chem. A 105, 9142-9155. ( 10.1021/jp011255h) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Y, Cao D, Zhao X. 2017. Heterogeneous degradation of refractory pollutants by peroxymonosulfate activated by CoOx-doped ordered mesoporous carbon. Chem. Eng. J. 328, 1112-1121. ( 10.1016/j.cej.2017.07.042) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang J, Shen M, Wang HL, Du YS, Zhou XQ, Liao ZW, Wang H, Chen Z. et al. 2020. Red mud modified sludge biochar for the activation of peroxymonosulfate: singlet oxygen dominated mechanism and toxicity prediction. Sci. Total Environ. 740, 140388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eibenberger H, Steenken S, O'Neill P, Schulte-Frohlinde D. 1978. Pulse radiolysis and electron spin resonance studies concerning the reaction of SO4.cnt- with alcohols and ethers in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. 82, 749-750. ( 10.1021/j100495a028) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang HB, Wang SX, Liu YQ, Fu YS, Wu P, Zhou GF. 2019. Degradation of diclofenac by Fe(II)-activated bisulfite: kinetics, mechanism and transformation products. Chemosphere 237, 124518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xiong X, Gan J, Zhan W, Sun B. 2016. Effects of oxygen and weak magnetic field on Fe0/bisulfite system: performance and mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Pollution Res. 23, 16 761-16 770. ( 10.1007/s11356-016-6672-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou D, Yuan Y, Yang S, Gao H, Chen L. 2015a. Roles of oxysulfur radicals in the oxidation of acid orange 7 in the Fe(III)–sulfite system. J. Sulfur Chem. 36, 373-384, 118058. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou DN, Yuan YA, Yang SJ, Gao H, Chen L. 2015b. Roles of oxysulfur radicals in the oxidation of acid orange 7 in the Fe(III)-sulfite system. J. Sulfur Chem. 36, 373-384. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang B, Liu Y, Zheng J, Tan M, Wang Z, Wu M. 2015. Synergetic transformations of multiple pollutants driven by Cr(VI)–sulfite reactions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 12 363-12 371. ( 10.1021/acs.est.5b03275) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang Y, Sun MY, Zhou J, Ma JF, Komarneni S. 2020. Degradation of orange II by Fe@Fe2O3 core shell nanomaterials assisted by NaHSO3. Chemosphere 244, 125588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Q, Tian SL, Ning P. 2014. Degradation mechanism of methylene blue in a heterogeneous fenton-like reaction catalyzed by ferrocene. Indust. Eng. Chemistry Research 53, 643-649. ( 10.1021/ie403402q) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li Y, Meng X, Pang Y, Zhao C, Peng D, Wei Y, Xiang B. 2022. Data from: Activation of bisulfite by LaFeO3 loaded on red mud for degradation of organic dye. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.q573n5tmw) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Li Y, Meng X, Pang Y, Zhao C, Peng D, Wei Y, Xiang B. 2022. Activation of bisulfite by LaFeO3 loaded on red mud for degradation of organic dye. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6292524) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Li Y, Meng X, Pang Y, Zhao C, Peng D, Wei Y, Xiang B. 2022. Data from: Activation of bisulfite by LaFeO3 loaded on red mud for degradation of organic dye. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.q573n5tmw) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Meng X, Pang Y, Zhao C, Peng D, Wei Y, Xiang B. 2022. Activation of bisulfite by LaFeO3 loaded on red mud for degradation of organic dye. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6292524) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]