Abstract

A substantial minority of adolescents experience and use dating violence in their sexual and/or romantic relationships. Limited attention has been paid to exploring theory-driven questions about use and experience of adolescent dating violence (ADV), restricting knowledge about promising prevention targets for diverse groups of youth. To address this gap, this paper investigates whether factors tied to power imbalances (bullying, risk of social marginalization) are associated with patterns of ADV victimization and perpetration in a large sample of Canadian mid-adolescents. We used data from the 2017/2018 Health-Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC) study, a nationally representative sample of Canadian youth. Our study was comprised of adolescents who were in grades 9 or 10, and who had dated in the past 12 months (N = 3779). We assessed multiple forms of ADV and bullying victimization and perpetration. We also included six variables assessing adolescents’ risk of social marginalization: gender, race/ethnicity, immigration status, family structure, food insecurity, and family affluence. We used latent class analysis to explore the ways adolescents experience and use different forms of ADV, and then examined whether factors tied to power imbalances (bullying, social marginalization) were associated with classes of ADV. Three ADV classes emerged in our sample: uninvolved (65.7%), psychological and cyber victimization only (28.9%), and mutual violence (5.4%). Bullying was most strongly associated with the mutual violence class, suggesting a transformation of power from peer to romantic contexts. Social marginalization variables were associated with ADV patterns in different ways, highlighting the need to use a critical and anti-oppressive lens in ADV research and prevention initiatives.

Keywords: dating violence, bullying, adolescent, social marginalization, power

Dating violence is a prevalent issue during adolescence, with approximately 20% of adolescents aged 11-18 experiencing physical dating violence, 22% experiencing psychological dating violence, and 9% experiencing sexual dating violence (Exner-Cortens et al., 2021; Wincentak et al., 2017; Ybarra et al., 2016). Adolescent dating violence (ADV) is also associated with a number of negative health outcomes, including depressive symptoms, psychological complaints, and substance use (Bonomi et al., 2013; Exner-Cortens et al., 2013, 2017). Given the prevalence and negative repercussions of ADV, the purpose of this paper is to better understand patterns of ADV with the intent to inform prevention efforts for diverse groups of youth. Specifically, the majority of ADV research has been epidemiological in nature, with limited attention paid to exploring theory-driven questions about use and experience of ADV (Exner-Cortens, 2014). Theory-driven research is needed to more holistically understand risk for ADV victimization and perpetration. In this paper, we thus investigate whether factors inherently tied to social power imbalances (bullying, social marginalization) are associated with patterns of dating violence victimization and perpetration, to advance theoretical understandings of ADV.

ADV and Social Power Relations

Limited theory exists that seeks to explain ADV specifically (Exner-Cortens, 2014). However, two common perspectives on why ADV occurs are derived from feminist and developmental theory. Feminist theories of interpersonal violence suggest that imbalances of power and control that exist between men and women/other marginalized genders in patriarchal societies (like Canada and the United States) are a root cause of interpersonal violence (Reed, Raj, et al., 2010). Specifically, when men and non-men (e.g., women, trans+, non-binary, genderqueer) genders are unequal at the societal level, inequitable gender norms reinforce the notion of male superiority/non-male inferiority within interpersonal relationships, with the result that men believe they can use violence against women and other marginalized genders as a means of power and control (Connell, 1987; Dobash & Dobash, 2003). Thus, ADV as understood through feminist theory generally centers relationships that are typically characterized by one-way aggression (i.e., cisgender boy perpetrators /cisgender girl and other marginalized gender victims, with mutual violence resulting from self-defense), and where violence may be more severe in nature (e.g., coercive control, severe physical violence, sexual violence, stalking).

A second perspective on why ADV occurs arises from developmental theory on adolescent cognitive and social-emotional development. According to the dual-systems model of cognitive development (Shulman et al., 2016), adolescents’ socioemotional system (involved in risk-taking and emotion regulation) develops before the cognitive control system, meaning adolescents are prone to exhibit more impulsive behavior and less emotional stability than adults. In addition, adolescents are continuing to build their conflict negotiation skills, which may be worse in the new developmental setting of romantic relationships, as compared to peer and family relationship settings (Baker & Exner-Cortens, 2020). In sum, developmental perspectives generally suggest that the ongoing development of cognitive control and conflict negotiation skills in adolescence may (in part) underlie ADV, resulting in one-way or mutual aggression where all genders may perpetrate and experience typically less severe forms of violence (e.g., name-calling, pushing/shoving).

As with most theories seeking to explain complex human behavior, it is likely that different perspectives are valid for different youth in different contexts. Using a person-centered approach may allow for a more nuanced understanding of ADV in both developmental and social context, and may help to reconcile long-standing debates in the ADV field about differences in patterns of violence (e.g., rates of violence by gender) by incorporating multiple theoretical perspectives. Unfortunately, there is limited research to date that has explored patterns of ADV from a person-centered and theoretical perspective. In the most relevant research to date, Zweig et al. (2014) examined whether Johnson’s four-part typology of adult intimate partner violence (i.e., situational couple violence; intimate terrorism; violent resistance; mutual violent control) also applied to ADV. In their sample of over 3000 youth from the Northeastern United States, they found that approximately one in three boys and girls had experienced and/or used ADV. Of these, most (86% of girls and 80% of boys) were in relationships characterized by situational couple violence (i.e., relationships characterized by physical violence without power and control dynamics). A minority were in relationships characterized by intimate terrorism (i.e., violent relationships characterized by one-way power, control, and perpetration; 7% of girls and 11% of boys); violent resistance (i.e., relationship were both partners use violence, but where only one partner is using power and control, and the other partner is resisting the violence by fighting back; 6% of girls and 6% of boys); and mutual violent control (i.e., violent relationships where both partners use power and control; 1% of girls and 4% of boys).

Bullying

Informed by both developmental and feminist theory, as well as the findings of Zweig et al. (2014), we hypothesize that power relations may be central to what differentiates adolescents reporting different patterns (i.e., victimization and/or perpetration) of ADV. We further hypothesize that one way to understand connections between power relations and patterns of ADV is to explore the relationship between patterns of ADV and bullying, as bullying is a relationship problem centered in power differentials (Espelage et al., 2022; Pepler et al., 2008). Specifically, a defining characteristic of bullying is a power imbalance, where the youth who bullies holds power (physically and/or socially) over the youth being victimized (Holt & Espelage, 2007; Olweus, 1993; Pouwels et al., 2018; Smith, 2016), and uses the bullying behavior to access available power within their social context (Vaillancourt et al., 2008). This power imbalance can stem from many different levels of the social ecology (i.e., the individual level, the interpersonal level, the community level and/or the societal level; (Dahlberg & Krug, 2002)). For example, a power imbalance might exist because one youth is physically larger than the other, or because the youth lives in a society (like Canada and the US) where White supremacy is the underlying cultural system that defines race relations (Espelage et al., 2022). Thus, since bullying results from the use of power and aggression in interpersonal relationships, it is possible that the developmental transfer of this use of power from the peer context to the romantic relationship context—along with adolescents’ developing capacities for conflict negotiation and cognitive control—may result in experiences with ADV (Pepler et al., 2008). Longitudinal, empirical research supports this conjecture. For example, Humphrey and Vaillancourt (2020) collected data from a Canadian sample of 608 adolescents every year from ages 10-19. They found that adolescents who bullied their peers during adolescence continued to assert power and control over other individuals in various contexts (i.e., dating violence in adulthood). In a recent review article, Espelage et al. (2022) also describe longitudinal research demonstrating connections between use of bullying and future perpetration of sexual violence in adolescence.

Social Marginalization

A second way to understand connections between power relations and patterns of ADV is to explore social marginalization, or the social, political and economic exclusion many groups experience due to unequal societal-level power relations (NCCDH, 2020). This understanding is rooted in anti-oppression, or an approach to research, practice and prevention that situates ADV within the larger social context of intersecting oppressions (e.g., racism, sexism, colonialism; (Crenshaw, 1991)), and that works towards health equity through addressing root causes of disparities (UBC, n.d.). From an anti-oppressive, critical theory perspective, then, power is seen as rooted in social structures that marginalize youth based on aspects of their identity (e.g., Bell, 1995; Collins, 2017; Crenshaw, 2017). These macro-level power inequities are critical to consider when studying ADV, but have infrequently been the focus of research (Debnam & Temple, 2021). Indeed, due to the paucity of research on social marginalization and ADV (Exner-Cortens et al., 2021), we do not have specific hypotheses about how structural oppression (and related social disempowerment) is related to patterns of ADV, with one exception: per feminist theory and its extensive application to understanding patterns of violence, we hypothesize that cisgender boys will be more likely to be in a group that uses (i.e., perpetrates) but does not experience multiple forms of ADV, as compared to cisgender girls and non-binary youth, who will be more likely to be in a group that experiences (i.e., victimization) multiple forms of ADV (Reed, Raj, et al., 2010).

Current Study

In sum, past research suggests that different patterns of ADV exist for different subgroups of youth, and we hypothesize that taking an approach guided by an understanding of power relations might help us explore these patterns. To meet the purpose of this study (i.e., exploring patterns of ADV in a large, nationally representative sample of Canadian adolescents), we will pursue two study aims.

The first aim of our study is to explore the various ways in which adolescents might experience and use dating violence in our sample (e.g., perpetration only, mutual violence). To do this, we will use a person-centered approach to explore patterns of ADV. Some other recent studies have utilized person-centered approaches (e.g., LCA, cluster analysis) to examine subgroups of adolescents with regard to patterns of violence in the romantic context (e.g., Couture et al., 2021; French et al., 2014; Martin-Storey et al., 2021; Sessarego et al., 2021; Siller et al., 2022; Théorêt et al., 2021; Thulin et al., 2020), but with varying findings. Based on this prior work, we hypothesize that four ADV patterns will emerge in our sample: perpetration only, victimization only, mutual violence, and uninvolved (e.g., not engaging in ADV).

The second aim of our study is to investigate if factors inherently tied to power imbalances are associated with patterns of dating violence emerging from Aim One. To do this, we will investigate whether 1) bullying involvement and 2) risk of1 social marginalization—both of which are related to power differentials—are associated with ADV class membership. Guided by research showing violence in one context (i.e., bullying in peer relationships) may transfer to violence in other contexts (i.e., dating violence in romantic relationships) (Espelage et al., 2022; Humphrey & Vaillancourt, 2020), we hypothesize that bullying perpetration will be associated with membership in an ADV perpetration only class. We also hypothesize that bullying victimization will be associated with membership in an ADV victimization only class. For risk of social marginalization and per our prior work with these data (Exner-Cortens et al., 2021), we will examine whether gender, race/ethnicity, immigration status, family status, food insecurity, and/or socioeconomic status are associated with ADV class membership. These variables reflect social marginalization due to sexism and transphobia, racism, xenophobia, and classism, respectively. As noted above, we hypothesize that cisgender boys will be more likely to be in an ADV perpetration only group as compared to cisgender girls, and that cisgender girls will be more likely to be in an ADV victimization only group as compared to cisgender boys. Given prevalent transphobia in Canada (Bellemare et al., 2021; Longman Marcellin et al., 2013), we also hypothesize that non-binary youth will be more likely to be in an ADV victimization only group as compared to cisgender youth. All other analyses under this aim are exploratory.

Method

Data

We use data from the 2017/2018 Health-Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC) dataset. 21,750 Canadian youth completed anonymous paper-based surveys in 2018. Youth were in grades 6-10 and from all 10 provinces and two territories.

Sample

For this paper, we used an analytic sample restricted to adolescents who 1) were in grades 9 and 10 (as only these individuals were asked about ADV; n = 8462); and 2) consistently reported dating experience in the past 12 months across all ADV items (n = 3779). By consistently reported dating, we mean that for each ADV item, the participant indicated they had been in a dating relationship in the past 12 months, and not that they were in a consistent dating relationship over the past year. Following the application of sample weights, our final weighted sample size for descriptive analyses was n = 3636.

Measures

Adolescent Dating Violence (ADV) Perpetration and Victimization

Three items on the HBSC survey assessed ADV perpetration in the past 12 months. For psychological perpetration, youth were asked if they tried to “control or emotionally hurt someone you were dating or going out with.” For physical dating violence perpetration, youth were asked if they “physically hurt on purpose someone you were dating or going out with.” For cyber dating violence perpetration, youth were asked if they “used social media to hurt, embarrass, or monitor someone you were dating.” An identical three items were used to assess ADV victimization in the past 12 months. Dating violence questions were adapted from several existing ADV measures (Exner-Cortens et al., 2021).

Response options for all victimization and perpetration items were 0 times, 1 time, 2 or 3 times, 4 or 5 times, or 6 or more times; participants could also indicate that they did not date or go out with anyone during the past 12 months. For analyses, responses were dichotomized as 0 = no dating violence and 1 = any dating violence, as is typical when reporting ADV prevalence data (e.g., Farhat et al., 2015). Youth who reported that they did not date or go out with anyone in the past 12 months were excluded from analysis.

Bullying Perpetration and Victimization

Eight items on the HBSC survey assessed various types of bullying perpetration. First, youth were asked how often in the past couple of months they had taken part in bullying another student at school (i.e., in general). Second, youth were asked about their participation in specific bullying types at school: verbal bullying (calling another student(s) mean names, and made fun of, or teased him or her in a hurtful way), social exclusion bullying (kept another student(s) out of things on purpose, excluded him or her from group of friends, or completely ignored him or her), physical bullying (hit, kicked, pushed, shoved around, or locked another student(s) indoors), relational bullying (spread false rumors about another student(s) and tried to make others dislike him or her), weight bullying (made fun of another student(s) because of their body weight), and sexual bullying (made sexual jokes, comments, or gestures to another student(s)). Finally, youth were asked if they had taken part in cyberbullying in the past couple of months. Eight identical items were used to assess bullying victimization in the past couple of months. Prior to these items, students were given a definition of bullying that specifically highlighted power differentials (i.e., “The person that bullies has more power than the person being bullied and wants to cause harm to him or her. It is not bullying when two people of about the same strength or power argue or fight”).

Response options for the victimization and perpetration items were once or twice, 2 or 3 times a month, about once a week, or several times a week; participants could also indicate that they did bully another student/were not themselves bullied in this way in the past couple of months. For cyber and specific bullying types (verbal, social exclusion, physical, relational, weight, sexual) responses were dichotomized as 0 = no bullying perpetration/victimization and 1 = any bullying perpetration/victimization (i.e., once or twice or more), as is typically done with HBSC data (e.g., Deryol et al., 2022). However, since school bullying was a general question that could potentially include various subtypes of bullying behavior (i.e., youth’s reports of school bullying could include instances of verbal bullying, physical bullying, etc.), and because base rates for overall school bullying were higher as compared to subtypes of bullying, responses for this item were dichotomized as 0 = 0 to 1 or 2 times and 1 = 2 or 3 times a month or more.

Social Marginalization

We used six variables to assess adolescents’ risk of social marginalization: gender, race/ethnicity, immigration status, family structure, food insecurity, and socioeconomic status. Due to issues with sample size, we dichotomized the first four variables for analyses: gender (0 = male, 1 = female); race/ethnicity (0 = white, 1 = racialized); immigration status (0 = second, third, or more generation, 1 = first generation); and family structure (0 = two parent home, 1 = single parent/other). For gender, we note that youth were asked “Are you male or female?” and were provided with response options of “male,” “female,” or “neither term describes me” (non-binary). However, due to the small sample size in the non-binary category (Exner-Cortens et al., 2021), we were only able to investigate differences between cisgender boys and girls in Aim 2 analyses. Food insecurity was assessed by asking how often the participant went to bed hungry because there was not enough food at home (1=always to 4=never). For analysis, we dichotomized this variable into yes (1=always, often or sometimes) and no (0=never). Socioeconomic status was measured using the Family Affluence Scale (Schnohr et al., 2013). We summed scores to create a Family Affluence score, with higher scores indicating greater affluence.

Demographics

We also explored age as a predictor of latent profiles for Aim 2 analyses, per past research demonstrating changes in ADV prevalence with age (e.g., Orpinas et al., 2013).

Analysis

We conducted all analyses in SPSS V24 and Mplus 8. We weighted descriptive analyses for proportional representation by province/territory (total weighted n = 3636). To investigate patterns of violence among youth (Aim 1), we conducted latent class analysis in Mplus 8. Based on previous work using these data (Exner-Cortens et al., 2021), we tested a series of latent class models with two to four classes. Using an iterative process, we used goodness of fit indices (Bayesian Information Criterion [BIC] and Sample Size Adjusted BIC), likelihood ratio tests (Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test [LMR LRT]), and interpretability to select the model solution (Li, 2017). For Aim 2, we used multinomial logistic regression analysis to examine associations between bullying and risk of social marginalization variables with the likelihood of ADV class membership.

Results

Descriptives

Adolescents were, on average, 15.3 years old (SD = .67) and were all in grades 9 (52.6%) and 10 (47.4%). Participants were fairly evenly split between cisgender girls (54.4%) and boys (43.6%). The sample was majority White (72.3%), though there was representation from adolescents who identified as Black (3.1%), Latin American (2.1%), Indigenous (2.9%), Asian (7.9%), or other (including multiracial, 11.7%). The racial/ethnic breakdown in our sample generally reflects the youth population of Canada as a whole, though Indigenous youth were under-represented (Exner-Cortens et al., 2021). Most adolescents lived in two parent households (79.2%), while 11.6% reported being first-generation immigrants. Almost one in four adolescents reported food insecurity (22.2%).

The overall prevalence of any use (i.e., perpetration) of ADV was 9.2% for psychological aggression (n = 334), 7.7% for cyber aggression (n = 280), and 7.1% for physical aggression (n = 257). The overall prevalence of any experience (i.e., victimization) of ADV was 27.3% for psychological aggression (n =994), 17.1% for cyber aggression (n = 622), and 11.5% for physical aggression (n = 420). In this sample, 19.3% (n = 703) of youth reported bullying others at school (i.e., perpetration) at least 2-3 times a month, and 33.2% (n = 1207) reported experiencing school bullying (i.e., victimization) at least 2-3 times a month. Overall prevalence for use of cyber bullying (i.e., any perpetration) was 8.6% (n = 312), and 18.3% (n = 667) for experiencing cyber bullying (i.e., any victimization). For more information on prevalence of subtypes of school bullying perpetration and victimization, see Supplemental Material Tables 1 and 2.

Aim 1: Latent Class Analysis

To investigate patterns of ADV in this sample, we conducted a latent class analysis in Mplus 8. Supplemental Material Table 3 summarizes fit statistics for the two to four class solutions. After assessing when BIC and ABIC model fit indices began to level off (Giang & Graham, 2008) and the Lo-Mendell Rubin Adjusted LRT Test Value (if the p values is <.05, the more complex model is the one to be retained; if the p value is >.05, the simpler model is the one to be retained; Li, 2017), we selected a 3-class solution. Given that LCA is prone to estimating too many latent classes (especially common for five- and six-class solutions), we followed guidelines (e.g., avoid larger models; use tight convergence criterion; test multiple start values) to keep the number of latent classes as few as necessary to fit the data (Uebersax, 2000).

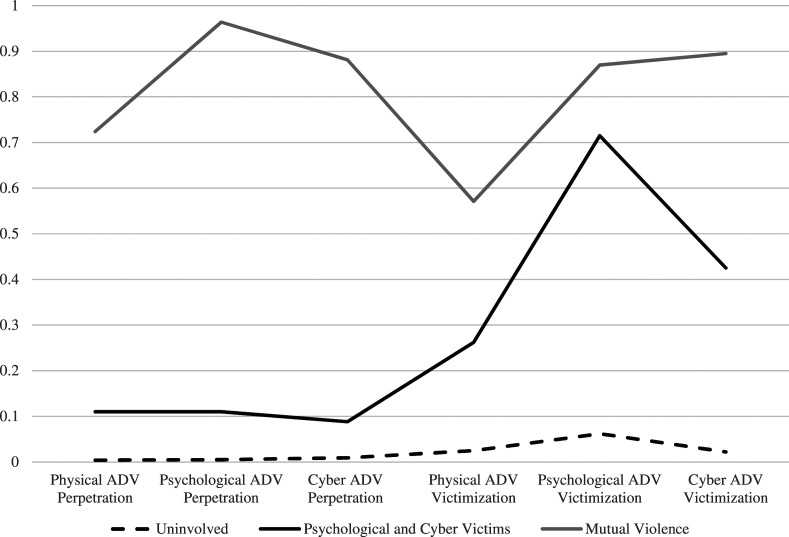

Figure 1 depicts item probabilities per class. Greek letter rho (ρ) will be used to refer to estimated item response probabilities for each class. The three classes are labeled as follows: 1) uninvolved youth, 2) youth experiencing psychological and cyber victimization only, and 3) youth engaging in mutual violence. Overall, 65.7% (n = 2483) of adolescents fell into the uninvolved class, with a low probability of experiencing or using any ADV (ρ ranged from .00 – .06). An additional 28.9% (n = 1092) were classified as experiencing psychological and cyber victimization only. Youth in this class had a high probability of being a victim of psychological ADV (ρ = .72), and a moderately high probability of being a victim of cyber ADV (ρ = .43). Finally, 5.4% (n = 204) of participants were classified as being in a mutual violence class; these adolescents had a high probability of experiencing and using multiple forms of both ADV (ρ ranged from .57 - .96, though most ρ were >.87).

Figure 1.

Response Patterns for Final Three-Class Solution. Note. Y-axis displays estimated item response probabilities for each class (Greek letter rho [ρ]).

Aim 2: Associations between Latent Classes, Bullying, and Social Marginalization

We used multinomial logistic regression to examine the association of bullying, risk of social marginalization, and age with the likelihood of membership in each of the three identified classes (Table 1). In analyses where the uninvolved class was the reference group for predicting membership in the psychological and cyber victimization only class, we found associations with both bullying and risk of social marginalization variables. For bullying, we found that both bullying perpetration and bullying victimization of all types (with the exception of weight bullying perpetration) increased the odds of being classified in the psychological and cyber victimization only class as compared to the uninvolved class. In analyses investigating risk of social marginalization, we found that cisgender girls and youth who reported food insecurity were more likely to be categorized in the psychological and cyber victimization only class as compared to the uninvolved class. In addition, as family affluence scores increased, youth had lower odds of being classified in the psychological and cyber victimization only class as compared to the uninvolved class. Finally, we found that older youth were more likely to be in the psychological and cyber victimization only class as compared to the uninvolved class.

Table 1.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Estimating the Relative Odds of Class Membership Given Bullying and Social Marginalization Indicators (N = 3779).

| Variable | Psychological/Cyber Victimization Only vs. Uninvolved OR [95% CI] | Mutual Violence vs. Uninvolved OR [95% CI] | Mutual Violence vs. Psychological/Cyber Victimization Only OR [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bullying Perpetration | |||

| School | 1.88 [1.23–2.89] | 5.67 [3.58–8.98] | 3.01 [1.64–5.52] |

| Verbal | 1.69 [1.21 – 2.35] | 3.71 [2.29 – 6.02] | 2.20 [1.23 – 3.92] |

| Social exclusion | 1.48 [1.03 – 2.13] | 4.80 [3.00 – 7.67] | 3.24 [1.87 – 5.59] |

| Physical | 1.67 [1.03 – 2.72] | 7.60 [4.63 – 12.48] | 4.55 [2.50 – 8.29] |

| Relational | 1.79 [1.09 – 2.96] | 8.02 [4.74 – 13.56] | 4.47 [2.45 – 8.18] |

| Weight | 1.24 [.69–2.25] | 6.60 [4.11 – 10.59] | 5.30 [2.78 – 10.12] |

| Sexual | 1.67 [1.12 – 2.46] | 4.66 [2.90 – 7.48] | 2.81 [1.60 – 4.94] |

| Cyber | 2.20 [1.25 – 3.89] | 8.59 [4.87 – 15.17] | 3.91 [2.11 – 7.23] |

| Bullying victimization | |||

| School | 3.43 [2.50 – 4.70] | 3.67 [2.24 – 6.00] | 1.07 [.60–1.92] |

| Verbal | 3.46 [2.50 – 4.78] | 2.48 [1.52 – 4.04] | .72 [.40–1.30] |

| Social exclusion | 3.09 [2.89 – 4.17] | 3.30 [1.99 – 5.47] | 1.07 [.59–1.92] |

| Physical | 1.83 [1.23 – 2.74] | 4.50 [2.67 – 7.60] | 2.45 [1.36 – 4.43] |

| Relational | 4.67 [3.46 – 6.31] | 6.33 [3.88 – 10.32] | 1.35 [.78–2.35] |

| Weight | 2.04 [1.47 – 2.82] | 5.10 [2.80 – 9.29] | 2.51 [1.32 – 4.76] |

| Sexual | 3.44 [2.49 – 4.74] | 4.72 [2.87 – 7.46] | 1.37 [.78–2.42] |

| Cyber | 4.02 [2.87 – 5.63] | 6.28 [3.66 – 10.79] | 1.56 [.87–2.80] |

| Social marginalization | |||

| Gender | 2.00 [1.48 – 2.70] | 1.09 [.68–1.75] | .55 [.31 – .96] |

| Race/ethnicity | 1.01 [.74–1.38] | 2.70 [1.62 – 4.49] | 2.67 [1.54 – 4.64] |

| Immigration status | .81 [.49–1.35] | 3.19 [1.86 – 5.46] | 3.93 [1.97 – 7.84] |

| Family structure | .74 [.53–1.04] | 1.10 [.61–1.98] | 1.10 [.61–1.98] |

| Family affluence | .92 [.87 – .96] | .98 [.89–1.07] | 1.06 [.96–1.17] |

| Food insecurity | 2.55 [1.83 – 3.55] | 4.42 [2.53 – 7.71] | 1.74 [.95–3.16] |

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 1.28 [1.05 – 1.57] | 1.64 [1.14 – 2.35] | 1.28 [.85–1.93] |

Note. Uninvolved (65.7%, n = 2483) is the reference category for the first two columns, Psychological/Cyber Victimization Only (28.9%, n = 1092) is the reference for the final column. Bold denotes statistical significance (p < .05). CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

In analyses where the uninvolved class served as the reference group for predicting membership in the mutual violence class, we similarly found that both perpetration and victimization of all types of bullying increased the odds of being classified in the mutual violence class as compared to the uninvolved class. In analyses investigating risk of social marginalization, we found that racialized youth, youth who were recent immigrants, and youth experiencing food insecurity were more likely to be in the mutual violence class as compared to the uninvolved class. We also found that older youth were more likely to be in the mutual violence class as compared to the uninvolved class.

Finally, to understand differences between ADV groups, we used the psychological and cyber victimization only class as the reference group in analyses predicting membership in the mutual violence class. In analyses investigating bullying, we found that all types of bullying perpetration increased the odds of being classified in the mutual violence class as compared to the psychological and cyber victimization only class. Furthermore, youth who reported physical bullying victimization or weight bullying victimization (but not any other type of bullying victimization) were more likely to be classified in the mutual violence class as compared to the psychological and cyber victimization only class. In analyses investigating risk of social marginalization, we found that racialized youth, cisgender boys, and youth who were recent immigrants were more likely to be in the mutual violence class as compared to the psychological and cyber victimization class.

Discussion

In this nationally representative sample of Canadian youth with dating experience, we found three different patterns of ADV victimization and perpetration, and that status in these classes was associated with both bullying involvement and risk of social marginalization factors. Overall, approximately one in three youth in our sample reported involvement with some form of ADV victimization (physical, psychological, and/or cyber), one in 10 with some form of ADV perpetration, one in three with experience of school bullying, and one in five with use of school bullying.

Our Aim One hypothesis was partially supported. Specifically, we hypothesized that, based on prior theorizing on use and experience of ADV, we would find four primary patterns of violence in our latent class analysis: perpetration only, victimization only, mutual violence, and uninvolved (e.g., not engaging in ADV). However, we instead found three patterns: youth engaging in mutual violence; youth experiencing psychological and cyber victimization only; and uninvolved youth. Thus, contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find a perpetration only class. There are several reasons why we may not have found a perpetration only pattern in our data. First, adolescents in our sample were on average age 15, an age when dating violence perpetration is still emerging (Foshee et al., 2009; Orpinas et al., 2013). For example, in a sample of 588 youth, Orpinas et al. (2013) found that physical ADV perpetration increased linearly from grades 6-12 among both boys and girls. Thus, as youth in our sample were in grades 9 and 10, it may still be too early to identify patterns of perpetration (i.e., perpetration only vs. mutual violence). Per theories of adolescent-limited versus life-course-persistent use of violence, these patterns may also not be detectable till late adolescence/young adulthood (Moffitt, 2003). Second, types of violence assessed for ADV perpetration in this study were limited in severity, and we did not ask about sexual violence or stalking perpetration. Thus, it is possible that if we had asked about more severe forms of physical ADV perpetration and about sexual ADV perpetration and stalking, a perpetration only class would have emerged.

Regarding the three classes we did find, the largest class was adolescents uninvolved with ADV (the uninvolved class), which represented approximately two-thirds of our sample. Of the remaining third of the sample, most were in the cyber and psychological victimization only class, and a small minority (5.4%) were in the mutual violence class. Comparatively, using a large, representative sample of heterosexual, high school youth in Quebec (Mage = 15.92, range 14–20), Théorêt et al. (2021) found four classes of ADV involvement: a class reporting low levels of physical, psychological and sexual dating violence (40%; similar to our uninvolved class); a class reporting mutual psychological ADV (34%); a class reporting mutual psychological and physical ADV (14%); and a class reporting mutual psychological ADV and sexual victimization (girls; 12%) /mutual ADV (boys; 8%). Thus, in this sample, the uninvolved class was much smaller (66% in our sample vs. 40% in the Théorêt et al. (2021) sample), and the mutual classes much larger (5% vs. 60% respectively) than in our data. Théorêt et al. (2021) also did not find a victimization only class. Conversely, in a large sample of grade 9 and 11 heterosexual and LGBTQ2SIA+ youth from Minnesota, Martin-Storey et al. (2021) found five classes: a class reporting no/low physical, psychological (verbal) and sexual ADV involvement (92%); a class reporting high ADV victimization only (4%); a class reporting mutual psychological ADV (2%); a class reporting moderate levels of mutual ADV (1%); and a class reporting high levels of mutual ADV (<1%). Thus, in this sample, the uninvolved class was much larger (66% in our sample vs. 92% in the Martin-Storey et al. (2021) sample), and the victimization only (29% vs. 4%, respectively) class much smaller, than in our data. However, our mutual violence classes were of similar size (5% vs. 4% respectively). Together, these and our studies suggest that ADV is experienced differently in different contexts, but reveal a few common take-aways: 1) ADV is experienced by a substantial minority of youth; 2) mutual violence occurs in adolescence; 3) a perpetration-only class was not found across these three large studies, suggesting, as found by Zweig et al. (2014), that “intimate terrorism”-type ADV relationships may be rare in mid-adolescence.

For Aim 2, our hypotheses related to bullying (i.e., that certain patterns of bullying would be associated with certain patterns of dating violence) were partially supported. Since we did not find a perpetration only class, we could not assess our hypothesis around bullying involvement for this class. However, when comparing our psychological/cyber victimization only class with our mutual violence class, we did find that the former was significantly less likely to perpetrate all forms of bullying, but were equally likely to experience all forms of bullying victimization, except for physical and weight-based victimization. Thus, as we expected, 1) violence victimization in the peer context was associated with violence victimization in the romantic context and 2) adolescents who both used and experienced violence in the peer context were also more likely to both use and experience violence in the romantic context. This is in line with other research suggesting that the use of violence in the peer context transfers to the romantic context (Humphrey & Vaillancourt, 2020), and is supportive of a developmental-contextual understanding of ADV (Pepler et al., 2008).

In terms of associations with risk of social marginalization, overall, youth who were involved with any ADV (whether victimization only or mutual) were more likely to be living in poverty (as indexed by food insecurity/family affluence) than youth who did not use or experience dating violence. Our only hypothesis related to social marginalization was that cisgender boys would be more likely to be in an ADV perpetration only group as compared to cisgender girls, and that cisgender girls would be more likely to be in an ADV victimization only class as compared to cisgender boys. We did find that cisgender girls were significantly more likely to be in the psychological/cyber victimization only class as compared to those not involved in dating violence, while cisgender boys were significantly more likely to be in the mutual violence class as compared to those experiencing psychological/cyber victimization only, supporting a feminist theory interpretation of these patterns. In terms of other differences between our two involved classes, we found that youth in the mutual violence class also had significantly higher odds of being racialized and a recent immigrant (we also explored whether the intersection of race, gender and/or immigration status predicted class membership, but none of these analyses were significant).

What, then, do our Aim 2 findings say about the connection between power relations and ADV? While certainly a complex question, we argue that they allow us to think about how an individual develops power, how the development of power interacts with the larger social context, and in turn, what this development might mean for use and experience of ADV. Regarding how an individual develops power, one developmental function of peer relationships is that youth learn how to use power with similar-aged social others. Unfortunately, in many peer relationships, this developmental learning includes the use and/or experience of bullying behavior. As adolescents enter into dating relationships, they begin to explore whether and how to use power within this new interpersonal setting, and may transfer what they have learned in the peer context to the romantic context (Espelage et al., 2022; Pepler et al., 2008). Thus, the developmental story is important, and provides a different understanding of use of power than has traditionally been used in the ADV literature.

In terms of how power interacts with the larger social context, we turn to our social marginalization analysis. While researchers have frequently used the social-ecological model to understand ADV, the societal-level – and its connections to structural power imbalances – has been largely ignored (Claussen et al., 2022). However, per our findings and other recent theorizing in the field (e.g., Debnam & Temple, 2021), it is essential that we turn our attention to sociological understandings of power and what these mean for ADV. For example, because of the racism and xenophobia many racialized and recent immigrant youth face, their use of ADV in the mutual violence class may represent a way of accessing power and control in social systems that rob them of this control. In his postmodern theory of resilience, Ungar (2004) posits “for many children, patterns of deviance are healthy adaptations that permit them to survive unhealthy circumstances” (p. 6), and that, since power and control are critical for positive mental health and well-being, if youth do not have socially acceptable ways to access power, they will access this power “as best they can given the resources they have available” (p. 7). Thus, it is possible that use of violence among youth in our mutual violence class represents a way to access power and control, and that as they use violence, they also experience it (e.g., due to their partner’s self-defence). While the onus of responsibility to address racism and xenophobia should not be placed on individual adolescents, but rather the social structures and norms that perpetuate these issues, when thinking about individual adolescents, it is important that prevention and intervention efforts support youth to find “less harmful ways to construct powerful identities that bolster their experience of health without needing to hurt others” (Ungar, 2004, p. 4).

Also related to our mutual violence class findings, Garnett et al. (2014) explored the intersection of discrimination and bullying in a large sample of high school youth from Boston, finding an intersectional class (7% of their sample) that experienced high rates of identity-based bullying as well as high rates of racial, immigration-related and weight-based discrimination. High levels of perceived racial discrimination were also related to significantly higher odds of severe intimate partner violence perpetration in a sample of adult African American men living in an urban setting in the United States, with the authors concluding their findings “suggest that racial discrimination, recognized as a form of structural violence, may also contribute to other forms of violence perpetration” (Reed, Silverman, et al., 2010, p. 323). However, research on experiences of ADV among youth who experience discrimination is rare (Sankar et al., 2019), and is an area in need of significant attention.

For our victimization only class, given longitudinal associations between psychological victimization and adverse health outcomes for both boys and girls (Exner-Cortens et al., 2013), intervention for these youth is also needed. Individuals in this class were more likely than youth who were uninvolved with ADV to experience bullying victimization, but generally not more likely than youth who reported mutual violence. They were also less likely than youth in the mutual violence class to report bullying perpetration. Considering risk of social marginalization factors, compared to youth in the uninvolved class, youth in the victimization only class were more likely to be a cisgender girl and to live in poverty (as indicated by lower family affluence and more food insecurity). Compared to youth in the mutual violence class, they were only more likely to be a cisgender girl. These results suggest the importance of universal dating violence prevention, but that this work needs to incorporate socio-cultural understandings of violence. To this end, the growing use of gender-transformative programs as ADV prevention is promising (Exner-Cortens et al., 2019). As older youth in our sample were more likely to experience ADV (presumably because they had more dating opportunities), our findings also support the need to provide prevention programming before youth begin dating. Indeed, researchers advocate for prevention programming that targets violence in both the peer and romantic context early on (Joseph & Kuperminc, 2020), as these types of violence not only co-occur (see Zych et al., 2021 for a meta-analysis), but also are predictive of one another. Finally, while research has long demonstrated that youth living in poverty are more likely to experience ADV victimization (e.g., Park & Kim, 2018), we are not aware of much (if any) research that has interpreted these findings as the result of the structural marginalization associated with living in poverty (as opposed to individual- or family-level socioeconomic status), and thus this is an important area for future research, to better understand the dynamics of ADV among youth living in poverty.

Limitations

We note several limitations to the current study. First, to be conservative, our analysis sample was restricted to those who consistently reported dating across all six ADV items. Our findings are also only representative of Canadian youth who had dated in the past 12 months. Second, our data were cross-sectional and all measures were self-report, and items for ADV reflect a lower threshold of severity. Although this lower severity threshold likely resulted in higher overall prevalence of reports of dating violence, our prevalence rates map onto other studies using similar measures (e.g., Basile et al., 2020). However, this form of measurement, while common, still limits our ability to understand important differences in severity and frequency, and how these relate to both correlates and outcomes. Improving ADV measurement to incorporate these contextual aspects is a critical issue facing the field (Exner-Cortens, 2018). The self-report nature of ADV items—and related social desirability bias—may explain the lower prevalence of ADV perpetration than victimization in this sample, though effects of social desirability in dating violence reporting are not consistent (Bell & Naugle, 2007; Fernàndez-Gonzàlez et al., 2013). We also did not assess experiences of discrimination, and thus were not able to use more detailed analysis to capture experiences with social power relations. Recent research by Volk et al. (2022) and Lapierre and Dane (2020) presents social power and balance of power and aggression measures that can be considered for this work. Related, our distinction between bullying and risk of social marginalization was done for analysis purposes, but in reality, these are not necessarily distinct experiences (e.g., as we have noted, risk for bullying is tied to both developmental and social power imbalances, as in the case of identity-based bullying). Finally, due to sample size restrictions, we had to collapse our social marginalization variables into dichotomous categories, which elides important distinctions among categories within these variables (e.g., among racial/ethnic groups). We also were unable to examine class membership among non-binary youth, which is a limitation as non-binary youth are at higher risk of violence overall in this sample (Exner-Cortens et al., 2021). The 2017/18 HBSC survey also did not measure sexual orientation, as it was conducted in over 50 countries and it was not possible to ask this question in some countries. However, a question on sexual orientation will be added to upcoming HBSC data collection in Canada. While we did complete supplementary intersectional analyses (exploring ADV patterns for racialized recent immigrants, racialized boys and recent immigrant boys), we did not find any significant associations with class membership, which may be because we were underpowered to detect these effects. Specifically, although we had a large sample size, small cell sizes (e.g., the number of youth reporting ADV by racial/ethnic group and immigration status) were still an issue in our dataset, as they are in many ADV studies.

Conclusion

In this nationally representative sample of Canadian mid-adolescents with dating experience, we found three patterns of ADV involvement (victimization only, mutual violence, uninvolved), and that these patterns were differentially related to variables hypothesized to tap power differentials. The significant association between bullying victimization and perpetration with both groups that were involved with ADV (victimization only and mutual violence) supports developmental theory suggesting a transformation of violence and power as youth transition from primarily peer relationships (where they may experience/use bullying) to also participating in dating relationships (Pepler, 2012). As with prior work then, our findings suggest that youth who are involved with bullying are an important priority group for ADV prevention programs. In addition, findings from both groups highlight that it is extremely important that future universal ADV prevention incorporates a critical and anti-oppressive lens. Particularly, it is necessary that comprehensive ADV prevention begins to address root causes of violence (Crooks et al., 2019), including social inequities, in addition to the well-established focus on individual-level attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Canadian Adolescents’ Experiences of Dating Violence: Associations with Social Power Imbalances by Deinera Exner-Cortens, Elizabeth Baker, and Wendy Craigin Journal of Interpersonal Violence

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Public Health Agency of Canada for their financial support of the project. We also thank Adrian Puca and Dr. Suzy Wong from the Youth Policy and Partnership Unit, Division of Children and Youth, Public Health Agency of Canada for their partnership; William Pickett, PhD, co-principal investigator; Matt King, research director; the Joint Consortium for School Health who facilitated the research across the country; and all the students and schools who participated. Access to data was granted by the HBSC investigative team at Queen’s.

Author Biographies

Deinera Exner-Cortens, PhD, MPH, is a Tier II Canada Research Chair in Childhood Health Promotion and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology, University of Calgary. She also serves as the Scientific Co-Director of PREVNet (Promoting Relationships and Eliminating Violence Network). Her research focuses on evaluating healthy relationships/mental health promotion activities in school and community settings, developing and evaluating implementation support tools for school-based mental health/healthy relationships service delivery, and preventing adolescent dating violence.

Elizabeth (Liz) Baker, PhD, is a Research Scientist in the Department of Psychology at the University of Calgary and with PREVNet at Queen's University. Her research focuses on domestic violence, promoting youth health, and program evaluation. She also works alongside policymakers to inform evidence-based decision making for social issues.

Wendy Craig, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Psychology at Queen’s University. Dr. Craig is a leading international scientist and expert on bullying prevention and the promotion of healthy relationships. As co-founder and Scientific Co-Director of PREVNet (Promoting Relationships and Eliminating Violence Network), she has transformed our understanding of bullying and effectively translated the science into evidence-based practice, intervention, and policy and had a profound influence on communities across Canada.

Notes

We say “ risk of ” in this paper to reflect both structural and post-structural understandings of oppression (e.g., that racialized adolescents in Canada and the US experience social marginalization related to race by virtue of living in a White supremacist society, but that each individual’s experience of social marginalization will be unique to their own lived experiences and context).

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Exner-Cortens’ work was supported in part by funding from the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute and the Canada Research Chairs program. Dr. Baker was supported by an Eyes High Fellowship, University of Calgary. Dr. Craig was supported by the Public Health Agency Canada [6D016-123071/001/SS]. The funder had no role in the study design; collection, analysis or interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Deinera Exner-Cortens https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2021-1350

Elizabeth Baker https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4769-2695

Wendy Craig https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8374-5152

References

- Baker E., Exner-Cortens D. (2020). Adolescents’ interpersonal negotiation strategies: Does competence vary by context? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(4), 1039–1050. 10.1111/jora.12578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, Clayton HB, DeGue S, Gilford JW, Vagi KJ, Suarez NA, Zwald ML, Lowry R. (2020). Interpersonal violence victimization among high school students – Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Supplement, 69(1), 28–37. 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell D. A. (1995). Who’s afraid of critical race theory? (p. 893). University of Illinois Law Review. [Google Scholar]

- Bellemare A., Kolbegger K., Vermes J. (2021). Nov 7). Anti-trans views are worryingly prevalent and disproportionately harmful, community and experts warn. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/anti-transgender-narratives-canada-1.6232947 [Google Scholar]

- Bell KM., Naugle AE. (2007). Effects of social desirability on students’ self-reporting of partner abuse perpetration and victimization. Violence and Victims, 22(2), 243–256. 10.1891/088667007780477348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi A. E., Anderson M. L., Nemeth J., Rivara F. P., Buettner C. (2013). History of dating violence and the association with late adolescent health. BMC Public Health, 13, 821. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claussen C., Matejko E., Exner-Cortens D. (2022). Exploring risk and protective factors for adolescent dating violence across the social-ecological model: A systematic scoping review of reviews [Unpublished manuscript]. Department of Psychology, University of Calgary. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P. H. (2017). On violence, intersectionality and transversal politics. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(9), 1460–1473. 10.1080/01419870.2017.1317827 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W. (1987). Gender and power: Society, the person and sexual politics. Stanford University Press. 10.1093/sf/69.3.953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Couture S., Fernet M., Hébert M. (2021). A cluster analysis of dynamics in adolescent romantic relationships. Journal of Adolescence, 89(9), 203–212. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. 10.2307/1229039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. W. (2017). On intersectionality: Essential writings. The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crooks C. V., Jaffe P. G., Dunlop C., Kerry A., Exner-Cortens D. (2019). Preventing gender-based violence among adolescents and young adults: Lessons from 25 years of program development and evaluation. Violence Against Women, 25(1), 29–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg L. L., Krug E. G. (2002). Violence: A global public health problem. In Krug E., Dahlberg L. L., Mercy J. A., Zwi A. B., Lozano R. (Eds.), World report on violence and health (pp. 1–21). World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Debnam K. J., Temple J. R. (2021). Dating Matters and the future of teen dating violence prevention. Prevention Science, 22(2), 187–192 10.007/s11121-020-01169-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deryol R., Wilcox P., Stone S. (2021). Individual risk, country-level social support and bullying and cyberbullying victimization among youths: A cross-national study, 37(17–18), NP15275–NP15311. 10.1177/08862605211015226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobash R. E., Dobash R. P. (2003). Women, violence and social change. Routledge. 10.4324/9780203450734 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage D. L., Ingram K. M., Hong J. S., Merrin G. J. (2022). Bullying as a developmental precursor to sexual and dating violence across adolescence: Decade in review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(4), 1358-1370. 10.1177/15248380211043811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D. (2014). Theory and teen dating violence victimization: Considering adolescent development. Developmental Review, 34(2), 168–188. 10.1016/j.dr.2014.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D. (2018). Measuring adolescent dating violence. In Wolfe D. A., Temple J. R. (Eds.), Adolescent dating violence: Theory, research, and prevention (pp. 315–340). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D., Baker E., Craig W. (2021). The national prevalence of adolescent dating violence in Canada. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(3), 495–502. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D., Eckenrode J., Bunge J., Rothman E. (2017). Re-victimization after physical and psychological adolescent dating violence in a matched, national sample of youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(2), 176–183. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D., Eckenrode J., Rothman E. (2013). Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics, 131(1), 71–78. 10.1542/peds.2012-1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D., Wright A., Hurlock D., Carter R., Krause P., Crooks C. V. (2019). Preventing adolescent dating violence: An outcomes protocol for evaluating a gender-transformative healthy relationships promotion program. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, 16, 100484. 10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat T., Haynie D., Summersett-Ringgold F., Brooks-Russell A., Iannotti R. J. (2015). Weight perceptions, misperceptions, and dating violence victimization among US adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(9), 1511–1532. 10.1177/0886260514540804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernàndez-Gonzàlez L., O’Leary K. D., Muñoz-Rivas M. J. (2013). We are not joking: Need for controls in reports of dating violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(3), 602–620. 10.1177/0886260512455518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee V.A., Benefield T., Suchindran C., Ennett S. T., Bauman K. E., Karriker-Jaffe K. J., Reyes H. L. (2009). The development of four types of adolescent dating abuse and selected demographic correlates. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19(3), 380–400. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00593.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French B. H., Bi Y., Latimore T. G., Klemp H. R., Butler E. E. (2014). Sexual victimization using latent class analysis: Exploring patterns and psycho-behavioral correlates. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(6), 1111–1131. 10.1177/0886260513506052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett B. R., Masyn K. E., Austin S. B., Miller M., Williams D. R., Viswanath K. (2014). The intersectionality of discrimination attributes and bullying among youth: An applied latent class analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(8), 1225–1239. https://doi.org.10.1007/s10964-013-0073-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giang M., Graham S. (2008). Using latent class analysis to identify aggressors and victims of peer harassment. Aggressive Behavior, 34(2), 203–213. 10.1002/ab.20233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt M. K., Espelage D. L. (2007). Perceived social support among bullies, victims, and bully-victims. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(8), 984–994. 10.1007/s10964-006-9153-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey T., Vaillancourt T. (2020). Longitudinal relations between bullying perpetration, sexual harassment, homophobic taunting, and dating violence: evidence of heterotypic continuity. Journal of youth and adolescence, 49(10), 1976–1986. 10.1007/s10964-020-01307-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph H. L., Kuperminc G. (2020). Bridging the siloed fields to address shared risk for violence: Building an integrated intervention model to prevent bullying and teen dating violence. Aggression and violent behavior. Science Direct. (p. 101506). 10.1016/j.avb.2020.101506 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre K. R., Dane A. V. (2020). Cyberbullying, cyber aggression, and cyber victimization in relation to adolescents’ dating and sexual behavior: An evolutionary perspective. Aggressive Behavior, 46(1), 49–59. 10.1002/ab.21864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.R. (2017). November).Latent class analysis in Mplus. UCLA. [Video file]. Retrieved from. http://sites.education.uky.edu/apslap/upcoming-events/ [Google Scholar]

- Longman Marcellin R., Scheim A., Bauer G., Redman N. (2013). Mar 7). Trans PULSE e-Bulletin. Experiences of Transphobia Among Trans Ontarians. https://transpulseproject.ca/research/experiences-of-transphobia-among-trans-ontarians/ [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Storey A., Pollitt A. M., Baams L. (2021). Profiles and predictors of dating violence among sexual and gender minority adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(6), 1155–1161. Advance Online Publication. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt T. E. (2003). Life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial behavior. A 10-year research review and a research agenda. In Lahey B. B., Moffitt T. E., Caspi A. (Eds.), Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency (pp. 49–75). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health [NCCDH] (2020). Marginalized populations. Nccdh.ca. https://nccdh.ca/glossary/entry/marginalized-populations [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Blackwell. 10.1002/pits.10114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orpinas P., Hsieh H., Song X., Holland K., Nahapetyan L. (2013). Trajectories of physical dating violence from middle to high school: Association with relationship quality and acceptability of aggression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(4), 551–565. 10.007/s10964-012-9881-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Kim S. (2018). The power of family and community factors in predicting dating violence: A meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 40(May-June 2018), 19–28. 10.1016/j.avb.2018.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pepler D. (2012). The development of dating violence: What doesn’t develop, what does develop, how does it develop, and what can we do about it? Prevention Science, 13(4), 402–409. https://doi.org/s11121-012-0308-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepler D., Jiang D., Craig W., Connolly J. (2008). Developmental trajectories of bullying and associated factors. Child Development, 79(2), 325–338. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouwels J. L., Lansu T. A., Cillessen A. H. (2018). A developmental perspective on popularity and the group process of bullying. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 43(November-December 2018), 64–70. 10.1016/j.avb.2018.10.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed E., Raj A., Miller E., Silverman J. (2010. a). Losing the ‘gender’ in gender-based violence: The missteps of research on dating and intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 16(3), 348–354. 10.1177/1077801209361127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed E., Silverman J. G., Ickovics J. R., Gupta J., Welles S. L., Santana M. C. (2010. b). Experiences of racial discrimination & relation to violence perpetration and gang involvement among a sample of urban African American men. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 12(3), 319–326. 10.1007/s10903-008-9159-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankar S., McCauley H., Johnson D. J., Thelamour B. (2019). Gender and sexual prejudice and subsequent development of dating violence: Intersectionality among youth, In Handbook of children and prejudice (pp. 289–302). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Schnohr C. W., Makransky G., Kreiner S., Torsheim T., Hofmann F., De Clercq B., Currie C. (2013). Item response drift in the Family Affluence Scale: A study on three consecutive surveys of the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey. Measurement, 46(9), 3119–3126. 10.1016/j.measurement.2013.06.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sessarego S. N., Siller L., Edwards K. M. (2021). Patterns of violence victimization and perpetration among adolescents using latent class analysis. In Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(19–20), 9167–9186. 10.1177/0886260519862272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman E. P., Smith A. R., Silva K., Icenogle G., Duell N., Chein J., Steinberg L. (2016). The dual systems model: Review, reappraisal, and reaffirmation. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 17(February 2016), 103–117. 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller L., Edwards K. M., Banyard V. (2022). Violence typologies among youth: A latent class analysis of middle and high school youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(3–4), 1023–1048. 10.1177/0886260520922362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P. K. (2016). Bullying: Definition, types, causes, consequences and intervention. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(9), 519–532. 10.1111/spc3.12266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Théorêt V., Hébert M., Fernet M., Blais M. (2021). Gender-specific patterns of teen dating violence in heterosexual relationships and their associations with attachment insecurities and emotion dysregulation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(2), 246–259. 10.1007/s10964-020-01328-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thulin E. J., Heinze J. E., Kernsmith P., Smith-Darden J., Fleming P. J. (2021). Adolescent risk of dating violence and electronic dating abuse: A latent class analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50, 2472–2486. 10.1007/s10964-020-01361-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uebersax J. (2000). A brief study of local maximum solutions in latent class analysis. URL. http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/jsuebersax/local.htm [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M. (2004). The social construction of resilience. In Ungar M. (Ed.), Nurturing hidden resilience in troubled youth (pp. 3–35). University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- University of British Columbia [UBC] . (n.d.). EDI glossary. Retrieved from. https://vpfo.ubc.ca/edi/edi-resources/edi-glossary/ [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt T., Hymel S., McDougall P. (2008). Bulling is power: Implications for school-based intervention strategies. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 19(2), 157–176. 10.1300/J008v19n02_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volk A. A., Andrews N. C. Z., Dane A. V. (2022). Balance of power and adolescent aggression. Psychology of Violence, 12(1), 31–41. https://doi.rog/10.1037/vio0000398 [Google Scholar]

- Wincentak K., Connolly J., Card N. (2017). Teen dating violence: A meta-analytic review of prevalence rates. Psychology of Violence, 7(2), 224. 10.1037/a0040194 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra M. L., Espelage D. L., Langhinrichsen-Rohling J., Korchmaros J. D. (2016). Lifetime prevalence rates and overlap of physical, psychological, and sexual dating abuse perpetration and victimization in a national sample of youth. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(5), 1083–1099. 10.1007/s10508-016-0748-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweig J. M., Yahner J., Dank M., Lachman P. (2014). Can Johnson’s typology of adult partner violence apply to teen dating violence? Journal of Marriage and Family , 76(August 2014), 808–825. 10.1111/jomf.12121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zych I., Viejo C., Vila E., Farrington D. P. (2021). School bullying and dating violence in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(2), 397–412. 10.1177/1524838019854460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Canadian Adolescents’ Experiences of Dating Violence: Associations with Social Power Imbalances by Deinera Exner-Cortens, Elizabeth Baker, and Wendy Craigin Journal of Interpersonal Violence