Abstract

This longitudinal study explored changes in women's health after separation from an abusive partner by characterizing the trajectories of their mental health (depression and post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) and physical health (chronic pain) over a 4-year period. We examined how the severity of intimate partner violence (IPV) affected these trajectories, controlling for selected baseline factors using 5 waves of data collected from a community sample of 309 English-speaking, Canadian women. IPV severity was measured using the Index of Spouse Abuse where women were asked to consider the entire period of their partner relationship up to present at wave 1 and to rate their IPV experiences in the previous 12 months at waves 2-5. Mental health was measured using established self-report measures of depression (CESD) and PTSD (Davidson Trauma Scale), while chronic pain was measured using the Chronic Pain Grade Scale. Trajectories were estimated using MLM techniques with severity of IPV and selected co-variates (time since separation, age, financial strain) included. Our results show that women's health improved significantly over time, although significant levels of depression, PTSD symptoms and disabling chronic pain remained at the end of wave 5. Regardless of time since separation, more severe IPV was associated with higher levels of depression, PTSD, and disabling chronic pain, with IPV having a stronger effect on these health outcomes over time, suggesting cumulative effects of IPV on health. The results of this study contribute to quantifying the continuing mental and physical health burdens experienced by women after separation from an abusive partner. Increased attention to the long-term effects of violence on women's health beyond the crisis of leaving is critically needed to strengthen health and social services and better support women's recovery and healing.

Keywords: battered women, domestic violence, mental health and violence, PTSD, chronic pain

Health care providers are often the first, and sometimes the primary, professional contacts for women who have experienced abuse. Strengthening the capacity of health care providers and the systems in which they operate to deliver timely, trauma- and violence-informed services to women who have experienced violence is essential (Elliot et al., 2005; García-Moreno, Hegarty, et al., 2015). This approach begins with an awareness of the effects of interpersonal and systemic violence (both past and ongoing) on individuals, groups, and sometimes whole communities (Ponic et al., 2016; Wathen & Varcoe, 2022). Research examining health care responses to intimate partner violence (IPV) has identified pressing knowledge gaps and professional and systemic challenges that must be addressed to most effectively support women who have experienced IPV (García-Moreno, Zimmerman, et al., 2015; Tarzia et al., 2020). Among these gaps and challenges, a key priority is longitudinal research that advances policy makers’ and health care providers’ understanding of the long-term impacts of violence; quantifies the health burden on women who have experienced violence; and establishes causal links and more nuanced understanding about the complex relationships between violence and health outcomes over time (Bacchus et al., 2018; Temmerman, 2015).

Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence

IPV, defined as behavior by a partner or ex-partner that causes physical, sexual, or psychological harm (including physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse, and controlling behaviors), affects 1 in 3 women globally during their lifetimes (García-Moreno, Zimmerman, et al., 2015). There is substantial evidence, primarily derived from cross-sectional studies, that women who have experienced IPV have poorer mental and physical health than women in the general population (Campbell et al., 2002; Loxton, Dolja-Gore et al., 2017) and that IPV among women is associated with a wide range of health problems including Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), seizure disorders, arthritis, migraine, chronic pain, cardiovascular disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, functional gastro-intestinal disorder, suicidality, anxiety, and depression (Bacchus et al., 2018; Campbell et al., 2002; Dillon et al., 2013). Violence affects health through injury, health risk behaviors initiated or escalated to manage violence-related emotions or stress (Rheingold et al., 2004) and allostatic overload from the chronic stress of violence that causes physiological (e.g., inflammatory, neuroendocrine, immunologic) changes implicated in the development of chronic diseases including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and chronic pain (Keeshin et al., 2012; MacEwan & Gianaros, 2010).

Changes in Mental and Physical Health of Women who have Experienced Intimate Partner Violence

Women with histories of IPV seek health care at significantly higher rates than women who have not experienced IPV (Bonomi et al., 2009; Ford-Gilboe et al., 2015). Yet, studies of women’s recovery from IPV have largely examined mental health and focused on depression and PTSD (Bacchus et al., 2018; Devries et al., 2013), the two most common mental health problems affecting women with histories of IPV (Lagdon et al., 2014). Our review of literature identified 29 longitudinal studies published in the last 25 years that examined changes in women’s health as an outcome of IPV (See Supplementary Appendix A) and reveals some important insights related to women’s mental health: a) improvements in mental health generally depend on a reduction in, or cessation of, violence (e.g., Hedtke et al., 2008; Krause et al., 2008; La Flair et al., 2012), with the largest improvements seen shortly after the violence has ended (Anderson & Saunders, 2003); b) women may not fully recover their mental health (e.g., Cavanaugh et al., 2014; La Flair et al., 2012; Loxton, Dolja-Gore et al., 2017; Tsai et al., 2016); and c) the type (i.e., physical, sexual, psychological) and severity of abuse may impact a woman’s recovery (e.g., Blasco-Ros et al., 2010; Hill et al., 2009; Suvak et al., 2013).

Longitudinal research on physical health among women who have experienced IPV is scarce. A few studies have linked experiences of IPV to chronic physical health problems including type 2-diabetes (Mason et al., 2013), obesity (Garcia et al., 2014; Mason et al., 2017), and risk of cardiovascular disease (Scott-Storey et al., 2019; Stene et al., 2013). Even fewer studies have examined changes in women’s physical health as a consequence of IPV. Two studies (Gerber et al., 2008; Watkins et al., 2014) found that ongoing IPV is associated with poorer or worsening physical health symptoms over a short (1 year or less) period. Garcia et al. (2014) showed that any violence or traumatic event was associated with annual increases in weight and waist circumference over a 10 year period, but these effects were not examined specific to IPV. Given that changes in physical health have been largely overlooked in research, there is limited understanding of relative patterns of change in different types of mental and physical health outcomes over time, as well as the cumulative effects of living with multiple, complex health issues. Longitudinal research is needed to examine such changes in a wider range of physical health problems that have been associated with IPV in cross-sectional studies.

Among these, chronic (or persistent) pain, defined as pain that lasts or recurs for more than 3 months (Treede et al., 2015), is a common problem for women who have experienced IPV, often with substantial disabling effects on their quality of life, work, and social roles (Cerulli et al., 2012; Tiwari et al., 2013; Wuest et al., 2008). Although women experience chronic pain at higher rates than men, when they seek health care, they are more likely to have their concerns “dismissed” as mental health problems and less likely to receive effective treatment (Samulowitz et al., 2018; Walker et al., 2020). Given that most research on IPV and chronic pain is cross-sectional, the trajectory of chronic pain among women who have experienced IPV and how this may be affected by the severity of abuse or other features of women’s lives over time is poorly understood. In a recent systematic review, Walker et al. (2020) found greater burden associated with chronic pain among women with histories of IPV compared to those without such a history, and called for longitudinal research on the impacts of past and ongoing IPV on chronic pain in this population.

Women’s Health Trajectories in the Post-Separation Context

Separating from an abusive partner is a critical transition that can lead to both positive and negative changes in women’s lives. Women exercise strength and agency through the separation transition and often seek help for the abuse and the consequences of abuse, including health concerns (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2005; Rajah & Osborn, 2020). Nonetheless, their risk of re-victimization increases (Brownridge et al., 2008). Further, many live with other stressors that can persist for extended periods of time, including economic challenges, social isolation or problems accessing support or services (Crowne et al., 2011; Wuest et al., 2003).

In a recent systematic review of changes in women’s health after separation from an abusive partner, Patton et al. (2022) noted the primacy given to mental health in this research largely (84%) conducted in the United States (US) with women who were accessing services (32 of 36 studies). Their results identified a consistent reduction in depression (9 studies) and post-traumatic stress (5 studies) over time after separation, and emerging evidence of improvement in general physical symptoms (4 studies); no studies focused on chronic pain. Importantly, ongoing IPV was the most consistent predictor of changes in women’s health, while relationship status (involved or apart) had no effects. These results call into question the tendency to conflate “separation” from an abusive partner with “end of abuse,” and the focus on measuring whether the relationship has “ended” rather than the extent to which abuse is ongoing. Measurement of IPV has been plagued by challenges such as the use of single “yes/no” items or brief unvalidated self-report scales, rather than standardized measures better suited to capturing the dimensions and complexity of IPV (Ponic et al., 2016). This practice potentially results in under-reporting of abuse (Loxton, Townsend, et al., 2017) and constrains exploration of the association between severity of IPV and changes in health over time.

The context of women’s lives is an important but understudied factor in their health trajectories during and after separation. In a cross-sectional analysis of women who had separated from an abusive partner, women’s personal, social, and economic resources mediated the relationship between severity of IPV and women’s mental and physical health, such that more severe abuse eroded women’s resources, with negative effects on their health (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2009). In Patton et al.’s (2022) review, social support consistently predicted improvements in women’s health trajectories (5 studies) and access to economic resources predicted improvement in depression (2 studies); results were inconclusive for post-traumatic stress (2 studies) and change was not examined in relation to physical health. From an equity perspective, studies that unpack the complex relationships among IPV, health and varied social and economic conditions could lead to more nuanced understanding of women’s continued risks and inform more tailored and appropriate interventions.

Current Study

In summary, an emerging body of longitudinal research suggests that depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms improve among women in the early period after separation from an abusive partner, with some limited evidence of improvement in general physical symptoms, primarily among women in the US who had recently separated and were accessing services. There is a need to examine changes in mental and physical health concurrently in order to understand how these patterns are similar or different, and to examine a wider range of physical health problems internationally and with community samples. While ongoing IPV, social support, and access to resources have been found to predict women’s health trajectories in a few studies, research is needed to more fully understand the concurrent effects of the severity of past and ongoing IPV and other life stressors on women’s health trajectories post-separation, and to quantify women’s long-term risks of sustained poor health. This understanding is essential for developing strategies and interventions that address the unique needs of women with histories of violence as they navigate the often lengthy transition of separating from an abusive partner.

To begin addressing these gaps, this analysis was undertaken to: a) describe trajectories of mental health (depression, post-traumatic stress) and physical health (chronic pain) over a 4-year period in a community sample of Canadian women who, at baseline, had recently separated from an abusive partner, and b) examine the effects of severity of past and ongoing IPV on these trajectories, controlling for key baseline co-variates (i.e., age, time since separation, financial strain). Depression, post-traumatic stress, and chronic pain are among the most common and debilitating health consequences of IPV for women, and longitudinal changes in chronic pain have not been previously examined in the post-separation context.

Consistent with the small body of existing literature, we hypothesized a reduction in symptoms of depression, post-traumatic stress, and chronic pain over a 4 year period of time, but did not specify a priori the rate of change across time. By concurrently examining these three health trajectories, we hope to better understand relative patterns of changes across different health outcomes, and to quantify any ongoing health burden experienced by women in the transition of separation. Our hypothesis that the severity of IPV (past and ongoing) would predict health outcomes over time is based on an understanding that IPV is a common experience in the life course of women with cumulative effects on health, and that separation from an abusive partner does not equate with cessation of violence. Consistent with Patton et al.’s (2022) review, accounting for the severity of past and ongoing IPV is particularly salient in predicting changes in women’s health post-separation.

Methods

This analysis used data from the Women’s Health Effects Study (WHES) (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2009), a prospective, longitudinal study of women who, at baseline, had been separated from an abusive male partner (i.e., “index partner”) for up to 3 years. Data were collected in 5 waves at approximately 12-month intervals between 2004 and 2009.

Settings and Participants

A community sample of 309, English-speaking women, aged 18–65 years, was recruited from 3 Canadian provinces (British Columbia, Ontario, New Brunswick) using advertisements placed in community settings, service agencies, and print media (national and local). Advertisements invited adult women who had separated from an abusive partner in the prior 3 years and were interested in taking part in a women’s health study to contact the research team using a toll free number. All women in this community sample self-referred to the study. A research assistant followed-up with each women by telephone or email to explain the study and screen them for eligibility using a modified, 4-item Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS) (McFarlane et al., 1992) to confirm exposure to IPV. A positive response to 1 or more of the 4 questions on the AAS was used as an indicator of IPV in the relationship with the partner from whom the woman had recently separated (i.e., the index partner). Of the 353 women who met the inclusion criteria, 309 (87.5%) completed wave 1 (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2009). Given high mobility of women after separation from an abusive partner, a standardized retention protocol was used to maintain safe contact with women. Over a 4 year period, 59 women were lost to follow-up, resulting in sample retention rate of 81% (250 of 309) at Wave 5.

Procedures

At each wave, women completed a structured interview conducted by a Registered Nurse in a private setting. A combination of standardized self-report measures, survey questions, and bio-physical tests were used to measure abuse; personal, social, and economic resources; mental and physical health; service use; and demographics. Data were entered into a laptop computer. Ethics approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Board at each study site prior to recruitment. Written consent was obtained from each woman prior to data collection and re-affirmed before each interview. A detailed safety protocol, including guidelines for debriefing women, was used to guide all interactions between women and the research team (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2015). Additional details of the methodology for the full study are described elsewhere (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2009).

Measurement

Baseline Predictors of Health

At wave 1, we measured 3 variables that could influence women’s level of health at the beginning of their trajectory (i.e., intercept) and/or the rate of change (i.e., slope) in health: time since separation, age, and financial strain. These predictors were selected because of their theoretical importance, while also limiting the number of variables in the analysis in order to maintain statistical power. Age in years and time since separation (in months) were each measured using women’s self-reports. Financial strain was measured using a global question from the Financial Strain Index (Ali & Avison, 1997), a self-report scale developed to quantify difficulty meeting financial obligations across 14 different domains. Women were asked to respond to the question, “Overall, how difficult is it to live on your current income right now?” on a 5-point scale with options that ranged from “not at all difficult” to “extremely difficult or impossible.”

Intimate Partner Violence Severity

At each wave, IPV severity was measured using the 30-item Index of Spouse Abuse (ISA) (Hudson & McIntosh, 1981) where women reported the frequency of abusive acts they experienced in their partner relationships on a scale ranging from never (0) to very frequently (4). Given our interest in measuring the severity of ongoing abuse over time, at baseline, women were asked to report on the abuse they experienced by considering the entire relationship with the ex-partner from whom they had separated (i.e., index partner) up to present. Since we expected that some women would enter into new partner relationships and others would return to the former partner over the 4 years of the study, in waves 2–5, they were asked to provide ratings for abusive acts by any partner in the previous 12 months. This allowed for the collection of data about severity of IPV over the full course of the study, since waves were spaced at 12 months intervals, and regardless of source (index partner or new partner(s). Subscale scores (physical and non-physical abuse) were computed using standard scoring by weighting individual items for severity and by then summing these scores (possible range 0–100). For each wave, Severity of IPV was computed as the mean of physical and non-physical abuse scores. The ISA has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity across samples of women from varied contexts (Coker et al., 2001).

Mental Health

Mental health was measured using established self-report measures of depression and PTSD. The total score on the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale (Radloff, 1977) was used to measure depressive symptomology. Women’s ratings of symptom frequency in the past week on a 4-point scale, from rarely or none of the time (0) to most of the time (3), were summed to produce total scores (range 0–60). Scores ≥22 are consistent with significant clinical depression, while lower scores (≥16 and <22) are consistent with mild to moderate symptoms. Internal consistency of the CES-D in our sample ranged from .761 to .785 across waves.

The total score on the 17-item Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) (Davidson, 1996) was used to assess PTSD symptoms. Validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability of the DTS has been demonstrated in a variety of trauma populations (Davidson et al., 2002; Mason et al., 2013). Women rated the past week symptoms consistent with a DSM-IV criteria for PTSD using separate response options for frequency and severity that ranged from 0 (not at all/not at all distressing) to 4 (every day/distressing every day). Separate frequency and severity scores were computed by summing responses to applicable items and total scores computed by summing these scores (range 0–136). Internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) was acceptable across the waves (.894–.917). Scores ≥40, along with the presence of a minimum number of symptoms in each of 3 clusters, can be used to reliably classify participants as having symptoms consistent with a DSM-IV diagnosis of PTSD (Davidson, 1996).

Physical Health

One physical health outcome, chronic pain, was measured using the 3-item pain disability subscale from Von Korff’s 7-item Chronic Pain Scale (Von Korff et al., 1992). Participants rated the extent to which pain interfered with their lives in 3 areas (daily activities; change in ability to take part in recreational, social, and family activities; and change in ability to work, including housework) in the previous 6 months on scale ranging from 0 (no interference) to 10 (worst interference). The Pain Disability score (0–100) was derived by multiplying the mean of these 3 items by 10 (Cronbach’s alpha .931 to .946 across 5 waves). A categorical pain grade (from 0 to 4) can also be computed, where a grade of 3 or 4 denotes highly disabling chronic pain (Von Korff et al., 1992). Use of the continuous disability score in our analysis enabled a consistent analytic strategy and better visualization of patterns of change across them.

Statistical Analyses

Multilevel modeling (MLM) was used to estimate the trajectory of the health variables over time. Because baseline time since separation varied (from 3 months to 3 years), time was centered so that the intercept term reflects the average level of the outcome across time. The initial unconditional model (model 1) predicted the outcome from time and included linear and quadratic slopes. Next, IPV Severity and the interaction between time and IPV Severity were added as time-varying covariates along with baseline covariates of financial strain, time since separation and age as predictors of the overall level of each health outcome (model 2).

A small number of women (15 of 309) were missing values on one baseline co-variate. Twelve women were missing a value for time since separation, while 3 women were missing values for financial strain. All women were retained for the initial trajectory analysis as MLM does not require that participants have complete data at each time point. When the baseline variables were added to the model, those with missing data were dropped from the analyses. They were not dropped apriori. The sample was deemed adequate for our planned analysis (Byrne & Crombie, 2003).

Results

Of the 309 women who completed baseline, 286 (92.6%) completed wave 2, 270 (87.4%), completed wave 3, 255 (82.5%) completed wave 4, and 250 (80.9%) completed wave 5. At wave 5, those who were lost to follow-up were more likely (at baseline) to identify as Indigenous1 (i.e., 10 of 23 women lost to follow up) and/or to have high disability chronic pain (i.e., 23 of 103 women lost to follow up).

Description of the Sample

On average, at baseline, women were 39.4 years of age (SD = 9·87) with a mean income of $26,958 (SD = 27,487.48). The majority (66.3%) reported experiences of abuse when they were children, 40% reported being sexually assaulted as adults (not including the relationships with their respective ex-partners), and 34% had been in more than one relationship with an abusive partner. Although women reported that they had been separated from their abusive partner for an average of 20 months (range 2 months–3 years) at baseline, 40% reported current abuse from their ex-partner at that time (based on a single question). Four years later (wave 5), the majority (54.8%, n = 137) reported no contact with the index partner in the previous year, 44.0% (n = 110) reported some contact (but were not residing with this partner), while 3 women (1.2% of the sample) were living with this partner. At wave 5, the women had been separated for up to 7 years; most (62%, n = 156) reported that they had been in a partner relationship(s) at some point in the previous year.

As reported elsewhere (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2009, 2015), the sample was similar to women in the Canadian population with respect to years of education (M = 13.4 years, SD = 2.6); and percentage of rural dwellers (23%) and racialized women (16.8%). However, women in our sample faced more economic challenges (i.e., higher rates of unemployment, social assistance, disability benefits, and lower incomes) than those in the Canadian population. The majority of women had contact with health professionals in the month prior to entering the study. While this contact underscores opportunities for health professionals to assist women with histories of IPV, 65% of women reported experiencing difficulties accessing needed services. Consistent with increased risk of IPV for Indigenous women (Brownridge, 2008), Indigenous women participated at twice the rate found in the Canadian population (i.e., 7.4% in sample vs. 4% in population).

Health Trajectories and Predictors of Change

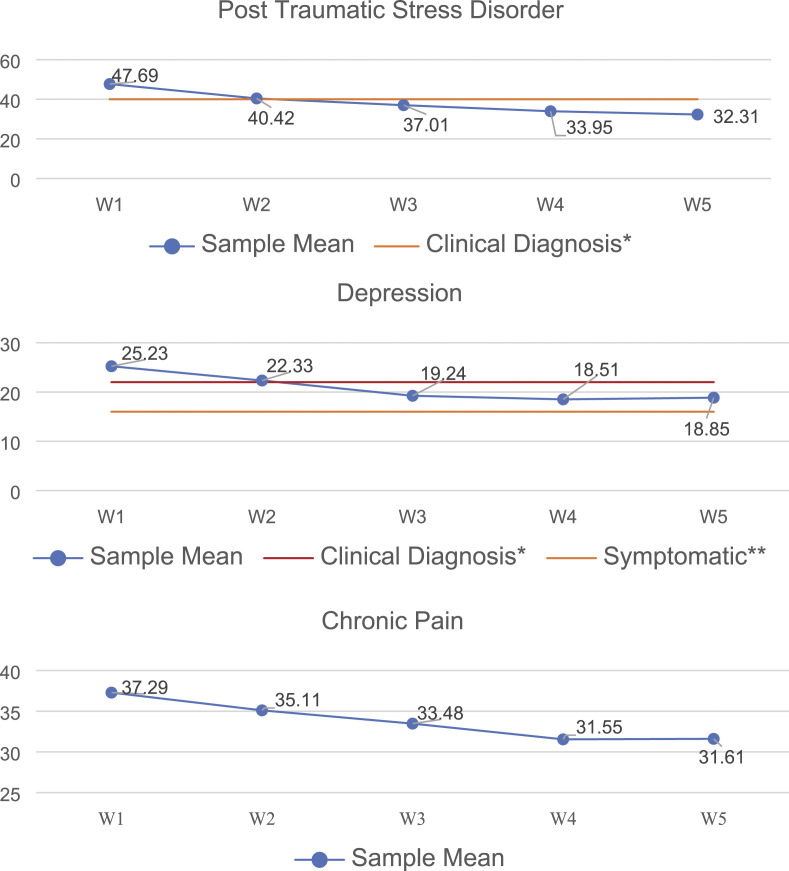

The trajectories for PTSD, depression and chronic pain over 4 years are summarized in Table 1, along with predictors of the overall level and rate of change for each outcome. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of each trajectory. For depression and PTSD, clinical thresholds are shown to illustrate the level of health of the sample relative to clinically significant symptoms; clinical cut scores are not available for disabling chronic pain and are, therefore, not shown.

Table 1.

Parameter Values for Trajectories of Health and Predictors (N = 309).

| Depression | PTSD | Chronic Pain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditional trajectory over timea | |||

| Intercept | 19.82 p < .001 | 32.31 p < .001 | 33.83 p < .001 |

| Linear | −1.56 p < .001 | −3.46 p < .001 | −1.14 p = .008 |

| Quadratic | 0.58 p < .001 | 0.85 p = .016 | 0.28 p = .413 |

| Impact of IPV severity over timeb | |||

| IPV | 0.15 p < .001 | 0.37 p < .001 | 0.19 p < .001 |

| IPV by time | 0.05 p < .001 | 0.09 p = .001 | 0.05 p = .032 |

| Time since separation | −0.09 p = .088 | −0.04 p = .760 | 0.05 p = .743 |

| Age | −0.04 p = .486 | 0.16 p = .238 | 0.19 p = .179 |

| Financial strain | 0.15 p < .001 | 0.37 p < .001 | 0.20 p < .001 |

aModel included time and time squared.

bModel included time and time squared (if significant in the unconditional model), IPV and IPV by time, and baseline time since separation, age, and financial strain.

Figure 1.

Mean scores for post-traumatic stress, depression and chronic pain over 4 years *Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) score >40 is consistent with clinically significant PTSD symptoms *CESD score >22 is consistent with diagnosis of depression **CESD score >16 and <22 is the threshold for mild to moderate symptoms of depression.

Depression declined over time (b = −1.56, p < .001) but the rate of decline slowed over time (b = 0.58, p < .001). The average level of symptoms at Wave 5 (18.85) was below the threshold of 22 used to indicate consistency with a clinical diagnosis of depression but above the threshold for depressive symptoms or dysthymia (i.e., a score ≥16 and <22). Like depression, PTSD also declined over time (b = −3.46, p < .001) and the rate of decline also decreased with time (b = 0.85, p = .016). By the end of the trajectory (Wave 5), the average level of PTSD symptoms (32.31) was slightly below the threshold for clinically significant symptoms (i.e. a cut score of 40). While Chronic Pain Disability declined over time (b = −1.14, p = .008), unlike mental health outcomes, the rate of change did not vary across time (b = 0.28, p = .413).

In spite of improvements in all 3 health outcomes (i.e., depression, PTSD, chronic pain disability) over time, at the end of each trajectory (Wave 5), the health of women in the sample was substantially worse than that of women in the general population, based on comparisons with existing data (Table 2). Specifically, we estimate the rates of clinically significant depression, PTSD symptoms and chronic pain in the sample at wave 5 to be 3.6 to 14.6 times higher than among adult women in the Canadian population.

Table 2.

Comparison of Rates of Health Problems in the Sample versus Canadian Women.

| Health Outcome | Rate in Sample | Rate for Canadian Women, % | Rate of Increased Risk in Sample at Wave 5 Compared to Rate for Canadian Women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 N = 309 | Wave 5 N = 250 | |||

| Depression | ||||

| Clinical depression | 56.5%a | 51.1%a | 5.9e | 8.7 |

| Depressive symptoms | 69%b | 60.2%b | 9.6f | 6.3 |

| PTSD | 54.9%c | 46.8%c | 3.2g | 16.6 |

| Disabling chronic pain | 33.3%d | 30.4%d | 11.2h | 2.7 |

aBased on CESD scores ≥22, a proxy for clinical depression.

bBased on CESD score ≥16, reflecting at least mild depressive symptoms.

cBased on Davidson Trauma Scale score ≥40, the threshold for clinically significant PTSD Symptoms.

dBased on Pain Grade III or IV on the Chronic Pain Grade Scale, reflecting percent of participants with pain highly disabling pain that significantly interfered with activities of daily living in previous 6 months (Von Korff et al., 1992).

ePrevalence of depression among Canadian women 15 years and older, using data from the Canadian Community Health Survey 2012 (Pearson, Janz & Ali, 2013).

fPercentage of Canadian women age 12+ reporting a mood disorder. Data from Statistics Canada, Health Indicators 2014 Table 13-10-0451-01. Retrieved from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310045101&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.1&pickMembers%5B1%5D=2.1&pickMembers%5B2%5D=3.3&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2010&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2014&referencePeriods=20100101%2C20140101

gEstimate calculated based on current (1 month) prevalence of PTSD of 2.4% among Canadian adults (Van Ameringen, Mancini, Patterson, & Boyle, 2008) and evidence that women’s lifetime PTSD is twice that of men (Katzman et al., 2014), assuming equal percentage of men and women in the Canadian population.

hPercentage of Canadian women 15–64 years of age reporting a pain-related disability that limited activity drawn from the 2012 Canadian Disability Study (Burlock, 2017).

Effects of Intimate Partner Violence Severity and Baseline Covariates on Women’s Health Trajectories

Baseline IPV severity was significantly and positively associated with overall level of symptoms of depression (b = 0.15, p < .001), PTSD (b = 0.37, p < .001), and chronic pain (b = 0.19, p < .001), controlling for age, time since separation, and financial strain. The severity of IPV by time interaction was significant and positive for depression (b = 0.05, p < .001), PTSD (b = 0.09, p = .001), and chronic pain (b = 0.05, p = .032). In other words, the impact of IPV on these outcomes became significantly stronger over time after controlling for baseline age, time since separation, and financial strain. For example, the association of IPV severity and depression was r = 0.28 at wave 1, r = 0.31 wave 2, r = 0.34 wave 3, r = 0.36 wave 4, and r = 0.37 at wave 5.

Total scores for Severity of IPV declined over time with the highest scores (M = 56.9, SD 19.94) at baseline when women reported on the abuse they experienced from the ex-partner over the full period of the relationship. IPV Severity scores in waves 2–5 (based on abuse in the previous 12 months from any partner) were lower and declined over time (W2 M = 15.45, SD = 16.18; W3 M = 11.24, SD = 15.55; W4 M = 9.69, SD = 14.50; W5 M = 9.81, SD = 13.62).

Of the baseline co-variates, neither time since separation nor age was associated with the overall level of any health outcome. In contrast, financial strain was significantly and positively associated with all 3 health outcomes, such that greater baseline financial strain independently predicted greater levels of depression (b = 0.15, p < .001), PTSD (b = 0.37; p < .001) and chronic pain (b = 0.20, p < .001), controlling for the effects of other variables in the model.

Discussion

We explored changes in women’s health after separation from an abusive partner by characterizing the trajectories of depression, PTSD, and chronic pain over a 4-year period and examining how the severity of IPV from the abusive partner (throughout the relationship) and then any partner (over a 4 year post-separation period) affected these trajectories, controlling for selected baseline factors. Women’s health improved significantly over time, with depression and PTSD both improving more in the first year and then leveling off, and chronic pain improving at a more gradual and steady rate. However, at Wave 5, substantial levels of mental health symptoms and disabling chronic pain remained with rates estimated to be 3.6 to 14.6 times higher in the sample than in women in the general population. Baseline length of time since separation did not predict women’s health over time. However, as hypothesized, severity of past and ongoing IPV significantly predicted changes in all 3 health outcomes over time, with the strength of these associations increasing over time. Collectively, this study contributes unique understanding that underscores the enduring costs of IPV for both women’s mental and physical health post-separation in a community sample of Canadian women, and draws attention to the role of severity of continuing IPV in shaping women’s health during this critical transition. These results extend current knowledge about women’s health in the context of IPV by emphasizing that although recovery may begin, neither separation, or time, heal all wounds.

Changes in Women’s Mental and Physical Health

As hypothesized and consistent with the literature, both women’s mental health (Beeble et al., 2009; Blasco-Ros et al., 2010; Mertin & Mohr, 2001) and physical health (Sanchez-Lorente et al., 2012; Watkins et al., 2014) improved over time. Notably, this study is the first to specifically document changes in chronic pain over time among women who have experienced IPV during the relationship and/or after separation. Our findings of substantial continuing symptoms of depression, PTSD, and disabling chronic pain are also consistent with research documenting chronic health problems among women with histories of IPV (Garcia et al., 2014; Loxton, Dolja-Gore, et al., 2017; Tutty et al., 2020), a finding that has been explained by the premise that allostatic overload from trauma and violence leads to dysregulation of the body’s stress-response system, causing neuroendocrine, metabolic, haemostatic, immunologic, and inflammatory changes (McEwen & Gianaros, 2010). These conditions may be difficult to change given that IPV has been shown to contribute to telomere shortening, an irreversible marker for cellular aging (Humphreys et al., 2012). In the context of IPV, chronic health problems have also been associated with physical injuries (e.g., fractures, or tissue or organ damage from hypoxia associated with incomplete strangulation) that can lead to chronic pain or exacerbate symptoms of depression or PTSD (Campbell et al., 2019). Given these common underlying mechanisms, evidence of substantial co-morbidity among depression, PTSD, and chronic pain is also not surprising.

Our results that mental health (depression, PTSD) improved significantly and immediately and then tapered off, while the trajectory of change in chronic pain was more constant and gradual is noteworthy. In previous cross-sectional analysis of Wave 1 data, both depression and PTSD had direct effects on chronic pain severity; abuse-related injury mediated the effects of assaultive IPV on chronic pain but neither depression nor PTSD mediated this relationship (Wuest et al., 2010). Our current results suggest that early improvement in mental health may contribute to a decline in chronic pain post-separation. Further research is needed to understand whether and how injury contributes to that trajectory. Some of the early and more dramatic improvement in mental health could be attributed to a reduction in stress as women gain relief and freedom from living under constant threat, a finding that has been supported in the longitudinal research on divorce (Blekesaune, 2008; Leopold, 2018). However, while divorce research has consistently shown that women’s mental health gradually returns to pre-marital crisis levels within 2–3 years, our results show persistent mental health concerns up to 7 years post-separation. These residual mental health problems may be directly attributed to the traumatic effects of IPV and/or chronic stress that is often a consequence of IPV. In contrast, the more gradual and modest pattern of improvement observed in chronic pain is consistent with current evidence documenting the intractability of chronic pain and the challenge this creates for effective treatment (Canadian Pain Task Force, 2019), and well as gender-biases in the treatment of chronic pain (Walker et al., 2020).

Our results provide specific evidence about the ongoing health concerns of women who have separated from an abusive partner—a population that faces multiple ongoing challenges (Wuest et al., 2003) but tends to be overlooked by structures and policies that orient services to crises and fail to consider long-term health consequences of violence. There is considerable evidence that women with histories of IPV access health care at higher rates than in the population (Bonomi et al., 2009; Ford-Gilboe et al., 2015), but that access barriers and poor fit of services with women’s needs persist (Stam et al., 2015). Although we did not examine whether health service use and quality predict changes in women’s trajectories of health in the post-separation period, this is an important area for future research. Existing clinical guidance advocates the adoption of practices that emphasize women’s safety and respect for self-determination, while also providing excellent care to address women physical and mental health problems (World Health Organization, 2013). Our results suggests that helping women understand the effects of previous and continuing abuse on their current physical and mental health is important (Machtinger et al., 2019). Given that women’s mental and physical health are linked, Wright et al. (2018) suggest that depression screening of women with histories of IPV may be a preventive physical health intervention. Comprehensive interventions that promote women’s mental and physical health, while also addressing safety and other issues that affect their health, are needed with some interventions showing promise (Varcoe et al., 2019; Wuest et al., 2015). Given the intractability of chronic pain, the inadequacies of the system of care addressing pain, and evidence of the association between IPV and chronic pain, attention to pain must be a cornerstone of interventions for women with histories of IPV.

Influence of the Severity of Intimate Partner Violence on Health Trajectories

Our findings suggest that the severity of abuse to which a woman is exposed predicts her mental and physical health and long-term recovery regardless of the length of time since separating from her abusive partner, and source of abuse (former partner or new partners). These results are consistent with an emerging body of longitudinal research on women’s mental health after separation from an abusive partner, including 2 studies on physical health (Patton et al., 2022). More severe IPV was associated with poorer mental health (greater symptoms of depression and PTSD), and more severe chronic pain, with IPV having a stronger impact on these health outcomes over time. These findings suggest that IPV severity over time (and not simply the occurrence of IPV at one point) has important cumulative effects on patterns of women’s health (i.e., depression, PTSD and chronic pain). Studies of IPV and health have been critiqued for reliance on measuring the frequency or occurrence of incidents of abuse at a single point in time and neglecting the recurrent nature of IPV (Scott-Storey, 2011). Our results make a significant contribution to the longitudinal study of health consequences of cumulative IPV by using a measure of severity of abuse and including a temporal component that captured recurrent IPV including after leaving an abusive partner. Given that separation does not equate to the end of abuse, we argue that research on women’s health post-separation should routinely account for the impacts of continuing IPV.

Not included in this analysis is how other lifetime experiences of violence such as child maltreatment, sexual assault and workplace violence might influence health outcomes over time. It is possible that the effects of IPV on health trajectories might have been smaller if other traumas or chronic stressors had been considered as predictors in the analysis. An earlier analysis of baseline data from this sample identified a relationship between patterns of cumulative lifetime abuse including IPV, child abuse and adult sexual assault (using latent class analysis) and health and economic outcomes among women an average or 20 months post-separation (Davies et al., 2015). In another study, Cavanaugh et al. (2014) found that, after controlling for ongoing trauma exposure, female health care workers who reported 1, 2, or 3 or more kinds of violence had incrementally greater odds 6 months later of screening positively for comorbid PTSD and depression than counterparts with no lifetime victimization. Our results suggest that the cumulative effects of past and continuing IPV affect women’s health up to 7 years beyond the crisis of separation. These results underscore the need for policies and services to acknowledge women’s ongoing risk of IPV after separation and the persistent effects of IPV on their health and well-being as well as the importance of prevention, supporting women to recognize abuse early, and effective early support.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

As a first step in examining longitudinal changes in women’s health in the post-separation period, this study focused primarily on describing trajectories of change in 3 health outcomes that are both common and distressing and examining the impact of a limited number of predictors of change. A more complete understanding about how women’s shifting personal, social, and economic resources affect trajectories of health for a wide range of distressing health outcomes remains an important gap in knowledge. The level of women’s financial strain at baseline significantly influenced their health outcomes, but our analysis did not test whether or how changes in financial strain (or economic resources) affected their health over time. Given that financial resources are a determinant of health, and evidence that economic challenges are often a long-term challenge for women with histories of violence (Crowne et al., 2011), future research should investigate the effects of variable and changing resources on women’s health over time in the post-separation period.

Given that women’s health is complex and determined by many factors, consideration should also be given to examining the effects of other features of women’s lives that may impact changes in their health, including their access to social support; access to and quality of health care; and other systemic barriers (such as experiences of stigma or discrimination) that might account for differences in health outcomes or rates of change. Studies of this type are critical in illuminating multiple and intersecting consequences of IPV in the context of structural or systemic violence, including challenges accessing high quality services. Given the substantial number of women in our sample who experienced multiple forms of historical abuse, future research that considers the impact of IPV and cumulative lifetime violence on women’s health will be important.

We aimed to be inclusive in our approach and to reduce structural barriers to participation. For example, our procedures prioritized physical and emotional safety for women, including through training of interviewers, and we offered flexible options for interview locations and financial assistance for childcare and/or transportation. We succeeded in recruiting a relatively diverse sample that varied in age, education, and socio-economic status and that reflected the Canadian population in terms of the relatively small relatively small representation of rural dwellers and racialized women. Indigenous women were over-represented in the sample, reflecting their greater risk of IPV (Pedersen et al., 2013). The high retention (81% over 4 years), particularly given that participants were experiencing multiple life changes, underscores the importance of well-developed safety and retention protocols in longitudinal studies of women who have experienced violence. The use of MLM also enabled retention of data from all women in the analysis.

In spite of these strengths, there may have been unacknowledged biases within study processes that affected women’s participation and contributed to greater drop out over time. The number of Indigenous women who enrolled was fairly small (n = 23) and they were also more likely to be lost to follow up over time (10 women by W5), although the magnitude of this issue may be subject to error give the small group size. Drop out was largely due to difficulty maintaining contact with women, a challenge associated with residential moves post-separation, particularly among lower income women (Ponic et al., 2011). Given the effects of colonization, Indigenous women are more like to be affected by poverty and housing instability (Bingham et al., 2019); moving back and forth between reserve and off-reserve housing is common. Finally, the notion of “leaving” an abusive partner is contested in Indigenous contexts since this suggests breaking important ties with one’s community and culture (Smye et al., 2020). Thus, some Indigenous women may have found the post-separation focus less relevant.

The self-report health measures used in this study are not a replacement for clinical interviews, but offered a reasonable proxy for both mental and physical health outcomes. To measure PTSD, we used the DTS, a reliable but older measure that is based on DSM-IV criteria and does not account for the addition of alteration in cognition and mood added in DSM-V. However, our results are consistent with existing longitudinal research based on use of a continuous score; we used cut scores solely to compare levels of probable PTSD in our sample with women in the general Canadian population using estimates that pre-dated DSM-V. Further, our use of a standardized self-report measure to capture severity of IPV is an improvement over the measurement practices adopted in many of the longitudinal studies reviewed. The measurement of IPV is a complex issue with many continuing debates. Future research must keep pace with new developments in this field in order to produce the highest quality evidence about the health consequences of IPV.

Conclusion

Contrary to the assumption that time heals all wounds, the results of this study contribute to quantifying the continuing mental and physical health burdens experienced by women after separation from an abusive partner. Increased attention to the long-term effects of continuing violence on women’s health beyond the crisis of leaving is critically needed to strengthen health and social services and better support women’s recovery and healing.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-jiv-10.1177_08862605221090595 for Trajectories of Depression, Post-Traumatic Stress, and Chronic Pain Among Women Who Have Separated From an Abusive Partner: A Longitudinal Analysis by Marilyn Ford-Gilboe, Colleen Varcoe, Judith Wuest, Jacquelyn Campbell, Michelle Pajot, Lisa Heslop, and Nancy Perrin in Journal of Interpersonal Violence

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the women who generously gave of their time to participate in the Women’s Health Effects Study and to the skill and expertise of our Research Manager, Joanne Hammerton, and research coordinators and assistants. We acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Barat Wolfe to an early version of the literature review included in this paper.

Author Biographies

Marilyn Ford-Gilboe, RN, PhD, FAAN, FCAHS, FCAN, is a Distinguished University Professor and Women’s Health Research Chair in Rural Health, Arthur Labatt Family School of Nursing, University of Western Ontario, Canada. Her research focusses on the health, social and economic impacts of violence and inequity, and the development of community-based interventions to improve women’s health, safety and quality of life across diverse contexts.

Colleen Varcoe, RN, PhD, FCAHS, FCAN is a Professor in the School of Nursing, University of British Columbia. Her research on violence and inequity emphasizes the relationship between structural and interpersonal violence, particularly as it affects Indigenous populations, and aims to promote equitable policy and practices through intervention research.

Judith Wuest, PhD, RN (retired), is a Professor Emerita, Faculty of Nursing, University of New Brunswick.

Jacquelyn Campbell, PhD, RN, FAAN, is the Anna D. Wolf Endowed Professor, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. Her decades of research in the arena of partner violence and chronic trauma and physical and mental health outcomes has made a significant impact on policy.

Michelle Pajot, PhD, was formerly a Research Associate, Arthur Labatt Family School of Nursing and is now Principal at Goss Gilroy Inc (GGI).

Lisa Heslop, MA, PhD(c), is a Research Associate in the Arthur Labatt Family School of Nursing and a PhD candidate at the University of Toronto.

Nancy Perrin, PhD, Professor and Lead, Statistics Core, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, is an expert in the application of multivariate statistical techniques to health outcomes with an emphasis on violence against women both domestically and internationally.

Note

“Indigenous” refers to the original inhabitants of a given geographic area, and is the preferred term to be used globally. In what is now called Canada, Indigenous people (previously referred to as “Aboriginal”) include three groups recognized by the Canadian Constitution: First Nations, which encompasses “Status” and “non-Status Indians” as defined by the Indian Act (Indian Act, R.S.C., 1985, c.1-5, retrieved on April 13, 2022 at https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-5/fulltext.html), Métis, who are people of mixed Indigenous and European ancestry descended from historic Métis Nation Ancestry, and Inuit, who are the Indigenous peoples of the Artic regions.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) New Emerging Team Grant #106054 and Institute of Gender and Health Operating Grant #15156 (Marilyn Ford-Gilboe, PI).

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Marilyn Ford-Gilboe https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4328-8748

Colleen Varcoe https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9090-2793

Judith Wuest https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3968-445X

Lisa Heslop https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1182-6719

Nancy Perrin https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2025-6543

References

- Ali J., Avison W. R. (1997). Employment transitions and psychological distress: the contrasting experiences of single and married mothers. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(4), 345–362. 10.2307/2955430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D., Saunders D. (2003). Leaving An Abusive Partner: An Empirical Review of Predictors, the Process of Leaving, and Psychological Well-Being. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 4(2), 163–191. 10.1177/1524838002250769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchus L. J., Ranganathan M., Watts C., Devries K. (2018). Recent intimate partner violence against women and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ Open, 8(7), e019995. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeble M. L., Bybee D., Sullivan C., Adams A. E. (2009). Main, mediating, and moderating effects of social support on the well-being of survivors of intimate partner violence across 2 years. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(4), 718–729. 10.1037/a0016140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham B., Moniruzzaman A., Patterson M., Sareen J., Distasio J., O'Neil J., Somers J. M. (2019). Gender differences among Indigenous Canadians experiencing homelessness and mental illness. BMC Psychology, 7(1), 57. 10.1186/s40359-019-0331-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco-Ros C., Sánchez-Lorente S., Martinez M. (2010). Recovery from depressive symptoms, state anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder in women exposed to physical and psychological, but not to psychological intimate partner violence alone: a longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry, 10(98). 10.1186/1471-244X-10-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blekesaune M. (2008). Partnership transition and mental distress: Investigating temporal order. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(4), 879–890. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00533.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi A., Anderson M., Rivara F. P., Thompson R. S. (2009). Health care utilization and costs associated with physical and nonphysical-only intimate partner violence. Health Services Research, 44(3), 1052–1067. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00955.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownridge D. A. (2008). Understanding the elevated risk of partner violence against aboriginal women: a comparison of two nationally representative surveys of Canada. Journal of Family Violence, 23(5), 353–367. 10.1007/s10896-008-9160-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brownridge D. A., Chan K. L., Hiebert-Murphy D., Ristock J., Tiwari A., Leung W. C., Santos S. C. (2008). The elevated risk for non-lethal post-separation violence in Canada. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(1), 117–135. 10.1177/0886260507307914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlock A. (2017). Women in Canada: A Gender-based Statistical Report. Women with Disabilities. Statistics Canada. https://eapon.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Women-in-canada-Women-with-Disabilities-GenderBasedStatsReport.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B. M., Crombie G. (2003). Modeling and testing change: An introduction to the latent growth curve model. Understanding Statistics, 2(3), 177–203. 10.1207/s15328031us0203_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell F., Hudspith M., Anderson M., Choiniere M., El-Gabalawy H., Laliberte J., Wilhelm L. (2019). Chronic pain in Canada. Laying a Foundation for Action. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J., Jones A. S., Dienemann J., Kub J., Schollenberger J., O’Campo P., Wynne C. (2002). Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Archives of Internal Medicine, 162(10), 1157–1163. 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Pain Task Force (2019). Chronic pain in Canada: Laying a foundation for action. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/corporate/about-health-canada/public-engagement/external-advisory-bodies/canadian-pain-task-force/report-2019/canadian-pain-task-force-June-2019-report-en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh C., Campbell J., Messing J. T. (2014). A longitudinal study of the impact of cumulative violence victimization on comorbid posttraumatic stress and depression among female nurses and nursing personnel. Workplace Health and Safety, 62(6). 10.3928/21650799-20140514-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerulli C., Poleshuck E., Raimondi C., Veale S., Chin N. (2012). What fresh hell is this?” victims of intimate partner violence describe their experiences of abuse, pain, and depression. Journal of Family Violence, 27(8), 773–781. 10.1007/s10896-012-9469-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker A. L., Pope B. O., Smith P. H., Sanderson M., Hussey J. R. (2001). Assessment of clinical partner violence screening tools. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association, 56(1), 19–23. 11202067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowne S. S., Juon H.S., Ensminger M., Burrell L., McFarlane E., Duggan A. (2011). Concurrent and long-term impact of intimate partner violence on employment stability. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(6), 1282–1304. 10.1177/0886260510368160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson J. (1996). Davidson trauma scale (DTS) manual. Multi-Health Systems Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson H., Tharwani J., Connor K. (2002). Davidson trauma scale (DTS): nomative scores in the general population and effect sizes in placebo controlled trials. Depression and Anxiety, 15(2), 75–78. 10.1002/da.10021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies L., Ford-Gilboe M., Willson A., Varcoe C., Wuest J., Campbell J., Scott-Storey K. (2015). Patterns of Cumulative Abuse Among Female Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence Links to Women’s Health and Socioeconomic Status. Violence Against Women, 21(1), 30–48. 10.1177/1077801214564076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries K. M., Mak J. Y., Bacchus L. J., Child J. C., Falder G., Petzold M., Watts C. H. (2013). Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: A Systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Medicine, 10(5), e1001439. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon G., Hussain R., Loxton D., Rahman S. (2013). Mental and physical health and intimate partner violence against women: a review of the literature. International Journal of Family Medicine, 2013(), 313909. 10.1155/2013/313909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot D., Bjelajac P., Fallot R. D., Markoff L. S., Reed B. G. (2005). Trauma-informed or trauma-denied: Principles and implementation of trauma-informed services for women. Journal of Community Psychology, 33(4), 461–477. 10.1002/jcop.20063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M., Varcoe C., Noh M., Wuest J., Hammerton J., Alhalal E., Burnett C. (2015). Patterns and Predictors of Service Use Among Women Who Have Separated from an Abusive Partner. Journal of Family Violence, 30(4). 10.1007/s10896-015-9688-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M., Wuest J., Davies L., Merritt-Gray M., Campbell J., Wilk P. (2009). Modelling the effects of intimate partner violence and access to resources on women’s health in the early years after leaving an abusive partner. Social Science & Medicine, 68(6), 1021–1029. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M., Wuest J., Merritt-Gray M. (2005). Strengthening capacity to limit intrustion: Theorizing family health promotion in the aftermath of woman abuse. Qualitative Health Research, 15(4), 477–501. 10.1177/1049732305274590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno C., Hegarty K., d’Oliveira A. F. L., Koziol-McLain J., Colombini M., Feder G. (2015. a). The health-systems response to violence against women. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1567–1579. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61837-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno C., Zimmerman C., Morris-Gehring A., Heise L., Amin A., Abrahams N., Watts C. (2015. b). Addressing violence against women: a call to action. Lancet (London, England), 385(9978), 1685–1695. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61830-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia L., Qi L., Rasor M., Clark C. J., Bromberger J., Gold E. B. (2014). The relationship of violence and traumatic stress to changes in weight and waist circumference: longitudinal analyses from the study of women’s health across the nation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(8), 1459–1476. 10.1177/0886260513507132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber M. R., Wittenberg E., Ganz M. L., Williams C. M., McCloskey L. A. (2008). Intimate partner violence exposure and change in women’s physical symptoms over time. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(1), 64–69. 10.1007/s11606-007-0463-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedtke K. A., Ruggiero K. J., Fitzgerald M. M., Zinzow H. M., Saunders B. E., Resnick H. S., Kilpatrick D. G. (2008). A longitudinal investigation of interpersonal violence in relation to mental health and substance use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 633–647. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill T. D., Schroeder R. D., Bradley C., Kaplan L. M., Angel R. J. (2009). The long-term health consequences of relationship violence in adulthood: an examination of low-income women from Boston, Chicago, and San Antonio. American Journal of Public Health, 99(9), 1645. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.151498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson W. W., McIntosh S. R. (1981). The assessment of spouse abuse: two quantifiable dimensions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 43(4), 873–885. 10.2307/351344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys J.C., Epel E. S., Copper B. A., Lin J., Blackburn E. H., Lee K. A. (2012). Telomere shortening in formerly abused and never abused women. Biological Research in Nursing, 14(2), 115–123. 10.1177/1099800411398479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman M. A., Bleau P., Blier P., Chokka P., Kjernisted K., Van Ameringen M., Szpindel I. (2014). Canadian clinical practice guldelines for the managment of anxiety, posttraumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 14(SUPPL.1)(SI). 10.1186/1471-244X-14-S1-S1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeshin B. R., Cronholm P. F., Strawn J. R. (2012). Physiologic changes associated with violence and abuse exposure. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 13(1), 41–56. 10.1177/1524838011426152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause E. D., Kaltman S., Goodman L. A., Dutton M. A. (2008). Avoidant coping and PTSD symptoms related to domestic violence exposure: a longitudinal study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(1), 83-90. 10.1002/jts.20288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Flair L. N., Bradshaw C. P., Campbell J. C. (2012). Intimate partner violence/abuse and depressive symptoms among female health care workers: Longitudinal findings. Women’s Health Issues, 22(1). 10.1016/j.whi.2011.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagdon S., Armour C., Stringer M. (2014). Adult experience of mental health outcomes as a result of intimate partner violence victimisation: a systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 24794. 10.3402/ejpt.v5.24794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold T. (2018). Gender differences in the consequences of divorce: a study of multiple outcomes. Demography, 55(3), 769–797. 10.1007/s13524-018-0667-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loxton D., Dolja-Gore X., Anderson A. E., Townsend N. (2017. a). Intimate partner violence adversely impacts health over 16 years and across generations: a longitudinal cohort study. PLoS One, 12(6), e0178138. 10.1371/journal.pone.0178138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loxton D., Townsend N., Cavenagh D., Green L., Graves A., Hiles J., Kabanoff S. (2017. b). Measuring domestic violence in longitudinal research. University of Newcastle. https://plan4womenssafety.dss.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Measuring-Domestic-Violence-in-Longitudinal-Research.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Machtinger E. L., Davis K. B., Kimberg L. S., Khanna N., Cuca Y. P., Dawson-Rose C., McCaw B. (2019). From treatment to healing: inquiry and response to recent and past trauma in adult health care. Women’s Health Issues, 29(2), 97–102. 10.1016/j.whi.2018.11.003. 30606467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason S. M., Ayour N., Canney S., Eisenberg M. E., Neumark-Sztainer D. (2017). Intimate partner violence and 5-year weight change in young women: a longitudinal study. Journal of Women’s Health, 26(6), 677–682. 10.1089/jwh.2016.5909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason S.T., Lauterbach D., McKibben J.B.A., Lawrence J., Fauerbach J.A. (2013. b). Confirmatory factor analysis and invariance of the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) in a longitudinal sample of burn patients. Psychological Truama: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 5(1), 10–17. 10.1037/a0028002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason S. M., Wright R. J., Hibert E. N., Spiegelman D., Jun H. J., Hu F. B., Rich-Edwards J. W. (2013. a). Intimate partner violence and incidence of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care, 36(5), 1159–1165. 10.2337/dc12-1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. S., Gianaros P. J. (2010). Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1186, 190–222. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05331.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane J., Parker B., Soeken K., Bullock L. (1992). Assessing for abuse during pregnancy: severity and frequency of injuries and associated entry into prenatal care. JAMA, 267(23), 3176–3178. 10.1001/jama.1992.03480230068030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertin P., Mohr P. (2001). A follow-up study of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression among Australian victims of domestic violence. Violence and Victims, 16(6), 645–654. 11863063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton S.C., Szabo Y.Z., Newton T.L. (2022). Mental and physical health changes following an abusive intimate relationship: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Trauma, Violence and Abuse, 23(4), 1079–1092. 10.1177/1524838020985554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen J. S., Malcoe L. H., Pulkingham J. (2013). Explaining aboriginal/non-aboriginal inequalities in postseparation violence against canadian women: application of a structural violence approach. Violence Against Women, 19(8), 1034–1058. 10.1177/1077801213499245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponic P., Varcoe C., Davies L., Ford-Gilboe M., Wuest J., Hammerton J. (2011). Leaving ≠ Moving. Violence Against Women, 17(12), 1576–1600. 10.1177/1077801211436163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponic P., Varcoe C., Smutylo T. (2016). Trauma- (and violence-) informed approaches to supporting victims of violence: Policy and practice considerations. Victims of Crime Research Digest 9. 10.1080/09515070701685713 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajah V., Osborn M. (2020). Understanding women’s resistance to intimate partner violence: a scoping review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 23(5). 10.1177/1524838019897345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheingold A., Acierno R., Resnick H. (2004). Trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and health risk behaviors. In Schnurr P., Green B. (Eds.), Trauma and health: physical health consequences of exposure to extreme stress (pp. 217–243). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Samulowitz A., Gremyr I., Eriksson E., Hensing G. (2018). “Brave men” and “emotional women”: A theory-guided literature review on gender bias in health care and gendered norms towards patients with chronic pain (p. 6358624). Pain Research & Management. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Lorente S., Blasco-Ros C., Martínez M. (2012). Factors that contribute or impede the physical health recovery of women exposed to intimate partner violence: a longitudinal study. Women’s Health Issues, 22(5), e491–e500. 10.1016/j.whi.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Storey K. (2011). Cumulative abuse: do things add up? an evaluation of the conceptualization, operationalization, and methodological approaches in the study of the phenomenon of cumulative abuse. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 12(3), 135–150. 10.1177/1524838011404253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Storey K., Hodgins M., Wuest J. (2019). Modeling lifetime abuse and cardiovascular disease risk among women. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders, 19(1). 10.1186/s12872-019-1196-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smye V., Varcoe C., Browne A., Dion Stout M., Josewiski V., Ford-Gilboe M. (2020). Violence at the Intersections of Women’s Lives in an Urban Context: Indigenous Women’s Experiences of Leaving and/or Staying With an Abusive Partner. Violence Against Women, 27(10), 1586–1607. 10.1177/1077801220947183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam M. T., Ford-Gilboe M., Regan S. (2015). Primary health care service use among women who have recently left an abusive partner: income and raciialization, unmet need, fits of services, and health. Health Care for Women International, 36(2), 161–187. 10.1080/07399332.2014.909431. 247630688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stene L. E., Jacobsen G. W., Dyb G., Tverdal A., Schei B. (2013). Intimate partner violence and cardiovascular risk in women: a population-based cohort study. Journal of Women’s Health, 22(3), 250–259. 10.1089/jwh.2012.3920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvak M. K., Taft C. T., Goodman L. A., Dutton M. A. (2013). Dimensions of functional social support and depressive symptoms: a longitudinal investigation of women seeking help for intimate partner violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(3), 455–466. 10.1037/a0031787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarzia L., Bohren M. A., Cameron J., Garcia-Moreno C., O’Doherty L., Fiolet R., Hegarty K. (2020). Women’s experiences and expectations after disclosure of intimate partner abuse to a healthcare provider: a qualitative meta-synthesis. BMJ Open, 10(11), e041339. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temmerman M. (2015). Research priorities to address violence against women and girls. The Lancet, 385(9978), e38–e40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61840-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari A., Fong D. Y. T., Chan C. H., Ho P. C. (2013). Factors mediating the relationship between intimate partner violence and chronic pain in Chinese women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(5), 1067–1087. 10.1177/0886260512459380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treede R. D., Rief W., Barke A., Aziz Q., Bennett M. I., Benoliel R., Wang S. J. (2015). A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain, 156(6), 1003–1007. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai A. C., Tomlinson M., Comulada W. S., Rotheram-Borus M. J. (2016). Intimate partner violence and depression symptom severity among South African women during pregnancy and postpartum: population-based prospective cohort study. PLoS Medicine, 13(1), e1001943. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutty L. M., Radtke H. L., Thurston W. E. B., Ursel E. J., Nixon K. L., Hampton M. R., Ateah C. A. (2020). A longitudinal study of the well-being of Canadian women abused by intimate partners: a healing journey. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 30(9), 1–23. 10.1080/10926771.2020.1821852 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ameringen M., Mancini C., Patterson B., Boyle M. H. (2008). Post-traumatic stress disorder in Canada. CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics, 14(3), 171–181. 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00049.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varcoe C., Ford-Gilboe M., Browne A., Perrin N., McKenzie H., Stout M. (2019). The Efficacy of a Health Promotion Intervention for Indigenous Women: Reclaiming Our Spirits. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1). 10.1177/0886260518820818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M., Ormel J., Keefe F. J., Dworkin S. F. (1992). Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain, 50(2), 133–149. 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker N., Beek K., Chen H., Shang J., Stevenson S., Williams K., Herzog H., Ahmed J., Cullen P. (2020). The Experiences of Persistent Pain Among Women With a History of Intimate partner Violence: A Systematic Review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 10.1177/1524838020957989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wathen N., Varcoe C. (Eds.). (2022). Implementing Trauma- and Violence-Informed Care: A Handbook for Health and Social Services. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins L. E., Jaffe A. E., Hoffman L., Gratz K. L., Messman-Moore T. L., DiLillo D. (2014). The longitudinal impact of intimate partner aggression and relationship status on women’s physical health and depression symptoms. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(5), 655–665. 10.1037/fam0000018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2013). Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines. World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright E. N., Hanlon A., Lozano A., Teitelman A. M. (2018). The association between intimate partner violence and 30-year cardiovascular disease risk among young adult women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(11-12), NP6643–NP6660. 10.1177/0886260518816324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuest J., Ford-Gilboe M., Merritt-Gray M., Berman H. (2003). Intrusion: The Central Problem for Family Health Promotion among Children and Single Mothers after Leaving an Abusive Partner. Qualitative Health Research, 13(5), 597–622. 10.1177/1049732303013005002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuest J., Ford-Gilboe M., Merritt-Gray M., Wilk P., Campbell J., Lent B., Smye V. (2010). Pathways of chronic pain survivors of intimate partner violence: Considering abuse-related injury, symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, depressive symptoms, and child abuse. Journal os Women’s Health, 19(9), 1665–1674. 10.1089/jwh.2009.1856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuest J., Merritt-Gray M., Dubé N., Hodgins M. J., Malcolm J., Majerovich J. A., Scott-Storey K., Ford-Gilboe M., Varcoe C. (2015). he Process, Outcomes, and Challenges of Feasibility Studies Conducted in Partnership With Stakeholders: A Health Intervention for Women Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. Research in Nursing & Health, 38(1), 82–96. 10.1002/nur.21636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuest J., Merritt-Gray M., Ford-Gilboe M., Lent M., Varcoe C., Campbell J. C. (2008). Chronic Pain in Women Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. The Journal of Pain, 9(11), 1048–1057. 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-jiv-10.1177_08862605221090595 for Trajectories of Depression, Post-Traumatic Stress, and Chronic Pain Among Women Who Have Separated From an Abusive Partner: A Longitudinal Analysis by Marilyn Ford-Gilboe, Colleen Varcoe, Judith Wuest, Jacquelyn Campbell, Michelle Pajot, Lisa Heslop, and Nancy Perrin in Journal of Interpersonal Violence