Abstract

The history and recent developments of conservation biological control (CBC) in the context of industrialized and small-scale agriculture are discussed from theoretical framework available in the Neotropical region. A historical perspective is presented in terms of the transition of the way pests have been controlled since ancestral times, while some of these techniques persist in some areas cultivated on a small-scale agriculture. The context of industrialized agriculture sets the stage for the transition from chemical pesticides promoted in the green revolution to the more modern concept of IPM and finds in conservation biological an important strategy in relation to more sustainable pest management options meeting new consumer demands for cleaner products and services. However, it also noted that conservation, considered within a more integrative approach, establishes its foundations on an overall increase in floral biodiversity, that is, transversal to both small-scale and industrialized areas. In the latter case, we present examples where industrialized agriculture is implementing valuable efforts in the direction of conservation and new technologies are envisioned within more sustainable plant production systems and organizational commitment having that conservation biological control has become instrumental to environmental management plans. In addition, a metanalysis on the principal organisms associated with conservation efforts is presented. Here, we found that hymenopteran parasitoids resulted in the most studied group, followed by predators, where arachnids constitute a well-represented group, while predatory vertebrates are neglected in terms of reports on CBC. Our final remarks describe new avenues of research needed and highlight the need of cooperation networks to propose research, public outreach, and adoption as strategic to educate costumers and participants on the importance of conservation as main tool in sustainable pest management.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13744-022-01005-1.

Keywords: Small-scale agriculture, Large-scale agriculture, Meta-analysis, Entomophagous, Natural enemies

The history and recent developments of the conservation biological control

From the green revolution to pest management programs focused on biological control

Diseases and pests in the agricultural sector cause different types of yield losses depending on the crop and the causing agent. Therefore, farmers are continuously searching for efficient and affordable alternatives of control, chemical insecticides, or chemical pesticides currently stand out as the main alternative for agricultural pest control, although are not necessarily the most sustainable (Bernardes et al. 2015; Daam et al. 2019; Nicholls 2008). The group of substances known as pesticides pertains to compounds used as insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, rodenticides, molluscicides, and nematicides (Bernardes et al. 2015). The use of pesticides has been considerably higher in the twenty-first century. The exponential growth of the human population in the eighteenth century and the increase of agricultural production, also known as the green revolution of the twentieth century, in which technological improvements were produced that even led to doubling the yield of some cereals for mass consumption (Bernardes et al. 2015; Khush 1995), were based on products of non-specific toxicity for massive use (Martínez-Centeno and Huerta 2018). During this period, changes such as the increased use of pesticides, inorganics fertilizers, and water were implemented in agricultural production, favoring the operation or large-scale intensive monoculture systems (Khush 1995; Romero 2012).

Chemical pesticides have been intensively used to prevent crop yield losses and increase efficiency in pest management (Mahmood et al. 2016). Its worldwide pesticide has increased its production at a rate of about 11% per year, from 0.2 million tons in the 1950s to more than 5 million tons by 2000 (Carvalho 2017). However, since the last century, several countries have warned of adverse effects on humans and non-target organisms, mainly caused by improper use or accidents (Rosival 1985; Carvalho 2017). And although efforts have been made to evaluate the effect on aquatic ecosystems, there is little information on the impact on the structure and function of terrestrial ecosystems (Daam et al. 2019), while there is also no full guarantee on its efficiency. Even so, the increase in the use of pesticides has not been adequately followed by studies that verify their environmental effects in tropical countries, and therefore, the requirements for their use are not available, are unclear, or are implemented and applied in an inadequate way, whereas in North America, Europe, and other countries such as Japan and Australia, there is a well-established legal framework (Daam et al. 2019).

On the contrary, the frequent outbreaks of secondary pests after applications and the increasing prevalence of resistant pests have pointed the risks of dependence on these substances in relation to the environment, biodiversity, and human health (Bernardes et al. 2015; Boedeker et al. 2020; Bruinsma 2003; Del Puerto Rodríguez et al. 2014; Mahmood et al. 2016; Ruberson et al. 1998; WHO/OPS 1993). In addition, agrochemicals, mechanization, and irrigation operations, which are at the heart of industrial agriculture, are highly dependent on fossil fuels, are increasingly scarce, and, consequently, are more expensive (Altieri and Nicholls 2012). In perspective, the future of pesticides seems to tend towards less harmful chemical groups capable of selectively acting on specific targets while sparing on other components of the agroecosystem (Bruinsma 2003; Matthews 2015; Mahmood et al. 2016).

During the last years, in different regions of the world, the focus of agricultural production, addressing environmental and socioeconomical impacts, has been reconsidered towards a more ancestral form of pest management (i.e., traditional), evolving within the framework of new scientific and technological knowledge. It is perceived as necessary to reduce risks and consider other more sustainable and more effective production modes (Tilman et al. 2002). New practices in agriculture include small changes such as increase diversity of plants associated with the crop and chemical pesticide elimination or avoiding herbicides to help increase biodiverse populations that include natural enemies (NE), such as parasitoids, predators, pathogens, and antagonists (Letourneau et al. 2011; Nicholls 2008; Peñalver-Cruz et al. 2019). This approach does not eliminate rational use of pesticides, resistant crop varieties, and ecological pest control (Bruinsma 2003), but adds natural products and systems as an alternative to chemical pesticides (Chirinos et al. 2020; Souto et al. 2021; Muhammad et al. 2022).

From the integrated pest management (IPM) and ecological pest management (EPM) perspectives, to sustain productivity with minimum adverse effect on the environment (especially on pollinators and other beneficial fauna) (Egan et al. 2020), biological control has the potential of becoming the main strategy for pest management in intensive agriculture (UNODC 2010). This approach emerged for prevention, monitoring, and rapid identification of the pest(s) and disease(s) and their effective control by a coordinated use of all accessible technologies. For this reason, through a systematic knowledge on crop biology and the biology of their pests and diseases, it uses its NE to suppress them (UNODC 2010; Nicholls 2008; Owen et al., 2015). The biological control concept has been developed primarily by entomologists and is normally associated to the use of living NE to control pests, either through importation of exotic NE against either exotic or native pests (i.e., classical biological control), augmentation of already existing NE, and conservation of such existing NE (Ehler 1998).

Conservation biological control (CBC) is a strategy that seeks to modify the environment biodiversity to provide habitat and resources that protect and enhance NE to reduce pest’s effects in crop systems (DeBach 1964; Moses 1993). Such modification may be directed at mitigating harmful conditions or enhancing favorable ones (Landis et al. 2000). The core of the strategy is the biotic interactions between pests and their wild NE, whether they are predators, parasitoids, or entomopathogens. The premise is that if habitat loss and environmental changes associated with intensive agricultural practices are compensated, NE are conserved and therefore pest population would be controlled. The possibility of incrementing effective beneficial arthropods populations will depend on the availability of food, refuge, and other resources with in and around the crop field (Huffaker and Messenger 1976).

Therefore, CBC is a sustainable tool compatible with agroecological, organic, and other forms of agriculture based on the increase of natural agroecological processes and the elimination or reduction of chemical agents (Nicholls 2008), which have long overshadowed the importance of NE in pest management. It has been used to reverse harmful effects of intensive practices in agriculture, such as disturbance associated with extensive use of pesticides (Paredes et al. 2013), tillage, burning, and other agronomic interventions (Barbosa 1998). It differs from other biological control approaches in the way that is does not rely on massive releases of organisms, but in promoting a set of environment interventions, so biodiversity and crop can thrive (Barbosa 1998). However, even though pesticides and NE have often been viewed as incompatible, in some cases, there have been programs that develop pesticides that have minimal environmental impact and exhibit greater selectivity to NE (Ruberson et al. 1998), especially in agroecosystems highly dependent on chemical control (Torres and Bueno 2018). However, multiple field experiments have shown that pesticide applications do not significantly reduce pest density but do affect NE in most cases (Janssen and van Rijn 2021). Therefore, its main trend points to the reduction of pesticides from the management program to improve the abundance of NE in the crop, limiting pest infestations. In general, CBC does not exercise pest control directly; instead, it promotes the abundance and diversity of NE which are already present in the agroecosystem (Paredes et al. 2013), so it becomes a preventive measure within an integrative pest management system and an integrative crop production approach (Begg et al. 2017; Díaz et al. 2018). In this regard, NE populations’ responses to conservation strategies are not always consistent with pest suppression or the increase of crop yields, so it has been relegated and rarely used in commercial crop production (Begg et al. 2017) .

The general scenario of conservation biological control in the Neotropical region

The Neotropical region is the most biodiverse ecoregion and highly productive in terms of agricultural outputs. Therefore, it is an important scenario for biological control programs, since part of this great diversity are NE of different kinds (Smith and Bellotti 1996). In this region, CBC programs are strategic to conserve biodiversity in landscapes dominated by agriculture, since most of their practices involve the conservation of refuges for associated fauna providing protection against environmental threats (e.g., high temperatures, drought, and climate change), as well as biological (e.g., pest outbreaks) and anthropic threats (e.g., habitat loss and hunting) (Selwood and Zimmer 2020).

Although conservation of NE is probably the oldest form of biological control (Barbosa 1998), in the Neotropical region, the situation of CBC seems paradoxical as it has been widely practiced by traditional farmers, but it is the least recognized (i.e., documented) and least financially supported, at least at the level of small-scale farming. In addition, it tends to be displaced by chemical insecticides. However, in some Latin American contexts, traditional agriculture is distinguished by the diversity it establishes in agricultural designs, in the diversity of plant species and genotypes, thus suffering less frequent pest attacks than those observed in monocultures (Trujillo 1992; Altieri and Nicholls 2012).

Many of the practices carried out in traditional agriculture that are observed in the Neotropical region could be incorporated into modern designs of agricultural production. But various factors limit its implementation, for example, the strong focus on classical biological control and/or augmentation, with special emphasis on the use of parasitoids (Colmenarez et al. 2018), which is the most widespread and credible practice. In addition, many of the successful cases of CBC are not documented, since it is a daily practice of traditional farmers (Trujillo 1992), which limits producers to have more access to implementation methods and to understand their benefits. The latter does not contribute to a better understanding of the response of NE on pests (Begg et al. 2017) and confronted by short-term expectations, limits its practice in traditional small-scale crops.

Extensive deforestation in the late twentieth century threatens the diversity of the Neotropics (Rull 2011). The reduction of species could deteriorate the processes of the ecosystem while the increase in diversity leads to more stability (Elton 1958). Agricultural and forestry activities seem to indicate that systems poor in species are not very stable; therefore, agricultural practices that conserve functional biodiversity are relevant. CBC models that include natural vegetation associated with crops allow the presence of a high diversity of organisms and functional groups that can act as pest regulators in the crop, while additionally being a form of conservation (Rivera-Pedroza et al. 2019).

Understanding the ecosystem guidelines of the CBC and overcoming immediate expectations to control pests could expand the use of this practice as a fundamental tool of IPM programs in the Neotropics. In this sense, CBC requires an articulation to integrated crop management practices, and a more holistic approach considering landscape implications on different scenarios and the environmental effects of establishing or sustaining any agricultural activity. In this regard, if we consider farming in general as an agribusiness activity, all regulations and modern administrative methodologies apply in relation to formulating agricultural projects by ensuring the well-being of workers, final costumers, and the environment in general. Even though the latter could be attributed mainly to the socioeconomical context of industrial agriculture, Environmental Management Plans are benefiting from the concepts and implementation of CBC in relation to the mitigation of potentially adverse environmental impacts of the different agricultural projects.

Of course, CBC techniques differ greatly between geographic areas and between extensive agricultural management or in peasant agriculture, especially because, in Latin America, what is considered extensive or small-area agriculture also differs from one country to another. In this review, we consider industrialized agriculture as those areas in which most of the labor is hired and with intensive use of agricultural machinery, high technology, and industrialization of the entire production process, including the final commercialization of the product. On the other hand, we consider small-scale agriculture, those areas depending on family labor, or peasant agriculture, with the use of traditional technology, often associated with community groups. Here, we are discussing the potential of CBC under small and industrialized scale agriculture and indicating which are the principal organisms associated with conservation in the Neotropical region.

Conservation biological control in small-scale agriculture in the Neotropical region

Ancestral ways of dealing with pests

If we look for historical references of agricultural production after European colonization in small rural properties, or even in gardens in urban areas in Latin America, we will find records of environmental architecture seeking to associate food, medicinal and ornamental plants, and animals for human consumption. In the historical context, the concepts of vegetable garden, backyard, orchard, flower garden, and leisure area were mixed (Carneiro and Bertruy 2009). This type of environmental management, registered in different Latin American countries, sought firstly, to increase productivity and food diversification in small areas. Indirectly, these spaces maximized the ecological services provided by an associated biota that obviously included biological pest control (Chapling-Kramer and Kremer 2012). Empirical experiments, carried out by different ethnic groups and passed on orally to several generations, produced different spatial arrangements for subsistence purposes. The knowledge of native peoples was incorporated, adding many elements of native flora to the diet and, consequently, to vegetable gardens, orchards, and cultivated gardens (Melo and Melo 2015).

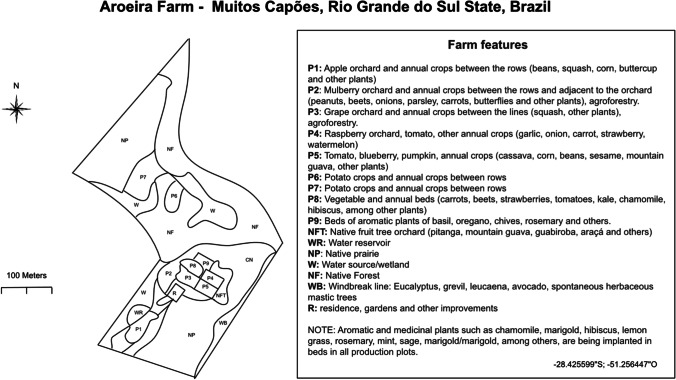

Examples of these spaces can still be found in peasant agricultural communities, presenting a great diversity of agricultural systems, widely associated with the vernacular landscape of each place. The term “vernacular landscape” was proposed by Jackson (1984) and refers to landscapes resulting from successive interactions between local communities and their natural environment, including the genetic variety of plants and animals available and presenting a primary connection with functionality, of where the transformation of the local material takes place (Petry 2014; Frank and Yamaki 2018). Thus, although each region has particularities associated with native flora and fauna and the ethnic elements present, the basic structure related to functional diversity is always present, as in the area used as an example in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Sketch representing an agroecological farm with family labor with small production plots and a mosaic of habitats (cultivated and uncultivated) as well as refuge areas (hedges, forests) in southern Brazil

When agroecology studies began to emerge in the Americas, in the late 1970s and 1980s, pioneered by researchers such as Altieri, Gliessman, Ana Primavesi, and Lutzenberg among others, these models of agriculture started to be rescued and studied (Lutzenberger 1978; Primavesi 1984a, b; Altieri 1989; Gliessman 1998). The beneficial effects of diversity and the importance of plant architecture in the agroecosystem started to be accounted for. The hypothesis connecting ecological mechanisms for pest suppression via habitat diversification was solidified by Root (1973) and was one of the contributions that most influenced the discipline of CBC through habitat manipulation. Thus, in the Neotropical region, the bases for CBC were first established in small rural properties, with family and peasant labor.

Many aspects of the ancient agricultural management could be considered CBC, but those management practices are rarely identified as such. One of these ancient practices includes the increment of plant diversity through intercropping (Thrupp 2000). For example, agroforestry systems containing dozens of plant species are common in South America. Likewise, since prehispanic times, it has been quite common to intercrop maize with other plant species (especially leguminous species) (Thrupp 2000).

An integrative production system

Studies related to CBC in small farms, which encompass different production systems, are much more recent (Wyckhuys and O’Neil 2007). This kind of research has increased recently in some developing countries such as Brazil and Cuba (Wyckhuys et al. 2013), but is rather lacking in others. These works have been looking to explore our own biodiversity and understand how the spatial arrangements and genetic variety of plants influence the ecological services provided by beneficial organisms, especially NE (Wyckhuys et al. 2013; Peñalver-Cruz et al. 2019). Our focus in this review will be on arthropods with entomophagous habits, NE of insects that attack cultivated plants and their effects on the management of these pests.

Let us use as a basis the sketch shown in Fig. 1. This sketch was based on a 12-ha rural property, Sítio Aroeira, located in the municipality of Muitos Capões, in Rio Grande do Sul, in the extreme south of Brazil. In this area, there is a large part covered with native forest that surrounds and intermediates the property. The property is family-based, certified for organic production, and maintains ecologically based cultivation systems (agroecology) with different managements in the area. It is possible to observe a great diversity of crops intermingled with natural environments such as forest, prairie, and wetlands (Fig. 1). Understanding how these environments increase the presence and permanence of NE and other beneficial insects in agricultural areas is one of the main focuses of studies in CBC. Crop diversification and implementation of additional resources for NE and the impact of this on pest populations and crop productivity is another major focus of research. According to Heimpel and Mills (2017), the two most recorded classes of habitat manipulation are “improving michohabitats for NE” and “resource supplementation.”

The species richness of NE in an environment, by itself, may not be sufficient to suppress pest populations (Letourneau et al. 2009), being necessary to know the NE associated with pests, since the species composition is fundamental (Alhadidi et al. 2018). Works that seek to identify potential NE of agricultural pests are developed in different countries in Latin America and may constitute a first step towards the implementation of CBC. An example of this is the work carried out by the PROINPA Foundation in Bolivia whose project seeks technological strategies for the sustainable management of quinoa in the Bolivian Altiplan. These surveys, however, are often restricted to technical bulletins or project reports (PROINPA 2013). Surveys of predators and parasitoids have been carried out throughout Latin America for pests belonging to different orders, such as Lepidoptera (Gómez-Jiménez 2018; Vargas 2018 – Colombia; Ribeiro et al. 2015 – Uruguay), Hemiptera (Pavis et al. 2003 – Guadaloupe; Ribeiro and Castiglioni 2008 – Uruguay; Gaimari, et al. 2012 – Colombia), and Diptera (Ovruski et al. 2000 – Latin America and Southern United States; García-Cancino et al. 2015 – Mexico; Hernandez-Mahecha et al. 2018 – Colombia) in addition to other herbivorous insects. Also in Paraguay, surveys of NE have been carried out in small areas, on crops such as peanuts, sesame, beans, and corn (Cabral-Antúnez, et al. 2020). More detailed descriptions of NE surveys are in an additional section of this document.

In Fig. 1, we can also see several small forest areas, called “legal reserve” by Brazilian Law 12.651/12 (Brasil 2012), interspersed with crop areas. These wild vegetation areas can serve as a repository of NE, for both parasitoids (da Silva et al. 2016, 2019) and predators (Ferreira et al. 2014; Medeiros et al. 2018) of insect crop pests. Studies evaluating the effect of wild vegetation areas on the composition of beneficial arthropod fauna, and especially NE, are carried out as one of the first assumptions for the CBC. For example, on small coffee farms in Colombia, Armbrecht and Gallego (2007) evaluated the diversity of predatory ants and the predation rate in plantations shaded by native forest compared to plantations in the sun. Comparison of the parasitoid fauna (da Silva et al. 2016) and predators (Ferreira et al. 2014) between an area of preserved native vegetation and organic rice alongside showed that around 40% of the entomophagous species are shared. Both studies indicate the importance of native vegetation for the biological control of conservation at the site.

Adaime et al. (2018) also show the importance of fruit trees that occur naturally in preserved areas for the maintenance of parasitoid of Anastrepha spp. (fruit fly) (Tephritidae) in the Brazilian Amazon. In agroforestry systems in Costa Rica, plants with alternative hosts of hymenopteran parasitoids of borers and other sap-sucking pests in pecan nut crops also have been identified (Mexzón 2001), showing that plant diversity in an agroecosystem can influence the abundance of predators (Barbosa and Wratten 1998), as well as parasitoids, for which plants act as mediators of chemical communication, refuge, and food resource (Barbosa and Benrey 1998).

The evaluation of the effect of non-target plants in fallow areas, in windbreaks or simply on the edges of crops and their management in the CBC, has been the subject of many studies. Predators of the Chrysopidae and Coccinellidae families, for example, circulate between pastoral systems and areas of adjacent managed vegetation in Uruguay and do pest control on aphids and grazing mites (Ribeiro 2010). In organic management properties in Brazil, with production of at least 16 types of species of vegetable, a great richness of predators and herbivores in non-cropped habitats was recorded. Furthermore, all the habitats share species of natural NE throughout the year, indicating that species could disperse among habitats (Togni et al. 2016, 2019). Amaral et al. (2013) had already evaluated the role of non-cultivable weeds for the maintenance of aphidophagous predators in tropical agroecosystems associated with chilli pepper crops. The authors suggest that the management of specific weed species can provide an optimal strategy for the conservation of beneficial insects that use non-predatory foods. Non-crop habitats were also investigated in Chile and the authors showed that some parasitoids such as Aphelinus mali (Haldeman) (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae) precociously colonize apple orchards maximizing the control of Eriosoma lanigerum (Hausmann) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) near edges with the presence of wild plants (Peñalver-Cruz et al. 2020).

Floral resources close to or between cultivated areas (Fig. 1) are a common characteristic among small properties and rural labor throughout Latin America. The importance of flowers in attracting and maintaining NE, especially parasitoids, is widely studied (Pfiffner and Wyss 2004). The introduction of floral resources, in the already known flower strips, or in different arrangements, associated with crops, and their effects on the diversity of NE and on pest control have been the focus of many studies in Latin America. In Cuba, this focus has been explored and studied, with works that contribute to the knowledge of potential botanical species for the maintenance and reservoir of NE and other beneficial insects, especially in urban agriculture (Matienzo et al. 2007; Ceballos et al. 2009). In Colombia, the performance of Trichogramma atopovirilia Oatman and Platner (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) was studied according to the presence of different flower species and found that the presence of Trifolium pratense L. (Fabales: Fabaceae) was the most adequate to optimize the parasitoid in the field (Díaz et al. 2012).

Floral biodiversity on small-scale farms

The temporal and spatial variation of floral communities marginal to agroecosystems and the spatial and seasonal diversity of associated insects were evaluated in vegetable gardens in Cordoba, Argentina (Rojas-Rodrigues et al. 2019). This work shows that the abundance of insects in different plants increased significantly with the number of samplings where floral species were present. In Brazil, a study showed that Alisso, Lobularia maritima (L.) (Brassicales: Brassicaceae) strips between rows with beds of Brassica oleracea (L.) (Brassicales: Brassicaceae), contributed to increase the abundance of generalist predators which translated into a significant reduction of collards pests, especially aphids (Ribeiro and Gontijo 2016). Haro et al. (2018) also showed that there is a variation in the richness and abundance of specialist and generalist NE in different periods of development of non-target plants such as Tagetes erecta L. (Asterales: Asteraceae) in crops. The flowering period favored greater complexity in the food web, increasing the functional stability of the community in the agroecosystem.

In addition to the specific composition of the plants, the strips of wild plants must be integrated into the culture in a practical way for producers and distributed in space and time so that they favor NE (Jahnke and da Silva 2021). Thus, there are suggestions for arranging wildflowers and plants between crops, such as those made by Aguiar-Menezes and Silva (2011), in a technical bulletin, aimed at farmers.

Crops in consortium and agroforestry systems have also been the target of studies related to CBC, especially in peasant agriculture with little tech. In vegetable production, there is a record of consortia of sweet pepper, Capsicum annuum L. (Solanales: Solanaceae), associated with basil, Ocimum basilicum L. (Lamiales: Lamiaceae), and marigold, Tagetes erecta L. (Asterales: Asteraceae) that significantly increased the presence of parasitoids compared to single pepper crop (Souza et al. 2018). In a perennial plant production system, the beneficial effects of the associated diversity become even more explicit, since a brief ecological succession is allowed in the area, making the agricultural system to be situated in an associative phase concerning the community (Gliessman 2001). At this stage of development, more adapted species manage to establish themselves and occupy important niches for the system’s functionality (Odum 1988). In this way, systems served as a source of NE that can colonize horticultural crops when herbivores are present. Consequently, NE can establish a numerical response to herbivore abundance (Harterreiten-Souza et al. 2014). This effect was observed by evaluating the action of different plant covers on the arthropod community in apple orchards in Argentina (Fernández et al. 2008) or by evaluating the structure of the insect community concerning the integration of plant crops in agroforestry in Brazil (Harterreiten-Souza 2014). Also, Hoshino et al. (2018) found a lower infestation of the coffee leaf miner (CLM) Leucoptera coffeella (Guérin-Mèneville and Perrottet) (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae) in an organic coffee crop intercropped with pigeon pea plants, Cajanus cajan (L. Millsp.) (Fabales: Fabaceae), and greater predation by wasps in the presence of Leucaena plants, Leucaena leucocephala L. (Fabales: Fabaceae).

More recently, studies related to CBC have focused on population dynamics and spatial distribution of NE between areas. Bidirectional movement of aphid parasitoids between cultivated and uncultivated plants was documented in Argentina (Zumoffen et al. 2017). In this work, variables that interfere in this dynamic were described, indicating that the abundance of alternative host aphids is decisive, thus inferring that the natural vegetation has an important role in pest control. The evaluation of quantitative indices showed that trophic networks between legume-aphid-parasitoids and entomopathogens vary in different plants cultivated in Uruguay, but the abundance of hosts and fungi is determinant for the structure of communities (Silva 2016).

Finally, the understanding of chemical interactions involved in ecological processes related to CBC has been gaining ground. Herbivory-induced plant volatiles (HIPV) play an important role in tritrophic relationships in most ecosystems and have been studied with different approaches (Ponzio et al. 2013; Becker et al. 2015). This focus was given in the work of Togni et al. (2016) who explored the mechanisms involved in the attractiveness of aphidophagous Coccinelids to Coriandrum sativum L. (Apiales: Apieaceae). Also in Brazil, Ulhoa et al. (2020) described that rice plants produce different volatiles in response to damage caused by two species of stink bugs, bringing to the plant protection to conspecific herbivores. However, parasitoids can recognize and respond positively to both stimuli. In Mexico, semi-field studies carried out in tents showed that teosinte, Z. mays spp. Parviglumis (Poales: Poaceae) produce volatiles in the presence of Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) which attract parasitoids (Lange et al. 2018). The authors commented however that the discussion about the adaptive function of HPIVs was not completely clarified.

Although the number of studies on different aspects associated with CBC has been growing, especially in small areas, many interactions are still not well understood. In agroecosystems where several components of the landscape, as in the examples we present, act as refuges (e.g., in diversified agricultural ecosystems), resource availability can vary among components or patches, allowing NE to move from one patch to another, between others. Furthermore, the specificities of each system, related to abiotic and biotic environmental issues, in addition to the entire cultural and ethnic framework, are involved. Thus, these studies must be expanded precisely in the socio-economic and environmental conditions of the Neotropical region as a whole, to seek applicable solutions for the construction of environmentally responsible and economically viable agriculture.

Conservation biological control in industrialized agriculture in the Neotropical region

New trends in final costumers’ behavior drive the change

It is possible to suggest that no other context brings more simplification of the landscape structure than industrialized agriculture, where large-scale, intensive production, often involving rutinary use of inorganic fertilizers and chemical pesticides, and synchronous monocultures result in an obvious obstacle for either planned or incidental plant diversity, this in comparison to small-scale agriculture (Rusch et al. 2014; Michaud 2018). In addition, these monotonous areas could also be facing additional pest pressures, this by the massive growing of vulnerable crop cultivars that promotes higher dependency on chemical control, driving the system in the selection for more persistent and/or insecticide-resistant herbivore pests. The latter challenges efforts on implementing biological control programs and more even the idea of CBC. However, it has been also argued that the implementation of agronomic practices is more prevalent at structuring insect communities than the landscape-level complexity (Rusch et al. 2014), so recent changes in certain agronomic practices, such as pest-resistant varieties, that require less use of pesticides; the implementation of soil conservation practices such as reduced till or not-tillage practices; and the development of more selective insecticides have the potential of benefiting the implementation of biological control (Michaud 2018).

The context of public awareness of more sustainable production of goods and services has promoted the use of certification of good practices in agriculture, meaning that industrial production of food is also heading into the direction of bringing to their consumers’ “cleaner” products. The Neotropical region, composed mainly by developing countries with economies heavily relying on exports, is facing the challenge of adapting production systems to consumer demands, so more cost-effective ways of pest control are implemented. Therefore, CBC appears as a strategic opportunity for agribusiness companies seeking both, integrated pest management and social marketing of their brands. Here, we reviewed some cases of large-scale agriculture where CBC has become an option in the Neotropics, and whose adaptations via habitat manipulation and changes in agronomic practices have the potential to influence larger areas, including those under small-scale agriculture.

Industrialized agriculture examples on efforts towards CBC in the Neotropics

Palm oil could be often associated with the destruction of natural habitats and the reduction of flora and fauna populations (Vijay et al. 2016); however, these are not necessarily the characteristics of the whole industry. The Round Table for Sustainable Palm Oil Supply Chain Certification (RSPO) has opened the door for initiatives aiming oil palm production under following environmental and social standards, this by defining agronomic recommendations towards the preservation of ecosystem services, all the latter under the scope of guidance documents containing the respective Environmental Management Plans. In this regard, Mexson and Chinchilla (2003) discussing pest management alternatives for oil palm in Costa Rica mentioned that pest’s pressure in oil palm changes with crop age. In early crop ages, the abundance of other plant resources could be the reason to a higher NE’s abundance and a reduction on pest insects. However, as the crop progresses in age, plant diversity is reduced, and number of pest insects increases. The latter authors described 30 broad leaf weed species attractive to beneficial insects, suggesting the need to preserve them in corridors nearby the cultivated palms, so biological control service can be provided to the crop.

In Colombia, according to Bustillo-Pardey (2014), the areas grown with palm oil were experiencing an increase in the early 2010s, achieving approximately 470,000 hectares. Several pests have been reported ranging from leaf feeders, sap-sucking in foliage and fruit, stem borers, among others. However, under these adverse circumstances, the goal has been to establish CBC, taking advantage of a great arrange of beneficial insects in the palm oil system (Calvache 1995). Palm oil besides being cultivated in large scale also represents a perennial crop that is expected to last at least 25 years, resembling forestal exploitations, where regulation of pests requires a landscape approach in relation to the extent of areas to manage, and here is where CBC is playing a critical role.

A Colombian cooperative business structure denominated Fedepalma through their self-financed research institute Cenipalma, has proposed and engaged in a sectorial project–denominated Biodiverse Palm Landscape (Paisaje Palmero Biodiverso) (Fedepalma 2016) with the idea of formulating basic plans to preserve and stimulate the conservation of biodiversity in the plantations and the implementation of agroecological practices. In this regard, the growth of plants that present extra-floral nectaries around the cultivated areas has been oriented to stimulate biodiversity and beneficial insects. Important economic efforts were reported by Aldana et al. (2004) in relation to the establishment of nurseries to grow 13 species of plants where a total of 15 parasitoid species were reported, with increases in the level of parasitism in pests of economic importance such as Stenoma cecropia Meyrick (Lepidoptera: Elachistidae) (Aldana et al. 1997) a leaf feeder that has demonstrated a great number of NE in the palm oil agroecosystem (Sendoya-Corrales and Bustillo-Pardey 2016).

Some extensive areas of coffee are planted in the neotropics, where also many small-scale coffee farms are in the neighboring areas. Here, the idea of CBC it has been also implemented, not necessarily with the purpose of controlling pests, but to favor diversity on agroforestry approaches, where coffee agroforestry has proven to be important at sustaining biodiversity and ecosystem services, and where intensification of crop production, usually associated to unshaded coffee, has risen concerns in terms of loss of diversity (Perfecto et al. 1996; Philpott et al. 2008).

Aside from the discussion on the replacement of traditional coffee agroforestry for more intensive production systems and its effects on meeting a growing demand for coffee, shaded coffee has demonstrated multiple attributes in the sustainability of the production in the long term, such as soil conservation, reduction of plant physiological stress, and pest regulation (Haggar et al. 2021). In this regard, Armbrecht and Gallego (2007) found in Colombia that a more diverse soil dwelling community of ants removed significantly more coffee berry borer (CBB) individuals, Hypothenemus hampei Ferrari (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), in shaded coffee than in unshaded lots. Similar studies in Mexico have demonstrated that shaded coffee agroecosystems at harboring a more diverse ant community regulate infestations (Larsen and Philpott 2010; Morris et al. 2015), regulation that is also associated with interspecific interactions among the more dominant ant species in those communities as Newson et al. (2021) demonstrated in agroforestry coffee productions in Puerto Rico. It is noteworthy that the beneficial role of ants on the CBB biocontrol has been demonstrated even during coffee postharvest process (Velez-Hoyos et al. 2006). In addition, studies in Jamaica demonstrated the beneficial role of shaded coffee, in this case associated with the pest reduction via biocontrol services provided by birds (Johnson et al. 2009). Vegetational diversification has also provided additional benefits in coffee pest management; Amaral et al. (2018) found that an increase on plant diversity in an organic coffee production was associated with an increase in predation of the coffee leaf miner Leucoptera coffeella (Guerin-Meneville) (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae) by wasps. The latter was also demonstrated in a coffee intercropping system, with different plant species, including avocado (Persea americana Mill), where plots intercropped with avocado showed a larger overall diversity of social wasps, usually associated with predation in coffee and other agroecosystems (Tomazella et al. 2018).

In a systematic review of the available biological control of the CBB, Escobar-Ramirez et al. (2019) found substantial evidence of successful cases in coffee agroforestry, where fungi, ants, parasitic wasps, birds, and nematodes can provide successful CBB biocontrol. However, landscape-scale studies are almost missing, indicating the need of more studies on CBC, also explaining a disagreement between coffee growers and researchers on the question if sustaining shaded crops reduce the incidence of main pests and diseases (Constantino et al. 2021; Jezeer and Verweij 2015). In this regard, there is no doubt that sustaining traditionally agroforestry systems would compensate production over biodiversity preservation if environmentally aware consumers are willing to accept premium prices for shade and/or socio-environmental certifications on a agroecosystem that contains as much diversity as forest habitats (Hardt et al. 2015; Perfecto et al. 1996, 2005).

Row crops among all extensive crops could be considered those in which large, monospecific, and dense patches of land are dedicated to one or very few cultivars of the same crop species, affecting more severely the complexity of the landscape. However, as mentioned earlier, changes in the way crop rows are cultivated, and conceived from a landscape perspective, have opened the chances for CBC. In the case of Argentina, soybean cultivation has been expanding dramatically up to the point that by the beginning of the 2010s, soybean was using more than half of the cultivated land in the country (Aizen et al. 2009), and the latter at the expense of other crops and non-cultivated areas (Gonzalez et al. 2017). Gonzalez et al. (2017) demonstrated that fragments of natural vegetation were important in providing CBC against the stink bug Dichelops furcatus (F.) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in soybean, whose populations were lowest when closer to surrounding forests. The latter authors also concluded that forest amount and landscape scale are more important than proximity to the forest, with the purpose of providing CBC against the stink bugs in soybean.

Following the same idea of forest remnants and its effects on agroecosystem diversity, in Colombia, Rivera-Pedroza et al. (2019) found that species richness of ants and birds was decreasing from vegetation strips in sugarcane, with predatory functional groups with important implications for biological control services on key sugarcane pests, indicating that conserving natural vegetation strips is important in promoting CBC in this agroecosystem. In this regard, the sugarcane stem borers Diatraea spp. are considered the most economically important pest in Colombia, where biological control via releases of egg and larval parasitoids are main tools in pest management. However, one of the most important larval parasitoids is the wild tachinid Genea jaynesi (Aldrich) (Diptera: Tachinidae) (Sarmiento-Naizaque et al. 2021; Vargas et al. 2018), whose efforts to mass rearing have been futile, suggesting the need to focus on conservation of vegetation strips to increase G. jaynesi biocontrol services.

New technologies on industrialized agriculture and CBC

It is understood that practices that enhance both the crop and the surrounding environment by habitat management and/or cultural practices benefit CBC. On the other hand, the use of insecticides, either chemical or biological, is recognized as detrimental to non-target organisms and among them NE. However, Torres and Bueno (2018) discussing two major crop commodities in Brazil, soybean and cotton, which are highly dependent on chemical control of pests, suggest that NE and selective insecticides could be effectively combined to manage pest populations. They also discuss that more focus is needed in understanding the interaction of insecticide compounds and NE, and different avenues of interactions either direct or indirect exposure, considering in addition the chances of underlying physiological selectivity that can be enhanced by continuous exposure of some NE to pesticides. In this regard, there are some examples in predators such as green lacewings and lady beetles exhibiting resistance to several modes of action (Abbas et al. 2014; Costa et al. 2018). The above mentioned in a perspective that chemical selectivity, spraying techniques, and IPM principles of adopting economic thresholds applications can promote CBC.

It could be argued that the idea of CBC does not necessarily imply organic production or agroecological approaches. A scenario of industrialized agriculture where insecticides and genetically modified plants, among other new technologies, is articulated in an IPM approach could be leaving room, and even facilitating CBC, without necessarily meaning that these systems are transitioning towards an organic system. In Brazil, major row crops, composed of Bt transformed plants such as soybean, cotton, corn, and lately sugarcane, are widely planted across extensive areas. In this regard, Luz et al. (2018) found that NE of Helicoverpa armigera (Hubner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) were causing up to 41% of larval parasitism on refuge areas of cotton not subject to insecticide applications. The latter point out the structured refuge areas of these Bt crops as source of NE and promote CBC in these genetically modified agroecosystems.

Row crops can also become more prone to CBC when transitioning to a more environmentally friendly organic farming, and to a school denominated biodynamic farming, more closely related to traditional farming, where the idea, beyond adding organic materials in the system (e.g., nutrients, insecticides, and fungicides), is stimulating and regulating the nutrients and energy cycles, thereby improving soil and crop quality (Robusti et al. 2020), and additionally more traditional CBC. Brazil is considered the greatest supplier of soybean in the world, and more conventional farmers are making the switch from conventional agriculture to organic/biodynamic soybean, where higher organic trading prices can cover higher costs and provide extra profitability besides environmental revenues in general (Robusti et al. 2020).

Principal organisms associated with conservation in the Neotropical region

Several countries in the Neotropical region are considered megadiverse zones in the world for several taxa (Morrone 2014; Rodrigues et al. 2003). This trend is observed in arthropods, where several countries in the Neotropical region are considered megadiverse for some groups such as coleopterans or lepidopterans (García-Robledo et al. 2020). The megadiversity present in the Neotropical region has worked to relevant purposes such as defining protected areas (De Carvalho et al. 2017), while some plant compounds have strongly contributed to the development of pharmaceutics and medicine (Desmarchelier 2010). However, other potential applied uses of local diversity in other field like the biological control remain poorly understood (Souza et al. 2019).

As mentioned previously, CBC promotes the utilization of local beneficial fauna by different practices, increasing the diversity and abundance of groups like predators and parasitoids. Considering the megadiversity of Neotropical region, the implementation of CBC could be a practice widely used (Souza et al. 2019); however, it has received little attention when compared to other types of biological control such as the classical or the augmentation. One of the possible causes preventing the implementation of CBC programs could be the lack of knowledge regarding the biology and ecology of native NE. Therefore, it is necessary to provide updated information regarding to the use and current knowledge of entomophagous arthropods and its use in CBC in the region.

Given the necessity of exploring the local diversity, the aim of this section was to evaluate the current knowledge of the use of entomophagous NE (predators and parasitoids) in the Neotropical region, focusing on Central and South America between 2010 and 2022. To do this, we used two databases, namely Scopus and Scielo. In the first selected database, we focused on the empirical papers published by Central and South American countries. Here, we filtered the search by selecting the production from the countries included in the Neotropical region and the time lapse selected. The algorithm search words are displayed in supplementary material (Appendices 1 to 4). In the case of the Scielo library, we filtered the search to the timespan selected. Once the dataset was obtained, we filtered results not related to our search parameter (other topics), those which were made in other countries than those belonging to the Neotropical region, reviews, and book chapter. Given the database compatibility and the higher number of papers when compared to the other database, data coming from Scopus was analyzed with the software Bibliometrix (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017). Data was analyzed considering the number of papers published per year, most productive countries, and the cooperative working network between authors. In a second stage, we combined the papers extracted from both database and classified them according to the functional group (predators or parasitoids) and taxonomic category in the case of predators, considering that most studies on parasitoids were focused on hymenopterans.

Bibliographic production about CBC in Neotropical countries

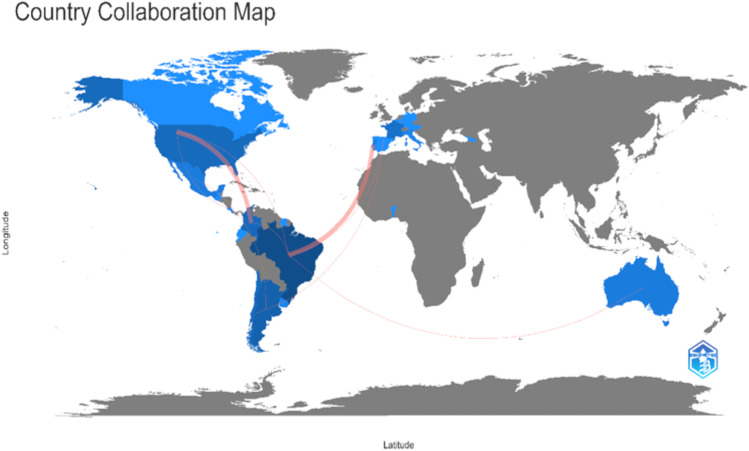

When analyzing the bibliometric production from the Scopus database, we found that the bibliographic production showed a slight but oscillating increase in the evaluated period (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the year 2021 recorded the highest productivity in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. When evaluating the production per country, we found that Brazil published the highest number of papers, followed by Argentina and Chile, while other countries showed a similar productivity. Interestingly, the USA showed a high productivity too, despite being excluded in our analysis. We also found a high cooperation between Brazil and European countries as well as with the USA, and between Argentina and Colombia and the USA. Some other connections are observed between some South American countries and other regions such as Africa and Oceania (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Annual scientific production retrieved from the database Scopus between 2010 and 2022 about predators and parasitoids from the Neotropical region and their role as conservative biological control agents. Plot was generated using the R package bibliometrix (see text for details)

Fig. 3.

Country production and collaboration map. Darkest colors indicate a higher number of published papers, while red lines indicate scientific cooperation between different countries in the Neotropics. Plot was generated using the R package bibliometrix (see text for details)

Bibliographic production in relation to different functional and taxonomic groups of NE in the Neotropical region

When evaluating the scientific productivity in the different functional groups, we found that most of the studies included predators as main target followed by parasitoids, while in a lesser degree, some studies included in the category “mix” included both predators and parasitoids (Fig. 4A). When analyzing predators in detail, we found that studies focused on predatory insects were by far more common than the remaining groups, which included arachnids and vertebrates. In the category “mix,” we included studies that comprised both arthropods and vertebrates.

Fig. 4.

Number of published papers according to A functional groups and B taxonomic group of predators in the Neotropics. The category mix includes studies which included more than one functional or taxonomic group belonging to a different category. Plot was generated using the R package bibliometrix (see text for details. Original data can be requested to the author Luis Fernando Garcia)

Parasitoids are widely used in biological control given their high specificity towards certain pest groups and host-killing behavior (Wang et at. 2019). In our analysis, we found that several studies were focused on hymenopterans belonging to different families, while some others included tachinid flies. In the case of parasitoids, studies included both diversity and applied biological control studies (see Appendix 1), attacking pests as important as fruit flies, or protecting crops such as coffee. Interestingly, new studies in poorly known group such as tachinids shed light on the importance of exploring the local diversity, especially when considering the relevance of tachinid flies as biological control agents (Grenier 1988).

In the case of predators, most studies focused on some relatively specialist (i.e., aphidophagous) such as chrysopids, coccinelids, and syrphids, that have been traditionally studied (New 1975; Obrycki et al. 2009; Dunn et al. 2020). In contrast, studies on generalist predators are more scarce, although some groups such as ants and vespid wasps have been studied as native NE of relevant pests, including Spodoptera frugiperda and Hypothenemus hampei (Armbrecht and Gallego 2007; Montefusco et al. 2017). In the particular case of ants, its use in CBC programs can be controversial since some groups can offer some protection to local pests (Carabalí-Banguero et al. 2013).

According to our analysis, arachnids (after arthropods as a whole) were the second more studied group. Acari were the most studied arachnid group followed by spiders. Studies about Acari and CBC in our analyses were focused on direct evidence of pest control, as well as habitat manipulation. In the case of spiders, studies were focused on diversity and abundance analyses in agroecosystems, as well as observations of feeding behavior against some local pests. Although the studies focused on spiders are comparatively low, the fact that this group is being considered in CBC in the Neotropics is important. Recent studies show that despite their generalist habits, spiders are effective biological control agents because of their dominance on crops as well as their direct and indirect effects against pest populations (Michalko et al. 2019), turning them into a promising group for future CBC programs in the Neotropical region.

Vertebrates have been often neglected as CBC agents; however, recent evidence shows that several groups such as amphibians, birds, and mammals provide an important pest control service in crops (Riccucci and Lanza 2014; Khatiwada et al. 2016; Garcia et al. 2020). In our analysis, we found that in the Neotropics, most studies have been focused on pest control provided by birds and mammals. In the case of birds, their role as biological control agents has been evaluated mainly against insect pests, but also against rodents which can be both agricultural and sanitary pests. The habitat complexity has shown to have a positive effect on birds when controlling pests in the Neotropics (Olmos-Moya et al. 2022). In the case of mammals, most of the studies were focused on insectivorous bats that have an important role as CBC agents in Neotropical crops; however, recent evidence has shown that other groups such as armadillos might play an important role when controlling pests which are hard to eradicate such as Acromyrmex ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) (Elizalde and Superina 2019).

Concluding remarks

From a historical perspective and looking into the future, CBC arises as an alternative to conventional pest management practices (e.g., chemical pesticides), with the goal to decrease negative impacts on the ecosystem. However, as its implementation on pest management practices does not necessarily provide rapid and full regulation of pests, there must be an articulation to integrated and ecological pest management programs. In the case of small-scale agriculture, the use of CBC techniques in Latin America is highly associated with the practice of Agroecology, and the diversification of the landscape on these rural areas is linked to the genetic resources available in each region. In the case of the industrialized agriculture, there has been progress on its adoption, usually arguing its benefits but lacking scientific documentation. Agribusiness companies and private research institutes would surely be stimulated by pressure from the market to implement less environmentally harsh practices; however, the latter could not have the extent to stimulate farmers associations, aside from those already environmental conscious, and private research institutes to promote rigorous documentation and information on the matter, beyond internal reports or institutional magazines, indicating the need for further collaboration and partnerships between industry and the academia to promote better understanding and adoption of CBC.

A general review of the CBC cases in the Neotropical region allows the conclusion of great need of appropriate documentation of cases; a great deal of information referenced in this review has come from extension manuals and internal publications, not often associated with scientific periodical publications. The latter agrees to Luliano and Gratto (2020) when suggested a bias on the CBC research towards the developed world, with few exceptions available on the tropics (Wyckhuys et al. 2013) and specifically in the Neotropical region (Peñalver-Cruz et al. 2019). Efforts directed toward the documentation of the examples and analysis of the CBC in the region will surely benefit the understanding of the dynamics of the CBC under these conditions, complementing the body of knowledge already obtained in the temperate regions.

In relation to the more prevalent fauna associated to CBC in the Neotropical region, although our analysis is limited to two databases, it provides some interesting trends. For example, although the scientific production has shown an oscillating pattern in the evaluated period, we recorded an increase between the last 2 years, suggesting the local increase on documentation on entomophagous arthropods. As mentioned previously, many countries from the Neotropical region do not report research on the evaluated topic or when it is reported results from cooperation with North American or European countries. Given the local needs and further prospects, it would be important to increase cooperation between South Central American and the Caribbean. Although studies regarding NE focus on predators, only some groups, mainly specialists, have been evaluated. In complement, further research should focus in new native and promising predators such as ants, wasps, spiders, and vertebrates. The same trend therefore should be applied to local parasitoids, which are also promising but poorly known such as tachinid flies, representing a challenge in general for biological control researchers and practitioners when it comes to have on taxonomic identification, which at the same time highlights the great need of more efforts on biodiversity surveys and taxonomic studies to help in the general scope of CBC impact. Additionally, more efforts are necessary on determining the type of modifications in the agricultural landscapes to enhance beneficial fauna populations, aiming the determination of requirements on natural vegetation type (e.g., quantity and quality) and analyzing the effects of implementing multiple crops (intercrops, mixed crops, crops in strips, relay, green manures, among others), especially in industrialized crops.

Overall, contributions and advances in CBC in the Neotropical region will be linked to the increase in local research and development in those countries where no research in this field has been made. In addition, given the local needs of increasing knowledge of CBC in Latin American and Caribbean countries, which are highly dependent on agriculture, stronger efforts should focus on increase local research between different countries from this region. It could be argued that research on CBC in North America and Europe has a long history and many documented advances in comparison to the Neotropical region where there is a lack of studies related to agroecosystem management seeking pest suppression. The latter has promoted the discussion within the Neotropical Regional Section of the International Organization for Biological Control (IOBC-NTRS) about the need to integrate researchers and promote advances in this area. As a new development and an important new avenue of advancing the study of CBC in the region, the working group on Conservation Biological Control in the Neotropical Region (WGCBC) was created and launched in 2022 with the purpose of enhancing the production of knowledge of the influence of native or implanted biodiversity and agricultural practices on habitat management that promote biological control in addition to other ecosystem services in agricultural areas. According to the general guidelines of the IOBC organization, working groups should allow IOBC members (and others) to focus on specific topics of interest in the discipline to provide scientific progress and a sense of community among working group members. Thus, the conformation of this new group has as a main objective to evaluate and disseminate knowledge about research and results on CBC in the Neotropical region, from which this review is considered an initial step in this direction.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

General overview and proposal: GV; Conceptualization: GV, LFR, LFG and SMJ; Writing—original draft preparation: GV, LFR, LFG and SMJ; Analysis on bibliometric production: LFG; Writing—review and editing: GV, LFR, LFG and SMJ.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

German Vargas, Email: gavargas@cenicana.org.

Leonardo F. Rivera-Pedroza, Email: lfrivera@cenicana.org

Luis F. García, Email: luizf.garciah@gmail.com

Simone Mundstock Jahnke, Email: mundstock.jahnke@ufrgs.br.

References

- Abbas N, Mansoor MM, Shad SA, Pathan AK, Waheed A, Ejaz M, Razaq M, Zulfiqar Fitness cost and realized heritability of resistance to spinosad in Chrysoperla carnea (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) Bull Entomol Res. 2014;104:707–715. doi: 10.1017/S0007485314000522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adaime R, Lima AL, Sousa MSM. Controle biológico conservativo de moscas-das-frutas na Amazônia brasileira. Innov Agron. 2018;64:47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar-Menezes EL, Silva AC. Plantas atrativas para inimigos naturais e sua contribuição no controle biológico de pragas agrícolas. Rio de Janeiro: Embrapa Agrobiologia; 2011. p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Aizen MA, Garibaldi LA, Dondo M. Expansión de la soja y diversidad de la agricultura argentina. Ecol Austral. 2009;19:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Aldana JA, Calvache H, Escobar B, Castro HB. Las plantas arvenses benéficas dentro de un programa de manejo integrado de Stenoma cecropia meyrick, en palma de aceite. Palmas. 1997;18:11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Aldana JA, Calvache H, Daza CA. Alternativas para siembra de plantas nectariferas. Palmas. 2004;25:194–204. [Google Scholar]

- Alhadidi SN, Griffin JN, Fowler MS. Natural enemy composition rather than richness determines pest suppression. Biocontrol. 2018;63:575–584. doi: 10.1007/s10526-018-9870-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altieri M. Agroecologia: bases científicas para uma agricultura sustentável. AS-PTA: Expressão Popular; 1989. p. 400. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri M, Nicholls C (2012) Agroecología: única esperanza para la soberanía alimentaria y la resiliencia socioecológica. Una contribución a las discusiones de Rio+20 sobre temas en la interface del hambre, la agricultura, y la justicia ambiental y social. SOCLA, junio 2012. p 21

- Amaral DS, Venzon M, Duarte MVA, Sousa FF, Pallini A, Hardwood JD. Non-crop vegetation associated with chili pepper agroecosystems promote the abundance and survival of aphid predators. Biol Control. 2013;64:338–346. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2012.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DS, Venzon M, Pallini A, Lima PC, DeSouza O. A diversificação da vegetação reduz o ataque do bicho-mineiro-do-cafeeiro Leucoptera coffeella (Guérin-mèneville) (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae)? Neotrop Entomol. 2018;39:543–548. doi: 10.1590/S1519-566X2010000400012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aria M, Cuccurullo C. bibliometrix: an R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J Informetr. 2017;11:959–975. doi: 10.1016/J.JOI.2017.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armbrecht I, Gallego MC. Testing ant predation on the coffee berry borer in shaded and sun coffee plantations in Colombia. Entomol Exp Appl. 2007;124:261–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2007.00574.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa P. Conservation biological control. Londres, UK: Academic press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa P, Benrey B. The influence of plants on insect parasitoids: implications for conservation biological control. In: Barbosa P, editor. Conservation Biological Control. Academic Press; 1998. pp. 55–82. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa P, Wratten SD. Influence of plants on invertebrate predators: implications to conservation biological control. In: Barbosa P, editor. Conservation Biological Control. Academic Press; 1998. pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Becker C, Desneux N, Monticelli L, Fernandez X, Michel T, Lavoir AV. Effects of abiotic factors on HIPV-mediated interactions between plants and parasitoids. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:342982. doi: 10.1155/2015/342982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg GS, Cook SM, Dye R, Ferrante M, Franck P, Lavigne C, Lövei GL, Mansion-Vaquie A, Pell JK, Petit S. A functional overview of conservation biological control. Crop Prot. 2017;97:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2016.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardes MFF, Pazin M, Pereira LC, Dorta DJ (2015) Impact of pesticides on environmental and human health. In Toxicology studies—cells, drugs and environment, IntechOpen: London, UK, pp. 195–233

- Boedeker W, Watts M, Clausing P, Marquez E. The global distribution of acute unintentional pesticide poisoning: estimations based on a systematic review. BMC Publ Health. 2020;2020:1875. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09939-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Brasil. Lei nº 12.651, de 25 de maio de 2012. Código Florestal Brasileiro. Brasilia, Distrito Federal, 2012. Available at: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2012/lei/l12651.htm. Accessed 23 Nov 2022

- Bruinsma J (2003) World agriculture: towards 2015/2030 — an FAO perspective. Earthscan, London and FAO, Rome

- Bustillo-Pardey AE (2014) Manejo de insectos-plaga de la palma de aceite con énfasis en el control biológico y su relación con el cambio climático. Palmas:66–77

- Cabral-Antúnez CC, Romero GR, López VAG (2020) Biological control in Paraguay. In: Van Lenteren J, Bueno VHP, Luna MG, Colmenarez YC. Biological control in Latin America and in Caribbean: its rich history and bright future. CAB International. pp 354–368

- Calvache H. Manejo integrado de plagas de la palma de aceite. Revista Palmas. 1995;16:255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Carabalí-Banguero DJ, Wyckhuys KAG, Montoya-Lerma J, et al. Do additional sugar sources affect the degree of attendance of Dysmicoccus brevipes by the fire ant Solenopsis geminata? Entomol Exp Appl. 2013;148:65–73. doi: 10.1111/EEA.12076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro AR, SÁ, Bertruy RP (orgs.) (2009) Jardins Históricos Brasileiros e Mexicanos. Recife: Ed. UFPE, 2009.

- Carvalho FP. Pesticides, environment, and food safety. Food Energy Secur. 2017;6:48–60. doi: 10.1002/fes3.108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos M, Martínez M, Duarte DLA, Baños LHL, Sánchez A. Asociación áfidos-parasitoides em cultivos hortículas. Rev Prot Veg. 2009;24:180–183. [Google Scholar]

- Chapling-Kramer R, Kremer C. Pest control experiments show benefits of complexity at landscape and local scales. Ecol Appl. 2012;22:1936–1948. doi: 10.1890/11-1844.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirinos DT, Castro R, Cun J, Castro J, Peñarrieta S, Solis L, Geraud F. Los insecticidas y el control de plagas agrícolas: la magnitud de su uso en cultivos de algunas provincias de Ecuador. Cienc Tecnol Agrop. 2020;21:e1276. [Google Scholar]

- Colmenarez YC, Corniani N, Jahnke SM, Sampaio MV, Vásquez C (2018) Use of parasitoids as a biocontrol agent in the neotropical region: challenges and potential. In: IntechOpen (ed.), Hymenopteran wasps - the parasitoids. London, United Kingdom: IntechOpen. pp 1–23. 10.5772/intechopen.80720

- Constantino LM, Rendon JR, Cuesta G, Medina RD, Benavides P. Dinámica poblacional, dispersión y colonización de la broca del café Hypothenemus hampei en Colombia. Cenicafe. 2021;72:23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PMG, Torres JB, Rondelli VM, Lira R. Field-evolved resistance to λ-cyhalothrin in the lady beetle Eriopis connexa. Bull Entomol Res. 2018;108:380–387. doi: 10.1017/S0007485317000888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva GS, Jahnke SM, Ferreira MLG. Hymenoptera parasitoids in protected area of Atlantic Forest biomes and organic rice field: 2 compared assemblages. Rev Colomb Entomol. 2016;42:110–117. doi: 10.25100/socolen.v42i2.6680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva GS, Jahnke SM, Johnson N. Riparian forest fragments in rice fields under different management: differences on hymenopteran parasitoids diversity. Braz J Biol. 2019;79:1–11. doi: 10.1590/1519-6984.194760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daam MA, Chelinho S, Niemeyer JC, Owojori OJ, De Silva P, Sousa JP, van Gestel C, Römbke J. Environmental risk assessment of pesticides in tropical terrestrial ecosystems: Test procedures, current status and future perspectives. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;181:534–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carvalho DL, Sousa-Neves T, Cerqueira PV, et al. (2017) Delimiting priority areas for the conservation of endemic and threatened Neotropical birds using a niche-based gap analysis. PLoS One 1210.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0171838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Del Puerto-Rodríguez AM, Suárez-Tamayo S, Palacio-Estrada DE (2014) Efectos de los plaguicidas sobre el ambiente y la salud. Rev Cub Hig Epidemiol 52(3)

- Desmarchelier C. Neotropics and natural ingredients for pharmaceuticals: why isn’t South American biodiversity on the crest of the wave? Phyther Res. 2010;24:791–799. doi: 10.1002/PTR.3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz MF, Ramírez A, Poveda K. Efficiency of different egg parasitoids and increased floral diversity for the biological control of noctuid pests. Biol Control. 2012;60:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2011.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz S, Pascual U, Stenseke M, Martín-López, et al. Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Science. 2018;359:270–272. doi: 10.1126/science.aap8826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn L, Lequerica M, Reid CR, Latty T. Dual ecosystem services of syrphid flies (Diptera: Syrphidae): pollinators and biological control agents. Pest Manag Sci. 2020;76:1973–1979. doi: 10.1002/PS.5807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan P, Dicks LV, Hokkanen H, Stenberg JA. Delivering integrated pest and pollinator management (IPPM) Trends Plant Sci. 2020;25:577–589. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2020.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehler L (1998) Conservation biological control: past, present, and future. In: Conservation biological control. Academic Press. pp. 1–8

- Elizalde L, Superina M. Complementary effects of different predators of leaf-cutting ants: Implications for biological control. Biol Control. 2019;128:111–117. doi: 10.1016/J.BIOCONTROL.2018.09.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Ramirez S, Grass I, Armbrecht I, Tscharntke T. Biological control of the coffee berry borer: main natural enemies, control success, and landscape influence. Biol Control. 2019;136:103992. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fedepalma (2016) Paisaje Palmero Biodiverso. Proyecto GEF/BID. Unidad Coordinadora del Proyecto. Available at: https://web.fedepalma.org/sites/default/files/files/2016-05%20Si%cc%81ntesis%20Proyecto%20GEF%20(1).pdf. Accessed 19 Nov 2022

- Fernández DE, Cichón LI, Sánchez EE, Garrido SA, Cecilia GC. Effect of different cover crops on the presence of arthropods in an organic apple (Malus domestica Borkh) Orchard. J Sustainable Agric. 2008;32:197–211. doi: 10.1080/10440040802170624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira MLG, Jahnke SM, Morais RM, Da Silva GSD. Diversidad de insectos depredadores en área orizícola orgánica y de conservación en Viamão, RS, Brasil. Rev Colomb Entomol. 2014;40:120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Frank BJR, Yamaki HA (2018) paisagem vernacular segundo perspectivas de Sauer, Hoskins E Jackson. Caminhos de Geografia Uberlândia - MG v. 19, n. 65 Março/2018 p. 245–256

- Gaimari SD, Quintero EM, Kondo T. First report of Syneura cocciphila (Conquillett, 1895) (Diptera: Phoridae), as a predator of the fluted scale Crypticerya multicicatrices Jondo and Uhruh, 2009 (Hemiptera: Monophlebidae) Boletín Del Museo De Entomología De La Universidad Del Valle. 2012;13:26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia K, Olimpi EM, Karp DS, Gonthier DJ. The good, the bad, and the risky: can birds be incorporated as biological control agents into integrated pest management programs? J Integr Pest Manag. 2020;11:11–12. doi: 10.1093/JIPM/PMAA009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Cancino MD, Gonzáles-Cabrera J, Sánches- M-C, Gonzáles JA, Arredondo-Bernal HC. Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura) (Diptera: Drosophilidae) em Colima, México. Sw Entomol. 2015;40:855–858. [Google Scholar]

- García-Robledo C, Kuprewicz EK, Baer CS, et al. The Erwin equation of biodiversity: from little steps to quantum leaps in the discovery of tropical insect diversity. Biotropica. 2020;52:590–597. doi: 10.1111/BTP.12811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gliessman SR. Agroecology: ecological processes in sustainable agriculture. Chelsca, Michigan: Ann Arbor Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gliessman SR (2001) Agroecologia: processos ecológicos em agricultura sustentável. 2ªedição. Porto Alegre: Ed. UFRGS, 653 p

- Gómez-Jiménez MI (2018) Parasitoides como controladores de Erinnyis ello. In: Cotes, A. M. (ed.) Control Biologico de fitopatógenso, insectos y ácaros. Volumen 1. Agentes de control biológico. Editorial Agrosavia, Bogotá, Colombia, pp 507–509

- González E, Salvo A, Valladares G. Arthropod communities and biological control in soybean fields: Forest cover at landscape scale is more influential than forest proximity. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2017;239:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2017.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grenier S. (1988) Applied biological control with Tachinid flies (Diptera, Tachinidae): a review. Anzeiger Für Schädlingskunde, Pflanzenschutz, Umweltschutz. 1988;613(61):49–56. doi: 10.1007/BF01906254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haggar J, Casanoves F, Cerda R, Cerretelli S, Gonzalez-Mollinedo LG, et al. Shade and agronomic intensification in coffee agroforestry systems: trade-off or synergy? Front Sustainable Food Sys. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.645958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt E, Borgomeo E, dos Santos RF, Pinto LFG, Metzger P, Sparovek G. Does certification improve biodiversity conservation in Brazilian coffee farms? For Ecol Manage. 2015;357:181–194. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2015.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harterreiten-Souza ES, Togni PHB, Pires CSS, Sujii ER. The role of integrating agroforestry and vegetable planting in structuring communities of herbivorous insects and their natural enemies in the Neotropical region. Agroforest Syst. 2014;88:205–219. doi: 10.1007/s10457-013-9666-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- HeimpeL GE, Mills NJ (2017) Biological control: ecology and applications. Cambridge. 380p

- Hernandez-Mahecha LM, Manzano MR, Guzmán YC, Buhl PN. Parasitoids of Prodiplosis longifilia Gagné (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) and other Cecidomyiidae species in Colombia. Acta Agron. 2018;67:184–191. doi: 10.15446/acag.v67n1.62712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino AT, Bortolotto OC, Hata FT, Ventura MU, Menezes-Júnior AO. Effect of pigeon pea intercropping or shading with leucaena plants on the occurrence of the coffee leaf miner and on its predation by wasps in organic coffee plantings. Ciência Rural, Santa Maria. 2018;48:e20160863. doi: 10.1590/0103-8478cr20160863. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huffaker CB, Messenger PS. Theory and practice of biological control. Nueva York: Academic Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JB. Discovering the vernacular landscape. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]