Abstract

Human alphapapillomaviruses (αHPV) infect genital mucosa, and a high-risk subset is a necessary cause of cervical cancer. Licensed L1 virus-like particle (VLP) vaccines offer immunity against the nine most common αHPV associated with cervical cancer and genital warts. However, vaccination with an αHPV L2-based multimer vaccine, α11–88x5, protected mice and rabbits from vaginal and skin challenge with diverse αHPV types. While generally clinically inapparent, human betapapillomaviruses (βHPV) are possibly associated with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) in epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV) and immunocompromised patients. Here we show that α11–88x5 vaccination protected wild type and EV model mice against HPV5 challenge. Passive transfer of antiserum conferred protection independently of Fc receptors (FcR) or Gr-1+ phagocytes. Antisera demonstrated robust antibody titers against ten βHPV by L1/L2 VLP ELISA and neutralized and protected against challenge by 3 additional βHPV (HPV49/76/96). Thus, unlike the licensed vaccines, α11-88x5 vaccination elicits broad immunity against αHPV and βHPV.

Keywords: Human papillomaviruses, virus-like particle, L1 capsid protein, preventive vaccination, multimer, L2 capsid protein, epidermodysplasia verruciformis, HPV, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, Fc receptor

Graphical Abstract

2. INTRODUCTION

There are over 200 recognized human papillomavirus (HPV) genotypes defined by an L1 nucleotide sequence differing by >10% to the closest known type (https://pave.niaid.nih.gov/explore/taxonomy/taxonomy_concept). They are classified within genera (α, β, γ, μ, etc), which share >60% nucleotide sequence identity in the L1 ORF, and therein species (α9, α7 etc) share between 71% and 89% L1 nucleotide identity (Bernard et al., 2010; de Villiers et al., 2004). The αHPV genotypes are predominantly sexually transmitted, infect genital, oral or anal mucosa, and exhibit differing transforming potential (zur Hausen, 2002). A dozen αHPV defined as ‘high-risk’ are a necessary, but not sufficient cause of cervical cancer. HPV16 causes 50% of cervical cancers, and 90% of other HPV-related anogenital and oropharyngeal cancers (Plummer et al., 2016). Additional genotypes within species α9 (e.g. HPV31, 33, 52, 58), and α7 (e.g. HPV18, 39, 45) are drivers of the other half of cervical cancer cases, along with 11 additional αHPV identified as ‘likely carcinogenic’ because they were found as single infections in invasive cervical cancer cases (Geraets et al., 2012) (Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans IARC, 1995). ‘Low risk’ αHPV cause benign genital warts, most commonly HPV6 and 11 (de Villiers et al., 2004). Preventive vaccines have been licensed which target between two αHPV, i.e., HPV16 and 18 by Cervarix, to 9 types, i.e. HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 by Gardasil®9. These commercial vaccines utilize L1 virus-like particles derived from targeted genotypes formulated on an alum-based adjuvant (and monophosphoryl lipid A for Cervarix), trigger high titers of neutralizing antibodies and provide durable, type-restricted immunity and ultimately prevent cervical cancer (Falcaro et al., 2021; Kjaer et al., 2021; Roden and Stern, 2018).

The >50 known βHPV infect skin and are biologically and immunologically distinct from the αHPV (Rollison et al., 2019). βHPV infections occur throughout the lifespan, likely via fomite (non-sexual) transmission. Most βHPV infections are subclinical, but they can produce benign flat warts (Orth et al., 1978). While there is evidence supporting a co-carcinogen role for certain βHPV genotypes with UV light in causing cutaneous squamous skin cancer (CSCC) in certain high risk cohorts, the causal link remains controversial (Bouwes Bavinck et al., 2017; Hasche et al., 2018; Jensen et al., 2000; Strickley et al., 2019). Indeed, CSCC is more common in regions with high sun exposure and lighter-skinned individuals (Lomas et al., 2012). The age-adjusted incidence among White individuals is 100–150 per 100,000 persons per year (Alam and Ratner, 2001); it can be 100-fold higher in transplant patients in association with expanding and recalcitrant skin warts (Bouwes Bavinck et al., 2017; Jensen et al., 2000).

Association of CSCC with βHPV was first described in epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV) (McLaughlin-Drubin, 2015; Nindl et al., 2007; Orth et al., 1978; Tommasino, 2017), a rare autosomal recessive genetic disease associated with homozygous loss-of-function TMC6, TMC8 (also known as EVER1, EVER2) or CIB1 germline mutations (de Jong et al., 2018a). The products of these three genes normally form a complex proposed to govern keratinocyte-intrinsic immunity to βHPV (de Jong et al., 2018b; Wu et al., 2020). EV patients exhibit apparently normal leukocyte development and control of other infectious agents, including HPV infections outside β genus. However, βHPV infections, like HPV5, 8, 20, 24, 36, 38, 49, 76, 80, 92, 96, produce disfiguring flat warts covering EV patients, that prematurely progress to CSCC in sun-exposed areas (Przybyszewska et al., 2017). UV exposure damages keratinocyte genomic DNA, and βHPV infection can compromise its repair (graphical abstract) (Wallace et al., 2012, 2015). βHPV episomes and early gene expression can readily be detected in the precursor lesions, actinic keratosis, and in well-differentiated keratinizing SCC (Hasche et al., 2018). However, unlike oncogenic αHPV, continued expression of βHPV may not be required in poorly differentiated non-keratinizing SCC, thus a hit-and-run mechanism has been proposed (Arroyo Muhr et al., 2021). While controversial, this hypothesis is supported by animal studies (Campo et al., 1994; Dorfer et al., 2021; Viarisio et al., 2011; Viarisio et al., 2018).

Based upon this hypothesis, vaccination against βHPV infection has a potential to prevent these CSCC (and flat warts and actinic keratoses) (Hasche et al., 2018; Rollison et al., 2019). Unfortunately, no commercial vaccine targets βHPV. Since there are >50 βHPV with no clear subset linked to CSCC, genotype-specific L1 VLP vaccination is likely impractical.

A single antigen vaccine that broadly protects against all oncogenic HPV (α and β) has the potential to reduce the burden of anogenital, oropharyngeal and cutaneous squamous cell cancers (Roden and Stern, 2018). Furthermore, its production in E. coli could reduce manufacturing costs, which is important as financial barriers are a major impediment to global HPV vaccine implementation and the eradication of cervical cancer. We developed a single fusion protein that incorporates a broadly cross-protective epitope of L2 (defined by residues 11–88) (Jagu et al., 2013) of five αHPV (graphical abstract), specifically HPV6, 16, 18, 31, and 39. This L2 multimer (α11-88x5) can be produced under cGMP in bacteria, and when formulated with alum and administered intramuscularly (i.m.), it induces robust levels of broadly neutralizing antibodies. Three immunizations with α11-88x5, or a single passive transfer of α11-88x5 antiserum, protected mice against challenge with diverse αHPV pseudovirions (PsV) that deliver a luciferase reporter (Jagu et al., 2013). Likewise, vaccination of domestic rabbits, or passive transfer of α11-88x5 antiserum, protected them from papilloma after skin challenge with cottontail rabbit papillomavirus (CRPV) and αHPV quazivirions (QV) that deliver the CRPV genome (Kalnin et al., 2017). Although the α11-88x5 contains L2 amino acid sequences from only αHPV species, this region is highly conserved with the βHPV (Figure 1A,B), suggesting that cross-protection is possible. Indeed, antisera to α11-88x8 cross-neutralized 34 divergent HPV types, including all five of the βHPV PsV that were tested in vitro (Kwak et al., 2014). Here we explore the potential of the L2 multimer vaccine α11-88x5 to prevent βHPV infection of wild type and EV model mice, and the role of antibody, Fc receptors and Gr-1+ marophages/neutrophils in protection.

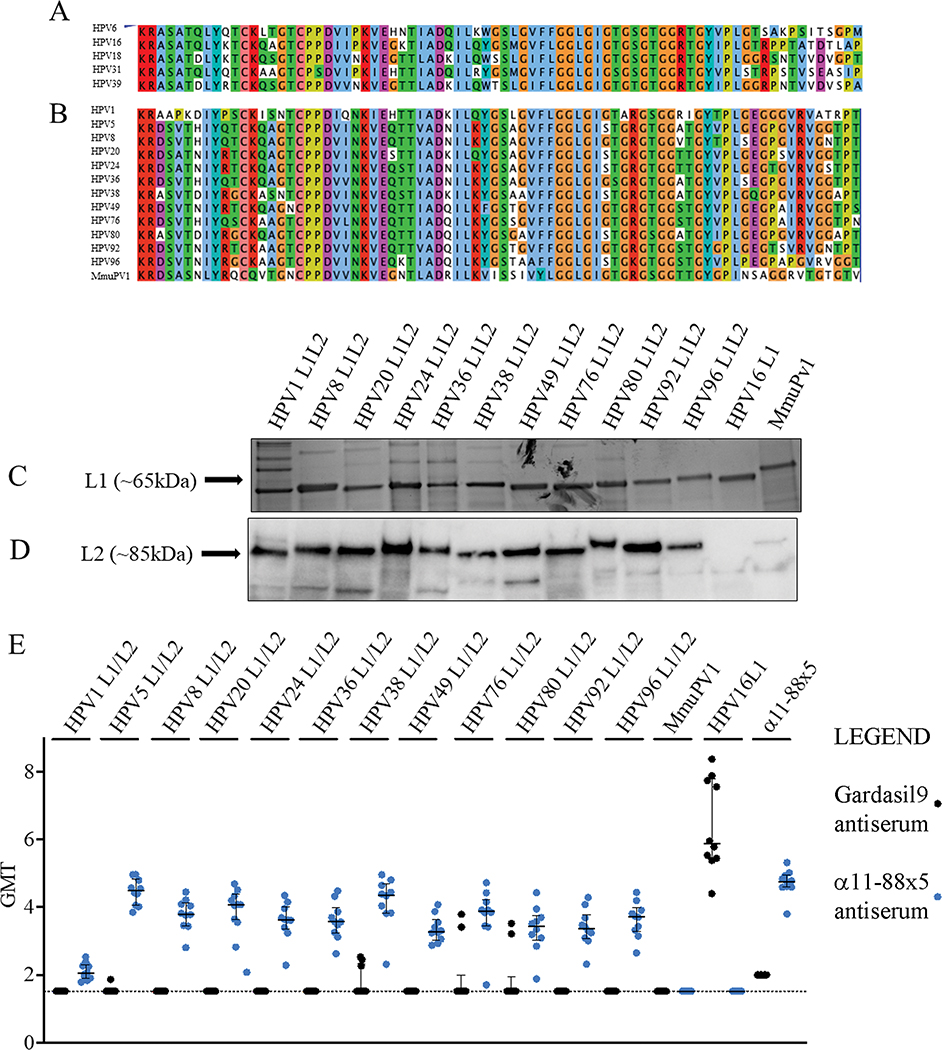

Figure 1. Design of α11-88x5 fusion protein vaccine and antibody responses elicited to L1/L2 VLP.

(A) Sequence alignment of five HPV types included in the α11-88x5 vaccine. (B) Sequence alignment of the papillomavirus types the multimer vaccine was assessed against in the current study. Sequence alignments were generated using Jalview 2.11.1.7. (http://www.jalview.org/). Color scheme of amino acids corresponds to a default ClustalX setting. When the percentage threshold of amino acid per column was met, coloring reflects the following characteristics of amino acids: blue (hydrophobic), red (positive charge), magenta (negative charge), green (polar), pink (cysteines), orange (glycines), yellow (prolines), cyan (aromatic), white (unconserved). (C) Virus-like particles (VLP) used as antigens for the ELISA assays were produced in 293EXPI cells using mammalian expression system and purified by density gradient. Preparations (1 μg of L1) of each HPV VLP were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and SimplyBlue SafeStain (Thermo Fisher). (D) Expression of L2 therein was assessed by Western blot analysis using rabbit antiserum to α11-88x5. (E) Sera collected two weeks after 10 mice/group were vaccinated three times at 2 week intervals with 25 μg α11-88x5 on 50 μg aluminum phosphate (blue dots) or Gardasil®9 (1/20th human dose) (black dots), were analyzed by direct ELISA using α11-88x5 or the indicated papillomavirus L1 or L1/L2 VLP as antigens. Scatter plots indicate individual serum titers, while the bars indicate the mean values and error bars show standard deviation.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

The plasmid vectors expressing codon optimized L1 and L2 capsid genes of various HPV types were generated previously by our group (available via Addgene), or were kindly provided by John Schiller, NCI, Bethesda, USA or Joakim Dillner, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden.

Cell culture and cell lines

293TT cell lines were maintained in Dulbeco Minimum Essential Medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen, #11965–084) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gemini, Cat# 900-108 50 mL), 1x Penicillin and Streptomycin (Invitrogen, Cat#10378-016), 1x Non-essential Amino acids (Invitrogen, Cat# 11140-050), L-Glutamine (Invitrogen, Cat# 25030-081), Sodium Pyruvate (Invitrogen, Cat# 11360-070). EXPI293F suspension cells were grown in Expi293TM Expression Medium (Gibco, Cat# A1435101) and transfected using the Expifectamine 293 Transfection Kit (Gibco, Cat #A14524).

Papillomavirus L1 and L1/L2 Virus-Like Particle (VLP) preparation

The fourteen papillomavirus VLP types were produced using the Expi293™ Expression system (Gibco, Cat# A14635) in Expi 293F ™ suspension cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat #A14527), per the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 360 × 106 suspension cells were prepared in 120 mL of Expi293 ™ Expression medium (Gibco, Cat# A1435101) in a 250 mL single use PETG Erlenmeyer flask (Thermo Scientific, Cat #41150250). In one tube 6 mL Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium was mixed with 120 μg of plasmid DNA, and in a second 6 mL Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium (Gibco, Cat # 31985-070) was mixed with 324 μL ExpiFectamine293. Each of the mixtures were incubated for 5 minutes, followed by mixing both reactions and incubation for additional 20–30 minutes at room temperature. One day later, 600 μL of Expifectamine 293 ™ Transfection Enhancer 1 and 6 mL of ExpiFectamine 293 ™ Transfection Enhancer 2 were added to the cells. Ninety-six hours post transfection the cell lysates were harvested and the respective lysates were placed in a water bath at 37 °C for 24 h in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline with calcium and magnesium supplemented with 9.5 mM MgCl2, 0.25% Brij58 and 0.1% benzonase. After the 24 h incubation, the cell lysates were chilled on ice, and the NaCl concentration of the lysates was adjusted to 0.8 M. The cell lysates were then separated by ultra-centrifugation for 16 hours at 40,000 × g in an SW40 rotor (Beckman), at 16 °C on a 27%/33%/39% OptiPrep™ step gradient. Fractions were collected from the interface between the 39% and 33% Optiprep as this is the region that properly assembled VLP reside. The fractions were then assessed for purity via Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel, and for L2 by Western blot with antiserum to α11-88x5.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)

Nunc® MaxiSorp™ microtiter 96-well plates (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham MA) were coated with L1/L2 VLP (1 μg of L1 protein diluted in 100 μL PBS/well) overnight at 4 °C. The plates were emptied, washed with PBST (0.01% (v/v) Tween 20 in PBS) and blocked with PBS/1% BSA for 1 h at 37 °C. Serial titrations of the test sera (diluted 3-fold in PBS/1% BSA, 8 times) were added to the emptied plates coated with antigens and blocked and incubated 1 h at RT. Thereafter, the plates were washed 3 times before addition of HRP-labeled sheep anti-mouse IgG diluted 1:5000 in PBS/1% BSA to each well and incubation for 1 h at 37°C. After 3 further washes, 100 μL of 50 mg/mL 2,2’Azinobis [3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid] (Roche, Basel Switzerland) was added to each well for development, and absorbance at 405nm was measured using a Benchmark Plus Microplate Reader (Bio Rad, Hercules CA) after 30 min at RT.

Pseudovirus preparation

293TT cells were co-transfected with HPV L1/L2 expression plasmids and a firefly luciferase or SEAP plasmids as reporters (Addgene) for monitoring PsV infection. The day prior to transfection, 293TT cells were seeded at 9 × 106/T175 flask. On the day of transfection, 19 μg of papillomavirus L1/L2 and 19 μg of reporter plasmid DNA were co-incubated with 114 μL of Mirus transfection reagent (TransIT-2020, Cat# MIR5406) in 3.8 mL of Opti-MEM® Reduced Serum Medium (Gibco, Cat# 31985-070). The transfection cocktail was added to the cells and incubated at 37 °C, humidified atmosphere 5%, CO2 for 44–48 h. The cells were then harvested by trypsinization (0.25% Trypsin, Gibco, Cat#14190-136) and pelleted. The cell pellets were lysed in an equal volume of lysis buffer (PBS-Mg supplemented with 0.5% of Brij 58 and 0.2% benzonase nuclease) for 24 h and incubated at 37 °C in siliconized tubes. The PsV was then salt extracted by adding 5 M NaCl to a final concentration of 850 mM NaCl, and centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 × g at 4 °C. The supernatants containing PsVs were then transferred into new siliconized tubes and stored at −80 °C. When needed, the PsVs were purified using gradient density purification with Optiprep Density Gradient Medium, as for the VLP.

Pseudovirus Based Neutralization Assays

The HPV pseudovirion in vitro neutralization assays were performed as previously described (Pastrana et al., 2004). The 293TT cells were seeded at 0.035 × 106/well in flat-bottom 96-well plates in 100 μL of DMEM with HEPES but lacking phenol red (Gibco, Cat# 21063029) and incubated for 6–8 hours. On an additional 96-well plate, sera from vaccinated animals were titrated, by four-fold serial dilution, eight times beginning at dilution 1:10 for mouse and 1:50 for rabbit sera. The βHPV pseudoviruses were then added to the sera and incubated for 2 h at RT. Thereafter, the mixture of sera and the virus was added to the 293TT cells and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% (v/v) CO2. Upon 72 h of incubation, 40 μL of supernatant in each well was transferred to a new plate containing 20 μL of 0.05% CHAPS and incubated at 65 °C for 30 min. The plates were then incubated on ice for 5 min, and additional 3 min at RT. Upon incubation, 200 μL per well of Alkaline Phosphatase Yellow (pNPP) liquid Substrate System (Sigma, Cat# 7998) was added and plates were incubated for 2 h at RT in the dark. The absorbance at 405 nm was measured using Benchmark Plus Reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Animal study ethics statement

Mouse studies were performed following the guidelines and institutional policies with the prior approval of Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee.

Murine models

Female wild type 16–18g CD-1 ISG outbred mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. TMC6Δ/Δ and TMC8Δ/Δ mice were previously developed (Wu et al., 2020) and cross-bred onto the FVB/NTac background. Female FVB/NTac, BALB/c and FcγR−/− mice (C.129P2(B6)-Fcer1gtm1Rav N12) were purchased from Taconic Inc.

Mouse vaccination

The α11-88x5 antigen was generated as described previously (Jagu et al., 2013; Kalnin et al., 2017) and 25 μg was co-formulated with 50 μg of aluminum phosphate (Adju-Phos; Invivogen) per dose and groups of mice were vaccinated i.m. on days 1, 14 and 28. Control animals were injected i.m. with a one-twentieth human dose of Gardasil®9 or Cervarix or 50 μg of aluminum phosphate. For positive controls, 50 μL rabbit L1 VLP antiserum of the type being used for challenge was passively transferred into the mouse the day prior to challenge, except for HPV49. For HPV49, mice were injected i.m. with 50 μg of pVITRO HPV49 L1/L2 DNA followed by electroporation with an ECM830 Square Wave Electroporation System (BTX Harvard Apparatus company, Holliston, MA, USA). Two needle array was inserted into the site of DNA injection and electroporation was performed with 16 pulses, 20 ms pulse duration at 200 ms intervals three times at 2 week intervals. Serum was harvested 2 weeks later and pooled.

Passive transfer of mice and intravaginal HPV PsV challenge

In all challenge groups, mice were injected with 3 mg of medroxyprogesterone (Depo-Provera, Pfizer, New York NY) to synchronize their estrous cycles, four days before vaginal challenge. For passive transfer, the sera were injected one day prior to challenge. HPV PsVs containing luciferase reporter were used for challenge. The challenge dose of PsV for each HPV type was selected by prior in vivo titration to achieve a minimum signal to noise ratio of 10. The challenge dose was diluted with PBS to 20 μL and mixed with 20 μL of 3% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC). To execute the virus challenge, HPV PsVs were directly instilled into the mouse’s vaginal vault, 20 μL before and 20 μL after cytobrush treatment (15 rotations, alternating directions), while the mice were under ketamine hydrochloride (40 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg) anesthesia. The mice were anesthetized by isoflurane 72 hours after challenge, and 20 μL of luciferin substrate (7.8mg/ml, Promega, Madison WI) was then delivered into the vaginal vault before imaging. Bioluminescence was acquired for 5 min with a Xenogen IVIS 100 (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton MA) imager, and analysis was accomplished with Living Image 2.0 software. Luminescence data were expressed as a ratio of the radiance signal (in photons [p] per second per square centimeter) in the vaginal region to the radiance signal in the thoracic region. The analysis was performed using Living Image 2.5 software (Perkin Elmer), Luminescence was quantified in photons in regions of interest.

Depletion of Gr-1+ wound macrophages and neutrophils

Mice were depleted of Gr-1+ cells by i.p. injection of 100 μg of rat monoclonal RB6–8C5 antibody (BioXCell, West Lebanon, NH) for 3 consecutive days beginning 7 days prior to the vaginal challenge. Depletion was assessed in PBMCs via flow cytometry for Gr-1 and Ly6, with gating for the neutrophil population, one day before passive transfer.

Statistical analyses

To calculate the EC50 value (the reciprocal of the dilution that causes 50% reduction in luciferase activity), the non-linear model Y = Bottom + (Top-Bottom)/(1+10∧((LogEC50-X)*HillSlope)) was fitted to the log10 transformed neutralization titers triplicate data.

The comparison of mean difference between two groups was conducted via two-sample t-test. One-way ANOVA test was applied when comparisons in mean differences across more than two groups, and post-hoc comparison of each group with the no serum or unvaccinated control group was adjusted via Dunnett’s method. In addition, the reduction trend in infectivity while increasing dilution of the total plasma volume was tested via Jonckheere-Terpstra test. All analyses were conducted with GraphPad Prism 9 software or R 4.1.0. All p-values were two-sided and (adjusted) p-values < .05 were considered significant. The stars in figures indicate statistical difference between the indicated groups: **** (p value ≤ 0.0001), *** (p value ≤0.001), ** (p value ≤0.01), * (p value <0.05), ns (p value ≥ 0.05).

4. RESULTS

4.1. Vaccination with α11-88x5, but not Gardasil®9, induced robust serum antibody titers against βHPV VLP.

Given the high degree of protein sequence homology between the five αHPV L2 sequences included in the vaccine and those of diverse papillomaviruses (Figure 1A, B), we hypothesized that α11-88x5 vaccination elicits antibodies broadly reactive with βHPV. Although Gardasil®9 contains L1 VLP derived from nine different human αPV, it is also possible that this licensed vaccine elicits protective immunity against βHPV. To address these questions, outbred female CD-1 mice (n=10) were administered 25 μg α11-88x5 formulated on 50 μg aluminum phosphate or 1/20th human dose of Gardasil®9 via i.m. injection three times at 2-week intervals. Serum was harvested two weeks later and tested by L1/L2 VLP ELISA. The ratio in the VLP preparations of L1, as assessed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining, to L2 (detected by Western blotting (Figure 1C, D) with serum from a rabbit immunized with 50 μg of α11-88x5 and Freunds adjuvant) was similar for each HPV type. HPV16 L1 was included as a negative control, and these VLP were not reactive with rabbit antiserum to α11-88x5. HPV1, a mupapillomavirus that produces benign skin warts, and MmuPV1 L1/L2 VLP were also produced to examine reactivity with more distantly related human and mouse papillomaviruses respectively. The rabbit antiserum to α11-88x5 reacted with L1/L2 VLP of HPV1, but only weakly with MmuPV1 (species pipapillomavirus 2). This reflected its lower sequence homology with αHPV rather than less efficient assembly of MmuPV1 L2 into in VLP.

L1/L2 VLP-based ELISA was used to assess the breadth of cross reactivity of the sera of the CD-1 mice vaccinated with α11-88x5 against L1/L2 VLP of medically relevant βHPV types (Figure 1E, blue dots). These included HPV5, 8, 20, 36, and 38 that are frequently observed in patients with EV, as well as HPV 24, 49, 80, 92, and 96. Sera of mice vaccinated with α11-88x5 showed consistent and robust (Mean ELISA titers of 2 × 104) reactivity against L1/L2 VLP of all of these βHPV, a weaker response to HPV1 (Mean ELISA titer of 70), and surprisingly no detectable response (<10) to MmuPV1 L1/L2 VLPs (Figure 1E, blue dots). A lack of reactivity to HPV16 L1 VLP suggests the L2 specificity of the responses. The reactivity to the vaccine antigen was slightly stronger (titer of ~5.2 × 104), likely reflecting the exact sequence match, and possibly higher levels of L2 antigen or impurities bound to the plate, or that some of the epitopes in L2 11–88 are shielded from antibody below the capsid surface in VLP.

Sera from Gardasil®9 vaccinated mice exhibited high titer (Mean ELISA titer of 2.5 × 106) reactivity to HPV16 L1 VLP, reflecting its presence in the licensed vaccine and demonstrating successful immunization. As expected, they failed to react by ELISA with α11-88x5 (Mean ELISA titer <150). The Gardasil®9 antisera were not significantly reactive with HPV5, 8, 20, 24, 36, 38, 49, 80, 92, or 96 L1/L2 VLP by ELISA (Mean ELISA titer <150; 150 was the lowest titer tested because in our experience lower L1-specific titers in these assays generally represent binding to internal epitopes of VLP that have fallen apart that are not biologically relevant). Surprisingly, sera from 3/10 mice were reactive with HPV76 and HPV38 L1/L2 VLP, and 2/10 with HPV80 suggesting potential for cross-protection against some βHPV, or partial disassembly of the L1/L2 VLP when bound to the microtiter plates that exposes cross-reactive internal epitopes (Figure 1E, black dots).

4.2. Vaccination with α11-88x5 induced neutralizing antibodies against βHPV

While the L1/L2 VLP ELISA studies showed cross-reactivity of α11-88x5 antisera with all βHPV tested, this assay measures overall capsid-binding antibody response, and it does not distinguish whether the antibody is neutralizing or otherwise protective. To assess for functional cross-neutralization responses, we conducted an in vitro HPV5, 49, 76 and 96 pseudovirion neutralization assay using sera from vaccinated mice (Supplemental Figure S1). As a negative control, we used sera from mice vaccinated with alum adjuvant. Neither the sera of mice vaccinated with alum alone nor Cervarix® antisera neutralized these four βHPV PsVs (titer <10). The sera showed neutralization titers for HPV76 of 63, for HPV5 of 732, for HPV96 of 1111 and for HPV49 of 468. In addition, antiserum was tested from a rabbit vaccinated on days 1, 28, 42 with 50 μg α11-88x5 in complete Freunds adjuvant (CFA) with the initial dose and incomplete Freunds adjuvant (IFA) thereafter. The rabbit antisera (drawn two weeks after the final boost) robustly neutralized HPV5, 49, 76 and 96 with titers of 204,800, 51,200, 51,200 and 12,800 respectively. The in vitro antibody titers were likely higher in the rabbit than in mice because of the use of a stronger adjuvant system. The results demonstrated the cross-neutralization activity of the α11-88x5 antisera for diverse βHPV species, although the titers were low in mice when utilizing alum adjuvant.

4.3. Vaccination with α11-88x5 protected wild type and EV model mice against HPV5 challenge

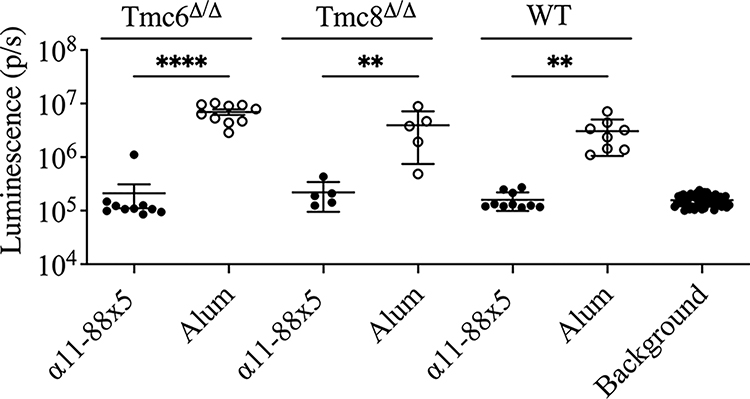

To assess whether vaccination with α11-88x5 is sufficient to protect against HPV5, we first vaccinated female FVB/N mice (n=10/group) with 25 μg α11-88x5 formulated with 50 μg aluminum phosphate, or aluminum phosphate only (n=8/group) three times at two-week intervals. Since classic EV is an autosomal recessive hereditary skin disorder caused by biallelic loss-of-function mutations in TMC6, TMC8 or CIB1, here Tmc6Δ/Δ and Tmc8Δ/Δ FVB/N mice were each used as models. Thus Tmc6Δ/Δ (n=10/group) and Tmc8Δ/Δ (n=5/group) FVB/N mice were also vaccinated concurrently with 25 μg α11-88x5 formulated with aluminum phosphate, or aluminum phosphate only three times at two-week intervals. Two weeks after the final vaccination, all the mice were challenged intravaginally with HPV5 PsV. Vaginal challenge was utilized as infection is more consistent in mice than cutaneous administration, and protection from cutaneous challenge with this vaccine has previously been demonstrated (Kalnin et al., 2017). The groups of wildtype, Tmc6Δ/Δ and Tmc8Δ/Δ FVB/N mice were each strongly protected, with bioluminescence signals that were not significantly different to background, whereas robust infection occurred in mice that were vaccinated with alum only (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Vaccination with α11-88x5 protects against HPV5 PsV challenge in wild type and EV model mice.

Female FVB WT (n=10 or 8/group) or Tmc6Δ/Δ (n=10/group) or Tmc8Δ/Δ (n=5/group) mice were immunized with 25 μg of multimer vaccine formulated on 50 μg aluminum phosphate (alum) or alum adjuvant only, 3 times at two-week intervals. Two weeks post final vaccination, the mice were challenged with HPV5 PsV. P values were calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA with the Šídák’s multiple comparisons test.

4.4. Vaccination with α11-88x5 protects outbred mice against challenge across βHPV species

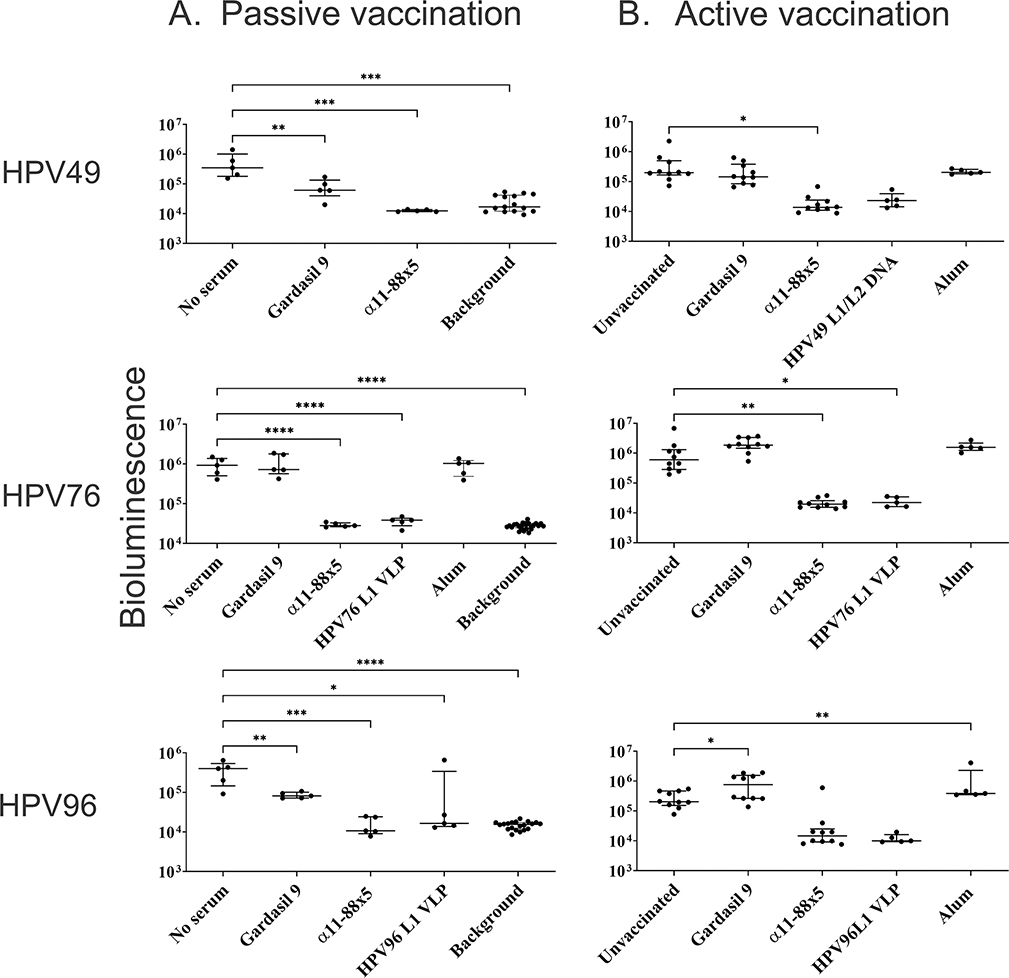

HPV5 is a betapapillomavirus 1, but there are additional species within genus βHPV. We sought to broaden the observation that α11-88x5 vaccination protects against HPV5 challenge to other βHPV species. Prior studies suggest that protection upon multimer vaccination is mediated by L2-specific humoral immunity. To assess whether the serum antibodies elicited upon α11-88x5 vaccination provided protection, passive transfer of 50 μL of rabbit antisera was administered into each naïve mouse (n=5/group) one day before challenge. The volume of sera corresponds to ~1:25 dilution, assuming the plasma volume to be 1.34 mL per mouse. After passive immunization, the animals were challenged with the HPV49, HPV76, or HPV96 PsV encapsulating luciferase. As in the challenge of actively vaccinated mice, the vaginal infection was visualized by IVIS imaging of luciferase-based bioluminescence, 3 days after the challenge (Figure 3A). The results of the passive transfer suggest that the α11-88x5 antisera can protect mice against challenge with different species of genus β, including betapapillomavirus 3 (HPV49 and HPV76) and betapapillomavirus 5 (HPV96). Gardasil®9 antisera did not impact HPV76 infection, but surprisingly provided weak (<1 log) but significant protection against HPV49 and HPV96. Passive transfer of 50 μL HPV L1 VLP antisera was used as a positive control and was protective against the corresponding HPV types’ challenge.

Figure 3. Assessment of protection against challenge with HPV49, 76 and 96 pseudovirions after passive and active vaccination.

(A) Protection via passive transfer of rabbit antisera to Gardasil®9 or α11-88x5 (50 μg dose on Freunds adjuvant) was assessed in CD-1 ISG mice (n=5/group) followed by vaginal challenge with βHPV PsVs derived from types 49, 76 and 96. Fifty microliters of sera from individual rabbits were passively transferred each mouse by i.p. injection. Mice were challenged intravaginally with PsV the following day. (B) Female CD-1 IGS mice (n=10/group) were immunized with multimer vaccine (25 μg formulated on alum), Gardasil ®9, or alum adjuvant by i.m. injection three times in 2 week intervals. Two weeks post final vaccination, the mice were challenged intravaginally with βHPV PsVs derived from types 49, 76 and 96. The bioluminescence images were acquired 72 h post challenge for 5 min with a Xenogen IVIS 100. P values were calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA with the Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test.

We sought to further validate these findings with a human-compatible adjuvant by using active vaccination of outbred CD-1 female mice (n=10/group) with three i.m. vaccinations at 2-week intervals with 25 μg α11-88x5 formulated with 50 μg aluminum phosphate, or aluminum phosphate only, or with 1/20th human dose of Gardasil®9. The Gardasil®9 group was included as some cross-reactivity with βHPV L1/L2 VLP was observed by ELISA (Figure 1E) and some protection in passive transfer studies (Figure 3A). An unvaccinated group was also included as a negative control in each of the challenge groups. As a positive control, mice were vaccinated with HPV49 L1/L2 DNA by electroporation three times at 2 week intervals, or naïve mice were administered i.p. one day prior to challenge antiserum derived from rabbits vaccinated with HPV76 or HPV96 L1 VLP produced in insect cells; the mice were then challenged intravaginally with PsV derived from HPV49, or HPV76 (both species betapapillomavirus 3), or HPV96 (betapapillomavirus 5) respectively. Remarkably, α11-88x5 vaccination fully protected mice against challenge with HPV 49, 76, 96 (Figure 3B). No significant protection was observed in Gardasil®9 or alum only vaccination groups. Vaccination with pVITRO HPV49 L1/L2 DNA and antisera targeting the L1 of the type used for challenge were used as positive controls and were protective via passive transfer against all three HPV types tested.

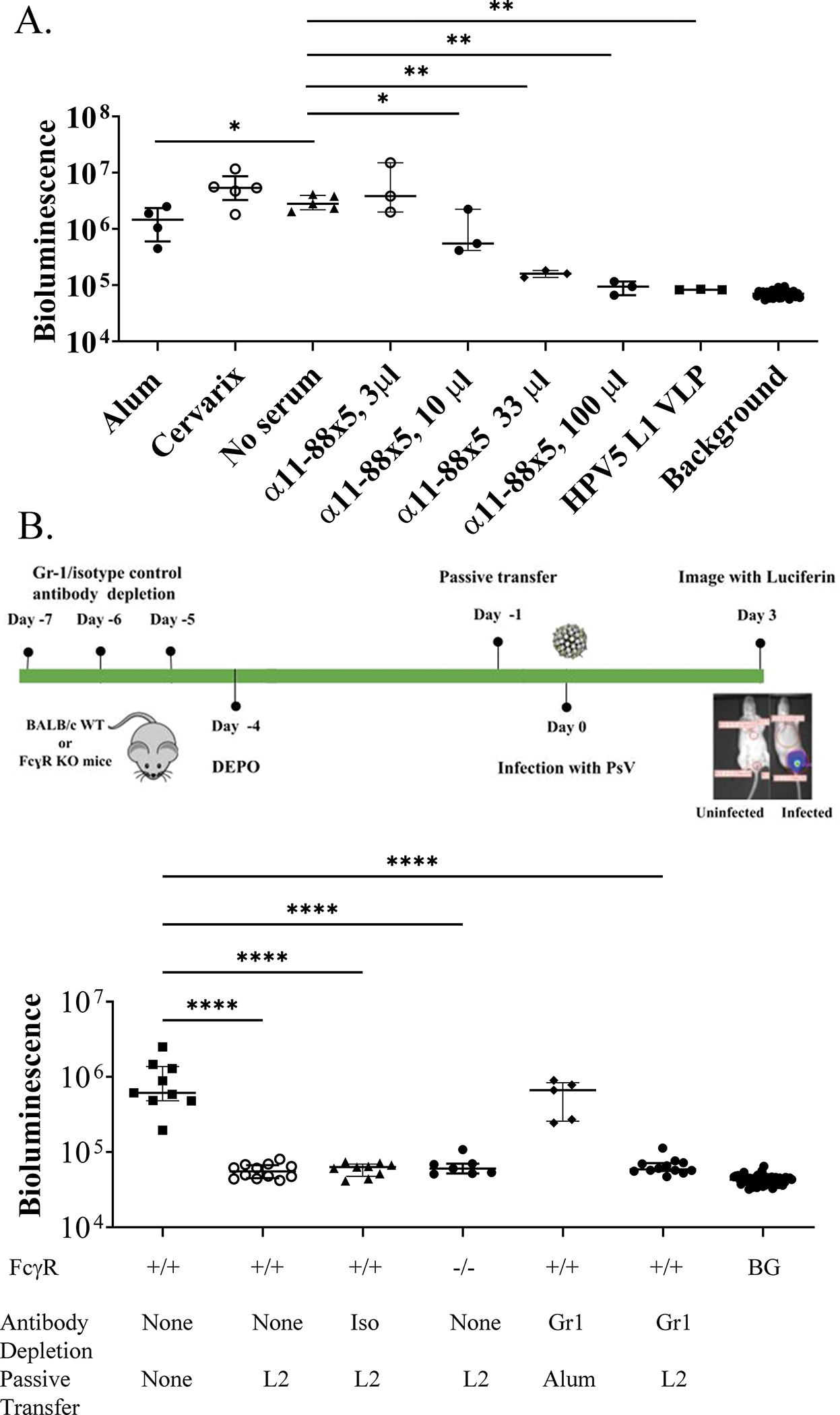

A further passive transfer study was performed using pooled sera collected post-immunization from BALB/c mice administered three intra-muscular vaccinations at 2-week intervals with 25 μg α11-88x5 formulated with 50 μg aluminum phosphate, Cervarix®, or alum alone. The in vitro neutralization titer against HPV5 of the pooled α11-88x5 antiserum was 40 and <10 for the Cervarix® or alum alone antiserum pools. The pooled sera were passively transferred into naïve female CD-1 mice that were then challenged with HPV5 PsV one day later. No significant protective activity was observed when 3 μL of α11-88x5 antisera was injected per mouse, but a reduction in mean infectivity was observed with 10 μL (trend, p=0.07) and 33 μL (p=0.04), and passive transfer of 100 μL, a ~1:13 dilution in the total plasma volume of a mouse, reduced the bioluminescent signal of the PsV to background levels (Figure 4A). While increasing the total serum volume passively transferred from no serum to 100 μL of α11-88x5 antisera, the monotonic decreasing trend in infectivity was significant (p < 0.0001). Passive transfer of 100 μL of either pooled Cervarix® or alum only antiserum did not significantly impact HPV5 infectivity. The protection of naïve mice against challenge with these βHPV types by passive transfer suggests that protection is conferred by L2-specific antibodies.

Figure 4. Impact of dose, or FcγR knockout and Gr-1 antibody depletion in the recipient upon protection from HPV5 challenge via passive transfer of α11-88x5 antiserum.

Protection via passive transfer of pooled sera from mice vaccinated with 25 μg of α11-88x5 multimer vaccine formulated on 50 μg aluminum phosphate, or alum only, was assessed in mice following intravaginal challenge with HPV5 PsV. (A) Either 3 μL, 10 μL, 33 μL or 100 μL of pooled α11-88x5 antisera or 100 μL of Cervarix® or alum only pooled mouse antisera or 33 μL HPV5 L1 VLP antiserum from a rabbit were administered i.p. into individual female CD-1 ISG mice followed by intravaginal HPV5 PsV challenge the following day. The bioluminescence images were acquired 72 h post challenge for 5 min with a Xenogen IVIS 100 and quantified in the region of interest (photons/sec) or an irrelevant region of the same size to determine background. The lines indicate the median values and the bars indicate interquartile range. (B) Gr-1+ cells were depleted from BALB/c mice (n=17) by administration of Gr-1-specific rat monoclonal antibody on days -10, -9 and -8 prior to challenge, as shown on the schema. As a control, additional BALB/c mice (n=9) likewise received an isotyped-matched irrelevant rat antibody. These mice were administered on day -1 prior to challenge 50 μL of the same pooled antiserum (‘L2’, see its titration in Figure 4A) from mice administered three intra-muscular vaccinations at 2-week intervals with 25 μg α11-88x5 multimer formulated with 50 μg aluminum phosphate (n=12 of Gr-1 depleted ‘Gr1’, and n=9 of isotype ‘Iso’ control) or alum only antiserum (‘Alum’ n=5 of the Gr-1 depleted mice). FcγR-deficient mice (−/−, n=7) and control BALB/c mice (+/+, n=12) were likewise each administered 50 μL of the same pooled α11-88x5 antiserum (L2). An additional group (n=10) of control mice received no treatments. All groups of mice were simultaneously challenged with HPV5 PsV and then imaged as in (A). BG=background.

4.5. Neither FcγR chain nor Gr-1+ macrophages/neutrophils are required for protection against HPV5 via passive transfer of α11-88x5 antiserum

In addition to direct neutralization, virus-bound antibodies can interact via the Fc domain with FcRs on wound macrophages or neutrophils to trigger phagocytosis. Because in passive transfer studies we saw full protection against βHPV PsV challenge but in vitro neutralization titers were low, we investigated whether the L2 antibodies play a role in protection by antibody-mediated phagocytosis using FcγR−/− mice that lack the gamma chain subunit of the FcgRI, FcgRII and FceRI. These FcγR−/− mice (n=7) and control BALB/c mice (n=12) were each administered 50 μL pooled antiserum from BALB/c mice administered three i.m. vaccinations at 2-week intervals with 25 μg α11-88x5 formulated with 50 μg aluminum phosphate (see its titration in Figure 4A). Both groups of mice were similarly protected against HPV5 challenge (signal not significantly different from background) as compared to untreated mice (p=0.9997 for both), suggesting that these Fc receptors are not required for protection.

Day et al described the accumulation of neutrophils at the site of vaginal challenge in mice that had been passively transferred with protective levels of antibody to L2 11-88x5 suggesting that phagocytes like neutrophils, monocytes and macrophages carrying multiple receptors for Fc could contribute to this protection by engulfment of L2 antibody-coated virus (Day et al., 2010). Anti-granulocyte receptor-1 (Gr-1) monoclonal antibody RB6–8C5 has been used extensively to deplete neutrophils, monocytes and wound macrophages (Daley et al., 2008). Thus, to determine the role of these phagocytes in the L2 antibody-mediated protection, we first depleted the Gr-1+ cells from BALB/c mice (n=17) by administration of Gr-1-specific rat monoclonal antibody on days -7, -6 and -5 prior to challenge. A depletion of 94% circulating Gr-1+ cells was determined by flow cytometry by day -2 (Supplemental Figure S2). As a control, additional mice (n=9) received an isotyped-matched irrelevant rat antibody on the same schedule. Mice were administered one day prior to challenge 50 μL of the same pooled antiserum from mice administered three intra-muscular vaccinations at 2-week intervals with 25 μg α11-88x5 formulated with 50 μg aluminum phosphate (n=12 of Gr-1 depleted and n=9 of isotype control) or alum only (n=5 of the Gr-1 depleted mice). All of the mice were then challenged intravaginally with HPV5 PsV on day 0. Neither depletion of the Gr-1+ cells nor administration of isotyped matched monoclonal antibody impacted the protective effect of the α11-88x5 antiserum against HPV5 challenge. As expected, the signal for alum transferred Gr-1 depleted mice was comparable to the signal observed in the challenge only group (n=9) (Figure 4B). These observations suggest that Gr-1+ phagocytes are not required for protection conferred by α11-88x5 antiserum.

5. DISCUSSION

Three immunizations with the single antigen vaccine α11-88x5 (or α11-88x8) formulated on aluminum phosphate was previously shown in both the mouse (Jagu et al., 2013) and rabbit (Kalnin et al., 2017) challenge models to broadly protect against vaginal and skin challenge respectively with all αHPV tested (HPV6, 16, 26, 31, 33, 35, 45, 51, 56, 58, 59). This vaccination has the potential to reduce the burden of anogenital and oropharyngeal cancers as well as genital warts (Jagu et al., 2013; Kalnin et al., 2017; Roden and Stern, 2018). Remarkably, protection against cutaneous CRPV challenge (in addition to HPV6, 16, 31, 45, 58) was also seen in the rabbit model one year post vaccination with α11-88x5 (or α11-88x8) formulated on aluminum phosphate suggesting the durability and breadth of response (Kalnin et al., 2017). Here we show this vaccine also elicits protective immunity against diverse βHPV across several species within the genus (betapapillomaviruses 1, 3 and 5). Such broad coverage is important because, in contrast to HPV16’s dominant etiologic role in anogenital and oropharyngeal cancers, it is unclear which βHPV types in particular are co-carcinogens in the genesis of CSCC.

Consistent to previous findings with oncogenic αHPV, we showed that α11-88x5 vaccination protects against βHPV challenge via induction of L2-specific antibodies. The L2 antibodies induced by α11-88x5 vaccination recognized diverse βHPV emphasizing the potential of broad protection against a wide range of HPV types. Indeed, we previously showed in vitro neutralization of all 34 HPV types tested (including 5 βHPV and species alphapapillomavirus 1,2,4–7,9–11) using rabbit antiserum to α11-88x8 (Kwak et al., 2014). Nevertheless, there are limits to the cross-reactivity. Vaccination with α11-88x5 induced a relatively weaker antibody response to HPV1 (species mupapillomavirus 1) and no response was detected by ELISA with MmuPV1 L1/L2VLP (species pipapillomavirus 2), likely reflecting their lower L2 sequence homology. However, α11-88x5 antiserum did react with MmuPV1 L2 weakly by Western blot (Figure 1D) as there are clearly conserved sequences (Figure 1B). It is likely that to best cover the broadest range of HPV types upon vaccination with concatenated multitype L2 fusion proteins it will be beneficial to include sequences derived from L2 of several divergent βHPV types, or even from other medically relevant species like mupapillomavirus 1, in addition to the αHPV-derived sequences that are present in the current construct. For example, we previously described an 11-88x5 construct derived from HPV1, 5, 6, 16 and 18 L2 sequences that was readily expressed and broadly immunogenic (Jagu et al., 2009). Clearly, the selection of sequences should reflect the target indication(s) and the HPV species responsible for those medical needs.

The role of βHPV as a co-carcinogen for CSCC remains controversial (Rollison et al., 2019). Indeed, a symbiotic role has been proposed in which prevalent βHPV skin infections, including UV-induced precursor lesions, trigger antiviral immunity that suppresses the development of CSCC, but cannot in immunosuppressed patients resulting in acquired EV (Strickley et al., 2019). However, this hypothesis seems at odds with the natural history of classic EV, given reports of functionally normal adaptive immunity in these patients, and the emergence of CSCC out of flat warts (de Jong et al., 2018a; de Jong et al., 2018b). Furthermore, a plethora of murine studies using cutaneous animal papillomavirus infection or K14 promotor-driven βHPV E6/E7 transgenic expression in combination with UV show synergistic development of CSCC and loss of viral sequences (Dorfer et al., 2021; Viarisio et al., 2011; Viarisio et al., 2018). Likewise, studies in primary human keratinocytes show that βHPV replication suppresses DNA repair providing a plausible mechanism for a co-carcinogenic role with UV exposure (Wallace et al., 2012, 2015). Epidemiologic studies, a pillar in assigning causation for human diseases, have not so far proven definitive. A barrier to resolving βHPV’s role in CSCC is the proposed ‘hit-and-run’ mechanism resulting from selection against the virus after transformation. The role of BPV4 in promoting upper alimentary tract cancers in cattle exposed to bracken fern carcinogens provides an example of such a mechanism, since the virus is absent from the cancers (Campo et al., 1994). Prevention of βHPV infections or suppression of viral load by timely vaccination (e.g. before organ transplantation while on the waiting list) of appropriate cohorts of patients offers a potentially definitive approach to finally resolve their contribution to the development of CSCC.

Classic EV patients with inherited biallelic loss-of-function mutations in TMC6, TMC8 or CIB1 appear logical candidates for a βHPV preventive/suppressive/protective vaccine, and here we show that homozygous loss of at least the first two of these genes do not impact antibody responses to L2 vaccination in mice. For acquired EV, such as in OTR and AIDS patients, vaccination would likely be best accomplished prior to their immunosuppression as humoral responses are generally preserved. HPV L1 VLP vaccination is immunogenic, albeit at reduced titers, in HIV+ patients and those on immunosuppressive drug regimens post-transplant suggesting boosting might be useful (Boey et al., 2021). Support for this approach is provided by studies from Vinzon et al showing L1 VLP vaccination in the M. coucha model after MnPV1 challenge and immunosuppression with cyclosporine still protects against the development of CSCC (Vinzon et al., 2014). Suppression of viral recrudescence and spread by neutralizing antibodies is a probable mechanism. Nevertheless, our data only address L2-based vaccination prior to βHPV exposure (or immunosuppression). While vaccination against αHPV just prior to sexual debut is optimal, vaccination against βHPV should occur earlier as these cutaneous infections are acquired throughout life. An advantage of early childhood vaccination with an L2 multimer would be the potential to prevent the morbidity and treatment costs associated with benign cutaneous infections, such as HPV1-driven hand and foot warts (Roden and Stern, 2018).

Vaccination with α11-88x5, but not Gardasil® or Cervarix®, was protective against cutaneous papillomas resulting from CRPV challenge of domestic rabbits (Kalnin et al., 2017), a classic model of virally-induced CSCC pioneered by Shope (Shope, 1937). While systemic regression of warts occurs in a variable proportion of rabbits as a consequence of a specific cell-mediated immune response, persistent warts may progress into invasive CSCCs. Progression into CSCCs is observed in approximately 25% of cottontail rabbits and in up to 75% of domestic rabbits with persistent CRPV warts (Salmon et al., 2000). Here, our findings suggest that neither Gardasil®9 nor Cervarix® are likely to provide protection against βHPV, whereas an L2 multimer has promise in this regard. The L1 VLP vaccine technology is highly effective even for βHPV, but it is not clear which types are the drivers of CSCC. Since L1 VLP induce type-restricted immunity and there are a plethora of βHPV types associated with CSCC, generating a sufficiently multi-valent formulation is likely problematic.

Passive transfer studies confirm that humoral responses to L2 multimer vaccination are sufficient to confer immunity, although they do not rule out a role for cellular immunity. However, CRPV, BPV1 or HPV16 L2 1–88 vaccination protected rabbits from papillomas resulting from CRPV, but not CRPV DNA challenge, and the growth of L2 knockout CRPV DNA-induced warts was similar to wild type, implying no role for cytotoxic T cell responses in protection (Gambhira et al., 2007). Direct viral neutralization is clearly central in mediating protection, and in vitro neutralization assays of sera suggest that even very low titers are sufficient. The L1/L2 VLP-specific ELISA suggests a robust antibody response to α11-88x5 with titers of ~104 but neutralization titers are low, and sometimes undetectable (<10) by standard HPV pseudovirion-based neutralization assays in animals shown to be immune to viral challenge.

Standard HPV pseudovirion-based neutralization assays are poorly sensitive for L2-specific protective antibodies (Day et al., 2012). This may reflect in part that rapid pseudovirion infection of 293TT cells on plastic poorly mimics the slow kinetics of native virion binding to the basement membrane and encounter with basal keratinocytes during repair of microtrauma of the anogenital mucosa. Differences may include structural changes in the capsid induced by binding to the basement membrane versus directly to 293TT cells, and the nature and local concentration of extracellular furin(-like) proprotein convertases needed to cleave the amino terminus of L2 during infection. Another consideration is whether Fc receptor-mediated recognition and phagocytosis of L2 antibody-coated virions contributes significantly to protection via α11-88x5, a process that would not be detected by in vitro HPV pseudovirion-based neutralization assays. However, while passive transfer studies with L2 17–36 specific monoclonal antibody did show a marginal but significant reduction in protection against HPV16 PsV challenge in FcγR-deficient mice or upon prior depletion of Gr-1+ phagocytes (Wang et al., 2018), this effect was not apparent with α11-88x5 antisera upon HPV5 challenge. This discrepancy may reflect the use of too high a dose of antiserum, masking the effect, or differences in a monoclonal versus polyclonal antibody response or viral challenge. Nevertheless, here we find no contribution of phagocytosis to protection against HPV5 conferred by α11-88x5 antiserum, implying direct neutralization of the viral inoculum by the polyclonal L2 antibody at the challenge site.

The use of human-compatible adjuvants more potent than alum alone (e.g. ASO4, AF04, MF59, GPI-0100 or ISS1018) (Jagu et al., 2009), or approaches such as virus display warrants consideration to enhance the breadth and duration of immunity (Roden and Stern, 2018). Indeed, while vaccination with α11-88x5 in aluminum phosphate protected rabbits over one year, protective antibody titers in serum waned; immunity conferred by passive transfer dropped from 1:2500 against HPV16 at 1 month post immunization to <20 by 12 months (Kalnin et al., 2017). Careful consideration of the types of L2 used in the multimer vaccine, schedule of delivery and adjuvant selection is warranted because each likely impacts the strength and duration of serum neutralization titer, and thus whether the threshold necessary for protection against more distantly related types is reached and maintained.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under awards P30CA06973, P50CA098252, R01CA233486, R01CA237067. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional support was provided by the Charles T. Bauer Charitable Foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Under license agreements between BravoVax Co., Ltd. and the Johns Hopkins University, Dr. Roden is entitled to distributions of payments associated with an invention described in this publication. Dr. Roden also owns equity in PathoVax LLC, Up Therapeutics LLC, Papivax LLC and Papivax Biotech Inc. and is a member of their scientific advisory boards. These arrangements have been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

Data Availability

The data supporting the finding of this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Alam M, Ratner D, 2001. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 344, 975–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo Muhr LS, Hultin E, Dillner J, 2021. Transcription of human papillomaviruses in nonmelanoma skin cancers of the immunosuppressed. Int J Cancer 149, 1341–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HU, Burk RD, Chen Z, van Doorslaer K, zur Hausen H, de Villiers EM, 2010. Classification of papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology 401, 70–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boey L, Curinckx A, Roelants M, Derdelinckx I, Van Wijngaerden E, De Munter P, Vos R, Kuypers D, Van Cleemput J, Vandermeulen C, 2021. Immunogenicity and Safety of the 9-Valent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients and Adults Infected With Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Clin Infect Dis 73, e661–e671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwes Bavinck JN, Feltkamp MCW, Green AC, Fiocco M, Euvrard S, Harwood CA, Proby CM, Naldi L, Diphoorn JCD, Venturuzzo A, Tessari G, Nindl I, Sampogna F, Abeni D, Neale RE, Goeman JJ, Quint KD, Halk AB, Sneek C, Genders RE, de Koning MNC, Quint WGV, Wieland U, Weissenborn S, Waterboer T, Pawlita M, Pfister H, group E-H-U-C, 2017. Human papillomavirus and posttransplantation cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: A multicenter, prospective cohort study. Am J Transplant. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo MS, O’Neil BW, Barron RJ, Jarrett WF, 1994. Experimental reproduction of the papilloma-carcinoma complex of the alimentary canal in cattle. Carcinogenesis 15, 1597–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley JM, Thomay AA, Connolly MD, Reichner JS, Albina JE, 2008. Use of Ly6G-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. J Leukoc Biol 83, 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day PM, Kines RC, Thompson CD, Jagu S, Roden RB, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, 2010. In vivo mechanisms of vaccine-induced protection against HPV infection. Cell Host Microbe 8, 260–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day PM, Pang YY, Kines RC, Thompson CD, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, 2012. A human papillomavirus (HPV) in vitro neutralization assay that recapitulates the in vitro process of infection provides a sensitive measure of HPV L2 infection-inhibiting antibodies. Clin Vaccine Immunol 19, 1075–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong SJ, Crequer A, Matos I, Hum D, Gunasekharan V, Lorenzo L, Jabot-Hanin F, Imahorn E, Arias AA, Vahidnezhad H, Youssefian L, Markle JG, Patin E, D’Amico A, Wang CQF, Full F, Ensser A, Leisner TM, Parise LV, Bouaziz M, Maya NP, Cadena XR, Saka B, Saeidian AH, Aghazadeh N, Zeinali S, Itin P, Krueger JG, Laimins L, Abel L, Fuchs E, Uitto J, Franco JL, Burger B, Orth G, Jouanguy E, Casanova JL, 2018a. The human CIB1-EVER1-EVER2 complex governs keratinocyte-intrinsic immunity to beta-papillomaviruses. J Exp Med 215, 2289–2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong SJ, Imahorn E, Itin P, Uitto J, Orth G, Jouanguy E, Casanova JL, Burger B, 2018b. Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis: Inborn Errors of Immunity to Human Beta-Papillomaviruses. Front Microbiol 9, 1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, zur Hausen H, 2004. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology 324, 17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfer S, Strasser K, Schrockenfuchs G, Bonelli M, Bauer W, Kittler H, Cataisson C, Fischer MB, Lichtenberger BM, Handisurya A, 2021. Mus musculus papillomavirus 1 is a key driver of skin cancer development upon immunosuppression. Am J Transplant 21, 525–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcaro M, Castanon A, Ndlela B, Checchi M, Soldan K, Lopez-Bernal J, Elliss-Brookes L, Sasieni P, 2021. The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme in England, UK, on cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence: a register-based observational study. Lancet 398, 2084–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambhira R, Jagu S, Karanam B, Gravitt PE, Culp TD, Christensen ND, Roden RB, 2007. Protection of rabbits against challenge with rabbit papillomaviruses by immunization with the N terminus of human papillomavirus type 16 minor capsid antigen L2. J Virol 81, 11585–11592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraets D, Alemany L, Guimera N, de Sanjose S, de Koning M, Molijn A, Jenkins D, Bosch X, Quint W, Group RHTS, 2012. Detection of rare and possibly carcinogenic human papillomavirus genotypes as single infections in invasive cervical cancer. J Pathol 228, 534–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasche D, Vinzon SE, Rosl F, 2018. Cutaneous Papillomaviruses and Non-melanoma Skin Cancer: Causal Agents or Innocent Bystanders? Front Microbiol 9, 874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagu S, Karanam B, Gambhira R, Chivukula SV, Chaganti RJ, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, Roden RB, 2009. Concatenated multitype L2 fusion proteins as candidate prophylactic pan-human papillomavirus vaccines. J Natl Cancer Inst 101, 782–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagu S, Kwak K, Schiller JT, Lowy DR, Kleanthous H, Kalnin K, Wang C, Wang HK, Chow LT, Huh WK, Jaganathan KS, Chivukula SV, Roden RB, 2013. Phylogenetic considerations in designing a broadly protective multimeric L2 vaccine. J Virol 87, 6127–6136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P, Moller B, Hansen S, 2000. Skin cancer in kidney and heart transplant recipients and different long-term immunosuppressive therapy regimens. J Am Acad Dermatol 42, 307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalnin K, Chivukula S, Tibbitts T, Yan Y, Stegalkina S, Shen L, Cieszynski J, Costa V, Sabharwal R, Anderson SF, Christensen N, Jagu S, Roden RBS, Kleanthous H, 2017. Incorporation of RG1 epitope concatemers into a self-adjuvanting Flagellin-L2 vaccine broaden durable protection against cutaneous challenge with diverse human papillomavirus genotypes. Vaccine 35, 4942–4951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaer SK, Dehlendorff C, Belmonte F, Baandrup L, 2021. Real-World Effectiveness of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Against Cervical Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 113, 1329–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak K, Jiang R, Wang JW, Jagu S, Kirnbauer R, Roden RB, 2014. Impact of inhibitors and L2 antibodies upon the infectivity of diverse alpha and beta human papillomavirus types. PLoS One 9, e97232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas A, Leonardi-Bee J, Bath-Hextall F, 2012. A systematic review of worldwide incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br J Dermatol 166, 1069–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin-Drubin ME, 2015. Human papillomaviruses and non-melanoma skin cancer. Seminars in oncology 42, 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nindl I, Gottschling M, Stockfleth E, 2007. Human papillomaviruses and non-melanoma skin cancer: basic virology and clinical manifestations. Disease markers 23, 247–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth G, Jablonska S, Favre M, Croissant O, Jarzabek-Chorzelska M, Rzesa G, 1978. Characterization of two types of human papillomaviruses in lesions of epidermodysplasia verruciformis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 75, 1537–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastrana DV, Buck CB, Pang YY, Thompson CD, Castle PE, FitzGerald PC, Kruger Kjaer S, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, 2004. Reactivity of human sera in a sensitive, high-throughput pseudovirus-based papillomavirus neutralization assay for HPV16 and HPV18. Virology 321, 205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer M, de Martel C, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Bray F, Franceschi S, 2016. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012: a synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 4, e609–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybyszewska J, Zlotogorski A, Ramot Y, 2017. Re-evaluation of epidermodysplasia verruciformis: Reconciling more than 90 years of debate. J Am Acad Dermatol 76, 1161–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden RBS, Stern PL, 2018. Opportunities and challenges for human papillomavirus vaccination in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 18, 240–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollison DE, Viarisio D, Amorrortu RP, Gheit T, Tommasino M, 2019. An Emerging Issue in Oncogenic Virology: the Role of Beta Human Papillomavirus Types in the Development of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Virol 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon J, Nonnenmacher M, Caze S, Flamant P, Croissant O, Orth G, Breitburd F, 2000. Variation in the nucleotide sequence of cottontail rabbit papillomavirus a and b subtypes affects wart regression and malignant transformation and level of viral replication in domestic rabbits. J Virol 74, 10766–10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shope RE, 1937. Immunization of Rabbits to Infectious Papillomatosis. J Exp Med 65, 219–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickley JD, Messerschmidt JL, Awad ME, Li T, Hasegawa T, Ha DT, Nabeta HW, Bevins PA, Ngo KH, Asgari MM, Nazarian RM, Neel VA, Jenson AB, Joh J, Demehri S, 2019. Immunity to commensal papillomaviruses protects against skin cancer. Nature 575, 519–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tommasino M, 2017. The biology of beta human papillomaviruses. Virus Res 231, 128–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viarisio D, Mueller-Decker K, Kloz U, Aengeneyndt B, Kopp-Schneider A, Grone HJ, Gheit T, Flechtenmacher C, Gissmann L, Tommasino M, 2011. E6 and E7 from beta HPV38 cooperate with ultraviolet light in the development of actinic keratosis-like lesions and squamous cell carcinoma in mice. PLoS Pathog 7, e1002125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viarisio D, Muller-Decker K, Accardi R, Robitaille A, Durst M, Beer K, Jansen L, Flechtenmacher C, Bozza M, Harbottle R, Voegele C, Ardin M, Zavadil J, Caldeira S, Gissmann L, Tommasino M, 2018. Beta HPV38 oncoproteins act with a hit-and-run mechanism in ultraviolet radiation-induced skin carcinogenesis in mice. PLoS Pathog 14, e1006783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinzon SE, Braspenning-Wesch I, Muller M, Geissler EK, Nindl I, Grone HJ, Schafer K, Rosl F, 2014. Protective vaccination against papillomavirus-induced skin tumors under immunocompetent and immunosuppressive conditions: a preclinical study using a natural outbred animal model. PLoS Pathog 10, e1003924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace NA, Robinson K, Howie HL, Galloway DA, 2012. HPV 5 and 8 E6 abrogate ATR activity resulting in increased persistence of UVB induced DNA damage. PLoS Pathog 8, e1002807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace NA, Robinson K, Howie HL, Galloway DA, 2015. beta-HPV 5 and 8 E6 disrupt homology dependent double strand break repair by attenuating BRCA1 and BRCA2 expression and foci formation. PLoS Pathog 11, e1004687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JW, Wu WH, Huang TC, Wong M, Kwak K, Ozato K, Hung CF, Roden RBS, 2018. Roles of Fc Domain and Exudation in L2 Antibody-Mediated Protection against Human Papillomavirus. J Virol 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans IARC, 1995. Human papillomaviruses. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 64, 1–378. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CJ, Li X, Sommers CL, Kurima K, Huh S, Bugos G, Dong L, Li W, Griffith AJ, Samelson LE, 2020. Expression of a TMC6-TMC8-CIB1 heterotrimeric complex in lymphocytes is regulated by each of the components. J Biol Chem 295, 16086–16099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- zur Hausen H, 2002. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer 2, 342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the finding of this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.