Abstract

First described by Fischer in 1962, the limb shaking syndrome is a haemodynamic transient ischaemic attack (TIA) clinically characterised by brief, dysrhythmic, flailing or jerking movements, involving limbs contralateral to an occlusion of the internal carotid artery (ICA), which occur with a change in posture such as standing from sitting. We present the case of a woman in her 60s who presented with left-sided weakness suggestive of right hemispheric stroke, with previous episodes of limb shaking TIAs, which were caused by significant cerebral hypo-perfusion due to a combination of postural hypotension and a significant stenosis of the left ICA.

Keywords: Stroke, Epilepsy and seizures

Background

The incidence of first-ever transient ischaemic attack (TIA) in the UK is approximately 50/100 000 people per year.1 A TIA is defined as a neurological dysfunction lasting for less than 24 hours due to transient interruption of focal blood supply to brain, spinal cord or retina causing transient neurological signs and symptoms due to focal ischaemia without acute infarction.2

TIA can present with clinical symptoms corresponding to the arterial territory involved. Ocular ischaemia leads to partial or complete transient monocular visual loss. Hemispheric involvement may cause symptoms of contralateral homonymous hemianopia, hemiparesis or hemisensory loss.3 Severe carotid artery stenosis or occlusion often leads to haemodynamic TIAs, which occur with activities associated with relative hypotension, for example, orthostasis/hot bath. As the blood pressure drops the blood is no longer able to flow through the tight blood vessel in the neck and the ipsilateral half of the brain becomes hypoperfused. The hemispheric involvement in haemodynamic TIAs gives rise to symptoms such as jerking of the arm, which can easily be confused with a focal seizure.4 Timely diagnosis is crucial as this condition can be an indicator of severe carotid steno-occlusive disease.5

Case presentation

A woman in her 60s presented 2 years ago to our emergency department with a 2-month history of recurrent episodes of left arm shaking and dysarthria. The episodes of left arm spasm and shaking only happened on standing.

Her medical history included hypertension, type 2 diabetes, diabetic neuropathy, retinal cone dystrophy with some preserved central vision, ulcerative colitis, fibromyalgia and asthma.

The examination findings during her current episode included mild left arm and leg weakness with reduced sensation and slightly increased tone.

During her inpatient stay, she was noted to have a significant postural drop in her blood pressure, which was most likely due to her antihypertensive medications, the doses of which were reduced in the first instance and switched to night time. These were stopped altogether later on in the community.

Investigations

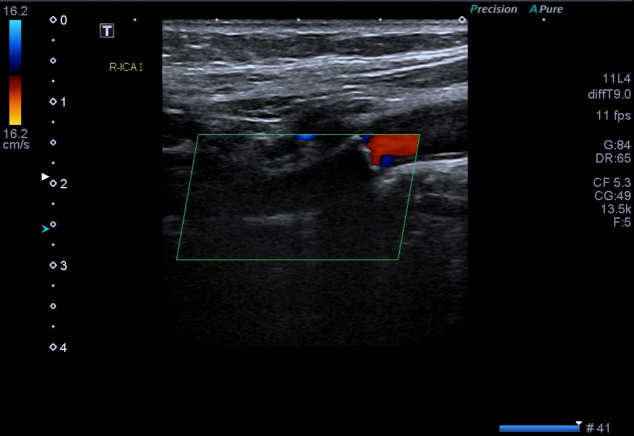

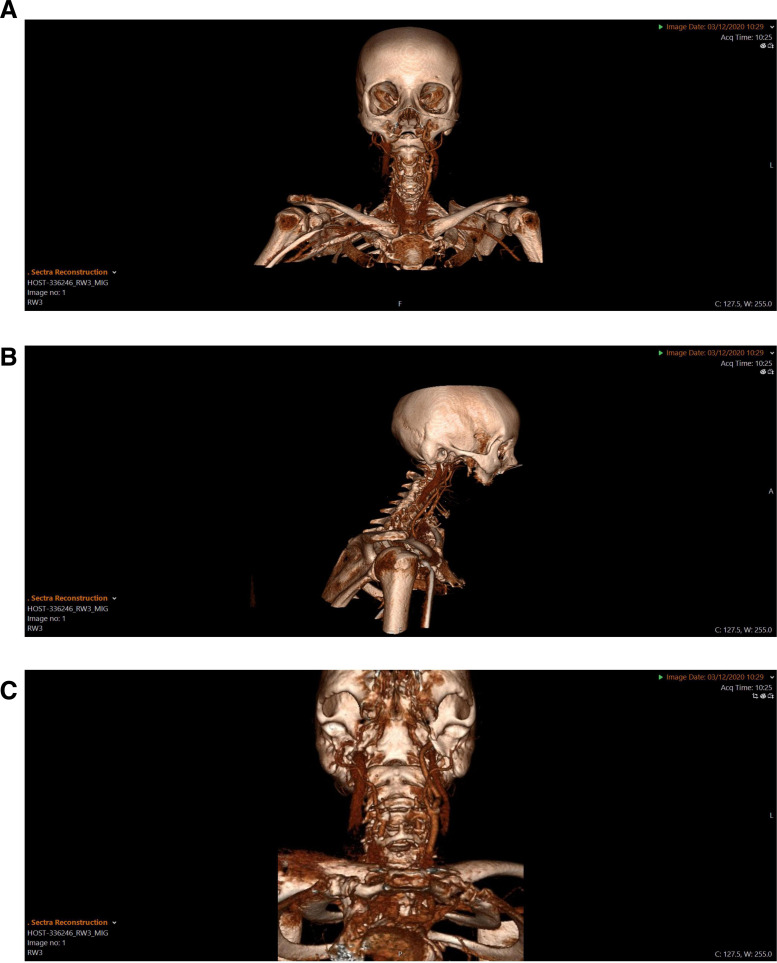

CT brain did not show any acute intracranial pathology. Although there was a background of inflammatory bowel disease, intracranial vascular imaging was not performed as there was no clinical marker of vasculitis. Furthermore, it was discovered on carotid Doppler studies that the right internal carotid artery (ICA) was now completely occluded and the left carotid artery was 50%–59% stenosed but patent distally (figure 1). The occluded carotid vessels were also visualised on CT angiogram of carotid arteries (figure 2A–C).

Figure 1.

Occluded right ICA on USS carotid Dopplers. ICA, internal carotid artery; USA, ultrasound.

Figure 2.

(A–C) : Occluded right ICA on CT angiogram of carotid vessels. ICA, internal carotid artery.

Differential diagnosis

The differentials of crescendo TIAs or poststroke focal seizures with speech arrest were considered given the symptoms.

Given the ongoing left-sided weakness and reduced sensation, the patient was diagnosed with a history of left arm shaking TIAs, caused by right hemispheric hypoperfusion due to postural hypotension and severely stenosed right ICA. These TIAs were followed by a right-sided lacunar stroke when the right ICA became completely occluded.

Treatment

The findings on carotid Doppler scan were discussed with vascular surgeons, and surgery was not deemed appropriate as the carotid artery responsible for her symptoms had now occluded and her left ICA stenosis was asymptomatic.

She was discharged on dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) for 2 weeks and then advised to continue on clopidogrel alone for secondary prevention.

Outcome and follow-up

At the time of follow-up after 6–8 weeks, she reported that she had not had any further limb shaking episodes since her discharge from the hospital.

Discussion

Limb shaking TIAs are unusual presentations of transient cerebral hypoperfusion and are usually associated with underlying severe carotid artery stenosis.6

This atypical presentation was first described by Fischer in 1962.7 TIAs are traditionally believed to present with negative symptoms such as loss of vision, sensation or limb power.8

According to Gálvez-Jiménez et al, limb-shaking syndrome (LSS) is considered to be one of the many secondary or symptomatic dyskinesias of vascular aetiology.9

Decreased cerebral blood flow in watershed territories due to critical carotid artery stenosis, which can be precipitated by orthostatism, is a plausible explanation for the symptoms. Focal limb shaking was noted to be a clinical feature in 12% of patients in an assessment by Bogousslavsky and Regli of 51 patients with watershed infarcts.10

The haemodynamic failure being the underlying cause of TIAs with limb shaking was further corroborated by another study in which positron emission tomography scan imaging revealed acetazolamide-induced hypoperfusion of the corresponding cerebral arteries in a patient with LSS.11 The most important underlying pathology which makes the early diagnosis of LSS even more crucial is severe carotid artery stenosis as this is a significant risk factor for stroke. This was noted to be present in all 12 patients described by Yanagihara et al.12

The management involves careful control of blood pressure with or without surgical revascularisation leading to improved cerebral blood flow. Clinical trials have shown evidence that dual antiplatelet therapy (clopidogrel plus aspirin) can be more effective strategy to prevent early recurrence in high-risk TIAs and should be started preferably within 24 hours of presentation unless contraindicated.13 14

Our patient was found to have occluded right ICA on an ultrasound Doppler scan when she presented with a stroke. Prior to this, she had been having left limb symptoms triggered by hypoperfusion of the right hemisphere due to postural hypotension. The careful alterations of antihypertensive medications led to significant improvement but by the time of her presentation with a stroke her right ICA had completely occluded and so carotid endarterectomy was not possible.

Learning points.

It is important to differentiate limb shaking transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) from other disorders presenting as shakes or tremors, a common example being focal epileptic seizures. Focal seizures usually present with movement of one side of the body or one specific body part.15

An accurate history of the sequence of events can be an important pointer towards the diagnosis. Hyperventilation, sepsis and missed antiepileptic medications may commonly trigger seizures but standing up suddenly will not. The stereotyped events that occur only on standing are very characteristic of limb shaking TIAs.

A timely diagnosis of a limb shaking TIA is crucial to prevent an ischaemic stroke which can occur as a result of underlying steno-occlusive disease of the carotid arteries. For example, in our patient, revascularisation surgery could have been offered it had been detected at the stage of stenosis rather than occlusion when it was not suitable for a surgical intervention.

Footnotes

Contributors: NM was responsible for designing and writing the manuscript. JK and CD were responsible for supervision, writing-review, editing of the manuscript. The consent from the patient was obtained by NM.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

References

- 1.Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Silver LE, et al. Population-Based study of event-rate, incidence, case fatality, and mortality for all acute vascular events in all arterial territories (Oxford vascular study). Lancet 2005;366:1773–83. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67702-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albers GW, Caplan LR, Easton JD, et al. Transient ischemic attack--proposal for a new definition. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1713–6. 10.1056/NEJMsb020987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karen LF MD. MPH. pathophysiology of symptoms from carotid atherosclerosis -UpToDate.com.

- 4.Brown MM. Identification and management of difficult stroke and TIA syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;70 Suppl 1:17i–22. 10.1136/jnnp.70.suppl_1.i17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das A, Baheti NN. Limb-Shaking transient ischemic attack. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2013;4:55–6. 10.4103/0976-3147.105615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baquis GD, Pessin MS, Scott RM. Limb shaking--a carotid TIA. Stroke 1985;16:444–8. 10.1161/01.STR.16.3.444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer CM. Concerning recurrent transient cerebral ischemic attacks. Can Med Assoc J 1962;86:1091–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nadarajan V, Perry RJ, Johnson J, et al. Transient ischaemic attacks: mimics and chameleons. Pract Neurol 2014;14:23–31. 10.1136/practneurol-2013-000782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gálvez-Jiménez N, Hanson MR, Hargreave MJ, et al. Transient ischemic attacks and paroxysmal dyskinesias: an under-recognized association. Adv Neurol 2002;89:421–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogousslavsky J, Regli F. Unilateral watershed cerebral infarcts. Neurology 1986;36:373. 10.1212/WNL.36.3.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumgartner RW, Baumgartner I. Vasomotor reactivity is exhausted in transient ischaemic attacks with limb shaking. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;65:561–4. 10.1136/jnnp.65.4.561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanagihara T, Piepgras DG, Klass DW. Repetitive involuntary movement associated with episodic cerebral ischemia. Ann Neurol 1985;18:244–50. 10.1002/ana.410180212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prasad K, Siemieniuk R, Hao Q, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for acute high risk transient ischaemic attack and minor ischaemic stroke: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ 2018;66:k5130. 10.1136/bmj.k5130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 2013;369:11–19. 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stafstrom CE, Carmant L. Seizures and epilepsy: an overview for neuroscientists. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2015;5. 10.1101/cshperspect.a022426. [Epub ahead of print: 01 Jun 2015]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]