Abstract

Introduction

The EMPACOL Project aims to investigate the link between healthcare professionals’ (HCPs) empathy and the results of the curative treatment of non-metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC).

Methods and analysis

EMPACOL will be an observational multicentric prospective longitudinal study. It will cover eight centres comprising patients with non-metastatic CRC, uncomplicated at diagnosis in two French areas covered by a cancer register over a 2-year period. As estimated by the two cancer registries, during the 2-year inclusion period, the number of cases of non-metastatic CRCs was approximately 480. With an estimated participation rate of about 50%, we expect around 250 patients will be included in this study. Based on the curative strategy, patients will be divided into three groups: group 1 (surgery alone), group 2 (surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy) and group 3 (neo-adjuvant therapy, surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy). The relationship between HCPs’ empathy at the time of announcement and at the end of the strategy, quality of life (QoL) 1 year after the end of treatment and oncological outcomes after 5 years will be investigated. HCPs’ empathy and QoL will be assessed using the patient-reported questionnaires, Consultation and Relational Empathy and European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire, respectively. A relationship between HCPs’ empathy and early outcomes, particularly digestive and genitourinary sequelae, will also be studied for each treatment group. Post-treatment complications will be assessed using the Clavien-Dindo classification. Patients’ anxiety and depression will also be assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale questionnaire.

Ethics and dissemination

The Institutional Review Board of the University Hospital of Caen and the Ethics Committee (ID RCB: 2022-A00628-35) have approved the study. Patients will be required to provide oral consent for participation. Results of this study will be disseminated by publication in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Gastrointestinal tumours, Quality in health care, Colorectal surgery

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Multicentre and prospective longitudinal design with a multidisciplinary research group to address functional sequelae, socio-territorial inequalities and empathy, as well as the impact of clinical and non-clinical factors on colorectal cancer.

Supervision of the cancer registry to ensure that the results are representative.

However, a Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) score threshold is lacking in the literature.

Additionally, the CARE score does not include an important dimension associated to empathy: the reassurance by healthcare professionals to patients that they will do their very best for them.

Temporal and spatial heterogeneity between clinical information and questionnaire completion is another limitation.

Introduction

Epidemiology of colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains a public health problem. There were an estimated 43 336 new cases of CRC in France in 2018. This makes it, among solid tumours, the third most common cancer in men and the second most common in women. With 17 117 deaths in 2018, CRC is the second leading cause of cancer death in men and the third leading cause of death in women. The prognosis of CRC has improved significantly over the past 20 years.1 2 For patients with colon cancer (CC), a 5-year survival rate ranges from 92% for stage I to 11% for stage IV. The multidisciplinary strategy for rectal cancer (RC) has been shown to reduce the 5-year local recurrence rate to less than 10%, and increase the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate beyond 50%.3

CRC management

Although the term ‘colorectal cancer’ is commonly used, both multimodal treatment and functional sequelae are not the same for CC and RC.4 For forms that are neither metastatic nor locally complicated (non-haemorrhagic, without occlusion or perforation) at the time of diagnosis, surgical oncological resection (colectomy or proctectomy) represents the cornerstone of treatment with curative intent.5 As suggested by recent French guidelines,6 surgery is preceded by neoadjuvant treatment for locally advanced subperitoneal RC. Adjuvant chemotherapy (ADJ CT) is recommended in case of lymph node involvement (stage III) or vascular/lymphatic invasion, perinerve or tumour budding. The short-term outcome of surgical resection is generally reported by mortality rates and morbidity using the Clavien-Dindo classification score assessed on the 90th postoperative day.7 Since the 2000s, the 3-month mortality of patients with CRC, regardless of surgical treatment, has decreased significantly from 15.8% to 11.3%.8

Both OS and recurrence-free survival are usually the parameters for assessing long-term oncological outcomes. Although OS has increased significantly over time in all European regions,9 the 5-year OS rate for both CC and RC depends on lymph node status and cancer stage.10

Due to the significant improvement in prognosis, the functional dimension of CRC treatment has now become inseparable from carcinological imperatives.11 Historically, functional sequelae have long been considered inherent to the carcinological nature of the surgical resection and are hardly avoidable. While prevalence and predictive factors are different depending on colonic or rectal location,12 functional sequelae (ie, digestive and/or genitourinary sequelae) may significantly impair their quality of life (QoL).

Quality of life

While QoL remains a priority among CRC treatment outcomes, as outlined in Axis 2 of the latest 10-year strategy 2021–2030 PLAN CANCER FRANCE, little is known regarding the evolution of QoL over time in patients operated on for CRC.13 Most QoL scores drop significantly in the early postoperative period. Surgery, especially total mesorectal excision in RC, significantly reduced patients’ QoL.12 Of all digestive cancer removals, proctectomy for RC carries the greatest risk of functional sequelae and impaired QoL.

Among the functional sequelae observed, the definitive stoma in case of abdominoperineal excision and digestive sequelae in sphincter conservation represent the two main risk factors that potentially alter QoL.

Globally, patients with CC have less disabling outcomes compared with patients who have undergone RC surgery.4 Many side effects are reported in case of ADJ CT. Some toxicities persist after discontinuation of treatment, which may result in changes in patients’ QoL.

Role of empathy in care

In human sciences and even clinical settings, the precise definition of empathy is a subject of ongoing academic debate.14–16 Empathy is often considered one dimensional, but recent work has demonstrated that a multidimensional view of the concept is also conceivable in oncology.17 18 Empathy is considered essential for the building and continuation of the therapeutic patient–healthcare professional (HCP) relationship.

In a clinical setting, empathy involves an ability to19:

Understand the patient’s situation, perspective and feelings

Communicate this understanding and verify its accuracy.

Act on this understanding with the patient in a helpful way (joint planning of an optimal therapeutic strategy).

A systematic literature review suggested a positive association between HCPs’ empathy and a variety of positive cancer patient outcomes,20 including increased satisfaction with care and treatment adherence, decreased psychological distress and improved QoL. Patient perception of physician empathy is largely explained by patient and clinical variables.21 Unmet patient needs are strongly and negatively associated with low perceived empathy.

Empathy must be evaluated during several key moments of the care pathway to study the trajectories of perceived empathy and link between these trajectories and the outcomes of interest. For example, patients with CRC requiring first-line CT present with major concerns at the time of the CT education session as compared with patients with other tumour forms.22

The sole retrospective study, which examined the link between empathy and survival in oncology, found discordant results, depending on when empathy was assessed.23

To the best of our knowledge, no prospective study has specifically examined the relationship between patient-perceived empathy at each stage of a treatment sequence and CRC outcomes.

Hypothesis and objectives

The main objective of the EMPACOL Project is to investigate, in patients with non-metastatic CRC, a possible correlation between patients’ perception of HCPs’ empathy and survival (OS and disease-free survival (DFS)).

The secondary objective of this study is to evaluate the relationship between patients’ perception of HCPs’ empathy and QoL and morbidity and mortality in patients treated for curative non-metastatic CRC.

We expect to find a negative correlation between HCPs’ perceived empathy and morbidity/mortality and a positive correlation between empathy and an improvement in both functional outcome and QoL 1 year after treatment.

Additionally, we seek to verify if a positive correlation exists between patients’ perceived empathy and survival rate (OS, DFS) 5 years after completion of treatment received.

Methods and analysis

Study design

EMPACOL is a descriptive, longitudinal and multicentre prospective project in two French areas covered by a cancer registry. The project was approved by the French Committee for the Protection of Persons (CPP; no RCB: 2022-A00628-35).

All investigators will conduct this study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Eight CRC centres, including both university hospitals and cancer centres, have agreed to include 50–100 patients who will receive curative treatment between 01 January 2023 and 01 January 2025, with the aim of conducting and reporting multicentre studies on the theme of patients’ perception of HCPs’ empathy, QoL and survival.

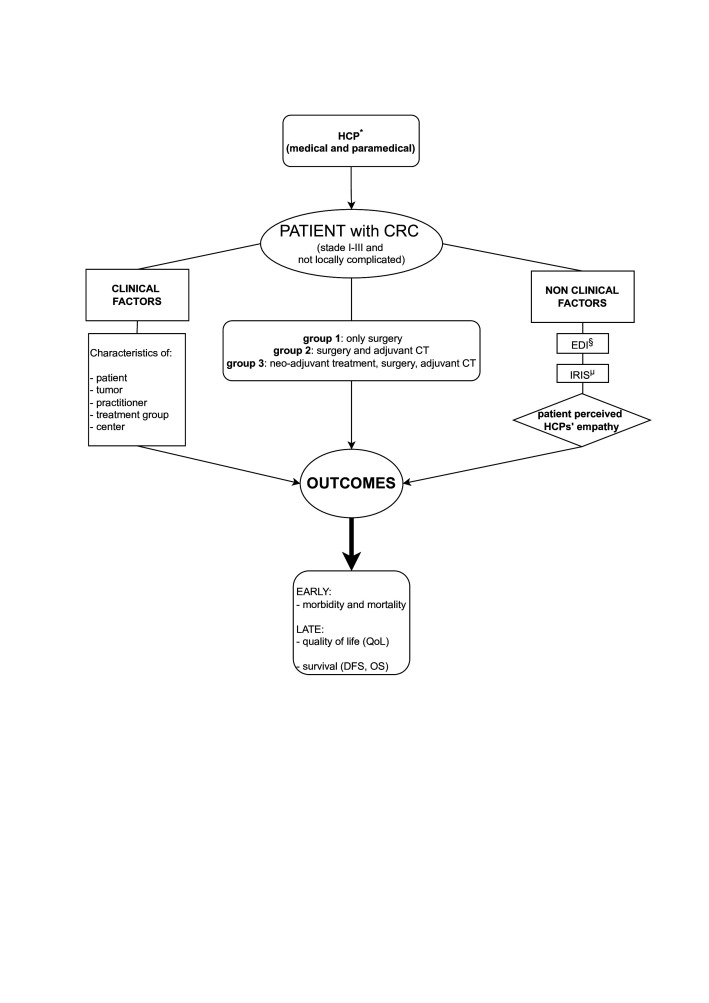

Taking into consideration clinical factors, EMPACOL will evaluate, among non-clinical factors, using the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) questionnaire, the impact of patient-perceived empathy on short-term (medical-surgical morbidity of each therapeutic step) and long-term outcomes (QoL, DFS and OS) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the factors evaluated. Taking into consideration clinical factors, EMPACOL evaluates, among non-clinical factors, using the CARE questionnaire, the impact of patient-percevied empathy on short-term (medical-surgical morbidity of each therapeutic step) and long-term outcomes (QoL, DFS and OS). CARE, Consultation and Relational Empathy; CRC, colorectal cancer; CT, chemotherapy; DFS, disease-free survival; EDI, European Deprivation Index; HCP, healthcare professional; IRIS, Ilots Regroupés pour L'Information Statistique; OS, overall survival; QoL, quality of life.

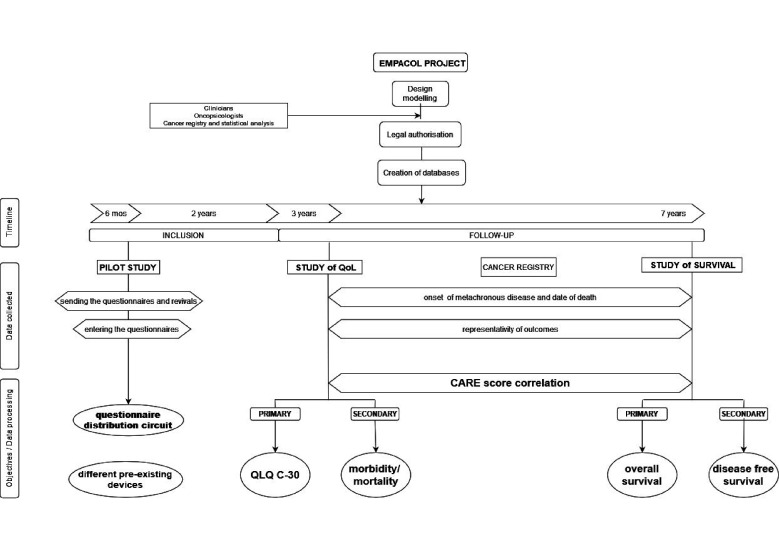

To anticipate and respond to the questions and issues that will be encountered in the EMPACOL Project and future studies, we plan to design a prospective multicentre pilot study (figure 2). This pilot study will be integrated into the EMPACOL Project.

Figure 2.

The EMPACOL Study design. The EMPACOL Project aims to investigate the correlation between the CARE score and QoL at 6 months and 1 year after the end of the therapeutic strategy (secondary objective) and the oncological results in case of metachronous metastatic disease and on the overall survival at 5 years of patients treated with curative intent for stage I–III CRC (primary objective). EMPACOL will start with a pilot study that will allow to study the optimal circuit for the delivery of the questionnaires and to identify the pre-existing systems put in place by the different centres. CARE, Consultation and Relational Empathy; CRC, colorectal cancer; QLQ-C30, Core Quality of Life Questionnaire; QoL, quality of life.

Patients will be included prospectively over a 6-month period. The pilot study aims to find a link between the circuit of the questionnaire adopted by the centre and the response rate to the questionnaires. Factors that may influence the response rate will also be assessed.

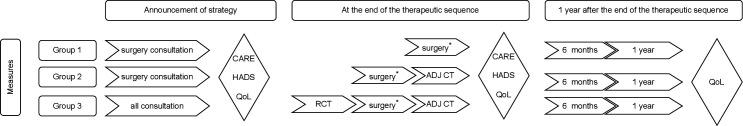

The proposed questionnaire circuit hypothesises that the patients of groups 1 and 2 will evaluate patients’ perception of HCPs’ empathy after the surgical consultation and patients of group 3 will evaluate patients’ perception of HCPs’ empathy once the patient has met the medical and paramedical team (oncologist, radiotherapist and surgeon) or once the therapeutic sequence has been validated through a multidisciplinary consultation. A subsequent measurement of patients’ perception of HCPs’ empathy will be carried out at the end of the therapeutic sequence. Each assessment of patients’ perception of HCPs’ empathy will be associated with an assessment of the patient’s state of anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Proposed questionnaire distribution circuit. For group 1 and group 2 patients, the first CARE assessment is performed after the surgical consultation. For patients in group 3, after having met all the medical and paramedical staff, a second CARE score measurement will be performed at the end of the therapeutic sequence. Each CARE score measurement will be associated with an evaluation of the patient’s state of anxiety and depression (HADS questionnaire) and QoL (QLQ-C30). RCT (radiochemotherapy); ADJ CT, adjuvant chemotherapy; CARE, Consultation and Relational Empathy; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; QLQ-C30, Core Quality of Life Questionnaire; QoL, quality of life.

We expect member centres to indicate when the proposed procedure will pose difficulties in terms of filling, delivery or collection of patient-reported questionnaires to optimise and streamline the following stages of the EMPACOL Project.

For the three therapeutic groups, QoL and patients’ perception of HCPs’ empathy will be simultaneously evaluated at the time of announcing the strategy. The QoL will be reassessed on the 90th postoperative day for group 1 and at the end of the ADJ CT for groups 2 and 3. Regardless of the therapeutic group, the QoL will be reassessed at 6 months and 1 year after the end of treatment (figure 3). We will examine the link between patients’ perception of HCPs’ empathy and 5-year OS and the occurrence of local recurrence or metastatic pathology (DFS; primary objective). Moreover, we will study the link between patients’ perception of HCPs’ empathy and postoperative morbidity/mortality and QoL (secondary objective).

Morbidity/mortality will be evaluated at the end of the therapeutic strategy. The most severe complication will be considered in the analyses (figure 2). The disease will be considered as metachronous in case of tumour recurrence occurring 6 months after the diagnosis.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria will be as follows: patients aged 18–80 years, who are French speaking, who are affiliated to a social security system and who have received a detailed description of the study. Furthermore, the patients must be diagnosed with non-metastatic and uncomplicated CRC (without occlusion/perforation/bleeding), require elective therapeutic management and not have expressed an unfavourable opinion to participate. The participants must provide their oral consent at the time of consultation, where the proposed treatment strategy will be detailed, along with the delivery of questionnaires.

Written consent will not be required from participants (non-interventional research (NIR)/MR-003–declaration number 2011519 V0). We will include patients who have a cognitive state capable of understanding and completing the questionnaires (autonomous completion).

Exclusion criteria

We will exclude patients who are minors or older than 80 years, residing in a department outside Calvados or Manche, presenting with a CRC other than adenocarcinoma and all metastatic forms or requiring emergency surgery (perforation, haemorrhage, occlusion), undergoing exclusive endoscopic treatment or with a missed CRC discovered after surgery for non-oncological indications.

Additionally, we will exclude patients with another neoplastic disease under treatment and/or evolving, a history of inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis), hereditary diseases predisposing to CRC (Lynch syndrome, familial polyposis) and severe cognitive impairment preventing proper comprehension of the questionnaires. Furthermore, pregnant women will be excluded.

Endpoints and measures

Empathy

Patient-perceived empathy will be assessed using the CARE questionnaire that has been validated in cancer care.17 This is a self-reported 10-point questionnaire with a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from ‘poor’ to ‘excellent’. It has excellent psychometric properties with α=0.92. High scores indicate a higher perception of HCPs’ empathy. Three distinct empathic processes will also be considered: ‘rapport’ (items 1–3), ‘emotional process’ (items 4–6) and ‘cognitive process’ (items 7–10).

Quality of life

QoL will be evaluated using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-C30), which is equivalent to other tools, such as the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index, in terms of emotional function, but superior in terms of social function.24 The use of an additional tool is recommended for the assessment of depression in patients with CRC.25

Patient anxiety and depression

This parameter will be evaluated with the HADS.26 The HADS assesses both symptoms of anxiety and depression, which commonly coexist.

Morbidity and mortality

The severity of medical and surgical complications will be assessed using the Clavien-Dindo grading system.7 Grades I and II complications involve only pharmacological treatment, while grades III, IV and V require surgical, endoscopic or radiological treatment. Complications below grade III will be considered ‘minor complications’, while complications above and including grade III will be considered ‘major complications’, as reported in the literature. For the three groups, postoperative morbidity and mortality will be assessed at 90 postoperative days (C/D90). C/D90 will be associated with the morbidity and mortality of the other therapeutic stages, post-adjuvant treatment for group 2 (C/DADJ) and post-neoadjuvant treatment for group 3; it will also be associated with C/DADJ.

Survival and representativeness of the data collected

All patients diagnosed with CRC during the inclusion period will be included in two specialised digestive cancer registries of Northwest France, members of the French network of cancer registries, departments of Calvados and Manche. The resident population of these well-defined administrative areas was 1 601 928 inhabitants in 2016. Both digestive cancer registries included in the present study have collected exhaustive information on treatments and stage in the framework of the high-resolution study. These registries have worked together for many years and use identical standardised data collection, recording and validation procedures. Multiple information sources ensure exhaustive collection of study variables. The databases are declared to the National Commission on Information Technology and Civil Liberties. The quality of the data collected is evaluated every 4 years by ‘Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale’, ‘Santé Publique France’ and ‘Institut National du Cancer’.

Data collection

Sociodemographic and medical information will include gender, age (<60 years, 60–69 years, 70–75 years), education level, marital status, obesity (body mass index >30), active smoking and alcohol use, the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification system (I–II vs III–IV), anxious and depressive states (HADS score) of the patient and presentation during the multidisciplinary team meeting, histology and tumour differentiation (grades I, II and III), surgical approach (laparotomy and/or laparoscopy or robotic), neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatments (type and number of sessions), and site of the primary tumour (colon vs rectum). The forms located at the rectosigmoid junction will be included in the colonic localisation.

Socioeconomic status will be defined using the European Deprivation Index, which is an ecological and composite indicator included in the census of the European Union’s statistics on income and living conditions. For all cases, patient addresses will be geolocalised using the geographical information system (ArcGIS V.10.2) and assigned to an ‘Ilots Regroupés pour L'Information Statistique’ (IRIS), a geographical area defined by the ‘Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques’. IRIS is the smallest geographical unit in France, for which census data are available.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables will be expressed as mean±SD, and qualitative variables will be expressed as number of patients and percentages. Regardless of the therapeutic group, the experimental design of the study allows for several measurements to be performed in the same individual during their oncological care and follow-up. Comparisons between the mean scores of the three treatment groups will be made using an analysis of variance or a Kruskal-Wallis test, depending on whether the data follow the hypothesis of tested homoscedasticity. Post hoc comparisons will be performed with the Bonferroni correction or Nemenyi test.

The sensitivity and specificity of the CARE score in predicting impact on QoL will be assessed by receiver operating characteristic curves for the score versus groups reporting no/minor or definite/major impact on QoL.

The correlation between the validated CARE questionnaire and the QLQ (EORTC QLQ-C30) will be estimated with Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients and their 95% CI.

The inclusion of data indicating the impact of CARE on QoL will be based on a univariate approach and then a multivariate approach using ad hoc models depending on the nature of the dependent variable (binary or multinomial logistic regression or linear regression depending on whether the QoL score is considered qualitative or quantitative). Only variables with p≤0.20 in the univariate analysis will be included in the multivariate model. This approach will allow the identification of risk factors related to the deterioration of QoL and assessment of their impact. All tests will be two tailed with a significance level (p value) equal to 0.05.

We will use the Kaplan-Meier method to obtain survival curves and a Cox model to assess the impact of CARE score on survival in the three different groups. HRs will be calculated, using semiproportional Cox hazard models, to assess the effect of the CARE score on survival in patients with non-metastatic, uncomplicated CRC. The proportional hazard hypothesis will be tested (Schoenfeld’s residuals). Variables whose threshold p value is ≤0.20 in the univariate analysis (M0) will be included in the multivariate model (M1). The variable of interest (CARE score) will be used in all models.

All statistical analyses will be performed using Stata V.SE14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Feasibility

We chose to include patients who had undergone curative treatment over a 2-year period for two reasons: the first is physiological, to allow their bowel function to become stable. The second is oncological, to detect local recurrence and/or distant metastases. Consistent with recent literature, we considered differentiating the study population into two groups: those with high perceived empathy (maximum CARE score, which is often the modal value in cancer care) and those without.

We calculated with BiostaTGV that approximately 90 patients in each group, thus 180 in total, would be needed to show clinically significant improvement in QoL or reduction in morbidity with high CARE score (power β=80% and risk α=0.05 bilaterally).

From the two cancer registries, we know that over the 2-year inclusion period, the number of non-metastatic CRCs is approximately 480 cases. With an estimated participation rate of about 50%, we expect around 250 patients will be included in this study.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public have not been involved in the design, recruitment or conduct of the study. The results will be disseminated to study participants and to the physicians who included them in the study.

Ethics and dissemination

The Institutional Review Board of the University Hospital of Caen and the Ethics Committee (CPP Nord Ouest I, June 2022; ID RCB: 2022-A00628-35) have approved the study.

Patients will be informed orally (according to NIR/MR-003—declaration number 2011519 V0) of the purpose of the research and the course and duration of the study and will provide oral consent. They will be able to exercise their right to withdraw at any time. The medical procedures of this study are in accordance with the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Law No 2012-300 of 5 March 2012, and its application decree no 2016-1537 of 16 November 2016. In accordance with the Data Protection Act and Law No 2002-303 of 4 March 2002, the patient may exercise their right to access and rectify the data collected at any time.

Any modification of the protocol will have to be approved by the CPP. The automated processing of health data complies with the European Regulation of 27 April 2016, on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data. The coordinating investigator of the study undertakes to keep the source documents for a period of 15 years.

Results of this study will be disseminated by publication in peer-reviewed professional and scientific journals. Participant data will be kept confidential and will not be shared with the public. If there are requests for data sharing for appropriate research purposes, this will be considered on an individual basis after study completion and after the publication of the primary manuscripts.

Discussion

The prognosis of CRC has improved significantly over the past 20 years.1 2 Oncological principles,27 the development of minimally invasive techniques,28 and advances in diagnostic accuracy29 are strongly linked to these outcomes and well described in the recent literature. However, many surviving patients experience functional sequelae (ie, digestive and/or genitourinary sequelae) that significantly impair their QoL. Both prevalence and predictive factors are different depending on colonic or rectal location.12

Functional disorders occur frequently following surgery for CC. The incontinence of liquid and solid stool is 24.1% and 6.9%, respectively. The most common symptom associated with constipation is incomplete and difficult evacuation in about one-third of cases.4 Major low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) is present in 21.1% of patients.4 No difference is reported in the prevalence of symptoms according to the type of colectomy.4 12 In their systematic review and meta-analysis, Verkuijl et al included 8418 partial colectomies (4207 right hemicolectomies and 4211 left hemicolectomies/sigmoid colon resection, respectively) and 161 subtotal/total colectomies and concluded that bowel function problems following CC surgery are common, do not improve over time and are not dependent on the type of surgery.4

For RC, low rectal resections30 and neoadjuvant radiotherapy31 are known to severely impair bowel function. Up to 80% of patients with RC undergo sphincter-preserving surgery,32 without impairing oncological prognosis.6 33 Between 50% and 90% of these patients will experience a change in their bowel habits afterwards.34 35 Eid et al found that 65.2% of RC survivors had bowel dysfunction, including 41.3% with major LARS and 80% with genitourinary dysfunction.12 In addition to the psychological burden related to the tumour pathology and concern about the probability of recovery, it is important to consider the patient’s experience of the functional results and its repercussions in terms of QoL, especially in case of complications or poor functional results. One of the worst fears related to surgery is the creation of an ostomy.

Problems related to stoma care, or impaired genitourinary or digestive function are likely to have an impact on the QoL of patients with CRC.

Patients’ perceived unmet rehabilitation needs during the course of their tumour pathology are associated with decreased QoL. Interventions to reduce perceived rehabilitation needs of patients with cancer may improve QoL.

Among non-medical factors, other than socioeconomic and geographical inequalities, rural ostomy patients reported more care-related problems and lower QoL.36

A 2012 review of the literature suggested links between HCPs’ empathy and various positive cancer patient outcomes, such as improved QoL or increased satisfaction with care.20 Assessment modalities for measuring empathy in medical settings are heterogeneous.20

The associations between the severity of medical and surgical complications and the perception of surgeon empathy have been studied in patients with oesophageal and gastric cancer.18 When patients perceived high empathy, they were less likely to report major complications.18 Of the three dimensions, ‘rapport building’ and ‘emotional process’ were predictive of major complications. Physician empathy is essential before surgery. It is therefore important to consider the patient’s experience.

Thanks to the CARE tool, the EMPACOL Project will allow us to evaluate patients’ perceptions of medical and paramedical staff’s empathy throughout their care, particularly in the case of complications related to the treatment and its impact in terms of early and late results.

HCPs need to be trained to establish a good relationship with patients, from the time of treatment announcement through the period of oncological surveillance. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms linking empathy to CRC management outcomes.

To this end, this pilot study will allow us to identify the best channel for distributing the questionnaires, study the clinical and non-clinical factors that may influence respondent and non-respondent rates, and identify a correlation with short-term outcomes in each therapeutic group.

Strengths of the project

First, it is the first project to study a correlation between empathy and survival in an oncology setting, using a score translated and validated in the French language. Second, the multicentre, prospective and longitudinal design makes this a comprehensive study to evaluate empathy and survival in patients with CRC. Third, the multidisciplinarity of the research group addresses functional sequelae, socio-territorial inequalities and empathy, and evaluates the impact of clinical and non-clinical factors in CRC. Fourth, the cancer registry will ensure the representativeness of the results.

Limitations of the project

(1) The lack of a CARE score threshold in the literature; (2) the temporal and spatial heterogeneity between clinical information and questionnaire completion; (3) the absence of a specific assessment of the patient’s experience with uncertainty and negative events during management, such as tumour progression or treatment-related complications, in the CARE score.

Conclusion

The results of the pilot study will therefore help refine the methodological tools that will be used in the EMPACOL Project, which aims to find a correlation between the CARE score and long-term outcomes (QoL and survival). The representativeness of the data collected and results of the EMPACOL Project will be studied under the supervision of the cancer registries that cover the two departments considered for patient inclusion.

Repeated measurements of perceived empathy, in relation to the treatment received, in the same individual and a follow-up of their evolution over time will make it possible to understand how to facilitate learning, encourage its practice in daily clinical attitudes and promote the development of empathy in the training of all actors in the caregiver–patient relationship. Obtaining and validating an empathy score, thanks to future studies, will allow a better appreciation of the role of all non-clinical factors in the results in the oncological environment and will open the way to other typologies of cancer.

This project is original as it goes beyond the impact of clinical factors in the outcomes of curative treatment of CRC. The multidisciplinary collaboration and cross-cutting competencies within our research group, functional sequelae, socio-territorial inequalities and empathy will help us better understand the impact of non-medical factors and role of empathy in the curative treatment of CRC. The prospective and longitudinal nature of this project will allow us to comment on the representativeness of the data collected and results obtained.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @CHU_Caen

Contributors: Study concept and design—AM, SL, DG and OD. Intervention design—SL, VB, SB, JG, DG, RM, AA and AM. Analysis of data will be done by AM, OD and RM. AM drafted the work, which was revised critically for intellectual content by SL and DG. All authors gave final approval of this version to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1374–403. 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:177–93. 10.3322/caac.21395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cottet V, Bouvier V, Rollot F, et al. Incidence and patterns of late recurrences in rectal cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:520–7. 10.1245/s10434-014-3990-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verkuijl SJ, Jonker JE, Trzpis M, et al. Functional outcomes of surgery for colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2021;47:960–9. 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.11.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Labianca R, Nordlinger B, Beretta GD, et al. Primary colon cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, adjuvant treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2010;21 Suppl 5:v70–7. 10.1093/annonc/mdq168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakkis Z, Manceau G, Bridoux V, et al. Management of rectal cancer: the 2016 French guidelines. Colorectal Dis 2017;19:115–22. 10.1111/codi.13550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 2009;250:187–96. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iversen LH, Ingeholm P, Gögenur I, et al. Major reduction in 30-day mortality after elective colorectal cancer surgery: a nationwide population-based study in Denmark 2001-2011. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:2267–73. 10.1245/s10434-014-3596-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner H, Bouvier AM, Foschi R, et al. Progress in colorectal cancer survival in Europe from the late 1980s to the early 21st century: the EUROCARE study. Int J Cancer 2012;131:1649–58. 10.1002/ijc.26192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunderson LL, Jessup JM, Sargent DJ, et al. Revised Tn categorization for colon cancer based on national survival outcomes data. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:264–71. 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.0952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alves A. [Recommendations for clinical practice. Therapeutic choices for rectal cancer. How can we reduce therapeutic sequelae and preserve quality of life?]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2007;31 Spec No 1:S95–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eid Y, Bouvier V, Menahem B, et al. Digestive and genitourinary sequelae in rectal cancer survivors and their impact on health-related quality of life: Outcome of a high-resolution population-based study. Surgery 2019;166:327–35. 10.1016/j.surg.2019.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt CE, Bestmann B, Kuchler T, et al. Impact of age on quality of life in patients with rectal cancer. World J Surg 2005;29:190–7. 10.1007/s00268-004-7556-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall JA, Schwartz R, Duong F, et al. What is clinical empathy? perspectives of community members, university students, cancer patients, and physicians. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104:1237–45. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders JJ, Dubey M, Hall JA, et al. What is empathy? oncology patient perspectives on empathic clinician behaviors. Cancer 2021;127:4258–65. 10.1002/cncr.33834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Håkansson Eklund J, Summer Meranius M. Toward a consensus on the nature of empathy: a review of reviews. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104:300–7. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gehenne L, Lelorain S, Anota A, et al. Testing two competitive models of empathic communication in cancer care encounters: a factorial analysis of the care measure. Eur J Cancer Care 2020;29:e13306. 10.1111/ecc.13306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gehenne L, Lelorain S, Eveno C, et al. Associations between the severity of medical and surgical complications and perception of surgeon empathy in esophageal and gastric cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2021;29:7551–61. 10.1007/s00520-021-06257-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mercer SW, Reynolds WJ. Empathy and quality of care. Br J Gen Pract 2002;52 Suppl:S9–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lelorain S, Brédart A, Dolbeault S, et al. A systematic review of the associations between empathy measures and patient outcomes in cancer care. Psychooncology 2012;21:1255–64. 10.1002/pon.2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lelorain S, Brédart A, Dolbeault S, et al. How does a physician's accurate understanding of a cancer patient's unmet needs contribute to patient perception of physician empathy? Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:734–41. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oguchi M, Jansen J, Butow P, et al. Measuring the impact of nurse cue-response behaviour on cancer patients' emotional cues. Patient Educ Couns 2011;82:163–8. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lelorain S, Cortot A, Christophe V, et al. Physician empathy interacts with breaking bad news in predicting lung cancer and pleural mesothelioma patient survival: timing may be crucial. J Clin Med 2018;7:364. 10.3390/jcm7100364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwenk W, Neudecker J, Haase O, et al. Comparison of EORTC quality of life core questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-C30) and gastrointestinal quality of life index (GIQLI) in patients undergoing elective colorectal cancer resection. Int J Colorectal Dis 2004;19:554–60. 10.1007/s00384-004-0609-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aminisani N, Nikbakht H, Asghari Jafarabadi M, et al. Depression, anxiety, and health related quality of life among colorectal cancer survivors. J Gastrointest Oncol 2017;8:81–8. 10.21037/jgo.2017.01.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skarstein J, Aass N, Fosså SD, et al. Anxiety and depression in cancer patients: relation between the hospital anxiety and depression scale and the European organization for research and treatment of cancer core quality of life questionnaire. J Psychosom Res 2000;49:27–34. 10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00080-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodríguez-Luna MR, Guarneros-Zárate JE, Tueme-Izaguirre J. Total mesorectal excision, an erroneous anatomical term for the gold standard in rectal cancer treatment. Int J Surg 2015;23:97–100. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.09.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crippa J, Grass F, Dozois EJ, et al. Robotic surgery for rectal cancer provides advantageous outcomes over laparoscopic approach: results from a large retrospective cohort. Ann Surg 2021;274:e1218–22. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu G, Wu Z, Lui S, et al. Advances in imaging modalities and contrast agents for the early diagnosis of colorectal cancer. J Biomed Nanotechnol 2021;17:558–81. 10.1166/jbn.2021.3064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keane C, Wells C, O'Grady G, O’Grady G, et al. Defining low anterior resection syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. Colorectal Dis 2017;19:713–22. 10.1111/codi.13767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Croese AD, Lonie JM, Trollope AF, et al. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of low anterior resection syndrome and systematic review of risk factors. Int J Surg 2018;56:234–41. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chau A, Maggiori L, Debove C, et al. Toward the end of abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer? an 8-year experience in 189 consecutive patients with low rectal cancer. Ann Surg 2014;260:801–6. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rullier E, Laurent C, Bretagnol F, et al. Sphincter-Saving resection for all rectal carcinomas: the end of the 2-cm distal rule. Ann Surg 2005;241:465–9. 10.1097/01.sla.0000154551.06768.e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bryant CLC, Lunniss PJ, Knowles CH, et al. Anterior resection syndrome. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e403–8. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70236-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ziv Y, Zbar A, Bar-Shavit Y, et al. Low anterior resection syndrome (LARS): cause and effect and reconstructive considerations. Tech Coloproctol 2013;17:151–62. 10.1007/s10151-012-0909-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Näverlo S, Gunnarsson U, Strigård K. Rectal cancer patients from rural areas in northern Sweden report more pain and problems with stoma care than those from urban areas. Rural Remote Health 2021;21:5471. 10.22605/RRH5471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.