Summary

Metabolic syndrome, also as known as Syndrome X or Insulin Resistance Syndrome, is a complex health problem featuring visceral obesity (the main diagnostic criterion), insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and high blood pressure. Currently, this health condition has gained a momentum globally while raising concerns among health-related communities. The World Health Organization, American Heart Association and International Diabetes Federation have formulated diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome. Diet and nutrition can influence this syndrome: for example, the Western diet is associated with increased risk of metabolic syndrome, whereas the Nordic and Mediterranean diets and the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension are potentially beneficial. The Mediterranean diet can affect the components of metabolic syndrome due to its high dietary fiber, omega 3 and 9 fatty acids, complex carbohydrates, antioxidants, minerals, vitamins and bioactive substances, such as polyphenols. These nutrients and bioactive substances can combat obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension and diabetes mellitus. The mechanisms by which they do so are generally related to oxidative stress, inflammation (the most common risk factors for metabolic syndrome) and gastrointestinal function. The literature also shows examples of positive effects of the Mediterranean diet on the metabolic syndrome. In this review of the literature, we shed light on the effects, mechanisms and dynamic relationship between the Mediterranean diet and metabolic syndrome.

Keywords: Mediterranean diet, Metabolic syndrome, Effect mechanisms

Citation

How to cite this article: Dayi T, Ozgoren M. Effects of the Mediterranean diet on the components of metabolic syndrome. J Prev Med Hyg 2022;63(suppl.3):E56-E64.https://doi.org/10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2022.63.2S3.2747

Definition of metabolic syndrome

Metabolic syndrome, also known as Syndrome X or Insulin Resistance Syndrome is a complex abnormality associated with coronary artery disease [1]. Visceral obesity (abdominal obesity/android type obesity), insulin resistance (IR), hypertension and dyslipidemia are components of this cluster of metabolic problems [2]. There are many diagnostic criteria that have been developed by different organizations (Tab. I). Visceral obesity is the basic diagnostic criterion of metabolic syndrome and is associated with generalized low-level inflammation, accompanied by elevated serum concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alfa (TNF-α), which can decrease insulin sensitivity in human tissues. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are known to affect negatively blood pressure hemostasis and lipid metabolism. Besides low-grade inflammation, visceral obesity is commonly related to overnutrition. A positive energy balance has some long-term comorbidities such as IR and coronary artery disorders. This explains why visceral obesity is the main diagnostic criterion of metabolic syndrome [2-4]. Other common complications include stroke, myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus [5].

Tab. I.

Diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome according to various health organizations.

| Organization | Visceral obesity | TAG | HDL | Blood pressure (BP) | Fasting plasma glucose | Other | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

• World Health Organization (WHO) • Diabetes, IR or impaired glucose tolerance PLUS two or more other criteria. |

Body mass index > 30 kg/m2 Waist hip ratio For males > 0.9 For females > 0.85 |

≥ 150 mg/dL |

For males < 35 mg/dL For females < 39 mg/dL |

≥ 140/90 mmHg | Impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes and/or IR |

Microalbuminuria Urinary albumin excretion rate ≥ 20 μg/min Albumin creatine ratio ≥ 30 μg/mg |

WHO [18] |

|

– International Diabetes Federation (IDF) – Visceral obesity PLUS two or more other criteria. |

Waist circumference Defined with ethnic-specific values |

≥ 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or specific treatment for this abnormality |

For males < 40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L) For females < 50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/L) or specific treatment for this abnormality |

Systolic BP ≥ 130 mmHg or Diastolic BP ≥ 85 mmHg or treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension |

≥ 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or previously diagnosed with type II diabetes |

- | IDF [19] |

|

- American Heart Association (AHA) - At least three criteria. |

Waist circumference For males ≥ 102 cm (≥40 inches) For females ≥ 88 cm (≥ 35 inches) |

≥ 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or specific treatment for this abnormality |

For males < 40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L) For females < 50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/L) or specific treatment for this abnormality |

Systolic BP ≥ 130 mm Hg or Diastolic BP ≥ 85 mmHg or treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension |

≥ 100 mg/dL or specific treatment for this abnormality |

- | Grundy et al. [20] Alberti et al. [21] AHA [22] |

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome differs between countries. Aguilar et al. [6] reported a 33% overall prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the United States of America (USA) in 2012. Liang et al. [7] reported a 38.3% prevalence in 2018. In 2017, prevalence was 48.8% in Qatar [8] and 42.87% in Iran [9]. Metabolic syndrome, a preventable health problem, is therefore very common all over the world. This condition is definitely related to unbalanced and Western style nutritional habits and also sedentary lifestyle behaviors which are common even in childhood. Practices such as a healthy diet and physical activity may protect against metabolic syndrome. The literature shows benefits of the Mediterranean diet in decreasing risk of metabolic syndrome [10-12].

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERAIA OF METABOLIC SYNDROME

As already mentioned, obesity is the main diagnostic criterion for metabolic syndrome. Defined as undesirable weight gain, it is a common chronic non-communicable disease of our time [13].

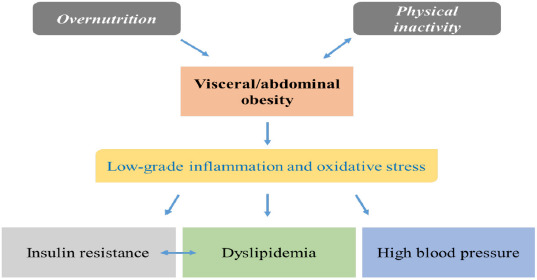

Obesity, especially visceral/abdominal obesity, is associated with comorbidities such as IR, high blood pressure and dyslipidemia (e.g. low high-density lipoprotein, HDL and high triacylglycerol, TAG) [14]. Insulin resistance is defined as poor tissue response to the hormone insulin and it is definitely related to visceral obesity with its associated inflammation and oxidative stress. IR may increase dyslipidemia, atherosclerosis and other coronary artery disease risk factors. It is regarded as the first stage of type II diabetes mellitus [15]. Another modifiable cause of mortality is high blood pressure, which is a risk factor for renal dysfunction, myocardial infarcts and stroke. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) system impairment and high sodium intake are related to high blood pressure [16]. Dyslipidemia means low plasma concentrations of HDL, high TAG and/or low-density lipoprotein (LDL). There are two types of dyslipidemia: primary and secondary. Secondary dyslipidemia is related to issues such as obesity and IR which are related in turn to overnutrition [17]. Figure 1 shows these mechanisms as a summary.

Fig. 1.

Simple mechanism of development of metabolic syndrome.

RISK FACTORS FOR METABOLIC SYNDROME

There are two types of risk factors for metabolic syndrome: those that can and cannot be altered. Diet, physical activity and smoking are alterable risk factors that people can change to reduce their risk of metabolic syndrome [23]. A Western diet is more likely to induce metabolic syndrome than certain other diet models [24], because it includes a large proportion of red meat, processed red meat products, refined grains, high-fat dairy products and few fruits, vegetables, nuts or legumes [25]. Saturated, trans and omega 6 (n-6) fatty acids, simple carbohydrates, sucrose and salt are major elements of the Western diet, which is poor in complex carbohydrates, dietary fiber and n-3 fatty acids [26]. The above elements can be associated with oxidative stress, inflammation, dyslipidemia and non-communicable disorders such as obesity and its comorbidities [27]. Another risk factor for metabolic syndrome is sedentary lifestyle [28]. Regular physical activity can increase energy expenditure, lipolysis and insulin sensitivity, while decreasing blood pressure. It can improve blood lipid parameters [29]. Thus, there is a relation between sedentary lifestyle and metabolic syndrome risk [28, 29]. Smoking, one of the worst habits, is linked to accumulation of abdominal fat and visceral obesity, IR, dyslipidemia, hypertension and other abnormalities which are all linked to oxidative stress and inflammation [30]. High alcohol consumption can also increase health risks, such as visceral obesity, poor insulin sensitivity, high blood pressure and abnormal lipid profile [31].

The Mediterranean diet is the most effective nutrition model which is a potential agent to decrease noncommunicable chronic disorders via its contents. It includes many beneficial nutrients that can influence metabolic pathways adversely affected due to chronic diseases, of course, has a potential impact on metabolic syndrome (see section 2.2). Accordingly, we review the recent literature on the links between the Mediterranean diet and metabolic syndrome.

The Mediterranean diet vs common diets

Various nutrition models, such as the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH), the Nordic diet and the Mediterranean diet have been designed as alternatives to Western style eating habits, which have spread all over the world [32]. DASH was developed to decrease the risk of hypertension and it is often prescribed for people diagnosed with this disorder. DASH may also be effective against obesity, coronary artery disease and related non-communicable disorders [33]. The Nordic diet is a nutritional model based on the nutritional habits of the Nordic peoples [34]. The Mediterranean diet is another region-specific nutritional model based on the healthy eating habits of Mediterranean peoples [35]. These three nutrition models (DASH, Nordic and Mediterranean diet) are rich in nutrients beneficial for health [33-35]. The Western diet contains many harmful elements which may increase the risk of non-communicable diseases [36]. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has listed the Mediterranean diet as an Intangible Cultural Heritage [37].

From this point, it is possible to indicate, DASH is a therapeutic nutrition model and there is no food pyramid to make it easier for adherence to this nutrition model. Nordic diet is based on the Nordic region-related nutrition habits which is so difficult to adopt by other people elsewhere. And also, some recommendations are not compatible with the optimal nutrition principles such as canola oil consumption (due to omega 6 content). In this prospect, the Mediterranean diet has a general food pyramid with easy food consumption recommendations while each recommendation is objective and compatible with the principles of optimal nutrition.

BENEFICIAL NUTRIENTS AND BIOACTIVE SUBSTANCES IN THE MEDITERRANEAN DIET

The Mediterranean diet includes items that are consumed with different frequencies, indicated in Table II as often, moderately and rarely [38, Tab. II].

Tab. II.

| Consumption frequencies | ||

|---|---|---|

| Often | Moderately | Rarely |

| Olive oil, vegetables, fruit, nuts, legumes, unprocessed cereals | Fish, red wine, dairy | Poultry, red meat, processed red meat products |

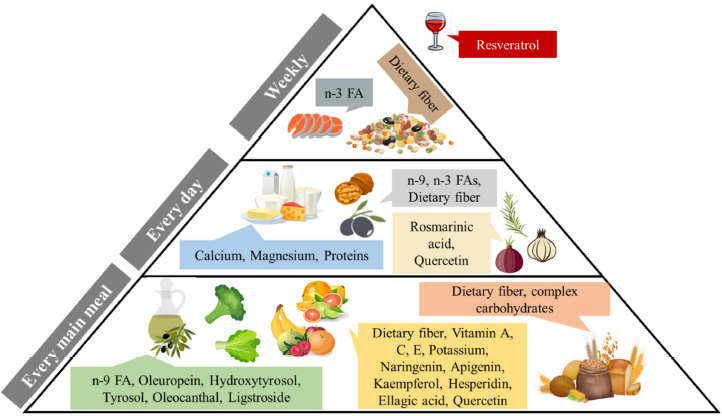

Bach-Faig et al. [40] developed a Mediterranean diet pyramid with consumption frequencies and amounts. The pyramid also includes suggestions for physical and social activities. In 2020, Serra-Majem et al. [41] updated the pyramid with sustainability principles and Dayi et al. [42] replaced some items with traditional foods of Cyprus to facilitate users in that location and decrease human impact on the planet.

Certain items of the Mediterranean diet contain polyphenols such as naringenin, apigenin, kaempferol, hesperidin, ellagic acid, oleuropein, rosmarinic acid, resveratrol and quercetin, as well as dietary fiber, monounsaturated fatty acids such as omega 9 (n-9), polyunsaturated fatty acids such as omega 3 (n-3), complex carbohydrates and many vitamins (A, C and E) and minerals (calcium, potassium, magnesium etc.) which can reduce the risk of metabolic syndrome [43-46]. Figure 2 shows the nutrients and their food sources according to the basic Mediterranean diet pyramid.

Fig. 2.

Some nutrients and polyphenols of the Mediterranean diet that may reduce the risk of developing metabolic syndrome [Prepared by authors, based on the references in section 2.1., 3rd paragraph].

EFFECTS OF DIETARY NUTRIENTS AND BIOACTIVE SUBSTANCES ON METABOLIC SYNDROME DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

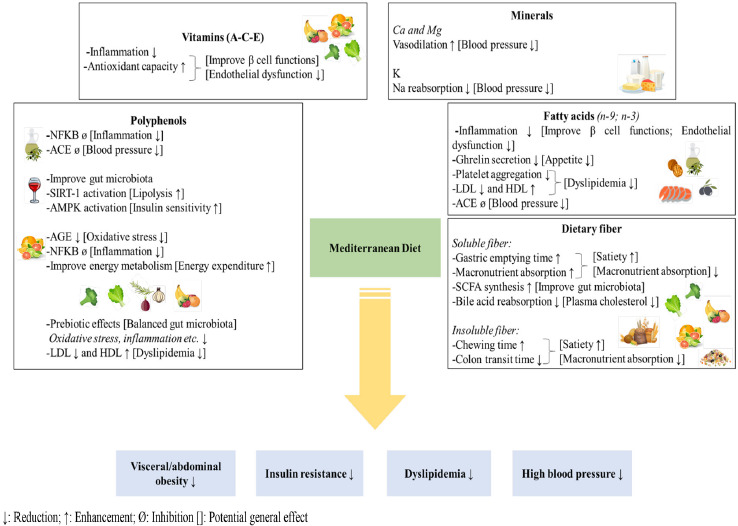

Figure 3 shows the potential beneficial effects of the Mediterranean diet on the different components of metabolic syndrome. Olive oil is a typical item of the Mediterranean diet and its polyphenols can mitigate the risk of metabolic syndrome by reducing of visceral obesity, IR, blood pressure and lipid peroxidation. These polyphenols can also block signaling and expression of nuclear factor kappa B (NFKB), important risk factors for metabolic syndrome, thus decreasing secretion of proinflammatory cytokines [47, 48]. Another typical item of the Mediterranean diet is red wine. The main polyphenol in red wine, resveratrol, can exert anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects [49, 50]. Resveratrol may also help regulate the human gut microbiota, an important component of metabolic syndrome, activate sirtuin 1, which is important for lipolysis, and activate adenosine monophosphate protein kinase, which can increase insulin sensitivity [49, 50].

Fig. 3.

Potential effects of the Mediterranean diet on different components of metabolic syndrome. Each box indicates major nutrients and nutritional substances with effects marked as up or down arrows, increased or decreased effect consequently. Furthermore, potential general effects were marked with brackets. [Prepared by authors, based on the references in section 2.2.].

Citrus production and consumption are common in the Mediterranean region. Citrus polyphenols can decrease advanced glycation end products and block NFKB expression, thus decreasing oxidative stress and inflammation in the human body. A decrease in oxidative stress and inflammation biomarkers may in turn increase insulin sensitivity, improve lipid metabolism and lower blood pressure. Polyphenols such as naringenin may improve energy metabolism thus reducing visceral obesity [51]. Mediterranean vegetables, fruits and spices are good sources of polyphenols, important bioactive substances which as we have said, can block oxidative stress- and inflammation-related pathways. They therefore increase plasma concentrations of HDL and decrease those of LDL, as well as improving IR, body mass index and blood pressure [52]. Dietary polyphenols can be an effective prebiotic, potentially decreasing pathogenic and increasing beneficial microorganisms of the gut microbiota. A balanced microbiota may be related to good glucose tolerance and insulin secretion, while decreasing lipogenesis and inflammation [53]. In summary, polyphenols typical of the Mediterranean diet can decrease inflammation, oxidative stress, IR, lipid oxidation, body weight, blood pressure and endothelial dysfunction, reducing the risk factors for metabolic syndrome [54].

The Mediterranean diet includes some beneficial fatty acids such as n-9 and n-3 (due to frequent consumption of olive oil and moderate consumption of fish), while containing few saturated and trans fatty acids [39]. Omega 9 fatty acids, especially oleic acid, have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects and may therefore improve pancreatic beta-cell functions, insulin sensitivity and endothelial function [55]. Oleic acid can affect hypothalamic function and decrease ghrelin secretion [55]. It may inhibit platelet aggregation. It can also decrease plasma concentrations of LDL and increase those of HDL [56]. The oleic acid and polyphenols of olive oil can inhibit the ACE pathway, thus regulating blood pressure [57]. Omega 3 fatty acids can also diminish metabolic syndrome criteria [58, 59].

There are two types of dietary fiber: soluble and insoluble [60]. Soluble and insoluble fiber both have potential beneficial effects on metabolic syndrome [61]. Soluble fiber increases gastric emptying time and macronutrient absorption by increasing intraluminal viscosity. It may therefore be effective for reduction of body weight and regulation of postprandial blood glucose levels. During fermentation, soluble fiber produces short chain fatty acids, which can decrease glucose and fatty acid production by the liver, as well as absorption of macronutrients via inhibition of enterocyte contact of these [62]. In addition, soluble fiber reduces bile acid reabsorption so the liver has to produce more bile acid. Since cholesterol is a building block of bile acid, while our body produces new bile acid, plasma concentrations of cholesterol decrease [63]. Insoluble fiber increases chewing time and decreases colon transit time, which stimulates the vagus nerve and creates a sense of satiety. These mechanisms can lead to lower food intake and nutrient absorption which are important factors against obesity and IR [62]. According to the literature, complex carbohydrates can have similar effects [64].

Vitamin A, C and E are antioxidants that can protect against oxidative stress which plays a role in many non-communicable disorders such as IR, cardiovascular disease and cancer [65, 66]. Antioxidants can reduce stress on pancreatic beta-cells and tissues. These effects may increase insulin sensitivity and secretion which are important factors against IR and for promoting weight loss [67]. These vitamins also decrease proinflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species, improving endothelial function. They therefore have roles in blood pressure regulation, lipid metabolism and cardiovascular health [68, 69].

Minerals such as calcium, magnesium and potassium can have antihypertensive effects [70]. Low calcium intake can stimulate the renin-angiotensin pathway, increasing blood pressure through sodium reabsorption, while calcium deficiency stimulates parathyroid hormone secretion further increasing calcium uptake by cells, which can cause peripheral vascular resistance and an increase in blood pressure [71].

The calcium antagonist magnesium decreases calcium concentrations in cells and increases certain prostaglandin E series which in turn instigate vasodilation [72]. Likewise, potassium is a sodium antagonist which decreases reabsorption of sodium, a prohypertensive mineral, by the kidneys [73].

In addition to these nutrients and bioactive substances beneficial for metabolic syndrome, the Mediterranean diet features fewer harmful items, such as saturated and trans fatty acids, linoleic acid (n-6), cholesterol, simple carbohydrates, sodium, nitrites and nitrates, and contains lower total fats [38, 39, 74].

Based on these potential effects, the Mediterranean diet carries a chance to decrease the risk of metabolic syndrome and increase life expectancy. On the other hand, the effects of the Mediterranean diet are not only limited to metabolic syndrome. So, it can be estimated that, governments/health authorities can decrease financial expenditure on health if they develop some programs to increase adherence to the Mediterranean diet.

RELATION BETWEEN OTHER PATTERNS OF THE MEDITERRANEAN DIET AND METABOLIC SYNDROME

Social and physical activities and fun are important components of the Mediterranean lifestyle. These factors are related to physiological and psychological wellbeing [40].

Regular physical activity has positive effects on health, such as decreasing fat mass, plasma levels of LDL and TAG, inflammation, oxidative stress and blood pressure, while increasing insulin sensitivity, glucose tolerance and plasma levels of HDL [75]. Due to these beneficial effects, regular physical activity has to be a complementary behavior to the Mediterranean diet to further decrease the risk of the metabolic syndrome. And also, WHO suggests at least 150 minutes/week of moderate-intensity physical activity for adults to be healthy. Thus, all the Mediterranean diet pyramids have regular physical activity suggestions at the base [40-42].

Even more, the adherence to the MD is also embedded into the attitude of individuals for encouraging their own food production. This brings up two positive features, firstly the activity levels are increased and secondly the environmental impact becomes self-rewarding. Therefore, this circle is a very proliferative one: the more the MD is favored, the more the self-productivity is achieved resulting in a stronger life style adaptation [42].

Social activities are important for mood: depression and anxiety are linked to many diseases, higher food intake and lower physical activity, which are risk factors of metabolic syndrome [76]. Furthermore, chronic melancholy may cause inflammation and oxidative stress and so be related to metabolic syndrome [77].

Table III list various studies on the subject. For the meta-analysis, ‘number of studies’ shows how many original studies are included and the sample size of studies has been shown as ‘n’.

Tab. III.

Studies on the effects of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome.

| Authors | Type | Effects of Mediterranean diet |

|---|---|---|

| Kastoroni et al. [78] | Meta-analysis (Number of studies: 50; n: 534,906) |

0.42 cm ↓ waist circumference 1.17 mg/dL ↑ HDL 6.14 mg/dL ↓ TAG 2.35 mm Hg ↓ systolic and 1.58 mm Hg ↓ diastolic BP |

| Huo et al. [79] | Meta-analysis (Number of studies: 9; n: 1178) |

0.30% ↓ HbA1c 0.72 mmol/L ↓ FPG 0.55 μU/mL ↓ fasting insulin 0.14 mmol/L ↓ total cholesterol 0.29 mmol/L ↓ TAG 1.45 mm Hg ↓ systolic and 1.41 mm Hg ↓ diastolic BP |

| Richard et al. [80] | Original research (n: 26 males) |

C-reactive protein (CRP) ↓ IL-6, IL-18 and TNF-α ↓ ≥8.5 cm waist circumference ↓ IL-6 and IL-18 ↓ |

| Moosavian et al. [81] | Systematic review (Number of studies: 10; n: 856) |

Improved body measurements, plasma lipid profile and glucose regulation |

| Mayneris-Perxachs et al. [82] | Original research (n: 424) |

Incidence, reversion and prevalence of metabolic syndrome ↓ |

| Pavić et al. [83] | Original research (n: 124) |

HDL ↑ and systolic BP ↓ The Mediterranean diet was effective for the components of metabolic syndrome |

| Meslier et al. [84] | Original research (n: 82 healthy overweight and obese participants) |

Plasma cholesterol and LDL ↓ Insulin sensitivity ↑ Systemic inflammation ↓ |

↓: Reduction; ↑: Enhancement

Results of some current studies support the potential effect mechanisms of the Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome which this review article shows. According to these results, the Mediterranean diet has been shown to be effective for weight loss, regulation of blood glucose and lipids, decreasing inflammation and blood pressure (Tab. III).

In conclusion, the Mediterranean diet is an effective nutritional model against non-communicable chronic disorders anywhere in the world. This review examined one such disease, metabolic syndrome, via a literature search for related mechanisms. Future research should address local Mediterranean food consumption by country, such as Cyprus, and its effects on the components of metabolic syndrome.

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions

TD searched the literature and wrote the main outline of the article. MO contributed the concept of the article and revised the main outline of the manuscript.

Figures and tables

References

- [1].Belete R, Ataro Z, Abdu A, Sheleme M. Global prevalence of metabolic syndrome among patients with type I diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2021;13:1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-021-00641-8 10.1186/s13098-021-00641-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rochlani Y, Pothineni NV, Kovelamudi S, Mehta JL. Metabolic syndrome: Pathophysiology, management and modulation by natural compounds. Ther Adv in Cardiovasc Dis 2017;11:215-25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753944717711379 10.1177/1753944717711379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Collins KH, Herzog W, MacDonald GZ, Reimer RA, Rios JL, Smith IC, Zernicke RF, Hart DA. Obesity, metabolic syndrome and musculoskeletal disease: Common inflammatory pathways suggest a central role for loss of muscle integrity. Front Physiol 2018;9:1-25. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00112 10.3389/fphys.2018.00112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].McCracken E, Monaghan M, Sreenivasan S, Edin FRCP. Pathophysiology of the metabolic syndrome. Clin Dermatol 2018;36:14-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.09.004 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lee SH, Tao S, Kim HS. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its related risk complications among Koreans. Nutrients 2019;11:1-9. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081755 10.3390/nu11081755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Aguilar M, Bhuket T, Torres S, Liu B, Wong RJ. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the United States, 2003-2012. JAMA 2015;313:1973-4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.4260 10.1001/jama.2015.4260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liang XP, Or CY, Tsoi MF, Cheung CL, Cheung BMY. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011-2018. Eur Heart J 2021;42:1-24. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab724.2420 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab724.242033428719 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Syed MA, Al Nuaimi AS, Zainel AJAL, A/Qotba HA. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in primary health settings in Qatar: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08609-5 10.1186/s12889-020-08609-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Naghipour M, Joukar F, Nikbakht HA, Hassanipour S, Asgharnezhad M, Arab-Zozani M, Mansour-Ghanaei F. High prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its related demographic factors in North of Iran: Results from the PERSIAN Guilan Cohort Study. Int J Endocrinol 2021:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8862456 10.1155/2021/8862456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Grosso G, Mistretta A, Marventano S, Purrello A, Vitaglione P, Calabrese G, Drago F, Galvano F. Beneficial effects of the Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome. Curr Pharm Des 2014;20:5039-44. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612819666131206112144 10.2174/1381612819666131206112144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Papadaki A, Nolen-Doerr E, Mantzoros CS. The effect of the Mediterranean diet on metabolic health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials in adults. Nutrients 2020;12:1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113342 10.3390/nu12113342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bakaloudi DR, Chrysoula L, Kotzakioulafi E, Theodoridis X, Chourdakis M. Impact of the level of adherence to Mediterranean diet on the parameters of metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients 2021;13:1-25. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051514 10.3390/nu13051514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Müller MJ, Geisler C. Defining obesity as a disease. Eur J Clin Nutr 2017;71:1256-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2017.155 10.1038/ejcn.2017.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Eberechukwu LE, Eyam ES, Nsan E. Types of obesity and its effect on blood pressure of secondary school students in rural and urban areas of Cross River State, Nigeria. IOSR J Pharm 2013;3:60-6. https://doi.org/10.9790/3013-0343060-66 10.9790/3013-0343060-66 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gutiérrez-Rodelo C, Roura-Guiberna A, Olivares-Reyes JA. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance: An update. Gac Méd Méx 2017;153:197-209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Oparil S, Acelajado MC, Bakris GL, Berlowitz DR, Cífkovά R, Dorminiczak AF, Grassi G, Jordan J, Poulter NR, Rodgers A, Whelton PK. Hypertension. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019;4:1-48. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2018.14 10.1038/nrdp.2018.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yuan Y, Chen W, Luo L, Xu C. Dyslipidemia: Causes, symptoms and treatment. IJTSRD 2021;5:1013-6. Available at: www.ijtsrd.com. (Accessed on: January 01 2022). [Google Scholar]

- [18].World Health Organization-WHO (1999). Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications: Report of a WHO Consultation. Part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; 1999. Available at: http://www.whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/WHO_NCD_NCS_99.2.pdf. (Accessed on: January 01 2022). [Google Scholar]

- [19].International Diabetes Federation-IDF (2006). The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the Metabolic Syndrome. Part: Worldwide definition for use in clinical practice. International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium; 2006. Available at: https://www.idf.org/component/attachments/attachments.html?id=705&task=download (Accessed on: January 01 2022). [Google Scholar]

- [20].Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Jr Smith SC, Spertus JA, Costa F. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 2005;112:2735-52. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Alberti KGMM, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WPT, Loria CM, Smith SC. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009;120:1640-5. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].American Heart Association-AHA (2016). Symptoms and Diagnosis of Metabolic Syndrome. How Is Metabolic Syndrome Diagnosed? American Heart Association: Dallas, Texas; 2016. Available at: https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/metabolic-syndrome/symptoms-and-diagnosis-of-metabolic-syndrome. (Accessed on: January 01 2022) [Google Scholar]

- [23].Al-Qawasmeh RH, Tayyem RF. Dietary and lifestyle risk factors and metabolic syndrome: Literature review. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci 2018;6:594-608. https://doi.org/10.12944/CRNFSJ.6.3.03 10.12944/CRNFSJ.6.3.03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Drake I, Sonestedt E, Eriscon U, Wallström P, Orho-Melander M. A Western dietary pattern is prospectively associated with cardio-metabolic traits and incidence of the metabolic syndrome. Br J Nutr 2018;119:1168-76. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711451800079X 10.1017/S000711451800079X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Strate LL, Keeley BR, Cao Y, Wu K, Giovannucci EL, Chan AT. Western dietary pattern increases and prudent dietary pattern decreases, risk of incident diverticulitis in a prospective cohort study. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1023-30. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.038 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Statovci D, Aguilera M, MacSharry J, Melgar S. The impact of Western diet and nutrients on the microbiota and immune response at mucosal interfaces. Front Immunol 2017;8:1-21. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00838 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kopp W. How Western diet and lifestyle drive the pandemic of obesity and civilization diseases. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2019;12:2221-36. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S216791 10.2147/DMSO.S216791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gallard-Alfaro L, Bibiloni MM, Mascaró CM, Montemayor S, Ruiz-Canela M, Salas-Salvadó J, Corella D, Fito M, Romaguera D, Vioque J, Alonso-Gomez AM, Warnberg J, Martinez JA, Serra-Majem L, Estruch R, Fernandez-Garcia JC, Lapetra J, Pinto X, Rios AG, Bueno-Cavanillas A, Gaforio JJ, Matia-Martin P, Daimiel L, Mico-Perez RM, Vidal J, Vazquez C, Ros E, Fernandez-Lazaro CI, Becerra-Tomas N, Gimenez-Alba IM, Zomeno MD, Konieczna J, Compan-Gabucio L, Tojal-Sierra L, Perez-Lopez J, Zulet MA, Casanas-Quintana T, Castro-Barquero S, Gomez-Perez AM, Santos-Lozano JM, Galera A, Basterra-Gortari FJ, Basora J, Saiz C, Perez-Vega KA, Galmes-Panades AM, Tercero-Macia C, Sorto-Sanchez C, Sayon-Orea C, Garcia-Gavilan J, Munoz-Martinez J, Tur JA. Leisure-time physical activity, sedentary behavior and diet quality are associated with metabolic syndrome severity: The PREDIMED-Plus study. Nutrients 2020;12:1-20. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041013 10.3390/nu12041013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Myers J, Kokkinos P, Nyelin E. Physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness and the metabolic syndrome. Nutrients 2019;11:1-18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11071652 10.3390/nu11071652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hwang GY, Cho YJ, Chung RH, Kim SH. The relationship between smoking level and metabolic syndrome in male health check-up examinees over 40 years of age. Korean J Fam Med 2014;35:219-26. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.2014.35.5.219 10.4082/kjfm.2014.35.5.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Vieira IMM, Santos BLP, Ruzene DS, Brάnyık T, Teixeira JA, E Silva JBDA, Silva DP. Alcohol and health: Standards of consumption, benefits and harm – A review. Czech J Food Sci 2018;36:427-40. https://doi.org/10.17221/117/2018-CJFS 10.17221/117/2018-CJFS [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Grosso G, Fresάn U, Bes-Rastrollo M, Marventano S, Galvano F. Environmental impact of dietary choices: Role of the Mediterranean and other dietary patterns in an Italian cohort. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:1-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051468 10.3390/ijerph17051468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wickman BE, Enkhmaa B, Ridberg R, Romero E, Cadeiras M, Meyers F, Steinberg F. Dietary management of heart failure: DASH diet and precision nutrition perspectives. Nutrients 2021;13:1-24. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124424 10.3390/nu13124424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Adamsson V, Reumark A, Cederholm T, Vessby B, Risérus U, Johansson G. What is a healthy Nordic diet? Foods and nutrients in the NORDIET study. Food Nutr Res 2012;56:1-8. https://doi.org/10.3402/fnr.v56i0.18189 10.3402/fnr.v56i0.18189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ventriglio A, Sancassiani F, Contu MP, Latorre M, Di Slavatore M, Fornaro M, Bhugra D. Mediterranean diet and its benefits on health and mental health: A literature review. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2020;16:156-64. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017902016010156 10.2174/1745017902016010156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Carrera-Bastos P, Fontes-Villalba M, O’Keefe JH, Lindeberg S, Cordain L. The Western diet and lifestyle and diseases of civilization. Res Rep Clin Cardiol 2011;2:15-35. https://doi.org/10.2147/RRCC.S16919 10.2147/RRCC.S16919 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [37].United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization-UNESCO (2013). Culture, Intangible Heritage, Mediterranean Diet. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: United Nations; 2013. Available at: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/mediterranean-diet-00884. (Accessed on: January 01 2022) [Google Scholar]

- [38].Trichopoulou A, Martínez-Gonzάlez MA, Tong TY, Forouhi NG, Khandelwal S, Prabhakaran D, Mozaffarian D, de Lorgeril M. Definitions and potential health benefits of the Mediterranean diet: views from experts around the world. BMC Medicine 2014;12:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-12-112 10.1186/1741-7015-12-112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].D’Innocenzo S, Biagi C, Lanari M. Obesity and the Mediterranean diet: A review of evidence of the role and sustainability of the Mediterranean diet. Nutrients 2019;11:1-25. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11061306 10.3390/nu11061306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bach-Faig A, Berry EM, Lairon D, Reguant J, Trichopoulou A, Dernini S, Medina FX, Battino M, Belahsen R, Miranda G, Serra-Majem L. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr 2011;14:2274-84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980011002515 10.1017/S1368980011002515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Serra-Majem L, Tomaino L, Dernini S, Berry EM, Lairon D, de la Cruz JN, Bach-Faig A, Donini LM, Medina FX, Belahsen R, Piscopo S, Capone R, Aranceta-Bartrina J, Vecchia CL, Trichopoulou A. Updating the Mediterranean diet pyramid towards sustainability: Focus on environmental concerns. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:1-20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238758 10.3390/ijerph17238758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Cyprus Modification of the Mediterranean Diet Pyramid: Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Consumption Frequencies of the Traditional Foods of Adults in the Island of Cyprus, Taygun Dayi, Near East University, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Santos-Buelgo C, Gonzάlez-Manzano S, Gonzάlez-Paramάs AM. Wine, polyphenols and Mediterranean diets. What else is there to say? Molecules 2021;26:1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26185537 10.3390/molecules26185537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Cannataro R, Fazio A, Torre CL, Caroleo MC, Cione E. Polyphenols in the Mediterranean diet: From dietary sources to microRNA modulation. Antioxidants 2021;10:1-24. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10020328 10.3390/antiox10020328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Giroli MG, Werba JP, Risé P, Porro B, Sala A, Amato M, Tremoli E, Bonomi A, Veglia F. Effects of Mediterranean diet or low-fat diet on blood fatty acids in patients with coronary heart disease. A randomized intervention study. Nutrients 2021;13:1-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072389 10.3390/nu13072389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Schwingshackl L, Morze J, Hoffmann G. Mediterranean diet and health status: Active ingredients and pharmacological mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol 2020;177:1241-57. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.14778 10.1111/bph.14778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Saibandith B, Spencer JPE, Rowland IR, Commane DM. Olive polyphenols and the metabolic syndrome. Molecules 2017;22:1-15. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22071082 10.3390/molecules22071082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].de Souza PAL, Marcadenti A, Portal VL. Effects of olive oil phenolic compounds on inflammation in the prevention and treatment of coronary artery disease. Nutrients 2017;9:1-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9101087 10.3390/nu9101087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hou CY, Tain YL, Yu HR, Huang LT. The effects of resveratrol in the treatment of metabolic syndrome. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:1-15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030535 10.3390/ijms20030535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Chaplin A, Carpéné C, Mercader J. Resveratrol, metabolic syndrome and gut microbiota. Nutrients 2018;10:1-29. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111651 10.3390/nu10111651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Alam MA, Subhan N, Rahman MM, Uddin SJ, Reza HM, Sarker SD. Effect of citrus flavonoids, naringin and naringenin on metabolic syndrome and their mechanisms of action. Adv Nutr 2014;5:404-17. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.113.005603 10.3945/an.113.005603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Liu K, Luo M, Wei S. The bioprotective effects of polyphenols on metabolic syndrome against oxidative stress: Evidences and perspectives. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019;2019:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6713194 10.1155/2019/6713194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kasprzak-Drozd K, Oniszczuk T, Stasiak M, Oniszczuk A. Beneficial effects of phenolic compounds on gut microbiota and metabolic syndrome. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:1-24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22073715 10.3390/ijms22073715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Finicelli M, Squillaro T, Cristo FD, Salle AD, Melone MAB, Galderisi U, Peluso G. Metabolic syndrome, Mediterranean diet, and polyphenols: Evidence and perspectives. J Cell Physiol 2019;234:5807-26. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.27506 10.1002/jcp.27506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Rehman K, Haider K, Jabeen K, Akash MSH. Current perspectives of oleic acid: Regulation of molecular pathways in mitochondrial and endothelial functioning against insulin resistance and diabetes. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2020;21:631-43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-020-09549-6 10.1007/s11154-020-09549-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Karacor K, Cam M. Effects of oleic acid. MSD 2015;2:125-32. https://doi.org/10.17546/msd.25609 10.17546/msd.25609 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Massaro M, Scoditti E, Carluccio MA, Calabriso N, Santarpino G, Verri T, De Caterina R. Effects of olive oil on blood pressure: Epidemiological, clinical and mechanistic evidence. Nutrients 2020;12:1-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061548 10.3390/nu12061548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Poudyal H, Panchal SK, Diwan V, Brown L. Omega-3 fatty acids and metabolic syndrome: Effects and emerging mechanisms of action. Prog Lipid Res 2011;50:372-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plipres.2011.06.003 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Khalili L, Valdes-Ramos R, Harbige LS. Effect of n-3 (Omega-3) polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation on metabolic and inflammatory biomarkers and body weight in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. Metabolites 2021;11:1-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11110742 10.3390/metabo11110742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Nevara GA, Muhammad SKS, Zawawi N, Mustapha NA, Karim R. Dietary fiber: Fractionation, characterization and potential sources from defatted oilseeds. Foods 2021;10:1-19. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040754 10.3390/foods10040754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Chen JP, Chen GC, Wang XP, Qin L, Bai Y. Dietary fiber and metabolic syndrome: A meta-analysis and review of related mechanisms. Nutrients 2018;10:1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010024 10.3390/nu10010024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Slavin JL. Dietary fiber and body weight. Nutrition 2005;21:411-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2004.08.018 10.1016/j.nut.2004.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Pezzali JG, Shoveller AK, Ellis J. Examining the effects of diet composition, soluble fiber and species on total fecal excretion of bile acids: A meta-analysis. Front Vet Sci 2021;8:1-14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.748803 10.3389/fvets.2021.748803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Khan Khattak MMA. Physiological effects of dietary complex carbohydrates and its metabolites role in certain disease. Pak J Nutr 2002;4:161-8. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjn.2002.161.168 10.3923/pjn.2002.161.168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Higgins MR, Izadi A, Kaviani M. Antioxidants and exercise performance: With a focus on vitamin E and C supplementation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:1-26. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228452 10.3390/ijerph17228452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Tomoeda M, Kubo C, Yoshizawa H, Yuki M, Kitamura M, Nagata S, Murakami M, Nishizawa Y, Tomita Y. Role of antioxidant vitamins administration on the oxidative stress. Cent Eur J Med 2013;8:509-16. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11536-013-0173-6 10.2478/s11536-013-0173-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Said E, Mousa S, Fawzi M, Sabry NA, Farid S. Combined effect of high-dose vitamin A, vitamin E supplementation and zinc on adult patients with diabetes: A randomized trial. J Adv Res 2021;28:27-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2020.06.013 10.1016/j.jare.2020.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Pellegrino D. Antioxidants and cardiovascular risk factors. Diseases 2016;4:1-9. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases4010011 10.3390/diseases4010011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Chiu HF, Venkatakrishnan K, Golovinskaia O, Wang CK. Impact of micronutrients on hypertension: Evidence from clinical trials with a special focus on meta-analysis. Nutrients 2021;13:1-19. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020588 10.3390/nu13020588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Houston MC, Harper KJ. Potassium, magnesium and calcium: Their role in both the cause and treatment of hypertension. J Clin Hypertens 2008;10:3-11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.08575.x 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.08575.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Villa-Etchegoyen C, Lombarte M, Matamoros N, Belizάn JM, Cormick G. Mechanisms involved in the relationship between low calcium intake and high blood pressure. Nutrients 2019;11:1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11051112 10.3390/nu11051112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Onor ICO, Hill LM, Famodimu MM, Coleman MR, Huynh CH, Beyl RA, Payne CJ, Johnston EK, Okogbaa JI, Gillard CJ, Sarpong DF, Borghol A, Okpechi SC, Norbert I, Sanne SE, Guillory SG. Association of serum magnesium with blood pressure in patients with hypertensive crises: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2021;13:1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124213 10.3390/nu13124213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Iqbal S, Klammer N, Ekmekcioglu C. The effect of electrolytes on blood pressure: A brief summary of meta-analyses. Nutrients 2019;11:1-18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11061362 10.3390/nu11061362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Davis C, Bryan J, Hodgson J, Murphy K. Definition of the Mediterranean diet: A literature review. Nutrients 2015;7:9139-53. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7115459 10.3390/nu7115459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Lakka TA, Laaksonen DE. Physical activity in prevention and treatment of the metabolic syndrome. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2007;32:76-88. https://doi.org/10.1139/H06-113 10.1139/H06-113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Moradi Y, Albatineh AN, Mahmoodi H, Gheshlagh RG. The relationship between depression and risk of metabolic syndrome: A meta‐analysis of observational studies. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol 2021;7:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40842-021-00117-8 10.1186/s40842-021-00117-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Mansur RB, Brietzke E, Mclntyre RS. Is there a “metabolic-mood syndrome”? A review of the relationship between obesity and mood disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015;52:89-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.12.017 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Kastorini CM, Milionis HJ, Esposito K, Giugliano D, Goudevenos JA, Panagiotakos DB. The effect of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome and its components. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1299-1313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.073 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Huo R, Du T, Xu Y, Xu W, Chen X, Sun K, Yu X. Effects of Mediterranean-style diet on glycemic control, weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors among type 2diabetes individuals: a meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr 2015;69:1200-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2014.243 10.1038/ejcn.2014.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Richard C, Couture P, Desroches S, Lamarche B. Effect of the Mediterranean diet with and without weight loss on markers of inflammation in men with metabolic syndrome. Obesity 2013;21:51-7. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2012.148 10.1038/oby.2012.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Moosavian SP, Arab A, Paknahad Z. The effect of a Mediterranean diet on metabolic parameters in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2020;35:40-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2019.10.008 10.1016/j.clnesp.2019.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Mayneris-Perxachs J, Sala-Vila A, Chisaguano M, Castellote AI, Estruch R, Covas MI, Fito M, Salas-Salvado J, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Lamuela-Raventos R, Ros E, Lopez-Sabater MC. Effects of 1-year intervention with a Mediterranean diet on plasma fatty acid composition and metabolic syndrome in a population at high cardiovascular risk. PLoS One 2014;9:1-11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085202 10.1371/journal.pone.0085202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Pavić E, Hadžiabdić MO, Mucalo I, Martinis I, Romić Z, Božikov V, Rahelić D. Effect of the Mediterranean diet in combination with exercise on metabolic syndrome parameters: 1-year randomized controlled trial. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 2019;89:132-43. https://doi.org/10.1024/0300-9831/a000462 10.1024/0300-9831/a000462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Meslier V, Laiola M, Roager HM, De Flippis F, Roume H, Quinquis B, Giacco R, Mennella I, Ferracane R, Pons N, Pasolli E, Rivellese A, Dragsted LO, Vitaglione P, Ehrlich SD, Ercolini D. Mediterranean diet intervention in overweight and obese subjects lowers plasma cholesterol and causes changes in the gut microbiome and metabolome independently of energy intake. Gut 2020;69:1258-68. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320438 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]