Abstract

Dopamine D1 agonists enhance cognition, but the role of different signaling pathways (e.g., cAMP or β-arrestin) is unclear. The current study compared 2-methyldihydrexidine and CY208,243, drugs with different degrees of both D1 intrinsic activity and functional selectivity. 2-Methyldihydrexidine is a full agonist at adenylate cyclase and a super-agonist at β-arrestin recruitment, whereas CY208,243 has relatively high intrinsic activity at adenylate cyclase, but much lower at β-arrestin recruitment. Both drugs decreased, albeit in dissimilar ways, the firing rate of neurons in prefrontal cortex sensitive to outcome-related aspects of a working memory task. 2-Methyldihydrexidine was superior to CY208,243 in prospectively enhancing similarity and retrospectively distinguishing differences between correct and error outcomes based on firing rates, enhancing the micro-network measured by oscillations of spikes and local field potentials, and improving behavioral performance. This study is the first to examine how ligand signaling bias affects both behavioral and neurophysiological endpoints in the intact animal. The data show that maximal enhancement of cognition via D1 activation occurred with a pattern of signaling that involved full unbiased intrinsic activity, or agonists with high β-arrestin activity.

Introduction

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) guides higher-order cognitive function through representational knowledge. Its neuronal activities have properties of cognitive representation that embody strategies for performing memory-guided behaviors1–3 Not surprisingly, working memory (WM) deficits are observed commonly in many neurologic and psychiatric disorders, as well as in normal aging. It is clear that dopamine D1 receptors (D1R) have a critical role in the regulation of WM in PFC. D1Rs stabilize PFC neuronal representations of WM, and either hyper- or hypo-activity of D1Rs can impair WM.4 Several D1R intracellular signaling pathways may be involved in this regulation, including cAMP synthesis5 and signaling initiated by β-arrestin recruitment.6–8 Increased cAMP concentration has been the canonical mechanism of D1R activation. Optimal amounts of cAMP synthesis improve neuronal representations of WM in PFC; firing is decreased in response to noise input, therefore the signal-to-noise ratio is enhanced.5 Recently, several studies of β-arrestin recruitment suggest that this mechanism may be possibly critical for the treatment of memory-related disorders.6–8 Despite the evidence of cognitive enhancement resulting from D1R stimulation, there is no centrally available D1 agonist yet approved for this indication.

One strategy for discovering novel drugs with better therapeutic indices is known as functional selectivity or biased signaling.9 This involves the search for compounds that are receptor selective, but that only activate a subset of the signaling pathways of the targeted receptor. As an example, in schizophrenia, antagonism of the dopamine D2 receptor is a hallmark for approved antipsychotic drugs, whereas D2 agonists will induce or exacerbate psychotic symptoms. Conversely, aripiprazole, a compound with functionally selective D2 properties (including full agonism in some systems), is an effective antipsychotic.10,11 More recently, there have been several reports of functionally selective/biased opioid receptor ligands in which undesirable effects are decreased.12,13 The relative importance of cAMP and β-arrestin pathways14 for a given behavior is fundamental to understanding how GPCR signaling bias can be leveraged to improve therapeutic indices. Thus, we sought to determine how D1 activation of these pathways might regulate WM representation in the PFC. We performed in vitro screening and identified two D1 selective compounds with similar intrinsic activity at D1 G protein (cAMP-based) signaling, but with markedly different β-arrestin activation, that permitted us to do the first investigation on the relative roles of these two signaling pathways. Our results suggest that activation of both cAMP and β-arrestin may be required for efficient cognitive enhancement at the single unit, the micro-network, and behavioral levels.

Materials and Methods

Materials

2-methyldihydrexidine (2MDHX) was synthesized by modifications of published procedures15 (Supplementary Figure 1). CY208,243 (CY208) was purchased from Tocris (Minneapolis, MN) and SCH23390 was purchased from Sigma/RBI (St. Louis MO). SCH39166 (ecicopam) was a gift from Dr. Richard Chipkin of Psyadonrx, Inc. (Germantown MD). The compounds in the second independent biochemical experiment were synthesized by Pfizer Central Research (Cambridge MA) or purchased from Sigma or Tocris.

In vitro methods

Adenylate cyclase (cAMP) assay

Two independent experiments using different cells lines and different sources of compounds (vide supra) were conducted (Supplementary Table 1). The first experiment (data in Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 2; Table 1), used Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably transfected with human D1R. And the radioimmunoassay for cAMP was carried out with minor modifications of previously published procedures16. In the second experiment (data in Supplementary Table 2), a stable clone (HEK293T cells) expressing high levels of hD1R was generated and frozen until screening. A homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF) competitive immunoassay (Cisbio International 62AM4PEJ) was used to detect cAMP.

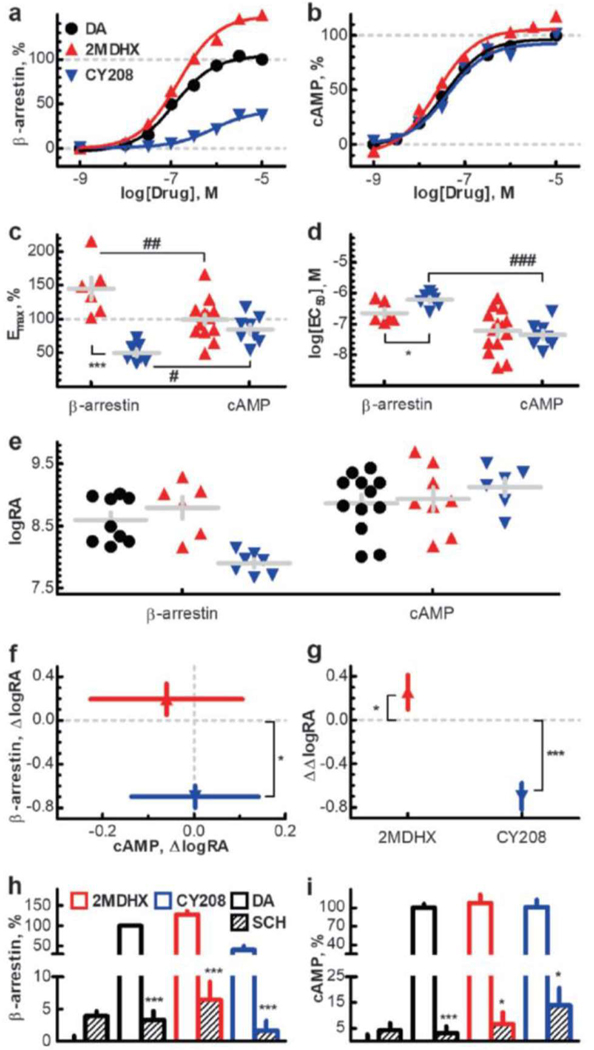

Figure 1. D1 intrinsic activity and functional selectivity of 2MDHX and CY208.

(a & b) Representative curves of induction of β-arrestin activation at D1R (a) and D1R-mediated adenylate cyclase activation (b) by 2MDHX and CY208. All data are expressed as a percentage of dopamine activity. (c & d) Population analysis showed 2MDHX and CY208 have functional selectivity at β-arrestin vs. cAMP based on Emax (c) and EC50 (d). Grey lines represent mean±SEM. Star indicates the comparison between 2MDHX vs CY208. Pound indicates the comparison between β-arrestin vs cAMP. (e - g) Averaged (mean±SEM) bias scaled by (f) Δlog(RA) and (g) ΔΔlog(RA). Each individual sample was shown in (e), along with the dopamine as reference. (h & i) D1 antagonist SCH23390 (SCH) completely blocked the increases of β-arrestin (h) and cAMP (i) induced by 2MDHX and CY208. *, # indicates P<0.05; **, ## indicates P<0.005; ***, ### indicates P<0.001.

Table 1.

Intrinsic activity and functional selectivity of tested compounds.

| Ligand | CAMP | β-arrestin | ΔΔlog(RA)# | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emax, % | EC50, nM | n | Δlog(RA)* | Emax, % | EC50, nM | n | Δlog(RA)* | ||

| DA | 101 ± 3 | 159 ± 62 | 20 | 0.0 ± 0.1 | 107 ± 4 | 373 ± 93 | 9 | 0.0 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.1 |

| 2MDHX | 100 ± 8 | 151 ± 53 | 14 | −0.1 ± 0.2 | 145 ± 17 | 302 ± 106 | 6 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.2 |

| CY208 | 85 ± 7 | 69 ± 28 | 8 | 0.0 ± 0.1 | 50 ± 5 | 676 ± 116 | 7 | −0.7 ± 0.1 | −0.7 ± 0.1 |

| SKF83959 | 38 ± 8 | 115 ± 18 | 2 | −0.7 ± 0.1 | 40 ± 0 | 161 ± 6 | 3 | −0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| SKF38393 | 46 ± 5 | 289 ± 158 | 7 | −0.6 ± 0.2 | 59 ± 5 | 451 ± 123 | 6 | −0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.2 |

| Dihydrexidine | 98 ± 2 | 98 ± 28 | 5 | −0.1 ± 0.2 | 131 ± 6 | 1023 ± 288 | 3 | −0.5 ± 0.1 | −0.3 ± 0.1 |

| LEK-8829 | 61 ± 15 | 127 ± 47 | 4 | −0.5 ± 0.2 | 14 ± 4 | 506 ± 112 | 4 | −1.2 ± 0.1 | −0.7 ± 0.1 |

| Dinapsoline | 127 ± 13 | 54 ± 14 | 2 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 107 ± 3 | 427 ± 109 | 4 | −0.1± 0.1 | −0.3 ± 0.1 |

Reference compound is dopamine (DA).

Bias vector is β-arrestin over cAMP.

Data obtained from experiment one. Each value represents mean ± se. Maximal efficacy is expressed relative to dopamine.

Assessment of β-arrestin activation

Two independent experiments using different sources of compounds (vide supra) were conducted. In both experiments, PathHunter® βarrestin assay (DiscoveRx, Fremont, CA) was used to measure β-arrestin activation in live CHO-hD1 cells as previously reported16.

In vivo methods

Total seventeen male adult Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were used. All animal care and surgical procedures were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and Penn State Hershey Animal Resources Program and were reviewed and approved by IACUC of Penn State College of Medicine.

Delayed alternation response test in T-maze

A standard T-maze combined with a Limelight video recording system (Actimetrics, Coulbourn Instruments, Whitehall, PA) was used. Pre-defined zone and grids (Supplementary Figure 3a) were used to assess the behavior of a subject as decision making (staying in zone A) and choice (passing grids i or ii), and mark the reference time (RT; i.e., the time for choice behavior). The detailed test procedure has been described recently.1 Briefly, the rats were trained to alternate visits two arms of the maze after a delayed time, and only a correct choice led to a reward. When the rats were performing at the appropriate baseline (60–80% correct), they were first subcutaneously administrated vehicle (0.1% ascorbate). If performance was still at baseline, then various doses (0.1–1000 nmol/kg) of 2MDHX or CY208 were tested. All of the drug administration was twenty minutes before the task. In some experiments, an additional pretreatment of SCH39116 (0.01 mg/kg) was given one hour before the task. No subject was retested unless a minimum of five days had passed since the prior drug treatment. The duration of rats staying at the intersection was recorded as the time to make a decision. The correct rate of choice and the speed of rats running in the maze (from gate opening to intersection reaching) were calculated after the testing session.

Electrophysiological recordings

Six rats were unilaterally implanted with microwire electrodes into the PFC as described previously1. Briefly, a microwire electrode array was implanted at 3.0 mm rostral to bregma, 0.4 mm lateral to bregma, and vertically lowered to a depth of 3.5 mm to brain surface, according to the rat brain atlas17 (Supplementary Figure 3b). The microwire electrode array was made from 25 µm stainless steel wire coated by polyimide (H-ML) having an impedance of 600–900 kΩ, arranged in a 2 × 4 configuration with 250 µm between electrodes (MicroProbes, Gaithersburg, MD), and the recording procedure follows a published protocol1. Briefly, the OmniPlex Neural Data Acquisition System (Plexon, Dallas, TX) was used to record neural signal, and the RT signal from Limelight synchronized neural and behavioral recording. Wideband signal (digitized at 40 kHz), spike signal (high-pass filtered by a cutoff of 250 Hz), and local field potential (LFP, low-pass filtered by a cutoff of 250 Hz and downsampled to 1 kHz) were all recorded for later off-line analysis. Action potentials were detected and sorted both on-line and off-line via Offline Sorter (Plexon, Dallas, TX) to get better unit isolation results. Units with the signal to noise ratio greater than 2 were used for analysis. Waveform correlation coefficients were calculated via linear regression18 to identify single units across recording sessions from microwire electrode that remained stationary (Supplementary Figure 3c). The drug effects were tested at a dose of 10 nmol/kg which was shown to be the most effective dosage to improve cognition in a pilot dose-response study.

Data analysis

All data are reported as mean ± SEM unless otherwise specified. Depending on the analysis, we used MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick MA), SAS (Cary NC), SPSS (IBM, Armonk NY), and/or Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) as noted for individual experiments.

Functional assays

The dose-response curve was calculated by a sigmoidal dose-response equation with a standard slope to obtain apparent potency (EC50) and maximal efficacy of intrinsic activity (Emax). ANOVA was used to examine the difference of EC50 and the difference of Emax between compounds (2MDHX vs. CY208) and between signaling pathways (β-arrestin vs. cAMP). We used currently accepted methods to calculate a quantitative measure of the signaling bias of the test compounds.19–21 First, relative activity scale was calculated as log(RA)=log(Emax/EC50). Then the bias was quantified as ∆∆log(RA) = ∆ log(RA) beta- ∆log(RA) cAMP, where ∆log(RA)=log(RA)drug-log(RA)dopamine. Dopamine was the reference compound for both cAMP and β-arrestin assays, and the vector of the bias was β-arrestin versus cAMP. This method is reported to decrease observation of assay bias, as well as system bias innate to the assays used.19–21

Single unit activity

For the analyses of neural sensitivities to the behavioral events, spike counts were binned (0.1 s) around RT (±2 s) in each trial for each unit. Each trial in the task was divided into three epochs: baseline, prior and post choice. Prior and post choice epochs are one second before or after RT which reflects the mnemonic component of the task.1 Baseline epoch is the combination of one second before prior epoch and one second after post epoch. ANOVA was used to examine the outcome-related activity with regard to (i) different epochs of the task (baseline, prior vs. post) and (ii) different outcome (correct vs. error). Outcome sensitivity was scaled by calculating the sensitivity index (d’), the ability to distinguish error from correct based on firing rates during the prior or post choice epochs, where . To examine drug effects, ANOVA was used to compare differences in firing rate and differences in d’ among drug conditions and to analyze interactions between condition (control, 2MDHX vs. CY208) and outcome (correct vs. error). To construct peri-event spike histograms for groups of units, z-scores for each unit were calculated as , where FRi is the firing rate in the ith bin of the peri-event period, FRmean is the mean firing rate over baseline epoch, and sd is the standard deviation of firing rate for baseline epoch, with values averaged for all trials. These per-unit normalized z-scores were then averaged for groups. Paired ANOVA was used for population analysis. Tukey’s multiple comparison was used for post hoc test.

Spectral analysis

Spectral analysis was done using an open source toolbox, EEGLAB.22 The dataset included single unit spike and LFPs. Spike counts were first binned (1 ms) for each unit and then normalized to z-scores. LFPs were first normalized to z-scores and then averaged among all recorded channels for each animal. Peri-event matrices were then created around RT (±1 s) for each unit and each animal. The spike-spike and LFP-spike coherence was calculated by the function:

The LFP oscillation power was calculated by the function:

For each frequency, paired ANOVA was used to compare differences in coherence and power among drug conditions. Tukey’s multiple comparison was used for post hoc testing.

Behavioral data

In the behavioral test, rats served as their own controls, thus repeated ANOVA was used to test whether the correct rate of choice, the time for decision making, and the speed of running were changed by administrations of drugs. The effects of dose were tested by pairwise multiple post comparison.

Results

Functional characterization of D1-selective ligands:

To select ligands for this study, we screened a variety of known D1-selective ligands in vitro, including some ligands recently reported as having high functional bias23 (Table 1; Supplementary Table 2). We did not reproduce the high bias reported for several phenylbenzazepines, and therefore did not utilize them. We selected 2-methyldihydrexidine (2MDHX) based on its full intrinsic activity at adenylate cyclase [Figure 1a-d; Table 1; maximal efficacy (Emax) =100±8%; apparent potency (EC50) =151±53 nM], and even higher intrinsic activity than dopamine at β-arrestin recruitment (Emax=145±17%; EC50=302±106 nM). The second ligand selected was CY208,243 (CY208) based on its high intrinsic activity at adenylate cyclase (Emax=85±7%; EC50=69±28 nM), but lower intrinsic activity at β-arrestin recruitment (Emax=50±5%; EC50=676±116 nM). The D1 antagonist SCH23390 completely blocked the increases of cAMP and β-arrestin for both ligands (Figure 1h-i; cAMP, P2MDHX*2MDHX+SCH23390=0.01, PCY208*CY208+SCH23390=0.03; β-arrestin, P2MDHX*2MDHX+SCH23390=0.0007, PCY208*CY208+SCH23390<0.0001), consistent with a D1-mediated effect.

We found that 2MDHX was more efficacious (higher Emax; Figure 1c-d; P2MDHX*CY208<0.001) and more potent (lower EC50; P2MDHX*CY208=0.04) than CY208 at β-arrestin recruitment, whereas at cAMP synthesis the efficacy (P2MDHX*CY208=0.22) and potency (P2MDHX*CY208=0.40) were not significantly different. These were also reflected by their normalized relative activity values [∆log(RA); Figure 1f; β-arrestin, 2MDHX=0.2±0.1 vs. CY208=−0.7±0.1, P2MDHX*dopamine=0.51, PCY208*dopamine=0.01; cAMP, 2MDHX=−0.1±0.2 vs. CY208=0.0±0.1, P2MDHX*dopamine=0.59, PCY208*dopamine=0.98]. Of particular importance is the fact that, when comparing between signaling pathways, 2MDHX is slightly biased towards β-arrestin (Figure 1c-d; Emax, PcAMP*β-arrestin=0.002; EC50, PcAMP*β-arrestin=0.16), whereas CY208 is slightly biased against β-arrestin (Emax, PcAMP*β-arrestin=0.02; EC50, PcAMP*β-arrestin<0.001). These were also reflected by their bias vectors [ ∆∆log(RA) ; Figure 1g; 2MDHX=0.3±0.2 vs. CY208=−0.7±0.1, P2MDHX*dopamine=0.03, PCY208*dopamine<0.001]. Although it would have been ideal to have a completely biased compound, these are rare (cf., Discussion); the differences we found, however, were adequate to justify the use of 2MDHX and CY208 as paired probes to evaluate the possible role of signaling bias in the regulation of WM representation in the PFC.

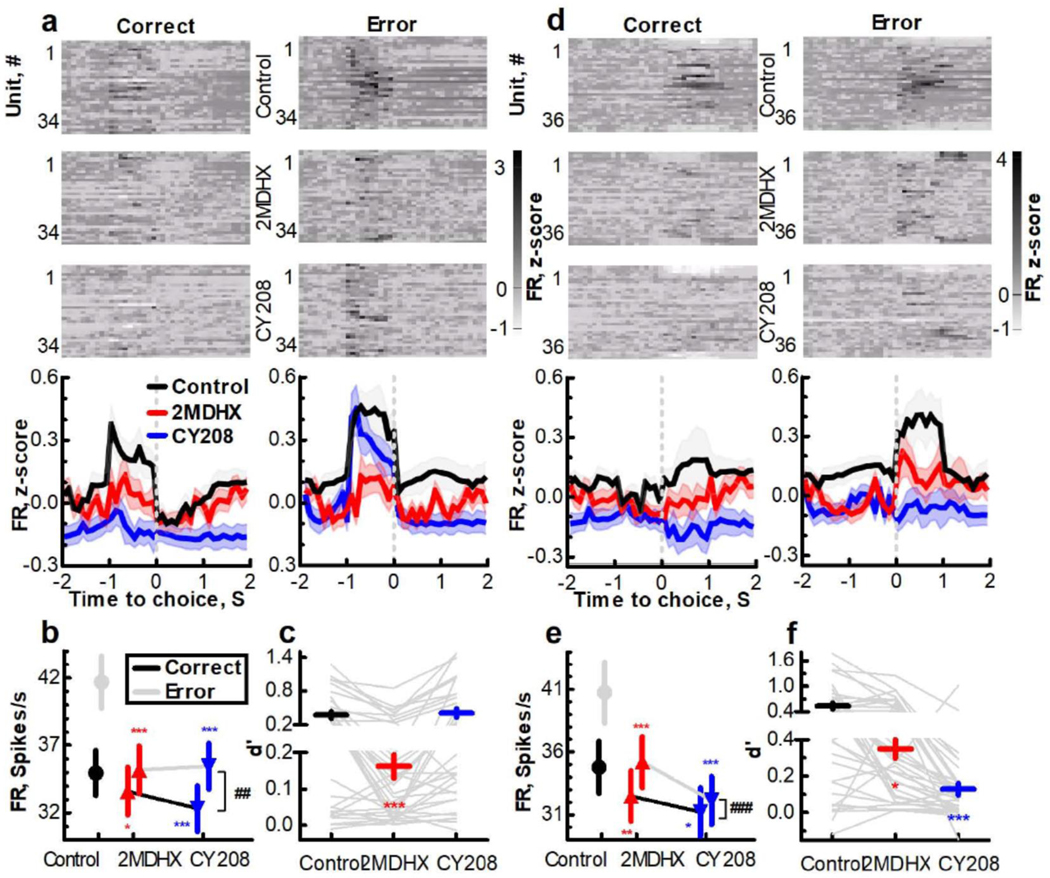

Effects of 2MDHX and CY208 on single unit activity in PFC by systemic administration to rats performing the delayed alternation response (DAR) task:

PFC neurons encode outcome-related information by firing differently between correct and error trials.1–3 As expected, when rats performed the DAR task, neurons increased their firing by ca. 1 sec near the time of choice. The change in firing was classified as increase before outcome (prospective neurons) or after outcome (retrospective neurons). We found that a large portion of recorded neurons fired higher in error trials than in correct trials, and we recorded only three neurons that had higher firing during correct outcome, consistent with previous reports that the neuronal activity in PFC tends to predict premature errors significantly better than correct trials.1–3 Thus, the analysis focused on the former group.

Prospective neurons fired more before making error choice (correct=35±2 vs. error=42±2 spikes/s; P<0.0001), and both 2MDHX and CY208 decreased the firing of these neurons (Figure 2a-b, Supplementary Figure 4a). The major decrease was before error outcome (2MDHX=35±2 vs. CY208=35±2 spikes/s; Pcontrol*2MDHX<0.0001, Pcontrol*CY208<0.0001). The decrease also occurred before the correct outcome, but was a small effect (2MDHX=34±2 vs. CY208=32±2 spikes/s; Pcontrol*2MDHX<0.05, Pcontrol*CY208<0.0001). Interestingly, the sensitivity index (d’) of error vs. correct based on firing was significantly decreased by 2MDHX more than CY208 (Figure 2c; control=0.4±0.1, 2MDHX=0.2±0.03, CY208=0.4±0.1; Pcontrol*2MDHX<0.0001, Pcontrol*CY208=0.59, P2MDHX*CY208<0.0001). This was also reflected by the interaction analysis between drug and outcome based on firing (Figure 2b; P(2MDHX,CY208)*(correct,error)=0.0002). Conversely, retrospective neurons fired more after making error choice (correct=35±2 vs. error=41±2 spikes/s; P<0.0001). Both 2MDHX and CY208 decreased their firing (Figure 2d-e, Supplementary Figure 4b) with the largest decrease occurring after error outcome (2MDHX=35±2 vs. CY208=32±2 spikes/s; Pcontrol*2MDHX<0.0001, Pcontrol*CY208<0.0001). The decrease also occurred after the correct outcome but was a small effect (2MDHX=33±2 cs. CY208=31±2 spikes/s; Pcontrol*2MDHX<0.005, Pcontrol*CY208<0.0001). As opposed to prospective neurons, d’ of retrospective neurons was decreased less by 2MDHX than by CY208 (Figure 2f; control=0.5±0.1, 2MDHX=0.3±0.1, CY208=0.1±0.03; Pcontrol*2MDHX=0.006, Pcontrol*CY208<0.0001, P2MDHX*CY208<0.0001). And there was a significant interaction between drug and outcome based on firing (Figure 2e; P(2MDHX,CY208)*(correct,error)<0.0001).

Figure 2. Effects of 2MDHX and CY208 on single unit activity in PFC. (a & d).

Both 2MDHX and CY208 decreased firing rate (FR) of prospective neurons (a) and retrospective neurons (d). (Upper) Normalized FR for every single unit for control vs. 2MDHX and CY208. (Lower) Averaged FR of all units. (b & e) There was a significant interaction between drug and outcome based on FR for prospective neurons (b) and retrospective neurons (e). Star indicates post hoc comparison between control vs 2MDHX (red) or between control vs CY208 (blue). Pound indicates the interaction between drugs (2MDHX vs CY208) and outcomes (correct vs error). (c & f) d’of error vs. correct based on FR was significantly decreased by 2MDHX but not CY208 for prospective neurons (c), whereas it was less decreased by 2MDHX than CY208 for retrospective neurons (f). Grey lines represent each unit. *, # indicates P<0.05; **, ## indicates P<0.005; ***, ### indicates P<0.0001.

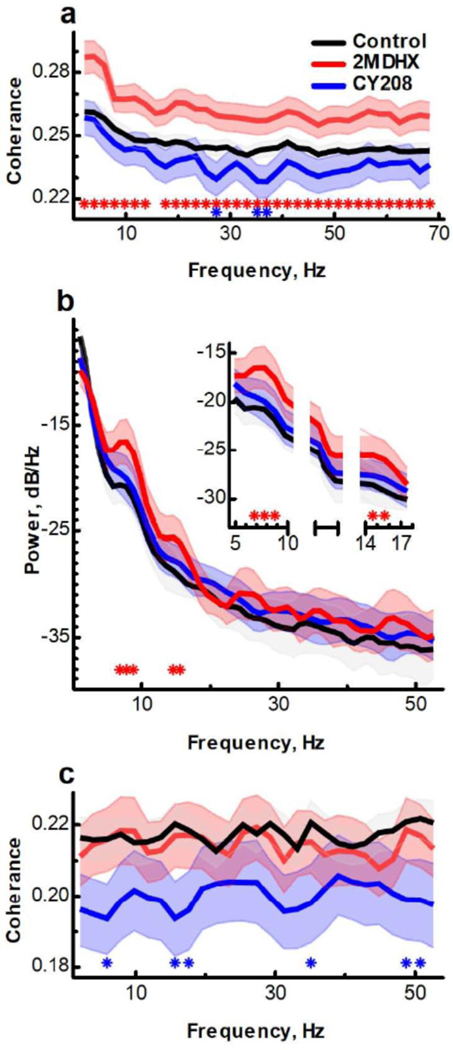

Spectral analysis of single unit spikes and local field potentials (LFPs) of PFC neuronal networks:

Single unit firing rates were synchronized with each other (Figure 3a; n=141 pairs), and 2MDHX significantly increased the coherences at all frequencies (Pcontrol*2MDHX<0.05 for each frequency except 16 Hz where Pcontrol*2MDHX=0.07). CY208 had no significant effects on delta (1–4 Hz), theta (5–8 Hz), and alpha bands (9–12 Hz, Pcontrol*CY208>0.05 for each frequency), but decreased coherences of beta (27 Hz) and gamma bands (35–37 Hz, Pcontrol*CY208<0.05 for each frequency). There was a significant difference between 2MDHX and CY208 regarding the change of spike-spike synchronization (P2MDHX*CY208<0.0001). In addition, the oscillation power of LFPs was also increased by 2MDHX (Figure 3b; n=6 animals), especially at theta (7–9 Hz, Supplementary Figure 5) and beta bands (15–16 Hz, Pcontrol*2MDHX<0.05 for each frequency). CY208 did not cause a significant increase (Pcontrol*CY208=0.10). There was synchronization between the oscillation of single unit spikes and the oscillation of LFPs (Figure 3c; n=44 pairs). 2MDHX maintained this synchronization (Pcontrol*2MDHX>0.05 for each frequency), whereas CY208 decreased it, especially at theta (6 Hz), beta (16–18 Hz), and gamma bands (35, 49–51 Hz, Pcontrol*CY208<0.05 for each frequency). There was a significant difference between 2MDHX and CY208 regarding the change of LFP-spike synchronization (P2MDHX*CY208<0.0001).

Figure 3. Effects of 2MDHX and CY208 on the neuronal network in PFC.

(a) 2MDHX significantly increased spike-spike synchronization between units measured by coherence. CY208 did not increase but even decreased it at beta and gamma bands (27, 35–37 Hz). Each line is averaged coherence of all paired units at each frequency. Star indicates P<0.05 for post hoc comparison between control vs 2MDHX (red) or between control vs CY208 (blue). (b) 2MDHX but not CY208 significantly increased the power density of LFP oscillation at theta and beta bands (7–9, 15–16 Hz, zoom in at top right corner). Same format as in A. (c) 2MDHX maintained whereas CY208 significantly decreased synchronization between LFP oscillation and unit spike oscillation at theta, beta, and gamma bands (6, 16–18, 35, 49–51 Hz). Same format as in (a).

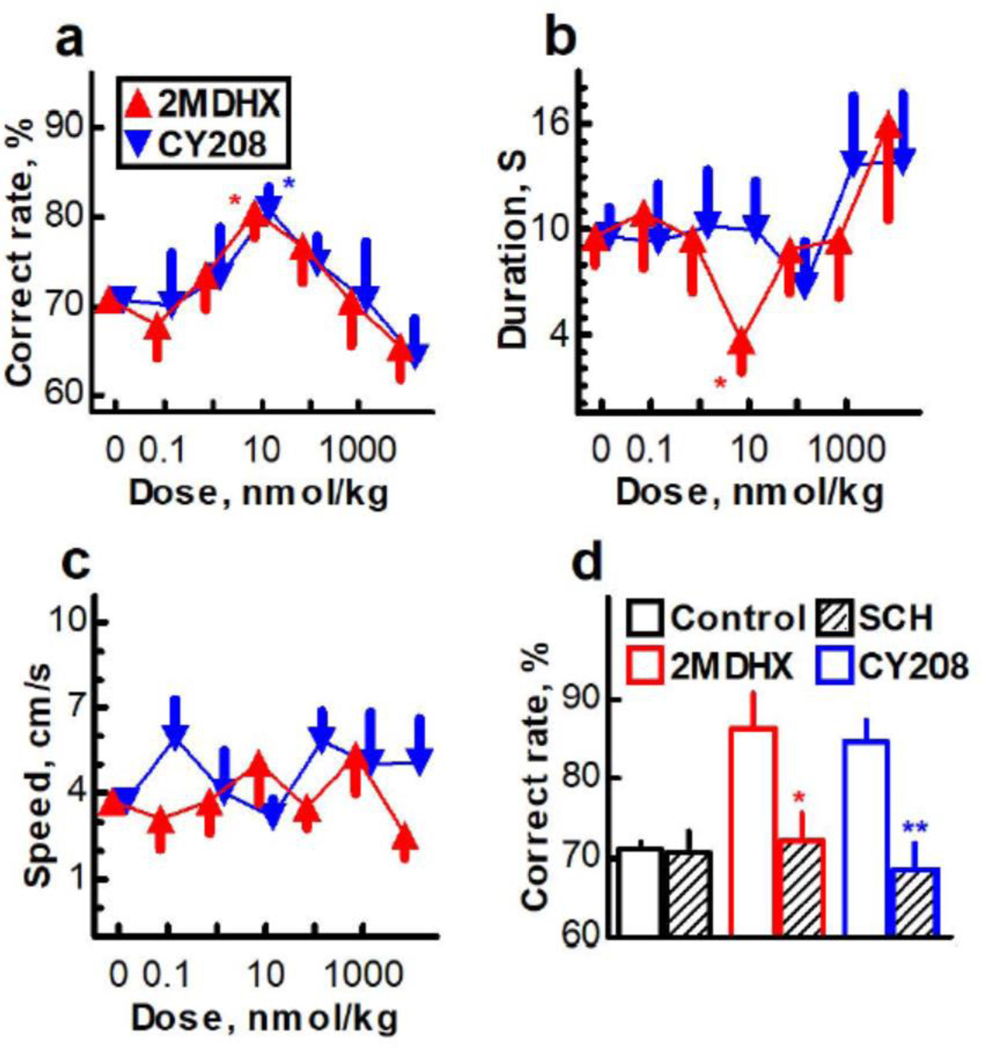

Changes in behavioral performance caused by 2MDHX and CY208:

Both compounds produced an ‘inverted-U’ dose response in which the optimal dose (10 nmol/kg) enhanced the correct rate, whereas higher doses had no significant effect or tended to impair (Figure 4a; Supplementary Table 3; 2MDHX, P0*10nmol/kg=0.004; CY208, P0*10nmol/kg=0.003; all other doses P>0.05). There was no difference between 2MDHX and CY208 in enhancing the accuracy of performance (P>0.05 for all doses). Conversely, 2MDHX significantly decreased the duration of decision making at the optimal dose (10 nmol/kg; Figure 4b; Supplementary Table 3; P0*10nmol/kg=0.04; all other doses P>0.05), whereas CY208 did not (P>0.05 for all doses). 2MDHX tended to quicken decision making better than CY208 (P2MDHX*CY208=0.08), and the change of duration was not related to motor function as reflected by no changes in running speed24–28 (Figure 4c; Supplementary Table 3; P>0.05 for both drugs at all doses). The cognitive improvement induced by either 2MDHX (Figure 4d; Pcontrol*2MDHX=0.01) or CY208 (Pcontrol*CY208=0.005) was abolished by pretreatment with the D1 antagonist SCH39166 (Pcontrol*2MDHX+SCH39166=0.53; Pcontrol*CY208+SCH39166=0.60), consistent with these effects being mediated by the D1R.5

Figure 4. Effects of 2MDHX and CY208 on cognitive performance.

(a) Both 2MDHX and CY208 produced an inverted-U dose effect on DAR task whereby low doses improved but high doses had no effect or tended to impair the accuracy of performance as measured by correct rate. (b) 2MDHX but not CY208 improved decision making at a low dose as measured by duration, whereas at high dose they both tended to impair it. (c) 2MDHX and CY208 did not change motor function as measured by running speed. Star indicates the comparison between control vs 2MDHX (red) or the comparison between control vs CY208 (blue). (d) Pretreatment of D1 antagonist SCH39166 (SCH) blocked cognitive enhancement induced by 2MDHX or CY208. * indicates P<0.05. ** indicates P<0.01.

Discussion

This study was, to our knowledge, the first to examine how the signaling bias of a drug affected both behavioral and neurophysiological endpoints in the intact animal. D1 agonists have been reported to change neuronal WM representation in PFC by decreasing firing,5 and this occurred in our study for both 2MDHX and CY208. Interestingly, along with the overall decrease, dissimilar effects were observed for 2MDHX versus CY208. 2MDHX was superior to CY208 because it prospectively enhanced similarity and retrospectively maintained the difference in firing between correct and error trials. As the discernment of firing between correct and error trials, measured by d’ in this study, encodes the outcome-related information,1–3 we interpret our findings as follows. First, neurons in PFC fire at an appropriate level to achieve a correct outcome with greater firing predicting error outcomes.29–31 2MDHX reduced firing to the ‘correct outcome level’, increasing the possibility of a correct outcome. CY208 caused similar changes, but of lower magnitude than 2MDHX. Second, once error outcomes appear, neurons in PFC increase firing, providing an adjusting feedback.2,29–32 2MDHX maintained the higher firing after error outcome better than CY208, increasing the possibility of correct outcome for the next trial. Thus, although both compounds positively affected these processes, 2MDHX produced greater improvement. The differential enhancement at the single neuron level did not lead to dramatically improved behavioral performance. There was similar performance accuracy, but only 2MDHX shortened decision-making. The two most likely explanations are either that there were inadequate differences in signaling bias between these two compounds to have dramatic behavioral effects, and/or that multiple D1-mediated signaling pathways influence behavioral outcome and one can compensate for another.

Along with single neuron activity, the neuronal micro-network measured by the oscillations of LFPs and spikes was also affected by 2MDHX and CY208. The strongest influences were for theta, beta, and gamma bands that are associated with WM, and that are impaired in many neuropsychiatric disorders.2,33,34 Interestingly, 2MDHX clearly enhanced or maintained coherence and power of oscillation, whereas CY208 had no significant effects or, at some frequencies, actually impaired these measures. Thus, both compounds affected neuronal activity, but 2MDHX produced greater cortical physiological improvements including both single neuron and micro-network. The important question, then, is whether these changes are due to signaling differences at the D1 receptor, or other mechanisms.

Do the current data reflect actions at D1 receptors?

Pharmacological studies often have great potential to translate to the clinic, as well as provide a relatively rapid route to understanding underlying mechanisms. As an example, dihydrexidine, the parent compound of 2MDHX, has been shown to have positive effects on cognition in murine35,36 and in primates, both non-human37 and human.38 Yet one of the major mechanistic limitations can be uncertainties from the possible contribution from off-target effects. With regards the current study, there are two inherent issues. First, although we have used the term “D1” throughout this manuscript, we are keenly aware that there are no known orthosteric ligands that have marked selectivity for the D1 vs. the highly homologous D5 dopamine receptor in rats. In the current studies, this is not a confound - in murine species, neither D5 binding sites, nor D5 mRNA, are found in the cortex, but rather are largely confined to the hippocampus.39,40 In primates, however, there are D5 receptors co-localized with D1 in the prefrontal cortex, although the density of D1 is far higher,41,42 so this will be an interesting issue to resolve as studies are translated to higher species.

We have also considered the effect of interactions at other receptors, especially the D2 dopamine receptor that represents a potential off-target for these two compounds. Two lines of evidence suggest that the results were not affected by D2 actions. In many pharmacological studies, the drug doses or concentrations that are used are likely to engage secondary targets (e.g., see 43). In the current study, the maximal enhancement of performance for both compounds was seen at 10 nmol/kg which, if the dose was absorbed into the circulation instantaneously and not metabolized, would equate to a maximal whole body concentration of ca. 10 nM. The actual concentration would, of course, be far less, meaning that receptor occupancy would be very low based on the 9 nM KI of 2MDHX.15 The next highest affinity for 2MDHX is for the dopamine D2 at which 2MDHX is more than 30-fold D1:D2 selective.15 This would lead to a prediction of essentially negligible receptor occupancy at the D2 or other receptors at the low doses used in these experiments. There are additional data and discussion in the Supplementary material, but we recognize that future studies using orthogonal methods will be important to test these hypotheses further.

What have we learned about the role of D1 signaling in cognitive function?

The current study has emphasized two signaling pathways clearly linked to D1R: cAMP synthesis and β-arrestin recruitment. As reported previously,15,44 both 2MDHX and CY208 have high intrinsic activity at the canonical cAMP pathway in assay systems that can detect partial agonists like SKF38393. Conversely, there was a marked difference found at β-arrestin recruitment. Some D1 agonists have previously been shown to have bias towards cAMP vs. receptor desensitization45 or internalization.46,47 In the current data for β-arrestin recruitment, CY208 was a low intrinsic activity partial agonist, whereas 2MDHX was a “super agonist”. Although the degree of bias was incomplete, these findings permitted us to compare these two compounds as probes to study the possible role of D1 signaling bias in cognition (Supplementary text). Our data clearly show that 2MDHX and CY208, two drugs with different D1 signaling bias, differentially influence cognitive regulation. The pressing question is whether it is the bias toward β-arrestin recruitment, or the subtle differences in cAMP activation, that are responsible for differences in WM representation in the PFC.

A prior study5 found that stimulation of D1Rs regulates cognition via cAMP synthesis such that a cAMP inhibitor blocks the effects of D1 agonists on neuronal activity in PFC and cognitive performance. In the current study, both 2MDHX and CY208 had high intrinsic activity at cAMP synthesis, suggesting that the overall decrease of firing requires cAMP synthesis. Along with the overall decrease, 2MDHX and CY208 caused different patterns of decrease, with the discernment of correct and error trials based on firing differently affected by 2MDHX and CY208. Neuronal oscillation was also influenced differently by 2MDHX and CY208. As intrinsic activity at β-arrestin recruitment was the largest difference between 2MDHX and CY208, it is reasonable to hypothesize that β-arrestin related signaling may also be important for neuronal WM representation in PFC.

It is clear that β-arrestin can be an important modulator of dopamine function. Rats or mice with mutations that eliminate β-arrestin recruitment have less locomotor activity,48 more dyskinesia-like behavior,6 enhanced adiposity,49 and impaired memory reconsolidation.8 Excessive stimulation of D1R (e.g., during stress) impairs cognition,4 thus greater β-arrestin recruitment may increase the internalization and desensitization of D1Rs,50 and therefore reduce D1R detrimental actions. On the other hand, β-arrestin also can evoke signaling (e.g., ERK/MAP kinase signaling and Akt/GSK3 signaling14), implying that β-arrestin-related signaling may play a role in the differentiation of 2MDHX and CY208 influencing on cognition.

It is, however, also possible that subtle differences in a G protein-mediated pathway are the defining mechanism that explains the differences between these two compounds. A previous non-human primate study compared a full D1 agonist (dihydrexidine) with another partial agonist, and concluded that only the full agonist could improve cognition of young monkey, whereas both worked on old animals,37 highlighting the importance of canonical cAMP signaling of D1. The initial D1 characterization of CY208 was done in bovine retina preparations in which, unlike the current study, CY208 was reported as a partial agonist with intrinsic activity not significantly different than the known partial agonist SKF38393 (68 vs. 58%). To our knowledge, there have been no studies that have specifically looked at how reduced receptor reserve51,52 might affect the intrinsic activity of CY208 in rat brain, hence, the role of canonical signaling via the D1 receptor cannot be ruled out as a crucial factor.

Although this study, like those with many other receptor systems, focused on cAMP and β-arrestin signaling, the results only associate the behavioral and physiological differences with the in vitro pattern of signaling. Although our data provide a very strong case for these effects being due to actions at the D1 receptor, they do not provide direct evidence that it is actually cAMP or β-arrestin that mediate the differences (much as is the case for studies with other receptor systems). Bias is likely to be seen in many signaling pathways affected by this receptor, and to different degrees. Nonetheless, when in vitro functional selectivity leads to unexpected functional changes in situ, it makes elucidation of the exact signaling mechanism even more important both heuristically and in the discovery of more efficacious new drugs.

Clinic implications and future research

Since the first report using the full agonist dihydrexidine,53 D1 agonists have been widely reported to improve cognitive performance, but with biphasic dose-response curves (i.e., performance was improved by low doses, but impaired by high doses4). This was found for both 2MDHX and CY208, with ca. 10 nmol/kg (ca. 3 µg/kg) being the most effective dosage for cognitive enhancement in rats. Of note, although performance accuracy was improved by both 2MDHX and CY208, only 2MDHX improved the quickness of decision making. D1 agonists have been hypothesized to be useful in several neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders,4,54 but despite their promise, none have yet been approved clinically although at least one is now in later-stage clinical development.55,56 In particular, the hypothesis that D1 activation could improve cognitive function has received some support from some clinical studies,38 but not others,57 although these studies are difficult to interpret because the D1 agonist that was used (dihydrexidine) has an exceptionally short half-life in humans, limiting the types of studies that can be done. New compounds with better pharmacokinetic properties (e.g., 2MDHX) will be needed to explore this approach, but the current data also suggest that functionally selective compounds may affect therapeutic specificity. Of note, it was known that a full D1 agonist (i.e., dihydrexidine) would improve working memory in both young and aged primates, whereas a partial agonist (i.e., SKF38393) only was effective in aged primates.37 The current experiments were performed on young adult rats and show that even in young animals, drugs with similar canonical intrinsic activities have different physiological and behavioral effects. It would be interesting to determine if dopamine-depleted or aged rats had an amplified difference to these two compounds based on reports of full versus partial agonists.37

The current findings provide the first neurophysiological evidence that the functional selectivity of D1 signaling has an effect on cognitive function. There are numerous experimental avenues that are left to explore, but this study is the first to demonstrate that the pattern of signaling engagement of the D1 receptor will be critical to maximizing its cognitive-enhancing effects. The results underscore the importance of both the discovery of novel D1 ligands and further exploration of the involved mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Dr. David L. Gray and Rebecca O’Connor of Pfizer Central Research for their insight and technical assistance, and Susan Kocher for her invaluable technique support.

This work was supported by: a Brain & Behavior Research Foundation Young Investigator Grant; Children’s Miracle Network Research Grant; the Penn State Hershey Neuroscience Institute; the Parkinson’s Disease Gift Fund of the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center; and R01 MH040537, U19 MH082441, and R01 NS105471.

Portions of this work were presented at the Society for Neuroscience meetings in November 2014 (Washington, DC) and November 2016 (San Diego, California).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interested:

RBM has a potential conflict-of-interest related to his role as an inventor on patents related to dopamine D1 agonists, the ownership of which has been assigned to university foundations. These issues are managed by the Conflict-of-Interest system at the Penn State University and its College of Medicine.

All References

- 1.Yang Y, Mailman RB. Strategic neuronal encoding in medial prefrontal cortex of spatial working memory in the T-maze. Behav Brain Res 2018; 343: 50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laubach M, Caetano MS, Narayanan NS. Mistakes were made: neural mechanisms for the adaptive control of action initiation by the medial prefrontal cortex. J Physiol Paris 2015; 109(1–3): 104–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horst NK, Laubach M. Working with memory: evidence for a role for the medial prefrontal cortex in performance monitoring during spatial delayed alternation. J Neurophysiol 2012; 108(12): 3276–3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnsten AF, Girgis RR, Gray DL, Mailman RB. Novel Dopamine Therapeutics for Cognitive Deficits in Schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2017; 81(1): 67–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vijayraghavan S, Wang M, Birnbaum SG, Williams GV, Arnsten AF. Inverted-U dopamine D1 receptor actions on prefrontal neurons engaged in working memory. Nat Neurosci 2007; 10(3): 376–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urs NM, Bido S, Peterson SM, Daigle TL, Bass CE, Gainetdinov RR et al. Targeting beta-arrestin2 in the treatment of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112(19): E2517–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urs NM, Daigle TL, Caron MG. A dopamine D1 receptor-dependent beta-arrestin signaling complex potentially regulates morphine-induced psychomotor activation but not reward in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011; 36(3): 551–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X, Ma L, Li HH, Huang B, Li YX, Tao YZ et al. beta-Arrestin-biased signaling mediates memory reconsolidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112(14): 4483–4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urban JD, Clarke WP, von Zastrow M, Nichols DE, Kobilka B, Weinstein H et al. Functional selectivity and classical concepts of quantitative pharmacology. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2007; 320(1): 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urban JD, Vargas GA, von Zastrow M, Mailman RB. Aripiprazole has Functionally Selective Actions at Dopamine D(2) Receptor-Mediated Signaling Pathways. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007; 32(1): 67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masri B, Salahpour A, Didriksen M, Ghisi V, Beaulieu JM, Gainetdinov RR et al. Antagonism of dopamine D2 receptor/beta-arrestin 2 interaction is a common property of clinically effective antipsychotics. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA 2008; 105(36): 13656–13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viscusi ER, Webster L, Kuss M, Daniels S, Bolognese JA, Zuckerman S et al. A randomized, phase 2 study investigating TRV130, a biased ligand of the mu-opioid receptor, for the intravenous treatment of acute pain. Pain 2016; 157(1): 264–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manglik A, Lin H, Aryal DK, McCorvy JD, Dengler D, Corder G et al. Structure-based discovery of opioid analgesics with reduced side effects. Nature 2016; 537(7619): 185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. Transduction of receptor signals by beta-arrestins. Science 2005; 308(5721): 512–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knoerzer TA, Watts VJ, Nichols DE, Mailman RB. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a series of substituted benzo[a]phenanthridines as agonists at D1 and D2 dopamine receptors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 1995; 38(16): 3062–3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SM, Kant A, Blake D, Murthy V, Boyd K, Wyrick SJ et al. SKF-83959 is not a highly-biased functionally selective D1 dopamine receptor ligand with activity at phospholipase C. Neuropharmacology 2014; 86(0): 145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press: Sydney, 2013, 472pp. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emondi AA, Rebrik SP, Kurgansky AV, Miller KD. Tracking neurons recorded from tetrodes across time. J Neurosci Methods 2004; 135(1–2): 95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenakin T. A Scale of Agonism and Allosteric Modulation for Assessment of Selectivity, Bias, and Receptor Mutation. Mol Pharmacol 2017; 92(4): 414–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winpenny D, Clark M, Cawkill D. Biased ligand quantification in drug discovery: from theory to high throughput screening to identify new biased mu opioid receptor agonists. Br J Pharmacol 2016; 173(8): 1393–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenakin T, Watson C, Muniz-Medina V, Christopoulos A, Novick S. A simple method for quantifying functional selectivity and agonist bias. ACS Chem Neurosci 2012; 3(3): 193–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delorme A, Makeig S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J Neurosci Methods 2004; 134(1): 9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conroy JL, Free RB, Sibley DR. Identification of G Protein-Biased Agonists That Fail To Recruit beta-Arrestin or Promote Internalization of the D1 Dopamine Receptor. ACS Chem Neurosci 2015; 6(4): 681–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isacson R, Kull B, Wahlestedt C, Salmi P. A 68930 and dihydrexidine inhibit locomotor activity and d-amphetamine-induced hyperactivity in rats: a role of inhibitory dopamine D(1/5) receptors in the prefrontal cortex? Neuroscience 2004; 124(1): 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heijtz RD, Kolb B, Forssberg H. Motor inhibitory role of dopamine D1 receptors: implications for ADHD. Physiol Behav 2007; 92(1–2): 155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salmi P, Isacson R, Kull B. Dihydrexidine--the first full dopamine D1 receptor agonist. CNS Drug Rev 2004; 10(3): 230–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salmi P, Ahlenius S. Sedative effects of the dopamine D1 receptor agonist A 68930 on rat open-field behavior. NeuroReport 2000; 11(6): 1269–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Darney KJ, Jr., Lewis MH, Brewster WK, Nichols DE, Mailman RB. Behavioral effects in the rat of dihydrexidine, a high-potency, full-efficacy D1 dopamine receptor agonist. Neuropsychopharmacology 1991; 5(3): 187–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffmann S, Beste C. A perspective on neural and cognitive mechanisms of error commission. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 2015; 9: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simons RF. The way of our errors: theme and variations. Psychophysiology 2010; 47(1): 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weissman DH, Roberts KC, Visscher KM, Woldorff MG. The neural bases of momentary lapses in attention. Nat Neurosci 2006; 9(7): 971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Debener S, Ullsperger M, Siegel M, Fiehler K, von Cramon DY, Engel AK. Trial-by-trial coupling of concurrent electroencephalogram and functional magnetic resonance imaging identifies the dynamics of performance monitoring. J Neurosci 2005; 25(50): 11730–11737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uhlhaas PJ, Singer W. Abnormal neural oscillations and synchrony in schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci 2010; 11(2): 100–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker KL, Chen KH, Kingyon JR, Cavanagh JF, Narayanan NS. Medial frontal approximately 4-Hz activity in humans and rodents is attenuated in PD patients and in rodents with cortical dopamine depletion. J Neurophysiol 2015; 114(2): 1310–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steele TD, Hodges DB, Jr., Levesque TR, Locke KW. D1 agonist dihydrexidine releases acetylcholine and improves cognitive performance in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1997; 58(2): 477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steele TD, Hodges DB, Jr., Levesque TR, Locke KW, Sandage BW, Jr. The D1 agonist dihydrexidine releases acetylcholine and improves cognition in rats. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1996; 777: 427–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnsten AF, Cai JX, Murphy BL, Goldman-Rakic PS. Dopamine D1 receptor mechanisms in the cognitive performance of young adult and aged monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994; 116(2): 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosell DR, Zaluda LC, McClure MM, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Strike KS, Barch DM et al. Effects of the D1 dopamine receptor agonist dihydrexidine (DAR-0100A) on working memory in schizotypal personality disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015; 40(2): 446–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montague DM, Striplin CD, Overcash JS, Drago F, Lawler CP, Mailman RB. Quantification of D1B (D5) receptors in dopamine D1A receptor-deficient mice. Synapse 2001; 39: 319–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meador Woodruff JH, Mansour A, Grandy DK, Damask SP, Civelli O, Watson SJ Jr, . Distribution of D5 dopamine receptor mRNA in rat brain. Neuroscience Letters 1992; 145(2): 209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bordelon-Glausier JR, Khan ZU, Muly EC. Quantification of D1 and D5 dopamine receptor localization in layers I, III, and V of Macaca mulatta prefrontal cortical area 9: coexpression in dendritic spines and axon terminals. J Comp Neurol 2008; 508(6): 893–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldman-Rakic P. The Relevance of the Dopamine-D1 Receptor in the Cognitive Symptoms of Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 1999; 21(6): S170–S180. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee SM, Yang Y, Mailman RB. Dopamine D1 Receptor Signaling: Does GalphaQ-Phospholipase C Actually Play a Role? The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 2014; 351(1): 9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Markstein R, Seiler MP, Jaton A, Briner U. Structure activity relationship and therapeutic uses of dopaminergic ergots. Neurochemistry International 1992; 20 Suppl: 211S–214S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lewis MM, Watts VJ, Lawler CP, Nichols DE, Mailman RB. Homologous desensitization of the D1A dopamine receptor: efficacy in causing desensitization dissociates from both receptor occupancy and functional potency. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1998; 286(1): 345–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryman-Rasmussen JP, Griffith A, Oloff S, Vaidehi N, Brown JT, Goddard WA, III et al. Functional selectivity of dopamine D(1) receptor agonists in regulating the fate of internalized receptors. Neuropharmacology 2007; 52(2): 562–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryman-Rasmussen JP, Nichols DE, Mailman RB. Differential activation of adenylate cyclase and receptor internalization by novel dopamine D1 receptor agonists. Mol Pharmacol 2005; 68(4): 1039–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beaulieu JM, Sotnikova TD, Marion S, Lefkowitz RJ, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. An Akt/beta-arrestin 2/PP2A signaling complex mediates dopaminergic neurotransmission and behavior. Cell 2005; 122(2): 261–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chebani Y, Marion C, Zizzari P, Chettab K, Pastor M, Korostelev M et al. Enhanced responsiveness of Ghsr Q343X rats to ghrelin results in enhanced adiposity without increased appetite. Science Signaling 2016; 9(424): ra39–ra39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perry SJ, Baillie GS, Kohout TA, McPhee I, Magiera MM, Ang KL et al. Targeting of cyclic AMP degradation to beta 2-adrenergic receptors by beta-arrestins. Science 2002; 298(5594): 834–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burris KD, Molski TF, Xu C, Ryan E, Tottori K, Kikuchi T et al. Aripiprazole, a novel antipsychotic, is a high-affinity partial agonist at human dopamine D2 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 302(1): 381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watts VJ, Lawler CP, Gonzales AJ, Zhou QY, Civelli O, Nichols DE et al. Spare receptors and intrinsic activity: studies with D1 dopamine receptor agonists. Synapse 1995; 21(2): 177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schneider JS, Sun ZQ, Roeltgen DP. Effects of dihydrexidine, a full dopamine D-1 receptor agonist, on delayed response performance in chronic low dose MPTP-treated monkeys. Brain Research 1994; 663(1): 140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mailman RB, Huang X. Dopamine receptor pharmacology. In: Koller WC, Melamed E (eds). Parkinson’s disease and related disorders, Part 1, vol. 83. Elsevier: New York, 2007, pp 77–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Efficacy Safety and Tolerability of PF-06649751 in Parkinson’s Disease Patients at Early Stage of the Disease. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02847650?term=parkinson+pfizer&type=Intr&draw=1&rank=2, 2017, Accessed Date Accessed 2017 Accessed.

- 56.Taking the Direct Path: The Case for D1 agonism in Parkinson’s disease. http://adpd2017.kenes.com/support-exhibition-(2)/industry-sessions#.WErWVG0o5aQ 2017, Accessed Date Accessed 2017 Accessed.

- 57.Girgis RR, Van Snellenberg JX, Glass A, Kegeles LS, Thompson JL, Wall M et al. A proof-of-concept, randomized controlled trial of DAR-0100A, a dopamine-1 receptor agonist, for cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2016; 30(5): 428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murray AM, Waddington JL. New putative selective agonists at the D-1 dopamine receptor: behavioural and neurochemical comparison of CY 208–243 with SK&F 101384 and SK&F 103243. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 1990; 35(1): 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andersen PH, Jansen JA. Dopamine receptor agonists: selectivity and dopamine D1 receptor efficacy. European Journal of Pharmacology 1990; 188(6): 335–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abbott B, Starr BS, Starr MS. CY 208–243 behaves as a typical D-1 agonist in the reserpine-treated mouse. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1991; 38(2): 259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mottola DM, Kilts JD, Lewis MM, Connery HS, Walker QD, Jones SR et al. Functional selectivity of dopamine receptor agonists. I. Selective activation of postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors linked to adenylate cyclase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 301(3): 1166–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kilts JD, Connery HS, Arrington EG, Lewis MM, Lawler CP, Oxford GS et al. Functional selectivity of dopamine receptor agonists. II. Actions of dihydrexidine in D2L receptor-transfected MN9D cells and pituitary lactotrophs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 301(3): 1179–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Murthy V, Lieu CA, Gowdahalli K, Blake DJ, Amin S, Subramanian T et al. Receptor signaling and behavioral properties of EFF0311, a longer-acting selective full D1 agonist as a potential treatment for Parkinson’s disease. FASEB Science Research Conferences, vol. April: Anaheim, CA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Temlett JA, Chong PN, Oertel WH, Jenner P, Marsden CD. The D-1 dopamine receptor partial agonist, CY 208–243, exhibits antiparkinsonian activity in the MPTP-treated marmoset. Eur J Pharmacol 1988; 156(2): 197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brewster WK, Nichols DE, Riggs RM, Mottola DM, Lovenberg TW, Lewis MH et al. trans-10,11-Dihydroxy-5,6,6a,7,8,12b-hexahydrobenzo[a]phenanthridine: A highly potent selective dopamine D1 full agonist. J Med Chem 1990; 33: 1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ghosh D, Snyder SE, Watts VJ, Mailman RB, Nichols DE. 9-Dihydroxy-2,3,7,11b-tetrahydro-1H-naph[1,2,3-de]isoquinoline: a potent full dopamine D1 agonist containing a rigid-beta-phenyldopamine pharmacophore. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 1996; 39(2): 549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.