Abstract

Introduction

Burnout among resident physicians has been an area of concern that predates the COVID-19 pandemic. With the significant turmoil during the pandemic, this study examined resident physicians’ burnout, depression, anxiety, and stress as well as the benefits of engaging in activities related to wellness, mindfulness, or mental wellbeing.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey of 298 residents from 13 residency programs sponsored by the University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita was conducted in October and November 2021. A 31-item questionnaire measured levels of burnout, depression, anxiety, and stress. A mixed method approach was used to collect, analyze, and interpret the data. Descriptive statistics, one-way ANOVA/Kruskal-Wallis tests, adjusted odds ratios (aOR), and immersion-crystallization methods were used to analyze the data.

Results

There was a 52% response rate, with 65.8% (n = 102) of the respondents reporting manifestations of burnout. Those who reported at least one manifestation of burnout experienced a higher level of emotional exhaustion (aOR = 6.73; 95% CI, 2.66–16.99; p < 0.01), depression (aOR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.04–1.41; p = 0.01), anxiety (aOR = 1.14; 95% CI, 1.00–1.30; p = 0.04), and stress (aOR = 1.36; 95% CI, 1.13–1.64; p < 0.01). Some wellness activities that respondents engaged in included regular physical activities, meditation and yoga, support from family and friends, religious activities, time away from work, and counseling sessions.

Conclusions

The findings suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic poses a significant rate of burnout and other negative mental health effects on resident physicians. Appropriate wellness and mental health support initiatives are needed to help resident physicians thrive in the health care environment.

Keywords: COVID-19, graduate medical education, Kansas, occupational burnout, surveys and questionnaires

INTRODUCTION

The first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States was confirmed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in January 2020.1 In March 2020, the World Health Organization designated the worldwide outbreak of COVID-19 as a pandemic.2 Even before this outbreak, burnout had been called a public health crisis in the U.S.3 and a disturbingly high rate of professional burnout existed among medical trainees and physicians.4–7

Burnout is an experience in response to long-term exposure to chronic job-related stress, characterized by emotional and physical exhaustion, depersonalization, and feelings of low self-worth. 5,8 Burnout among health care professionals has been associated with mood disorders, substance and alcohol use disorders, suicidal ideation, and accidents.9–11 Professional burnout also has been associated with a decrease in quality of patient care,12–14 and lower patient satisfaction scores.15,16 Prior studies have shown that the impact of professional burnout begins in medical school and continues throughout graduate medical education (GME).4,6,7,17 The COVID-19 pandemic has increased stress on health care professionals dramatically through heightened personal risk of illness, more frequent poor outcomes in patients with few proven treatment options to prevent morbidity and mortality, and overwhelming demand for healthcare resources.18–20 Resident physicians experience these same pandemic-related stresses, but they were compounded by added worry regarding training interruptions and limitations.

At the time of this study, our community-based medical school sponsored 12 residency programs and one fellowship program, encompassing 298 resident physicians. In 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 51% (67 of 131) of our resident physicians reported symptoms of professional burnout, such as emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced professional efficiency.17 Studies of resident physicians in other settings have demonstrated burnout rates of 46–53%, with increased stress, depression, and anxiety, especially in those physicians caring for COVID-19 patients or who experienced childcare and home school related stress.21,22

Given that the global community continued to be affected by the worsening spread of COVID-19, it was prudent to assess the effects on resident physician well-being. In this study, investigators (1) evaluated the prevalence of burnout and other types of emotional distress experienced by resident physicians during the second year of the pandemic; and (2) assessed respondents’ activities related to wellness, as well as solutions they considered necessary to affect a positive change in their experiences with psychological distress.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

In October and November 2021, 298 resident physicians from 13 residency/fellowship programs sponsored by the University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita (KUSM-W) were surveyed. Each resident physician received an email invitation to participate, along with a link to a 31-item survey (Appendix). A sample size of 100 was calculated as necessary for adequate power (> 0.85) to detect significant relationships between the variables with 1 degree of freedom, p < 0.05, and 0.21 effect size.23 The KUSM-W Institutional Review Board granted exemption for the study.

Study Measures

The survey included two validated measures: the two single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (MBI-2)24 adapted from the full Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-22)25 and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21).26–28 The survey also included items on demographic information (age, gender, year in residency, and specialty).

Burnout

The emotional exhaustion item (“I feel burnout from my work”) and depersonalization item (“I’ve become more callous toward people since I became a physician”) have been shown to be useful screening questions for burnout.24,29 These two items have shown the highest factor loading24,30,31 and strongest correlation24,32 with their respective emotional exhaustion and depersonalization domains in the MBI-22.24 The two single items have been used in previous studies to measure emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and manifestations of burnout among physicians and medical trainees.4,6,7,24,33

The respondents recorded the degree to which each item applied to them on a seven-point Likert scale (0 = Never, 6 = Every day). The scores of each domain were grouped into low, moderate, and high burnout categories using established cutoffs.6,7,23,24,34 Higher scores on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization domains are indicative of greater emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and greater burnout. Consistent with convention,6,7,23,25,34 residents who scored high on depersonalization and/or emotional exhaustion domains were considered as having at least one manifestation of professional burnout.

Depression, Anxiety, Stress

The resident physicians’ emotional state was measured using the DASS-21, which is a validated research tool that has been used widely to assess quality of life and consists of 21 questions in three scales designed to measure negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress.26,27 These scales have been found to have high internal consistency and can be used in a variety of settings to measure an individual’s current emotional state and changes over time.27,28 Respondents recorded how much a statement applied to them over the past week on a four-point Likert scale (0 = never, 3 = almost always). Scores for the seven questions specific to each of the three scales were summed with a possible score ranging from 0 to 21. Higher scores indicated greater levels of the corresponding emotional state. All the measures have been used in previous studies with a medical education population.17,33,35–37

Statistical Analysis

Standard descriptive statistics, One-way ANOVA/Kruskal-Wallis tests, generalized linear mixed models, and adjusted odds ratios (aOR) were used to analyze the quantitative data. Covariates included age, gender, year in residency, and specialty. All analyses were two-sided with an alpha of 0.05. The study team analyzed content of the open-ended responses (qualitative data) individually and in group meeting using an immersion-crystallization approach.17,38,39

RESULTS

Quantitative Results

Respondent Characteristics

The response rate was 52% (155 of 298). As shown in Table 1, the average age of respondents was 27.9 (SD = 3.3); 35.5% were female; 22.6% were third-year residents; and 37.4% were from the family medicine specialty. Most of the respondents (73.5%) reported to have engaged in activities related to their wellness, mindfulness, or mental wellbeing since the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic. About 32% reported that their activities increased, 19.4% reported no change, and 15.5% reported decreased activities compared to before the pandemic. There was a ± 5.46% margin of error at a 95% confidence interval between the study sample and population of all the resident physicians, demonstrating that our sample generally represented the population of all GME resident physicians at KUSM-W.40

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of responding resident physicians.a

| Characteristics | Respondents (N = 155) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean (SD), years | 27.9 (3.3) |

| Median | 28 |

| Minimum | 24 |

| Maximum | 47 |

| Gender, no. (%) | |

| Male | 54 (34.8) |

| Female | 55 (35.5) |

| Prefer to not answer | 16 (10.3) |

| Missing* | 30 (19.4) |

| Year in Residency | |

| First-year residents | 23 (14.8) |

| Second-year residents | 27 (17.4) |

| Third-year residents | 35 (22.6) |

| Fourth-year residents | 8 (5.2) |

| Fifth-year residents | 6 (3.9) |

| Missing* | 99 (63.9) |

| Specialty | |

| Anesthesiology | 2 (1.3) |

| Family Medicine | 58 (37.4) |

| Internal Medicine | 11 (7.1) |

| Medicine/Pediatrics | 2 (1.3) |

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 9 (5.8) |

| Orthopaedic Surgery | 7 (4.5) |

| Pediatrics | 11 (7.1) |

| Psychiatry | 7 (4.5) |

| Radiology | 7 (4.5) |

| Sports Medicine | 0 (0) |

| Surgery | 9 (5.8) |

| Missing* | 32 (20.6) |

| Engaged in wellness, mindfulness, or mental wellbeing? | |

| Yes | 114 (73.5) |

| No | 41 (26.5) |

| How has participation in wellness, manfulness, or mental wellbeing activities changed? | |

| Increased | 49 (31.6) |

| No change | 30 (19.4) |

| Decreased | 24 (15.5) |

| Missing* | 52 (33.5) |

Data are presented as No. (percentage) unless otherwise stated.

The number of participants who completed the survey but did not provide an answer to this specific question.

Burnout, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

In aggregate, 65.8% of all respondents met the criteria for manifestations of burnout; 41.3% reported severe or extremely severe depression; 48.4% reported severe or extremely severe anxiety; and 36.8% had severe or extremely severe stress (Table 2). The respondents who reported at least one manifestation of burnout experienced a higher level of emotional exhaustion (aOR = 6.73; 95% CI, 2.66–16.99; p < 0 .01), depression (aOR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.04–1.41; p = 0.01), anxiety (aOR = 1.14; 95% CI, 1.00–1.30; p = 0.04), and stress (aOR = 1.36; 95% CI, 1.13–1.64; p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Respondents’ burnout, depression, anxiety, and stress (N = 155).a

| Variable | Respondents |

|---|---|

| Manifestations of burnout | |

| Burnout | 102 (65.8) |

| Not burnout | 41 (26.5) |

| Missing* | 12 (7.7) |

| Emotional Exhaustion | |

| High score | 74 (47.7) |

| Moderate score | 49 (31.6) |

| Low score | 20 (12.9) |

| Missing* | 12 (7.7) |

| Depersonalization | |

| High score | 99 (63.9) |

| Moderate score | 37 (23.9) |

| Low score | 7 (4.5) |

| Missing* | 12 (7.7) |

| DASS-21, Mean (SD) | |

| Depression | 9.38 (5.91) |

| Anxiety | 8.67 (6.11) |

| Stress | 10.53 (5.81) |

| Depression | |

| Normal | 33 (21.3) |

| Mild | 13 (8.4) |

| Moderate | 28 (18.1) |

| Severe | 15 (9.7) |

| Extremely severe | 49 (31.6) |

| Missing* | 17 (11.0) |

| Anxiety | |

| Normal | 39 (25.2) |

| Mild | 10 (6.5) |

| Moderate | 14 (9.0) |

| Severe | 13 (8.4) |

| Extremely severe | 62 (40.0) |

| Missing* | 17 (11.0) |

| Stress | |

| Normal | 53 (34.2) |

| Mild | 15 (9.7) |

| Moderate | 14 (9.0) |

| Severe | 28 (18.1) |

| Extremely severe | 29 (18.7) |

| Missing* | 16 (10.3) |

Note. DASS-21, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21

Data are presented as No. (percentage) unless otherwise stated.

The number of participants who completed the survey but did not provide an answer to this specific question.

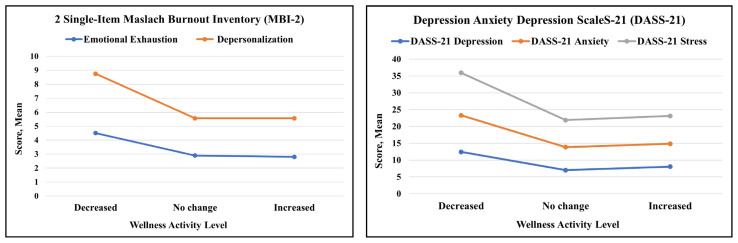

To determine if a benefit threshold exists between wellness activities and the outcomes measured, comparisons among the three activity levels (decreased, no change, and increased) were conducted using one-way ANOVAs with follow-up post-hoc analyses. The results revealed significant differences among groups on all measures (Figure 1): emotional exhaustion (F[2, 102] = 13.76; p < 0.01; η2 = 0.22), depersonalization (F[2, 102] = 10.67; p < 0.01; η2 = 0.18), depression (F[2, 98] = 7.95; p < 0.01; η2 = 0.14), anxiety (F[2, 98] = 5.10; p < 0.01; η2 = 0.10), and stress (F[2, 99] = 7.72; p < 0.01; η2 = 0.14). The follow-up post-hoc analyses revealed significant differences between all the groups (p < 0.01) on all the measures.

Figure 1.

Means of the outcome measures assessed by the wellness activity level.

Qualitative Results

Nearly 74% of the respondents reported that they had engaged in activities related to wellness, mindfulness, or mental wellbeing since the declaration of the pandemic (Table 1). Eight themes regarding the type of wellness, mindfulness, or mental wellbeing activities emerged: engage in regular physical activities/exercises, practice meditation and yoga, engage support from family and friends, engage in religious activities, engage in hobbies, take time away from work, attend counseling sessions, and other (Table 3).

Table 3.

Open-ended comments regarding respondents’ activities related to wellness, mindfulness, or mental wellbeing.

| Themes | Quotes from Participants |

|---|---|

| Engage in regular physical activities/exercises | “Daily exercise.” “Increasing exercise.” “Rock climbing, dancing, rollerblading, cycling.” |

| Practice mindfulness, meditation, and yoga | “I engage in mindfulness exercises and try to relax more.” “Mindfulness activities and yoga.” “Meditating.” “Meditation and yoga.” |

| Engage support from family and friends | “The power of support from family and friends has been helping me through the challenging times.” “Spending time with family.” “Enjoying friends more often.” “Talking to friends and family more.” |

| Engage in religious activities | “Church activities.” “Praying more.” “Quiet time, church and Bible study.” |

| Engage in hobbies | “Creative hobbies (painting, music), journaling.” “Working on hobbies.” “Cooking hobby.” |

| Take time away from work | “Set aside time to not work.” “Taking time off to relax.” “Time off for leisure.” “Vacation to a cabin and lake house.” |

| Attend counseling sessions | “Regular counseling.” “Counseling.” |

| Other activities | “Being thankful for the gift of life.” “Music therapy.” “Going to comedy clubs.” “Running COVID coach app.” “Group debriefings.” |

Nearly 36% (55 of 155) of the participants provided responses to the wellness promotion question. Eight themes emerged as activities and resources that can promote wellness among physicians: administrative, program, and system modification; sustainable workload and time away from work; supportive work community; enhanced leadership; promotion and access to mental health resources; access to fitness programs; choice and control; and other activities (Table 4).

Table 4.

Open-ended comments regarding wellness promotion.

| Themes | Quotes from Participants |

|---|---|

| Administrative, program, and system modification | “Working EHR system, not having to fight with insurance companies.” “We are not secretaries, why we do so much secretarial work? Let staff do the secretarial work.” “Less busy work like HCA modules or compliance modules. These are unnecessary busy work type activities that health care administrators make us do that actually cause more burnout.” “Scribes.” |

| Sustainable workload and time away from work | “More reasonable resident work/call schedules, work life balance (currently non-existent).” “More time away from work to decompress.” “Time to take care of our physical and emotional health. We start residency healthy and pretty but look beaten up by the time we graduate. Not good.” “Maybe quarterly or monthly wellness half day to do something fun with other residents or catch up on work that may be piling up causing feelings of being overwhelmed.” |

| Supportive work community | “Faculty that cares about wellbeing of residents.” “Truly supporting residents.” “Scheduled by the program, dinners, relaxing events to kick back and enjoy spending time with others in similar situations.” “Better clinical support.” |

| Enhanced leadership | “Program leadership caring more.” “Leadership should lead by example.” “Support from leadership.” |

| Promotion and access to mental health resources | “For wellness to be integrated into residency training and not just a mandatory one-time checkbox.” “Time off for counseling.” “Easy access to mental health professionals.” “Free mental health from insurance.” |

| Access to fitness programs | “Exercise facility at work to help us engage in active lifestyle.” “Access to fitness.” “Discounted gym/exercise membership.” |

| Choice and control | “Dedicated time for us to work on ourselves.” “Free time to pursue one’s own wellness activities.” “Having at least one day off per week (as opposed to working multiple weeks and then having multiple days off)” “Quarterly gatherings with the residents in my program outside of work that includes spouses and children.” |

| Other activities | “Prayers, church service, family and friends.” “Money to buy fiction books! Hearing stories of attendings feeling the same way.” “Making patients more nice.” “Meditation.” |

DISCUSSION

Burnout among resident physicians was an area of concern that predated the COVID-19 pandemic with studies demonstrating up to 54% of resident physicians experienced burnout across all specialties.41,42 Our data suggested that the burnout rates within GME programs sponsored by a community based medical school were high during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this study, 65.8% of the resident physicians experienced at least one manifestation of professional burnout during COVID-19 compared to 51% prior to the pandemic.17 The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress was 41.3%, 48.4%, and 36.8%, respectively. The resident physicians who experience at least one manifestation of burnout were more likely to report greater levels of negative emotional state. Specifically, the resident physicians who experienced burnout, compared to those who did not, were seven times more likely to report higher levels of emotional exhaustion, even after we adjusted for the covariates. These findings suggested that resident physicians are “covidout”. While the negative effects of the pandemic are not limited to a specific medical specialty as our survey covered 13 medical specialties, the high rates of burnout and other forms of emotional distress among the respondents further validates the call to understand and address burnout within GME programs.43,44

Our study sought to assess potential mitigating factors of negative mental health related to the COVID-19 pandemic on resident physicians. Almost 74% of resident physicians in our data indicated that they engaged in activities related to wellness since the start of the pandemic, and those resident physicians were less likely to experience burnout and other forms of emotional distress than those who reported no engagement in wellness-related activities. This finding suggested that wellness activities can make a difference in mitigating burnout and other types of emotional distress, such as emotional exhaustion, depression, anxiety, and stress.9–11,37,45 However, wellness activities alone may not be sufficient to address this problem, particularly as 51% of participants had no change or increase in wellness activities and yet burnout remained high across the population. Greater resources within hospitals and institutional systems are needed.

The qualitative data regarding activities related to wellness provided insight into the resident physicians’ personal experience. Several common themes of wellness, mindfulness, and mental wellbeing activities emerged from the analysis of qualitative data. This information should be explored further to assess for effectiveness as physician support and resilience initiatives. The qualitative data regarding ideas to promote greater wellness, were consistent with the National Academy of Medicine’s burnout framework aimed to promote wellbeing and resilience among physicians.46 The qualitative comments suggested recognition for individual action on the part of the resident physicians to use the available resources, including discounted gym membership, time off for counseling, and easy access to mental health professionals. An opportunity exists for local partners to promote availability of these resources to the resident physicians.

The comments echoed the need for administrative and system modification, including enhanced leadership. For example, the requests to improve electronic health record and ensure better clinical support highlighted areas where healthcare as a system can improve to support all physicians, including resident physicians. A reframing of expectations for managing wellness may be critical to ensure that both individual and system solutions are considered as the problem of burnout and other forms of emotional distress is addressed.

Study Limitations

This study had limitations. First, the study was limited to 13 community-based residency programs sponsored by a medical school in the Midwestern United States, so the findings may not be generalizable to other areas. Second, the cross-sectional nature and inability to establish a direct causal relationship between COVID-19 and psychological distress reduced the generalizability of the results. Third, data were collected via a self-reported online survey, which may have allowed for recall and selection biases. Fourth, data regarding respondents’ wellness and mindfulness activities were subjective. Additional studies evaluating the effectiveness of such activities on mental health symptoms are needed. Finally, given the size of our programs we could not report specialty-specific programs’ burnout scores without compromising anonymity.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic posed a significant rate of burnout and other negative mental health effects on resident physicians. These findings indicated a particularly timely need for further advances in implementing appropriate wellness and mental health support initiatives at local, state, and national levels to help reduce the negative impact of the pandemic on medical trainees and all health care professional.

APPENDIX

Survey on How Graduate Medical Trainees are Responding to COVID-19

-

Since the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020), have you engaged in any activities related to your wellness, mindfulness, or mental wellbeing?

Yes___ No___

If yes, please describe the wellness, mindfulness, or mental wellbeing activities in which you have engaged since the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 ____

-

How has your participation in these wellness, mindfulness, or mental wellbeing activities changed compared to before the pandemic?

Increased

No Change

Decreased

-

For each of the following statements, please check the box that most accurately reflects your response:

I feel burned out from my work as a result the COVID-19 pandemic

I’ve become more calloused towards people as a result the COVID-19 pandemic

The rating scale is as follows:

0. Never

1. A few times a year

2. Once a month or less

3. A few times a month

4. Once a week

5. A few times a week

6. Every day

-

For each statement below, please indicate how you have been feeling during the past week:

I found it hard to wind down

I tended to over-react to situations

I felt that I was using a lot of nervous energy

I found myself getting agitated

I found it difficult to relax

I was intolerant of anything that kept me from getting on with what I was doing

I felt that I was rather touchy

I was aware of dryness of my mouth

I experienced breathing difficulty (e.g., excessively rapid breathing, breathlessness in the absence of physical exertion)

I experienced trembling (e.g., in the hands)

I was worried about situations in which I might panic and make a fool of myself

I felt I was close to panic

I was aware of the action of my heart in the absence of physical exertion (e.g., sense of heart rate increase, heart missing a beat)

I felt scared without any good reason

I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feeling at all

I found it difficult to work up the initiative to do things

I felt that I had nothing to look forward to

I felt downhearted and blue

I was unable to become enthusiastic about anything

I felt I wasn’t worth much as a person

I felt that life was meaningless

The rating scale is as follows:

0. Did not apply to me at all

1. Applied to me to some degree, or some of the time

2. Applied to me to a considerable degree or a good part of time

3. Applied to me very much or most of the time

-

Please identify your specialty

Anesthesiology

Family Medicine

Internal Medicine

Medicine/Pediatrics

Obstetrics/Gynecology

Orthopaedic Surgery

Pediatrics

Psychiatry

Radiology

Sports Medicine

Surgery

-

Please identify your PGY level

PGY 1

PGY 2

PGY 3

PGY 4

PGY 5

-

What is your gender?

Male

Female

Prefer to not answer

Other (please specify)

What year were you born? ___

What resources and/or activities would help professionals like you in promoting wellness?

REFERENCES

- 1.Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, et al. First case of 2019 novel corona-virus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.David J. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sencer CDC Museum. Association with the Smithsonian Institution; [Accessed November 30, 2021]. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/index.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noseworthy J, Madara J, Cosgrove D, et al. Physician burnout is a public health crisis: A message to our fellow health care CEOs. [Accessed January 30, 2022];Health Affairs Blog. 2017 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20170328.059397/full/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ofei-Dodoo S, Moser SE, Kellerman R, Wipperman J, Paolo A. Burnout and other types of emotional distress among medical students. Med Sci Educ. 2019;29(4):1061–1069. doi: 10.1007/s40670-019-00810-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, et al. Burnout during residency training: A literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(2):236–242. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00054.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):334–341. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443–451. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maslach C, Leiter MP. New insights into burnout and health care: Strategies for improving civility and alleviating burnout. Med Teach. 2017;39(2):160–163. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1248918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oreskovich MR, Kaups KL, Balch CM, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2012;147(2):168–174. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hakanen JJ, Schaufeli WB. Do burnout and work engagement predict depressive symptoms and life satisfaction? A three-wave seven-year prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2–3):415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, et al. Special report: Suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):54–62. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Trojanowski L. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e015141. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weigl M, Schneider A, Hoffmann F, Angerer P. Work stress, burnout, and perceived quality of care: A cross-sectional study among hospital pediatricians. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(9):1237–1246. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2529-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shirom A, Nirel N, Vinokur AD. Overload, autonomy, and burnout as predictors of physicians’ quality of care. J Occup Health Psychol. 2006;11(4):328–342. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halbesleben JR, Rathert C. Linking physician burnout and patient outcomes: Exploring the dyadic relationship between physicians and patients. Health Care Manage Rev. 2008;33(1):29–39. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000304493.87898.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anagnostopoulos F, Liolios E, Persefonis G, Slater J, Kafetsios K, Niakas D. Physician burnout and patient satisfaction with consultation in primary health care settings: Evidence of relationships from a one-with-many design. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012;19(4):401–410. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ofei-Dodoo S, Callaway P, Engels K. Prevalence and etiology of burnout in a community-based graduate medical education system: A mixed-methods study. Fam Med. 2019;51(9):766–771. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.431489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai C. Personal risk and societal obligation amidst COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1555–1556. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tangcharoensathien V, Bassett MT, Meng Q, Mills A. Are overwhelmed health systems an inevitable consequence of COVID-19? Experiences from China, Thailand, and New York State. BMJ. 2021;372:n83. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Public Radio. [Accessed January 29, 2022];A COVID Surge Is Overwhelming U.S Hospitals Raising Fears of Rationed Care. 2021 September 5; https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2021/09/05/1034210487/covid-surge-overwhelming-hospitals-raising-fears-rationed-care . [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kannampallil TG, Goss CW, Evanoff BA, Strickland JR, McAlister RP, Duncan J. Exposure to COVID-19 patients increases physician trainee stress and burnout. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jalili M, Niroomand M, Hadavand F, Zeinali K, Fotouhi A. Burnout among healthcare professionals during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2021;94(6):1345–1352. doi: 10.1007/s00420-021-01695-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Restor Dent Endod. 2017;42:152–155. doi: 10.5395/rde.2017.42.2.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Single item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are useful for assessing burnout in medical professionals. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(12):1318–1321. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1129-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. 2nd ed. Sydney, Australia: Psychology Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gomez F. [Accessed September 15, 2021];A guide to the depression, anxiety, and stress scale (DASS 21) https://jeanmartainnaturopath.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Dass21.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osman A, Wong JL, Bagge CL, Freedenthal S, Gutierrez PM, Lozano G. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21): Further examination of dimensions, scale reliability, and correlates. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68(12):1322–1338. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rafferty JP, Lemkau JP, Purdy RR, Rudisill JR. Validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory for family practice physicians. J Clin Psychol. 1986;42(3):488–492. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198605)42:3<488::aid-jclp2270420315>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanste O, Miettunen J, Kyngäs H. Factor structure of the Maslach Burnout Inventory among Finnish nursing staff. Nurs Health Sci. 2006;8(4):201–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2006.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vanheule S, Rosseel Y, Vlerick P. The factorial validity and measurement invariance of the Maslach Burnout Inventory for human services. Stress Health. 2007;23(2):87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 32.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1445–1452. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2015-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ofei-Dodoo S, Loo-Gross C, Kellerman R. Burnout, depression, anxiety, and stress among family physicians in Kansas responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(3):522–530. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.03.200523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job Burnout. In: Fiske ST, Schachter DL, Zahn-Waxer C, editors. Annual Review of Psychology. Vol. 53. 2001. pp. 397–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ofei-Dodoo S, Mullen R, Pasternak A, et al. Loneliness, burnout, and other types of emotional distress among family medicine physicians: Results from a national survey. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(3):531–541. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.03.200566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ofei-Dodoo S, Kellerman R, Gilchrist K, Casey EM. Burnout and quality of life among active member physicians of the Medical Society of Sedgwick County. Kans J Med. 2019;12(2):33–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ofei-Dodoo S, Cleland-Leighton A, Nilsen K, Cloward JL, Casey E. Impact of a mindfulness-based, workplace group yoga intervention on burnout, self-care, and compassion in health care professionals: A pilot study. J Occup Environ Med. 2020;62(8):581–587. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borkan J. Immersion/Crystallization. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Clinical Research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 340–352. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Data Star, Inc. [Accessed October 3, 2022];What Every Researcher Should Know About Statistical Significance. 2008 October; https://dta0yqvfnusiq.cloudfront.net/datastarsurveys/2017/01/significance-170127-588b78de8466d.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodrigues H, Cobucci R, Oliveira A, et al. Burnout syndrome among medical residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0206840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blanchard AK, Podczerwinski J, Twiss MF, Norcott C, Lee R, Pincavage AT. Resident well-being before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(6):858–862. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-21-00325.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Summary of Changes to ACGME Common Program Requirements Section VI. [Accessed January 29, 2022]. http://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Common-Program-Requirements/Summary-of-Proposed-Changes-to-ACGME-Common-Program-Requirements-Section-VI .

- 44.Byrne LM, Nasca TJ. Population health and graduate medical education: Updates to the ACGME’s Common Program Requirements. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(3):357–361. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-19-00267.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amanullah S, Ramesh Shankar R. The impact of COVID-19 on physician burnout globally: A review. Healthcare (Basel) 2020;8(4):421. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8040421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Academy of Medicine. [Accessed January 25, 2022];Action Collaborative on Clinical Well-Being and Resilience. https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/ [Google Scholar]