Abstract

Canonically, Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 (EZH2) serves as the catalytic subunit of PRC2, mediating H3K27me3 deposition and transcriptional repression. Here we report that, in acute leukaemias, EZH2 has additional noncanonical functions by binding cMyc at non-PRC2 targets where EZH2 uses a hidden transactivation domain (TAD) for (co)activator recruitment and gene activation. Both canonical (EZH2-PRC2) and noncanonical (EZH2-TAD-cMyc-coactivators) activities of EZH2 promote oncogenesis, explaining the slow and ineffective antitumor effect by EZH2’s catalytic inhibitors. To suppress EZH2’s multifaceted activities, we employed Proteolysis Targeting Chimera (PROTAC) and developed a degrader, MS177, which achieved effective, on-target depletion of EZH2 and interacting partners (i.e., both canonical EZH2-PRC2 and noncanonical EZH2-cMyc complexes). Compared to EZH2’s enzymatic inhibitors, MS177 is fast-acting and much more potent in suppressing cancer growth. This study reveals noncanonical oncogenic roles of EZH2, reports a PROTAC for targeting EZH2’s multifaceted tumorigenic functions, and presents an attractive strategy for treating EZH2-depdendent cancers.

Keywords: EZH2, PRC2, cMyc, H3K27me3, PROTAC, leukaemia, MLL, cancer

Introduction

The canonical function of Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 (EZH2) is to serve as the enzymatic subunit of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), which catalyzes histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) to maintain a gene-repressive chromatin state1, 2. EZH2 overexpression is associated with cancer progression and poor outcomes of patients3–6. Exquisite EZH2 dependencies have been demonstrated in various cancers4, 6–10. Targeting EZH2 represents an attractive anticancer strategy.

Inhibitors that target EZH2’s Su(var)3–9, Enhancer-of-zeste and Trithorax (SET) domain were developed11 such as EPZ-643812, 13, GSK12614, UNC199915, C2416 and CPI-120517. However, these inhibitors often exert the slow and/or partial cellular responses18, 19 (also see below), which likely stems from a failure in targeting EZH2’s non-catalytic functions. Besides PRC2, EZH2 can also recruit/bind non-PRC2 factors for modulating gene expression during oncogenesis10, 20. PRC2-independent functions of EZH2 have been associated with transcriptional activation rather than H3K27me3-related repression, as exemplified by EZH2’s interaction with non-PRC2 partners including androgen receptor and NF-κB in prostate10 and breast cancers21–23, respectively. Notably, non-PRC2-related activities of EZH2 are often methyltransferase-independent10, 20, 23–27. Thus, current EZH2 inhibitors, which only inhibit EZH2’s catalytic activity, may fail to suppress EZH2’s noncanonical activities.

Our studies of MLL1-rearranged (MLL-r) leukaemia, a genetically defined blood malignancy displaying poor prognosis28, 29, reveal that, besides canonical EZH2:PRC2-bound targets, EZH2 has additional noncanonical targets that lack H3K27me3 but contain the gene-activation-related markers including histone acetylation, RNA polymerase II (POL II) and coactivators. At noncanonical targets, EZH2 directly binds cMyc and coactivator (p300) via a cryptic transactivation domain (TAD), mediating gene activation and oncogenesis. Consequently, EZH2’s enzymatic inhibitors are generally ineffective in treating MLL-r leukaemias. To develop a strategy that suppresses EZH2’s multifaceted functions, we employed the Proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) technology30–33 and developed MS177, an EZH2-targeting PRTOAC degrader. Biochemical, cellular, genomic and animal studies demonstrate that MS177 effectively depletes both canonical EZH2:PRC2 and noncanonical EZH2:cMyc complexes and that MS177 is much more effective and fast-acting than EZH2’s catalytic inhibitors in killing tumor.

Results

EZH2 noncanonically binds sites with gene-active markers.

To systematically define gene-regulatory roles for EZH2 in MLL-r leukaemia, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) for EZH2 and H3K27me3, an enzymatic product characteristic of EZH2:PRC2, in two independent leukaemia lines with MLL-r, EOL-1 (harboring MLL partial tandem duplication) and MV4;11 (harboring MLL-AF4). A large majority of EZH2 peaks overlapped H3K27me3, which specify canonical EZH2:PRC2 sites (Extended Data Fig. 1a–d). Meanwhile, a subset of EZH2 sites lack H3K27me3 (29% and 32% in EOL-1 and MV4;11 cells, respectively), termed as EZH2-”solo”-binding sites (Extended Data Fig. 1a–d). To our surprise, interrogation of additional chromatin marks showed EZH2-”solo”-binding peaks overwhelmingly enriched for the gene-activation-related H3K4me3, H3K27ac and H3K9ac, in contrast to what was seen with the EZH2/H3K27me3-cobound peaks (Fig. 1a–d). To rule out potential artifact, we employed a second profiling method, CUT&RUN34, and cells stably expressing HA-tagged EZH2. CUT&RUN for HA-EZH2 in both EOL-1 and MV4;11 cells verified noncanonical and canonical EZH2 sites (Fig. 1a–d; HA-EZH2). EZH2-”solo”-binding sites identified from these two leukaemia cells showed significant overlap (Fig. 1e), indicating a conserved mechanism underlying EZH2-”solo”-binding formation. EZH2-”solo” peaks also exhibited significant co-localization with POL II, MLL (a writer of H3K4me3), BRD4 (a reader of histone acetylation) and SWI/SNF complexes (Fig. 1f–i), again indicating a role for gene activation. Thus, EZH2-”solo”-targeting sites exist in MLL-r leukaemias and are potentially involved in transcriptional activation, differing from canonical roles of EZH2:PRC2 for H3K27me3 deposition and gene repression.

Fig. 1|. EZH2 exhibits noncanonical PRC2-indepedent solo-binding in leukaemias.

Besides its canonical H3K27me3 cobound pattern, EZH2 exhibits additional noncanonical solo-binding at sites enriched for gene-activation-related histone marks, Pol II, (co)activators and cMyc in MLL-r leukaemia cells. a-d, Averaged signal intensities (a-b) and heatmaps (c-d) for EZH2 (either endogenous EZH2 or exogenously expressed HA-tagged EZH2), H3K27me3, histone acetylation (H3K27ac or H3K9ac) and H3K4me3 ± 5 kb from the centers of noncanonical EZH2+/H3K27me3- peaks (i.e., EZH2-”solo”; top panels) or canonical EZH2+/H3K27me3+ peaks (i.e., EZH2 ensemble; bottom panels) in either MV4;11 (a, c) or EOL-1 (b, d) cells. Except HA-EZH2, which was mapped via CUT&RUN, all the others were mapped via ChIP-seq.

e, Venn diagram showing a significant overlap between EZH2-”solo”-binding sites identified in the two independent MLL-r leukaemia lines, MV4;11 and EOL-1.

f-i, Heatmap for ChIP-seq signals of EZH2, POL II (f), MLL (MLLn and MLLc, g), BRD4 (h) and SWI/SNF (SMARCA4 and SMARCC1, i) ± 5 kb from the centers of EZH2-”solo”-binding sites in MV4;11 or EOL-1 cells.

j, Significant enrichment of the Myc:MAX motif (CACGTG) at the EZH2-”solo” peaks in MV4;11 cells.

k-l, Co-IP for EZH2 (k) or cMyc (l) interaction with endogenous POL II, SMARCA4 and SMARCB1 in EOL-1 cells using anti-EZH2 or anti-cMyc antibodies.

m-n, Co-IP for endogenous EZH2 and cMyc interaction in EOL-1 cells using anti-EZH2 (m) or anti-cMyc antibodies (n). Classic PRC2 subunits, SUZ12 and EED, and MAX, the cMyc cofactor, were probed in IP samples.

o-p, GST pulldown for assaying interaction of the in vitro translated HA-cMyc protein with recombinant GST-EZH2 (o) or GST-EED (p) protein. GST alone (lane 1) serves as control. Red arrows indicate GST and GST-fusion protein.

q-r, Averaged ChIP-seq signal intensities (q) and heatmaps (r) for EZH2 and cMyc (using two independent antibodies, ab1 and ab2) ± 5 kb from the centers of noncanonical EZH2-”solo” peaks (left) or canonical EZH2 ensemble peaks (right) in MV4;11 (top) or EOL-1 (bottom) cells.

s, Heatmaps for EZH2, H3K27me3, cMyc and H3K27ac signal intensities, detected by CUT&RUN in the MLL-AF9+ AML PDX cells, ± 5 kb from the centers of either EZH2-”solo” (top) or EZH2 ensemble (bottom) sites identified in MLL-AF4+ MV4;11 cells.

EZH2-’solo’ sites are bound by oncoproteins, notably cMyc.

Motif search analysis using EZH2-’solo’ peaks revealed enrichment for consensus binding sites of basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factor (TF), such as CACGTG (a canonical cMyc site) and CAGCTG (a non-cMyc bHLH TF site), and motifs of the ETS family TFs (Fig. 1j and Extended Data Fig.1e). Previous studies showed that cMyc-binding sites do not correlate well with the presence of high-affinity cMyc motifs35–39 and that low-affinity motifs including CAGCTG are enriched at cMyc-binding sites, indicating complex recruitment mechanisms35; moreover, cMyc is colocalized with basal transcription apparatus and/or chromatin-modulatory proteins such as POL II, P-TEFb, NuA4/TIP60, TRRAP, SWI/SNF and WDR5/MLL complexes, due to direct or indirect interactions36, 38–44. As same sets of (co)activators were found enriched at EZH2-’solo’ sites in leukaemia cells, we thus tested biochemical association among EZH2, cMyc and (co)activators.

First, co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) detected interaction of EZH2 with p300, SWI/SNF and POL II, similar to what was observed for cMyc (Fig. 1k–l and Extended Data Fig. 1f). Additionally, EZH2, expressed endogenously or exogenously, interacted with cMyc:MAX (Fig. 1m–n and Extended Data Fig. 1g–j) and this association was intact under cell treatment with benzonase and ethidium bromide (Extended Data Fig. 1g), indicating a DNA-independent interaction. Recombinant EZH2 also bound to cMyc efficiently (Fig. 1o). Interestingly, EZH2 bound both PRC2 subunits and cMyc:MAX (Fig. 1m), whereas cMyc:MAX interacted with EZH2 only, and not other PRC2 components, in co-IP and GST pulldown assays (Fig. 1n–p). These observations suggest that EZH2 association with cMyc is PRC2-independent and occurs at EZH2-’solo’-binding sites.

Next, we performed CUT&RUN for cMyc in EOL-1 and MV4;11 cells using independent anti-cMyc antibodies, which produced highly correlated results (Extended Data Fig. 1k). Indeed, significant co-localization of cMyc was seen at the EZH2-’solo’-binding sites, and not EZH2:H3K27me3-cobound PRC2 peaks (Fig. 1q–r). About 50% of EZH2:cMyc-cobound peaks are located at promoters (Extended Data Fig. 1l), consistent with association of cMyc with basal transcription apparatus and (co)activators36, 38–44. To further verify our finding in a model that closely resembles the clinic setting, we conducted CUT&RUN with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) patient-derived xenograft (PDX) cells that harbor MLL-AF9 and found the similar EZH2:cMyc co-binding at those EZH2-’solo’ sites identified from MV4;11 cells, which are again featured with high H3K27ac and no/low H3K27me3 (Fig. 1s, top); meanwhile and as expected, those canonical EZH2:PRC2-bound sites identified from MV4;11 cells exhibited high H3K27me3 and no/low H3K27ac in PDX cells (Fig. 1s, bottom).

Collectively, co-targeting of EZH2 and cMyc onto noncanonical EZH2 sites exists among independent MLL-r leukaemia models. Interestingly, additional analyses using public datasets of three normal or non-AML cell types (i.e., GM12878 lymphoblasts, human umbilical vein endothelial cells [HUVEC] and K562 cells) showed an overwhelming pattern of EZH2:H3K27me3 colocalization and a lack of EZH2-”solo”:cMyc cobinding (Extended Data Fig. 1m), indicating that EZH2:cMyc association seen at noncanonical EZH2 sites in MLL-r leukaemias is likely associated with malignant transformation, which merits further investigation.

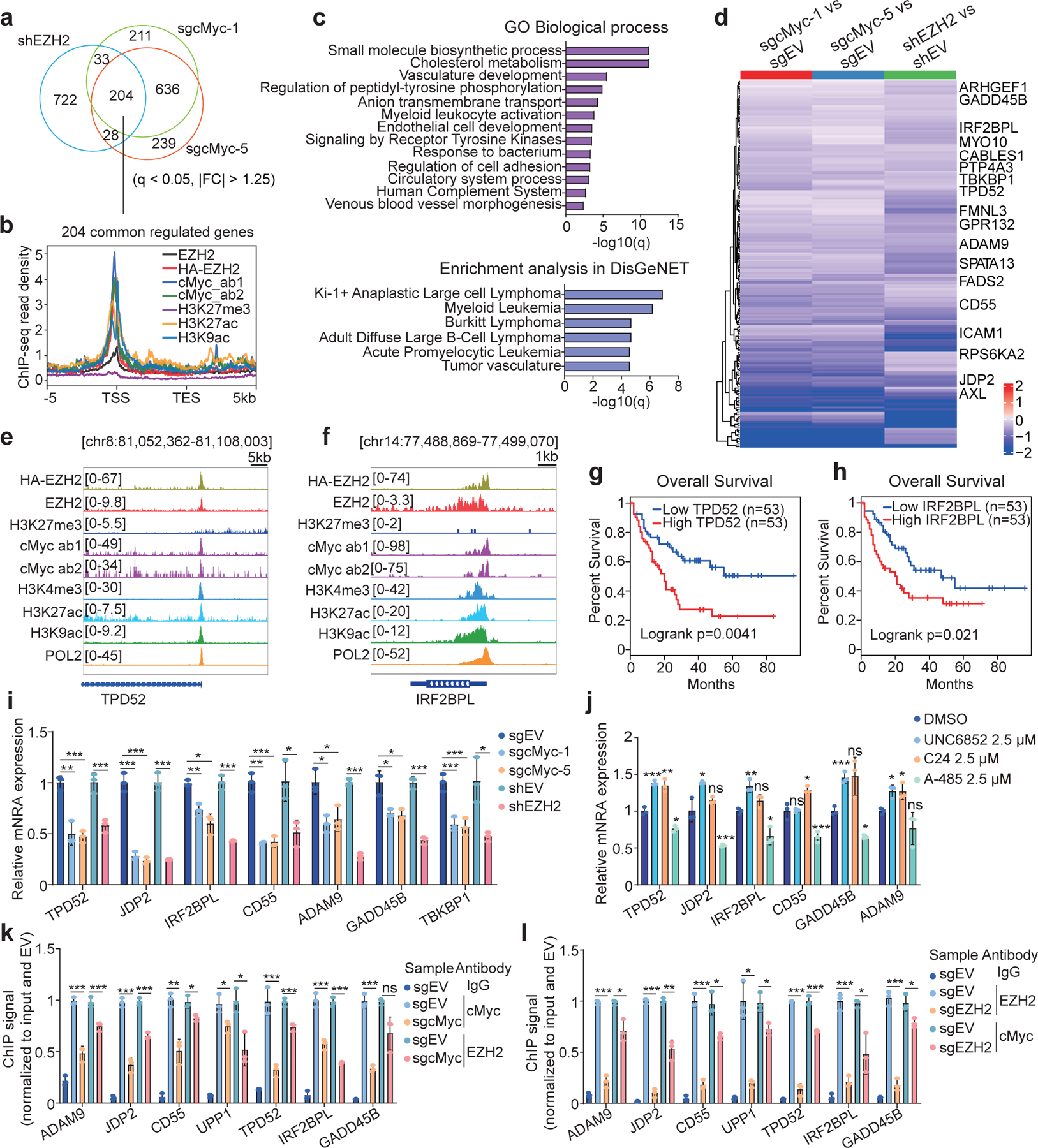

EZH2’s TAD directly interacts with cMyc and (co)activators.

To dissect gene-regulatory roles for EZH2 and cMyc in MLL-r leukaemias, we conducted RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) following their depletion. As expected, depletion of either EZH2 or cMyc significantly suppressed leukaemia cell growth (Extended Data Fig. 2a–d). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) showing down-regulation upon EZH2 or cMyc depletion displayed partial but significant overlap (~21–25%, P < 5.8e-92; Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 1). EZH2/cMyc co-upregulated genes exhibited co-binding of EZH2, cMyc, H3K27ac and H3K9ac while lacking H3K27me3 (Fig. 2b), consistent with gene-activation roles of EZH2 and cMyc at these targets. Gene ontology (GO) analysis showed the EZH2/cMyc-coregulated transcripts enriched for genes related to cell metabolism and leukaemia or lymphoma oncogenesis (Fig. 2c). RNA-seq analyses with or without the spike-in control normalization generated consistent results (Extended Data Fig. 2e–i). EZH2-”solo” bound genes were generally expressed at a level higher than EZH2:PRC2-targeted genes (Extended Data Fig. 2j–k). By integrating genome-binding and RNA-seq datasets, we further determined the EZH2:cMyc-coregulated genes directly cobound by EZH2-’solo’ and cMyc (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 2l), such as TPD52, IRF2BPL, GADD45B, CD55 and ADAM9, which exhibited cobinding of POL II and gene-active markers (H3K27ac, H3K9ac and H3K4me3) but lacked H3K27me3 (Fig. 2e–f and Extended Data Fig. 2m). Higher expression of TPD52 or IRF2BPL was found correlated with poorer prognosis of AML patients (Fig. 2g–h). By RT-PCR, we further showed that the expression of selected genes exhibiting EZH2-’solo’ and cMyc cobinding is dependent on both EZH2 and cMyc, largely insensitive to PRC2 blockade as shown by treatment of C24 (an EZH2 enzymatic inhibitor that erases global H3K27me3)16 or UNC6852 (an EED PROTAC that degrades PRC2)45, and yet significantly inhibited upon treatment of A-485, a p300/CBP inhibitor46 (Fig. 2i–j and Extended Data Fig. 2n–p). These results thus support the PRC2-independent gene-activation role for EZH2 and interacting coactivators. Also, cMyc depletion led to the concurrently decreased binding of cMyc and EZH2 to their co-targeted sites; conversely, EZH2 depletion also decreased both EZH2 and cMyc recruitment onto these same sites (Fig. 2k–l and Extended Data Fig. 2c,q). These results indicate cooperative recruitment of EZH2 and cMyc for target gene activation.

Fig. 2|. Cooperative EZH2 and cMyc recruitment to common targets leads to gene activation in leukaemia.

a, Venn diagram using differentially expressed genes (DEGs), down-regulated based on RNA-seq analysis after EZH2 knockdown (KD; shEZH2) or cMyc knockout (KO; by either sgcMyc-1 or sgcMyc-5) in MV4;11 cells (n = 2 biologically independent experiments). Threshold of DEG is set as adjusted DESeq P value (q) < 0.05, fold-change (FC) > 1.25 and mean tag counts > 10. |FC| indicates the absolute value of FC.

b, Averaged signal intensities of EZH2 (endogenous EZH2 or exogenously expressed HA-EZH2), cMyc, H3K27ac, H3K9ac and H3K27me3 around the genes co-upregulated by EZH2 and cMyc in MV4;11 cells (n = 204; defined in a). TSS, transcriptional start site; TES, transcriptional end site.

c, GO analysis (top) and enrichment of the DisGeNet category (bottom) using genes co-upregulated by EZH2 and cMyc shown in a.

d, Heatmap using the indicated RNA-seq sample comparison shows log2-converted ratios of the 204 genes co-upregulated by EZH2 and cMyc in MV4;11 cells (n = 2 biologically independent experiments). Genes with the EZH2-”solo”:cMyc co-binding are labeled. EV, empty vector.

e-f, IGV view of enrichment for the indicated factor at TPD52 (e) and IRF2BPL (f) in MV4;11 cells.

g-h, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis based on the TPD52 (g) or IRF2BPL (h) expression in patient samples of the TCGA AML cohort. Statistical significance was determined by log-rank test.

i-j, RT-qPCR for the indicated EZH2:cMyc-cotargeted gene following EZH2 KD or cMyc KO (i), or after a 24-hour treatment with 2.5 μM of UNC6852, C24 or A-485 (j), in MV4;11 cells. Y-axis shows averaged signals after normalization to GAPDH and to mock-treated (n = 3; mean ± SD; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

k-l, ChIP-qPCR for cMyc and EZH2 at the indicated EZH2:cMyc-cotargeted gene promoter in MV4;11 cells post-depletion of cMyc (k) or EZH2 (l). Y-axis shows averaged signals after normalization to input and then to EV controls (n = 3; mean ± SD; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

*, **, and *** denote the P value of < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.005, respectively. NS denotes not significant. Numerical source data, statistics and exact P values are available as source data.

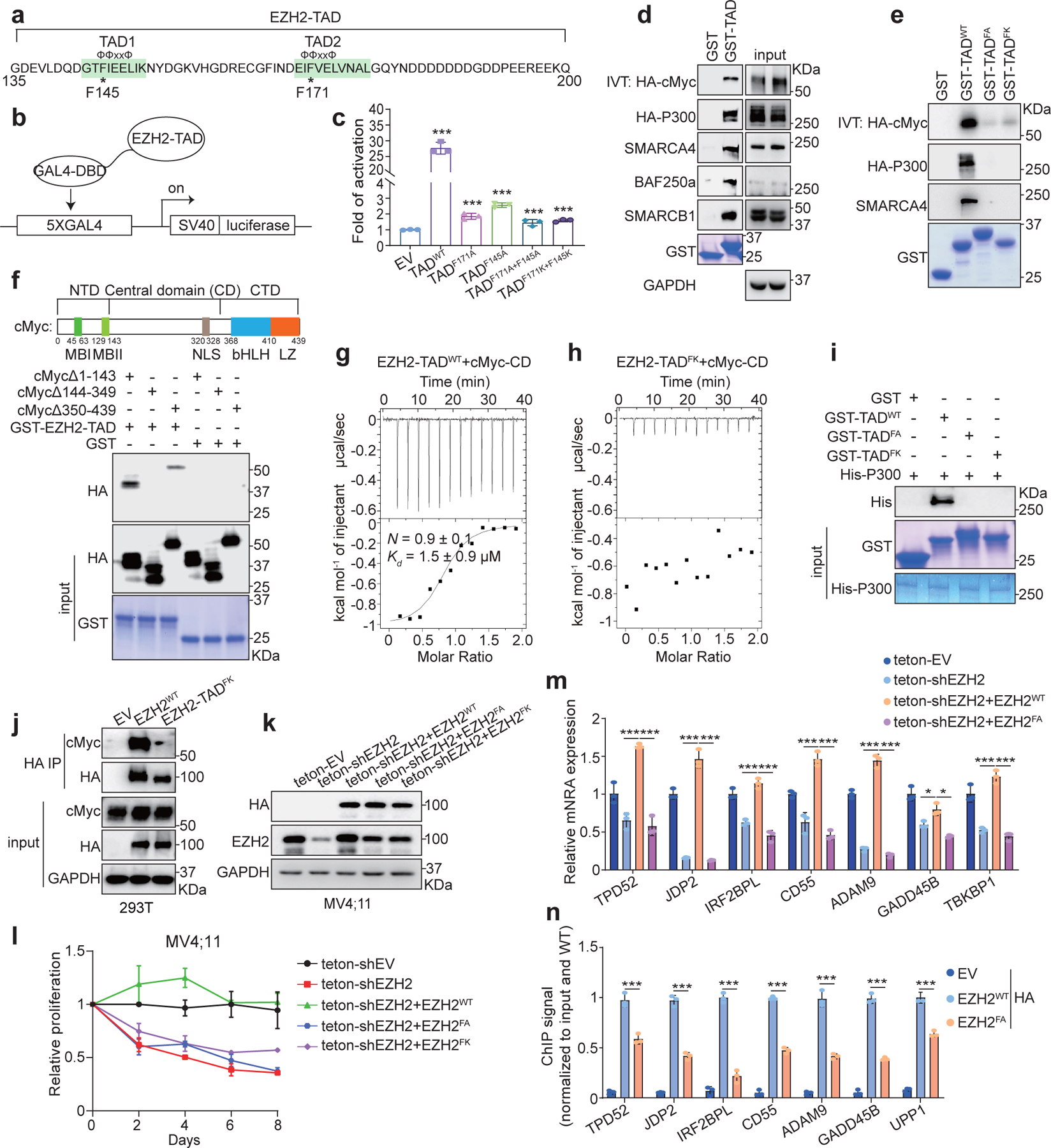

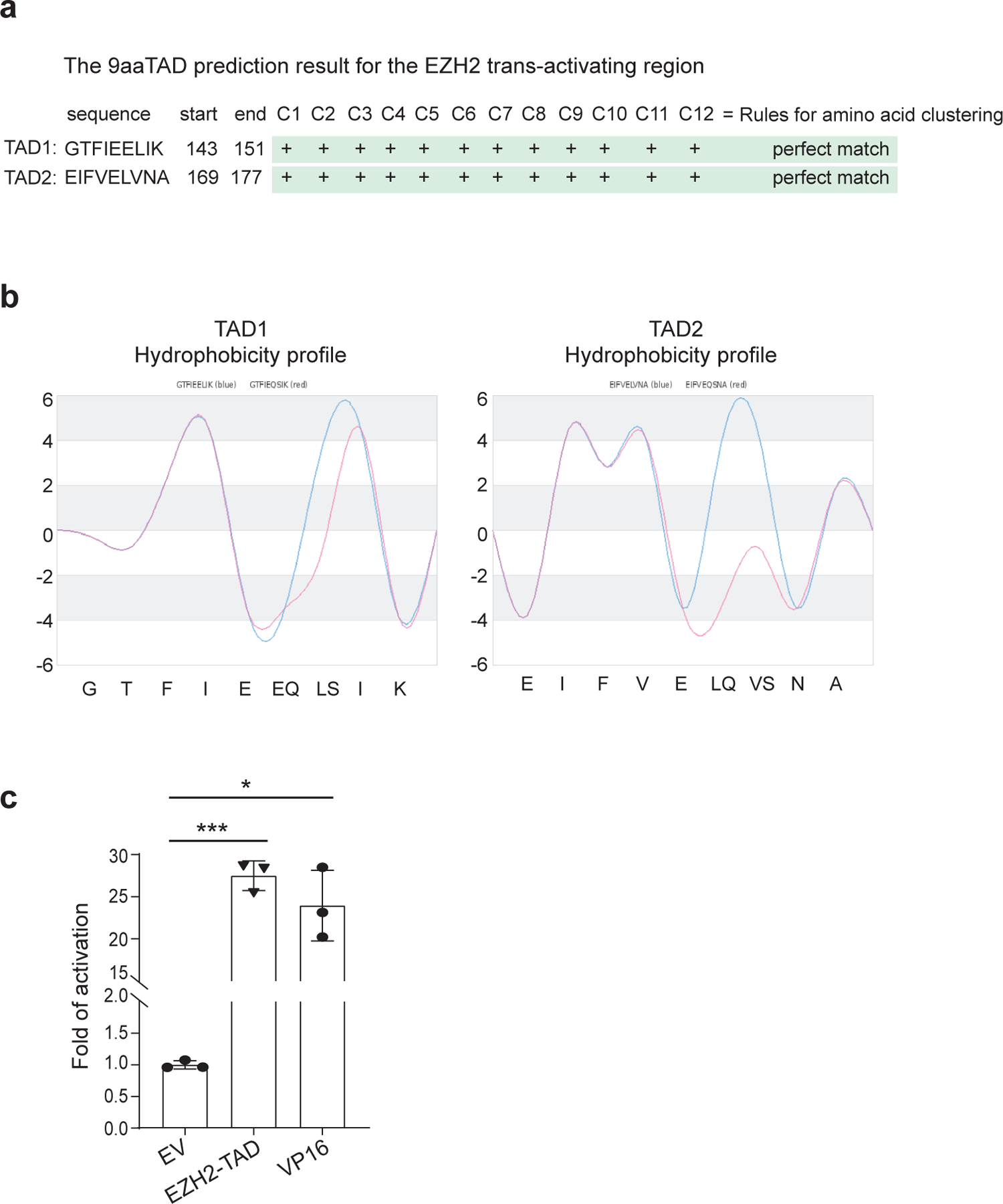

To dissect the mechanism underlying EZH2-mediated trans-activation, we analyzed its protein sequence with 9aaTAD47, a tool for predicting TAD. Consistent with a report48, putative TADs were identified within EZH2’s amino acids 135–200, which comprises two typical, partially disordered Φ-Φ-x-x-Φ motifs (Φ representing a hydrophobic residue and x being any residue; Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 3a–b). In luciferase reporter assays, EZH2-TAD and VP16-TAD displayed comparable transactivation capabilities (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 3c). Substitution of Phe145 or Phe171 in EZH2-TAD with alanine or lysine greatly reduced TAD-mediated transactivation, with the dual mutants exhibiting effect close to complete abolishment (Fig. 3c). In supporting a role for EZH2-TAD in gene activation, GST pulldown using recombinant EZH2-TAD protein readily detected interaction with cMyc, p300 and SWI/SNF complexes (Fig. 3d), in agreement with their co-occupancies at EZH2-’solo’-binding sites. Meanwhile, EZH2-TAD-dead mutations almost completely abrogated EZH2-TAD interaction with cMyc, p300 and SWI/SNF (Fig. 3e). Next, we mapped cMyc’s EZH2-interaction interface to its central domain (cMyc-CD; Fig. 3f). Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) further confirmed a direct binding between EZH2-TAD and cMyc-CD, with Kd measured to be ~1.5 µM, while the EZH2-TAD-dead mutant showed no detectable interaction with cMyc-CD (Fig. 3g–h). GST pulldown also verified the EZH2-TAD interaction with recombinant p300 (Fig. 3i).

Fig. 3|. EZH2 directly interacts with cMyc and coactivators via EZH2-TAD, promoting malignant growth of leukaemia cells.

a, EZH2-TAD, highlighted in green, contains typical Φ-Φ-x-x-Φ motifs, with asterisks indicating aromatic residues important for transactivation.

b-c, Schematic of GAL4-based luciferase reporter assays (b) and summary (c) of reporter activities of EZH2-TAD, either WT or mutant, compared to EV. Y-axis shows relative activation after normalization to internal control (Renilla luciferase) and then to EV-transduced mock (n = 3; mean ± SD; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test). DBD, DNA-binding domain.

d-e, Pull-down using GST alone or GST-EZH2-TAD, either WT (d) or TAD-dead-mutant (e), and the in vitro translated (IVT) protein of HA-cMyc or 293T cell lysate containing the transiently expressed HA-p300. FA, F145A+F171A; FK, F145K+F171K.

f, Domain organization of cMyc (top) and pull-down (bottom) using GST alone or GST-EZH2-TAD and 293T cell lysate containing the transiently expressed HA-cMyc with serial truncation. NTD, CD and CTD indicate the N-terminal, central and C-terminal domain, respectively.

g-h, ITC binding curve using recombinant EZH2-TAD, either WT (g) or TAD-dead-mutant (h), and purified cMyc-CD (n=3; means ± SD).

i, Pull-down using GST-EZH2-TAD, WT or mutant, and recombinant His6x-p300 protein.

j, Co-IP for endogenous cMyc and the stably expressed full-length HA-EZH2, either WT or TAD-dead-mutant, in 293T cells.

k-m, Immunoblotting of the indicated protein (k), cell proliferation (l) and RT-qPCR of EZH2:cMyc-coactivated genes (m) after doxycycline-induced depletion of endogenous EZH2 in MV4;11 cells, pre-rescued with exogenous shEZH2-resistant HA-EZH2, either WT or TAD-dead-mutant (FA or FK). Teton, doxycycline (dox)-inducible Tet-On vector. For l and m, n = 3, mean ± SD; for m, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used.

n, ChIP-qPCR of HA-EZH2, either WT or TAD-dead-mutant, at the indicated EZH2:cMyc-cotargeted gene using the same MV4;11 cells shown in k-m. Y-axis shows signals after normalization to those from input and then to WT HA-EZH2-transduced cells (n = 3; mean ± SD; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test). EV-transduced cells serve as a negative control.

*, **, and *** denote the P value of < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.005, respectively. NS denotes not significant. Numerical source data, statistics, exact P values and unprocessed blots are available as source data.

Collectively, EZH2-TAD forms direct interaction with (co)activtors including cMyc and p300, which underlies their cooperation in chromatin recruitment and gene activation seen at EZH2-’solo’ targets, some of which are the clinically relevant genes such as TPD52 and IRF2BPL.

EZH2-TAD is required for malignant growth of leukaemia cells.

Next, we assessed the requirement of EZH2-TAD for malignant growth. First, co-IP showed that cMyc associated with wildtype full-length EZH2, but not its TAD-dead mutant (Fig. 3j), indicating that EZH2-TAD is essential for cMyc interaction in cells. Genetic complementation using MV4;11 cells with endogenous EZH2 depleted demonstrated that wildtype but not TAD-dead EZH2 rescued growth defect (Fig. 3k–l). Compared to wildtype, the TAD-dead EZH2 also exhibited defects in gene activation and binding to the EZH2-”solo” targets (Fig. 3m–n). Thus, EZH2:cMyc:(co)activator complex-mediated activation of noncanonical EZH2 targets is crucial for malignant growth of MLL-r AML.

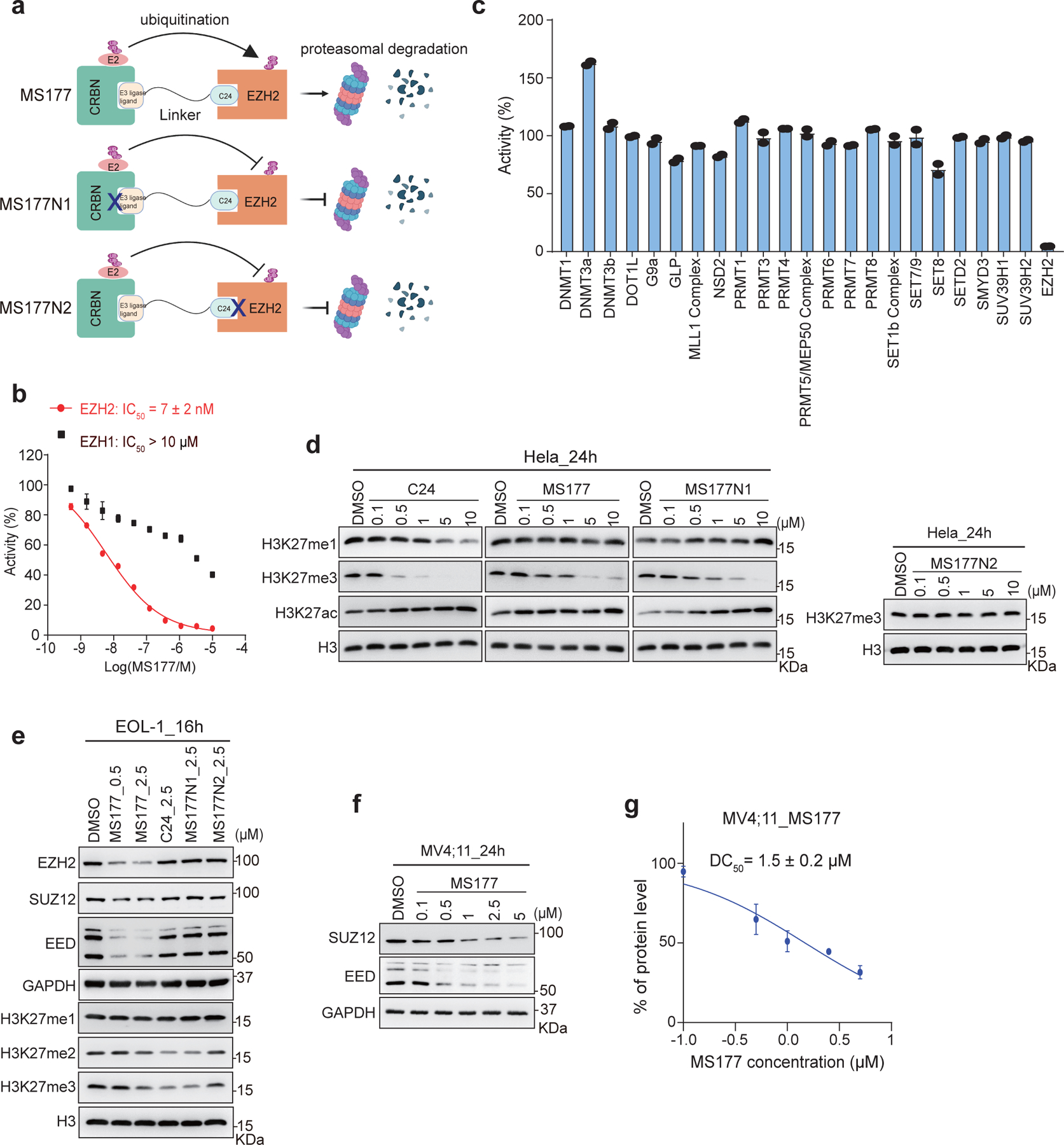

Development of an EZH2-targeting PROTAC degrader, MS177.

EZH2 is essential for oncogenesis of MLL-r leukaemias8, 9, 49. However, C24 (Fig. 4a, left), a potent enzymatic inhibitor of EZH2 with a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 12 nM16, had little to very mild growth-suppressive effect on a panel of MLL-r leukaemia lines (Extended Data Fig 4a). Such a poor tumor-killing effect is likely due to the failure of C24 in targeting EZH2’s noncanonical functions, such as EZH2:cMyc-mediated activation of nonconventional targets, which we showed to be TAD-dependent and PRC2-independent.

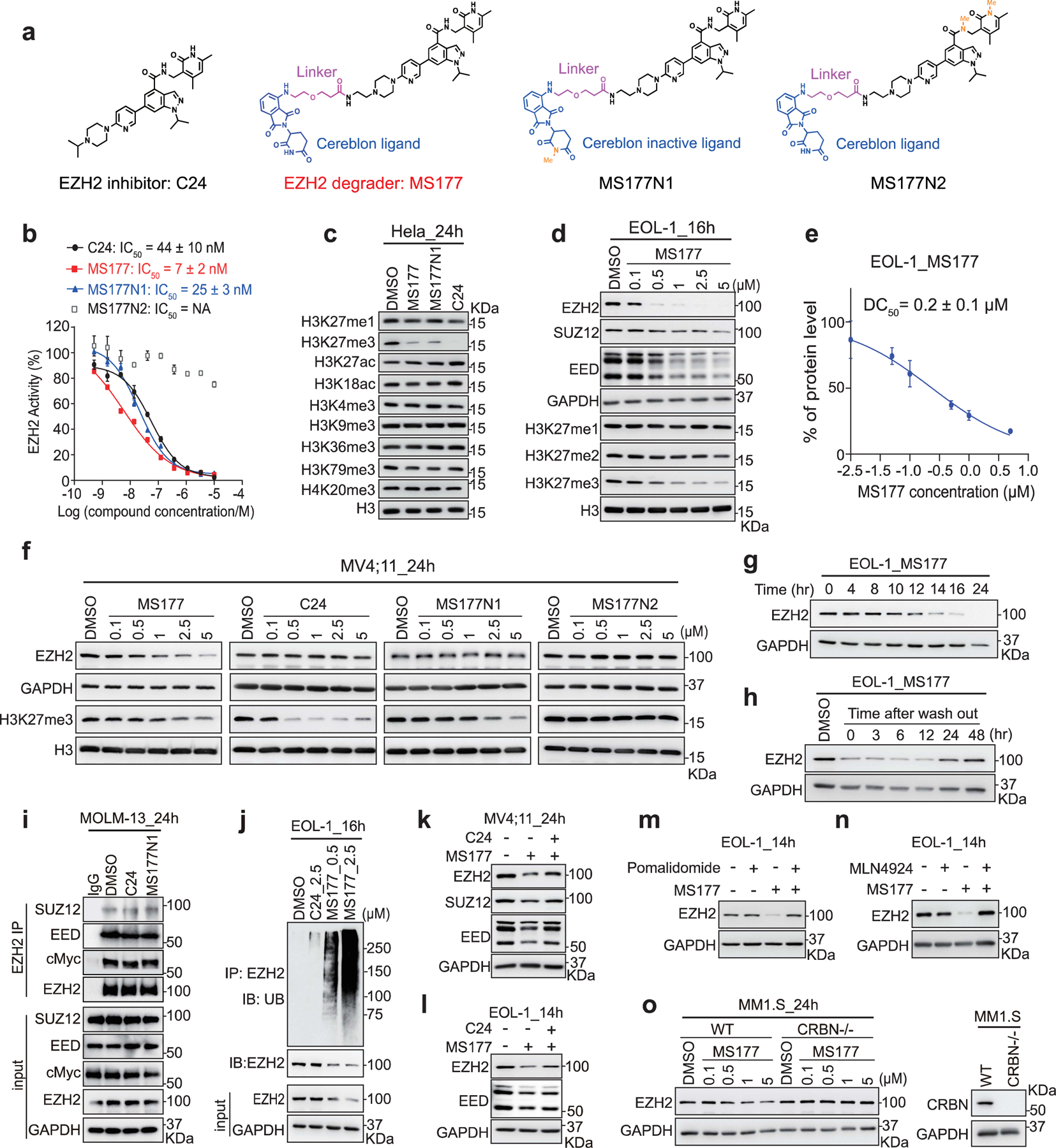

Fig. 4|. Characterization of the EZH2-targeting PROTAC, MS177.

a, Structure of C24, MS177, MS177N1 and MS177N2.

b, EZH2-inhibitory effect of the indicated compound in the in vitro methyltrasferase assay (n= 2; mean ± SD).

c, Immunoblotting of various histone modifications in HeLa cells after a 24-hour treatment with the indicated compound (5 µM).

d, Immunoblotting of PRC2 subunits and H3K27 methylation in EOL-1 cells, treated with the indicated concentration of MS177, versus DMSO, for 16 hours.

e, Measurement of DC50 value of MS177, based on EZH2 immunoblotting signals in EOL-1 cells after treatment (n=2; mean ± SD).

f, Immunoblotting of EZH2 and H3K27me3 in MV4;11 cells after the indicated compound treatment for 24 hours.

g, Time-dependent EZH2 depletion by MS177 (5 µM) in EOL-1 cells.

h, EZH2 immunoblotting in EOL-1 cells first treated with 0.5 µM of MS177 for 16 hours, followed by MS177 washout for the indicated time.

i, Co-IP for EZH2 interaction with endogenous PRC2 and cMyc in MOLM-13 cells, treated with 2.5 µM of DMSO, C24 and MS177N1 for 24 hours. IgG (lane 1) serves as IP control.

j, Upper: Ubiquitin (UB) immunoblotting (IB) after IP with anti-EZH2 antibodies using EOL-1 cells after the indicated compound treatment for 16 hours. Bottom: immunoblotting using input.

k-l, Immunoblotting of PRC2 subunits in MV4;11 (k) and EOL-1 (l) cells pre-treated with DMSO (lanes 1–2) or C24 (0.5 µM; lane 3) for 2 hours, and then subjected to an additional treatment with DMSO or 2.5 µM of MS177 for 24 (k) or 14 hours (l).

m-n, EZH2 immunoblotting using EOL-1 cells pre-treated with DMSO (lanes 1 and 3), pomalidomide (2.5 µM, m; lanes 2 and 4) or MLN4924 (0.4 µM, n; lanes 2 and 4) for 2 hours, and then subjected to an additional 14-hour treatment with DMSO (lanes 1–2) or MS177 (0.5 µM, lanes 3–4).

o, Left: EZH2 immunoblotting using MM1.S cells, either wild-type (left) or with CRBN KO (CRBN-/-; right), after a 24-hour treatment with the indicated concentration of MS177. Right: Immunoblot showing CRBN KO.

Numerical source data and unprocessed blots are available as source data.

A different strategy is needed to target both canonical and noncanonical tumorigenic activities of EZH2, and we employed the PROTAC technology. The piperazine moiety of C24 is solvent-exposed, presenting a handle for connecting an E3 ligase ligand without interfering with EZH2 binding16, 50. Testing of various putative EZH2 PROTAC degraders led to the identification of MS177, an effective EZH2-targeting PROTAC, which consists of pomalidomide, a CRBN ligand51, conjugated to C24 via a short polyethylene glycol (PEG) linker (Fig. 4a). We also designed and synthesized two structurally similar analogs of MS177, MS177N1 and MS177N2 (Fig. 4a), as controls. MS177N1 was designed to disrupt CRBN binding while maintaining EZH2 binding by adding a methyl group to the glutarimide moiety of pomalidomide52. MS177N2 was designed to abolish EZH2 binding without affecting CRBN binding by adding two methyl groups to the C24 portion of MS17715, 16, 50. Thus, MS177, but not MS177N1 or MS177N2, would induce EZH2 degradation (Extended data Fig. 5a). First, we showed that C24, MS177 and MS177N1 all displayed comparable high potency for inhibiting EZH2:PRC2 in vitro, whereas MS177N2 exhibited no significant inhibition (Fig. 4b). Similar to C24, MS177 retained high selectivity for EZH2 over EZH1 and other unrelated methyltransferases (Extended Data Fig. 5b–c) and a panel of common drug targets including kinases, G protein-coupled receptors, ion channels and transporters (Supplementary Tables 2–3). In HeLa cells, C24, MS177 and MS177N1, but not MS177N2, also inhibited EZH2:PRC2’s enzymatic activities, decreased H3K27me3 and increased H3K27ac, without affecting other tested histone modifications (Extended Data Fig. 5d; Fig. 4c). Collectively, MS177 is a potent and selective EZH2-targeting compound.

MS177 effectively degrades cellular EZH2:PRC2.

We next assessed MS177’s effect on degrading EZH2 in cells. First, we observed that, in multiple MLL-r leukaemia cells, MS177 depleted EZH2, EED and SUZ12 in a concentration- and time-dependent fashion, an effect not seen with C24, MS177N1 or MS177N2 (Fig. 4d–g and Extended Data Fig. 5e–f). Cellular EZH2 level was found restored 24 hours post-washout of MS177 (Fig. 4h). As expected, treatment with MS177, MS177N1 or C24, but not MS177N2, suppressed global H3K27me3 in leukaemia cells (Fig. 4d and f, and Extended Data Fig. 5e). In EOL-1 and MV4;11 cells, MS177 exhibited half-maximal degradation concentration (DC50) values of 0.2±0.1 µM and 1.5±0.2 µM, and maximum degradation (Dmax) values of 82% and 68%, respectively (Fig. 4e and Extended Data Fig. 5g).

We next assessed MS177’s mechanism of action (MOA) for EZH2 degradation. First, Co-IP showed that neither C24 nor MS177N1 treatment interfered with PRC2:EZH2 or EZH2:cMyc interaction (Fig. 4i). In agreement with MS177 being a PROTAC, cellular EZH2 was found ubiquitinated post-treatment with MS177, but not C24 (Fig. 4j). Pre-treatment of cells with C24 attenuated the MS177-induced PRC2:EZH2 depletion (Fig. 4k–l). Also, the MS177-induced EZH2 degradation was effectively blocked by pre-treatment with the CRBN ligand, pomalidomide (Fig. 4m) or MLN4924 (which suppresses assembly of Cullin-based E3 ligase53; Fig. 4n). Lastly, CRBN knockout (KO) also almost completely abrogated the MS177-induced EZH2 depletion (Fig. 4o). Thus, MS177 is a bone fide CRBN-dependent, EZH2-targeting PROTAC that effectively degrades EZH2 and associated PRC2 in cells.

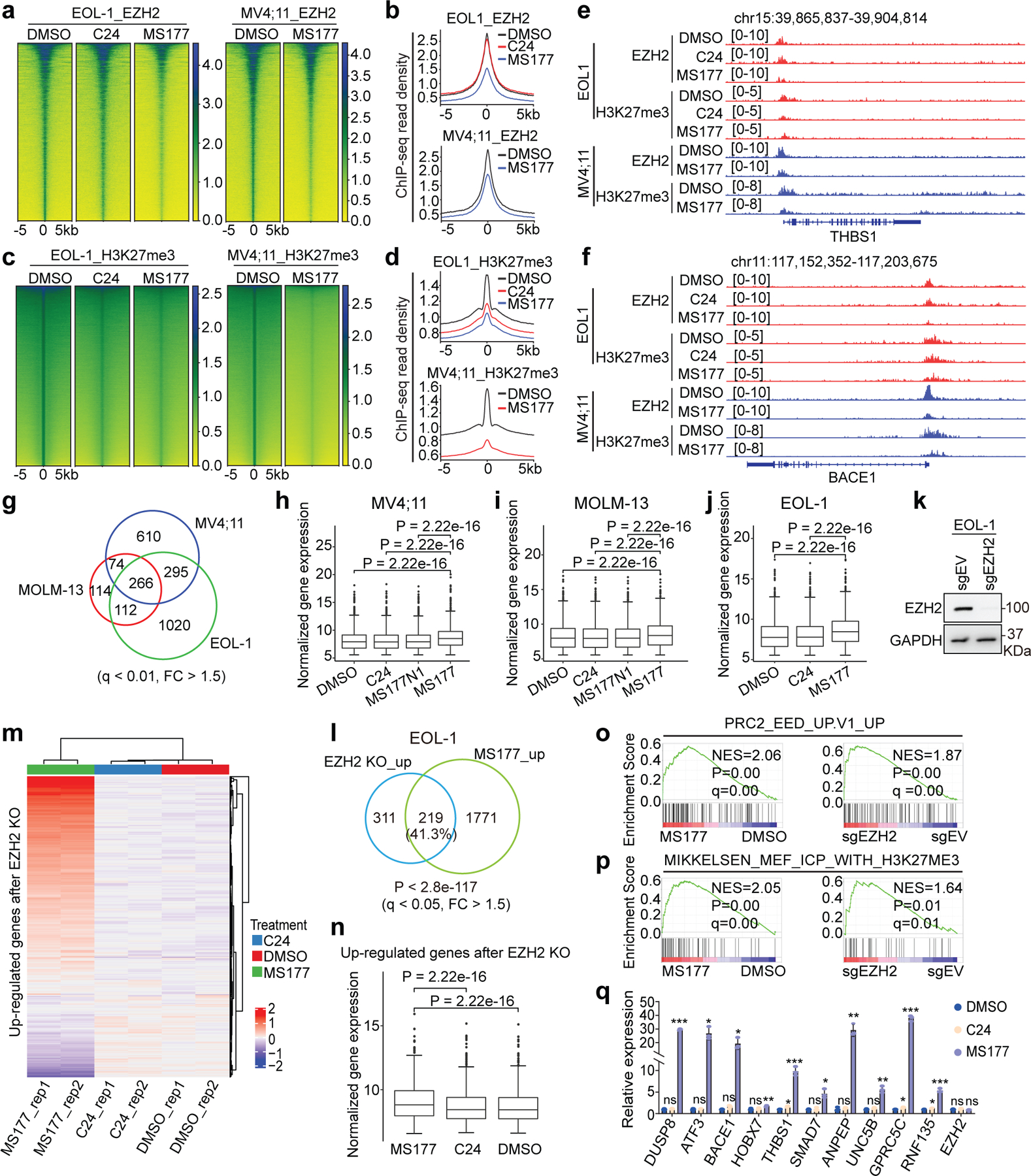

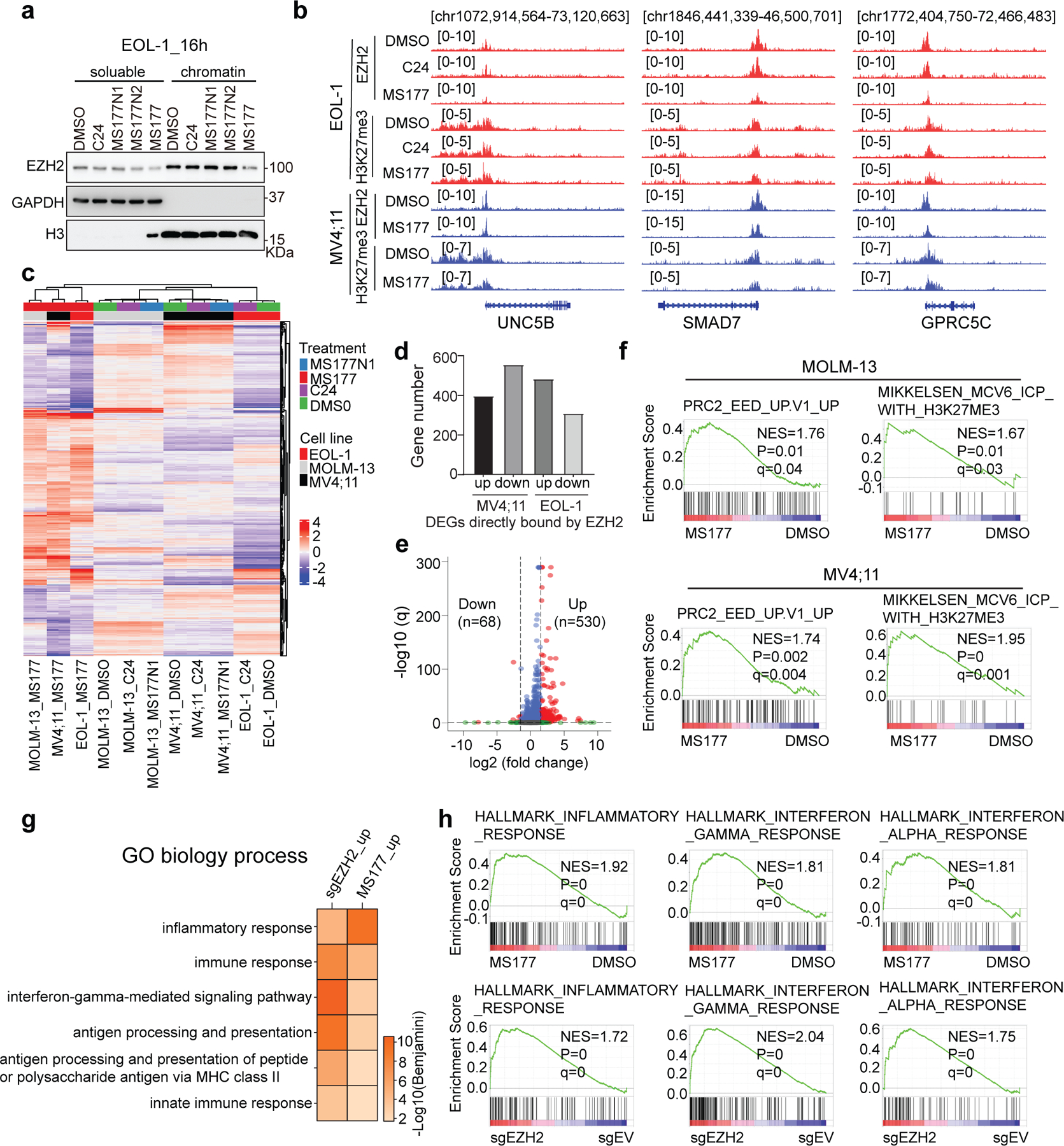

MS177 efficiently suppresses EZH2:PRC2 functions in cells.

MS177 exhibited comparable depletion effect on both nucleoplasmic and chromatin-bound EZH2 (Extended Data Fig. 6a). ChIP-seq for EZH2 and H3K27me3 after compound treatment of leukaemia cells (Supplementary Table 4) revealed that, relative to mock, MS177, but not C24, decreased overall levels of chromatin-bound EZH2, whereas both suppressed global H3K27me3 (Fig. 5a–d), as exemplified by what was observed at canonical EZH2:PRC2 targets (Fig. 5e–f and Extended Data Fig. 6b). Thus, compared to C24, MS177 reduces chromatin-bound EZH2, highlighting a potential advantage of the EZH2-targeting PROTAC degrader over EZH2’s enzymatic inhibitor.

Fig. 5|. MS177 exhibits the on-target inhibition effect on EZH2:PRC2.

a-d Heatmaps (a,c) and averaged plotting (b,d) of EZH2 (a-b) and H3K27me3 (c-d) ChIP-seq signal intensities (normalized against spike-in control and sequencing depth) around peak centers in EOL-1 and MV4;11 cells, treated for 16 and 24 hours, respectively, with 0.5 µM of DMSO, C24 or MS177.

e-f, IGV view of EZH2 and H3K27me3 at THBS1 (e) and BACE1 (f) in the indicated cells.

g, Venn diagram using DEGs de-repressed after MS177 versus DMSO treatment, as identified by RNA-seq in the three MLL-r leukaemia lines. Threshold of DEG is set as q < 0.01, FC > 1.5 and mean tag counts > 10.

h-j, Overall expression of transcripts upregulated after MS177 versus DMSO treatment across the indicated samples of MV4;11 (h), MOLM-13 (i) and EOL-1 (j) cells. Y-axis represents Log10-converted RNA-seq signals. Paired two-sided t-test was used.

k, Immunoblotting showing EZH2 KO.

l, Venn diagram using DEGs upregulated in EOL-1 cells post-treatment of MS177 and those after EZH2 KO, relative to mock. DEG is defined as above.

m-n, Heatmap (m) and boxplot (n) showing expression of the EZH2-repressed transcripts in EOL-1 cells, treated with 0.5 µM of DMSO, C24 or MS177 for 16 hours (n = 2). EZH2-repressed genes are defined in l after EZH2 KO versus mock. Paired two-sided t-test was used. Rep, replicate.

o-p, GSEA revealing MS177 treatment (left) and EZH2 KO (right) in EOL-1 cells positively correlated with upregulation of the PRC2:EED-repressed (o) or H3K27me3-bound (p) genes.

q, RT-qPCR of the EZH2-repressed targets in EOL-1 cells post-treatment with 0.5 µM of DMSO, C24 or MS177 for 16 hours. Y-axis shows signals after normalization to GAPDH and to DMSO-treated (n = 3; mean ± SD; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

For h-j and n, the boundaries of boxplots indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, the center line indicates the median, and the whiskers (dashed) indicate 1.5× the interquartile range. *, **, and *** denote P < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.005, respectively. NS denotes not significant. Numerical source data, statistics, exact P values and unprocessed blots are available as source data.

We then conducted RNA-seq post-treatment of three independent MLL-r leukaemia models with MS177, C24 or MS177N1. Despite background difference, leukaemia cells treated with MS177 displayed a greater similarity among themselves than those treated with C24 or MS177N1 (Extended Data Fig. 6c), and DEGs caused by MS177 treatment overlapped significantly among independent leukaemia models (Fig. 5g). Notably, robust transcriptomic changes were observed post-treatment with MS177, and not C24 or MS177N1, relative to mock (Supplementary Tables 5–6). A significant portion of DEGs were directly bound by EZH2 (Extended Data Fig. 6d). Moreover, those MS177-derepressed DEGs showed little/mild de-repression after comparable treatment of C24 or MS177N1 (Fig. 5h–j).

We next aimed to further assess MS177’s effect on canonical EZH2:PRC2 targets. RNA-seq profiling revealed a significant overlap between DEGs caused by CRISPR/Cas9-induced EZH2 KO and those by treatment with MS177, but not C24, in EOL-1 cells (Fig. 5k–l; Extended Data Fig. 6e; Supplementary Table 7). Consistently, MS177 but not C24 exhibited de-repression effect on overall expression of the EZH2-repressed transcripts (Fig. 5m–n). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) and GO analyses revealed MS177 treatment or EZH2 KO significantly associated with activation of H3K27me3/PRC2 targets and inflammatory or immune response (Fig. 5o–p, and Extended Data Fig. 6f–h). EZH2 is known to regulate immunity54, 55. RT-qPCR confirmed PRC2 target re-activation post-treatment with MS177, but not C24 (Fig. 5q).

Collectively, MS177 is superior to EZH2’s enzymatic inhibitors in inducing EZH2:PRC2 loss and reactivating the PRC2/H3K27me3-targeted genes related to anti-proliferation and immunity54, 55.

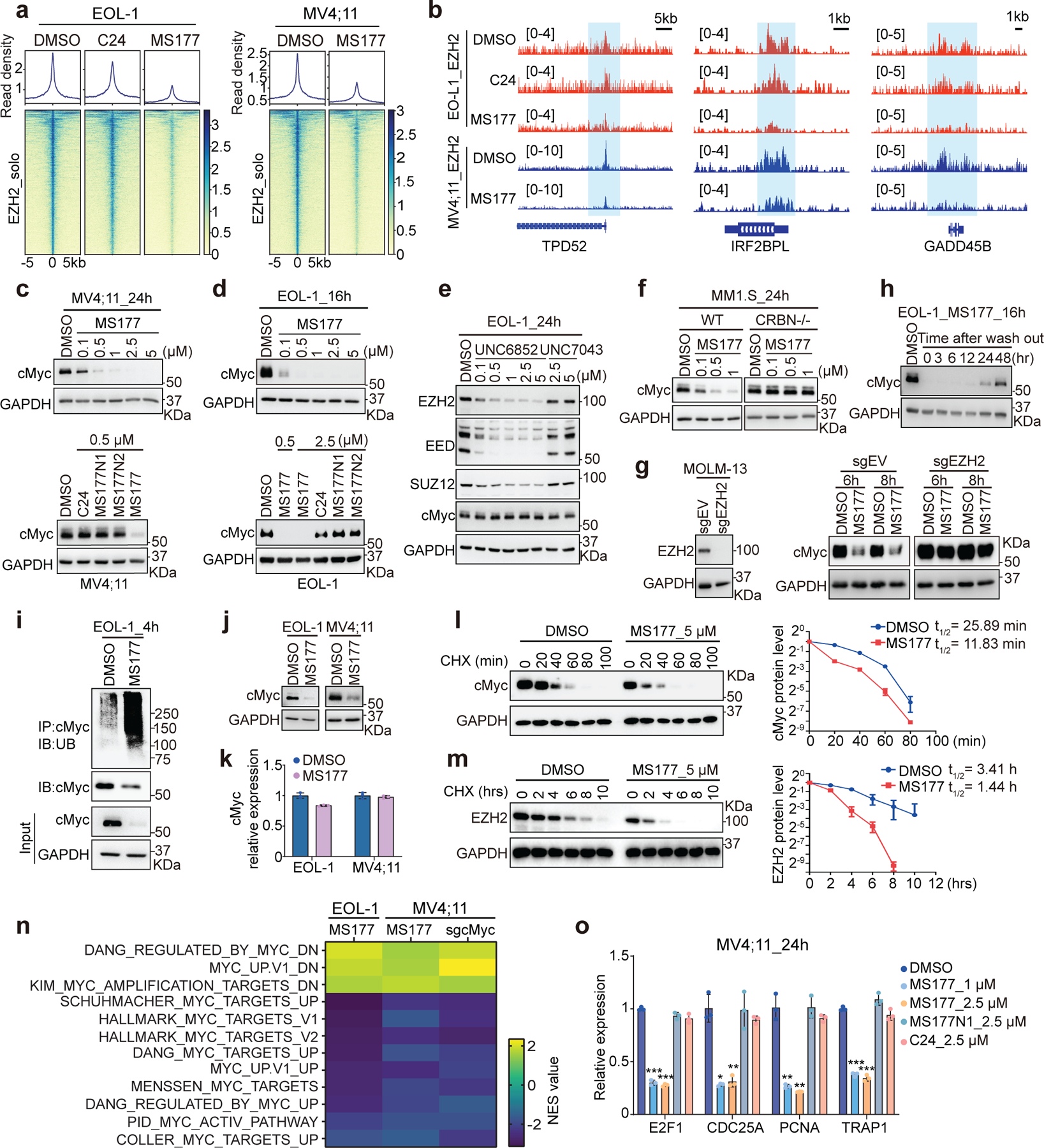

MS177 also efficiently induces Myc degradation in cancer.

MS177-mediated EZH2 degradation occurred at both canonical EZH2:PRC2 sites (Extended Data Fig. 7a) and noncanonical EZH2-”solo”-binding sites such as TPD52, IRF2BPL and GADD45B (Fig. 6a–b). DEGs downregulated after MS177 treatment were found more enriched for the genes with EZH2-’solo’-binding than EZH2:PRC2 targets (Extended Data Fig. 7b). Thus, we reasoned that MS177 may also degrade cMyc, EZH2’s noncanonical partner at EZH2-’solo’ sites. Indeed, treatment with MS177, but not C24 or MS177N1/2, significantly decreased cellular cMyc (Fig. 6c–d and Extended Data Fig. 7c–d). In agreement with PRC2-independent binding of EZH2 to cMyc, the EED degrader UNC6852 did not affect the cMyc level while efficiently degrading EED and associated PRC2 (Fig. 6e). MS177-induced cMyc depletion was significantly suppressed post-depletion of CRBN (Fig. 6f) or EZH2 (Fig. 6g). The E3 ligases FBW7, UBR5, SKP2 and HUWE1 are known to mediate cMyc degradation. However, depletion of neither of these E3 ligases interfered with the MS177-mediated cMyc degradation (Extended Data Fig. 7e–g). Post-washout of MS177, cMyc depletion was found recovered (Fig. 6h). Also, cMyc protein was observed ubiquitinated and then depleted post-treatment with MS177, while its transcript level was unaltered (Fig. 6i–k), supporting a proteasome-mediated degradation mechanism. The cMyc protein is labile56, 57. In untreated cells, half-lives of cMyc and EZH2 proteins were measured to be ~26 minutes and ~3.4 hours respectively, which decreased similarly by ~2.2–2.4-folds upon MS177 treatment (Fig. 6l–m). Given a striking effect by MS177 on cMyc degradation, we further tested if MS177 degrades N-Myc, a cMyc-related onco-TF, by using Kelly cells, a neuroblastoma line harboring N-Myc amplification. Indeed, MS177, but not C24 or MS177N1/2, concentration-dependently degraded both EZH2:PRC2 and N-Myc via ubiquitination, inhibiting colony formation of Kelly cells (Extended Data Fig. 7h–k). Notably, cMyc-activated gene-expression programs are among the most down-regulated ones post-treatment of MS177 relative to mock in independent MLL-r leukaemia cells, while C24 did not have such effect (Fig. 6n and Extended Data Fig. 7l–m). RT-qPCR verified the down-regulation effect by MS177, but not C24 or MS177N1, on the cMyc-activated targets (Fig. 6o).

Fig. 6|. MS177 represses the cMyc-related oncogenic node.

a, Heatmaps showing EZH2 ChIP-seq signals around the centers of EZH2-’solo’-binding peaks in EOL-1 and MV4;11 cells, treated for 16 and 24 hours, respectively, with 0.5 µM of DMSO, C24 or MS177.

b, EZH2 binding at TPD52, IRF2BPL and GADD45B in the indicated cells.

c-d, cMyc immunoblotting using MV4;11 (c) and EOL-1 (d) cells after the indicated compound treatment.

e, Immunoblotting for the indicated protein in EOL-1 cells, treated with EED-targeting PROTAC (UNC6852) or its non-PROTAC analog (UNC7043) for 24 hours.

f, cMyc immunoblotting using wildtype or CRBN-deficient (CRBN-/-) MM1.S cells, treated with MS177 versus DMSO for 24 hours.

g, Left: immunoblotting showing EZH2 KO. Right: cMyc immunoblotting using EZH2-depleted or mock-treated MOLM-13 cells, treated with 5 µM of MS177 for 6 or 8 hours, versus DMSO.

h, cMyc immunoblotting in EOL-1 cells first treated with 0.5 µM of MS177 for 16 hours and then subjected to MS177 washout for the indicated time, compared to DMSO-treated mock.

i, cMyc ubiquitination immunoblotting using EOL-1 cells treated with 5 µM of MS177 versus DMSO for 4 hours.

j-k, Immunoblotting (j) and RT-PCR for cMyc (k; n = 3; mean ± SD) in EOL-1 and MV4;11 cells, treated with 5 µM of MS177 versus DMSO for 4 hours.

l-m, Immunoblotting (left) and degradation curve (right) of cMyc (l) or EZH2 (m) in DMSO- or MS177-treated EOL-1 cells in the presence of cycloheximide (CHX; n=2 independent experiments; mean ± SD).

n, Summary of GSEA results showing correlation of the indicated MYC-related genesets with MS177 treatment or cMyc KO (sgcMyc), relative to mock. Green and red in heatmap indicate positive and negative correlations, respectively, NES, normalized enrichment score.

o, RT-qPCR for cMyc-upregulated targets in MV4;11 cells after the indicated compound treatment for 24 hours. Y-axis shows signals after normalization to GAPDH and to DMSO-treated cells (n = 3; mean ± SD; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

*, **, and *** denote P < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.005, respectively. NS denotes not significant. Numerical source data, statistics, exact P values and unprocessed blots are available as source data.

Overall, compared to EZH2’s enzymatic inhibitors, MS177 uniquely induces Myc ubiquitination and degradation, suppressing Myc-enforced oncogenic circuitry.

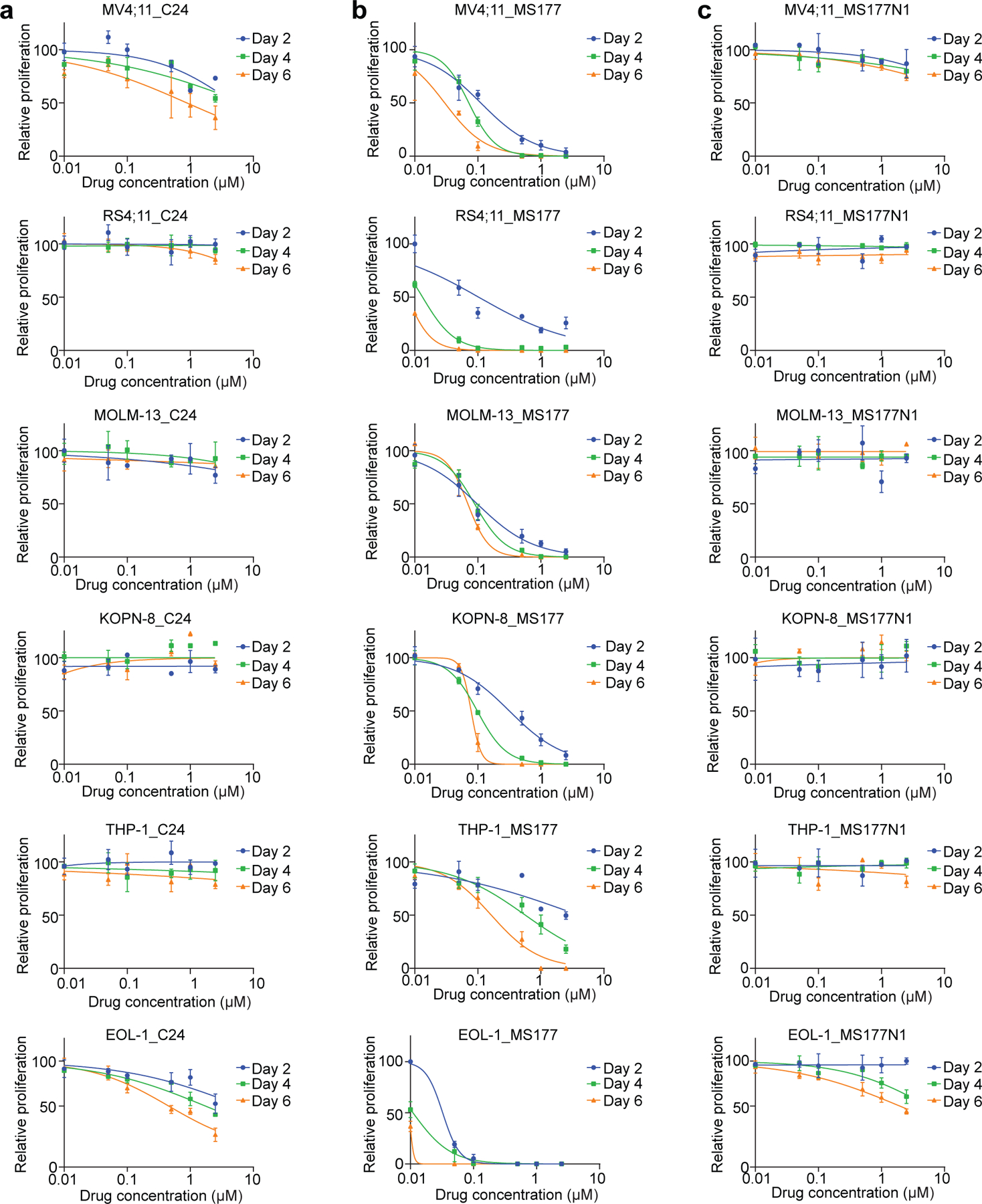

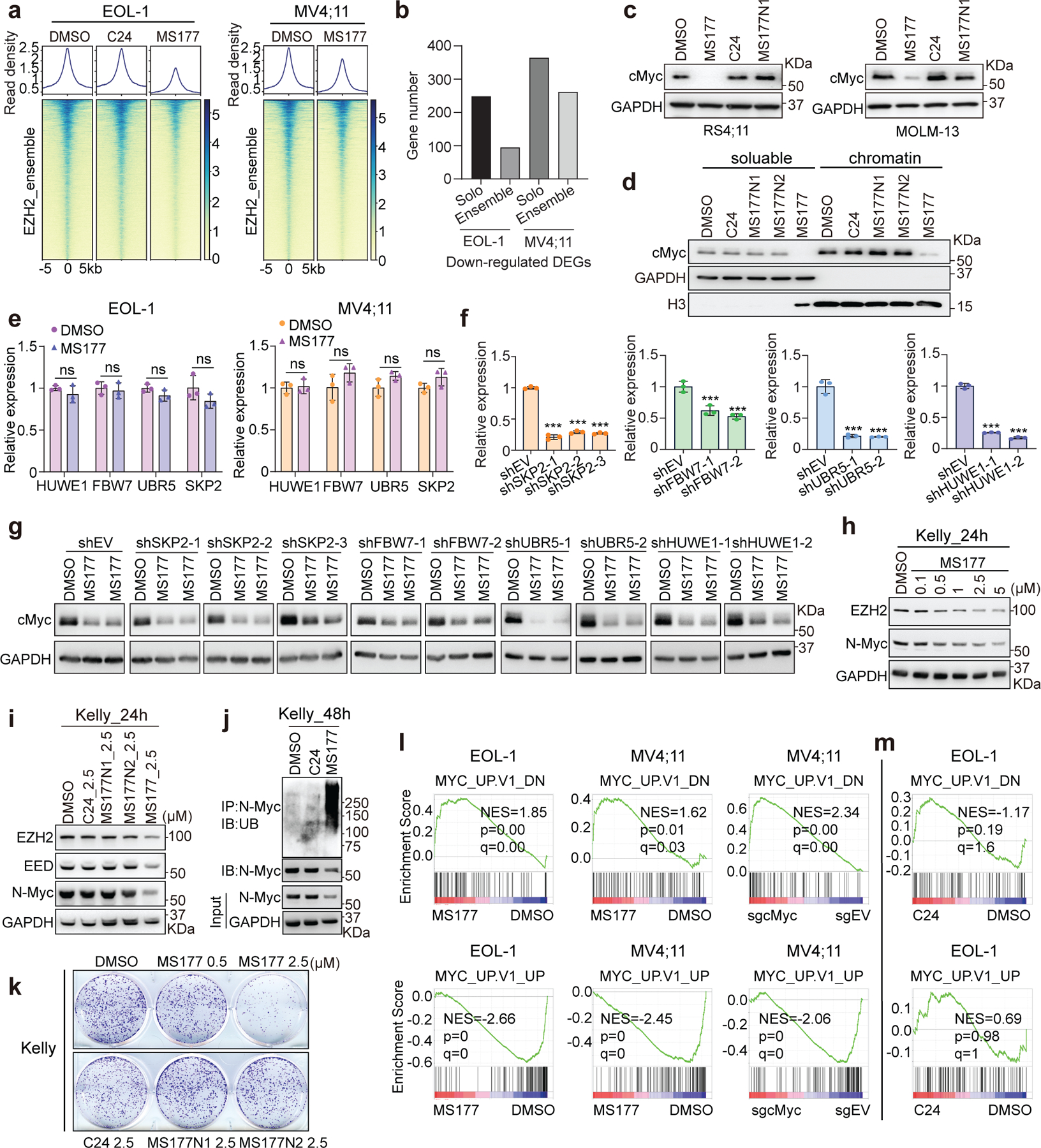

MS177 is superior to EZH2 inhibitors in killing tumor cells.

Next, we evaluated MS177’s cancer-killing effect. In a panel of MLL-r leukaemia lines and AML patient samples (Supplementary table 8), MS177 displayed potent, fast-acting and consistent anti-proliferation effect, whereas C24 and MS177N1 generally had no effect on EZH2 or cMyc degradation and had little/mild effect in tumor cell killing (Extended Data Fig. 4a–c; Fig. 6d; Extended Data Fig. 8a). Strikingly, half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) values of MS177 represent two-to-three orders of magnitude increase in potency, compared to those of C24 and MS177N1/2 (Supplementary table 9; Fig. 7a–c; Extended Data Fig. 8b–c). Additionally, a much weaker effect of MS177 was seen with samples from patients in remission (which were mainly normal cells), compared to paired AML samples (Fig. 7d–e). Degradation of PRC2 and cMyc, as well as de-repression of EZH2:PRC2 target genes, was observed in patient samples post-treatment with MS177, but not C24, relative to DMSO (Fig. 7f–g and Extended Data Fig. 8d–e). Furthermore, MS177 was much more potent in inhibiting leukaemia growth than a panel of the EZH2 catalytic inhibitors and EED degrader, although all of them effectively abolished H3K27me3 (Fig. 7h–j). Notably, MS177 had little inhibitory effect on colony formation by primary hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells or on growth of K562 cells (Fig. 7k and Extended Data Fig. 8f–g), suggesting a lack of general cytotoxicity. IKZF1 and IKZF3 are known neo-substrates of CRBN58, the E3 ligase MS177 recruits. Although MS177, MS177N2 and pomalidomide all induced IKZF1/3 degradation, only MS177 markedly inhibited the growth of MLL-r leukaemia cells (Fig. 7l–m and Extended Data Fig. 8h–i), suggesting that MS177-induced tumor-killing effect does not stem from degradation of CRBN’s neo-substrates. Furthermore, only MS177 treatment, but not C24 or MS177N1, dramatically decreased colony-forming capabilities, slowed cell cycle progression, and induced leukaemia cell apoptosis (Fig. 7n–q and Extended Data Fig. 8j–l). Meanwhile, EZH2 depletion greatly diminished the MS177-mediated apoptotic and anti-proliferation effect (Fig. 7r; Extended Data Fig. 8m), again supporting that MS177’s antitumor effect is EZH2-binding-dependent. Together, MS177’s cancer-killing effects are much more potent and fast-acting than EZH2’s enzymatic inhibitors.

Fig. 7|. MS177 efficiently induces leukaemia cell growth inhibition, apoptosis, and cell cycle progression arrest.

a, EC50 values of MS177 in the indicated AML cell lines (left) and patient samples (right) after a 4-day treatment (n=3).

b, MOLM-13 cell growth after a 48-hour treatment with different concentration of C24, MS177, MS177N1 or MS177N2, relative to DMSO. Y-axis shows mean ± SD after normalization to DMSO-treated (n = 3).

c-e, Effect of a 48-hour treatment with various concentration of MS177, relative to DMSO, on proliferation of four primary AML samples (c) or paired cells from de-identified patients, either in remission or with diagnosed AML (d-e). Y-axis shows mean ± SD after normalization to mock (n = 3) .

f-g, Immunoblotting for the indicated protein in two primary AML samples, treated with DMSO, MS177 or C24 for 24 (f) and 36 (g) hours.

h-j, H3K27me3 immunoblotting (h) and growth (i-j) of EOL-1 cells, treated with the indicated concentration of various EZH2 catalytic inhibitors (h-i), MS177 (i) or UNC6852 (j) for 48 hours (n=3; mean ± SD; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

k, Colony formation by murine hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) in the presence of DMSO or MS177 (n=2; mean ± SD).

l-m, Immunoblotting of the indicated protein (l) and growth (m) of MV4;11 cells, treated with 2.5 µM of DMSO, MS177, MS177N2, C24, pomalidomide (Pom), or C24 plus Pom. Y-axis in k shows mean ± SD after normalization to DMSO-treated (n = 3; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

n-o, Representative image (n) and quantification of colony formation (o; mean ± SD of two experiments) using MV4;11 cells treated with the indicated compound.

p, MOLM-13 cell cycle analysis after a 24-hour treatment with the indicated compound.

q-r, Immunoblotting for various apoptotic markers post-treatment of AML patient cells (q), or the mock-treated (sgEV) or EZH2-depleted (sgEZH2) MOLM-13 cells (r), with the indicated compound for 24 hours.

*, **, and *** denote the P value of < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.005, respectively. NS denotes not significant. Numerical source data, statistics, exact P values and unprocessed blots are available as source data.

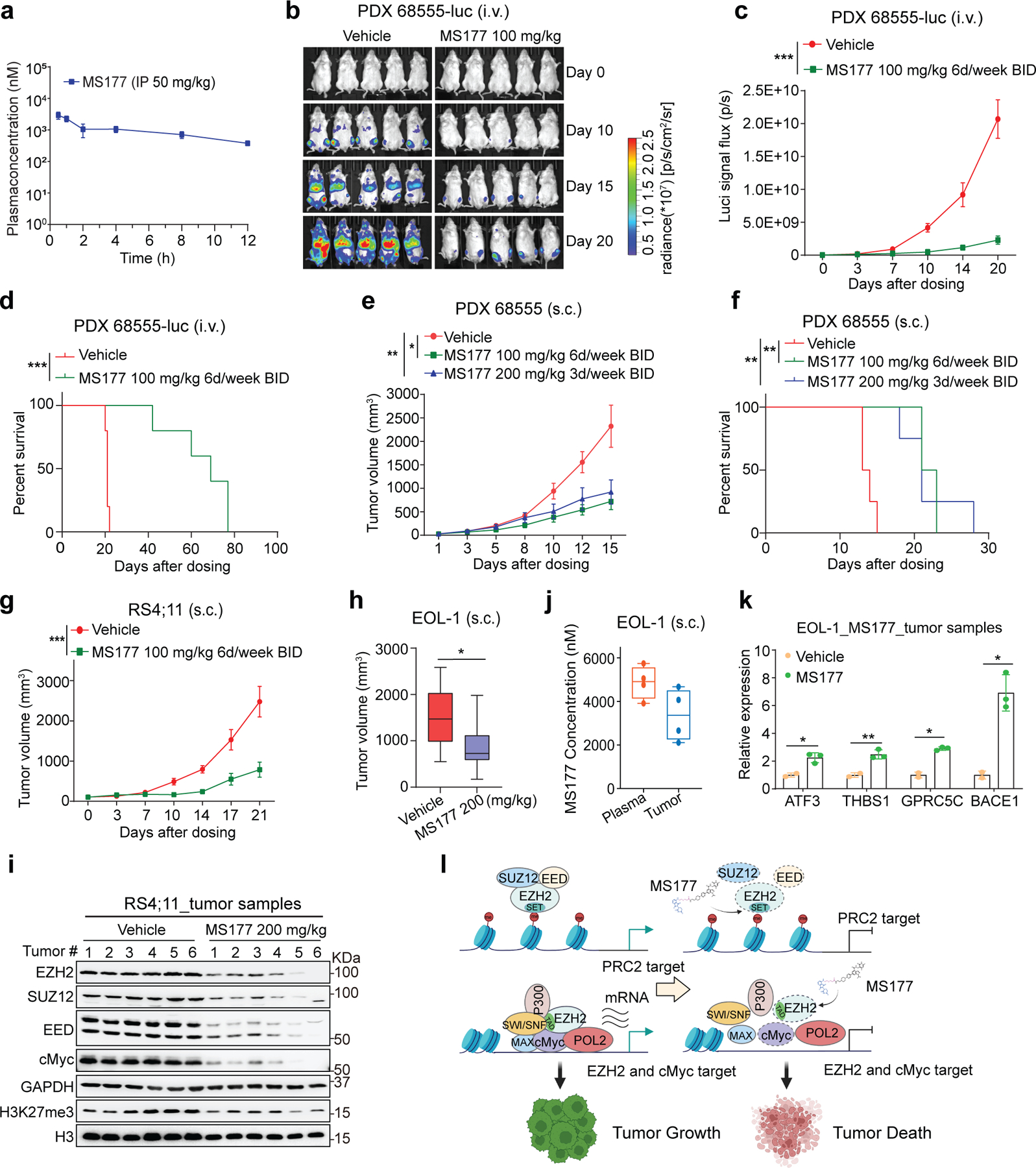

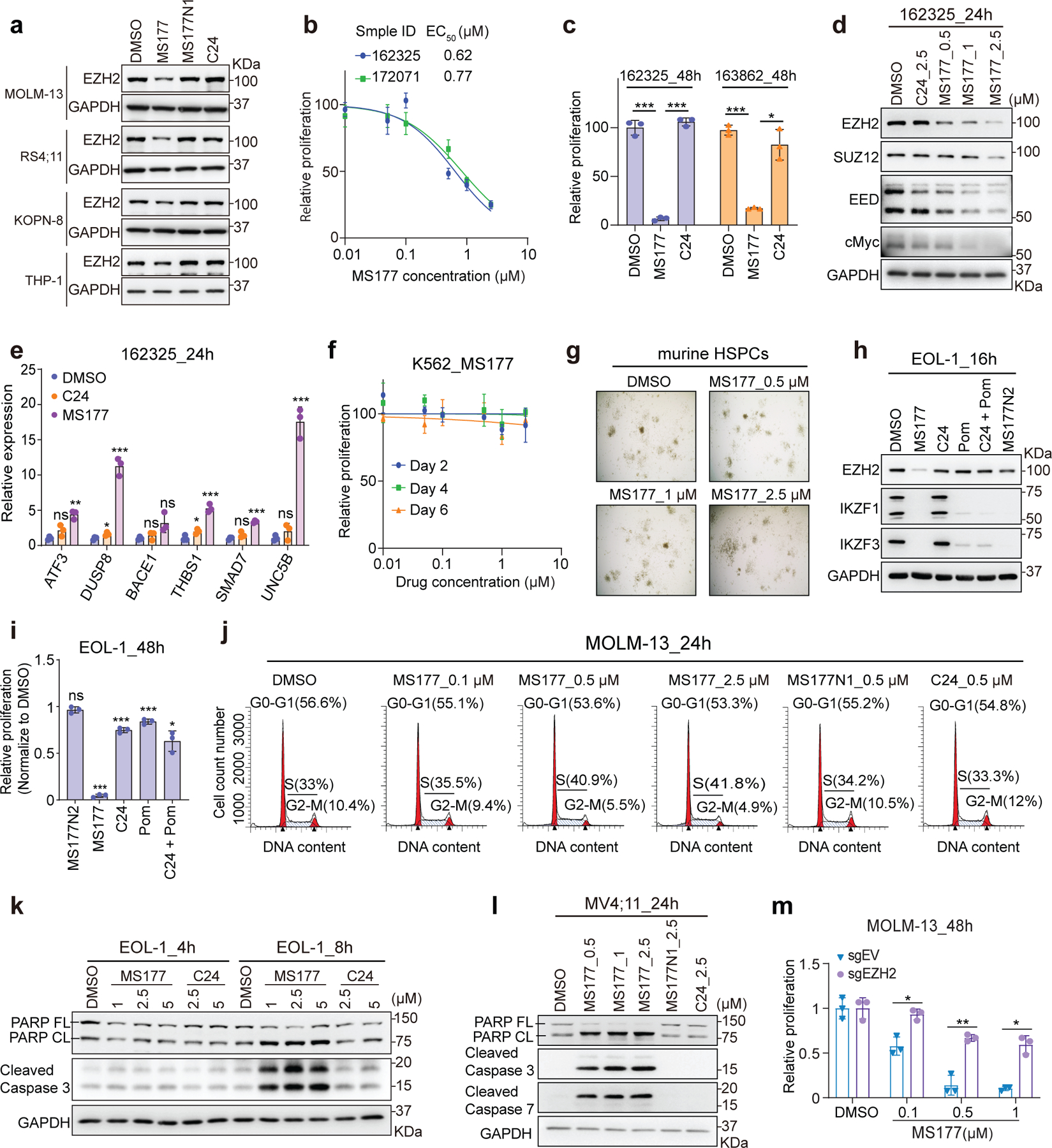

MS177 represses tumor growth in vivo.

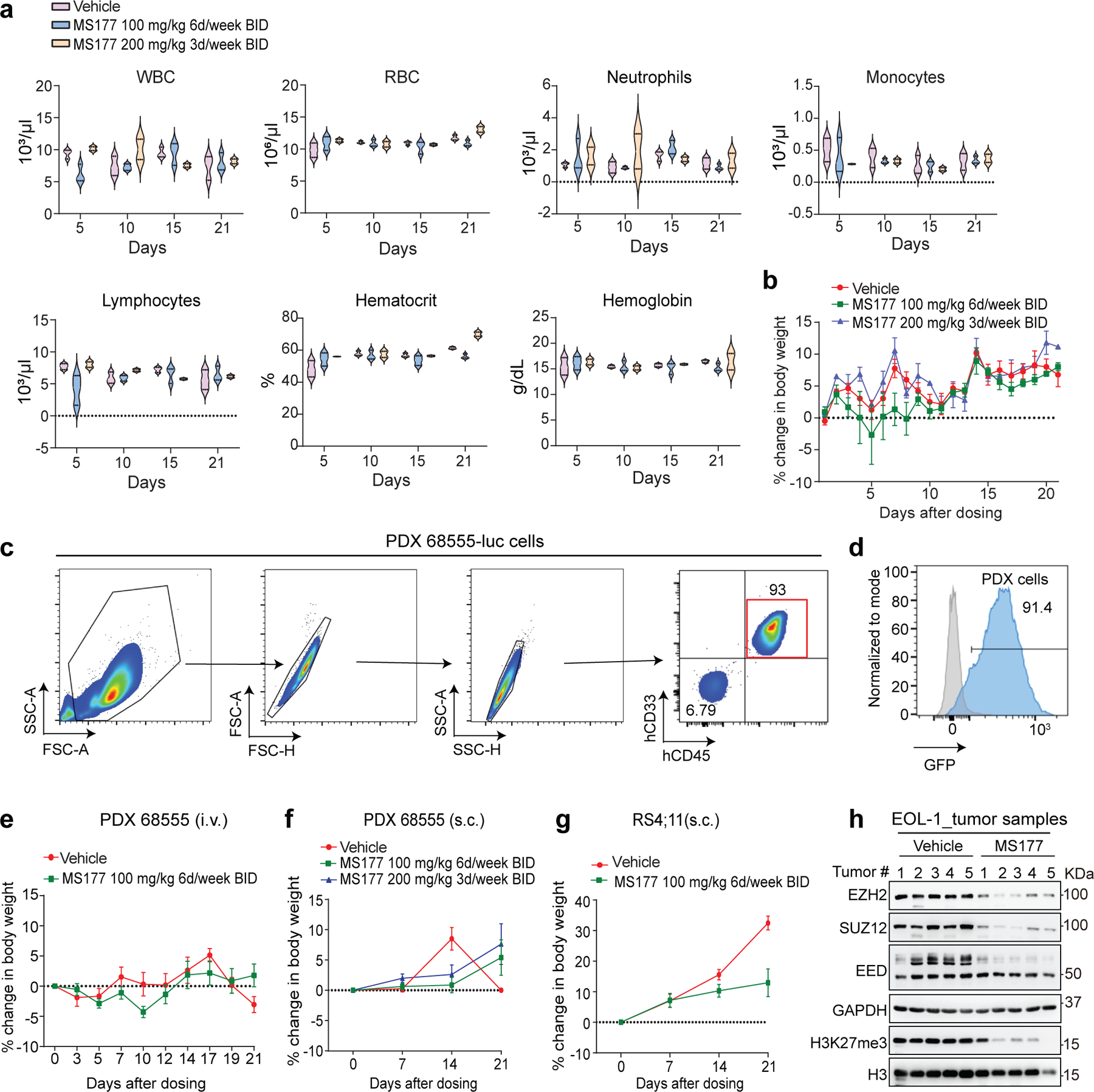

Next, we characterized MS177’s pharmacokinetic properties in mice and found intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of MS177 at a dose of 50 mg/kg achieved intra-plasma concentration comparable to the EC50 value measured by cancer cell killing in vitro (Fig. 8a; Supplementary table 10). Further, two doses of MS177 (100 mg/kg i.p. twice a day [BID] for 6 days per week; and 200 mg/kg i.p. BID 3 days per week) were well tolerated and lacked apparent toxicity in mice (Extended Data Fig. 9a–b). Next, we assessed MS177’s antitumor effect first by using a PDX animal model of MLL-r AML (Extended Data Fig. 9c–d). Relative to vehicle treatment, the above two regimens of MS177 dosing significantly inhibited AML growth in PDX models, established via dissemination or subcutaneously, and prolonged survival (Fig. 8b–f; Extended Data Fig. 9e–f). Similar tumor-suppressing effects by MS177 were observed in additional subcutaneously xenografted MLL-r leukaemia models using RS4;11 or EOL-1 cells (Fig. 8g–h; Extended Data Fig. 9g). During dosing, we also measured the intra-tumor and intra-plasma MS177 concentration to be ~3–5 µM and observed the expected effect by MS177 on degradation of EZH2:PRC2 and cMyc and on modulation of EZH2 target genes in tumor xenografts (Fig. 8i–k and Extended Data Fig. 9h). Together, the EZH2-targeting PROTAC MS177 is an effective therapeutic agent without significant general toxicity.

Fig. 8|. MS177 represses AML growth in vivo.

a, Intra-plasma concentrations of MS177 over a 12-hour period after a single indicated intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection into male Swiss Albino mice (n = 6; mean ± SEM from three mice per time point).

b-d, Bioluminescent imaging (b) and signal levels (c) and Kaplan-Meier curve (d) of NSG-SGM3 mice transplanted intravenously (i.v.) with the luciferase (luc)-labeled MLL-r AML PDX cells, which were then treated with vehicle or the indicated MS177 dosing (n = 5 mice per group; mean ± SD). Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA (c) or log-rank (Mantel-cox, d) test.

e-f, Averaged tumor volume (e, g-h) and Kaplan-Meier curve (f) of mice subcutaneously (s.c.) transplanted with MLL-r AML PDX (e-f), RS4;11 (g) or EOL-1 cells (h), which were then treated with vehicle or the indicated MS177 dosing (n = 5 per group; mean ± SD). Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA (e), log-rank test (f) or unpaired two tailed student’s t-test (h; boxplot shows mean and interquartile range).

i, Immunoblotting for the indicated protein using the collected RS4;11 s.c. xenografted tumors, freshly isolated from NSG mice that were treated with vehicle or the indicated MS177 dosing for 5 days.

j, Intra-plasma and intra-tumor concentration of MS177 in NSG mice in h, treated with vehicle or the indicated MS177 dosing (n = 4 per group). Dots represent individual tumors.

k, RT-qPCR for the EZH2-repressed target in the EOL-1 s.c. xenografted tumors as isolated in i. Y-axis shows mean ± SD after normalization to GAPDH and then to vehicle-treated (n = 3; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

l, A model that, in MLL-r leukaemias, EZH2 forms canonical (EZH2:PRC2) and noncanonical (EZH2:cMyc:coactivators) interactions for promoting target gene repression and activation, respectively, both of which mediate oncogenesis (top). These oncogenic actions of EZH2 can be suppressed by the EZH2 PROTAC degrader, MS177 (bottom).

*, **, and *** denote the P value of < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.005, respectively. NS denotes not significant. Numerical source data, statistics, exact P values and unprocessed blots are available as source data.

Discussion

Extensive evidence points to tumor-promoting roles of EZH2 in human cancer. Patients with higher EZH2 expression often displayed poorer clinical outcomes3–6, 59. Canonically, EZH2 serves as the enzymatic subunit of PRC2 for catalyzing H3K27me3 and repressing gene expression. Increasing evidence shows that EZH2 also relies on methyltransferase-independent mechanisms to modulate gene expression and oncogenesis10, 20, 23–27, exemplified by its gene-activating roles at NF-kB23 and AR10 targets in solid cancers. Here, we unveiled that, in MLL-r leukaemias, EZH2 uses a hidden TAD to form interaction with cMyc and p300 for activating AML-related transcripts. Direct EZH2:cMyc interaction and EZH2-TAD’s involvement for regulating EZH2’s noncanonical targets and promoting oncogenesis have not been reported. We speculate that such unconventional functions of EZH2 might be due to EZH2 overexpression in aggressive cancers and a lack of concurrently increased levels of other PRC2 subunits, thereby shifting PRC2 component stoichiometry, which may be further enhanced by cMyc upregulation existing in cancer. Cellular contexts such as kinase signaling also regulate EZH2 interaction with PRC2 subunits20.

Understanding of EZH2’s multifaceted actions is important for developing more effective therapies for the treatment of EZH2-dependent cancers. Small-molecule inhibitors of EZH2 effectively inhibit its methyltransferase activity, but cannot suppress its methyltransferase-independent functions. Consequently, EZH2’s catalytic inhibitors showed the rather slow and often incomplete tumor-suppressive effect. We employed the PROTAC technology and discovered a highly effective EZH2-targeting degrader, MS177, in addition to two structurally similar analogs, MS177N1 (which binds EZH2 but not CRBN) and MS177N2 (which binds CRBN but not EZH2), as controls. We comprehensively characterized their effects in vitro and in vivo. First, MS177 potently degrades EZH2 and EZH2-associated partners (PRC2 and cMyc); and MS177 is highly selective for EZH2 over approximately 100 proteins that covered methyltransferases and common drug targets. Second, in a range of cancer lines and patient-derived models, MS177 possesses the superior anti-tumor effect to EZH2’s catalytic inhibitors and MS177’s non-degrader analogs. Third, integrated genomic profiling showed that MS177 effectively depletes chromatin-bound EZH2 and displays a much more profound effect on re-activating EZH2:PRC2 targets, compared to EZH2’s enzymatic inhibitors. Fourth, MS177 not only displays excellent pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) relationships and is well tolerated in vivo, but also importantly suppresses the in vivo oncogenesis of multiple tumor cell line xenografted and PDX models and enhances overall survival. MS177 thus represents a promising therapeutic agent for further development. Fifth, compared to EZH2’s catalytic inhibitors and EED-targeting PROTAC, MS177 uniquely suppresses Myc-related oncogenic programs in cancer. Myc-suppressing effect is due to a direct interaction of EZH2-TAD and cMyc. As the EZH2-TAD:cMyc interaction is PRC2-independent and related to transactivation, this noncanonical function of EZH2 is generally unaffected by EZH2’s catalytic inhibitors or EED degrader. Together, our findings highlight advantages of EZH2-targeting PROTAC over its catalytic inhibitors in therapeutics. An effective EZH2 PROTAC degrader simultaneously targets multi-faceted oncogenic functions of EZH2, leading to more profound, consistent and fast-acting antitumor effects, compared to EZH2’s catalytic inhibitors (see a model in Fig. 8l).

The mechanisms underlying cMyc’s recruitment to EZH2-’solo’-binding sites are complex. Although canonical cMyc motifs were enriched at EZH2-’solo’-binding peaks, studies demonstrated cMyc-binding sites in cells often lacking such motifs. We uncovered direct interaction of EZH2-TAD with cMyc-CD. cMyc can interact, either directly or indirectly, with basal transcription machinery, activators/cofactors and transcriptional elongation factors36, 41–43. In agreement, EZH2-TAD directly binds (co)activators such as p300 and cMyc. Conceivably, these biochemical interactions collectively contribute to co-targeting of cMyc and EZH2 to EZH2-’solo’-binding sites where (co)activators, POL II and gene-activation-related markers coexist. A ‘coalition model’ was proposed, suggesting multiple cooperating interactions exist among cMyc and many partners during oncogenesis36. TADs of (co)activators are often unstructured and intrinsically disorganized protein region can induce phase separation as proposed for cMyc36, 39. We speculate that TAD and/or unstructured protein region of EZH2, cMyc and (co)activators establish phase-separated condensates for mediating gene activation. It is also worth to stress the multifaceted nature of cMyc’s biological functions, besides the most-studied transcriptional regulation36, 39. In agreement, our RNA-seq results suggested that cMyc does not always display a potent transcriptional activation role at cMyc:EZH2-’solo’-cobound genes, which merits further investigation. Here, an exciting finding is that EZH2-targeting PROTAC effectively degrades Myc, thus adding to rather limited arsenals targeting Myc36.

We carefully assessed the MOA of MS177. Depletion of cellular CRBN or EZH2, to which MS177 binds, abolished MS177’s effects on EZH2 and cMyc degradation, as well as apoptosis induction and anti-proliferation, supporting a CRBN-dependent and EZH2-binding-dependent MOA. MS177 degrades EZH2 at both canonical EZH2:PRC2 and noncanonical EZH2-’solo’-binding sites, with the effect being mildly more striking at the latter. Also, MS177’s cMyc-degrading effect appears more apparent. Such differential degradation effects by MS177 could potentially be caused by several factors. First, PROTAC access to targets (the SET domain of EZH2 as to MS177) is context-dependent. Conceivably, EZH2:PRC2-bound chromatin is in a more closed conformation, compared to EZH2-’solo’-bound regions, which may affect compound access. Second, protein or complex stability varies drastically. cMyc protein, with a half-life of ~30 minutes in cells, is much more labile than EZH2, partly explaining that cMyc appears to be degraded faster following MS177 treatment. In fact, MS177 had same effects on decreasing half-lives of EZH2 and cMyc proteins. Notably, cMyc proteins are highly mobile in cells60 and cellular pool of cMyc can be efficiently ‘drained’ through MS177-mediated degradation of EZH2:cMyc. Overall, MS177, which effectively degrades both EZH2 and cMyc, is a promising therapeutic agent for treating EZH2-dependent cancers.

METHOD

All animal experiments are approved by and performed in accord with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at UNC. De-identified human tumor samples and informed consent were obtained from the patients by the UNC Tissue Procurement Facility (TPF) under the protocol (UNC-LCCC-9001). This current study did not involve recruitment of patients or usage of clinical data. No demographic identifiers were obtained for any of the patients, and their gene mutational information was provided in the Supplementary Table 8. Cryopreserved specimen of an MLL-AF9+ AML Patient-derived Xenograft (PDX) model was obtained from Public Repository of Xenografts (DFAM-68555, PRoXe; www.proxe.org).

Cells and Tissue Culture

Cell lines used in the study included 293T (American Tissue Culture Collection [ATCC], CRL-3216), Hela (ATCC, CCL-2), MV4;11 (ATCC, CRL-9591), RS4;11 (ATCC, CRL-1873), MOLM-13 (Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen [DSMZ], ACC554), KOPN-8 (DSMZ, ACC552), EOL-1 (DSMZ, ACC386), K562 (ATCC, CRL-243), and THP-1 (ATCC, TIB-202). An MM1.S-derivative line with CRBN knockout (KO; CRBN-/-) was provided by Drs. J Brander and W Kaelin (Dana Farber Cancer Institute). Luciferase (luc)-labeled cells were generated by infection with MSCV-luciferase-IRES-neo retrovirus and subsequent selection. Luciferase expression was validated with Luciferase Assay System (Promega, #E1500). MV4;11 cells stably expressed with doxycycline (Dox)-inducible Cas9 (iCas9)61 were a gift of Drs. X Shi and H Wen (Van Andel Institute). Identity of cell lines was ensured by UNC’s Tissue Culture Facility with genetic signature analyses and examination of mycoplasma contamination performed using commercial detection kits (Lonza, #LT27–286).

Methods for cell transfection, generation of stable expression cell lines, assays for cell cycle progression, apoptosis and colony formation, as well as hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell (HSPC) purification and related colony formation unit (CFU) assay, were provided in Supplementary Note file.

Plasmid Construction

EZH2 or cMyc was fused with Flag or HA tag and cloned into the pcDNA-3.1 (Invitrogen) and pCDH-EF1-MCS-IRES-neo vector (System Biosciences). Serial deletion constructs of cMyc were generated by PCR and subcloned into pcDNA-3.1 and mutagenesis generated with Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits (Agilent, #200521). Luciferase reporter assays for TAD of EZH2 and VP1662 were conducted after fusing to Gal4’s DNA binding domain in pCMX-Gal4-DBD. Recombinant protein was produced with bacterial expression systems of pGEX6P1 (GE Healthcare) or pET28a (EMD Biosciences). Primers used for cloning are listed in Supplementary Table 11.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Followed by Sequencing (ChIP-seq).

ChIP-seq was performed using a chromatin crosslinking-based protocol63–65. Cells were collected and fixed with formaldehyde, followed by addition of glycine to stop crosslinking. After washing, lysis and sonication of cells, a fixed fraction of Drosophila melanogaster chromatin was added as spike-in control into the same amount of sonicated chromatin across all samples. Magnetic beads (Dynabeads M-280 Sheep anti-rabbit IgG; Invitrogen # 11203D) pre-conjugated with specific antibodies against the target protein (anti-EZH2 [Cell Signaling Technology, #5246] or anti-H3K27me3 [Cell Signaling Technology, #9733]), together with those against H2Av (Active Motif, #39715, for Drosophila spike-in chromatin), were added into samples for ChIP. After bead washing and elution, the eluted chromatin was de-crosslinked, followed by protein and RNA digestion and DNA purification. Multiplexed ChIP-seq libraries were prepared by using NEBNext Ultra II kit (NEB, #E7103L) and sequenced on the Nextseq 500 system using Nextseq 550 High Output Kit v2.5 (Illumina).

ChIP-seq Data Analysis

Reads were mapped to the human genome (hg19) and drosophila genome (dm3) using BWA (V0.7.12; default parameters)66. Unique reads mapped to a single best-matching location with no more than two mismatches were kept, which were then subject to removal of PCR-caused read duplicates using Picard and Samtools. We filtered out reads with a mapping quality score < 20 for downstream analysis. MACS2 was used for peak identification with data from input as controls and default parameters67. Alignment files in the bam format were transformed into read coverage files (bigwig format) using DeepTools68. Scaling factors were calculated based on the spike-in (dm3) read count as before69, and normalization done by the bamCompare function of deeptools with a bin size of 10 and read length of 250. Profiles of ChIP-Seq read densities were displayed in Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV, Broad Institute). Heatmaps for ChIP-seq signals were generated using the deepTools “computeMatrix” and “plotHeatmap” functions. Distribution of peaks were analyzed by ‘annotatePeaks.pl’ function of HOMER (Hypergeometric Optimization of Motif Enrichment)70. Motif analysis of EZH2-’solo’ peaks was performed by the SeqPos tool in Cistrome to uncover the motifs that are enriched close to the peak centers by taking the peak locations as the input71.

Cleavage Under Targets & Release Using Nuclease (CUT&RUN) and Data Analysis.

CUT&RUN34 was performed as before65 with a commercial kit (EpiCypher CUTANA™ pAG-MNase for ChIC/CUT&RUN, #15–1116). 1 million of cells were used for CUT&RUN and 5 ng of the purified CUT&RUN DNA used for construction of multiplexed libraries with the NEB Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit, followed by sequencing (by Illumina NextSeq 500). Reads were mapped to hg19 using bowtie2.3.5. The non-primary alignment, PCR duplicates, or blacklist regions were removed from aligned data by Samtools (v1.9), Picard ‘MarkDuplicates’ function (v2.20.4), and bedtools (v2.28.0), respectively. Peak calling was performed using MACS2 (macs2 callpeak -f BAMPE -g hs/mm –keep-dup 1). Deeptools (v3.3.0) was used to generate bigwig files, heatmaps and averaged plotting of signals. Genomic binding profiles were generated using deepTools ‘bam-Compare’ functions.

Recombinant Protein Purification

For the GST-fusion recombinant protein expression, the transformed E. coli BL21 bacterial cells were grown in the Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing ampicillin (50 μg/mL, Amresco) at 37°C overnight. Isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.2 mM, Sigma-Aldrich) was applied to induce protein expression when the OD600 reached 0.8. Bacterium pellets were then collected after induction at 37°C for 5 h and disrupted by sonication. GST fusion protein was purified with the slurry of Glutathione-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia, 17–0756-01) and stored at 4°C in the buffer (25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1mM DTT, 1× protease inhibitor).

The pET28a plasmid containing His6x-tagged EZH2 or cMyc was transformed into E-coli BL21(DE3) strain. LB medium with kanamycin was inoculated with the transformed bacteria cells, followed by protein expression induction with IPTG (0.4 mM) at an optical density of 2.8 and then growth for overnight at 15 °C. For protein purification, bacteria cells were resuspended in a buffer (50 mM phosphate pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF), lysed by sonication, and clarified by centrifugation at 18,000 g for 1 hour at 4 °C. The supernatant was applied on automated affinity chromatography system (AKTA, GE Healthcare) with Ni-NTA column (His-Trap HP, GE Healthcare) using buffer A (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl) and buffer B (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 250 mM Imidazole). Additional purification was performed by size exclusion chromatography on HiLoad Superdex 200 pg (26/600, GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl for EZH2-TAD and its mutant and 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol for cMyc-CD.

For recombinant p300, His6×-p300 was expressed from pFastBac1 vector in High Five Cells and purified on Ni-NTA beads in BC buffer (20 mM HEPES pH7.9, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 1mM DTT) with 100 mM NaCl and 300 mM imidazole72, 73. His6-p300 was further purified on Q Sepharose column (HiTrap, GE Healthcare) in BC buffer and eluted between 100 and 600 mM NaCl. The purity of the protein preparation was assessed on gels and the pure fractions (>90%) were collected and flash frozen till use.

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) and GST Pulldown.

Cell pellets were lysed in EBC buffer (freshly supplemented with protease/phosphatase inhibitors) on ice for 30 minutes. After sonication, debris was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 g for 15 minutes at 4 °C. 1 mg of proteins from lysate was incubated with antibodies at 4 °C, followed by addition of 10 μL of protein A/G magnetic beads (BioRad) and rotation for 3 hours at 4 °C. To test potential involvement of DNA/chromatin binding for protein-protein association, cell lysate was pretreated with 250 U/µL of benzonase nuclease (Sigma, #E1014) for 1 hour on ice, followed by IP in the presence of 10 mg/mL ethidium bromide (Invitrogen, #15585011) as reported74. For IP of tagged protein, HA-conjugated (Roche, #11815016001) or Flag beads (Sigma, #M8823) were incubated with lysate overnight at 4 °C. In vitro translated (IVT) protein was generated using pCDNA3.1 plasmids and TnT Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation System (Promega, #L1170). GST pulldown was conducted with either cell lysate or the IVT protein and 1 µg of GST-fusion recombinant protein75, 76.

Gene Knockdown (KD) and CRISPR/cas9-mediated KO.

Lentiviral shRNA plasmids for KD of EZH2 (TRCN0000010475), HUWE1 (TRCN0000073303 and TRCN0000073305) or UBR5 (TRCN0000003409 and TRCN0000003412) were obtained from Sigma, and those targeting FBW7 and SKP2 were kindly provided by Drs. Q Zhang (UT Southwestern Medical Center), H-K Lin (Wake Forest University), and W Wei (Harvard University) 77, 78. The E3 ligase FBW779, UBR580, SKP281 or HUWE182 can mediate cMyc degradation. ShRNA targeting EZH2 3UTR was cloned into a Dox-inducible Tet-pLKO-puro vector (Addgene #21915). SgRNAs targeting human EZH2 or cMyc were designed using an online tool (http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/) and cloned into pLenti-LRG-2.1-Neo (Addgene, 125593). A lentiviral plasmid that allows the Dox-inducible expression of SpCas9 was obtained from Dr. D Sabatini. Methods for reverse transcription followed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) were provided in Supplementary Note file. Information for shRNA or sgRNA is listed in Supplementary Table 11.

RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) and Data Analysis

Total RNA was first purified using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, #74136) and then treated with Turbo DNA-free kit (Thermo, #AM1907) to remove genomic DNA. For spike-in controlled RNA-seq, equal amount of ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix (Thermo, #4456740) was added into all RNA samples before library construction. Multiplexed RNA-seq libraries were subjected for deep sequencing. Reads were mapped to the reference genome followed by analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEG) as before63–65. Fastq files were aligned to the GRCh38 human genome (GRCh38.d1.vd1.fa) using STAR v2.4.283 with parameters: --outSAMtype BAM Unsorted --quantMode TranscriptomeSAM. Transcript abundance was estimated with salmon v0.1.1984 to quantify the transcriptome defined by Gencode v22. Gene level counts were summed across isoforms and genes with low counts (maximum expression < 10) were filtered for the downstream analyses. Raw read counts were used for differential gene expression analysis by DESeq2 v1.38.285 where size normalization factor was estimated based on either median-of-ratios or read counts of spike-in sequences. GSEA86 was carried out using the GSEA software (version 4.1.0) for testing enrichment of Hallmark or curated gene sets (C2). Gene sets were obtained from the Molecular Signatures Database v6.2 (MSigDB; https://www.broadinstitute.org/ gsea/msigdb/index.jsp; C2 curated gene sets or C6 oncogenic signatures). Expression heatmaps were generated using mean-centered log2 converted TPM (Transcripts Per Million) sorted in descending order based on expression values in R’s package “gplots” v3.0.3 with either no clustering or column hierarchical clustering by average linkage. Volcano plots visualizing DEGs were produced using R’s package “EnhancedVolcano” v3.11. Annotation of DEGs was conducted using either by Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) v6.887 and Metascape88. DisGeNET89 was used to annotate genes associated with human disease. BETA analysis was used to define direct target genes by integrating ChIP-seq peaks with DEG data90.

Immunoblotting (IB), Signal quantification and Protein Half-live Measurement

Cells were lysed in EBC buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol) freshly supplemented with protease/phosphatase inhibitors (Roche). Protein concentration was measured by Bradford assay (BioRad). Equal amounts of protein lysates were used for immunoblotting. To measure the stability and half-live of protein in cells, we treated cells with 0.1mg/ml of cycloheximide (CHX; a protein synthesis inhibitor) and collected cell samples at different timepoints along the CHX treatment, followed by immunoblotting of target protein using total cell lysate. Protein degradation curve was generated as before91. Quantification of immunoblotting signals was performed by normalizing to Tubulin or GAPDH signals with ImageJ. Antibody information is provided in Supplementary Table 12.

Luciferase Reporter Assay

Cells, seeded in 24-well plates, were co-transfected with plasmids of Gal4-DBD-fusion, a luciferase reporter pGL2–5xGal4-SV40 (Promega) and an internal control (pRL-CMV-Renilla). Luciferase activity was measured 48h post-transfection with Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, #E1910). Data were normalized to Renilla luciferase.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

Direct binding between EZH2-TAD and cMyc-CD was analyzed using a MicroCal iTC200 (Malvern) in 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 plus 150 mM NaCl at 25 °C. After an initial 0.4 μL injection, 13 injections from the syringe solution (500 μM of EZH2-TAD) were titrated into 300 μL of the protein solution (50 μM of cMyc-CD) in the cell, which was stirred at 1000 g. The data were fitted by single binding site model using Microcal Origin 7.0 (Malvern). The reported values represent the mean ± SD from three independent measurements.

Chemicals

Synthesis and characterization of MS177, MS177N1 and MS177N2 are described in Supplementary Note. Pomalidomide (#36471) was purchased from AstaTech. GSK126 (#S7061), EPZ6438 (#S7128), MLN4924 (#S7109) and A-485 (#S8740) were purchased from Selleck Chemical. CPI-1205 and UNC1999 were synthesized as reported15, 17. EPZ-643812, 13, GSK12614, UNC199915, C2416 and CPI-120517, A-48546, UNC685245 (kindly provided by L. James, UNC at Chapel Hill) and UNC704345 were used as before.

EZH2 Methyltransferase Inhibition Assay.

In vitro EZH2 methyltransferase assay, performed in duplicate (by Reaction Biology Corp.), monitored the transfer of a tritium(3H)-labeled-methyl group from S-Adenosyl methionine (SAM) to histone. 5 nM of the recombinant five-component PRC2 (comprising EZH2, EED, SUZ12, RBAP48 and AEBP2) was used as the enzyme, 0.05 μM of core histone as the substrate, and 1 μM of SAM as methyl donor, respectively.

Compound Selectivity.

Assays for selectivity of MS177 against 23 other methyltransferases (performed by Reaction Biology Corp.) used the same 3H-labeled SAM assay as described above, with assays against EZH1 performed in duplicate at the indicated compound concentrations and those against other methyltransferases performed in duplicate at 10 μM. Selectivity of MS177 against a panel of kinases, performed in duplicate by Eurofins Cerep, was tested at 10 μM, with compound effect calculated as percentage of inhibition relative to mock-controlled activity. Selectivity of MS177 against a panel of 45 GPCRs, ion channels and transporters was assayed at 10 μM in quadruplicate by the NIMH-PDSP (http://pdsp.med.unc.edu/) using the radioligand binding assays (per target).

Cell Growth Inhibition.

Cells, seeded in triplicate in each well of 24-well plates, were subjected to treatment of compounds at various concentrations. Medium containing fresh compounds were changed every two days. Flow-growing cell cultures were periodically diluted to keep the density less than 1x106/mL. Cell counting was conducted by an automated TC10 counter (BioRad) every two days. EC50 (half maximal effective concentration) values were calculated as before18 by using a nonlinear regression analysis of the mean ± SD from triplicated datasets for each biological assay.

Culture of Primary Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML) Patient Cells.

Cryopreserved primary mononuclear cells of de-identified AML patients (from bone marrow) were obtained from UNC’s Tissue Procurement Core Facility and cultivated on the layer of HS27 stromal cells (ATCC, #CRL-1634). Briefly, HS27 cells were first expanded in medium (DMEM base medium,10% of FBS, 1% of antibiotics), irradiated at 15 Gray (Gy), and plated at a confluent density. Cryopreserved AML cells were quickly thawed, resuspended in PBS with 5% of BSA and 8% of Dextran-40, collected by centrifugation at 500g for 5 minutes, and then resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 15% of FBS, 50 μM of β-mercaptoethanol, 1% of antibiotics, 2 mM of L-glutamine and a human cytokine cocktail comprising 100 ng/mL stem cell factor (SCF), 10 ng/mL IL3, 20 ng/mL IL6, 10 ng/mL thrombopoietin (TPO) and 10 ng/mL FLT3 ligand (Peprotech), followed by plating onto the layer of irradiated HS27 cells and co-culture at 37 °C. In vitro expansion of primary AML samples was monitored by tryptophan blue staining.

Cell Fractionation.

Cells were harvested, washed with cold PBS, and resuspended in 200 µL of CSK buffer (10 mM Pipes pH 7.0, 300 mM sucrose, 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, freshly supplemented with protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail), followed by incubation on ice for 30 minutes64, 65. Then, the sample was subject to centrifugation at 1,300 g for 5 minutes at 4 °C to collect supernatant (which contains soluble proteins) and pellet fractions (which contains the chromatin-associated proteins). Cell pellets were dissolved in 1.5x SDS loading buffer. Same amounts of protein sample were used for immunoblotting.

Ubiquitination Assay.

Cells were harvested and extracted in 100 μL of EBC buffer containing 1% of SDS. Cell extract was heat-denatured at 95 °C for 5 min and diluted with 900 μL of EBC buffer. After sonication and centrifugation, lysates were subjected to IP with antibodies of target proteins, followed by anti-ubiquitin immunoblotting.

Complete Blood Counting (CBC).

Blood of mice was collected in heparin tubes on day 5, 10, 15 and 21 by tail nick and counted by a Hemavet 950FS machine (Drew Scientific).

In Vivo Pharmacokinetics (PK) Studies.

Male Swiss albino mice (n=6) were dosed at 50 mg per kg body (mg/kg) weight via i.p. injection. Blood samples were collected into microtubes containing 20% K2EDTA solution as an anticoagulant under light isoflurane anesthesia from three mice at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 12 h. Plasma was immediately collected from blood by centrifugation at 4,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C and stored below -80 °C until bioanalysis. Concentrations of MS177 in plasma were determined by a fit-for-purpose liquid chromatography (LC)-MS/MS method. The non-compartmental-analysis tool of Phoenix WinNonlin (version 6.3) was used to assess PK parameters. Peak plasma concentration (Cmax) and time to peak plasma concentration (Tmax) were the observed values.

Patient-derived Xenograft (PDX) Models.

NOD-SCID IL2Rgnull-3/GM/SF mice (NSG-SGM3) and NOD/SCID/IL2Rgamma-null (NSG) mice were acquired from Jackson Lab. Mice were housed in a germ-free environment with food and tap water ad libitum. RT and relative humidity were held at 22°C±2 °C and 30–70% respectively. Automatic light control guaranteed a 12-h light/dark cycle (7:00 to 19:00/19:00 to 7:00). PDX cells were stably transfected with eGFP/Firefly-luciferase (FFLuc) genes92. The eGFP/FFLuc-transduced cells were injected into NSG-SGM3 mice (8-week-old females) via tail vein, expanded and harvested from spleen via sorting for GFP+/hCD33+ cells (FACSAria-II; BD Biosciences). 0.2 million of GFP+/hCD33+ PDX cells were then injected into each one of a second set of NSG-SGM3 mice for further expansion. Seven weeks later, cells were harvested from spleens of leukemic mice and then frozen in liquid nitrogen till use or immediately used for xenograft assays.

In Vivo Dosing

MS177 was dissolved in 5% of N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), 5% Solutol HS-15, 60% captisol (20% wt/vol) and 30% PEG-400. For generating subcutaneous (s.c.) xenograft models, cells (5 million for RS4;11 or PDX cells or 2 million for EOL-1 cells) were suspended in 100 µL of a 1:1 mixture of DPBS and Matrigel (Corning) and then injected s.c. into the bilateral flank of 8-week-old female NSG (used for human cell line xenograft) or NSG-SGM3 mice (used for PDX). Tumor volume (mm3) was defined with a formula of (length×width2)/2 where length and width represent the largest and perpendicular tumor diameter, respectively. Tumor volume was measured three times per week with electronic calipers. Once the s.c. tumors reached an average of 50–100 mm3, animals were randomized so that the average tumor volume at the beginning of treatment was uniform across all groups. Dosing of MS177 (i.p.) were either 100 mg/kg two times a day (BID) for 6 days (Monday to Saturday) per week or 200 mg/kg BID for 3 days (Monday, Wednesday and Friday) per week. For orthotopic xenograft models, 0.2 million of the luciferase (luc)-labeled PDX cells were injected intravenously (i.v.) to each one of NSG-SGM3 mice. Tumor growth was monitored via weekly chemiluminescence imaging of live mice following the i.p. injection with D-luciferin. Once tumors reached an average bioluminescence imaging (BLI) signal of 1×105 photons/second, animals were randomized so that the average BLI signal at the beginning of treatment was same across all groups, which were subjected to dosing as described above. Mice were monitored daily (UNC’s Animal Studies Core), with body weight and tumor growth (tumor volume or BLI signals) measured 2–3 times per week to avoid reaching maximal tumor size/burden. Investigators were blinded to allocation of mice and outcome assessment (conducted by UNC’s Animal Studies Core).

Intra-tumor/Intra-plasma Drug Concentration Analysis.

NSG mice were treated with 200 mg/kg of MS177 (i.p.) twice daily for five days. On day 5, mice were euthanized 2 h after the last treatment. For plasma preparation, 200 μL of blood was collected in EDTA-treated tubes and centrifuged at 2,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C for collecting supernatant (stored at -20 °C till use). The s.c. tumors, harvested immediately after animals were euthanized, were cut into pieces, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -20 °C. Tumor samples were homogenized in 80:20 (vol/vol) water:acetonitrile at a 1:9 (wt/vol) ratio, diluted by 5-folds, and analyzed against plasma calibration curves. MS177 concentrations in plasma and tumor samples were analyzed using LC-MS. A Waters UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 μm) was used for LC. Mobile phase A: 95:5:0.1 (vol/vol/vol) water:acetonitrile:formic acid. Mobile phase B: 50:50:0.1 (vol/vol/vol) methanol:acetonitrile:formic acid. API 6500 was used for MS/MS analysis. Electrospray was used for the ionization method (positive ion).

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 9). Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for experiments comparing two sets of data with assumed normal distribution. For comparisons of tumor growth, two-way ANOVA was used. Kaplan-Meier survival curve was statistically analyzed using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Data are presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. *, **, and *** denote the P value of < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.005, respectively. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. NS denotes not significant. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. All data from representative experiments (such as imaging and micrographs) were repeated at least two times independently with similar results.

Data Availability

Genomic dataset of this study, including ChIP-Seq, CUT&RUN and RNA-Seq, have been deposited in NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession code GSE180448. Human AML datasets were derived from TCGA Research Network (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). Publicly available datasets used in this work were from NCBI GEO accession numbers GSE113042 (ChIP-seq of H3K4me3, H3K27ac, SMARCA4 and SMARCC1 in EOL-1 cells), GSE82116 (ChIP-seq of H3K27ac, H3K9ac and POL II in MV4;11 cells), GSE73528 (ChIP-seq of MLLn and MLLc in MV4;11 cells), GSE101821 (ChIP-seq of BRD4 in MV4;11 cells), GSE29611 (ChIP-seq of EZH2 and H3K27me3 in GM12878, HUVEC and K562 cells, as well as SUZ12 in K562 cells), GSE30226 (ChIP-seq of cMyc in HUVEC and K562 cells) and GSE33213 (ChIP-seq of cMyc in GM12878 cells). Other data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1|. In MLL-rearranged (MLL-r) acute leukemia, EZH2 exhibits the noncanonical ‘solo’-binding pattern at sites enriched for the gene-activation-related histone marks and co-binding of RNA polymerase II (POL2), (co)activators and cMyc, in addition to its canonical EZH2:PRC2 sites showing H3K27me3 co-binding.

(a-b) Heatmaps showing the K-means clustered EZH2 and H3K27me3 ChIP-seq signal intensities ± 3 kb around peak centers in MV4;11 (a) and EOL-1 (b) cells. EZH2-’solo’ and EZH2-’ensemble’ refer to noncanonical EZH2+/H3K27me3- peaks (cluster 9 in MV4;11 and cluster 8 in EOL-1 cells) and canonical EZH2+/H3K27me3+ ones (clusters 1–8 in MV4;11 and clusters 1–7 in EOL-1 cells), respectively.

(c) Averaged EZH2 and H3K27me3 ChIP-seq signals around ± 3 kb from the centers of the EZH2-’solo’-binding peaks in MV4;11 (top) and EOL-1 (bottom) cells.

(d) Venn diagram showing the overlap between the called EZH2 and H3K27me3 peaks in MV4;11 (top) and EOL-1 (bottom) cells.

(e) Motif search analysis of the EZH2-’solo’-binding peaks in MV4;11 cells by using the SeqPos tool in Cistrome.

(f) Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) using anti-HA antibodies for assaying interaction between Flag-EZH2 and HA-p300 in 293T cells.

(g) Co-IP for endogenous EZH2 and MAX using anti-cMyc antibody in EOL-1 or MOLM-13 cells after the treatment of benzonase and ethidium bromide.

(h) Co-IP for interaction between endogenous cMyc and EZH2 in 293T cells by using either anti-cMyc (upper) or anti-EZH2 (bottom) antibodies.

(i) Co-IP using anti-HA antibodies for interaction between endogenous EZH2 and the transiently expressed HA-cMyc in 293T cells.

(j) Co-IP using anti-cMyc antibodies for interaction between the transiently expressed Flag-EZH2 and endogenous cMyc in 293T cells.