Abstract

Helicobacter pylori is the major causative agent of chronic antral gastritis and is thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALToma) developing in the human stomach. The aim of this study was to clarify whether corporal autoimmune gastritis (AIG), which is known to decrease acidity due to destruction of parietal cells, predisposes mice to H. pylori infection, thereby leading to MALToma-like pathology. BALB/c mice in which AIG had been induced by thymectomy 3 days after birth (AIG mice) were used. The AIG mice were orally administered mouse-adapted H. pylori at the age of 6 weeks and were examined histologically and serologically after 2 to 12 months. The results were compared with those obtained from uninfected AIG mice and infected normal mice. Germinal centers were induced in the corpus in 57% of the H. pylori-infected AIG mice, which elicited anti-H. pylori antibody responses in association with upregulation of interleukin-4 (IL-4) mRNA. In these mice, parietal cells remained in the corpus mucosa. These findings were in contrast to those with the uninfected AIG mice: fundic gland atrophy due to disappearance of parietal cells associated with upregulation of gamma interferon, but not IL-4, mRNA and no germinal center formation in the corpus. These observations suggest that AIG alters the infectivity of H. pylori, leading to MALToma-like follicular gastritis, at an early stage after H. pylori infection.

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium which is considered to play an etiological role in the development of chronic atrophic gastritis, peptic ulcer, gastric cancer, and lymphoma (26, 31). Penetration into the epithelial mucus layers seems to permit the successful proliferation of this bacterium in an acidic environment (4, 16). Epidemiological evidence supporting the possibility that Helicobacter infection may be one of the essential preconditions for gastric cancer and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALToma) (6, 33) has also accumulated.

It was recently reported that in Mongolian gerbils, which are known to develop duodenal ulcer and intestinal metaplasia in response to an ordinal strain of H. pylori (10), 37% of the animals infected with a gerbil-adapted human H. pylori strain developed gastric cancer (32). Such a disease model has not yet been established in mice. However, it is well known that the antrum (not the corpus) is preferentially infected with Helicobacter (3, 5, 8, 18, 28), suggesting that local factors, including pH, may influence Helicobacter infection in mice.

Unlike type B gastritis, type A atrophic gastritis, which develops in the corpus mucosa but not in the antrum, is a typical organ-specific autoimmune disease (30) which is known to produce autoantibodies to some molecules, including H+,K+-ATPase and intrinsic factor (12, 19). Murine autoimmune gastritis (AIG), spontaneously occurring in BALB/c mice subjected to thymectomy (Tx) 3 days after birth (d3-Tx mice), is induced by CD4+ T cells (29) belonging to the Th1 subtype (22). Murine AIG shares many pathological and clinical features with human type A gastritis, such as mononuclear cell infiltration and the destruction of parietal cells in the corpus in association with an increase of mucus pH (14, 29). The corpus glands in these mice with AIG (AIG mice) are replaced by mucous neck cells, usually resulting in epithelial hyperplasia. Acidity in these hypertrophic lesions is markedly decreased compared to that in normal areas when measured by using test papers. Even in BALB/c mice, which are known to be low responders to Helicobacter (5, 8, 18, 28), an environment where the local pH becomes higher than that under physiological conditions may allow the preferential colonization of Helicobacter in the corpus mucosa, resulting in lymphoproliferative responses, intestinal metaplasia, or carcinoid reactions.

The present study was undertaken to determine whether AIG predisposes mice to Helicobacter infection, thereby preferentially leading to a pathological change similar to MALToma. The d3-Tx BALB/c mice were monitored by immunohistological and serological methods for the production of anti-parietal cell autoantibodies, which are known to correlate well with histopathological changes. Autoantibody-positive mice were infected with H. pylori which had been adapted for mice (32) at the age of 6 weeks. At intervals between 2 and 12 months after infection, histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations of the stomachs were carried out in parallel with serological analysis for antibody production in response to both parietal cells and H. pylori.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and Tx.

Male and female BALB/c.Cr.Slc mice were bred in the Facility of Experimental Animals at the Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto University, under specific-pathogen-free conditions. Neonatal Tx was performed 3 days after birth (d3-Tx) under ether anesthesia, as described previously (19).

Bacteria.

The inoculated H. pylori strain, TN2FG4 (CagA and VacA positive), which was isolated from a patient, was kindly provided by M. Nakao (Pharmaceutical Research Division, Takeda Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan) (32). It was maintained in Blood Agar Base no. 2 with horse serum (5%, vol/vol) containing amphotericin B (2.5 mg/liter), trimethoprim (5 mg/liter), polymixin (1,250 IU/liter), and vancomycin (10 mg/liter). Plates were incubated in a microaerophilic atmosphere at 37°C for 48 h.

Infection.

Forty-eight 6-week-old anti-parietal cell antibody-positive d3-Tx mice were orally infected with 109 H. pylori organisms. Another 30 d3-Tx mice were given saline as a control group. Thirty age-matched non-Tx normal mice were also maintained in the same animal care room as a negative control group. In a preliminary study, the infectivity of H. pylori (TN2GF4) was studied by using the bacterial culture system of a whole stomach as described previously (32).

Serological examination.

At 6-week intervals after the Tx, sera were tested for immunofluorescence to detect antibody to parietal cells by using frozen sections (6 μm) of normal stomach, as described previously (19). Sera were also examined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with extracts prepared from the normal gastric mucosa as an antigen, as described in detail elsewhere (19). Antibodies against H. pylori were measured by ELISA. Antigens were extracted by sonication of bacteria in NP-40–Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.4, 0.01 M). Either gastric or bacterial extracts were diluted with phosphate-buffered saline at 50 to 100 μg/ml, and 0.1 ml of each extract was plated. As a control, phosphate-buffered saline was plated instead of the extract. After overnight incubation at 4°C, 0.1 ml each of the serially diluted sera separated from infected or uninfected mice was plated, followed by incubation at room temperature for 1 h and washing. Horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig) (Cappel, Durham, N.C.), diluted at a predetermined concentration, was added to each well. After a 1-h incubation, each well was reacted with a substrate (o-aminobenzidine) solution for 15 min after rigorous washing. The reaction was terminated with 25 μl of 2 M H2SO4, and the absorbence at 500 nm (A500) was determined with an ELISA reader. In one experiment, antibodies against each Ig class and subclass were used as inhibitors to determine the classes of the anti-parietal cell and anti-Helicobacter antibodies.

Histological examination.

The stomachs, regional lymph nodes, and spleens of the infected and control mice were fixed in 10% formalin (or, in some experiments, Carnoy's solution), embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin or Giemsa stain. The degree of gastritis, estimated by mononuclear cell infiltration and the development of fundic gland atrophy due to the loss of chief and parietal cells in the corpus, was determined by using the modified Sakagami semiquantitative scoring system (27), in addition to follicle formation, as follows: 0, no increase in inflammatory cells, no fundic gland atrophy, and no appearance of secondary follicles; 1, scattered infiltration of the lamina propria by lymphocytes and some eosinophils, mild fundic gland atrophy, and one to three follicles in the entire area of each section; 2, moderately dense infiltration of the lamina propria by lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, and some histiocytes, moderate fundic gland atrophy, and four to six follicles; and 3, dense and massive infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells, some eosinophils and histiocytes, severe fundic gland atrophy, and more than one follicle per visual field when observed at a magnification of ×10. The data for each histological score were expressed as mean score ± standard error.

Measurement of local pH.

The local pH in the corpus areas of stomachs of normal and d3-Tx AIG mice, either infected or uninfected, was measured with test papers (CombiStick; Sankyo Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemical examinations.

Frozen sections (6 μm thick) prepared from each stomach were stained by the sandwich technique, using monoclonal antibodies against CD4 (GK1.5; PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) and CD8 (KT15; Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom) for T cells, B220 (RA3-6B2; Cederlane, Hornby, Ontario, Canada) for B cells, and Mac-1 (M1/70; PharMingen) for macrophages as the first antibodies and horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rat IgG or anti-rabbit Ig (Cappel) as the second antibody.

Preparation of DNA.

The samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored until DNA extraction. Total DNA was extracted with a DNA extraction solution, SEPAGENE (Sanko Junyaku Co., Tokyo, Japan).

PCR.

PCRs were performed with a mixture of 100 ng of extracted DNA, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mM MgCl2, a 200 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and a 30 pM concentration of each specific primer. The two primers HPU1 (5′GCCAATGGTTAGTT3′) and HPU2 (5′CTCCTTAATTGTTTTTAC3′) amplified a 411-bp product from the urease A gene, which is one of two genes encoding the urease of H. pylori (22). The reaction conditions were as follows: denaturing at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 45°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min. The reaction was carried out for 35 cycles in a Gene Amp PCR system 9600 (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.).

Southern blot analysis.

To confirm the amplification of the appropriate DNA fragments, the PCR products were electrophoresed in a 1% agarose gel and transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond-N+; Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). The membrane was hybridized at 65°C in hybridization buffer, and a 32P-labeled cDNA probe was made from the PCR products amplified by the HPU1 and HPU2 primers of H. pylori (TN2FG4). After a 16-h hybridization, the products were washed twice in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M sodium chloride plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at room temperature and twice for 30 min in 0.1× SSC–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 65°C, before being subjected to autoradiography. Total 32P radioactivity was estimated with a BAS 2000-II imaging analyzer (Fuji Photo Film Co., Tokyo, Japan).

RT-PCR.

To analyze cytokine gene expression by the reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR method, total RNA was extracted with an RNA extraction solution, ISOGEN (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan), from the five pooled murine stomachs. It was reverse transcribed into DNA with the Super Script preamplification system (GIBCO BRL, Life Technologies, Inc., Rockville, Md.). The total RNA in the reaction mixture was heated at 42°C for 50 min and at 70°C for 15 min and then chilled on ice. PCR was performed with a mixture of cDNA, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, a 200 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, a 50 pM concentration of each specific primer, and AmpliTaq Gold (Perkin-Elmer, Branchburg, N.J.). The specific primers used were as follows: for gamma interferon (IFN-γ), 5′, TGCATCTTGGCTTTGCAGCTTTCCTCATGGC, and 3′, TGGACCTGTGGGTTGTTGACCTCAAACTTGGC, for interleukin-4 (IL-4), 5′, CCAGCTAGTTGTCATCCTGCTCTTCTTTCTCG, and 3′, CAGTGATGTGGACTTGGACTCATTCATGGTGC. Each reaction was carried out at 94°C for 9 min, 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. A 5-μl aliquot of amplified DNA reaction mixture was subjected to 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide, and the amplified product was visualized by UV fluorescence. mRNAs isolated from Th1 clone cells (no. 16, an alloreactive T-cell clone, provided by H. Nariuchi, Tokyo University) and Th2 clone cells (D10.G4.1, provided by C. Janeway, Yale University) were used as positive controls for IFN-γ and IL-4, respectively.

Statistical analysis.

The generalized Wilcoxon test was used to compare histological scores between the groups. A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Histopathology.

The results of the histopathological studies of the gastric mucosa are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Approximately 65% of the uninfected d3-Tx mice developed severe inflammation in the corpus, with no or only weak inflammation in the antrum mucosa (Table 1). As has been reported previously (23), mononuclear cell infiltration appeared in the lamina propria of the corpus mucosa 1 month after d3-Tx in association with the production of autoantibodies to parietal cells. At 2 to 3 months after d3-Tx, the inflammatory cells expanded along the glands and there was destruction of the parietal and chief cells, resulting in glandular atrophy which was replaced by proliferating mucous neck cells (Fig. 1a). No germinal centers were observed, and the diffusely or massively infiltrating cells consisted mainly of lymphocytes and a few other cell types, including plasma cells and macrophages. The mean local pH in 24 AIG mice was 4.3 when measured with test papers, while that in the normal corpus glands was consistently less than 2.

TABLE 1.

Histopathology of the corpus mucosa in H. pylori-infected normal and d3-Tx BALB/c mice

| Micea | Time (mo) | n | No. with mononuclear cell infiltration (avg score)b | No. with secondary lymph follicle (avg score)b | No. with LEL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uninfected d3-Txc | 2–12 | 18 | 18 (2.50 ± 0.19) | 0 | 0 |

| Infected normald | 2–12 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infected d3-Tx | 2 | 5 | 4 (1.80 ± 0.37) | 4 (1.40 ± 0.40) | 3 |

| 4 | 12 | 12 (1.97 ± 0.26) | 7 (1.00 ± 0.33) | 5 | |

| 6 | 11 | 9 (2.27 ± 0.24) | 7 (1.09 ± 0.28) | 4 | |

| 12 | 10 | 9 (1.20 ± 0.13) | 5 (0.70 ± 0.26) | 3 |

Either saline or H. pylori was administered 6 weeks after d3-Tx.

The numbers in parentheses indicate means and standard errors of scores estimated by the histopathological criteria (see Materials and Methods).

Anti-parietal cell antibody-positive mice were selected.

Six of 25 mice demonstrated weak mononuclear cell filtration in the antrum.

TABLE 2.

Fundic gland atrophy in H. pylori-infected d3-Tx mice with or without secondary follicles

| Time (mo) after H. pylori infection | Atrophy scorea(n)

|

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follicle-positive mice | Follicle-negative mice | ||

| 2 | 0.50 ± 0.29 (4) | 0 (1) | |

| 4 | 0.43 ± 0.30 (7) | 1.20 ± 0.58 (5) | 0.0277 |

| 6 | 0.43 ± 0.20 (7) | 1.0 ± 0.70 (4) | 0.0219 |

| 12 | 0.40 ± 0.24 (5) | 0.40 ± 0.40 (5) | NSb |

| Controlc | 2.47 ± 0.21 (18) | ||

Semiquantitative scoring of the levels of fundic gland atrophy in d3-Tx mice infected with H. pylori was carried out according to the histopathological criteria described in Materials and Methods and expressed as 0 to 3. Data are means and standard errors.

NS, not significant.

Uninfected d3-Tx mice.

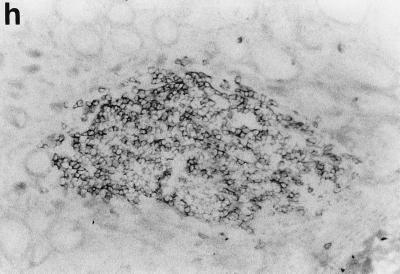

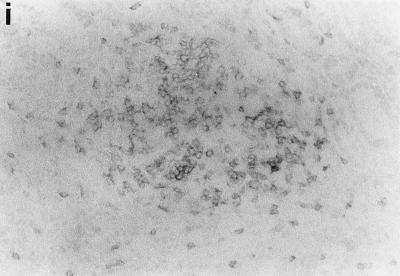

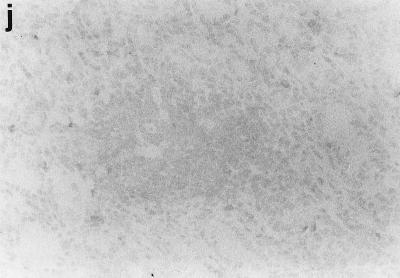

FIG. 1.

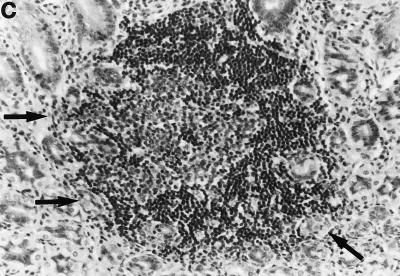

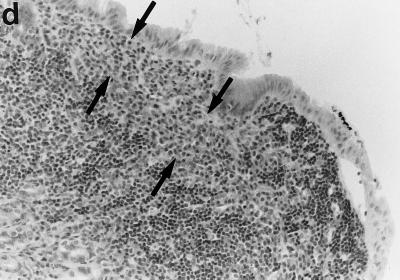

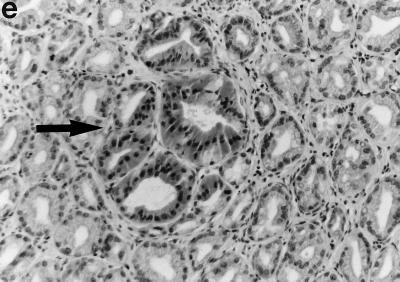

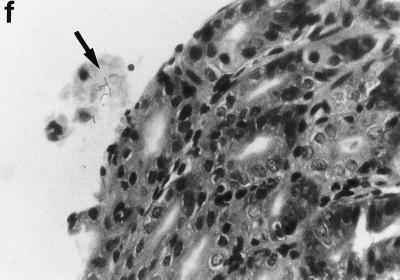

Sections of gastric mucosae of d3-Tx (a to f and h to j) and normal (g) BALB/c mice given saline or H. pylori orally at the age of 6 weeks. (a) Four months after saline administration; (b, c, d, f, g, h, i, and j) 4 months after H. pylori administration; (e) 12 months after H. pylori administration. (a) The body mucosa, showing the infiltration of mononuclear cells and gland atrophy characterized by loss of parietal and chief cells and replacement with proliferating epithelial cells. Magnification, ×125. (b) Germinal center formation in the body mucosa and persistence of parietal cells (arrowheads). Magnification, ×50. (c) Germinal center and LEL (arrows). Magnification, ×250. (d) Massive proliferation of plasma cells in the body mucosa. Magnification, ×250. (e) Mucin-producing cells and cells which have eosinophilic cytoplasm in the corpus. Magnification, ×125. (f) Colonization of the body pits by H. pylori. Magnification, ×500. (g) Low lymphocyte infiltration in the gastric mucosa in a normal BALB/c mouse after H. pylori infection. Magnification, ×125. (h, i, and j) Massive B220+ cells, scattered CD4+ cells, and no CD8+ cells, respectively, in the lymph follicle of a d3-Tx mouse 4 months after H. pylori infection. Magnification, ×250. (a to e and g) Hematoxylin-eosin staining; (f) May-Grunwald Giemsa staining; (h to j) immunohistochemical staining.

Compared to that in the uninfected d3-Tx mice, the mononuclear cell infiltration in the H. pylori-infected d3-Tx mice was often massive and localized at the bottom of the lamina propria in the corpus mucosa. Such a histological feature in these infected mice resulted in no significant difference in mononuclear cell infiltration score compared to the uninfected mice (Table 1). In addition, in the H. pylori-infected d3-Tx mice, secondary follicles developed in the corpus mucosa in many instances (in 4 of 5 mice at 2 months, 7 of 12 mice at 4 months, 7 of 11 mice at 6 months, and 5 of 10 mice at 12 months after infection) (Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 1b and c). Lymphoepithelial lesions (LEL) and massive infiltration of plasma cells (Fig. 1d, arrows) were often found in and around the mantles of germinal centers (Fig. 1c, arrows) in some of these mice. These findings were not present in the uninfected d3-Tx mice. In total, approximately 60% (23 of 38) of the infected d3-Tx mice exhibited follicular gastritis (Table 1).

As seen in Fig. 1a, the atrophy of the fundic glands accompanied by loss of parietal cells, which was characteristic of uninfected d3-Tx mice, was not observed in the infected d3-Tx mice, whose parietal cells were usually well preserved or recovered (Fig. 1b, arrowheads). The development of follicular gastritis in association with a recession of the gland atrophy, which was the most characteristic feature in the infected d3-Tx mice, was also well demonstrated by the semiquantitative atrophy scores (Table 2). The atrophy scores in non-follicle-forming d3-Tx mice infected with H. pylori (for 4- and 6-month infections) were significantly higher (2.5- to 3.0-fold on average) than those in follicle-forming infected d3-Tx mice.

In a small number of mice (2 of 10 at 12 months after infection), the surface of the epithelium overlying lymphoid aggregates was markedly hyperplastic. The surface epithelia of these mice were invaginated into the submucosae, resulting in complex branching structures surrounded by lymphocytic infiltrates and in microabscesses in gastric pits. Some epithelial cells having eosinophilic cytoplasm, similar to Paneth cells (Fig. 1e), and the replacement of surface mucous cells by mucin-producing cells with mucicarmine-positive vacuoles and secretory granules in the cytoplasm were also observed in wide areas of the corpus mucosa. Disappearance of parietal cells (corpus gland atrophy) and lack of germinal center formation were noted in these mice. In contrast to the case for these H. pylori-infected d3-Tx mice, there was little infiltration of mononuclear cells in the gastric mucosae of the non-d3-Tx BALB/c mice infected with H. pylori (Fig. 1g).

The phenotypes of the infiltrating mononuclear cells in the body mucosae of d3-Tx mice uninfected or infected with H. pylori were analyzed by immunoperoxidase staining for CD4, CD8, Mac-1, and B220. A major portion of the lymphocytes infiltrating the gastric mucosa in both groups of mice for up to 12 months during the study were CD4+ T cells, while a small number of CD8+ cells appeared in the later stages. Although H. pylori infection did not significantly alter the distribution pattern of T cells, the most characteristic change was follicle formation with B cells, which were stained by B220 (Fig. 1h, i, and j). Mac-1 was detected on some infiltrating cells, including macrophage-like cells, in the inflammatory lesions of the H. pylori-infected and uninfected d3-Tx mice but not in the mucosae of the normal control mice (data not shown).

Infection with H. pylori.

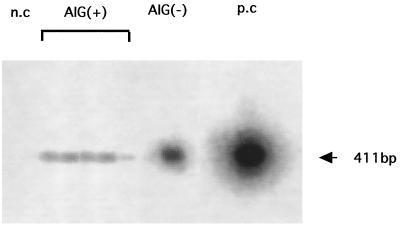

In a culture study using a whole stomach, bacterial counts were not significantly different for non-Tx BALB/c mice (n = 6; 2.0 ± 0.5 log CFU/whole gastric wall) and AIG mice (n = 6; 2.3 ± 1.1 log CFU/whole gastric wall) 8 weeks after H. pylori infection. However, bacterial aggregates were frequently observed in the antrum, but few were observed in the corpus, of H. pylori-infected non-d3-Tx BALB/c mice. In contrast, aggregates of microorganisms were observed on the surface of the corpus and antrum mucosae in the experimental mice (Fig. 1i). Colonization by H. pylori was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis for the urease gene A with DNA extracted from the gastric mucosa of each infected mouse, as shown in Fig. 2. Urease A genes were positive in all of the five AIG mice infected with H. pylori after 4 months but not in the pooled stomachs of the age-matched AIG or normal uninfected mice. No H. pylori infection was observed in 18 uninfected normal BALB/c mice during the period of the experiment when tested by PCR (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Expression of the H. pylori-urease A gene in the gastric mucosae of d3-Tx AIG [AIG(+)] and normal [AIG(−)] mice infected with H. pylori. The PCR products of extracted DNAs were analyzed by Southern blotting as described in Materials and Methods. n.c, negative control with DNA from uninfected normal mice; p.c, positive control with DNA extracted from H. pylori. Five AIG mice were analyzed individually, but the pooled gastric mucosae of three normal mice were used for the experiment. The five AIG mice were positive for the urease A gene, and the normal mice were negative.

Serology.

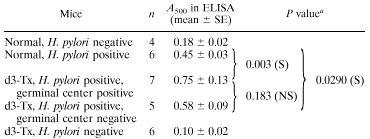

The kinetics of the autoantibody responses measured by ELISA, with gastric extract as the antigen, in mice selected by indirect immunofluorescence staining for anti-parietal cell autoantibody 6 weeks after d3-Tx treatment were consistent with those measured by immunofluorescence staining. All of the H. pylori-infected AIG mice maintained significantly high levels of anti-parietal cell autoantibody compared with the normal mice 2 to 12 months after H. pylori infection (data not shown). These d3-Tx mice also showed significantly high anti-H. pylori antibody responses 4 months after the infection compared to the H. pylori-infected non-Tx normal mice. Table 3 shows a comparison of the A500 values of sera, diluted 1:40, from the germinal center-positive and -negative mice. Although the difference was not statistically significant, there was a tendency for germinal centers to be formed in mice showing relatively high anti-H. pylori responses. In addition, the levels of anti-H. pylori antibody in serum in both the germinal center-positive and -negative d3-Tx mice were significantly higher than those in the uninfected d3-Tx and non-Tx mice and in the infected non-Tx mice after 4 months. These findings, together with those for the urease gene (Fig. 2), indicate the successful infection by H. pylori of BALB/c mice with AIG. However, levels of anti-parietal cell antibodies in serum in AIG mice generally decreased after H. pylori infection (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Anti-H. pylori antibody responses of d3-Tx germinal center-positive and -negative BALB/c mice at 4 months after the H. pylori infection

|

S, statisically significant; NS, not significant.

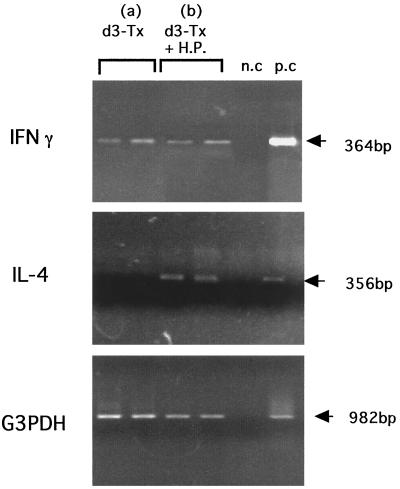

Cytokine messages.

The expression patterns of the landmark cytokine mRNAs which identified the Th1 and Th2 subtypes of the infiltrating CD4+ T cells were determined by RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 3, IFN-γ was expressed in all of the non-H. pylori-infected d3-Tx mice tested at 5.5 months of age, whereas no IL-4 message was detected in these mice. In contrast, both IFN-γ and IL-4 were expressed in the age-matched d3-Tx mice at 4 months after H. pylori infection.

FIG. 3.

Expression of IFN-γ and IL-4 mRNAs in the gastric mucosae of d3-Tx AIG mice at 4 months after saline ingestion (a) or H. pylori (H.P.) infection (b). Saline or H. pylori was administered to each AIG mouse at the age of 6 weeks. Total RNAs were extracted from the mucosae of the five pooled stomachs, and RT-PCR was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Five individual mice were tested for each group. n.c, negative controls without template DNA; p.c, positive controls with mRNAs isolated from Th1 clone cells (no. 16) for IFN-γ and Th2 clone cells (D10.G4.1) for IL-4. G3PDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

DISCUSSION

Severe fundic gland atrophy due to the loss of parietal and chief cells is one of characteristic features observed in d3-Tx AIG BALB/c mice (23). The present findings showed that oral administration of murine-adapted H. pylori to these d3-Tx AIG BALB/c mice caused marked changes in the pathology of the gastric body. The most characteristic feature was germinal center formation in the corpus mucosa in association with the persistence of parietal cells, similar to that seen in low-grade MALToma in humans (11, 33). It has been reported that long-term (22 month) infection with Helicobacter felis in normal BALB/c mice induced MALToma-like lesions in the gastric mucosa (5). However, the histological changes observed in the present study occurred 2 to 4 months after infection in d3-Tx BALB/c mice with AIG.

Susceptibility to Helicobacter infection in mice is dependent on at least two types of factors: local and host. H. felis preferentially colonizes in the antrum, antrum-body border, and cardia, where local acid production is low, while it barely colonizes in the body, where acid production is high (3). Thus, local acid production appears to be crucial for Helicobacter infection in the stomach. The local pH in the corpus mucosae of the present d3-Tx AIG mice was higher (by approximately three- to sixfold) than that in the normal corpus glands (less than twofold). This seems to allow the successful colonization of H. pylori, resulting in the development of H. pylori-induced diseases in these mice. A recent report that anti-H+,K+-ATPase autoantibody is detected in a high proportion of H. pylori-infected patients (2) is consistent with our observation.

Another factor is linked to the genetic background of the host. The severity of Helicobacter-associated gastritis differs between mouse strains. The intensity of inflammation is severe in C57BL/6J and C3H mice and weak in BALB/c mice (5, 8, 18, 28). These observations suggest possible contributions of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and non-MHC genes to Helicobacter-induced inflammation. The involvement of MHC genes in the pathogenesis of Helicobacter-induced gastric diseases could be supported by the differences in immunological functions between C57BL/6J and BALB/c mice. C57BL/6J mice are known to show Th1-dominated responses, while BALB/c mice show Th2-dominated responses, to intracellular infections such as that with Leishmania major (9). It has been reported that the Th1 response is associated with the pathogenesis of Helicobacter-induced diseases and that the Th2 response is associated with protection from or control of the infection (17). These associations may explain the difference in susceptibility to H. pylori between C57BL/6J and BALB/c mice and the induction of intensive B-cell responses in the corpus mucosae of AIG BALB/c mice. The high anti-H. pylori antibody responses and the expression of urease mRNA indicate the successful colonization of H. pylori in the corpus mucosae of infected AIG mice, leading to intensive B-cell responses.

Th1 plays a cardinal role in the induction of various organ-specific autoimmune diseases (20), including AIG in d3-Tx BALB/c mice (27). However, it has also been shown that a high level of anti-parietal cell autoantibodies is produced in association with tissue damage in these mice (19), indicating that both Th1 and Th2 cells are activated in these mice at the same time. It is now well established that Th1 and Th2 follow distinct developmental pathways in response to quite different stimuli (21). As reported in our previous article (13), the IFN-γ message, which is a marker for Th1, was detected in the corpus mucosa of d3-Tx AIG mice, while the IL-4 message, which is a marker for Th2, was not found in the corpus but was present in the regional lymph nodes of these mice. This indicates that the Th1 response dominates in the corpus, where gastritis develops. The results of this study demonstrated that H. pylori infection caused changes in IFN-γ and IL-4 production in d3-Tx AIG mice. Intensive B-cell responses associated with germinal center formation were induced by H. pylori infection. Corpus gland atrophy, possibly caused by Th1 killers (17, 23), and the persistence of parietal cells in these H. pylori-infected d3-Tx mice would be indicative of the mutual exclusion of Th1 and Th2 functions (7). One explanation is that Th2 responses to H. pylori expanding in the corpus of AIG mice suppress the functions of parietal cell-specific Th1 effectors. IL-4, which was upregulated in the corpus mucosa, is reported to be critical for germinal center formation (1). The gene expression of IL-10 and lymphotoxin-α, both of which are known to be involved in germinal center formation (15, 25), is upregulated in the gastric mucosae of H. pylori-infected d3-Tx AIG mice but not in those of uninfected mice (unpublished data).

The monoclonality of Igs is regarded as a feature of lymphoma, including human MALToma (24). Further investigations on this subject are in progress. However, our results demonstrate that follicular gastritis similar to low-grade MALToma-like lesions develops in the stomachs of d3-Tx AIG mice at an early stage after H. pylori infection and at a high frequency. This seems to represent a suitable murine model for investigating the role of Helicobacter in MALToma induction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Ministry of Culture and Science of Japan (09670543, 11670495), a Grant-in-Aid for “Research for the Future” Program from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS-RFTF97I00201), and Supporting in Research Funds from the Japanese Foundation for Research and Promotion of Endoscopy (JFE-1997).

REFERENCES

- 1.Choe J, Kim H, Armitage R J, Choi Y S. The functional role of B cell antigen receptor stimulation and IL-4 in the generation of human memory B cells from germinal center B cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:3757–3766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Claeys D, Faller G, Appelmelk B J, Negrini R, Kirchner T. The gastric H,K-ATPase is a major autoantigen in chronic Helicobacter pylori gastritis with body mucosa atrophy. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:340–347. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danon S J, O'Rourke J L, Moss N D, Lee A. The importance of local acid production in the distribution of Helicobacter felis in the mouse stomach. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1386–1395. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90686-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eaton K A, Brooks C L, Morgan D R, Krakowks S. Essential roles of urease in pathogenesis of gastritis induced by Helicobacter pylori in gnotobiotic piglets. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2470–2475. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2470-2475.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enno A, O'Rourke J L, Howlett C R, Jack A, Dixon M F, Lee A. MALToma-like lesions in the murine gastric mucosa after long-term infection with Helicobacter felis—a mouse model of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric lymphoma. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:217–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eurogast Study Group. An international association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. Lancet. 1993;341:1359–1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiorentino D F, Bond M W, Mosmann T R. Two types of mouse T helper T cells. IV. Th2 clones secrete a factor that inhibits cytokine production by Th1 clones. J Exp Med. 1989;170:2081–2095. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox J G, Li X, Cahill R J, Andrutis K, Rustgi A K. Hypertrophic gastropathy in Helicobacter felis-infected wild-type C57BL/6 mice and p53 hemizygous transgeneic mice. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:155–166. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8536852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heinzel F P, Sadic M D, Holaday B J, Coffman R L, Locksley R M. Reciprocal expression of interferon gamma or interleukin 4 during the resolution or progression of murine leishmaniasis. Evidence for expansion of distinct helper T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 1989;169:59–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirayama F, Takagi S, Kusuhara H, Iwao E, Yokoyama Y, Ikeda Y. Induction of gastric ulcer and intestinal metaplasia in Mongolian gerbils infected with Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:755–757. doi: 10.1007/BF02347631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isaacson P, Wright D H. Malignant lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. A distinctive type of B-cell type. Cancer. 1983;52:1410–1416. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19831015)52:8<1410::aid-cncr2820520813>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones C M, Callaghan J M, Gleeson P M, Mori Y, Masuda T, Toh B H. The parietal cell autoantibodies recognized in neonatal thymectomy-induced murine gastritis are the α and β subunits of the gastric proton pump. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:287–294. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katakai T, Mori K, Masuda T, Shimizu A. Differential localization of Th1 and Th2 cells in autoimmune gastritis. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1325–1334. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.9.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kojima A, Taguchi O, Nishizuka Y. Experimental production of possible autoimmune gastritis followed by macrocytic anemia in athymic nude mice. Lab Invest. 1980;42:387–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto M, Lo S F, Carruthers J L, Min J, Mariathasan S, Huang G, Pias D R, Martin S M, Geha R S, Nahm M H, Chaplin D D. Affinity maturation without germinal centers in lymphotoxin-α-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;382:462–466. doi: 10.1038/382462a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mobley H L T, Hausinger R P. Microbial urease: significance, regulation, and molecular characterization. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:85–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.85-108.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammadi M, Nedrud J, Redline R, Lycke N, Czinn S J. Murine CD4 T-cell response to Helicobacter infection: TH1 cells enhance gastritis and TH2 cells reduce bacterial load. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1848–1857. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohammadi M, Redkine R, Nedrud J, Czinn S. Role of the host in pathogenesis of Helicobacter-associated gastritis: H. felis infection of inbred and congenic mouse strains. Infect Immun. 1996;64:238–245. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.238-245.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mori Y, Fukuma K, Adachi Y, Shigeta K, Kannagi R, Tanaka H, Sakai M, Kuribayashi K, Uchino H, Masuda T. Characterization of parietal cell autoantigens involved in neonatal thymectomy-induced murine autoimmune gastritis using monoclonal antibodies. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:364–375. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mosmann T R, Sad S. The expanding universe of T-cell subsets: Th1, Th2 and more. Immunol Today. 1996;17:138–146. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mosmann T R, Coffman R L. Heterogeneity of cytokine secretion patterns and functions of helper T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishio A, Hosono M, Watanabe Y, Sakai M, Okuma M, Masuda T. A conserved epitope on H+/K+-adenosine-triphosphatase of parietal cells discerned by a murine gastritogenic T cell clone. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1408–1414. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90543-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishio A, Katakai T, Oshima C, Kasakura S, Sakai M, Yonehara S, Suda T, Nagata S, Masuda T. A possible involvement of Fas-Fas ligand signaling in the pathogenesis of murine autoimmune gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:959–967. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okazaki K, Morita M, Yamamoto Y. Rearrangements, Helicobacter pylori, and gastric MALT lymphoma. Lancet. 1994;343:1636–1636. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)93087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasparakis M, Alexopoulou L, Episkopou V, Kollias G. Immune and inflammatory responses in TNFα-deficient mice: a crucial requirement for TNFα in the formation of primary B cell follicles, follicular dendritic cell networks and germinal centers, and in the maturation of the humoral immune response. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1397–1411. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rollason T P, Stone J, Rhodes J M. Spiral organisms in endoscopic biopsies of the human stomachs. J Clin Pathol. 1984;37:23–26. doi: 10.1136/jcp.37.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakagami T, Dixon M, O'Rourke J, Howlett R, Alderuccio F, Vella J, Shimoyama T, Lee A. Atrophic gastric changes in both Helicobacter felis and Helicobacter pylori infected mice are host dependent and separate from antral gastritis. Gut. 1996;39:639–648. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.5.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakagami T, Dixon M, O'Rourke J, Howlett R, Alderuccio F, Vella J, Shimoyama T, Lee A. Atrophic gastric changes in both Helicobacter felis and Helicobacter pylori infected mice are host dependent and separate from antral gastritis. Gut. 1996;39:639–648. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.5.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakaguchi S, Fukuma K, Kuribayashi K, Masuda T. Organ-specific autoimmune diseases in mice by elimination of T cell subset. 1. Evidence for the active participation of T cells in natural self-tolerance; deficit of a T cell subset as a possible cause of autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 1985;161:72–87. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.1.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strickland R, Mackay I. A reappraisal of the nature and significance of chronic atrophic gastritis. Dig Dis Sci. 1973;18:426–440. doi: 10.1007/BF01071995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warren J R. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet. 1983;1:1273–1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watanabe T, Tada M, Nagai H, Sasaki S, Nakao M. Helicobacter pylori infection induces gastric cancer in Mongolian gerbils. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wortherspoon A C, Doglioni C, Diss T C, Pan L X, Moschini A, Deboni M, Isaacson P G. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:575–578. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91409-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]