Abstract

We have purified lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from 10 Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates which were selected on the basis of chemotype and antigenic variation. Data from immunoblotting of the purified LPS with sera from humans with H. pylori infection and from absorption of the sera with LPS indicated the presence of two distinct epitopes, termed the highly antigenic and the weakly antigenic epitopes, on the polysaccharide chains. Among 68 H. pylori clinical isolates, all smooth strains possessed either epitope; the epitopes were each carried by about 50% of the smooth strains. Thus, H. pylori strains can be classified into three types on the basis of their antigenicity in humans: those with smooth LPS carrying the highly antigenic epitope, those with smooth LPS carrying the weakly antigenic epitope, and those with rough LPS. Sera from humans with H. pylori infection could be grouped into three categories: those containing immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against the highly antigenic epitope, those containing IgG against the weakly antigenic epitope, and those containing both specific IgGs; these groups made up about 50%, less than 10%, and about 40%, respectively, of all infected sera tested. In other words, IgG against the highly antigenic epitope were detected in more than 90% of H. pylori-infected individuals with high titers. IgG against the weakly antigenic epitope were detected in about 50% of the sera tested; however, the antibody titers were low. The two human epitopes existed independently from the mimic structures of Lewis antigens, which are known to be an important epitope of H. pylori LPS. No significant relationship between the reactivities toward purified LPS of human sera and a panel of anti-Lewis antigen antibodies was found. Moreover, the reactivities of the anti-Lewis antigen antibodies, but not human sera, were sensitive to particular α-l-fucosidases. The human epitopes appeared to be located on O-polysaccharide chains containing endo-β-galactosidase-sensitive galactose residues as the backbone. Data from chemical analyses indicated that all LPS commonly contained galactose, glucosamine, glucose, and fucose (except one rough strain) as probable polysaccharide components, together with typical components of inner core and lipid A. We were not able to distinguish between the differences of antigenicity in humans by on the basis of the chemical composition of the LPS.

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative and microaerophilic bacterium which is recognized as a major cause of chronic gastritis (CG) and peptic ulcer disease (10, 16). Moreover, persistent infection with H. pylori is considered a risk factor for the development of adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma of the stomach (12). Extensive structural and biological studies of H. pylori lipopolysaccharides (LPS) have recently been carried out. The O-polysaccharide regions of these LPS were found to be a major antigenic determinant (17), as have those of other typical bacterial LPS. Aspinall et al. (7, 8) and Monteiro et al. (19) determined the structures of the O polysaccharides of H. pylori LPS and found them to be the same as the Lewis X (Lex) and Lewis Y (Ley) determinants of the human cell surface glycoconjugates. Furthermore, Appelmelk et al. (6) suggested that the mimicry of Lewis antigens by this organism raised titers of autoantibody to Lewis antigens, especially Lex, and might be one of the causative factors of H. pylori-associated type B gastritis via an autoimmune mechanism. On the other hand, we have observed that many H. pylori LPS possess antigenic epitopes, which are dominantly immunogenic in humans, in their polysaccharide regions and these epitopes are unlikely to be immunogenically related to the structures mimicking Lewis antigens (2, 29, 30). In addition, we found low-titer anti-Lewis antigen antibodies in human sera regardless of H. pylori infection status (2). Consistent with our findings, Faller et al. (11) reported that anticanalicular autoantibodies in sera of H. pylori-infected patients are not absorbed from these sera by incubation with Lex- and/or Ley-positive H. pylori cells. Most H. pylori-infected individuals, including patients with gastroduodenal diseases and healthy carriers, have high titers of antibody to the antigenic epitope, so we propose that LPS possessing the antigenic epitope is a strong candidate for an antigen diagnostic of H. pylori infection (4).

To characterize epitopes antigenic in humans with natural infections, we purified LPS from a panel of H. pylori strains isolated from patients with gastroduodenal diseases. The LPS were analyzed immunologically and chemically. We identified two distinct epitopes located on the O polysaccharide of H. pylori LPS which act in humans. We describe the distribution of these two antigenic epitopes among H. pylori clinical isolates and discuss the lack of a discernible relationship between the presence of the human epitopes and either the presence of Lewis antigen-mimicking structures or the chemical composition of the LPS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms and purification of LPS.

H. pylori strains were isolated from biopsy specimens of lesions obtained from patients with CG, gastric ulcer (GU), duodenal ulcer (DU), and gastric cancer (CA) in Sapporo Medical University Hospital (Sapporo, Japan). After three to five laboratory subcultures, these bacteria were grown on brucella broth supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) horse blood at 37°C for 2 to 4 days under microaerophilic conditions by using the GasPak system (BBL, Cockeysville, Md.) without a catalyst. The organisms were collected, washed with phosphate-buffered saline three times, and lyophilized. LPS were extracted from whole cells of H. pylori by the hot-phenol extraction method described by Amano et al. (1) and dialyzed for 4 days at room temperature against three changes of distilled water. The nondialyzable materials were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 3 h, and the precipitates (LPS) were washed twice and lyophilized. The preparation containing less than 3% (wt/wt) proteins and nucleic acids was used for further study. When the contaminants contained more than 3% (wt/wt), the preparation was treated with proteinase K, DNase, and RNase.

Human sera.

Sera from patients with CG, GU, DU, and CA and sera from healthy adult volunteers positive for H. pylori were donated by the hospitals of Sapporo Medical University and the Akita University School of Medicine (Akita, Japan). The H. pylori infection status of each individual was determined with the Determinar H. pylori antibody enzyme immunoassay kit (Kyowa Medics, Tokyo, Japan).

MAbs against Lewis antigens.

Murine monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against Lewis antigens used in this study were as follows: clones 73-30 (anti-Lex immunoglobulin M [IgM]; Seikagaku Corp., Tokyo, Japan), MAB2108 (anti-Lea IgG1; Chemicon, Temecula, Calif.), and BG8, BG6, and BG4 (anti-Ley IgM, anti-Leb IgM, and anti-H1 IgG3, respectively; Signet Laboratories, Dedham, Mass.). KM-93, AG1, and 1H4 (anti-sialyl Lex IgM, anti-asialo GM1 IgM, and anti-sialyl Lea IgG3, respectively) were purchased from Seikagaku Corp.

Electrophoresis and immunoblotting.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotting were performed as described elsewhere (1, 2). Before samples were applied to a gel, purified LPS were dissolved in SDS-PAGE sample buffer at a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml. For screening experiments using 68 H. pylori clinical isolates, proteinase K-treated cells were used as an LPS fraction for immunoblotting as described previously (2, 29). LPS (0.4 μg) were applied to a 12.5% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel and resolved by electrophoresis. The LPS profile on the gel was developed by silver staining according to the method of Hitchcock and Brown (14). Immunoblotting was accomplished as follows. After transfer from the gel to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Nihon Millipore, Yonezawa, Japan), the membrane was incubated with appropriately diluted human sera or murine anti-Lewis antigen MAbs as the primary antibody. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG or anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody (Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark) or alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG(γ) or anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody (BioSource International, Camarillo, Calif.) was used as the second antibody. Bound antibody was detected with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (for peroxidase) or 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate p-toluidine salt and Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (for alkaline phosphatase).

ELISA.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were carried out as previously described (29). Briefly, 50 μl of purified LPS solution (5 μg/ml in 50 mM sodium carbonate buffer [pH 9.6]) was dispensed into each well of a 96-well microtiter plate and incubated at 4°C overnight. After blocking of each well with human serum albumin, serially diluted human sera were added. Bound antibody was detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG(γ) antibody (BioSource) and 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine as the second antibody and substrate, respectively. Reactions were terminated with 1 M phosphoric acid, and the A450 was measured. The maximal serum dilution giving an A450 of 0.2 was expressed as the serum titer.

Glycosidase treatments of LPS.

LPS (0.5 μg) were treated with various glycosidases at 37°C overnight under the following conditions unless otherwise indicated: 2 μU of endo-β-galactosidase derived from Citrobacter freundii (Seikagaku Corp.) in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) at 50°C, 2 μU of lacto-N-biosidase derived from Streptomyces sp. strain 142 (Takara Shuzo, Tokyo, Japan) in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5), 2 μU of α-1/3,4-l-fucosidase derived from Streptomyces sp. strain 142 (Takara Shuzo) in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5), 5 μU of α-l-fucosidase derived from Charonia lampas (Seikagaku Corp.) in 0.1 M sodium citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 4.0) containing 0.5 M NaCl, 1 mU of α-1,2-l-fucosidase derived from an Arthrobacter sp. (Takara Shuzo) in 50 mM sodium borate buffer (pH 8.5), 2 mU of α-l-fucosidase derived from Fusarium oxysporum (Seikagaku Corp.) in 50 mM citrate buffer (pH 4.5), 5 mU of α-glucosidase derived from Bacillus stearothermophilus (Sigma) in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8); 5 mU of β-glucosidase from almonds (Sigma) in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0); 5 mU of α-galactosidase from green coffee beans (Sigma) in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) at 25°C, and 4 μU of β-galactosidase from Streptococcus sp. strain 6646K (Seikagaku Corp.) in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5). After treatment, the mixtures were neutralized with NaOH or HCl and then treated with the SDS-PAGE sample buffer at 100°C for 5 min. The resulting samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as described above.

Absorption of sera with LPS.

Twenty microliters of 10-fold-diluted human sera and 5 μg of LPS were mixed and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The absorbed sera were further diluted and used for immunoblotting as described above.

Chemical analysis.

Neutral sugars, heptose, 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid (KDO), and total phosphorus were assayed by colorimetric methods described by Amano et al. (1). Amino acids and amino compounds were analyzed with an amino acid analyzer after hydrolysis in 4 N HCl at 100°C for 8 h as described by Amano et al. (3). The composition of neutral sugars was analyzed by gas chromatography after acid hydrolysis in 2 N HCl at 100°C for 3 h and conversion to alditol acetates as described by Mizushiri et al. (18). Fatty acids were analyzed by gas chromatography on an FFAP-CB bonded capillary glass column (0.32 mm by 25 m; GL Science Inc., Tokyo, Japan) at 220°C.

RESULTS

Chemical characterization of LPS from H. pylori clinical isolates.

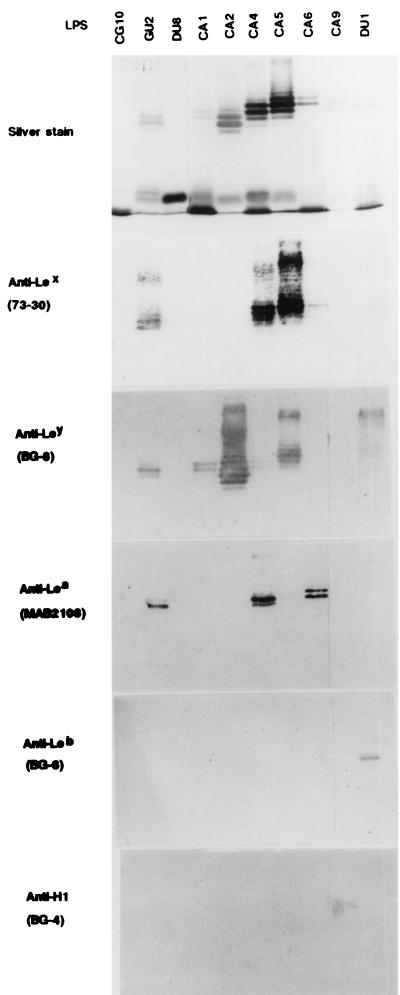

LPS were extracted and purified from H. pylori strains CG10, GU2, DU1, DU8, CA1, CA2, CA4, CA5, CA6, and CA9. The letters CG, GU, DU, and CA indicate that the strains were isolated from patients with CG, GU, DU, and CA, respectively. We selected these strains on the basis of chemotypes (smooth or rough) and variation in antigenicity, as described previously (2, 29, 30). The molecular sizes and microheterogeneity of these LPS were compared on SDS-PAGE gels after silver staining (Fig. 1, top panel). Except for CG10 and DU8 LPS, all preparations showed a series of ladder bands in the high-molecular-size area, which corresponds to O-polysaccharide-carrying LPS, and one or two broad bands in the low-molecular-size area. LPS from strains CG10 and DU8 exhibited only one major band of low molecular size. This indicated that these two strains had a rough phenotype. The electrophoretic patterns of these LPS were the same as the previously reported patterns obtained with proteinase K-treated cells of the corresponding strains (2).

FIG. 1.

LPS phenotypes analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining and reactivities of anti-Lewis antigen MAbs (clone names are in parentheses) by immunoblotting. The MAbs were diluted to 1:200. The H. pylori strains used are listed at the top.

We analyzed the chemical composition of the H. pylori LPS (Tables 1 and 2). All of the purified LPS contained neutral sugars, heptose, phosphate, glucosamine, glucosamine phosphate, and ethanolamine as major components and a small amount of KDO. Glucosamine phosphate, ethanolamine, and some of the glucosamine are likely to be components of lipid A, and heptose and KDO are probably contained in the core oligosaccharide moieties. Acid hydrolysates of these LPS were converted to alditol acetates and analyzed by gas chromatography (Table 2). All contained glucose, galactose, and two kinds of heptose in different proportions. Fucose was present in all except CG10 LPS. Based on the chemical analyses and SDS-PAGE patterns (Fig. 1), it appeared that the O-polysaccharide moieties of these LPS consisted of fucose, glucose, galactose, and glucosamine. Strains of CG10 and DU8 possessed rough or semirough LPS and no O-polysaccharide moiety, so the glucose, galactose, and glucosamine (and fucose in DU8) were apparently contained in the core oligosaccharide moiety and/or one repeating unit in these LPS. LPS from CG10 lacked fucose, and the apparent molecular size of CG10 LPS was smaller than that of DU8 LPS (Fig. 1). The results suggested that CG10 LPS had a severer defect in its core region than did DU8 LPS and that the defect included a fucose residue(s). We also analyzed the fatty acid composition of the purified LPS by gas chromatography after acid hydrolysis (data not shown). All contained β-hydroxyoctadecanoic acid (βOHC18), β-hydroxyhexadecanoic acid (βOHC16), and octadecanoic acid (C18) in an approximate ratio of 2:1:0.6 to 0.9. In these LPS, dodecanoic acid (C12), tetradecanoic acid (C14), and hexadecanoic acid (C16) were contained in ratios lower than 0.08 relative to βOHC18.

TABLE 1.

Chemical composition of LPS from H. pylori

| Strain from which LPS was obtained | Concn of component (nmol/mg)a

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral sugars | Heptose | KDO | Total phosphate | Glucosamine | Glucosamine phosphate | Ethanolamine | |

| GU2 | 1,302 (5.0) | 261 (1) | 26 (0.1) | 224 (0.9) | 514 (2.0) | 59 (0.2) | 28 (0.1) |

| DU1 | 1,465 (6.6) | 223 (1) | 40 (0.2) | 638 (2.9) | 918 (4.1) | 108 (0.5) | 128 (0.6) |

| CA1 | 1,440 (4.7) | 307 (1) | 68 (0.2) | 372 (1.2) | 550 (1.8) | 198 (0.6) | 32 (0.1) |

| CA2 | 1,460 (9.1) | 160 (1) | 22 (0.1) | 1,019 (6.4) | 488 (3.1) | 21 (0.1) | 38 (0.2) |

| CA4 | 1,540 (8.5) | 182 (1) | 8 (0.0) | 333 (1.8) | 917 (5.0) | 69 (0.4) | 154 (0.8) |

| CA5 | 1,498 (8.4) | 178 (1) | 10 (0.1) | 473 (2.7) | 1,206 (6.8) | 68 (0.4) | 102 (0.6) |

| CA6 | 1,470 (8.1) | 181 (1) | 15 (0.1) | 900 (5.0) | 485 (2.7) | 51 (0.3) | 87 (0.5) |

| CA9 | 1,874 (7.2) | 262 (1) | 5 (0.0) | 1,715 (6.5) | 785 (3.0) | 29 (0.1) | 55 (0.2) |

| DU8 | 1,063 (3.8) | 277 (1) | 17 (0.1) | 378 (1.4) | 409 (1.5) | 67 (0.2) | 126 (0.5) |

| CG10 | 797 (3.6) | 221 (1) | 45 (0.2) | 402 (1.8) | 266 (1.2) | 56 (0.3) | 98 (0.4) |

Values in parentheses are molar ratios relative to heptose.

TABLE 2.

Analysis of alditol acetate derivatives of LPS from H. pylori

| Retention timea | Sugarb | % Sugar derivative in total derivatives of LPS from strain:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GU2 | DU1 | CA1 | CA2 | CA4 | CA5 | CA6 | CA9 | DU8 | CG10 | ||

| 0.63 | Fucose | 8 | 11 | 3 | 18 | 9 | 13 | 5 | 12 | 10 | 0 |

| 1.00 | Glucose | 20 | 14 | 20 | 26 | 16 | 18 | 29 | 41 | 28 | 21 |

| 1.02 | Galactose | 30 | 38 | 25 | 39 | 43 | 51 | 31 | 34 | 17 | 26 |

| 1.59 | dd-Heptose | 19 | 18 | 16 | 11 | 19 | 11 | 18 | 8 | 26 | 21 |

| 1.72 | dl-Heptose | 24 | 19 | 36 | 6 | 14 | 7 | 17 | 5 | 19 | 31 |

Retention times are relative to that of glucose.

dd-Heptose, d-glycero-d-manno-heptose; dl-heptose, d-glycero-l-manno-heptose.

The binding of anti-Lewis antigen MAbs to all of the LPS was tested by immunoblotting. Except for LPS from the rough strains CG10 and DU8, H. pylori LPS reacted with at least one anti-Lewis antigen MAb (Fig. 1 and Table 3). GU2 LPS reacted with MAbs against Lex, Ley, and Lea, and DU1 LPS reacted with MAbs against Ley and Leb. CA1 and CA2 LPS reacted with anti-Ley MAb, and CA4 LPS reacted with anti-Lex and Lea MAbs. CA5 LPS reacted with anti-Lex and anti-Ley MAbs. CA6 and CA9 LPS reacted with MAbs against Lea and H-type 1 antigen (Led), respectively. We also tested MAbs against other biologically active carbohydrate antigens for their reactivities to H. pylori LPS. MAbs against sialyl Lex, asialo GM1, and sialyl Lea did not react with any of the purified H. pylori LPS.

TABLE 3.

Reactivities of H. pylori LPS with sera from humans with H. pylori infection and MAbs against Lewis antigens

| Strain from which LPS was obtained | Reactivity with human sera

|

Reactivity with anti-Lewis antigen MAbs by IB

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A

|

Type B

|

Type C

|

Lex | Ley | Lea | Leb | H1 (Led) | |||||

| IBa | ELISAb | IB | ELISA | IB | ELISA

|

|||||||

| Serum 1 | Serum 2 | |||||||||||

| GU2 | + | 51,200 | − | 1,600 | + | 102,400 | 51,200 | + | + | + | − | − |

| DU1 | + | 51,200 | − | 1,600 | + | 102,400 | 51,200 | − | + | − | + | − |

| CA1 | + | 12,800 | − | 800 | + | 1,600 | 3,200 | − | + | − | − | − |

| CA2 | − | 3,200 | + | 12,800 | + | 12,800 | 12,800 | − | + | − | − | − |

| CA4 | − | 3,200 | + | 6,400 | + | 6,400 | 3,200 | + | − | + | − | − |

| CA5 | − | 1,600 | + | 12,800 | + | 12,800 | 6,400 | + | + | − | − | − |

| CA6 | − | 1,600 | + | 12,800 | + | 6,400 | 3,200 | − | − | + | − | − |

| CA9 | − | 1,600 | + | 12,800 | + | 12,800 | 6,400 | − | − | − | − | + |

| CG10 | − | 1,600 | − | 400 | − | 1,600 | 800 | − | − | − | − | − |

| DU8 | − | 1,600 | − | 400 | − | 1,600 | 800 | − | − | − | − | − |

IB, immunoblotting.

The maximal serum dilution giving an A450 of 0.2 in ELISA was expressed as the serum titer. Type A serum no. 2 (from a CA patient), type B serum no. 2 (from a healthy carrier), and type C serum no. 1 (from a CG patient) and 2 (from a CA patient) were used for the assays whose results are shown from the left to the right, respectively.

Reactivity of human sera to H. pylori LPS.

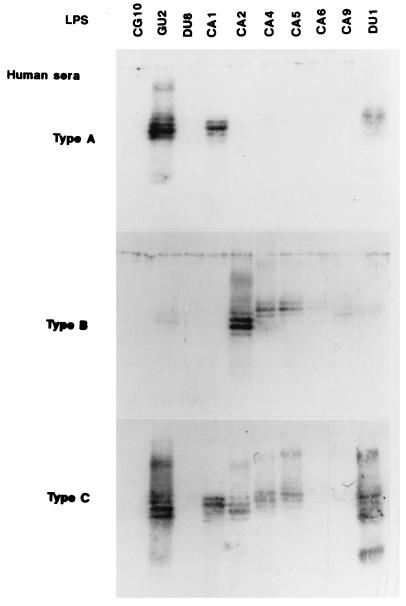

We examined the reactivities of sera from humans with H. pylori infection to the purified LPS by immunoblot analysis. H. pylori-positive sera could be classified into three groups on the basis of immunoblot reactivity to the polysaccharide region of LPS; we have termed these groups types A, B, and C (Fig. 2 and Tables 3 and 4). Type A sera reacted to the polysaccharides of GU2, DU1, and CA1 LPS only. Type B sera showed reactivities complementary to those of type A sera, binding specifically to the polysaccharides of CA2, CA4, CA5, CA6, and CA9 LPS. Type C sera reacted to all smooth LPS. Type A sera appeared to be specific for the highly antigenic epitope in humans, which we proposed in previous reports (29, 30), since GU2 and DU1 LPS are typically highly antigenic while the other LPS are relatively weakly antigenic. However, CA1 LPS was characterized as weakly antigenic in our previous studies (29, 30). CA1 LPS appeared to carry the highly antigenic epitope but at a level much lower than those carried by GU2 and DU1 LPS. ELISA results (Table 3) indicated that type A sera and type C sera showed very low avidity for CA1 LPS relative to that for GU2 and DU1 LPS. Since CG10 and DU8 are rough strains, i.e., they lack the antigenic polysaccharides, their LPS were not recognized by any sera in immunoblot analysis. The positive bindings in ELISA to these rough LPS were attributable to antibody to core and/or lipid A epitopes.

FIG. 2.

Reactivities of three types of H. pylori-positive human sera to H. pylori LPS by immunoblotting. Strains used are listed at the top. Human sera (type A no. 2 [from a CA patient], type B no. 2 [from a healthy carrier], and type C no. 2 [from a GU patient]) were diluted to 1:200.

TABLE 4.

Classification of H. pylori-positive human sera by reactivity to LPS possessing the highly antigenic epitope and the weakly antigenic epitope

| Subject group | No. of seraa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Type A | Type B | Type C | Nontypeable | |

| Patients with gastroduodenal diseases | 29 | 15 | 2 | 11 | 1 |

| CG | 10 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| GU | 5 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| DU | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CA | 10 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Healthy adults with infection | 31 | 16 | 2 | 13 | 0 |

| Total | 60 | 31 (52%) | 4 (7%) | 24 (40%) | 1 (2%) |

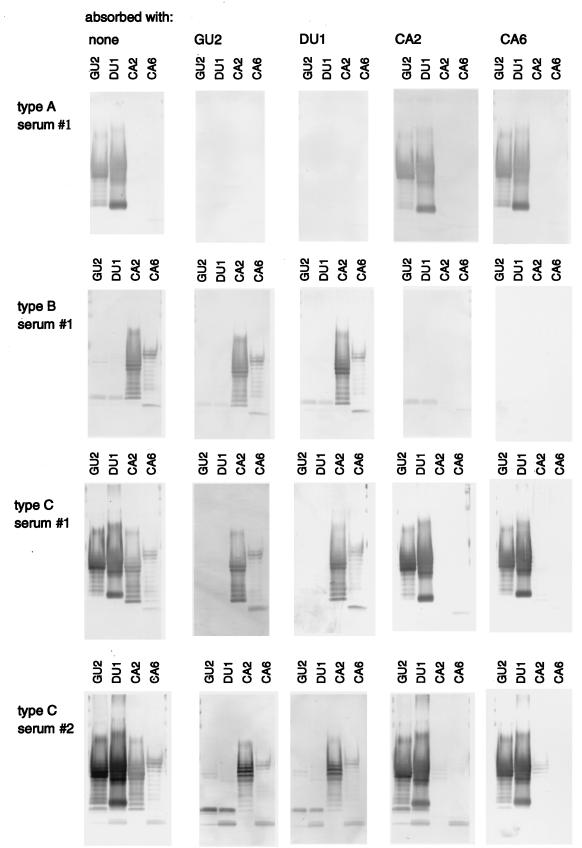

The reactivities of type A and B sera were complementary, and type C sera showed both reactivities (Table 3). At least two distinct epitopes, type A specific and type B specific, appeared to be distributed among H. pylori strains. This raised the question of whether type C sera contained antibodies to both epitopes or antibodies to a distinct common epitope(s). We therefore carried out absorption analysis of each serum type (Fig. 3). The reactivity of type A sera to GU2 and DU1 LPS was completely inhibited by absorption with either GU2 or DU1 LPS but not by CA2 or CA6 LPS. Type B sera reacted with CA2 and CA6 LPS, and this binding was completely inhibited by either CA2 or CA6 LPS but not by GU2 or DU1 LPS. Type C sera reacted strongly to GU2 and DU1 LPS and weakly to CA2 and CA6 LPS. The reactivity to GU2 and DU1 LPS was inhibited by GU2 or DU1 LPS but not by CA2 or CA6 LPS. In contrast, the reactivity to CA2 and CA6 LPS was inhibited only by either CA2 or CA6 LPS. These results indicated that H. pylori LPS carry two distinct epitopes, one of which is highly antigenic and one of which is weakly antigenic. Strains GU2 and DU1 carry the highly antigenic epitope, while strains CA2 and CA6 carry the weakly antigenic epitope. Type A and type B sera contained antibodies against the highly and weakly antigenic epitopes, respectively. Type C sera contained high-titer IgG antibodies against the highly antigenic epitope and low-titer IgG antibodies against the weakly antigenic epitope (Table 3 and Fig. 3). H. pylori-positive human sera donated from 29 patients with gastroduodenal diseases and 31 healthy adults were classified according to these categories (Table 4). Type A sera represented about 50%, type C represented about 40%, and type B represented less than 10% of the total. In other words, more than 90% of H. pylori-positive individuals had antibodies against the highly antigenic epitope, and about 50% had antibodies against the weakly antigenic epitope. The relative proportions of each serum type were not significantly different for patients with gastroduodenal diseases and healthy adults.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot analysis with human sera absorbed with H. pylori LPS. Each serum sample (10-fold diluted) was incubated with LPS (5 μg per 20 μl) derived from the H. pylori strains listed at the top. The absorbed serum was diluted to 1:250 and applied to immunoblots of LPS derived from strains GU2, DU1, CA2 and CA6 as indicated. The human sera used were type A no. 1 (from a DU patient), type B no. 1 (from a CA patient), type C no. 1 (from a CG patient), and type C no. 2 (from a GU patient).

Typing of H. pylori clinical isolates by reactivity of human sera to their LPS.

We examined the distribution of the human epitopes described above among 68 clinical isolates of H. pylori using typical type A serum and type B human serum in immunoblot analyses (Table 5). H. pylori smooth strains carried either one epitope or the other in their LPS. We found neither strains possessing both epitopes nor strains possessing neither epitope. We therefore propose that H. pylori strains may be classified into three types: smooth strains carrying the highly antigenic epitope (about 50%), smooth strains carrying the weakly antigenic epitope (about 45%), and rough strains. The strains derived from CG patients tended to carry predominantly the highly antigenic epitope, in contrast with strains from other sources, such as DU and CA patients. Furthermore, we did not find any relationship between the presence of the two epitopes and the presence of Lewis antigens (30) (Table 3 and data not shown).

TABLE 5.

Typing of H. pylori clinical isolates by reactivities of human sera to their LPS

| Patient group (no. of H. pylori strains) | No. of strains with LPS containing:

|

Rough LPS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highly antigenic epitope (type A serum positive) | Weakly antigenic epitope (type B serum positive) | ||

| CG (19) | 15 | 4 | 0 |

| GU (18) | 8 | 10 | 0 |

| DU (9) | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| CA | |||

| Isolates from tumor site (10) | 3 | 6 | 1 |

| Isolates from nontumor site (12) | 5 | 7 | 0 |

| Total (68) | 35 | 31 | 2 |

Characterization of two human epitopes in H. pylori LPS.

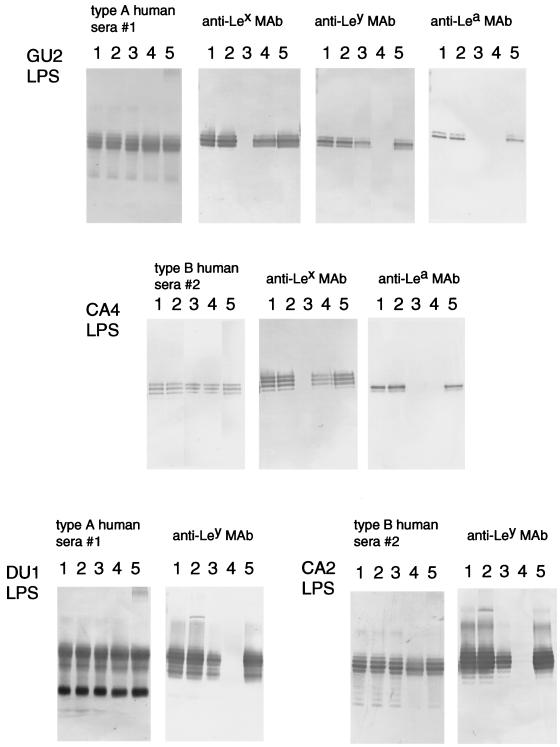

We examined the localization of these epitopes on the O polysaccharides by treatment with various glycosidases. First, we treated LPS with various exoglycosidases. We found that some α-l-fucosidases (Streptomyces α-1,3/4-l-fucosidase or C. lampas α-l-fucosidase) significantly reduced the binding of anti-Lewis antigen MAbs to LPS but did not alter the binding of any type of human sera (Fig. 4). However, the bindings of any anti-Lewis antigen MAbs and any type of human sera were not altered by treatment with other exoglycosidases tested. The binding of an anti-Lex MAb was completely abolished by Streptomyces α-1,3/4-l-fucosidase and reduced by C. lampas α-l-fucosidase. In contrast, the binding of the anti-Ley MAb was more easily abolished by the C. lampas α-l-fucosidase than by the Streptomyces α-1,3/4-l-fucosidase. The preferential sensitivity of the binding of the anti-Ley MAb to C. lampas α-l-fucosidase may be explained by the observation that this enzyme hydrolyzes terminal 1,2-, 1,4-, and 1,3-linked α-l-fucosyl residues; in particular, 1,2-linked fucosyl residues can be split directly from glycolipids and glycoproteins by C. lampas α-l-fucosidase (13, 15). The binding of an anti-Lea MAb was abolished by either Streptomyces or C. lampas α-l-fucosidase but not by other α-l-fucosidases tested.

FIG. 4.

Reactivities of anti-Lewis antigen MAbs and human sera to H. pylori LPS derived from strains GU2, CA4, DU1, and CA2 after treatment with various α-l-fucosidases by immunoblot analysis. Lane 1, no treatment; lane 2, α-1,2-l-fucosidase (Arthrobacter sp.); lane 3, α-1,3/4-l-fucosidase (Streptomyces sp. strain 142); lane 4, α-l-fucosidase (C. lampas); lane 5, α-l-fucosidase (F. oxysporum). The MAbs and sera used are indicated at the top of each panel. The human sera used were type A no. 1 (from a DU patient) and type B no. 2 (from a healthy carrier). Human sera and the anti-Lewis antigen MAbs were diluted to 1:1,000 and 1:200, respectively.

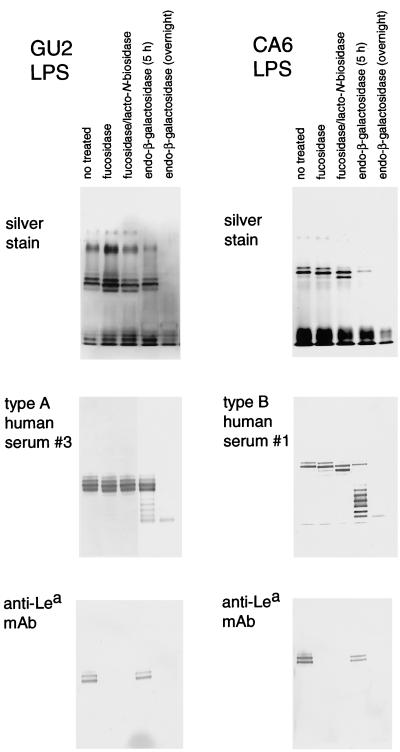

Lea-positive LPS from GU2 (highly antigenic type) and CA6 (weakly antigenic type) were treated with α-1,3/4-l-fucosidase and lacto-N-biosidase (Fig. 5, lanes 2 and 3). The molecular size of the polysaccharide-carrying high-molecular-weight CA6 LPS was clearly reduced, probably by an amount corresponding to one repeating unit; however, the reactivities of human sera with treated CA6 LPS were not altered. In the case of GU2, Lea-capping LPS were a minor population compared with Lex-capping and Ley-capping LPS in the preparation (data not shown), so the reduction in molecular size that was apparent in CA6 LPS upon α-l-fucosidase/lacto-N-biosidase treatment was not clearly observed in GU2 LPS. These results indicate that the structures which mimic of the Lewis antigens and bind to anti-Lewis antigen MAbs are located on the nonreducing terminal portion of the polysaccharide chain, whereas the distinct human epitopes identified in this study are located elsewhere.

FIG. 5.

SDS-PAGE with silver staining and immunoblot analysis of H. pylori LPS derived from strains GU2 and CA6 after treatment with glycosidases as indicated. The fucosidase used was α-1,3/4-l-fucosidase (Streptomyces sp. strain 142). Immunoblotting was carried out with human sera (type A no. 3 [from a DU patient] and type B no. 1 [from a CA patient]) and anti-Lea MAb (MAB2108) diluted 1,000-fold.

Both the highly antigenic epitope and the weakly antigenic epitope of H. pylori LPS were found to be sensitive to endo-β-galactosidase (Fig. 5, lane 4 and 5). Extensive treatment with this enzyme led to removal of polysaccharide chain (detected by silver staining) and abolition of the binding of both human sera (type A and B) and the anti-Lewis antigen MAbs. On the other hand, partial treatment produced a series of degraded ladder bands (Fig. 5, lane 4). This is consistent with reports that H. pylori LPS commonly contains repeating lactosamine structures with β-galactose residues forming the backbone chain (7–9, 19, 20). The results indicated that both antigenic human epitopes were located on a polysaccharide chain with lactosamine repeats as the backbone.

DISCUSSION

The O-polysaccharide region of LPS is commonly used for typing gram-negative bacteria into groups, known as O serotypes, because of its high and specific antigenicity, which is characteristic of the strains belonging to each serotype. In the case of H. pylori LPS, the properties of the epitopes of the polysaccharide region seem to be complex. Mills et al. (17) proposed a tentative serotyping scheme for H. pylori and pointed out that H. pylori LPS carry both common and strain-specific epitopes. On the other hand, it has been demonstrated chemically and immunologically that the O-polysaccharide portions of H. pylori contain structures which mimic the Lewis blood group antigens (2, 6–9, 19, 20, 24, 25). Recently, Monteiro et al. (19, 20) reported that O polysaccharides of H. pylori LPS express several structures as the nonreducing terminal end, including the Lex, Ley, Lea, Lec, and Led antigens. They also reported a difference between terminal structures and repeating units of the O polysaccharides of LPS from some H. pylori strains. Furthermore, other additional structural units, such as glucan and dd-heptan, are also found in some strains. These results suggest that the O polysaccharides carry multiple epitopes. Among them, the structures mimicking the Lewis antigens have been regarded as important antigenic epitopes of H. pylori LPS (6).

Our earlier studies, however, suggest that a highly antigenic epitope reacting with human sera is unlikely to be immunogenically related to the structures mimicking the Lewis antigens (30). At that time, we examined the distribution of the highly antigenic epitope quantitatively, using ELISA to calculate the mean values for binding of some high-titer human sera to LPS. The aim of the present study was to analyze the nature and distribution of the antigenic epitope(s) which acts during natural H. pylori infection in humans, for which purpose immunoblotting is more suitable than ELISA, because ELISA measures antibody against the whole LPS molecules, including epitopes present in the O polysaccharide, core oligosaccharide, and lipid A regions. Low-level expression of a particular epitope is therefore difficult to distinguish from antibody to other epitopes, such as core oligosaccharide and lipid A. To obtain more precise results, we carefully selected human sera which reacted specifically with each epitope and analyzed H. pylori LPS from various strains by a qualitative approach, namely, immunoblotting.

We have identified two distinct human epitopes, termed the highly antigenic epitope and the weakly antigenic epitope. The highly antigenic epitope is the same as previously identified (29, 30), but we have now identified a second, weakly antigenic epitope by using specific sera containing IgG antibodies against H. pylori LPS which did not recognize the highly antigenic epitope. Interestingly, expression of these epitopes seemed to be mutually exclusive: no strains which expressed both epitopes were identified, but all smooth strains expressed one or the other. So H. pylori strains can be classified by LPS types: smooth LPS carrying the highly antigenic epitope (51% of 68 clinical isolates), smooth LPS carrying the weakly antigenic epitope (46%), and rough LPS (3%). Strains derived from CG patients have a tendency to express the highly antigenic epitope more frequently than strains obtained from other clinical sources. In a previous report (29), we mentioned that strains derived from tumor sites of CA patients were predominantly weakly antigenic as determined by a quantitative method (ELISA). The present study combined qualitative (immunoblotting) and quantitative (ELISA) methods (Table 2) and indicated that the strains showing low antigenicity are divided into two categories. Most weakly antigenic strains, such as CA series strains (except CA1), expressed the weakly antigenic epitope. However, there also exist strains, such as CA1, which express extremely low levels of the highly antigenic epitope. These findings suggest that there is some correlation between antigenicity and the clinical source of H. pylori strains. To summarize, strains expressing LPS carrying the highly antigenic epitope tended to be frequently found in CG patients, whereas strains from CA patients, especially tumor site isolates, more commonly showed low antigenicity.

We confirmed directly that the structures which mimic the Lewis antigens exist independently of the two human epitopes we have identified. Appropriate α-1,3/4-l-fucosidase treatment of purified LPS abolished binding to anti-Lewis antigen MAbs but did not alter the binding activities of human sera. In the case of Lea-positive LPS, we succeeded in removing the nonreducing terminal structure containing the Lea antigen mimic by treatment with α-l-fucosidase and lacto-N-biosidase. The removal of the nonreducing terminal structure also did not alter any binding activities of human sera. The chemical composition of LPS used in this study (Table 1 and 2), in light of a number of structural studies (7–9, 19, 20), indicated that these O polysaccharides contained lactosamine repeats as the backbone chain. This was confirmed by partial endo-β-galactosidase treatment (Fig. 5, lane 4), which resulted in the appearance of many degraded ladder bands and indicated that endo-β-galactosidase-sensitive sites were located in a repetitive manner in the O polysaccharide. Furthermore, both human epitopes appeared to be located in the O-polysaccharide region, because human sera recognized the degraded bands produced by partial endo-β-galactosidase treatment and this binding was abolished by extensive endo-β-galactosidase treatment.

Many sera from humans with H. pylori infections contained relatively high (above 5,000-fold) titers of IgG to the epitopes of H. pylori LPS. These epitopes appeared to be specific for H. pylori, because H. pylori-negative sera did not react with the epitopes and most of the positive sera did not cross-react with other bacterial LPS tested (4). More than 90% of the H. pylori-positive sera containing high-titer antibody recognized the highly antigenic epitope, so members of our group proposed that LPS carrying the highly antigenic epitope might be useful as an antigen for diagnosis of H. pylori infection (4). About 50% of H. pylori-positive sera contained antibodies against the weakly antigenic epitope; however, we found only a few sera containing antibodies specific for only the weakly antigenic epitope. Interestingly, we did not find any H. pylori strains possessing both epitopes, so individuals having antibodies against both epitopes appear to have been exposed to H. pylori cells with two different phenotypes for the antigenic epitopes of LPS. Exposure to two different phenotypes may occur by infection with multiple H. pylori strains or by phenotype change of one strain during infection. Recently, phenotypic diversity and phase variation were found to occur in LPS (5, 28); they can be explained to result from changes in the activities of biosynthetic enzymes, such as glycosyltransferases (5, 27). However, these reports focused on the Lewis antigen structures. It remains to be determined whether the human epitopes we have identified are variable in the course of a single infection.

We also characterized the chemical composition and reactivities with anti-Lewis antigen MAbs of the LPS we purified, but we did not find any significant difference in these characteristics between LPS carrying the highly antigenic epitope and LPS carrying the weakly antigenic epitope. LPS of both types contained galactose, glucosamine, fucose, and glucose, together with typical inner core and lipid A components, such as heptose, KDO, glucosamine phosphate, and ethanolamine. In addition, we analyzed the fatty acids of lipid A components. The H. pylori lipid A structure differs from that typical for lipid A from gram-negative bacteria, such as enterobacteria (21, 26), and its biological activities, such as mitogenicity, pyrogenicity, toxicity (22), and macrophage activation (23), are extremely low or nonexistent. So we are interested in differences in chemistry and/or biological activities between the LPS carrying the highly and the weakly antigenic epitopes. However, all of the H. pylori LPS contained three fatty acids, βOHC18, βOHC16, and C18, in a molar ratio of about 2:1:1. Moran et al. (21) reported that the major lipid A isolated from smooth- and rough-form LPS consisted of βOHC18, βOHC16, and C18 in a molar ratio of 2:1:1, besides diglucosamine phosphate as the backbone. They further indicated the presence of lipid A that contained C12 or C14 fatty acid in a small amount, in addition to the major lipid A described above. In contrast, Suda et al. (26) reported a slightly different H. pylori lipid A that was composed of βOHC18 and C18 in a molar ratio of 2:1. Our data in this study are consistent with the lipid A structure proposed by Moran et al. (21).

To further clarify the structures of the two epitopes we have identified, we have been trying to prepare specific mouse MAbs and rabbit antisera to these epitopes. However, we have obtained only antibodies against epitopes mimicking the Lewis antigens, and none which recognize the intended epitopes, by conventional immunization protocols using cells or purified LPS as an antigen with Freund's complete and incomplete adjuvants (K. Amano and S. Yokota, unpublished results). The epitopes in humans may act only during natural H. pylori infection in humans. Our next goal is to characterize the chemical structures of the highly and weakly antigenic human epitopes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amano K, Fujita M, Suto T. Chemical properties of lipopolysaccharides from spotted fever group rickettsiae and their common antigenicity with lipopolysaccharides from Proteus species. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4350–4355. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4350-4355.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amano K, Hayashi S, Kubota T, Fujii N, Yokota S. Reactivities of Lewis antigen monoclonal antibodies with the lipopolysaccharides of Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from patients with gastroduodenal diseases in Japan. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:540–544. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.5.540-544.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amano K, Williams J C, Missler S R, Reinhold V N. Structure and biological relationships of Coxiella burnetti lipopolysaccharides. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4740–4747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amano K, Yokota S, Ishioka T, Hayashi S, Kubota T, Fujii N. Utilization of proteinase K-treated cells as lipopolysaccharide antigens for the serodiagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infections. Microbiol Immunol. 1998;42:509–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1998.tb02317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appelmelk B J, Shiberu B, Trinks C, Tapsi N, Zheng P Y, Verboom T, Maaskant J, Hokke C H, Schiphorst W E C M, Blanchard D, Simoons-Smit I M, van den Eijnden D H, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C M J E. Phase variation in Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1998;66:70–76. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.70-76.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appelmelk B J, Simoons-Smit I, Negrini R, Moran A P, Aspinall G O, Forte J G, de Vries T, Quan H, Verboom T, Maaskant J J, Ghiara P, Kuipers E J, Bloemena E, Tadema T M, Townsend R R, Tyagarajan K, Crothers J M, Jr, Monterio M A, Savio A, de Graaff J. Potential role of molecular mimicry between Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide and host Lewis blood group antigens in autoimmunity. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2031–2040. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2031-2040.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aspinall G O, Monteiro M A. Lipopolysaccharides of Helicobacter pylori strains P466 and MO19: structures of the O antigen and core oligosaccharide regions. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2498–2504. doi: 10.1021/bi951853k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aspinall G O, Monteiro M A, Pang H, Walsh E J, Moran A P. Lipopolysaccharide of the Helicobacter pylori type strain NCTC 11637 (ATCC 43504): structure of the O antigen chain and core oligosaccharide regions. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2489–2497. doi: 10.1021/bi951852s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aspinall G O, Monteiro M A, Shaver R T, Kurjanczyk L A, Penner J L. Lipopolysaccharides of Helicobacter pylori serogroups O:3 and O:6. Structures of a class of lipopolysaccharides with reference to the location of oligomeric units of d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose residues. Eur J Biochem. 1997;248:592–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cover T L, Blaser M J. Helicobacter pylori infection, a paradigm for chronic mucosal inflammation: pathogenesis and implications for eradication and prevention. Adv Intern Med. 1996;41:85–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faller G, Steininger H, Appelmelk B, Kirchner T. Evidence of novel pathogenic pathways for the formation of antigastric autoantibodies in Helicobacter pylori gastritis. J Clin Pathol. 1998;51:244–245. doi: 10.1136/jcp.51.3.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forman D, Newell D G, Fullerton F, Yarnell J W, Stacey A R, Wald N, Sitas F. Association between infection with Helicobacter pylori and risk of gastric cancer: evidence from a prospective investigation. Br Med J. 1991;302:1302–1305. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6788.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuda M N, Hakomori S. Structures of branched blood group A-active glycosphingolipids in human erythrocytes and polymorphism of A- and H-glycolipids in A1 and A2 subgroups. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:446–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hitchcock P, Brown T M. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:269–277. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.269-277.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iijima Y, Muramatsu T, Egami F. Purification of α-l-fucosidase from the liver of a marine gastropod, Turbo cornutus, and its action on blood group substances. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1971;145:50–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(71)90008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall B J, Warren J R. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;i:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mills S D, Kurjanczyk L A, Penner J L. Antigenicity of Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharides. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:3175–3180. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.12.3175-3180.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizushiri S, Amano K, Fuji S, Fukushi K, Watanabe M. Chemical characterization of lipopolysaccharides from Proteus strains used in Weil-Felix test. Microbiol Immunol. 1990;34:121–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1990.tb00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monteiro M A, Chan K H N, Rasko D A, Taylor D E, Zheng P Y, Appelmelk B J, Wirth H-P, Yang M, Blaser M J, Hynes S O, Moran A P, Perry M B. Simultaneous expression of type 1 and type 2 Lewis blood group antigens by Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharides. Molecular mimicry between H. pylori lipopolysaccharides and human gastric epithelial cell surface glycoforms. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11533–11543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monteiro M A, Rasko D, Taylor D E, Perry M B. Glucosylated N-acetyllactosamine O-antigen chain in the lipopolysaccharide from Helicobacter pylori strain UA861. Glycobiology. 1998;8:107–112. doi: 10.1093/glycob/8.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moran A P, Lindner B, Walsh E J. Structural characterization of the lipid A component of Helicobacter pylori rough- and smooth-form lipopolysaccharides. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6453–6463. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6453-6463.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muotiala A, Helander I M, Pyhälä L, Kosunen T U, Moran A P. Low biological activity of Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1714–1716. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1714-1716.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perez-Perez G I, Shepherd V L, Morrow J D, Blaser M J. Activation of human THP-1 cells and rat bone marrow-derived macrophages by Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1183–1187. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1183-1187.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherburne R, Taylor D E. Helicobacter pylori expresses a complex surface carbohydrate, Lewis X. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4564–4568. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4564-4568.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simoons-Smit I M, Appelmelk B J, Verboom T, Negrini R, Penner J L, Aspinall G O, Moran A P, Fei S F, Bi-Shan S, Rudnica W, Savio A, de Graaff J. Typing of Helicobacter pylori with monoclonal antibodies against Lewis antigens in lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2196–2200. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2196-2200.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suda Y, Ogawa T, Kashihara W, Oikawa M, Shimoyama T, Hayashi T, Tamura T, Kusumoto S. Chemical structure of lipid A from Helicobacter pylori strain 206-1 lipopolysaccharide. J Biochem. 1997;121:1129–1133. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang G, Rasko D A, Sherburne R, Taylor D E. Molecular genetic basis for the variable expression of Lewis Y antigen in Helicobacter pylori: analysis of the α (1,2) fucosyltransferase gene. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1265–1274. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wirth H-P, Yang M, Peek R M, Jr, Höök-Nikanne J, Fried M, Blaser M J. Phenotypic diversity in Lewis expression of Helicobacter pylori isolates from the same host. J Lab Clin Med. 1999;133:488–500. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(99)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yokota S, Amano K, Hayashi S, Fujii N. Low antigenicity of the polysaccharide region of Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharides derived from tumors of patients with gastric cancer. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3509–3512. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3509-3512.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokota S, Amano K, Hayashi S, Kubota T, Fujii N, Yokochi T. Human antibody response to Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide: presence of an immunodominant epitope in the polysaccharide chain of lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3006–3011. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.3006-3011.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]