Abstract

Streptomyces griseus strains isolated from indoor dust have been shown to synthesize valinomycin. In this report, we show that human peripheral blood lymphocytes treated with small doses (30 ng ml−1) of pure valinomycin or high-pressure liquid chromatography-pure valinomycin from S. griseus quickly show mitochondrial swelling and reduced NK cell activity. Larger doses (>100 ng/ml−1) induced NK cell apoptosis within 2 days. Within 2 h, the toxin at 100 ng ml−1 dramatically inhibited interleukin-15 (IL-15)- and IL-18-induced granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production by NK cells. However, IFN-γ production induced by a combination of IL-15 and IL-18 was somewhat less sensitive to valinomycin, suggesting a protective effect of the cytokine combination against valinomycin. Thus, valinomycin in very small doses may profoundly alter the immune response by reducing NK cell cytotoxicity and cytokine production.

Human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) contain 5 to 20% NK cells, which can lyse certain tumor and normal cell lines without prior immunization. Upon activation, NK cells secrete cytokines such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor alpha, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (7, 15, 24). NK cells are thought to represent the first line defense in the immune system since they kill abnormal cells and simultaneously secrete cytokines to activate the other arms of the immune response.

Interleukin-15 (IL-15) and IL-18 are cytokines which regulate NK cell function. IL-15 is required for NK cell maturation, and IL-18 is essential for NK cell activity (16, 29). Valinomycin is an ionophore which is a cyclic-polypeptide-like dodecadepsipeptide whose folded conformation forms an inner cavity that can accommodate K+ but not other ions. For that reason, valinomycin is involved in a selective transport of K+ ions across the inner membrane of mitochondria (11, 12). In rat ascites hepatoma cells, valinomycin induces apoptosis by disrupting the membrane potential of mitochondria and, when used at higher concentrations, causes apoptosis in many mammalian cell types (1, 10, 14, 21, 34). Andersson et al. (3) isolated Streptomyces griseus strains that produce valinomycin from an indoor environment. In schools and children's day care centers with dampness damage, such Streptomyces strains were frequently encountered (26).

Here we report that pure commercial valinomycin and high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC)-pure valinomycin from S. griseus inhibit human NK activity and cytokine production and induce apoptosis of NK cells at doses 10 to 500 times lower than those previously used. Thus, a toxin derived from bacteria that are abundant in the environment has the potential to cause immune suppression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell isolation and culture.

Leukocyte-rich buffy coats were obtained from healthy blood donors (Finnish Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service, Helsinki, Finland). PBL were isolated by Ficoll-Paque (Pharmacia Biotechnology, Uppsala, Sweden) density centrifugation. PBL were collected and further purified by being passed through nylon wool columns in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with glutamine, streptomycin-penicillin, and 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Bioclear). K562 cells (17) were cultured in 10% FBS–RPMI 1640 medium at 37°C in a humidified air atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Enrichment of NK and T cells.

NK cells were isolated by two-step density gradient Percoll (Pharmacia) centrifugation in 10% FBS–RPMI 1640 medium. T cells were depleted from the NK cell fraction by treatment with anti-CD3 antibody (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.), followed by adsorption with immunomagnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway). Alternatively, T cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation and NK cells were removed by anti-CD16 antibody treatment and adsorption with immunomagnetic beads. After density gradient purification in an NK cell gradient, there were 40 to 70% CD56+ cells, and after adsorption with immunomagnetic beads, >80% of all cells were CD56+ cells. The results were analyzed by using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Cytotoxicity assay.

PBL effector cells (2 × 106 ml−1) were preincubated in 96-well plates with bacterial toxins. K562 target cells (1.0 × 106 ml−1; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) were labeled with 50 μCi of sodium 51Cr (Radiochemical Centre, Amersham, United Kingdom). A 100-μl volume of target cells (1.0 × 104 ml−1) was added with 100 μl of various numbers of preincubated effector cells to produce effector/target ratios of 50:1, 25:1, and 12.5:1. After 3 h of incubation at 37°C, 100 μl of supernatant from each well was counted in a gamma counter (Wallac, Turku, Finland). The percentage of 51Cr released was determined according to the formula [(test release − spontaneous release)/(total release − spontaneous release)] × 100. The control percent release is always 100%.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Density gradient-enriched NK and T cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 with or without valinomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) at 100 ng ml−1. Cells were suspended in 10% FBS–RPMI 1640 medium and fixed for 1 h in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature, washed three times in phosphate buffer and then postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in the phosphate buffer at room temperature for 1 h. After being washed once, the specimens were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series and critical point dried. The dry cells were coated with platinum and photographed with a DSM 962 SEM (Zeiss).

Transmission electron microscopy.

PBL (2 × 106 to 4 × 106 ml−1) were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 with or without toxins at 100 ng ml−1. The cells were then treated like SEM specimens in an ethanol series and embedded in Epon. Sections were cut with an ultramicrotome and mounted on copper grids. The grids were double stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. The sections were viewed and photographed with a JEM-1200 EX transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

Morphological analysis.

Valinomycin-induced morphological changes were analyzed by SEM and transmission electron microscopy after incubation of the cells with toxins (100 ng ml−1) in 24-well plates for 3 h at 37°C.

Bacterial toxins.

Toxin from S. griseus 10/ppi was purified by HPLC and shown to be valinomycin as previously described (3). The toxin was very hydrophobic, and therefore it was diluted in methanol and applied straight to 96-well plates as a methanol solution. Methanol was dispensed before culturing of cells in the plates. Similar treatment of wells with methanol without bacterial toxins did not affect NK activity or lymphocyte morphology (data not shown).

Apoptosis assay.

Apoptosis of enriched NK and T cells (after two-step density gradient separation) was measured by using an ApoAlert Annexin V apoptosis kit (Clontech), in which annexin V is fluorescein isothiocyanate labeled. The results were analyzed by using a FACScan flow cytometer.

Cytokines and cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays.

The NK cells (2 × 106 ml−1) in 10% FBS–RPMI medium purified by immunomagnetic beads were first treated with the toxins (100 ng ml−1) for 2 h and then further for 24 h with IL-15 (5 ng ml−1; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.), IL-18 (20 ng ml−1; Hayashibara Biochemical, Okayama, Japan), or a combination of IL-15 and IL-18. The culture supernatants were harvested, and the cytokine concentrations were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using paired antibodies for IFN-γ (Diaclone, Besançon, France) and GM-CSF (PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.).

RESULTS

Inhibition of NK activity by valinomycin.

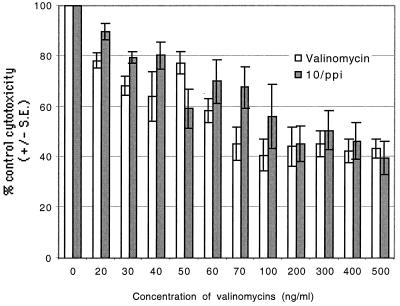

In order to test the effects of commercially available valinomycin and our own HPLC-pure valinomycin on NK cell activity, we incubated NK cells with different concentrations of valinomycin (0 to 500 ng ml−1) and tested their cytotoxic properties. Commercial valinomycin lowered the cytotoxicity of PBL to 25% of the control values at a concentration of 30 ng ml−1. HPLC-pure valinomycin from S. griseus 10/ppi inhibited NK activity in a similar fashion (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Inhibition of NK activity by commercial valinomycin and HPLC-purified valinomycin from S. griseus 10/ppi. There was clear inhibition of cytotoxicity at concentrations of 30 ng ml−1 and above, reaching a plateau at 100 ng ml−1. The kinetics of toxin-induced inhibition was rapid, occurring within 1 min (measurements at 1, 10, 20, and 30 min and 1, 2, 3, and 4 h [data not shown]).

The kinetics of NK cell inhibition by the toxins was tested with both valinomycin preparations after 1, 10, and 20 min. Cytotoxicity was already inhibited at 1 min of incubation with the toxins. Cytotoxicity was also tested with commercial valinomycin at different incubation times (0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 h), but no further reduction in cytotoxicity was seen compared to the values obtained after the 1-min incubation (data not shown).

Morphology of toxin-treated NK cells.

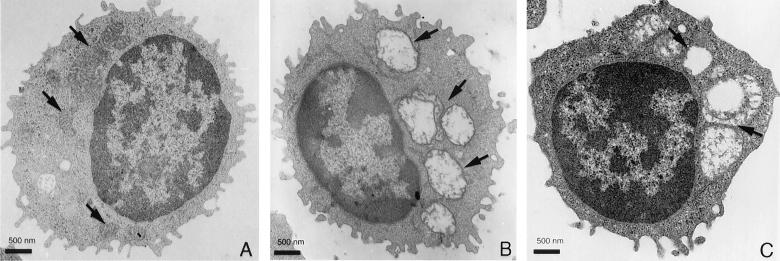

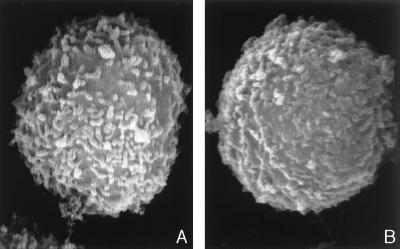

To analyze the potential effect of valinomycin on cell morphology, NK cells were treated with valinomycin (100 ng ml−1) for 3 h. A high toxin concentration was chosen since the morphological changes were faster with larger doses. There was clearly detectable vacuole formation in toxin-treated cells, and in transmission electron microscopy the vacuoles appeared as swollen mitochondria (Fig. 2A, B, and C). The two toxins showed similar dose-dependent morphological changes. When valinomycin-treated cells were analyzed by SEM, they showed certain differences in surface structure, such as shorter surface projections and a smoother plasma membrane (Fig. 3A and B).

FIG. 2.

Morphology of NK cells in transmission electron microscopy. Panels: A, normal NK cell with normal mitochondria (arrows); B, NK cell pretreated with commercial valinomycin (mitochondria are swollen and distorted [arrows]); C, NK cell pretreated with HPLC-purified valinomycin (morphological effect similar to that in panel B [arrows]).

FIG. 3.

Morphology of NK cells in SEM (magnification, ×20,000). Panels: A, normal NK cell with normal surface projections; B, NK cells pretreated with valinomycin. The surface projections are shorter and thicker than in a normal NK cell.

Valinomycin-induced apoptosis of NK cells.

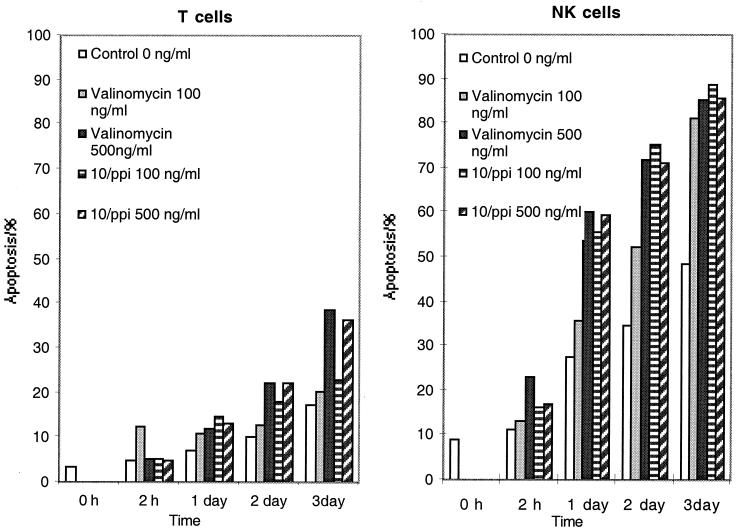

Next we addressed the question of whether valinomycin can induce apoptosis in T and NK cells. The results in Fig. 4 show that valinomycin at 100 ng ml−1 can program NK cells to enter apoptosis within 1 day. One microgram of valinomycin was obtained from 0.1 mg (dry weight) of S. griseus cells (a 1-mg wet weight is equivalent to 108 cells). At day 1 in the control cell population, 27% of the cells were apoptotic, compared to 60% of toxin-treated NK cells. The kinetics of apoptosis was somewhat faster with a 500-ng ml−1 dose. T cells were clearly more resistant to valinomycin-induced apoptosis since at day 3, 40% of T cells, in contrast to 85% of NK cells, were apoptotic (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Apoptosis induced in lymphocytes by commercial valinomycin and S. griseus 10/ppi valinomycin. The toxins selectively caused more apoptosis in NK cells than in T cells.

Effects of IL-15 and IL-18 on NK cell functions.

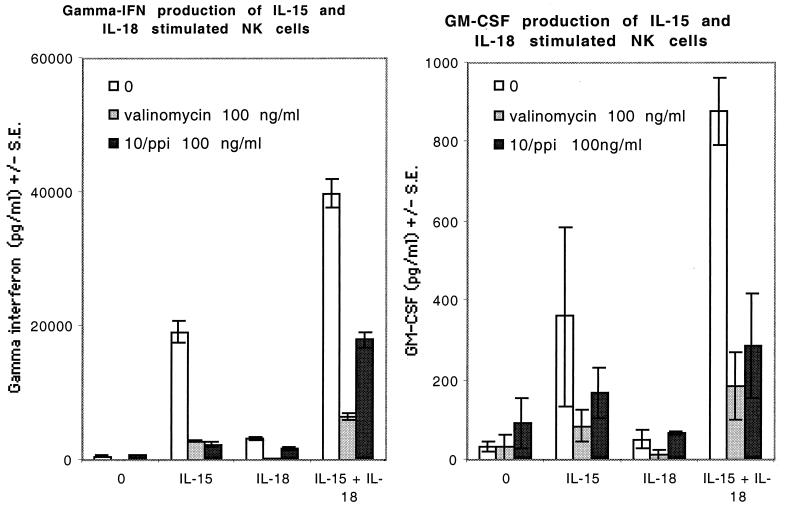

IL-15 induced strong IFN-γ and GM-CSF secretion from NK cells, whereas IL-18 alone resulted in only a modest increase in cytokine production. However, a combination of IL-15 and IL-18 showed a clear synergistic effect on the production of IFN-γ and GM-CSF. Cytokine secretion induced by IL-15 alone was strongly inhibited by valinomycin, whereas a combination of IL-15 and IL-18 appeared to be less vulnerable to valinomycin-induced inhibition of NK cell cytokine production (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

IFN-γ and GM-CSF production of IL-15- and/or IL-18-stimulated NK cells and effects of commercial and S. griseus 10/ppi valinomycins on cytokine production. The stimulatory effects of IL-15 and IL-18 on cytokine production are synergistic. Valinomycin almost completely inhibits IL-15-induced cytokine production, whereas there is some cytokine production left in cells activated by a combination of IL-15 and IL-18 and pretreated with valinomycin. The P values in paired t tests for the differences between IFN-γ production by lymphocytes treated with IL-15 with valinomycin and that by lymphocytes treated with IL-15 and IL-18 with valinomycin are <0.0137 (valinomycin) and <0.0237 (10/ppi), and for treatment with IL-18 with valinomycin versus treatment with IL-15 and IL-18 with valinomycin they are <0.0119 (valinomycin) and <0.0231 (10/ppi). The P values in the same comparisons for GM-CSF production were insignificant.

DISCUSSION

The results of our study show that a bacterial dodecadepsipeptide, valinomycin, strongly inhibits the cytotoxicity and cytokine production of human NK cells and eventually induces NK cell apoptosis. We used two preparations of valinomycin, namely, a commercially available one purified from S. fulvissimus and HPLC-pure valinomycin from an indoor dust isolate of S. griseus. Valinomycin-producing strains of S. griseus were detected in indoor air and dust, settled dust, and building materials in public and private buildings with dampness damage (23). The detected loads of streptomycetes in buildings where the occupants were experiencing long-term health problems were 101 to 103 CFU m−3 (3, 5, 23). Up to 30% of these organisms were found to be toxic (23). Viable, as well as nonviable, cells may contain valinomycin. Counting of viable airborne bacteria is believed to underestimate the aerosolized cell count by factors of up to 102 to 103 (2, 20). Therefore, the load of airborne valinomycin may reach levels of 0.1 ng m−3, which means 1 to 2.5 ng of valinomycin respired per occupant per day. In addition, 103 to 104 CFU of Streptomyces g−1 were found in moisture-damaged indoor building materials (4, 23), further increasing the airborne load of valinomycin. Valinomycin is highly hydrophobic (19) and therefore likely aerosolized. When inhaled, valinomycin is probably rapidly absorbed into the circulation. Thus, at least in theory, valinomycin may be a factor involved in health problems associated with poor quality of indoor air.

Valinomycin caused marked apoptosis of NK cells. The intrinsic tendency of NK cells toward apoptosis was quite distinct (Fig. 4), and it may be that valinomycin only accelerates this process. Valinomycin has previously been shown to induce apoptosis in cultured human hepatoma cells by increasing the activity of the caspase-3 protease, whereas no release of reactive oxygen species from mitochondria or increase in the intracellular calcium concentration has been seen (12, 14). In murine hematopoietic cells (pre-B-cell line BAF3), valinomycin triggers a rapid loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (13). Valinomycin also causes mitochondrial swelling and inhibits the mobility of boar spermatozoa (3). Our present results, showing valinomycin-induced mitochondrial swelling, changes in membrane architecture, and eventual apoptosis of NK cells, suggest that the mechanisms of valinomycin toxicity are probably similar in different cell types.

Upon contact with a target cell and stimulation with IL-12, NK cells produce IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and GM-CSF (6). IL-12 and IFN-γ are pivotal cytokines in the Th1 type of immune response, which is important in the defense against intracellular microbes and malignancy (25). Compromised NK activity has particularly been associated with recurrent herpesvirus infections (6). Lack of IFN-γ may also drive the immune response to the Th2 type, which favors an allergic type of immune response (25). It remains to be seen whether chronic exposure to valinomycin-containing dust in indoor air will affect the capacity of NK cells to produce cytokines in vivo and whether valinomycin exposure results in a decrease in the number of circulating NK cells. At least the fast kinetics of the toxicity of valinomycin overcomes the natural renewal cycle of NK cells (30).

IL-18 is a recently identified cytokine the production of which is restricted to phagocytic cells (31). IL-18 strongly augments IFN-γ production in NK and T cells in synergy with IL-12 or IFN-α (18, 22, 27, 35). Human IL-18 has also been reported to induce GM-CSF production and enhanced NK cell activity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (31). IL-18 knockout mice have impaired IFN-γ production, reduced NK cell activity, and poor development of a Th1 response after bacterial challenge (29). It has previously been shown that IL-15 induces IFN-γ production by NK cells (8, 9). We have previously observed that IL-18 synergizes with IL-15 in the up-regulation of IFN-γ production by NK cells (28), and similar synergy was also seen in the present experiments. The combination of IL-15 and IL-18 also showed some tendency to better retain the IFN-γ production of valinomycin-treated NK cells. It will be of interest to examine whether IL-15 and IL-18, separately or in combination, would exert antiapoptotic effects on NK cells.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that valinomycin, produced by bacteria frequently found in indoor air, settled dust, and building materials, impairs NK cytotoxicity and cytokine production. This is the first evidence that a relatively prevalent environmental toxin can reduce NK cell functions. Inhibition of NK activity has previously been shown to be induced by diphtheria (32) and pertussis toxins (33), which are very seldom encountered in the environment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported by the Academy of Finland, TEKES, the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the Helsinki University Central Hospital, and the Helsinki University Fund for Center of Excellence.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allbritton N L, Verret C R, Wolley R C, Eisen H N. Calcium ion concentrations and DNA fragmentation in target cell destruction by murine cloned cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1988;167:514–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez A, Buttner M, Stetzenbach L. PCR for bioaerosol monitoring: sensitivity and environmental interference. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3639–3644. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.10.3639-3644.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson M A, Mikkola R, Kroppenstedt R M, Rainey F A, Peltola J, Helin J, Sivonen K, Salkinoja-Salonen M. Mitochondrial toxin produced by Streptomyces griseus strains isolated from an indoor environment is valinomycin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4767–4773. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4767-4773.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson M A, Nikulin M, Koljalg U, Andersson M C, Rainey F, Reijula K, Hintikka E-L, Salkinoja-Salonen M S. Bacteria, molds, and toxins in water-damaged building materials. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:387–393. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.387-393.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson M A, Weiss N, Rainey F A, Salkinoja-Salonen M S. Dustborne bacteria in animal sheds, schools and children's day care centers. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;86:622–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biron C A. Activation and function of natural killer cell responses during viral infections. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:24–34. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brittenden J, Heys S, Ross J, Eremin O. Natural killer cells and cancer. Cancer. 1996;77:1226–1243. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19960401)77:7<1226::aid-cncr2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carson W E, Fehniger T A, Haldar S, Eckhert K, Lindemann M J, Lai C F, Croce C M, Baumann H, Caligiuri M A. A potential role for interleukin-15 in the regulation of human natural killer cell survival. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:937–943. doi: 10.1172/JCI119258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carson W E, Ross M E, Baiocchi R A, Marien M J, Boiani N, Grabstein K, Caligiuri M A. Endogenous production of interleukin 15 by activated human monocytes is critical for optimal production of interferon-gamma by natural killer cells in vitro. J Clin Investig. 1995;96:2578–2582. doi: 10.1172/JCI118321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deckers C L, Lyons A B, Samuel K, Sanderson A, Maddy A H. Alternative pathways of apoptosis induced by methylprednisolone and valinomycin analyzed by flow cytometry. Exp Cell Res. 1993;208:362–370. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duax W L, Griffin J F, Langs D A, Smith G D, Grochulski P, Pletnev V, Ivanov V. Molecular structure and mechanisms of action of cyclic and linear ion transport antibiotics. Biopolymers. 1996;40:141–155. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1996)40:1%3C141::AID-BIP6%3E3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duke R C, Witter R Z, Nash P B, Young J D, Ojcius D M. Cytolysis mediated by ionophores and pore-forming agents: role of intracellular calcium in apoptosis. FASEB J. 1994;8:237–246. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.8119494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furlong I J, Lopez Mediavilla C, Ascaso R, Lopez Rivas A, Collins M K L. Induction of apoptosis by valinomycin: mitochondrial permeability transition causes intracellular acidification. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:214–221. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inai Y, Yabuki M, Kanno T, Akiyama J, Yasuda T, Utsumi K. Valinomycin induces apoptosis of ascites hepatoma cells (AH-130) in relation to mitochondrial membrane potential. Cell Struct Funct. 1997;22:555–563. doi: 10.1247/csf.22.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leibson P. Signal transduction during natural killer cell activation: inside the mind of a killer. Immunity. 1997;6:655–661. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lodolce J P, Boone D L, Chai S, Swain R E, Dassapoulos T, Trettin S, Ma A. IL-15 receptor maintains lymphoid homeostasis by supporting lymphocyte homing and proliferation. Immunity. 1998;9:669–676. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80664-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lozzio C, Lozzio B. Cytotoxicity of factor isolated from human spleen. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1973;50:535–538. doi: 10.1093/jnci/50.2.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Micallef M J, Ohtsuki T, Kohno K, Tanabe F, Ushio S, Namba M, Tanimoto T, Torigoe K, Fujii M, Ikeda M, Fukuda S, Kurimoto M. Interferon-gamma-inducing factor enhances T helper 1 cytokine production by stimulated human T cells: synergism with interleukin-12 for interferon-gamma production. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1647–1651. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikkola R, Saris N E, Grigoriev P A, Andersson M A, Salkinoja-Salonen M S. Ionophoretic properties and mitochondrial effects of cereulide: the emetic toxin of B. cereus. Eur J Biochem. 1999;263:112–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neef A, Amann R, Schleifer K-H. Detection of microbial cells in aerosols using nucleic acid probes. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1995;18:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ojcius D M, Zychlinsky A, Zheng L M, Young J D. Ionophore-induced apoptosis: role of DNA fragmentation and calcium fluxes. Exp Cell Res. 1991;197:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90477-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamura H, Tsutsi H, Komatsu T, Yutsudo M, Hakura A, Tanimoto T, Torigoe K, Okura T, Nukada Y, Hattori K, Akita K, Namba M, Tanabe F, Konishi K, Fukuda S, Kurimoto M. Cloning of a new cytokine that induces IFN-gamma production by T cells. Nature. 1995;378:88–91. doi: 10.1038/378088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peltola J, Andersson M, Haahtela T, Mussalo-Rauhamaa H, Salkinoja-Salonen M S. Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Indoor Air Quality and Climate and 20th AIVC Conference, Indoor Air 99. Vol. 2. 1999. Toxigenic indoor actinomycetes and fungi: case study, abstr. 621; pp. 560–561. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson J M, Ritz J. Biology and clinical relevance of human natural killer cells. Blood. 1990;76:2421–2438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romagnani S. The Th1/Th2 paradigm. Immunol Today. 1997;18:263–266. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)80019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salkinoja-Salonen, M. S., M. A. Andersson, R. Mikkola, A. Paananen, J. Peltola, H. Mussalo-Rauhamaa, R. Vuorio, N.-E. Saris, P. Grigorjev, J. Helin, U. Koljalg, and T. Timonen. Toxigenic microbes in indoor environment: identification, structure and biological effects of the aerosolizing toxins. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Bioaerosols, Fungi and Mycotoxins, in press. Mount Sinai Press, New York, N.Y.

- 27.Sareneva T, Matikainen S, Kurimoto M, Julkunen I. Influenza A virus-induced IFN-alpha/beta and IL-18 synergistically enhance IFN-gamma gene expression in human T cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:6032–6038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sareneva T, Matikainen S, Miettinen M, Paananen A, Kurimoto M, Timonen T, Julkunen I. Cytokine-induced IFN-gamma gene expression in human NK and T cells. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1998;9:543. . (Abstract.) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeda K, Tsutsui H, Yoshimoto T, Adachi O, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T, Okamura H, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Defective NK cell activity and Th1 response in IL-18-deficient mice. Immunity. 1998;8:383–390. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trinchieri G. Biology of natural killer cells. Adv Immunol. 1989;47:187–376. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60664-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ushio S, Namba M, Okura T, Hattori K, Nukada Y, Akita K, Tanabe F, Konishi K, Micallef M, Fujii M, Torigoe K, Tanimoto T, Fukuda S, Ikeda M, Okamura H, Kurimoto M. Cloning of the cDNA for human IFN-gamma-inducing factor, expression in Escherichia coli, and studies on the biologic activities of the protein. J Immunol. 1996;156:4274–4279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waters C A, Schimke P A, Snider C E, Itoh K, Smith K A, Nichols J C, Strom T B, Murphy J R. Interleukin 2 receptor-targeted cytotoxicity. Receptor binding requirements for entry of a diphtheria toxin-related interleukin 2 fusion protein into cells. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:785–791. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whalen M M, Doshi R N, Bankhurst A D. Effects of pertussis toxin treatment on human natural killer cell function. Immunology. 1992;76:402–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zanovello P, Bronte V, Rosato A, Pizzo P, Di Virgilio F. Responses of mouse lymphocytes to extracellular ATP. II. Extracellular ATP causes cell type-dependent lysis and DNA fragmentation. J Immunol. 1990;145:1545–1550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang T, Kawakami K, Qureshi M H, Okamura H, Kurimoto M, Saito A. Interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-18 synergistically induce the fungicidal activity of murine peritoneal exudate cells against Cryptococcus neoformans through production of gamma interferon by natural killer cells. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3594–3599. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3594-3599.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]