Abstract

Background

This systematic review and meta-analysis examined the prevalence of depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and posttraumatic stress symptoms among children and adolescents during global COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 to 2020, and the potential modifying effects of age and gender.

Methods

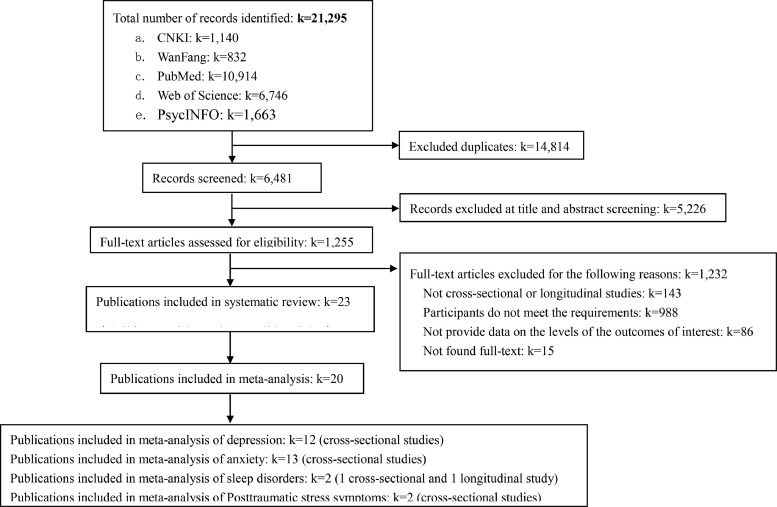

A literature search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and two Chinese academic databases (China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang) for studies published from December 2019 to September 2020 that reported the prevalence of above mental health problems among children and adolescents. Random-effects meta-analyses were used to estimate the pooled prevalence.

Results

Twenty-three studies (21 cross-sectional studies and 2 longitudinal studies) from two countries (i.e., China and Turkey) with 57,927 children and adolescents were identified. Depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and posttraumatic stress symptoms were assessed in 12, 13, 2, and 2 studies, respectively. Meta-analysis of results from these studies showed that the pooled prevalence of depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and posttraumatic stress symptoms were 29% (95%CI: 17%, 40%), 26% (95%CI: 16%, 35%), 44% (95%CI: 21%, 68%), and 48% (95%CI: -0.25, 1.21), respectively. The subgroup meta-analysis revealed that adolescents and females exhibited higher prevalence of depression and anxiety compared to children and males, respectively.

Limitations

All studies in meta-analysis were from China limited the generalizability of our findings.

Conclusions

Early evidence highlights the high prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially among female and adolescents. Studies investigating the mental health of children and adolescents from countries other than China are urgently needed.

Keywords: Mental health problems, COVID-19 pandemic, Children, Adolescents, Review

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019) pandemic has affected the mental health (e.g., depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and posttraumatic stress symptoms) of children and adolescents (Golberstein et al., 2020). As of April 8, 2020, schools have been suspended nationwide in 188 countries (Lee, 2020). Prolonged school closures, strict social isolation from peers, teachers, extended family, and community networks, economic shutdown, and the pandemic itself have contributed to the mental health problems of children and adolescents (Holmes et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2020). While some children may benefit from increased interaction with parents and siblings, many have experienced elevated levels of emotional distress (Sprang and Silman, 2013; Xie et al., 2020). Being confined to home leads to disturbances in sleep/wake cycles and physical exercise routines, and promotes excessive use of technology (Xie et al., 2020). The pandemic may increase family financial stressors and parental unemployment, which were associated with short- and long-term consequences on child mental health (Costello et al., 2003). There is also an increased risk of seeing or experiencing domestic violence and emotional, physical and/or sexual abuse (Costello et al., 2003). It is assumed that relaxing lockdown restrictions and returning to school might improve the mental health status of children as the economy and social practices begin to normalize globally (Tan et al., 2020). Understanding the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents would provide a theoretical basis for designing interventions, planning resources, and promulgating policies necessary to protect young people from such occurrences in future (Pappa et al., 2020).

Several original studies have found high levels of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic (Duan et al., 2020; Pınar Senkalfa et al., 2020; Türkoğlu et al., 2020). However, to the best of our knowledge to date, no systematic review to synthesize the impact of the pandemic on their mental health has been performed. While there are some systematic reviews on the psychological impacts of COVID-19 on patients and healthcare workers (Pappa et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2020; Rogers et al., 2020), evidence in children and adolescents is lacking.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to examine the emerging evidence of the effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on the mental health of children and adolescents aged 18 years and under. In particular, we aimed to examine the prevalence of depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and posttraumatic stress symptoms among uninfected/not known to be infected children and adolescents during the active phase of the pandemic during 2019 to 2020. The potential modifying effects of age and gender on the prevalence were also examined.

2. Methods and materials

This study was developed and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) (Moher et al., 2009) and other standards (Johnson and Hennessy, 2019). The study protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO (registration no: CRD42020205166).

3. Literature search and study selection

A systematic search was performed in three English electronic bibliographic databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science, and two Chinese academic databases: China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and Wanfang. The following search terms were used: (“Novel coronavirus” OR “SARS-COV-2” OR “COVID-19” OR “2019-nCov”) AND (“depression” OR “anxiety” OR “sleep*” OR “posttraumatic stress symptoms”, “mental health*” OR “psychological*” OR “psychiatry” OR “insomnia”). The specific search algorithm is provided in Supplemental Table 1. Studies reported the prevalence of self-reported mental health problems and symptoms were included. Two authors independently searched the same database with these search terms to ensure that none of the relevant studies was missed.

Titles and abstracts of the articles identified were screened against the study selection criteria by two independent reviewers. Potentially relevant articles were retrieved for an evaluation of the full text. Inter-rater agreement was assessed using the Cohen's kappa (k=0.64). Disagreements were reviewed and resolved through discussion with third author to resolve persistent inconsistencies.

This search strategy was further supplemented with hand searching of reference lists of included articles and through tracking the citations of eligible references in Google Scholar. Articles identified from the reference lists were further screened and evaluated by using the same criteria. Reference searches were repeated on all newly identified articles until no additional relevant articles were found.

3.1. Study selection criteria

Studies were included if they: (a) evaluated the prevalence of depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and posttraumatic stress symptoms using validated assessment method among children and adolescents aged 18 years and under; (b) were written in English or Chinese; (c) were carried out between December 2019 to September 2020; and (d) were cross-sectional or longitudinal studies. When there were studies involving the same participants, only the most comprehensive or recent publication was included.

Studies were excluded if they: (a) were qualitative studies, case reports, editorials, protocols, meta-analysis, or reviews, (b) computer-based simulation studies with no human participants, c) included participants with COVID-19 infected, d) studies that did not provide data on the levels of the outcomes of interest, or e) studies focused on the prevalence of suicidal behaviours, suidal ideations and attempts among children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic.

3.2. Data extraction and preparation

A standardized data extraction form was developed to extract the following data from each article: author, study design, country, survey years, average age of participants, sample size (percentage of male participants), sampling strategy, mental health problems, diagnostic or screening instrument used, specific diagnostic criteria or screening instrument cutoff, and reported prevalence estimates of mental health problems. The data were extracted independently by two independent reviewers, and disagreements were reviewed and resolved through discussion with third reviewer to resolve persistent inconsistencies.

3.3. Study quality assessment

Two authors independently assessed the quality of the articles using the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. (Study Quality Assessment Tools, 2021) The assessment tool rates each study based on 14 criteria. For each criterion, a score of one was assigned if “yes” was the response, whereas a score of zero was assigned otherwise (i.e., an answer of “no,” “not applicable,” “not reported,” or “cannot determine”). Overall quality was rated based on the total score of the scale: “7 ≤ total score” = good, “4<total score≤6” = fair, “total score<4” = poor. The risk of bias of each study decreased with the increase in the total score.

3.4. Statistical analysis

Prevalence estimates of mental health problems were calculated by pooling the study-specific estimates using random-effects (using the DerSimonian‐Laird method) meta-analyses that accounted for between-study heterogeneity (Borenstein et al., 2010). When studies reported point prevalence estimates made at different periods within the year, the overall period prevalence was used.

Study heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 index and Tau-squared (T2). The level of heterogeneity represented by I2 was interpreted as modest (I2≤25%), moderate (25%<I2≤50%), substantial (50%<I2≤75%), or considerable (I2>75%). Sensitivity analyses was performed by serially excluding each study to determine the influence of individual studies on the overall prevalence estimates.

Results from studies grouped according to prespecified study-level characteristics were compared using stratified meta-analysis (gender, diagnostic criteria or screening instrument, region, and country).

Publication bias was assessed by a visual inspection of contour-enhanced funnel plots and Egger's regression tests. All statistical analyses were conducted in STATA with specific commands (e.g., Metan and Metareg) (Version 14.0; Stata Corp., College Station, Texas, U.S.). All analyses used two-sided tests, and p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of included studies

A total of 23 studies were included in the systematic review, the characteristics of which are summarized in Table 1 . These studies were published predominantly from February to May 2020 with one longitudinal study including data from October 2019. The vast majority of studies were from China (21 studies), with the remaining studies from Turkey (2 studies). The sample size of these studies varied greatly, ranging from 46 to 9,554 participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 23 studies included in the review

| Author/Survey time (Year, month) | Study design | Country | Age, years (mean±SD or range) | Sample size (Boys, %) | Participant type a | Assessment method & cutoff score | Mental health problems (n, %/M±SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Anxiety | Sleep disorders | Posttraumatic stress symptoms | |||||||

| 1.Türkoğlu S/ 2020, May (Türkoğlu et al., 2020) | Cross-sectional | Turkey | Mean:7.89/4-17 | 46(82.6%) | Autism Spectrum Disorder | AuBC, CSHQ (>41); Diagnosed by health providers | NR | NR | Total CSHQ scores increased from 47.82 ± 7.13 to 50.80 ± 8.15 | NR |

| 2.Senkalfa BP/2020, April (Pınar Senkalfa et al., 2020) | Cross-sectional | Turkey | Cystic Fibrosis group 0-18 Control group 0-18 |

Cystic Fibrosis group 45 (51.1%) Control group 90(51.1%) |

Cystic Fibrosis | STAI; Diagnosed by health providers | NR | Children aged 13–18 years in the control group:29.0 (27.8-32.3); Age-matched children with Cystic Fibrosis 41.5 (35.5-46.3) | NR | NR |

| 3.Chen F/2020, April (Chen et al., 2020) | Cross-Sectional | China | 6-15 Children:6-12 Adolescents:13-15 |

1036(51.0%) | General | DSRS-C (15), SCARED (25); Self-reported by participants | 122(11.8%) | 196(18.9%) | NR | NR |

| 4.Chen IH/2019, October-2020, March Chen et al., 2020 | Longitudinal | China | 10.88±0.72 | 543(49.0%) | General | DASS-21; Self-reported by participants | Mean:1.22 95%CI: (1.19,1.25) | NR | NR | NR |

| 5. Qi M/2020, March Qi et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | Adolescents:14-18 | 7202(46.4%) | General | PHQ-9 (5), GAD-7 (5); Self-reported by participants | 3207(44.5%) | 2736(38.0%) | NR | NR |

| 6.Zhou SJ/2020, March Zhou et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | Adolescents:12-18 | 8079(46.5%) | General | PHQ-9 (5), GAD-7 (5); Self-reported by participants | 3533(43.7%) | 3020(37.4%) | NR | NR |

| 7.Xie X/ 2020, February-2020, March Xie et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | NR | 1784(56.7%) | General | CDI-S (7), SCARED (≥23); Self-reported by participants | 403(22.6%) | 337(18.9%) | NR | NR |

| 8.Zhu KH/2020, February-2020, March Zhu et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | NR | 1264(55.9 %) | General | SCARED (23); Self-reported by participants | NR | 234(18.5 %) | NR | NR |

| 9.Lin L/2020, February Lin et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | NR | 76(NR) | General | ISI(10), PHQ-9 (10), GAD-7 (10), ASDS (28); Self-reported by participants | NR | NR | 24(31.6%) | NR |

| 10.Liu Z/2020, February Vindegaard and Benros, 2020 | Longitudinal | China | Children: 4-6 | 1619(48.9%) | General | CSHQ (41); Reported by caregivers of participants | NR | NR | 900(55.6%) | NR |

| 11.Qi H/2020, February Qi et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | Adolescents:11-20 | 9554(NR) | General | GAD-7 (5); Self-reported by participants | NR | 1814(19.0%) | NR | NR |

| 12.Zhou J/2020, February Zhou et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | Adolescents:11-18 | 4805(0.0%) | General | CES-D (16); Self-reported by participants | 1899(39.5%) | NR | NR | NR |

| 13.Li SW/2020, February Li et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | 12.82±2.61/8-18 | 396(50.3%) | General | SCARED(25); Self-reported by participants | NR | 87(22.0%) | NR | NR |

| 14.Mo DM/2020, February Mo et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | 7-16 Children:7-12 Adolescents:13-16 |

5392(54.5%) | General | SCARED(23); Self-reported by participants | NR | 1045(19.4%) | NR | NR |

| 15.Tang S/2020, February Tang and Pang, 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | 640 primary school students and 233 junior high school students: NR | 873(52.3%) | General | SAS(standard score 50) CDI(>19); Self-reported by participants | Children: 41(6.4%); Adolescents: 61(26.2%) | Children: 19(3.0%); Adolescents:46(19.7%) | NR | NR |

| 16.Wang Y/2020, February Wang et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | 12.82±2.61/8-18 | 396(50.3%) | General | DSRS(15); Self-reported by participants | 41(10.4%) | NR | NR | NR |

| 17.Yu QX/2020, February Yu et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | NR | 2074(52.4%) | General | Psychological Questionnaire for Sudden Public Health Events (each factor score2); Self-reported by participants | 53(2.6%) | 13(0.6%) | NR | NR |

| 18.Zhang Y/2020, February Zhang et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | NR | 4225(47.4%) | General | PCL-C(39); Self-reported by participants | NR | NR | NR | 448(10.6%) |

| 19.Liu X/ 2020, January-2020, February Liu et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | NR | 34(NR) | General | STAI, SDS (50); Self-reported by participants | 13(38.2%) | NR | NR | NR |

| 20.Hou TY/2020, NR Hou et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | NR | 859(61.4%) | General | PHQ-9 (10), GAD-7 (8), IES-R(26); Self-reported by participants | 614(71.5%) | 468(54.5%) | NR | 735(85.5%) |

| 21.Li D/ 2020, NR Duan et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | 7-18 Children:7-12 Adolescents:13-18 |

3613(50.2%) | General | SCAS, CDI(19); Self-reported by participants | 805(22.3%) | Children: 23.87 ± 15.79 Adolescents:29.27 ± 19.79 |

NR | NR |

| 22.Tang L/2020, NR Tang and Ying, 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | 14.01±1.56 | 3512(49.1%) | General | MMHI-60(each factor score 2); Self-reported by participants | 924(26.3%) | 1047(29.8%) | NR | NR |

| 23.Wang NX/2020, NR Wang and Xu, 2020 | Cross-sectional | China | NR | 410(31.5%) | General | GAD-7(5); Self-reported by participants | NR | 197(48.0%) | NR | NR |

NR: Not reported.

DSRS-C: Depression Self-Rating Scale for Children; SCARED: Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders; DASS-21: Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale 21; PHQ-9: 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7: 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; IES-R: Impact of Events Scale - Revised; SCAS: Spence Child Anxiety Scale; STAI: State and Trait Anxiety Inventory; SDS: Self-rating Depression Scale; CSHQ: Children's Sleep Habit Questionnaire; SCL-90: Symptom Checklist-90; AuBC: Autism, Behavior Checklist; CDI-S: Children's Depression Inventory–Short Form; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SAS: Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; DSRS: Depression Self-rating Scale for Children; PCL-C: The PTSD Cheeklist-CivilianVersion; MMHI-60: Mental Health Inventory of Middle-school students.

Two of the studies used teleconference survey, the others used online survey. Two of the studies used random cluster sampling, the others used purposive sampling, snowball sampling, and convenient sampling (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Survey and sampling method of the 23 studies included in the review.

| Author/Survey time (Year, month) | Survey method | Sampling method | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability sampling | Nonprobability sampling | ||

| 1. Türkoğlu S/ 2020, May | Teleconference survey | Purposive sampling | |

| 2. Senkalfa BP/2020, April | Teleconference survey | Control group: Purposive sampling | |

| Age-matched children with Cystic Fibrosis: Snowball sampling | |||

| 3. Chen F/2020, April | Online survey | Purposive sampling | |

| 4. Chen I/2019, October-2020, March | Online survey | Purposive sampling | |

| 5. Qi M/2020, March | Online survey | Purposive sampling | |

| 6. Zhou S/2020, March | Online survey | Purposive sampling | |

| 7. Xie X/ 2020, February-2020, March | Online survey | Purposive sampling | |

| 8. Zhu KH/2020, February-2020, March | Online survey | Random cluster sampling | |

| 9. Lin L/2020, February | Online survey | Snowball sampling | |

| 10. Liu Z/2020, February | Online survey | Convenient sampling | |

| 11. Qi H/2020, February | Online survey | Snowball sampling | |

| 12.Zhou J/2020, February | Online survey | Snowball sampling | |

| 13. Li SW/2020, February | Online survey | Snowball sampling | |

| 14. Mo DM/2020, February | Online survey | Purposive sampling | |

| 15.Tang S/2020, February | Online survey | Purposive sampling | |

| 16. Wang Y/2020, February | Online survey | Snowball sampling | |

| 17. Yu QX/2020, February | Online survey | Purposive sampling | |

| 18. Zhang Y/2020, February | Online survey | Purposive sampling | |

| 19. Liu X/ 2020, January-2020, February | Online survey | Snowball sampling | |

| 20. Hou T/2020, NR | NR | Random cluster sampling | |

| 21. Li D/ 2020, NR | Online survey | Convenient sampling | |

| 22. Tang L/2020, NR | Online survey | Purposive sampling | |

| 23. Wang NX/2020, NR | Online survey | Purposive sampling | |

NR: Nor reported.

The study design and populations were diverse. There were 21 cross-sectional studies and 2 longitudinal studies. The majority of studies were carried out in healthy populations (21 studies), in a population with cystic fibrosis (1 study) and autism spectrum disorder (1 study). Some studies included adult participants in which case only data from child/adolescent participants was used in these analyses and participants’ ages ranged from 0 to 18 years.

Of particular note is the diversity of mental health-related scales used among these studies which included. A brief description of each mental health scale follows (in order of descending frequency):

-

•

7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) (6 studies): a self-report screening tool for generalized anxiety symptoms in the primary care setting consisting of 7 questions and validated in adolescents (Mossman et al., 2017);

-

•

Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) (5 studies): a self-report instrument for children and their parents that screens for several types of anxiety disorders including generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder (Monga et al., 2000);

-

•

9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (4 studies): a self-questionnaire consisting of nine items that assess the presence and severity of depressive symptoms based on the DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) (Richardson et al., 2010);

-

•

Depression Self-Rating Scale for Children (DSRS-C) (4 studies) is widely used to measure children's depressive symptoms and consists of 18 items (Ivarsson et al., 1994);

-

•

Children's Depression Inventory (including short form) (CDI-S) (3 studies): a self-report scale consisting of 27-items which evaluates the severity of depression in children and adolescents (Allgaier et al., 2012).

-

•

State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (2 studies): assesses state and trait anxiety in children for the determination of anxiety disorder and contains two scales of 20 items each (Nunn, 1988);

-

•

Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) (2 studies): is used to assess depressive syndrome and is validated in Chinese urban children (Su et al., 2003);

-

•

Children's Sleep Habit Questionnaire (CSHQ) (2 studies): a parent administered survey to assess children's sleep problems and consists of as 48 items divided into 5 scales focusing on different aspects of sleep behaviour (Tan et al., 2018);

-

•

Autism, Behavior Checklist (AuBC) (1 study): designed for the identification of children suspected of having autism and consisting of a list of atypical behaviors characteristic of the pathology (Sevin et al., 1991);

-

•

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (1 study):screens for depressive disorders in population‐based samples and is based on a multidimensional approach to measuring depression in children and adolescents aged 6 and 17 years (Li et al., 2010);

-

•

Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) (1 study): a norm-referenced screener that, in conjunction with the Self-rating Depression Scale has been shown to discriminate anxiety from mood disorders (Dunstan and Scott, 2020);

-

•

Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) (1 study):a widely used, 22 item questionnaire used to determine the degree of distress a patient feels in response to trauma and for identifying traumatic stress (Creamer et al., 2003);

-

•

Spence Child Anxiety Scale (SCAS) (1 study): a 38-item parents-report measure of anxiety symptoms for children and adolescents developed using community samples (Wang et al., 2016);

-

•

Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (1 study): a brief self-report instrument measuring the patient's perception of both nocturnal and diurnal symptoms of insomnia and comprising seven items (Gagnon et al., 2013);

-

•

Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21) (1 study): a set of three self-report scales designed to measure the emotional states of depression, anxiety and stress with each scale containing 7 items (Wang et al., 2016);

-

•

The PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C) (1 study): a standardized self-report rating scale comprising 17 items that correspond to the key symptoms of PTSD (Blanchard et al., 1996);

-

•

Mental Health Inventory of Middle-school students (MMHI-60) (1 study): a total of 60 items in the scale are used to measure the level of mental health of middle school students (Wang et al., 1997);

-

•

Psychological Questionnaire for Sudden Public Health Events (PQSPHE) (1 study): a total of 25 items to measure depression, neurosism, fear, obsessive anxiety, and hypochondria among adolescents (Zhang, 2005).

4.2. Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents

4.2.1. Depression

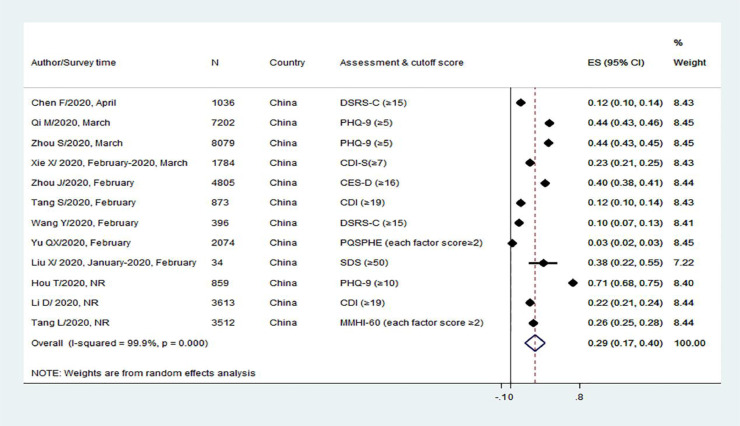

12 studies provided data on the prevalence of depression among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Meta-analysis of the results from these studies showed that the pooled prevalence of depression among children was 29% (95%CI: 17%, 40%) with a pooled heterogeneity of 99.9% (p < 0.001). The prevalence of depression reported in individual study ranges from 10% to 71% ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the literature search and study selection according to the PRISMA standard

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of the pooled prevalence of depression among children and adolescents (n=13)

Abbreviations: DSRS-C: Depression Self-Rating Scale for Children; PHQ-9: 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; CDI-S: Children's Depression Inventory–Short Form; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CDI: Children's Depression Inventory; DSRS-C: Depression Self-Rating Scale for Children; PQSPHE: Psychological Questionnaire for Sudden Public Health Events; SDS: Self-rating Depression Scale; MMHI-60: Mental Health Inventory of Middle-school students. Prevalence was calculated based on the random-effect models.

Sub-group analysis by age indicated that the prevalence of depression in adolescents age 13-18 years (34.4%, 95%CI: 18.2%, 50.7%; p<0.001) was higher than that of children age ≤ 12 years (11.8%, 95%CI: 1.3%, 22.3%, p=0.028). Sub-group analysis by gender showed that the prevalence of depression in females (33.9%, 95%CI: 24.6%, 43.1%, p<0.001) was higher than that in males (28.9%, 95%CI: 14.1%, 43.7%, p<0.001) (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Total and subgroup meta-analysis of pooled prevalence d (%, 95%CI) of depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and posttraumatic stress symptoms among children during the COVID-19 pandemic based on the included studies a

| Type of analysis | Groups | N of studies | Prevalence (%, 95% CI) | P value | Heterogeneity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (%) | χ2 | P | Tau-squared | |||||

| Depression | Total | 12 | 28.6 (17.2, 40.1) | <0.001 | 99.9 | 8025.91 | <0.001 | 0.0405 |

| Anxiety | Total | 13 | 25.5 (16.0, 35.1) | <0.001 | 99.9 | 10690.46 | <0.001 | 0.0307 |

| Sleep disorders b | Total | 2 | 44.2 (20.7, 67.7) | <0.001 | 94.8 | 19.22 | <0.001 | 0.0273 |

| Posttraumatic stress symptoms c | Total | 2 | 48.0 (-25.4, 121.4) | 0.200 | 100 | 3364.24 | <0.001 | 0.2804 |

| Depression | Children (≤12 years) | 3 | 11.8 (1.3, 22.3) | 0.028 | 98.9 | 183.35 | <0.001 | 0.0085 |

| Adolescents (13-18 years) | 8 | 34.4 (18.2, 50.7) | <0.001 | 99.9 | 7695.86 | <0.001 | 0.0548 | |

| Anxiety | Children | 6 | 15.7 (9.0, 22.3) | <0.001 | 98.7 | 389.71 | <0.001 | 0.0066 |

| Adolescents | 11 | 29.1 (17.1, 41.1) | <0.001 | 99.9 | 10269.07 | <0.001 | 0.0407 | |

| Depression | Male | 4 | 28.9 (14.1, 43.7) | <0.001 | 99.6 | 670.02 | <0.001 | 0.0228 |

| Female | 5 | 33.9 (24.6, 43.1) | <0.001 | 99.2 | 506.21 | <0.001 | 0.0110 | |

| Anxiety | Male | 7 | 22.3 (14.2, 30.4) | <0.001 | 99.1 | 650.31 | <0.001 | 0.0118 |

| Female | 7 | 27.4 (20.3, 34.6) | <0.001 | 98.6 | 431.08 | <0.001 | 0.0091 | |

All the studies included in meta-analysis were from China and among general children and adolescents, so no subgroup meta-analysis was conducted based on country and pre-existing conditions of children and adolescents.

Only two articles were found on sleep disorders, one was conducted among children and both boys and girls, the age and gender of participants in the other study were not reported, so no subgroup analysis was conducted based on age and gender.

Only two articles were found on posttraumatic stress symptoms, both studies did not report the age of participants and the gender-stratified prevalence, so no subgroup meta-analysis was conducted based on age and gender.

Prevalence was calculated based on the random-effect models.

4.2.2. Anxiety

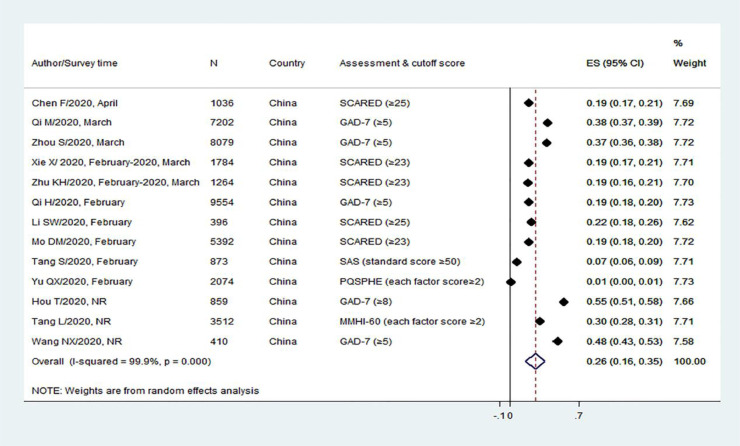

A total of 13 studies provided data on the prevalence of anxiety among children and adolescents during the pandemic. Meta-analysis of the results from these studies showed that the pooled prevalence of anxiety among children and adolescents was 26% (95%CI: 16%, 35%) with a pooled heterogeneity of 99.9% (p< 0.001). The prevalence of anxiety reported in individual study ranges from 7% to 55% (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis of the pooled prevalence of anxiety among all children and adolescents (n=12)

Abbreviations: SCARED: Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders; GAD-7: 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; SAS: Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; PQSPHE: Psychological Questionnaire for Sudden Public Health Events; MMHI-60: Mental Health Inventory of Middle-school students. Prevalence was calculated based on the random-effect models.

Sub-group analysis by age indicated that prevalence of anxiety in adolescents age 13-18 years (29.1%, 95%CI: 17.1%, 41.1%, p<0.001) was higher than that in children age ≤ 12 years (15.7%, 95%CI: 9.0%, 22.3%, p<0.001). Sub-group analysis by gender showed that the prevalence of anxiety of females (27.4%, 95%CI: 20.3%, 34.6%, p<0.001) was higher than that of males (22.3%, 95%CI: 14.2%, 30.4%, p<0.001) (Table 3).

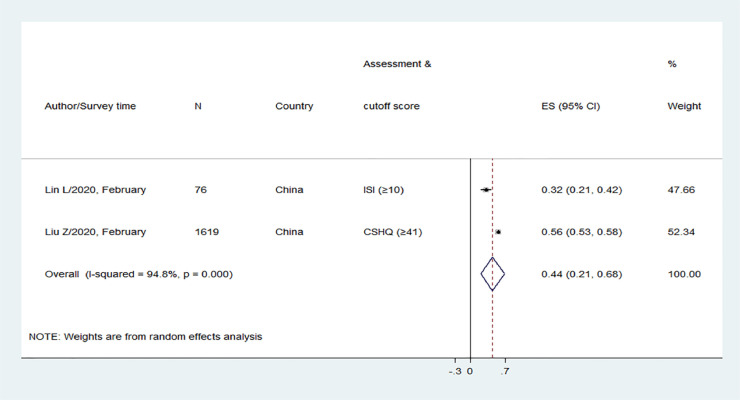

4.2.3. Sleep disorders

Only 2 studies provided data on the prevalence of sleep disorders among children and adolescents. Meta-analysis of the results of the two studies showed that the pooled prevalence of sleep disorders was 44% (95%CI: 21%, 68%) with a pooled heterogeneity of 94.8% (p<0.001). The prevalence of sleep disorders of the two studies were 32% to 56%, respectively (Fig. 4 ). Sub-group analyses by age and gender were not performed due to lack of data.

Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis of the pooled prevalence of sleep disorders among all children and adolescents (n=2)

Abbreviations: ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; CSHQ: Children's Sleep Habit Questionnaire. Prevalence was calculated based on the random-effect models.

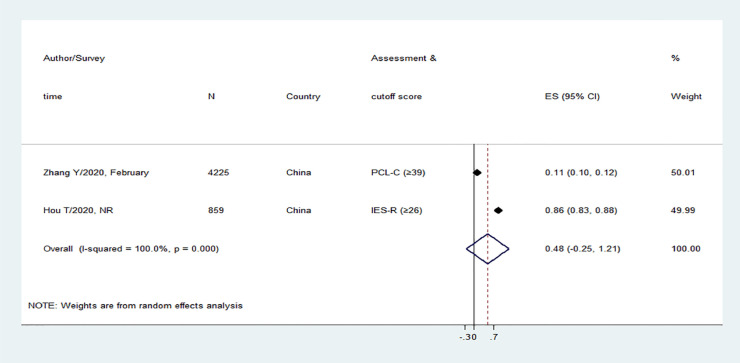

4.2.4. Posttraumatic stress symptoms

Only 2 studies provided data on the prevalence of post-traumatic stress symptoms among children and adolescents. In the pooled analysis, the prevalence of post-traumatic stress symptoms were not be statistically significant in children and adolescents (pooled prevalence 48% (95%CI: -0.25, 1.21, p=0.200) with a pooled heterogeneity of 100% (p<0.001) (Fig. 5 ). Sub-group analyses by age and gender were not performed due to lack of data.

Fig. 5.

Meta-analysis of the pooled prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptoms among all children and adolescents (n=2)

Abbreviations: PCL-C: The PTSD Cheeklist-CivilianVersion; IES-R: Impact of Events Scale-Revised. Prevalence was calculated based on the random-effect models.

4.3. Results of sensitivity analysis and meta-regression analysis

Sensitivity analysis consistently showed that removing individual studies from the meta-analysis did not lead to any change in the prevalence of depression or anxiety. Because only two studies were included in meta-analyses of sleep disorders and posttraumatic stress symptoms, sensitivity analysis was not conducted (Supplemental Table 3).

Meta-regression analysis was performed on the prevalence of depression (12 studies) and anxiety (13 studies). Results indicated that neither age nor sample size were significant factors contributing to the heterogeneity of studies (Depression: β=-0.02, 95%: -0.07 to 0.03, p=0.378; Anxiety: β=-0.01, 95%: -0.01, 0.01, p=0.285). However, the questionnaire used for assessment of anxiety or depression did significantly contribute to heterogeneity of studies. In the analysis of depression prevalence, PHQ-9 and CES-D, and in the analysis of anxiety prevalence, SCARED, SAS and PQSPHE contributed to heterogeneity ( Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Results of meta-regression analyses on the prevalence of depression and anxiety based on 12 studies on depression and 13 studies on anxiety a,b

| Type of analysis | β | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (n=12) | Age | -0.02 | -0.07, 0,03 | 0.378 |

| Sample size Assessment (Reference: CDI (≥19)) | 0.01 | -0.01, 0.01 | 0.285 | |

| DSRS-C (≥15) | -0.06 | -0.20, 0.08 | 0.270 | |

| PHQ-9 (≥5) | 0.27 | 0.13, 0.41 | 0.008 | |

| PHQ-9 (≥10) | 0.54 | 0.37, 0.72 | 0.002 | |

| CDI-S (≥7) | 0.06 | -0.12, 0.23 | 0.382 | |

| CES-D (≥16) | 0.22 | 0.05, 0.39 | 0.025 | |

| PQSPHE (each factor score≥2) | -0.14 | -0.31, 0.02 | 0.072 | |

| SDS (≥50) | 0.21 | -0.10, 0.52 | 0.122 | |

| MMHI-60 (each factor score≥2) | 0.09 | -0.08, 0.26 | 0.184 | |

| Anxiety (n=13) | Age | -0.01 | -0.05, 0.03 | 0.722 |

| Sample size Assessment (Reference: GAD-7 (≥5)) | 0.01 | -0.01, 0.01 | 0.813 | |

| SCARED (≥25) | -0.15 | -0.33, 0.03 | 0.092 | |

| SCARED (≥23) | -0.16 | -0.32, -0.01 | 0.045 | |

| SAS (standard score≥50) | -0.28 | -0.51, -0.05 | 0.026 | |

| PQSPHE (each factor score≥2) | -0.35 | -0.58, -0.12 | 0.011 | |

| GAD-7 (≥8) | 0.19 | -0.04, 0.43 | 0.094 | |

| MMHI-60 (each factor score≥2) | -0.06 | -0.29, 0.18 | 0.581 |

DSRS-C: Depression Self-Rating Scale for Children; SCARED: Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders; PHQ-9: 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7: 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; SDS: Self-rating Depression Scale; CDI-S: Children's Depression Inventory–Short Form; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SAS: Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; MMHI-60: Mental Health Inventory of Middle-school students; PQSPHE: Psychological Questionnaire for Sudden Public Health Events.

: Because only two articles were included for sleep disorders and posttraumatic stress symptoms, so no meta-regression analyses were conducted.

: Meta-regression analysis was used to evaluate the heterogeneity of different studies, adjusting age, gender, and measurement scale of depression and anxiety.

Numbers in bold indicate significance.

4.4. Assessment of publication bias

The funnel plot and assessment of Egger's and Begg's tests did not reveal any significant publication bias in the prevalence of depression, anxiety, sleep disorders or post-traumatic stress symptoms (Supplemental Table 2, Supplemental Figure 1).

5. Discussion

A recent position paper in The Lancet Psychiatry identified the long-term consequences of COVID-19 for the younger generations are unknown and must be a priority (Holmes et al., 2020). This systematic review and meta-analyses of 23 studies and a total of 57,927 participants provides evidence that 28.6%, 25.5%, 44.2%, and 48.0% of children and adolescents experienced depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and posttraumatic stress symptoms, respectively, during the COVID-19 pandemic. All the studies included in meta-analysis were from China and conducted among general children and adolescents. The prevalence of depression and anxiety was higher among adolescents and females compared with children and males, respectively.

The prevalence of depression and sleep disorders in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 were higher than the respective rates 19.9% for depression (Rao et al., 2019) and 21.6% for sleep disorders (Xiao et al., 2019), reported for the children and adolescents prior to the pandemic in China. However, no data on the prevalence of anxiety and posttraumatic stress symptoms were found among children and adolescents prior to the pandemic in China, thus, no comparisons could be made. Social isolation, school closures, and socioeconomic effects of the policies (increasing unemployment, financial insecurity, and poverty) during the COVID-19 pandemic have been reported to contribute to the mental health problems among children and adolescents (Holmes et al., 2020; Lee, 2020). While there was some research on the psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS) on patients and health-care workers, such evidence in children and adolescents is scarce (Lee, 2020). Therefore, no direct comparison of the prevalence of mental health problems with previous pandemics could be made. However, COVID-19 is much more widespread than SARS, MERS, and other previous epidemics. As the pandemic continues, monitoring young people's mental health status over the long term and implementation of interventions and policies to support them are urgent and important.

Our study revealed that sleep disorders and posttraumatic stress symptoms were the most severe mental health problems among children and adolescents, and about half of them experienced these disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has a substantial impact on young people's sleep. Many children and adolescents may be exposed to unconstrained sleep schedules, prolonged screen exposure, and limited access to outdoor activities and peer interactions and these could have contributed to reported sleep disorders (Liu et al., 2020). Sleep disturbances are often a precursor to other more severe mental problems and it is necessary and urgent to disseminate sleep health education and sleep hygiene behavior interventions to children and adolescents (Lin et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic event, and it is well known that surviving critical illness can induce posttraumatic stress symptoms (Vindegaard and Benros, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic may be an independent factor that cause posttraumatic stress symptoms in children and adolescents. Children might also be exposed to greater interpersonal violence and abuse, and this too might contribute to the high prevalence. However, the evidence is limited as only two studies reported on posttraumatic stress symptoms in this age group.

The subgroup meta-analysis revealed that the prevalence of depression and anxiety may be higher among adolescents and females. The higher prevalence among female reflects the already established gender gap for anxiety and depressive symptoms (Pappa et al., 2020). Again, adolescents exhibited much higher prevalence estimates both for depression and anxiety compared to younger children in our study. This may attribute to education is highly valued and regarded as the main path to success in traditional Chinese culture (Hou et al., 2020). As adolescents face the most important tests of their lives (e.g., the college or high school entrance examination), the uncertainty and potential negative effects on academic development of prolonged school closure had more adverse effects on adolescents than children (Zhou et al., 2020), thus, adolescents had more depressive and anxiety symptoms. However, no subgroup meta-analysis based on age and gender could be conducted for sleep disorders and posttraumatic stress symptoms, because there is no data available. Future such studies should take the potential modifying effects of age and gender into consideration.

No subgroup meta-analysis based on preexisting conditions and country could be conducted in this study. Only two studies included were conducted among children and adolescents with preexisting conditions (i.e., Autism Spectrum Disorder and Cystic Fibrosis). However, the two studies were not used for meta-analysis because they did not report the prevalence of mental health problems. All the studies included in our meta-analysis were from China. In our review, only two studies included were conducted in other countries (i.e., Turkey). However, the two studies from Turkey did not report the prevalence of mental health problems, thus they were not included in the meta-analysis. Though the fact that China was severely affected, our findings may provide a reliable indication of the effects of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children and adolescents globally. However, considering the severity of COVID-19, economic status, and healthcare systems vary greatly between countries, more such studies from other countries are warranted.

We found that the most frequently used scale to measure depression and anxiety were PHQ-9 (3 of 13) and GAD-7 (5 of 12), respectively. However, each of the two studies used a different scale to measure sleep disorders and posttraumatic stress symptoms. The PHQ-9 is a simple, widely used, and highly effective self-assessment tool for depressive symptoms during the last 2 weeks (Kroenke et al., 2001). GAD-7 measured seven anxiety symptoms that bothered participants during the last 2 weeks (Zhou et al., 2020). Both PHQ-9 and GAD-7 are widely used among children and adolescents. Using the same scale and cutoff point for specific mental health problems could be better for comparison across studies.

This study has several limitations. First, all the studies included in meta-analysis were conducted in China, thus, the generalizability of findings to other countries is limited. Moreover, most of the studies used online survey method and nonprobability sampling, which further limit its generalizability. Second, a variety of assessment scales were utilized to measure mental health problems and different cut-offs were used even though several studies used the same tests. Third, due to the limited number of studies, we could not explore the potential modifying effects of preexisting conditions and country on the prevalence of mental health problems. Fourth, only two studies focused on children age <6 years were included; thus, the mental health status of these children warrants further research.

To advance research in this area, future studies target children and adolescents are warranted to improve the following aspects. First, longitudinal studies to examine the long-term implications of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health are needed. Second, further studies to examine the prevalence of sleep disorders and posttraumatic stress symptoms are needed. Third, besides the general children and adolescents, more studies are needed to focus on children and adolescents with preexisting conditions, such as chronic diseases and psychiatric conditions. Fourth, studies from countries other than China are needed to provide insight on the global impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health.

Despite its limitations, this study is the first to examine the pooled prevalence of depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and posttraumatic stress symptoms among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. We conducted comprehensive literature search based on both English and Chinese databases, the findings have important clinical and public health implications. Furthermore, our subgroup analysis of depression and anxiety based on age and gender provided additional valuable insights of potential particular vulnerabilities.

In conclusion, our study highlighted the high prevalence of depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and posttraumatic stress symptoms among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic, in particular, among the females and adolescents. Further research is needed to identify strategies for preventing and treating these disorders in this population.

Funding

The project is supported in part by research grants from the China Medical Board [Grant number: 16-262], the University Alliance of the Silk Road [Grant number: 2020LMZX002], and Xi'an Jiaotong University Global Health Institute. The funding sources had no role in the design of this study, its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results.

Authors' contribution

The authors's responsibilities were as follows: YFW and WDW designed the research; LM and MM wrote the protocol; KL, SQC and HXZ managed the literature searches and selection; RK and KL performed data extraction; NY performed verification of data extraction, YXL performed meta-analysis; SQC assessed the quality of the included articles; LM wrote the first draft of the manuscript; ML, AR, and MM revised the manuscript; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.021.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Allgaier AK, Frühe B, Pietsch K, Saravo B, Baethmann M, Schulte-Körne G. Is the children’s depression inventory Short version a valid screening tool in pediatric care? A comparison to its full-length version. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012 Nov;73(5):369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behav. Res. Ther. 1996 Aug;34(8):669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Zheng D, Liu J, Gong Y, Guan Z, Lou D. Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;88:36–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen IH, Chen CY, Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD, Lin CY. Internet-related behaviors and psychological distress among schoolchildren during COVID-19 school suspension. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Compton SN, Keeler G, Angold A. Relationships between poverty and psychopathology: a natural experiment. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2023–2029. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale - revised. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003 Dec;41(12):1489–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L, Shao X, Wang Y, Huang Y, Miao J, Yang X, Zhu G. An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID-19. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;275:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunstan DA, Scott N. Norms for Zung’s self-rating anxiety scale. BMC Psychiatry. 2020 Feb 28;20(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2427-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon C, Bélanger L, Ivers H, Morin CM. Validation of the insomnia severity index in primary care. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2013 Nov-Dec;26(6):701–710. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.06.130064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golberstein E, Wen H, Miller BF. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, Ballard C, Christensen H, Cohen Silver R, Everall I, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou TY, Mao XF, Dong W, Cai WP, Deng GH. Prevalence of and factors associated with mental health problems and suicidality among senior high school students in rural China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;54 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivarsson T, Lidberg A, Gillberg C. The Birleson Depression Self-Rating Scale (DSRS). Clinical evaluation in an adolescent inpatient population. J. Affect. Disord. 1994 Oct;32(2):115–125. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Hennessy EA. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the health sciences: best practice methods for research syntheses. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019;233:237–251. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(6):421. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HC, Chung OK, Ho KY. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for Children: psychometric testing of the Chinese version. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010 Nov;66(11):2582–2591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SW, Wang Y, Yang YY, Lei XM, Yang YF. Analysis of influencing factors of anxiety and emotional disorder in children and adolescents isolated at home during the epidemic of new coronavirus pneumonia. Chin. J. Child Health Care. 2020;28(04):407–410. [Google Scholar]

- Lin LY, Wang J, Ou-Yang XY, Miao Q, Chen R, Liang FX, Zhang YP, Tang Q, Wang T. The immediate impact of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak on subjective sleep status. Sleep Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Luo WT, Li Y, Li CN, Hong ZS, Chen HL, Xiao F, Xia JY. Psychological status and behavior changes of the public during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2020;9(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00678-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Tang H, Jin Q, Wang G, Yang Z, Chen H, Yan H, Rao W, Owens J. Sleep of preschoolers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak. J. Sleep Res. 2020:e13142. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Jiang W, Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo DM, Yan JW, Li X, Liu S, Guo PF, Hu SW, Zhong H. Detection rate and influencing factors of anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents under the new crown pneumonia epidemic. Sichuan Ment. Health. 2020;33(03):202–206. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monga S, Birmaher B, Chiappetta L, Brent D, Kaufman J, Bridge J, Cully M. Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): convergent and divergent validity. Depress. Anxiety. 2000;12(2):85–91. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:2<85::AID-DA4>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman SA, Luft MJ, Schroeder HK, Varney ST, Fleck DE, Barzman DH, Gilman R, DelBello MP, Strawn JR. The generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder: signal detection and validation. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry. 2017 Nov;29(4):227–234A. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn GD. Concurrent validity between the Nowicki-Strickland locus of control scale and the state-trait anxiety inventory for children. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1988;48(2):435–438. [Google Scholar]

- Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pınar Senkalfa B, Sismanlar Eyuboglu T, Aslan AT, Ramaslı Gursoy T, Soysal AS, Yapar D, İlhan MN. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety among children with cystic fibrosis and their mothers. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020;55(8):2128–2134. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H, Liu R, Chen X, Yuan XF, Li YQ, Huang HH, Zheng Y, Wang G. Prevalence of anxiety and associated factors for Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1111/pcn.13102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M, Zhou SJ, Guo ZC, Zhang LG, Min HJ, Li XM, Chen JX. The effect of social support on mental health in chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. J. Adolesc. Health: Off. Public. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao WW, Xu DD, Cao XL, Wen SY, Che WI, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, He F, Xiang YT. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents in China: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:790–796. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson LP, McCauley E, Grossman DC, McCarty CA, Richards J, Russo JE, Rockhill C, Katon W. Evaluation of the patient health questionnaire-9 item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010 Dec;126(6):1117–1123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, Pollak TA, McGuire P, Fusar-Poli P, Zandi MS, Lewis G, David AS. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):611–627. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevin JA, Matson JL, Coe DA, Fee VE, Sevin BM. A comparison and evaluation of three commonly used autism scales. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1991 Dec;21(4):417–432. doi: 10.1007/BF02206868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprang G, Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2013;7(1):105–110. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Study Quality Assessment Tools 2021 https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools.

- Su LY, Wang K, Zhu Y, Luo XR, Yang ZW. Norm of the depression self-rating scale for children in chinese urban children. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2003;(08):547–549. [Google Scholar]

- Tan TX, Wang Y, Cheah CSL, Wang GH. Reliability and construct validity of the Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire in Chinese kindergartners. Sleep Health. 2018 Feb;4(1):104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W, Hao F, McIntyre RS, Jiang L, Jiang X, Zhang L, Zhao X, Zou Y, Hu Y, Luo X, et al. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L, Ying B. Investigation and analysis of middle school students’ mental health status and influencing factors during the new coronary pneumonia epidemic. Ment. Health Educ. Primary Secondary Sch. 2020;(10):57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tang S, Pang HW. Anxiety and depression of children and adolescents during the new crown pneumonia epidemic. Ment. Health Educ. Primary Secondary Sch. 2020;(19):15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Türkoğlu S, Uçar HN, Çetin FH, Güler HA, Tezcan ME. The relationship between chronotype, sleep, and autism symptom severity in children with ASD in COVID-19 home confinement period. Chronobiol. Int. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2020.1792485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JS, Li Y, He ES. Development and standardization of mental health scale for middle school students in China. Psychosoc. Sci. 1997;4:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Shi HS, Geng FL, Zou LQ, Tan SP, Wang Y, Neumann DL, Shum DH, Chan RC. Cross-cultural validation of the depression anxiety stress scale-21 in China. Psychol. Assess. 2016 May;28(5):e88–e100. doi: 10.1037/pas0000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Meng Q, Liu L, Liu J. Reliability and validity of the spence children’s anxiety scale for parents in Mainland Chinese children and adolescents. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2016 Oct;47(5):830–839. doi: 10.1007/s10578-015-0615-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang NX, Xu PF. Investigation and research on adolescents’ psychological stress and coping styles during the new coronary pneumonia. J. Dali Univ. 2020;5(07):123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Yang YY, Li SW, Lei XM, Yang YF. Investigation of depression among children and adolescents at home during the epidemic of novel coronavirus pneumonia and analysis of influencing factors. Chin. J. Child Health. 2020;28(03):277–280. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao D, Guo L, Zhao M, Zhang S, Li W, Zhang WH, Lu C. Effect of sex on the association between nonmedical use of opioids and sleep disturbance among Chinese adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16(22) doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Xue Q, Zhou Y, Zhu K, Liu Q, Zhang J, Song R. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu QX, Zeng YM, Lu WJ. Investigation and analysis of the mental health of middle school students during the period of the new crown pneumonia epidemic. Jiangsu Educ. 2020;(32):44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhuang LY, Yang W. Survey of symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in middle school students during the COVID-19 pandemic: taking Chengdu Shude Middle School as an example. Educ. Sci. Forum. 2020;(17):45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZJ. China Medical Electronic Audiovisual Publishing House; Beijing: 2005. Handbook of Behavioral Medicine Scale[M] pp. 267–270. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Yuan X, Qi H, Liu R, Li Y, Huang H, Chen X, Wang G. Prevalence of depression and its correlative factors among female adolescents in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. Globalization Health. 2020;16(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00601-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SJ, Zhang LG, Wang LL, Guo ZC, Wang JQ, Chen JC, Liu M, Chen X, Chen JX. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2020;29(6):749–758. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu KH, Zhou Y, Xie XY, Wu H, Xue Q, Liu Q, Wan ZH, Song RR. Anxiety status of primary school students in Hubei Province during the new crown pneumonia epidemic and its influencing factors. Chin. Public Health. 2020;36(05):673–676. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.