To the editor,

Peaking of SARS-CoV-2 viral shedding usually correlates with high infectiousness.1 Despite of early awareness of prevalent presymptomatic viral shedding that may evade control measures and drive stealth transmission,2 SARS-CoV-2 viral kinetics during presymptomatic stage or asymptomatic infections was still poorly understood due to requiring repeated tests in asymptomatic population. SARS-CoV-2 omicron infections were more likely to be asymptomatic or milder comparing to delta infections,3, 4, 5 which were associated with shifting virological characteristics of omicron in animal models,6, 7, 8 and might offer key evolutionary advantage over prior variants.9

Here, we provided evidence of peak viral shedding at presymptomatic stage and during asymptomatic omicron infections by analyzing viral RNA kinetics during the entire infection course. 1,085 SARS-CoV-2 PCR-positive cases in Guang'an city of western China, who were admitted to West China Guang'an Hospital between 2022/5/9 and 2022/6/3 were enrolled in this study. Characteristics of the cohort were summarized in Table 1 . Methods of population screening for omicron infections and in-hospital procedures including PCR testing and symptom monitoring were detailed in the Supplementary Materials. The human study protocols have been approved by West China Guang'an Hospital and all patient identifications were replaced by anonymous codes during abstraction as stipulated by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort.

| All cases (n = 1085) |

Asymptomatic (n = 766) |

Symptomatic (n = 319) |

P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 43 (17–56) | 42 (16–55) | 47 (18–57) | .039 |

| <18, n (%) | 291 (26.8) | 215 (28.1) | 76 (23.8) | .079 |

| 18–59, n (%) | 606 (55.9) | 430 (56.1) | 176 (55.2) | |

| ≥60, n (%) | 188 (17.3) | 121 (15.8) | 67 (21.0) | |

| Female sex at birth, n (%) | 652 (60.1) | 443 (57.8) | 209 (65.5) | .021 |

| Days of RNA-positive, median (IQR) | 13 (11–17) | 13 (10–17) | 14 (11–17) | .049 |

| Days from first RNA-positive to symptom onset, median (IQR) [n] | 0 (0–4) [319] | / | 0 (0–4) [319] | / |

| Days from first RNA-positive to peak RNA load, median (IQR) [n] | 3 (2–5) [298] | 3 (2–5) [222] | 3 (2–5) [76] | .583 |

| Vaccination status, n (%) | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 29 (2.7) | 18 (2.4) | 11 (3.5) | .063 |

| Partial vaccination | 9 (0.8) | 3 (0.4) | 6 (1.9) | |

| Full vaccination without booster | 346 (31.9) | 248 (32.4) | 98 (30.8) | |

| Full vaccination with booster | 699 (64.4) | 496 (64.8) | 203 (63.8) | |

| Unknown | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Days from last vaccination to first RNA-positive, median (IQR) [n] | 152 (133–265) [782] | 152 (137–258) [524] | 151 (128–267) [258] | .916 |

| COVID-19 severity, n (%) | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 766 (70.6) | 766 (100) | 0 (0) | / |

| Mild | 319 (29.4) | 0 (0) | 319 (100) | |

| COVID-19 symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| Respiratory | 285 (26.3) | 0 (0) | 285 (90.5) | / |

| Neuromuscular | 75 (6.9) | 0 (0) | 75 (23.8) | / |

| Gastrointestinal | 17 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 17 (5.4) | / |

| Other | 4 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.3) | / |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Respiratory disorders | 13 (1.2) | 8 (1.0) | 5 (1.6) | .541 |

| Cardiovascular disorders | 96 (8.8) | 67 (8.8) | 29 (9.1) | .907 |

| Metabolic disorders | 31 (2.9) | 22 (2.9) | 9 (2.8) | 1.00 |

| Immune disorders | 7 (0.6) | 3 (0.4) | 4 (1.3) | .204 |

| Other infectious diseases | 11 (1.0) | 8 (1.0) | 3 (0.9) | 1.00 |

| Cancer | 12 (1.1) | 6 (0.8) | 6 (1.9) | .122 |

| Other | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0) | .560 |

Categorical variables were assessed by Fisher's exact test or Chi-square test and continuous variables were assessed by Mann-Whitney U test. Tests were performed between asymptomatic and symptomatic groups. Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range.

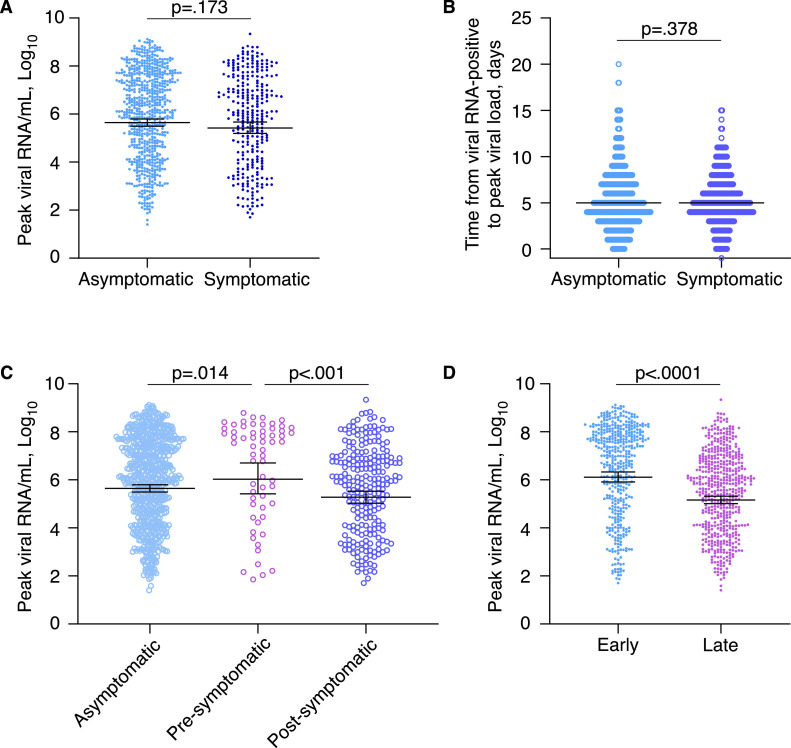

Guang'an reported no prior SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks and >95% vaccine coverage. Patient zero with asymptomatic infection of omicron BA.2.2 sub-variant arrived in Guang'an on 2022/5/4 and was the index of and outbreak that lead to more than 1,000 cases despite early interventions (Fig. S1). Viral RNA kinetics of 962 cases showed prevalent asymptomatic and presymptomatic peaks (Fig. S2). 69% (668/962) of them, who were asymptomatic till the end of follow-up, showed comparable peak viral RNA levels (geometric mean 4.4 × 105 vs 2.7 × 105 copies/ml, p=.173) and peak timing (median 5 vs 5 days, p=.378) with symptomatic cases (Fig. 1A and B).

Interestingly, 21% (61/294) symptomatic cases showed pre-symptomatic peaking of viral RNA, which were rarely seen in pre-alpha and alpha variant infections,1 with higher peak viral loads than other symptomatic (geometric mean 1.1 × 106 vs 1.9 × 105 copies/ml, p<.001) or asymptomatic cases (geometric mean 1.1 × 106 vs 4.4 × 105 copies/ml, p=.014) (Fig. 1 C). Simultaneous or post-symptomatic peaks were dominant in pre-alpha and alpha variant infections,1 whereas they were less common in early-stage (≤5 days post-lockdown, 41/83) than late-stage omicron cases in our cohort (192/211, p<.0001).

Fig. 1.

Peak viral RNA loads and timing according to symptomatic status or stage of outbreak.

(A,B) Comparison of peak viral RNA levels (A) and time from viral RNA-positive to peak viral RNA (B) between asymptomatic (n = 668) and symptomatic cases (n = 294). Lines indicate geometric means ± 95% confidence intervals (A) or medians (B). Viral RNA concentration was calculated based on the Ct value of Orf1ab gene as described in the Supplementary Materials. Lower limit of viral RNA concentration was set at 19 copies/mL, which corresponded to cut-off Ct value of 38 for Orf1ab gene. (C) Comparison of peak viral RNA levels between asymptomatic (n = 668), pre-symptomatic peaking (n = 61) and post-symptomatic peaking cases (n = 233). The pre-symptomatic and post-symptomatic peaking cases together made the symptomatic group in (A). Lines indicate geometric means ± 95% confidence intervals. (D) Comparison of peak viral RNA levels between early- (≤5 days after lockdown, n = 436) and late-stage cases (n = 526). Lines indicate geometric means ± 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was assessed by Mann-Whitney U tests.

Intriguingly, late-stage infections had lower peak viral loads (geometric mean 1.3 × 106 vs 1.5 × 105 copies/ml, p<.0001) at the time of increased preventive measures (Fig. 1D), whereas among those infected, vaccination was not associated with peak viral load, duration of viral clearance, or symptomatic disease (Fig. S3). Of note, endocrine disorders such as diabetes were associated with higher peak viral loads, whereas chronic infections such as HBV infections were also associated with higher peak viral loads despite of not reaching statistical significance due to small number of positive cases (Fig. S3).

These findings together provided evidence of an early and asymptomatic window of infectiousness during some omicron infections. Such front-loaded infectiousness of omicron poses significant challenges to pandemic control policies, and measure undertaken earlier were less likely to be effective in this circumstance. Symptom-based testing and extended quarantine used to be an effective strategy to block SARS-CoV-2 transmission in pre-omicron era due to the long infectious window post-symptom onset.10 However, ongoing epidemic in countries with strict COVID-19 policies suggested that omicron carriers may already spread infections before being quarantined,10 which had exactly happened in Guang'an and could only be contained by early detection and interventions. Hopefully, upcoming omicron-adapted vaccines could control the pandemic; otherwise, more efficient and cost-effective screening techniques for asymptomatic population might be needed for future variants with high virulence.

Role of the funding source

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 82072862 and 82272949 to YX).

Author contributions

LJ abstracted case information and did clinical investigations; LT did epidemiological investigations and statistical analysis; LZ, SY and WC collected PCR Ct values; YZhu analyzed viral kinetics and interpreted findings; YF did survey of Guang'an residents; XY, SY, YZheng and YX interpreted findings and did investigations; PH conceived the study, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. No authors were precluded from accessing data in the study, and they accept responsibility to submit for publication. All authors participate in the revision of the manuscript and approve the final manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2022.11.026.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Hakki S., Zhou J., Jonnerby J., Singanayagam A., Barnett J.L., Madon K.J., et al. Onset and window of SARS-CoV-2 infectiousness and temporal correlation with symptom onset: a prospective, longitudinal, community cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(11):1061–1073. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00226-0. NovPubMed PMID: 35988572. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC9388060. Epub 20220818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He X., Lau E.H.Y., Wu P., Deng X., Wang J., Hao X., et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):672–675. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. MayPubMed PMID: 32296168. Epub 20200415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olaiz-Fernandez G., Vicuna de Anda F.J., Diaz-Ramirez J.B., Fajardo Dolci G.E., Bautista-Carbajal P., Angel-Ambrocio A.H., et al. Effect of Omicron on the prevalence of COVID-19 in international travelers at the Mexico city international airport. December 16th, 2021 to January 31st, 2022. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2022;49 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102361. May 29PubMed PMID: 35640809. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC9148423. Epub 20220529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nyberg T., Ferguson N.M., Nash S.G., Webster H.H., Flaxman S., Andrews N., et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet. 2022;399(10332):1303–1312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00462-7. Apr 2PubMed PMID: 35305296. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC8926413. Epub 20220316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iuliano A.D., Brunkard J.M., Boehmer T.K., Peterson E., Adjei S., Binder A.M., et al. Trends in disease severity and health care utilization during the early Omicron variant period compared with previous SARS-CoV-2 high transmission periods - United States, December 2020-January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(4):146–152. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7104e4. Jan 28PubMed PMID: 35085225. Epub 20220128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan S., Ye Z.W., Liang R., Tang K., Zhang A.J., Lu G., et al. Pathogenicity, transmissibility, and fitness of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron in Syrian hamsters. Science. 2022;377(6604):428–433. doi: 10.1126/science.abn8939. Jul 22PubMed PMID: 35737809. Epub 20220623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki R., Yamasoba D., Kimura I., Wang L., Kishimoto M., Ito J., et al. Attenuated fusogenicity and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Nature. 2022;603(7902):700–705. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04462-1. MarPubMed PMID: 35104835. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC8942852. Epub 20220201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shuai H., Chan J.F., Hu B., Chai Y., Yuen T.T., Yin F., et al. Attenuated replication and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 Omicron. Nature. 2022;603(7902):693–699. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04442-5. MarPubMed PMID: 35062016. Epub 20220121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkhout B., Herrera-Carrillo E. SARS-CoV-2 evolution: on the sudden appearance of the Omicron variant. J Virol. 2022;96(7) doi: 10.1128/jvi.00090-22. Apr 13PubMed PMID: 35293771. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC9006888. Epub 20220316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mefsin Y.M., Chen D., Bond H.S., Lin Y., Cheung J.K., Wong J.Y., et al. Epidemiology of infections with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2 variant, Hong Kong, January-March 2022. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28(9):1856–1858. doi: 10.3201/eid2809.220613. SepPubMed PMID: 35914518. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC9423929. Epub 20220801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.