Abstract

Background

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) after COVID-19 shares clinical similarities to Kawasaki disease (KD). We sought to determine whether cardiac biomarker levels differentiate MIS-C from KD and their association with cardiac involvement.

Methods

Subjects included 38 MIS-C patients with confirmed prior COVID-19 and 32 prepandemic and 38 contemporaneous KD patients with no evidence of COVID-19. Patient, clinical, echocardiographic, electrocardiographic, and laboratory data timed within 72 hours of cardiac biomarker assessment were abstracted. Groups were compared, and regression analyses were used to determine associations between biomarker levels, diagnosis and cardiac involvement, adjusting for clinical factors.

Results

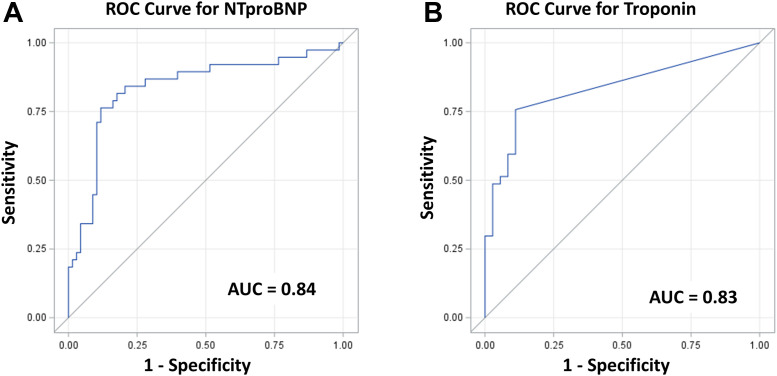

MIS-C patients had fewer KD clinical features, with more frequent shock, intensive care unit admission, inotrope requirement, and ventricular dysfunction, with no difference regarding coronary artery involvement. Multivariable regression analysis showed that both higher N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and cardiac troponin I (TnI) were associated with MIS-C vs KD, after adjusting for significant covariates. Receiver operating characteristic curves for diagnosis showed that any detectable TnI greater than 10 ng/L was predictive of MIS-C vs KD with 91% sensitivity and 76% specificity. NT-proBNP > 2000 ng/L predicted MIS-C vs KD with 82% sensitivity and 82% specificity. Higher TnI but not NT-proBNP was associated with lower LV ejection fraction. Neither biomarker was associated with coronary artery involvement.

Conclusions

Positive TnI and higher NT-proBNP may differentiate MIS-C from KD, which may become more relevant as evidence of prior COVID-19 becomes more challenging to determine. Cardiac biomarkers may have limited associations with cardiac involvement in this setting.

Résumé

Contexte

Le syndrome inflammatoire multisystémique chez les enfants (SIME) lié à la COVID-19 partage des caractéristiques cliniques avec la maladie de Kawasaki (MK). Nous avons tenté de déterminer si les concentrations de biomarqueurs cardiaques permettent de différencier le SIME de la MK et d’établir un lien avec l’atteinte cardiaque.

Méthodologie

La population à l’étude comprenait 38 patients atteints du SIME ayant eu une infection confirmée par la COVID-19, et 32 et 38 patients ne présentant aucun signe de COVID-19 atteints de la MK respectivement avant la pandémie et au moment de l’analyse. Les caractéristiques des patients, les données cliniques, échocardiographiques et électrocardiographiques, et les analyses de laboratoire réalisées dans les 72 heures de l’évaluation des taux de biomarqueurs cardiaques ont été obtenues. Les groupes ont été comparés, et des analyses de régression ont été utilisées pour déterminer les corrélations entre les taux de biomarqueurs, le diagnostic et l’atteinte cardiaque, avec correction pour les facteurs cliniques.

Résultats

Chez les patients atteints du SIME, on retrouvait moins de signes cliniques de la MK, mais davantage de chocs cardiogéniques, d’admissions aux soins intensifs, de dépendance aux médicaments inotropes et de dysfonction ventriculaire. Il n’y avait pas de différence entre les groupes quant à l’atteinte de l’artère coronaire. L’analyse de régression multivariée montre qu’un taux élevé de propeptide natriurétique de type B N-terminal (NT-proBNP) et de troponine I (TnI) cardiaque est associé au SIME plutôt qu’à la MK, après correction pour les co-variables d’importance. Les courbes de fonction d’efficacité du récepteur pour le diagnostic ont montré que tout taux détectable de TnI au-dessus de 10 ng/L était un facteur prédictif du SIME, plutôt que de la MK, avec une sensibilité de 91 % et une spécificité de 76 %. Un taux de NT-proBNP > 2000 ng/L était un facteur prédictif du SIME avec une sensibilité de 82 % et une spécificité de 82 %. Un taux plus élevé de TnI était associé à une fraction d’éjection du ventricule gauche plus basse, ce qui n’était pas le cas d’un taux élevé de NT-proBNP. Aucun des deux biomarqueurs n’était associé à l’atteinte de l’artère coronaire.

Conclusions

La présence de TnI et un taux élevé de NT-proBNP pourraient permettre de différencier le SIME de la MK. Le dosage de ces protéines pourrait devenir plus pertinent avec la difficulté croissante de déceler une infection antérieure à la COVID-19. Les biomarqueurs cardiaques pourraient avoir des associations limitées avec l’atteinte cardiaque dans ce contexte.

Early in the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, children were thought to have asymptomatic or less severe illness when infected. However, it soon became evident that some children were manifesting a novel and delayed multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C) after infection.1 , 2 The clinical presentation of MIS-C resembles Kawasaki disease (KD). However, it became clear that MIS-C was clinically distinct, resulting in the development of a case definition from the World Health Organisation (WHO).3 The WHO case definition was understandably broad and focused primarily on the major organ systems that seem to be affected by MIS-C: cardiac, hematologic (coagulopathy), and gastrointestinal. The WHO’s and subsequent other case definitions have had considerable overlap with the case definition for KD.4

In addition to echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, cardiac biomarkers, specifically cardiac troponin I (TnI) and N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), have been used as biomarkers of cardiac involvement. For adults, both TnI and NT-proBNP have been validated for diagnosis and monitoring of ischemic cardiac injury5 and heart failure.6 Their role in the diagnosis and management of KD has been variable,7 and they are not generally recommended.8 However, abnormalities of both NT-proBNP and TnI have been described in the setting of MIS-C.9

Because of the similarities between MIS-C and KD in their clinical presentation and course, and possibly pathophysiology,10, 11, 12 these cardiac biomarkers have more recently been assessed in children and adolescents in this clinical setting.13 However, there is limited understanding as to their role in diagnosis, monitoring, and prognosis of MIS-C vs KD. Therefore, we sought to determine 1) how elevations of TnI and NT-proBNP are associated with clinical, biochemical, electrocardiographic, and/or echocardiographic changes in patients with KD vs MIS-C, and 2) how TnI or NT-proBNP may help differentiate KD from MIS-C.

Methods

Study design and population

This was a single-centre retrospective cohort study approved by the institutional research ethics board under a waiver of consent. Three groups of patients were reviewed: 1) patients with complete and incomplete KD diagnosed before January 1, 2020, according to the American Heart Association (AHA) 2017 guideline criteria8 (PreKD) and who had a stored blood samples obtained before treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) from which NT-proBNP could be assessed (insufficient sample volume to assess TnI); 2) patients with complete and incomplete KD diagnosed from January 1, 2020, to March 31, 2021, who had no evidence of SARS-CoV-2 exposure and did not meet criteria for MIS-C according to the WHO case definition (PostKD); and patients from January 1, 2020, to March 31, 2021, who were diagnosed with MIS-C according to WHO criteria with confirmed preceding SARS-CoV-2 (any of test-confirmed household exposure, positive PCR, positive serology). For PreKD patients, biospecimens were obtained via SickKids COVID Biobank (REB# 1000070060, BEAT KD REB# 1000043263). All patients in the PostKD and MIS-C groups who had blood work including assessment of NT-proBNP and TnI and who had an echocardiogram within 72 hours of that assessment were included.

Measurements

Information regarding demographics, clinical presentation and findings, laboratory and cardiac imaging assessments, electrocardiography (ECG), infectious disease assessment, management ,and outcomes were abstracted from the medical record. Biosamples were obtained in treatment-naïve patients before administration of immunomodulatory therapy in all patient groups. Standardised and uniform preanalytical operating processes were applied to all sample collections, processing, and storage. Plasma was obtained from P100 blood collection tubes with spray-dried anticoagulant (K2EDTA) and proprietary protease inhibitors (Becton and Dickson Bioscience) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Once processed, samples were stored at −80°C in 200-μL aliquots at the SickKids COVID-19 biobank at The Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, ON). The Abbott Architect analyser was used to test for high-sensitivity TnI and NT-proBNP. Level of detection for NT-proBNP was 5 ng/L with a measuring range of 5 ng/L to 35 000 ng/L, and for data analysis purposes levels > 35,000 ng/L were arbitrarily set to 35,001 ng/L. Level of detection for TnI was 10 ng/L, and for data analysis purposes levels < 10 ng/L were arbitrarily set to 0.001 ng/L. Institutional normal values for TnI were < 10 ng/L and for NT-proBNP were < 125 ng/L. In the event that there were multiple assessments of TnI and NT-proBNP on the same day as an echocardiogram, the most abnormal value was selected for analysis. From the ECGs obtained closest to the blood sample, basic intervals (PR, QRS duration, QT, QTc), heart rate, presence of arrhythmia, presence of T-wave abnormalities, and index of cardiac electrophysiologic balance (QT or QTc/QRSd) were collected from finalised ECG reports. Ventricular functional indices and quantitative and qualitative assessment of the coronary arteries were abstracted from echocardiogram reports. All echocardiograms were obtained with the use of a standardised institutional protocol. Coronary artery dimensions were converted to body surface area–adjusted z scores,14 and coronary artery involvement was classified according to the criteria of the AHA guidelines.8 Because detailed time course of body temperature changes were not available, for practical purposes intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) resistance was defined by the patient having received after an initial dose of IVIG a second dose of IVIG or second-line therapies (eg, immunomodulators). If IVIG and corticosteroids were given concomitantly as initial therapy, IVIG resistance was then defined by the patient having received subsequent second dose of IVIG or second-line therapies.

Data analysis

Data are described as frequencies, means with standard deviations, and medians with interquartile ranges, as appropriate to the level of measurement and the distribution of values for a given variable. Comparisons of features between PreKD and PostKD groups and between all KD and MIS-C groups were performed. Categoric variables between groups were compared by means of Fisher’s exact test and Mantel-Haenszel chi-square analysis. Normally distributed variables were compared by means of Student’s t test. Highly skewed continuous variables were compared with the use of Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance. Statistical significance was set at a P < 0.05. Clinical status, laboratory values, and cardiac assessment closest to the time of measurement of TnI and NT-proBNP, but no greater than 72 hours away, were compared between diagnostic groups with the use of generalised linear regression models. Because the distribution of values of cardiac biomarkers was highly skewed, the logarithm of the values was used to normalise the distribution and was used in all regression analyses. SAS statistical software Version 9.4 (Cary, NC) was used for analyses, with P < 0.05 set as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

Comparison of KD patients before and after January 1, 2020

There were 32 patients with KD included from before January 1, 2020 (PreKD), and 36 patients after January 1, 2020 (PostKD). Details and comparison of their characteristics are summarised in Table 1 . PreKD patients were more likely to have complete KD criteria with a greater number of diagnostic features than PostKD patients. The likelihood of admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) was lower for preKD patients, the length of stay in both the ICU and hospital overall was shorter, and their bloodwork at cardiac biomarker assessment showed higher white blood cell count and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels. From a cardiac perspective, there were no significant differences between PreKD and PostKD patients regarding NT-ProBNP levels or findings from electrocardiography and echocardiography. PostKD patients were more likely to have received enteral corticosteroids than PreKD patients, although the proportion with IVIG resistance was similar between groups.

Table 1.

Demographic, biochemical, and cardiologic characteristics of pre- and postpandemic patients with acute Kawasaki disease (KD)

| Prepandemic KD (n = 32) | Postpandemic KD (n = 36) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 3.3 (1.2-11.5) | 3 (0.4-15.8) | > 0.99 |

| Sex, male/female | 20/12 | 21/15 | 0.73 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 15.5 ± 1.7 | 18.2 ± 6.6 | 0.03 |

| Body mass index z score | −0.6 ± 1.6 | −0.1 ± 1.6 | 0.19 |

| Clinical course | |||

| Days of fever | 7 (4-12) | 6 (3-18) | 0.44 |

| No. of KD clinical features | 5 (3-5) | 3 (1-5) | < 0.001 |

| Conjunctivitis | 31 (97) | 27 (75) | 0.01 |

| Cervical lymphadenopathy | 20 (63) | 11 (31) | 0.008 |

| Rash | 30 (94) | 22 (61) | 0.001 |

| Extremity changes | 30 (94) | 22 (61) | 0.001 |

| Oral mucosal changes | 30 (94) | 28 (78) | 0.06 |

| KD diagnosis | < 0.001 | ||

| Complete | 28 (88) | 11(31) | |

| Incomplete | 4 (12) | 25 (69) | |

| Shock | 1 (3) | 4 (11) | 0.2 |

| Intensive care requirements | |||

| Admission to ICU | 1 (3) | 3 (8) | 0.36 |

| Length of ICU stay, days | 0 (0-1) | 3 (2-5) | < 0.001 |

| Inotropic support | 0 | 0 | > 0.99 |

| Total hospital length of stay, days | 3 (2-7) | 4 (3-18) | 0.002 |

| Treatment | |||

| Days from admission to first immunomodulatory treatment | 0 (0-1) | 1 (1-5) | < 0.001 |

| IVIG | 32 (100%) | 31 (86%) | 0.03 |

| Corticosteroids, intravenous | 2 (6%) | 11 (31%) | 0.01 |

| Corticosteroids, oral | 3 (9%) | 20 (56%) | < 0.001 |

| Immunomodulating agents | 0 | 2 (6%) | 0.17 |

| IVIG resistance | 9 (28%) | 3 (8%) | 0.06 |

| Biochemistry | |||

| Days from admission to assessment | 0 (−1 to 0) | 1 (0-7) | < 0.001 |

| Troponin I, ng/L | – | 0 (0-88.5) | – |

| NT-proBNP, ng/L | 718 (35-8615) | 562 (41-14573) | 0.99 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 94.4 (3.7-288) | 93.7 (7.9-381.7) | 0.72 |

| Ferritin, μg/L | – | 182.1 (41.2-6936) | – |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, mm/h | 73 ± 28 | 59 ± 33 | 0.06 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 112 ± 12 | 108 ± 12 | 0.18 |

| Mean corpuscular volume, fL | 78.6 ± 5.9 | 79 ± 5 | 0.76 |

| White blood cells, ×10ˆ9/L | 14.9 ± 6 | 11.6 ± 5.5 | 0.02 |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 308 ± 96 | 311 ± 146 | 0.94 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 29 ± 8 | 33 ± 26 | 0.46 |

| Albumin, g/L | 37 ± 5 | 34 ± 8 | 0.17 |

| Alanine transaminase, U/L | 39 (10-281) | 26 (12-252) | 0.04 |

| International normalised ratio | – | 1.3 ± 0.2 | – |

| Partial thromboplastin time, s | – | 32 ± 5 | – |

| Echocardiography | |||

| Days from admission to echocardiography | 1 (0-4) | 2 (0-4) | 0.43 |

| Days from cardiac biomarker assessment to echocardiography | −1.5 (−4 to 0) | 1 (−4 to 8) | 0.006 |

| Coronary artery parameters | |||

| Left main coronary artery z score | 0.43 (−0.6 to +2.64) | 0.16 (−1.35 to +3.52) | 0.3 |

| Left anterior descending artery z score | 0.36 (−0.97 to +2.68) | 0.34 (−0.95 to +4.07) | 0.85 |

| Right coronary artery z score | 0.88 (−0.87 to +2.07) | 0.94 (−0.45 to +5.12) | 0.61 |

| Maximum coronary artery z score | 1.33 (−0.86 to +3.19) | 1.17 (−0.01 to +9.77) | 0.67 |

| Severity of coronary artery abnormality | 0.94 | ||

| Normal dimensions | 22 (68%) | 26 (74) | |

| Dilation only (z score 2 to < 2.5) | 5 (16%) | 4 (11) | |

| Small aneurysms (z score ≥ 2.5 to < 5) | 5 (16%) | 3 (9) | |

| Medium aneurysms (z score ≥ 5 to < 10 and < 8 mm) | 0 | 1 (3) | |

| Large/giant aneurysms (z score ≥ 10 or ≥ 8 mm) | 0 | 1 (3) | |

| Not well visualised | 0 | 1 (3) | |

| Ventricular parameters | |||

| LV end-diastolic dimension z score | 1 (−1.5-+2.6) | 0.8 (−2.6-+2.6) | 0.37 |

| Fractional shortening, % | 35 ± 4 | 36 ± 5 | 0.5 |

| LV ejection fraction, % | 66 ± 6 | 67 ± 8 | 0.67 |

| RV dysfunction | 0 | 1 (3) | 0.36 |

| LV dysfunction | 0 | 2 (6) | 0.19 |

| Electrocardiography | |||

| Nonsinus rhythm | 0 | 1 (3) | 0.35 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 131 ± 26 | 129 ± 33 | 0.72 |

| PR interval, ms | 121 ± 18 | 124 ± 21 | 0.71 |

| QRS duration, ms | 69 ± 9 | 71 ± 14 | 0.32 |

| QT interval, ms | 289 ± 39 | 292 ± 53 | 0.79 |

| Corrected QT interval, ms | 418 ± 23 | 418 ± 26 | 0.98 |

| Index of cardioelectrophysiologic balance (QT/QRS) | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Corrected index of cardioelectrophysiologic balance (QTc/QRS) | 6.2 ± 0.8 | 6 ± 1.1 | 0.57 |

| T-wave abnormality | 16 (50) | 12 (33) | 0.16 |

Values are presented as median (interquartile range), mean ± SD, or n (%).

ICU, intensive care unit; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LV, left ventricle; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; RV, right ventricle.

Comparison of KD and MIS-C patients

Given the relative similarities between the PreKD and PostKD groups, they were combined for comparison to the MIS-C patients. In total, 68 KD and 38 MIS-C patients were included. Details and comparison of these two groups are presented in Table 2 . The KD group was younger than the MIS-C group, with lower body mass index (BMI) by both absolute value and z score. KD patients had a median of 4 KD clinical criteria, whereas MIS-C patients had a median of 1.5 criteria, with 53% of MIS-C patients also meeting criteria for diagnosis of complete or incomplete KD. In both populations, conjunctivitis was the most common KD feature, followed by nonvesicular rash, oral mucosal changes and extremity changes. Lymphadenopathy was an infrequent finding for MIS-C patients.

Table 2.

Demographic, biochemical, and cardiologic characteristics of patients with Kawasaki disease (KD) compared with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C).

| KD (n = 68) | MIS-C (n = 38) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 3.2 (0.4-15.2) | 9.1 (0.8-17) | < 0.001 |

| Sex, male/female | 41/27 | 24/14 | 0.77 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 16.9 ± 5.1 | 20.1 ± 5.2 | 0.002 |

| Body mass index z score | −0.3 ± 1.6 | 0.7 ± 1.1 | 0.001 |

| Clinical course | |||

| Days of fever | 7 (3-14) | 6 (3-14) | 0.11 |

| No. of KD clinical features | 4 (1-5) | 1.5 (0-4) | < 0.001 |

| Conjunctivitis | 58 (85) | 20 (53) | < 0.001 |

| Cervical lymphadenopathy | 31 (46) | 1 (3) | < 0.001 |

| Rash | 52 (76) | 18 (47) | 0.002 |

| Extremity changes | 52 (76) | 9 (24) | < 0.001 |

| Oral mucosal changes | 58 (85) | 10 (26) | < 0.001 |

| Kawasaki disease diagnosis | < 0.001 | ||

| Complete | 39 (57) | 3 (8) | |

| Incomplete | 29 (43) | 15 (40) | |

| Does not meet criteria | 0 | 20 (53) | |

| Shock | 5 (7) | 15 (40) | < 0.001 |

| Intensive care unit (ICU) | |||

| Admission to ICU | 4 (6) | 18 (47) | < 0.001 |

| Length of ICU stay, days | 0 (0-3) | 2 (1-9) | < 0.001 |

| Inotropic support | 0 | 13 (34) | < 0.001 |

| Total hospital length of stay, days | 4 (3-10) | 6 (3-13) | 0.003 |

| Treatment | |||

| Days from admission to first immunomodulatory treatment | 1 (0-1) | 1 (0-3) | 0.15 |

| IVIG | 63 (90) | 32 (80) | 0.18 |

| Corticosteroids, intravenous | 13 (19) | 26 (68) | < 0.001 |

| Corticosteroids, oral | 23 (34) | 33 (87) | < 0.001 |

| Immunomodulatory agents | 2 (3) | 2 (5) | 0.56 |

| IVIG resistance | 12 (18) | 8 (21) | 0.56 |

| Biochemistry | |||

| Days from admission to cardiac biomarker assessment | 0 (−1, 4) | 1 (0, 5) | < 0.001 |

| Troponin I, ng/L | < 10 (< 10 to 88.5) | 61 (< 10 to 11,052) | < 0.001 |

| NT-proBNP, ng/L | 634 (41-10,752) | 4948 (107-27,313) | < 0.001 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 94.4 (6.7-342.3) | 109.1 (15.9-517.6) | 0.12 |

| Ferritin, μg/L | 195.6 (41.7-3046.4) | 512.3 (113.3-3137.5) | < 0.001 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, mm/h | 66 ± 31 | 59 ± 37 | 0.34 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 110 ± 12 | 103 ± 18 | 0.01 |

| Mean corpuscular volume, fL | 78.8 ± 5.4 | 79.4 ± 3.8 | 0.53 |

| White blood cells, ×109/L | 13.2 ± 5.9 | 13.1 ± 9.2 | 0.98 |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 310 ± 124 | 223 ± 113 | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 31 ± 20 | 50 ± 40 | 0.002 |

| Albumin, g/L | 35 ± 7 | 29 ± 6 | < 0.001 |

| Alanine transaminase, U/L | 30 (12-247) | 30 (13-134) | 0.13 |

| International normalised ratio | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.36 |

| Partial thromboplastin time, s | 32 ± 5 | 29 ± 5 | 0.07 |

| Echocardiography | |||

| Days from admission to echocardiography | 2 (0-4) | 1 (1-6) | 1 |

| Days from cardiac biomarkers assessment to echocardiography | −1 (−4 to 2) | 0 (−5 to 3) | < 0.001 |

| Coronary artery parameters | |||

| Left main coronary artery z score | 0.28 (−1.15 to +2.97) | 0.96 (−1.2 to +2.42) | 0.46 |

| Left anterior descending artery z score | 0.34 (−0.95 to +3.19) | 0.79 (−1.03 to +2.81) | 0.15 |

| Right coronary artery z score | 0.91 (−0,74 to +3.37) | 0.64 (−0.68 to +2.2) | 0.56 |

| Maximum coronary artery z score | 1.24 (−0.01 to +3.66) | 1.41 (0.05 to 2.81) | 0.85 |

| Severity of coronary artery abnormality | 0.13 | ||

| Normal dimensions | 48 (72) | 29 (76) | |

| Dilation only (z score 2- < 2.5) | 9 (13) | 6 (16) | |

| Small aneurysms (z score ≥ 2.5 to < 5) | 8 (12) | 3 (8) | |

| Medium aneurysms (z score ≥ 5 to < 10 and < 8 mm) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | |

| Large/giant aneurysms (z score ≥ 10 or ≥ 8 mm) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | |

| Not measured/visualised | 1 (1.5) | 0 | |

| Ventricular parameters | |||

| LV end-diastolic dimension z score | 0.9 (−1.7 to +2.5) | 0.5 (−2 to +1.9) | 0.18 |

| Fractional shortening, % | 36 ± 5 | 33 ± 7 | 0.04 |

| LV ejection fraction, % | 66 ± 7 | 61 ± 10 | 0.004 |

| RV dysfunction | 1 (2) | 5 (13) | < 0.001 |

| LV dysfunction | 2 (3) | 9 (24) | < 0.001 |

| Electrocardiography | |||

| Nonsinus rhythm | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0.68 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 130 ± 30 | 124 ± 25 | 0.33 |

| PR interval, ms | 123 ± 20 | 143 ± 28 | < 0.001 |

| QRS duration, ms | 70 ± 12 | 78 ± 12 | 0.005 |

| QT interval, ms | 290 ± 47 | 304 ± 48 | 0.15 |

| Corrected QT interval, ms | 418 ± 24 | 429 ± 35 | 0.07 |

| Index of cardioelectrophysiologic balance | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 4 ± 0.4 | 0.04 |

| Corrected index of cardioelectrophysiologic balance | 6.1 ± 1 | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 0.01 |

| T-wave abnormality | 28 (41) | 22 (58) | 0.07 |

Values are presented as median (interquartile range), mean ± SD, or n (%).

IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LV, left ventricle; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; RV, right ventricle.

Regarding severity of illness, MIS-C patients were more likely to have shock and admission to ICU with need for inotropic support. MIS-C patients had longer median ICU and total hospital lengths of stay. Regarding treatment, there was no difference in the use of IVIG or immunomodulators. MIS-C patients were more likely to have received both enteral and intravenous corticosteroids. There was no difference regarding the prevalence of IVIG resistance between the groups.

Cardiac involvement in MIS-C vs KD

Patients with MIS-C had higher median TnI, NT-proBNP, and ferritin levels, with lower hemoglobin, platelet counts, and albumin levels. There were no differences in the markers of general inflammation (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein). The MIS-C group had higher creatinine than the KD group (50 ± 40 vs 31 ± 20 μmol/L; P < 0.01), although this may be related to the differences in age and body size between the groups.

Regarding echocardiography, patients with MIS-C were more likely to have at least mild dysfunction of both right and left ventricles, both qualitatively and quantitatively, as noted by reductions in both left ventricular (LV) fractional shortening and ejection fraction. Notably, there were no statistically significant differences regarding coronary artery z scores between the KD and MIS-C groups. There was a trend toward a greater number and severity of coronary artery aneurysms for the KD cohort, although this did not reach statistical significance.

From electrocardiography, heart rates for the KD and MIS-C groups were similar despite age differences, suggesting perhaps a relative tachycardia for the MIS-C patients. Differences in PR interval, QRS duration, QT/QRS, and QTc/QRS were likely age related and appropriate. There was a trend toward more nonspecific T-wave abnormalities for the MIS-C group, which might be reflective of cardiac involvement in MIS-C, although this did not reach statistical significance.

Associations of cardiac biomarkers with diagnosis

From a multivariable linear regression model including patient characteristics, laboratory features, ECG findings, and diagnosis group (Table 3 ), higher log(NT-proBNP) was independently associated with a diagnosis of MIS-C vs KD after controlling for significant factors of male sex, lower albumin, higher heart rates, and longer PR intervals. Using logistic regression for diagnosis group, a receiver-operating characteristic curve was derived (Fig. 1A). From this, NT-proBNP > 2000 ng/L predicted a diagnosis of MIS-C vs KD with a sensitivity of 84% and specificity of 79%, and an overall area under the curve of 0.84.

Table 3.

Patient, clinical, laboratory, and electrocardiographic factors associated with log(NT-proBNP)∗

| Variable | Parameter estimate (SE) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.53 (0.66) | |

| Male sex | −0.27 (0.12) | 0.03 |

| Diagnosis of MIS-C (vs KD) | 0.54 (0.14) | < 0.001 |

| Lower albumin (per g/L) | −0.044 (0.009) | < 0.001 |

| Higher heart rate (per beat/min) | 0.009 (0.002) | < 0.001 |

| Longer PR Interval (per ms) | 0.006 (0.003) | 0.05 |

g, grams; KD, Kawasaki disease; L, litre; min, minute; MIS-C, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children; ms, millisecond; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide, SD, standard error

Multivariable linear regression model; model R2 = 0.49.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for differentiating multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) from Kawasaki disease for (A) N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and (B) troponin I. AUC, area under the ROC curve.

TnI was measured in all PostKD and MIS-C patients (n = 73). For this combined group, 41 patients (56%) had no detectable TnI. Of note, log(TnI) and log(NT-proBNP) were significantly correlated (r = 0.60; P < 0.001). A multivariable linear regression analysis for log(TnI) included patient characteristics, laboratory features, ECG findings, and diagnosis group (Table 4 ). Higher log(TnI) was independently associated with a diagnosis of MIS-C vs KD after controlling for significant factors of lower platelets, requirement of ICU care, longer QRS duration, and any T-wave abnormality. Using logistic regression for diagnosis group, a receiver-operating characteristic curve was derived (Figure 1B). From this, the presence of any detectable TnI (TnI > 10 ng/L) predicted a diagnosis of MIS-C vs KD with a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 78%, with an overall area under the curve of 0.83. Of note, when both NT-proBNP and TnI were included in a logistic regression model, the area under the curve improved only to 0.87.

Table 4.

Patient, clinical, laboratory, and electrocardiographic factors associated with log(TnI)∗

| Variable | Parameter estimate (SE) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −7.82 (1.64) | |

| Diagnosis of MIS-C (vs KD) | 2.32 (0.5) | < 0.001 |

| Intensive care unit admission | 1.16 (0.61) | 0.06 |

| Lower platelet count (per 109/L) | -0.0044 (0.002) | 0.03 |

| Longer QRS duration (per ms) | 0.075 (0.018) | < 0.001 |

| Any nonspecific T-wave abnormality | 1.37 (0.47) | 0.009 |

KD, Kawasaki disease; MIS-C, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children; TnI, troponin I.

Multivariable linear regression model; model R2 = 0.67.

Associations of cardiac biomarkers with LV function

NT-proBNP was not significantly associated with LV ejection fraction at the time of assessment, either with or without diagnosis in the regression model, and there was no significant interaction between NT-proBNP and diagnosis. However, higher TnI was significantly associated with lower LV ejection fraction, but only as log(TnI). Similar results were obtained both with and without diagnosis in the model, and there was no significant interaction with diagnosis.

Associations of cardiac biomarkers with coronary artery involvement

NT-proBNP was not significantly associated with maximum coronary artery z score in any branch at the time of assessment, either with or without diagnosis in the regression model, and there was no significant interaction between NT-proBNP and diagnosis. Similar results were obtained with log(NT-proBNP). Likewise, there was no significant association with TnI or log(TnI).

Discussion

SARS-CoV-2–associated MIS-C is a novel syndrome that has rapidly been characterised through the course of the pandemic. Cardiovascular involvement is one hallmark of the syndrome, with a variety of presentations including depressed ventricular function, cardiogenic shock, myocarditis, and coronary artery abnormalities in the form of dilation and aneurysms.13 , 15 Although the diagnostic criteria posed by the WHO have been helpful in raising suspicion for the disease, unless there is evidence confirming an association with COVID-19, they have limited ability to differentiate MIS-C from KD or provide prognostic value. In the present study, cardiac biomarkers were identified as a useful tool to help differentiate KD from MIS-C. With the presence of any positive TnI (TnI > 10 ng/L) or NT-proBNP > 2000 ng/L, MIS-C is the more likely diagnosis. Thus, determination of these cardiac biomarkers may be useful in the clinical setting for decision making, evaluation, and management.

Few studies have compared contemporaneous KD and MIS-C patients, or prepandemic and postpandemic KD patients. Our study further confirms important clinical similarities and differences between MIS-C and KD patients, with MIS-C patients having a higher median age with a greater risk of shock and ICU admission. Furthermore, we found few clinical differences between KD patients immediately before vs during the pandemic. Biochemically, compared with KD patients, MIS-C patients had greater elevations in TnI, NT-proBNP, and creatinine, along with thrombocytopenia, lower albumin, and partial thromboplastin time. Although the frequencies of coronary artery abnormalities were similar, MIS-C patients were less likely to have medium or large coronary artery aneurysms and were more likely to have greater degrees of dilation. Finally, LV ejection fraction and qualitative biventricular functional variables were all lower in MIS-C vs KD, with no significant differences in LV dimensions.

Features of histologic myocarditis have been reported for patients with acute KD.16 The majority of these patients, as in our study, are minimally symptomatic or have no evidence of functional impairment on echocardiography. In a recent study by Desjardins et al,17 patients with KD with elevations in NT-proBNP were more likely to have transient echocardiographic features of presumed mild myocarditis. Greater biochemical evidence of myocarditis noted with MIS-C is associated with observed greater clinical and functional cardiac abnormalities. Matsubara et al,18 in a small retrospective single-institution case series, noted similar findings in a comparison of MIS-C and KD patients, together with more subtle abnormalities of strain and diastolic dysfunction in the MIS-C patients. The fact that elevations in TnI and NT-proBNP may contribute to differentiation of MIS-C from KD, with TnI being the more sensitive marker in adjusted regression models and associated with high sensitivity and specificity, may help inform diagnosis and clinical decision making.

From a clinical perspective, there have been many studies characterising the clinical differences in patients with MIS-C and KD. In New York State, the initial MIS-C series highlighted a very severe inflammatory syndrome with a high prevalence of myocarditis.1 In their cohort, 71% of the patients with confirmed MIS-C had positive troponins and 80% were admitted to the ICU. Several months later, Kaushik et al19 published the experience from New York City alone, which clarified the broader spectrum of disease, which was echoed in more recent data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.20 In the United Kingdom, severe disease appeared to be less common, but the cohort was skewed to younger age groups which was associated with less severe illness overall.21

KD has always been strictly a clinical diagnosis, with heterogeneity in terms of identifying a clear cause or etiologic mechanism.8 , 15 Some patients with MIS-C clearly have a KD phenotype, and therefore there has been speculation from the very first descriptions of MIS-C as to whether the two conditions shared pathophysiology.11 Nonetheless, KD and MIS-C appear to be somewhat biochemically and clinically distinct.22 , 23 As such, these biomarkers may become useful in combination with other features to further clarify the pathophysiologic mechanism and to aide in both differentiation and prognostication.

Limitations

There were several potential limitations to this study. The first was the lack of samples for prepandemic measurement of TnI for the KD patients, lowering the overall power of the study and eliminating comparison between prepandemic and during-pandemic KD patients. Furthermore, there is a possible presence of selection bias in the PreKD population because there may have been certain factors that would have increased the likelihood of their participation, whereas the PostKD population was a more representative sample of the general population at the time based on any presentation to the emergency department. In addition, the PreKD patients had no evidence of macrophage activation syndrome or KD shock, which is likely representative of both the small patient numbers and the aforementioned possible selection bias for this group. Given that this may be a less sick population than a less-selected population, the impact on known acute phase reactants (anemia, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, and hyperferritinemia) may have been dampened. Similarly, it has been reported in the literature that NT-proBNP in the setting of inflammatory disease is an acute-phase reactant, thereby suggesting that it may be more of a general marker of inflammation rather than a specific marker of cardiac involvement in this scenario.24 , 25 Furthermore, although strict case definition criteria were applied, we cannot exclude that some of the earlier postKD patients actually had MIS-C, because early in the pandemic PCR and serologic testing were not widely available to exclude prior COVID-19 infection.

Another key limitation was the age difference in patients between the cohorts. Because age is collinear with many ECG parameters, it is unclear if the measured ECG duration differences have any clinical utility. Finally, there were often differences in the timing of echocardiography and collection of serum for biomarker testing. The window of 72 hours allowed for the capture of the majority of patients, but several patients were excluded, usually those with milder disease, though this was similar between the KD and MIS-C cohorts. Because this was a standard practice, it is unlikely to have substantially affected the results but may have resulted in missing more acute changes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study revealed that both elevated and greater elevations of TnI and NT-proBNP were associated with a diagnosis of MIS-C rather than KD with good sensitivity and specificity. Elevations in either biomarker were associated with male sex and were variably associated with other biochemical markers. Although, neither TnI nor NT-proBNP were useful in detecting risk of coronary artery abnormalities, it was clear that the KD population had a higher risk of developing coronary artery aneurysms compared with the MIS-C group, while the MIS-C patients were much more likely to present with shock, dysfunction, and require intensive care. Future directions for this work include determining if these biomarkers are capable of predicting clinical course, allowing for preemptive optimisation of management before the development of critical illness. Long-term data will also be needed to determine how myocardial and coronary artery involvement differs between the KD and MIS-C populations. Future studies regarding the different and shared pathophysiology of KD and MIS-C might consider the mechanisms for differences in these cardiac biomarkers.

Acknowledgements

We extend special thanks to the team of the International Kawasaki Disease Registry (IKDR) for their assistance in identifying local patients with Kawasaki Disease for analysis.

Funding Sources

Dr Tsoukas is supported by the Clinician-Scientist Training Program at The Hospital for Sick Children. Dr Yeung is supported by the Hak-Ming and Deborah Chiu Chair in Paediatric Translational Research, The Hospital for Sick Children.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

See page 822 for disclosure information.

References

- 1.Dufort E.M., Koumans E.H., Chow E.J., et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in New York State. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:347–358. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldstein L.R., Rose E.B., Horwitz S.M., et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organisation. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents temporally related to COVID-19. May 15, 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-and-adolescents-with-covid-19. Accessed October 2022.

- 4.Hoste L., van Paemel R., Haerynck F. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children related to COVID-19: a systematic review. Eur J Paediatr. 2021;180:2019–2034. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-03993-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bularga A., Lee K.K., Stewart S., et al. High-sensitivity troponin and the application of risk stratification thresholds in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2019;140:1557–1568. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nieminen M.S., Bohm M., Cowie M.R., et al. Executive summary of the guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of acute heart failure: the Task Force on Acute Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:384–416. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dionne A., Dahdah N. A decade of NT-proBNP in acute Kawasaki disease, from physiological response to clinical relevance. Children (Basel) 2018;5:141. doi: 10.3390/children5100141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCrindle B.W., Rowley A.H., Newburger J.W., et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e927–e999. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tajbakhsh A., Gheibi Hayat S.M., Taghizadeh H., et al. COVID-19 and cardiac injury: clinical manifestations, biomarkers, mechanisms, diagnosis, treatment, and follow up. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2021;19:345–357. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2020.1822737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCrindle B.W., Manlhiot C. SARS-CoV-2–related inflammatory multisystem syndrome in children: different or shared etiology and pathophysiology as Kawasaki disease? JAMA. 2020;324:246–248. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Consiglio C.R., Cotugno N., Sardh F., et al. The immunology of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with COVID-19. Cell. 2020;183:968–981.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh P., Katkar G.D., Shimizu C., et al. An Artificial Intelligence-guided signature reveals the shared host immune response in MIS-C and Kawasaki disease. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2687. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30357-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark B.C., Sanchez-de-Toledo J., Bautista-Rodriguez C., et al. Cardiac abnormalities seen in pediatric patients during the SARS-CoV2 pandemic: an international experience. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCrindle B.W., Li J.S., Minich L.L., et al. Coronary artery involvement in children with Kawasaki disease: risk factors from analysis of serial normalised measurements. Circulation. 2007;116:174–179. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.690875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kabeerdoss J., Pilania R.K., Karkhele R., et al. Severe COVID-19, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, and Kawasaki disease: immunological mechanisms, clinical manifestations and management. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:19–32. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04749-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujiwara H., Hamashima Y. Pathology of the heart in Kawasaki disease. Pediatrics. 1978;61:100–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desjardins L., Dionne A., Meloche-Dumas L., Fournier A., Dahdah N. Echocardiographic parameters during and beyond onset of Kawasaki disease correlate with onset serum N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) Pediatr Cardiol. 2020;41:947–954. doi: 10.1007/s00246-020-02340-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsubara D., Kauffman H.L., Wang Y., et al. Echocardiographic findings in pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID-19 in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:1947–1961. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaushik S., Aydin S.I., Derespina K.R., et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection (MIS-C): a multi-institutional study from New York City. J Pediatr. 2020;224:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godfred-Cato S., Bryant B., Leung J., et al. COVID-19–associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children—United States, March-July 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1074–1080. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swann O.V., Holden K.A., Turtle L., et al. Clinical characteristics of children and young people admitted to hospital with covid-19 in United Kingdom: prospective multicentre observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;370:m3249. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Q.Y., Xu B.W., Du J.B. Similarities and differences between multiple inflammatory syndrome in children associated with COVID-19 and Kawasaki disease: clinical presentations, diagnosis, and treatment. World J Pediatr. 2021;17:335–340. doi: 10.1007/s12519-021-00435-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee P.Y., Day-Lewis M., Henderson L.A., et al. Distinct clinical and immunological features of SARS-CoV-2–induced multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:5942–5950. doi: 10.1172/JCI141113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.di Somma S., Pittoni V., Raffa S., et al. IL-18 stimulates B-type natriuretic peptide synthesis by cardiomyocytes in vitro and its plasma levels correlate with B-type natriuretic peptide in nonoverloaded acute heart failure patients. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2017;6:450–461. doi: 10.1177/2048872613499282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yanagisawa D., Ayusawa M., Kato M., et al. Factors affecting N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide elevation in the acute phase of Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Int. 2016;58:1105–1111. doi: 10.1111/ped.12986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]