Summary

SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOCs) have shown resistance to vaccines targeting the original virus strain. An mRNA vaccine encoding the spike protein of Omicron BA1 (BA1-S-mRNA) was designed, and its neutralizing activity, with or without the original receptor-binding domain (RBD)-mRNA, was tested against SARS-CoV-2 VOCs. First-dose of BA1-S-mRNA followed by two-boosts of RBD-mRNA elicited potent neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) against pseudotyped and authentic original SARS-CoV-2; pseudotyped Omicron BA1, BA2, BA2.12.1 and BA5 subvariants, and Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta VOCs; authentic Omicron BA1 subvariant and Delta VOC. By contrast, other vaccination strategies, including RBD-mRNA first-dose plus BA1-S-mRNA two-boosts, RBD-mRNA or BA1-S-mRNA three-doses, or their combinations, failed to elicit high nAb titers against all of these viruses. Overall, this vaccination strategy was effective for inducing broadly and potent nAbs against multiple SARS-CoV-2 VOCs, particularly Omicron BA5, and may guide the rational design of next-generation mRNA vaccines with greater efficacy against future variants.

Subject areas: Molecular biology, Immunology, Virology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

BA1-S-mRNA prime and two-dose RBD-mRNA boosts is an effective vaccination strategy

-

•

It maintained potent neutralizing ability against the original strain of SARS-CoV-2

-

•

It enhanced neutralizing activity against multiple Omicron subvariants, including BA5

-

•

It induced strong neutralizing antibodies against other SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern

Molecular biology; Immunology; Virology

Introduction

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), which first emerged in 2019,1 has resulted in a worldwide pandemic with devastating economic losses and threats to public health. COVID-19 is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), one of the three highly pathogenic coronaviruses (CoVs) in the beta-CoV genus of the Coronaviridae family.1,2 As of November 11, 2022, SARS-CoV-2 has infected more than 630 million individuals worldwide and caused more than 6.58 million deaths.3

SARS-CoV-2 infection of host cells is initiated when receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the S1 subunit of the viral surface spike (S) protein binds to its receptor, angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), on host cells.4,5 The S2 subunit of the viral S protein subsequently mediates fusion between the virus and cell membranes.6 Native S protein presents as a trimeric structure, consisting of three receptor-binding domain (RBD) molecules.7 Therefore, the S protein and its RBD fragments are key targets for the development of anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and therapeutic antibodies.6,8,9

SARS-CoV-2 mutates rapidly and frequently, with multiple mutations being detected in its S protein and other proteins. These mutations have resulted in different variants of concern (VOCs), such as the Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (P.1), Delta (B.1.617.2), and Omicron (B.1.1.529) variants, with the Omicron variant subclassified as several subvariants, including BA1, BA2, BA3, BA4, and BA5.10 Currently, Omicron BA5 is the predominant subvariant, highly resistant to COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutic antibodies targeting the original SARS-CoV-2 S protein.11,12,13 Thus, the development of effective vaccines with high potency against BA5 and other VOCs with pandemic potential is important to prevent the global spread of SARS-CoV-2.

We previously designed a mRNA vaccine encoding the original RBD fragment of SARS-CoV-2 (RBD-mRNA).14 This vaccine induced the production of highly potent neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) against the original strain of SARS-CoV-2, protecting against a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 infection.14,15 However, its neutralizing activity against Delta (B.1.617.2) and Omicron (B.1.1.529) VOCs was significantly lower than its activity against the original strain.15 The present study describes the design of a new mRNA vaccine encoding the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA1 containing HexaPro sequences and a foldon trimeric structure (BA1-S-mRNA). Mice were immunized with this new mRNA vaccine, either sequentially or in combination with RBD-mRNA, and the vaccine-induced immunogenicity and neutralizing activity against several Omicron subvariants and various other VOCs were evaluated.

Results

Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines

BA1-S-mRNA was designed to encode a tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) signal peptide, the S protein of Omicron BA1, foldon, and His6 tag sequences; this mRNA also contained 5’- and 3’-untranslated regions (UTRs) (Figure 1A), with the control consisting of mRNA encoding the RBD of the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 (RBD-mRNA) and a His6 tag (Figure 1B). Each synthesized mRNA had a 5’-Cap 1 structure and a 3’-poly(A) tail, which was encapsulated with lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) for delivery (Figures 1A and 1B). Flow cytometry analysis showed that cells incubated with LNP-encapsulated BA1-S-mRNA or RBD-mRNA were strongly fluorescent, indicating the expression of specific proteins, whereas control cells were not (Figures 1C and 1D).

Figure 1.

Design of Omicron BA1-S mRNA vaccine and detection of its expression

(A) Schematic map of constructed SARS-CoV-2 BA1-S-mRNA.

(B) A mRNA encoding the RBD of the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 (RBD-mRNA) was included as comparison. Each synthesized mRNA was encapsulated with lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) to form mRNA-LNPs for delivery.

(C and D) Detection of protein expression of mRNA by flow cytometry analysis. LNP-encapsulated BA1-S mRNA (C) or RBD-mRNA (D) was incubated with 293T cells at 37°C for 48 h, and the cells were stained with mouse-anti-His-FITC antibody, followed by analysis of fluorescence signal (red) using flow cytometry. Gray shading indicates blank cells without incubation with mRNA-LNPs. The data are shown as median fluorescence intensity (MFI), and presented as mean ± standard deviation of the mean (SEM) of duplicate wells. The experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

Antibody responses induced by SARS-CoV-2 BA1-S-mRNA followed by RBD-mRNA sequential immunization

To determine the immunogenicity of BA1-S-mRNA, with or without sequential immunization with RBD-mRNA, mice were immunized with 1) three doses of RBD-mRNA alone, 2) three doses of BA1-S-mRNA alone, 3) one dose of BA1-S-mRNA followed by two doses of RBD-mRNA, 4) one dose of RBD-mRNA followed by two doses of BA1-S-mRNA, 5) three doses of a 1:1 combination of BA1-S-mRNA and RBD-mRNA, or 6) three doses of PBS (control) (Figure 2A). Doses were administered at 3-week intervals, and sera collected 10 days after the third immunization were pooled for each group and assessed for IgG and subtype antibodies specific to the S or RBD protein of the original strain of SARS-CoV-2, as well as to the Delta (B.1.617.2) and Omicron (B.1.1.529) variants (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Immunization schedules and vaccine-induced IgG antibody responses

(A) Immunization schedules. BALB/c mice were immunized with each mRNA or PBS control, and boosted twice with RBD-mRNA, BA1-S-mRNA, or their combination, at a 3-week interval. Sera were collected 10 days after the last immunization, and detected for specific IgG and subtype antibodies and neutralizing antibodies against the pseudotyped and authentic SARS-CoV-2 original strain and respective variants.

(B) IgG antibodies specific to the original SARS-CoV-2 wild-type (WT)-spike (S) protein.

(C) IgG antibodies specific to the original SARS-CoV-2 WT-RBD protein.

(D) IgG antibodies specific to the SARS-CoV-2 Delta-RBD protein.

(E) IgG antibodies specific to the SARS-CoV-2 BA1-S protein.

ELISA was performed using the mouse sera collected above. The ELISA plates were coated with each protein (1 μg/well), and IgG antibody titers are presented as mean ± SEM of four wells of pooled sera from five mice in each group (n = 5). Statistical significance was performed using Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ∗ and ∗∗∗ indicate p< 0.05 and p< 0.001, respectively, and demonstrate significant difference among different groups. The experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

Evaluation of vaccine-induced IgG antibodies demonstrated that three doses of RBD-mRNA alone induced higher titers of IgG antibodies specific to the wild-type S (WT-S), wild-type RBD (WT-RBD), and Delta-RBD proteins than to the S protein of Omicron-BA1 subvariant (BA1-S), whereas three doses of BA1-S-mRNA alone elicited higher IgG antibodies specific to the BA1-S protein than to the other proteins tested (Figures 2B–2E). A single dose of BA1-S-mRNA followed by two doses of RBD-mRNA elicited potent antibodies specific to the WT-S, WT-RBD, and Delta-RBD proteins (Figures 2B–2D), as well as favorable but relatively low-titer IgG antibodies specific to the BA1-S protein (Figure 2E). By contrast, one dose of RBD-mRNA followed by two doses of BA1-S-mRNA induced significantly low-titer IgG antibodies than single dose of BA1-S-mRNA plus two doses of RBD-mRNA against any of the proteins tested (Figures 2B–2E). Three doses of a 1:1 combination of BA1-S-mRNA and RBD-mRNA induced the production of higher-titer IgG antibodies targeting the WT-S protein than those against the other three proteins (Figures 2B–2E). The control, PBS, did not induce antibodies specific to any of these proteins (Figures 2B–2E).

Evaluation of vaccine-induced IgG subtype antibodies revealed that three doses of RBD-mRNA alone elicited more potent IgG1 antibodies than IgG2a and IgG2b antibodies specific to the WT-RBD protein, rather than to the BA1-S protein, whereas three doses of BA1-S-mRNA alone induced potently higher IgG1 antibodies than IgG2a and IgG2b antibodies specific to the BA1-S protein, rather than to the WT-RBD protein (Figures 3A–3F). By contrast, one dose of BA1-S-mRNA plus two doses of RBD-mRNA elicited higher-titer IgG1 antibodies than IgG2a and IgG2b antibodies with similar potency against both WT-RBD and BA1-S proteins (Figures 3A–3F). Notably, one dose of RBD-mRNA plus two doses of BA1-S-mRNA induced significantly lower IgG1, IgG2a, or IgG2b antibodies than one dose of BA1-S-mRNA plus two doses of RBD-mRNA specific to the WT-RBD or BA1-S protein (Figures 3A–3D). In addition, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibodies induced by combinatorial BA1-S-mRNA and RBD-mRNA were either similar or significantly lower than those induced by one dose of BA1-S-mRNA plus two doses of RBD-mRNA specific to the WT-RBD and BA1-S proteins (Figures 3B–3D and 3F). No specific IgG subtype antibodies were elicited in the PBS control mice (Figures 3A–3F).

Figure 3.

IgG subtype antibodies induced by different vaccination groups

Mouse sera collected 10 days after the last immunization (as shown in Figure 2) were assessed by ELISA for IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b subtype antibodies.

(A-C) IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b subtype antibodies specific to the SARS-CoV-2 wild-type (WT)-RBD protein.

(D-F) IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b subtype antibodies specific to the SARS-CoV-2 BA1-S protein. The ELISA plates were coated with each protein (1 μg/well). The IgG1 (A, D), IgG2a (B, E), and IgG2b (C, F) antibody titers are presented as mean ± SEM of four wells of pooled sera from five mice in each group (n = 5). Statistical significance was performed using Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate p< 0.05, p< 0.01, p< 0.001, respectively, and demonstrate significant difference among different groups. The experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

Taken together, the above data indicate that BA1-S-mRNA priming followed by two doses of RBD-mRNA, was capable of inducing effective antibodies against the original strain of SARS-CoV-2, as well as the Delta and Omicron variants, whereas RBD-mRNA priming followed by two doses of BA1-S-mRNA and BA1-S-mRNA alone were not.

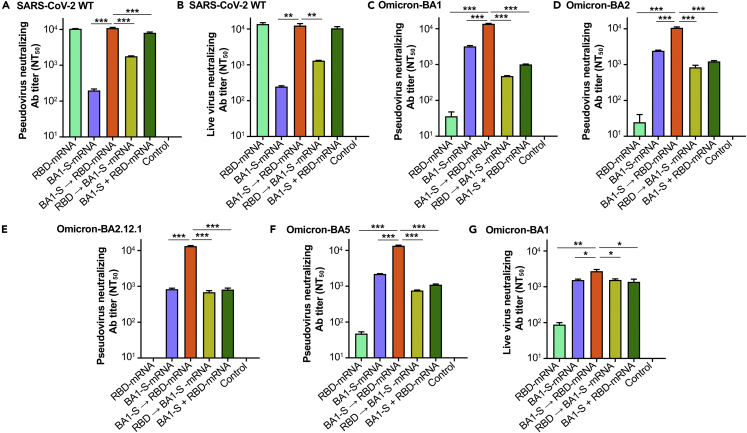

SARS-CoV-2 BA1-S-mRNA followed by RBD-mRNA sequential immunization enhanced neutralizing activity against multiple omicron subvariants

To evaluate the ability of BA1-S-mRNA, with or without sequential immunization with RBD-mRNA, to induce neutralizing antibodies against the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, sera collected 10 days after the third immunization (Figure 2A) were pooled for each group and tested against both pseudotyped and authentic Omicron (B.1.1.529) subvariants, including BA1, BA2, BA2.12.1, and BA5, with the control consisting of assays of neutralizing antibodies against the original strain of SARS-CoV-2.

Three doses of RBD-mRNA alone induced high-titer neutralizing antibodies against the pseudotyped and authentic original (WT) strains of SARS-CoV-2 (Figures 4A and 4B), but not against the Omicron subvariants (Figures 4C–4G). Nevertheless, three doses of BA1-S-mRNA alone induced relatively higher-titer neutralizing antibodies against the pseudotyped and authentic BA1 and other Omicron subvariants (Figures 4C–4G), but lower-titer neutralizing antibodies against the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 (Figures 4A and 4B). By contrast, immunization with one dose of BA1-S-mRNA followed by two doses of RBD-mRNA induced potent neutralizing antibodies against the pseudotyped (Figure 4A) and authentic (Figure 4B) original strain of SARS-CoV-2, and these titers were similar to those induced by administration of three doses of RBD-mRNA alone (Figures 4A and 4B). Notably, these neutralizing antibodies were significantly higher than those induced by other immunizations against all pseudotyped Omicron subvariants tested, including Omicron BA1, BA2, BA2.12.1, and BA5 (Figures 4C–4F), as well as authentic Omicron BA1 (Figure 4G). In particular, the titers of neutralizing antibodies against Omicron BA5 were not significantly reduced compared with the titers against the original strain and other Omicron subvariants (Figures 4A–4F). Differently, one dose of RBD-mRNA followed by two doses of BA1-S-mRNA induced similarly low-level neutralizing antibodies against all SARS-CoV-2 strains tested (Figures 4A–4F). The combination of RBD-mRNA and BA1-S-mRNA induced potent neutralizing antibodies against the original SARS-CoV-2 (Figures 4A and 4B), but relatively low-titer neutralizing antibodies against the Omicron subvariants tested (Figures 4C–4G). The negative control, PBS, did not elicit any SARS-CoV-2-specific neutralizing antibodies (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sequential immunization induced enhanced neutralizing antibodies against four SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants

Mouse sera collected 10 days after the last immunization (as shown in Figure 2) were detected for neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) against pseudotyped and authentic Omicron (B.1.1.529) subvariants. Pseudoviruses encoding the S proteins of Omicron BA2, BA2.12.1, and BA5 contained the respective RBD region and the rest of the BA1 S protein regions.

(A and B) NAbs against the original strain of pseudotyped (A) and authentic (B) SARS-CoV-2 wild-type (WT) controls.

(C) NAbs against pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA1 subvariant.

(D) NAbs against pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA2 subvariant.

(E) NAbs against pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA2.12.1 subvariant.

(F) NAbs against pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA5 subvariant.

(G) NAbs against authentic SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA1 subvariant.

50% neutralizing antibody titers (NT50) was calculated based on the antibody’s ability to neutralize infection of pseudotyped or live SARS-CoV-2. The pseudovirus neutralization assay was performed in 293T cells expressing hACE2 receptor (hACE2/293T), and the live virus neutralization assay was performed in Vero E6 cells. The titers of nAbs against pseudotyped and live SARS-CoV-2 are presented as mean ± SEM of four and duplicate wells, respectively, of pooled sera from five mice in each group (n = 5). Statistical significance was performed using Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate p< 0.05, p< 0.01, p< 0.001, respectively, and demonstrate significant difference among different groups. The experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

These data indicate that sequential immunization of BA1-S-mRNA followed by two doses of RBD-mRNA was able to elicit potent and broadly neutralizing antibodies against both SARS-CoV-2 original strain and multiple Omicron subvariants, including BA5. By contrast, the other vaccinations tested, including RBD-mRNA alone, BA1-S-mRNA alone or their combination, or one dose of RBD-mRNA followed by two doses of BA1-S-mRNA, were unable to induce the production of higher-titer antibodies that neutralized against the original SARS-CoV-2 strain and multiple Omicron subvariants tested.

SARS-CoV-2 BA1-S-mRNA followed by RBD-mRNA sequential immunization induced potent and broadly neutralizing antibodies against other variants of concern

The ability of BA1-S-mRNA, with or without sequential immunization with RBD-mRNA, to elicit neutralizing antibodies against other VOCs of SARS-CoV-2 was also tested using pooled sera obtained 10 days after the third immunization (Figure 2A).

Three doses of RBD-mRNA alone induced similarly high neutralizing antibodies against pseudotyped Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (P.1) and Delta (B.1.617.2) variants, and authentic Delta variant, whereas three doses of BA1-S-mRNA alone failed to elicit, or elicited very low-titer, neutralizing antibodies against these SARS-CoV-2 variants (Figures 5A–5E). Of note, administration of one dose of BA1-S-mRNA, followed by two boosts with RBD-mRNA, induced neutralizing antibodies against pseudotyped Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta variants and authentic Delta variant that were as potent as, or higher than, those elicited by three doses of RBD-mRNA (Figures 5A–5E). By contrast, one dose of RBD-mRNA followed by two doses of BA1-S-mRNA and three doses of 1:1 mixture of RBD-mRNA and BA1-S-mRNA, elicited lower, or significantly lower, neutralizing antibody titers against pseudotyped Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta variants (Figures 5A–5D) and authentic Delta variant (Figure 5E), than a single dose of BA1-S-mRNA followed by two doses of RBD-mRNA. Although neutralizing antibody titers in mice administered with one dose of RBD-mRNA followed by two doses of BA1-S-mRNA were higher than those in mice immunized with three doses of BA1-S-mRNA, they were lowest among the other vaccination groups (Figures 5A–5D). No SARS-CoV-2-specific neutralizing antibodies were induced in the control mice injected with PBS (Figures 5A–5E).

Figure 5.

Sequential immunization induced neutralizing antibodies against other variants of concern of SARS-CoV-2

Same mouse sera (as in Figure 4) were also detected for neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) against SARS-CoV-2 other variants of concern (VOCs).

(A) NAbs against pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Alpha (B.1.1.7) variant.

(B) NAbs against pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Beta (B.1.351) variant.

(C) NAbs against pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Gamma (P.1) variant.

(D) NAbs against pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Delta (B.1.617.2) variant.

(E) NAbs against authentic SARS-CoV-2 Delta (B.1.617.2) variant.

Pseudoviruses encoding the S protein of Alpha variant contained 10 amino acid mutations or deletions (69–70 deletion, 145 deletion, N501Y, A570D, D614G, P681H, T716I, S982A, and D1118H) as compared with the S protein of the original SARS-CoV-2.15 Pseudoviruses encoding the S proteins of Beta and Gamma variants contained K417N or K417T, E484K, and N501Y mutations in the RBD, and the S protein of Delta variant contained L452R, T478K, and P681R mutations in the S1 subunit, of the original SARS-CoV-2.15 50% neutralizing antibody titers (NT50) was calculated based on antibody’s ability to neutralize infection of each pseudotyped virus variant in hACE2/293T cells or authentic Delta variant in Vero E6 cells. The titers of nAbs against pseudotyped and live SARS-CoV-2 are presented as mean ± SEM of four and duplicate wells, respectively, of pooled sera from five mice in each group (n = 5). Statistical significance was performed using Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ∗ and ∗∗∗ indicate p< 0.05 and p< 0.001, respectively, and demonstrate significant difference among different groups. The experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

These findings indicate that sequential immunization with BA1-S-mRNA plus two doses of RBD-mRNA, rather than one dose of RBD-mRNA plus two doses of BA1-S-mRNA or three doses of BA1-S-mRNA, was able to induce highly and broadly neutralizing antibodies against other SARS-CoV-2 VOCs tested.

Discussion

Variants of SARS-CoV-2 are much more frequent than variants of other human pathogenic coronaviruses, such as SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV).2,15,16 Among currently identified Omicron subvariants, the predominant subvariant is Omicron BA5, being present in more than 29% of reported COVID-19 cases in the US.11 Most COVID-19 vaccines developed to date targeted the original S protein or RBD of SARS-CoV-2, with limited neutralizing activity against newly emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants, particularly the Omicron subvariants.17,18,19 Efforts have therefore focused on the development of advanced COVID-19 vaccines with greater neutralizing capacity against dominant Omicron variants/subvariants or multiple SARS-CoV-2 VOCs.

Different approaches have been applied to enhance the neutralizing activity of COVID-19 vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Several strategies involving an initial dose of a vaccine targeting the original strain of SARS-CoV-2, following by boosts with the same vaccine or vaccines targeting different antigens in the original strain or a variant. For example, a third dose of the CureVac COVID-19 (CVnCoV) mRNA vaccine was found to elicit increased neutralizing antibodies against the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 and the Delta (B.1.617.2) variant, and the neutralizing antibody titers were similar in naïve and pre-exposed participants.20 In addition, a third dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine increased the titers of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants (BA1. BA1.1, or BA2) and/or Delta variant.21,22 Moreover, a third dose of the inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac) also increased the neutralizing antibody titers against the Delta and Omicron variants.23 Differently, three doses of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine, or first and second doses of CoronaVac vaccine followed by third dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine, enhanced the titers of neutralizing antibodies against the Beta (B.1.351) and Delta (B.1.617.2) variants, but reduced titers against the Omicron variant.24

The present study describes a new approach, consisting of priming with the BA1-S-mRNA vaccine, which encodes the S protein of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA1 subvariant, followed by two doses of RBD-mRNA vaccine encoding the RBD of the original strain of SARS-CoV-2. Strikingly, this approach resulted in significant enhancement of neutralizing antibodies against all of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants tested, including BA1, BA2, BA2.12.1, and BA5, as well as maintaining the potency of RBD-mRNA to neutralize the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 and several other VOCs, including Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (P.1), and Delta (B.1.617.2). By contrast, a first dose of RBD-mRNA followed by two boosts of BA1-S-mRNA was unable to induce effective neutralizing antibodies against these SARS-CoV variants. Moreover, RBD-mRNA alone elicited high-titer neutralizing antibodies against the original strain of SARS-CoV-2, but not against Omicron subvariants, whereas BA1-S-mRNA alone elicited neutralizing antibodies against Omicron subvariants but not against the original strain of SARS-CoV-2. Multiple mutations have been identified in the RBD region of this S protein,15 with these mutations likely affecting the immunogenicity and neutralizing activity of the mutant RBD-containing S protein.

The present study compared various regimens of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines encoding the original RBD of SARS-CoV-2 and S protein of the Omicron BA1 subvariant, identifying an effective immunization strategy for the induction of broadly and potent neutralizing antibodies against multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants, particularly the currently predominant Omicron BA5 subvariant. This strategy may prevent infection by multiple current SARS-CoV-2 variants, as well as guiding the rational design and testing of next-generation mRNA vaccines with improved efficiency and efficacy against future variants of this virus.

Limitations of the study

In this study, pooled sera were used for evaluating antibody responses and neutralizing activity induced by the mRNA vaccines. Notably, comparison using pooled sera might diminish variations within the same group to some extent. In addition, the mRNA vaccine encoding the S protein was constructed based the Omicron BA1 variant of SARS-CoV-2, which is not a currently circulating strain. Thus, the sequential immunization strategy identified in this study will be applicable for future design of effective mRNA vaccines against other SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern or other CoVs with pandemic potential. We are also aware that except for RBD-mRNA encoding the original strain of SARS-CoV-2, a mRNA encoding the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 original strain would be an appropriate vaccine control and can be used as a comparison in the future studies.

This study did not observe the long-term immunogenicity and neutralizing activity of the designed mRNA vaccines. Our previous studies indicated that SARS-CoV-2 RBD-mRNA alone induced long-term and potent neutralizing antibodies against the original strain of SARS-CoV-2, protecting mice from SARS-CoV-2 infection.14,15 The sequential immunization with BA1-S-mRNA plus two doses of RBD-mRNA identified here induced broadly and high-titer neutralizing antibodies against all SARS-CoV-2 strains tested, including Omicron BA5 and other VOCs. These antibodies are expected to maintain long-term activity to neutralize divergent SARS-CoV-2 variants. Future studies are required to observe the longevity of the enhanced neutralizing activity and protection against SARS-CoV-2 VOCs.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-mouse IgG-Fab-HRP | Sigma | A9917; RRID: AB_258476 |

| Mouse-anti-His-FITC | Thermo Fisher Scientific | MA1-81891; RRID: AB_931255 |

| Anti-Mouse IgG1-HRP | Invitrogen | PA1-74421 |

| Anti-Mouse IgG2a-HRP | Invitrogen | M32207 |

| Anti-Mouse IgG2b-HRP | Invitrogen | M32407 |

| Virus strains | ||

| Pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 original strain | GenBank | Accession No: QHR63250.2 |

| Pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Alpha variant | GISAID | Accession No: EPI_ISL_718813 |

| Pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA1 subvariant | GISAID | Accession No: EPI_ISL_6795835 |

| Pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA2 subvariant | GISAID | Accession No: EPI_ISL_12030355 |

| Pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA2.12.1 subvariant | GISAID | Accession No: EPI_ISL_12061569 |

| Pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA5 subvariant | GISAID | Accession No: EPI_ISL_12043290 |

| Live SARS-CoV-2 original strain | GenBank | Accession No: MN985325 |

| Live SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant | GISAID | Accession No: EPI_ISL_2331496 |

| Chemicals | ||

| Agarose | Research Products International | A20090-500 |

| Crystal violet | Fisher Scientific | C581-100 |

| Fat-free milk | Bio-Rad | 1706404 |

| Polyetherimide (PEI) | Sigma | 919012 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Cap 1 Capping System Kit | CELLSCRIPT | C-SCCS1710 |

| GenVoy-ILM | Precision Nanosystems | NWW0042 |

| Luciferase Assay System | Promega | E1501 |

| MEGAscript T7 Transcription Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | AMB1334-5 |

| Poly(A) Polymerase Tailing Kit | CELLSCRIPT | C-PAP5104H |

| PNI Formulation Buffer | Precision Nanosystems | NWW0043 |

| ToxinSensor™ Chromogenic LAL Endotoxin Assay | GenScript | L00350 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| hACE2/293T | Laboratory stock | N/A |

| HEK293T | ATCC | CRL-3216; RRID: CVCL_0063 |

| Vero E6 | ATCC | CRL-1586; RRID: CVCL_0574 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pLenti-CMV-luciferase | Addgene | 17477 |

| PS-PAX2 | Addgene | 12260 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| FlowJo | BD Biosciences | N/A |

| Gen5 | BioTek Instruments | N/A |

| GraphPad Prism 9 | Graphpad Software | N/A |

| Other | ||

| Fetal bovine serum (FBS) | R&D Systems | S11550 |

| Cell lysis buffer | Promega | E153A |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 15140122 |

| Pseudo-UTP | APExBIO | B7972 |

| Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) | Sigma | T0440 |

| Tween-20 | Sigma | P1379 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the lead contact (ldu3@gsu.edu).

Materials availability

All unique constructs and related reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a Material Transfer Agreement.

Experimental model and subject details

Cell lines

HEK293T, hACE2/293T (e.g., 293T cells expressing human ACE2 receptor), and Vero E6 cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. The culture medium (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium: DMEM) contained 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (R&D Systems) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Viruses

The following SARS-CoV-2 pseudoviruses were used, which expressed the S protein or RBD of the original strain (GenBank: QHR63250.2), Alpha (B.1.1.7) variant (GISAID: EPI_ISL_718813), Omicron (B.1.1.529) subvariants BA1 (GISAID: EPI_ISL_6795835), BA2 (GISAID: EPI_ISL_12030355), BA2.12.1 (GISAID: EPI_ISL_12061569), and BA5 (GISAID: EPI_ISL_12043290). In addition, Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (P.1), and Delta (B.1.617.2) variants were constructed by mutating the RBD residues of the above original strain of SARS-CoV-2. Authentic SARS-CoV-2 original strain (USA-WA1/2020) (GenBank: MN985325), Delta (hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP05647/2021) (GISAID: EPI_ISL_2331496) and Omicron (B.1.1.529) (PP3P1hCoV19/EHC_C19_2811C) variants were used in this study.25

Mice

Female BALB/c mice at 6–8 weeks of age were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory, and randomly assigned to experimental groups. The animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) of Georgia State University. All mouse-related experiments were performed in strict accordance with the regulatory standards and guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), as well as our approved protocols.

Method details

Design and synthesis of SARS-CoV-2 mRNAs

The nucleoside-modified mRNAs encoding the RBD or S protein of SARS-CoV-2 were constructed as follows.14 Specifically, the DNA sequence of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron S containing a N-terminal tPA signal peptide, a C-terminal foldon trimeric sequence, and His6 tag (BA1-S-mRNA) was amplified by PCR using a plasmid encoding codon-optimized S protein with HexaPro sequences (a mutated furin cleavage site and six proline substitutions) of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (GISAID: EPI_ISL_6795835). The DNA sequence of SARS-CoV-2 RBD containing tPA signal peptide and a C-terminal His6 tag (RBD-mRNA) was constructed by PCR using a plasmid encoding codon-optimized S protein of SARS-CoV-2 original strain (GenBank: QHR63250.2). The purified PCR products were inserted into a pCAGGS-mCherry vector to construct recombinant plasmids, which also contained N-terminal T7 promotor, 5’ and 3’- UTRs (Figure 1).14

The nucleoside-modified mRNAs were synthesized as described below.14 Specifically, the above recombinant plasmids were linearized using BglII restriction enzyme, and synthesized using MEGAscript T7 Transcription Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Nucleosides CTP, ATP and GTP, as well as pseudo-UTP (Ψ) (APExBIO), were added during the mRNA synthesis to increase the stability of mRNAs and enhance the expression of target antigens. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, the purified mRNAs were then capped with Cap 1 Capping System Kit (containing ScriptCap Capping Enzyme and 2'-O-Methyltransferase) (CELLSCRIPT), and tailed with Poly(A) Polymerase Tailing Kit (CELLSCRIPT), which generated a Cap 1 structure and poly(A) tail (150 bp).

Encapsulating mRNAs with lipid nanoparticles (LNPs)

The synthesized mRNAs were encapsulated with LNPs (mRNA-LNPs) as described below.14 Specifically, each mRNA diluted in PNI Formulation Buffer (Precision Nanosystems) was encapsulated with lipid mixture (GenVoy-ILM) (Precision Nanosystems) (3:1 ratio) using NanoAssemblr Ignite Instrument according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Precision Nanosystems). This was followed by filtration and concentration of mRNA-LNPs using Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filters (10 kDa). The endotoxin level of mRNA-LNPs was detected by LAL Endotoxin Assay Kit (GenScript) (<1 EU/mL), with the particle size around 80–110 nm.

Detection of protein expression

Flow cytometry was used to detect the expression of LNP-encapsulated mRNAs in 293T cells.14 Specifically, the cells were pre-plated into 24-well culture plates (2×105/well) containing complete DMEM cell culture medium 24 h before experiments, incubated with each mRNA-LNP (1 μg/mL), and cultured at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. 48 h later, the cells were stained with mouse-anti-His-FITC antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and analyzed by flow cytometry (CytoFLEX flow cytometer, Beckman Coulter Life Sciences) using FlowJo software (BD Biosciences).

ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) was used to measure specific serum antibodies from immunized mice.15,26 Specifically, 96-well ELISA plates were precoated with each recombinant SARS-CoV-2 S or RBD protein (1 μg/mL)26 at 4°C overnight, and blocked with blocking buffer (e.g., 2% fat-free milk dissolved in PBST (0.05% Tween-20 in PBS)) at 37°C for 1 h. The plates were then incubated with serially diluted mouse sera at 37°C for 1 h, and washed with PBST for at least three times. This step was followed by further incubation of the plates with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG-Fab (1:5,000, Sigma), anti-mouse IgG1, anti-mouse IgG2a, and anti-mouse IgG2b (1:5,000, Invitrogen) antibodies, respectively, at 37°C for 1 h, and washing for three times. After incubation of the plates with 3,3’,5,5’-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (Sigma), the reaction was stopped by addition of 1 N H2SO4. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using Cytation 7 Microplate Multi-Mode Reader and Gen5 software (BioTek Instruments).

Pseudovirus generation and neutralization assay

SARS-CoV-2 pseudoviruses were generated as described below.15,26,27,28 Specifically, plasmid encoding S protein of the original strain or respective variant of SARS-CoV-2 was transfected into 293T cells in the presence of pLenti-CMV-luciferase plasmid and PS-PAX2 plasmid (Addgene) using the polyetherimide (PEI) (Sigma) transfection assay. 72 h after the transfection, pseudovirus-containing supernatants were collected, and used for pseudovirus neutralization assay. Each pseudovirus was incubated with serially diluted mouse sera at 37°C for 1 h, which was added to hACE2/293T cells; 24 h later, fresh medium was added to the cells, and the cells were cultured at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2, followed by lysis using cell lysis buffer (Promega) 48 later. The supernatant of lysed cells was incubated with luciferase substrate (Luciferase Assay System) (Promega), which was then measured for relative luciferase activity using Cytation 7 Microplate Multi-Mode Reader and Gen5 software (BioTek Instruments). Pseudovirus neutralizing activity was reported as 50% neutralizing antibody titer (NT50).

Live virus neutralization assay

Sera from immunized mice were tested for neutralizing activity against authentic SARS-CoV-2 infection using plaque reduction neutralization assay as described below.25,26 Specifically, serially diluted sera were incubated with the SARS-CoV-2 original strain, Delta (B.1.617.2) or Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant (40–80 plaque-forming unit (PFU)/well) at 37°C for 1 h. The virus-serum mixture was then added to Vero E6 (for original strain and Delta variant) or Vero E6 cells in the presence of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 (for Omicron variant) at 37°C for 45 min. The inoculum was removed, followed by overlaying the cells with 0.6% agarose (Research Products International) and culturing them for three days. The plaques were stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Fisher Scientific). The neutralizing antibody titer was calculated as NT50 (representing highest serum dilution that reduced the number of virus plaques by 50%).

Mouse immunization and related sample collection

Mice were immunized with respective mRNA-LNP as described below.14,15 Specifically, mice were intradermally (I.D.) immunized with the following groups of mRNA-LNPs (10 μg/mouse) or control: 1) RBD-mRNA (3 doses), 2) BA1-S-mRNA (3 doses), 3) BA1-S-mRNA (prime) and RBD-mRNA (2 boosts), 4) RBD-mRNA (prime) and BA1-S-mRNA (2 boosts), 5) combined RBD-mRNA and BA1-S-mRNA (3 doses), and 6) PBS control (Figure 2). The immunized mice were boosted twice at a 3-week interval, and sera were collected 10 days after the last immunization to detect specific IgG and subtype antibodies, as well as neutralizing antibodies, using ELISA and pseudovirus or live virus neutralization assays as described above.

Quantification and statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9 statistical software was used for analysis of the data generated in this study. The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance among different vaccination groups was calculated using Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. p<0.05 was considered significant. ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate p< 0.05, p< 0.01, and p< 0.001, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants (R01AI157975, R01AI139092, and R01AI137472).

Author contributions

G.W., J.S., A.K.V., and X.G. performed the in vitro experiments. G.W. and J.S conducted the animal experiments, summarized the data, and prepared the figures. S.P. revised the article. L.D. conceived the study, designed the experiments, supervised the project, and wrote and revised the article with input from all authors.

Declaration of interests

The authors have no financial interests to declare. The authors have filed a patent related to this work with L.D., G.W., and J.S. as inventors.

Published: December 22, 2022

Data and code availability

All data related to this study are presented in this paper. This paper does not report original code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

References

- 1.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang N., Shang J., Jiang S., Du L. Subunit vaccines against emerging pathogenic human coronaviruses. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:298. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . 2022. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard.https://covid19.who.int/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shang J., Ye G., Shi K., Wan Y., Luo C., Aihara H., et al. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;581:221–224. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang S., Hillyer C., Du L. Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses. Trends Immunol. 2020;41:355–359. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang S., Zhang X., Du L. Therapeutic antibodies and fusion inhibitors targeting the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2021;25:415–421. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2020.1820482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Goldsmith J.A., Hsieh C.L., Abiona O., et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Y., Du L. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: a key target for eliciting persistent neutralizing antibodies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021;6:95. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00523-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du L., Yang Y., Zhang X., Li F. Recent advances in nanotechnology-based COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutic antibodies. Nanoscale. 2022;14:1054–1074. doi: 10.1039/d1nr03831a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . 2022. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants.https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2022. COVID data tracker weekly review.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covidview/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Q., Guo Y., Iketani S., Nair M.S., Li Z., Mohri H., et al. Antibody evasion by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5. Nature. 2022;608:603–608. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05053-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuekprakhon A., Nutalai R., Dijokaite-Guraliuc A., Zhou D., Ginn H.M., Selvaraj M., et al. Antibody escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 from vaccine and BA.1 serum. Cell. 2022;185:2422–2433.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tai W., Zhang X., Drelich A., Shi J., Hsu J.C., Luchsinger L., et al. A novel receptor-binding domain (RBD)-based mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Cell Res. 2020;30:932–935. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0387-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi J., Zheng J., Zhang X., Tai W., Odle A.E., Perlman S., et al. RBD-mRNA vaccine induces broadly neutralizing antibodies against Omicron and multiple other variants and protects mice from SARS-CoV-2 challenge. Transl. Res. 2022;248:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2022.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tai W., Wang Y., Fett C.A., Zhao G., Li F., Perlman S., et al. Recombinant receptor-binding domains of multiple Middle East respiratory syndrome coronaviruses (MERS-CoVs) induce cross-neutralizing antibodies against divergent human and camel MERS-CoVs and antibody escape mutants. J. Virol. 2016;91 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01651-16. e01651–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edara V.V., Manning K.E., Ellis M., Lai L., Moore K.M., Foster S.L., et al. mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 mRNA vaccines have reduced neutralizing activity against the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant. Cell Rep. Med. 2022;3:100529. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100529. https://doi:.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sievers B.L., Chakraborty S., Xue Y., Gelbart T., Gonzalez J.C., Cassidy A.G., et al. Antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection or mRNA vaccines have reduced neutralizing activity against Beta and Omicron pseudoviruses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022;14:eabn7842. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abn7842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tada T., Zhou H., Dcosta B.M., Samanovic M.I., Chivukula V., Herati R.S., et al. Increased resistance of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant to neutralization by vaccine-elicited and therapeutic antibodies. EBioMedicine. 2022;78:103944. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolz O.O., Kays S.K., Junker H., Koch S.D., Mann P., Quintini G., et al. A third dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, CVnCoV, increased the neutralizing activity against the SARS-CoV-2 wild-type and Delta variant. Vaccines. 2022;10:508. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10040508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seki Y., Yoshihara Y., Nojima K., Momose H., Fukushi S., Moriyama S., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the Pfizer/BioNTech SARS-CoV-2 mRNA third booster vaccine dose against the BA.1 and BA.2 Omicron variants. Med (N Y) 2022;3:406–421.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2022.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang W., Huang L., Ye G., Geng Q., Ikeogu N., Harris M., et al. Vaccine booster efficiently inhibits entry of SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2022;19:445–446. doi: 10.1038/s41423-022-00837-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schultz B.M., Melo-González F., Duarte L.F., Gálvez N.M.S., Pacheco G.A., Soto J.A., et al. A booster dose of CoronaVac increases neutralizing antibodies and T cells that recognize Delta and Omicron variants of concern. mBio. 2022;13 doi: 10.1128/mbio.01423-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khong K.W., Liu D., Leung K.Y., Lu L., Lam H.Y., Chen L., et al. Antibody response of combination of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac platforms of COVID-19 vaccines against Omicron variant. Vaccines. 2022;10:160. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10020160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng J., Wong L.Y.R., Li K., Verma A.K., Ortiz M.E., Wohlford-Lenane C., et al. COVID-19 treatments and pathogenesis including anosmia in K18-hACE2 mice. Nature. 2021;589:603–607. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2943-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi J., Zheng J., Tai W., Verma A.K., Zhang X., Geng Q., et al. A glycosylated RBD protein induces enhanced neutralizing antibodies against Omicron and other variants with improved protection against SARS-CoV-2 infecnion. J. Virol. 2022;96 doi: 10.1128/jvi.00118-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tai W., Zhang X., He Y., Jiang S., Du L. Identification of SARS-CoV RBD-targeting monoclonal antibodies with cross-reactive or neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2. Antivir. Res. 2020;179:104820. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tai W., He L., Zhang X., Pu J., Voronin D., Jiang S., et al. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020;17:613–620. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0400-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data related to this study are presented in this paper. This paper does not report original code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.