Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic created an aberrant challenge for healthcare delivery systems, forcing public health policies across the globe to be shifted from traditional medical care in hospitals to virtual care in the homes of patients. To tackle this pandemic, telemedicine had taken center stage. This study aims to learn about patient satisfaction, feasibility, and acceptability of the use of telemedicine for clinical encounters during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methodology

This single-center, cross-sectional, observational study was done on a total of 758 patients who were provided with teleconsultations during the COVID-19 pandemic. We developed a 49-item questionnaire consisting of patients’ quality of consultation and patients’ expectations to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and patient satisfaction with their telemedicine consultations.

Results

The majority of survey participants (97.1%) expressed satisfaction with the quality of the consultations provided through telemedicine. A large percentage of participants (96.8%) reported the benefits of teleconsultation in treating their problems. Overall, 93.3% of participants responded positively to the continuation of teleconsultation services after the pandemic.

Conclusions

The study revealed a wide extent of satisfaction among patients. The feasibility and acceptability of telemedicine services have transformed the mode of healthcare delivery systems.

Keywords: covid-19, patient satisfaction, acceptability, feasibility, telemedicine

Introduction

On February 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared that the coronavirus outbreak that began in 2019 be known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [1], and the novel coronavirus was named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses [2]. The sudden emergence of this unknown virus with no specific treatment guidelines led to prioritizing preventive measures such as containment and isolation of COVID-19 patients at home to prevent the transmission of viruses. Globally, various public health policies implemented quarantine and isolation protocols to stop the transmission of the coronavirus into more communities. Due to this quarantine policy, there was a paradigm shift in medical care from hospitals to the homes of patients. The services of telemedicine were utilized as a first-line tool to elude the transmission of this pandemic [3-6]. Globally, telemedicine has been used in various forms over the last few decades [7-10]. However, the unwillingness to implement telemedicine by medical providers and patients themselves coupled with the absence of a valid legal framework and a lack of financial investment in technological resources for operating telemedicine services in hospitals led to the slow growth of telemedicine [11]. The COVID-19 pandemic provided the ideal platform for promoting and accelerating the implementation of digital technologies, such as telemedicine, to face this emergency.

Consultations for COVID-19 through telemedicine not only provided isolated individuals with timely information but also helped prevent loneliness, stress, and anxiety. This also helped patients to maintain a sense of social belonging that improved their physical symptoms [12]. Hospitalization involves a loss of independence; however, home care involves a familiar environment such as own room, bed, and other home amenities. However, research on the feasibility and acceptability of such services has been minimal in the past [13-16]. The primary objective of this study was to assess the feasibility and acceptability of telemedicine services during COVID-19. The secondary objective was to assess the profile and clinical characteristics of patients who participated in teleconsultation along with outcomes.

Materials and methods

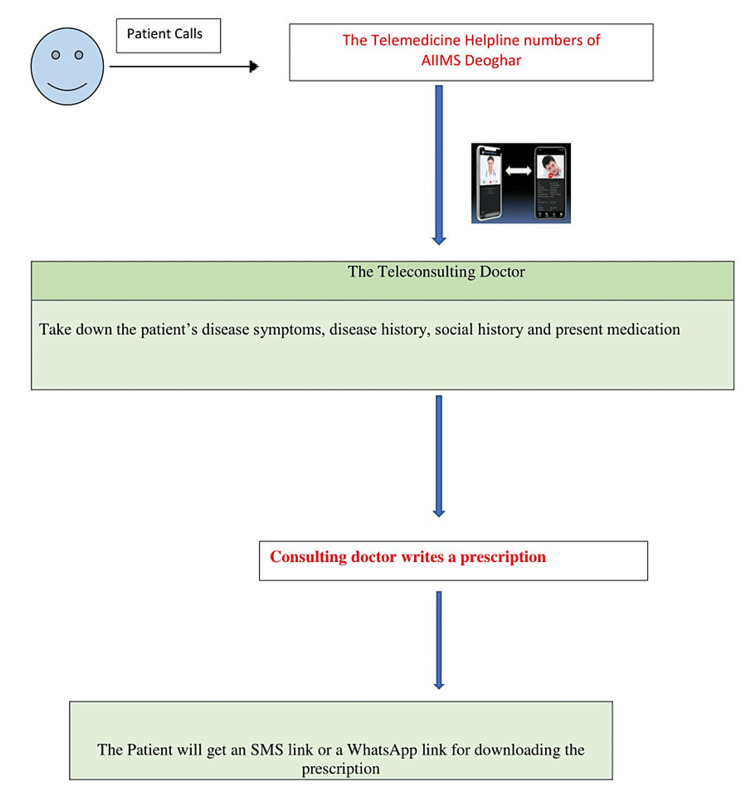

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional, observational study with a questionnaire-based design conducted between August 2021 and August 2022 at a government-run, tertiary care teaching hospital in the largest tribal area of India. To provide easily accessible and uninterrupted medical consultations and care to patients during the lockdown that resulted in the complete closure of outpatient department services throughout the country, the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Deoghar used COVID-19 teleconsultation services that had already been established by the telemedicine department of the institute. We provided teleconsultation through two telephone numbers dedicated to COVID-19 consultation every day via audio, video, or hybrid modes to patients who registered themselves between 9 am and 5 pm. Treatment protocols were set based on national guidelines and updated regularly. Clinicians from different specialties were posted in COVID-19 teleconsultation services and received regular training on COVID-19 treatment protocols. Regular training programs on updated treatment schedules were conducted. Case discussions occurred regularly to enhance case-based learning. We used two tablets with 4G sims and an internet facility to access popular messaging and video-calling platforms such as WhatsApp to provide teleconsultations. Treatment plans were written electronically, and prescriptions were sent to patients over WhatsApp. During teleconsultations, if clinicians felt there was an immediate need for the hospitalization of a patient, they were directed to the nodal officer of the COVID-19 control center for hospitalization and inpatient care. For proper follow-up, patients were encouraged to call back for teleconsultation continuity or resolve any new query. The different clinical complaints and details of the patients were noted by the clinician during teleconsultations. The confidentiality of patient data was maintained, and telecommunication was end-to-end encrypted according to the strict protocols of the Information Technology Act of India, 2000 and the Personal Protection Data Bill, 2019. We designed an appropriate tool in the form of a questionnaire to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and impact of telemedicine services of AIIMS Deoghar. The 49-item questionnaire was developed which included questions related to patients’ sociodemographic details, teleconsultation details, and expectations from telemedicine consultations, as well as the patients’ rating on the quality of the teleconsultation validated by two experts in the field. All patients who had availed of telemedicine services were prospectively requested to enroll in this study after obtaining consent. All data were collected on Google Forms. Feasibility criteria for this study were considered if the satisfaction with the quality of the consultation was greater than 50% among survey participants. Acceptability was defined as more than 50% of the participants responding positively to the continuation of the services. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of AIIMS Deoghar (approval number: 2021- 01-IND-01). Figure 1 shows a diagrammatic representation of the telemedicine services of AIIMS Deoghar.

Figure 1. Diagrammatic representation of the telemedicine services of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Deoghar.

Results

Sociodemographic details

A total of 758 patients agreed to be contacted after responding to a questionnaire related to the feasibility and acceptability of telemedicine consultations during COVID-19. A large proportion of survey participants (713, 94%) reported good to excellent access to coronavirus services, with local health centers located within a few kilometers. Vaccination services for survey participants were reported to be highly available to 740 (97.6%) participants compared to only 1.1% of participants who reported non-availability of vaccination services at their health centers. Almost two-thirds of survey participants (72.8%) reported they had no prior experience of consulting a doctor through telemedicine. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic variables of the study population.

Table 1. Sociodemographic variables of the study population.

| Variables | Groups | n (%) |

| Occupation | Skilled | 441 (58.2%) |

| Semiskilled | 129 (17% ) | |

| Unskilled | 188 (24.8% ) | |

| Educational status | Primary | 85 (11.2% ) |

| Secondary | 153 (20.25%) | |

| Undergraduate and above | 520 (68.6%) | |

| Income | Below poverty line | 348 (45.9%) |

| Above poverty line | 410 (54.1%) | |

| Area of living | Urban | 623 (82.2%) |

| Rural | 135 (17.8%) | |

| Sex | Male | 517 (68.2%) |

| Female | 241 (31.8%) |

Feasibility and acceptability of telemedicine services

Overall, 97% of participants were highly satisfied with the communication of the doctor during teleconsultation. Only two (0.3%) patients were not satisfied with the doctor’s communication. The majority of participants (97.7%) in the survey reported being given adequate time during consultation to state their queries, and only two (0.3%) participants were not satisfied with the consulting time given to them. Most participants (97.1%) reported that consulting doctors had completely understood and addressed all of their concerns regarding the disease, vaccination, medication, and investigation during teleconsultation, and only four (0.5%) participants had reported that consulting doctors had not clearly understood all of their concerns. During the survey, 85.5% of patients reported they had followed the advice given by doctors on the COVID-19 helpline. When participants were asked whether teleconsultations treated their problems, the majority of the participants (96.8%) responded positively, showing the feasibility of these teleservices. Only seven (0.9%) participants reported that teleconsultation did not benefit them at all. Regarding the continuity of these teleconsultation services, 93.3% of participants expected these telemedicine services to be continued after the pandemic, showing the acceptability of these teleconsultation services. Table 2 presents the nature of help-seeking and access to care, and Table 3 presents the feasibility and acceptability of telemedicine services.

Table 2. Nature of help-seeking and access to care.

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

| Variables | Groups | n (%) |

| Index person for whom help was sought | Myself | 613 (80.9%) |

| Family member | 145 (19.1%) | |

| Reason for seeking help | COVID-19 | 122 (16.1%) |

| Non-COVID19 | 525 (69.3%) | |

| Vaccine | 111 (14.6%) | |

| In case you have called for a COVID-19-positive patient, what was the reason for calling? | COVID-19 positive | 53 (7%) |

| Symptoms of COVID-19 positive | 90 (12%) | |

| Not a COVID-19-related call | 610 (81%) | |

| How far is the nearest healthcare facility to your place? | 0–10 km | 684 (90.2%) |

| 10–50 km | 58 (7.7%) | |

| >50 km | 16 (2.1%) | |

| Are you vaccinated for COVID-19? | First dose | 267 (35.2%) |

| Both dose | 273 (36 %) | |

| No | 218 (28.8%) | |

| What is the type of consultation for seeking help (to be explained to the caller)? | Primary consultation (index opinion) | 226 (29.8%) |

| Secondary consultation (second opinion) | 531 (70.1%) | |

| Referral from others | 00 (0%) | |

| How did you come to know about the telemedicine helpline? | Social media (Twitter, WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram) | 383 (50.5%) |

| Print media (newspaper) | 336 (44.3%) | |

| Audio-visual media (television, radio) | 6 (0.8%) | |

| Relatives, friends | 33 (4.4%) | |

| Patients | 00 (0%) |

Table 3. Feasibility and acceptability of telemedicine services.

| Variables | Groups | n (%) |

| Have you ever consulted a doctor over telemedicine in the past? | Yes | 206 (27.2%) |

| No | 552 (72.8%) | |

| If yes, compared to the earlier service how satisfied are you with this service? | Better than the previous one | 52 (6.9%) |

| Same as the previous one | 118 (15.7%) | |

| Worse than the previous one | 9 (1.2%) | |

| Not applicable | 571 (76.1%) | |

| Did you follow the advice given by the AIIMS helpline? | Yes | 651 (85.9%) |

| No | 78 (10.3%) | |

| Partially | 28 (3.7%) | |

| Are you worried about privacy and confidentiality? | Yes | 67 (8.8%) |

| No | 544 (71.8%) | |

| Not sure | 147 (19.4%) | |

| In which language do you expect your doctor should communicate with you? | Hindi | 727 (95.9%) |

| English | 13 (1.7%) | |

| Local language | 7 (0.9%) | |

| Mixed | 11 (1.5%) | |

| Do you want this consultant to be free or paid? | Free | 667 (88%) |

| Paid | 91 (12%) | |

| If the service is a paid consultation, how much would you like to pay? | 0–50 Rs | 90 (11.9%) |

| 51–100 Rs | 15 (2%) | |

| >101 Rs | 4 (0.5%) | |

| Not applicable | 648 (85.6%) | |

| What medium of consultation do you prefer? | Video consultation | 515 (67.9%) |

| Telephonic | 243 (32.1%) | |

| If we provide video consultation, will you be able to access the service? | Yes | 714 (94.2%) |

| No | 44 (5.8%) | |

| If yes, please provide the medium (here we are providing common mediums used) | 101 (13.4%) | |

| 642 (84.9%) | ||

| 4 (0.5%) | ||

| Google Meet | 00 (0%) | |

| Zoom | 00 (0 %) | |

| Not applicable | 8 (1.1%) | |

| No use of anything | 00 (0%) | |

| Which kind of consultation do you prefer? | Telemedicine | 200 (26.4%) |

| Face to face | 376 (49.6%) | |

| Combination | 182 (24%) | |

| Do you expect the prescription to be delivered to you during teleconsultation? | Yes | 747 (98.7%) |

| No | 10 (1.3%) | |

| If yes, what route do you prefer? | Social media like WhatsApp | 742 (98.1%) |

| Postal service | 12 (1.6%) | |

| No | 00 (0%) | |

| Do not want prescription | 00 (0%) | |

| Do you expect medicine to be given to you along with the prescription? | No, I will buy my own | 290 (38.3%) |

| Yes, at a subsidized rate | 379 (50.1%) | |

| Yes, free of cost | 85 (11.2%) | |

| According to the patient’s economic status | - | |

| It should be according to government policy | 00 (0%) | |

| Do not want prescription | 00 (0%) | |

| Do you think investigations should be ordered over telemedicine and reviewed on follow-up? | Yes | 749 (98.9%) |

| No | 8 (1.1%) | |

| Do you want telemedicine services to be continued after the pandemic? | Yes | 707 (93.3%) |

| No | 27 (3.6%) | |

| Not sure | 24 (3.2%) | |

| What kind of service do you expect in telemedicine? | Primary care | 101 (13.3%) |

| Specialist | 647 (85.5%) | |

| Referral service | 3 (0.4%) | |

| Not sure | 5 (0.7%) | |

| What should be the timing of the availability of telemedicine services? | Round the clock | 299 (39.5%) |

| Working | 415 (54.8%) | |

| Non-working | 35 (4.6%) | |

| Not sure | 8 (1.1%) |

Discussion

Telemedicine simply means patients consulting with a doctor for treatment through a virtual mode [17]. Before COVID-19, there was a slow growth of telemedicine due to limiting factors such as a lack of physical examination, non-availability of diagnostic testing or imaging, and various technical support issues [18,19]. Due to the high transmission and infection rates of the coronavirus, telemedicine took center stage in the management of patient healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic [20]. In the last week of March 2020, a complete lockdown was announced in India for a few weeks in an attempt to break the chain of infection and contain the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of non-emergency healthcare, such as outpatient clinics and hospitals, were converted to dedicated COVID-19 hospitals. Due to a large number of COVID-19-positive patients and a lack of available beds at COVID-19-dedicated hospitals, the Government of India encouraged home isolation of COVID-19-affected patients. The policy of home isolation was based on the finding that the majority of COVID-19 patients were either asymptomatic or had very mild symptoms. These cases usually do not require hospitalization in COVID-19-dedicated hospitals and can be managed at home under proper medical guidance and monitoring. This shifted the policy of COVID-19 management from COVID-19-dedicated hospitals to virtual management through different modes of teleconsultation.

A 24-hour service was provided for doctors and patients to communicate via a digital tool such as video calling. Even for patients who recovered from a COVID-19 infection, there was a need for medical care without exposure to other patients, which generally occurs during transportation or hospital consultations. Only a few prior studies have researched the perceptions of patients after telemedicine consultations. There was also a need to study the usefulness, acceptance, and satisfaction of telemedicine services by patients. In the past, few studies have assessed the quality of telehealth services and related patient satisfaction [21-24]. The concept of satisfaction is debatable. Some authors relate satisfaction to individual perceptions of the outcomes of care [25]. Abdel et al. conducted a cross-sectional survey study on 425 patients measuring their satisfaction with telemedicine used in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 pandemic and found that patients were satisfied with and positive toward telemedicine programs in Saudi Arabia [13]. Alromaihi et al. evaluated patient satisfaction and utilization of telemedicine services during COVID-19 on 901 participants and found a high level of satisfaction among patients. Overall, 56.6% of participants preferred to continue using telemedicine after the COVID-19 pandemic [14]. Baudier et al. conducted a questionnaire-based study to investigate the acceptance of teleconsultation services by patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study had over 386 respondents across several countries in Europe and Asia. The study highlighted the larger impact of performance expectancy, the negative influence of perceived risk, and the positive influence of contamination avoidance with the adoption of teleconsultation solutions [15]. Ramaswamy et al. conducted a retrospective, observational cohort study on 38,609 patients to determine if patient satisfaction differed between video consultations and traditional in-person clinic visits. The study found that patient satisfaction with video visits was high and not a barrier to a paradigm shift away from traditional in-person clinic visits [24]. Hong et al. investigated the population-level volume of internet searches for telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. They found that as the number of COVID-19 cases increased, so did the population’s interest in telehealth, with a strong correlation between population interest and COVID-19 cases reported (r = 0.948, p < 0.001) [22]. D’Souza et al. conducted a study in a tertiary health center in South India on telemedicine services during the COVID-19 pandemic and reported that a majority (95.39%) of patients were satisfied with the consultation rendered through telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic [16]. In our study, the majority of the participants (96.8%) expressed satisfaction with the teleconsultation provided to them during the COVID-19 pandemic and wished to continue them in the near future, illustrating the feasibility and sustainability of teleconsultation services.

A major limitation of telemedicine includes privacy and confidentiality issues along with technological glitches and medico-legal issues. One of the major limitations of our study was its single-center design with the absence of a control group (in-person consultation due to the closure of hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic) while assessing the patient’s satisfaction and willingness to use telemedicine services.

Conclusions

Understanding a patient’s attitude, perception, and satisfaction with virtual consultation is the most important factor in the success and development of telemedicine healthcare. The results of our study suggest a high satisfaction level among users of telemedicine, with the majority wanting to continue in the near future, showing the feasibility and acceptability of telemedicine services. However, a multicentric study comparing telemedicine with other moded of healthcare delivery systems is needed in the future.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Institutional Ethical Committee (IEC), AIIMS Deoghar issued approval 2021-01-IND-01

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

- 1.Ghebreyesus TA. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 25 May 2020. [ Jun; 2020 ]. 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---25-may-2020 https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---25-may-2020

- 2.The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. Hollander JE, Carr BG. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emerging telemedicine tools for remote COVID-19 diagnosis, monitoring, and management. Lukas H, Xu C, Yu Y, Gao W. ACS Nano. 2020;14:16180–16193. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c08494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Utility of telemedicine in the COVID-19 era. Colbert GB, Venegas-Vera AV, Lerma EV. https://doi.org/10.31083/j.rcm.2020.04.188. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2020;21:583–587. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm.2020.04.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The role of telemedicine in the delivery of health care in the COVID-19 pandemic. Valentino LA, Skinner MW, Pipe SW. Haemophilia. 2020;26:0–1. doi: 10.1111/hae.14044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The role of telehealth in the medical response to disasters. Lurie N, Carr BG. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:745–746. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Telemedicine and community health projects in Asia. Jha AK, Sawka E, Tiwari B, et al. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Historical perspectives: telemedicine in neonatology. Hoffman AM, Lapcharoensap W, Huynh T, Lund K. Neoreviews. 2019;20:0–23. doi: 10.1542/neo.20-3-e113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.[Telemedicine in dermatological practice: teledermatology] Danis J, Forczek E, Bari F. Orv Hetil. 2016;157:363–369. doi: 10.1556/650.2016.30371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Telemedicine: medical, legal and ethical perspectives. Clark PA, Capuzzi K, Harrison J. http://www.medscimonit.com/abstract/index/idArt/881286. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16:0–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Implementation and usefulness of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Hincapié MA, Gallego JC, Gempeler A, Piñeros JA, Nasner D, Escobar MF. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720980612. doi: 10.1177/2150132720980612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Measuring the patients' satisfaction about telemedicine used in Saudi Arabia during COVID-19 pandemic. Abdel Nasser A, Mohammed Alzahrani R, Aziz Fellah C, Muwafak Jreash D, Talea A Almuwallad N, Salem A Bakulka D, Abdel Ra'oof Abed R. Cureus. 2021;13:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evaluation of patients' satisfaction with the transition of internal medicine outpatient clinics to teleconsultation during COVID-19 pandemic [In press] Alromaihi D, Asheer S, Hasan M, et al. Telemed J E Health. 2022 doi: 10.1089/tmj.2021.0517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patients' perceptions of teleconsultation during COVID-19: a cross-national study. Baudier P, Kondrateva G, Ammi C, Chang V, Schiavone F. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2021;163:120510. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Healthcare delivery through telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: case study from a tertiary care center in South India. D'Souza B, Suresh Rao S, Hisham S, et al. Hosp Top. 2021;99:151–160. doi: 10.1080/00185868.2021.1875277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Telemedicine: a primer. Waller M, Stotler C. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2018;18:54. doi: 10.1007/s11882-018-0808-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Effectiveness of telemedicine: a systematic review of reviews. Ekeland AG, Bowes A, Flottorp S. Int J Med Inform. 2010;79:736–771. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cost-utility and cost-effectiveness studies of telemedicine, electronic, and mobile health systems in the literature: a systematic review. de la Torre-Díez I, López-Coronado M, Vaca C, Aguado JS, de Castro C. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:81–85. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapidly converting to “virtual practices”: outpatient care in the era of Covid-19: NEJM catalyst innovations in care delivery . Mehrotra A, Ray K, Brockmeyer DM, Barnett ML, Bender JA. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0091 NEJM Catalyst Innov Care Delivery. 2020;1:2. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patients' satisfaction with and preference for telehealth visits. Polinski JM, Barker T, Gagliano N, Sussman A, Brennan TA, Shrank WH. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:269–275. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3489-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Population-level interest and telehealth capacity of US hospitals in response to COVID-19: cross-sectional analysis of Google search and national hospital survey data. Hong YR, Lawrence J, Williams D Jr, Mainous II A. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:0. doi: 10.2196/18961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patient satisfaction toward a tele-retinal screening program in endocrinology clinics at a tertiary hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Alhumud A, Al Adel F, Alwazae M, Althaqib G, Almutairi A. Cureus. 2020;12:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patient satisfaction with telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: retrospective cohort study. Ramaswamy A, Yu M, Drangsholt S, Ng E, Culligan PJ, Schlegel PN, Hu JC. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:0. doi: 10.2196/20786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1996. Telemedicine: A Guide to Assessing Telecommunications in Health Care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]