Abstract

The cholesterol-dependent cytolysins (CDCs) are a major family of bacterial pore-forming proteins secreted as virulence factors by Gram-positive bacterial species. CDCs are produced as soluble, monomeric proteins that bind specifically to cholesterol-rich membranes, where they oligomerize into ring-shaped pores of more than 30 monomers. Understanding the details of the steps the toxin undergoes in converting from monomer to a membrane-spanning pore is a continuing challenge. In this review we summarize what we know about CDCs and highlight the remaining outstanding questions that require answers to obtain a complete picture of how these toxins kill cells.

Keywords: CD59, Cholesterol-binding protein, cholesterol-dependent cytolysin, intermedilysin, MACPF, membrane-protein interactions, perfringolysin O, pneumolysin, pore-forming toxin

INTRODUCTION

Pore-forming toxins (PFTs), bacterial toxins that act via membrane permeabilization, are typically produced to aid bacterial virulence or survival. Cholesterol-dependent cytolysins (CDCs) are a large family of PFTs observed in numerous Gram-positive bacterial genera including Streptococcus, Clostridium, Listeria and Gardnerella (1). However, the CDC family is continually expanding, with recent identification of CDCs in some Gram-negative bacterial species (2). Many CDC-producing bacteria are pathogenic in nature and cause human diseases such as necrotizing fasciitis, bacterial pneumonia or meningitis. Membrane permeabilization by CDCs is achieved via the formation of large (~250 Å in diameter) β-barrel pores, a process strictly dependent on the presence of cholesterol in the target membrane. Pore formation begins with the secretion of soluble CDCs monomers, which then bind membrane cholesterol, or the human cell-surface glycoprotein CD59 for a subset of CDCs (3–5), on the surface of the target cell. Membrane binding triggers oligomerization of monomers into a membrane-bound, uninserted circular prepore intermediate. Conversion to the membrane-inserted pore involves major conformational changes, most significantly the refolding of helical bundles into membrane-spanning β-hairpins that puncture the membrane and establish the β-barrel pore (6, 7).

The study of CDC structure and pore-forming mechanism over four decades has revealed the mechanism of CDCs, which has established the basis to understanding how a wider variety of pore-forming proteins function (1). Nonetheless, many outstanding questions remain. Here we highlight not only our current understanding of these fascinating bacterial toxins, but also where the gaps in our understanding contribute to outstanding questions.

STRUCTURAL FEATURES OF SECRETED CDCs

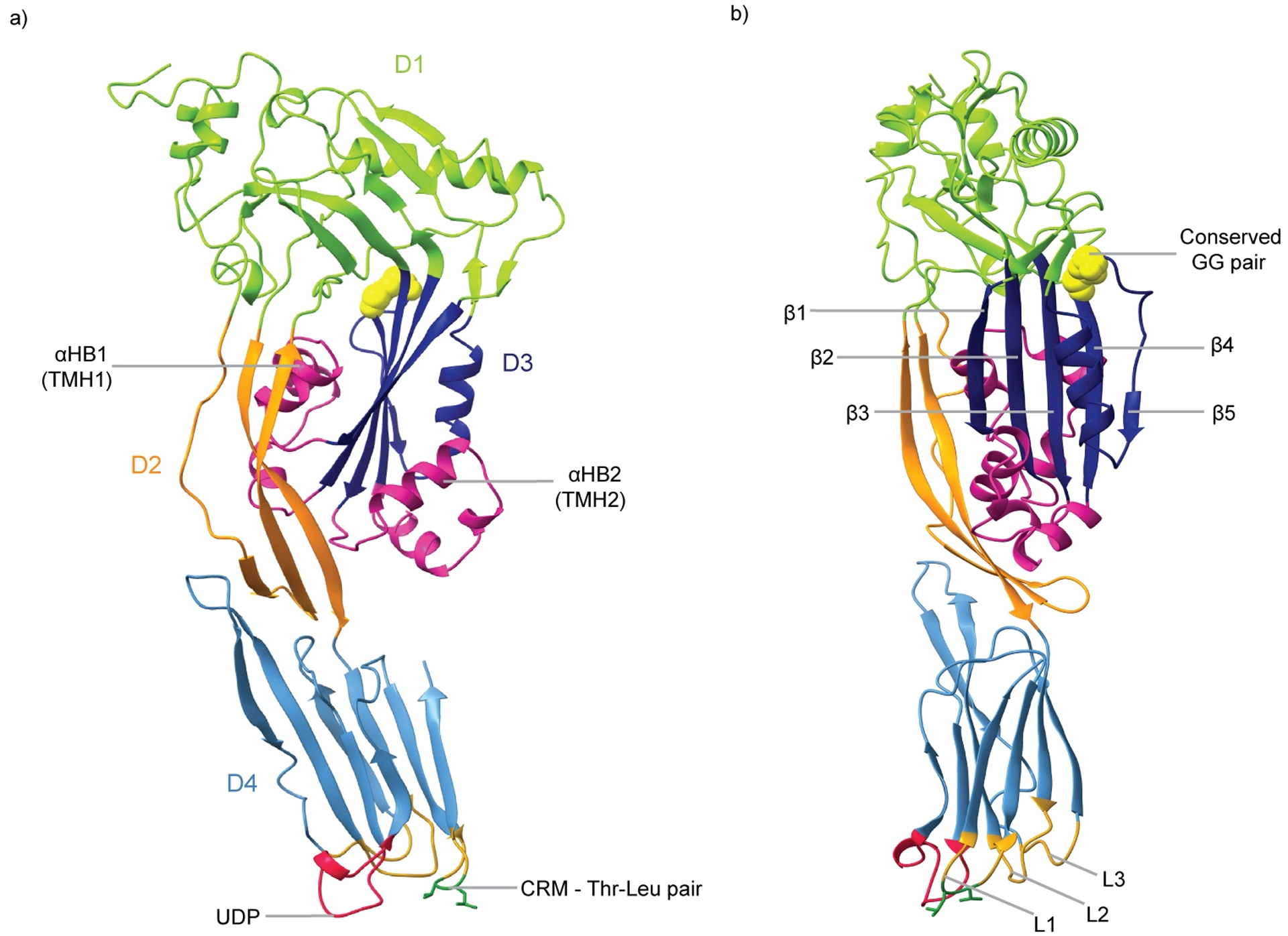

Our understanding of the structure of secreted, monomeric CDCs is comprehensive, owing primarily to the contribution of X-ray crystallographic studies. The first CDC crystal structure was perfringolysin O (PFO) (8), now considered to be the archetypical CDC as subsequent CDC structures revealed high structural similarity (9). PFO contains a four domain architecture (D1 – D4) with D1, D2 and D4 arranged in a linear manner to reveal an elongated molecule that is rich in β-sheet (Figure 1). The D2 domain, located between D1 and D4, acts a flexible linker between D1 and D4. The C-terminal D4 domain is a discrete domain, characterized by a twisted β-sandwich fold, whereas D1, D2 and D3 are non-contiguous in sequence.

Fig. 1. Crystal structure of the CDC monomer.

a) PFO monomeric structure (PDB ID: 1PFO) in which domains D1, D2, D3 and D4 are indicated in green, orange, navy and blue, respectively. The transmembrane hairpin (TMH) regions (αHB1 and αHB2) are colored in pink, the undecapeptide (UDP) in red, and the cholesterol recognition motif (CRM) in dark green. b) Side view of PFO (rotated by 90° about the y axis). The core beta-strands of D3 (β1 – β5) are indicated. The conserved glycine pair of D3 is shown in yellow CPK, and the loops L1 – L3 are in gold.

CDCs share between 40 – 70% sequence identity (10), with particular motifs observed to be more highly conserved. Two motifs are located within D4 binding domain at the base of the molecule. The undecapeptide motif, also referred to as the tryptophan-rich loop, is a 11-residue highly conserved signature motif of CDCs. Corresponding to residues 458 – 486 in PFO (E458CTGLAWEWWR468) (8), the undecapeptide shallowly inserts into the membrane during initial membrane binding steps, providing anchorage, but had also been hypothesized to trigger structural changes that initiate pore formation (11–13). The second motif, located in the L1 loop in D4, is a conserved Thr – Leu pair termed the cholesterol-recognition motif, based on its role in cholesterol binding (14).

D3 is the warhead of CDCs and is characterized by a five-stranded β-sheet flanked on either side by two α-helical bundles (α-helical bundles). During pore formation the two α-helical bundles undergo an α-helix-to-β-strand transition to form two transmembrane hairpins per CDC monomer that assemble into the β-barrel pore (6, 7). A further highly-conserved glycine pair, present between β-strand 4 (β4) and β5 of the core β-sheet, is involved in CDC oligomerisation.

While many CDCs closely resemble PFO, one intriguing outlier is the CDC lectinolysin (LLY). LLY possesses an additional “D0” domain. This domain, revealed to be a fucose-binding lectin domain, has been shown to bind the difucosylated Lewis Y/B glycans (15, 16). This begs questions about the purpose of this domain and how it binds sugars on the membrane surface prior to pore formation given its location at the top of the molecule?

The D1 – D3 fold has also been observed in a family of pore-forming proteins known as the mammalian membrane attack complex/perforin (MACPF) family, which includes proteins found in mammalian and non-mammalian eukaryotes, bacteria and apicomplexan parasites. This fold, frequently denoted as the MACPF/CDC domain, has been observed in the structures of numerous MACPFs (9), despite the diglycine motif being the only conserved sequence element between these family of proteins. Stonustoxin from stonefish venom, and related proteins, have also been observed to contain the MACPF/CDC domain (17). Phylogenetic studies suggest that the CDCs, the MACPFs and stonustoxin represent distinct branches of a wider superfamily (17). This suggests a common ancestor between these families exists; however, we are yet to uncover a representative of this ancestor, or how this fold has evolved to be observed across multiples families of proteins from such diverse species.

BINDING TO TARGET CELLS

The CDC receptor is considered to be cholesterol (18, 19) although some CDCs bind to a distinct protein receptor, but interaction with cholesterol is still required for activity. Early studies showed that cholesterol acted as the receptor on natural membranes (20, 21). For many decades, it was tacitly assumed that the conserved CDC signature motif, the undecapeptide, was the cholesterol-binding motif. While early studies showed this motif interacted with the membrane (22, 23) Soltani et al. (24) showed that three short nearby loops at the bottom of D4 were the primary mediators of membrane binding. Instead, the undecapeptide was required for subsequent pore formation with the coupling of membrane insertion of the undecapeptide to conformational changes in the pore-forming D3 domain subsequently shown (11, 12). One of the three short loops juxtaposed to the undecapeptide contain a conserved Thr – Leu pair, which was shown to be responsible for cholesterol recognition and binding of the CDC monomers to the membrane (14). Once cholesterol is recognized then the undecapeptide and two other nearby loops insert into the bilayer to firmly anchor the toxin to the membrane surface.

The CDC, intermedilysin (ILY), from Streptococcus intermedius was shown to be specific for human erythrocytes (25), which was inconsistent with cholesterol as the receptor. A decade later human CD59 was revealed as the receptor (4), which is a GPI linked membrane protein and an inhibitor of the complement membrane attack complex (MAC) (26). Human CD59 does not generally inhibit the MAC of other species and vice versa (27), which explained the restricted activity of ILY. However, ILY retains the cholesterol-recognition motif and exhibits an altered undecapeptide (GATGLAWEPWR versus ECTGLAWEWWR). The D4 loops and undecapeptide were still required for pore-forming activity, yet pore formation did not occur if CD59 was absent (28). This conundrum was resolved when it was shown that the loss of the cholesterol-binding motif resulted in the loss of pore formation. This was shown to result from the detachment of the pore complex from the membrane surface (14) as the ILY prepore had to disengage CD59 to convert to the pore (5). Hence, the formation of the cholesterol-dependent interaction was necessary to maintain the interaction of the prepore complex with the membrane.

The evolution of the CD59 binding capacity remains an enigma, as CD59 is present on nearly all cells so it doesn’t endow CDCs that bind CD59 (3) with any greater cellular specificity. Intriguingly, the contact residues used by CD59 to block the assembly of the MAC pore are also engaged by ILY, so that its engagement by ILY engenders increased sensitivity of the host’s cells to its MAC (5, 29). While ILY binds to cholesterol-POPC liposomes much better than PFO, it lacks any pore forming activity (12). This suggests that, unlike CDCs that are activated to oligomerize by cholesterol engagement, this activation switch has been transferred to the CD59 binding site in ILY.

Do other CDCs utilize different receptors in a manner similar to ILY? Recent reports have suggested that some of the CDCs may use various glycan receptors (30–33). However, these studies offer confusing results. For example, mannose (31) and the mannose receptor MRC-1 (32) have been suggested as receptors for Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumolysin (PLY). Although MRC-1 knockout cells were available the binding and toxicity of PLY on these cells was never tested (32). The authors also tested “deglycosylated” recombinant PLY for binding, yet recombinant PLY has never been shown to contain any glycosylation (34–36). In contrast, Shewell et al. (30, 33) found that PLY does not bind to mannose but instead binds sialyl-Lewis Y on MAC-1 although a massive amount (~2.5–10 million-fold molar excess of the glycan over PLY) was required to inhibit hemolytic activity and antibodies to the putative glycan receptors only reduced PLY binding to about 40% of normal levels. Earlier studies showed when the cholesterol-recognition motif was knocked out in PLY, no residual binding was detected up to concentrations of 500 nM by flow cytometry on human erythrocytes (14). Hence, whether glycans are truly CDC receptors remains unclear.

In broad terms we know how CDC – membrane targeting occurs; the main receptor is known and the few cases where an alternative exists are understood. What is lacking, however, is detailed molecular insight into how toxin engagement with the receptors translates to a functional localization of the protein to the cell membrane. No structure has been determined for a CDC – cholesterol complex and the existing CDC – CD59 complex structures do not explain how a membrane proximal protein-protein interaction translates to cholesterol-dependent CDC oligomerization. Does cholesterol binding by D4 generate a subtle structural change in the rest of the CDC that encourages oligomer formation, or is the effect simply a restriction of the protein to a surface that accelerates interaction with additional monomers through diffusion? How does the CDC – CD59 complex disengage to allow pore formation to occur? These questions arise from dynamic processes that occur during CDC – membrane interactions and can only be addressed by techniques that can provide information about the dynamics of the interaction at the molecular level.

While a range of experimental techniques, such as NMR, atomic force microscopy (AFM) and single-molecule fluorescence studies, can provide some insight into the dynamics of CDC-membrane interactions, they lack the resolution required to fully understand the details of these events. A powerful tool for investigating dynamics at atomic resolution is the use of computational molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. MD simulations of CDCs have previously been used to explore the stability of the CDC – CD59 complex (37), changes to lipid membrane structure in response to CDC binding (38), structural changes in CDCs during oligomer to prepore formation (39) and the role of structural waters in regulating CDC activation (40). The biggest limitation on MD simulations is the computational requirements for simulations of a size adequate to explore complex systems such as CDC pore – membrane complexes. Obtaining simulations of such systems over the timescale (milliseconds to seconds) of the events of interest is prohibitively expensive. To overcome this constraint, multiscale simulations can be employed where a simplified, low-resolution simulation is used to generate a long timescale view of the system, followed by atomic resolution MD simulations over shorter timescales to probe details of events of interest occurring in the lower resolution system. This approach has been used, coupled with AFM experimental observations, to model pore formation by gasdermin (41). Computational power continues to increase allowing timescales and system sizes that were once impossible to model to become accessible. In the long term, MD simulations are going to provide a powerful approach for studying the details of CDC – membrane binding.

OLIGOMERIZATION

When CDC monomers are secreted, their concentration rapidly decreases as they diffuse into the environment. Since the pore complex requires many monomers to form a functional pore, a stochastic model of assembly where dimers, trimers, tetramers, etc, form in a decreasing order of abundance would be unlikely to form functional oligomers as monomers become limiting. We showed that the only species detectable during the assembly of the PFO prepore and pore were monomer, dimer and the large oligomer (42). Similar results resulted when the assembly of the oligomer was conducted at 4°C, which allows the prepore to form but not the inserted pore. These data showed that the assembly was non-stochastic and that the formation of a stable dimer initiated structural changes that biased the addition of membrane-bound monomers to existing oligomeric structure, rather than initiating new oligomeric species.

It was later shown that the stable interaction of monomers displaced the β5 strand of the D3 core β-sheet (43), a process that is necessary for incoming monomers to form stable backbone hydrogen bond interactions between β-strands β4 and β1 in adjacent monomers (Figure 1). Visualization of this process was recently provided by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) of a SDS-sensitive early prepore of ILY (44). This revealed rearrangement of β5 away from β4 and into a new α-helix, with β4 observed to begin rotating towards the β1 strand of the adjacent molecule. The formation of a stable dimer is rate limiting since it requires two monomers to align properly and interact at a time where thermal fluctuations weaken the intramolecular backbone hydrogen bonds between β4 and β5, such that β5 can be displaced by strand β1 of another monomer dimer. When the stable dimer is formed β5 of the second monomer is displaced (43), which biases the addition of monomers to existing oligomers over the initiation of new oligomers.

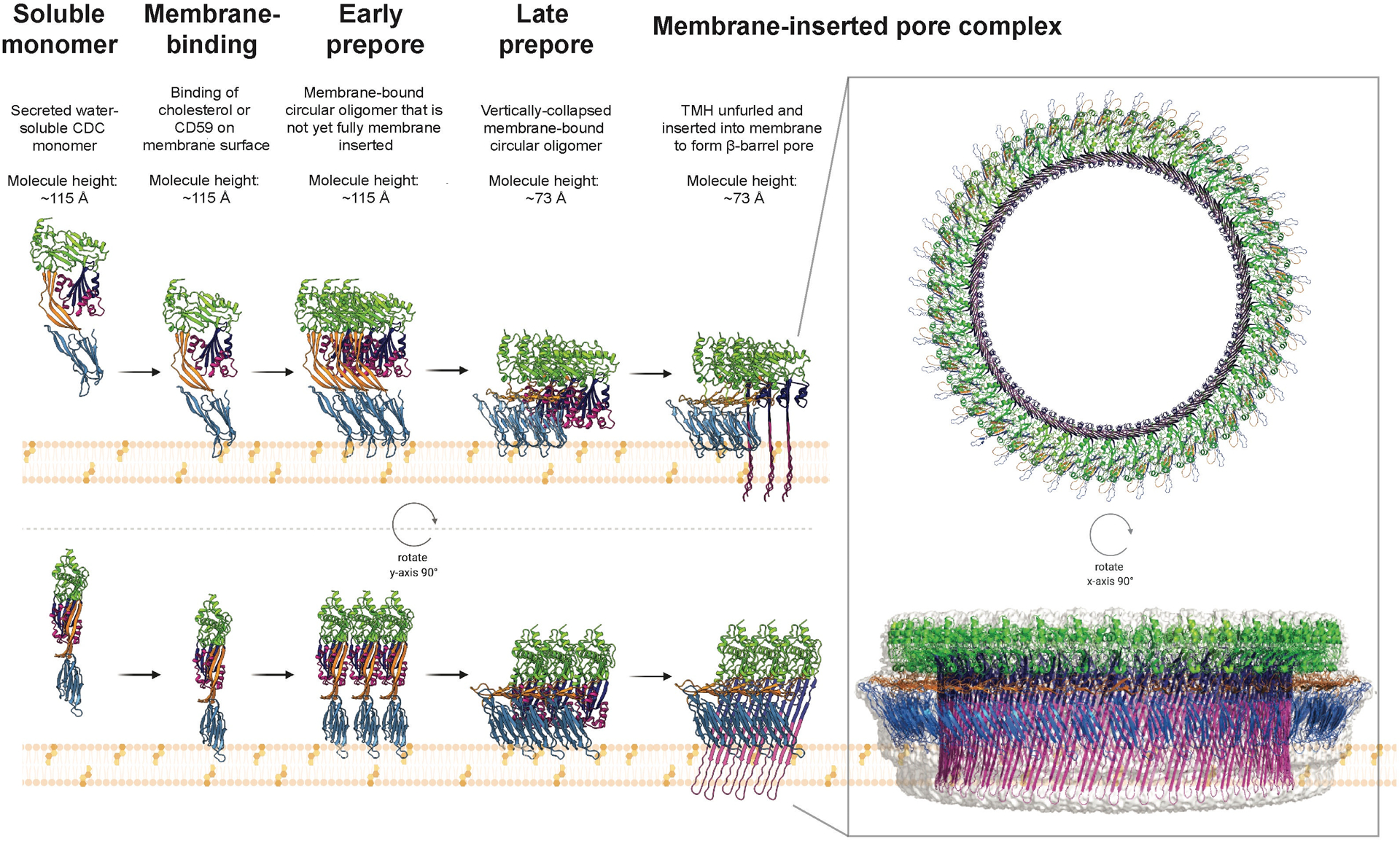

Receptor binding activates CDCs to oligomerize, whether it is cholesterol or CD59 (Figure 2), but how is this information is transmitted to D3 is unknown. It is known that mutations in D3 that affect the rate of formation of the pore also affect how fast D4 interacts with the membrane by measuring the insertion of the undecapeptide into the bilayer (11). Conversely, mutations in the undecapeptide can block the necessary transitions for pore formation in D3 without significantly affecting binding (12). How the undecapeptide of D4 is conformationally coupled to D3 remains an enigma. The D4 structure of PLY remains largely unchanged between the soluble monomer and the oligomeric complex (34, 36, 45) so a structural solution does not appear obvious. Other than the connecting β-strand between D2 and D4 the only other structure that exhibits a physical interaction with D4 is the D2 β-tongue. This β-tongue rotates about 90° upon the vertical collapse of the prepore and the formation of the pore complex. However, this does not provide any obvious explanation as how binding initiates pore formation. It is possible that binding itself simply increases the probability of two monomers interacting to form the stable dimer, which leads to the non-stochastic assembly of the prepore complex. However, this does not explain why ILY, which binds to cholesterol-rich liposomes that lack CD59, does not function unless also bound to CD59. Hence, further study is required to understand this process.

Fig. 2. The mechanism for pore formation by CDCs.

CDCs are produced and secreted as water-soluble, monomers. They bind cholesterol within cell membranes, or the receptor CD59 for some CDCs, triggering oligomerization into a membrane-tethered circular structure known as the prepore. Consisting of typically 35 – 45 monomers, this prepore stage can be divided into two separate events – the early prepore, characterized by a height of ~115 Å, and the subsequent late prepore at the lower height of ~73 Å, formed following a vertical collapse in height owing to rotation in D2. The final stage of the mechanism, membrane insertion, consists of the two α-helical bundles in each individual monomer undergoing a α-helix-to-β-strand transition and inserting into the membrane, forming the transmembrane β-hairpins of the β-barrel pore (> 250 Å in diameter). The figure was produced using the crystal structure of monomeric PLY (PDB ID: 5AOD) (69) and the fitted model of PLY for the cryo-EM structure of the PLY pore (PDB ID: 5LY6) (45).

PREPORE TO PORE

The first detectable stage of pore formation after binding is the formation of the oligomeric prepore - the state at which the oligomeric structure has formed but the α-helical bundles in D3 have not refolded into the membrane-spanning β-hairpins of the β-barrel pore (Figure 2). There appear to be different stages of the prepore complex, which can be trapped by temperature, specific mutations or engineered disulfides that prevent specific structural transitions necessary for the formation of the β-barrel pore. The first stages of the prepore complex were revealed wherein low temperature blocked the transition of PFO from a fully formed oligomeric state to the pore complex (42). An engineered disulfide that bridged α-helical bundle 1 to D2 also prevented this transition (46) and demonstrated that the β-barrel pore rapidly formed upon its reduction, which showed the prepore was primed for the insertion of the β-barrel pore.

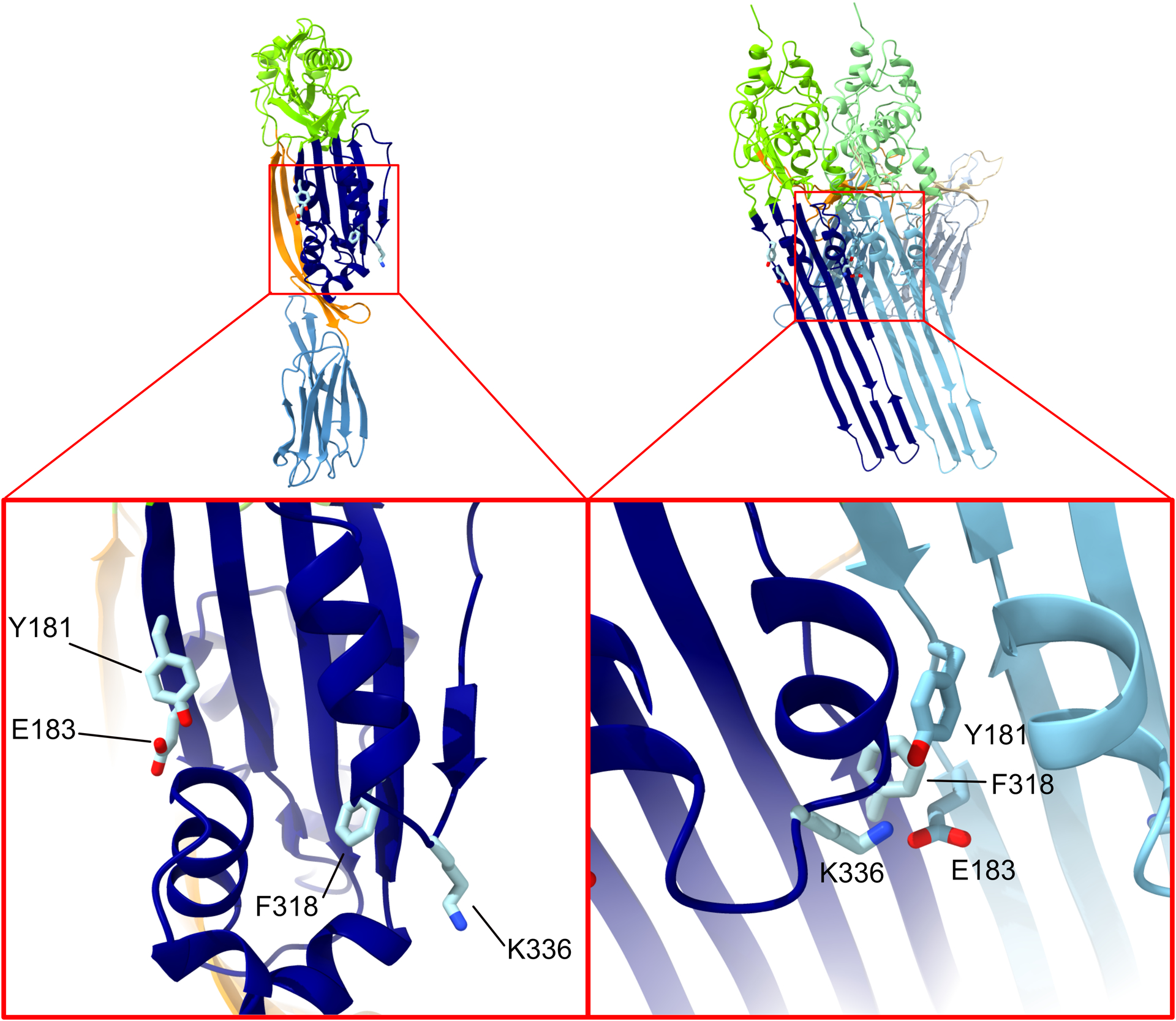

PFO can be trapped in the prepore state by specific mutations, particularly those that eliminate the intermolecular π-stacking (47) or electrostatic interactions (48) (Figure 3). These prepore states are identified by their susceptibility to dissociation by SDS and heat. In PFO the π-stacking interaction occurs between Y181 in the β1 strand and F318 in β4 of the adjacent monomer (47, 49) and the electrostatic interaction between E183 in β1 and K336 at the tip of the loop subsequent to β5 in D3 of the other monomer (48). These interactions were suggested to provide the energy to drive the flattening of the core β-sheet, which exhibits a significant twist in its structure in the monomer (48, 50) but not the oligomer (8, 34, 36, 45), by bringing strands β1 and β4 together between adjacent monomers of the prepore. The flattening of the core β-sheet resulted in the disruption of the interfaces between D2 and α-helical bundle 1, and between the outward facing surface of the core β-sheet and α-helical bundle 2, which allows the α-helical bundles to unfold into the transmembrane hairpins to form the β-barrel pore. Specific mutations at these interfaces (48, 50) could eliminate the need for these intermolecular interactions and restored WT or greater than WT pore-forming activity to PFO. One of those mutants (48) was found to disrupt a large water network that bridged domains D1 and D2 to α-helical bundle 1 (40). The presence of the water network at this interface explains why PFO activity decreases with temperature and is nearly inactive below 10°C. When this same mutation was introduced into WT PFO it exhibited pore formation kinetics at 9°C that were faster than native PFO at 37°C. Hence, this showed that CDCs’ temperature dependence can be easily adjusted by mutations that destabilize the interfaces and showed the CDCs can easily evolve to function when produced in bacteria that inhabit colder environments.

Fig. 3. Key interactions in prepore to pore conversion.

Assembly of the prepore results in several critical interactions that stabilize the monomer-monomer interface and help drive the conformational changes that lead to pore formation. On opposite sides of the PFO molecule residues Y181, E183, F318 and K336 are brought together on adjacent monomers by oligomerization, resulting in a pair of intermolecular interactions – a salt bridge and an aromatic ring stack. The left-hand image shows PFO (PDB ID: 1PFO) as a cartoon colored by domain, with the four residues of interest shown as sticks, with the lower image a close-up on the D3 region of PFO to highlight the residues’ position. The right-hand image is of a pair of PFO monomers from a model of the PFO pore, built on the basis of the cryo-EM structure of the PLY pore (45). The inset again shows a close-up view of the residues, but in this case in the interface between the two monomers. The network of interactions between the residues in this interface is clearly visible.

Once these interfaces are disrupted the CDC prepore is irrevocably committed to undergo the vertical collapse of 30 – 40 Å (Figure 2), which is necessary to bring the transmembrane hairpins sufficiently close to the membrane to span the bilayer (51–53). This collapse involves a rigid body rotation of D2 without further structural changes as seen by the cryo-EM structure of the PLY pore complex (45). Earlier studies suggested that in the temperature trapped prepore for PFO the α-helical bundles were in a molten globule state suggesting they were partially unfolded, ready to refold into the transmembrane hairpins (54).

Why do CDCs form a prepore structure? The existence of a prepore state was a subject of debate early in the discovery of the mechanism of β-barrel formation (7, 55) and had been suggested that the insertion of such a large prepore was energetically unfavourable (55). However, formation of a prepore that allows the formation of backbone hydrogen bonds of the β-barrel pore prior to its insertion overcomes a large energy penalty of partitioning peptide bonds into the bilayer (56). The advantage of a prepore state is also apparent from studies that show the β-barrel inserts much faster upon the reduction of a disulfide-trapped prepore complex (46).

CDC assembly depends on the complex interplay of the dynamics of CDC – membrane and CDC – CDC interactions and associated conformational changes, ultimately determining the kinetics and final architecture of pore formation. The intrinsically stochastic nature of key steps in the pathway leads to dephasing between different independently assembling CDC oligomers, which may also proceed along different pathways. As a result, identification of (short-lived) intermediates in the pathway and measurement of the transition kinetics between states requires experimental approaches that can follow the entire process (or parts thereof) at the single-particle and single-molecule level, ideally in real time.

AFM has emerged as a powerful method to image the assembly of individual pores and associated structural changes over time (53, 57, 58) whereby recent advances in high-speed AFM will allow higher temporal resolution (59). Single-molecule force spectroscopy can reveal the energetics of transitions (60). Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy can resolve the stoichiometry and diffusion of labelled CDC species assembling on the membrane (61, 62). The high sensitivity and temporal resolution enables detection of very short-lived events, such as monomer binding, and functional readouts can pinpoint specific steps such as opening of the transmembrane pore (61). These experimental methods are particularly powerful when combined with simulations of processes that are too fast to be resolved with existing imaging technologies, i.e., the restructuring of the lipid bilayer that leads to initial opening of the transmembrane pore (63). Similarly, kinetic models that are parameterized with experimentally measured rates are powerful tools to confirm the validity of proposed pathways and can be used to identify rate-limiting steps and predict assembly outcomes when specific steps are perturbed (61).

Ultimately these approaches can reveal the heterogeneity of assembly pathways and identify kinetic bottlenecks that can serve as control points for regulation. It is possible that final architectures (ring pore versus arc pores with semi-toroidal lipid edge or coalesced into larger pore structures) are simply kinetically controlled and dependent on their experimental conditions: e.g. CDC concentrations or membrane architecture (solid-supported flat versus curved bilayers) and lipid composition, that are likely to differentially affect the kinetics of steps in the pathway and thus lead to different outcomes. Comparison of the assembly kinetics of different CDC members with the same approaches will be required to tease out whether their assembly is governed by fundamentally different (regulatory) mechanisms and pathways that have evolved for specific functions or whether the transitions between states are essentially conserved but governed by different kinetics that determine the dominant pathway and final architecture.

PORE FORMATION

The assembly of the β-barrel in the bilayer remains unclear, as it must be understood that the side-chains of both the lumen and membrane facing residues must enter the non-polar core of the bilayer: some of these residues exhibit solvation free energies that makes it difficult to envision this process (56). Furthermore, backbone peptide bonds that do not satisfy their hydrogen bond potential also present a significant free energy barrier to insertion (56). Considering these energetic impediments to transmembrane hairpin insertion it appears unlikely that they spontaneously assemble into the bilayer: there must a contribution of energy to drive their insertion but this remains unknown.

Although β-barrel insertion requires the collapse of the prepore what triggers its collapse? Why doesn’t a dimer undergo this collapse? Furthermore, once the collapse occurs additional monomers cannot be added due to the difference in the structures of the membrane bound monomer versus that of the inserted monomer (8, 45). One could imagine that the completion of the ring triggers this event, but that does not explain what triggers an incomplete prepore arc to collapse. We understand the structural changes that occur during prepore collapse, but what initiates this event requires additional study.

The insertion of the β-hairpins appears to occur rapidly and appears to be an all to none process (49): in other words, their insertion occurs in a nearly simultaneous fashion, as suggested by the rapid insertion of the transmembrane hairpins in the disulfide-locked prepore PFO when reducing agent was added (46). There is also evidence that an intermediate state of the prepore may exist where the vertical collapse has occurred, but the β-barrel has not inserted (44). Thus, the formation of the β-barrel may not occur prior to prepore collapse.

The insertion of the CDC β-barrel pore requires the consideration of pore formation by the structurally related immune defence proteins perforin and complement C9 (9). There are two important differences in pore-forming mechanism of the CDCs with those of perforin and C9: perforin and C9 do not undergo a vertical collapse and their transmembrane hairpins are much longer than those found in the CDCs. Thus, when the α-helical bundles in perforin and C9 refold into transmembrane hairpins they are sufficiently long to span the membrane bilayer without moving closer to the bilayer. Considering the observations that CDCs undergo a vertical collapse to allow the hairpins to span the bilayer (51, 52) and that perforin and C9 have sufficiently long hairpins to span the bilayer without a vertical collapse suggests that a common mechanism of β-barrel membrane assembly in the bilayer has yet to be revealed.

MORE THAN JUST PORES

CDCs trigger several different responses on host cells in a CDC-, cell type- and concentration-dependent manner. At lytic concentrations CDCs induce cell death by necroptosis. At sub-lytic concentrations CDCs can initiate a variety of host cell responses that aid in bacterial proliferation and survival in an asymptomatic manner, as well as protect host cells. Host responses to CDCs include activation of cell signalling pathways, histone modifications, cytokine production, cytoskeleton remodelling and protein degradation, resulting in immune modulation, membrane repair, inflammasome activation, enhanced bacterial survival and effector translocation (as reviewed previously (64, 65)).

Aside from pore formation the early stages of pore assembly, including receptor binding and oligomerization, have been implicated in CDC mediated host responses. For example, recent work showed that LLO binding to cholesterol-rich membrane rafts activated inflammasomes via the Lyn-Syk signalling cascade (66), while binding and oligomerization of SLO, PFO and ILY enhance membrane repair by vesicle shedding (67). The molecular mechanisms governing CDC-induced host cell responses in a pore-independent manner are not well characterized. A key question that remains to be answered is oligomer structure at sub-lytic concentrations: i.e. are there fewer ring structures present or do arcs and incomplete rings dominate? What is the effect of arcs and incomplete rings on membrane integrity and arrangement? Typical concentrations used for structural studies, even cryo-EM, are much higher than the sublytic concentrations that drive host responses making it difficult to determine oligomer morphology at higher resolution. However, emerging methods in single molecule fluorescence, where much lower concentrations of CDCs are used, may provide an alternative method to assess the multiple effects of CDCs on cells.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The last few decades of research on CDCs have provided considerable insight into the complex mechanism of pore formation by these toxins, although this understanding remains incomplete as highlighted in this review. Nonetheless, an increased understanding of CDCs will lead to new approaches to reducing the virulence of their producing bacteria and enable their adaption for use in biotechnical applications. While further study of CDCs will hopefully uncover new details, it may also be the case that insights will be provided by the study of different, but related, pore-forming proteins. For example, a recently uncovered conserved CDC motif was revealed to exist in a large group of otherwise unrelated, uncharacterized proteins that have been named the CDC-like (CDCL) proteins (68). The next decade is sure to reveal further fascinating insights into the CDC/MACPF superfamily.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We apologize to the authors of papers not cited here due to space and reference count limitations. This work was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Project (DP160101874, DP200102871) to M.W.P and C.J.M. and by an NIH grant (R37-AI037657) to R.K.T. This work was also funded by an ARC Centre grant (IC200100052) to M.W.P. and R.J. Funding from the Victorian Government Operational Infrastructure Support Scheme to St Vincent’s Institute is acknowledged. M.W.P. is a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Leadership Fellow (APP1194263).

Abbreviations:

- CDC

cholesterol-dependent cytolysin

- ILY

intermedilysin

- PFO

perfringolysin O

- PFT

pore-forming toxin

- PLY

pneumolysin

- LLY

lectinolysin

- MACPF

Membrane Attack Complex/Perforin

- WT

wild-type

REFERENCES

- 1.Hotze EM. and Tweten RK (2012) Membrane assembly of the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin pore complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 1818, 1028–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hotze EM, Le HM, Sieber JR, Bruxvoort C, McInerney MJ, et al. (2013) Identification and characterization of the first cholesterol-dependent cytolysins from Gram-negative bacteria. Infect. Immun 81, 216–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gelber SE, Aguilar JL, Lewis KL, and Ratner AJ (2008) Functional and phylogenetic characterization of vaginolysin, the human-specific cytolysin from Gardnerella vaginalis. J. Bacteriol 190, 3896–3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giddings KS, Zhao J, Sims PJ, and Tweten RK (2004) Human CD59 is a receptor for the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin intermedilysin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 11, 1173–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wickham SE, Hotze EM, Farrand AJ, Polekhina G, Nero TL, et al. (2011) Mapping the intermedilysin-human CD59 receptor interface reveals a deep correspondence with the binding site on CD59 for complement binding proteins C8alpha and C9. J. Biol. Chem 286, 20952–20962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shatursky O, Heuck AP, Shepard LA, Rossjohn J, Parker MW, et al. (1999) The mechanism of membrane insertion for a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin: a novel paradigm for pore-forming toxins. Cell 99, 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shepard LA, Heuck AP, Hamman BD, Rossjohn J, Parker MW, et al. (1998) Identification of a membrane-spanning domain of the thiol-activated pore-forming toxin Clostridium perfringens perfringolysin O: an α-helical to β-sheet transition identified by fluorescence spectroscopy. Biochemistry 37, 14563–14574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossjohn J, Feil SC, McKinstry WJ, Tweten RK, and Parker MW (1997) Structure of a cholesterol-binding, thiol-activated cytolysin and a model of its membrane form. Cell 89, 685–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnstone BA, Christie MP, Morton CJ, and Parker MW (2021) X-ray crystallography shines a light on pore-forming toxins. Methods Enzymol. 649, 1–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tweten RK, Hotze EM, and Wade KR (2015) The unique molecular choreography of giant pore formation by the cholesterol-dependent cytolysins of Gram-positive bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol 69, 323–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heuck AP, Hotze EM, Tweten RK, and Johnson AE (2000) Mechanism of membrane insertion of a multimeric beta-barrel protein: perfringolysin O creates a pore using ordered and coupled conformational changes. Mol. Cell 6, 1233–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dowd KJ, Farrand AJ, and Tweten RK (2012) The cholesterol-dependent cytolysin signature motif: a critical element in the allosteric pathway that couples membrane binding to pore assembly. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polekhina G, Giddings KS, Tweten RK, and Parker MW (2005) Insights into the action of the superfamily of cholesterol-dependent cytolysins from studies of intermedilysin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 102, 600–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrand AJ, LaChapelle S, Hotze EM, Johnson AE, and Tweten RK (2010) Only two amino acids are essential for cytolytic toxin recognition of cholesterol at the membrane surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107, 4341–4346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrand S, Hotze E, Friese P, Hollingshead SK, Smith DF, et al. (2008) Characterization of a streptococcal cholesterol-dependent cytolysin with a lewis y and b specific lectin domain. Biochemistry 47, 7097–7107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feil SC, Lawrence S, Mulhern TD, Holien JK, Hotze EM, et al. (2012) Structure of the lectin regulatory domain of the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin lectinolysin reveals the basis for Its lewis antigen specificity. Structure 20, 248–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellisdon AM, Reboul CF, Panjikar S, Huynh K, Oellig CA, et al. (2015) Stonefish toxin defines an ancient branch of the perforin-like superfamily. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112, 15360–15365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shany S, Bernheimer AW, Grushoff PS, and Kim KS (1974) Evidence for membrane cholesterol as the common binding site for cereolysin, streptolysin O and saponin. Mol. Cell. Biochem 3, 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duncan JL. and Schlegel R (1975) Effect of streptolysin O on erythrocyte membranes, liposomes, and lipid dispersions. A protein-cholesterol interaction. J. Cell Biol 67, 160–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prigent D. and Alouf JE (1976) Interaction of streptolysin O with sterols. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 433, 422–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson MK, Geoffroy C, and Alouf JE (1980) Binding of cholesterol by sulfhydryl-activated cytolysins. Infect. Immun 27, 97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sekino-Suzuki N, Nakamura M, Mitsui KI, and Ohno-Iwashita Y (1996) Contribution of individual tryptophan residues to the structure and activity of theta-toxin (perfringolysin o), a cholesterol-binding cytolysin. Eur. J. Biochem 241, 941–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura M, Sekino-Suzuki N, Mitsui K, and Ohno-Iwashita Y (1998) Contribution of tryptophan residues to the structural changes in perfringolysin O during interaction with liposomal membranes. J. Biochem 123, 1145–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soltani CE, Hotze EM, Johnson AE, and Tweten RK (2007) Structural elements of the cholesterol-dependent cytolysins that are responsible for their cholesterol-sensitive membrane interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 20226–20231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagamune H, Ohnishi C, Katsuura A, Fushitani K, Whiley RA, et al. (1996) Intermedilysin, a novel cytotoxin specific for human cells secreted by Streptococcus intermedius UNS46 isolated from a human liver abscess. Infect. Immun 64, 3093–3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies A. and Lachmann PJ (1993) Membrane defence against complement lysis: the structure and biological properties of CD59. Immunol Res 12, 258–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rollins SA, Zhao J, Ninomiya H, and Sims PJ (1991) Inhibition of homologous complement by CD59 is mediated by a species-selective recognition conferred through binding to C8 within C5b-8 or C9 within C5b-9. J. Immunol 146, 2345–2351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soltani CE, Hotze EM, Johnson AE, and Tweten RK (2007) Specific protein-membrane contacts are required for prepore and pore assembly by a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin. J. Biol. Chem 282, 15709–15716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LaChapelle S, Tweten RK, and Hotze EM (2009) Intermedilysin-receptor interactions during assembly of the pore complex: assembly intermediates increase host cell susceptibility to complement-mediated lysis. J. Biol. Chem 284, 12719–12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shewell LK, Day CJ, Jen FE, Haselhorst T, Atack JM, et al. (2020) All major cholesterol-dependent cytolysins use glycans as cellular receptors. Sci. Adv 6, eaaz4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim JE, Park SA, Bong SM, Chi YM, and Lee KS (2013) Characterization of pneumolysin from Streptococcus pneumoniae, interacting with carbohydrate moiety and cholesterol as a component of cell membrane. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 430, 659–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Subramanian K, Neill DR, Malak HA, Spelmink L, Khandaker S, et al. (2019) Pneumolysin binds to the mannose receptor C type 1 (MRC-1) leading to anti-inflammatory responses and enhanced pneumococcal survival. Nat. Microbiol 4, 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shewell LK, Harvey RM, Higgins MA, Day CJ, Hartley-Tassell LE, et al. (2014) The cholesterol-dependent cytolysins pneumolysin and streptolysin O require binding to red blood cell glycans for hemolytic activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, E5312–5320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawrence SL, Feil SC, Morton CJ, Farrand AJ, Mulhern TD, et al. (2015) Crystal structure of Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumolysin provides key insights into early steps of pore formation. Sci. Rep 5, 14352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park SA, Park YS, Bong SM, and Lee KS (2016) Structure-based functional studies for the cellular recognition and cytolytic mechanism of pneumolysin from Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Struct. Biol 193, 132–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marshall JE, Faraj BHA, Gingras AR, Lonnen R, Sheikh MA, et al. (2015) The crystal structure of pneumolysin at 2.0Å resolution reveals the molecular packing of the pre-pore complex. Sci. Rep 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lawrence SL, Gorman MA, Feil SC, Mulhern TD, Kuiper MJ, et al. (2016) Structural basis for receptor recognition by the human CD59-responsive cholesterol dependent cytolysins. Structure 24, 1488–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ponmalar Ilanila I, Cheerla R, Ayappa KG, and Basu Jaydeep K (2019) Correlated protein conformational states and membrane dynamics during attack by pore-forming toxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 116, 12839–12844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reboul CF, Whisstock JC, and Dunstone MA (2014) A new model for pore formation by cholesterol-dependent cytolysins. PLoS Comput. Biol 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wade KR, Lawrence SL, Farrand AJ, Hotze EM, Kuiper MJ, et al. (2019) The structural basis for a transition state that regulates pore formation in a bacterial toxin. MBio 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mari SA, Pluhackova K, Pipercevic J, Leipner M, Hiller S, et al. (2022) Gasdermin-A3 pore formation propagates along variable pathways. Nat. Commun 13, 2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shepard LA, Shatursky O, Johnson AE, and Tweten RK (2000) The mechanism of assembly and insertion of the membrane complex of the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin perfringolysin O: Formation of a large prepore complex. Biochemistry 39, 10284–10293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hotze EM, Wilson-Kubalek E, Farrand AJ, Bentsen L, Parker MW, et al. (2012) Monomer-monomer interactions propagate structural transitions necessary for pore formation by the cholesterol-dependent cytolysins. J. Biol. Chem 287, 24534–24543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shah NR, Voisin TB, Parsons ES, Boyd CM, Hoogenboom BW, et al. (2020) Structural basis for tuning activity and membrane specificity of bacterial cytolysins. Nat. Commun 11, 5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Pee K, Neuhaus A, D’Imprima E, Mills DJ, Kuhlbrandt W, et al. (2017) CryoEM structures of membrane pore and prepore complex reveal cytolytic mechanism of Pneumolysin. eLife 6, e23644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hotze EM, Wilson-Kubalek EM, Rossjohn J, Parker MW, Johnson AE, et al. (2001) Arresting pore formation of a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin by disulfide trapping synchronizes the insertion of the transmembrane beta-sheet from a prepore intermediate. J. Biol. Chem 276, 8261–8268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramachandran R, Tweten RK, and Johnson AE (2004) Membrane-dependent conformational changes initiate cholesterol-dependent cytolysin oligomerization and intersubunit beta-strand alignment. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 11, 697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wade KR, Hotze EM, Kuiper MJ, Morton CJ, Parker MW, et al. (2015) An intermolecular electrostatic interaction controls the prepore-to-pore transition in a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112, 2204–2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hotze EM, Heuck AP, Czajkowsky DM, Shao Z, Johnson AE, et al. (2002) Monomer-monomer interactions drive the prepore to pore conversion of a beta-barrel-forming cholesterol-dependent cytolysin. J. Biol. Chem 277, 11597–11605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burns JR, Morton CJ, Parker MW, and Tweten RK (2019) An intermolecular pi-atacking interaction drives conformational changes necessary to beta-barrel formation in a pore-forming toxin. MBio 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramachandran R, Tweten RK, and Johnson AE (2005) The domains of a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin undergo a major FRET-detected rearrangement during pore formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 102, 7139–7144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Czajkowsky DM, Hotze EM, Shao Z, and Tweten RK (2004) Vertical collapse of a cytolysin prepore moves its transmembrane β-hairpins to the membrane. EMBO J. 23, 3206–3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leung C, Dudkina NV, Lukoyanova N, Hodel AW, Farabella I, et al. (2014) Stepwise visualization of membrane pore formation by suilysin, a bacterial cholesterol-dependent cytolysin. eLife 3, e04247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sato TK, Tweten RK, and Johnson AE (2013) Disulfide-bond scanning reveals assembly state and beta-strand tilt angle of the PFO beta-barrel. Nat. Chem. Biol 9, 383–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palmer M, Harris R, Freytag C, Kehoe M, Tranum-Jensen J, et al. (1998) Assembly mechanism of the oligomeric streptolysin O pore: the early membrane lesion is lined by a free edge of the lipid membrane and is extended gradually during oligomerization. EMBO J. 17, 1598–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wimley WC, Creamer TP, and White SH (1996) Solvation energies of amino acid side chains and backbone in a family of host-guest pentapeptides. Biochemistry 35, 5109–5124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mulvihill E, Van Pee K, Mari SA, Müller DJ, and Yildiz O (2015) Directly observing the lipid-dependent self-assembly and pore-forming mechanism of the cytolytic toxin listeriolysin O. Nano Lett. 15, 6965–6973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruan Y, Rezelj S, Bedina Zavec A, Anderluh G, and Scheuring S (2016) Listeriolysin O Membrane Damaging Activity Involves Arc Formation and Lineaction -- Implication for Listeria monocytogenes Escape from Phagocytic Vacuole. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiao F, Ruan Y, and Scheuring S (2021) High-speed atomic force microscopy to study pore-forming proteins. Methods Enzymol. 649, 189–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Czajkowsky DM, Sun J, and Shao Z (2015) Single molecule compression reveals intra-protein forces drive cytotoxin pore formation. eLife 4, e08421–e08421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mc Guinness C, Walsh JC, Bayly-Jones C, Dunstone MA, Christie M, et al. (2021) Single-molecule analysis of the entire perfringolysin O pore formation pathway. bioRxiv, 2021.2010.2019.464937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Senior MJ, Monico C, Weatherill EE, Gilbert RJ, Heuck AP, et al. (2021) Single-molecule imaging of cholesterol-dependent cytolysin assembly. bioRxiv, 2021.2005.2026.445776. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vögele M, Bhaskara Ramachandra M, Mulvihill E, van Pee K, Yildiz Ö, et al. (2019) Membrane perforation by the pore-forming toxin pneumolysin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 116, 13352–13357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Osborne SE. and Brumell JH (2017) Listeriolysin O: from bazooka to Swiss army knife. Philos. Trans. R. Soc, B 372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thapa R, Ray S, and Keyel PA (2020) Interaction of macrophages and cholesterol-dependent cytolysins: the impact on immune response and cellular survival. Toxins 12, 531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tanishita Y, Sekiya H, Inohara N, Tsuchiya K, Mitsuyama M, et al. (2022) Listeria toxin promotes phosphorylation of the inflammasome adaptor ASC through Lyn and Syk to exacerbate pathogen expansion. Cell Rep. 38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Romero M, Keyel M, Shi G, Bhattacharjee P, Roth R, et al. (2017) Intrinsic repair protects cells from pore-forming toxins by microvesicle shedding. Cell Death Differ. 24, 798–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Evans JC, Johnstone BA, Lawrence SL, Morton CJ, Christie MP, et al. (2020) A key motif in the cholesterol-dependent cytolysins reveals a large family of related proteins. MBio 11, e02351–02320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Pee K, Yildiz O (2015) Crystal structure of wild type pneumolysin 10.2210/pdb5AOD/pdb. [DOI]