Abstract

Adolescents and young adults (AYA) 13-24 years old make up a disproportionate 21% of new HIV diagnoses. Unfortunately, they are less likely to treat HIV effectively, with only 30% achieving viral suppression, limiting efforts to interrupt HIV transmission. Previous work with mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) has shown promise for improving treatment in AYA living with HIV (AYALH).

This randomized controlled trial compared MBSR with general health education (HT). Seventy-four 13-24-year-old AYALH conducted baseline data collection and were randomized to nine sessions of MBSR or HT. Data were collected at baseline, post-program (3 months), 6 and 12 months on mindfulness and HIV management [medication adherence (MA), HIV viral load (HIV VL), and CD4]. Longitudinal analyses were conducted. The MBSR arm reported higher mindfulness at baseline.

Participants were average 20.5 years old, 92% non-Hispanic Black, 51% male, 46% female, and 3% trans-gender. Post-program, MBSR participants had greater increases than HT in MA (p=0.001) and decreased HIV VL (p=0.052). MBSR participants showed decreased mindfulness at follow-up.

Given the significant challenges related to HIV treatment in AYALH, these findings suggest that MBSR may play a role in improving HIV MA and decreasing HIV VL. Additional research is merited to investigate MBSR further for this important population.

Keywords: adolescents, mindfulness, MBSR, youth, HIV, adherence

Introduction

Adolescents and young adults (AYA) 13-24 years old make up a significant and disproportionate 21% of new HIV diagnoses in the United States (U.S.). The high proportion of AYA is of particular concern, because this age group is least likely to link with medical care, get and maintain effective treatment, and have suppressed HIV viral load. Racial inequity is also evident. More than 50% of new HIV diagnoses in AYA are in African Americans, compared with less than 20% in Whites; although African Americans account for 16% of 15-19 and 20-24-year-olds in the U.S. population, they account for 60% and 50% of the HIV infections in these age groups, respectively (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020a; 2020b; U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). Further, the AYA living with HIV (AYALH) age group (13-24 years) has the lowest rate of HIV viral suppression at only 30%, compared with 53% in all ages. The overlap of this complex developmental stage and HIV infection is associated with experiences of internalized HIV stigma and misperceptions about living with HIV, as well as feelings of isolation and transition during adolescence and young adulthood (CDC, 2020a).

A central strategy of ending the HIV epidemic (EHE; Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2020) is improving medication adherence in those living with HIV to promote viral suppression and reduce transmissibility. Although antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been remarkably successful in improving clinical outcomes, up to 70% of youth are not virally suppressed, representing poor ART medication adherence and continued threat to curbing the epidemic (CDC, 2020a).

Preliminary data suggest that mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) could be beneficial to AYALH in addressing issues of psychological functioning and medication adherence. In a pilot trial with HIV-positive youth in Baltimore, participants in MBSR had higher life satisfaction, coping, and mindfulness and were more likely to maintain a reduced HIV viral load 3 months post-program compared to the control group (Webb et al., 2018). Additionally, previous research of MBSR with HIV-positive youth has shown positive impact on mental health, including lower levels of aggression, hostility, and emotional discomfort (Kerrigan et al., 2011, Sibinga et al., 2008; Sibinga et al., 2011).

The current study aimed to further explore MBSR for HIV medication adherence and mindfulness, by conducting a randomized controlled trial. Given previous research showing long-term benefits of mindfulness programs (e.g., Miller, 1995 and Bowen et. al., 2014), we followed participants for 12 months. It was hypothesized that compared with control, MBSR participation would improve HIV medication adherence, HIV viral load, and mindfulness in AYALH.

Methods

Participants

Participants were AYALH patients at medical clinics of two major academic centers in Baltimore, MD: 13-24 years old, HIV-positive, and aware of the diagnosis. Exclusions were: significant psychological, behavioral, or developmental problems determined by the clinical staff, making group participation harmful to participant or others; or living far from clinic/unavailable to attend. AYALH who were at least 18 years old provided informed consent for study participation; parent consent and participant assent was obtained for AYALH under the age of 18. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and University of Maryland Medical Center.

Study Arms

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) is a structured 8-week program designed to cultivate mindfulness, a focused non-judgmental awareness of present moment experience (Kabat-Zinn, 1990). The program was adapted for urban youth (Sibinga et al. 2008, 2011) from the broadly used evidence-based curriculum developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn (Kabat-Zinn, 1990). It consists of eight 2-hour weekly sessions and one 3-hour retreat. Consistent with MBSR, the program includes: 1) material related to mindfulness, meditation, yoga, and the mind-body connection, 2) experiential practice of mindfulness meditation, mindful yoga, and “body scan”, and encouragement of home practice, and 3) group discussion of barriers to effective practice. Group discussions focused on issues related to mindfulness practice; HIV was not a program topic. MBSR groups were led by two instructors trained at the University of Massachusetts’ Center for Mindfulness, experienced with working with urban youth.

Health education (Healthy Topics; HT) is an eight-week health education program adapted from the Glencoe Health Curriculum (McGraw-Hill, 2005) and served as an active control. Previous RCTs using this curriculum show that HT is an effective control condition for MBSR (Sibinga et al., 2013; Webb et al., 2018). The HT program is matched for session frequency and length, group size, location, and timing. The program also controls for the presence of a positive adult instructor, peer group experience, learning new material, attention, and time. HT participants received no training in MBSR or meditation. HT topics include physical activity, nutrition, weight, building health, personal care, and adolescence/emerging adulthood. HIV was not a program topic. HT groups were led by two health educators experienced with urban youth.

Usual care (UC) was a third study arm of standard clinical care, consisting of clinic visits and lab work (i.e., HIV viral load and CD4), scheduled every 3-6 months. Participants in the MBSR and HT groups also received usual clinical care. Due to slow recruitment, the UC arm was discontinued early in the study. There were no significant differences between the UC and HT participants, so they were collapsed into a combine HT/UC control group for analyses.

Measures

Participants completed self-report survey measures at four time points: baseline, 3 months (post-program), and six- and 12- month follow up. Validated surveys measured medication adherence and mindfulness. Data collection was conducted by study staff blinded to group assignment. HIV viral load (HIV VL) and CD4 counts during the study period were collected from the patient’s medical record by blinded study staff.

The primary outcome was HIV medication adherence (MA), measured by a 15- question self-report questionnaire (Chesney et al., 2000), assessing number of pills prescribed and taken/week, missed doses in past week, and barriers to taking medication. MA was estimated as the proportion of reported pills taken out of those prescribed for the prior week.

Two self-report measures assessed mindfulness: the Mindful Attention and Awareness scale (MAAS; MacKillop & Anderson, 2007) and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2006). The MAAS is 15 items focused on acceptance of and attention to the present moment, and has been used in prior samples of urban adolescents with HIV (Webb et al., 2018). The scale showed good reliability in this sample (α = .83-.90). The FFMQ is a 39-item self-report measure of five aspects of mindfulness (observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and non-reactivity to inner experience), which are combined to create an overall mindfulness score.

Participant MBSR and HT group attendance was tracked by study staff. Home mindfulness practice was assessed qualitatively through individual in-depth interviews (IDIs) with a subset of study participants, analyzed as described previously (Kerrigan et al, 2018). Eleven MBSR participants had IDIs at baseline, 8 of whom were interviewed at 3 months and 8 interviewed at 6 months. Ten of the 11 MBSR participants interviewed completed baseline and at least 1 follow-up; 6 completed all 3 IDIs.

Statistical Methods

Participant characteristics were compared between arms of the study as a randomization check using standard statistical comparisons (Table 1). The outcome variables of MA, mindfulness, and CD4 were modeled over time with generalized linear additive models, accounting for variable similarity within patient using a random patient-level intercept (Wu & Zhang, 2002). The difference between arms was estimated as the difference in change from enrollment to each follow-up time point. Prior research has shown associations between MA and individual-level factors, including gender (Manteuffel et. al., 2014) and socioeconomic status (McQuaid & Landier, 2017). We incorporated gender and maternal education, as an indicator for socioeconomic status, in our adjusted models.

Table 1.

Study participants by randomization.

| Factor | Overall (n=71) M(SD) or N(%) |

MBSR (n=32) M(SD) or N(%) |

HT/UC (n=39) M(SD) or N(%) |

p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment (years) | 20.46 (3.06) | 20.34 (3.17) | 20.56 (3.01) | 0.766 |

| Proportion Adherence (BL) | 0.77 (0.31) | 0.80 (0.31) | 0.75 (0.31) | 0.508 |

| Viral load (BL, copies/mL) | 6336 (22143) | 12887 (31752) | 961 (3862) | 0.043 |

| Log base 10 VL (BL) | 2.01 (1.17) | 2.37 (1.42) | 1.70 (0.82) | 0.023 |

| Viral load (% at or below 20) | 45 (63%) | 17 (53%) | 28 (72%) | 0.168 |

| CD4 count | 632.8 (286.7) | 558.6 (308.7) | 696.4 (254.8) | 0.089 |

| Race | 0.323 | |||

| Black | 65 (92%) | 31 (97%) | 34 (87%) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Other | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) | |

| White | 2 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Gender | 0.986 | |||

| Male | 36 (51%) | 16 (50%) | 20 (51%) | |

| Female | 33 (46%) | 15 (47%) | 18 (46%) | |

| Transgender (M to F) | 2 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Sexual orientation | 0.475 | |||

| Straight | 37 (52%) | 18 (56%) | 19 (49%) | |

| Gay or Lesbian | 21 (30%) | 7 (22%) | 14 (36%) | |

| Bisexual | 7 (10%) | 3 (9%) | 4 (10%) | |

| Something Else | 6 (8%) | 4 (12%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Education | 0.123 | |||

| 8th grade or less | 24 (34%) | 14 (44%) | 10 (26%) | |

| 9th – 11th | 5 (7%) | 3 (9%) | 2 (5%) | |

| HS Diploma | 26 (37%) | 7 (22%) | 19 (49%) | |

| HS Diploma + | 16 (23%) | 8 (25%) | 8 (21%) | |

| Maternal education | 0.090 | |||

| Less than high school | 8 (11%) | 6 (19%) | 2 (5%) | |

| High school graduate | 34 (48%) | 17 (53%) | 17 (44%) | |

| Unknown | 9 (13%) | 4 (12%) | 5 (13%) | |

| More than high school | 20 (28%) | 5 (16%) | 15 (38%) | |

| At Enrollment | ||||

| Mindfulness (MAAS) | 3.60 (1.09) | 3.74 (0.96) | 3.49 (1.19) | 0.331 |

| Mindfulness (FFMQ) | 123.94 (15.80) | 127.97 (12.91) | 120.60 (17.32) | 0.056 |

Comparison made with Student’s t test for continuous factors, and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact for categorical factors.

Participant HIV viral load (VL) was considered both in the log scale, as well as a yes/no measure of VL at or below the detection limit of 20 viral copies/mL. Log base 10 VL was modeled over time with linear additive mixed effect models, accounting for within-patient measurement using a random patient-level intercept (Bortz & Nelson, 2006). Whether VL was below detection or not was modeled with generalized linear additive models for binomial outcomes also with a patient level random intercept. Change in VL over time was examined in four time periods corresponding to those for data collection: enrollment to 1 month, 2-4 months, 5-7 months, and 8 or more months after enrollment. The difference for each time period from enrollment was estimated and compared between arms, in unadjusted and adjusted models. Analyses were conducted as intention-to-treat. To explore the impact of session attendance on MA and HIV VL, sub-analyses were conducted with the 57 participants who attended at least one MBSR or HT session.

Results

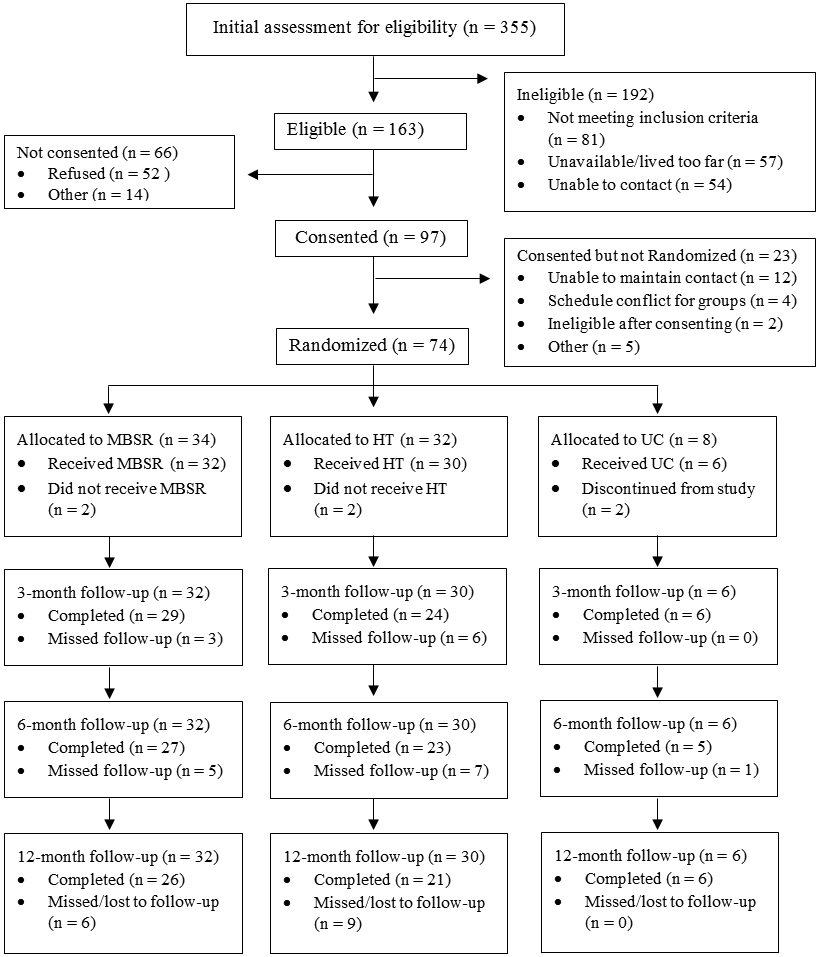

A total of 355 patients were assessed for study eligibility. One hundred ninety-two patients were ineligible, leaving 163 potentially eligible for enrollment. Of the 163 patients contacted, 52 declined and 97 (60% of those contacted) consented to study participation. Of the 97 consented participants, 23 were not randomized, related to the inability to maintain contact and discontinuation of groups, due to slow recruitment. Seventy-four 13-24 year old AYALH were enrolled in the study from February 2015 through August 2017; data were collected from February 2015 through August 2018. Thirty-four were randomized to MBSR; 32 to HT; and 8 to UC. HIV acquisition was 46% perinatal and 54% behavioral, not different by study arm (p = 0.84) or site (p = 0.61). Six participants were terminated/withdrew from the study after randomization, two from each arm, resulting in 68 participants, 78% of whom provided 12-month data (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

Study participants were on average 20.5 years old (SD 3.06; range 13-24 years); 92% non-Hispanic Black; 51% male, 46% female, 3% transgender (male to female); 52% self-identified as straight, 30% as gay/lesbian, 10% as bisexual, and 8% as something else; 34% had less than a ninth-grade education (reflecting younger participants), 60% had at least a high school diploma. At baseline, study participants self-reported HIV MA at 77% and the average HIV VL was 6,336 copies/mL. Between MBSR and HT/UC groups, there were no differences by age, race, gender, or sexual orientation. However, at baseline, the MBSR group had significantly higher HIV VL (12,887 vs. 961; p = 0.04) and log VL (2.37 vs. 1.70; p = 0.02), borderline lower maternal education, and borderline higher mindfulness (Table 1). Subsequent analyses took these baseline differences into account. Of nine program sessions, average MBSR attendance was 5.7 sessions (range 0-9), with 5 participants attending no sessions; average HT attendance was 5.3 (range 0-9), with 7 participants attending no sessions, not different by study arm (p = 0.44).

Self-reported MA did not differ between the MBSR and HT/UC arms at baseline (p = 0.508). Participants in both arms were more likely to be adherent at three months (OR = 1.81 95% CI 1.26-2.58, p = 0.001) and six months (OR = 3.95, 95% CI 2.62-5.95, p < 0.001) relative to enrollment. Those in the MBSR arm increased MA more than those in the HT/UC arm at three months (OR = 2.50, 95% CI 1.36-4.60, p = 0.003) but not at six or twelve months (Table 2; Figure 2).

Table 2.

Self-reported medication adherence by arm among study participants over the 12-month study period.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | |||||

| N = 71 | Estimate | 95% CI | p | Estimate | 95% CI | p |

| Arm | ||||||

| HT/Usual Care (ref) | 1.00 | - | - | 1.00 | - | - |

| MBSR | 1.32 | (0.55, 3.13) | 0.534 | 1.62 | (0.67, 3.91) | 0.288 |

| Time | ||||||

| Enrollment (ref) | 1.00 | - | - | 1.00 | - | - |

| 3-month follow-up | 1.53 | (1.09, 2.15) | 0.015 | 1.81 | (1.26, 2.58) | 0.001 |

| 6-month follow-up | 3.28 | (2.21, 4.88) | < 0.001 | 3.95 | (2.62, 5.95) | < 0.001 |

| 12-month follow-up | 1.07 | (0.76, 1.52) | 0.692 | 1.09 | (0.77, 1.54) | 0.639 |

| Interaction between Time and Arm | ||||||

| 3-month follow-up | 2.70 | (1.48, 4.91) | 0.001 | 2.50 | (1.36, 4.60) | 0.003 |

| 6-month follow-up | 1.32 | (0.69, 2.53) | 0.406 | 0.96 | (0.49, 1.88) | 0.907 |

| 12-month follow-up | 0.94 | (0.52, 1.71) | 0.840 | 0.76 | (0.41, 1.39) | 0.371 |

adjusted for age and maternal education.

Figure 2.

Self-reported medication adherence by study arm over 12 months (n = 71).

At baseline, HIV log VL was higher among participants in MBSR compared with HT/UC (estimate 10^(−.66) = 4.6 times higher among MBSR, p = 0.023). HIV log VL did not change over time among those in HT/UC. At three months, the HIV VL in MBSR participants decreased more than those in HT/UC at borderline significance (expected difference in HT/UC 10^(−.03) = 0.95 times viral load at enrollment, among MBSR expected different 10^(−.03−.55) = 0.26 times viral load at enrollment, p = 0.056; Table 3). Additional sub-analyses of participants who had attended any MBSR or HT group sessions (n = 57) showed a significant association between MBSR group assignment and decrease in HIV VL (p = 0.043). The percent of participants with HIV viral suppression (<20 copies/ml) at baseline was lower in the MBSR than the HT/UC arm; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.168), and there were no differences between study arms over the remaining study time period. There were no statistically significant differences between study arms in CD4 count at baseline or subsequent data collection time points (Table 4).

Table 3.

Log viral load among study participants by arm over the 12-month study period.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected log change | Expected log change | |||||

| N = 71 | Estimate | 95% CI | p | Estimate | 95% CI | p |

| Arm | ||||||

| HT/Usual Care (ref) | 1.00 | - | - | 1.00 | - | - |

| MBSR | 0.66 | (0.13, 1.20) | 0.018 | 0.55 | (0.01, 1.08) | 0.049 |

| Time | ||||||

| Enrollment (ref) | 1.00 | - | - | 1.00 | - | - |

| 3-month follow-up | −0.02 | (−0.40, 0.36) | 0.926 | −0.03 | (−0.41, 0.34) | 0.857 |

| 6-month follow-up | 0.11 | (−0.27, 0.50) | 0.568 | 0.12 | (−0.27, 0.50) | 0.554 |

| 12-month follow-up | 0.04 | (−0.26, 0.34) | 0.804 | 0.04 | (−0.27, 0.34) | 0.819 |

| Interaction between Time and Arm | ||||||

| 3-month follow-up | −0.57 | (−1.13, −0.01) | 0.052 | −0.55 | (−1.11, 0.00) | 0.056 |

| 6-month follow-up | −0.28 | (−0.85, 0.28) | 0.332 | −0.31 | (−0.87, 0.26) | 0.288 |

| 12-month follow-up | −0.15 | (−0.60, 0.29) | 0.508 | −0.15 | (−0.60, 0.29) | 0.505 |

adjusted for age and maternal education.

Table 4.

CD4 count among study participants by arm over the 12-month study period.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected change | Expected change | |||||

| N = 71 | Estimate | 95% CI | p | Estimate | 95% CI | p |

| Arm | ||||||

| HT/Usual Care (ref) | 1.00 | - | - | 1.00 | - | - |

| MBSR | −150.7 | (−300.8, −0.7) | 0.054 | −122.1 | (−271.7, 27.5) | 0.115 |

| Time | ||||||

| Enrollment (ref) | 1.00 | - | - | 1.00 | - | - |

| 3-month follow-up | 22.5 | (−64.2, 109.2) | 0.613 | 25.9 | (−60.8, 112.6) | 0.561 |

| 6-month follow-up | 51.3 | (−45.4, 148.0) | 0.302 | 52.8 | (−43.8, 149.4) | 0.288 |

| 12-month follow-up | 76.9 | (3.0, 150.8) | 0.046 | 78.8 | (5.0, 152.6) | 0.041 |

| Interaction between Time and Arm | ||||||

| 3-month follow-up | 14.1 | (−114.0, 142.2) | 0.830 | 12.1 | (−115.9, 140.1) | 0.853 |

| 6-month follow-up | −12.5 | (−150.4, 125.3) | 0.859 | −17.0 | (−154.9, 120.8) | 0.809 |

| 12-month follow-up | −16.5 | (−120.1, 87.2) | 0.757 | −19.2 | (−122.8, 84.3) | 0.717 |

adjusted for age and maternal education.

At baseline, MBSR participants endorsed borderline higher levels of mindfulness (p = 0.056) measured by the FFMQ. However, at 3 months, MBSR participants’ mindfulness (as measured by the MAAS, but not the FFMQ) had decreased (p = 0.001) more than the HT/UC group. At both six and 12 months, mindfulness was lower in the MBSR participants than in HT/UC, as measured by both the MAAS (p = 0.032, p = 0.005) and FFMQ (p = 0.044, p = 0.009) (Table 5).

Table 5:

Expected difference in mindfulness among study participants between arm over the 12-month study period.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 71 | Expected difference | Expected difference | ||||

| Estimate | 95% CI | p | Estimate | 95% CI | p | |

| 3 months ** | ||||||

| Mindfulness (MAAS) | −0.85 | (−1.32, −0.37) | 0.001 | −0.85 | (−1.33, −0.38) | 0.001 |

| Mindfulness (FFMQ) | −4.17 | (−11.65, 3.31) | 0.279 | −4.14 | (−11.67, 3.39) | 0.286 |

| 6 months ** | ||||||

| Mindfulness (MAAS) | −0.52 | (−1.01, −0.02) | 0.046 | −0.57 | (−1.07, −0.06) | 0.032 |

| Mindfulness (FFMQ) | −7.78 | (−15.42, −0.14) | 0.051 | −8.20 | (−16.00, −0.41) | 0.044 |

| 12 months ** | ||||||

| Mindfulness (MAAS) | −0.72 | (−1.22, −0.23) | 0.006 | −0.75 | (−1.25, −0.25) | 0.005 |

| Mindfulness (FFMQ) | −10.52 | (−18.12, −2.92) | 0.009 | −10.66 | (−18.32, −3.00) | 0.009 |

adjusted for age and maternal education.

difference in change from enrollment.

Uptake of mindfulness concepts and practices was assessed through IDIs in a subset of 11 MBSR participants. All but one participant interviewed reported using mindfulness practices outside of group sessions, and nearly all participants used mindfulness practices following the program completion. Participants discussed being more aware of their emotions and using the practices to calm down, de-stress, and/or re-center themselves. Most often, participants shared stories of using breathing exercises in situations creating anger, frustration, or stress, as illustrated here: “Like certain things be on my nerves, I try like do a breathing, I think she called it, Breathing Sensations. And I’ll do that, like if things get on my nerves I’ll stop in the middle of whatever is going on and just close my eyes and just take like three deep breaths and just pay attention to what I can hear and then come back, like woo sah.” (21-year-old female, perinatal acquisition); “So you know when sometimes something happens and your heart starts to pound and you feel like your adrenaline is pumping? When that happens I just try to calm myself down before I react, and that's when I use the breathing the most.” (23-year-old male, perinatal acquisition) A few participants described regular practice: ‘Body scan, awesome. I do that every morning when I wake up, "How am I feeling today? Am I angry? No, I'm not angry, I actually feel decent, I don't feel like I can take on a whole mountain right now, but I can probably take on a hill, maybe a little boulder, not too much.” (22-year-old male, behavioral acquisition)

Discussion

In this small RCT, MBSR participants had a significantly greater increase in HIV MA than those in the control. Additionally, HIV VL improvements mirrored the HIV MA in the MBSR arm compared with HT/UC, at borderline statistical significance. Related to mindfulness, there were baseline differences between arms, with MBSR participants having higher levels of mindfulness than HT/UC participants. The MBSR arm showed decreased mindfulness at all follow-up time points. Given the significant challenges with ART among AYALH, the findings that MBSR improved MA post-program suggest that MBSR may have a role in improving HIV MA and further research is merited.

During the complex developmental period of adolescence and young adulthood, ART adherence is a significant challenge. Unfortunately, only 30% of AYALH are virally suppressed, about half the rate of other ages combined (CDC 2020a). This represents a significant challenge to efforts aimed at reducing transmission and further fuels the HIV epidemic in this vulnerable population. Although HIV MA did not differ between study arms at baseline, the MBSR group had significantly greater HIV log VL than the HT/UC group and fewer virally suppressed participants at borderline significance. This difference at baseline may have made it more difficult to detect the effect of program participation, especially given the modest sample size. Nevertheless, the simultaneous improvement in HIV MA and trending improvement in HIV VL at three months are suggestive of MBSR program may benefit on HIV MA and related VL. This is corroborated by 1) the sub-analysis of participants who attended MBSR or HT sessions, showing a significant association between MBSR and decreased HIV VL and 2) qualitative research finding that MBSR participants experienced improved MA, perceived to be related to increased acceptance of their HIV disease and decreased internalized stigma, as well as better management of pill-taking and side effects (Kerrigan et al., 2018). These IDI participants conveyed that MBSR taught them how to observe difficult thoughts and feelings, whether thoughts and feelings of judgment and shame related to living with HIV or frustration and discomfort surrounding daily oral ART, without judgment. They learned how to let these thoughts and experiences go, rather than internalizing them and allowing them to negatively impact their ART adherence, as they relayed had often happened prior to MBSR. Participants perceived that mindfulness instruction facilitated HIV MA by reducing internal barriers as well as providing in-the-moment skills that supported pill-taking and MA (Kerrigan et al., 2018).

The differences between study arms at baseline in mindfulness present a limitation for these analyses. Although adult studies typically detect changes in mindfulness (e.g., Carmody & Baer, 2008), our previous studies with youth have inconsistently identified increases in mindfulness related to MBSR (Sibinga et al., 2013; Sibinga et al., 2016; Webb et al., 2018). Further, it is often noted that instruction of mindfulness itself can lead to the recognition of how mindless we often are (Baer, 2011). Thus, increased self-awareness of mindlessness could affect self-reported levels of mindfulness. Despite study limitations of baseline group imbalance and modest sample size limiting statistical power, study strengths include the randomized, active control design and high retention, given the hard-to-reach population. In addition, robust instruments of psychological function, coping, and cognitive flexibility were systematically implemented with good reliability and validity.

Given the significant challenges associated with MA in AYALH and the vulnerability of this age range and population, multi-faceted and sustained intervention approaches are needed to improve care and treatment outcomes and to interrupt HIV transmission in such high-risk populations. This RCT suggests that MBSR is feasible and acceptable among many AYALH and has the potential to improve HIV MA and decrease HIV VL, meriting further investigation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study participants for their time and commitment, as well as, the project staff -- Tracey Chambers Thomas, Jan Stevenson; MBSR instructors -- Tawanna Kane and Mira Tessman; and Health education instructors -- McCay Moiforay and Keyya Simmons.

Funding

This work was supported by National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health [grant number R01AT007888]; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [grant number P30AI094189]; Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research [grant number 1P30AI094189]

References

- Baer RA (2011). Measuring mindfulness. Contemporary Buddhism: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 12(1), 241–261. doi: 10.1080/14639947.2011.564842 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, & Toney L (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortz DM, & Nelson PW (2006). Model selection and mixed-effects modeling of HIV infection dynamics. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 68(8), 2005–2025. doi: 10.1007/s11538-006-9084-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Witkiewitz K, Clifasefi SL, Grow J, Chawla N, Hsu SH, Carroll HA, Harrop E, Collins SE, Lustyk MK, Larimer ME. Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014. May;71(5):547–56. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody J, & Baer R (2008). Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31(1), 23–33. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9130-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a, May 18). HIV and youth. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/youth/index.html#:~:text=Stigma%20and%20misperceptions%20about%20HIV%20negatively%20affect%20the%20health%20and,24%2C%20especially%20youth%20of%20color.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b, May). HIV surveillance report, 2018 (updated), vol. 31. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-31.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwicki B, & Wu A (2000). Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: The AACTG adherence instruments. AIDS Care, 12(3), 255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. (2020, May 8). Ending the HIV Epidemic: Plan for America overview. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview

- Kabat-Zinn J (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Dell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan D, Johnson K, Steward M, Magyari T, Hutton N, Ellen JM, & Sibinga EMS (2011). Perceptions, experiences, and shifts in perspective occurring among urban youth participating in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 17, 96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan D, Grieb SM, Ellen J, & Sibinga EMS (2018). Exploring the dynamics of ART adherence in the context of a mindfulness instruction intervention among youth living with HIV in Baltimore, Maryland. AIDS Care, 30(11), 1400–1405. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1492699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, & Anderson EJ (2007). Further psychometric validation of the Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29(4), 289–293. doi: 10.1007/s10862-007-9045-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manteuffel M, Williams S, Chen W, Verbrugge RR, Pittman DG, Steinkellner A. Influence of patient sex and gender on medication use, adherence, and prescribing alignment with guidelines. Journal of women's health. 2014. Feb 1;23(2):112–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw-Hill. (2005). http://www.glencoe.com/sec/health/th12005/index.php/md

- McQuaid EL, Landier W. Cultural issues in medication adherence: disparities and directions. Journal of general internal medicine. 2018. Feb;33(2):200–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, Fletcher K, Kabat-Zinn J. Three-year follow-up and clinical implications of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention in the treatment of anxiety disorders. General hospital psychiatry. 1995. May 1;17(3):192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibinga EMS, Kerrigan D, Steward M, Johnson K, Magyari T, & Ellen JM (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for urban youth. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 17(3), 213–218. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibinga EMS, Perry-Parrish C, Chung S, Johnson SB, Smith M, & Ellen JM (2013). School-based mindfulness instruction for urban male youth: A small randomized controlled trial. Preventive Medicine, 57(6), 799–801. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibinga EMS, Stewart M, Magyari T, Welsh CK, Hutton N, & Ellen JM (2008). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for HIV-infected youth: A pilot study. EXPLORE, 4(1), 36–37. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2007.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibinga EM, Webb L, Ghazarian S, & Ellen JM (2016). School-based mindfulness instruction: An RCT. Pediatrics, 137(1), e20152532. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2020, June 17). National population by characteristics: 2010-2019. https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-national-detail.html?#par_textimage_1223450682

- Webb L, Perry-Parrish C, Ellen J, & Sibinga E (2018). Mindfulness instruction for HIV-infected youth: A randomized controlled trial. AIDS Care, 30(6), 688–695. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1394434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, & Zhang JT (2002). The study of long-term HIV dynamics using semi-parametric non-linear mixed-effects models. Statistics in Medicine, 21(23), 3655–3675. doi: 10.1002/sim.1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]