Abstract

Background:

Ablation of ventricular tachycardia (VT) in the setting of structural heart disease often requires extensive substrate elimination which is not always achievable by endocardial radiofrequency ablation. Epicardial ablation is not always feasible. Case reports suggest that venous ethanol ablation (VEA) via multi-balloon, multi-vein approach can lead to effective substrate ablation, but large data sets are lacking.

Methods:

VEA was performed in 44 consecutive patients with ablation-refractory VT (ischemic, N=21; sarcoid, N=3; Chagas, N=2; idiopathic, N=18). Targeted veins were selected by mapping coronary veins on the epicardial aspect of endocardial scar (identified by bipolar voltage <1.5mV), using venography and signal recording with 2F octapolar catheter or by guide-wire unipolar signals. Epicardial mapping was performed in 15 patients. Vein segments in the epicardial aspect of VT substrates were treated with double-balloon VEA by blocking flow with one balloon while injecting ethanol via the lumen of the second balloon, forcing (and restricting) ethanol between balloons. Multiple balloon deployments and multiple veins were used as needed. In 22 patients, late-gadolinium enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance imaged VEA scar and its evolution.

Results:

Median ethanol delivered was 8.75 [IQR 4.5–13] mL. Injected veins included interventricular vein (6), diagonal (5), septal (12), lateral (16), posterolateral (7), and middle cardiac vein (8), covering the entire range of left ventricular locations. Multiple veins were targeted in 14 patients. Ablated areas were visualized intraprocedurally as increased echogenicity on intracardiac echocardiography and incorporated into 3D maps. Post-VEA vein and epicardial maps showed elimination of abnormal electrograms of the VT substrate. Intracardiac echocardiography demonstrated increased intramural echogenicity at the targeted region of the 3D maps. At one year of follow-up -median of 314 (IQR 198–453) days- of follow-up, VT recurrence occurred in 7 patients, for a success of 84.1%.

Conclusion:

Multi-balloon, multi-vein intramural ablation by VEA can provide effective substrate ablation in patients with ablation-refractory VT in the setting of structural heart disease over a broad range of left ventricular locations.

Keywords: ethanol, ablation, ventricular vein, ventricular arrhythmias

Introduction

Catheter ablation is a guideline-recommended first-line therapy for ventricular tachycardia (VT) in the setting of ischemic heart disease or nonischemic cardiomyopathy.1 Although recent data support ablation early in the course of VT management,2–4 most centers resort to ablation after failed antiarrhythmic therapy. For decades, ablation of VT in structural heart disease has relied on targeting culprit myocardium via endocardial or epicardial catheterization to create lesions – most commonly using radiofrequency ablation (RFA)- at the VT substrates. While this approach has led to considerable success, suboptimal results are common. Most ablation failures occur when intramyocardial arrhythmogenic substrates are not reachable from an endocardial approach.5

In previous reports, combined endo-epicardial ablation, compared with endocardial ablation alone, has shown a significant benefit.6–11 Overall, a combined epicardial-endocardial approach leads to a success rate of 83%, compared to 63% with an endocardial-only approach.12 Although epicardial ablation can improve results, technical aspects limit its applicability in up to 40% of attempted patients,13 due to unfeasible epicardial access, or to proximity of the VT substrate to coronary arteries or the phrenic nerve.14 Thus, ablation approaches that reach intramyocardial or subepicardial substrates are desirable.

The venous circulation is a rich vasculature reaching the entire left ventricular (LV) myocardium, is easily accessible via the coronary sinus (CS) using routine cannulation techniques, and is free of atherosclerotic disease. We have developed an approach to target ablation-refractory VT via ethanol delivery in the coronary veins that provide venous return from arrhythmogenic sites (venous ethanol ablation, VEA).15–17 Beyond an initial set of case reports in focal VT or extrasystoles -primarily limited VEA for limited ablation in the LV summit-15–18 we adapted the technique for large substrate ablation using double balloon techniques that allow for the sequential injection of ethanol along an epicardial vein to achieve large substrate ablation.19

Here we evaluated the efficacy of VEA in multi-balloon, multi-vein strategies for VT substrate ablation in patients with intramyocardial substrates and prior endocardial or epicardial ablation failures. We validate the safety and efficacy of the VEA approach for large substrate VT ablation.

Methods

Patient selection

VEA approaches were evaluated in 44 consecutive patients after a failed RFA attempt, either a previously failed ablation procedure (N=40) or intraprocedurally if RFA failed (N=4). Ethanol is FDA-approved for ventricular septal ablation. Our group has also been performing “off label” ethanol ablation for treatment of ventricular arrhythmias in selected patients when standard approaches failed.19 Patients were not prospectively assigned to undergo VEA. Rather, after obtaining clinical consent for the procedure, operators used this technique when deemed clinically appropriate. Subsequently, data was collected from patients who had undergone the procedure via an IRB-approved data collection protocol with waiver of informed research consent. Patients with ventricular extrasystoles without structural heart disease were excluded. Evidence of structural heart disease was established by echocardiography demonstrating significant depression of LV ejection fraction (<45%), or by late-gadolinium enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance (LGE-CMR) showing at least 5% scar in the origin of VT. To define ischemic origin of cardiomyopathy, presence of coronary artery disease was established by nuclear perfusion imaging, coronary computerized tomography angiogram, or invasive coronarography.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Procedural approach

The initial procedural approach and techniques have been previously described.16, 17

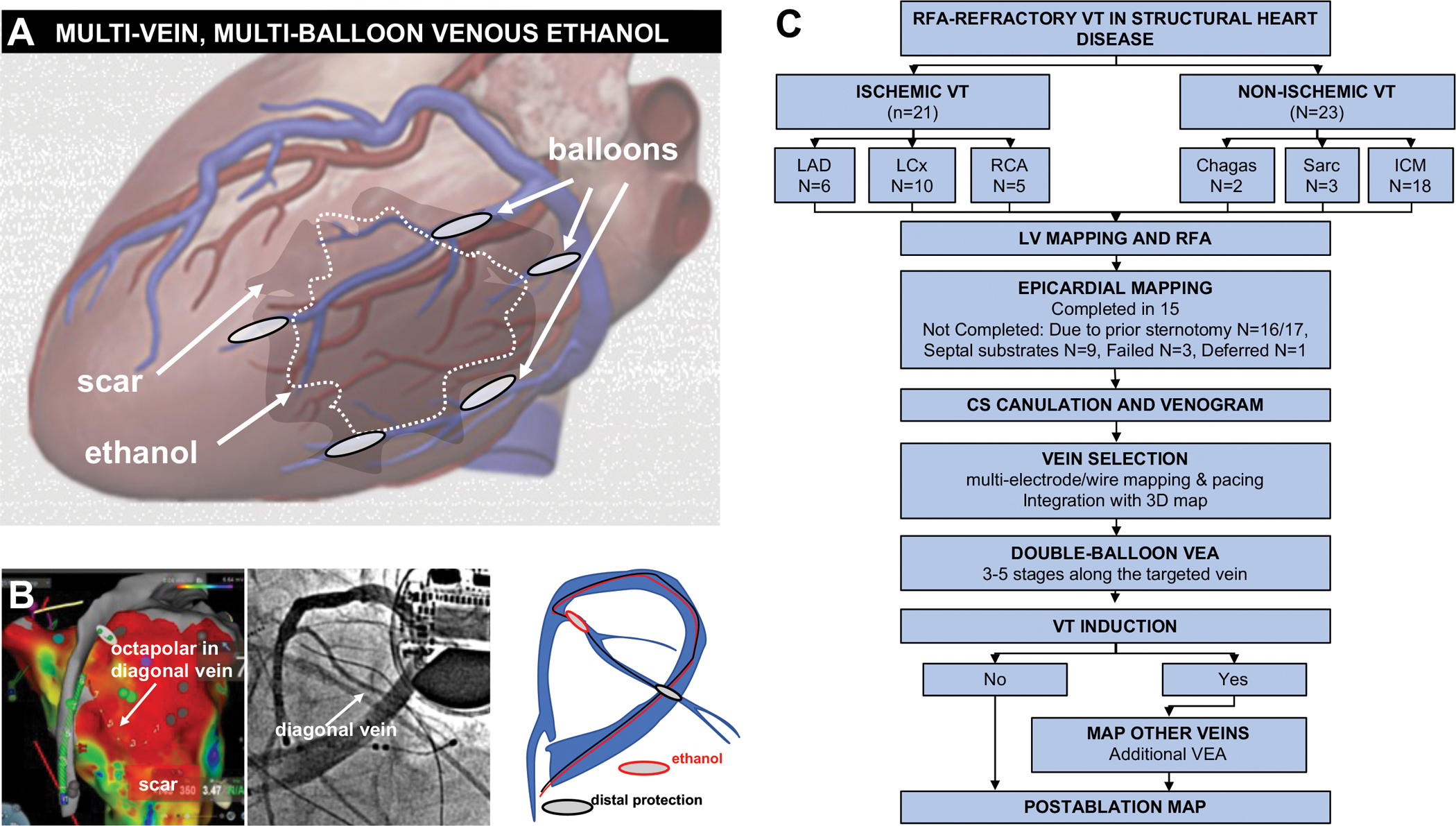

Figure 1 outlines patient flow and overall technique.

Figure 1.

Procedural approach and patient flow. A, schematic of the procedural approach. After delineating the scar -VT substrate- location, epicardial veins overlying the substrate are cannulated using the double-balloon approach. VEA aims to deliver ethanol to the substrate via its venous return. B, example in one patient showing the scar map with overlying vein, the venogram, and the double balloon approach. C, patient flow. LAD: left anterior descending. LCx: left circumflex. RCA: right coronary artery. Sarc: sarcoidosis.

Endocardial mapping and ablation.

The LV was accessed using a retrograde aortic approach or an atrial transeptal approach after heparin administration. Bipolar and unipolar voltage 3D electroanatomic maps of the LV maps in sinus (or paced) rhythm were used to identify VT substrate, using a roving multipolar catheter (PentaRay®, Biosense-Webster, Irvine, CA). Myocardial scar was defined as confluent sites with bipolar signal amplitude <1.5 mV.20 Pace-mapping from the scar border was performed as needed, using standard criteria.21 RF was delivered in the VT substrate, targeting inability to capture myocardium post-ablation, elimination of all late potentials (discrete potential occurring after the QRS),21 or where pacing resulted in stimulus to QRS delay >45 msec,21 with goals to achieve complete scar de-channeling,22 and scar core isolation.23

If sustained hemodynamically tolerated VT was induced, then activation mapping was undertaken.24 Targeted sites were those located in the VT isthmus, as defined by late or mid-diastolic potential and by entrainment mapping.25

Irrigated RF was delivered at up to 45W for up to 60 seconds at any single site, with an endpoint of termination and subsequent non-inducibility of VT. Either in during the index procedure, or at a subsequent procedure, patients with RFA failures were then subjected to venous mapping and VEA.

Epicardial mapping.

In the absence of prior sternotomy or septal substrates, epicardial access was attempted. In 15/44 (34%) patients, epicardial access was obtained using the Sosa technique,26 modified for anterior subxiphoid puncture. A multipolar catheter (PentaRay®, Biosense) was used to create a 3D electroanatomical maps of VT activation and voltage amplitude of the epicardial surface. Late potentials and sites of matching pace-maps were marked. In 14/15 cases, epicardial RFA preceded VEA (1 had proximity to coronary artery).

Coronary venous mapping.

Either via the femoral, or right internal jugular vein, a sheath (8F Preface, Biosense-Webster, Irvine, CA, or Agilis, Abbott, St Paul, MN) were engaged in the CS. Femoral access was chosen for lateral veins and AIV, while interval jugular access was preferred for MCV and its branches. We then advanced a decapolar catheter (DecaNav, Biosense) in the CS, engaging if possible, the CS branches close to the myocardial scar. Contrast injection in the CS was performed to identify branches. Depending on the size, a smaller multipolar catheter (4F IBI decapolar, or 2F EPStar -Baylis, Toronto, CA) were introduced in LV veins. Pacing and entrainment mapping were performed from LV veins closest to the scar.

Venous ethanol infusion.

When needed, a sub-selector catheter (8F JR4 angioplasty guide catheter) was used to direct 2 angioplasty wires into specific veins of the VT substrate -otherwise, wires were advanced through the CS sheath. Balloons (2–4 mm diameter, 6–10 mm length, over-the-wire) were advanced to the most distal aspect of the selected vein in the portion overlapping the myocardial scar, as guided by 3D mapping. Balloon size was chosen based on the targeted vein caliber. The balloons were positioned with ~2 cm of vein in between the proximal and the distal balloon, and inflated. Contrast was injected via the proximal balloon lumen to verify that both balloons were occlusive. Once confirmed, 2 to 4 consecutive injections of 1 cc 96–98% ethanol were performed. Contrast injection via the proximal balloon lumen followed, to verify myocardial staining and demonstrate the extent of myocardial ethanol reach. Ethanol dose (2–4 injections per injection site, depending on inter-balloon distance) was chosen based on our previous experience, that supported the lesion consolidation effect achieved by repeated injections.16, 17 Contrast was injected between ethanol injections to assess extent of myocardial staining. If extensive, only 2 cc ethanol were delivered, if limited, up to 4. The balloons were then deflated, retracted 2–3 cm and reinflated in more proximally for repeat ethanol injection. From distal to proximal, sequential balloon repositioning was performed to cover the entire vein in the portion overlapping the myocardial scar (using integration with 3D maps), in 3–5 stages.27

Induction attempts were repeated after VEA in each targeted vein. If VT remained inducible -same or different morphology after initial VEA treatment- additional veins in the scar were mapped and subjected to VEA following the same approach. In cases of smaller veins without collateral flow to other veins, a single-balloon approach was taken. In cases of vein tortuosity impeding advancement of the balloon into the targeted location, a FineCross® (Terumo, Japan) was used to deliver ethanol.

Procedural endpoints.

After vein mapping and VEA, repeat voltage mapping was undertaken and repeat induction attempts were performed. Inducible VT was mapped and subjected to RFA as needed.

Intracardiac Echocardiography (ICE)

The VEA procedure was guided by ICE (SoundStar 10F, Biosense Webster). The ICE catheter advanced into the right atrium and ventricle, directing the ultrasound beam towards the VT substrate by integration with the electroanatomical maps using CartoSound software. Baseline images were stored and compared with subsequent imaging after VEA, which led to new echogenic areas where ethanol was injected. The contour of echogenic areas were recorded in serial images to create 3-dimensional (3D) estimates of their volume and to incorporate them in the maps for 3D localization using CartoSound.

Peri-procedural imaging: LGE-CMR protocol.

Twenty-two patients had LGE-CMR before and after the procedure. Either 1.5-T or 3.0-T CMR scanners (Siemens Avanto, Aera, or Verio; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with phased-array coil systems were used. Late gadolinium imaging was performed using a magnitude and phase-sensitive segmented inversion-recovery sequence, approximately 10 min after intravenous gadolinium contrast administration (gadopentetate dimeglumine or gadoterate meglumine, 0.15 mmol/kg). Parameters were in-plane spatial resolution of 1.8 × 1.3 mm and slice thickness of 6 mm, with inversion time adjusted to null normal myocardium. Cine- and LGE-CMR images were obtained in matching short- and long-axis planes. Shimming and delta frequency adjustments were applied to minimize off-resonance artifacts.

LGE was only considered present if it was visually identified on 2 contiguous or orthogonal slices and seen on both magnitude and phase-sensitive image reconstruction. Quantification of scar was performed using the full width half maximum method. Manual adjustments were made by a level III certified reader to exclude artifacts. All analyses were done on the same software (Precession, Heart Imaging Technologies).

Follow-up

Patients remained on the pre-procedure antiarrhythmic regime after the procedure. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) programming remained at the previous settings that had detected and treated VT pre-procedure. Patients were followed-up at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months post-procedure, with ICD interrogations. On the 1-month follow-up, if no further VT had occurred, antiarrhythmic drugs were de-escalated: first, high-dose amiodarone was decreased. For patients on combined antiarrhythmics, the non-amiodarone drug was discontinued first, followed by decreasing amiodarone dose in subsequent visits. Recurrence was defined as the presence of sustained VT requiring ICD therapies. All VT episodes were quantified for 3 months before and after the VEA procedure.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile ranges if not normally distributed (tested by Shapiro-Wilk test). Categorical variables are displayed as numbers and percentages. Comparison of VT burden before and after VEA were performed with Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Kaplan-Meier plots were used to show time to recurrence. Recurrence in ischemic vs non-ischemic VT substrates were compared with X2 test. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The 44 patients included had a median of 69.6 [61–78] years of age and 5 of them (11.4%) were women. Most common comorbidities included hypertension in 30 (68%), hyperlipidemia in 18 (341%), diabetes mellitus in 12 (27%), chronic kidney disease in 10 (23%), and coronary artery disease in 21 (48%). Prior sternotomy had been performed in 17 patients (38.9%). Forty-one (93%) patients had an ICD at the time of ablation. In the remaining 3, ICD implantation followed the VEA procedure in the same hospitalization. Eight patients had a previously implanted left ventricular assist device. Left ventricular fraction was 26% [17–35]. Beta-blocker therapy was prescribed in 42 patients (95%). Antiarrhythmic therapy had been administered in 41 patients (amiodarone in 37, sotalol in 9, mexiletine in 2, lidocaine in 13 -combined with amiodarone in 11). All but five patients had undergone a median of 2 prior ablation procedures (range 1–3), including 3 patients that had prior epicardial ablation. Of the 21 patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, six patients had VT substrates in the left anterior descending artery distribution (anterior, anteroseptal, anterolateral, or apical scar), ten had VT substrates in the circumflex artery distribution (lateral scar), and five had VT substrates in the right coronary artery distribution (inferior or infero-posterior scar). Of the 23 patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy, two had Chagas disease, three had cardiac sarcoidosis, and 18 had idiopathic forms of cardiomyopathy.

Half of the patients were enrolled after they had received more than 3 ICD therapies within 24 hours (electrical storm), and were receiving intravenous antiarrhythmic drugs. Table 1 shows the patient characteristics.

Table.

Patient characteristics

| Age (median, range) (years) | 69.6 | (33–81) |

| Sex (n) (%) | ||

| Male | 39 | (88.6) |

| Female | 5 | (11.4) |

| Race (n) (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 38 | (86.4) |

| Black | 6 | (13.6) |

| Asian | 0 | |

| Type of Cardiomyopathy | ||

| Ischemic | 21 | (47.7) |

| LAD | 6 | (13.6) |

| LCx | 10 | (22.7) |

| RCA | 5 | (11.4) |

| Non-ischemic | 23 | (52.3) |

| Idiopathic | 18 | (40.9) |

| Sarcoidosis | 3 | (6.8) |

| Chagas | 2 | (4.5) |

| Prior sternotomy | 17 | (38.6) |

| Pior Left ventricular assist device | 8 | (18) |

| NYHA Class | ||

| I | 3 | (6.8) |

| II | 11 | (25) |

| III | 21 | (47.7) |

| IV | 9 | (20.5) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) (range) | 26 | (10–60) |

| Total of previous ablation procedures (number) (%) | ||

| 0 | 5 | (11.4) |

| 1 | 23 | (52.3) |

| 2 | 11 | (25) |

| 3 | 5 | (11.4) |

| Indication (number) (%) | ||

| VT storm | 22 | (50) |

| VT therapies despite antiarrhythmics | 22 | (50) |

| Antiarrhythmic treatment | ||

| Amiodarone (> 200 mg twice a day, or intravenous) | 21 | (47.7) |

| Amiodarone (≤200 mg twice a day) | 12 | (27.3) |

| Sotalol | 9 | (20.5) |

| Lidocaine | 13 | (29.5) |

| Mexiletine | 12 | (27.3) |

| Combination | 23 | (52.3) |

| Other medications | ||

| Beta-blocker | 42 | (95.5) |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor | 29 | (65.9) |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 12 | (27.3) |

| Digoxin | 9 | (20.5) |

| Hypertension | 30 | (68.2) |

| Chronic kidney disease stage ≥3 | 12 | (27.3) |

| Hemodialysis | 1 | (2.2) |

Procedural parameters

Mean total procedure time was 294±82.1 minutes. Fluoroscopy time was 37±21 minutes. Total contrast administered was 100 cc [IQR 71.5–128.5]. Injected veins included anterior interventricular vein (AIV, 6), diagonal (5), septal (12), lateral (16), posterolateral (7), and middle cardiac vein (MCV, 8), covering the entire range of left ventricular (LV) locations. Total ethanol injected was 8.75 mL [IQR 4.5–13, range 2–36]. Multiple veins were targeted in 14 patients. Epicardial mapping and ablation was concomitantly performed in 15 patients -including one with prior sternotomy.

Procedural approaches in ischemic VT substrates

The initial approach in 21 ischemic cardiomyopathy patients included defining the VT substrate by endocardial voltage and activation mapping, followed by RFA ablation. In prior ablation failures, epicardial mapping was attempted at the outset (successful in 4). Otherwise, venous mapping followed. Prior sternotomy (in 15 patients) precluded epicardial mapping in 14/15. In the remaining 3 patients, epicardial access was not successful.

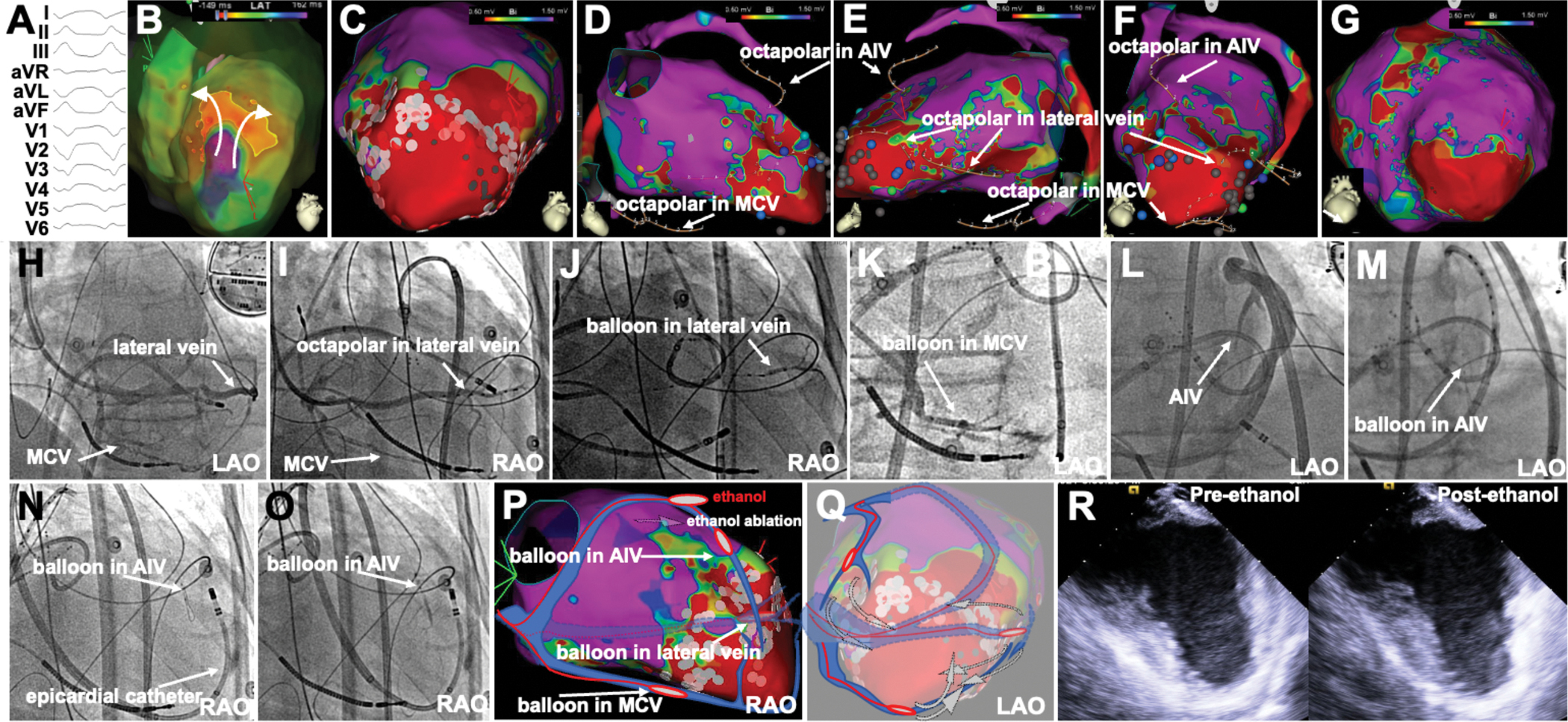

Figure 2 shows multi-vein VEA in a patient with ischemic cardiomyopathy, a large apical aneurysm and 2 previously failed endocardial ablations of VT. The patient had sustained a large anterior wall myocardial infarction from occlusion of the left anterior descending artery, and had disease in the left circumflex artery as well. Epicardial and endocardial maps demonstrated low-voltage areas in the apex (Figure 2C and 2G) and along the lateral wall (Figure 2DEF). After endocardial and epicardial ablation, the apex was rendered unexcitable, but VT remained inducible. Mapping of coronary veins revealed that the apical aneurysm could be reached through the distal AIV anteriorly, the distal MCV inferiorly, and a lateral vein laterally (Figure 2DEF). Sequential VEA was delivered via the lateral vein (Figure 2HIJ), the MCV (Figure 2K), and the AIV (Figure 2L–O), for a triple-vein approach of epicardial to endocardial ablation as shown schematically in Figure 2PQ. Increased intramural echogenicity of the apical aneurysm was apparent on ICE (Figure 2R). VT was not inducible after VEA.

Figure 2.

Triple-vein VEA in ischemic VT caused by apical infarct. A, 12-lead ECG of the VT. B, endocardial activation map showing reentry in the apex. C, endocardial voltage map showing epical scar and RFA lesions. D-E-F, 3D anatomy of the epicardial veins in relationship with the endocardial map and apical scar, showing the consecutive positioning of the octapolar catheter in the lateral, middle cardiac (MCV) and anterior interventricular (AIV) veins. G, epicardial voltage map. H-I-J, lateral vein venogram (H), octapolar cannulation (I) and balloon for VEA (J). K, VEA via balloon in MCV. L-M-N-O, AIV venogram, balloon cannulation and VEA in AIV. P-Q: localization of targeted veins and VEA relative to the apical scar. R, apical echogenicity increases after VEA. RAO, LAO, right and left anterior oblique projection, respectively.

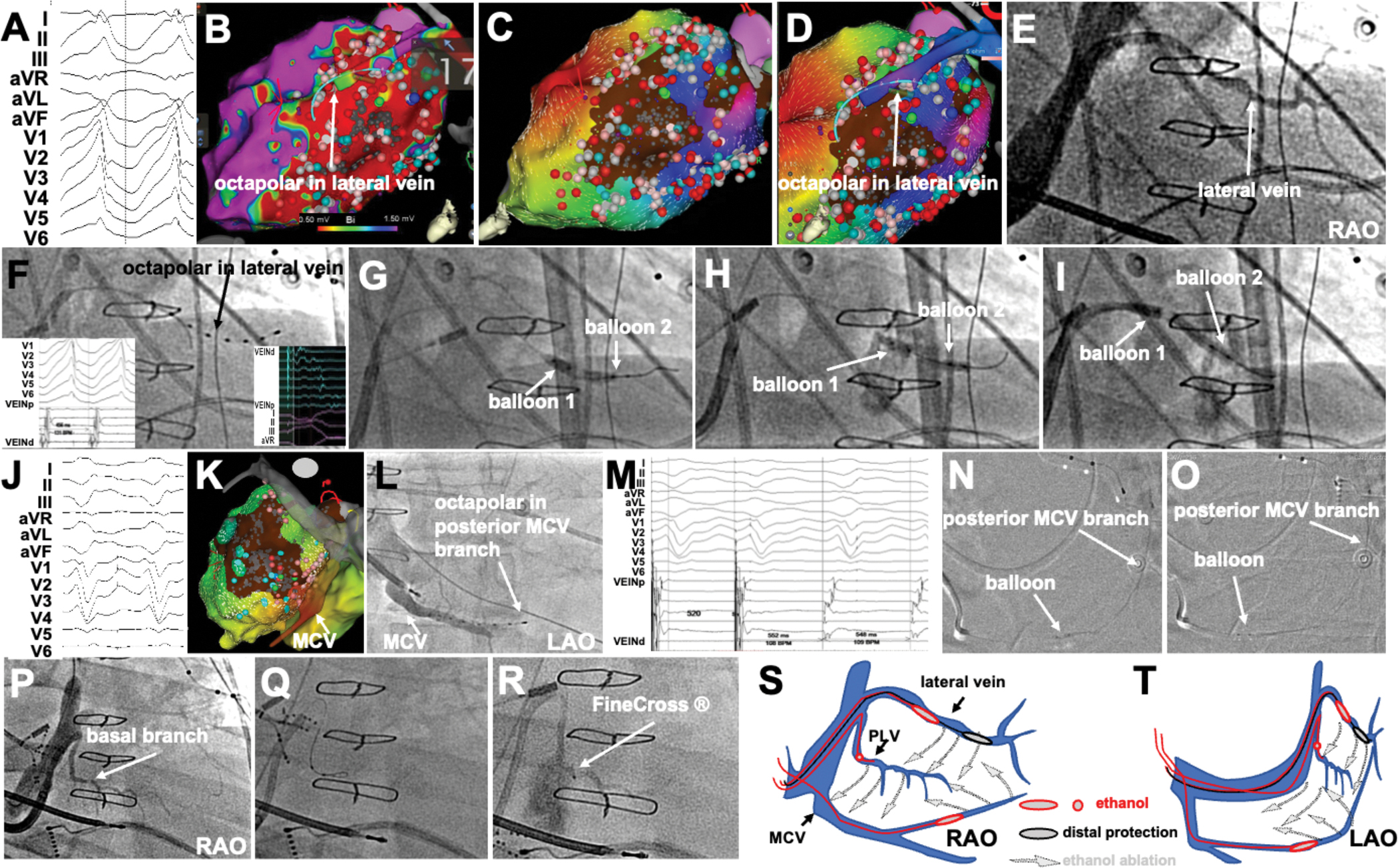

Figure 3 shows multi-balloon, multi-vein VEA in a patient with ischemic cardiomyopathy, a large lateral infarct from circumflex artery disease and recurrent VT despite 2 ablations. Epicardial access was not possible due to adhesions. One VT morphology appeared to have epicardial exit based on EKG morphology (Figure 3A). Endocardial maps showed a large low-voltage area in the lateral LV wall. After endocardial ablation, the endocardial scar was unexcitable and yet VT remained inducible. Activation maps suggested a VT exit from the lateral aspect of the scar. A large lateral vein was present on the epicardial aspect of the endocardial scar (Figure 3DE), and mid-diastolic signals were recorded there (Figure 3F). A double-balloon strategy was used to deliver ethanol along the lateral vein, from distal to proximal, aiming to achieve myocardial staining (Figure 3GHI). After VEA was delivered, a second VT was induced, and its exit mapped at the inferior septal aspect of the lateral scar (Figure 3JK). This required mapping of a posterior branch of the MCV, where signals and entrainment suggested proximity to the exit site. However, the multielectrode catheter could only be advanced to the proximal aspect of the vein, which ran towards the scar. VEA was delivered there (Figure 3NO). Repeat induction attempts led to re-induction of the first VT. A basal posterolateral branch of the lateral vein targeted earlier was found, and VEA there rendered VT not inducible. Thus a triple-vein, multi-balloon approach was used to completely eliminate VT substrates not feasible by endocardial ablation.

Figure 3.

Multi-vein VEA in ischemic VT caused by a lateral (circumflex artery) infarct. A, 12-lead ECG of the VT. B, bipolar voltage map of the LV endocardium showing large scar with the location of lateral vein superimposed on it. C, after extensive endocardial ablation, activation map supports exit site at the lateral edge of the scar. D, Lateral vein activation supports epicardial activation preceding exit site. E-F, Lateral vein venogram and cannulation with octapolar catheter (signals in VT and paced rhythm in F insets). G-H-I, sequential double-balloon deployments for lateral vein VEA. J-K, second VT induced, with exit site mapped at the septal edge of the scar. L-M, octapolar catheter in a branch of the middle cardiac vein (MCV), and corresponding signals and entrainment suggesting location at exit site. N-O, balloon in posterior MCV branch for VEA. P-R, VEA in basal branch of lateral vein. S-T, schematics of multi-vein, multi-balloon VEA.

Figure 1 of the online supplement shows VEA in a patient with a large infarct extending from the basal and mid septum to the infero-posterior wall (Figure 3A), from an infarct in a large, dominant right coronary artery. VEA was delivered in a posterolateral vein as well as in the middle cardiac vein. Of note, approaching these veins required cannulating the coronary sinus from the right internal jugular vein. Thus, ischemic VT substrates from all 3 coronary artery distributions were treated with VEA.

Procedural approaches in non-ischemic VT substrates

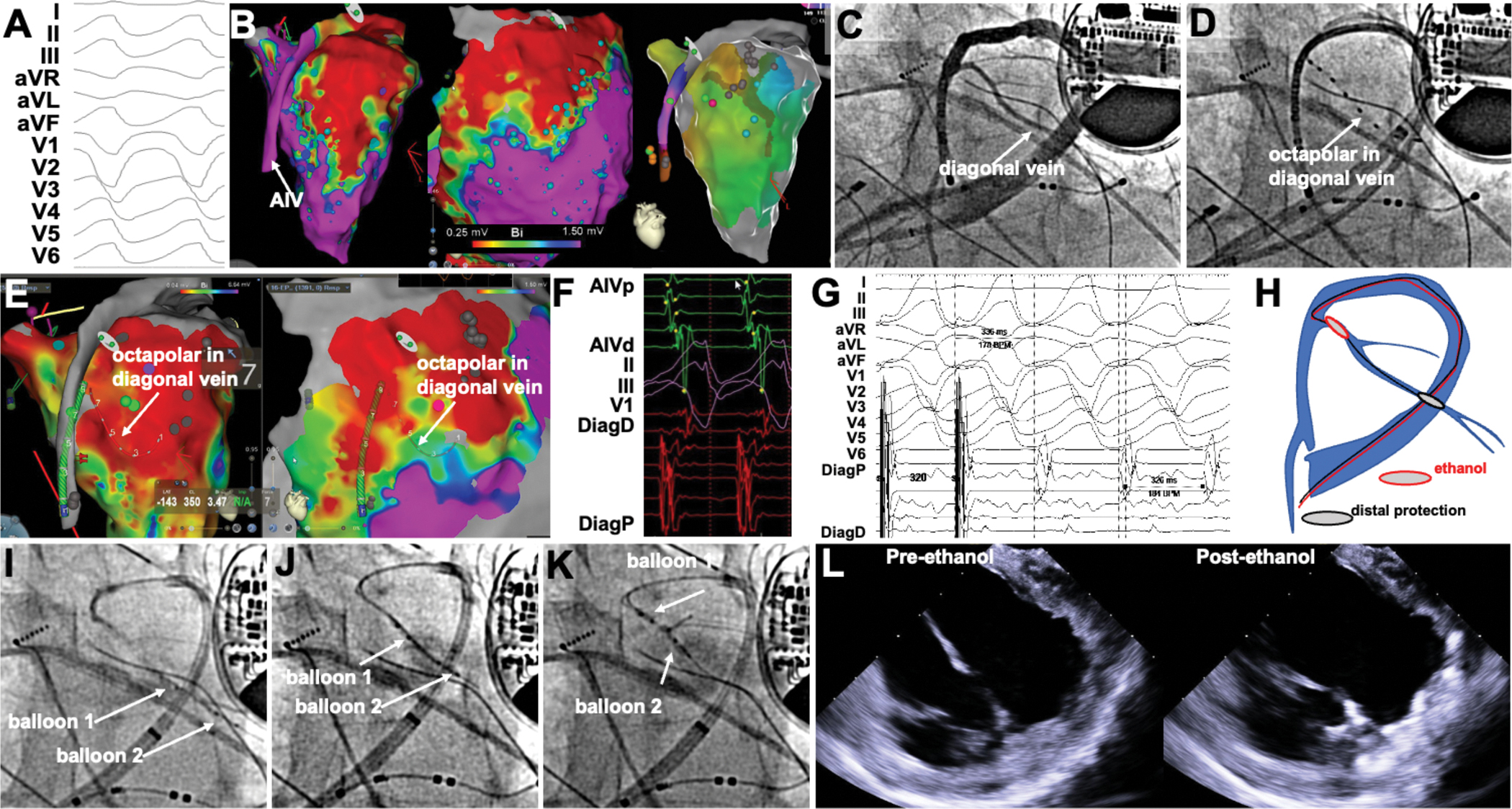

In 23 patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, endocardial mapping and ablation was followed by venous mapping. Epicardial access was obtained from the outset in 11 patients. In the remaining 12, epicardial access was not attempted because of septal substrates (N=9), or due to prior sternotomy (N=2), and was deferred in 1 -in whom VEA was successful. Figure 4 shows an example of VEA ablation for VT in the context of cardiac sarcoidosis and extensive scar in the antero-lateral LV wall. Given the prior 2 ablation failures, epicardial, AIV, and endocardial mapping was performed upfront, demonstrating a large low-voltage area just lateral to the AIV (Figure 4AB). Endocardial ablation leading to non-capture was achieved first, without impacting VT. Venograms demonstrated a diagonal branch of the AIV in the region of the scar. Diagonal vein cannulation with an octapolar catheter confirmed the location of the diagonal vein in the scar tissue after integration with the electroanatomical map (Figure 4CDE). Signals from the diagonal vein showed mid-diastolic electrograms, and concealed entrainment with post-pacing interval close to the VT cycle length. A double-balloon approach was used to sequentially deliver VEA along the diagonal vein, which led to increased intramural echogenicity in the targeted areas (Figure 4I–L), as well as non-inducibility of VT.

Figure 4.

Double-balloon VEA in a patient with VT from cardiac sarcoidosis and prior RFA failure. A, VT morphology. B, Endocardial, epicardial and anterior interventricular vein (AIV) voltage maps showing a large anterior scar. Activation maps (right) shows earliest activation at basal anterior wall, latest in the proximal AIV, and no apparent reentrant circuit. C-D, Venogram showing a large diagonal vein, cannulated with octapolar catheter. E, location of the octapolar catheter in diagonal vein relative to the endocardial and epicardial scar. F, mid-diastolic diagonal vein signals precede those in the AIV. G, Concealed entrainment from diagonal vein shows post-pacing interval and stimulus-QRS consistent with location within reentrant circuit. H, schematic of double-balloon VEA in diagonal vein. I-K, sequential double balloon VEA. L-M, increased echogenicity in targeted region after VEA.

Figure 5 shows VEA in a patient with idiopathic nonischemic cardiomyopathy and a predominantly epicardial substrate. Epicardial mapping showed an extensive area of low voltage along the lateral wall, while endocardial mapping showed a small lateral low-voltage area. (Figure 5CD). A large lateral vein was found traversing the epicardial scar. Epicardial electrograms demonstrated late potentials, as did electrograms from the lateral vein. Pacing from the lateral vein captured with a long latency and reproduced the VT morphology (Figure 5EF). A double-balloon strategy was employed, delivering VEA along the lateral vein (Figure 5G–J). Repeat epicardial mapping demonstrated elimination of the epicardial substrate. ICE showed new areas of increased echogenicity in the targeted region. There was no VT inducibility after VEA.

Figure 5.

Double-balloon VEA in a lateral vein in idiopathic cardiomyopathy and prior RFA failure. A-B, venogram and octapolar vein cannulation of a large lateral vein. Epicardial mapping had been performed with PentaRay catheter. C-D, voltage maps of epicardial and endocardial surfaces showing disproportionately large epicardial scar, with location of octapolar catheter in lateral vein superimposed. E, epicardial (Penta) and vein signals from the scar, showing late potentials. Pacing from lateral vein leads to long latency and QRS morphology matching VT (F). G-J, sequential double-balloon VEA along lateral vein. K-L, and M-N, Pre- and post-VEA epicardial voltage maps showing marked voltage reduction (note scale of 0 to 1.5 mV). O-P, increased echogenicity in targeted region after VEA.

Online Figure 2 shows VEA approach in a patient with VT arising from a posterobasal scar, later found to be due to Chagas disease.

Online Figure 3 shows an example of VEA delivered in a distal diagonal vein (in an antegrade flow direction) while the AIV was blocked. The distal balloon had been placed in a diagonal vein via lateral vein-to-diagonal vein collaterals. Ethanol was delivered in the direction of venous flow while the AIV balloon blocked it, restricting ethanol to the underlying myocardium.

Thus, a complete spectrum of LV nonischemic VT substrates was treated with VEA approaches.

Venous ablation: effect on vein signals and post-VEA scar on LGE-CMR

Vein signals post VEA were obtainable in 23/41 patients. In the remainder, no repeat cannulation of the targeted vein was performed. In all 23 patients, repeat mapping showed electrogram attenuation of near-field electrograms (online Figure 4).

Twenty-two patients had LGE-CMR imaging performed before and after VEA (in 15 patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy and in 7 patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy). In 12 patients, two post-VEA LGE-CMR scans were performed, allowing to demonstrate the progression of VEA-induced scar. In early (within 48h post-VEA), areas of microvascular occlusion (MVO) were demonstrated as dark areas on LGE-CMR, with variable transformation into scar on follow-up scans. Figure 6 shows examples of LGE-CMR before and after VEA.

Figure 6.

Scar progression after VEA by LGE-CMR. In 1-day post-VEA scans, areas of hypoenhancement (red arrows) consistent with microvascular obstruction are seen. These are variably replaced by scar (yellow arrows) on long-term scans. A, ischemic VT substrate, B, nonsischemic VT substrate.

Outcomes

There were no intraprocedural complications attributable to VEA. Three patients developed post-procedure inflammatory pericardial effusions (at 10, 35 and 47 days post-VEA), requiring drainage. All three patients had had concomitant pericardial access and instrumentation.

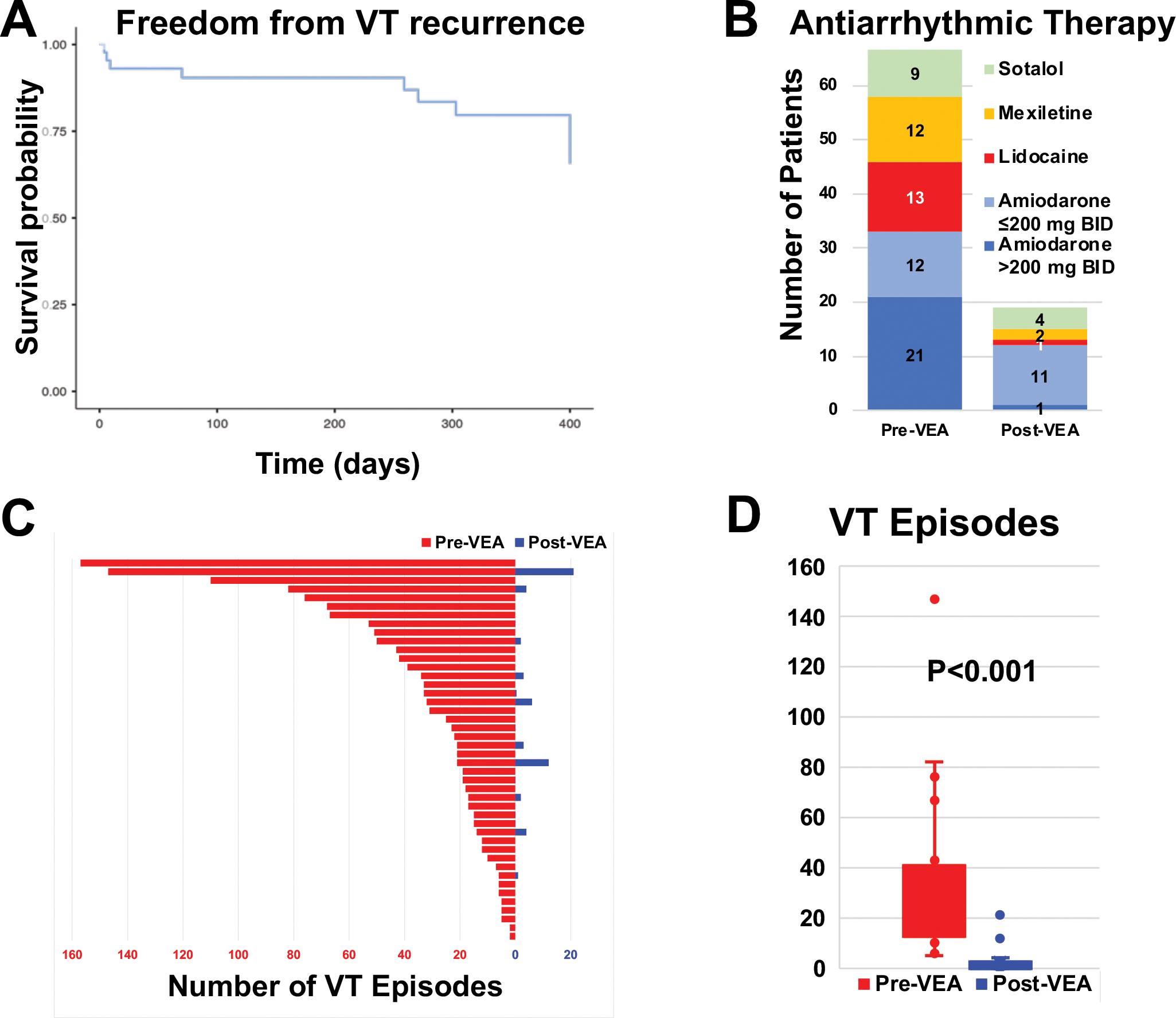

At one year of follow-up -median of 314 (IQR 198–453) days- of follow-up, VT recurrence occurred in 7 patients, for a success of 84.1%, all while on antiarrhythmic therapy. There were 20 patients with follow-up exceeding 1 year, and there were 3 additional recurrences -in the absence of antiarrhythmic therapy- beyond 1 year (at 399, 405 and 1029 days), for a total long-term success rate of 77.3%. Figure 7 shows a Kaplan-Meier plot of freedom from VT at one year of follow-up.

Figure 7.

Outcomes after VEA. A, Kaplan-Meier plot of freedom from VT. Recurrences after 1 year were truncated at 400 days. B, antiarrhythmic drug therapy distribution before and after VEA. C, VT episodes before and after VEA in all 44 patients. D, box plot of VT episodes before and after VE.

The VT substrate underlying etiology did not seem to impact recurrences. For ischemic VT, there were 4/21 recurrences, compared with 6/23 in the nonischemic patients (P=0.578).

Besides the presence or absence of recurrence, VEA had an important impact in patient management. A substantial reduction in antiarrhythmic therapy requirements was achieved. Additionally, even for failed cases, an important reduction of VT episodes was recorded on follow-up. Figure 7 shows the total number of VT episodes recorded, and a bar graph of antiarrhythmic therapies, both counting 3 months and after the VEA procedure. Of the recurrent cases, one underwent surgical cryoablation, two underwent repeat ablation -one repeat epicardial, one endocardial- and 7 were controlled with antiarrhythmic drugs.

Discussion

The key findings of this study are that: 1) VEA is associated with reduced VT burden in RFA-refractory VT arising from a broad range of substrates (ischemic and non-ischemic) and of locations within the LV; 2) intraprocedural substrate ablation by VEA exceeds that afforded by conventional ablation; 3) multi-vein, multi-balloon strategies may be required for complete ablation in complex substrates; 4) MVO is a mechanism of VEA effect, which is variably replaced by long-term scar.

In the Thermocool VT ablation study,28 RFA abolished all inducible VT in only 49% of patients with post-infarction VT. Depending on the underlying heart disease, ablation success can be as low as 56% in nonischemic cardiomyopathy, vs 60% in ischemic cardiomyopathy,29 and 79% in the absence of structural heart disease, with even lower long-term success rates.30 Most ablation failures are due to inability to reach intramural VT substrates.14, 31 Importantly, patients that have VT recurrence after ablation have dramatically increased mortality.32

Novel approaches have been proposed to treat RFA-refractory VT, including simultaneous unipolar33, 34 or bipolar ablation35, 36 from both sides of the intramural substrate, half-normal saline irrigation,37, 38 needle ablation (discontinued by the manufacturer),39 or surgical cryoablation.40 Recently, stereotactic radiation41, 42 has shown great promise, but long-term results have not been uniformly reproduced.43 None of these offer the low cost, technical availability, simplicity, and rapid ablative efficacy of VEA.

VEA capitalizes on the direct tissue reach provided by coronary veins. Our initial approach necessarily includes endocardial substrate mapping and demonstration that anatomically, there is an epicardial vein overlying that substrate. In ischemic VT, the VT circuit arises as a consequence of a prior myocardial infarction caused by atherothrombotic occlusion of an infarct-related artery. Myocardial scar and fibrosis leads to disrupted electrical propagation, and areas of unexcitable myocardium, which set the stage for reentrant circuits. Ventricular arteries co-localize with veins as a result of a common vasculogenic embryologic process,44 which leads to the fact that infarct-related arteries have a neighboring vein, an infarct-related vein. Thus, all patients with ischemic VT had at least one large epicardial vein over the VT substrate. For nonischemic VT substrates, the colocalization of the substrate with an epicardial vein is not linked to a specific anatomical or mechanistic connection, but we similarly found epicardial veins in all cases.

VEA can be particularly suited for certain VT substrates. Basal LV substrates can be particularly challenging to ablate. Endocardial catheter reach under the mitral valve can be technically difficult, and epicardial ablation may be hampered by basal epicardial fat and proximity to coronary arteries. Our case of Chagas VT (Online Figure 2) illustrates how VEA can circumvent these difficulties.

The venous anatomy can be both an opportunity and a challenge. Delivering 2 balloons to coronary veins for the double-balloon approach can be impossible, particularly in distal veins. However, vein-to-vein collateral flow can offer an opportunity as shown in Online Figure 3.

The integration of 3D mapping with venography data is vital to the identification of suitable veins in the VT substrate. In most cases, incorporating the vein location to the 3D map was possible by introducing multipolar catheters in the veins, and creating a separate, independent “vein geometry”. Miniaturized multipolar catheters were also crucial to record signals from smaller veins.

The integration of ICE with the 3D maps clearly demonstrates that the VEA-targeted areas correspond to intramural regions adjacent to the earliest sites on activation maps.

The extent of myocardial reach by VEA had not been clearly established. Intraprocedurally, ICE demonstrated clear increases in echogenicity that matched the targeted areas by VEA. CMR has been the imaging modality of choice to assess both scar as well as ablation lesions.12 The area of myocardial hypoenhancement seen on LGE-CMR early after ethanol infusion is consistent with retrograde (venous) reach to myocardial tissue. Additionally, in the selected patients that had follow up LGE-CMR, a progression from MVO to scar was seen that confirms the ablative effect long-term.

VEA remains a complex procedure that was associated with relatively prolonged procedure times, fluoroscopy and contrast use. Although these were comparable or lower than those reported using RFA in the Thermocool VT study,28 they do reflect added procedural complexity. Although cannulation of the CS is considered routine in most ablation procedures, the added instrumentation associated with venous mapping and VEA requires additional skills, and procedure time and complexity.

Future Directions:

Our results need to be validated in a larger, randomized study to establish the role and optimal timing of VEA in VT ablation. However, given that patients enrolled included RFA-refractory VT, our data support an added benefit, and form the basis for the randomized VELVET trial (NCT05511246). Although the ablative effects of ethanol are well established,45 our delivery approach needs to be replicated. Limitations in the equipment (not designed for ablation), the technical arduousness of the procedure, and the complex integration of venous anatomy with 3D substrate maps all seem amenable to improvement in order to make our results reliably reproducible.

Study Limitations:

Strategies to maximize RFA efficacy such as prolonged ablation lesions46, 47 were not used. One operator (MV) supervised or performed all procedures in the two institutions, thus reproducibility may be limited. Although epicardial access was used when possible and appropriate, we did not aim to compare VEA with epicardial ablation systematically. Our intent was to validate VEA after failed RFA, including epicardial RFA when feasible and indicated. VEA requires added technical expertise that may limit its reproducibility.

Conclusion:

Multi-balloon, multi-vein intramural ablation by VEA can provide effective substrate ablation in patients with RFA-refractory VT in the setting of structural heart disease over a broad range of LV locations.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

What is new?

The left ventricular venous circulation allows vascular access to reach intramural substrates of ventricular tachycardia in the context of myocardial infarction or nonischemic scar, where radiofrequency ablation has limited success.

Techniques for multi-balloon, multi-vein intramural ablation by venous ethanol are described.

Venous ethanol can provide effective substrate ablation in patients with ablation-refractory ventricular tachycardia in the setting of structural heart disease over a broad range of LV locations.

What are the clinical implications?

Ablation-refractory patients can benefit from venous ethanol ablation of the ventricular substrate.

Incorporation of venous ethanol into routine management of ventricular tachycardia will require larger studies and technique reproducibility.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Adelina Ramirez for her mapping support and Jesús Almendral, MD for reviewing the manuscript.

Funding sources:

Supported by the Charles Burnett III and Lois and Carl Davis Centennial Chair endowments (Houston, Texas, USA) and NIH/NHLBI R01 HL115003 (MV).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CS

coronary sinus

- ICE

intracardiac echocardiography

- ICD

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

- LGR-CMR

late-gadolinium enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance

- LV

left ventricle

- MVO

microvascular occlusion

- RFA

radiofrequency ablation

- VT

Ventricular tachycardia

- VEA

venous ethanol ablation

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Disclosures

MV receives research support from Biosense-Webster and CIRCA Scientific, and consulting fees from Baylis Medical, Biosense-Webster, Abbott, and Boston Scientific.

Supplemental material;

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, Deal BJ, Dickfeld T, Field ME, Fonarow GC, Gillis AM, Granger CB, Hammill SC, Hlatky MA, Joglar JA, Kay GN, Matlock DD, Myerburg RJ and Page RL. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: Executive summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:e190–e252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arenal A, Avila P, Jimenez-Candil J, Tercedor L, Calvo D, Arribas F, Fernandez-Portales J, Merino JL, Hernandez-Madrid A, Fernandez-Aviles FJ and Berruezo A. Substrate Ablation vs Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy for Symptomatic Ventricular Tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:1441–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tung R, Xue Y, Chen M, Jiang C, Shatz DY, Besser S, Hu H, Chung FP, Nakahara S, Kim YH, Satomi K, Shen L, Liang E, Liao H, Gu K, Jiang R, Jiang J, Hori Y, Choi JI, Ueda A, Komatsu Y, Kazawa S, Soejima K, Chen SA, Nogami A, Yao Y and Investigators P-S. First-Line Catheter Ablation of Monomorphic Ventricular Tachycardia in Cardiomyopathy Concurrent with Defibrillator Implantation: The PAUSE-SCD Randomized Trial. Circulation. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Della Bella P, Baratto F, Vergara P, Bertocchi P, Santamaria M, Notarstefano P, Calo L, Orsida D, Tomasi L, Piacenti M, Sangiorgio S, Pentimalli F, Pruvot E, de Sousa J, Sacher F, Tritto M, Rebellato L, Deneke T, Romano SA, Nesti M, Gargaro A, Giacopelli D, Peretto G and Radinovic A. Does Timing of Ventricular Tachycardia Ablation Affect Prognosis in Patients With an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator? Results From the Multicenter Randomized PARTITA Trial. Circulation. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar S, Tedrow UB and Stevenson WG. Adjunctive Interventional Techniques When Percutaneous Catheter Ablation for Drug Refractory Ventricular Arrhythmias Fail: A Contemporary Review. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10:e003676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakahara S, Tung R, Ramirez RJ, Michowitz Y, Vaseghi M, Buch E, Gima J, Wiener I, Mahajan A, Boyle NG and Shivkumar K. Characterization of the arrhythmogenic substrate in ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy implications for catheter ablation of hemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2355–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vergara P, Trevisi N, Ricco A, Petracca F, Baratto F, Cireddu M, Bisceglia C, Maccabelli G and Della Bella P. Late potentials abolition as an additional technique for reduction of arrhythmia recurrence in scar related ventricular tachycardia ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23:621–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Biase L, Santangeli P, Burkhardt DJ, Bai R, Mohanty P, Carbucicchio C, Dello Russo A, Casella M, Mohanty S, Pump A, Hongo R, Beheiry S, Pelargonio G, Santarelli P, Zucchetti M, Horton R, Sanchez JE, Elayi CS, Lakkireddy D, Tondo C and Natale A. Endo-epicardial homogenization of the scar versus limited substrate ablation for the treatment of electrical storms in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:132–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tung R, Michowitz Y, Yu R, Mathuria N, Vaseghi M, Buch E, Bradfield J, Fujimura O, Gima J, Discepolo W, Mandapati R and Shivkumar K. Epicardial ablation of ventricular tachycardia: an institutional experience of safety and efficacy. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:490–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izquierdo M, Sanchez-Gomez JM, Ferrero de Loma-Osorio A, Martinez A, Bellver A, Pelaez A, Nunez J, Nunez C, Chorro J and Ruiz-Granell R. Endo-epicardial versus only-endocardial ablation as a first line strategy for the treatment of ventricular tachycardia in patients with ischemic heart disease. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:882–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acosta J, Fernandez-Armenta J, Penela D, Andreu D, Borras R, Vassanelli F, Korshunov V, Perea RJ, de Caralt TM, Ortiz JT, Fita G, Sitges M, Brugada J, Mont L and Berruezo A. Infarct transmurality as a criterion for first-line endo-epicardial substrate-guided ventricular tachycardia ablation in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romero J, Cerrud-Rodriguez RC, Di Biase L, Diaz JC, Alviz I, Grupposo V, Cerna L, Avendano R, Tedrow U, Natale A, Tung R and Kumar S. Combined Endocardial-Epicardial Versus Endocardial Catheter Ablation Alone for Ventricular Tachycardia in Structural Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2019;5:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldinger SH, Kumar S, Barbhaiya CR, Mahida S, Epstein LM, Michaud GF, John R, Tedrow UB and Stevenson WG. Epicardial Radiofrequency Ablation Failure During Ablation Procedures for Ventricular Arrhythmias: Reasons and Implications for Outcomes. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:1422–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar S, Barbhaiya CR, Sobieszczyk P, Eisenhauer AC, Couper GS, Nagashima K, Mahida S, Baldinger SH, Choi EK, Epstein LM, Koplan BA, John RM, Michaud GF, Stevenson WG and Tedrow UB. Role of alternative interventional procedures when endo- and epicardial catheter ablation attempts for ventricular arrhythmias fail. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:606–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baher A, Shah DJ and Valderrabano M. Coronary venous ethanol infusion for the treatment of refractory ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1637–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreidieh B, Rodriguez-Manero M, P AS, Ibarra-Cortez SH, Dave AS and Valderrabano M. Retrograde Coronary Venous Ethanol Infusion for Ablation of Refractory Ventricular Tachycardia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016;9: 10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004352 e004352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tavares L and Valderrabano M. Retrograde venous ethanol ablation for ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:478–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tavares L, Lador A, Fuentes S, Da-wariboko A, Blaszyk K, Malazynska-Rajpold K, Papiashvili G, Korolev S, Peich P, Kautzner J, Webber M, Hooks D, Rodríguez-Mañero M, Di Toro D, Labadet C, Sasaki T, Okishige K, Patel A, Schurmann PA, Dave AS, Rami TG and Valderrábano M. Intramural Venous Ethanol Infusion for Refractory Ventricular Arrhythmias. Outcomes of a Multicenter Experience. J Am Coll Cardiol EP. 2020: 10.1016/j.jacep.2020.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Da-Wariboko A, Lador A, Tavares L, Dave AS, Schurmann PA, Peichl P, Kautzner J, Papiashvili G and Valderrabano M. Double-balloon technique for retrograde venous ethanol ablation of ventricular arrhythmias in the absence of suitable intramural veins. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17:2126–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchlinski FE, Callans DJ, Gottlieb CD and Zado E. Linear ablation lesions for control of unmappable ventricular tachycardia in patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2000;101:1288–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arenal A, Glez-Torrecilla E, Ortiz M, Villacastin J, Fdez-Portales J, Sousa E, del Castillo S, Perez de Isla L, Jimenez J and Almendral J. Ablation of electrograms with an isolated, delayed component as treatment of unmappable monomorphic ventricular tachycardias in patients with structural heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berruezo A, Fernandez-Armenta J, Andreu D, Penela D, Herczku C, Evertz R, Cipolletta L, Acosta J, Borras R, Arbelo E, Tolosana JM, Brugada J and Mont L. Scar dechanneling: new method for scar-related left ventricular tachycardia substrate ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:326–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tzou WS, Frankel DS, Hegeman T, Supple GE, Garcia FC, Santangeli P, Katz DF, Sauer WH and Marchlinski FE. Core isolation of critical arrhythmia elements for treatment of multiple scar-based ventricular tachycardias. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:353–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sapp JL, Wells GA, Parkash R, Stevenson WG, Blier L, Sarrazin JF, Thibault B, Rivard L, Gula L, Leong-Sit P, Essebag V, Nery PB, Tung SK, Raymond JM, Sterns LD, Veenhuyzen GD, Healey JS, Redfearn D, Roux JF and Tang AS. Ventricular Tachycardia Ablation versus Escalation of Antiarrhythmic Drugs. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:111–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevenson WG, Friedman PL, Sager PT, Saxon LA, Kocovic D, Harada T, Wiener I and Khan H. Exploring postinfarction reentrant ventricular tachycardia with entrainment mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1180–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sosa E, Scanavacca M, d’Avila A and Pilleggi F. A new technique to perform epicardial mapping in the electrophysiology laboratory. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1996;7:531–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Da-Wariboko A, Lador A, Tavares L, Dave AS, Schurmann PA, Peichl P, Kautzner J, Papiashvili G and Valderrabano M. Double-balloon technique for retrograde venous ethanol ablation of ventricular arrhythmias in the absence of suitable intramural veins. Heart Rhythm. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevenson WG, Wilber DJ, Natale A, Jackman WM, Marchlinski FE, Talbert T, Gonzalez MD, Worley SJ, Daoud EG, Hwang C, Schuger C, Bump TE, Jazayeri M, Tomassoni GF, Kopelman HA, Soejima K and Nakagawa H. Irrigated radiofrequency catheter ablation guided by electroanatomic mapping for recurrent ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction: the multicenter thermocool ventricular tachycardia ablation trial. Circulation. 2008;118:2773–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchlinski FE, Haffajee CI, Beshai JF, Dickfeld TL, Gonzalez MD, Hsia HH, Schuger CD, Beckman KJ, Bogun FM, Pollak SJ and Bhandari AK. Long-Term Success of Irrigated Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation of Sustained Ventricular Tachycardia: Post-Approval THERMOCOOL VT Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:674–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar S, Romero J, Mehta NK, Fujii A, Kapur S, Baldinger SH, Barbhaiya CR, Koplan BA, John RM, Epstein LM, Michaud GF, Tedrow UB and Stevenson WG. Long-term outcomes after catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in patients with and without structural heart disease. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:1957–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tokuda M, Kojodjojo P, Tung S, Tedrow UB, Nof E, Inada K, Koplan BA, Michaud GF, John RM, Epstein LM and Stevenson WG. Acute failure of catheter ablation for ventricular tachycardia due to structural heart disease: causes and significance. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tung R, Vaseghi M, Frankel DS, Vergara P, Di Biase L, Nagashima K, Yu R, Vangala S, Tseng CH, Choi EK, Khurshid S, Patel M, Mathuria N, Nakahara S, Tzou WS, Sauer WH, Vakil K, Tedrow U, Burkhardt JD, Tholakanahalli VN, Saliaris A, Dickfeld T, Weiss JP, Bunch TJ, Reddy M, Kanmanthareddy A, Callans DJ, Lakkireddy D, Natale A, Marchlinski F, Stevenson WG, Della Bella P and Shivkumar K. Freedom from recurrent ventricular tachycardia after catheter ablation is associated with improved survival in patients with structural heart disease: An International VT Ablation Center Collaborative Group study. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1997–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamada T, Maddox WR, McElderry HT, Doppalapudi H, Plumb VJ and Kay GN. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias originating from intramural foci in the left ventricular outflow tract: efficacy of sequential versus simultaneous unipolar catheter ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:344–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J, Liang J, Shirai Y, Muser D, Garcia FC, Callans DJ, Marchlinski FE and Santangeli P. Outcomes of simultaneous unipolar radiofrequency catheter ablation for intramural septal ventricular tachycardia in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:863–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen DT, Tzou WS, Brunnquell M, Zipse M, Schuller JL, Zheng L, Aleong RA and Sauer WH. Clinical and biophysical evaluation of variable bipolar configurations during radiofrequency ablation for treatment of ventricular arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:2161–2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Futyma P, Santangeli P, Purerfellner H, Pothineni NV, Gluszczyk R, Ciapala K, Moroka K, Martinek M, Futyma M, Marchlinski FE and Kulakowski P. Anatomic approach with bipolar ablation between the left pulmonic cusp and left ventricular outflow tract for left ventricular summit arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2020:S1547–5271(20)30360-X. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen DT, Olson M, Zheng L, Barham W, Moss JD and Sauer WH. Effect of Irrigant Characteristics on Lesion Formation After Radiofrequency Energy Delivery Using Ablation Catheters with Actively Cooled Tips. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015;26:792–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen DT, Tzou WS, Sandhu A, Gianni C, Anter E, Tung R, Valderrabano M, Hranitzky P, Soeijma K, Saenz L, Garcia FC, Tedrow UB, Miller JM, Gerstenfeld EP, Burkhardt JD, Natale A and Sauer WH. Prospective Multicenter Experience With Cooled Radiofrequency Ablation Using High Impedance Irrigant to Target Deep Myocardial Substrate Refractory to Standard Ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;4:1176–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevenson WG, Tedrow UB, Reddy V, AbdelWahab A, Dukkipati S, John RM, Fujii A, Schaeffer B, Tanigawa S, Elsokkari I, Koruth J, Nakamura T, Naniwadekar A, Ghidoli D, Pellegrini C and Sapp JL. Infusion Needle Radiofrequency Ablation for Treatment of Refractory Ventricular Arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1413–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi EK, Nagashima K, Lin KY, Kumar S, Barbhaiya CR, Baldinger SH, Reichlin T, Michaud GF, Couper GS, Stevenson WG and John RM. Surgical cryoablation for ventricular tachyarrhythmia arising from the left ventricular outflow tract region. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1128–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cuculich PS, Schill MR, Kashani R, Mutic S, Lang A, Cooper D, Faddis M, Gleva M, Noheria A, Smith TW, Hallahan D, Rudy Y and Robinson CG. Noninvasive Cardiac Radiation for Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2325–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson CG, Samson PP, Moore KMS, Hugo GD, Knutson N, Mutic S, Goddu SM, Lang A, Cooper DH, Faddis M, Noheria A, Smith TW, Woodard PK, Gropler RJ, Hallahan DE, Rudy Y and Cuculich PS. Phase I/II Trial of Electrophysiology-Guided Noninvasive Cardiac Radioablation for Ventricular Tachycardia. Circulation. 2019;139:313–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gianni C, Rivera D, Burkhardt JD, Pollard B, Gardner E, Maguire P, Zei PC, Natale A and Al-Ahmad A. Stereotactic arrhythmia radioablation for refractory scar-related ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17:1241–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernanke DH and Velkey JM. Development of the coronary blood supply: changing concepts and current ideas. Anat Rec. 2002;269:198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brugada P, de Swart H, Smeets JL and Wellens HJ. Transcoronary chemical ablation of ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1989;79:475–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muser D, Santangeli P, Castro SA, Pathak RK, Liang JJ, Hayashi T, Magnani S, Garcia FC, Hutchinson MD, Supple GG, Frankel DS, Riley MP, Lin D, Schaller RD, Dixit S, Zado ES, Callans DJ and Marchlinski FE. Long-Term Outcome After Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia in Patients With Nonischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016;9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muser D, Santangeli P, Castro SA, Liang JJ, Enriquez A, Liuba I, Magnani S, Garcia FC, Arkles J, Supple GG, Lin D, Schaller RD, Kumareswaran R, Zado E, Tschabrunn CM, Dixit S, Frankel DS, Callans DJ and Marchlinski FE. Collateral injury of the conduction system during catheter ablation of septal substrate in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020;31:1726–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.