Abstract

Acceptability judgments are a primary source of evidence in formal linguistic research. Within the generative linguistic tradition, these judgments are attributed to evaluation of novel forms based on implicit knowledge of rules or constraints governing well-formedness. In the domain of phonological acceptability judgments, other factors including ease of articulation and similarity to known forms have been hypothesized to influence evaluation. We used data-driven neural techniques to identify the relative contributions of these factors. Granger causality analysis of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-constrained magnetoencephalography (MEG) and electroencephalography (EEG) data revealed patterns of interaction between brain regions that support explicit judgments of the phonological acceptability of spoken nonwords. Comparisons of data obtained with nonwords that varied in terms of onset consonant cluster attestation and acceptability revealed different cortical regions and effective connectivity patterns associated with phonological acceptability judgments. Attested forms produced stronger influences of brain regions implicated in lexical representation and sensorimotor simulation on acoustic-phonetic regions, whereas unattested forms produced stronger influence of phonological control mechanisms on acoustic-phonetic processing. Unacceptable forms produced widespread patterns of interaction consistent with attempted search or repair. Together, these results suggest that speakers’ phonological acceptability judgments reflect lexical and sensorimotor factors.

Keywords: Acceptability judgments, Phonology/Phonotactics, Effective connectivity, MEG/EEG, Rules, Lexical effects

1. Introduction

Judgements about the acceptability of novel words or sentences are central to the development of linguistic theory. From the outset, theorists have wrestled with the challenge of interpreting the degree to which these judgments reflect knowledge of the grammar (competence) versus domain-general cognitive processes (performance) (Chomsky, 1965). While the competence-performance distinction remains controversial (Hymes, 1992; Newmeyer, 2003), understanding the processes that support these judgments is critical for understanding the implications of the observation that some constructions are more acceptable or interpretable than others. In the realm of syntactic theory, empirical research has demonstrated that some constructions including center embeddings are frequently judged unacceptable despite being considered grammatical (Chomsky & Miller, 1963), while other grammaticality illusions may be judged moderately acceptable despite being both ungrammatical and uninterpretable (Phillips et al., 2011). Indeed, systematic research (Featherston, 2007; Bader & Häussler, 2010; Gibson, Piantadosi & Fedorenko, 2011; Sprouse & Almeida, 2017) has demonstrated that sentence grammaticality judgements are influenced by a variety of factors including cognitive, social and biological differences among speakers, the response options, and the way test materials are created and presented (see Schütze, (2016) for a detailed review). Such work has enhanced research methods in theoretical linguistics and introduced new phenomena and energized new areas of research and perspectives on the interface between parsing and grammaticality.

In this paper, we examine the types of processes, representations and dynamics that specifically influence judgements of phonological acceptability used by theoretical phonologists. Phonological and syntactic acceptability judgements share some common characteristics simply by virtue of being metalinguistic judgement tasks (Schütze, 2016). Furthermore, both types of judgements may be predictable based on the relative frequency of different construction types across corpuses or lexica (Lau et al., 2017). Despite these similarities, there are many areas in which the two types of judgments are fundamentally different. First, syntactic acceptability judgements are formally taught in schools but that is not the case for phonological acceptability judgements. Thus, phonological judgements are purely implicit. Second, sentence evaluation can be influenced by several factors including semantic and pragmatic plausibility and working memory capacity that do not appear to influence phonological evaluation (Schwering & MacDonald, 2020). Third, lesion-deficit and functional imaging suggest that sentential grammaticality and phonological acceptability judgements rely on different brain regions (Bookheimer, 2002). Fourth, novel words and novel sentences present different processing challenges. Whereas novel sentences invite interpretation, novel words invite the listener to either access familiar words or acquire new ones. Next, perceptual and articulatory factors that play a critical role in speech processing and grounded theories of phonology do not appear to have the same significance in sentence processing or syntactic theory (Archangeli & Pulleyblank, 1994). Similarly, although both phonological and sentential acceptability judgements are correlated with frequency metrics, differences in the combinatoric complexity of words versus sentences are significant enough to require different learning mechanisms for phonological versus syntactic constraints (Heinz & Idsardi, 2011; 2013).

Chomsky and Halle (1965) made acceptability judgments a cornerstone of generative phonology when they noted that acceptability judgments extend beyond the patterns of attestation or occurrence in a given language. They argue that while the intuition that blik would be an acceptable English word, but bnik would not, might be attributable to memorization or analogy with overlapping forms (e.g., blink), the intuition that bnik is more acceptable than the equally unattested form lbik requires a different kind of explanation. These observations have been followed by a broad literature affirming that acceptability judgments are gradient, apply systematically to unattested forms, and are generally reliable across speakers of a language (e.g., Albright, 2009; Berent et al., 2007; Coetzee, 2008, 2009; Goldrick, 2011; Greenberg & Jenkins, 1964; Hayes, 2000; Kawahara & Kao, 2012; Pertz & Bever, 1975; Pierrehumbert, 2002; Scholes, 1966; Shademan, 2007; Zuraw, 2000). The generative phonological theories (Halle, 1962, 1964; Chomsky & Halle, 1965, 1968; Kenstowicz, 1994; Goldsmith & Laks, 2010) that have followed these observations are premised on the notion that productive generalization of structural constraints is the central phenomenon to be explained by any linguistic theory.

Three main competing accounts have been proposed to explain the mechanisms and theoretical significance of generalization beyond language users’ training sets. Rule/constraint-based (Chomsky and Halle, 1968; Smolensky and Prince, 1993) accounts argue that acceptability judgments reflect implicit knowledge of rules or constraints governing the formation of acceptable forms (while formal phonological theory comes in a lot of flavors, there is an agreement that phonology should be represented in some kind of abstract non articulatory, perceptual or lexical form). In contrast, associative accounts (Bybee, 2008; Evans & Levinson, 2009) attribute generalization to interactive associative mapping processes involving the lexicon. Articulatory accounts (Liberman et al., 1967; MacNeilage, 2008; Pulvermüller & Fadiga, 2010) assert that generalization is constrained by articulatory/motor considerations. The purpose of this paper is to better understand phonological generativity by determining the degree to which these accounts contribute, either individually or in combination, to phonological acceptability judgements. Specifically, we use task-related effective connectivity analyses of brain activity to identify the degree to which phonological intuitions are shaped by rules or constraints, lexical analogy, or perceived articulatory naturalness.

1.1. Rule/constraint-based, Associative, and Articulatory Accounts of Phonological Acceptability

1.1.1. Rule/constraint-based account

Rule or constraint-based accounts of linguistic generativity suggest that all language processing references abstract rules or constraints in some form, and that explicit acceptability judgments offer a relatively direct window on their application. Generative linguistic frameworks including classical transformational phonology (SPE) (Chomsky & Halle, 1968) and Optimality Theory (Smolensky & Prince, 1993) provide comprehensive accounts of structural regularity in patterns of attestation and native listeners’ phonological acceptability judgments both within and across natural languages based on the application of abstract structural rules or constraints. Evidence from artificial grammar learning experiments showing that listeners are able to learn constraints on phonological patterning through exposure to novel stimuli and apply them to explicit acceptability judgments suggests that rule-based mechanisms are psychologically plausible (see Moreton and Pater, 2012a,b for a review). Critically, generative theories assume that constraints are abstracted from the lexicon, which in turn may be shaped to some degree by efficiency pressures that mitigate for increased lexical similarity (Mahowald et al., 2018) and simplified articulation (Kawasaki & Ohala, 1980). This association between structural regularities and judgments poses potential challenges for distinguishing between the factors that shape online phonological acceptability judgements and the factors that shape generative constraints on representation.

Generative theories of cophonology suggest that rules governing the phonological realization of morphologically complex words are limited to sub-vocabularies within a language (Inkelas, 2014). Similarly, grounded theories of phonology suggest that phonological rules and the phonetic implementation of phonetic cues within a language are constrained by the need to simplify articulation and enhance perceptual contrast (Wilson, 2006; Hayes and White, 2013). Evidence from simulation studies (Reali and Griffiths, 2009) that even subtle online processing biases may produce strong cumulative pressure towards phonological normalization through iterative learning, suggests a link between online lexical influences (at least for morphologically complex words) and articulatory influences and diachronic changes in phonological structure. In this way, online articulatory demands may shape rule systems. In other words, isolating the influence of articulatory ease from the influence of rules is difficult because articulatory ease also shapes what rules the language uses. Therefore, to establish that articulatory or lexical factors independently shape acceptability judgements, it is necessary to show that these factors are operative in the absence of rule-driven mechanisms.

Disentangling these accounts based on neural evidence is further complicated by a lack of consensus on where rule or constraint-driven processing occurs in the brain. Neural data, mostly from functional MRI (fMRI) blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) imaging studies, have implicated the left inferior frontal gyrus (LIFG) in the learning and use of abstract rules related to perceptual categorization, motor sequence learning and language-like (grammatical) processing involving structured sequence processing (Strange et. al., 2001; Opitz & Friederici, 2003; Musso et al., 2003; Lieberman et al., 2004; Fitch & Friederici, 2012; Uddén & Bahlman, 2012). It is not clear what role LIFG has in these phenomena. The LIFG consists of three cytoarchitectonically and functionally distinct structures: pars opercularis (BA44), pars triangularis (BA45) and pars orbitalis (BA47) (Hagoort, 2005; Lemaire et al., 2013; Bernal et al., 2015; Ardila, Bernal and Rosselli, 2017). For example, pars opercularis has motor and phonetic functions (Amunts et al., 2004; Heim et al., 2005,2009), pars triangularis has been implicated in language-specific working memory system, retrieval/attention operations (Hagoort, 2005; Thompson-Schill, Bedny & Goldberg, 2005; Grodzinsky & Amunts, 2006; Matchin, 2018), and pars orbitalis (BA 47) is similarly implicated in semantic retrieval and control (Conner et al. 2019; Becker et al. 2020; Jackson, 2020). These findings raise the possibility that LIFG involvement in artificial grammar learning reflects the retrieval and maintenance of linguistic information rather than implicit knowledge of phonological rules or constraints.

1.1.2. Associative account

The associative account (Bybee, 2008; Evans & Levinson, 2009), inspired by connectionist simulation results (McClelland & Elman, 1986), attributes generalization to interactive associative mapping processes involving the lexicon with no reference to learned or biologically conditioned rules or constraints. It has been suggested that phonotactic intuitions and repair reflect an active role of lexical knowledge on language processing (Greenberg & Jenkins, 1964; Ohala & Ohala, 1986; Frisch et al., 2000; Bailey & Hahn, 2001; Gow & Nied, 2014; Gow et al., 2021). This approach suggests that lexical influences contribute to the perceived well-formedness of novel forms. According to this account, a comparison is made between a given nonword and the existing words in the lexicon, and the acceptability judgment is shaped by how close the nonword is to an existing word or sometimes a “gang” of existing words with overlapping phonological structure (McClelland, 1991). Using data from the area of morphological productivity and alternations with various experimental methodologies, it has been shown that the decisions to accept nonwords are shaped by the number of similar existing words in the lexicon (Albright & Hayes, 2003; Anshen & Aronoff, 1988; Bauer, 2001; Berko, 1958; Bybee 1985, 1995, 2001; Bybee & Pardo 1981; Eddington, 1996; Ernestus & Baayen, 2003; Pierrehumbert, 2002; Plag 1999; Zuraw, 2000). Measures of phonological patterning across the lexicon, including neighborhood density (the number of familiar words that are created by adding, deleting, or substituting a single sound in a given word) and biphone probabilities (the relative frequency of co-occurrence of segments within words), have been shown to have direct influence phonological acceptability judgments (Greenberg & Jenkins, 1964; Luce & Pisoni, 1998; Vitevitch & Luce, 1998, 2004). The interpretation of potential lexical influences on phonotactic behavior is complicated by evidence for phonotactic frequency effects in which items comprised of common phonological sequences enjoy processing advantages over items with less common elements (Pitt & Samuel, 1995). Studies using same-different, typicality, and word-likeness judgments show that these effects are separable from global word likeness effects such as lexical neighborhood size (Luce & Large, 2001; Bailey & Hahn, 2001; Treiman et al., 2000; Shademan, 2007). The early connectionist TRACE model (McClelland & Elman, 1986) provides an explicit demonstration of how the lexicon might influence phonotactic processing through interactive processing. When presented with a nonword with an onset cluster that is ambiguous between an acceptable form (/sl-/) and an unacceptable form (/sr-/) top-down lexical influences from words that share the acceptable form (e.g., sled, slip) give a boost to the acceptable interpretation of the form. This produces patterns of phonotactic repair that broadly parallel human behavioral results (Massaro & Cohen, 1983; Pitt, 1998) without a role for the abstraction of rules or constraints associated with this model. At the extreme end of this lexical account, Bybee (2001) denied the existence of grammar altogether and attributed acceptability judgments entirely to accessibility determined by usage statistics.

Lexical knowledge, particularly word representation, has been associated with SMG and adjacent inferior parietal regions and the bilateral posterior middle temporal gyrus (pMTG) (Hickok & Poeppel, 2007). The dual lexicon model (Gow, 2012) argues that the left supramarginal gyrus (SMG) acts as a lexical interface between acoustic-phonetic and articulatory representation, and that bilateral pMTG provide an interface between acoustic-phonetic and semantic/syntactic representation. Several functional imaging studies supports this framework by demonstrating that activation in both regions is modulated by whole word properties including word frequency, and the phonological similarity of a word to other words (Biran & Friedmann, 2005; Prabhakaran et. al., 2006; Graves et. al., 2007; Righi et. al., 2009). This model is also supported by the findings showing that damage to these two regions leads to deficits in lexico-semantic and lexico-phonological processing (Coslett et. al., 1987; Axer et. al., 2001). The dual stream model’s (Hickok and Poeppel, 2007) lexical interface also includes inferior temporal sulcus (ITS) playing a role in linking phonological and semantic information, in addition to more anterior temporal regions correspond to the combinatorial network of language.

1.1.3. Articulatory account

The articulatory account asserts that generalization is constrained by articulatory/motor considerations. According to this account, judged acceptability is related to articulatory ease determined by appeal to sensorimotor simulation (Liberman et al., 1967; Lakoff & Johnson, 1999; Schwartz et al., 2002; Galantucci et al., 2006; MacNeilage, 2008; Pulvermüller & Fadiga, 2010). Grounded models of phonology generally recognize articulatory effort as a factor that affects phonological systems (Archangeli & Pulleyblank, 1994; Gafos, 1999; Pierrehumbert, 2002). The question is whether articulatory factors influence online acceptability judgments directly or indirectly by shaping abstract rules or constraints. Burani, Vallar, and Bottini (1991) found evidence of online articulatory suppression effects in speeded judgements of stress assignment and initial sound similarity, but it is unclear whether these effects reflect articulatory or rule mediation, or some combination of both.

Articulatory/motor representation is associated with primary sensorimotor cortex. Paulesu et al. (1993) found that ventral part of the primary sensorimotor cortex is activated during rhyme judgments with orthographic prompts in the absence of overt speech. Pulvermüller et al. (2006), in an fMRI experiment, report that listening to labial sounds (e.g., /b/) activates lip motor sites in the brain whereas listening to coronal sounds (e.g., /t/) activates tongue-related motor areas (see also Fadiga et al., 2002). The transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) literature provides converging evidence from findings showing that the stimulated tongue motor region plays a role in the perception of coronal phonemes (e.g., /t/) whereas the stimulated lip area helps perception of labial phonemes (e.g., /b/) (D’Ausilio et al., 2009, 2012; Möttönen & Watkins, 2009). Berent et al. (2015) and Zhao and Berent (2018) further investigated the articulatory motor region’s causal role in speech perception by asking whether sensitivity to phonological patterning (specifically to the syllable hierarchy, e.g., /bl/ is preferred over /bn/ which is better than /lb/) requires motor simulation or is constrained by universal rules. Participants in these experiments performed tasks including syllable counting with or without articulatory suppression and identity discrimination with printed materials or background noise, while their lip motor area underwent TMS. Participants showed sensitivity to the phonological constraints on the patterning of sonority when their motor areas were disrupted by TMS regardless of suppression. These findings suggest that articulatory influences alone do not account for sensitivity to phonological patterning; for a detailed review of these findings, see Berent et al. (2015) and Zhao and Berent (2018).

1.2. Neural correlates of phonological well-formedness

In this section, will lay out the neural network behind the phonological acceptability judgments and argue that various brain regions with very different functions respond to the well-formedness of phonological strings. In particular, we will draw inferences from two lines of work: one that has directly investigated phonological well-formedness with acceptability judgements and another that has looked at this indirectly by using tasks in which phonological or phonotactic regularities influence speech perception.

While a large empirical literature has examined the neural substrates of phonological processing (see reviews by Poeppel, 1996; Burton, 2001; Buchsbaum et al., 2011), few studies have directly investigated how perceived acceptability or well-formedness affect brain activity. The work that has been done implicates frontal and temporoparietal regions. Rossi et al. (2011) investigated the neuronal correlates of phonotactic processing in a functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) study with a passive listening task. They found that spoken nonwords with phonotactic patterns that were illegal in German yielded a greater hemodynamic response over a left-hemispheric network including fronto-temporal regions than did nonwords with legal patterns. Vaden et al. (2011) found that fMRI BOLD activation in a region including the medial pars triangularis, lateral inferior frontal sulcus, and anterior insula was correlated with phonotactic frequency during the perception of acoustically degraded words. Similarly, Berent et al. (2014) found a positive correlation between ill-formedness and activation in bilateral posterior pars triangularis (BA45), a subpart of the LIFG, in a syllable counting task in which perceptual repair of illegal consonant clusters influenced perceived syllabification.

While the studies by Rossi et al. (2011), Vaden et al. (2011) and Berent et al. (2014) implicate LIFG, and specifically pars triangularis in processing related to manipulations of phonotactic legality or acceptability, it is unclear what functional role LIFG is playing. All of them employed stimuli that varied in intelligibility, articulatory familiarity and wordlikeness in addition to acceptability, and none of them required explicit judgments of phonological acceptability. Pars triangularis activation is independently associated with attention and retrieval processes within a language-specific working memory system (Matchin, 2018) as well as subvocal rehearsal in working memory (Burton et al., 2001; Elmer, 2016; Kazui et al., 2000; Menon et al., 2000; Ranganath et al., 2003; Rickard et al., 2000). This suggests that the above results may reflect downstream, task-induced processing rather than immediate phonotactic analysis.

Evidence from tasks that directly rely on acceptability judgment implicates temporal and parietal regions, but not inferior frontal areas for phonological well-formedness effects. Ghaleh et al. (2018), using an acceptability judgment task, investigated the brain regions crucial to phonotactic knowledge with a large group of participants (44 people) with chronic left hemisphere stroke, and found no evidence of LIFG involvement. Lesion-symptom mapping analyses found that reduced sensitivity to the phonological structure was most strongly associated with damage to the left pMTG and angular gyrus (AG). They hypothesized that AG plays a role in comparing the input to the most frequent phonotactic patterns found in lexical wordform representations stored in pMTG. This finding aligns with other results relating phonotactic phenomena to pMTG and SMG, both regions previously implicated in lexical processing (Hickok & Poeppel, 2007; Gow, 2012).

In a crosslinguistic study conducted with French and Japanese speakers, Jacquemot et al. (2003) suggested that participation of the left posterior superior temporal gyrus (pSTG) and SMG in phonotactic processing reflects interaction between acoustic-phonetic and semantic representations. Similarly, Gow and Nied (2014) found an association between increased influence by SMG and pMTG on pSTG and perceptual repair of phonotactically unacceptable nonword onset consonant clusters. Gow and Olson (2015) found that this dynamic is stronger during lexical decision for words and nonwords composed of high frequency phonotactic sequences. Obrig et al. (2016) examined the interaction between electrophysiological measures and lesions in a study of auditory word repetition using phonologically acceptable, unacceptable and reversed nonwords. They found that while the contrast between reversed speech and forward speech activated SMG and AG, the contrast between legal versus illegal phonotactics implied anterior and middle portions of the middle temporal and superior temporal gyri. They concluded that speech comprehension is influenced by phonological structure at different phonologically and lexically driven steps. Collectively, the results of this literature suggest that multiple brain regions, each associated with very different functions, show sensitivity to the well-formedness of phonological strings. The goal of the present study is to characterize the relative contribution of regions across this distributed network to the performance of phonological acceptability judgments that serve as a primary driving force in the development of phonological theory.

1.3. Present research and predictions

In the present study, we examined dynamic neural processes that support phonological acceptability judgments of nonwords. We used high spatiotemporal resolution brain imaging techniques and data-driven effective connectivity analyses to determine how patterns of phonotactic attestation and phonological acceptability influence patterns of brain activity and information flow during an auditory nonword phonological acceptability judgment task. The data driven effective connectivity analyses enables us to study language as the product of a dynamic, distributed network of specialized processors rather than just local functions. In particular, our aim is to investigate the direction of processing interactions between brain regions and identify function-specific effects of phonological judgments. Phonotactic acceptability is often correlated with factors including wordlikeness and articulatory challenge, which may affect activation in brain regions associated with articulatory or lexical processing. The application of effective connectivity analysis allows us to examine how these factors affect active processes such as rehearsal, verification, or repair associated with phonological evaluation.

We created auditory CCVC nonwords divided into three conditions across the continuum of phonotactic attestation and phonological acceptability based on mean acceptability ratings derived from a pilot study. For purposes of simplicity, and to allow direct comparison with previous effective connectivity studies of phonological constraints on speech perception and word recognition, our primary analyses focused on causal influences on the left posterior superior temporal gyrus (pSTG). Evidence from electrocorticography (Mesgarini et al., 2014) and converging data from pathology and functional imaging (Yi et al., 2019) suggest that the left pSTG is primarily involved in acoustic-phonetic representation and processing (Poeppel, Idsardi & van Wassenhove, 2008). Although we do not hypothesize that phonological acceptability judgments are made in this area, as a hub region linking the dorsal and ventral spoken language processing streams (Hickok & Poeppel, 2007) pSTG provides a unique vantage point for observing the entire spoken language network. Previous results have shown that activation of pSTG is sensitive to phonotactic acceptability (Jacquemot et al., 2003), but effective connectivity analyses suggest that this sensitivity is referred from other regions as a function of phonotactic lawfulness and frequency (Gow & Nied, 2014; Gow et al., 2021; Gow & Olson, 2015). Critically, although the pSTG is influenced by regions independently associated with lexical, articulatory and rule-driven processing (Gow & Segawa, 2009; Gow & Olson, 2015), it is not uniquely associated with any of them, and so it provides an account-neutral reference point for observing dynamics associated with phonological judgement.

Each of these accounts makes different predictions about how patterns of brain activity and effective connectivity would change based on the acceptability or attestation of nonword phonotactic patterns. Under a rule-based account, all phonological structures are evaluated relative to a common set of rules after mini lexicons that contain lexical entries for valid syllable types are consulted. Our test of hypotheses of rule-based account is based on this resynthesis process where rule evaluation is utilized. Therefore, the rule account predicts that acceptability judgments would rely on dynamic processes involving a common store of phonological constraints to evaluate well-formedness. It predicts that nonwords that are judged less acceptable should evoke stronger influences from rule areas to either repair or confirm the ill-formedness of less acceptable forms. As noted above, while there is no consensus about the existence or localization of a rule store, the best candidate region is the LIFG, specifically the pars triangularis (BA 45) (Vaden et al., 2011; Berent et al., 2014). The associative account predicts attested and acceptable nonwords should evoke stronger influence on pSTG by putative word representation areas, including SMG, pMTG, and the left anterior and posterior portions of the inferior temporal lobe (Jacquemot et al., 2003; Hickok and Poeppel, 2007; Gow, 2012; Gow and Nied, 2014; Obrig et al., 2016; Ghaleh et al., 2018). The articulatory account predicts that brain regions involved in articulatory representation, including ventral pre- and post-central gyri would influence pSTG as a function of articulatory naturalness (Paulesu et al., 1993; Gow & Segawa, 2009), which might reflect a combination of attestation and acceptability, with attested and acceptable nonwords evoking weaker influences than unattested and unacceptable nonwords.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Fourteen right-handed adults participated in this study (6 males, mean age 28 years, SD = 4.3, range = 22 to 36). None of the participants reported a history of hearing loss, speech/language or motor impairments, and all were native speakers of Standard American English and self-identified as monolingual. Informed consent was obtained in compliance with the Human Subjects Review Board and all study procedures were compliant with the principles for ethical research established by the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were paid for their participation.

2.2. Stimuli

The stimuli consisted of 180 auditory CCVC nonwords recorded by an adult male speaker of Standard American English. These stimuli were a subset of 300 initial nonwords which were tested in a pilot study with 17 native speakers of Standard American English. In this pilot study, participants were given 100 nonwords with attested onset consonant clusters (e.g., smal or flike) and 200 nonwords with onset consonant clusters that do not appear in familiar non-loan English words (e.g., sras or zhnad), and were asked to rate the acceptability of these nonwords on a scale of 1 to 7. We then picked the sixty nonwords with attested onset clusters that got the highest acceptability ratings (M=4.64, SD=0.47) and assigned them to the Attested/Acceptable (AA) items. Next, we picked the sixty nonwords with unattested onset clusters that got the highest acceptability ratings (M=4.09, SD=0.64) and assigned them to the Unattested/Acceptable (UA) items. Finally, we picked the sixty nonwords with unattested onset clusters that got the lowest acceptability ratings (M=2.09, SD=0.28) and assigned them to the Unattested/Unacceptable (UU) items. Therefore, the 180 nonwords used in this current experiment were divided into three sets of sixty items each based on the attestation of consonant onset clusters, and mean acceptability ratings derived from the pilot study.

Care was taken to avoid items that closely resembled real words; however, one item, bwal (in the UA condition) was inadvertently included that bore a strong resemblance to two English words (ball and brawl). All stimuli were recorded as 16-bit sound with a sampling rate of 44100 kHz in a quiet room. These recordings were normalized for intensity and equated for duration at 500 ms using PRAAT (Boersma & Weenink, 2018). All items were checked by listening and visual inspection of spectrograms to ensure that they were pronounced as intended. Since the stimuli were recorded naturally, we did not control for the duration of onset consonant clusters across the conditions.

2.3. Procedure

We used Matlab PsychToolbox (Kleiner et al., 2007) to present the auditory stimuli and record behavioral responses. Participants performed an untimed two-alternative forced choice (2AFC) acceptability judgment task while MEG and EEG data were simultaneously collected. The participants were asked to “press one of two buttons with your left index or middle finger to indicate whether you think the word could make a new word in the English language or not”. The stimuli were presented in randomized order in two blocks of 90 trials, with a brief rest period between the blocks. Trials began with a 400 ms fixation period during which a small cross was shown at the center of the screen. This was followed by the presentation of the 500 ms CCVC auditory stimulus over pneumatic earphones. After hearing the stimulus, participants responded with a left-hand button-press. There was a 500 ms intertrial interval following the button press. To minimize potential MEG/EEG artifacts, participants were instructed to maintain the fixation on the screen in front of them and blink only after responding. The total duration of the experiment was about 30 minutes.

2.4. Neural Data Acquisition and Processing

2.4.1. MEG an EEG Acquisition

Simultaneous MEG and EEG data were collected using a whole head Neuromag Vectorview system (Megin, Helsinki, Finland) in a magnetically shielded room (Imedco, Hägendorf, Switzerland). Data were recorded from 306 MEG channels (204 planar gradiometers and 102 magnetometers), 70 EEG channels with nose reference, and two electro-oculogram (EOG) channels to identify blinks and eye-movement artifacts. The data were filtered between 0.1 and 300 Hz and sampled at 1000 Hz. A FastTrack 3D digitizer (Polhemus, Colchester, VT) was used before testing to determine the positions of anatomical landmarks (preauricular points and nasion), the EEG electrodes, four head-position indicator (HPI) coils, and over 100 additional surface points on the scalp for co-registration with the structural MRI data. The position of the head with respect to the MEG sensor array was measured using the HPI coils at the beginning of each block of trials.

2.4.2. Structural MRI

Anatomical T1-weighted MRI data for each participant were collected with a 1.5 T or 3 T Siemens scanner using an MPRAGE sequence. Freesurfer software was used to reconstruct the cortical surface and to identify skull and scalp surfaces for each participant (Dale et al., 1999). Individual participants’ data were aligned into a common average surface using a spherical morphing technique (Fischl et al., 1999).

2.4.3. Source Reconstruction and ROI Identification

We used the MNE software (Gramfort et al., 2014) to create MRI-constrained cortical minimum-norm source estimates for the task-related MEG and EEG data. For the forward model, 3-compartment Boundary Element Model was constructed for each subject using the skull and scalp surfaces segmented from the MRI. The source space was defined by placing current dipoles at about 10000 vertices of each reconstructed cortical hemisphere; the orientation of the dipoles was not constrained. All source estimates were calculated at the individual subject level and then transformed into the common average cortical surface.

To define regions of interest (ROIs) that satisfy the statistical and inferential requirements of Granger causality analysis we used an algorithm that relies on the similarity and strength of activations of MNE time series at each source space vertex over the cortical surface for the 100–500 ms time period after stimulus onset (Gow & Caplan, 2012; Gow & Nied, 2014). The activation map obtained by averaging the source estimates over all participants and conditions was used to identify the ROIs. First, vertices with mean activation over the 95th percentile during the t100–500 ms time window were identified as seeds for potential ROIs. Vertices located within 5 mm of local maxima were excluded and pairwise comparisons were then performed between all potential seeds to identify redundant time-series information. This was done to satisfy Granger analysis’s assumption that each signal carries unique predictive information. Redundancy was quantified as the Euclidean distance between vertices’ normalized activation functions. If an ROI’s activation function was within 0.9 standard deviations of another ROI with a stronger signal, the ROI was omitted. The spatial extent of individual ROIs was determined using the same measure similarity in activation function among contiguous vertices. When the distance was within 0.5 standard deviations of an ROI’s seed, the vertex was included in the ROI. We used Freesurfer’s automatic parcellation utility to label the ROIs based on their sulcal and gyral locations. The ROIs determined from the group average data were transformed onto the cortical surfaces of individual participants. Finally, to account for individual differences in brain structure and functional differentiation, we identified representative individual vertices within each ROI for each participant to provide representative time courses in Granger analyses.

2.4.4. Kalman Filter based Granger Causality Analysis

Effective connectivity between ROIs was determined using Granger causality analysis based on a Kalman filter approach (Milde et al., 2010; Gow & Caplan, 2012). Kalman filtering has been used in Granger analysis of BOLD, EEG, MEG, and multimodal data (Valdes-Sosa et al., 2009; Havlicek et al., 2010, 2011; Milde et al., 2010; Gow & Nied, 2014), because it addresses the signal stationarity assumption of Granger causation analysis, is resistant to subsistent noise, and allows for the estimation of the coefficients for time-varying multivariate autoregressive (MVAR) prediction models making it possible to measure the strength of Granger causation between all ROIs at each time point.

Averaged time series data from each subject’s ROIs were submitted to Granger analysis. For each ROI, first, a full MVAR model for predicting the activity in one ROI from the past values of activity in all ROIs was generated. Then, restricted counter models were created in which one of the other, potentially causal ROIs was excluded. Granger Causality is an inference relying on the ratio of error terms for full vs. restricted prediction models. For two ROIs, when the prediction error for ROI1 at time step t is reduced by inclusion of ROI2 at time step t - 1 into the model accounting for the fact that ROI1 at t - 1 (and previous time steps) predicts itself at time t, then ROI2 is said to have a causal influence on ROI1. Thus, we can make an inference that the presence of ROI2 in the model can be used to make a prediction about ROI1 activity and ROI2 Granger causes activation changes or influences ROI1 activation. The strength of this causality was measured at each time point by the Granger Causality Index (GCI), which is defined as the logarithm of the ratio of the prediction errors for the two models (Milde et al., 2010).Averaged time series data from each subject’s ROIs were submitted to Kalman filter-based Granger analysis. For each ROI, first, a full model for predicting the activity in one ROI from the past values of activity in all ROIs was generated. Then, restricted counter models were created in which one of the other, potentially causal ROIs was excluded. In the models, five samples (1000 Hz) preceding each time point were used. This model order was identified heuristically because Akaike and Bayesian Info Criteria failed to determine a single optimal model order. A 100-ms initial time period was added to allow the Kalman filter to converge; thus, the Granger Causality was computed over the time window of 0–500 ms. The significance of GCI at each time point was determined by using a bootstrapping method (Milde et al., 2010).

2.5. Statistical Analyses

For the analysis of the acceptability judgements, we used lme4 (Bates et al., 2012) and lmerTest (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff, and Christensen, 2017) packages in R (R Core Team, 2022) to perform a logistic mixed-effects analysis of the relationship between acceptability rates and nonword type (3 levels: AA, UA, UU). We first ran the full model with UA condition as the reference level and then reran the model one more time with AA condition as the reference level to be able to report the AA vs. UU comparison statistics. Nonword type was treated as a fixed effect. We used random intercepts and slopes for nonword type by participants and random intercepts for nonword type by items. We did not include random slopes for nonword type by item because nonword type is a between-item effect. We reported the model estimation of the change in acceptance rate (in log odds) from the reference category for each fixed effect (b), standard error of the estimate (SE), Wald z test statistic (z), and the associated p values.

The influence of an ROI on another was quantified by counting the number of time points for which the uncorrected GCI significance value was p<0.05 within the 100–500 ms post-stimulus time window of interest. Previous neurophysiological studies using similar consonant onset cluster well-formedness manipulations have shown sensitivity to phonotactic violations in this time window (Wagner et al., 2012; Rossi et al., 2013; Gow & Nied, 2014). Our analyses first focused on baseline pattern of causation where all three conditions were combined to identify the overall network responsible for acceptability judgments at the word level. We then contrasted trials on the continuum of phonotactic attestation and phonological acceptability in which Attested/Acceptable (AA) vs. Unattested/Acceptable (UA), Unattested/Acceptable (UA) vs. Unattested/Unacceptable (UU) and Attested/Acceptable (AA) vs. Unattested/Unacceptable (UU) nonwords were compared. Differences between conditions were evaluated using a binomial test (Tavazoie et al., 1999) comparing the number of significant time points in each condition within the time window of interest. Effects were reported as significant at α = 0.05 after correction for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995).

3. Results

3.1. Acceptance Rates

The nonwords received a mean acceptance rate of 0.73 (SD=0.44) in the AA condition, 0.72 (SD= 0.45) in the UA nonword condition, and 0.16 (SD=0.36) in the UU nonword condition. Results of the logistic mixed-effect regression model showed that while the acceptance rates in the UA condition were not significantly different than those in the AA condition (b = 0.079, SE = 0.24, z =0.33, p =.741), they were significantly lower in the UU condition (b = 3.40, SE = 0.35, z =9.70, p <.0001). Acceptance rates were also significantly lower in the UU condition than in the AA condition (b = 3.48, SE = 0.40, z =8.80, p <.0001) (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Average proportion of acceptance (“Yes”) responses in the three conditions across the continuum of phonotactic attestation and phonological acceptability. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean, stars indicate the significance of pairwise comparisons (p<.0001).

3.2. Regions of Interest

The process for identifying clusters of cortical source locations associated with activation peaks that share similar temporal activation patterns resulted in 38 ROIs associated with overall task-related activation (Figure 2, Table 1). As expected, these included 3 superior temporal gyrus ROIs (L-STG1, R-STG1, R-STG2) in regions with neural sensitivity to acoustic-phonetic structure (Mesgarini et al., 2014). Yamamoto et al. (2019) propose that the right STG region plays a special role in linking auditory feedback with internal representations of speech sounds. Importantly, ROIs were identified that were consistent with associative (lexical) and articulatory mediation of acceptability judgements. Five regions, L-SMG1, L-MTG1, L-ITG1,2 and R-ITG1 spanned regions associated with lexical representation (Hickok and Poeppel, 2007; Gow, 2012). Left anterior ITG (L-ITG1) is implicated in lexico-semantic processing (Ischebeck et al., 2004; Patterson, Nestor and Rogers, 2007). Hickok and Poeppel specifically identify the posterior MTG and adjacent posterior ITS as lexical interface regions. Both L-ITG2 and R-ITG1 spanned regions that encompass posterior ITG, and L-ITG1 anterior ITG. Moreover, MEG source reconstructions commonly show a bias towards superficial sources that may make some sulcal sources appear more gyral. Consistent with the models of both Hickok and Poeppel (2007) and Gow (2012), these posterior ROIs may mediate the mapping between wordform structure and meaning. Both models attribute more anterior parts of the middle temporal gyrus and inferior temporal gyrus to semantic representation. Ghaleh et al. (2019) found that lesions of the left aMTG were associated with decreased sensitivity to the phonotactic regularity of speech. Located between posterior MTG (lexical interface) and anterior MTG (combinatorial network), the L-MTG1 ROI together with the L-ITG1 ROI may play a transitional role between those functions in the ventral speech processing stream.

Figure 2.

Regions of interests (ROIs) visualized over an inflated averaged cortical surface. Lateral (top) and medial (bottom) views of the left and right hemisphere are shown. For further description of the ROIs, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Regions of interests (ROIs) used in Granger causation analyses, as identified from averaged task-related activation. MNI coordinates indicate the source locations showing the highest average activation across participants within each region.

| Label | Location | MNI Coordinates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left Hemisphere | X | Y | Z | ||

| Temporal | L-STG1 | Superior Temporal Gyrus | −64 | −31 | 9 |

| L-MTG1 | Middle Temporal Gyrus | −63 | −16 | −15 | |

| L-ITG1 | Inferior Temporal Gyrus | −48 | −7 | −39 | |

| L-ITG2 | Inferior Temporal Gyrus | −56 | −57 | −10 | |

| Parietal | L-SMG1 | Supramarginal Gyrus | −61 | −47 | 23 |

| L-SPC1 | Superior Parietal Cortex | −13 | −87 | 35 | |

| L-SPC2 | Superior Parietal Cortex | −13 | 56 | 63 | |

| L-postCG1 | Posterior Central Gyrus | −61 | −14 | 24 | |

| L-postCG2 | Posterior Central Gyrus | −49 | −20 | 57 | |

| Frontal | L-ParsOrb1 | Pars Orbitalis | −44 | 35 | −13 |

| L-ParsTri1 | Pars Triangularis | −52 | 25 | 11 | |

| L-SFG1 | Superior Frontal Gyrus | −7 | 61 | 9 | |

| L-SFG2 | Superior Frontal Gyrus | −12 | −2 | 67 | |

| L-SFG3 | Superior Frontal Gyrus | −8 | 21 | 60 | |

| Occipital | L-LOC1 | Lateral Occipital Complex | −35 | −88 | −16 |

| L-LOC2 | Lateral Occipital Complex | −11 | −103 | 5 | |

| L-LOC3 | Lateral Occipital Complex | −45 | −82 | 5 | |

| L-LOC4 | Lateral Occipital Complex | −10 | −97 | −13 | |

| Right Hemisphere | |||||

| Temporal | R-STG1 | Superior Temporal Gyrus | 65 | −33 | 5 |

| R-STG2 | Superior Temporal Gyrus | 56 | 2 | −5 | |

| R-MTG1 | Middle Temporal Gyrus | 64 | −19 | −12 | |

| R-ITG1 | Inferior Temporal Gyrus | 54 | −54 | −16 | |

| Parietal | R-AG1 | Angular Gyrus | 37 | −68 | 43 |

| R-SPC1 | Superior Parietal Cortex | 20 | −89 | 25 | |

| R-SPC2 | Superior Parietal Cortex | 12 | −71 | 52 | |

| R-SPC3 | Superior Parietal Cortex | 29 | −53 | 63 | |

| R-postCG1 | Posterior Central Gyrus | 8 | −37 | 77 | |

| R-postCG2 | Posterior Central Gyrus | 60 | −11 | 14 | |

| R-postCG3 | Posterior Central Gyrus | 58 | −9 | 36 | |

| Frontal | R-ParsTri1 | Pars Triangularis | 50 | 33 | 5 |

| R-cMFG1 | Caudal Middle Frontal Gyrus | 36 | 5 | 58 | |

| R-SFG1 | Superior Frontal Gyrus | 17 | 57 | 24 | |

| R-SFG2 | Superior Frontal Gyrus | 8 | 39 | 50 | |

| R-SFG3 | Superior Frontal Gyrus | 17 | 22 | 58 | |

| R-SFG4 | Superior Frontal Gyrus | 9 | −1 | 67 | |

| Occipital | R-LOC1 | Lateral Occipital Complex | 18 | −100 | 5 |

| R-LOC2 | Lateral Occipital Complex | 33 | −88 | −13 | |

| R-LOC3 | Lateral Occipital Complex | 48 | −76 | 8 | |

Three regions in the ventral post central gyrus, L-postCG1, R-postCG2 and R-postCG3, aligned with portions of the sensory homunculus that are associated with the control of speech articulators (Pardo et al., 1997) and implicated in the perception of spoken language (Tremblay and Small, 2011a,b; LaCroix et al., 2015; Schomers and Pulvermüller, 2016). Two ROIs were identified within the LIFG, L-ParsTri1 and L-ParsOrb1, along with one right hemisphere homolog, the R-ParsTri1. As previously noted, functional interpretation of these regions is controversial given some evidence that they are sensitive to phonological well-formedness (Vaden et al., 2011; Berent et al., 2014) even though damage to these regions is not associated with changes in phonological acceptability judgements (Ghalel et al., 2018). Independent work links the pars orbitalis to lexical semantic control processes including search (de Zubicaray and McMahon, 2009; Price 2010; Noonan et al., 2013; Conner et al. 2019; Becker et al. 2020; Jackson, 2020 de Zubicaray and McMahon, 2009; Price 2010; Noonan et al., 2013; Conner et al. 2019; Becker et al. 2020; Jackson, 2020) and the left pars triangularis to working memory maintenance and retrieval (Hagoort, 2005; Thompson-Schill, Bedny & Goldberg, 2005; Grodzinsky and Amunts, 2006; Matchin, 2018). The right pars triangularis is less well understood, although evidence that inhibition of this region in people with aphasia reduces phonological, but not semantic errors in naming (Harvey et al., 2019) suggests a possible role in inefficient phonologically guided strategic lexical search. Interestingly, a third component of the LIFG, the pars opercularis, which is implicated in control processes related to phonetic processing and motor control (Amunts et al., 2004; Heim et al., 2005), was not identified by our method as a separate ROI.

Other ROIs included lateral occipital regions that may reflect the visual fixation’s role in cueing auditory attention, a sensorimotor region (R-postCG1) likely to play a role in initiating button presses (Overduin & Servos, 2004), superior frontal and parietal regions implicated in control processes and response suppression (Dong et. al., 2000; Hu et al., 2016; Koenigs et al., 2009; Seghier, 2013; Wild et al., 2012; Shomstein & Yantis, 2006; Aron et al., 2003; Kim, 2010; Vilberg and Rugg, 2008), and the right caudal middle frontal gyrus (R-cMFG1), a region implicated in attentional control (Japee et al., 2015). While acknowledging the challenges of functional interpretation of any brain region, we reference these glosses of function in the following results for ease of readability.

3.3. Overall Patterns of Causation

Figure 3 shows the causal influence by other ROIs on L-STG1 for data averaged over the three conditions (AA, UA, and UU). Influence was quantified as the number of timepoints in the interval between 100–500 ms post stimulus onset with GCi values. (The influences of all ROIs on L-STG1, both for the condition-independent Granger analysis and for the three condition-specific analyses are shown in Table S1 in Supplementary Materials). The strongest observed influences on L-STG1 were by R-LOC3 and R-SFG4. Prominent influences came also from ROIs in areas that are in regions associated with lexical representation (L-ITG1,2, L-SMG1 and L-MTG1, from ROIs in areas implicated in sensorimotor articulatory representations (R-postCG2,3), and from LIFG ROIs (L-ParsOrb1 [BA 47] and L-ParsTri1 [BA 45]).

Figure 3.

Causal influences on L-STG1 (yellow) by the other ROIs for data combined over the three stimulus conditions. The diameter of the green bubbles indicates the number of time points with significant GCI values in the 100–500 ms window. A time point was included in the count if the p-value determined by bootstrapping analysis for the GCI reached α = 0.05 (uncorrected).

3.4. Effects of Attestation (AA vs. UA)

Comparisons between experimental conditions were made using binomial tests to compare the number of timepoints between 100–500 ms post stimulus onset in which GCi values had a p < 0.05 in each condition. The comparison between influences on L-STG1 in the AA versus UA conditions is shown in Figure 4. Significantly stronger influences in the AA than the UA condition were found for 7 of the 38 ROIs. The largest effects were found for L-ITG2 and L-MTG1 in the left hemisphere (associated with lexical representation) and R-postCG3 in the right hemisphere (associated with articulatory representation) (all p <0.001, FDR corrected). The other regions showing significantly larger influence on L-STG1 for attested forms (AA) were L-SPC2, R-SPC1, R-SFG4 (p<0.01) (all involved in attention and control processes), and R-STG1 (p<0.01) (linking auditory feedback with internal representations of speech sounds).

Figure 4.

Differential influences of the other ROIs on L- STG1 (shown in yellow) for AA-UA contrast. The bubbles indicate ROIs that showed significantly (p<0.05, with FDR correction) larger number of time points with significant GCI values in the 100–500 ms window in the AA (blue) or UA (purple) condition. The diameter of a bubble corresponds to the difference in the number of time points between conditions.

Three ROIs showed larger influence on L-STG1 in the UA than the AA condition: R-ParsTri1, R-cMFG1, and R-postCG1 (p<0.01). The influence by R-postCG1 was likely related to the button press. The R-cMFG1 ROI in the right middle frontal gyrus is implicated in shifting attention from exogenous to endogenous control and R-ParsTri1 involvement is consistent with inefficient phonological search and control processes evoked by lexically unattested phonotactic patterns.

We also examined potential indirect influences on L-STG1 by identifying differential influences by other ROIs on L-MTG1 (Fig. S1 in supplementary materials), following evidence that left SMG [the dorsal wordform area] influences on pSTG are sometimes mediated by the MTG. The results showed significantly stronger influences for L-SMG1 (p < 0.001) on L-MTG1 in the AA than in the UA condition. Furthermore, since behavioral results did not show significant differences between AA and UA nonwords, we conducted further analysis and divided the trials down by the response (e.g., nonwords that are accepted and rejected regardless of the pre-assigned attestation or acceptability). Figure S2 in Supplementary Materials depicts ROIs that showed significantly different influences on the L-STG1 ROI between the accepted and rejected nonwords. Notably, ROIs associated with lexical, articulatory, and phonological/semantic search did not show differences between the accepted vs. rejected nonwords.

Overall, these results suggest that listeners reference representations of familiar words (via L-MTG1) and familiar articulatory patterns (via R-postCG3) when they judge those words to be acceptable and engage in effortful phonological search (via R-ParsTri1), possibly for phonetically similar items, when familiar representations are not immediately available.

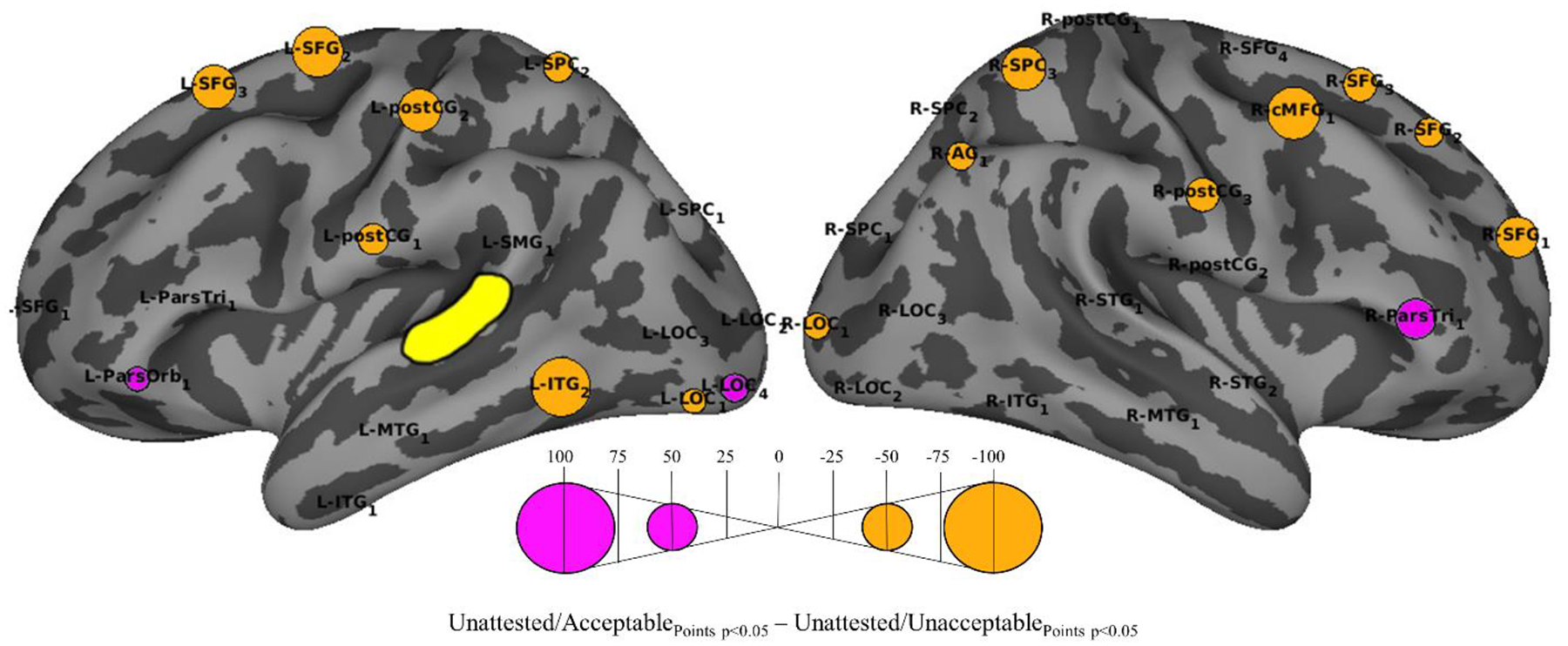

3.5. Effects of Acceptability (UA vs. UU)

Contrasts between the UA and UU conditions revealed 18 ROIs that showed significant differences in the strength influences on L-STG1 as a function of acceptability (Figure 5). Three ROIs showed stronger influence in the UA condition: R-ParsTri1 (p < 0.001) (phonological search and control processes), L-ParsOrb1 (p < 0.005) (semantic control) and L-LOC4 (p < 0.001) (visual cueing of auditory attention).

Figure 5.

Differential influences of the other ROIs on L- STG1 (yellow) for UA-UU contrast. The bubbles indicate ROIs that showed significantly (p<0.05, with FDR correction) larger number of time points with significant GCI values in the 100–500 ms window in the UA (purple) or UU (orange) condition.

Stronger influences in the UU than the UA condition were found for 15 ROIs: L-ITG2, L-SFG2,3, L-SPC2 , L-postCG2, R-SFG1,3, R-SPC3, R-cMFG1, R-postCG3 (all p<0.001) and L-postCG1, R-SFG2, L-LOC1, R-AG1, R-LOC1 (p<0.005). Collectively, these regions are associated with lexical representation (L-ITG2), articulation (L-postCG1,2 and R-postCG3), allocation of memory and attention (bilateral SFG and SPC areas, R-AG1 and R-cMFG1), and visual cueing of attention (bilateral LOC areas).

These results suggest that the judgments were influenced by attention driven semantic control processes (L-ParsOrb1) when the nonword was acceptable, and by a large network of attention and control mechanism together with lexical and articulatory means when the nonword was unacceptable.

3.6. Effects of Naturalness (AA vs. UU)

Figure 6 shows ROIs that showed significantly different influences on L-STG1 between the AA and UU conditions. For 4 ROIs the influence was stronger in the AA condition. The largest effects were found for L-MTG1 (associated with lexico-semantic representation) and R-SPC1 (cognitive control and response suppression). The other ROIs showing significantly larger influence on L-STG1 in the AA condition were L-ParsOrb1 [BA 47, part of LIFG] (associated with semantic retrieval and control) and L-LOC4 (all p < 0.001, FDR corrected).

Figure 6.

Differential influences of the other ROIs on L-STG1 (yellow) for AA-UU contrast. The bubbles indicate ROIs that showed significantly (p<0.05, with FDR correction) larger number of time points with significant GCI values in the 100–500 ms window in the AA (blue) or UU (orange) condition.

Stronger influences on L-STG1 in the UU condition were found for 15 ROIs: L-ITG1, L-SFG1,2,3, L-postCG1,2 and L-LOC1 in the left hemisphere (all p < 0.001, FDR corrected), and R-cMFG1, R-SFG1,2, R-SPC2, R-postCG1,2, R-AG1, R-LOC1 in the right hemisphere (all p < 0.001, FDR corrected). The increased influence of L-ITG1 and L-postCG1,2 and R-postCG2 are consistent with increased recruitment of lexical and articulatory influences on L-STG1 for the most unnatural forms (UU). The increased influence of frontal and parietal control regions suggests that the most unnatural forms produce the strongest task demands.

We further examined two ROIs for which the observed results were unexpected following the hypotheses put forward above. L-SMG1 and L-ParsTri1 influences on L-STG1 did not show significant differences in the comparisons between conditions. Instead, both ROIs showed overall significance, but no significant differences between conditions in influence on L-STG1 (Table S1 in Supplementary Materials).

To summarize, acceptance of natural (attested and acceptable) phonotactic patterns relied primarily on lexical mechanisms with a minimal role of control processes. However, when the nonword was unnatural, bilateral attention and control network together with left hemisphere articulatory regions influenced the judgment process.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to (i) characterize the dynamic cortical processes and mechanisms that support phonological acceptability judgments and (ii) determine the degree to which these judgments are driven by rule/constraint, associative, and articulatory mechanisms. Effective connectivity analyses revealed a diverse pattern of differences in the strength of influences on the left pSTG among the three conditions. Our results suggest that phonological acceptability judgments are a product of a search process that looks for lexical, phonological, and articulatory wordform representations depending on the attestation and acceptability of the sound combinations. Several of the ROIs identified in the comparisons were in regions that in the literature have been associated with lexical word representation (L-SMG1, L-MTG1, and L-ITG1,2 and R-ITG2), sequence processing or controlled lexical and phonological search and access (L-ParsOrb1, L-ParsTri1, and R-ParsTri1), and sensorimotor representations (bilateral postCGs).

The involvement of lexical regions is notable, given that two of the three conditions consisted of items with unattested onset consonant clusters, none of the stimuli were words, and the participants knew they were not going to hear any words. However, none of those regions are solely grammatical, lexical, or articulatory and likely reflect a lot of other processes too. In fact, this diversity is inconsistent with a single mechanism explanation. Our results suggest that any rule, lexical, or articulatory restriction would need to be represented across a widely distributed network and that the act of making phonological judgments involves multiple stages of evaluation based on lexical and articulatory evaluation orchestrated in some cases by active cognitive control processes.

4.1. Attestation

Nonwords with unattested and thus theoretically unacceptable onset consonant clusters received acceptability ratings equally high as nonwords with attested and putatively well-formed onsets did. This result might be due in part to the characteristics of our stimuli. All the acceptable nonwords start either with fricatives (attested ones) or with a mix of fricatives and stops (unattested ones), and there is evidence that fricatives seem to be processed differently than other sounds (Galle et al., 2019). Another likely explanation of this behavioral finding is that the judgments were influenced by perceptual repair of unattested patterns (Massaro & Cohen, 1983; Pitt, 1998; Davidson, 2007; Gow & Nied, 2014; Gow et al., 2021). The current neural results provide some support for this interpretation. The left SMG, the dorsal lexicon area, which mediates the mapping between sound and articulation (Gow, 2012) showed consistently influence on pSTG across the comparison conditions (see Table S1 in supplementary material). Independent evidence (Gow & Nied, 2014; Gow et al., 2021) associates this dynamic with lexically mediated perceptual repair of unattested fricative onset clusters (e.g., categorizing an unattested /sr-/ onset cluster as an attested /shr-/ onset).

The consistent lexical influences of the SMG across the attested and unattested acceptable conditions (AA versus UA) were overlayed by evidence from increased top-down lexical influence for attested (AA) items from L-ITG2 and L-MTG1. Unlike the SMG, these regions are associated with semantic aspects of lexical representation, which would be expected to be more strongly activated by nonwords with onset clusters that unambiguously appear in known words with semantic representations. For example, whereas the unattested onset cluster in the UA nonword shlame may weakly activate the words with perceptually similar onset clusters (e.g., slain, shame), attested onset clusters such as flane more closely resemble clusters found in words with full semantic representations including flame and flake and so would be expected to produce stronger semantic activation.

Like lexical familiarity, articulatory familiarity appears to influence the evaluation of nonwords with attested onset clusters. The dorsal postcentral gyrus region R-postCG3 also produced stronger influences on L-STG1 for attested versus unattested acceptable nonwords. This ROI aligns with a portion of sensorimotor cortex implicated in oral movement (Pardo et al., 1997) and phonological processing (Schomers and Pulvermüller, 2016). BOLD imaging results comparing the articulation of vowels and syllables taken from bilingual’s first versus second languages provide converging evidence that this region is sensitive to the relative frequency of articulatory patterns (Treutler and Sörös, 2021).

Further support for the role of articulatory effects on speech perception in our experiment comes from the stronger influence of R-STG1 on L-STG1 in the AA versus UA condition. Yamamoto et al. (2019) linked right STG activation to covert speech and suggested that right STG influences on left STG reflect the influence of covert speech on the perception of heard speech. The stronger influence of L-SPC2, R-SPC1, and R-SFG4, implicated in attention and control processes, on L-STG1 for the AA compared with UA items likely reflects the need to devote additional effort to the search of lexical and articulatory wordform representations for AA nonwords.

It is notable that LIFG regions did not show differential influences on L-STG1 for nonwords with attested, lawful patterns than it did for nonwords with putatively ill-formed clusters that violate English sonority constraints. Such an influence would be predicted by the rule/constraint account under the hypothesis that that LIFG is the locus of rule/constraint knowledge or processing. Furthermore, the results are inconsistent with the hypothesis that ill-formed, unattested clusters were judged to be acceptable due to rule-mediated perceptual repair. If positive evidence were found for all three influences during phonological judgements, one could argue that lexical and articulatory factors influence online acoustic-phonetic processing, but their effects on the evaluation of phonological judgment are mediated by rules or constraints that have been shaped over time by these factors as suggested by cophonological and grounded theories of phonology. In the absence of independent LIFG effects, it appears that the lexical and articulatory advantages of attestation are not mediated by abstract rules or constraints.

4.2. Acceptability and Naturalness

What makes some forms unrepairable and therefore unacceptable? Contrasts showed that unacceptable (UU) forms engaged a broader network of frontal and parietal control regions than did either of acceptable conditions (AA and UA). For example, in the AA vs UU comparison, the combination of stronger L-ITG1 influence with weaker L-MTG1 influence may reflect enhanced lexical search but without leading to semantic access associated with a more anterior L-MTG1 activation. This may suggest that the default judgment among listeners is to accept novel forms, and that strongly unnatural phonotactic structures trigger attention driven re-evaluation. This should not be surprising, as speech input, with very few exceptions, is predictably well-formed.

In contrast, acceptable forms elicited stronger influence of L-ParsOrb1 on L-STG1 in all comparisons involving unacceptable forms (UA versus UU and AA versus UU). A wide body of research implicates activation of left pars orbitalis (BA 47) in semantic retrieval and control processes (de Zubicaray & McMahon, 2009; Price 2010; Noonan et al., 2013; Conner et al. 2019; Becker et al. 2020; Jackson, 2020). Semantic control is the ability to selectively access and manipulate meaningful information based on context demands (Jackson, 2020). In a meta-analysis study, Jackson (2020) found that semantic control depends on a left hemisphere specific network of IFG, posterior MTG and ITG, and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC). Therefore, the left ParsOrb influence on L-STG1 observed in our study could be thought of more like a control process where lexical forms were selected. Additionally, the stronger influence of L-MTG1 on L-STG1 for the AA vs UA and AA vs. UU nonwords suggests that this control process was a semantic control process to access the word form representations for natural (AA) nonwords.

However, the above referenced control process works differently for UA nonwords where the L-MTG or L-ITG2 influence, and therefore the lexical representation, was absent. R-ParsTri1 (implicated in phonological access during word retrieval) showed stronger influence on L-STG1 for UA vs AA and UA vs UU comparisons (Figs. 4 and 5). This suggests that the R-ParsTri effect is specific to UA nonwords and related to the coordination of a search in which there was no obvious lexical support since the onset clusters of these nonwords are not included in the lexicon. The influences from L-ParsOrb1 and R-ParsTri1 on L-STG1 for UA nonwords can be thought of as evidence for selectively accessing the given unattested sound combinations. In other words, for UA nonwords, since the phoneme sequences are unattested, there is nothing to access; therefore, an active search for the nearest familiar word or even articulatory pattern was initiated. This would prompt potential acoustic-phonetic reanalysis (thus the influence on L-STG1). When this reanalysis cannot get lexical support from SMG/pMTG the form would be rejected. We think most of the UA words got this lexical support and were accepted. Together, this suggests that the left ParsOrb is more associated with acceptability of a novel form rather than attestation.

It is paradoxical that the same lexical and articulatory influences on L-STG1 that follow from attestation in AA played an outsized role in the processing of unacceptable forms in UU. This was the case for both L-ITG2 and R-postCG3 which showed stronger influences in AA than UA, but stronger effects for the unacceptable UU items than the acceptable UA items. We hypothesize these dynamics reflect different processes in AA and UU nonwords. In UU nonwords, we suggest that the stored articulatory (R-postCG3) dynamics attempts at restructuring of acoustic-phonetic representations in L-STG1 to bring those representations into alignment with stored representations. We suggest that UU nonwords are simply too phonetically dissimilar to stored forms to support lexical resonance, even after articulatory restructuring.

Additionally, the results of Miyamoto et al. (2016) provide context for interpreting the influence of R-postCG3 ROI on L-STG1 for both AA and UU nonwords. Miyamoto and colleagues investigated the cortical representation of the oral area in postCG by identifying the somatotopic representations of the lips, teeth, and tongue using fMRI. They found that the oral area is hierarchically organized across the rostral portion of the primary somatosensory cortex in which the representation of the tongue was located inferior to that of the lip. In a post hoc analysis, we compared the MNI coordinates of our R-postCG3 area with those reported in Miyamoto et al. (2006) and found that our R-postCG3 coincide with their lip area. The role of this postCG area for AA and UU nonwords could be related to the similarity of onset consonant clusters (articulated with the tongue against or close to the superior alveolar ridge) across the two conditions (see Appendix for the list of nonwords used).

These results from the AA vs. UU and UA vs. UU comparisons suggest that processing of acceptable (natural) nonwords involved a phonological search mechanism that selectively accessed the sound combinations (via L-ParsOrb1 and R-ParsTri1) for UA nonwords and the wordform representations (via L-ParsOrb1 and L-MTG1) for AA nonwords, whereas the processing UU nonwords initiated an effortful search process without lexical support.

5. Conclusion

This study examined the factors that support phonological acceptability judgments across the continuum of phonological acceptability and phonotactic attestation. Our review of the empirical literature suggests that available evidence for a LIFG locus for phonological rule processing is potentially attributable to task specific working memory and attention demands. Moreover, our results are inconsistent with claims that LIFG regions play a central role in phonological judgments. Instead, our results suggest that phonological acceptability judgments are mediated by representations of familiar wordforms and articulatory patterns. We hypothesize that acceptability judgements reflect the degree to which test stimuli resemble specific stored forms. Influences on acoustic-phonetic regions reflect resonance when input representations are sufficiently to draw support from stored forms either with restructuring (perceptual repair) for unattested forms judged acceptable, or without significant forms that do not require restructuring. Novel forms are only rejected if effortful processing fails to restructure their input representations sufficiently to bring them into alignment with stored lexical or articulatory representations.

In conclusion, phonological judgments do not provide a direct window on abstract constraints, but rather reflect processes related to word likeness and articulatory effort. Phonology remains a marvel of structurally constrained cognitive generativity. This work suggests that phonological acceptability judgments provide insight into structural properties of lexical and articulatory representations of individual forms that reflect language processing demands and shape our lexica.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Adriana Schoenhaut and Nao Suzuki for assisting in scanning, Tom Sgouros for programming support, and Adam Albright and David Sorensen for thoughtful comments and feedback on the work. We also thank the participants in our studies who volunteered their time and effort.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) grant R01DC015455 (P.I.: Gow)

Appendix

STIMULI

| Novel Words | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptable Attested | flane | flose | friss | shrime | slep | smike |

| flass | flul | frode | shrom | sliss | smiss | |

| flav | fluss | frome | shrop | sliv | smob | |

| flep | fral | frose | shrote | slobe | smobe | |

| flid | frane | frote | slalm | slome | smop | |

| flike | frass | frud | slame | slote | smul | |

| flime | freem | frul | slass | slud | smuv | |

| fliss | frem | fruss | slav | smad | snab | |

| flob | frid | shrab | sleem | smal | snote | |

| flobe | frike | shran | slem | smid | spame | |

| Unattested Acceptable | bwaim | bwobe | mlote | shlame | srime | vrid |

| bwain | bwop | mlud | shlid | srop | vrike | |

| bwal | bwul | mlul | shlime | srul | vrime | |

| bweem | bwus | mluss | shlob | sruv | vriss | |

| bwep | bwuv | pwain | shlome | vrad | vrob | |

| bwid | mlame | pweam | shlop | vrame | vrom | |

| bwime | mlime | pwid | shlote | vrane | vrome | |

| bwis | mliss | pwote | srane | vras | vrose | |

| bwiv | mlode | pwul | sras | vreem | vrote | |

| bwob | mlome | shlab | srike | vrem | vruss | |

| Unattested Unacceptable | fmal | sfob | zhnem | zhnote | zhvas | zhvode |

| fmame | sfode | zhnid | zhnud | zhveb | zhvom | |

| fmeem | sfome | zhnike | zhnul | zhveem | zhvome | |

| fmem | sfuss | zhnime | zhnuss | zhvem | zhvop | |

| fmid | zhnad | zhniss | zhpuss | zhvid | zhvose | |

| fmiv | zhnal | zhniv | zhvab | zhvike | zhvote | |

| sfab | zhnane | zhnob | zhvad | zhvime | zhvud | |

| sfal | zhnas | zhnom | zhval | zhviss | zhvul | |

| sfeb | zhneb | zhnop | zhvame | zhviv | zhvuss | |

| sfiv | zhneem | zhnose | zhvane | zhvob | zhvuv | |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Bibliography

- Albright A (2009). Feature-based generalization as a source of gradient acceptability. Phonology, 26(1): 9–41. doi: 10.1017/S0952675709001705 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albright A, & Hayes B (2003). Rules vs. analogy in English past tenses: A computational/experimental study. Cognition, 90(2), 119–161. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(03)00146-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K, Weiss PH, Mohlberg H, Pieperhoff P, Eickhoff S, Gurd JM, … & Zilles K (2004). Analysis of neural mechanisms underlying verbal fluency in cytoarchitectonically defined stereotaxic space—the roles of Brodmann areas 44 and 45. Neuroimage, 22(1), 42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anshen F, & Aronoff M (1988). Producing morphologically complex words. Linguistics, 26(4), 641–655. doi: 10.1515/ling.1988.26.4.641 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archangeli DB, & Pulleyblank DG (1994). Grounded phonology (No. 25). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ardila A, Bernal B, & Rosselli M (2017). Should Broca’s area include Brodmann area 47?. Psicothema, 29(1), 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR, Fletcher PC, Bullmore ET, Sahakian BJ, & Robbins TW (2003). Stop-signal inhibition disrupted by damage to right inferior frontal gyrus in humans. Nature Neuroscience, 6(2), 115–116. doi: 10.1038/nn1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axer H, von Keyserlingk AG, Berks G, von Keyserlingk DG (2001). Supra- and infrasylvian conduction aphasia. Brain Lang 76: 317–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader M, & Häussler J (2010). Toward a model of grammaticality judgments. Journal of Linguistics, 46(2), 273–330. doi: 10.1017/S0022226709990260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TM, & Hahn U (2001). Determinants of wordlikeness: phonotactics or lexical neighborhoods? Journal of Memory and Language, 44(4), 568–591. doi: 10.1006.jmla.2000.2756. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, & Bolker B (2012). Lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. R package version 0.999999-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer L (2001). Morphological Productivity. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511486210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M, Sommer T, & Kühn S (2020). Inferior frontal gyrus involvement during search and solution in verbal creative problem solving: A parametric fMRI study. Neuroimage, 206, 116294. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]