Abstract

Addressing patient-clinician communication barriers to improve multiple chronic disease care is a public health priority. While significant research exists about the patient-clinician encounter, less is known about how to support patient-clinician communication about lifestyle changes that includes the context of people’s lives. Data come from a larger photo-based primary care study collected from thirteen participants who were adults 60 or older with at least two chronic conditions, in English, Chinese (Cantonese or Mandarin), or Spanish. We use discourse analysis of three examples as anchor points demonstrating different interactional pathways for the photo-based communication. Patients and clinicians can move smoothly through a pathway in which photos are shared, clinicians acknowledge and align with the patient’s explanation, and clinicians frame their medical evaluations of food choices, nutrition suggestions, and shared goal-setting by invoking the voice of lifeworld (VOL). On the other hand, when clinicians solely press the voice of medicine (VOM) in their evaluations of patients’ pictures with little attention to patients’ presentations, it can lead to patient resistance and difficulty moving to the next activity. Because photo-sharing is still relatively novel, it offers unique interactional spaces for both clinicians and patients. Photo-sharing offers a sanctioned moment for a primary care visit to operate in the VOL and promote goal-setting that both parties can agree upon, even if clinicians and patients framed the activity as one in which patients’ lifeworld choices should be assessed as medically healthy or unhealthy based on the ultimate judgment of clinicians operating from the VOM.

Keywords: discourse analysis, patient-clinician communication, primary care, nutrition, photos

Patients with multiple chronic conditions (MCC) face many challenges especially around diet, and primary care clinicians have particular challenges treating them when it comes to food. Yet, patient-clinician communication about contextual factors important to MCC care can contribute to improved health outcomes. Nuanced understanding of the complexities of patients’ dietary habits can lead to clinical recommendations (e.g., referral to dietitian or community food resources) that improve disease-specific and other outcomes (Kirkman et al., 2012). In addition, overlooked contextual factors can lead to inappropriate care plans, poorer disease-specific outcomes and missed opportunities to address health-related social needs (Seligman, 2017).

However, for primary care clinicians, there are limited options available to them in the short, single clinic visit. While best practices suggest weight management interventions are multi-faceted to include behavioral interventions including eating, physical activity, and pharmacotherapy, the limits of the clinic visit and clinician training make the task so daunting (Tucker et al., 2021) that only 14% of residents felt adequately trained to offer nutritional counseling in primary care settings (Vetter et al., 2008). Besides asking patients to keep food diaries and offering referrals, clinicians are often left with little to discuss regarding diet. In addition to standardized nutritional assessments such as the food frequency questionnaire that can be difficult to implement in a busy primary care practice and require expertise in administering, clinicians may ask broad-scoping questions about particular aspects of the patients’ diet that rely on patient recall (e.g., food logs), that do not culminate in a holistic understanding of patients’ dietary habits, foods’ nutritional composition, and the external factors that influence food intake and preparation (Miller, 2005).

Research focused on lifestyle interventions have shown that patient resistance to clinician advice can be a window into potential obstacles (Barton et al., 2016). A significant clinical gap is the lack of clinically feasible, patient-centered interventions that support patient-clinician communication about the complexities of contextual factors in the care of older adult patients with MCC. Photos can be a powerful, effective way to communicate complex emotions, thoughts and experiences (Dobos et al., 2015).

Photos are one way that patients can quickly share a more holistic presentation of their lives and concerns with their clinicians and have been shown to be efficiently used in the clinical setting (Ho et al., 2021). In this article, we present findings from a photo-elicitation based intervention where patients took pictures of their everyday foods to then share with their primary care provider (PCP). Unlike photovoice, which has been used in other health communication studies and is implemented as a way to center (often marginalized) participant voices for researchers and policymakers (see e.g., Peterson et al., 2012; Wang & Burris, 1997), this clinical translation of photovoice differs in the use of the photos as part of the regular course of a patient’s primary care visit. The photos from our study created a conversational opening where patients were both sanctioned and given space to “voice” and describe their social lives outside of the clinic, what Mischler (1984) identifies as the voice of lifeworld (VOL), described in the next section. And yet, data showed that in all cases, clinicians and patients both framed the activity as one in which patients’ lifeworld choices should be assessed as medically healthy or unhealthy based on the ultimate judgment of clinicians operating from the voice of medicine (VOM). These conversations used in this study, which were recorded and interactionally analyzed, demonstrate conversational pathways that patients and clinicians take that are more or less productive toward shared goal setting in primary care visits which balance VOL/VOM talk. We present three cases that illustrate how clinician and patient move through the novel conversational intervention of photo-sharing and on to the next activity within the visit. In the following section, we present previous literature about the VOL/VOM and end with research questions.

Voices of Lifeworld and Medicine

Elliot Mischler (1984) introduced the concepts of VOL and VOM as a way of explaining the sometimes incongruous goals and perspectives of patients and clinicians in medical visits. In many clinical settings there is a presumption that patients and clinicians should speak in the VOM, framing the expectation for clinical talk as that which serves the clinicians’ medical assessment. Oftentimes, this manifests through closed-ended questions for diagnosis and subsequent treatment and can be seen as a VOM conversational frame. VOL conversations are ones which center on the patient’s experiences of illness, which can include many non-medical details such as how symptoms are affecting their everyday lives and anxieties. In addition, Mischler also explains that VOL and VOM can be analytic frames through which a researcher assesses the (in)appropriateness of particular talk in medical visits. So, not only is a particular way of communicating expected by both patients and clinician, but researchers may also view talk through a lens of VOM (or VOL). Thus, analysts in reviewing clinical talk can also center patients’ VOL voicings rather than treat them as interruptions of the expected VOM. Keeping this dynamic in mind, research has examined how patients assert agency by disallowing the regular progress of a medical visit, for example, from diagnosis to treatment recommendation (Koenig, 2011). Viewed either as an interruption of VOM (the smooth flow or progressivity) or through an analytic lens that centers patient assertions as attempts to voice their lifeworld without medical interruption, we take seriously Mischler’s question of what features in a medical interview demonstrate how clinician and patient vie for the centrality of VOL or VOM in any given moment.

In primary care, there are few moments in a visit where extensive talk about a person’s dietary habits makes sense even within chronic conditions that are food-sensitive. Some work has examined the ways that attending to talk and affirmations (Albury et al., 2018) as well as talk about non-clinical matters (Bergen, 2020) can advance behavioral change. However, there are few interventions that introduce a new clinical communicative moment (e.g., photo-sharing) in order to invite patients to voice their lifeworlds into the clinical space. Once this space is opened, it is not clear that clinicians will necessarily respond in ways that promote behavior change, but that is an empirical question this project seeks to answer.

Since the original publication of Mischler’s (1984) work, clinician-patient communication research has expanded exponentially, including recognizing the importance of patient activation and engagement as key to patient-centered care (Davis et al., 2005). It is now not only recognized but also expected that clinicians take seriously patient perspectives during medical visits. One definition of patient-centered care takes into account the VOL, despite the difficulty to do so within a context of the VOM (Lo, 2010), which is what Mischler originally called “attentiveness.” As Lo (2010) explains from interviews with clinicians, even in consultations where patients and clinicians come from the same ethnic background, their institutional positions as clinician (in the VOM) and patient (in the VOL) require that clinicians bear the responsibility of cultural brokering (or cultural labor) to translate between the two systems for patients.

Given the expectation that clinicians listen for VOL, and the recognition that dietary talk can be vague and time intensive, we created a novel intervention that carves out space in the visit for both patient and clinician to purposefully attend to a patient’s dietary talk through the sharing of photos. The hope is that this intervention allows for communication that both voices and attends to the lifeworld and that such visual and narrative attention to the patient’s life outside the clinic provides clinicians with a more holistic and situated view of patients’ dietary choices. Given that this new interactional part of the visit revolves around photo sharing in which both positive and negative eating/drinking behaviors are likely to be communicated, the following research questions drive our paper:

RQ1: How do clinicians and patients orient to and use the shared photos? And, does that talk follow an identifiable interactional pathway?

RQ2: How does photo-sharing talk affect clinicians’ recommendations and patient’s reaction to those recommendations?

Methods

Data Collection

As part of a larger study, data were collected from thirteen participants who were adults 60 or older with at least two chronic conditions from the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, who could also speak English, Chinese (Cantonese or Mandarin), or Spanish (Elixhauser et al., 1998). Participant prerequisites included the ability to use a smartphone or disposable camera and have a scheduled appointment with their PCPs within the next four months. Participants were recruited in waiting rooms, via clinician referrals, and from a study that examined the association between food insecurity and multiple chronic conditions among older adults (Ho et al., 2021). After their patient(s) granted consent to the study, PCPs were recruited by way of email and could be a physician or nurse practitioner.

In the 10 days before their visits, participants were given a 25-minute tutorial on taking photos with their smartphone or disposable camera, and were then directed to take photos in response to, “What aspects of your everyday life affect what you eat and how much you have to eat?” Participants were reminded by phone or text to take 1–2 pictures per day. Clinicians were told via email or in person to expect that their patient would be sharing photos to discuss during their next visit. Each visit was audio recorded. All procedures were IRB approved at the University of California, San Francisco.

Data Analysis

Data were transcribed and translated by professional transcription/translation services. All transcripts were then verified by language-concordant research assistants. The first two authors read through all transcripts and marked the audio and transcript of the main section of the visits that included the actual photo-based discussion.

Discourse Analysis (DA) is an umbrella term for an interdisciplinary variety of methodological and metatheoretical approaches to research (Hodges et al., 2008). DA focuses on studying recorded, naturally-occurring language in use, paying close attention to what actions talk accomplishes, and not using a specific step-by-step analytic process but being iterative in listening and relistening to data. For this article, we analyzed data from an interpretive social scientific and communicative perspective (Tracy, 2001), using theme-oriented discourse analysis (Roberts & Sarangi, 2005). The first two authors, trained in DA, read the transcripts and listened and re-listened to the audio files to produce a transcript reflecting pauses, overlaps and intonation. Our iterative analysis, therefore, examined the line-by-line interaction between clinician and patient to examine what occurs and what tasks they (attempt to) accomplish with their photo-sharing. In other words, analyzing the focal themes that are of relevance to medical contexts (Koenig et al., 2019; Roberts & Sarangi, 2005). In addition, we paid close attention to openings and closings to better understand how the photos-based portion of the visit (a novel/new type of interaction) fit within the larger (more established or institutionalized) medical visit. In this way, we attended to the analytic themes or concepts that have been studied in linguistics and sociology (Roberts & Sarangi, 2005). This initial analysis demonstrated that both patients and clinicians could initiate the photo-sharing and that sometimes clinicians would “set the agenda,” placing photo-sharing as one of the tasks to cover in the visit (discussed further in Ho et al., 2021). Our second pass of analysis then examined the action(s) that either clinician or patient accomplished through the photo-sharing. In some visits, the photo-sharing led directly to treatment recommendations, which patients accepted, while other conversations were more fraught with patient resistance.

As a whole research team, including a primary care physician, we discussed each photo-sharing excerpt in data session style discussions examining with a more micro analysis of how the patient or clinician’s responses built upon, resisted, encouraged, or acknowledged the other. Similar to Mischler’s (1984) choosing based on impression that some interviews were atypical, the team agreed on the extremes, namely that one visit in particular seemed to stand out for being conversationally smoother, more attentive/participatory, and leading to behavior change goals; similarly, one visit seemed to stand out as being conversationally stilted, ending with mostly clinician talk and very little patient response. We examined each of the 13 cases for moments of patient expressions of VOL, clinician (in)attention to VOL, and subsequent actions resulting from the photo-sharing. In addition to presenting the two extreme cases, both in English, we also present a case that demonstrated a middle-ground and occurs with a Spanish-speaking patient using an interpreter, providing analytic contrast to the English-only visits.

In these examples (which will be presented as three cases in this paper) we present a conceptual model that presents the influences, pressures, and opportunities for discussing and attending to photos within the primary care visit. By presenting each case in full, we demonstrate how participants moved interactionally through the photos-based communication within the larger primary care visit.

Results

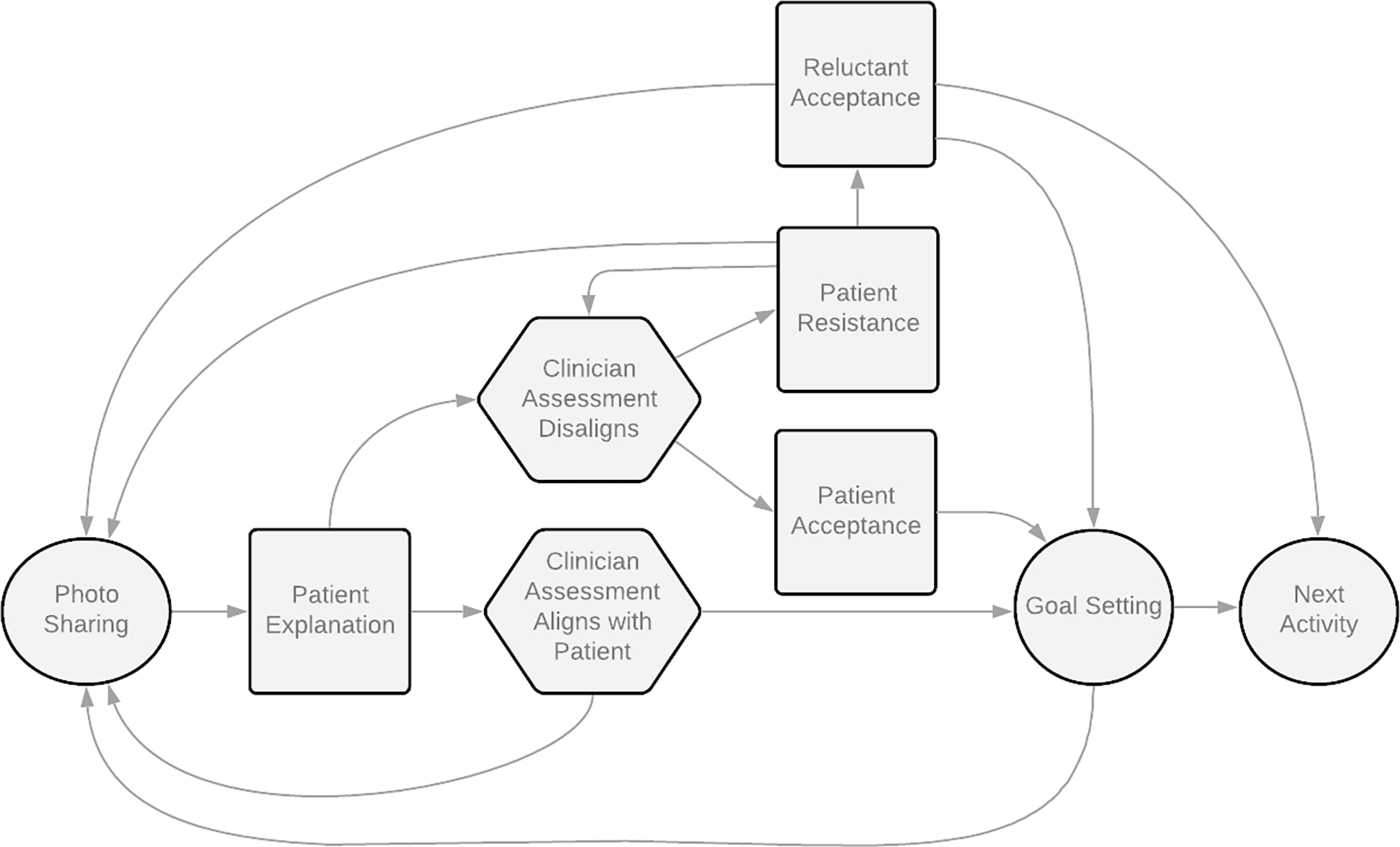

A photo-based interaction which leads to setting patient-centered goals related to diet and nutrition occurred when clinicians attended to patients’ photo(s) and patient assessment of their foods (see Figure 1). Photo sharing occurred in a number of moments including at the very beginning of visits, as part of diagnosis, or within discussion of treatments (Ho, et al., 2021). After the patients either initiated and began showing the photos or clinicians invited them to show photos, this created a sanctioned moment for both clinician and patient to attend to and talk within a VOL frame. Typically, the patient would give a story explaining what their picture was showing (e.g., “This is what the food bank delivers” “I bought this,” “This pizza [is from] my granddaughter’s birthday,” in “Patient Explanation” square in Figure 1). Clinicians verbally acknowledged each photo shared, sometimes aligning with the patient’s story and other times disaligning with patient explanations. Some conversations occurred with clinicians commenting after each individual photo, while other conversations went through all the photos first with clinicians’ substantive comments at the end.

Figure 1.

A Conceptual Model of Interactional Pathways of Photo-Sharing Conversations

This conceptual model depicts the interactional pathways from the initiation of the photo sharing activity to the next medical activity, with patients and clinicians advancing throughout a series of phases. After patient presentation of photo and explanation of foods which comes from the voice of lifeworld, the clinician can either align or disalign with their assessment of the foods (typically as either healthy or unhealthy). Disalignment led to patient resistance when clinicians offered little recognition of the patient’s lifeworld and kept conversations in the voice of medicine. Interactions that centered the voice of lifeworld used photo(s), patient explanations, and patient assessment of their foods to set patient-centered diet and nutrition goals.

Hexagons = Clinician actions

Squares = Patient actions

Circle = Shared actions/activity

Clinicians and patients both treated the activity as one in which patients’ lifeworld choices should be assessed as medically healthy or unhealthy by the clinician. Although patients sometimes disagreed with clinician assessments and held up the progressivity of the visit, the fact that clinicians should assess the patient’s diet demonstrates the underlying dominance of VOM as an expectation of clinical conversations. Every photo-sharing interaction eventually ended by moving to the next activity (e.g., physical exam, next health issue, end of visit, “Next Activity” circle in Figure 1), but some conversations moved more smoothly than others.

Photo-sharing, framed as an activity promoting VOL-talk, can be difficult for clinicians, who may be expected or want to immediately offer a medical assessment of the healthy or unhealthy qualities of the patient’s food choices (in the “Clinician Assessment” hexagons in Figure 1). As an objective piece of “evidence” of the patient’s nutrition, the clinician could assess the nature of the foods in the picture by either praising the patient for healthy eating or through asking questions about unhealthy choices and possibly providing nutritional information. Clinicians also had to deal with whether to address each individual photo as an eating behavior worth addressing or wait to address overall eating habits. Interactions that seemed to benefit from the photo-sharing were ones in which the clinician acknowledged and attended to VOL in two ways: through alignment or a specific form of disalignment. First, “Clinician Alignment” occurred when patients presented their photos and their healthy behaviors which clinicians assessed similarly as “healthy,” or when patients presented photos and explained that they were special occasions or other things to improve, and clinicians agreed it was something to work on. Second, clinicians could attend to VOL even through disalignment. Disalignment occurred typically when clinicians assessed patient behavior as ‘unhealthy’ when patients presented it as ‘healthy.’ Clinicians who framed their assessments of patient behavior by solely presenting new nutrition information (e.g., that has a lot of sugar) within VOM often led to “Patient Resistance.” On the other hand, when clinicians were able to frame their disalignments by fitting into the patient’s narrative/story (VOL) such as reminding patients of previously established goals (e.g., wanting to lose weight), patients more readily accepted this information as something they would work on or change even if this ultimately used the patient photos as an object for VOM-based treatment suggestions. This is conceptualized as the movement from “Clinician Assessment Disaligns” to “Patient Acceptance” and then to “Goal Setting” in Figure 1, to help their ongoing chronic conditions.

While some interactions were able to move through goal-setting and on to the next activity, some photo-sharing interactions became hung up and did not reach goal-setting. In only one case, the clinician’s disalignment was met with “Patient Resistance.” The difference in this case (and conceptual pathway) seemed to be based on the clinician’s almost complete inattention to VOL and continued efforts to solely frame the photo-sharing exercise as VOM. In Case Three, when the patient disagreed with the clinician’s assessment of the photos, the patient asserted their agency in disallowing the progressivity of the visit, which has also been seen in other clinician-patient encounters (Koenig, 2011). This resistance to the clinician’s assessment that the patient was making unhealthy choices took place over multiple rounds, ultimately culminating in the patient reluctantly accepting the clinician’s suggestion to move to the next activity (Figure 1‘s “Reluctant Acceptance”), bypassing goal setting. In the next sections, we present an analysis of three cases that showcase the different influences, pressures, and opportunities afforded by photo sharing and the interactional paths taken during this novel conversational moment.

Case One: “The Only Thing to be Mindful About… Top Ramen”

In Case One, a 76-year-old year old male patient, Jack, and Dr. C (45–50 year-old female) had a 22-minute conversation lasting over half the length of the whole visit. This interaction resulted in a positive exchange in which the patient presents eating practices situated within his lifeworld and the clinician explicitly attends to the VOL talk by not only asking pointed questions about possible structural vulnerabilities related to food and housing insecurity but also allowing the patient room to talk about eating preferences and tastes. Dr. C and Jack go through various iterations of the first three steps of the conceptual model: Photo Sharing, Patient Explanation, Clinician Assessment Aligns with Patient (Figure 1). The conversation is characterized by casual and light-hearted banter and easy laughter. Dr. C uses the entire course of the exchange to praise Jack and only after discussing all the pictures, raises one suggestion about an area of dietary improvement (an example of Clinician Assessment Disaligns by presenting it through VOL). After Patient Acceptance, the conversation can move to shared Goal Setting and then Next Activity.

The clinician began the photo-based portion of the visit by thanking the patient for doing “this project” and then asking him what his understanding is of the project (see Table 1, Excerpt 1). By asking about Jack’s understanding, Dr. C marks this time as being different from the previous talk, which was closing a conversation about his defibrillator. Jack’s answer about eating habits provides an opportunity for Dr. C to connect the previous talk about medication and defibrillators to the current purpose of the photos-based talk by saying, “keeping you healthy… has to start with the food and the exercise” (line 9–10). In this way, Dr. C frames the talk as a “regular” part of the visit that, like other parts of the visit, includes Jack sharing his experience and the doctor providing an assessment, a move towards centering the VOM.

Table 1.

Case 1 Jack (76-year old male), Dr. C (45–50-year old female)

| Transcript Excerpts | ||

|

| ||

| Excerpt 1 | ||

| 1 | Dr. C: | So tell me. I appreciate your taking the time to do. To do this project [as well. |

| 2 | ||

| 3 | J: | [uh huh Yeah. |

| 4 | Dr. C: | Tell me what your understanding was of the project and then I’d love to see what you’re able to share with me. |

| 5 | ||

| 6 | J: | [This is ah this is about [eating habits. |

| 7 | Dr. C: | [Yes. [yes |

| 8 | J: | This is a-we get once a- |

| 9 | Dr. C: | You and I, we talk about it, keeping you healthy it has to start with the food and the exercise all the medications and defibrillators= |

| 10 | ||

| 11 | ||

| 12 | J: | =Right= |

| 13 | Dr. C: | =in the world don’t take the place of those. |

| 14 | J: | That’s right this is a food bank delivers food to the building every week. |

| 15 | ||

| 16 | Dr. C: | Wonderful |

|

| ||

| Excerpt 2 | ||

| 26 | Dr. C: | And then how do you get to decide? Is it usually ample for you to get the choices of what you wan[t? or is it- |

| 27 | ||

| 28 | Jack: | [Yeah. Mm-hmm |

| 29 | Dr. C: | Or is it limited? |

| 30 | J: | They give me uh () I get first choice [because- |

| 31 | Dr. C: | [That’s |

| 32 | the way it should be. | |

| 33 | J: | I’m a good friends. |

| 34 | Dr. C: | Oh, that’s even better. What’s your favorite out of all of those? |

| 35 | J: | Oh? Everything. Cause I like to cook. and I don’t have a real kitchen but I’ve got a I’ve got ah one of those. (1.0) things that. you have to put the plate on it and then |

| 36 | ||

| 37 | ||

| 38 | [it heats up | |

| 39 | Dr. C: | [Mm hmm |

| 40 | J: | I got one of those. And I’ve got a blender, and I’ve got different things. to cook with so= |

| 41 | ||

| 42 | Dr. C: | =Wonderful= |

| 43 | J: | =We don’t have a stove or anything. |

| 44 | Dr. C: | Mm hmm mm hmm |

|

| ||

| Excerpt 3 | ||

| 98 | Jack: | Yeah. And then this one is ah. stuff we. mm that I buy like Top Ramen which I lo:ve, |

| 99 | ||

| 100 | Dr. C: | mm hmm |

| 101 | J: | and ah different things an th then the fruit is from Meals on Wheels. |

| 102 | Dr. C: | Very good. |

| 103 | J: | And the [eggs. |

| 104 | Dr. C: | [And the eggs are excellent protein for you. |

| 105 | J: | And That’s about [it. |

| 106 | Dr. C: | [Chicken teriyaki. |

| 107 | J: | Yeah |

| 108 | Dr. C: | with sauce. How does how do the Meals on Wheels taste for you? |

| 109 | J: | g-Good. |

|

| ||

| Excerpt 4 | ||

| 227 | Dr. C: | Good. Cause the only thing to be mindful about is that I know you mentioned Top Ramen was a favorite. |

| 228 | ||

| 229 | Jack: | I love that. |

| 230 | Dr. C: | to just be a little careful of the salt. |

| 231 | [that’s in there with the seasoning packet. | |

| 232 | J: | [oh yeah Oh really? |

| 233 | Dr. C: | yeah That’s the one that can often affect your blood pressure and your kidneys the most. |

| 234 | ||

| 235 | J: | Oh really I did a blood pressure test |

| 236 | [for you. Did you get it? | |

| 237 | Dr. C: | [yeah Your sodium is, of course, |

| 238 | different than. the ... For you, sometimes it’s been too low ((typing)) right? Let me just look. at what that blood test looked like. | |

| 239 | ||

| 240 | ((some mouse clicking)) | |

| [20 lines removed discussing blood pressure and other “low” or “good” tests] | ||

| 261 | Dr. C. | and that also looks good. |

| 262 | J: | Well that’s good because I eat a lot of those. Th-. Top Ramen things. |

| 263 | Dr. C: | Yeah. Ha ha .hhhh. Well try, maybe, to put some of the fresh vegetables |

| 264 | into them when you’re cooking them. | |

| 265 | J: | right right |

| 266 | Dr. C: | Often, as you as you prepare the Top Ramen, to start by m maybe using you know how they have the flavor packet [by itself, to use a little bit less. |

| 267 | ||

| 268 | J: | [right but I use tha I use the cup of noodles. |

| 269 | Dr. C: | Oh okay. |

| 270 | J: | The cup of noodles. |

| 271 | Dr. C: | That has the flavor packet already in it. |

| 272 | J: | Yes. |

| 273 | Dr. C: | Yeah. |

| 274 | J: | But I can add stuff to it if I want? to I guess. |

| 275 | Dr. C: | Yeah, to add stuff to it or sometimes I’ve seen people maybe put that on your hot plate and to put it with extra. water and extra fresh vegetables |

| 276 | J: | Right |

| 277 | Dr. C: | and then that water and the vegetables will make extra bro^th and will really dilute out a lot of the salt that comes with the packet. |

| 278 | ||

| 279 | J: | Yeah. |

| 280 | Dr. C: | Do you follow [what I’m saying? |

| 281 | J: | [Um hmm. Yeah. |

| 282 | Dr. C: | That’s another choice. But it looks like you’re making very healthy choices |

| 283 | ||

As Jack talked through the various pictures and voicing his lifeworld into being, Dr. C was audibly positive, aligning her assessment with Jack’s and vocalizing her approval with repeated statements of “wonderful,” and other positive encouragers. After seeing many of the fruits and vegetables, she asked in lines 26–27 if Jack had choices in what he eats. In the overlap in lines 27–28, Dr. C’s addition of “or is it limited” demonstrates that underlying the question about taste was also a question about Jack’s access to foods. Her response in lines 31–32 not only implies that he should or deserves to have a choice in the foods that he eats but also perhaps that he should have first choice. Talk centering the VOL continues with their discussion of how Jack cooks and what he lacks (a stove). Throughout the visit, Dr. C assesses Jack’s actions as assets (e.g., creatively using the blender) in creating his daily smoothies. She approves of this action giving Jack ample praise, repeating “good for you” (line 85) as they continue the conversation (Table 1, Excerpt 2).

As the conversation progresses, Jack presents other pictures of foods to which Dr. C responds positively, following the same path on the conceptual model as the previous photos. It is not until line 98 when Jack shows a picture of Top Ramen (Table 1, Excerpt 3). In this part of the conversation, Jack seems to have finished sharing his pictures and is waiting for Dr. C’s response, which he signals in line 106 with “that’s about it.” In the transitional moment in line 108–109, again Dr. C uses the opportunity to ask about taste and his housing situation. Afterwards, Dr. C, positively assesses Jack’s eating and drinking and thanks him (line 197).

The first moment Dr. C begins to bring in any nutritional advice starts in 227 in discussing the Top Ramen that was first raised in line 98. Notably, it is only after numerous positive assessments by Dr. C that she then talks about something to be “mindful about” (Table 1, Excerpt 4), possibly an acknowledgement that Dr. C begins to disalign with the patient and moving the conversation into VOM. Jack’s “Oh really?” (line 232), as an information management marker (Schiffrin, 1987), could be heard as a genuine expression of surprise as well as disagreement (or Patient Resistance) both about the amount of sodium in Top Ramen and the danger of that level of intake. As the conversation unfolds, it becomes clear that Jack did not think sodium was an issue for him since all the blood tests were fine. In the lines removed, Dr. C and Jack go back and forth while there are a lot of typing noises in the background with Dr. C announcing test after test that they are all in the low or good range. Dr. C then uses a harm reduction approach by stating that Jack could use less of the flavor packet (line 269). However, since it is Cup ‘o Noodles and not Top Ramen, there is no flavor packet. Notably, it is Jack that, by attending to Dr. C’s nutrition lesson, offered the solution of “adding stuff to it” (line 277) Jack demonstrates a form of Patient Acceptance to concerns about sodium. In line 279, Dr. C confirms that she has “seen people” do this to “make extra broth” and “dilute out a lot of the salt,” attending to the VOL concerns presented and recognizing how people actually eat. Dr. C confirms Jack’s understanding in line 281 and then wraps up the conversation as a useful blending of VOL and VOM, with a shared new goal of diluting the salt and adding vegetables.

Case Two: “You Went to BURGER KING?… to Celebrate That the Belly Pain Was Gone?”

In Case Two, Roberto, a Spanish-speaking, 73-year-old, male patient is discussing his photos with Dr. G (<35-yo female) through an interpreter. During this interaction there were numerous moments of laughter from both sides and Roberto is able to voice his lifeworld at the same time Dr. G is able to assess and teach certain nutrition information which leads to patient learning and new goals. There were moments of both VOM/VOL as clinician and patient moved through cycles of photo-sharing, not always aligning in their assessments. As an interpreted conversation requiring shorter phrases and interruptions of points, the talk between clinician and patient was not interactionally as smooth as in Case One, however, participants still moved from Photo Sharing, Patient Explanation, Clinician Assessment Disaligns, and Patient Resistance and eventually Acceptance, and Goal Setting. Unlike Case One, the interactional pathway of disalignment, resistance, acceptance, and goal-setting occurs after each photo.

In the first excerpt of Table 2, Dr. G opens the photo-sharing by inviting Roberto to show his photos. The food presented in Roberto’s photo is very clearly assessed as “too much,” based on Dr. G’s emphatic and leading question (line 7). The preferred answer would be that Roberto is not eating all of this himself, but he responds quickly and affirmatively (line 8) even before the translator has a chance to translate Dr. G’s question. The translation, which occurs in line 9, is not actually as emphatic; instead it only asks a factual question “is this what you’re eating?” but could be heard as a kind of Clinician Disalignment. Roberto’s response, by explicitly beginning with “tell her that…” in line 11, positions the interpreter as not only translating the words, but also, transmitting his defense or Patient Resistance. Roberto’s explanation of his choices can be understood as attempting to center his presentation of VOL, explaining that his food is coming from a source (elderly free lunch program) that he has little control over. The fact that the rice is in every photo and that Roberto does not even notice its presence until Dr. G’s mention demonstrates the utility of the photo-sharing practice not just for clinicians’ awareness but for patients as well. Again in lines 14 and 17, Dr. G’s disaligned assessment of the rice is very clear: from the VOM, it is too much and she’s surprised that Roberto thinks the food shown in the pictures are acceptable for someone with diabetes. Roberto’s repeated resistance to this assessment are attempts to voice into being his lifeworld, but they are not accepted until line 20 when Dr. G. acknowledges that he is not choosing the rice, but rather it is served by the program. This subtle attentiveness to VOL then allows her to also shift from expressions of surprise and negative assessment to education about rice and its effect on blood sugar for people with diabetes - arguably another move to center the VOM, however different from the previous assessments. This tactic (teaching) seems to have worked better because Roberto is able to acknowledge and accept the clinician’s assessment and new information (line 27, Patient Acceptance). In response, Dr. G demonstrates further clinician attention to VOL by acknowledging Roberto’s constraints and stating that he does not have to cut out rice completely but rather, should eat less, moving through the first instance of Goal Setting (line 31), which Roberto accepts as a goal to strive for (line 34).

Table 2.

Case 2 Roberto (73-year old male), Dr. G (<35-year old female), with Spanish Interpreter

| Transcript Excerpts | ||

| 1 | Dr. G: | Okay. Do you want to show me the um, pictures? |

| 2 | Translator: | Desea mostrarme esas imágenes, las fotos? |

| Would you like to show me these images, these photos? | ||

| 3 | Roberto: | A, claro que sí. |

| Sure of course | ||

| 4 | Tr: | Sure, of course. |

| 5 | (39) ((doctor types on keyboard)) | |

| 6 | R: | ((low voice)) aquí están todas, pues ya |

| 7 | Dr. G: | Oh WO::w. Is this what you’re EATING!? |

| 8 | R: | u::h yah |

| 9 | Tr: | eso es lo que está comiendo? |

| Is this what you’re eating? | ||

| 10 | R: | Dile que ese es, yo voy con los viejitos a comer, y esa es la la comida que nos dan cada, diario, de lunes a sábado, a la doce. |

| 11 | ||

| Tell her that that is it, I go with the elderly to eat, and that is the food that they give us every, everyday, from Monday to Saturday, at twelve. | ||

| 12 | Tr: | Yeah, I go to eat with all the elderly people. And that’s the food that they serve us every day. From Monday to Saturday at 12. |

| 13 | ||

| 14 | Dr. G: | That is SO much rice ((slight laughter)) |

| 15 | Tr: | Eso es bastante arroz |

| That is quite a lot of rice | ||

| 16 | R: | ((laughter)) Los dan free, y yeah entonces, allá hay mucho, yeah |

| They give it for free, and yeah so, there is a lot there, yeah | ||

| 17 | Dr. G: | WO::W (2) is this rice too? Oh my gosh. |

| 18 | Tr: | ¿Eso también es arroz? |

| That, too, is rice? | ||

| 19 | R: | Yeah, si, es arroz, yeah |

| Yeah, yes, that is rice, yeah | ||

| 20 | R: | Siempre nos dan de arroz, (), algo de arroz en cada comida, yea |

| They always give us rice, (), some portion of rice each meal, yea | ||

| 21 | Tr: | They always give us a lot of rice with each meal. |

| 22 | Dr. G: | Okay but here’s the thing, we go to be CAREful about the rice. Cause it can raise our sugar and make your diabetes worse. |

| 23 | ||

| 24 | Tr: | Eh perdona, la cosa con el arroz es que hay que tener cuidado porque |

| 25 | puede hacer que suba el azúcar en la sangre y eso puede elevar a la diabetes | |

| 26 | ||

| Oh pardon, the thing about rice is that one must be careful because it can cause the sugar to rise in the blood and that can raise the diabetes | ||

| 27 | R: | Pues hasta ahorita estoy sabiendo, ya, ya no me voy a comer, que bueno, no |

| 28 | ||

| Well, I am just now realizing, ya, ya I will no longer eat, fine, no | ||

| 29 | Tr: | Uh knowing that I won’t eat that anymore= |

| 30 | R: | =Yah |

| 31 | Dr. G: | Well you don’t have to comPLEtely cut it out, just less. |

| 32 | Tr: | Si, no tiene que dejar de comer eso por completo, pero tiene que comer menos |

| 33 | ||

| Yes, you do not have to cease eating that entirely, but you have to eat less | ||

| 34 | R: | =yah yah yah yah, ey, gracias, esta bien, perfecto |

| yah yah yah yah, ey, thank you, that is fine, perfect | ||

| 35 | Tr: | Er, thank you |

|

| ||

| Excerpt 2 | ||

| 185 | Tr: | Because I had the stomach discomfort, that’s rice. ((Dr. G. coughs)) |

| 186 | And this is water for my stomach discomfort. | |

| 187 | Dr. G: | Okay. Did it help?= |

| 188 | R: | =Yah |

| 189 | Tr: | y eso, ¿le ayudó? |

| and that, did it help you? | ||

| 190 | R: | Sí (2), y eso, puro Burger King (1) |

| Yes, and that, only Burger King | ||

| 191 | Dr. G: | You went to BURger KING? ((Roberto laughs)) Is that to celebrate that the belly pain was gone? (1) |

| 192 | ||

| 193 | Tr: | Y fue para celebrar que se le fue el dolor de barriga .hhhh |

| And you went to celebrate that your stomach ache had gone away | ||

| 194 | R: | Es malo el Burger King? |

| Burger king is bad? | ||

| 195 | Tr: | Eh, hh is this bad to eat Burger King? |

| 196 | Dr. G: | I MEAN it has a LO:T of carbohydrates which is not good for the diabetes. |

| 197 | ||

| 198 | Tr: | O sea, tiene bastantes carbohidratos, lo cual no es bueno para la |

| 199 | diabetes | |

| That is to say, it has many carbohydrates, which is not good for diabetes | ||

| 200 | R: | ¿No verdad? Sí es cierto y casi, pinche voy diario casi a Burger |

| 201 | King, malo, al almuerzo, al almuerzo | |

| No, right? That is true and almost, fuck, I go almost everyday to Burger King, bad, to lunch, to lunch | ||

| 202 | Tr: | ((false starts)) I go there almost everyday to Burger King, so it isn’t good, right? |

| 203 | ||

| 204 | Dr. G: | ((laughs)) you go to Burger King EVery DAY hh? |

| 205 | R: | No, cada |

| No, every | ||

| 206 | Tr: | Va a Burger King todos los dias? |

| You go to Burger King everyday? | ||

| 207 | R: | No, no, cada tercer dia, porque tengo cupones |

| No, no, every third day, because I have coupons | ||

| 208 | Tr: | No, it’s every three days because I have coupons. ((Dr. G laughs)) |

| 209 | R: | yo tengo, sí, yeah, pero si me hacen daño ya no voy a comer |

| I have, yes, yeah, but if it harms me I will no longer eat | ||

| 210 | Tr: | But if it’s bad for me, then I won’t anymore. |

| 211 | (2) ((Dr. G typing on keyboard)) | |

| 212 | R: | Este es el que agarro (2) |

| This is the one I get | ||

| 213 | Tr: | That’s what I [have (1) |

| 214 | Dr. G: | [yeah this is GOOD! This is a CROIssanT and |

| 215 | R: | Ey pan croissant, ese es el que más como, ése, ése |

| Ey, croissant bread, that is the one I most eat, that one, that one | ||

| 216 | Dr. G: | EGGS. [This is GOOD! |

| 217 | R: | [como ese [agarro cupones |

| I eat that one, I get coupons | ||

| 218 | Tr: | [That’s what I eat the most. |

| 219 | Dr. G: | [((laughs))= |

| 220 | R: | =((laughs)) |

| 221 | Tr: | Sí, eso es bueno, es un croissant con huevos |

| Yes, that one is good, it is a croissant with eggs | ||

| 222 | Dr. G: | HH that’s amazing. I would say I’m okay with THESE every three days. I’m NOT okay with the frIES and potatoes every three days. |

| 223 | ||

| 224 | That’s too! Much. | |

| 225 | Tr: | Sí bueno, diría que eso está bien que coma cada tres días, pero no |

| 226 | me parece bien que coma frituras ó papas uhh todas los días, eso | |

| 227 | no es bueno | |

| Yes well, I would say that is okay to eat every three days, but it does not seem okay to me that you eat fried foods and potatoes everyday, that is not good | ||

| 228 | ((doctor types while Tr is talking)) | |

| 229 | R: | Ok ey gracias ya no más |

| Ok, ey, thank you, no more | ||

| 230 | Tr: | Thank you. |

| 231 | Dr. G: | It’s okAY you can GO! but maybe once a week. |

| 232 | Tr: | Eh puede ir pero quizás una vez a la semana |

| Eh you can go, but maybe once per week | ||

| 233 | R: | Ok bien gracias |

| Ok, good, thank you | ||

| 234 | Dr. G: | Just maybe a li::ttle bit less Burger King. |

| 235 | Tr: | Quizás un poco menos de Burger King |

| 236 | R: | Ok, ey, gracias, eso es lo que voy a hacer ya, una, una vez por semana y ya |

| 237 | ||

| Ok, ey, thank you, that is what I will do, once, once per week and that is it | ||

| 238 | Tr: | Yeah once a week and that’s it. |

| 239 | Dr. G: | Good. Can I feel your belly? |

A very similar pattern occurs as Roberto shows multiple pictures of coffee. Each of the photos are again greeted with a tone of incredulity (“Man! More coffee!” “you’re going to have more energy than anyone if you keep drinking this much coffee”), which makes very clear that the clinician’s assessment of this behavior does not align with Roberto’s neutral presentation. However, after Roberto shares some additional information about his willingness to learn/change (e.g., he likes coffee but is willing to cut back if it’s “harmful for [him].”) Dr. G educates Roberto through emphasizing that caffeine is “heavy on the heart” (VOM) but also recognizing the VOL and recommending reducing rather than giving up coffee altogether. Again, Roberto agrees to this second photo-specific goal-setting.

In the final section of the photo-sharing, Roberto presents a picture of a rice porridge because his stomach was not feeling well, followed very closely by a picture of a Burger King meal (Table 2, Excerpt 2). Similar to the previous two examples, Dr. G again makes a joke about the inappropriate meal choices, this time facetiously asking if the Burger King is to celebrate the end of Roberto’s stomach pain (line 191). Roberto’s laughter in line 191 comes even before the translator is able to translate. Similarly to the first example, it’s clear either in the content or in the way Dr. G states her emphatic surprise that there’s something funny about her question. When the interpreter diligently translates the literal words of the joke (line 193), which sound like a legitimate question, Roberto responds in a way that shows that he understands and accepts Dr. G’s disaligned assessment of his photos (line 194). Like the other two examples, Roberto is concerned about whether his choices are unhealthy (line 194) and after a few rounds between Dr. G and Roberto about his financial constraints (he collects Burger King coupons - lines 207, 212, 217), Dr. G is able to teach Roberto what is “unhealthy” about Burger King in a way that aligns with and centers VOL. Again, Dr. G uses the strategy of harm reduction to emphasize eating eggs at Burger King instead of fries and potatoes, and/or going once a week instead of multiple times. Similar to previous rounds, an individual photo shared leads to Clinician Disalignment, Patient Resistance, Patient Acceptance (after clinician acknowledges VOL), and (photo-specific) Goal Setting.

Additionally, one important point in this exchange happens in line 200 when Roberto, upon learning that Burger King foods have too many carbohydrates, admits to eating it almost every day and wonders aloud how bad this would be. Dr. G’s response in 204 incredulously asks whether it’s true that he goes “EVery? DAY?” Again, the intonation must have given Roberto enough frame of reference to recognize that such behavior is not healthy because he then emphasizes “not every” day (line 205) and then retreats to “every three days” (line 207). Previous research on clinician-patient communication regarding alcohol and tobacco use (typically accepted “bad behavior”) has found that patients often use less specific terminology in an effort to avoid negative judgment by the clinician (Halkowski, 2012). What’s interesting here is that Roberto begins to do this in saying “not every day” but actually retreats to a very specific number (every three days). What could have been seen as disclosing a troubling dietary practice actually allows Roberto to accept the clinician’s negative assessment while also voicing his lifeworld into being and accounting for his actions via the coupons he collects. The clinician’s responses while taking into account these lifeworld considerations also pushes a VOM interpretation of the actions and moves the conversation to various small goals and then the next activity of a physical exam. It is worth noting that Roberto pushes back not against the clinician’s VOM assessments, but rather, whether he can realistically make these changes given his constraints around food availability.

Case Three: “You Never Know What’s in There Cause You Didn’t Make It, Right?”

Similar to Case Two, in this final example we also see the patient seeking clinician alignment and approval of the pictures shown, essentially casting the photo-sharing exercise into a VOM-dominant interaction space. However, unlike Case Two, there is little clinician attention to VOL and the patient repeatedly disagrees and disaligns with the clinician’s assessments. Moreover, some parts of the conversation are hearably uncomfortable for both doctor and patient. We highlight this case not to fault any individual but rather to demonstrate how the clinician’s insistence on operating within a VOM without attention to VOL disallows the two sides from coming to an agreement and further progression of the visit. After many rounds of Dr. B disaligning with and Winnie resisting Dr. B’s assessment of the foods pictured, it is ultimately the patient’s Reluctant Acceptance of Dr. B’s suggestion of the food diary that allows for the visit to progress to the Next Activity, a physical examination. Unlike the other two cases, this photo sharing interaction does not go through the pathway of goal setting.

In this visit with Winnie (68 yo female) and Dr. B (female <35yo), Winnie begins the photo-based interaction by stating that she “keeps gaining and gaining,” aligning her pitures with her weight. Winnie shows pictures of the various foods that she is eating, which she presents as healthy choices. To begin the interaction, Winnie introduced her first picture of a Chinese chicken salad (Table 3, Excerpt 1). After the initial picture, Dr. B immediately questions those choices about whether the food is made or bought (line 23) and whether there are starches (lines 26–28). Both questions hearably move the conversation into the VOM, with Dr. B interrupting the conversational flow to gather information to measure the nutritional harm of these foods. Winnie’s reactions can be read as justifications or accounts (explanations urging the VOL). When Winnie further attempts to justify her healthy eating choices by saying the salad includes almonds and “nothing can go wrong with that, you know” (line 32), her justification invites Dr. B’s approval. However, the doctor disaligns with, “Well, it depends on the dressing because you didn’t make it” (lines 33–34). In line 35, Winnie’s “a:hh yeah” can be seen as a way of acknowledging that the “bought” dressing is not healthy. However, immediately after, Winnie presents a picture of something - the salmon - as a “healthy” choice. The quick shift to the topic of salmon and healthy eating may actually show the a:hh yeah to be continued resistance rather than patient acceptance. When Dr. B says “good” in line 36, Winnie’s question can be heard as requesting Dr. B to repeat her assessment and align with her presentation of salmon as good. Unlike the previous example of the chicken salad, this photo sharing leads to clinician alignment with the patient explanation and like Case One then leads to the next photo.

Table 3.

Case 2 Winnie (68 yo female), Dr. B (female <35yo)

| Transcript Excerpts | ||

|

| ||

| Excerpt 1 | ||

| 19 | Winnie: | No, but I haven’t had a big big fall like the other ones. (4) ((doctor types on computer)) I don’t know. Uh I’ve been trying to I’m I’m trying the Chinese salad. You know, that is just shredded uh lettuce with uh chicken. |

| 20 | ||

| 21 | ||

| 22 | ||

| 23 | Dr. B: | And you make this, or do you buy it? |

| 24 | W: | No, I bought it. At home first. |

| 25 | Dr. B: | So, looks like there’s lettuce in there. There’s chicken in there. Is there rice? |

| 26 | ||

| 27 | W: | No. |

| 28 | Dr. B: | Noodles? |

| 29 | W: | No. |

| 30 | Dr. B: | Okay good. That’s pretty good. |

| 31 | W: | Just a few almonds. You know. Almonds. I mean, you know, so nothing can go wrong with that. You know?= |

| 32 | ||

| 33 | Dr. B: | =Well, depending on what’s in the dressing. You never know what’s in there cause you didn’t make it right? |

| 34 | ||

| 35 | W: | A::h yeah, yeah. Then (3) uh well a little piece of salmon. |

| 36 | Dr. B: | Good. |

| 37 | W: | Is that good? |

| 38 | Dr. B: | Salmon’s good. |

| 39 | W: | Oh good. (2) And then I’m taking One-A-Day, like I buy these things, you know, for energy and protein and= |

| 40 | ||

| 41 | Dr. B: | =Let’s see: that, I bet, has a lot of sugar in it. |

| 42 | W: | Oh yeah. This one was a little treat. You know= |

| 43 | Dr. B: | =Ok, probably a big treat. |

| 44 | W: | I know. But you know, what I’m doing is I’m liquefying um uh (2) xx Spinach? With orange juice. |

| 45 | ||

| 46 | Dr. B: | Now, orange juice has a LOT of sugar in it. I would not use that. |

| 47 | I would cut that out. | |

|

| ||

| Excerpt 2 | ||

| 107 | Winnie: | And another thing that I wanted to ask you that I like, and I mean, it’s light. I LOVE sushi. (5) I go to (2) Safeway and it’s my sushi here. (1) |

| 108 | ||

| 109 | ||

| 110 | Dr. B: | Okay. So you know rice is bad for diabetes. |

| 111 | W: | (1) Mm ((whimper)) But the little sushi. And it’s like this is my whole day meal. |

| 112 | ||

| 113 | Dr. B: | That’s ALL you eat all day? I would say, do you ever try the nigiri? which is fish only? with no rice? |

| 114 | ||

| 115 | W: | The nigiri? Oh. |

| 116 | Dr. B: | Yeah! That’s usually fish only with no ri:ce. |

| 117 | W: | Okay. |

| 118 | Dr. B: | So that would be better for someone with diabetes. Um but your diabetes has been GOOD. So it sounds like weight gain is mostly the thing that you’re worried about. |

| 119 | ||

| 120 | ||

| 121 | W: | Yeah. And I know it was Christmas time and I, you know, Christmas time. I’m not going to put nothing down. I eat it all up. ((typing)) |

| 122 | ||

|

| ||

| Excerpt 3 | ||

| 193 | Winnie: | I don’t eat. I have my coffee in the morning. I was having those shakes, those smoothies that I was making? |

| 194 | ||

| 195 | Dr. B: | Okay, so the smoothies are a PROblem. They have a lot of sugar in them. That could be one reason you’re gaining weight. It looks like you’re also taking some protein shakes. which I don’t think you need. Those have lots of calories in them. (1) |

| 196 | ||

| 197 | ||

| 198 | ||

| 199 | W: | Mmm yeah. And the energy shake? Because I need energy. |

| 200 | Dr. B: | Well. Energy shakes usually have caffeine and sugar in them, so those are probably pretty ba:d for you. |

| 201 | ||

| 202 | W: | Lattes? |

| 203 | Dr. B: | Lettuce is good. ((laughs)) |

| 204 | W: | No, latte, latte. |

| 205 | Dr. B: | Latte. |

| 206 | W: | Café latte. |

| 207 | Dr. B: | Do you put sugar in it? |

| 208 | W: | No. |

| 209 | Dr. B: | That’s fine with me. |

|

| ||

| Excerpt 4 | ||

| 275 | Dr. B: | Okay. Well, I think we need to keep a food diary of A::bsolutely everything you eat= |

| 276 | ||

| 277 | W: | =Everything= |

| 278 | Dr. B: | =Every single thing you eat for a couple weeks and bring that back in |

| 279 | the next time you come in. Okay? Um you can do it with pictures, if you wa::nt. You can do it writing down. But every single thing you eat. | |

| 280 | ||

| 281 | ||

| 282 | W: | I will eat sushi every day! ((laughs)) |

| 283 | Dr. B: | Okay. So you need to know how MUch. |

Winnie next shows a photo of a prepackaged shake, which she characterizes as healthy because it provides energy and protein (line 40). Centering the VOL, one might wonder about Winnie’s needs for energy and protein. However, asserting the VOM, Dr. B’s disaligned assessment is that the drink is unhealthy because it likely has a lot of sugar, to which Winnie resists by calling it “a little treat” (line 42). Dr. B’s upgraded assessment to “big treat” (line 43) makes very clear that this is an unhealthy choice and that energy and protein needs that Winnie presents are actually irrelevant. Winnie is then left with only two options: to accept that her shake was a bad choice, or to resist again. While the “I know” in line 44 may sound like acceptance, her smoothie explanation of adding orange juice and spinach can be heard as resistance to the assessment that smoothies/energy drinks are “unhealthy.” Again, Dr. B’s assessment of the choice being unhealthy is explained through an attempt at medical education by explaining that orange juice has a lot of sugar. Dr. B and Winnie are stuck in the conceptual model in Clinician Assessment Disaligns and Patient Resistance which is only solved through sharing another photo.

In the following lines that have not been presented, Winnie continues to locate herself as someone with good eating habits giving examples of the fruits (bananas and berries) and powders she inserts in her smoothies: maca and matcha, which she claims help to give her energy. While Dr. B was able to critique the fruit as being high in sugar, she states she is “not as familiar” with these nutritional supplements and asks for spellings to type into the chart, from what can be heard in the recording. Dr. B acknowledges that both maca and matcha should be fine as long as Winnie does not add sugar to it.

Following this, Dr. B asks if the photos Winnie is showing her is illustrative of her daily eating practices. In asking this, the doctor perpetuates the framing of the photo-sharing exercise as very much a VOM activity where the end goal is to get the doctor’s (dis-)approval of one’s diet. When Dr. B asks if Winnie has a question, the following exchange occurs (Table 3, Excerpt 2). Winnie expresses her love for sushi and asks whether or not eating sushi is acceptable, to which the doctor says that the raw fish is okay, but the rice is not because of her diabetes. As a negative assessment, Winnie is again put in the position where she must either accept that her actions are unhealthy or try to resist. The pause and audible whimper in line 111 demonstrates how difficult this can be for patients in this situation. Winnie resists again by hedging that the sushi is a whole day’s worth of meals (line 112), which Dr. B does not seem to believe and explicitly questions (line 113). Nonetheless, Dr. B’s next set of suggestions begins to demonstrate some VOL acknowledgement in suggesting a different way to each sushi, clearly Winnie’s preferred meal. She suggests Winnie to eat a type of sushi called “nigiri,” which she explains is “sushi with no rice” (line 116) as a healthier replacement for the patient. Notably, nigiri is actually “sushi with rice,” but unlike previous suggestions, this actually attends to VOL.

Line 122 is about 40% into the photo-sharing time. The rest of the time Winnie continues to show more photos, including a spread at Christmastime with the joke that the holidays were an excuse to “eat everything” (line 122). Dr. B continues to negatively assess the foods for being too “white” and carbohydrate-filled (e.g., white bread, noodles). After each negative and disaligned assessment, Winnie uses the same resistance technique of hedging (stating things like “once in a very while,” or “I don’t really eat.”) By using these non-standard temporal metrics, she is able to operate as a responsible patient within the now dominant VOM of the visit by answering clinician questions about the unhealthy nature of these foods. Going against the intended purpose of the photo-sharing - to allow patients space to voice lifeworlds into the clinical interaction - this visit instead shifts into an exercise of Winnie interactionally dodging judgment of potentially negative behaviors through vague caveats accompanying the pictures instead of specifics (Halkowski, 2012).

In the following excerpt, Dr. B upgrades her disalignments about Winnie’s less-than-ideal food choices by focusing her next responses as explicitly causing weight gain, which was Winnie’s original concern (Table 3, Excerpt 3). Winnie’s comment in lines 193–194, to “was having” signals a type of resistance through (revised) patient explanation wherein the patient heard earlier that consuming shakes is not what she should be doing. However, by speaking of these behaviors as a thing of the past, she can distance herself from those now acknowledged wrong-doings. Studies have noted that clinicians’ explicit linking to a patient’s illness in attempting to change behavior can backfire (Albury, 2018), and in the case with Dr. B and Winnie here, we can clearly see why this is the case. Dr. B’s subsequent response raises the critique by stating boldly that the smoothies are a problem (line 195). By engaging in this type of back-and-forth assessment of good versus bad eating behavior, the doctor reinforces the VOM as the correct frame for the conversation and establishes herself as the enforcer of good food choices. Even though Winnie has a “healthy” story behind each picture, she continuously must prove herself to be a reliable reporter of the medically-approved and diabetes-specific aspects of each food item by providing extra information (e.g., no sugar, extra shots of espresso and not sweeteners). Because this cycle seems to have no end, Winnie’s multiple comments of not eating much are a final form of resistance because Dr. B cannot question what she has not eaten. Because the visit needs to progress, Dr. B suggests Winnie to document everything she eats with a food diary (Table 3, Excerpt 4). Through this exchange, we see that while Dr. B finally succeeded in moving the conversation along through suggesting a new diagnostic option (food diary), Winnie still was able to assert agency in disallowing the progressivity of the visit, and it is only through the patient’s own reluctant acceptance of the suggested “goal” (e.g., we can try this food diary option but you will still see the that I only eat sushi) that allowed the visit to move forward to a physical exam.

Discussion

As these three cases demonstrate, photo-sharing in primary care visits with patients with MCC can occur in a number of ways that spotlight the potential utility of VOL sharing within a larger clinical encounter which is framed as a space of VOM. Patients and clinicians can move smoothly through a pathway in which patients share photos and offer explanations, clinicians align (or disalign) with the patient’s presentation, clinicians center VOL talk and offer positive reinforcement or nutrition education which leads to new or renewed goal-setting for the patients. Clinicians’ assessment of photos can disagree with patient assessments, which either requires patients to accept new information or offer resistance in the form of an explanation. In moments of disagreement, when clinicians solely press the VOM in their evaluations of patients’ pictures with little attention to patients’ presentations, it can lead to resistance and difficulty moving to the next activity. This “clash” in the interaction, when repeated over and over again, led to hearable frustration by both parties. Ultimately, the conversation cannot stay on this conflict and the visit must progress. Therefore, the patient either offers reluctant acceptance to set agreed upon goals, or in the one instance of Case Three, the patient states outright that they will not change their behavior.

The photo-sharing practice, because it offers a novel moment in the expected clinician-patient interaction, also exposes three unstated assumptions about how medical interactions are expected to occur. First, there is an assumption that the patient wants to or is trying to eat healthy according to a VOM standard of nutrition. Second, there is a shared assumption in photo-sharing that while the patient’s photos will allow for VOL, those photos and their stories are also followed by a sometimes explicit, sometimes implicit move into VOM assessment talk (e.g., “this was my healthy (or unhealthy) meal”). And finally, it is assumed that the clinician will provide an assessment of the dietary choices presented (e.g., “yes, that is healthy” or “did you know that is unhealthy?”). These last two assumptions are important because they are also the driving force behind how the interaction progresses and whether the interaction can move through goal-setting and on to the next activity. While seemingly steeped in VOM, the conversations that moved through goal-setting and to the next activity were actually the ones where clinicians took into account and framed their suggestions using information from the patient’s lifeworld.

Although the cases all shows the patient’s assessment of their foods as good or bad, the patient’s presentation of the photos are not simply positioned along a binary (e.g., singularly healthy or unhealthy), but rather are holistically presented (e.g., this is the healthiest meal I can get for free from the food bank). By centering on the patient’s VOL talk, it is noteworthy that interactions did not always focus on good or healthy behavior. Instead, what appears is that the quality of the clinician-patient interaction may rest on whether the photos open space for the clinician to acknowledge the patient as a holistic person through voicing VOL. In the conversations that did not pass through goal-setting, it appears that the patient’s behavior is assessed solely as “healthy” or “unhealthy,” with the conversational goal seeming to be the patient’s alignment to the clinician’s assessment of unhealthy behavior. The photos are treated simply as objective evidence for the assessment. On the other hand, as Case Two demonstrated, although the clinician assessed the patient’s behavior as unhealthy, the patient was able to present his unhealthy behavior through a wider lens insisting on VOL. His “resistance” occurs through his explanation of his behavior as somewhat out of his control, which allows the clinician to shift focus to what the patient can control and do. This shift allows clinician and patient to come together to set a shared goal about future actions to eat less of the rice offered. Though the photo-sharing practice offers a sanctioned space for VOL-rich interactions to happen, photo-sharing alone does not guarantee that interactions will progress.

As a novel practice, clinicians and patients are still negotiating exactly what should happen when discussing photos. A dialectical tension exists between the intention of photo-sharing which allows for VOL talk and yet, on the other hand, both patients and clinicians expect clinicians to offer a medical assessment of those choices. This tension between the dominance of VOM while trying to open conversational space for VOL culminated in whether and how interactions moved through goal-setting.

In terms of practice implications and avenues for future research, we offer anchoring points, or best interactional practices, for clinicians and patients to center VOL talk in photo-sharing which leads to shared goal-setting. Patients should be reminded to use the photos to explain not just their simple assessment of the healthiness of their foods, but rather, to give a whole picture of all that goes into their dietary choices and then be open to learning from clinician’s assessment of their behaviors. Clinicians can be reminded to learn and ask questions to center VOL-talk in order that their assessment of the healthiness of the foods and subsequent recommendations might be more easily followed. Future research can explore the extent to which clinician-patient alignment based on the photo-sharing promotes patient-centered care. It is important to note that photos alone cannot “save” an interactionally difficult conversation, and that is not their primary goal; rather it offers a space for both parties to utilize photos to promote successful instances of VOL-centered interactions through an immediate and sanctioned space in the visit. Moving forward, researchers may use and build upon this conceptual model in a larger implementation study to improve clinical care.

This paper is not without its limitations, which includes a small sample size and the fact that data were collected from a single site. Future research should draw on larger sample sizes and a wider range of sites, as well as collecting not just audio but also video data to allow for a more robust investigation of the discursive moves that may lead conversation down one pathway versus another. Additionally, explicitly measuring health outcomes or patient satisfaction might be of interest to both health researchers and clinicians alike. Lastly, further research could focus on the trainability of this protocol - whether or not patients and clinicians alike can be trained to engage in successful interactional pathways in photo-sharing - and/or whether the more successful clinicians and patients were already well trained or strong communicators. Despite these limitations, photo-sharing seems to be a useful clinical tool that can practically voice VOL into primary care interactions in positive ways for both clinician and patient.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the study participants as well as research assistants Liliana Del Carmen Chacón, Jennifer Fung, Joselvin Galeas, and Ying Wang.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (award numbers R03 AG050880 and P30 AG044281) and received additional support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (award number KL2 TR001870) and the University of California San Francisco Hellman Fellows Fund. Dr. Jih is supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health (award number K23 MD015089). The funding sources had no role or involvement in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflicts of Interest: None

Data Availability:

Because these data are HIPAA protected, readers can contact senior author with questions.

References

- Albury C, Stokoe E, Ziebland S, Webb H, & Aveyard P (2018). GP-delivered brief weight loss interventions: A cohort study of patient responses and subsequent actions, using conversation analysis in UK primary care. British Journal of General Practice, 68(674), e646. 10.3399/bjgp18X698405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton J, Dew K, Dowell A, Sheridan N, Kenealy T, Macdonald L, Docherty B, Tester R, Raphael D, Gray L, & Stubbe M (2016). Patient resistance as a resource: Candidate obstacles in diabetes consultations. Sociology of Health & Illness, 38(7), 1151–1166. 10.1111/1467-9566.12447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen C (2020). The conditional legitimacy of behavior change advice in primary care. Social Science & Medicine, 255, 112985. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K, Schoenbaum SC, & Audet A-M (2005). A 2020 vision of patient-centered primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20(10), 953–957. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0178.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobos AR, Orthia LA, & Lamberts R (2015). Does a picture tell a thousand words? The uses of digitally produced, multimodal pictures for communicating information about Alzheimer’s disease. Public Understanding of Science, 24(6), 712–730. 10.1177/0963662514533623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, & Coffey RM (1998). Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Medical Care, 36(1), 8–27. 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkowski T (2012). ‘Occasional’ drinking: Some uses of a non-standard temporal metric in primary care assessment of alcohol use. In Beach WA (Ed.), Handbook of patient-provider interactions: Raising and responding to concerns about life, illness, and disease (pp. 321–329). Hampton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ho EY, Leung G, Fung J, & Jih J (2021). “I didn’t know you were such a good cook”: Photos as a tool for primary care clinician-patient communication. Patient Education and Counseling, 104(6), 1356–1363. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.10.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges BD, Kuper A, & Reeves S (2008). Qualitative research: Discourse analysis. British Medical Journal, 337(7669), 570–572. 10.1136/bmj.a879 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, Florez H, Haas LB, Halter JB, Huang ES, Korytkowski MT, Munshi MN, Odegard PS, Pratley RE, & Swift CS (2012). Diabetes in older adults: A consensus report. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(12), 2342–2356. 10.1111/jgs.12035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig CJ (2011). Patient resistance as agency in treatment decisions. Social Science & Medicine, 72(7), 1105–1114. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig CJ, Wenger M, Graham GD, Asch S, & Rongey C (2019, Apr). Managing professional knowledge boundaries during ECHO telementoring consultations in two Veterans Affairs specialty care liver clinics: A theme-oriented discourse analysis. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 25(3), 181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo M-CM (2010, September 1, 2010). Cultural brokerage: Creating linkages between voices of lifeworld and medicine in cross-cultural clinical settings. Health, 14(5), 484–504. 10.1177/1363459309360795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MP (2005). Best questions and tools for quickly assessing your patient’s dietary health: Towards evidence-based determination of nutritional counseling need in the general medical interview. Nutrition Noteworthy, 7(1). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9s03p43r#metrics [Google Scholar]

- Mishler EG (1984). The discourse of medicine: Dialectics of medical interviews. Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JC, Antony MG, & Thomas RJ (2012). “This right here is all about living”: Communicating the “common sense” about home stability through CBPR and photovoice. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 40(3), 247–270. 10.1080/00909882.2012.693941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C, & Sarangi S (2005). Theme-oriented discourse analysis of medical encounters. Medical Education, 39(6), 632–640. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02171.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffrin D (1987). Discourse markers. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman HK (2017). Food insecurity and “unexplained” weight loss. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(3), 421–422. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy K (2001). Discourse analysis in communication. In Schiffrin D, Tannen D, & Hamilton H (Eds.), Handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 728–749). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker S, Bramante C, Conroy M, Fitch A, Gilden A, Wittleder S, & Jay M (2021). The most undertreated chronic disease: Addressing obesity in primary care settings. Current Obesity Reports, 10(3), 396–408. 10.1007/s13679-021-00444-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter ML, Herring SJ, Sood M, Shah NR, & Kalet AL (2008). What do resident physicians know about nutrition? An evaluation of attitudes, self-perceived proficiency and knowledge. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 27(2), 287–298. 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, & Burris MA (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369–387. 10.1177/109019819702400309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Because these data are HIPAA protected, readers can contact senior author with questions.