Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) primarily affects mechanical load-bearing joints, with the knee being the most common. The prevalence, burden and severity of knee osteoarthritis (KOA) are disproportionately higher in females, but hormonal differences alone do not explain the disproportionate incidence of KOA in females. Mechanical unloading by spaceflight microgravity has been implicated in OA development in cartilaginous tissues. However, the mechanisms and sex-dependent differences in OA-like development are not well explored. In this study, engineered meniscus constructs were generated from healthy human meniscus fibrochondrocytes (MFC) seeded onto type I collagen scaffolds and cultured under normal gravity and simulated microgravity conditions. We report the whole-genome sequences of constructs from 4 female and 4 male donors, along with the evaluation of their phenotypic characteristics. The collected data could be used as valuable resources to further explore the mechanism of KOA development in response to mechanical unloading, and to investigate the molecular basis of the observed sex differences in KOA.

Subject terms: Mechanisms of disease, Data acquisition

| Measurement(s) | Transcriptome |

| Technology Type(s) | mRNA Sequencing |

| Factor Type(s) | Mechanical stimulation |

| Sample Characteristic - Organism | Homo sapiens |

Background & Summary

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease that primarily affects mechanical load-bearing joints, with the knee being the most common1,2. Much of the focus of OA is on knee osteoarthritis (KOA) due to its 83% prevalence among cases of OA3,4. Most demographic groups are affected by OA, but the prevalence and burden are disproportionately higher in females2,5–10. While sex hormones regulate joints’ cartilage and bone development and homeostasis in a sex-dependent manner, hormonal differences alone do not fully account for the higher incidence of OA in females8. Kinney et al. reported that sex-specific variations in the response of human articular chondrocytes to estrogen are due to differences in receptor number and the mechanisms of estrogen action11.

The molecular basis for sex differences in the burden of KOA is not well understood, and questions remain for the cellular and molecular events underlying the pathogenesis and progression of KOA. However, some cellular and molecular characteristics of KOA resemble chondrocyte hypertrophy before endochondral ossification during skeletogenesis12. This includes chondrocyte proliferation, chondrocyte hypertrophy along with upregulation of hypertrophy markers COL10A113 and MMP1314, remodelling of the cartilage matrix by proteases, vascularization, and focal calcification of cartilage with hydroxyapatite crystals.

A plethora of in vitro and in vivo studies show joint cartilage atrophy after long-term mechanical unloading (i.e., joint immobilization)15–24. For example, in a case study involving ten healthy young individuals (4 males and 6 females), with no history of KOA requiring 6 to 8 weeks of non-weight bearing for injuries affecting the distal lower extremity, the axial mechanical unloading of the joint resulted in increased magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) parameters, T1rho and T2 relaxation times, of the knee articular cartilage that resembled signs of KOA. After four weeks of returning to axial mechanical loading, the T1rho and T2 relaxation times were restored to baseline values of normal healthy articular cartilage21. However, it is unknown if the magnitude or rate of cartilage atrophy was disproportionate between the male and female participants after mechanical unloading. And neither were knee menisci investigated despite their functional importance for load distribution across the knee joint.

The effects of mechanical unloading on cartilage have been studied via simulated microgravity (SMG)22,23,25–27. Microgravity, both real and simulated, as well as reduced weight-bearing, have been shown to induce detrimental effects on cartilage, and in some cases, promote an OA-like phenotype16,19,20,23,24,28,29. This makes SMG a relevant model to study OA-related changes in chondrocytes from mechanical unloading conditions23,25. SMG can be produced by rotating wall vessel (RWV) bioreactors developed by the National Aeronautics Space Administration (NASA). RWV rotates at a constant speed to maintain tissues in a suspended free-fall, resulting in a randomized gravitational vector24,30. Our group has demonstrated that four weeks of SMG using a RWV bioreactor could enhance KOA-like gene modulations in bioengineered cartilage26. Specifically, COL10A1 and MMP13 as markers of chondrocyte hypertrophy were significantly increased by SMG26. However, the potential of mechanical unloading and molecular profiling techniques to explore the molecular basis of the disproportionate incidence of KOA in females is yet to be explored. Menisci from KOA joints have been reported to exhibit similar molecular characteristics found in osteoarthritic articular cartilage31,32. Osteoarthritic meniscus fibrochondrocytes (MFC) produced more calcium deposits than normal MFC32,33. Moreover, osteoarthritic MFC expressed aggrecan (ACAN) at a significantly higher level than normal MFC33. More recently, type X collagen and MMP-13 were shown to be highly expressed in osteoarthritic meniscus relative to the normal meniscus31. As both proteins are markers of chondrocyte hypertrophy, these findings suggested that MFC undergo hypertrophic differentiation like osteoarthritic articular chondrocytes and that the knee menisci maybe actively involved in the pathogenesis of OA. The potential impact of OA on meniscus tissue was also explored in a mice model that was exposed to either microgravity on the International Space Station or hind limb unloading16. Prolonged unloading in both treatments resulted in cartilage degradation, meniscal volume decline, and elevated catabolic enzymes such as MMPs16.

In this study, meniscus models were generated from healthy human meniscus MFC seeded onto a type I collagen scaffold and cultured under SMG condition in RWV bioreactor with static normal gravity as controls. Full transcriptome RNA-sequencing of 4 female and 4 male donors were conducted, along with the analysis of phenotypic characteristics. Data from this study could be used to further explore the mechanism of the early onset of KOA and to investigate the molecular basis of observed sex differences in KOA.

Methods

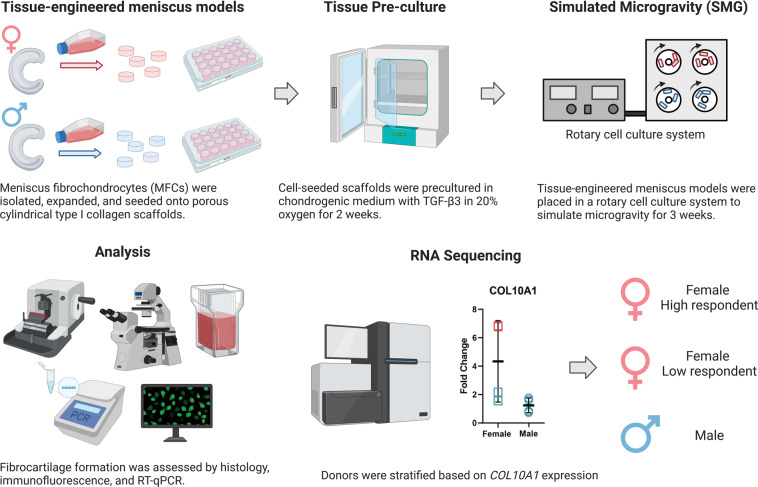

The experiment is outlined in Fig. 1. Most culture methods and assays were performed identically to those described in previous work34–36.

Fig. 1.

Experiment overview. Human meniscus fibrochondrocytes (MFC) were isolated from 4 males and 4 females. Complete treatment was repeated for each donor. Created with BioRender.com.

Ethics statement

Human non-osteoarthritic inner meniscus samples were obtained from patients undergoing arthroscopic partial meniscectomies because of traumatic meniscal tears at the Grey Nuns Community Hospital in Edmonton. Experimental methods and tissue collection were with the approval of and in accordance with the University of Alberta’s Health Research Ethics Board-Biomedical Panel (Study ID: Pro00018778). The ethics board waived the need for written informed consent of patients, as specimens used in the study were intended for discard in the normal course of the surgical procedure. Extensive precautions were taken to preserve the privacy of the participants donating specimens such that only patient sex, age, weight, height, and underlying health conditions were provided.

Cell isolation

Meniscus fibrochondrocytes (MFC) were isolated from inner meniscus specimens by digestion with type II collagenase (0.15% w/v of 300 units/mg; Worthington). For this, the inner meniscus specimens were first cut into smaller pieces. The type II collagenase solution in high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (HG-DMEM) supplemented with 5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) was added to pieces at a ratio of 10 mL per 1 g of the meniscus and left to incubate at 37 °C for 22 hours in an orbital shaker set at 250 rpm. After digestion, the cell suspension was filtered through a 100-μm nylon mesh filter (Corning Falcon, NY, USA), and MFC were isolated by centrifuge. The isolated MFC were plated for 48 hours to recovery before cell expansion.

Cell expansion

After 48 hours, the MFC were detached by 0.05% w/v trypsin-EDTA in Hank’s buffered saline solution (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and plated in a tissue culture flask (Sarstedt, Germany) at 104 cells/cm2 in HG-DMEM supplemented with 10% v/v heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (all from Sigma-Aldrich Co., MO, USA), and 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin and 0.29 mg/mL glutamine (PSG; Life Technologies, ON, Canada), and 5 ng/mL of FGF-2 (Neuromics, MH, USA, catalog #: PR80001) and 1 ng/mL of TGF-β1 (ProSpec, catalog #: CYT-716) for 1 week. Cell population doubling (PD) was calculated as the log2(N/NO), where NO and N are the number of MFC respectively at the beginning and the end of the cell amplification period.

3D Cell culture in porous type I collagen scaffold

The expanded MFC were resuspended in a defined serum-free chondrogenic medium HG-DMEM supplemented with HEPES, PSG, ITS + 1 premix, 125 μg/mL of human serum albumin, 100 nM of dexamethasone, 365 μg/mL ascorbic acid 2-phosphate, 40 μ/mL of L-proline, and 10 ng/mL of TGF-β3, followed by seeding onto type I collagen scaffolds (diameter: 6 mm or 10 mm; height: 3.5 mm; pore size: 115 ± 20 μm, Integra LifeSciences, NJ, USA) at the density of 5 × 106 cells/cm3. The cell-seeded scaffolds were cultured in a 24-well plate (12-well plate for 10 mm scaffolds) with serum-free chondrogenic medium for 2 weeks for initial extracellular matrix formation. Medium change was performed once per week.

Mechanical stimulation

After 2 weeks of preculture, engineered meniscus tissues of each donor were randomly assigned to two mechanical stimulation groups: static control under normal gravity and simulated microgravity (SMG). Each experimental group had 8 technical replicates of engineered tissue constructs. For the static control group, engineered constructs were cultured in a tissue culture tube (Sarstedt, Germany) with 55 mL serum-free chondrogenic medium for 3 weeks. For the SMG group, the same number of constructs were cultured in the slow turning lateral vessels (STLV; Synthecon, Inc., TX, USA) on a rotary cell culture system (RCCS-4; Synthecon, Inc.) with 55 mL of serum-free chondrogenic medium for 3 weeks. The rotation speed of the STLV was adjusted during the 3-week treatment to account for the increasing weight of the tissues and to maintain a stable free-falling position (30 rpm from day 1 to day 2, 34 rpm from day 3 to day 7, 37 rpm day from 8 to day 13, 40 rpm day from 14 to day 21). Medium change was performed for both groups once per week.

Histology and immunofluorescence

After 3 weeks of mechanical stimulation, constructs intended for histology and immunofluorescence were fixed in 1 mL of 10% v/v buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) overnight at 4 °C, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin wax. The embedded tissues were sectioned at 5 μm thickness and stained for Safranin O, Fast Green, Haematoxylin, collagen type I, collagen type II, and collagen type X.

For immunofluorescence staining, the sections were first deparaffinized and rehydrated. Protease XXV (Thermo Scientific) and hyaluronidase (Sigma-Aldrich) were then applied for 30 min each to improve antigen accessibility. Blocking was performed with 5% w/v bovine serum albumin in PBS for 30 min before staining for the primary antibody. Collagen type I, type II, and type X were stained with a 1:200 dilution of rabbit anti-collagen I antibody (CL50111AP-1; Cedarlane Labs, ON, Canada), a 1:200 dilution of mouse anti-collagen II antibody (II-II6B3, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, IA, USA), and a 1:100 dilution of rabbit anti-collagen X antibody (ab58632; Abcam, UK), respectively. The sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Secondary antibody labelling was applied on the second day. A 1:200 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H&L Alexa Fluor 594; Abcam) was used for collagen I and X. A 1:200 goat anti-mouse IgG (H&L Alexa Fluor 488; Abcam) was used for collagen II. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Cedarlane) after secondary antibody staining. The slides were finally mounted with a 1:1 ratio of glycerol and PBS. The Eclipse Ti-S microscope (Nikon Canada; ON, Canada) was used for immunofluorescence images.

RNA extraction, RT-qPCR, and RNA Sequencing

Constructs intended for transcriptome analysis were preserved in Trizol (Life Technologies) immediately upon harvesting and stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction. For female and male donors # 1, 2, and 3, RNA was extracted and purified from ground samples using PuroSPIN Total DNA Purification KIT (Luna Nanotech, Canada) following the manufacturer’s protocol. For female and male donors # 4, RNA was extracted and purified from ground samples using RNeasy Minikits (Qiagen, ON, Canada) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality of purified RNA was assessed by Nanodrop One (Thermo Scientific, USA), and fixed mass of RNA were sent for RNA sequencing at the University of British Columbia Biomedical Research Centre (UBC-BRC). A standard quality control assessment was conducted on the RNA samples prior to sequencing. All RNA samples showed reasonable quality and no noticeable differences were observed in quality between the two isolation methods. Next-generation sequencing was performed on the Illumina NextSeq. 500 with paired-end 42 bp × 42 bp reads and FastQ files were obtained from sequenced donors for further bioinformatics analysis.

Extracted RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with GoScript reverse transcriptase (Fisher Scientific) and amplified by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) for chosen genes with specific primers (Table 1). The expression level of selected genes was normalized to chosen housekeeping genes (Table 1; B-actin, B2M, and YWHAZ) based on the coefficient of variation (CV) and M-value as measures of reference gene stability37, and the data was presented using the 2−∆∆CT method38,39. An unpaired t-test was performed between treatment groups.

Table 1.

Real-time qPCR Primer Sequences.

| Gene | Forward | Reverse | GenBank Accession |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACAN | AGGGCGAGTGGAATGATGTT | GGTGGCTGTGCCCTTTTTAC | NM_001135.3 |

| Β-actin | AAGCCACCCCACTTCTCTCTAA | AATGCTATCACCTCCCCTGTGT | NM_001101.4 |

| B2M | TGCTGTCTCCATGTTTGATGTATCT | TCTCTGCTCCCCACCTCTAAGT | NM_004048.3 |

| COL1A2 | GCTACCCAACTTGCCTTCATG | GCAGTGGTAGGTGATGTTCTGAGA | NM_00008 9.3 |

| COL2A1 | CTGCAAAATAAAATCTCGGTGTTCT | GGGCATTTGACTCACACCAGT | NM_001844.5 |

| COL10A1 | GAAGTTATAATTTACACTGAGGGTTTCAAA | GAGGCACAGCTTAAAAGTTTTAAACA | NM_000493.3 |

| SOX9 | CTTTGGTTTGTGTTCGTGTTTTG | AGAGAAAGAAAAAGGGAAAGGTAAGTTT | NM_000346.3 |

| YWHAZ | TCTGTCTTGTCACCAACCATTCTT | TCATGCGGCCTTTTTCCA | NM_003406.3 |

Bioinformatics and donor stratification

Next-generation sequencing data were analyzed with Partek® Flow® software (Version 10.0.21.0302, Copyright © 2021, Partek Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA). A quality score threshold of 20 was set to trim the raw input reads from the 3′ end. Trimmed data were then aligned to the reference human genome hg38 using the STAR 2.7.3a aligner and followed by the quantification to a transcript model (hg38-RefSeq Transcripts 94 - 2020-05-01) using the Partek E/M algorithm. A noise reduction filter was applied to exclude genes whose maximum read count was below 50. Quantified and filtered reads were then normalized using the Add: 1.0, TMM, and Log 2.0 methods in sequential order. Based on the fold change of COL10A1 expression level (SMG to static), sequenced female donors were stratified into a high-response group and a low-response group, while male donors remained in one group for further analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for sex and treatment. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for each comparison were determined by p-value and fold change (FC). Principal component analysis (PCA) and the visualization of DEGs using Venn diagrams were all conducted in Partek® Flow® software.

Data Records

All data generated during this study are deposited in the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) with accession number GSE192983. The deposited data includes the raw FastQ files and.txt files containing normalized counts generated as described in the method section. The raw RNA Sequencing dataset can be found in the online repository40. The histology and immunofluorescence figures of each treatment group for all donors can be accessed at Figshare41.

Technical Validation

Phenotypes of engineered meniscus constructs under different culture conditions

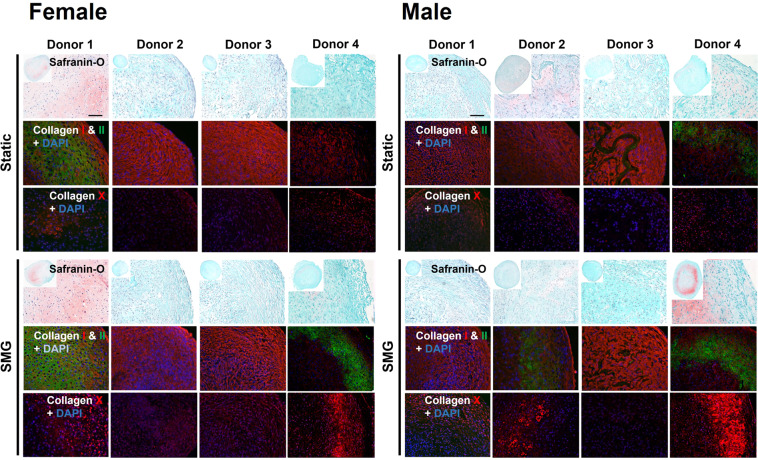

The non-identifiable information of the donors of meniscal specimens are listed in Table 2. After the 2-week preculture and 3-week mechanical stimulation periods, engineered meniscus constructs’ chondrogenic and hypertrophic differentiation potential was qualitatively assessed with Safranin O staining and collagen type I, II, and X immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 2). Donors from both biological sexes exhibited cartilage-like phenotype with a wide range of chondrogenic capacity at the static baseline. Tissues that intensively stained for Safranin O and collagen type II showed more hyaline cartilage-like phenotype, while the rest with strong collagen type I staining showed more fibrous cartilage-like phenotype. The expression levels of collagen type X were comparable for all donors under static conditions. SMG upregulated collagen type X expression in nearly all donors, but the highly variable staining between donors makes it difficult to determine sex differences.

Table 2.

Meniscal specimen non-identifying donor information.

| Sex | Donor Number | Age | Population Doubling (PD) | Sample Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Donor 1 | 33 | 2.687 | ScACS1.1, ScACS1.2 |

| Donor 2 | 44 | 2.38 | ScACS3.1, ScACS3.2 | |

| Donor 3 | 30 | 2.774 | ScACS4.1, ScACS4.2 | |

| Donor 4 | 24 | 1.599 | ScAAK9, ScAAK10 | |

| Male | Donor 1 | 19 | 3.349 | ScACS2.1, ScACS2.2 |

| Donor 2 | 45 | 2.699 | ScACS5.1, ScACS5.2 | |

| Donor 3 | 22 | 3.247 | ScACS6.1, ScACS6.2 | |

| Donor 4 | 23 | 2.263 | ScAAK7, ScAAK8 |

Fig. 2.

Impact of SMG in the chondrogenic and hypertrophic differentiation potential of engineered meniscus tissues. For each treatment group (static or SMG), top panel: safranin O staining, middle panel: collagen types I, II immunofluorescence staining, bottom panel: collagen type X immunofluorescence staining. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Quality of whole genome sequencing data

The summary information of the generated RNA-sequencing and processing quality data of each sample is listed in Table 3. The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) of all sequenced samples were close to 10 (10 is the highest possible RNA quality), and the average pre-alignment read quality had Phred scores above 30, indicating high-quality reads. The trimming and alignment algorithm used resulted in an average of at least 95% alignment as well as having the read quality Phred scores maintained. The authenticity of the RNA-sequencing data is also validated by calculating the degree of correlation with the RT-qPCR data of selected genes (Supplementary Fig. 1). An R2 value of 0.828 was achieved, showing a strong correlation between the two transcription measurement methods.

Table 3.

Quality data of RNA-sequencing and bioinformatics processing.

| Sample Name | Group | RNA extract. method | RNA conc. (ng/µL) | RIN | Pre-alignment | Post-alignment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total reads | Avg. read length | Avg. quality* | Total reads | Aligned (%) | Avg. length | Avg. quality* | |||||

| ScAAK7 | Static | RNeasy Minikits | 1.2 | 9.1 | 25994148 | 42.55 | 33.60 | 25851954 | 95.38 | 42.45 | 33.83 |

| ScAAK8 | SMG | 1.2 | 9.1 | 22585197 | 42.54 | 33.65 | 22464022 | 95.80 | 42.44 | 33.87 | |

| ScAAK9 | Static | 2.2 | 8.6 | 23676028 | 42.54 | 33.65 | 23550183 | 96.06 | 42.44 | 33.87 | |

| ScAAK10 | SMG | 2.1 | 8.7 | 20942143 | 42.54 | 33.52 | 20829886 | 95.89 | 42.43 | 33.74 | |

| ScACS1.1 | Static | PuroSPIN Total DNA Purification KIT | 44 | 10 | 21673085 | 42.50 | 34.08 | 21649968 | 96.20 | 42.40 | 34.27 |

| ScACS1.2 | SMG | 83 | 9.3 | 26393415 | 42.52 | 34.08 | 26363008 | 95.26 | 42.41 | 34.32 | |

| ScACS2.1 | Static | 93 | 9.6 | 24756374 | 42.50 | 34.03 | 24728910 | 96.41 | 42.39 | 34.23 | |

| ScACS2.2 | SMG | 68 | 9.5 | 24302152 | 42.49 | 34.06 | 24276178 | 96.47 | 42.38 | 34.27 | |

| ScACS3.1 | Static | 61 | 10 | 20187929 | 42.48 | 33.94 | 20166326 | 96.42 | 42.36 | 34.13 | |

| ScACS3.2 | SMG | 33 | 9.3 | 24542608 | 42.50 | 34.12 | 24520924 | 96.89 | 42.40 | 34.25 | |

| ScACS4.1 | Static | 108 | 10 | 24586213 | 42.50 | 34.10 | 24563673 | 96.93 | 42.39 | 34.24 | |

| ScACS4.2 | SMG | 156 | 10 | 23942119 | 42.50 | 34.06 | 23920514 | 96.99 | 42.39 | 34.21 | |

| ScACS5.1 | Static | 110 | 9.8 | 24244159 | 42.50 | 34.10 | 24222229 | 96.93 | 42.39 | 34.24 | |

| ScACS5.2 | SMG | 181 | 9.9 | 25369559 | 42.50 | 34.06 | 25347026 | 96.84 | 42.39 | 34.22 | |

| ScACS6.1 | Static | 126 | 9.7 | 23496618 | 42.50 | 34.12 | 23473652 | 96.64 | 42.40 | 34.26 | |

| ScACS6.2 | SMG | 175 | 10 | 23589464 | 42.50 | 34.06 | 23567332 | 96.80 | 42.39 | 34.21 | |

*Phred Quality Score (−10log10Prob) 30: Base call accuracy 99.9%, 40: Base call accuracy 99.99%.

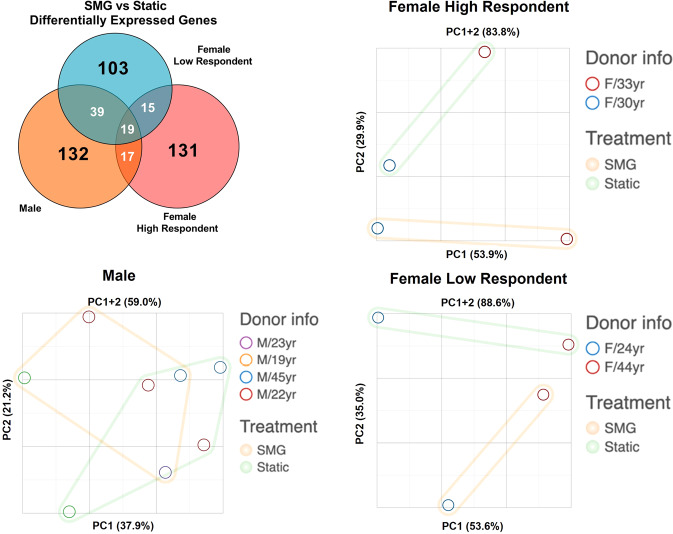

Donor stratification based on expression level of COL10A1

To account for the effect of the donor variability observed in the previous analyses, a stratification strategy was introduced to separate donors into sub-groups based on the OA-inducing propensity of SMG. Female donors were stratified into high respondents with a higher fold change of COL10A1 (female donor # 2: 6.84-fold and female donor # 4: 6.78-fold) and low respondents with a lower fold change of COL10A1 (female donor # 1: 1.56-fold and female donor # 3: 2.17-fold). Male donors all had similar expression fold change of COL10A1 and remained in one group. The stratification strategy was verified by the Venn diagram showing the overlap of DEGs between the SMG and static in each subgroup and the PCA plot (Fig. 3). All DEGs that appeared in the Venn diagram are listed in Supplement Tables 1–7. The majority of DEGs were unique to each identified group and the samples were well separated by treatment type on the first two principal component (PC) for both female high and female low respondent groups. Further, Table 4 shows a panel of selected OA-related genes that are only significantly modulated in SMG compared to static control for the Female High Respondents cohort. These genes were not significant in the Female Low Respondents or the Male cohorts.

Fig. 3.

Donor stratification and distinct effect of SMG on sub-groups. DEGs of each group were overlaid and principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted for individual sub-groups.

Table 4.

Select panel of OA-related genes from RNA-sequencing.

| Gene | Fold Change for SMG vs Static | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Female High Respondent | Female Low Respondent | Male | |

| BMP8A | 8.51** | −1.23 ns | −1.59 ns |

| CD36 | 11.8* | 1.93 ns | 1.10 ns |

| COL10A1 | 6.81*** | 1.57 ns | 1.17 ns |

| COL9A3 | 5.21* | 2.77 ns | −2.32 ns |

| FGF1 | 3.11* | −2.99 ns | −5.48 ns |

| IBSP | 46.1* | 1.19 ns | 1.21 ns |

| IHH | 4.38* | −1.61 ns | −1.99 ns |

| MMP10 | 43.8** | −3.42 ns | −5.29 ns |

| PHOSPHO1 | 2.42* | 1.34 ns | −1.45 ns |

| S100A1 | 3.42* | 2.01 ns | −2.34 ns |

| SPP1 | 46.8*** | 10.9 ns | 4.2 ns |

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns = not significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Tara Stach and her team at the University of British Columbia Biomedical Research Centre for their RNA sequencing service.

Author contributions

Z.M., R.C., D.L. and A.A. designed the study. Z.M., D.L., R.C. and A.M.S. performed tissue culture. Z.M., D.L., R.C. and M.K. performed RT-qPCR expression analysis. Z.M., D.L. and A.A. were responsible for RNA-Seq data analysis with Partek Flow software. Z.M., D.L., R.C. and L.W. were for mechanical test and analysis. Z.M. and D.L. performed the statistical analysis and prepared tables and figures. Z.M., D.L., R.C., L.W. and A.A. wrote the manuscript with input from all co-authors. M.S. was responsible for procuring clinical specimens for the study, reviewing, and editing the manuscript. D.G. was a co-applicant in the acquiring financial support for the study and assisted with reviewing and editing the manuscript. L.W. and A.A. were responsible for acquiring financial support and supervision of the study.

Funding

ZM: NSERC (NSERC RGPIN-2018-06290 Adesida)DL: NSERC Undergraduate Student Research AwardsRC: Alberta Innovates and WCHRI Summer StudentshipMK: Alberta Cancer Foundation-Mickleborough Interfacial Biosciences Research Program (ACF-MIBRP 27128 Adesida)AMS: Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR MOP 125921 Adesida)LW: University of Alberta Pilot Seed Grant Program (UOFAB PSGP); University of Alberta Women and Children’s Health Research Institute Innovation Grant (UOFAB WCHRIIG 3126)DG: University of Alberta Pilot Seed Grant Program (UOFAB PSGP); University of Alberta Women and Children’s Health Research Institute Innovation Grant (UOFAB WCHRIIG 3126)AA: Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC RGPIN-2018-06290 Adesida), NSERC RTI-2019-00310 Adesida; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR MOP 125921 Adesida); the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI 33786); University Hospital of Alberta Foundation (UHF; RES0028185 Adesida); the Edmonton Orthopaedic Research Committee the Cliff Lede Family Charitable Foundation (RES00045921 Adesida); University of Alberta Pilot Seed Grant Program (UOFAB PSGP); University of Alberta Women and Children’s Health Research Institute Innovation Grant (UOFAB WCHRIIG 3126); the Alberta Cancer Foundation-Mickleborough Interfacial Biosciences Research Program (ACF-MIBRP 27128 Adesida). Research grant funding for the work was provided by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC RGPIN-2018-06290 Adesida), NSERC RTI-2019-00310 Adesida; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR MOP 125921 Adesida); the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI 33786); University Hospital of Alberta Foundation (UHF; RES0028185 Adesida); the Edmonton Orthopaedic Research Committee; the Cliff Lede Family Charitable Foundation (RES00045921 Adesida); University of Alberta Pilot Seed Grant Program (UOFAB PSGP); University of Alberta Women and Children’s Health Research Institute Innovation Grant (UOFAB WCHRIIG 3126); the Alberta Cancer Foundation-Mickleborough Interfacial Biosciences Research Program (ACF-MIBRP 27128 Adesida).

Code availability

The bioinformatics software used for this study is Partek® Flow® software (Version 10.0.21.0302, Copyright © 2021, Partek Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) and the link of online REVIGO tool used is: http://revigo.irb.hr/.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Zhiyao Ma, David Xinzheyang Li, Ryan K. W. Chee.

Change history

10/10/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41597-024-03956-z

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41597-022-01837-x.

References

- 1.Nicolella, D. P. et al. Mechanical contributors to sex differences in idiopathic knee osteoarthritis. Biol Sex Differ3, 28 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyan, B. D. et al. Addressing the gaps: sex differences in osteoarthritis of the knee. Biol Sex Differ4, 4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(CDC, C. for D. C. and P. National and state medical expenditures and lost earnings attributable to arthritis and other rheumatic conditions–United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep56, 4–7 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray, C. J. L. et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet380, 2197–2223 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osteoarthritis. Bone and Joint Canadahttp://boneandjointcanada.com/osteoarthritis/ (2014).

- 6.Badley, E. M. & Kasman, N. M. The Impact of Arthritis on Canadian Women. BMC Womens Health4, S18 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connor, M. I. Sex Differences in Osteoarthritis of the Hip and Knee. JAAOS - Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons15, (2007). [PubMed]

- 8.Boyan, B. D. et al. Sex Differences in Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons20, 668–669 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan, Q. et al. Characterization of osteoarthritic human knees indicates potential sex differences. Biol Sex Differ7, 27 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breedveld, F. C. Osteoarthritis–the impact of a serious disease. Rheumatology43, 4i–48 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinney, R. C., Schwartz, Z., Week, K., Lotz, M. K. & Boyan, B. D. Human articular chondrocytes exhibit sexual dimorphism in their responses to 17β-estradiol. Osteoarthritis Cartilage13, 330–337 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dreier, R. Hypertrophic differentiation of chondrocytes in osteoarthritis: the developmental aspect of degenerative joint disorders. Arthritis Res Ther12, 216 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aigner, T. et al. Type X collagen expression in osteoarthritic and rheumatoid articular cartilage. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol63, 205–211 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Angelo, M. et al. MMP-13 is induced during chondrocyte hypertrophy. J Cell Biochem77, 678–693 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinterwimmer, S. et al. Cartilage atrophy in the knees of patients after seven weeks of partial load bearing. Arthritis Rheum50, 2516–2520 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwok, A. T. et al. Spaceflight and hind limb unloading induces an arthritic phenotype in knee articular cartilage and menisci of rodents. Sci Rep11, 10469 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu, W., Wang, L., Yao, J., Wo, C. & Chen, Y. C5a aggravates dysfunction of the articular cartilage and synovial fluid in rats with knee joint immobilization. Mol Med Rep10.3892/mmr.2018.9208 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mutsuzaki, H., Nakajima, H. & Sakane, M. Extension of knee immobilization delays recovery of histological damages in the anterior cruciate ligament insertion and articular cartilage in rabbits. J Phys Ther Sci30, 140–144 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou, Q. et al. Cartilage matrix changes in contralateral mobile knees in a rabbit model of osteoarthritis induced by immobilization. BMC Musculoskelet Disord16, 224 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagai, M. et al. Alteration of cartilage surface collagen fibers differs locally after immobilization of knee joints in rats. J Anat226, 447–457 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Souza, R. B. et al. Effects of Unloading on Knee Articular Cartilage T1rho and T2 Magnetic Resonance Imaging Relaxation Times: A Case Series. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy42, 511–520 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mellor, L. F., Steward, A. J., Nordberg, R. C., Taylor, M. A. & Loboa, E. G. Comparison of Simulated Microgravity and Hydrostatic Pressure for Chondrogenesis of hASC. Aerosp Med Hum Perform88, 377–384 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayer-Wagner, S. et al. Simulated microgravity affects chondrogenesis and hypertrophy of human mesenchymal stem cells. Int Orthop38, 2615–2621 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin, L. et al. The effects of simulated microgravity on intervertebral disc degeneration. The Spine Journal13, 235–242 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu, B. et al. Simulated microgravity using a rotary cell culture system promotes chondrogenesis of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells via the p38 MAPK pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun414, 412–418 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiss, W. M., Mulet-Sierra, A., Kunze, M., Jomha, N. M. & Adesida, A. B. Coculture of meniscus cells and mesenchymal stem cells in simulated microgravity. NPJ Microgravity3, 28 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma, Z. et al. Engineered Human Meniscus in Modeling Sex Differences of Knee Osteoarthritis in Vitro. Front Bioeng Biotechnol10 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Fitzgerald, J. Cartilage breakdown in microgravity—a problem for long-term spaceflight? NPJ Regen Med2, 10 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fitzgerald, J., Endicott, J., Hansen, U. & Janowitz, C. Articular cartilage and sternal fibrocartilage respond differently to extended microgravity. NPJ Microgravity5, 3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mellor, L. F., Baker, T. L., Brown, R. J., Catlin, L. W. & Oxford, J. T. Optimal 3D Culture of Primary Articular Chondrocytes for Use in the Rotating Wall Vessel Bioreactor. Aviat Space Environ Med85, 798–804 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiraly, A. J. et al. Comparison of Meniscal Cell-Mediated and Chondrocyte-Mediated Calcification. Open Orthop J11, 225–233 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun, Y. et al. Calcium deposition in osteoarthritic meniscus and meniscal cell culture. Arthritis Res Ther12, R56 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun, Y. et al. Analysis of meniscal degeneration and meniscal gene expression. BMC Musculoskelet Disord11, 19 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang, Y. et al. Plasticity of Human Meniscus Fibrochondrocytes: A Study on Effects of Mitotic Divisions and Oxygen Tension. Sci Rep7, 12148 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szojka, A. R. et al. Human engineered meniscus transcriptome after short-term combined hypoxia and dynamic compression. J Tissue Eng12, 204173142199084 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szojka, A. R. A. et al. Mechano-Hypoxia Conditioning of Engineered Human Meniscus. Front Bioeng Biotechnol9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Hellemans, J., Mortier, G., de Paepe, A., Speleman, F. & Vandesompele, J. qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biol8, R19 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmittgen, T. D. & Livak, K. J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc3, 1101–1108 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma, Z. et al. GEO.https://identifiers.org/geo/GSE192983 (2022).

- 41.Ma, Z. et al. Mechanical Unloading of Engineered Human Meniscus Models Under Simulated Microgravity: A Transcriptomic Study. Figshare10.6084/m9.figshare.21291903.v1 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Ma, Z. et al. GEO.https://identifiers.org/geo/GSE192983 (2022).

- Ma, Z. et al. Mechanical Unloading of Engineered Human Meniscus Models Under Simulated Microgravity: A Transcriptomic Study. Figshare10.6084/m9.figshare.21291903.v1 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The bioinformatics software used for this study is Partek® Flow® software (Version 10.0.21.0302, Copyright © 2021, Partek Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) and the link of online REVIGO tool used is: http://revigo.irb.hr/.