Abstract

The CRISPR-Cas9 system is widely used to permanently delete genomic regions via dual guide RNAs. Genomic rearrangements induced by CRISPR-Cas9 can occur, but continuous technical developments make it possible to characterize complex on-target effects. We combined an innovative droplet-based target enrichment approach with long-read sequencing and coupled it to a customized de novo sequence assembly. This approach enabled us to dissect the sequence content at kilobase scale within an on-target genomic locus. We here describe extensive genomic disruptions by Cas9, involving the allelic co-occurrence of a genomic duplication and inversion of the target region, as well as integrations of exogenous DNA and clustered interchromosomal DNA fragment rearrangements. Furthermore, we found that these genomic alterations led to functional aberrant DNA fragments and can alter cell proliferation. Our findings broaden the consequential spectrum of the Cas9 deletion system, reinforce the necessity of meticulous genomic validations, and introduce a data-driven workflow enabling detailed dissection of the on-target sequence content with superior resolution.

The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-associated protein 9 (CRISPR-Cas9) system has revolutionized genome engineering approaches. Various toolsets have been developed, which allow loss-of-function perturbations of functional genomic elements in a simple and efficient manner. To modify the genome, the components of the CRISPR-Cas9 system are exogenously introduced into human cells (Ran et al. 2013; Sander and Joung 2014; Søndergaard et al. 2020). In the presence of a guide RNA (gRNA) that is complementary to the target site and next to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), the expressed Cas9 endonuclease induces a double-strand break (DSB) at a specific genomic site. If an exogenous homologous DNA template is supplied, the DSB is repaired by the homology-directed repair to introduce specific mutations or insertions of desired sequences (Greene 2016). Alternatively, microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) can be triggered by short (5–25 bp) overlapping sequences that allow for recombination at the DSB (McVey and Lee 2008). In contrast, in the absence of a homologous template, the cell uses nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) to resolve the DSB. This usually results in small deletions or insertions of a few nucleotides (Sander and Joung 2014). Longer DNA regions can be excised from the genome by using dual gRNAs that flank the target region and guide Cas9 to induce two DSBs (Yang et al. 2013; Maddalo et al. 2014). Through this approach, a target region of about 1 Mb was successfully removed from the genome in mouse cells (Canver et al. 2014). In addition, a variety of genomic regions have been modified using the dual gRNA system. For example, the genomic manipulation of enhancers (Mansour et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2016), chromatin loop anchors (Guo et al. 2015, 2018b), protein-coding genes (Maddalo et al. 2014; Antoniani et al. 2018), and noncoding genes (Zhu et al. 2016) revealed disease-associated functional elements and genes.

Nuclear encoded transfer RNA (tRNA) genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase III (Pol III) through the recognition of internal promoter binding sites (White 2011, 2005). Pol III occupancy of tRNA genes is widely used to quantify tRNA gene usage (Barski et al. 2010; Moqtaderi et al. 2010; Oler et al. 2010; Kutter et al. 2011; Canella et al. 2012; Schmitt et al. 2014; Rudolph et al. 2016; Gao et al. 2022). In addition, Pol III-bound tRNA genes reside in euchromatic genomic regions, which are marked by active histone modifications, such as histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) (White 2011; Schmitt et al. 2014; Ottenburghs et al. 2021). tRNAs represent one of the most abundant RNA types, well known for decoding mRNA into proteins during translation, and many additional functions have been assigned (Su et al. 2020). Moreover, deregulation of tRNA genes perturbs cellular functions leading to several human diseases.

Here, we deleted a genomic region containing two tRNA genes using the dual gRNA CRISPR-Cas9 system. Despite validation of the successful deletion by standard PCR and Sanger sequencing, the targeted region remained functionally intact in the genome of human cells. We combined a target enrichment approach followed by long-read sequencing (Xdrop-LRS) with our customized de novo assembly-based analysis allowing us to efficiently capture and dissect the on-target sequence content in the order of kilobases. We resolved complex on-target genomic rearrangements with varying biological consequences. By introducing a powerful approach, this study contributes to a more reliable validation of CRISPR-Cas9-induced deletions and functional assessment of regulatory sequences in cell clones.

Results

The target region remained detectable and functional in Cas9 deletion clones

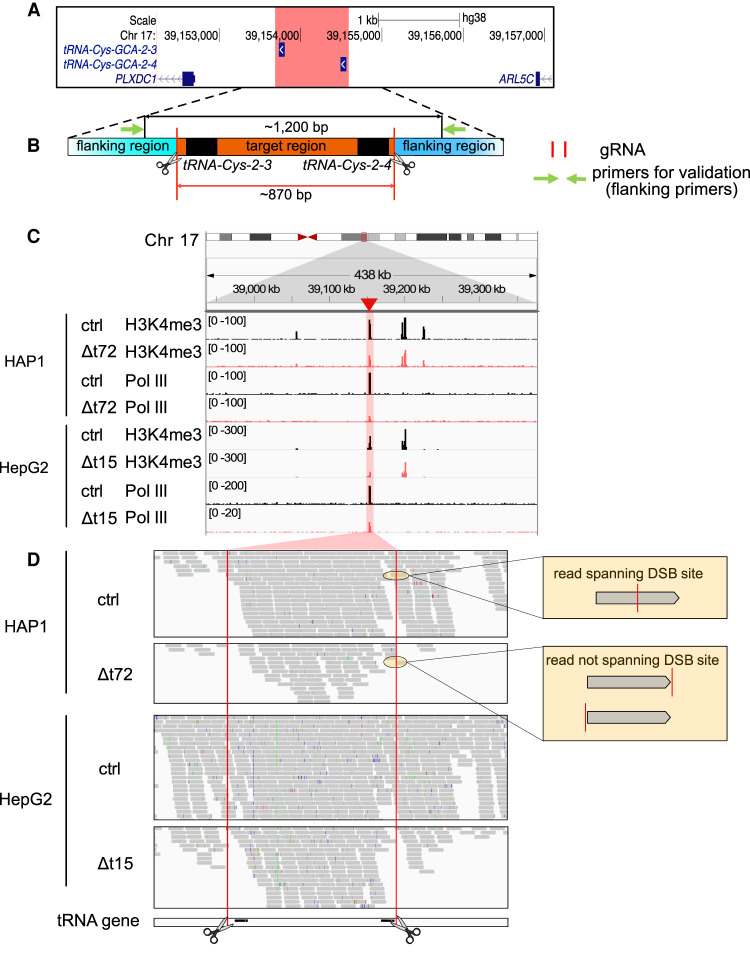

We focused on a pair of tRNA genes that is closely located on human Chromosome (Chr) 17 (Fig. 1A). We designed gRNAs mapping to the unique 5′ and 3′ flanking regions enabling Cas9 to excise an 870 bp long genomic fragment containing the two tRNA genes (Δt) (Fig. 1B). To validate the deletion of the target region in the genomes of human near-haploid chronic myeloid leukemia (HAP1) and hyperploid hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cell clones, we performed a PCR with flanking region-specific primers (flanking primers) and verified its sequence content by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. S1A). Overall, 94 HAP1 and 90 HepG2 single cell-derived clones were generated. Among them, 5 HAP1 and 17 HepG2 clones contained a deletion (Supplemental Fig. S1B–E; Supplemental Files). When validating the deletion in the HAP1 Δt72 clone, we noticed additional spurious PCR amplicons that could not be Sanger sequenced because of the low abundance (Supplemental Fig. S1C). Previous studies reported that the targeted sequence can be excised, duplicated, and inserted at the original gene locus when the dual gRNA system is used (Canver et al. 2014; Kraft et al. 2015; Li et al. 2015; Antoniani et al. 2018; Shou et al. 2018; Binda et al. 2020). We tested for the presence of a target duplication by PCR with target and flanking region-specific primers but did not obtain any PCR products in deletion clone HAP1 Δt72 (Supplemental Fig. S1D). This argued against the presence of a target duplication. Owing to the repetitive sequence content impeding unique primer binding (Fig. 1B), and commonly occurring genome instability in cancer cells, we reasoned that these additional PCR amplicons were unspecific.

Figure 1.

The target region remained functional in deletion clones. (A) The hg38 genome browser view shows the genomic location of our target locus (red). Arrows denote directionality of gene transcription. (B) Illustration of the design strategy of Cas9 dual guide RNA (gRNA) deletion strategy. Cas9 cut sites (red horizontal lines and scissors) and primers for validation (green arrows) are indicated. The target region (orange) containing two target transfer RNA (tRNA) genes (black) is around 870 bp. The size of the PCR product in control clones is around 1200 bp. (C) The hg38 genome browser view shows normalized ChIP-seq reads for histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) and RNA polymerase III (Pol III) covering the target loci (highlighted in red) in the HAP1 control (ctrl) and Δt72 as well as HepG2 ctrl and Δt15 clones. (D) Alignment tracks show individual H3K4me3 ChIP-seq reads of the deleted and surrounding region as in (C). DSB sites (red lines and scissors) and tRNA gene locations (black) are indicated. Examples of reads spanning (top) or not spanning (bottom) double-strand break (DSB) site are illustrated (yellow box).

To further characterize the consequences of tRNA gene deletions, we used published Pol III ChIP-seq data in HepG2 unmodified cells (Rudolph et al. 2016) and profiled the genome-wide binding of H3K4me3 and Pol III in deletion clones HAP1 Δt72 as well as HepG2 Δt15 and their respective nontargeting control (ctrl) clones (Fig. 1C). We only considered reads with high mapping quality. Unexpectedly, we observed binding of H3K4me3 and Pol III to DNA sequences at the target region in the two deletion clones, although the binding was weaker when compared with their respective control clones (Fig. 1C,D).

To explain this observation, we considered the presence of (1) heterozygous deletion clones (Canver et al. 2014), whereby one allele carries the deletion and the other allele is unmodified, (2) mutations occurring in the PAM sequences (Mali et al. 2013; Sternberg et al. 2014) preventing the recruitment of Cas9 and its cutting activity at the gene locus, and (3) unsynchronized Cas9 cleavage at the two DSB sites (Bosch-Guiteras et al. 2021), in which one DSB would have been repaired before the induction of the second DSB. These three scenarios can be excluded because we would have detected a PCR product corresponding to the size of the unmodified allele (Supplemental Fig. S1C–E). Notably, ChIP-seq reads spanned the excision site only in control but not in deletion clones, which is indicative for a Cas9 editing event (Fig. 1D). We therefore tested for alternative possibilities resulting from Cas9 genome engineering.

Applying Xdrop in deletion clones confirmed the genomic remodeling of the target region

The Xdrop technology has recently been applied to validate CRISPR-Cas9 genome modifications (Madsen et al. 2020; Blondal et al. 2021). Compared with other methods (Yin et al. 2019; Turchiano et al. 2021), Xdrop is more straightforward to apply; and when coupled to Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) long-read sequencing (LRS) delivers critical sequence information of the flanking regions, making it possible to decipher on-target outcomes. We therefore applied the Xdrop-LRS approach to enrich for and sequence molecules containing our CRISPR-Cas9-targeted genomic region in the HAP1 Δt72 and HepG2 Δt15 deletion clones. On average, we obtained 217,000 and 179,000 reads of a median size of 4600 and 5200 bp in the HAP1 Δt72 and HepG2 Δt15 deletion clones, respectively. Read coverage at the target locus in each cell clone indicated sufficient enrichment (Supplemental Fig. S2A,B). By aligning both corrected and raw reads to the human reference genome, we observed sharp drops in coverage at the two DSB sites and no read spanned the two DSB sites in these two deletion clones (Supplemental Fig. S2A). This supported our conclusion drawn from our ChIP-seq data that the target region in the deletion clones HAP1 Δt72 and HepG2 Δt15 was not directly connected to the flanking regions as annotated in the reference genome.

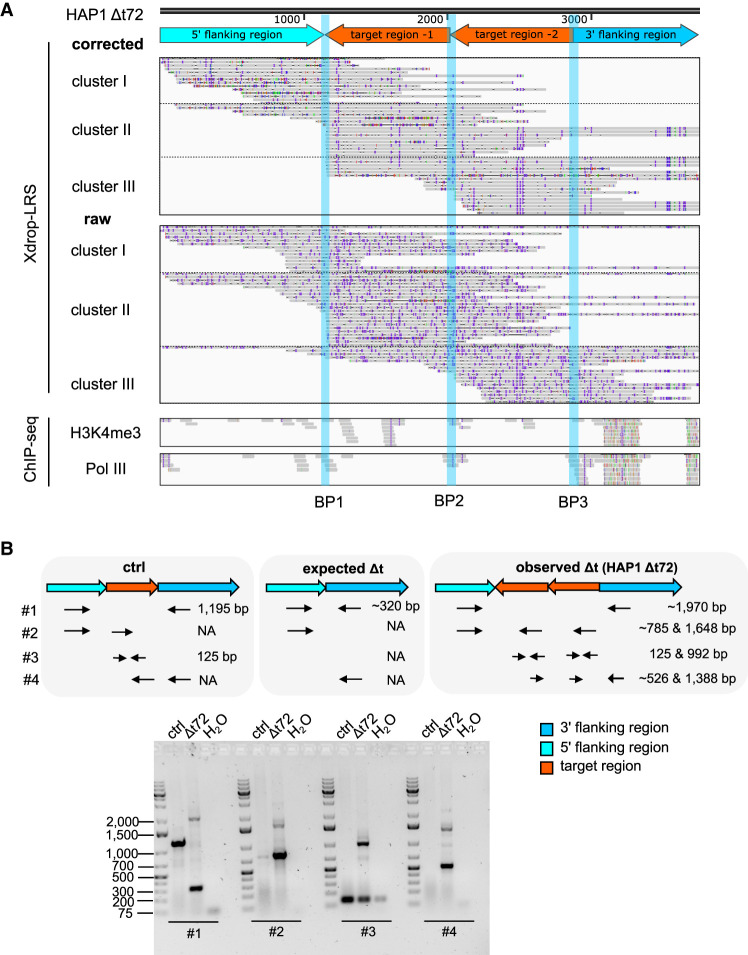

A de novo assembly-based approach revealed a duplication and inversion of the target region in the deletion clone HAP1 Δt72

To reveal the sequences of the aberrations proximal to the target region, we used a customized de novo sequence assembly approach (Supplemental Fig. S2C). In our deletion clone HAP1 Δt72, we identified contigs with three distinct breakpoints that deviated from the human reference genome composition (Fig. 2A). One breakpoint (BP2) connected two units of our deleted target region in tandem orientation. The other two breakpoints (BP1 and BP3) connected the duplicated fragments with the 5′ and 3′ flanking region of our original target region in inverse orientation. This suggested an unexpected event in which the deleted fragment of our target region was duplicated, inverted and inserted at the original locus (Fig. 2A). Both raw and corrected long reads spanned the contig and covered the individual breakpoints proving the accuracy of the assembled sequences (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

A duplication, inversion, and local insertion of target-derived fragments occurred in the deletion clone HAP1 Δt72. (A) The genome browser view shows Xdrop-LRS (top, corrected and raw reads) and ChIP-seq (bottom, histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation [H3K4me3] and RNA polymerase III [Pol III] reads) aligned against the assembled contig. Arrows (top) show genomic orientation and approximate size of the flanking (5′ light and 3′ dark blue) and target (orange) regions within the contig. Representative aligned reads for cluster I, II, and III support three different breakpoints (BP1-3, blue vertical lines) within the contig. (B) Schematic illustration of the primer design strategy to validate contigs by PCR. The expected amplicon length (top) represents allelic composition in an unmodified control (ctrl), as well as the expected and observed deletion event in the HAP1 Δt72 clone. Agarose gel (bottom) confirms the size of the expected (∼320 bp) and observed PCR products (∼1970 bp). Marker bands specify DNA size in bp.

Because multiple displacement amplification in droplets (dMDA) can lead to false positive calls of duplication and inversion events (Hård et al. 2021), we aligned our Illumina ChIP-seq data to the assembled contig. Without allowing for soft-clipped reads, we still found multiple H3K4me3 and Pol III ChIP-seq reads mapping to the three BPs and thereby confirmed our detected duplication and inversion (Fig. 2A). We independently validated our de novo sequence assembly by designing three sets of primers specific for the flanking and/or target region (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Table S1). The PCR-based data supported our Xdrop-LRS findings and further strengthened our conclusion that the target region was duplicated, inverted, and inserted in the HAP1 Δt72 deletion clone.

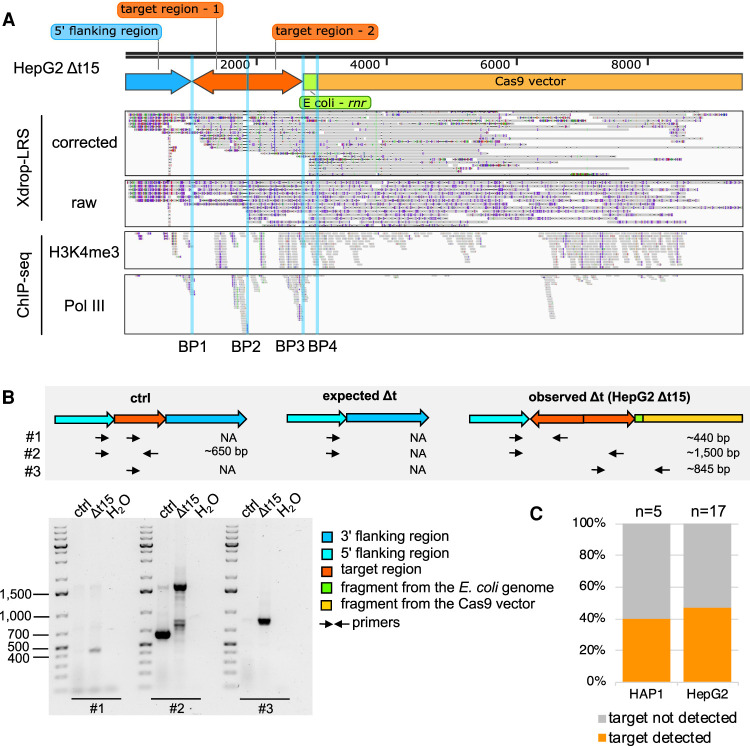

The target sequence was duplicated, inverted, and co-integrated with exogenous DNA fragments in the deletion clone HepG2 Δt15

In the deletion clone HepG2 Δt15, the assembly of our Xdrop-LRS reads revealed four breakpoints (Fig. 3A). We found a duplication of our target region connected by breakpoint 2 (BP2) in divergent orientation. This suggested that only one of the two target regions was inverted, which was further confirmed by BP1, which linked the 5′ flanking region of the target to the duplicated target region. Resolving the events at the 3′ cut site revealed that exogenous DNA fragments were integrated at the DSB site. We searched for high sequence similarity of these fragments (Methods) and found that an ∼200 bp long fragment aligned perfectly to a part of the rnr gene in the Escherichia coli genome (Fig. 3A). BP3 joined this 200 bp E. coli genome fragment and the duplicated target region. In addition, we detected a more than 6000 bp long fragment mapping to the CRISPR-Cas9 vector (Fig. 3A,B; Supplemental Fig. S3A). Detailed inspection revealed reads carrying the sequence of gRNA-Δt-1, which we synthesized to induce the DSB at the 5′ flanking region. There were no reads containing the sequence of gRNA-Δt-2, suggesting that the gRNA and the scaffold part of the CRISPR-Cas9-gRNA-Δt-1 but not -2 vector were integrated (Supplemental Fig. S3A). BP4 connected the E. coli fragment to the CRISPR-Cas9 vector sequence. In addition to raw and corrected Xdrop-LRS reads, we found H3K4me3 and Pol III ChIP-seq reads mapping to the BPs. Furthermore, our PCR results using primers annealing to different components of the contig, supported an accurate contig assembly (Fig. 3A,B).

Figure 3.

A duplication, inversion of target-derived fragments, and integration of exogenous DNA fragments arose in the deletion clone HepG2 Δt15. (A) The genome browser view shows Xdrop-LRS (top, corrected and raw reads) and ChIP-seq (bottom, histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation [H3K4me3] and RNA polymerase III [Pol III] reads) aligned against the assembled contig supporting four different breakpoints (BP1-4, blue vertical lines) within the contig. Arrows (top) show genomic orientation and approximate size of the flanking (blue) and target (orange) regions, as well as sequences of the E. coli genome (green) and the CRISPR-Cas9-gRNA-Δt-1 transfection vector (yellow) present within the contig. (B) Schematic illustration of the strategy to validate the contig and the expected PCR product length (top) of alleles with an unmodified control (ctrl), expected and observed editing event in deletion clone HepG2 Δt15. Alleles with the expected deletion and on-target alterations exist in deletion clone HepG2 Δt15. Agarose gel image (bottom) visualizes the size of the PCR products. Marker bands specify DNA size in bp. (C) Stacked bar plot indicates the frequency of on-target genomic alterations in the validated HAP1 (n = 5) and HepG2 (n = 17) Δt deletion clones.

Because we cotransfected the CRISPR-Cas9 and the pBlueScript vector to increase cell transfection efficiency (Søndergaard et al. 2020), we aligned the Xdrop-LRS data to the pBlueScript vector and found reads mapping to sequences encoding the f1 ori, the ampicillin resistance gene, and the second ori (Supplemental Fig. S3B). These sequences serve as backbone in many commonly used plasmids, including our CRISPR-Cas9 vectors. Because we did not detect any reads mapping to the pBlueScript-specific region located between the f1 ori and the second ori, we concluded that the vector sequence that integrated into the HepG2 target region originated from the CRISPR-Cas9 instead of the pBlueScript vector.

In sum, we observed a duplication of the target region, inversion of one copy and on-target integration together with sequences from the E. coli genome and the CRISPR-Cas9 vector with a total length more than 8 kb on the same allele in the deletion clone HepG2 Δt15.

On-target genomic alterations occurred frequently

To estimate the approximate frequency of Cas9-induced genomic alterations, we tested whether on-target insertion events occurred in our other HAP1 and HepG2 Δt clones expected to carry the deletion. Because our Xdrop-LRS contig suggested an integration of genomic sequences larger than 7900 bp, we could not amplify and quantify the frequency of on-target events by PCR using primers spanning the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions. We therefore designed a pair of primers annealing inside the target region (Supplemental Fig. S3C,D). In HAP1, we inspected five HAP1 clones of which three contained the expected homozygous deletion (Fig. 3C; Supplemental Figs. S1C, S3C). The deletion clone HAP1 Δt72 and HAP1 Δt19 carried on-target genomic alterations (Supplemental Fig. S3C).

In HepG2 cells, we had validated the deletion in HepG2 Δt15 and 16 additional HepG2 clones by PCR, but still detected the target region in seven deletion clones (Fig. 3C; Supplemental Figs. S1E, S3D). In sum, aberrant genomic changes at the on-target locus occurred frequently in validated HAP1 (40%) and HepG2 (47%) deletion clones (Fig. 3C).

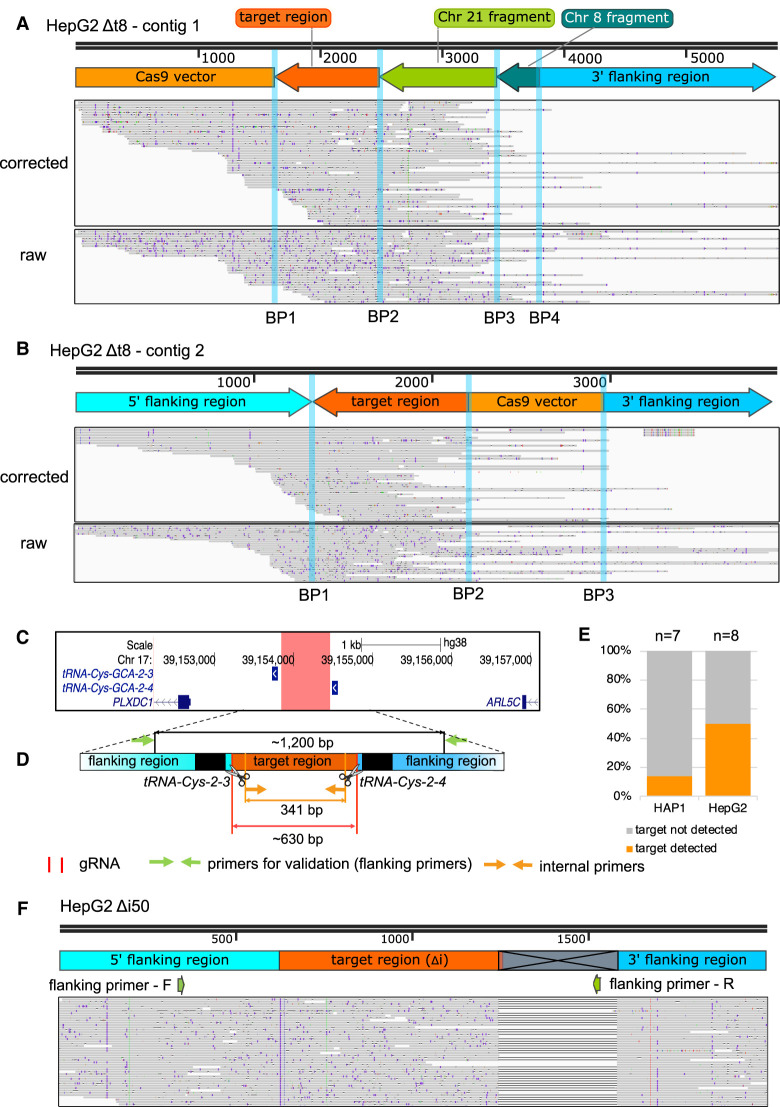

Various on-target alterations including clustered interchromosomal rearrangements co-occurred in the deletion clone HepG2 Δt8

Among the clones suspected to harbor on-target rearrangements detected by PCR, we further characterized the deletion clone HepG2 Δt8 by Xdrop-LRS. As for deletion clones HAP1 Δt72 and HepG2 Δt15, the alignment of Xdrop-LRS data to the human reference genome showed a decent coverage at the target locus (Supplemental Fig. S2B) and a similar pattern of read discontinuity at DSB sites (Supplemental Fig. S2A). By applying our customized de novo assembly-based approach, we obtained two contigs.

Contig 1 contained four breakpoints (Fig. 4A). BP1 connected the integrated CRISPR-Cas9 vector and an inverted target region-derived fragment, followed by inverted DNA fragments of 967 bp and 348 bp from Chr 21 and Chr 8 (BP2 and BP3), respectively. BP4 linked these fragments to the 3′ flanking region on Chr 17. The fragment of Chr 21 was derived from the gene body of lincRNA TCONS_I2_00017505 and the fragment of Chr 8 contained sequences mapping to truncated LINE-1 element sequences. Contig 2 consisted of three breakpoints (Fig. 4B). BP2 connected the inverted target region to the CRISPR-Cas9 vector fragment. BP1 and BP3 linked them to the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions, respectively. Alignment of both raw and corrected Xdrop-LRS reads to these contigs supported the on-target altered genomic content in the deletion clone HepG2 Δt8 (Fig. 4A,B). Detailed inspection of the integrated fragments of CRISPR-Cas9 vector revealed differences between the two contigs. In contig 1, the vector-derived fragment contained DNA sequences ranging from the puromycin resistance gene to the ampicillin resistance gene, whereas in contig 2, DNA sequences ranging from the U6 promoter to the chicken ß-actin promoter were integrated. Similar to the deletion clone HepG2 Δt15, we only found reads carrying the sequence of gRNA-Δt-1 but not gRNA-Δt-2 (Supplemental Fig. S4A).

Figure 4.

Clustered interchromosomal rearrangements, inversion of target-derived fragments, and vector integration as well as a large deletion were identified in the deletion clones HepG2 Δt8 and Δi50. (A,B) The genome browser view displays the Xdrop-LRS corrected (top) and raw (bottom) reads aligned to the de novo assembled contig 1 (A) and contig 2 (B) supporting different breakpoints (BP, blue vertical lines) within the contig. Arrows (top) show genomic orientation and approximate size of the flanking (blue) and target (dark orange) regions as well as fragments deriving from Chr 21 (light green), Chr 8 (dark green), and CRISPR-Cas9 vector (light orange) present within the contig. (C) The hg38 genome browser view shows the genomic location of the target locus (red) for the intergenic region deletion (Δi). Arrows denote the directionality of gene transcription. (D) Illustration of the design strategy for generating Δi clones. The cut sites of Cas9 (red horizontal lines and scissors), primers for validating the deletion (flanking primers, green arrows) and for detecting clones with genomic alterations (internal primers, light orange arrows) are indicated. The target region (orange) between two target tRNA genes (black) is around 630 bp in size. The size of the PCR product with flanking or internal primers in control clones is around 1200 bp or 341 bp, respectively. (E) The stacked bar plot indicates the frequency of on-target genomic alterations in the validated HAP1 (n = 7) and HepG2 (n = 8) Δi deletion clones. (F) The genome browser view displays the alignment of the Xdrop-LRS raw reads to the human reference genome (hg38) at the target locus. The large deletion is indicated in the gray crossed box. The annealing sites of the flanking primers for the validation PCR experiment are displayed with green arrows.

In sum, in the deletion clone HepG2 Δt8, we observed two contigs representing at least two alleles, including the combination of an inversion of the target region and its on-target integration together with sequences from the Chr 21 and Chr 8, as well as the CRISPR-Cas9 vector.

Adverse on-target effects were tRNA gene independent

To investigate whether the sequence similarity of the two tRNA-Cys-GCA genes caused the observed on-target genomic alterations, we repeated our dual gRNAs CRISPR-Cas9 approach in HAP1 and HepG2 cells using dual gRNAs that target the intergenic region (Δi) between our two target tRNA genes (Fig. 4C,D). This intergenic region consists of unique DNA sequences without any gene annotation, and its deletion still allows transcription of the neighboring tRNA genes because Pol III recruitment sites (A- and B-box) are located within the tRNA gene body (White 2005, 2011). For each Δi clone generated, we used primers flanking the intergenic region to validate a successful deletion event and internal primers to inspect potential genomic alterations (Fig. 4D). We validated seven HAP1 and eight HepG2 Δi deletion clones; of those one (14%) HAP1 and four (50%) HepG2 Δi deletion clones carried the genomic alterations (Fig. 4E; Supplemental Fig. S4B,C). Based on this frequency, we concluded that the sequence content of the deleted region did not cause the observed adverse on-target effects.

To better understand the on-target rearrangements, we performed Xdrop-LRS on the HepG2 Δi50 deletion clone (Supplemental Fig. S4C) by sequence enrichment of the deleted intergenic region (Supplemental Fig. S2B). We obtained high read coverage over the target region (Supplemental Fig. S2A). The alignment of the raw reads to the human reference genome suggested a 331 bp deletion at the 3′ end of the target region (Fig. 4F). This large deletion removed the binding site of the reverse primer used for identifying deletion clones, leading to a failure in detecting this genomic alteration by PCR. Notably, the deletion was located downstream of the second DSB site. Therefore, the target region itself remained still genomically intact.

Based on the characteristics of on-target events identified by Xdrop-LRS, we used three sets of PCR primers to characterize Δt and Δi deletion clones with a detectable target region (Supplemental Figs. S3C,D, S4B,C). The first primer pair detected an inversion of the target region at the 3′ DSB site. Besides the deletion clone HAP1 Δt72, only HepG2 Δt26 delivered a PCR product indicative of such an event (Supplemental Fig. S5A). The second primer pair tested for insertions, deletions, duplications, and divergent inversions of the target region at the 5′ DSB site. An insertion (1500 bp PCR product) was found in all HAP1 and HepG2 deletion clones tested. Target integration in the original genomic orientation (650 bp PCR product) and DNA fragment insertion of an unknown sequence (800 bp PCR product) at the 5′ DSB site occurred frequently in the HAP1 and HepG2 deletion clones (Supplemental Fig. S5B). The third primer pair discerned genomic alterations at the 3′ DSB site. We found multiple amplicons of varying sizes. Amplicons larger or shorter than 909 bp were indicative of an insertion or deletion around the 3′ DSB site, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S5C).

In sum, multiple alleles with different on-target genomic alterations can coexist, irrespective of the sequence content of the targeted region.

On-target genomic alterations led to functional DNA with biological consequences

We investigated potential biological consequences of the on-target genomic alterations by using several molecular and cellular assays.

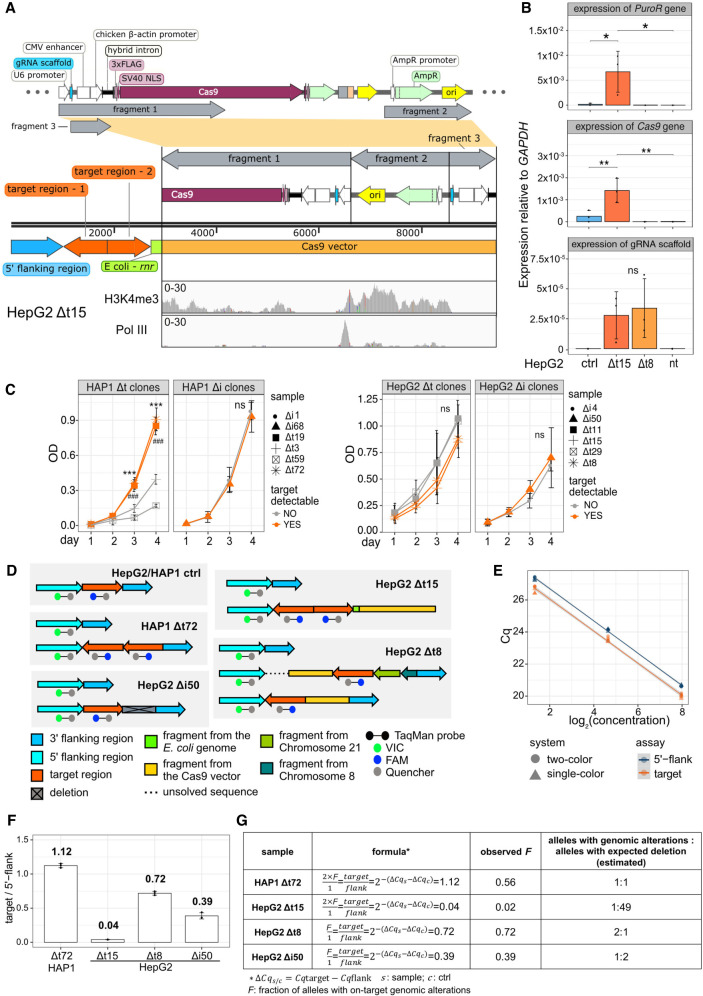

First, we inspected the impact of the integrated sequences of the CRISPR-Cas9 vector. In the deletion clone HepG2 Δt15, we found integration of three fragmented CRISPR-Cas9 vector sequences (Fig. 5A). The first fragment started from the U6 promoter to the middle of the Cas9 gene and integrated into the HepG2 genome in inverse orientation. The second started from the ampicillin resistance gene to the ori element and integrated also in inverse orientation. The third was composed of the gRNA-Δt-1 scaffold, the CMV enhancer and the chicken ß-actin promoter and integrated in the original orientation (Fig. 5A). Exogenous sequences are usually silenced through heterochromatinization (Karlin et al. 1994; Taniguchi et al. 2005; Liu et al. 2013). However, our H3K4me3 and Pol III ChIP-seq data showed that the plasmid-derived sequences were actively used in our deletion clone. Additionally, Pol III-binding to the U6 promoter gave rise to gRNA-Δt-1 (Fig. 5A). In the deletion clone HepG2 Δt15, we detected expression of the Cas9 and puromycin resistance gene as well as of the gRNA-Δt-1 and its scaffold sequence (Fig. 5B). In the HepG2 Δt8 deletion clone, only the gRNA-Δt-1 and its scaffold sequence were expressed, because the Cas9 and parts of the puromycin resistance genes were not integrated into the HepG2 genome according to our Xdrop-LRS data (Supplemental Fig. S4A). Our results confirmed that the integrated exogenous fragments were not silenced but instead were actively transcribed.

Figure 5.

Adverse on-target genomic alterations affected cell growth, promoted active transcription, and varied in abundance among deletion clones. (A) Illustration of the different CRISPR-Cas9 vector sequences (fragment 1–3, top) that integrated in the HepG2 Δt15 deletion clone (middle). The orientation of integration is shown. Coverage tracks (bottom) show mapping of histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) and RNA polymerase III (Pol III) ChIP-seq data to the integrated CRISPR-Cas9 vector sequences. (B) Bar graphs display expression levels of genes that integrated in the deletion clones HepG2 Δt15 and Δt8. HepG2 nontargeting clones (ctrl) as well as nontransfected (nt) cells were used as controls. Expression levels were normalized to GAPDH gene expression and determined by qPCR (n = 3, mean ± SD). Statistics: one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey HSD test. Significance codes: (*) P < 0.05, (**) P < 0.01, ns: not significant. (C) Line graphs show the relative number of cells (measured by optical density, OD) cultured over 4 d after seeding and measured by the crystal violet assay (n = 3, mean ± SD). Statistics: one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test. Significance code: P < 0.001 (*** and ### when compared with the HAP1 Δt3 or Δt59 deletion clone, respectively); ns, not significant. (D) The design of the TaqMan assay applied in control and deletion clones is illustrated. Allelic on-target genomic alteration based on Xdrop-LRS are shown for each clone. (E) The dot plot shows the quantification cycle (Cq) using genomic template DNA from the HAP1 control clone at increasing concentrations. Both the one-color (circle) and the two-color (triangle) system were tested in the two TaqMan assays, detecting either the target region (orange) or the 5′ flanking region (dark blue). Linear models were built for each assay. (F) The bar plot displays the ratios (normalized signals) between the number of molecules containing the target and the 5′ flanking regions in the deletion clones HAP1 Δt72 and HepG2 Δt15, Δt8, Δi50. The numbers on the top of the bars display the ratio. (G) The table contains the formula used to calculate the fraction (F) of alleles carrying the intact target region from the PCR quantification cycle (Cq) and the estimated ratios between the alleles with an on-target genomic aberration and expected deletion based on the F values for each deletion clone and experiment. The cell type origin was considered when calculating ΔCqs−ΔCqc, whereby the deletion clone HAP1 Δt72 was normalized to the HAP1 control clone, whereas deletion clones HepG2 Δt15, Δt8, Δi50 were normalized to the HepG2 control clone.

Second, we measured cell proliferation in the HAP1 and HepG2 Δt and Δi deletion clones with and without a detectable genomic on-target effect. The deletion clones HAP1 Δt72 and Δt19 with on-target genomic alterations grew significantly faster than the bona fide deletion clones HAP1 Δt3 and Δt59. In contrast, the cell proliferation rate was nearly identical in the HAP1 Δi as well as in the HepG2 Δt and HepG2 Δi deletion clones (Fig. 5C). The proliferative advantage gained in some cell clones could explain why frequencies of detectable target regions varied in the HAP1 Δt (2/5) and Δi (1/7), but not in the HepG2 Δt (8/17) and Δi (4/8) deletion clones (Figs. 3C, 4E).

Third, we performed a two-color TaqMan-qPCR assay to obtain ratios between alleles with on-target alterations and expected deletion (Fig. 5D). We tested the TaqMan assay robustness by using increasing concentrations of the template DNA and found negligible differences between the single- and two-color system (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, we established linear relations between the quantification cycle (Cq) and the template DNA concentration for the assayed regions (Fig. 5E). Based on the ratio between the signals from 5′ flanking region and the target region (Fig. 5D), we calculated the fraction of alleles carrying on-target genomic alterations (Fig. 5F,G). By considering the possible ploidy status and the fact that the number of alleles is an integer, we estimated that the ratio of the alleles with and without on-target genomic rearrangements is 1:1 for deletion clone HAP1 Δt72, 1:49 for HepG2 Δt15, 2:1 for HepG2 Δt8 and 1:2 for HepG2 Δi50 (Fig. 5G).

In conclusion, local genomic rearrangements can lead to unwanted activation of gene expression and changes in cellular behavior, which can compromise the reliability of cell growth-dependent readouts commonly used in large-scale Cas9 screening. Our data therefore underscore the necessity to investigate potential on-target effects of Cas9-mediated deletion.

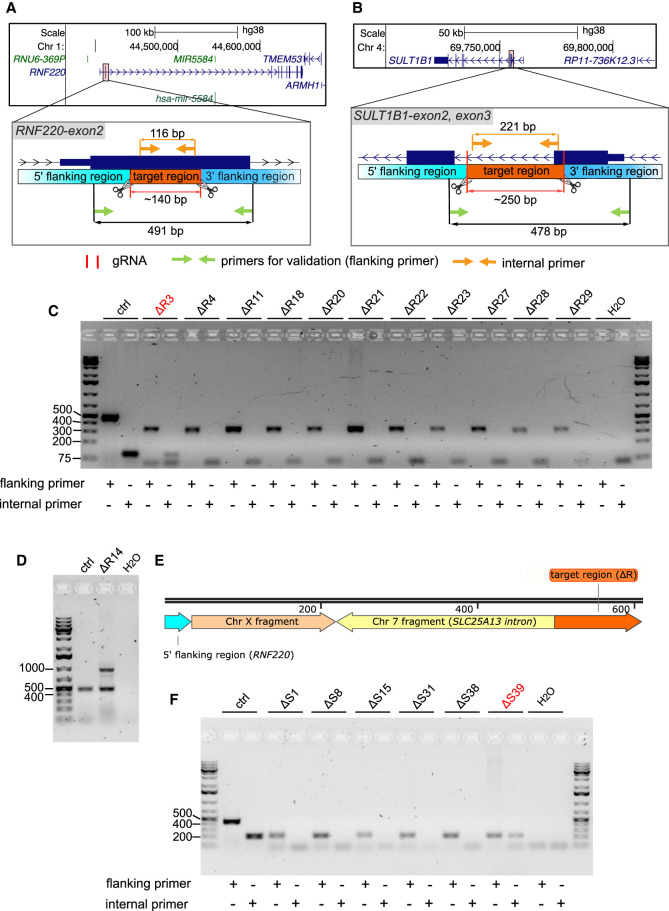

CRISPR-Cas9-gRNA RNP delivery induced adverse on-target effects in protein-coding genes

To test whether the location of the target region and the CRISPR-Cas9 delivery system affected the occurrence of on-target aberrations, we targeted two protein-coding genes, RNF220 (located on Chr 1) and SULT1B1 (located on Chr 4) in hTERT-immortalized retinal pigment epithelial cells (hTERT-RPE1) by using the CRISPR-Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) system (Fig. 6A,B).

Figure 6.

Adverse on-target genomic rearrangements occurred using the CRISPR-Cas9-gRNA delivery system. (A,B) The hg38 genome browser views (top) show the genomic locations of two protein-coding genes (RNF220 and SULT1B1). Arrows denote directionality of gene transcription. The CRISPR-Cas9-gRNA RNP targeted regions (bottom) are magnified and highlighted (orange). Cas9 cut sites (red horizontal lines and scissors), primers used for validation (flanking primers, green arrows) and for detecting target regions (internal primers, light orange arrows) are marked. The lengths of the target regions and the predicted PCR amplicons are indicated. (C) The agarose gel image distinguishes the size of PCR products generated by flanking primers to validate the deletion within the RNF220 (ΔR) gene in hTERT-RPE1 cell clones and by internal primers to detect hTERT-RPE1 clones with on-target alterations. hTERT-RPE1 clones with a confirmed deletion but also with a detectable target region are highlighted (red). Selected DNA marker bands (in bp) are depicted. (D) The agarose gel image separates the size of PCR products formed by flanking primers in a hTERT-RPE1 control (ctrl) clone (491 bp) and deletion clone ΔR14 (491 bp and ∼1000 bp). (E) The illustration depicts the composition of the extra band (∼1000 bp) in the deletion clone hTERT-RPE1 ΔR14 revealed by Sanger sequencing. The arrows show the genomic orientation and approximate size. (F) PCR-based validation in hTERT-RPE1 deletion clones as described in Figure 4C in which the SULT1B1 (ΔS) gene was modified.

For impairing the RNF220 gene (ΔR), we deleted a 116 bp region located in the second exon (Fig. 6A). Of the eleven validated ΔR deletion clones, we obtained one clone (ΔR3) that carried a potential on-target rearrangement (Fig. 6C). We found an additional heterozygous clone ΔR14 carrying one allele with an undeleted target region and another allele with an unexpected rearrangement. This rearrangement encompassed insertions of DNA fragments deriving from Chr X (truncated LINE-1 element sequence) and Chr 7 (intronic SLC25A13 gene sequence) (Fig. 6D,E), as observed in deletion clone HepG2 Δt8 (Fig. 4A,B). For the second gene SULT1B1 (ΔS), we targeted a 221 bp long region (ΔS) (Fig. 6B) and found six validated deletion clones. However, traces of the targeted sequence were still detectable in deletion clone ΔS39, hinting at another unexpected genomic aberration (Fig. 6F).

In summary, on-target genomic aberrations can occur frequently at different genomic locations and in different cell lines, irrespective of the delivery methods of the CRISPR-Cas9 system used.

Discussion

We revealed the co-occurrence of multiple complex genomic on-target alterations in cell clones after CRISPR-Cas9 induced cleavage. Genomic rearrangements after CRISPR-Cas9 editing have been documented, such as the targeted chromosome loss (Zuccaro et al. 2020), aneuploidy (Rayner et al. 2019; Nahmad et al. 2022), chromosome translocation because of off-target editing (Liu et al. 2021), as well as the large deletion, inversion, or duplication of the target region (Li et al. 2015; Shin et al. 2017; Kosicki et al. 2018; Shou et al. 2018; Owens et al. 2019). However, the complexity of diverse on-target genomic alterations coinciding on the same allele has not been fully addressed owing to technical limitations. Conventional methods to detect genomic alterations, such as PCR and Sanger sequencing or fluorescence in situ hybridization, are laborious and require prior knowledge to design primers/probes. Those methods will miss on-target events, including clustered interchromosomal rearrangements or exogenous sequence insertions. To overcome these limitations, powerful tools detecting CRISPR-Cas9 outcomes have been developed (Frock et al. 2015; Yin et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2021; Turchiano et al. 2021), but it remains extremely challenging to reveal co-occurrent aberrations in the order of kilobases as a result of input DNA fragmentation and/or PCR-mediated enrichment. Xdrop-LRS coupled with de novo assembly or similar unbiased sequencing methods (Blondal et al. 2021) is a powerful approach to confirm CRISPR-Cas9 editing events. Relative to other target enrichment methods, Xdrop-LRS requires less input DNA and has better recovery rates (Blondal et al. 2021), but is limited in detecting large-scale rearrangements within one or several chromosomes (chromothripsis), aneuploidy or Cas9 off-targeting events.

This study showed that our data-driven and assumption-free Xdrop-LRS approach provides an additional layer of insurance against the confounding effects of unexpected allelic outcomes, such as endogenous and exogenous DNA fragment integrations, including clustered interchromosomal rearrangements. Although the exact chronological order of events that occurred in our deletion clones cannot be reconstructed, we propose hypothetical models of the on-target genomic scenarios in our deletion clones based on our data (Supplemental Fig. S6A). We reasoned that the deletion clone HAP1 Δt72 was heterogenous for the on-target genomic alterations. HAP1 is a near-haploid cell line but the haploid state is unstable and cells tend to become diploid over time or under stress (Olbrich et al. 2017). We speculate that the target-derived fragments were cleaved from each of the two alleles in a diploid mother cell. If the resulting DSB is not repaired before cell division, the cleaved fragments can be distributed randomly (Leibowitz et al. 2021). One daughter cell (DC1) of deletion clone HAP1 Δt72 could have used NHEJ to repair the DSBs resulting in the expected deletion, although the second daughter cell (DC2) would have used MMEJ leading to the ligation and inversion of the two fragments at the original cut site during the repair process (Li et al. 2015; Shou et al. 2018). Although cleaved DNA fragments can circularize (Møller et al. 2018), our PCR results and Xdrop-LRS data showed that the duplicated target regions were connected to the flanking regions, suggesting genomic insertion of the deleted fragments, rather than extrachromosomal circular DNA formation. Cells arising from DC1 and DC2 formed a heterogenous cell population explaining why, despite the duplication, ChIP-seq signals of Pol III and H3K4me3 over the target region were lower in cells deriving from the HAP1 Δt72 deletion clone when compared with the control clone (Fig. 1C). Over time, cells with the on-target genomic aberration may dominate owing to a selective advantage (Fig. 5C).

Similarly, we consider that the deletion clone HepG2 Δt15 was heterogenous. HepG2 has a hyperploid karyotype with trisomy of Chr 17 (Zhou et al. 2019). Therefore, we speculate that two of the target-derived fragments together with other exogenous sequences were inserted into one of the three alleles in one daughter cell (DC2) whereas the other daughter cell contained three alleles with the expected deletion (DC1). The genomic alterations likely affected cell proliferation, and the number of cells carrying alleles with the on-target aberrations decreased rapidly (Fig. 5G; Supplemental Fig. S6A). This may explain why HepG2 Δt15 cells, in which an estimated 2% of all alleles contain an on-target genomic aberration, tended to grow slower than the clone with the expected deletion (Fig. 5C). The inserted fragment originating from the E. coli genome could have been a remnant from plasmid purifications, but we were unable to visualize any DNA indicative of such contamination (Supplemental Fig. S2D).

In the deletion clone HepG2 Δt8, we reason that two alleles represent the two contigs identified with Xdrop-LRS data (Fig. 4A,B), whereas a third allele carried the expected deletion. This model is in accordance with our TaqMan assay data (Fig. 5G; Supplemental Fig. S6A). Notably, we found endogenous fragments from other chromosomes integrated at the target site (Fig. 4A). We ruled out that these rearrangements were caused by de novo insertion from a reverse-transcribed RNA (Kosicki et al. 2018) or translocations induced by Cas9 off-targeting at different chromosomal regions (Liu et al. 2021) because our gRNAs had very high on-target sequence specificity, and no sequence similarity between the gRNA and the chromosomal break sites was found. Instead, we suspected that this contig was the result of chromothripsis as it has been shown in the single gRNA system (Leibowitz et al. 2021). Upon chromothripsis, chromosomes are fragmented and then configured in a random order (Stephens et al. 2011; Ly et al. 2017), matching the molecular signatures of clustered interchromosomal rearrangements found in the HepG2 Δt8 deletion clone.

In the deletion clone HepG2 Δi50, we postulate that the detected large genomic deletion resided on one allele whereas the two other alleles carried the expected deletion (Figs. 4F, 5G; Supplemental Fig. S6A). Such deletions can occur at different genomic loci and in many cell lines with various frequency (Shin et al. 2017; Kosicki et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2021; Wen et al. 2021). Because the size of the large deletion is atypical for the NHEJ repair machinery (van Overbeek et al. 2016; Guo et al. 2018a), other repair mechanisms such as MMEJ could play a role (Owens et al. 2019; Roidos et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2021). However, we did not find evidence for sequence microhomology at the breakpoint junction necessary for MMEJ (Supplemental Fig. S6B). Overall, our findings show the complexity of DNA damage repair mechanism after Cas9-induced DSBs, as well as limitations in predicting and validating genomic editing outcomes.

We propose a cost-effective pipeline to screen for deletion clones when using the dual gRNA system. First, flanking primers in PCR assays are designed to screen for clones with the expected amplicon size visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis and confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figs. 1B, 4D). Second, internal primers amplifying a genomic region located within the target region are used in PCR followed by agarose gel electrophoresis, quantitative PCR (qPCR) or droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) (Fig. 4D; Supplemental Figs. S3C,D, S4B,C). Third, to characterize the exact content of the target and flanking sequences, Xdrop-LRS or similar unbiased methods should be used to confirm cell clones that will be used further for biological studies.

In conclusion, our findings show new instances of unintended on-target CRISPR-Cas9 editing events co-occurring on the same alleles, which can be easily overlooked, and profoundly affect mechanistic interpretations when the genomically inserted sequences remain functional. Furthermore, we introduced Xdrop-LRS coupled with de novo assembly-based approach as a powerful and data-driven tool to investigate and validate the outcomes of Cas9 modification in the genome.

Methods

Cell culture

HAP1 cells were obtained from Horizon Discovery and grown in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco Medium (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (Hyclone) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). HepG2 and hTERT-RPE1 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin. Cells were cultured in T75 flasks at 37°C and 5% atmospheric CO2. HAP1 and hTERT-RPE1 were propagated by splitting 1/10 every 2 d, and HepG2 cells were expanding by splitting 1/4 every 3 d. Upon splitting, after the medium was aspirated, cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (Sigma-Aldrich) and detached with 2 mL of a trypsin-EDTA solution (Sigma-Aldrich). Trypsin was subsequently inactivated with a minimum of threefold surplus of culture medium before a cell fraction was passaged. Both cell lines have a certified genotype.

Plasmid construction

gRNAs were designed and assessed using the design tool from the Zhang lab (https://zlab.bio/guide-design-resources). Each gRNA (Supplemental Table S1) was separately cloned into the two BbsI restriction sites of pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro (px459) (Ran et al. 2013).

Transfection and generation of single cell-derived clones

To enhance transfection efficiency, the short-size pBlueScript vector was cotransfected with large-size CRISPR-Cas9 vectors (Søndergaard et al. 2020). For generating HAP1 and HepG2 deletion clones, two CRISPR-Cas9 vectors (Cas9-gRNA-1 and -2) were used. For creating nontargeting control clones (ctrl), no gRNA sequence was cloned into the CRISPR-Cas9 vector. Nontransfected (nt) cells served as additional controls. About 160,000 HAP1 cells per well were plated in a 6-well plate and on the next day transfected using TurboFectin 8.0 (OriGene), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Roughly 100,000 HepG2 cells were electroporated using the NEON electroporation system (Invitrogen), as previously described (Søndergaard et al. 2020). After 24 h (HAP1) to 48 h (HepG2), cells were then selected by adding 2 µg/mL puromycin to the cell culture medium for 2 d. Afterward, cells were allowed to recover in normal medium. Single-cell clones were hand picked, grown, and expanded.

Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoproteins delivery and single cell-derived clones

Cas9 nuclease (Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease V3), gRNA and fluorescent trcRNA (Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 tracrRNA) were purchased from IDT. trcRNAs (0.055 µL of 200 µM stock per reaction) and gRNAs (0.055 µL of 200 µM stock per reaction) were first assembled by incubating at 95°C for 5 min. The assembled RNAs were mixed with Cas9 protein (0.15 µL of 62 µM stock per reaction). On transfection, roughly 500,000 hTERT-RPE1 cells were electroporated using the NEON system, together with the Cas9-gRNA mixture prepared beforehand and 0.216 µL of 100 µM transfection enhancer (Alt-R Cas9 Electroporation Enhancer, cat. 1075915). The Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoproteins complex and hTERT-RPE1 cells were pulsed three times at 1600 V for 20 ms. After 24 h incubation and recovery, live cells as singlets with fluorescence were sorted into 96-well plates and expanded.

Genomic DNA extraction

HAP1 and HepG2 cells were lysed in 400 µL lysis buffer (0.5% SDS, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.05 M EDTA, 0.01 M Tris HCl, 200 µg/mL Proteinase K) and incubated at 55°C overnight. After this, 200 µL of 5 M NaCl were added, and the samples were vortexed and incubated on ice for 10 min. After centrifugation (15,000×g, 4°C, 10 min), 400 µL of the supernatant were transferred to a new tube, mixed with 800 µL of 100% EtOH and incubated on ice for at least 10 min. Genomic DNA was pelleted by centrifugation (18,000×g, 4°C, 15 min), subsequently washed once with 70% EtOH and resuspended in nuclease-free water.

hTERT-RPE1 cells were lysed in DirectPCR Lysis Reagent (Cell) (Nordic Biosite), according to the manufacturer's manual. Briefly, 2× diluted lysis buffer with 0.3 mg/mL Proteinase K was added to the cell and incubated at 55°C for 6–8 h and at 85°C for 45 min.

Primer design

Primers (Supplemental Table S1) were designed using NCBI Primer-BLAST (Ye et al. 2012) with default parameters (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/index.cgi?LINK_LOC=BlastHome). To ensure primer sequence specificity, we chose “Genomes for selected organisms” and “Homo Sapiens.” Primers with the highest specificity and GC-content of 40%–60% were selected.

PCR for genotyping

PCR was performed with Taq polymerase PCR (New England Biolabs), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 100–1000 ng of genomic DNA or 2 µL of lysed cells were used as template DNA. The 25 µL PCR reaction consisted of 1× standard Taq reaction buffer, 200 µM dNTPs, 0.2 µM primers (Supplemental Table S1), and 1U Taq DNA polymerase. After thorough mixing of the PCR reaction, the subsequent PCR was performed using an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles at 95°C for 30 sec, at 55°C–60°C for 30 sec, at 68°C for 60 sec per 1 kb and a final extension step at 68°C for 5 min in a thermocycler (Applied Biosystems) with preheated lids. All PCR reactions were held at 4°C. The size of PCR products was assessed by electrophoresis using a 1.2% agarose gel.

Sanger sequencing

The PCR band indicative of the homozygous deletion (320 bp in deletion clones HAP1 and HepG2) or on-target genomic alterations (∼1000 bp in deletion clone hTERT-RPE1 ΔR14) was excised from the agarose gel and purified using Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit (Zymo Research), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purified DNA (75–150 ng) and the flanking sequence-specific primers (Supplemental Table S1) were sent for Sanger sequencing (Eurofins, Mix2Seq). Chromatograms and the analysis files are available under Supplemental Files. For the homozygous clones, the sequences obtained from Sanger sequencing were compared with the reference genome using the multiple sequence alignment tool T-Coffee with ClustalW parameters (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/tcoffee/) (Notredame et al. 2000).

TaqMan-qPCR

The TaqMan assays (Supplemental Table S1) were designed with Thermo Fisher Scientific Custom TaqMan Assay Design Tool (https://www.thermofisher.com/order/custom-genomic-products/tools/gene-expression/), according to the manufacturer's guidelines (https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/LSG/manuals/cms_042307.pdf). The TaqMan-qPCR was performed in 384-well plates with 10 µL system by mixing 5 µL TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix, 0.5 µL of each TaqMan assay (1 µL in total), 3 µL of nuclease-free water and 1 µL of high-quality, RNA-free genomic DNA. To test efficiency, genomic DNA extracted from the HAP1 control clone was used at three concentrations (250 ng/µL, 25 ng/µL, and 2.5 ng/µL). After testing efficiency, the actual assay was performed using 20 ng–40 ng genomic DNA in each reaction. The TaqMan qPCR was run on QuantStudio 5 with its prebuilt program: Quantification-TaqMan, Standard Curve, Fast. The ratios between molecules containing the target region and 5′ flanking region were normalized to the control clone for each cell type and the observed percentage of the alleles with the on-target genomic alterations were calculated, taking into account cell ploidy.

RNA extraction and DNase-treatment

Cells were harvested at 80%–90% confluency in 6 cm dishes. Cells were put on ice and 700 µL QIAzol (QIAGEN) were directly added onto the cells. Cells were scraped, mixed properly with QIAzol and collected in 1.5 mL tubes (Eppendorf). Afterward, 140 µL chloroform were added. The mixture was shaken for 30 sec and incubated for 2.5 min at room temperature, before centrifugation at 9000×g at 4°C for 5 min. After phase separation by centrifugation, the upper aqueous phase was carefully transferred in a new tube and mixed with 1 volume isopropanol. The tubes were inverted 5 times, followed by 10 min incubation at room temperature. The RNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 9000×g at 4°C for 10 min. The pellet was washed carefully once using 700 µL ice-cold 70% ethanol. The RNA was resuspended in 30–50 µL nuclease-free water. RNA concentration and purity were determined by NanoDrop (NanoDrop 2000c). Afterward, 6 µg RNA were mixed with 5 µL 10 × TurboDNase buffer (Invitrogen), 1 µL TurboDNase (Invitrogen), 1 µL RNase Inhibitor (RiboLock, Invitrogen), and water was added to a total volume of 50 µL and subsequently incubated at 37°C for 30 min. DNase-treated RNA was purified with the Zymo RNA Clean & Concentrator Kit (Zymo Research) and eluted in 13 µL nuclease-free water. The concentration was determined by NanoDrop.

cDNA synthesis and qPCR

5 µg of purified total RNA were mixed with 1 µL random primers (250 ng/µL) and 1 µL dNTP Mix (10 mM each, Thermo Fisher Scientific) to a final volume of 12 µL. The mixture was incubated in a thermocycler at 65°C for 5 min and then quickly chilled on ice. Afterward, 1 µL RNase-Inhibitor (RiboLock, Invitrogen), 4 µL 5× First-Strand Buffer (Invitrogen) and 2 µL 0.1 M DTT (Invitrogen) were added. After incubation at 25°C for 2 min, 1 µL SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) was added. Samples were incubated in the thermocycler at 25°C for 10 min, at 42°C for 50 min, at 70°C for 15 min and held at 4°C. After cDNA synthesis, 0.4 µL of E. coli RNase H (2 units) were used for digestion and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. Zymo DNA Clean & Concentrator Kit (Zymo Research) was used to purify cDNA.

The cDNA for qPCR was diluted to 1 ng/µL with nuclease-free water. The qPCR was conducted in 384-well plates with 10 µL system, containing 5 µL SYBR-Green Mix (PowerUp), 1 µL of primer, 1 µL of template and 3 µL of nuclease-free water. The qPCR was run on a Real-Time-PCR machine (QuantStudio 5) at 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min, 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 sec and at 60°C for 1 min. A melting curve was added (at 5°C for 15 sec, at 60°C for 1 min with ramp rate 1.6°C/sec and at 95°C for 15 sec with ramp rate 0.075°C/sec). Gene expression levels of each target were normalized to the expression of GAPDH. Three technical replicates were used for each sample per target, and three biological replicates were included to calculate the mean and standard derivation.

Crystal violet assay

About 1000 HAP1 or 5000 HepG2 cells were seeded into 96-well plates in six technical replicates. Cells were assayed daily from day 1 to day 4. For the measurement, the medium was aspirated and carefully washed with 1 × PBS twice. For staining, 100 µL of 0.5% crystal violet solution (1% aqueous solution, diluted with water) (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to each well. After 1 min incubation at room temperature, the staining solution was removed. Each well was carefully washed 4–6 times with water to completely remove the unbound staining solution. After the wash, 100 µL of 10% acetic acid diluted in water (Fisher Scientific, AR grade) were used to dissolve the stain. The mixture was transferred to a new 96-well plate, and the absorption at 570 nm was measured on a plate reader (Spectramax i3x, Molecular Devices). Wells without cells were included in the assay as blank control. Background values were subtracted from the obtained values of optical density (OD). Three biological replicates were included to calculate the mean and standard deviation.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq)

ChIP-seq experiments were performed as previously described (Rudolph et al. 2016). Briefly, HAP1 and HepG2 cells were fixed in 1% formaldehyde, lysed, sonicated, and then incubated with Pol III antibodies recognizing antigen POLR3A (Kutter et al. 2011) or H3K4me3 antibodies (05-1339, Millipore-Sigma). Immunoprecipitated DNA was used to generate sequencing libraries using the Takara SMARTer ThruPLEX DNA-seq Kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. Library size distribution and quality were assessed by an Agilent Bioanalyzer instrument using high-sensitivity DNA chips. The KAPA-SYBR FAST qPCR kit (Roche) was used to quantify the libraries. The sequencing run was performed with the NextSeq 500/550 High Output v2 kit (Illumina) for 81 cycles, single-end on an Illumina NextSeq 500 platform.

ChIP-seq data analysis

The Pol III ChIP-seq data for HepG2 unmodified cells were downloaded from ArrayExpress (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/arrayexpress) under accession number E-MTAB-4046. The qualities of reads were assessed using FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Reads were aligned to the human reference genome hg38 using BWA (Li and Durbin 2009). PCR duplicates and reads mapping to the ENCODE blacklist (https://sites.google.com/site/anshulkundaje/projects/blacklists) were removed using SAMtools (Li et al. 2009) and NGSUtils (Breese and Liu 2013). bedGraph files were generated using deepTools (Ramírez et al. 2016). UCSC (http://genome.ucsc.edu) (Kent et al. 2002) or the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) (Robinson et al. 2011) was used for visualization of the genomic loci or BAM and bedGraph files. To avoid multimapping issues, we only considered reads with a mapping quality higher than 30 when inspecting peaks located at the target region. For aligning reads to the assembled contigs or the plasmids, BWA (Li and Durbin 2009) was used for read mapping, followed by extraction of nonsoft clipped reads with SAMtools (Li et al. 2009).

Xdrop

High-molecular-weight genomic DNA from the deletion clones HAP1 Δt72 as well as HepG2 Δt15, Δt8, and Δi50 was extracted using Quick-DNA kit (Zymo Research) and shipped to Samplix Services (Denmark) for Xdrop DNA enrichment followed by Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) long-read sequencing (LRS) (Madsen et al. 2020; Blondal et al. 2021). Briefly, the Xdrop target enrichment workflow allow capture and enrichment of a region of interest of up to 100 kb by targeting a short detection sequence. For the enrichment of the specific target region, detection primers were designed using the online primer design tool from Samplix to target a 120 bp detection sequence approximately mid-way between the Cas9 cut sites. At Samplix services, DNA quality was checked using the TapeStation System (Agilent Technologies Inc.) with the Genomic DNA ScreenTape, according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was further purified using HighPrep PCR Clean-up Bead System, according to the manufacturer's instructions (MAGBIO Genomics) with the following changes: Bead-to-sample ratios were 1:1 (v:v) and elution was performed by heating the sample in the elution buffer at 55°C for 3 min before separation on the magnet. The samples were eluted in 20 µL 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8). Purified DNA samples were quantified by Quantus Fluorometer (Promega Inc.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR reagents, primers, as well as 4–10 ng purified DNA of each sample, were partitioned in droplets and subjected to droplet PCR (dPCR) using the detection primers (see above). The dPCR droplets were then sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). The isolated droplets were broken, and DNA was again partitioned in droplets and amplified by multiple displacement amplification in droplets (dMDA) reactions. After amplification, DNA was isolated and quantified. The MinION sequencing platform from ONT was used to generate LRS data from the dMDA samples, as described by the manufacturer's instructions (Premium whole genome amplification protocol SQK-LSK109) with the Native Barcoding Expansion 1–12 (EXP-NBD104) and 13–24 (EXP-NBD114)). In short, 1.5 µg amplified DNA of each sample was treated with T7 Endonuclease I, followed by size selection, end repair, barcoding, and adaptor ligation. After library generation, samples were loaded onto a MinIon flow cell 9.4.1 (20 fmol) and run for 16 h under standard conditions, as recommended by the manufacturer (Oxford Nanopore Inc.). Generated raw data (FAST5) was subjected to base-calling using Guppy v. 3.4.5 with high accuracy and quality filtering to generate FASTQ sequencing data.

Xdrop data analysis

FASTQ reads were first corrected using Canu (Koren et al. 2017), followed by SACRA (Kiguchi et al. 2021) to further identify and split chimeric reads. Reads were aligned to either the human reference genome (hg38) or the region of interest with minimap2 (Li 2018). For the de novo sequence assembly-based approach (Supplemental Fig. S2C), the sequences of mapped reads were extracted from FASTQ files based on the mapped read IDs with SAMtools and SeqKit (Shen et al. 2016). The de novo sequence assembly was performed with these mapped reads using Canu or Raven (Vaser and Šikić 2021). The output contigs were compared and assessed by pairwise alignment with Needle (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/psa/emboss_needle/), MegaBLAST against NCBI standard database of nucleotide collection (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and manual inspection of the read alignment quality and coverage to the assembled contigs. If the flanking sequence of the target region needed to be extended, reads mapping to the 5′ or 3′ end of the contig were used for the second round of a de novo sequence assembly. If the read coverage was lower than the requirement of the assemblers, a manual extension was required. To do so, the soft clipped sequences of the reads mapping to the 5′ or 3′ end of the contig were visualized in IGV, manually compared and summarized. After the contig was successfully assembled, both corrected reads (using Canu and SACRA corrections) and raw reads were aligned to the contig. If there were more than one contig assembled for one sample, the contigs were merged into one de novo genomic reference to enhance the accuracy of the alignment. The contigs were assessed by visualization of aligned reads supporting breakpoints of the contig using IGV. ChIP-seq reads aligning to the contigs were used to assess and polish the contig. The finalized contigs are available as Supplemental Files.

Software availability

Scripts used for bioinformatics analyses to reproduce the results are available as Supplemental Code and at GitHub (https://github.com/KeyiG/Cas9_ontarget_alteration.git).

Data access

All raw and processed sequencing data generated in this study have been submitted to ArrayExpress (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/arrayexpress), under accession numbers E-MTAB-10651 (Pol III and H3K4me3 ChIP-seq data) and E-MTAB-10652 and E-MTAB-11327 (Xdrop ONT long-read sequencing data).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the fast and thorough delivery of enrichment data and support with the data analysis by the Samplix Services team, especially Christoffer Rozenfeld. We thank the laboratories of Claudia Kutter, Marc Friedländer, and Vicent Pelechano, especially Eva Brinkman, for critical discussions and feedback. We appreciated the technical support of Daniel Whisenant, Quim Perdices, and Cristina Benito. We thank Kristoffer Sahlin, Philip Ewels, and Remi-Andre Olsen for the helpful comments regarding our data analysis, Laura Baranello for the data interpretation, and John Svetoft for the graphical design of our model. Our work benefited from the free usage of the SnapGene plasmid and contig viewer (https://www.snapgene.com/snapgene-viewer/) and free SMART Medical ART images (https://smart.servier.com). This work was supported by Chinese Scholarship Council (201700260271; K.G., C.K.), Knut & Alice Wallenberg foundation (KAW 2016.0174; C.K.), Ruth & Richard Julin foundation (2017–00358, 2018–00328, 2020-00294; C.K.), SFO-SciLifeLab fellowship (SFO_004; C.K.), Swedish Research Council (2019-05165; C.K.; 2020-01480; Y.P.S.), Lillian Sagen & Curt Ericsson research foundation (2021-00427; C.K.), Gösta Milton's research foundation (2021-00527; C.K.), Robert Lundberg's Memorial Foundation (2022-01159; K.G.) and the Swedish National Infrastructure for Computing (SNIC) at UPPMAX (storage: uppstore2018110, SNIC 2020/16-223; compute: SNIC 2017/7-154, SNIC 2017/7-261, SNIC 2020/15-292).

Author contributions: C.K. and K.G. conceptualized the project. K.G., L.G.M., L.W., A.M., M.S., Y.P.S., and J.N.S. performed the laboratory experiments. K.G. did the analysis and visualized the data. R.J.W. provided reagents. K.G. and C.K. acquired funding. K.G. and C.K. wrote the original draft. All authors contributed to the review and editing process.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article.]

Article published online before print. Article, supplemental material, and publication date are at https://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.276901.122.

Competing interest statement

K.G. received a reduction in service charge from the Samplix Xdrop Grant Program.

References

- Antoniani C, Meneghini V, Lattanzi A, Felix T, Romano O, Magrin E, Weber L, Pavani G, El Hoss S, Kurita R, et al. 2018. Induction of fetal hemoglobin synthesis by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of the human β-globin locus. Blood 131: 1960–1973. 10.1182/blood-2017-10-811505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barski A, Chepelev I, Liko D, Cuddapah S, Fleming AB, Birch J, Cui K, White RJ, Zhao K. 2010. Pol II and its associated epigenetic marks are present at Pol III–transcribed noncoding RNA genes. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 629–634. 10.1038/nsmb.1806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binda CS, Klaver B, Berkhout B, Das AT. 2020. CRISPR-Cas9 dual-gRNA attack causes mutation, excision and inversion of the HIV-1 proviral DNA. Viruses 12: 330. 10.3390/v12030330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondal T, Gamba C, Møller Jagd L, Su L, Demirov D, Guo S, Johnston CM, Riising EM, Wu X, Mikkelsen MJ, et al. 2021. Verification of CRISPR editing and finding transgenic inserts by Xdrop indirect sequence capture followed by short- and long-read sequencing. Methods 191: 68–77. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2021.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch-Guiteras N, Uroda T, Guillen-Ramirez HA, Riedo R, Gazdhar A, Esposito R, Pulido-Quetglas C, Zimmer Y, Medová M, Johnson R. 2021. Enhancing CRISPR deletion via pharmacological delay of DNA-PKcs. Genome Res 31: 461–471. 10.1101/gr.265736.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese MR, Liu Y. 2013. NGSUtils: a software suite for analyzing and manipulating next-generation sequencing datasets. Bioinformatics 29: 494–496. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canella D, Bernasconi D, Gilardi F, LeMartelot G, Migliavacca E, Praz V, Cousin P, Delorenzi M, Hernandez N, Deplancke B, et al. 2012. A multiplicity of factors contributes to selective RNA polymerase III occupancy of a subset of RNA polymerase III genes in mouse liver. Genome Res 22: 666–680. 10.1101/gr.130286.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canver MC, Bauer DE, Dass A, Yien YY, Chung J, Masuda T, Maeda T, Paw BH, Orkin SH. 2014. Characterization of genomic deletion efficiency mediated by clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 nuclease system in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 289: 21312–21324. 10.1074/jbc.M114.564625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frock RL, Hu J, Meyers RM, Ho YJ, Kii E, Alt FW. 2015. Genome-wide detection of DNA double-stranded breaks induced by engineered nucleases. Nat Biotechnol 33: 179–186. 10.1038/nbt.3101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W, Gallardo-Dodd CJ, Kutter C. 2022. Cell type–specific analysis by single-cell profiling identifies a stable mammalian tRNA–mRNA interface and increased translation efficiency in neurons. Genome Res 32: 97–110. 10.1101/gr.275944.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene EC. 2016. DNA sequence alignment during homologous recombination. J Biol Chem 291: 11572–11580. 10.1074/jbc.R116.724807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Xu Q, Canzio D, Shou J, Li J, Gorkin DU, Jung I, Wu H, Zhai Y, Tang Y, et al. 2015. CRISPR inversion of CTCF sites alters genome topology and enhancer/promoter function. Cell 162: 900–910. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T, Feng YL, Xiao JJ, Liu Q, Sun XN, Xiang JF, Kong N, Liu SC, Chen GQ, Wang Y, et al. 2018a. Harnessing accurate non-homologous end joining for efficient precise deletion in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing. Genome Biol 19: 170. 10.1186/s13059-018-1518-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Perez AA, Hazelett DJ, Coetzee GA, Rhie SK, Farnham PJ. 2018b. CRISPR-mediated deletion of prostate cancer risk-associated CTCF loop anchors identifies repressive chromatin loops. Genome Biol 19: 160. 10.1186/s13059-018-1531-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hård J, Mold JE, Eisfeldt J, Tellgren-Roth C, Häggqvist S, Bunikis I, Contreras-Lopez O, Chin C-S, Rubin C-J, Feuk L, et al. 2021. Long-read whole genome analysis of human single cells. bioRxiv 10.1101/2021.04.13.439527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Karlin, S, Doerfler W, Cardon LR. 1994. Why is CpG suppressed in the genomes of virtually all small eukaryotic viruses but not in those of large eukaryotic viruses? J Virol 68: 2889–2897. 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2889-2897.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D. 2002. The Human Genome Browser at UCSC. Genome Res 12: 996–1006. 10.1101/gr.229102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiguchi Y, Nishijima S, Kumar N, Hattori M, Suda W. 2021. Long-read metagenomics of multiple displacement amplified DNA of low-biomass human gut phageomes by SACRA pre-processing chimeric reads. DNA Res 28: dsab019. 10.1093/dnares/dsab019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. 2017. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res 27: 722–736. 10.1101/gr.215087.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosicki M, Tomberg K, Bradley A. 2018. Repair of double-strand breaks induced by CRISPR–Cas9 leads to large deletions and complex rearrangements. Nat Biotechnol 36: 765–771. 10.1038/nbt.4192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft K, Geuer S, Will AJ, Chan WL, Paliou C, Borschiwer M, Harabula I, Wittler L, Franke M, Ibrahim DM, et al. 2015. Deletions, inversions, duplications: engineering of structural variants using CRISPR/Cas in mice. Cell Rep 10: 833–839. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutter C, Brown GD, Gonçalves Å, Wilson MD, Watt S, Brazma A, White RJ, Odom DT. 2011. Pol III binding in six mammals shows conservation among amino acid isotypes despite divergence among tRNA genes. Nat Genet 43: 948–955. 10.1038/ng.906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz ML, Papathanasiou S, Doerfler PA, Blaine LJ, Sun L, Yao Y, Zhang CZ, Weiss MJ, Pellman D. 2021. Chromothripsis as an on-target consequence of CRISPR–Cas9 genome editing. Nat Genet 53: 895–905. 10.1038/s41588-021-00838-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. 2018. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34: 3094–3100. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25: 1754–1760. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. 2009. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Shou J, Guo Y, Tang Y, Wu Y, Jia Z, Zhai Y, Chen Z, Xu Q, Wu Q. 2015. Efficient inversions and duplications of mammalian regulatory DNA elements and gene clusters by CRISPR/Cas9. J Mol Cell Biol 7: 284–298. 10.1093/jmcb/mjv016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Campagna M, Qi Y, Zhao X, Guo F, Xu C, Li S, Li W, Block TM, Chang J, et al. 2013. Alpha-interferon suppresses hepadnavirus transcription by altering epigenetic modification of cccDNA minichromosomes. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003613. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Zhang W, Xin C, Yin J, Shang Y, Ai C, Li J, Meng FL, Hu J. 2021. Global detection of DNA repair outcomes induced by CRISPR–Cas9. Nucleic Acids Res 49: 8732–8742. 10.1093/nar/gkab686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly P, Teitz LS, Kim DH, Shoshani O, Skaletsky H, Fachinetti D, Page DC, Cleveland DW. 2017. Selective Y centromere inactivation triggers chromosome shattering in micronuclei and repair by non-homologous end joining. Nat Cell Biol 19: 68–75. 10.1038/ncb3450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddalo D, Manchado E, Concepcion CP, Bonetti C, Vidigal JA, Han YC, Ogrodowski P, Crippa A, Rekhtman N, de Stanchina E, et al. 2014. In vivo engineering of oncogenic chromosomal rearrangements with the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Nature 516: 423–427. 10.1038/nature13902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen EB, Höijer I, Kvist T, Ameur A, Mikkelsen MJ. 2020. Xdrop: targeted sequencing of long DNA molecules from low input samples using droplet sorting. Hum Mutat 41: 1671–1679. 10.1002/humu.24063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM. 2013. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 339: 823–826. 10.1126/science.1232033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour MR, Abraham BJ, Anders L, Berezovskaya A, Gutierrez A, Durbin AD, Etchin J, Lee L, Sallan SE, Silverman LB, et al. 2014. An oncogenic super-enhancer formed through somatic mutation of a noncoding intergenic element. Science 346: 1373–1377. 10.1126/science.1259037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVey M, Lee SE. 2008. MMEJ repair of double-strand breaks (director's cut): deleted sequences and alternative endings. Trends Genet 24: 529–538. 10.1016/j.tig.2008.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller HD, Lin L, Xiang X, Petersen TS, Huang J, Yang L, Kjeldsen E, Jensen UB, Zhang X, Liu X, et al. 2018. CRISPR-C: circularization of genes and chromosome by CRISPR in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res 46: e131. 10.1093/nar/gky767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moqtaderi Z, Wang J, Raha D, White RJ, Snyder M, Weng Z, Struhl K. 2010. Genomic binding profiles of functionally distinct RNA polymerase III transcription complexes in human cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 635–640. 10.1038/nsmb.1794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahmad AD, Reuveni E, Goldschmidt E, Tenne T, Liberman M, Horovitz-Fried M, Khosravi R, Kobo H, Reinstein E, Madi A, et al. 2022. Frequent aneuploidy in primary human T cells after CRISPR–Cas9 cleavage. Nat Biotechnol 10.1038/s41587-022-01377-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J. 2000. T-Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J Mol Biol 302: 205–217. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olbrich T, Mayor-Ruiz C, Vega-Sendino M, Gomez C, Ortega S, Ruiz S, Fernandez-Capetillo O. 2017. A p53-dependent response limits the viability of mammalian haploid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114: 9367–9372. 10.1073/pnas.1705133114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oler AJ, Alla RK, Roberts DN, Wong A, Hollenhorst PC, Chandler KJ, Cassiday PA, Nelson CA, Hagedorn CH, Graves BJ, et al. 2010. Human RNA polymerase III transcriptomes and relationships to Pol II promoter chromatin and enhancer-binding factors. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 620–628. 10.1038/nsmb.1801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottenburghs J, Geng K, Suh A, Kutter C. 2021. Genome size reduction and transposon activity impact tRNA gene diversity while ensuring translational stability in birds. Genome Biol Evol 13: evab016. 10.1093/gbe/evab016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DDG, Caulder A, Frontera V, Harman JR, Allan AJ, Bucakci A, Greder L, Codner GF, Hublitz P, McHugh PJ, et al. 2019. Microhomologies are prevalent at Cas9-induced larger deletions. Nucleic Acids Res 47: 7402–7417. 10.1093/nar/gkz459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez F, Ryan DP, Grüning B, Bhardwaj V, Kilpert F, Richter AS, Heyne S, Dündar F, Manke T. 2016. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 44: W160–W165. 10.1093/nar/gkw257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F. 2013. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc 8: 2281–2308. 10.1038/nprot.2013.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner E, Durin M-A, Thomas R, Moralli D, O'Cathail SM, Tomlinson I, Green CM, Lewis A. 2019. CRISPR-Cas9 causes chromosomal instability and rearrangements in cancer cell lines, detectable by cytogenetic methods. Cris J 2: 406–416. 10.1089/crispr.2019.0006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. 2011. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol 29: 24–26. 10.1038/nbt.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roidos P, Sungalee S, Benfatto S, Serçin Ö, Stütz AM, Abdollahi A, Mauer J, Zenke FT, Korbel JO, Mardin BR. 2020. A scalable CRISPR/Cas9-based fluorescent reporter assay to study DNA double-strand break repair choice. Nat Commun 11: 4077. 10.1038/s41467-020-17962-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KLM, Schmitt BM, Villar D, White RJ, Marioni JC, Kutter C, Odom DT. 2016. Codon-driven translational efficiency is stable across diverse mammalian cell states. PLoS Genet 12: e1006024. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander JD, Joung JK. 2014. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat Biotechnol 32: 347–355. 10.1038/nbt.2842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt BM, Rudolph KLM, Karagianni P, Fonseca NA, White RJ, Talianidis I, Odom DT, Marioni JC, Kutter C. 2014. High-resolution mapping of transcriptional dynamics across tissue development reveals a stable mRNA–tRNA interface. Genome Res 24: 1797–1807. 10.1101/gr.176784.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Le S, Li Y, Hu F. 2016. SeqKit: a cross-platform and ultrafast toolkit for FASTA/Q file manipulation. PLoS One 11: e0163962. 10.1371/journal.pone.0163962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin HY, Wang C, Lee HK, Yoo KH, Zeng X, Kuhns T, Yang CM, Mohr T, Liu C, Hennighausen L. 2017. CRISPR/Cas9 targeting events cause complex deletions and insertions at 17 sites in the mouse genome. Nat Commun 8: 15464. 10.1038/ncomms15464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou J, Li J, Liu Y, Wu Q. 2018. Precise and predictable CRISPR chromosomal rearrangements reveal principles of Cas9-mediated nucleotide insertion. Mol Cell 71: 498–509.e4. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]