Abstract

Episodic memory relies on the coordination of widespread brain regions that reconstruct spatiotemporal details of an episode. These topologically dispersed brain regions can rapidly communicate through structural pathways. Research in animal and human lesion studies implicate the fornix—the major output pathway of the hippocampus—in supporting various aspects of episodic memory. Because episodic memory undergoes marked changes in early childhood, we tested the link between the fornix and episodic memory in an age window of robust memory development (ages 4–8 years). Children were tested on the stories subtest from the Children’s Memory Scale, a temporal order memory task, and a source memory task. Fornix streamlines were reconstructed using probabilistic tractography to estimate fornix microstructure. In addition, we measured fornix macrostructure and computed free water. To assess selectivity of our findings, we also reconstructed the uncinate fasciculus. Findings show that children’s memory increases from ages 4 to 8 and that fornix micro- and macrostructure increases between ages 4 and 8. Children’s memory performance across nearly every memory task correlated with individual differences in fornix, but not uncinate fasciculus, white matter. These findings suggest that the fornix plays an important role in supporting the development of episodic memory, and potentially semantic memory, in early childhood.

Keywords: fornix, memory development, tractography, uncinate

Introduction

Episodic memory development

Episodic memory is characterized by the capacity to retrieve previous experiences in the spatiotemporal contexts that make up specific events of our past (Tulving 1972). As such, the source (i.e. from whence or whom information was learned) and temporal components of an event that specify its spatiotemporal context are hallmarks of an episodic memory, enabling the reconstruction for not only “what” happened, but “where” and “when” an event occurred. Although some episodic-like memory capacities emerge early in development (Bauer et al. 2011), many aspects of episodic memory undergo protracted development, most notably from early to middle childhood (reviewed in Newcombe et al. 2022, in press).

Contributing to the overall gains in episodic memory capacity is improvements in both source and temporal memory. Both cross-sectional (Lindsay et al. 1991; Drummey and Newcombe 2002; Riggins et al. 2018) and longitudinal (Riggins 2014) studies have found that children’s abilities to correctly retrieve the source of an event show robust improvements between the preschool and school-age years. In one paradigm, children learned novel facts (e.g. giraffes cannot make any sounds) from one of two sources: an experimenter or a puppet. After a 1-week delay, children’s memory for facts showed steady age-related improvements: 8-year-olds performed best, followed by 6-year-olds, followed by 4-year-olds. Source memory (i.e. “From whom did you learn each fact?”) showed a robust age effect between age 4 and 6, but not between age 6 and 8 (Drummey and Newcombe 2002). Similarly to these cross-sectional findings, longitudinal patterns showed that memory for facts linearly increased from age 4 to 10; whereas source memory showed accelerated growth from age 5 to 7, with gains tapering off thereafter (Riggins 2014). More recently, one cross-sectional study found that source memory accuracy almost quadrupled from age 4 to 8, with individual variability significantly tracking gray matter volumes in multiple hippocampal subfields (Riggins et al. 2018; Canada, Botdorf, et al. 2020; Geng et al. 2021).

Over the same age window, children’s abilities to remember the temporal sequence of events also show striking improvements (Picard et al. 2012; Bauer 2013; Canada, Pathman, et al. 2020). Studies on autobiographical memories in 4-, 6-, and 8-year-old children reveal that older children, but not 4-year-olds, were accurate in remembering the order of two personal events (Pathman et al. 2013). These results parallel findings from lab-based temporal memory assessments, such as one where children were asked to reconstruct a learned sequence of activities that occurred in various times of a day. Interestingly, children’s performance on the temporal order did not exceed chance level until after age 6, followed by improvements thereafter (Picard et al. 2012). Studies that use the standardized NIH Toolbox Picture Sequence Memory Test showed a sharp linear association with age between age 3 and 10 in a cross-sectional design (Bauer 2013), and robust within-person, longitudinal changes in memory from age 4 to 8 (Canada, Pathman, et al. 2020).

Despite the rich behavioral data on this action-packed developmental period for source, and temporal memory, little is known about how brain maturation relates to children’s memory performances. Evidence from cognitive neuroscience in adults has suggested that episodic memory relies on brain regions that coordinate episodic memory competencies (Rugg and Vilberg 2013). Such coordination across remote brain regions critically relies on white matter connectivity that can sufficiently transfer information from region to region. Although much effort has been expended to characterize the developmental trajectories of white matter (Lebel et al. 2008; Lebel and Beaulieu 2011), the link between white matter indices and early episodic memory ability has been examined in few studies. One study in 4- and 6-year-old children showed that interindividual variations in memory binding (i.e. memory for what-where associations) were significantly related to the white matter microstructure connecting the hippocampus to the inferior parietal lobule (Ngo et al. 2018). This research provides preliminary support for the hypothesis that white matter development subserves episodic memory performance in early childhood. Contrary to expectations, this study did not find an association between episodic memory development and forniceal microstructure, which may have been due to a number of methodological limitations in the age-range examined and imaging procedures, discussed next.

Fornix

The fornix is the primary axonal tract of the hippocampus, connecting it to modulatory subcortical structures (Amaral and Lavenex 2007). A rich literature in nonhuman animals shows that damage to the fornix impairs trace and contextual fear conditioning, reversal learning, and performance on a variety of spatial memory tasks (Hirsh and Segal 1972; O'Keefe et al. 1975; Walker and Olton 1979; Murray et al. 1989; Wiig et al. 1996; Ennaceur and Aggleton 1997; Whishaw and Tomie 1997; de Bruin et al. 2001; Kwok and Buckley 2006; Wilson et al. 2007). In adult humans, the fornix has primarily been studied using diffusion MRI (dMRI) techniques. These investigations have corroborated much of the primate and rodent literature investigating the role of the fornix in long-term forms of memory (reviewed in Benear et al. 2020). Human research has consistently reported correlations between fornix microstructure and performance on a range of standardized memory tests such as paired associates, “Doors and People,” and verbal list learning in neurologically normal adults, individuals with mild cognitive impairment, and individuals with Alzheimer’s Dementia (Rudebeck et al. 2009; Metzler-Baddeley et al. 2011; Metzler-Baddeley et al. 2012; Zhuang et al. 2013; Kantarci et al. 2014; Bennett et al. 2015; Ray et al. 2015; Antonenko et al. 2016; Bennett and Stark 2016; Hodgetts et al. 2017; Benear et al. 2020). Furthermore, a relation between in vivo reconstructions of the fornix and remote autobiographical memory has been reported, whereas there was no relation between this tract and semantic memory performance (see Poreh et al. 2006; Williams et al. 2020; reviewed in Benear et al. 2020). This robust line of evidence supporting the fornix’s role in a large spectrum of memory tasks suggests that the fornix may play a general role in long-term forms of memory.

There is evidence that forniceal microstructure continues to be refined throughout childhood. Most, but not all, studies have reported increases in fractional anisotropy (FA) in childhood (see Table 1 for summary) (Dimond et al. 2020; Reynolds, Long, et al. 2019; Lebel et al. 2008; Huang 2010; Reynolds, Grohs et al. 2019). More puzzling is the fact that previous studies of children’s memory performance did not detect any relation between the fornix and memory performance (Wendelken et al. 2015; Ngo et al. 2017). The current lack of evidence supporting this relation is striking, given the consistent and robust relation between variation in fornix microstructure and memory abilities in neurologically healthy adult samples, as well as individuals with memory disorders such as Alzheimer’s Dementia (reviewed in Benear et al. 2020). It is possible that the null findings reported in the two previous studies result from: (i) the restricted age range in early childhood (i.e. ages 4 and 6; Ngo et al. 2017) and (ii) task characteristics that tap the ancillary, but not central construct of episodic memory (i.e. mnemonic control; Wendelken et al. 2015), and thus are not reliant on the fornix. An additional potential explanation for previously reported null effects is that prior studies in children suffered from the methodological problem described below.

Table 1.

A summary of studies that have measured the fornix in developmental samples using diffusion imaging methods. With the exception of Dimond et al. (2020), all studies used DTI. Note that most studies did not measure memory performance but instead, simply focused on age-related structural changes in the fornix.

| Authors and Year | N, age range | Diffusion Directions | Effects of developmental age on: | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fornix FA | Fornix Macrostructure | Memory performance | |||

| Dimond et al. (2020) | 73; 4–8 | 45 | yes | yes | Not measured |

| Hoffman et al. (present) | 66; 4–8 | 64 | yes | yes | yes |

| Lebel et al. (2008) | 202; 6–29 | 6 | no | Not measured | Not measured |

| Ngo et al. (2017) | 47; 4 and 6 | 64 | no | Not measured | yes |

| Reynolds, Grohs, et al. (2019) | 120; 2–8 | 30 | yes | Not measured | Not measured |

| Simmonds et al. (2014) | 128; 8–28 | 6 | yes | Not measured | Not measured |

| Wendelken et al. (2015) | 116; 7–11 | 64 | no | Not measured | yes |

| Yu et al. (2020) | 118; 0–8 | 30 | yes | Not measured | Not measured |

Much of the fornix is located in the third ventricle and thus is surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The diffusion properties of CSF differ from that of white matter—namely, due to water molecules in the CSF, which are free to diffuse and do not experience restriction or hindrance. However, due to the size of the fornix, and the coarse image resolution afforded by most imaging sequences, partial volume with CSF may inadvertently occur in the voxels identified as part of the fornix (Sullivan et al. 2010; Gunbey et al. 2014; Oishi and Lyketsos 2014; Hodgetts et al. 2015; Hodgetts et al. 2017). If free water (FW) is not accounted for in the estimation of the fornix diffusion metrics, findings can be unreliable, reflecting the amount of partial volume with CSF, rather than the true microstructural features of the fornix. Other sample populations, such as neurologically normal older adults (Apostolova et al. 2012), individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease (Apostolova et al. 2012), multiple sclerosis (Dalton et al. 2006), anorexia nervosa (Kaufmann et al. 2017), and schizophrenia (Sayo et al. 2012) have ventricular enlargement relative to matched controls, which may lead to heightened extracellular FW, therefore rendering these populations more susceptible to partial volume with FW when examining their white matter. It is likely that young children, whose brains are still developing, have relatively higher levels of FW. However, we do not know which aspect of FA, namely the microstructure of the fornix versus partial volume with FW, is developmentally relevant in the domain of episodic memory ability.

Current study

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that dMRI metrics derived from the fornix will correlate with performance on multiple facets of episodic memory during the transition from early to middle childhood. Prior studies in adults show that variability in fornix structure relates to performance on a wide range of episodic memory processes including associative memory, list learning, and pattern separation (Rudebeck et al. 2009; Zhuang et al. 2013; Bennett et al. 2015; Foster et al. 2019). Here, we tested the prediction that fornix white matter connectivity would co-vary with episodic memory ability in 4- to 8-year-old children using a multi-assessment design. Importantly, we measured the multivariate profile of episodic memory, i.e. the spatiotemporal specificity of memories, including verbal recall, temporal memory, and source memory. Given that little is known about the fornix-memory association in children, we further explored the role of fornix in semantic memory, measured by thematic verbal recall and fact memory. We hypothesized that the fornix plays a specific role in the development of episodic memory in childhood and, as such, should show no relation with semantic memory. Alternatively, the fornix could underpin memory capacities in children more broadly, encompassing both episodic and semantic memory capacities in children.

To test for the unique associations between the fornix and memory performance, we also investigated dMRI measures of another limbic fiber-path: the uncinate fasciculus. Connecting the anterior temporal lobes and amygdala to ventral portions of the frontal lobe, the uncinate fasciculus is involved in a more limited repertoire of learning and memory processes as well as in social cognition (Olson et al. 2013; Von Der Heide et al. 2013). Importantly, we employed a dMRI model for white matter that enabled the elimination of FW that surrounds a given fiber, thereby unveiling the behaviorally relevant microstructural properties of limbic white matter connectivity (Pasternak et al. 2009). We considered these white matter indices together in order to make conjectures about the underlying mechanisms that may inform a biological understanding of memory abilities in a cross-sectional developmental sample. Taken together with streamlines (SL), our microstructural results with FA will allow us to make inferences about the changes in fiber density, width, and myelination (Jones et al. 2013; Gonzalez-Remiers et al. 2019) that may be developmentally relevant biomarkers of memory competency in children. We employed FA as our primary microstructural index of interest, in order to make contact with our prior findings in children (Ngo et al. 2017) and the adult literature on dMRI and memory, which is dominated by studies using FA.

Methods and materials

Participants

The current study was part of a larger research project examining the development of the brain in relation to episodic memory during early- to mid-childhood (see Riggins et al. 2018). The current report examines the question of whether there is a relation between dMRI measures of the fornix, development, and various types of episodic memory. The study included 66 4- to 8-year-old children (M (SD) = 6.77 (1.41) years, 29 males). The final sample of participants was predominantly Caucasian (64.06%), not Latinx (85.71%), and from middle- to high-income households (median ≥ $105,000). For a summary of demographic information, see Supplementary Table 1. Prior to data collection, all methods were approved by the Institutional Review Board at The University of Maryland. Children were screened to ensure that they were not born premature, had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and had no diagnosis for any neurological conditions, developmental delays, or disabilities. Parents provided informed consent, and written assent was obtained for children older than 7 years of age.

Procedure

Children visited the laboratory twice, ~7 days apart. During the first session, children completed initial memory testing procedures and were informed of the requirements for undergoing MRI scanning. Upon children’s second visit, follow-up behavioral testing and the MRI scan were undergone.

Behavioral measures of memory

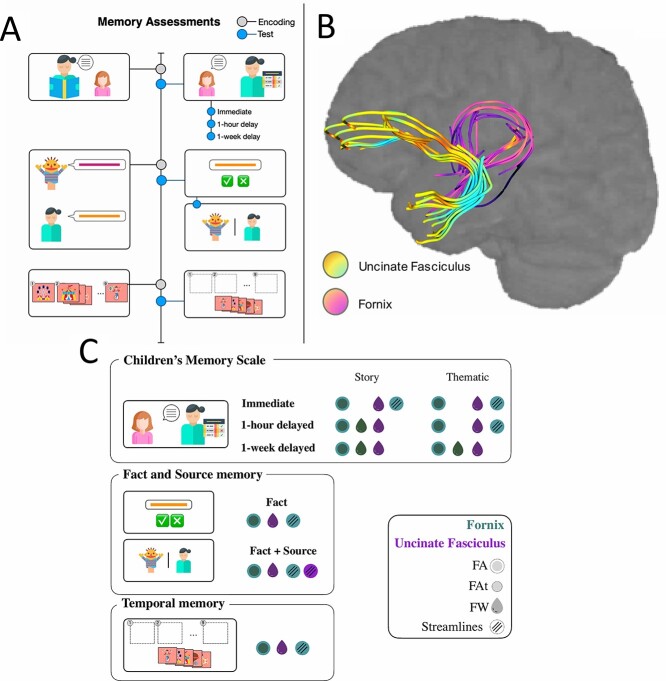

Participants completed several different memory tests, described below (see Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a) Schematic depictions of the memory assessments (left) and diffusion-weighted-imaging pipeline (right). The memory assessments comprised three tasks depicted in descending order: The CMS, the fact-source task, and the picture sequence task; b) Tactography for the uncinate (abbreviated UF) and fornix in a representative subject; and c) a graphic summary of the findings with each white matter index (legends) in each of the memory measures.

1) Episodic memory

Children’s Memory Scale: Story Units. To assess episodic (i.e. verbatim) memory, the Stories subtest of the Children’s Memory Scale (CMS; Cohen 1997) was administered, and memory was evaluated at immediate, 1-h, and 1-week delays. In this task, children were instructed to listen closely to two 7-sentence stories that were read aloud by the experimenter in anticipation of having to recount the stories at future junctures. At each delay, children were prompted to recall the story details by being reminded of the general topic of the story (e.g. “Remember the story I read to you about the boys? I want you to tell me the story again.”). Here, episodic memory is operationalized as percentage recall correct for a set of 57 predetermined story units. The proportion correct was averaged across the two stories, which was performed in order to extract an episodic memory score at each timepoint.

Temporal Memory: This temporal order memory task was adapted from Bauer (2013) in order to evaluate recall memory for sequential information. In this task, children were shown 2 out of 3 lists of 9-item picture sequences, which were randomly assigned and counterbalanced across subjects (for a detailed description see Canada, Pathman, et al. (2020)). These lists depicted scenes from either a pet shop, park, or fair on a series of index cards, which were each placed on the table in front of the child in an upside-down V-shape from the child’s left to right. Each sequence was presented with an introductory sentence (e.g. “I’m going to show you how I work in the yard.”), while each node in the sequence was presented with a verbal label (e.g. “mow the lawn”) in the absence of transition words (e.g. “next” or “then”). Once displayed in full, the experimenter restated the introductory sentence for the sequence in question, shuffled the deck, and instructed the child to recreate the sequence with the index cards. On half the trials, the experimenter assigned a distractor task (tic-tac-toe or learning to draw a house) after which his or her delayed recall of the sequence order was reassessed; this manipulation did not significantly impact performance Canada, Pathman, et al. (2020). The child’s response was recorded for each trial. Note that the administration of this task was preceded by a four-item practice trial of a yard scene. Performance was scored based on the number of adjacent pairs that were placed in the exact correct order (i.e. cards 3 and 4 being placed in slots 3 and 4). There was a total of 16 possible correct adjacent pairs across the two sequences, and proportion correct was calculated.

Source Memory Task: Source and Fact Memory. A source memory task (see Riggins et al. 2018 for additional details) that is sensitive to age-related differences in memory ability during early childhood (Drummey and Newcombe 2002; Riggins 2014) was administered. Briefly, children visited the lab on two separate occasions. During the first visit, children watched digital videos in which they were taught 12 novel facts, 6 each from one of two different sources: a person or a puppet. Children were instructed to remember the facts but were not told that they needed to pay attention to the source. During the second visit, ~1 week later, children were tested on their memory for both the novel facts and their source. Children were asked to answer 22 fact questions and to tell the experimenter where or from whom they had learned the answers to those questions; 6 of the 22 facts had been presented by the person, and 6 were from the puppet, while 5 were facts commonly known by children, and 5 were facts that children typically would not know.

After the experimenter asked each question, children were given the opportunity to answer freely. If children indicated that they did not know the answer, they were given four predetermined multiple-choice options. Once children gave an answer to the trivia question, they were asked where or from whom they had learned the information. As with fact questions, children were given the opportunity to answer freely, but if they indicated that they did not know where the fact was learned, they were given multiple-choice options: parent, teacher, person in the video, puppet in the video, or just knew/guessed.

The episodic-dependent measure that this task provided included a measure of source memory, which refers to the proportion of questions for which the child accurately recalled both the fact and the source, which is an important aspect of episodic memory (Miller et al. 2013; Ritchey and Cooper 2020). Three types of errors were measured: children indicating that they guessed or always knew the fact (termed guessed/knew errors), children indicating a person outside the experiment taught them (termed extra-experimental errors, e.g. teacher, parent, television, and book), or children indicating the wrong experimental source taught them the fact (termed intra-experimental errors).

2) Gist memory

CMS: Thematic Units. The Stories subtest of the CMS (Cohen 1997) described above was also used to assess gist (i.e. thematic) memory at immediate, 1-h, and 1-week delays. Gist memory was measured by recall of the thematic units of each of the two stories (13 altogether). Similar to the extraction of the episodic measures, the proportion correct for each story was averaged across the two stories to yield overall scores for gist memories at each of the aforementioned timepoints.

Source Memory Task: Fact Memory. The gist memory measure yielded by the source memory task described above included memory for individual facts learned during the encoding period. This was measured independently of memory for the source from whence the fact was learned, offering a more semantic metric of memory functioning.

Intelligence

General intelligence was measured using age-appropriate subtests from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fourth Edition or the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence. Scaled scores from the block design subtest, which reflects visual–spatial intelligence, were used as covariates in analyses to control for general differences in intelligence. Each subtest produces a scaled score that ranges from 1 to 19, with scores between 7 and 12 usually considered average. The range in our final sample was 6–19.

Brain image acquisition

Neuroimaging data were collected during children’s second visit to the lab. Children first participated in a mock scan that allowed them to get comfortable with the scanning environment. Children received motion training in the mock scan, where they practiced laying still and were given motion feedback by the experimenter. Following the mock scan, children completed the actual scan. During the scan, padding was placed around children’s heads to reduce motion. Participants were scanned in a Siemens 3.0 T scanner (MAGNETOM Trio Tim System, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) with a 32-channel coil. During scans, children watched a movie of their choosing to promote compliance.

Image acquisition included a high-resolution T1 magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence (176 contiguous sagittal slices, 0.9-mm isotropic voxel size; 1900 ms TR; 2.32 ms TE; 900-ms inversion time; 9° flip angle; 256 × 256-pixel matrix). T1 images were checked immediately following the scan to ensure high data quality. If the quality of the image was deemed to be too low, due to visual banding or visible blurring, the scan was repeated during the same session.

Diffusion images were acquired with a twice-refocused spin-echo single-shot Echo Planar Imaging sequence with a parallel imaging mode at an acceleration factor of 2. The diffusion scheme comprised of 64 noncollinear diffusion-weighted acquisitions with b = 1000 s/mm2 and a single T2-weighted b = 0 s/mm2 acquisition (TR/TE = 5500/85 ms, 96 × 96 matrix, 2.2 × 2.2 mm2 in-plane resolution, flip angle = 90°, and a bandwidth of 1158 Hz/Px, for all 44 slices at 3.5-mm thickness).

Brain image processing

dMRI preprocessing

Diffusion-weighted images were processed using tools in the FMRIB Software Library (FSL v6.0.2; Image Analysis Group, FMRIB, Oxford, UK; https://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/; Smith et al. 2004). Using the FMRIB Diffusion Toolbox, subject motion and eddy current-induced distortions were corrected (Andersson et al. 2003; Andersson and Sotiropoulos 2016). A binary brain mask was created by removing the nonbrain tissue with FSL’s Brain Extraction Tool (BET) from each subject’s nondiffusion (b0)-weighted image volume. Next, a diffusion tensor was fitted to each voxel, from which eigenvector and eigenvalues along with MD and FA (Pierpaoli et al. 1996) were computed in native anatomical space using the dtifit program in FSL.

All subjects’ data were meticulously analyzed by trained analysts after each step in the preprocessing pipeline. Data were screened for intensity artifacts, motion, and other quality-related issues. After a primary rater assessed the data for appropriateness of analysis, a second rater was assigned a random one-third of all subjects’ data, and interrater reliability was assessed in the final decision-making process. Raters agreed on all counts in terms of the acceptability of the final sample in regard to motion displacement and intensity artifacts. If more than five volumes were found to be faulty, subjects were not counted in the final analysis.

DTI and FW maps

The uncorrected FA and the FW corrected FA (termed FAt; −t stands for “tissue”; Chad et al. 2018) were selected as our microstructural measures of interested in the absence of the other DTI scalars for two reasons: (i) to minimize the number of multiple comparisons and the consequent proliferation of analyses performed in the current study and (ii) due to the fact, this metric is the most pervasive and well understood in the existent DTI literature. FA values exist on a sliding scale between 1 and 0, with a value of 1 indicating pure anisotropy (i.e. constraint of the diffusion of water molecules along an axis), and values of 0 reflecting pure isotropy. Procedures for calculating FW corrected FA (FAt) and free-water volume fraction (FW) are described in the section below. All microstructural metrics were calculated for each tract by overlaying the diffusion space fornix and uncinate masks onto the diffusion scalar maps of interest (i.e. FA, FAt, and FW). From there, the average was taken across all voxels in our tractographies and these values were used in subsequent analyses.

Moreover, it is important to stress that the fornix passes through the third ventricle and, therefore, is surrounded by CSF, making it prone to susceptibility artifacts and partial volume effects (Sullivan et al. 2010; Gunbey et al. 2014; Oishi and Lyketsos 2014; Hodgetts et al. 2017; Hodgetts et al. 2019). To counter this problem, we used FW elimination methods (Pasternak et al. 2009). FW elimination was performed in MATLAB using an algorithm that performed data regularization to obtain the FW model from single-shelled data. The model includes two compartments, one accounting for isotropic extracellular FW and a second compartment accounting for the remaining water molecules, which originate from brain tissue. FW is the fractional volume of the FW compartment. The tissue compartment is modeled as a diffusion tensor, from which FAt is calculated using FSL. Such data regularization was required since higher b-values are typically required to image different tissue compartments, such as CSF. Due to the age of our data (i.e. collected prior to 2019), we did not have a more sophisticated data-acquisition scheme with higher b-values at our disposal, necessitating the implementation of an in-house FW correction method. Unfortunately, more state-of-the-art sequences require longer acquisition times (Tamnes et al. 2018), which may render them ill-suited for use in developmental samples.

Probabilistic tractography

To perform the fiber reconstruction, probabilistic tractography was conducted using the FDT Toolbox with the BEDPOSTX ball-and-sticks model, allowing up to two fiber directions in each voxel, to better account for crossing fibers and therefore to yield more reliable results compared with single-fiber models (Behrens et al. 2007). Each connectivity profile was constructed by seeding 5000 streamline samples at the level of each voxel, using FSL default parameters for curvature thresholding, step length, and number of maximum steps (Behrens et al. 2007). The fornix was examined as a single tract due to its location along the midline of the brain. Tractography for the uncinate was performed separately for the left and right, excluding the contralateral hemisphere in each case. Subsequently, all diffusion measures for the uncinate were averaged across the left and right in order to circumvent the issue of multicollinearity in our regression models. Note that the goal of our study was to measure the fornix, which is never bifurcated in the literature. For an example of the resultant tractographies in a representative subject, see Fig. 1b.

Regions of interest for tractrography

In order to generate 10-mm spheres that propagate along the contours of both the uncinate and fornix, we overlaid standard space tracts from the Johns Hopkins University White Matter and Juelich Histological Atlases, respectively, onto an MNI brain with a resolution of 2 × 2 × 2 mm3. Previous research has successfully used these atlases to register the brains of children in the current age group under study (Ngo et al. 2017). For the uncinate, coordinates were selected in the temporal pole, orbitofrontal cortex, and along the arch of the tract, a procedure that was repeated bilaterally. For the fornix, seeds and targets were identified in the bilateral anterior columns and fimbria, while the waypoint was designated in the body of the fornix. MNI coordinates were subsequently aggregated in FSL for sphere creation, warped into subjects’ native space, and binarized. Custom exclusion masks for each tract were also drawn in FSL and were similarly binarized and warped into subject-specific diffusion space. The latter step was performed in order to ensure that our target tracts were extracted in a circumscribed manner without picking up on the adjacent limbic circuitry. All resultant tractographies were visually inspected for inclusion in subsequent analyses. For a review of similar methodology, see Ngo et al. (2017).

To delineate these transformation parameters, a series of linear registrations were performed. First, subjects’ T1-weighted images were skull-stripped using FSL’s BET, which executed a bias field and neck cleanup. Next, subjects’ b0 images were registered to their respective T1-weighted anatomical images with 12 degrees of freedom and a correlation ratio cost function, yielding a diffusion to structural space conversion matrix. The same registration method was used to warp subjects’ T1-weighted images to the 2 × 2 × 2 mm3 MNI space brain template, creating a structural to standard space conversion file. Concatenating the inverse of the two aforementioned matrices resulted in the standard space to diffusion space conversion matrix that was used to convert the spheres to subject space. All registrations between b0 and T1-weighted images were visually inspected, and no manual interventions were needed. Note that linear registration was used for all conversions, as the spheres we used for tractography were large (10 mm) and did not require hyper-precise registration. Moreover, all sphere and exclusion mask conversions were visually inspected to ensure the registration occurred satisfactorily, negating the necessity for a more rigorous conversion scheme.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were run in R (https://www.r-project.org) using RStudio (www.rstudio.com) integrated development environment. Multiple beta regressions and bivariate Pearson correlations were used for all analyses. First, to examine the relation between age, brain, and behavior, bivariate Pearson correlations were performed between age and the nine memory measures. Note that age was calculated precisely by taking the difference in years and days between the date of the child’s birth and the date of initial participation. That is, chronological age was in years out to two decimal places based on the aforementioned dates. Subsequently, associations between age and tract-specific (i.e. fornix and uncinate) metrics of white matter macro- and microstructure were performed. Four white matter indices were measured: (i) SL (controlled for by seed volume); (ii) FA; (iii) FAt; and (iv) FW. We chose to include a range of measures, both to explore the space of white matter maturation, as well as to gain traction on understanding the robustness of brain–behavior relations.

Beta regressions were performed, as this is the most appropriate model to run on data whose dependent measure is a proportion (i.e. percentage correct on memory tasks). This is due to the fact that data that are constrained between 0 and 1 are better approximated by the beta distribution than the Gaussian distribution (Ferrari and Cribari-Neto 2004). Furthermore, in order to run these models using the betareg package in R, no values in the outcome variable could be equal to 0 or 1, and therefore, a transformation of the dependent measures was applied in order to extend the tails of the distribution (Smithson and Verkuilen 2006). Once transformed, we conducted 4 sets of 9 beta regressions. The formula for the models all followed the same outline: [Memory Measure] ~ [IQ] + [Comparison Tract (e.g. uncinate)] + [Tract of Interest (e.g. fornix)]. The only index that varied within the sets was the memory measure, and the only index that varied between the sets was the type of white matter metric we looked at (i.e. FA, FW, SL, etc.). IQ and the comparison tract index (i.e. always an average of the left and right uncinate) are comparison measures, while the variable of interest is the fornix. Linear modeling was selected for two reasons. First, visual inspection of the data revealed that the data adhered well to linear trends. Second, a review by Lebel et al. (2019) found that linear modeling for developmental samples with a small age range tend to best explain the data.

Last, chi-square tests on each of these models were performed in order to assess whether or not the addition of the fornix yielded a significant change in the log-likelihood function yielded by each regression. These analyses were conducted using the lmtest package in R.

Results

Effects of age

Data relating age to memory performance can be found in Table 2. Results show that memory performance strongly correlated with age on every metric tested. The source and temporal order memory behavioral data have been previously reported (source memory: Riggins et al. 2018; temporal memory: Canada, Pathman et al. (2020)). The samples studied in this paper are a subset of these samples who yielded useable diffusion imaging scans. The findings regarding story recall are novel.

Table 2.

Means, SE, and correlations between memory performance and age. From ages 4–8 years, memory performance improved across all measures.

| Memory measures | Mean (SE) | Correlation with age (r) |

|---|---|---|

| Scaled Block Design Score | 12.15 (0.355) | .146 |

| CMS Story Units: • Immediate | 0.536 (0.032) | .704*** |

| • 1 hour delay | 0.465 (0.034) | .696*** |

| • 1 week delay | 0.472 (0.032) | .700*** |

| Temporal Memory | 0.518 (0.029) | .707*** |

| Source Memory | 0.290 (0.023) | .534*** |

| CMS Thematic Units: • Immediate | 0.142 (0.009) | .707*** |

| • 1-h delay | 0.124 (0.009) | .710*** |

| • 1-week delay | 0.130 (0.009) | .734*** |

| Fact memory | 0.628 (0.028) | .564*** |

SE, standard error.

* P < 0.05.

** P < 0.01.

*** P < 0.001.

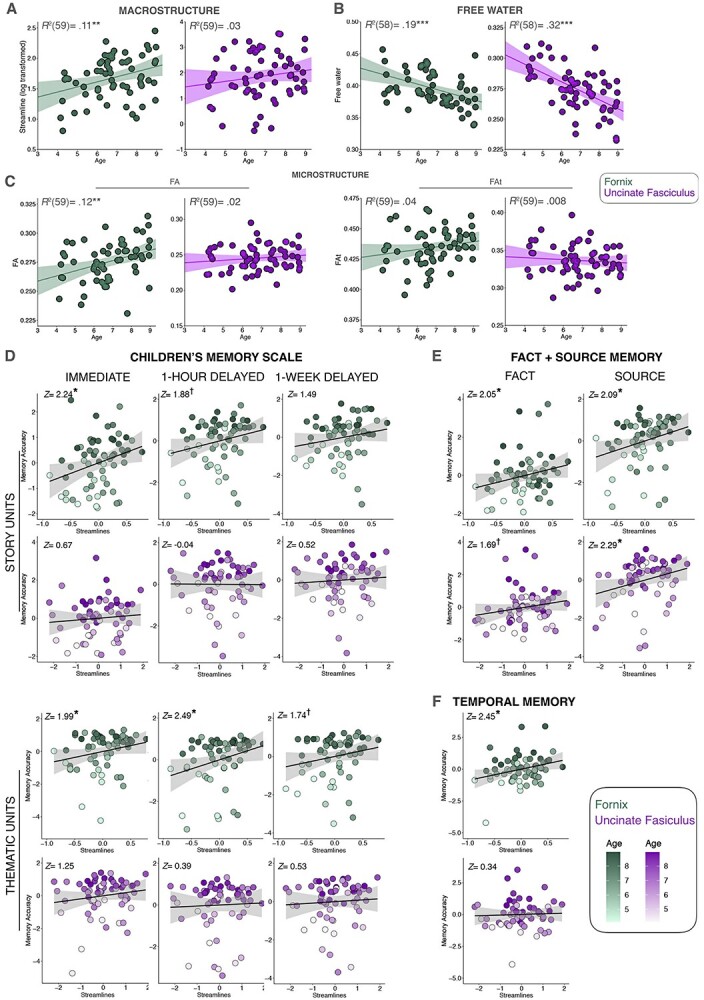

We additionally asked whether fornix macrostructure and microstructure increased with age, as has been reported by some prior investigators (see Table 3). Pearson correlations showed that fornix macrostructure increased with chronological age [e.g. SL controlled for by seed volume in voxels, r(59) = 0.33, P = 0.009; overall tract volume in voxels, r(59) = 0.43, P < 0.001] (see Supplementary Table 2). Fornix microstructure, indexed by FA, also increased with chronological age, r(59) = 0.36, P = 0.005, similar to previously reported findings. However, this effect was no longer statistically significant in FAt, i.e. after controlling for extracellular FW, r(59) = 0.20, P = 0.123. In contrast, SL, FA, and FAt in the uncinate did not vary with age. For both the fornix and uncinate, the average amount of FW decreased with age (see Fig. 2a–c). In both the fornix and uncinate, it is also important to note that tract volume in voxels increased with age (see Table 3). While not depicted in the table, it is also important to note that overall intracranial head volume (ICV) showed no relation with age.

Table 3.

Correlations between white matter metrics and age. The middle and right columns list the mean, SE, and correlation (r values) with age. In regards to the fornix, the number of SL and FA increased between the ages of 4–8, while the amount of FW decreased with age. In contrast, in the uncinate, only FW decreased with age, while overall tract volume in voxels for both tracts correlated with age.

| Fornix | Uncinate | |

|---|---|---|

| SL | 1.682 (0.045); 0.332*** | 1.861 (0.120); ns |

| FAt | 0.435 (0.002); ns | 0.336 (0.003); ns |

| FA | 0.275 (0.002); 0.357*** | 0.245 (0.002); ns |

| FW | 0.395 (0.027); −0.441*** | 0.274 (0.018); −0.609*** |

| Tract volume | 3339.94 (61.746); 0.418*** | 1083.015 (27.090); 0.277* |

* P < 0.05.

** P < 0.01.

*** P < 0.001.

Fig. 2.

Scatterplots depicting the relation between age and white matter indices including a) SL, b) FA, and c) surrounding FW. Additional scatterplots between memory performances (y-axes) and white matter SL (log-transformed, x-axes) from each task: d) the CMS, e) fact + source task, and f) temporal memory task. Note that in the scatterplots for (d, e, and f) the covariates of noninterest have been regressed out to illustrate the unique variance accounted for by the tract being depicted. Significance notation: ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Because age strongly correlated with memory performance as well as with many of our white matter metrics, age was not entered into subsequent analyses. Age and white matter cannot be separated in regard to their effects on memory. For instance, developmental age alters neural white matter and either by a separate mechanism or a combined and related mechanism, developmental age alters memory abilities. Given the current data, we cannot distinguish these scenarios thus we simply focus on the relation between white matter and memory in children.

Relations between white matter and memory performance

The results summary is presented in Supplementary Table 2 and schematically depicted in Fig. 1c. Detailed findings can be found in Fig. 2d, Table 4, and Supplementary Fig. 1 and Tables 3–5. To simplify these complex findings, we describe them in narrative form below.

Table 4.

Macrostructural regression models (SL). Fornix and uncinate SL were log transformed to resolve skewness.

| Episodic memory models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMS Immediate Recall for Story Units: Percentage Correct | ||||

| Model | Parameter | Estimate | 95% CI (Std. Err) | z, P |

| 1 | IQ: β 1 | 0.101 | 0.03, 0.19 (0.042) | 2.40, 0.016* |

| Uncinate SL: β 2 | 0.082 | −0.16, 0.33 (0.123) | 0.67, 0.506 | |

| 2 | Fornix SL: β 3 | 0.732 | 0.10, 1.38 (0.326) | 2.24, 0.024* |

| R 2 p | 0.18 | |||

| CMS 1 -h Delay Recall for Story Units: Percentage Correct | ||||

| Model | Parameter | Estimate | 95% CI | z, P |

| 1 | IQ: β 1 | 0.091 | −0.004, 0.21 (0.047) | 1.95, 0.051 |

| Uncinate SL: β 2 | −0.006 | −0.22, 0.23 (0.137) | −0.04, 0.965 | |

| 2 | Fornix SL: β 3 | 0.682 | −0.09, 1.41 (0.362) | 1.88, 0.060 |

| R 2 p | 0.11 | |||

| CMS 1 -Week Delay Recall for Story Units: Percentage Correct | ||||

| Model | Parameter | Estimate | 95% CI | z, P |

| 1 | IQ: β 1 | 0.115 | 0.03, 0.22 (0.044) | 2.59, 0.0096 ** |

| Uncinate SL: β 2 | 0.068 | −0.15, 0.32 (0.129) | 0.52, 0.600 | |

| 2 | Fornix SL: β 3 | 0.507 | −0.19, 1.14 (0.340) | 1.49, 0.136 |

| R 2 p | 0.14 | |||

| 9-Step Temporal Memory: Percentage Correct | ||||

| Model | Parameter | Estimate | 95% CI (Std. Err) | z, P |

| 1 | IQ: β 1 | 0.112 | 0.01, 0.22 (0.042) | 2.65, 0.008** |

| Uncinate SL: β 2 | 0.042 | −0.20, 0.27 (0.124) | 0.34, 0.734 | |

| 2 | Fornix SL: β 3 | 0.804 | 0.02, 1.58 (0.328) | 2.45, 0.014* |

| R 2 p | 0.17 | |||

| Source Memory: Source and Fact Percentage Correct | ||||

| Model | Parameter | Estimate | 95% CI | z, P |

| 1 | IQ: β 1 | −0.038 | −0.13, 0.07 (0.041) | −0.93, 0.354 |

| Uncinate SL: β 2 | 0.258 | 0.04, 0.47 (0.123) | 2.09, 0.036* | |

| 2 | Fornix SL: β 3 | 0.742 | 0.01, 1.42 (0.325) | 2.29, 0.022* |

| R 2 p | 0.16 | |||

| Gist Memory Models | ||||

| CMS Immediate Recall for Thematic Units: Percentage Correct | ||||

| Model | Parameter | Estimate | 95% CI (Std. Err) | z, P |

| 1 | IQ: β 1 | 0.041 | −0.01, 0.10 (0.027) | 1.54, 0.124 |

| Uncinate SL: β 2 | 0.099 | −0.09, 0.30 (0.079) | 1.25, 0.210 | |

| 2 | Fornix SL: β 3 | 0.415 | 0.001, 0.81 (0.209) | 1.99, 0.047* |

| R 2 p | 0.12 | |||

| CMS 1 -h Delayed Recall for Thematic Units: Percentage Correct | ||||

| Model | Parameter | Estimate | 95% CI (Std. Err) | z, P |

| 1 | IQ: β 1 | 0.025 | −0.05, 0.11 (0.034) | 0.73, 0.466 |

| Uncinate SL: β 2 | 0.039 | −0.16, 0.25 (0.098) | 0.39, 0.693 | |

| 2 | Fornix SL: β 3 | 0.657 | 0.06, 1.15 (0.264) | 2.49, 0.013* |

| R 2 p | 0.07 | |||

| CMS 1-Week Delayed Recall for Thematic Units: Percentage Correct | ||||

| Model | Parameter | Estimate | 95% CI (Std. Err) | z, P |

| 1 | IQ: β 1 | 0.066 | −0.001, 0.14 (0.032) | 2.15, 0.032* |

| Uncinate SL: β 2 | 0.047 | −0.12, 0.24 (0.090) | 0.53, 0.597 | |

| 2 | Fornix SL: β 3 | 0.413 | −0.11, 0.84 (0.238) | 1.74, 0.082 |

| R 2 p | 0.10 | |||

| Source Memory Task Fact Recall & Recognition: Percentage Correct | ||||

| Model | Parameter | Estimate | 95% CI (Std. Err) | z, P |

| 1 | IQ: β 1 | −0.008 | −0.09, 0.08 (0.042) | −0.21, 0.838 |

| Uncinate SL: β 2 | 0.209 | −0.04, 0.44 (0.124) | 1.69, 0.092 | |

| 2 | Fornix SL: β 3 | 0.662 | −0.03, 1.31 (0.323) | 2.05, 0.041* |

| R 2 p | 0.09 | |||

* P < 0.05.

** P < 0.01.

Fornix white matter and memory

The fornix appeared to play a robust role in children’s episodic memory. Results revealed a significant positive relation between fornix macrostructure and microstructure (see Fig. 1c) across all memory measures, including both detailed and general aspects of story recall, source memory, and temporal memory.

Episodic and gist memory

With respect to the verbatim aspect of memory in the CMS, children’s immediate recall was significantly associated with fornix SL. At a 1-h delay, individual differences in fornix FA and fornix FW were significantly correlated with performance. Fornix SL was no longer significantly associated with memory after a 1-week delay. However, fornix FA and FW remained significant. The fornix also appears to play a robust role in children’s gist memory performance in the CMS. Immediate recall on the thematic aspects memory in the CMS significantly correlated with fornix SL. Furthermore, individual differences in fornix SL and FA were associated with immediate recall and delayed recall (1-h delay). Finally, after a 1-week delay, significant relations with fornix FA and FW remained.

Fact and source memory

Individual differences in fornix SL and fornix FA were significantly related to fact and source memory accuracy. In regard to memory for novel facts, there was also a significant relation with fornix SL and fornix FA.

Temporal memory

Similar to source memory, both fornix SL and FA were significantly associated with temporal memory performance.

Uncinate fasciculus white matter and memory

In contrast to the fornix, the uncinate SL, FA, and FAt were not associated with any of the memory metrics. However, there was a consistent significant relation between uncinate FW and all memory measures. It is important to note that this index shows an inverse relation, such that the less extracellular FW contamination surrounding the tract, the better the memory performance on a given task.

Correlations between memory performance and ventricular volume

In reporting on the associations between tract-specific extracellular FW and memory performance, it is important to consider whether this relation is due to differences at the level of the white-matter bundles under study, or if this effect can be accounted for by overall ventricular volume more generally. We found no evidence for the latter: bivariate Pearson correlations between ventricular volume and memory performance for episodic and gist measures revealed no significant relation. Also, ventricular size did not increase/decrease with age in our sample.

General discussion

The goal of the current study was to examine the relations between fornix white matter and memory performance in a developmental cohort, ages 4–8 years. We took a distinct approach by measuring both white matter macrostructure (e.g. SL) and microstructure and by characterizing multiple facets of episodic memory capacities in the same children. For microstructure, we parsed the different contributions of forniceal FAt and FW volume fraction to understand the associations of forniceal FA with memory performance at a higher degree of granularity. The commonly used diffusion metric, FA, can be thought of as a nonlinear composite score containing both FAt and extracellular FW. Thus, in the current analyses, we were able to tease apart which aspect of FA is most relevant in the domain of memory competency for this developmental cohort.

First, we asked whether fornix macrostructure and microstructure varied with age, as has been reported by prior investigators as described in Table 1. We found that the number of SL, tract volume, and FA all increased between the ages of 4–8. If the literature is taken as a whole, there is now strong and consistent evidence that FA, the most commonly used measure of microstructure, increases with developmental age. In addition, our study and that of Dimond et al. (2020) show that fornix macrostructure also matures during early childhood.

Second, we asked whether there was any relation between fornix white matter and memory performance across a range of tasks. We found significant positive correlations between individual differences in the fornix (see Fig. 1c) across all memory measures, including both detailed and general aspects of story recall, source memory, and temporal memory. Thus far, only two other developmental studies (Wendelken et al. 2015; Ngo et al. 2017) examined the fornix and memory performance (see Table 1). Neither one of the studies detected an association between the fornix and memory performance in children, As mentioned, we speculate that the restricted age range in early childhood (Ngo et al. 2017) and task characteristics (Wendelken et al. 2015) may explain why the fornix-memory associations were not detected in these studies. It is also possible that these null findings resulted, in part, from technical challenges: the fornix is a difficult structure to image due to its high curvature and placement in the third ventricle. This explanation is support by a robust literature linking fornix diffusion metrics to memory decline in aging and Alzheimer’s dementia (Benear et al. 2020). The fact that we found positive associations between the fornix and memory across a range of tasks that not only had differences in material and nature of recollection, but also the length of the delay period involved provides an unparalleled portrait of the robust relation between the fornix and memory performance in children.

Although we expected to find a dissociation between detailed and gist-like aspects of episodic memory, and between semantic and episodic memory in regard to the fornix, we did not observe this. The number of fornix SL and fornix FA was significantly correlated with fact memory (as well as source memory accuracy) in children. This finding is inconsistent with the view that the fornix supports episodic forms of memory such as recall and autobiographical recollection, but not semantic forms of memory, such as fact memory (Hodgetts et al. 2017). There is reason to be cautious against such dichotomous descriptions of memory systems, however. Decades ago, Tulving (1972) noted that the acquisition of a new episodic memory is affected by information in semantic memory, such as the degree of association between two concepts. Later, he reminded researchers that semantic and episodic memory are interdependent and that this interdependence is variable such that one can find situations in which the interdependence is pronounced or other situations in which it is negligible (Tulving 1983; see also Greenberg and Verfaellie 2010; Renoult et al. 2019). Indeed, post-hoc analyses revealed that there was high intercorrelation between performance on our episodic and semantic memory measures, rendering it improbable that we could have expected to detect a gist/episodic dissociation (see Supplementary Table 6).

One variable that may affect this interdependence is age. Children accumulate semantic knowledge long before they are able to lay down episodic memories (Newcombe et al. 2007; Keresztes et al. 2018). In the age cohort tested in this study, robust semantic knowledge may have provided a scaffold that boosted the abilities of a still-fragile episodic memory system. We acknowledge that this view is speculative. The extant literature on the fornix overwhelmingly points toward a role for this white matter tract in supporting network operations linked to navigation, episodic memory, and motivated memory (Benear et al. 2020). Investigations of semantic knowledge or semanticized memories are rare. Thus, future researchers should investigate the role of the fornix in semantic memory development more deeply by examining semantic memory acquisition across a range of ages and relating this to fornix diffusion imaging metrics.

FW and the fornix

FA of forniceal fibers did not seem to matter as much as the extent to which this white matter tract is contaminated by CSF, which is evinced by the fact that FW but not FAt predicted memory performance. The elimination of a scalar-related effect post-FWC has also been observed in aging cohorts (Metzler-Baddeley et al. 2012). Mechanistically speaking, this suggests that with age, tracts become “beefier,” taking up more space and thus decreasing extracellular FW, which we posit is the driving force underpinning some variance in age-related enhancements in memory performance. This age-related difference may be due to some combination of increased myelination, glial cell proliferation, and/or vascular enhancements. Due to the fact that FA(t) has been linked to underlying myelination (Kochunov et al. 2012), and no relation was observed between FAt and age or memory performance, it is least likely that increased beefiness is due to individual and age related changes in myelination. Furthermore, from the lack of FAt findings, we may also conjecture that the current findings are not the result of changes in axonal diameter or density. However, the case for age-related gains in forniceal beefiness and its implications for memory competence is echoed in the current findings that fornix streamline count increases with age and is also proportionately associated with behavioral performance on memory measures across the board. While SL should not be conflated with “fiber density” per se, due to the many extraneous factors influencing streamline indices (Jones et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2021), it points to the possibility that perhaps, increases in axonal branching or dendritic arborization contribute to age-related gains in both memory performance and tract-beefiness. This interpretation is made stronger still by our finding that fornix tract volume in voxels increases with age, while overall ICV does not, further pointing to the significance of changes in fornix beefiness in this developmental cohort. However, it is not possible to pin down with any degree of certainty what precisely is resulting in decreased FW volume fraction around the fornix as age and memory performance ascends, as this index is unto itself nonspecific in nature.

The uncinate fasciculus and memory performance

The uncinate fasciculus creates a direct structural connection between the temporal pole, entorhinal cortex, perirhinal cortex, the uncus and amygdala, and inferior-lateral and polar aspects of the frontal lobes (Von Der Heide et al. 2013). Some aspects of memory decline following damage to the adult uncinate, while other aspects of memory remain completely intact. For instance, memory for people’s names and memory for low-frequency concepts decline following uncinate damage, while performance on standard episodic memory tasks remains intact (reviewed in Von Der Heide et al. 2013). Our laboratory and others have reported correlations between variation in uncinate microstructure and adult performance on associative learning tasks including a face-name learning, face-place learning, and object-location learning task (Thomas et al. 2015; Alm et al. 2016; Metoki et al. 2017). All of the tasks that correlate with uncinate microstructure require one to make fine discriminations between retrieved options (e.g. “Is her name Jane or Jan?”). This type of learning relates to the established functions of the anterior temporal lobe/perirhinal cortex in concept retrieval and item discrimination (Chiou and Lambon Ralph 2016).

The developmental literature on the uncinate is very limited even though the uncinate is an intriguing tract from a developmental standpoint, having an extremely protracted development (Lebel et al. 2008; Lebel and Beaulieu 2011; Olson et al. 2015). In the data reported here, we did not find a robust association between individual differences in episodic memory or gist memory for uncinate fasciculus macrostructure or most microstructure measures. However, there was a negative relation with FW. Mabbott et al. (2009) tested 22 children and adolescents and found that FA in the left uncinate correlated with cued and free recall performance for word lists. A study by Wendelken et al. (2015) found relations between left uncinate FA and performance on a controlled retrieval task in children aged 7–11. At a conceptual level, we failed to replicate these findings. This may reflect the fact that our sample is younger than those tested previously. It is also possible that the ideal task for revealing a relation taps fine-grained discrimination at the level of retrieval (not perception) to a degree that was not present in our tasks.

Limitations

The current study has some methodological limitations. First, the data were collected over several years and were part of a larger study; thus, the resolution is relatively low, and the voxels are nonisotropic. Nonisotropic voxels can affect tractography resolution, adding noise to outcome measures due to partial volume effects (Oouchi et al. 2007). Fortunately, our sample size was large enough, and our pipeline was robust enough that this problem did not hamper our ability to find significant effects. We would advise researchers to use isotropic voxels in future dMRI studies. In addition, these data were acquired with a single-shell diffusion-weighted imaging acquisition, which, with the help of a sophisticated data regularization scheme, allowed for the performance of a FWC. However, it did not permit for the implementation of a NODDI analysis. The quantification of neurite density would be an interesting avenue to explore in a developmental cohort, as it would further elucidate the nature of the macrostructural changes that were observed with age. That is, we were unable to explore whether changes in forniceal macrostructure were underpinned by age-related associations with neurite density. Furthermore, our data were limited by the absence of field-map acquisition in the diffusion sequence that was used for this study. As a result, it was not possible to perform an FSL topup correction for susceptibility artifacts.

Second, readers must keep in mind that there are many factors influencing the number of SLs that are generated by the probabilistic algorithm, such as tract curvature, myelination, length, branching, and surrounding signal-to-noise-ratio, among other factors (Jones et al. 2013). Because of this, we interpret the streamline results with caution, and stress the fact that SL, while highly correlated with volumetric measures of tract macrostructure, should be interpreted as a macrostructural proxy.

Third, the current study does not attempt to address any potential sex differences in memory performance. We did not have measures of puberty (given the relatively young age of the sample overall), and given that girls go through puberty earlier and mature more quickly, it would be difficult to interpret any sex differences in memory performance, if they were found. There is evidence from rodents that sex hormones affect myelination with female rodents having relatively higher levels in frontal cortex (Darling and Daniel 2019). Future researchers interested in sex differences in memory in developmental cohorts would be advised to gather hormone data.

Fourth, given that our questions regarding the link between fornix and memory in a developmental cohort were theoretically driven, no steps were taken to correct for multiple comparisons. To combat the issue of potential type I error due to the sheer volume of models that were run, bootstrapped confidence intervals were constructed for each model around each beta weight using 10,000 iterations. While computationally intensive, such a high seed number was used in order to yield more stable parameter estimates around the 95% confidence interval. This approach is indispensable for assessing the interpretability of the current findings, as a few significant regressors yielded 95% confidence around their beta-weights that contain 0, suggesting that if this study is recapitulated, certain findings may not be replicable (see italicized confidence intervals in Supplementary Tables 3–5).

Conclusion

Our study suggests clear associations between memory performances and fornix white matter connectivity in early and middle childhood—a crucial age window for typical memory development. Interindividual variation in the fornix macrostructure tracked performances on key aspects of episodic memory abilities. The focus of the current study is not exhaustive in terms of the structural connectivity relevant to episodic memory in young children. In adults, episodic memory relies on the coordination of multiple brain regions (Barnett et al. 2021). Thus, the structural connectivity underlying memory development goes far beyond a single tract. However, it is clear from our study, as well as a robust literature in nonhuman animals described earlier, that the fornix is likely the single most important white matter tract for episodic memory. These findings suggest that the robustness of interregion communication between structures implicated in memory processes is key to understanding the neural underpinnings of long-term forms of memory during this developmental period.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Huiling Peng for her assistance with diffusion imaging analysis. We would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their careful review and helpful suggestions.

Contributor Information

Linda J Hoffman, Department of Psychology, Temple University, 1701 North 13th St., Philadelphia, PA 19122, USA.

Chi T Ngo, Center for Lifespan Psychology, Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Lentzeallee 94, 14195 Berlin, Germany.

Kelsey L Canada, Institute of Gerontology, Wayne State University, 87 East Ferry St., Detroit, MI 48202, USA.

Ofer Pasternak, Department of Psychiatry, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 75 Francis St., Boston, MA 02115, USA; Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 75 Francis St., Boston MA 02115, USA.

Fan Zhang, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 75 Francis St., Boston MA 02115, USA.

Tracy Riggins, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, 4094 Campus Dr., College Park, MD, 20742, USA.

Ingrid R Olson, Department of Psychology, Temple University, 1701 North 13th St., Philadelphia, PA 19122, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grants to IRO [R01 MH091113; R01 HD099165; R21 HD098509; R56MH091113; State of Pennsylvania, Dept. of Health CURE grant: “Mechanisms and treatment strategies to counter addiction susceptibility post TBI”] and TR [R01 HD079518]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Alm KH, Rolheiser T, Olson IR. Inter-individual variation in fronto-temporal connectivity predicts the ability to learn different types of associations. NeuroImage. 2016:132:213–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral D, Lavenex P. Hippocampal neuroanatomy. In: Andersen P, Morris R, Amaral D, Bliss T, O’Keefe J, editors. The hippocampus book. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; 2007. pp. 37–114 [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JLR, Sotiropoulos SN. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. NeuroImage. 2016:125:1063–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JLR, Skare S, Ashburner J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. NeuroImage. 2003:20(2):870–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonenko D, Kulzow N, Cesarz ME, Schindler K, Grittner U, Floel A. Hippocampal pathway plasticity is associated with the ability to form novel memories in older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016:8:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolova LG, Green AE, Babakchanian S, Hwang KS, Chou YY, Toga AW, Thompson PM. Hippocampal atrophy and ventricular enlargement in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012:26(1):17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett AJ, Reilly W, Dimsdale-Zucker HR, Mizrak E, Reagh Z, Ranganath C. Intrinsic connectivity reveals functionally distinct cortico-hippocampal networks in the human brain. PLoS Biol. 2021:19(6):e3001275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer PJ. Memory. In: Zelazo PD, editors. Oxford handbook of developmental psychology: body and mind. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; 2013. pp. 505–541 [Google Scholar]

- Bauer PJ, Larkina M, Deocampo J. Early memory development. In: Goswami U, editors. The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of childhood cognitive development. Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ; 2011. pp. 153–179. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens TE, Berg HJ, Jbabdi S, Rushworth MF, Woolrich MW. Probabilistic diffusion tractography with multiple fibre orientations: what can we gain? NeuroImage. 2007:34(1):144–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benear SL, Ngo CT, Olson IR. Dissecting the fornix in basic memory processes and neuropsychiatric disease: a review. Brain Connect. 2020:10(7):331–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett IJ, Stark CE. Mnemonic discrimination relates to perforant path integrity: an ultra-high resolution diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2016:129:107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett IJ, Huffman DJ, Stark CE. Limbic tract integrity contributes to pattern separation performance across the lifespan. Cereb Cortex. 2015:25(9):2988–2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canada KL, Botdorf M, Riggins T. Longitudinal development of hippocampal subregions from early- to mid-childhood. Hippocampus. 2020:30(10):1098–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canada KL, Pathman T, Riggins T. Longitudinal development of memory for temporal order in early to middle childhood. J Genet Psychol. 2020:181(4):237–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canada KL, Hancock GR, Riggins T. Modeling longitudinal changes in hippocampal subfields and relations with memory from early- to mid-childhood. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2021:48:100947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chad JA, Pasternak O, Salat DH, Chen JJ. Re-examining age-related differences in white matter microstructure with free-water corrected diffusion tensor imaging. Neurobiol Aging. 2018:71:161–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou R, Lambon Ralph MA. The anterior temporal cortex is a primary semantic source of top-down influences on object recognition. Cortex. 2016:79:75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MJ. Children’s memory scale. San Antonio (TX): The Psychological Corporation; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Dalton CM, Miszkiel KA, O'Connor PW, Plant GT, Rice GP, Miller DH. Ventricular enlargement in MS: one-year change at various stages of disease. Neurology. 2006:66(5):693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling JS, Daniel JM. Pubertal hormones mediate sex differences in levels of myelin basic protein in the orbitofrontal cortex of adult rats. Neuroscience. 2019:406:487–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin JP, Moita MP, de Brabander HM, Joosten RN. Place and response learning of rats in a Morris water maze: differential effects of fimbria fornix and medial prefrontal cortex lesions. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2001:75(2):164–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimond D, Rohr CS, Smith RE, Dhollander T, Cho I, Lebel C, Dewey D, Connelly A, Bray S. Early childhood development of white matter fiber density and morphology. NeuroImage. 2020:210:116552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummey AB, Newcombe NS. Developmental changes in source memory. Dev Sci. 2002:4(4):502–513. [Google Scholar]

- Ennaceur A, Aggleton JP. The effects of neurotoxic lesions of the perirhinal cortex combined to fornix transection on object recognition memory in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 1997:88(2):181–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari SLP, Cribari-Neto F. Beta regression for modelling rates and proportions. J Appl Stat. 2004:31(7):799–815. [Google Scholar]

- Foster CM, Kennedy KM, Hoagey DA, Rodrigue KM. The role of hippocampal subfield volume and fornix microstructure in episodic memory across the lifespan. Hippocampus. 2019:29(12):1206–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng F, Botdorf M, Riggins T. How behavior shapes the brain and the brain shapes behavior: insights from memory development. J Neurosci. 2021:41(5):981–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Remiers E, Martin-Gonzalez C, Romero-Acevedo L, Quintero-Platt G, Gonzalez-Arnay E, Santolaria-Fernandez F. Effects of alcohol on the corpus callosum. In: Preedy VR, editors. Neruoscience of alcohol: mechanisms and treatment. Academic Press: Cambridge, MA; 2019. pp. 143–152 [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg DL, Verfaellie M. Interdependence of episodic and semantic memory: evidence from neuropsychology. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010:16(5):748–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunbey HP, Ercan K, Findikoglu AS, Bulut HT, Karaoglanoglu M, Arslan H. The limbic degradation of aging brain: a quantitative analysis with diffusion tensor imaging. Sci World J. 2014:2014:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh R, Segal M. Complete transection of the fornix and reversal of position habit in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1972:8(6):1051–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgetts CJ, Postans M, Shine JP, Jones DK, Lawrence AD, Graham KS. Dissociable roles of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus and fornix in face and place perception. elife. 2015:4:1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgetts CJ, Postans M, Warne N, Varnava A, Lawrence AD, Graham KS. Distinct contributions of the fornix and inferior longitudinal fasciculus to episodic and semantic autobiographical memory. Cortex. 2017:94:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgetts CJ, Shine JP, Williams H, Postans M, Sims R, Williams J, Lawrence AD, Graham KS. Increased posterior default mode network activity and structural connectivity in young adult APOE-epsilon4 carriers: a multimodal imaging investigation. Neurobiol Aging. 2019:73:82–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H. Delineating neural structures of developmental human brains with diffusion tensor imaging. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010:10:135–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DK, Knosche TR, Turner R. White matter integrity, fiber count, and other fallacies: the do's and don'ts of diffusion MRI. NeuroImage. 2013:73:239–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci K, Schwarz CG, Reid RI, Przybelski SA, Lesnick TG, Zuk SM, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Lowe V, Machulda MM, et al. White matter integrity determined with diffusion tensor imaging in older adults without dementia: influence of amyloid load and neurodegeneration. JAMA Neurol. 2014:71(12):1547–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann LK, Baur V, Hanggi J, Jancke L, Piccirelli M, Kollias S, Schnyder U, Pasternak O, Martin-Soelch C, Milos G. Fornix under water? Ventricular enlargement biases forniceal diffusion magnetic resonance imaging indices in anorexia nervosa. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2017:2(5):430–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keresztes A, Ngo CT, Lindenberger U, Werkle-Bergner M, Newcombe NS. Hippocampal maturation drives memory from generalization to specificity. Trends Cogn Sci. 2018:22(8):676–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochunov P, Williamson DE, Lancaster J, Fox P, Cornell J, Blangero J, Glahn DC. Fractional anisotropy of water diffusion in cerebral white matter across the lifespan. Neurobiol Aging. 2012:33(1):9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok SC, Buckley MJ. Fornix transection impairs exploration but not locomotion in ambulatory macaque monkeys. Hippocampus. 2006:16(8):655–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel C, Beaulieu C. Longitudinal development of human brain wiring continues from childhood into adulthood. J Neurosci. 2011:31(30):10937–10947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel C, Walker L, Leemans A, Phillips L, Beaulieu C. Microstructural maturation of the human brain from childhood to adulthood. NeuroImage. 2008:40(3):1044–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel C, Treit S, Beaulieu C. A review of diffusion MRI of typical white matter development from early childhood to young adulthood. NMR Biomed. 2019:32(4):e3778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay DS, Johnson MK, Kwon P. Developmental changes in memory source monitoring. J Exp Child Psychol. 1991:52(3):297–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabbott DJ, Rovet J, Noseworthy MD, Smith ML, Rockel C. The relations between white matter and declarative memory in older children and adolescents. Brain Res. 2009:1294:80–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metoki A, Alm KH, Wang Y, Ngo CT, Olson IR. Never forget a name: white matter connectivity predicts person memory. Brain Struct Funct. 2017:222(9):4187–4201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler-Baddeley C, Jones DK, Belaroussi B, Aggleton JP, O'Sullivan MJ. Frontotemporal connections in episodic memory and aging: a diffusion MRI tractography study. J Neurosci. 2011:31(37):13236–13245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler-Baddeley C, O'Sullivan MJ, Bells S, Pasternak O, Jones DK. How and how not to correct for CSF-contamination in diffusion MRI. NeuroImage. 2012:59(2):1394–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JF, Neufang M, Solway A, Brandt A, Trippel M, Mader I, Hefft S, Merkow M, Polyn SM, Jacobs J, et al. Neural activity in human hippocampal formation reveals the spatial context of retrieved memories. Science. 2013:342(6162):1111–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray EA, Davidson M, Gaffan D, Olton DS, Suomi S. Effects of fornix transection and cingulate cortical ablation on spatial memory in rhesus monkeys. Exp Brain Res. 1989:74(1):173–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcombe NS, Lloyd ME, Ratliff KR. Development of episodic and autobiographical memory: a cognitive neuroscience perspective. In: Kali RV, editors. Advances in child development and behavior. Academic Press: Cambridge, MA; 2007. pp. 37–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcombe NS, Benear SL, Ngo CT, Olson IR. Memory in infancy and childhood. In: Kahana M, Wagner A, editors. Handbook on human memory. Temple University: Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; 2022. in press [Google Scholar]

- Ngo CT, Alm KH, Metoki A, Hampton W, Riggins T, Newcombe NS, Olson IR. White matter structural connectivity and episodic memory in early childhood. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2017:28:41–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo CT, Newcombe NS, Olson IR. The ontogeny of relational memory and pattern separation. Dev Sci. 2018:21(2):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi K, Lyketsos CG. Alzheimer's disease and the fornix. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014:6:241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe J, Nadel L, Keightley S, Kill D. Fornix lesions selectively abolish place learning in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1975:48(1):152–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson IR, McCoy D, Klobusicky E, Ross LA. Social cognition and the anterior temporal lobes: a review and theoretical framework. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2013:8(2):123–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson IR, Von Der Heide RJ, Alm KH, Vyas G. Development of the uncinate fasciculus: implications for theory and developmental disorders. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2015:14:50–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oouchi H, Yamada K, Sakai K, Kizu O, Kubota T, Ito H, Nishimura T. Diffusion anisotropy measurement of brain white matter is affected by voxel size: underestimation occurs in areas with crossing fibers. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007:28(6):1102–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak O, Sochen N, Gur Y, Intrator N, Assaf Y. Free water elimination and mapping from diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009:62(3):717–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathman T, Larkina M, Burch M, Bauer PJ. Young Children's memory for the times of personal past events. J Cogn Dev. 2013:14(1):120–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard L, Cousin S, Guillery-Girard B, Eustache F, Piolino P. How do the different components of episodic memory develop? Role of executive functions and short-term feature-binding abilities. Child Dev. 2012:83(3):1037–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierpaoli C, Jezzard P, Basser PJ, Barnett A, Di Chiro G. Diffusion tensor MR imaging of the human brain. Radiology. 1996:201(3):637–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poreh A, Winocur G, Moscovitch M, Backon M, Goshen E, Ram Z, Feldman Z. Anterograde and retrograde amnesia in a person with bilateral fornix lesions following removal of a colloid cyst. Neuropsychologia. 2006:44(12):2241–2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray NJ, Metzler-Baddeley C, Khondoker MR, Grothe MJ, Teipel S, Wright P, Heinsen H, Jones DK, Aggleton JP, O'Sullivan MJ. Cholinergic basal forebrain structure influences the reconfiguration of white matter connections to support residual memory in mild cognitive impairment. J Neurosci. 2015:35(2):739–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renoult L, Irish M, Moscovitch M, Rugg MD. From knowing to remembering: the semantic-episodic distinction. Trends Cogn Sci. 2019:23(12):1041–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JE, Grohs MN, Dewey D, Lebel C. Global and regional white matter development in early childhood. NeuroImage. 2019:196:49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JE, Long X, Grohs MN, Dewey D, Lebel C. Structural and functional asymmetry of the language network emerge in early childhood. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2019:39:100682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggins T. Longitudinal investigation of source memory reveals different developmental trajectories for item memory and binding. Dev Psychol. 2014:50(2):449–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]