Highlights

-

•

Effects of gas saturation/sparging were studied for sonochemical NO2−/NO3− generation.

-

•

Twelve gas conditions of Ar, O2, N2, and binary mixtures were tested.

-

•

N2:Ar (25:75) resulted in the highest NO2− and NO3− concentrations under all conditions.

-

•

H2O2/NO2−/NO3− related OH radical activity was suggested.

-

•

Gas sparging enhanced the generation of NO2− and NO3− for O2:N2, N2, and N2:Ar.

Keywords: Acoustic cavitation, Gas saturation, Gas sparging, NO2− generation, NO3-generation, Dissolved oxygen

Abstract

The sonochemical generation of NO2− and NO3− is considered to be one of the reasons for the low sonochemical oxidation activity in the presence of N2 in the liquid phase. In this study, the generation characteristics of NO2− and NO3− were investigated using the same 28 kHz sonoreactor and the 12 gas conditions used in Part I of this study. Three gas modes, saturation/closed, saturation/open, and sparging/closed, were applied. N2:Ar (25:75), N2:Ar (50:50), and O2:N2 (25:75) in the saturation/closed mode generated the three highest values of NO2− and NO3−. Ar and O2 were vital for generating relatively large concentrations of NO2− and NO3−. The absorption of N2 from the air resulted in high generation of NO2− and NO3− for Ar 100 % and Ar/O2 mixtures under the saturation/open mode. In addition, gas sparging enhanced the generation of NO2− and NO3− for N2:Ar (25:75), O2:N2 (25:75), and N2 significantly because of the change in the sonochemically active zone and the increase in the mixing intensity in the liquid phase, as discussed in Part I. The ratio of NO3− to NO2− was calculated using their final concentrations, and a ratio higher than 1 was obtained for the condition of Ar 100 %, Ar/O2 mixtures, and O2 100 %, wherein a relatively high oxidation activity was detected. From a summary of the results and findings of previous studies, it was revealed that the observations of NO2− + NO3− could be more appropriate for investigating the NO2− and NO3− generation characteristics. In addition, H2O2/NO2−/NO3− related activity rather than H2O2 activity was suggested to quantify the OH radical activity more appropriately in the presence of N2.

1. Introduction

During acoustic cavitation events, various nitrogen species, including ∙NO, N2O, HNO2, HNO3, and NH3, can be detected in the liquid phase in the presence of dissolved nitrogen (N2) [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. Generally, NO2− and NO3− are detected as sonochemical oxidation products because they are relatively more stable than other generated nitrogen species and accumulate linearly to a certain extent [1], [2], [6], [7], [8], [9]. ∙NO is reported to be the main precursor for NO2− and NO3−, generated from the reactions of ∙O∙, ∙OH, and N2 under ultrasonic irradiation, as shown by the following reactions, which occur in the gas phase (inside cavitational bubbles) [1], [5], [10]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

Homolysis of O2 can occur inside the bubbles at a temperature of several thousand Kelvins owing to relatively low bond dissociation energy (498 kJ/mol). However, homolysis of N2 rarely occurs inside the bubbles because its high bond dissociation energy (945 kJ/mol) implies that it only occurs at temperatures above 10,000 K [5]. The Zeldovich mechanism, which describes the thermal oxidation of gaseous N2 and the generation of ∙NO, also suggests the formation of ∙N by the reaction of N2 and ∙O [1], [11]. In addition, the extended Zeldovich mechanism suggests that Eq. (7) can be obtained at room temperature [11]. Sonochemically generated HNO2 and HNO3 have low pKa values and are present in the form of NO2− and NO3−, respectively, under neutral conditions. As a result of this, the pH of the liquid phase decreases significantly [2], [10]. In addition, NO2− can be further oxidized to NO3− using ∙OH, O2, and H2O2 [1], [2].

Previous research has for decades investigated the sonochemical generation of NO2− and NO3− under various frequencies and gas conditions [1], [2], [3], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]. Significant amounts of NO2− and NO3− could be generated in the presence of N2, considering the generation of H2O2 and the degradation of pollutants [2], [3], [6], [7], [8], [9], which resulted in a remarkable decrease in the availability of oxidizing species such as OH radicals for target oxidation reactions. This is considered one of the main reasons why sonochemical oxidation activity is very low for gas conditions including N2, with the low ratio of specific heat capacity, low solubility, and high thermal conductivity compared to Ar and O2, as discussed in Part I of this study. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the generation characteristics of NO2− and NO3− to enhance the sonochemical oxidation activity. In addition, the comparison between the H2O2 generation and the NO2− and NO3− generation under various mixture conditions of Ar, O2, and N2, which are commonly used in Sonochemistry, has been rarely reported.

In this study, the effects of gas saturation and sparging on the generation of NO2− and NO3− were investigated systematically under three gas modes: saturation/closed, saturation/open, and sparging/closed. The gas conditions of Ar, O2, N2, and binary mixtures were applied, and the generation of NO2− and NO3− was quantitatively analyzed in a 28 kHz sonoreactor equipped with a gas supply system. To compare the generation characteristics of NO2− and NO3−, a summary of the initial linear generation rate and final generated concentrations of NO2− and NO3− under various conditions, using the results and findings of previous studies, was provided.

2. Experimental methods

2.1. Chemicals

Nitrite ion standard solution (NaNO2) and nitrate ion standard solution (NaNO3) were acquired from Sigma–Aldrich Co. (USA). Sodium nitrite, sodium nitrate, and tert-butanol were purchased from Samchun Pure Chemical Co. ltd. (KOR). Potassium biphthalate (C8H5KO4) was acquired from Daejung Chemical &Metals Co. ltd. (KOR). Potassium iodide (KI) and ammonium molybdate [(NH4)2MoO4] were purchased from Junsei Chemical Co. ltd. (JPN). All chemicals were used as received.

2.2. Sonoreactor and gas supply

An acrylic cylindrical sonoreactor was used in this study, equipped with a 28 kHz transducer module (Mirae Ultrasonic Tech., Bucheon, KOR) placed at the bottom. The liquid height and volume were 4.0 λ (53.6 mm) and 3.65 L, respectively. The temperature of the liquid body was maintained at 20 ℃ using a cooling system. The working electrical power was 100 W and the ultrasonic power, also called calorimetric power, was 55 W. The details of the sonoreactor are described in Part I of this study.

Three modes of gas saturation/sparging were tested using N2, O2, and Ar: 1) Saturation/Closed mode for twelve gas conditions including Ar, Ar:O2 (75:25), Ar:O2 (50:50), Ar:O2 (25:75), O2, O2:N2 (75:25), O2:N2 (50:50), O2:N2 (25:75), N2, N2:Ar (75:25), N2:Ar (50:50), and N2:Ar (25:75). 2) Saturation/Open mode for seven conditions including Ar, Ar:O2 (75:25), Ar:O2 (25:75), O2, O2:N2 (75:25), N2, and N2:Ar (25:75). 3) Sparging/Open mode for six conditions including Ar, Ar:O2 (75:25), O2, O2:N2 (25:75), N2, and N2:Ar (25:75). Gas was delivered into the liquid body using a microporous glass sparger (pore size: 20–30 μm) equipped with a glass pipe, the sparger was placed 1 cm above the reactor bottom. The dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration was measured before and after each test to estimate the degree of gas saturation in the liquid body using a DO meter (ProODO; YSI Inc., USA). The details of the gas supply are described in Part I.

2.3. Quantification of sonochemical reactions

The concentrations of nitrite (NO2−) and nitrate (NO3−) ions were measured using an ion chromatography (IC) system (ICS-2100; Dionex, USA) equipped with an autosampler (AS-DV; Dionex, USA) [2]. The concentration of sonochemically generated H2O2 was spectrophotometrically analyzed using solution A (0.10 M potassium biphthalate), solution B (0.4 M KI, 0.06 M sodium hydroxide, and 10-4 M ammonium molybdate), and a UV–vis spectrophotometer (Vibra S60, Biochrom ltd., UK) [22], [23].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Gas saturation effect on NO2− and NO3− generation

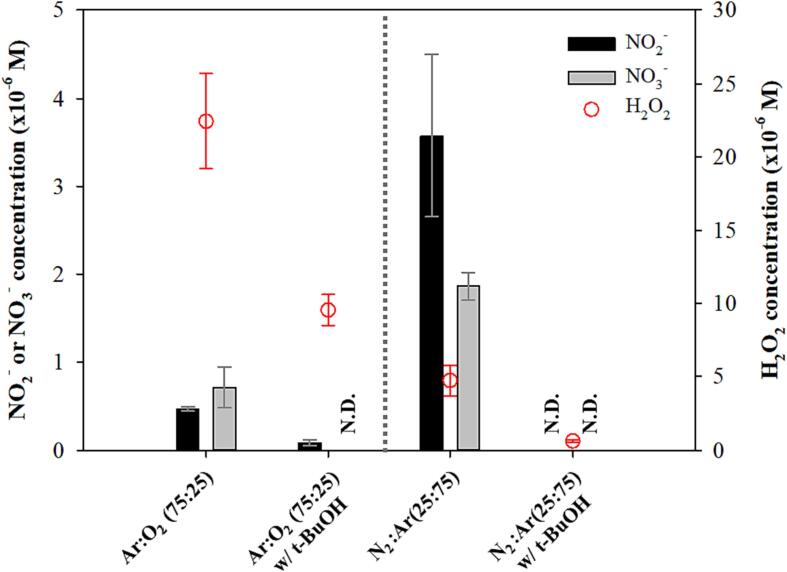

The generation of H2O2, NO2−, and NO3− under the three gas modes, saturation/closed, saturation/open, and sparging/closed, was investigated using the same sonoreactor system and the same gas conditions (N2, O2, Ar, and their binary mixtures) used in Part I. For the saturation/open and sparging/closed modes, selected gas conditions were applied. The concentration of H2O2 represents the cavitation-induced oxidizing radical activity, especially when using OH radicals, which are available for target oxidation reactions, while the concentrations of NO2− and NO3− represent undesirable consumption of the oxidizing radicals in the presence of dissolved N2 in the liquid phase. The concentrations of H2O2, NO2−, and NO3− increased linearly in this study for all the applied modes, and the final concentration of the sonochemical products for the saturation/closed mode is shown in Fig. 1. The irradiation duration was 90 min. The variations in the DO concentration before and after ultrasonic irradiation for the three gas modes are summarized in Table 1. The sonochemical generation characteristics of NO2− and NO3− under various gas conditions in previous studies are presented in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Sonochemically generated concentrations of NO2−, NO3−. NO2− + NO3− and H2O2 under the saturation/closed mode using Ar, O2, and N2 for 28 kHz. The irradiation duration was 90 min.

Table 1.

Variation of DO concentrations before and after ultrasonic irradiation for various gas saturation and sparging conditions with a DO saturation concentration of 9.1 mg/L at 20 °C.

| Gas modes | Ar | Ar:O2 (75:25) | Ar:O2 (50:50) | Ar:O2 (25:75) | O2 | O2:N2 (75:25) | O2:N2 (50:50) | O2:N2 (25:75) | N2 | N2:Ar (75:25) | N2:Ar (50:50) | N2:Ar (25:75) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturation/Closed | DO0* (mg/L) | 0.5 | 12.1 | 22.8 | 32.9 | 43.8 | 32.8 | 22.5 | 11.0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| DO90* (mg/L) | 1.0 | 10.6 | 19.9 | 28.9 | 38.4 | 29.1 | 20.6 | 10.2 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.6 | |

| ΔDO** | 0.5 | -1.4 | -2.9 | -4.0 | -5.4 | -3.8 | -1.9 | -0.7 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | |

| Saturation/Open | DO0 (mg/L) | 0.4 | 11.1 | - | 31.1 | 40.3 | 31.1 | - | - | 0.4 | - | - | 0.4 |

| DO90 (mg/L) | 3.0 | 9.6 | - | 18.8 | 23.6 | 18.7 | - | - | 5.0 | - | - | 4.6 | |

| ΔDO | 2.6 | -1.6 | - | -12.3 | -16.7 | -12.4 | - | - | 4.6 | - | - | 4.2 | |

| Sparging/Closed | DO0 (mg/L) | 0.4 | 11.3 | - | - | 41.0 | - | - | 11.0 | 0.4 | - | - | 0.3 |

| DO90 (mg/L) | 0.7 | 11.0 | - | - | 38.2 | - | - | 10.7 | 0.7 | - | - | 0.6 | |

| ΔDO | 0.3 | -0.3 | - | - | -2.8 | - | - | -0.3 | 0.4 | - | - | 0.3 | |

* DO0 and DO90 represent DO concentrations before and after 90 min of irradiation, respectively.

** ΔDO = DO90-DO0.

Table 2.

Sonochemical generation characteristics of NO2− and NO3− under various gas conditions. Some numerical data including concentrations and their corresponding irradiation durations were extracted using WebPlotDigitizer (https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer/).

| Experimental conditions | Sonochemical generation of NO2- and NO3- |

Description/Comments | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial linear generation rate | Final concentration | |||

| 300 kHz | - Ar:N2O (96:4) | - NO2- and NO3- were not detected for Ar 100%. | [15] | |

| I=3.5 W/cm2 | NO2-: 940 μM@10 min | - The irradiation time for O2/N2O was not provided. | ||

| VL = 20 mL | NO3-: 680 μM@10 min | - The peak of NO2- + NO3- was observed for O2/N2O (90:10). | ||

| vessel submerged in US bath | NH3: 70 μM@10 min | |||

| gas saturated (Ar:N2O (96:4), N2O/O2 mixtures) | NO3-/NO2- = 0.72 | |||

| NO2-+NO3- : 162 μM/min | ||||

| - O2/N2O mixture: NO2-+NO3- | ||||

| (98:2): 460 μM | ||||

| (90:10): 1,200 μM | ||||

| (50:50): 60 μM | ||||

| 300 kHz | Overall generation rate of NO2-+NO3- | - N2 (the mixture of 14,14N2 and 15,15N2 (1:1)) was used and sonochemical formation of 14N15N was observed. | [3] | |

| VL = 37.5 mL | - Ar/N2 mixture | - The highest generation rate for NO2-+NO3- and NH3 was observed for Ar:N2 (60:40) and Ar:N2 (40:60). | ||

| Ar/N2 saturated | Ar 100%: not detected | - As the ratio of N2 in the mixture increased, the generation rates of H2, H2O2, and O2 decreased significantly. | ||

| (80:20): 3.9 μM/min | ||||

| (60:40), (40:60): 5.9 μM/min | ||||

| (20:80): 3.9 μM/min | ||||

| N2 100%: 1.6 μM/min | ||||

| 50 kHz | - air saturated | - air saturated | - •NO, the precursor of NO2- and NO3-, generation was quantified using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) techniques. | [5] |

| VL = 0.8 mL | •NO: 0.9 μM/2 min | NO2-: 5.1 μM@5 min | - The cause for no NO3- being detected, was considered as short US irradiation time. | |

| vessel submerged in US bath | NO3-: not detected | - The EPR method only quantified •NO generated in bulk phase and 45% of •NO was detected considering the generation of NO2-. The other portion of •NO might be generated in the interior or interface of the cavitation bubbles. | ||

| air saturated, gas sparging | •NO: 3.4 μM@ 10 min | - The highest generation of •NO was observed at N2:O2 (90-78:10-22) and N2:Ar (29-57:71:43). | ||

| - •NO for N2/O2 mixture | ||||

| N2 100%: 1.1 μM@5 min | ||||

| (90:10): 2.1 μM@5 min | ||||

| (85:15): 2.1 μM@5 min | ||||

| O2 100%: not detected | ||||

| - •NO for N2/Ar mixture | ||||

| N2 100%: 0.75 μM@5 min | ||||

| (43:57): 5.6 μM@5 min | ||||

| Ar 100%: not detected | ||||

| 35 kHz | - air | - air | - NO2- and NO3- were not detected for O2 100% and Ar 100%. | [14] |

| VL = 650 mL | NO2-: 7.9 μM/30 min | NO2-: 15 μM@60 min | - NO3- was detected after 10 min for N2. | |

| vessel submerged in US bath | NO3-: 5.8 μM/60 min | NO3-: 5.8 μM@60 min | - As ionic strength increased in terms of NaCl concentration from 0 to 15%, the generation of NO2- and NO3- increased and H2O2 generation decreased. For higher ionic strength the generation of NO2- and NO3- decreased. | |

| gas sparging (air, O2, N2, Ar) | NO3-/NO2- = 0.37 | NO3-/NO2- = 0.39 | ||

| 0 | NO2-+NO3- : 0.35 μM/min | |||

| NO2-: 1.2 μM/20 min | 0 | |||

| NO3-: - | NO2-: 2.7 μM@60 min | |||

| NO3-: 0.71 μM@60 min | ||||

| NO3-/NO2- = 0.26 | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 0.06 μM/min | ||||

| 900 kHz | - air (5℃) | - For air, the generated amounts of NO2- and NO3- decreased significantly as the temperature increased from 5 to 40℃. | [13] | |

| Pcal = 27 W | NO2-: 68 μM@20 min | - For N2/O2 mixtures, the peak value of NO2- and NO3- was observed at N2:O2 (58:42). High or low ratios of O2 resulted in low generation of NO2- and NO3-. | ||

| VL = 100 mL (5℃) | NO3-: 35 μM@20 min | - NO2- and NO3- were not detected for O2 100% and N2 100%. | ||

| gas sparging (N2/O2 mixtures) | NO3-/NO2- = 0.51 | - pH@3 h = around 3.0 (air, 5℃) | ||

| NO2-+NO3- : 5.2 μM/min | ||||

| - air (40℃) | ||||

| NO2-: 18 μM@20 min | ||||

| NO3-: 15 μM@20 min | ||||

| NO3-/NO2- = 0.83 | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 1.7 μM/min | ||||

| #NULL! | ||||

| NO2-: 1.9 μM@20 min | ||||

| NO3-: 1.3 μM@20 min | ||||

| NO3-/NO2- = 0.68 | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 0.16 μM/min | ||||

| #NULL! | ||||

| NO2-: 61 μM@20 min | ||||

| NO3-: 95 μM@20 min | ||||

| NO3-/NO2- = 1.56 | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 7.8 μM/min | ||||

| #NULL! | ||||

| NO2-: 1.6 μM@20 min | ||||

| NO3-: 1.2 μM@20 min | ||||

| NO3-/NO2- = 0.75 | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 0.14 μM/min | ||||

| 500 kHz | NO2-: 140 μM/50 min | NO2-: 30 μM@275 min | - NO2- concentration decreased after the peak at 100 min and the generation rate for NO3- increased after 70 min. | [7] |

| Pcal = 30 W | NO3-: 60 μM/50 min | NO3-: 1,400 μM@275 min | - NO2- + NO3- concentration increased linearly during the entire US irradiation duration (275 min). | |

| VL = 200 mL | NO3-/NO2- = 0.43 | NO3-/NO2- = 46.7 | ||

| air saturated | NO2-+NO3- : 5.2 μM/min | |||

| 500 kHz | from 40 min to 120 min | NO2-: 14.4 μM@240 min | - During the degradation of chlorobenzene, NO2- and NO3- generation was monitored. | [19] |

| Pcal = 25 W | NO2-: 48.4 μM/80 min | NO3-: 223.9 μM@240 min | - After the removal efficiency of chlorobenzene reached 70% at 40 min, NO2- and NO3- generation started, because the availability of oxidizing radicals for NO2- and NO3- generation was limited due to the high volatility of chlorobenzene. | |

| VL = 250 mL | NO3-: 60.8 μM/80 min | NO3-/NO2- = 15.5 | - The peak for NO2- was observed at 120 min and then NO2- concentration decreased and NO3- generation rate increased. | |

| air saturated | NO3-/NO2- = 1.26 | NO2-+NO3- : 0.99 μM/min | ||

| chlorobenzene degradation | ||||

| 32.6 kHz | NO2-: 0.0004 μM/min | NO2-: 0.73 μM@30 h | - A single bubble cavitation system was investigated. | [18] |

| VL = 60 mL | NO3-: 0.0004 μM/min | NO3-: 0.76 μM@30 h | - NO2- and NO3- concentrations increased linearly during 30 h of US irradiation. | |

| single bubble system | NO3-/NO2- = 1 | NO3-/NO2- = 1.04 | ||

| air (DO : 3-6 mg/L) | NO2-+NO3- : 0.00083 μM/min | |||

| 118, 224, 404, 651 kHz | - | - 118 kHz | - No significant concentration of NO2- was observed, possibly due to long irradiation duration (10 h) and much larger generation of NO3- compared to that of NO2-. | [9] |

| Pcal = 29 W | NO2-: not detected | - NO3- concentration was linearly generated from 2 h for 118 kHz and from 0.5 h for 224, 404, and 651 kHz. | ||

| VL = 250 mL | NO3-: 47.2 mg/L@10 h | - The final concentration of NO3- for 11.4, 29.0, and 41.5 W was 746, 2,222, and 4,127 μM@10 h, respectively. | ||

| air saturated | (762 μM@10 h) | - pH@10 h = 2.5 – 3.5 for all cases | ||

| NO2-+NO3- : 1.3 μM/min | ||||

| - 224, 404, 651 kHz | ||||

| NO2-: not detected | ||||

| NO3-: 137.8 mg/L@10 h | ||||

| (2,222 μM@10 h) | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 3.7 μM/min | ||||

| 20 kHz (Probe) | NO2-: 50 μM/10 min | NO2-: 31 μM@60 min | - The mixture of NO (1,040 ppmv) and SO2 (2,520 ppmv) was used. | [17] |

| I = 86.8 W/cm2 | NO3-: 11 μM/60 min | NO3-: 11 μM@60 min | - The peak of NO2- (54 μM) was observed at 20 min at which point NO concentration decreased. | |

| VL = 1,200 mL | NO3-/NO2- = 0.04 | NO3-/NO2- = 0.35 | - NO3- increased linearly during the whole irradiation duration. | |

| gas sparging (NO 1,040 ppmv) | NO2-+NO3- : 0.7 μM/min | |||

| 300 kHz | NO2-: 180 μM/45 min | NO2-: 240 μM@180 min | - NO2- concentration decreased after the peak at 90 min and NO3- was generated linearly during the whole irradiation duration (180 min). | [6] |

| Pelec = 80 W | NO3-: 180 μM/45 min | NO3-: 760 μM@180 min | - pH: 6.6 → 3.0 (after 180 min) | |

| VL = 300 mL | NO3-/NO2- = 1.0 | NO3-/NO2- = 3.17 | ||

| air sparging | NO2-+NO3- : 5.6 μM/min | |||

| 404 kHz | - | - NO3- (only water) | - No significant concentration of NO2- was observed. | [8] |

| 3.5, 9.0, 12.9 kW/m2 | 3.5 kW/m2: 700 μM@10 h | - NO3- generation was delayed in the presence of BPA compared to in the absence of BPA. | ||

| VL = 250 mL | NO2-+NO3- : 1.2 μM/min | - pH@10 h = around 3.0 for all cases | ||

| air saturated | 9.0 kW/m2: 2,000 μM@10 h | |||

| NO2-+NO3- : 3.3 μM/min | ||||

| 12.9 kW/m2: 4,100 μM@10 h | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 6.8 μM/min | ||||

| - NO3- (with BPA degradation) | ||||

| 3.5 kW/m2: 200 μM@10 h | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 0.3 μM/min | ||||

| 9.0 kW/m2: 1,100 μM@10 h | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 1.8 μM/min | ||||

| 12.9 kW/m2: 2,800 μM@10 h | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 4.7 μM/min | ||||

| Reactor 1 | - Reactor 1 (Pcal = 19.1 W) | - The US irradiation time ranged from 15 to 150 min depending on experimental conditions. | [16] | |

| 365 kHz | NO2-: 1.15 μM/min | - The larger volume of the second reactor resulted in approximately 10 times lower generation of NO2- and NO3- under the similar power condition (19.1 W and 21.6 W). | ||

| VL = 0.4 L (D = 65 mm) | NO3-: 0.2 μM/min | - As the input power increased, the generation of NO2- and NO3- increased. | ||

| Pcal = 19.1 W | NO3-/NO2- = 0.17 | |||

| NO2-+NO3- : 1.35 μM/min | ||||

| Reactor 2 | - Reactor 2 (Pcal = 8.4 W) | |||

| 367 kHz | NO2-: 0.032 μM/min | |||

| VL = 2.0 L (D = 102 mm) | NO3-: 0.005 μM/min | |||

| Pcal = 8.4, 13.6, 21.6, 27.8 W | NO3-/NO2- = 0.16 | |||

| NO2-+NO3- : 0.04 μM/min | ||||

| - Reactor 2 (Pcal = 13.6 W) | ||||

| NO2-: 0.07 μM/min | ||||

| NO3-: 0.007 μM/min | ||||

| NO3-/NO2- = 0.10 | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 0.08 μM/min | ||||

| - Reactor 2 (Pcal = 21.6 W) | ||||

| NO2-: 0.11 μM/min | ||||

| NO3-: 0.022 μM/min | ||||

| NO3-/NO2- = 0.20 | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 0.13 μM/min | ||||

| - Reactor 2 (Pcal = 27.8 W) | ||||

| NO2-: 0.18 μM/min | ||||

| NO3-: 0.047 μM/min | ||||

| NO3-/NO2- = 0.26 | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 0.23 μM/min | ||||

| 800 kHz | - US | - US | - NO2- and NO3- concentrations increased linearly in the US process. | [21] |

| Pcal = 25 W | NO2-: 41.9 μM/40 min | NO2-: 41.9 μM@40 min | - In the US/UV process, the generation rate for NO2- decreased gradually and significantly, and the generation rate for NO3- increased after 10 min. | |

| VL = 250 mL | NO3-: 45.6 μM/40 min | NO3-: 45.6 μM@40 min | - NO2- + NO3- increased linearly during the whole irradiation period and similar final concentrations of NO2- + NO3- were obtained for both US and US/UV processes. | |

| US and US/UV system | NO3-/NO2- = 1.09 | NO3-/NO2- = 1.09 | ||

| - US/UV | NO2-+NO3- : 2.2 μM/min | |||

| NO2-: 8.0 μM/10min | - US/UV | |||

| NO3-: 14.8 μM/10 min | NO2-: 17.8 μM@40 min | |||

| NO3-/NO2- = 1.85 | NO3-: 75.3 μM@40 min | |||

| NO3-/NO2- = 4.23 | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 2.3 μM/min | ||||

| 200, 400, 600, 800 kHz | - 200 kHz | - 200 kHz | - For 200, 400, and 600 kHz, NO2- and NO3- concentrations increased linearly during the first 20 min and then the rates of NO2- and NO3- generation changed gradually and significantly. | [2] |

| I = 0.69 W/cm2, 0.19 W/mL | NO2-: 70 μM/20 min | NO2-: 170 μM@60 min | - NO2- and NO3- concentrations increased relatively linearly during the whole irradiation duration (60 min) for 800 kHz, possibly due to lower concentrations of NO2- and NO3-. | |

| VL = 200 mL | NO3-: 44 μM/20 min | NO3-: 200 μM@60 min | - For N2:O2 (75:25), N2:O2 (50:50), and N2:O2 (25:75), NO2- decreased and the generation rate of NO3- increased gradually after the peak at 40-60 min. | |

| air sparging | NO3-/NO2- = 0.63 | NO3-/NO2- = 1.18 | - NO2- and NO3- generation: N2:O2 (75:25) > N2:O2 (50:50) > N2:O2 (25:75) >> N2 100%, O2 100% ≈ 0 | |

| - 400 kHz | NO2-+NO3- : 6.2 μM/min | |||

| NO2-: 40 μM/20 min | - 400 kHz | |||

| NO3-: 20 μM/20 min | NO2-: 120 μM@60 min | |||

| NO3-/NO2- = 0.50 | NO3-: 110 μM@60 min | |||

| - 600 kHz | NO3-/NO2- = 0.92 | |||

| NO2-: 110 μM/20 min | NO2-+NO3- : 3.8 μM/min | |||

| NO3-: 24 μM/20 min | - 600 kHz | |||

| NO3-/NO2- = 0.22 | NO2-: 170 μM@60 min | |||

| - 800 kHz | NO3-: 280 μM@60 min | |||

| NO2-: 28 μM/20 min | NO3-/NO2- = 1.65 | |||

| NO3-: 7 μM/20 min | NO2-+NO3- : 7.5 μM/min | |||

| NO3-/NO2- = 0.25 | - 800 kHz | |||

| NO2-: 73 μM@60 min | ||||

| NO3-: 27 μM@60 min | ||||

| NO3-/NO2- = 0.37 | ||||

| NO2-+NO3- : 1.7 μM/min | ||||

| 28 kHz | air | - air | - For the air saturated condition, the linear generation rate for NO2- and NO3- decreased significantly after 30 min. | [20] |

| Pelec = 1,200 W (US bath) | NO2-: 40 μM/30 min | NO2-: 72.3 μM@120 min | - A very low concentration of NO3- was observed for N2 100%, O2 100% and Ar 100%. | |

| VL = 200 mL | NO3-: 42 μM/30 min | NO3-: 52.8 μM@120 min | - pH: 6.3 → 5.4 (after 120 min) | |

| vessel submerged in US bath | NO3-/NO2- = 1.05 | NO3-/NO2- = 0.73 | ||

| gas saturated (air, O2, N2, Ar) | NO2-+NO3- : 1.0 μM/min | |||

| 0 | ||||

| NO3-: 4 μM@120 min | ||||

| 0 | ||||

| NO3-: 2 μM@120 min | ||||

| - Ar | ||||

| NO3-: 0 μM@120 min | ||||

| 200 kHz | NO2-: 100 μM/30 min | NO2-: 160 μM@60 min | - NO2- decreased (119 μM@180 min) and NO3- increased (157 μM@180 min) after US irradiation stopped at 60 min. NO2-+NO3- remained constant after US irradiation stopped. | [1] |

| Pcal = 25 W | NO3-: 40 μM/30 min | NO3-: 110 μM@60 min | - The highest NO2-+NO3- was obtained at 14 W among 2.7, 5.5, 14, 19, and 25 W | |

| VL = 65 mL | NO3-/NO2- = 0.40 | NO3-/NO2- = 0.69 | ||

| vessel submerged in US bath | NO2-+NO3- : 4.5 μM/min | |||

| air saturated | ||||

| 28 kHz | - gas saturated/closed | - The generation of H2O2 under various gas conditions was investigated in Part I of this work. | in this study | |

| Pcal = 55 W | (12 gas conditions) | - Three gas supply modes including saturated/closed, saturated/open, and sparging/closed were investigated. | ||

| VL = 3.65 L | NO2-: 0.08–3.58 μM@90 min | - NO2- and NO3- increased linearly during whole US irradiation duration (90 min). | ||

| gas saturated/gas sparging | NO3-: 0.11–1.86 μM@90 min | - The highest concentration of NO2- and NO3- was obtained for N2:Ar (25:75) for the three gas modes. | ||

| (Ar, O2, N2, and binary mixtures) | NO3-/NO2-: 0.34–1.71 | - H2O2/NO2-/NO3- related OH radical activity was suggested to consider more appropriate sonochemical oxidation activity. | ||

| NO2-+NO3-: 0.002–0.06 μM/min | ||||

| - gas saturated/open | ||||

| (7 gas conditions) | ||||

| NO2-: 0.74–6.56 μM@90 min | ||||

| NO3-: 0.61–3.20 μM@90 min | ||||

| NO3-/NO2-: 0.41–0.82 | ||||

| NO2-+NO3-: 0.015–0.10 μM/min | ||||

| - gas sparging/closed | ||||

| (6 gas conditions) | ||||

| NO2-: 0–8.23 μM@90 min | ||||

| NO3-: 0.10–4.60 μM@90 min | ||||

| NO3-/NO2-: 0.56–2.85 | ||||

| NO2-+NO3-: 0.001–0.14 μM/min | ||||

For the saturation/closed mode, lower concentrations of NO2− and NO3− were obtained for the gas conditions where higher concentrations of H2O2 were obtained, and higher amounts of NO2− and NO3− were generated for the conditions where lower amounts of H2O2 were detected. The generation of NO2− and NO3− was principally attributed to the presence of N2, an essential ingredient for the generation of nitrogen oxides, in the following order: N2:Ar (25:75) > N2:Ar (50:50) > O2:N2 (25:75) > O2:N2 (50:50) > N2:Ar (75:25) > O2:N2 (75:25). The large generation of NO2− and NO3− may have been attributed to two factors: 1) a higher ratio of Ar leading to more severe and violent cavitation events that result in increased generation of NO, the precursor of NO2− and NO3−, and highly reactive oxidizing radicals [5], [24], [25], [26]; and 2) the presence of O2 effectively promoting the generation of oxidizing radicals such as OH radicals [24], [27], [28]. From the above-mentioned order, Ar was found to be the most important for the generation of NO2− and NO3−, followed by O2 in the presence of N2. In addition, a higher ratio of Ar and a relatively lower ratio of O2 were favorable for NO2− and NO3− generation in this study. Therefore, it is conceivable that very small amounts of NO2− and NO3− were produced in N2 100 % as shown in this study. As shown in Table 2, previous researchers have also reported similar findings under various gas mixture conditions: Hart et al. reported that the highest generation rate of NO2− + NO3− was obtained at Ar:N2 (40–60:60–40) and less than 30 % of the highest rate was obtained at N2 100 % for Ar/N2 mixtures under 300 kHz [3]; Mišík and Riesz found the highest level of NO, the precursor of NO2− and NO3−, at N2:O2 (90–78:10–22) for N2/O2 mixtures and at N2:Ar (29–57:71–43) for N2/Ar mixtures under 50 kHz. No NO was generated at O2 100 % and Ar 100 % in their study [5]; in Supeno and Kruus’s study, the highest concentrations of NO2− and NO3− were detected at N2:O2 (58:42), and no NO2− and NO3− were generated at O2 100 % and N2 100 % under 900 kHz [13]; Yao et al.’s highest concentrations of NO2− and NO3− were obtained at N2:O2 (75:25), and no NO2− and NO3− were generated at O2 100 % and N2 100 % under 600 kHz [2].

In principle, NO2− and NO3− could not be generated for the conditions from Ar 100 % to O2 100 % [Fig. 1(a)] because of the absence of N2. However, low concentrations of NO2− and NO3− were detected due to the residual trace of N2, which was not removed by the 20-min sparging for gas saturation that occurred before ultrasonic irradiation [12]. Only very low concentrations of NO2− and NO3− were generated for the gas sparging conditions of Ar 100 %, Ar:O2 (75:25), and O2 100 %, as shown in Fig. 3(b), because the residual N2 was continuously and more completely removed by the gas sparging during ultrasonic irradiation.

Fig. 3.

Sonochemically generated concentration of NO2−, NO3−. NO2− + NO3− and H2O2 under the saturation/open and the sparging/closed mode using Ar, O2, and N2 for 28 kHz. The irradiation duration was 90 min. The yellow bar in Fig. 3(a) represents the value obtained for NO2− and NO3− under the saturation/closed mode as shown in Fig. 1. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The ratio of NO3− to NO2− may also provide information on the sonochemical oxidizing activity. As shown in Fig. 1S, the ratio using the concentration of NO2− and NO3− in the first linear generation period ranged from 0.34 [O2:N2 (25:75)] to 1.71 [Ar:O2 (25:75)] for the saturation/closed conditions. Despite low concentrations of NO2− and NO3−, the ratio was higher than 1 for the conditions from Ar:O2 (75:25) to O2 100 %, where higher oxidizing activity was obtained. This indicates that sonochemically generated NO2− can be easily oxidized to NO3− in the presence of many oxidizing agents, such as ∙OH, O2, and H2O2 [1], [2]. This might be also due to the low concentration of NO2− compared to the generated oxidizing radicals, considering the concentration of generated H2O2 in the conditions from Ar:O2 (75:25) to O2 100 %. In previous studies, various ratios have been reported depending on the experimental conditions and irradiation times. It was found that the NO2− and NO3− concentrations increased linearly during the initial stage. After the NO2− concentration peaked, it decreased significantly, and correspondingly, NO3− increased with higher generation rates. The decrease in NO2− concentration is mainly attributed to the oxidation of NO2− to NO3− using sonochemically generated oxidizing species [1], [2].

As shown in Table 2, the ratio using NO2− and NO3− concentrations (NO3−/NO2−) in the linear generation period was less than 1.1 before 60 min had passed: 0.37 (30 min, NO2−+NO3−: 0.36 μM/min, air, 35 kHz) [14]; 0.43 (50 min, NO2−+NO3−: 40 μM/min, air, 500 kHz) [7]; 1.0 (45 min, NO2−+NO3−: 8 μM/min, air, 300 kHz) [6]; 1.09 (40 min, NO2−+NO3−: 2.19 μM/min, air, 800 kHz); 0.63 (20 min, NO2−+NO3−: 5.7 μM/min, air, 200 kHz), 0.50 (20 min, NO2−+NO3−: 3.0 μM/min, air, 400 kHz), 0.22 (20 min, NO2−+NO3−: 6.7 μM/min, air, 600 kHz), and 0.25 (20 min, NO2−+NO3−: 1.75 μM/min, air, 800 kHz) [2]. The gaseous state of air leads to relatively low oxidizing activity, causing the ratio to be lower than 1.1. Jiang et al. reported a slightly higher ratio of 1.26 (80 min, NO2−+NO3−:1.37 μM/min, air, 500 kHz), which was obtained during the degradation of a volatile compound (chlorobenzene) which significantly inhibited the oxidizing radical activity of chemical species existing outside the cavitation bubbles. In their research, NO2− and NO3− were not detected during the first 40 min, and it was highly likely that a substantial amount of NO, the precursor of NO2− and NO3−, was not generated during this period [19]. In this study, the ratio for O2:N2 (25:75), a composition similar to air, was 0.34. Ratios higher than 1.1 were obtained for Ar:O2 (75:25), Ar:O2 (50:50), Ar:O2 (25:75), and O2 100 %.

Final concentrations of NO2− and NO3− were also reported in previous research, with ratios of NO3− to NO2− ranging from 0.26 to 46.7 as shown in Table 2. A ratio much higher than 1 indicates that the concentrations of the ratio were collected over a longer period of time after the first linear generation period, allowing a large amount of NO2− to be further oxidized to NO3−. Inoue et al. also reported no significant concentration of NO2− and a high concentration of NO3− after 10 h [8], [9]. Thus, the sum of NO2− and NO3− is more appropriate for understanding the sonochemical generation characteristics of NO2− and NO3−. Pétrier and Casadonte [7] and Zaviska et al. [21] reported that the NO2− + NO3− concentration increased linearly over the entire duration of irradiation. Zaviska et al. also found that the final concentrations of NO2− + NO3− were highly similar for the US and US/UV processes [21]. Okitsu and Itano found that the NO2− + NO3− concentration remained constant after US irradiation stopped, even though NO2− decreased and NO3− increased [1].

As shown in Table 2, various values of NO2− + NO3− generation rate ranging from 0.04 μM/min to 162 μM/min were obtained using the final concentrations of NO2− and NO3− depending on the applied frequency, the input power, the gas mixture, and the liquid volume: 162 μM/min [300 kHz, 20 mL, Ar:N2O (96:4)] [15]; 1.6–5.9 μM/min (300 kHz, 37.5 mL, Ar/N2 mixtures) [3]; 0.35 μM/min for air, 0.06 μM/min for N2 (35 kHz, 650 mL) [14]; 1.7–5.2 μM/min for air, 0.14–7.8 μM/min for N2/O2 mixtures (900 kHz, 100 mL) [13]; 5.2 μM/min (500 kHz, 200 mL, air) [7]; 0.99 μM/min (500 kHz, 250 mL, air, chlorobenzene degradation) [19]; 1.3–3.7 μM/min for 118, 224, 404, 651 kHz (250 mL, air) [9]; 5.6 μM/min (300 kHz, 300 mL, air) [6]; 1.2–6.8 μM/min for only water, 0.3–4.7 μM/min for BPA degradation (404 kHz, 250 mL, air) [8]; 1.35 μM/min (365 kHz, 0.4 L), 0.04–0.23 μM/min (367 kHz, 2.0 L) [16]; 2.2 μM/min for US, 2.3 μM/min for US/UV (800 kHz, 250 mL) [21]; 1.7–7.5 μM/min (200–800 kHz, 200 mL, air) [2]; 1.0 μM/min (28 kHz, 200 mL, air) [20]; 4.5 μM/min (200 kHz, 65 mL of air) [1]. From the results of previous research, it seemed that a higher frequency and lower liquid volume resulted in a higher concentration of NO2− and NO3−. However, further research is needed because the results in Table 2 were obtained under very different experimental conditions. As shown in Fig. 1, relatively low concentrations of NO2− + NO3− ranging from 0.002 μM/min [O2 100 %] to 0.06 μM/min [N2:Ar (25:75)] were observed in this study. This may be due to the low frequency (28 kHz) and higher liquid volume (3.65 L) used in this study.

3.2. Effect of OH radical scavenger

As shown in Fig. 2, it is clearly understood that the generation of H2O2, NO2−, and NO3− is greatly related to the OH radical activity. In the presence of tert-butyl alcohol (TBA) (40 mM), which is one of the most common OH radical scavengers [29], [30], the concentrations of H2O2, NO2−, and NO3− decreased significantly for Ar:O2 (75:25), where the highest H2O2 generation was observed, and N2:Ar (25:75), where the highest NO2− and NO3− generation was detected in this study. The presence of TBA more severely affected the sonochemical oxidation reactions for N2:Ar (25:75) and it might be due to the lower availability of oxidizing radicals for N2:Ar (25:75) than for Ar:O2 (75:25).

Fig. 2.

Effect of the radical scavenger (tert-butyl alcohol, 40 mM) on the generation of H2O2, NO2−, NO3− for Ar:O2 (75:25) and N2:Ar (25:75), with an irradiation duration of 90 min.

Considering the generation of NO2− and NO3− and their relationship with OH radicals, the sonochemical oxidation activity can be better understood. Under the simple assumption that two, one, and two OH radicals are consumed for the generation of H2O2, NO2−, and NO3−, respectively, a more realistic OH radical activity can be calculated and compared for various gas conditions, as shown in Fig. 2S. No significant difference (only 1.7–7.0 %) was observed between two activities, including H2O2/NO2−/NO3− related activity (H2O2 concentration × 2 + NO2− concentration × 1 + NO3− concentration × 2) and H2O2 related activity (H2O2 concentration × 2) for the gas conditions from Ar 100 % to O2 100 %. However, a relatively large difference (30.5–49.7 %) was obtained from O2:N2 (50:50) to N2:Ar (25:75) indicating that actual OH radical activity could be further underestimated by a third to a half for the gas conditions. It should be noted that this assumption is debatable because the radical reactions for the sonochemical generation of H2O2, NO2−, and NO3− cannot be precisely identified under various ultrasonic conditions. In addition, the reactivity of OH radicals and the generation locations during cavitation events can be significantly different for H2O2, NO2−, and NO3−.

3.3. Saturation/open and sparging/closed mode

The generation of H2O2, NO2−, and NO3− under saturation/open and sparging/closed modes was investigated, as shown in Fig. 3. As discussed in Part I of this study, no significant difference was observed between the sparging/closed and sparging/open modes. For the saturation/open mode, the concentrations of NO2− and NO3− increased significantly for all applied gas conditions compared to those obtained for the saturation/closed mode because of the gas exchange between the liquid and air phases. The order for the NO2− + NO3− concentration was as follows: N2:Ar (25:75) ≈ Ar:O2 (75:25) > Ar 100 % > Ar:O2 (25:75) ≈ O2:N2 (75:25) ≈ N2 100 % > O2 100 %. The large increase in the NO2− + NO3− concentration for Ar 100 % (556 %), Ar/O2 mixtures (722 %, 975 %) and O2 100 % (685 %) was attributed to the entry of N2 into the liquid phase, the essential source of NO2− and NO3−, considering the change in the DO concentration, as shown in Table 1. Relatively lower increases for N2 100 % (312 %) and N2:Ar (25:75) (170 %) were observed, which might be due to relatively lower oxidation activity. However, it was again confirmed that the presence of O2 significantly enhanced the generation of NO2− and NO3−. In addition, the ratio of NO3− to NO2− was less than 1 for all applied gas conditions. The ratio of Ar:O2 (75:25), Ar:O2 (25:75), and O2 100 % was higher than 1 under the saturation/closed mode, as shown in Fig. 1S due to relatively high oxidation activity considering the H2O2 concentration for the saturation/open and the saturation/closed modes. This indicated that the sonochemical oxidation activity decreased owing to the entry of N2, which resulted in the reduction of the Ar and O2 contents in the liquid phase.

In previous studies, the gas sparging method was frequently used to maintain the gas content to investigate the effect of dissolved gases on sonochemical reactions [2], [5], [6], [13], [14], [17]. However, comparisons between gas saturation and gas sparging have rarely been reported. In the sparging/closed mode, large enhancement in the generation of NO2− and NO3− was observed for O2:N2 (25:75) (315 %), N2 100 % (290 %), and N2:Ar (25:75) (236 %) compared to that obtained in the saturation/closed mode. This enhancement was due to the sparging effect, which induced a change in the sonochemical active zone in terms of the location, shape, and intensity, as well as violent mixing in the liquid phase, as discussed in Part I of this work. The effect of the residual trace gases could be negligible because no significant concentrations of NO2− and NO3− were detected for Ar 100 %, Ar:O2 (75:25), and O2 100 %. It was found that the main source of oxygen atoms for the generation of NO2− and NO3− was the water molecules for N2 100 % and N2:Ar (25:75) [5]. In addition, gas sparging was more effective for the generation of H2O2. The enhancement by the gas sparging for the applied six gas conditions ranged from 248 to 729 % and 18–315 % for the generation of H2O2 and NO2− + NO3−, respectively. The highest H2O2/NO2−/NO3− related activity was obtained for Ar:O2 (75:25), with activity-three times higher than that of the saturation/closed mode.

4. Conclusion

The effects of gas saturation and sparging on the sonochemical generation of NO2− and NO3− were investigated using a 28 kHz sonoreactor equipped with a gas supply system as Part II of the study. Twelve gas conditions including Ar 100 %, O2 100 %, N2 100 %, and binary gas mixtures, were applied under three gas modes: saturation/closed, saturation/open, and sparging/closed. The conclusions of this study are as follows:

-

1.

In the saturation/closed mode, the highest NO2− and NO3− concentrations were obtained for N2:Ar (25:75), N2:Ar(50:50), and O2:N2 (25:75), which was attributed to the presence of Ar and O2. The generation of NO2− and NO3− for the Ar 100 %, Ar/O2 mixtures and O2 100 % was due to the residual N2.

-

2.

Gas exchange between the liquid and air occurred in the saturation/open mode. Relatively higher concentrations of NO2− and NO3− were observed for the seven gas conditions due to the entry of N2 and O2 compared to that for the saturation/closed mode.

-

3.

Gas sparging enhanced the generation of NO2− and NO3− for O2:N2 (25:75) and N2:Ar (25:75) significantly. However, no significant concentrations of NO2− and NO3− were obtained for Ar 100 %, Ar:O2 (75:25), and O2 100 % due to the continuous removal of residual N2.

-

4.

Results and findings regarding sonochemical generation of NO2− and NO3− were summarized and compared with the results in this study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Younggyu Son: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Jongbok Choi: Methodology, Investigation, Validation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea [NRF-2021R1A2C1005470] and by the Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE) as “Subsurface Environment Management (SEM)” Program [project No. 2021002470001].

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106250.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Okitsu K., Itano Y. Formation of NO2− and NO3− in the sonolysis of water: Temperature- and pressure-dependent reactions in collapsing air bubbles. Chem. Eng. J. 2022;427 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao J., Chen L., Chen X., Zhou L., Liu W., Zhang Z. Formation of inorganic nitrogenous byproducts in aqueous solution under ultrasound irradiation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;42:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hart E.J., Fischer C.H., Henglein A. Isotopic exchange in the sonolysis of aqueous solutions containing nitrogen-14 and nitrogen-15 molecules. J. Phys. Chem. 1986;90:5989–5991. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Supeno, Kruus P. Fixation of nitrogen with cavitation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2002;9:53–59. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4177(01)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mišík V., Riesz P. Nitric oxide formation by ultrasound in aqueous solutions. J. Phys. Chem. 1996;100:17986–17994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres R.A., Pétrier C., Combet E., Moulet F., Pulgarin C. Bisphenol A mineralization by integrated ultrasound-UV-iron (II) treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41:297–302. doi: 10.1021/es061440e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pétrier C., Casadonte D. The sonochemical degradation of aromatic and chloroaromatic contaminants. Adv. Sonochem. 2001;6:91–109. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoue M., Masuda Y., Okada F., Sakurai A., Takahashi I., Sakakibara M. Degradation of bisphenol A using sonochemical reactions. Water Res. 2008;42:1379–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inoue M., Okada F., Sakurai A., Sakakibara M. A new development of dyestuffs degradation system using ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2006;13:313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Kerabchi N. In: Water Engineering Modeling and Mathematic Tools. Samui P., Bonakdari H., Deo R., editors. Elsevier; 2021. 22 - On the sonochemical production of nitrite and nitrate in water: A computational study; pp. 429–452. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jablonowski H., Schmidt-Bleker A., Weltmann K.-D., von Woedtke T., Wende K. Non-touching plasma–liquid interaction – where is aqueous nitric oxide generated? Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018;20:25387–25398. doi: 10.1039/c8cp02412j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mead E.L., Sutherland R.G., Verrall R.E. The effect of ultrasound on water in the presence of dissolved gases. Can. J. Chem. 1976;54:1114–1120. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Supeno, Kruus P. Sonochemical formation of nitrate and nitrite in water. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2000;7:109–113. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4177(99)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakeford C.A., Blackburn R., Lickiss P.D. Effect of ionic strength on the acoustic generation of nitrite, nitrate and hydrogen peroxide. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1999;6:141–148. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henglein A. Sonolysis of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane in aqueous solution. Z. Naturforsch. 1985;40b:100–107. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rochebrochard d'Auzay S.D.L., Blais J.F., Naffrechoux E. Comparison of characterization methods in high frequency sonochemical reactors of differing configurations. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2010;17:547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owusu S.O., Adewuyi Y.G. Sonochemical removal of nitric oxide from flue gases. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006;45:4475–4485. doi: 10.1021/jp0631634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koda S., Tanaka K., Sakamoto H., Matsuoka T., Nomura H. Sonochemical efficiency during single-bubble cavitation in water. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2004;108:11609–11612. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang Y., Pétrier C., David Waite T. Kinetics and mechanisms of ultrasonic degradation of volatile chlorinated aromatics in aqueous solutions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2002;9:317–323. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4177(02)00085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwedi-Nsah L.M., Kobayashi T. Sonochemical nitrogen fixation for the generation of NO2− and NO3− ions under high-powered ultrasound in aqueous medium. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;66 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaviska F., Drogui P., El Hachemi E.M., Naffrechoux E. Effect of nitrate ions on the efficiency of sonophotochemical phenol degradation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Son Y. Simple design strategy for bath-type high-frequency sonoreactors. Chem. Eng. J. 2017;328:654–664. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim M., Ashokkumar M., Son Y. The effects of liquid height/volume, initial concentration of reactant and acoustic power on sonochemical oxidation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21:1988–1993. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beckett M.A., Hua I. Impact of ultrasonic frequency on aqueous sonoluminescence and sonochemistry. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001;105:3796–3802. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rooze J., Rebrov E.V., Schouten J.C., Keurentjes J.T.F. Dissolved gas and ultrasonic cavitation – A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013;20:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merouani S., Ferkous H., Hamdaoui O., Rezgui Y., Guemini M. New interpretation of the effects of argon-saturating gas toward sonochemical reactions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;23:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer C.H., Hart E.J., Henglein A. Ultrasonic irradiation of water in the presence of oxygen 18,18O2: isotope exchange and isotopic distribution of hydrogen peroxide. J. Phys. Chem. 1986;90:1954–1956. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pflieger R., Chave T., Vite G., Jouve L., Nikitenko S.I. Effect of operational conditions on sonoluminescence and kinetics of H2O2 formation during the sonolysis of water in the presence of Ar/O2 gas mixture. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;26:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao Z., Zhang D., Jun Y.-S. Does tert-butyl alcohol really terminate the oxidative activity of •OH in inorganic redox chemistry? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021;55:10442–10450. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c01578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao R., Diaz-Rivera D., He Z., Weavers L.K. Using pulsed wave ultrasound to evaluate the suitability of hydroxyl radical scavengers in sonochemical systems. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013;20:990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.