Graphical abstract

Keywords: Papain-like cysteine protease, Cysteine cathepsin, Protease specificity, Binding site, Selective inhibitor, Protein engineering

Abstract

Papain-like cysteine proteases are widely expressed enzymes that mostly regulate protein turnover in the acidic conditions of lysosomes. However, in the last twenty years, these proteases have been evidenced to exert specific functions within different organelles as well as outside the cell. The most studied proteases of this family are human cysteine cathepsins involved both in physiological and pathological processes. The specificity of each protease to its substrates is mostly defined by the structure of the binding cleft. Different patterns of amino acid motif in this area determine the interaction between the protease and the ligands. Moreover, this specificity can be altered under the specific media conditions and in case other proteins are present. Understanding how this network works would allow researchers to design the diagnostic selective probes and therapeutic inhibitors. Moreover, this knowledge might serve as a key for redesigning and de novo engineering of the proteases for a wide range of applications.

1. Introduction

Proteases are proteins that cleave peptide bonds thus maintaining the protein catabolism and performing cell signaling. Based on the structure of their catalytic site, proteases are subdivided into eight classes: aspartic, cysteine, glutamic, serine, threonine, metallopeptidases, asparagine peptide lyases, and peptidases of mixed catalytic type [1]. Papain-like cysteine proteases (PLCPs) are one of the most thoroughly studied families (family C1, clan CA) among the cysteine peptidases. It comprises endo- and exopeptidases homologous to papain. PLCPs are expressed as preproenzymes and the expressed polypeptide chain consists of a signal peptide, a propeptide, and a catalytic domain. The signal peptide is necessary for transporting a protein into the endomembrane system, where it is cleaved by signal peptidases [2], [3]. The propeptide catalyzes folding of the catalytic domain and inhibits the protease catalytic activity [4], [5]. The protease is activated in the acidic environment of endosomes and lysosomes via eliminating the propeptide in an autocatalytic manner or by other proteases [3]. The activity of mature PLCPs is tightly regulated by the post-translational modifications and inhibitors such as cystatins and serpins [6], [7]. The genes encoding PLCPs have been identified in bacteria, archaea, protozoa, plants, animals, and viruses [1]. Although these proteases are mainly found in acidic conditions of the apoplast, they can also perform essential functions in the nucleus, cytosol, cell surface, and extracellular space [2], [8]. Despite mounting evidence gathered in the last decade the complexity and intricacies of this network are not fully elucidated.

In different organisms, PLCPs play specific roles contributing to processes ranging from cell differentiation to cellular senescence. In plants, PLCPs are involved in stress response, mobilization of storage proteins during seed germination, induction of defense reactions, senescence, and regulated cell death [6], [9], [10], [11]. Some aspects of PLCP regulation and application are better investigated on plant PLCPs, so we will discuss them below. In parasites, PLCPs contribute to the regulated cell death, host immune response modulation, hydrolysis of ingested host macromolecules, and progression disease [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. The most studied animal PLCPs are human cysteine cathepsins which are ubiquitously expressed being essential for antigen processing, cellular stress signaling, autophagy, senescence, cells differentiation, and prohormones activation [2], [17], [18], [19]. Apart from their usual roles under normal physiological conditions, human cathepsins are also involved in tumor growth, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis [20], [21]. In the present review we will focus our attention on structural features of mammalian cysteine cathepsins.

Cysteine cathepsins were reported to play a certain role in muscular dystrophy, rheumatoid arthritis, bone disorders, and Alzheimer's disease [22]. In particular, cathepsin K (CtsK) is excessively expressed in osteoclasts and is responsible for bone turnover [23]. Its elevated activity leads to osteoporosis and arthritis, while its deficiency is associated with learning and memory deficits [24], [25]. The excess activity of CtsC promotes various inflammatory diseases, while its down-regulation results in autoimmune disorders [26], [27]. CtsL is involved in cell differentiation and proliferation playing an important role in skin homeostasis and antigen presentation [28], [29], [30]. CtsL and K contribute to adipogenesis and liberation of thyroid hormones [31], [32]. Their activity in the extracellular space facilitates cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases and cancer [33]. Intracellular CtsB has been shown to inhibit cancer via promoting apoptosis, while along with CtsL, it can protect the cells against anticancer chemotherapies [34], [35]. CtsL, S, F, and V degrade the invariant chain (li) during the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II antigen presentation [36]. Since the excessive activity of human cysteine cathepsins is tightly linked to multiple disorders and tumor progression in particular, they represent promising molecular targets for developing novel therapeutic avenues [37].

Presently, drug design is determined by the structure of the ultimate target. All PLCPs belong to one peptidase family sharing a similar structure [1]. However, their remarkable functional diversity may require a set of rather selective inhibitors to be harnessed. In this review, we delve into the structural peculiarities determining the specific roles of PLCPs or allowing for their interchange ability. We also overview how these specificities can be employed for designing selective inhibitors and engineering new proteases.

2. Proteolytic activity of PLCPs

2.1. Substrates and endogenic inhibitors of PLCPs

PLCPs perform multiple functions since they can digest different substrates and often substitute each other. For instance, human cysteine cathepsins digest the extracellular matrix made up of elastins, collagens, and proteoglycans [38]. Some of them are listed in Table 1, but the complete information on discovered PLCP substrates can be received in MEROPS Database [1]. Elastin is mainly cleaved by CtsV, K, S, F, L, and B [39], [40], CtsB degrades type IV collagen, laminin, and fibronectin [41], CtsL and CtsS can release glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) such as aggrecan from cartilage proteins [42], while CtsK and CtsL participate in bone resorption [43]. Even CtsC lacking the exclusion domain (endopeptidase CtsCΔEx) can cleave azocasein, elastin, and gelatin [44]. The other substrates degraded by cysteine cathepsins are thyroglobulins, and each cathepsin generates distinct fragments [45]. The truncated active form of pro-apoptotic Bid and the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, and XIAP) can be cleaved by CtsB, K, L, and H, whereas CtsS is involved in degrading pro-apoptotic Bax [46], [47]. Cathepsins are also involved in generating peptides which are presented to MHC class-II molecules. Experiments in mice identified CtsL and S as the key enzymes in the final steps of li degradation. However, CtsF has been reported to compensate their loss in macrophages [48], [49], [50]. Still, some substrates are sensitive only to one protease; for instance, native type I collagen can be digested only by CtsK [51], [52]. CtsL was shown to cleave histone H3 in the nucleus [28], [53] and to take part in the processing of the coronavirus [54], [55]. CtsX was found to cleave β2 integrin, thus regulating T-cell migration [2], [56].

Table 1.

Some of the human cysteine cathepsin endogenous substrates. O – hydroxyproline. Further information on PLCP substrates can be found in MEROPS Database [1].

| Substrates | Cathepsins | Cleavage site P4P3P2P1↓P1′P2′P3′P4′ |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elastin | CtsS | PGVG↓GLGV | [57] |

| Collagen type I | CtsK | EGPN↓GVRG -GPM↓GPSG MGPS↓GPRG SGPR↓GLOG GPOG↓AOGP OGPN↓GFNG GLPG↓FKGI DFSF↓LPNP NPPN↓EKAH GLPG↓MKGH AGAR↓GSDG |

[58], [59], [60] |

| CtsL | GPRG↓LOGP GPOG↓AOGP NGFN↓GPOG |

[59] | |

| CtsS | GPAG↓APGD | [57] | |

| Collagen type II | CtsK | GKPG↓KSGE | [58] |

| Collagen type III | CtsB | -NGE↓TGPN | [61] |

| Collagen type VIII | CtsB | TIPG↓KPGA | [61] |

| Collagen type XI | CtsS | PGML↓VEGP | [57] |

| Collagen type XVIII | CtsL | LSLA↓HTHN | [62] |

| Proteoglycan 4 | CtsS | LRPH↓VFMP PHVF↓MPEV HYFW↓MLSP FKRG↓GSIN GRRP↓ALNY YYAF↓SKDQ |

[63] |

| Aggrecan core protein | CtsB | NFFG↓VGGE | [64] |

| Casein kinase II | CtsL | EPFF↓HGHD EPFF↓HGND FNLT↓GLNE |

[61] |

| Thyroglobulin | CtsB | REAA↓SGNF PTVG↓SFGF EVDL↓LIGS |

[65] |

| CtsL | NLFR↓RAVL KLLA↓VSGP LLIG↓SSND EFSR↓KVPT |

||

| Bid | CtsB | SRSF↓NQGR QASR↓SFNQ ASRS↓FNQG |

[47] |

| CtsH | NQGR↓IEPD SGLG↓AEHI VQAY↓WEAD SEVS↓NGSG |

||

| CtsK | SGLG↓AEHI QASR↓SFNQ |

||

| CtsL | QASR↓SFNQ | ||

| CtsS | QASR↓SFNQ SGLG↓AEHI VQAY↓WEAD DELQ↓TDGS |

To reveal the distinct specificities of cysteine cathepsins various synthetic peptides are used. Applying the tetra-peptide substrate library, Choe et al. compared CtsL, V, K, S, F, and B, papain, and bromelain. Most of these proteases prefer hydrophobic amino acids at the P2 position, in contrast to bromelain which favors basic amino acids [66]. All cathepsins cleave substrates with Arg and Lys at the P1 position, while at the P3 and P4 positions, substrates can contain various amino acids [66]. CtsB, L, and S specificity was compared using Z-FR-AMC (Z – benzyl chloroformate, AMC – 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin), Z-RR-AMC, Z-FK-AMC, and Z-KK-AMC. While CtsB efficiently cleaved all substrates, CtsL and S had little activity towards Z-RR-AMC and Z-KK-AMC [67]. There are several selective substrates for cysteine cathepsins. For example, the selective CtsB substrate (Ac-Cha-Leu-Glu(Bzl)-Arg-ACC (Ac – acetyl, Cha – cyclohexylalanin, Bzl – benzyl, ACC – 7-amino-4-carbamoylmethylcoumarin)) was digested by CtsB 3500-fold more efficiently than by CtsL [68]. Abz-HPG↓GPQ-EDDnp (Abz – 2-aminobenzoic acid, EDDnp – N-(2,4-dinitrophenyl)-ethylenediamine) was found to be a highly selective substrate for CtsK, which mainly depends on the specificity for Pro at P2 and P2′ and the ionization state of His at P3 [69]. GRWHTVG↓LRWE-Lys(Dnp)-DArg-NH2 (Dnp − 2,4-dinitrophenyl) substrate is selective for CtsS as compared with CtsB, H, L, and X [2], [70].

Most endogenous inhibitors of PLCPs bind to the binding site cleft. Thus, investigating PLCPs specificity to inhibitors may provide more information about the overall specificity of these proteases. PLCP specificity to different endogenous inhibitors allows for regulating the proteolytic network. Endogenous cysteine cathepsins inhibitors include cystatins (including stefins and kininogens), thyropins, and serpins, which are competitive reversible inhibitors [2]. Those cystatins which were shown to inhibit human cysteine cathepsins are listed in Table 2. The endogenous inhibitors of the cathepsins are characterized by various potency towards distinct proteases. For example, bovine stefins A, B, and C suppress the endopeptidases papain, CtsL, and S more efficiently than CtsB [71], [72], [73]. Mouse stefin A variants inhibit the endopeptidases CtsL and S to a greater extent than exopeptidases CtsB, C, and H [74]. Human cystatin C, stefin B, and chicken cystatin significantly reduce the activity of the endopeptidase cruzipain, cysteine protease of Trypanosoma cruzi [75]. CtsX can be inhibited by various cystatin-type protease inhibitors although a modeling study showed that the side chains of His23 and Tyr27 (Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID: 1EF7) collide with the residues Val55 and Ala56 in the QVVAG region of stefin B [76]. Bacterial leupeptin is an aldehyde that covalently binds to nucleophilic Ser and Cys at the active site of the serine and cysteine proteases, respectively [77]; however, it more potently inhibits cathepsins in rats rather than in humans [23]. Elastolytic activity of CtsV and K is inhibited by GAGs such as chondroitin sulfate [78]. Collagenase activity of CtsK is suppressed by the negatively charged polymers, polyglutamates, and oligonucleotides [2], [79]. Human CtsK and rat CtsB, H, K, and L can be inhibited by T-kininogen (only found in rats [80]) [81], [82]. Multiple PLCPs are negatively affected by reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species [83]. Papain, CtsB and K can be reversibly inhibited by nitric oxide via S-nitrosylation of their catalytic Cys, while hydrogen peroxide has been shown to oxidize triticain-α from Triticum aestivum L., CtsK, and S either to a reversible sulfenic acid or to an irreversible sulfonic acid [83]. S-Methyl methanethiosulfonate can induce the disulfide bond formation between Cys22 and catalytic Cys25 in triticain-α (active protease numbering), thus protecting the protease from irreversible oxidation [84].

Table 2.

Cystatins – the most investigated human endogenous inhibitors of the cysteine cathepsins. Further information on PLCP inhibitors can be found in MEROPS Database [1].

| Inhibitors | Cathepsins | KI | Recognition sequence | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cystatin A | CtsB CtsH CtsL CtsS |

8.2 nM 0.31 nM 1.3 nM 0.05 nM |

QVVAG | [85], [86] |

| Cystatin B | CtsB CtsH CtsL CtsS |

73 nM 0.58 nM 0.23 nM 0.07 nM |

||

| Cystatin C | CtsB CtsH CtsL CtsS |

0.25 nM 0.28 nM <0.005 nM 0.008 nM |

QIVAG | |

| Cystatin D | CtsB CtsH CtsL CtsS |

>1000 nM 8.5 nM 25 nM 0.24 nM |

QVMAA | [86] |

| Cystatin SN | CtsB | 19 nM | QTVGG | |

| Cystatin M/E | CtsB CtsL CtsV |

32 nM 1.78 nM 0.47 nM |

QLVAG | [87], [88] |

| Cystatin F | CtsL | 0.31 nM | QIVKG | [89] |

The variability of PLCP substrates and inhibitors enables modulating the proteolytic network. Some proteases can be inactive, while some other proteases are not. At the same time, certain proteases have limited activity performing various specific functions. For instance, CtsK can possess collagenase activity, while its elastolytic activity is suppressed [78]. The complexity of this network enables maintaining homeostasis. Still, there are other ways of regulating PLCPs activities to be discussed below.

2.2. Role of pH in PLCP activity and specificity

Hydrolysis takes place in water solution and the components of the solution can drastically change the effectiveness of the reaction. Such parameters as pH and ion strength influence the charges on amino acid residues and thus impact intra- and intermolecular interactions [90]. For instance, CtsB activation proceeds faster at acidic pH [2], [91] because CtsB propeptide binds into the binding groove of the protease more efficiently at pH 4.0 than at pH 6.0 [92]. At pH 5.5, the elastolytic activity of CtsCΔEx is lower than that of other cathepsins. In contrast, at pH 7.4, elastin is cleaved by CtsCΔEx more efficiently than by CtsB, L, and V and less efficiently than by CtsK and S [44]. pH5.5 hinders the digestion of collagen by CtsK and L, in contrast to pH 6.8 [93]. Even very similar proteases may exercise different activities at distinct pH levels. It was demonstrated by Matagne et al. who managed to separate distinct PLCPs from crude Ananas comosus proteases extract, usually referred as 'bromelain', and investigate their biochemical properties [94]. The basic bromelain forms 1 and 2 cleaved pGlu-FL-p-nitroanilide (pGlu – pyroglutamic acid) in the pH range of 4.0–4.5, while ananain form 2 cleaved the substrate in the range of 6.5–7.0 [95]. pH 6.0 was optimal for cleavage of Z-RR-AMC and Z-FR-AMC by basic bromelain form 1, while the optimum pH of the activity of its form 2 towards Z-FR-AMC and Z-RR-AMC was 6.0 and close to neutral, respectively [94]. Basic bromelain forms 1, 2, and 3 possess a decreased enzymatic activity under acidic conditions [94]. Both acidic bromelain forms are active at acidic pH as low as 4.0, except for the form 2 with Z-RR-AMC, while a significant loss in their activity is observed at pH 7 or above it [94]. The optimum pH for PLCPs from Toxocara canis larvae for digesting Z-FR-AMC and Z-RR-AMC were 5.0 and 6.5, respectively [14]. The reduction in cleavage ratio of Z-FR-AMC to Z-RR-AMC changed from 16:1 at pH 5.0 to about 1:1 at pH 6.5 suggesting that the deprotonation of Glu205 (papain numbering; PDB ID: 1BP4) in S2 increased the affinity to Arg [14], [96]. Fasciola hepatica CtsL2 (FhCL2) had 6-fold greater affinity for Z-PR-NH-AMC at pH 5.5 and 3-fold greater affinity at pH 7.3 than FhCL1 [97]. However, both FhCL2 and FhCL3 were able to digest native collagen at neutral pH, whereas CtsK required acidic conditions [13]. Wheat triticain-αefficiently degraded gluten in the pH range of 3.0–6.5 only [98]. Other plant PLCPs responsive to dehydration protease 21A (RD21A), RD21B, RD21C, RDL2, and CtsB-like protease 3 (CTB3) can be labeled by the activity-based probe MV201 at any pH, AALP was labeled only in a narrow neutral pH range, labeling xylem cysteine protease 1 (XCP1) and XCP2 was at wider range of neutral pH, while senescence-associated gene 12 protease (SAG12), RD19A, and RD19B labeling took place at acidic pH, and T helper type 1 immune response protease (THI1) labeling occured at basic pH [3].

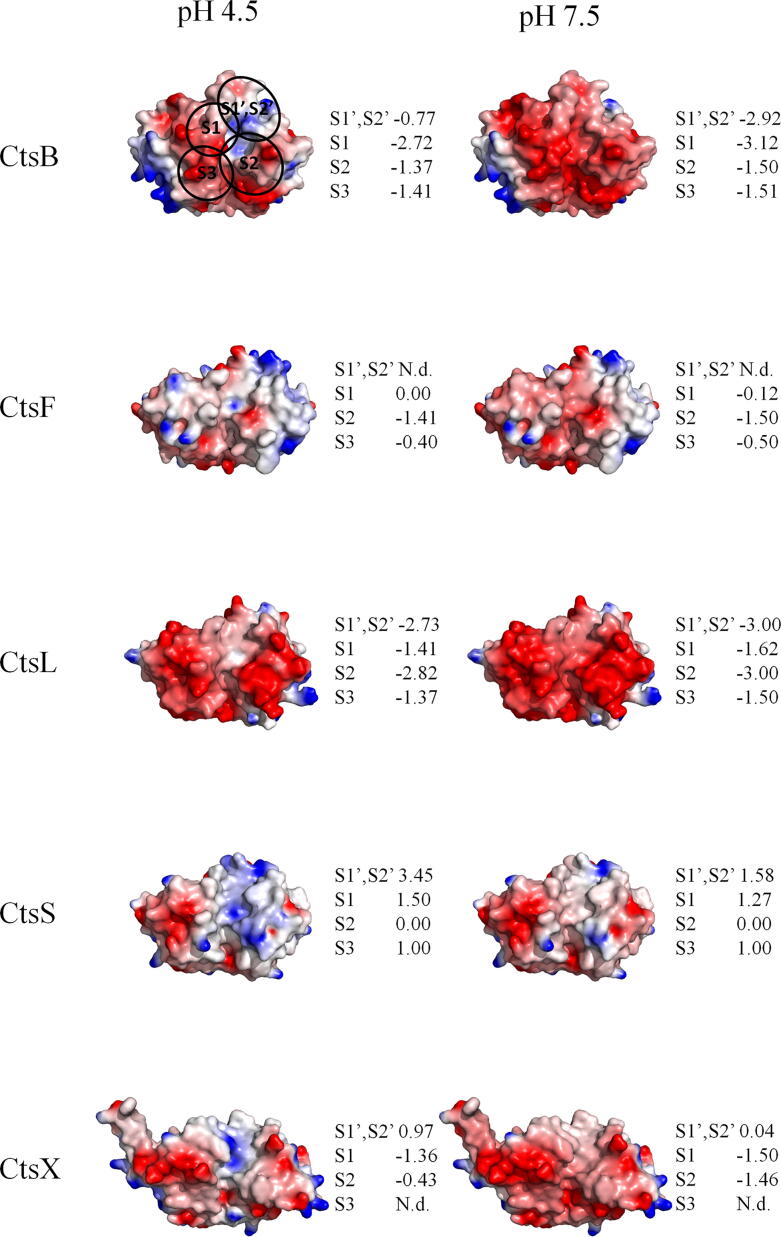

Distinct pKa values of the amino acid residues define distinct specificities at a range of pH. Fig. 1 represents significant differences between the charges on the surface of the enzymes at different pH. This feature directly influence the affinity to different substrates and can be used to develop specific inhibitors, which would suppress the enzymes at particular pH [99], such as the excessive activity of human cathepsins in extracellular space and cytosol in malignant tumors.

Fig. 1.

Charge distribution on the surface of different human cysteine cathepsins at pH 4.5 and 7.5 (PDB IDs: 1CSB for CtsB, 1M6D for CtsF, 1CJL for CtsL, 2FQ9 for CtsS, 1EF7 for CtsX) [76], [100], [101], [102], [103]. The electrostatic potential field was modelled using ProKSim (Protein Kinetics Simulator) software [104], [105]. The values of protein atom charges were automatically calculated using the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation according to standard values of the dissociation constant pKa for amino acid residues [106]. Surface of the protein colored by electrostatic potential value from − 100 mV (red) to + 100 mV (blue). The figure was created by PyMOL Molecular Graphics System [107]. The total charges of each binding pocket are shown to the right of each structure. They were calculated as a sum of the charges of the amino acid residues identified for the pockets. The disposition of the pockets indicated on the structure of CtsB and on Fig. 2. N.d. – not determined. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.3. Impact of ions on PLCP activity and specificity

The presence or absence of particular ions may also significantly affect the interactions between molecules. Ions can shield charges on the amino acid residues in the binding cleft of the protease thus preventing salt bridges from forming, or they can increase the strength of the hydrophobic interactions [108], [109]. Unlike CtsC, whose activity was investigated towards GF-p-nitroanilide at pH 5.0 and GF-4MβNA (4-methoxy-β-naphthylamide) at pH 3.6–8.2, CtsCΔEx did not require halide ions for enzymatic activity [110], [111]. However, CtsCΔEx optimal activity towards Z-LR-AMC at pH 5.6 was observed between 50 and 200 mM NaCl [44]. Specificity constants (kcat/KM) of CtsL and V for Abz-ALR↓SSKQ-EDDnp, Abz-KLR↓SSKQ-EDDnp, and Abz-ELR↓SSKQ-EDDnp were lower in the presence of NaCl. The hydrolysis of Abz-KLR↓SSKQ-EDDnp by CtsV was the most sensitive to NaCl. These results indicate the importance of the electrostatic interaction between the positively charged P3 and CtsL and V at pH 5.5. NaCl also reduced the CtsV activity at pH 5.5 towards elastin but not towards Z-FR-MCA (MCA − 7-methoxycoumarin-4-acetyl) [112]. Activity of all stem bromelain proteases for Z-RR-AMC and Z-FR-AMC at pH 6.25 was completely inhibited by 1 mM Zn2+, typical of PLCPs [113], [114], [115]. 10 mM Mg2+, Ca2+, and Mn2+ significantly suppressed the activity of basic bromelain forms 1, 2, and 3, ananain forms 1 and 2, and comosain [94]. A 25 % reduction in acidic bromelain 1 was observed in the presence of 10 mM Mn2+, but not of 10 mM Mg2+ or Ca2+. 0.1–1 mM Mg2+, 0.1–0.5 mM Mn2+, and 0.1–0.5 mM Ca2+ stimulated the activity of ananain form 1. The properties of the ananain form 2 were similar to form 1, however, the increase of the activity was observed at 0.1–5 mM of Mg2+ and 0.1 mM of Mn2+. 0.1–1 mM of Mn2+ also stimulated comosain [94]. The activity of the cysteine protease zingibain (from Zingiber officiale rhizomes) towards bovine casein at pH 7.0 was stimulated by 2 mM of Ca2+ and reduced in the presence of Zn2+, Mn2+, and Mg2+ [116]. Milk-clotting activity of procerain B from Calotropis procera was elevated by 0.01–10 mM Mn2+ and completely abolished by 0.01–10 mM of Zn2+ at pH 7.5 [117]. Caseinolytic activity of microcarpain from the Ficus microcarpa latex was suppressed by 42 %, 79 %, 85 %, and 92 % by Ca2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, and Zn2+ at 5 mM concentration, respectively, at pH 8.0 [94], [118]. The protease from Parabacteroides distasonis (Pd_dinase) was inhibited by excessive Zn2+ via a coordination of Cys56, His340, and the side-chain carboxylate oxygens of Asp298 at pH 8.0. As a result, the tip of the flexible loop (residues 290–310) occluded the active site pocket [119].

Except for Zn2+ inhibiting PLCPs, other ions can either suppress or stimulate PLCP activity depending on the enzyme. Normally the excessive concentrations (5 mM or more) of bivalent ions inhibit PLCPs. However, at low concentrations the impact differs. The possible explanation is that in some cases charged residues play important role in substrate binding while ions shield these residues. On the other hand, large ionic strength favors hydrophobic interactions [108], [109].

2.4. Macromolecules in regulation of PLCP activity and specificity

The propeptides inhibiting PLCPs can also promote their folding and affect their activity and even specificity. The X-ray structures of the papain zymogen, enzyme kinetic analyses, intact and tryptic digested peptide mass analyses, and circular dichroism data of mature proteases showed that mutations in the propeptide induce the conformation changes in the mature papain altering its activity and specificity [120].

The inhibitors that abolish or suppress PLCP activity were already discussed above in detail. Meanwhile, there are other molecules that can promote the digestion efficiency. For instance, GAGs were shown to regulate the collagenolytic activity of CtsK [78], [121], [122]. The collagenolytic activity of CtsK was stimulated by chondroitin and keratan sulfate and inhibited by heparan sulfate or heparin [2]. CtsK-dependent cleavage of triple collagen helix requires the complex with chondroitin sulfate to be formed [121]. Chondroitin sulfate binds and orients several CtsK molecules in 'beads-on-a-string' orientation [123]. However, substituting the binding site for chondroitin into the CtsL-like site did not abolish the collagenase activity [2]. The autocatalytic activation of cathepsins was also facilitated by the negatively charged molecules, such as GAGs and dextran sulfate [124], [125].

To sum up, the specificity of PLCPs is quite variable and tightly regulated by pH level, ions, inhibitors, and other molecules. Even the protease prodomain is crucial for the activity of the mature enzyme. All these regulation mechanisms are specific and determined by the structure of a particular protease.

3. Structure of cysteine cathepsins

While describing structures of PLCPs, we will discuss the particular amino acid residues of cysteine cathepsin binding clefts. Their numbers are indicated according to the following PDB structures unless indicated otherwise: 1BP4 for papain, 1CSB for CtsB, 1M6D for CtsF, 1ATK for CtsK, 1CJL for CtsL, 2FQ9 for CtsS, 1FH0 for CtsV, 1EF7 for CtsX [76], [96], [100], [101], [102], [103], [126], [127].

3.1. The general structure of cysteine cathepsins

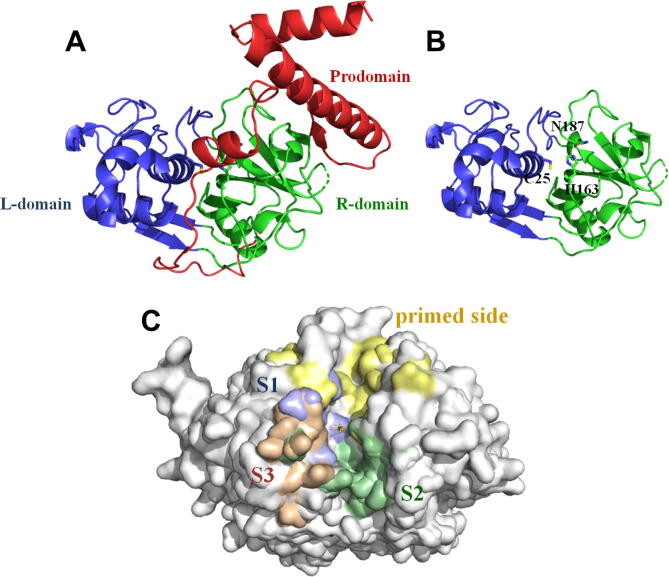

The general structure of animal PLCPs is presented on Fig. 2. It is similar to that of papain and consists of two domains: the left N-terminal domain consisting of α-helices (l-domain) and the right C-terminal domain comprising a β-barrel and a short α-helical motif (R-domain) (Fig. 2A) [128]. The domains form a ‘V-shaped’ active site cleft containing a catalytic triad of Cys, His, and Asn (Fig. 2B) [2], [76]. The catalytic domain of the pro-cathepsins is preserved in the active conformation, with the prodomain interacting with the proregion binding loop and the substrate-binding site. The corresponding contacting surfaces of the prodomain and the catalytic domain have opposite electrostatic characters [129].

Fig. 2.

The common structural features of human cysteine cathepsins. A. Prodomain ( ), L- (

), L- ( ) and R-domains (

) and R-domains ( ) of pro-CtsL (PDB ID: 1CJL) [103]. B. Active form of CtsL with the catalytic residues indicated (PDB ID: 1CJL) [103]. C. The substrate binding pockets S1 (

) of pro-CtsL (PDB ID: 1CJL) [103]. B. Active form of CtsL with the catalytic residues indicated (PDB ID: 1CJL) [103]. C. The substrate binding pockets S1 ( ), S2 (

), S2 ( ), S3 (

), S3 ( ), and primed side (

), and primed side ( ) of the binding cleft on the surface of PLCPs. The figure shows the aligned structures of CtsB, F, L, S, X, K, and V (PDB IDs: 1CSB, 1M6D, 1CJL, 2FQ9, 1EF7, 1ATK, and 1FH0, respectively) [76], [100], [101], [102], [103], [126], [127]. The catalytic Cys are indicated. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System was used to create the figure [107]. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

) of the binding cleft on the surface of PLCPs. The figure shows the aligned structures of CtsB, F, L, S, X, K, and V (PDB IDs: 1CSB, 1M6D, 1CJL, 2FQ9, 1EF7, 1ATK, and 1FH0, respectively) [76], [100], [101], [102], [103], [126], [127]. The catalytic Cys are indicated. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System was used to create the figure [107]. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Cysteine cathepsins have distinct structural features as well. Based on sequence analysis, the cathepsins can be divided into two distinct subfamilies, designated as CtsL-like and CtsB-like proteases [130], [131]. Propeptides of the CtsL subfamily (CtsL, V, K, S, W, F, and H) contain a propeptide of about 100 residues with two conserved motifs: the ERFNIN and the GNFD ones. The proteases in CtsB subfamily either lack only the GNFD motif (CtsB) or both of them (CtsC, O, and X) [2]. All proteases can also be classified according to the structure of their catalytic cleft. In case of human cysteine cathepsins in endopeptidases CtsF, L, K, S, V, and W, the active-site cleft is extended on both sides from catalytic cysteine [132]. In carboxypeptidases CtsB and X and in aminopeptidases CtsH and C, the binding sites are located only on the non-primed side and on the primed side, respectively. The other side of the cleft is filled with the additional domains [132]. The occluding loop of CtsB and the mini-loop of CtsX contain His residues to dock the C-terminal carboxylic group of a substrate. The CtsH mini-chain and the CtsC exclusion domain carry carboxylic groups for docking the positively charged N-terminus of the substrates [133], [134]. The mutations of His residues in the occluding loop and deletion of the loop demonstrated their importance for the CtsB endopeptidase activity [2], [135], [136].

The binding cleft is indicated on a PLCP structure on Fig. 2C. It consists of two parts: the non-primed side for binding of the N-terminal side of a substrate (S1, S2, S3, etc.) and the primed side for binding of the C-terminal side of a substrate (S1′, S2′, S3′, etc.). The amino acids located in these areas define the specificity of a protease in the first place, so we will pay special attention to them in the remaining part of the review.

3.2. Structure and specificity of S1 binding site

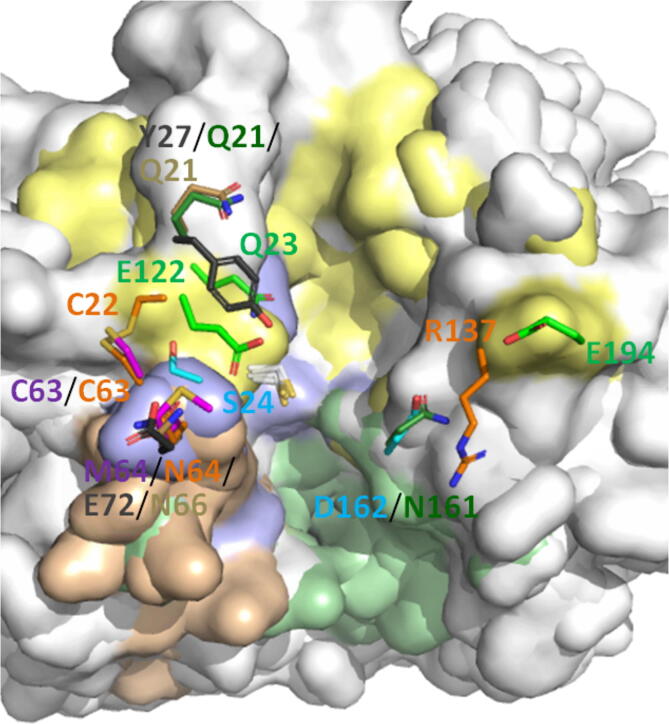

The S1 binding site of PLCPs binds the first amino acid from the cleavage site on the N-terminal side. Its structure is a groove in the wall of the left domain [137] formed by Ser21, Cys22, and Gly23 on one side and Gly62, Cys63, and Asn64 on the other side that are bridged by the disulfide bond Cys22-Cys63 (papain numbering) [76]. The residues in S1 of the cathepsins, which were shown to interact with the substrates, are illustrated on Fig. 3 and discussed further in the present subsection. The S1 site of CtsB is mainly composed of Gln23, Gly27, Cys29, Gly74, and Gly198 [138]. CtsB prefers Arg and Lys in the P1 position among all natural residues because the occluding loop harbours the negatively charged Glu122. However, it also well accommodates Tyr, norleucine (Nle), Thr and Gly [139], while some artificial bulky and hydrophobic derivatives of Lys and Cys (Lys(2-Cl-Z), Cys(Bzl), Cys(Me-Bzl) (Me – methyl), Cys(MeOBzl), as well as Nle(OBzl)) are hydrolyzed faster than Arg [68]. The S1 pocket is shallow in the L domain of CtsF and is created by Gly23, Cys63, Met64, and Gly65. Only Met64 side chain participates in forming the pocket, this residue being unique among various PLCPs [102]. CtsF prefers the positively charged amino acid residues at P1 as well [66]. Gly65 at this position is conserved across human cysteine cathepsins, while Gly23 is conserved in the family except for CtsW (Gly is replaced with Asn) [102]. The S1 subsite of CtsV hydrolyzes the substrates with Leu, Gln, Arg, and Lys at P1 because of the aliphatic side chains in S1, while CtsL prefers Arg followed by Lys at P1 [112]. Substrates with the negatively charged and polar non-charged residues at P1 are poorly hydrolyzed by CtsL and V [112]. Pro is the least favored residue at P1 [112]. CtsK also prefers positively charged residues and Gly at P1 [2], [69]. In CtsX, S1 is deeper than in other PLCPs because of the Tyr27 benzoyl ring pointing to the catalytic Cys [76]. The Glu72 side chain provides a negative charge, which is not unique for PLCPs. This function is performed by Asp72 in actinidin and Glu122 in the occluding loop in CtsB. S1 binding site of CtsX prefers Arg [76]. Arg137 introduces a positive charge modulating the local electrostatics at the CtsS active site, but the specificity of CtsS to negatively charged amino acids at P1 was not reported. The CtsS S1 pocket also contains the main-chain atoms of Gly23, Cys63, Asn64, Gly65, and the ones of the Cys22-Cys63 disulfide [137], [140].

Fig. 3.

Amino acid residues of the S1 binding pocket of human cysteine cathepsins. The figure shows the aligned structures of CtsB, F, L, S, X, K, and V (PDB IDs: 1CSB, 1M6D, 1CJL, 2FQ9, 1EF7, 1ATK, and 1FH0, respectively) [76], [100], [101], [102], [103], [126], [127]. Binding sites are indicated by the same colors as on Fig. 2. Amino acid residues of CtsB are  , CtsF –

, CtsF –  , CtsL –

, CtsL –  , CtsS –

, CtsS –  , CtsX – black, CtsK –

, CtsX – black, CtsK –  , and CtsV –

, and CtsV –  . Arrows indicate the binding groove. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System was used to create the figure [107]. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

. Arrows indicate the binding groove. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System was used to create the figure [107]. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

As we can see, PLCPs mainly prefer positive charges at the P1 positions of their substrates since they have acidic amino acids at the S1 subsite (Fig. 3). Still, some of the most advanced clinical cathepsin inhibitors possess non-polar substituents at P1 [141], [142]. On the other hand, CtsK inhibitor L-873724 was improved by replacement of isobutyl with more polar 4-fluoroleucine at P1, which resulted in a new perspective clinical inhibitor odanacatib [143]. Thus the key to further improvement of potency of the cathepsin inhibitors may be in the optimization of P1 substituents.

3.3. Structure and specificity of S2 binding site

The S2 subsite of PLCPs is considered the most crucial binding spot [90]. It comprises the residues at positions 67, 68, 86, 133, 157, 160, and 205 (papain numbering), which are quite variable among PLCPs [13]. In contrast to the positively charged P1 amino acid residue, PLCPs mainly prefer bulky hydrophobic side chains (such as Phe) at P2 [66], [144]. The residues in S2 of the cathepsins, which were shown to form bonds with the substrates, are illustrated on Fig. 4 and discussed further in the present subsection. The hydrophobic S2 subsite of CtsL is formed by Leu69, Met70, Ala135, Met161, and Gly164 at the bottom [128]. The side chain of Met70 (Pro76 for CtsB) lies across the cleft resulting in a shallower S2 pocket. If we look down the active site cleft of CtsL, orienting the primed subsites being above and unprimed subsites below, Asp160, Met161, Asp162, and Ala214 form a wall on the side of the S2 pocket [128]. Despite Asp160 and Asp162 at the S2 subsite, CtsL prefers aromatic residues, mostly Phe, Trp, Tyr and also Leu. The specificity to aromatic residues distincts CtsL from other cysteine cathepsins with exception for CtsV [61], [66]. CtsS is specific to hydrophobic Val, Met, and Nle at the P2 position [2], [70]. The deep S2 pocket of CtsS is formed by the side chain of Met68 and the methylene groups of Gly133 and Gly160 at its bottom; the side chains of Phe67 and Val157 shape its sides, and the side chain of Phe205 at the distal position closes the pocket [138]. Gly133, Val157, and Phe205 are unique residues present in CtsS [140]. Gly133 of CtsS is substituted by Ala in CtsK, L, and V so that CtsS has the deeper S2 pocket than the other cathepsins. Conversely, Val157 is replaced with Leu in CtsK and V and Met in CtsL. In CtsS, this residue restricts the entrance into the S2 pocket [138]. Phe205 (Leu in CtsK or Ala in CtsV and L) defines the specificity of CtsS to branched hydrophobic P2 residues [137]. The side chain of Phe205 in S2 of CtsS facilitates two conformations that accommodate either Leu or a bulkier side chain of Phe at the P2 site, which is a unique feature for CtsS [140]. Phe205 in the open position is stabilized by interactions with the aromatic ring of Tyr118 and the side chain of Val157 [140]. The Phe205Glu substitution in CtsS leads to a decreased affinity to hydrophobic residues at P2 but 77 times more efficient digestion of the RR dipeptide [90]. The S2 site of CtsV requires hydrophobic residues with a preference for Phe and Leu leading to a less efficient cleavage of peptides containing Tyr, Val, and Ile at the P2 position. Trp appeared to be least favorable among hydrophobic residues at the P2 position [112]. The S2 pocket of CtsF is also hydrophobic being formed by Leu67, Pro68, Ala133, Ala160, and Met205 [102]. The width of the S2 pocket is determined by Leu67 on one side, and Ile157 and Asp158 on the other side of the pocket [102]. The amino acids at the P2 position influence the specificity to inhibitors. Peptides carrying epoxide warheads with hydrophobic residues (Leu, Ile, Phe, nor-Ile, Trp, Tyr, Val) at P2 more efficiently inhibit PLCPs than peptides containing small or hydrophilic residues (Ala, Asp, Glu, Lys, Gln, Gly, His, Pro, Ser, Arg, Thr) at P2 [3].

Fig. 4.

Amino acid residues of the S2 binding pocket of human cysteine cathepsins. The figure shows the aligned structures of CtsB, F, L, S, X, K, and V (PDB IDs: 1CSB, 1M6D, 1CJL, 2FQ9, 1EF7, 1ATK, and 1FH0, respectively) [76], [100], [101], [102], [103], [126], [127]. Binding sites are indicated by the same colors as on Fig. 2. Amino acid residues of CtsB are  , CtsF –

, CtsF –  , CtsL –

, CtsL –  , CtsS –

, CtsS –  , CtsX – black, CtsK –

, CtsX – black, CtsK –  , and CtsV –

, and CtsV –  . Arrows indicate the binding groove. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System was used to create the figure [107]. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

. Arrows indicate the binding groove. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System was used to create the figure [107]. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Some PLCPs possess unique specificity to Pro at P2 resulting in a collagenolytic activity. The S2 subsite of CtsK consists of Tyr67, Met68, Ala134, Leu160, Ala163, and Leu209 [23]. The side chains of Tyr67, Leu160, and Leu209 form a barrier to substrate binding, as in CtsB, limiting the length of the substrate and probably determining the specificity to Pro in the S2 position and collagenolytic activity of CtsK [138]. This preference is unique among the mammalian cysteine cathepsins [145]. CtsK can cleave synthetic substrates containing either Pro or Phe at the P2 position. Nevertheless, it preferentially cleaves type I collagen after Pro20 at P2, while CtsL cleaves after Phe23 at P2 [93]. The mutations Tyr67Leu and Leu209Ala (as in CtsL) abolished the Pro specificity and collagenolytic activity of CtsK [13], [146], whereas the reverse mutations Leu69Tyr and Ala214Leu in CtsL introduced Pro specificity [147]. Rat CtsK displays similar preferences, but rat CtsK has weaker peptidase activity than human CtsK [148]. The Ser134Ala and Val160Leu mutants (the same as in human CtsK) are more active than the WT enzymes (human CtsK numbering) [149]. Similar to other PLCPs, CtsCΔEx prefers the P2 position containing large hydrophobic residues (Phe, Leu, or Pro, but not Val) [44]. It efficiently digests Z-FR-AMC, Z-LR-AMC, and Boc-VLK-AMC. However, it can also digest Z-GPR-AMC containing Pro at P2. Almost no activity was detected in case of Bz-Arg-AMC (Bz – benzoyl) and small hydrophobic residues (Val, Ala, or Gly) or Arg at the P2 position [44].

Some cathepsins can also accommodate polar amino acid residues at the P2 position. The S2 subsite of CtsB comprises Pro76, Ala173, Gly198, Ala200, and Glu245 [138]. CtsB binds bulky hydrophobic amino acids (homoserine(Bzl) (hSer(Bzl)), Glu(Bzl), or Glu(Chx) (Chx – cycloheximide)) at the P2 position, synthetic residues being recognized better than natural amino acids [68]. But unlike most cathepsins, the S2 subsite of CtsB has a negative charge of the Glu245 side chain, which enables the binding of CtsB with the positively charged residues (Arg, Lys, and His) of P2 at neutral pH levels [138], [144], [150]. Glu245Gln mutation in CtsB limited the digestion of substrates that contain Arg at P2 but had no effect on the P2 Phe substrates [2], [151]. However, at acidic pH levels CtsB can digest the substrates with Glu at P2 [99]. CtsX S2 pocket is formed by Gly74, Asp76, Gly154, Ile178, Val181, and His234 [76]. The Gly74 amide proton and carbonyl oxygen interact with the main-chain carbonyl and amide group of a P2 residue. Asp76 is unique for CtsX and being substituted by a hydrophobic residue (Met or Pro) in other cathepsins; His234 is replaced with conserved Ser205 (papain numbering) in other PLCPs. S2 Asp76 and His234 of CtsX define the specificity to the substrates with long side chains with a hydrophilic tail at the P2 position [76].

It is well known that PLCPs are usually specific to hydrophobic amino acids at P2 of substrate since they contain a hydrophobic S2 pocket (Fig. 4). However, in some of the PLCPs, a charged amino acid located between S1 and S2 binding pockets (Glu245 in CtsB, Asp76 and His234 in CtsX, etc.) promotes binding of hydrophilic amino acids. CtsK possesses a unique specificity to P2 Pro enabling the cleavage of intact collagen triple helices. The amino acid residues responsible for this reaction were identified enabling redesigning CtsL to cleave collagen in a manner similar to CtsK [93].

3.4. Structure and specificity of S3 binding site

The S3 binding site possesses a lower specificity than the S2 subsite, although amino acids with a side chain in the P3 position are essential for the CtsV and L activity [112]. The residues in S3 of the cathepsins, which were shown to be involved in interactions with the substrates, are illustrated on Fig. 5 and discussed further in the present subsection. The central part of the CtsL S3 subsite contains Gly67 and Gly68 surrounded by the side chains of Glu63, Asn66, and Leu69 and the carbonyl oxygen of Gly61 [128]. CtsL favors both basic amino acids (Lys and Arg) in the P3 position since it contains the acidic Glu63 at the S3 subsite [112], as well as aliphatic residues [66]. S3 of CtsB favors its specificity to aliphatic side chains (Leu, Nle, hCha, 2-aminooctnoic acid (2Aoc), hLeu, octahydroindole-2-carboxylic acid (Oic)) and basic amino acids as well Phe-derivatives [68]. CtsK prefers the positively charged residues at P3 [2], [69]. The S3 pocket of CtsF is formed by Gly65 and Gly66 (conserved among PLCPs), the side-chains of Asp60, Lys61, Leu67, Asn70, and the carbonyl oxygen of Met59 [102]. Residues 67 and 61 vary widely across the PLCPs. In CtsF, residue 60 is Asp, whereas in other enzymes, it is represented by Gly, Ala, or most commonly, Asn [102].

Fig. 5.

Amino acid residues of the S3 binding pocket of human cysteine cathepsins. The figure shows the aligned structures of CtsB, F, L, S, X, K, and V (PDB IDs: 1CSB, 1M6D, 1CJL, 2FQ9, 1EF7, 1ATK, and 1FH0, respectively) [76], [100], [101], [102], [103], [126], [127]. Binding sites are indicated by the same colors as on Fig. 2. Amino acid residues of CtsB are  , CtsF –

, CtsF –  , CtsL –

, CtsL –  , CtsS –

, CtsS –  , CtsX – black, CtsK –

, CtsX – black, CtsK –  , and CtsV –

, and CtsV –  . Arrows indicate the binding groove. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System was used to create the figure [107]. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

. Arrows indicate the binding groove. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System was used to create the figure [107]. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

CtsS contains a three-residue insertion relative to CtsK in the loop between Ser57 and Asn60 in the S3 pocket [140]. In CtsL and V, the insertion is only two amino acid residue long. Therefore, CtsS has a smaller S3 pocket than the other cathepsins [140]. The S3 subsite of CtsS contains Gly65 and Gly66, the side chains of Lys61 and Phe67, and the backbone atoms of Gly59 and Asn60. Lys61 (Asp in CtsK, Gln in CtsV, and Glu in CtsL) and Gly59 (Glu in CtsK and Gly in CtsV and L) are unique for the S3 pocket of PLCP [140]. The positively charged side chains of Lys61 and of Phe67 form a specific binding site [138]. CtsV S3 subsite is composed of Gln60 and Arg72, which is a distinct feature of CtsV. Thus, CtsV prefers substrates with a negatively charged Glu in the P3 position, which may interact with the guanidino group of Arg72 in the S3 [112].

Such diversity of amino acids that enables substrate cleavage by different PLCPs indicates a low specificity of this pocket. Similarly to the S2 binding site, the S3 binding site generally contains hydrophobic amino acids. However, some human cysteine cathepsins harbor negatively charged (Asp60 in CtsF and Glu63 in CtsL) or positively charged (Lys61 in CtsS and Arg72 in CtsV) amino acid residue at S3 (Fig. 5) expanding the range of sensitive substrates.

3.5. Structure and specificity of the primed side

The abovementioned S1-S3 binding sites are referred to the non-primed side of the active cleft. The C-terminal part of the substrate binds to the so-called primed side of the binding cleft. It is less thoroughly investigated than the other side of the binding cleft but there are still some noteworthy features [2]. The residues in the primed side of the cathepsins able to interact with the substrates are illustrated on Fig. 6 and discussed further in the present subsection. S1′ of CtsL possesses Glu141 and Glu192 that make this subsite negatively charged [112]. CtsL most efficiently cleaves the substrates with His, Asn, Phe, and Ser at P1′ and less efficiently digests ligands with Arg, Gln, Gly, and Val. Glu at P1′ was the least favorable substrate, while the substrate with Pro at P1′ was resistant to hydrolysis [112]. The S2′ position of CtsL is hydrophobic and is formed by highly conserved Trp189 and Trp193 [129]. CtsL seems to lack a clear preference for residues at P2′, but Ser and Glu are the most and least preferable residues, respectively [112]. The primed side of CtsL also contains Asn18, Gly20, Gln21, and Leu144 [128].

Fig. 6.

Amino acid residues of the binding pocket primed side in human cysteine cathepsins. The figure shows the aligned structures of CtsB, F, L, S, X, K, and V (PDB IDs: 1CSB, 1M6D, 1CJL, 2FQ9, 1EF7, 1ATK, and 1FH0, respectively) [76], [100], [101], [102], [103], [126], [127]. Binding sites are indicated by the same colors as on Fig. 2. Amino acid residues of CtsB are  , CtsF –

, CtsF –  , CtsL –

, CtsL –  , CtsS –

, CtsS –  , CtsX – black, CtsK –

, CtsX – black, CtsK –  , and CtsV –

, and CtsV –  . Arrows indicate the binding groove. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System was used to create the figure [107]. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

. Arrows indicate the binding groove. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System was used to create the figure [107]. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In CtsB, S1 and S1′ are negatively charged because of Glu122 and Glu194 side chains [138]. However, the occluding loop (105–125) of CtsB exposes the positively charged His110 and His111 in the S3′ subsite [138]. It limits the length and orientation of a substrate underlying CtsB exopeptidase activity [138]. CtsX contains Trp202 in its S1′ binding pocket [76]. The three residues in the mini-loop of CtsX (Ile24, Pro25, and Gln26) form the wall of the S2′ binding site, which is occupied by the imidazole ring of His23. In turn, His23 can interact with the C-terminal carboxylic group of a substrate [76]. CtsX can be inhibited by CA074, an epoxysuccinyl-based inhibitor with IP dipeptide which binds to S1′ and S2′; however, the His23 ring is rotated into a position equivalent to a position occupied by His110 in CtsB to create an open S2′ [76].

The proximal S1′ of CtsS consists of His159 and Trp177 at its bottom and Ala136, Arg137, and Asn158 in the walls of the pocket [140]. Arg137 is an unusual residue as papain, cruzain, and CtsL, K, and B have Ala, Ser, Gly, Ser, and Tyr at the corresponding position, respectively [137], [140]. The S1′ distal subsite is defined by the main chain atoms of His138 and Pro139 and the side chain of Phe142 [140]. Phe142 (Gln in CtsK and V and Leu in CtsL) can form a hydrophobic interaction with the substrate [138], and CtsS was shown to prefer hydrophobic branched side chains at the P1′ [2], [70].

In CtsV the preferable amino acid residue at S1′ was Val, followed by Asn and Ser [112]. CtsV also hydrolyzes substrates with Arg or Glu at P1′ with low but similar efficiency. The peptides with Pro at P1′ are resistant to hydrolysis. At S2′ of CtsV, Val and Ile are the most preferable amino acids [112].

The primed side of most PLCPs is formed by two Trp residues which may form the stacking bonds with large aromatic amino acids of the substrate. However, the S1′ binding sites of PLCPs generally contain charged amino acids enabling the interactions with basic (CtsB and L), acidic (CtsS), or both types of the charged amino acid residues (CtsV). The S2′ binding site in endopeptidases is hydrophobic, while carboxypeptidases CtsB and X possess positively charged His residues which interact with the C-terminal carboxylic group of a substrate (Fig. 6). Different structural features of the binding cleft of PLCPs allow for determining the specific substrates even for similar proteases. These differences facilitate the development of selective inhibitors or probes for PLCPs that can be further used in therapy and diagnostics.

4. Examples of rationally designed PLCP inhibitors

The activity of proteases is commonly modulated through their inhibition. PLCP inhibitors mainly interact with the S1, S2, S3, and S1′ pockets of the protease [102]. Thus, knowing the structure and specificity (Table 3) of each binding site, we can develop an effective inhibitor as those discussed in the present subsection and listed in Table 4. E-64 is a non-selective inhibitor of all the cysteine cathepsins (except for CtsC) and the calpain [2], [155]. The inhibitor was modified to obtain a specific CtsB inhibitor via mimicking a carboxy-terminal dipeptide by replacing the terminal guanidinobutylamine of E-64 with Pro and terminating the chain with a free carboxylic group [152], [153]. Modifications of the other terminus of the epoxysuccinyls to various ester and amide derivatives resulted in new inhibitors named CA030 and CA074 [152], [153]. KI of CA030 were 4.38, 42,900, and 40,000 nM, while KI of CA074 were 1.94, 75,000, and 233,000 nM for CtsB, H, and L, respectively [152]. The crystal structure (illustrated on Fig. 7) confirmed the key role of residues His110 and His111 in the occluding loop of CtsB in C-terminal carboxylic group recognition at S2′ binding site [101]. CtsX can also be inhibited by CA074 in case the His23 ring is rotated into a position equivalent to a position occupied by His110 in CtsB to create an open S2′ (Fig. 7) [76].

Table 3.

Amino acid residues at the positions P3 to P3′ of ligands interacting with the binding clefts of the listed proteases. The table is based on the sources cited in the present review. Hydrophobic amino acid residues are shown in gray, aromatic ones are shown in  , polar uncharged amino acids are shown in

, polar uncharged amino acids are shown in  , positively charged amino acids are shown in

, positively charged amino acids are shown in  , and negatively charged amino acids are shown in

, and negatively charged amino acids are shown in  . The graphs in the first column visualize types of amino acids favored in indicated positions [154].

. The graphs in the first column visualize types of amino acids favored in indicated positions [154].

|

Table 4.

Examples of selective cathepsin inhibitors.

| Inhibitors | Cathepsins | KI | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA030 | CtsB | 4.38 nM | [152] |

| CA074 | 1.94 nM | ||

| Z-RK-AOMK | CtsB | 130 nM at pH 7.2 15,000 nM at pH 4.6 |

[99] |

| 4-morpholinecarbonyl-Leu-hPhe-Ψ(CH = CH-SO2-Ph) | CtsS | 13 nM | [156] |

| 4-morpholinecarbonyl-Phe-hPhe-Ψ(CH = CH-SO2-Ph) | 18 nM | ||

| μHLFRSAAAμ (RS3A) | CtsL | 0.52 µ | [161] |

| μHLFRSAμ (RS1A) | 1.11 µM | ||

| N-Desmethyl thalassospiramide C | CtsK | IC50 = 3 nM | [157] |

| CtsL | IC50 = 1 nM |

Fig. 7.

The crystal structure of the complex of CA030 ( ) bound to CtsB (

) bound to CtsB ( surface; PDB ID: 1CSB) [100], [101]. In PyMOL, the crystal structure of CtsX (PDB ID: 1EF7) was aligned to the structure of CtsB to compare the localization of the residues involved in interactions with the inhibitor [76], [107]. The residues of CtsB are

surface; PDB ID: 1CSB) [100], [101]. In PyMOL, the crystal structure of CtsX (PDB ID: 1EF7) was aligned to the structure of CtsB to compare the localization of the residues involved in interactions with the inhibitor [76], [107]. The residues of CtsB are  and the residue of CtsX is black. His23 is illustrated in 'closed' position. Dashed line indicates possible non-covalent bond. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

and the residue of CtsX is black. His23 is illustrated in 'closed' position. Dashed line indicates possible non-covalent bond. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Experimental measurements with a series of vinyl sulfone inhibitors with different P2 substituents revealed that the inhibitors containing P2-Leu and P2-Phe are the most effective for CtsS [156]. They inhibited the protease with similar KI of 13 and 18 nM, respectively. The vinyl sulfone inhibitors with P2-Leu and P2-Phe showed less effective inhibition of the other cysteine cathepsins: respective KI values were 110 nM and 36 µM for CtsK and 120 nM and 110 nM for CtsL [156]. The crystal structures of two covalent inhibitors, vinyl sulfone inhibitor (4-morpholinecarbonyl-Leu-hPhe-Ψ(CH = CH-SO2-Ph), Ph – phenyl) with P2-Leu and the aldehyde inhibitor (4-morpholinecarbonyl-Phe-(SBz)Cys-Ψ(CH = O), SBz – benzylthioester) with P2-Phe, in a complex with CtsS were obtained and described [140]. According to structural data, the good packing of either P2-Leu or P2-Phe in the S2 pocket of CtsS is accomplished through the conformational adjustment of Phe211 (PDB ID: 1NPZ) [140]. CtsK contains a more rigid Leu209, while Ala is found at this position in CtsL and V, which is illustrated on Fig. 8. Another distinctive structural feature is Lys64 in the S3 subsite of CtsS. In the investigated complexes the partially negatively charged ether oxygen of the P3-morpholine ring is located nearby the NH3+ group of Lys64 (PDB ID: 1NPZ) [140]. The positively charged Lys64 is substituted with an acidic residue in CtsK and CtsL and with a neutral but polar residue in CtsV (Fig. 8) [140].

Fig. 8.

Crystal structure of the complex of the vinyl sulfone inhibitor ( ) bound to CtsS (

) bound to CtsS ( surface; PDB ID: 1NPZ) [100], [140]. In PyMOL, the crystal structures of CtsK, L, and V (PDB IDs: 1ATK, 1CJL, and 1FH0, respectively) were aligned to the structure of CtsS to compare the localization of the residues involved in interactions with the inhibitor [103], [107], [126], [127]. The residues of CtsS are

surface; PDB ID: 1NPZ) [100], [140]. In PyMOL, the crystal structures of CtsK, L, and V (PDB IDs: 1ATK, 1CJL, and 1FH0, respectively) were aligned to the structure of CtsS to compare the localization of the residues involved in interactions with the inhibitor [103], [107], [126], [127]. The residues of CtsS are  , the residues of CtsK are

, the residues of CtsK are  , the residues of CtsL are

, the residues of CtsL are  , and the residues of CtsV are

, and the residues of CtsV are  . Dashed lines indicate possible non-covalent bonds. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

. Dashed lines indicate possible non-covalent bonds. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

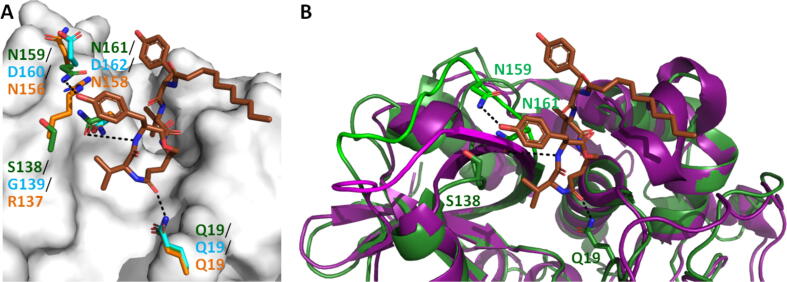

N-Desmethyl thalassospiramide C covalent inhibitor was developed as a cysteine cathepsin inhibitor and its binding modes in different cathepsins have been described [157]. Biochemical research showed that the inhibitor is selective for CtsK and L (respective IC50 is 3 nM and 1 nM) and suppresses CtsB and S less effective (respective IC50 is 65 nM and 46 nM) [157]. The complex of the inhibitor with CtsK was crystallized and its detailed structural analysis by X-ray crystallography was conducted (PDB ID: 6HGY) [157]. The macrocycle of the inhibitor is anchored in the S1′ site of the enzyme and interacts with Asn161 and Gln19 (Fig. 9). The S1′ pocket of CtsL is similar to CtsK and there is no steric interference with the bound conformation of the inhibitor [158]. By contrast, Ser138Arg substitution in CtsS may hinder binding of the C11–C12 region of the inhibitor [159]. CtsB has an alternative fold in the S1′ site, which is unique in the cathepsin family [160]. This conformational differences may account for the lower potency in CtsB and S (Fig. 9) [157].

Fig. 9.

A. Crystal structure of the complex of N-Desmethyl thalassospiramide C covalent inhibitor ( ) bound to CtsK (

) bound to CtsK ( surface; PDB ID: 6HGY) [100], [157]. In PyMOL, the crystal structures of CtsL and S (PDB IDs: 1CJL and 2FQ9, respectively) were aligned to the structure of CtsK to compare the localization of the residues involved in interactions with the inhibitor [103], [107]. The residues of CtsK are

surface; PDB ID: 6HGY) [100], [157]. In PyMOL, the crystal structures of CtsL and S (PDB IDs: 1CJL and 2FQ9, respectively) were aligned to the structure of CtsK to compare the localization of the residues involved in interactions with the inhibitor [103], [107]. The residues of CtsK are  , the residues of CtsL are

, the residues of CtsL are  , and the residues of CtsS are

, and the residues of CtsS are  . B. Crystal structure of the complex of N-Desmethyl thalassospiramide C covalent inhibitor (

. B. Crystal structure of the complex of N-Desmethyl thalassospiramide C covalent inhibitor ( ) bound to CtsK (

) bound to CtsK ( ; PDB ID: 6HGY) [100], [157]. In PyMOL, the crystal structure of CtsB (

; PDB ID: 6HGY) [100], [157]. In PyMOL, the crystal structure of CtsB ( ; PDB ID: 1CSB) was aligned to the structure of CtsK to compare the localization of the residues involved in interactions with the inhibitor [101], [107]. The parts of CtsK and B with different folds are

; PDB ID: 1CSB) was aligned to the structure of CtsK to compare the localization of the residues involved in interactions with the inhibitor [101], [107]. The parts of CtsK and B with different folds are  and

and  , respectively. Dashed lines indicate possible non-covalent bonds. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

, respectively. Dashed lines indicate possible non-covalent bonds. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Structural differences between cysteine cathepsins were used for the design of novel P1 thioamide peptide inhibitors selective to CtsL [161]. The obtained peptides are non-covalent reversible mixed-type inhibitors. While the primed positions of these peptides possess Ala at the P1′, P2′, and P3′ positions, sequences for the non-primed side were designed based on substrate profiling study by Choe et al [66]. At the P1 position, similar to other human cathepsins CtsL prefers basic amino acids, but unlike CtsK, S, and B, CtsL is selective to the substrates with aromatic residues (Phe, Trp, Tyr) at P2 [61], [66]. CtsV also favors Trp and Tyr, so Phe was chosen at P2 for CtsL. At P3, CtsL prefers basic and aliphatic residues, but since basic residue is preferred at P1, an aliphatic Leu (Leu is the most preferred aliphatic according to [66]) was chosen for P3 to avoid multiple cleavage sites. At P4, CtsL shows a preference for His. The P1 position was chosen for thioamide [162], [163]. Obtained peptides μHLFRSAAAμ (RS3A) (μ − 7-methoxycoumarin-4-yl-alanine) and μHLFKSAAAμ (KS3A) were completely resistant to proteolysis by CtsV, K, and S, but cleaved by CtsL and B (μHLFKSAA↓Aμ or μHLFRSAA↓Aμ) [161]. Shorter thiopeptide (μHLFRSAμ; RS1A) was left intact by all investigated cathepsins: CtsL, V, K, S, and B. The thioamide peptides KS3A and RS3A were very good inhibitors of CtsL, with respective KI values of 0.60 ± 0.15 μM and 0.52 ± 0.12 μM. The RS1A peptide was slightly worse with a KI value of 1.11 ± 0.22 μM. The RS1A peptide exhibited a 26-fold increase in KI for CtsV (26.22 ± 8.42 μM). No significant decrease in activities of CtsB, K, and S was observed in the presence of up to 50 μM of RS1A peptide [161]. Molecular docking with all five cathepsins showed that P1 thioamide bond N—H of the RS3A and RS1A peptides can interact with catalytic His163 exclusively in CtsL. Hydrogen bond prevents His163 from efficient deprotonation Cys25 thus inhibiting the proteolytic activity [161]. Finally, the RS1A peptide was shown to be able to inhibit CtsL in human liver carcinoma HepG2 lysates (IC50 = 19 µM) [161].

A specific pH-dependent inhibitor was developed for CtsB [99]. At pH 7.2, CtsB prefers the basic residues Arg and Lys, and also Nle and Tyr at P1. At S2 CtsB possesses Glu245, so it favors the basic residues Arg, Lys, and His, as well as Trp at P2 [139]. At pH 4.6, CtsB prefers noncharged Thr and Gly residues, and the basic residue Arg at P1, while at P2, CtsB favors the substrates containing either the acidic Glu residue or hydrophobic Val. Glu245 can interact with the Glu residue and has no preference to the basic residues as at neutral pH 7.2 Glu residues are uncharged [99]. CtsB had the highest ratio of pH 7.2/pH 4.6 activities towards Z-RK-AMC and the highest ratio of pH 4.6/pH 7.2 activities towards Z-EK-AMC among the investigated dipeptide-AMC substrates (Z-RK-AMC, Z-KK-AMC, Z-KR-AMC, Z-RR-AMC, Z-EK-AMC, and Z-ER-AMC). No CtsL and V activity was detected for Z-RK-AMC at pH 7.2 or Z-EK-AMC at pH 4.6. AMC group was replaced with the acyloxymethyl ketone (AOMK) warhead to obtain the Z-RK-AOMK and Z-EK-AOMK peptide inhibitors [119], [164]. Z-RK-AOMK displayed selective inhibition of CtsB at pH 7.2 compared to pH 4.6 with KI values of 130 nM at pH 7.2 and 15,000 nM at pH 4.6. Z-EK-AOMK displayed less effective inhibition of CtsB at both pH levels with KI values of 2,300 nM and 7,900 nM at pH 7.2 and pH 4.6, respectively. At pH 7.2, Z-RK-AOMK inhibited CtsB with IC50 of 20 nM, which was more potent than CtsV, CtsS, and CtsC inhibition with respective IC50 of 440 nM, 2,200 nM, and 850 nM. CtsK and H were minimally inhibited by Z-RK-AOMK at 16 μM. Computational modeling of Z-RK-AOMK binding to CtsB showed that the P2 Arg residue of Z-RK-AOMK has a strong polar interaction with the carboxylate of Glu245 in the S2 subsite of the enzyme. In the S1 binding pocket Lys residue of the inhibitor interacts with Glu122 and Asn72 of the enzyme [139]. Z-RK-AOMK was shown to inhibit CtsB at 1 µM concentration in human neuroblastoma cells SHSY5Y [99].

There are quite a few different types of PLCP inhibitors both covalent and non-covalent [165]. Their structures located in the protease binding cleft of the proteases might provide important information for improving their selectivity. Structural analysis of the complexes and sequence alignment of different PLCPs might be employed to design selective inhibitors for other proteases.

5. Plcps engineering for industrial applications

The information about the structural features of proteases provides a basis for ligand design as well as templates for engineering of the novel enzymes. The examples of enzyme redesign include an improved thermostability, tolerance to organic solvents, protein–protein interactions, altered substrate promiscuity/specificity, enhanced enzymatic activity, and inversion of enantioselectivity [166]. The obtained engineered enzymes can be of specific use in food, pharmaceuticals, biofuels and scientific applications [167]. Multiple plant PLCPs, especially papain, bromelain, and ficin, are often implemented in distinct industries [168], such as brewing, meat softening, milk-clotting, cancer treatment, digestion and viral disorders [169], [170], [171]. Papain is one of the most commonly used proteases in food industry [172], [173]. Papain, as well as bromelain and ficin, are used to tenderize meat improving the sensory evaluation rating [174]. The application of PLCPs in the bakery industry may reduce risks of gluten intolerance since PLCPs digest allergenic gliadins [175]. In the textile industry PLCPs can be used to improve tactile behavior and wettability of wool and silk thus increasing the dye uptake [176], [177]. Papain and bromelain as the ingredients in the cosmetic products digest the protein of dead cells in the upper layer of the skin alleviating wrinkles, acne, and dry skin [178]. Bromelain can also reduce bruising and swelling of skin after cosmetic injection treatments [179], [180]. Papain is used in different formulations for chemomechanical caries removal [181], [182] while bromelain and papain gel is used for deproteinization before orthodontic bracket attachment [183]. Though intact PLCPs are applied in numbers of industries, the need for new proteases with appealing physicochemical properties are emerging and protease reengineering may be the key.

The importance of research in this area is underlined by the fact that the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Frances H. Arnold in 2018 for developing the method for a directed evolution of enzymes [184]. However, there is still no published data on PLCP redesign harnessing the directed evolution. Directed evolution is used to simulate the process of natural evolution with the gene encoding the enzyme of interest being used to generate a library of mutants. After that, the enzyme variants with required properties are selected by an appropriate high-throughput screening method [167], [185], [186]. Typically, the cycles of mutagenesis and selection are repeated for several times. Most mutations in directed evolution occur outside the catalytic cleft and affect proteolytic activity only indirectly. Moreover, after introducing several mutations, improvements in activity often reach a plateau due to epistasis or stability-threshold effects [187]. In contrast, rational design is based on mutating specific residues in the protein structure [188], [189]. Rational design is based on profound knowledge on the protein structure, function, and catalytic site. Alignment of multiple sequences and computational methods such as molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation are used to analyze the enzyme structure [190]. The redesign is often based on a template enzyme with the innate activity for the target reaction [166]. As the libraries generated by rational design are generally smaller than the libraries obtained from a directed evolution, analyzing the obtained mutants does not require extensive screening [167]. However, chemical versatility that is available for a protein engineer is limited to a generally narrow range of reaction types within a superfamily [166].

Rational design was used to stimulate the catalytic activity of ervatamin C (Erv-C), a PLCP from the plant Ervatamia coronaria [168]. Contrasted with Erv-A and Erv-B, Erv-C is highly stable in a wide range of pH (2–12), at a high temperature (70 °C) and a high concentration of chemical denaturants. Still, it possesses a significantly lower catalytic activity than Erv-A. The structures of Erv-A and Erv-C were compared to identify the mutations in the catalytic cleft that had to be introduced into Erv-C to enhance its proteolytic activity. Two single mutants (Ser32Thr and Ala67Tyr) and one double mutant of Erv-C (PDB ID: 2PNS) displayed ∼ 8 times higher catalytic efficiency than WT with no effects on the thermal stability [168], [191]. The obtained protease can be used as a biocatalyst with a potential for industrial applications.

In order to identify the amino acid residues determining PLCPs' specificity, there were several mutants designed. The papain with the Ser205Glu mutation in the S1 pocket digested Z-RR-AMC 100-fold more efficiently than WT [14]. However, mutations of PLCPs are mostly introduced into the most studied S2 subsite. The papain Ile86Leu mutant preferred branched hydrophobic residues at the P2 positions, while the Ile86Phe mutant preferred aromatic amino acids and Ile86Ala mutant demonstrated a decreased catalytic activity against the majority of the substrates (PDB ID: 3TNX) [192]. The gelatinolytic and caseinolytic activities of the mutants were reduced as well [120]. The Phe205Glu CtsS mutant had a lower affinity to the P2 hydrophobic residues and 77-fold increase in its activity towards the dipeptide RR. Adding one more mutation Gly133Ala (as in CtsB and L) promoted the digestion of RR [90]. The Glu245Gln CtsB mutant with the mutated S2 site did not digest substrates with P2 Arg in contrast to WT proteases and possessed unaltered activity towards the substrates with P2 Phe [2], [151]. Similarly, Met205 in CtsF and Ala214 in CtsL can be replaced to Glu (as in CtsB) thus introducing specificity to positively charged residues at the P2 position of the substrates. Several mutants were created to study the collagenolytic activity of CtsK. The double CtsK mutant (Tyr67Leu and Leu209Ala as in CtsL) lacked Pro specificity and collagenolytic activity [13], [146]. CtsL with the reverse mutations (Leu69Tyr and Ala214Leu) gained the ability to bind P2 Pro [147], but was not able to cleave collagen the way CtsK did [2], [193]. However, the triple CtsL mutant (Leu69Tyr, Gly164Ala, and Ala214Leu) cleaved collagen similarly to CtsK [93]. It would be also interesting to evaluate the specificity at P2 to Pro and collagenolytic activity of the relative mutants of other cathepsins: in particular, triple mutant of CtsS (Phe67Tyr, Gly160Ala, and Phe205Leu), double mutant of CtsF (Leu67Tyr and Met205Leu; CtsF already possesses Ala160), and single mutant of CtsB (Glu245Leu; CtsB already possesses Tyr75 and Ala200).

Rational design is being successfully employed to devise novel proteases with the desired specificity and improved stability. However, this method is based on the mutagenesis of the particular residues and requires identifying these residues. That is why it is so crucial to investigate structural features of the proteases and their impact in the specificity and activity of the enzyme.

6. Summary and outlook

PLCPs can perform a plethora of functions in different organisms inside and outside the cells cleaving a wide range of substrates. Some of them are highly specific for certain PLCPs, while the others can be digested by several proteases. Moreover, PLCP-mediated proteolysis is orchestrated by various parameters such as pH level, ions, GAGs, inhibitors, and cognate prodomains. This flexible regulation is involved in maintaining cell homeostasis and any shift or disruption of this network may lead to various disorders, such as cancer. Thus, it is utterly important to reveal the features defining the specificity of PLCPs. Since the catalytic cleavage takes place inside the binding cleft, the amino acid residues that constitute the cleft are the key determinants of PLCPs specificity.

Most PLCPs prefer basic amino acid residues at the P1 position which can interact with the negatively charged amino acid of the S1 position and with the oxyanion hole. CtsS is not an exception from this rule but unlike the other cysteine cathepsins, it possesses Arg in its S1 subsite. This can be useful for development of the selective inhibitors even though the phenyl ring of the vinyl sulfone inhibitor creates a hydrophobic bond with the methylene of the Arg [140]. This might result from the specific local pKa of the residue; however, more evidence is needed. S2 binding pocket of PLCPs is generally hydrophobic favoring the interactions with substrates and inhibitors with a hydrophobic P2 residue. CtsK possesses a unique specificity to P2 Pro, which determines its ability to cleave the intact collagen triple helices. The artificial endoprotease CtsCΔEx can also accommodate P2 Pro [44]. Carboxypeptidases CtsB and CtsX are also distinct from other cathepsins since they possess charged amino acids at the S2 position. This difference determined the choice of positively charged amino acid residues at the P1 and P2 positions in the selective probe for CtsB Z-RR-AMC [67]. The specificity of the S3 binding pocket is very low. Most PLCPs can efficiently digest substrates with hydrophobic P3 but some of them expose charged amino acids as well. Some human cysteine cathepsins contain negatively charged (CtsF and L) or positively charged (CtsS and V) amino acids that can also be used in drug design. The primed side of PLCPs is formed by highly conservative Trp which may be involved in stacking interactions. However, CtsB, L, S, and V can accommodate hydrophilic amino acid residues at the S1′ binding site. The S2′ binding site in endopeptidases is hydrophobic while carboxypeptidases CtsB and X contain the positively charged His residues interacting with the C-terminal carboxylic group of the substrate. The existing data has already revealed several distinct structural features in the primed side of PLCPs. However, there are much less studies on this side of binding cleft than on the non-primed side [2]. Thus, the artificial substrates, probes, and inhibitors are mainly designed to interact with the non-primed side of the binding cleft. Still, designing elongated molecules may increase strength of binding.

Currently, only a few cysteine proteases were successfully redesigned. Still, enzyme engineering is employed mainly for increasing their stability. Most changes introduced into the structure of redesigned proteases are located outside the active site. This can be accounted for the overall focus on ensuring stability and high catalytic efficiency rather than specificity since proteases are mostly used in industry. The data on PLCPs structural features discussed in this review may prove useful for the protease engineering. Scrutinizing more PLCP structures could also provide valuable data that can further serve as a basis for the de novo synthesis of proteases.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Anastasiia I. Petushkova: Writing – original draft, Visualization. Lyudmila V. Savvateeva: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Andrey A. Zamyatnin: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by Russian Science Foundation (№ 22-25-00648).

References

- 1.Rawlings N.D., Barrett A.J., Thomas P.D., Huang X., Bateman A., Finn R.D. The MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors in 2017 and a comparison with peptidases in the PANTHER database. Nucl Acids Res. 2018;46:D624–D632. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turk V., Stoka V., Vasiljeva O., Renko M., Sun T., Turk B., et al. Cysteine cathepsins: from structure, function and regulation to new frontiers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1824:68–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richau K.H., Kaschani F., Verdoes M., Pansuriya T.C., Niessen S., Stüber K., et al. Subclassification and biochemical analysis of plant papain-like cysteine proteases displays subfamily-specific characteristics. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:1583–1599. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.194001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiederanders B., Kaulmann G., Schilling K. Functions of propeptide parts in cysteine proteases. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2003;4:309–326. doi: 10.2174/1389203033487081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan A.R., James M.N.G. Molecular mechanisms for the conversion of zymogens to active proteolytic enzymes. Protein Sci. 1998;7:815–836. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lampl N., Alkan N., Davydov O., Fluhr R. Set-point control of RD21 protease activity by AtSerpin1 controls cell death in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2013;74:498–510. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Linde K., Hemetsberger C., Kastner C., Kaschani F., van der Hoorn R.A.L., Kumlehn J., et al. A maize cystatin suppresses host immunity by inhibiting apoplastic cysteine proteases. Plant Cell. 2012;24:1285–1300. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.093732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novinec M., Lenarčič B. Papain-like peptidases: structure, function, and evolution. Biomol Concepts. 2013;4:287–308. doi: 10.1515/bmc-2012-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Misas-Villamil J.C., van der Hoorn R.A.L., Doehlemann G. Papain-like cysteine proteases as hubs in plant immunity. New Phytol. 2016;212:902–907. doi: 10.1111/nph.14117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Souza D.P., Freitas C.D.T., Pereira D.A., Nogueira F.C., Silva F.D.A., Salas C.E., et al. Laticifer proteins play a defensive role against hemibiotrophic and necrotrophic phytopathogens. Planta. 2011;234:183–193. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rehm F.B.H., Jackson M.A., De Geyter E., Yap K., Gilding E.K., Durek T., et al. Papain-like cysteine proteases prepare plant cyclic peptide precursors for cyclization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:7831–7836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901807116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnelly S., Dalton J.P., Robinson M.W. How pathogen-derived cysteine proteases modulate host immune responses. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;712:192–207. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8414-2_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stack C., Dalton J.P., Robinson M.W. The phylogeny, structure and function of trematode cysteine proteases, with particular emphasis on the Fasciola hepatica cathepsin L family. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;712:116–135. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8414-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loukas A., Selzer P.M., Maizels R.M. Characterisation of Tc-cpl-1, a cathepsin L-like cysteine protease from Toxocara canis infective larvae. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;92:275–289. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(97)00245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ettari R., Previti S., Tamborini L., Cullia G., Grasso S., Zappalà M. The Inhibition of Cysteine Proteases Rhodesain and TbCatB: A Valuable Approach to Treat Human African Trypanosomiasis. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2016;16:1374–1391. doi: 10.2174/1389557515666160509125243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ettari R., Previti S., Di Chio C., Zappalà M. Falcipain-2 and Falcipain-3 Inhibitors as Promising Antimalarial Agents. Curr Med Chem. 2021;28:3010–3031. doi: 10.2174/0929867327666200730215316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]