Abstract

Priapism is a rare presenting feature of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in male patients. Treatment aims to relieve symptoms and to prevent erectile dysfunction. Several treatment modalities exist, however no standard treatment is recommended. We evaluated literature concerning different treatment approaches and evaluate the value of leukapheresis in treatment of priapism. The literature search resulted in 57 included articles, consisting of 53 studied patients. Patients had a mean age of 25.3 years, average time from onset to presentation at the hospital was 2 days, and mean white blood cell (WBC) count was 344 × 109/L. Most patients (67.9%) were treated with a combined approach (different modalities were radiological, urological, and oncological treatment). Twelve patients, with a mean WBC count of 365 × 109/L, received leukapheresis. Only two of them reported erectile dysfunction after treatment. Priapism is an urological emergency requiring urgent multidisciplinary treatment. We highlight the importance of local urological therapy combined with systemic therapy for CML. Therapeutic leukapheresis should be applied when available and with no other contraindications.

Keywords: chronic myeloid leukemia, hyperleukocytosis, leukapheresis, leukostasis, priapism

1. INTRODUCTION

Priapism as presenting feature of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is rare, approximately 1%–2% in all male cases of CML [1]. Priapism is an urological emergency characterized by full or partial penile erection, lasting more than 4 h and unrelated to sexual stimulation.

Two main types of priapism can be distinguished: ischemic (low flow) and non‐ischemic (high flow) priapism, both with their own appropriate management. Ischemic priapism is a type of compartment syndrome with reduced intracavernous blood flow, leading to stasis, acidosis, and hypoxia [1]. If untreated, it can lead to irreversible damage and fibrosis, resulting in erectile dysfunction (ED). Non‐ischemic priapism is due to unregulated cavernous flow, most commonly caused by trauma to penis or perineum. This results in increased arterial flow that overwhelms venous outflow, leading to stasis of oxygenated blood. This makes irreversible damage or fibrosis rare [1].

In ischemic priapism cases, most are idiopathic; however, 20% is caused by diseases such as sickle cell disease, CML, acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and polycythemia vera [2].

Ischemic priapism results from sludging of blood within the corpora, which results in ischemia and smooth muscle hypoxia leading to pain. In CML patients, hyperleukocytosis is considered to be the cause of sludging, especially when the white blood cell (WBC) count exceeds 200 × 109/L [1]. First, high leukocyte levels and aggregation in corpora cavernosa lead to vascular obstruction of the dorsal penile veins, which result in vascular stasis and reduced venous outflow. Venous congestion in the corpora is also a result of compressed intra‐abdominal veins due to splenomegaly. Additionally, infiltration of the sacral nerves and central nerve system with leukemic cells also contribute to priapism in CML [3].

To our knowledge, there is no standard treatment recommended for leukemic priapism and evidence for different approaches derived from case reports and small case series. We describe a case of a young male presenting with priapism as a presenting feature of CML. Furthermore, we have examined the evidence for different treatment modalities and evaluate the value of leukapheresis in management of leukemic priapism.

2. CASE DEFINITION

A 27‐year‐old previously healthy male presented to the emergency department with painful priapism lasting 6 h at time of presentation. He stated that during the past 4 months, he had been experiencing numerous involuntary, prolonged painful erections, without sexual stimulus. There was no history of trauma, medication use, fever, or weight loss. The patient reported progressive fatigue over the past few months. Upon presentation, the patient had a fever of 38.6°C and tachycardia of 130 bpm with normal blood pressure. The physical examination revealed a palpable spleen over 10 cm below the left costal margin, while lymphadenopathy or hepatomegaly was not present. The penis was erect and tender with venous engorgement. Laboratory findings showed hemoglobin (Hb) of 4.1 mmol/L (6.6 g/dl), WBC count of 502 × 109/L, and platelet count of 164 × 109/L. A peripheral blood smear showed immature leukocytes in various stages of differentiation (blast cells 7%, promyelocytes 9%, myelocytes 18%, metamyelocytes 3%, and neutrophils 51%), no platelet clumps were seen. Bone marrow aspiration showed hyperplasia of the myeloid cells without blast increase, correlating to chronic phase of CML. The SOKAL‐score was 1.26, indicating high risk [4]. Initial management of the priapism done by cavernosal aspiration achieved full detumescence. At the same time, the patient started with leukapheresis and hydroxycarbamide 3 g daily. Hyperhydration was started with rasburicase to prevent tumor‐lysis syndrome. Fever was treated with intravenously antibiotics, second‐generation cephalosporins. A total of three leukapheresis sessions were needed. Detection of a breakpoint cluster region‐Abelson (BCR‐ABL) major fusion transcript confirmed the diagnosis of CML presenting with priapism, and treatment with Imatinib was started. There was no recurrence of priapism. He tolerated treatment well and without further complications, he was subsequently discharged home with a WBC count of 79 × 109/L. Patient was a poor responder to Imatinib and was subsequently switched to Dasatinib. After start of Dasatinib, patient complained of brain fog and concentration problems and therefore switched to Bosutinib. At 1‐year of follow‐up, BCR‐ABL was decreased below 0.1% and Bosutinib was continued. Patient reported no complaints of sexual dysfunction.

3. METHOD

3.1. Study design

We analyzed literature describing treatment of priapism in CML. The search was restricted to literature including any treatment of leukemic priapism in patients with CML. Only articles written in English or Dutch with full‐text availability were included. In addition, bibliographies of relevant systematic reviews or overview articles identified during the search were also reviewed to identify additional relevant studies.

3.2. Information sources and search

The PubMed (Medline Ovid) database was searched, and the latest comprehensive search was conducted on January 5, 2022.

The search terms used for searching the database were “Chronic Myeloid Leukemia,” “Chronic myelocytic leukemia,” “BCR ABL positive,” and “Priapism.” The search strategy and queries were assessed by a biomedical information specialist for the PubMed database (see Table S1, for the complete syntaxes).

3.3. Study selection

Two researchers (Marleen van der Velde and Sanne Tiellemans) independently screened all identified studies for inclusion based on title and abstract, by using Rayyan QCRI [5]. Of the selected studies, the full text was assessed by the same investigators. Any conflicting results in the selection process were discussed until consensus was reached. We decided to only include studies performed after January 1, 2000, because with the advent of the tyrosin kinase inhibitors (TKIs), the treatment of CML changed drastically. All studies which included any sort of treatment of priapism in CML were included.

3.4. Data collection

From each included article we extracted, if available, the following data: authors, year, and journal of publication. When the article was a case report, we included the following patient characteristics: age, time to first presentation, WBC count, time to treatment, known history of CML, treatment strategy including the use of leukapheresis, resolution, and ED. We analyzed these data using descriptive statistics of the observed data. Continuous data are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and first–third quartile, and nominal data are presented as number and percentage. All data were analyzed using the software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 25 (IBM Corp., NY, USA). For articles consisting of patients cohort or systematic reviews, a short summary of the objective and results was made. Data were extracted by two researchers (Sanne Tiellemans and Marleen van der Velde).

3.5. Data analysis

The primary objective was to provide an overview of different approaches in treating priapism caused by hyperviscosity and evaluate the value of leukapheresis as treatment modality. Treatments were categorized based on oncological or urological approach, and whether there was a stepped‐up approach. We also reported if resolution was reached and whether ED was present after treatment.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Different approaches in management of ischemic priapism

Treatment modalities in low flow priapism due to hyperviscosity consist of radiological, urological, and oncological management. Radiological management of priapism consists of localized radiation therapy, most often in fractionated doses to the penis to resolve priapism. Irradiation to the spleen to reduce the venous outflow obstruction caused by splenomegaly is another option in treating priapism caused by CML [6]. Possible complications of penile irradiation consists of urethra fibrosis causing lower urinary tract symptoms and ED due to reduced penile blood flow. In management of priapism caused by CML, few case reports mention using irradiation as treatment modality. Hematological disorders tend to be more chemo‐ and radiation sensitive; however, there is no in‐depth literature available evaluating the optimal dose and duration or value of radiation therapy in malignant priapism [7].

The two main treatment strategies are therefore urological and oncological treatment. The main goal of treatment is to pursue detumescence as quickly as possible, to prevent irreversible damage and fibrosis leading to problems with erectile function or future episodes of persistent and prolonged priapism (stuttering priapism). The modalities of urological management consist of aspiration, intracavernous sympathomimetics, shunts, and penile prothesis [1, 8]. Initial urological management may include aspiration (with or without irrigation) or intracavernous injection of sympathomimetics. Unilateral aspiration is sufficient as both corpora are interconnected, and it has a success rate of approximately 30% [1]. Evacuation of blood by corporal aspiration relieves the compartment syndrome of the penis [9]. If priapism persists after aspiration, intracavernous injection with phenylephrine or epinephrine can be performed combined with irrigation, this has a success rate of 43%–81%. A higher resolution rate is achieved after injection of a sympathomimetic agent, and this lowers the risk of post‐priapism ED [9]. Only when these two techniques fail, surgical shunts should be considered. Extended durations of ischemic priapism are less likely to resolve with solely injection/irrigation therapy alone, in which immediate surgical shunting must be considered. The goal of these surgical procedures are to create a channel allowing the deoxygenated blood to drain from the corpora cavernosa. Four types of shunts are used in daily practice: percutaneous distal, open distal, open proximal, and vein anastomoses shunts. First choice of shunt procedure is the percutaneous distal shunt (Winter's/corporoglanular shunt), wherein a large needle or scalpel is inserted percutaneously through the glans. The shunts will close with time, but it may lead to ED.

Oncological management includes cytoreductive therapy with high‐dose hydroxycarbamide and when BCR‐ABL positive followed by the induction of TKIs. Initial management is sometimes combined with leukapheresis to reduce hyperviscosity, but its popularity has decreased with the introduction of TKIs [7, 10]. Leukapheresis is a blood filtrating process that separates and removes WBC from the circulated blood, which reduces the WBC count up to 60% [11]. Due to the lowering of WBC, this procedure reduces the degree of tissue infiltration and hyperviscosity caused by hyperleukocytosis and leukostasis, relieving acute symptoms such as priapism. It should be considered especially in the initial phases of treatment, where the maximum effect of cytoreductive therapies is yet to come [6]. However, leukapheresis is not available in every setting and costs are high. Most commonly, these therapies are combined with supportive treatment with hyperhydration and allopurinol to prevent tumor‐lysis syndrome. Although only 35% of cases managed with systemic treatment alone resulted in ED, it is strongly recommended that systemic treatment of the underlying disorder should not be undertaken as single treatment for low flow priapism. Ischemic priapism is a compartment syndrome and requires direct local treatment of the penis [8].

A two‐phase algorithm is proposed by Chisick et al. [11] in order to standardize treatment in cases where priapism as presenting feature of CML is suspected. A multidisciplinary assessment is recommended with simultaneous initiation of hyperhydration, allopurinol, and cytoreductive management, next to specific ischemic priapism treatment consisting of prophylactic anticoagulants, sympathomimetic agents, and leukapheresis.

4.2. Study selection

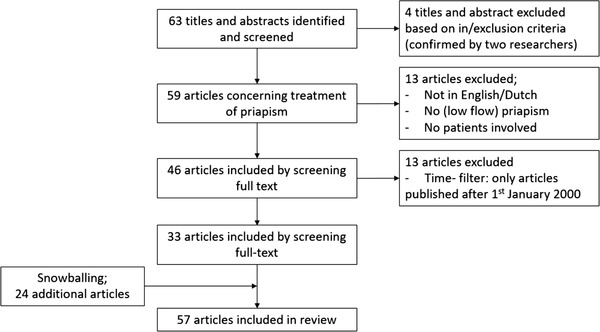

The initial search provided 63 articles with no duplicates. The screening of title and abstracts led to the selection of 59 articles concerning treatment of priapism. Following further screening of these articles, 13 articles were excluded because these were not in English or Dutch, the article did not concern (low flow) priapism, did not include patients or the full text was not available for the researchers. After applying the time filter, 33 articles were included in this review of literature. Of all 63 articles, the researchers analyzed the reference list to identify additional papers which met the inclusion criteria, 24 additional articles concerning treatment of malignant priapism were included. We evaluated a total of 57 articles, 48 case reports consisting of 53 patients, five retrospective studies, two prospective observational studies, and two reviews (Figure 1). For an overview of included articles, see Tables 1 and 2.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram for the included articles

TABLE 1.

Overview of included case reports per patient

| First author | Year of publication | Age | First presentation | WBC (×109/L) | Time to treatment | CML history | Use of leukapheresis | Radiation therapy | Management | Resolution | ED |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Only oncological treatment | |||||||||||

| Atas [12] | 2018 | 18 | Y | 215 | 5 days | N | Y | N | Oncologic: hyperhydration, allopurinol, later leukapheresis | Y, after 5 days | NS |

| Castagnetti [13] | 2008 | 9 | Y | 509 | Several days | N | Y | N | Oncologic: cytoreduction therapy, antibiotics, anticoagulants, leukapheresis | Y | NS |

| 9 | Y | 169 | NS | N | N | N | NB: stuttering priapism. Oncologic: cytoreduction therapy, anticoagulant | Y | NS | ||

| 9 | Y | 472 | 9 h | N | Y | N | Oncologic: cytoreduction therapy, antibiotics, anticoagulants, leukapheresis | Y | NS | ||

| Ergenc [14] | 2015 | 18 | Y | 100 | 72 h | N | Y | N | Oncologic: imatinib, allopurinol, hyperhydration, leukapheresis | Y | Y |

| Kumar [15] | 2017 | 19 | Y | 240 | 21 days | N | N | Y | Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, busulphan. Radiation: penile radiation | Y | NS |

| 38 | Y | 397 | 24 h | N | N | N | Oncologic: hyperhydration, busulphan | Y | N | ||

| Musa [16] | 2017 | 18 | Y | 199 | 12 days | N | N | N | Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, allopurinol | Y, after 4 weeks | Y |

| Ocheni [17] | 2010 | 30 | Y | 356 | 4 days | N | N | N | Oncologic: cyclophosphamide and hydroxycarbamide | Y, not stated when | NS |

| Veljkovic [18] | 2012 | 16 | Y | 320 | 1 day | N | Y | N | Oncologic: anticoagulant, cytoreductive chemotherapy. After no effect leukapheresis, immediate improvement. Imatinib | Y, after 13 days | NS |

| First oncological, later urological treatment | |||||||||||

| Becerra‐Pedraza [19] | 2018 | 52 | Y | 282 | 6 days | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration, irrigation. Surgery shunt. Oncologic: hyperhydration and allopurinol | NS | NS |

| Gupta [20] | 2009 | 12 | Y | 364 | 48 h | N | N | N | Oncological: hyperhydration, hydroxycarbamide. Urological: injection terbutaline | Y, 1 day | NS |

| Morano [21] | 2000 | 23 | Y | 660 | 3 days | N | Y | N | Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, leukapheresis. Urologic (started after 3 days): aspiration. After conspicuous edema → shunt surgery | Y, slight clinical improvement after puncture | Y |

| Combined treatment/unknown timeline | |||||||||||

| Gaye [22] | 2020 | 46 | Y | 526 | 48 h | N | N | N | Urologic: puncture, injection phenylephrine. Oncologic: hydration, allopurinol, hydroxycarbamide, imatinib | NS | NS |

| Hazra [23] | 2013 | 14 | Y | 227 | 24 h | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration, irrigation and phenylephrine injection. Oncologic: hyperhydration | Y, after 5 days | NS |

| Huei [24] | 2018 | 28 | Y | 294 | 2 days | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration, irrigation, injection with phenylephrine. Corporaglandula shunting. Oncologic: hyperhydration, cytarabine, hydroxycarbamide | After aspiration short detumescence, but reoccurred hours later. Following drainage: flaccid | NS |

| Mishra [25] | 2020 | 24 | Y | 207 | 5 days | N | Y | N | Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, hydration and daily leukapheresis (five sessions). Urologic: aspiration (three times), distal shunt | Y, after 7 days | Y |

| Purohit [26] | 2021 | 17 | Y | 386 | 2 days | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration and irrigation. Oncologic: (after complete detumescence) hydroxycarbamide and imatinib | Y | N |

| Sossa Melo [27] | 2021 | 47 | Y | 222 | 8 h | N | N | N | Urologic: injection, aspiration and irrigation. Distal surgical shunt. Oncologic: hydration, hydroxycarbamide and allopurinol. Dasatinib | Y | NS |

| Syarif [28] | 2021 | 27 | Y | 620 | 10 days | N | N | N | Urologic: winter procedure (shunt), aspiration and injection. Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide and allopurinol | Y | Y |

| First urological, later oncological treatment | |||||||||||

| Abd El Salam [29] | 2019 | 30 | Y, just dis‐continued treatment CML | 210 | 16 h | Y | N | N | Urologic: aspiration and irrigation with ephedrine. Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, hydration and allopurinol | Y, after aspiration | Y |

| Avci [30] | 2005 | 55 | Y | 184 | 8 h | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration and ephinephrine irrigation, shunt procedure. Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, allopurinol and hydration | Y, after shunt | NS |

| Chang [31] | 2003 | 21 | Y | 217 | NS | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration, irrigation, injection with epinephrine. Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, interferon α‐2a. Allopurinol. Hyperhydration | Y | N |

| Clark [32] | 2018 | 13 | Y | 350 | 3 days | N | Y | N | Urologic: injection with phenylephrine, three corporal irrigation, shunt surgery. Oncologic: leukapheresis, hyperhydration, hydroxycarbamide, allopurinol | N, still phallus rigidity and tenderness | NS |

| Dhanju [14] | 2019 | 18 | Y | 363 | 14 h | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration and irrigation with phenylephrine. Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, allopurinol and later imatinib | Y, after aspiration | N |

| Dhar [33] | 2019 | 52 | Y | 239 | 4 h | N | N | N | Urologic: needle aspiration, shunt surgery. Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, imatinib, allopurinol, hyperhydration | Y | N |

| Dogra [34] | 2004 | 18 | Y | 320 | 10 days | N | N | N | Oncologic: hyperhydration, allopurinol, 6‐mercapropurine. Urologic: shunt surgery | Partially | Y |

| Ervie [35] | 2015 | 22 | Y | 185 | 9 h (stuttering priapism existed for a month prior to visitation) | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration and terbutaline injection. Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, allopurinol and prednisone, later imatinib | Y | NS |

| Farhan [36] | 2015 | 35 | Y | 378 | 30 h | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration and irrigation. Oncologic: hydration, allopurinol and hydroxycarbamide and later imatinib | Y, after 5 days | NS |

| Gupta and Agrawal [37] | 2008 | 55 | Y | 420 | 2 days | N | N | N | Urologic: shunt surgery. Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide | NS | NS |

| Jameel [38] | 2009 | 21 | Y | 316 | 8 h | N | N | N | Urologic: cavernosa aspiration, irrigation, injection with epinephrine. Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, allopurinol, hyperhydration | Y | N |

| 55 | Y | 282 | 12 h | N | N | N | Urologic: cavernosa aspiration. Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, allopurinol, hyperhydration | Y | NS | ||

| Khan [39] | 2018 | 16 | Y | 615 | 11 days | N | N | N | Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, aspirin, allopurinol, hyperhydration. Urologic: aspiration and washes | Y | N |

| Manuel [40] | 2007 | 20 | Y | 708 | Developed during hospital stay | N | Y | Y | Urologic: aspiration and injection with phenylephrine. Oncologic: leukapheresis and oral hydroxycarbamide. Induction chemotherapy. Radiation: local | Y | NS |

| Minckler [41] | 2017 | 18 | N a | 588 | 6 h | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration and irrigation. Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide | Y, after aspiration | NS |

| Narendra [42] | 2011 | 11 | Y | 290 | 12 h | N | N | N | Urologic: conservative management was advised due to short duration, mild pain, and lack of ischemia. Oncologic: hydration, allopurinol, and hydroxycarbamide. Later imatinib | NS | N |

| Nerli [43] | 2016 | 19 | Y | 297 | 24 h | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration, irrigation, injection with phenylephrine. Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, imatinib, allopurinol | Y | NS |

| Rajabto [44] | 2020 | 44 | Yes | 399 | 4 days | N | N | N | Urologic: puncture, injection ephinephrine. Oncologic: hydration, allopurinol, hydroxycarbamide, imatinib | Y | Y |

| Patil [45] | 2016 | 22 | Y | 157 | 8 h | N | N | N | Urologic: ultrasound‐guided cavernosa aspiration. Oncologic: imatinib, hyperhydration | Y, after 1 month | NS |

| Ponniah [46] | 2004 | 19 | Y | 294 | 18 h | N | Y | N | Urologic: aspiration. Oncologic: cytotoxic medication, leukapheresis | Y | N |

| Qu [47] | 2019 | 18 | Y | 257 | 72 h | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration, injection with phenylephrine. Shunt surgery. Oncologic: imatinib, hyperhydration | Y, after surgery | N |

| Sachdeva [48] | 2020 | 14 | No, recurrent in 2 months | 458 | 6 days | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration and irrigation, later bilateral cavernotomy. Oncologic: hydration, allopurinol, hydroxycarbamide, imatinib | Y | Y |

| Shaeer [3] | 2015 | 21 | Y | 410 | 6 days | N | Y | N | Urologic: aspiration, irrigation, sildenafil citrate. Oncologic: imatinib, leukapheresis, | NS | N |

| Swapna [49] | 2017 | 18 | Y | 144 | 4 days | N | Y | Y | Urologic: aspiration, irrigation, injection with phenylephrine. Radiation: local. Oncologic: leukapheresis, hydroxycarbamide, allopurinol. Initiation of imatinib | Y, after leukapheresis | NS |

| Thakur [50] | 2019 | 15 | Y | 135 | 2 days | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration, irrigation, phenylephrine injection, distal shunt procedure, later proximal corporospongiosal shunt. Oncologic: hydration, allopurinol, imatinib | Y, after two days | NS |

| Ullah [51] | 2018 | 22 | Y | 219 | 4 days | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration and irrigation. Oncologic: hydroxycarbamide, interferon α‐2a and allopurinol with hydration | Y, after urologic treatment | NS |

| Only urological treatment | |||||||||||

| Almaeena [52] | 2016 | 36 | Y | 231 | NS | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration b | Y | NS |

| Ammouri [53] | 2019 | 25 | Y | 501 | 16 h | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration | Y | NS |

| Htun [54] | 2008 | 21 | Y | 619 | 72 h | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration, shunt surgery | Y, partial tumescence | NS |

| Ocheni [17] | 2010 | 36 | Y | 456 | 34 h | N | N | N | Urologic: aspiration | Y | NS |

| Sareen [55] | 2018 | 17 | Y | 377 | Recent onset | N | N | N | Urologic: injection of phenylephrine, aspiration | Y | NS |

| Sun [56] | 2019 | 27 | N c | 450 | 9 h | Y d | N | N | Urologic: aspiration, injection with phenylephrine | NS | NS |

| Tazi [57] | 2009 | 33 | Y | 400 | 22 h | N | N | N | Urological: aspiration, irrigation, injection with epinephrine | Y, “later” | N |

Abbreviations: ED, erectile dysfunction; N, no; NA, not applicable; NS, not specified; WBC, white blood cells; Y, yes.

Third episode requiring ED‐visit (prior treatment: pseudoephedrine, icepack with result, second: terbutaline without success → aspiration and irrigation).

Aspiration was performed in other hospital before referral.

Two episodes in period of 2 months.

Diagnosed at age of 19 years.

TABLE 2.

Overview of case reports with multiple patients and reviews

| First author | Year of publication | |

|---|---|---|

| Ali [6] | 2021 | Systematic review about the characteristics and management options of priapism caused by CML. Sixty‐eight articles, concerning 102 patients with a mean age of 27.4 years. Nearly a quarter of the patients developed permanent ED. Conservative and medical therapy without urological intervention is less likely to be sufficient. Starting treatment of CML to decrease the high WBC count might accelerate the resolution of the priapism and sometimes is needed for a complete resolution. |

| Chowdhury [58] | 2020 | Retrospective study to evaluate the need of urologic intervention in priapism in CML patients. Among 12 patients, six were diagnosed as priapism with CML. Mean age was 46.7 years, five patients were newly diagnosed with CML. Of the six patients, five were managed with minimal invasive procedure (injection, aspiration, irrigation), and only one patient needed proximal shunt. After emergency management, all patients were referred to hematologist for definitive management of CML. |

| Ekeke [59] | 2015 | Prospective study to evaluate management of priapism in adult men. Sixteen patients had hematological disorders, of which two patients were diagnosed with CML. Precise treatment modalities in these CML patients are not stated. |

| Jandial [60] | 2019 | Retrospective study of outcome of priapism in CML patients. Twenty‐three patients (1.7%) of a total of 1350 CML patients had priapism at diagnosis. Median age was 24 years (range 13–50 years). Median duration of priapism was 8 days (range 2–25 days). Baseline median leukocyte count was 285 × 109/L. All patients received cytoreductive therapy (hydroxycarbamide and imatinib), 21 patients underwent penile aspiration, 13 therapeutic leukapheresis, and eight patients distal shunt surgery. ED could be assessed in 14 patients on follow‐up. The occurrence and severity of ED was unaffected by leukapheresis or shunt surgery. Despite favorable response to treatment, long duration of symptoms and hyperleukocytosis probably contributed to ischemic priapism and severe ED in the study cohort. |

| Kumar and Garg [61] | 2018 | Review of outcomes of patients with ischemic priapism malignant and non‐malignant. Twenty‐four patients presented with priapism due to CML. Average age at presentation was 27.50 years (SD 6.45), with a mean duration of existing priapism 4.25 days (SD 1.42). No oncological treatment is described. Six patients underwent therapeutic aspiration and irrigation with sympathomimetics, 12 received a distal shunt, and six patients received a proximal shunt. Of these patients, eight had successful detumescence. |

| Kurosawa [62] | 2015 | Retrospective cohort concerning 256 children aged less than 20 years, with diagnosis of CML. Four patients experienced priapism. Three of four patients underwent therapeutic aspiration (with or without irrigation) and two of these underwent leukapheresis. Two patients may have been left with ED, despite undergoing treatment with imatinib and hydroxycarbamide, as well as leukapheresis and aspiration or irrigation. |

| Nabi [63] | 2000 | Seven patients, aged 8–13 years, time to treatment 2–5 days. Therapy with cavernoso‐spongosal shunts, antileukemic chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Successful detumescence achieved (mean after 2 days) in all cases with transglandular corpora spongiosum (Winter) shunts and hydroxycarbamide and allopurinol, with one case requiring local radiotherapy. None of patients was potent on follow‐up. |

| Pal [64] | 2015 | Prospective, observational study. Nineteen patients presenting with priapism. In one patient, CML was the inducing cause of priapism. No oncological treatment is described, further details of treatment of priapism in this patient is not specifically specified. |

| Tendulkar [65] | 2017 | Retrospectively leukapheresis carried out over 4 years, in patients with leukocyte count >100 × 109 and with symptoms of leukostasis. With a mean age of 34 years. Mean initial leukocyte count 312, which reduced to 208 at the completion of all leukapheresis sessions. On average 1.6 sessions were needed. |

Abbreviations: CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; ED, erectile dysfunction; SD, standard deviation; WBC, white blood cell.

4.3. Overview of evidence concerning different treatment modalities

4.3.1. Case reports

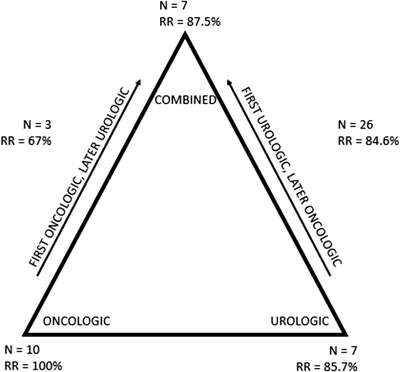

The 48 case reports showed a total of 53 cases describing priapism in CML patients (Table 3 and Figure 2). The youngest patient was 9 years old and the oldest patient was 55 years old (mean age 25.3, SD 12.7). Most patients had priapism as a first presentation of CML (n = 50, 94.3%). Two patients had a history of CML, one of these patients developed priapism promptly after discontinuation of CML treatment. The mean duration of symptoms before presentation was 2 days, and mean WBC count was 344 × 109/L (SD 147). In most patients, platelet count was in normal range (n = 23, 43.4%). Fifteen of the included patients (28%) showed thrombocytosis, ranging from 470 to 1235 × 109/L. Treatment modalities included medications, aspiration, and irrigation to corpora cavernosa, surgical shunts, radiotherapy, and leukapheresis. Most patients received a combination of treatment modalities (n = 36, 67.9%). Urological management of priapism by penile aspiration (and irrigation) was used in 41 patients (77.4%), and 14 patients underwent shunt surgery (26.4%). Three patients received penile radiation therapy (5.7%). Oncological management by hyperhydration in combination with hydroxycarbamide was started in 43 patients (81.1%) and chemotherapeutic methods (TKI, chemotherapy) were used in 30 patients (56.6%). In a minority of the patients, leukapheresis was used (n = 12, 22.6%). A majority of the patients had resolution of priapism after treatment (n = 45, 84.9%). Presence of ED was often not reported, resulting in 60% missing data. Eight (15.1%) patients were reported to experience ED at follow‐up.

TABLE 3.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes of included patients, totals

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| No. of patients studied | 53 |

| Age (year), mean ± SD | 25.3 ± 12.7 |

| First presentation, yes | 50 (94.3%) |

| History of CML, yes | 2 (3.8%) |

| Average duration of symptoms (days), median (Q1–Q3) (missing 11%) | 2 (0.58–4.0) |

| WBC count, ×109/L (mean ± SD) | 344 ± 147 |

| Platelet count, ×109/L, yes (missing 19%) | |

| <150 | 5 (9.4%) |

| 150–450 | 23 (43.4%) |

| >450 | 15 (28%) |

| Treatment received | |

| Combined | 36 (67.9%) |

| Unknown timeline/simultaneously | 7 (13.2%) |

| First urological | 26 (49.1%) |

| First oncological | 3 (5.7%) |

| Radiation | 3 (5.7%) |

| Urological | |

| Penile aspiration ± (alpha adrenergic agonist) irrigation | 41 (77.4%) |

| Shunt (distal/proximal) | 14 (26.4%) |

| Oncological | |

| Hyperhydration + allopurinol, hydroxycarbamide | 43 (81.1%) |

| Chemotherapeutic methods (chemo, TKI) | 30 (56.6%) |

| Leukapheresis | 12 (22.6%) |

| Resolution, yes (missing 11%) | 45 (84.9%) |

| Erectile dysfunction, yes (missing 60%) | 8 (15.1%) |

Note: Numbers (% of total number patients) unless otherwise specified. Missing data when >10% is mentioned.

Abbreviations: CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; Q1, quartile 1; Q3, quartile 3; SD, standard deviation; TKI, tyrosin kinase inhibitor; WBC, white blood cells.

FIGURE 2.

Different treatment modalities (N: number of patients). RR: response rate for achieving resolution

The case reports were divided by treatment strategy to compare characteristics and outcomes (Table 4). In seven reports, priapism was treated with only oncological treatment modalities [12, 13, 15, 66–18]. This subgroup consisted of 10 patients, with a median age of 18 years, presenting with priapism after a median time of onset of 3.5 days (Q1–Q3 1–10) and a median WBC count of 280 × 109/L. Treatment consisted of hyperhydration and cytoreductive therapy. In five cases, leukapheresis was used [12, 13, 18, 66]. Penile radiation therapy was used in one case report [67]. All patients reached detumescence; however, time to resolution was reported in four cases to cost 5 days–4 weeks. Three patients reported ED, and of the other seven patients this was not reported.

TABLE 4.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes of included patients, divided by treatment strategies

| Oncologic | First oncologic, later urologic | Combined/unknown timeline | First urologic, later oncologic | Urologic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author | Atas, Castagnetti (n = 3), Ergenc, Kumar (n = 2), Musa, Ocheni, Veljkovic | Becerra, Gupta, Morano | Gaye, Hazra, Huei, Misha, Purohit Syarif, Sossa Mel | Abd El Salam, Avci, Chang, Clark, Dhar, Dogra, Ervie, Farhan, Gupta and Agrawal, Jameel (n = 2), Khan, Manuel, Minckler, Narendra, Nerli, Rajabto, Patil, Ponniah, Qu, Sachdeva, Shaeer, Singh Dhanjum Swapna, Thakur, Ullah | Almeena, Ammouri, Htun, Ocheni, Sareen, Sun, Tazi |

| No. of patients studied | 10 | 3 | 7 | 26 | 7 |

| Age (years) | 18 (9.0–21.8) | 23 (12–NA) | 27 (17–46) | 20.5 (18–31) | 27 (21–36) |

| WBC count, ×109/L | 280 (192–416) | 364 (282–NA) | 354 ± 163 | 295 (215–401) | 450 (377–501) |

| Time to treatment (days) | 3.5 (1–10) | 3 (2–NA) | 2 (1–5) | 1 (0.38–4.0) | 0.92 (0.51–2.21) |

| Resolution, yes | 10 (100%) |

2 (67%) NB: 33% missing |

6 (87.5%) NB: 14% missing |

22 (84.6%) NB: 12% missing |

6 (85.7%) NB: 14% missing |

| Erectile dysfunction, yes |

3 (30%) NB: 70% missing |

0 (0%) NB: 67% missing |

2 (28.6.%) NB: 57% missing |

4 (15.4%) NB: 50% missing |

0 (14.3%) NB: 86% missing |

Note: Numbers (% of total number patients) unless otherwise specified. Missing data when >10% is mentioned. Parameters are presented as mean ± standard deviation when normally distributed, or as mean (Quartile 1–Quartile 3) when not normal distributed.

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; WBC, white blood cells.

Urological treatment alone was chosen in seven case reports [17, 52–57]. Seven patients with median age of 27 years received penile aspiration and some subsequently received penile injection with epinephrine. One patient needed shunt surgery. Six patients achieved detumescence, and in the other patient this was not reported. The presence of ED was only presented for one patient, and he did not experience any disfunction [57].

In a majority of the case reports, a combined treatment was chosen. In three reports, treatment was started with oncological management, consisting of hyperhydration and allopurinol, with the addition of hydroxycarbamide in one case, and use of leukapheresis in another case [20, 21]. In these cases, subsequently urological treatment modalities were introduced, consisting of aspiration and irrigation in all three reports, after which shunt surgery was needed for two patients [19, 21]. Median age was 23 years with a median time to treatment of 3 days. Mean WBC count was 364 × 109/L. Resolution of priapism was reported in two patients, and in the other patient this was not reported. One patient reported no ED; however, data of the other two patients were missing.

In seven reports, a combined approach was chosen, but the specific timeframe of induction of these therapies was not specified in all reports [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. All used penile aspiration, in five patients subsequently followed by injection with phenylephrine. Four patients underwent shunt surgery [25, 27, 28, 68, 69]. Oncological management consisted of hyperhydration and cytoreductive therapy in all cases, except one [23]. One case reported the use of leukapheresis, in which five sessions were needed [25]. In these reports, median age was 27 years with median WBC count of 354 × 109/L. Time to presentation was relatively short (median 2 days), with only one case presenting after 10 days of complaints [28]. Resolution of priapism was reported in six reports (87.5%), and ED was reported in three cases with two patients suffering from ED.

Of the combined treatment modalities, primary urological treatment and later introducing oncological treatment is most often described [3, 29–41, 43, 45–42, 44, 47, 48] [14, 51]. All patients received penile aspiration except three. Narendra et al. reported that urological consultation was performed, but due to short duration of priapism with mild pain and lack of ischemia conservative management was advised. In Dogra et al. [34] and Gupta et al. [37], shunt surgery was directly performed without penile aspiration as first step. In these cases, time to treatment consisted of, respectively, 2 and 10 days, with WBC in higher ranges, 320 × 109 and 420 × 109/L. A total of seven patients received shunt surgery, five after unsuccessful detumescence after penile aspiration and injection [30, 32, 33, 47, 50]. Two patients were treated with a third modality and received penile radiation therapy [40, 49]. Oncological management consisted of hyperhydration and cytoreductive therapy for all patients. Some case reports reported start of treatment with chemotherapy or TKI when diagnosis of CML was established. Five cases used leukapheresis, the amount of sessions performed is not reported [3, 32, 40, 46, 49]. In 85% of the patients, detumescence was reached after treatment, 15.4% (n = 4) reported ED.

A total of 11 reports used leukapheresis in treatment of the hyperviscosity causing priapism, consisting of 12 patients (Table 5). Eight case reports used leukapheresis in a combined treatment modality with urological interventions [25, 30, 32, 40]. Three reports used only an oncological approach [12, 13, 18]. The mean WBC count was 365 × 109/L (SD ±4.7), and median time to treatment was 3 days (Q1–Q3 1–5). Ten patients reached detumescence after treatment, one patient experienced still phallus rigidity and tenderness after treatment, and for one patient this was not reported [3, 32].

TABLE 5.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes of included patients which received leukapheresis

| Oncologic | |

|---|---|

| First author | Atas, Avci, Castagnetti (n = 2), Clark, Mishra, Manuel, Morano, Ponniah, Shaeer, Swapna, Veljkovic |

| No. of patients studied | 12 |

| Age (years) | 17.3 (±4.7) |

| WBC count, ×109/L | 365 (±193) |

| Time to treatment in days | 3 (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) |

| Resolution, yes |

10 (83.3%) NB: 8.3% missing |

| Erectile dysfunction, yes |

2 (16.7%) NB: 58% missing |

Note: Numbers (% of total number patients) unless otherwise specified. Parameters are presented as mean ± standard deviation when normally distributed, or as mean (Quartile 1–Quartile 3) when not normal distributed.

4.4. Observational studies and reviews

Additionally, we included five retrospective studies, two prospective observational studies and two reviews concerning treatment of malignant priapism (Table 2). Two studies evaluated urological management in malignant priapism. In Chowdhury et al. [58], the need of urological interventions for priapism in CML patients was evaluated. Five of six patients managed full detumescence with solely minimal invasive urological management (injection, aspiration, irrigation) and just one patient ultimately needed shunt surgery. In Kumar et al. [61], outcomes of urological management resulted in a successful detumescence in eight out of 24 patients (33%, six patients aspiration and irrigation, 18 shunt surgery).

In Kurosawa et al. [62], three of four patients underwent therapeutic aspiration, with two additionally followed by leukapheresis. Despite combination of urological and oncological management, these patients were left with ED. The high incidence rates of ED after experiencing priapism are further demonstrated in a retrospective cohort of Nabi and Dogra [63], consisting of seven patients. Therapy with shunt surgery, antileukemic therapy, and radiotherapy resulted in successful detumescence in all patients (mean duration of 2 days); however, all patients experienced ED at follow‐up.

The outcomes of priapism in CML patients were studied in a retrospective cohort by Jandial et al. [60], 23 patients had priapism at diagnosis. All patients received cytoreductive therapy (hydroxycarbamide and Imatinib), additionally 21 patients underwent aspiration, 13 patients therapeutic leukapheresis, and eight patients shunt surgery. ED could be assessed in 14 patients at follow‐up, occurrence and severity of ED were unaffected by leukapheresis or shunt surgery. In a study by Tendulkar et al. [65], leukapheresis was found to be adequate in lowering leukocyte count, with an average of 1.6 sessions needed. Despite the favorable response in Jandial et al., long duration of symptoms and high leukocyte counts may have contributed to ischemic priapism and severe ED.

In a recently published systematic review about characteristics and management options of priapism caused by CML by Ali et al. [6], 102 patients were evaluated. Nearly, a quarter of these patients developed permanent ED. They state that conservative and medical therapy without urological intervention is less likely to be sufficient; however, treating CML to decrease the WBC may accelerate resolution and is therefore advised.

In two prospective observational studies, management of priapism in CML was evaluated [59, 64]. However, specific treatment modalities were not stated in these reports.

5. DISCUSSION

Priapism in CML is an urological emergency and it must be treated promptly to rapidly restore arterial inflow and venous outflow. Treatment aims to relieve symptoms and to prevent ED. When reviewing literature concerning treatment modalities of low flow priapism, three different modalities can be differentiated: radiation therapy, and oncological and urological managements. In this review, we evaluated the existing data after introduction of the TKIs concerning treatment of low flow priapism, and evaluated the value of leukapheresis.

Ischemic priapism is characterized by reduced intracavernous blood flow, and is a type of compartment syndrome leading to stasis, acidosis, and hypoxia. It is predicted if it remains untreated within 24–48 h, it can result in irreversible damage and fibrosis, leading to ED. In CML patients, the hyperleukocytosis is considered to be the cause of priapism. Hyperleukocytosis is defined as WBC >100 × 109/L and it can present clinical symptoms of hyperviscosity such as shortness of breath, central nervous system disorders, impaired kidney function, or priapism [70]. There are little data available on the correct management of priapism, especially leukemic priapism. Due to the rare occurrence and small case series, no standard guideline or treatment is recommended for leukemic priapism [1].

Treatment of CML consists of cytoreductive therapies, such as high dose hydroxycarbamide and TKIs, sometimes with addition of leukapheresis to reduce hyperviscosity. The introduction of TKIs has made CML a functionally curable chronic disease and life expectancy for the vast majority of chronic phase CML patients is “normal.” Patients with CML receiving TKI could be expected to have a survival and quality of life comparable to healthy people of their age and sex [71]. The SOKAL‐score of our patient indicated high risk CML. As described by Ciftciler and Haznedaroglu [71], in patients with higher risk disease second‐generation TKI as first‐line therapy has proven to be more beneficial in terms of early and deeper response rates. In a population‐based cohort by Geelen et al. [72], all response milestones were achieved faster in patients treated upfront with a second‐generation TKI but patients initially treated with Imatinib also reached similar levels of response. Imatinib has become a cost‐effective initial treatment for CML and is globally available, and is therefore first choice of treatment of chronic phase CML in our center. Although, treatment with TKIs is commenced immediately after confirming the diagnosis of CML, most often this is a few days after the patient presents acutely. For immediate lowering of WBC, high dose hydroxycarbamide can be initiated, and this will reduce the WBC count by up to 60% after 24–48 h [73, 74]. To further lower WBC, leukapheresis can be initiated. Leukapheresis can reduce the number of blast cells faster but the procedure alone is associated with rebound of blast cells because the removal of blast cells is not accompanied by destruction of blast cells in bone marrow, which can quickly replace the removed blast cells in peripheral circulation [75, 76, 77]. Leukapheresis can be given in conjunction with chemotherapy such as hydroxycarbamide to establish lowering of WBC as quickly as possible to prevent complications of leukostasis. The value of leukapheresis in addition to chemotherapeutic modalities is yet to be evaluated for CML, hence this paper. Literature concerning AML patients receiving both chemotherapy and leukapheresis did not show better early and long‐term survival rates [70, 78]. However, the disease course of AML and CML are not comparable. AML is a fast moving leukemia where mortality of leukostasis is 40% and occurs usually within the first few weeks of diagnosis, whether CML is most often a slowly progressive disease, which can be considered chronic with the advent of TKIs. Results of leukapheresis in AML may therefore not be applicable to CML.

An expert panel discussion and review of available data‐based guideline of treating leukemic priapism has been published by the American Urological Association, resulting in a number of recommendations [8]. The strongest recommendation is that ischemic priapism requires treatment directed at the penis primarily, by using aspiration (and irrigation) or shunt surgery. In ischemic priapism, “time is erectile tissue.” After 12 h, trabecular edema is seen, after 24 h, platelets adhere to the sinusoids, and after 48 h, necrosis and thrombi are seen. Ninety percent of men with ischemic priapism lasting more than 24 h develop ED [79]. A step‐wise management may be used, starting with penile aspiration which may be used both as a diagnostic and therapeutic measure. Aspiration may be combined with irrigation with normal saline. Aspiration with or without irrigation is successful in 24%–36% of the cases of priapism [6]. If no detumescence is achieved, intracavernous injection of sympathomimetics should be performed. When conservative measures fails, priapism can be treated with surgical methods [2, 6]. However, in malignant priapism, such as in CML, it is less frequently the only therapy of choice and was only chosen in seven case reports. All patients received aspiration and penile injection with epinephrine, only one patient needed shunt surgery, leading to a success rate of 85.7% solely based on these case reports, in contrary to the 30% success rate often reported for aspiration alone [1]. The outcome of ED is not presented in six of these reports.

Most cases chose a combined approach because urologic treatment alone does not tackle the underlying cause of the hyperleukocytosis. The primary mechanism in CML is the aggregation of leukemic cells in the corpora cavernosa and the dorsal veins of the penis, simultaneously venous congestion of corpora cavernosa and infiltration of the sacral nerves may play a role [38]. The oncological approach consists of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or leukapheresis. We found three case reports using radiation therapy as treatment modality; however, no in‐depth literature concerning this treatment is available.

The evidence of treatment with chemotherapy alone is supported by limited amount of literature. A number of case reports have reported successful use of oncological agents alone, with all patients reaching detumescence. However, time to detumescence was reported to cost 5 days–4 weeks. Two points should be considered; detumescence may be explained by the mechanism of action of the chemotherapeutic managements in which lowering of leukemic cells concentration takes time, or achieving detumescence might be the natural course of priapism rather than a true treatment success [8].

Therapeutic leukapheresis is an oncological treatment modality, which can accelerate the lowering of leukemic cells. We found 11 case series that have reported the successful use of therapeutic leukapheresis to treat priapism. Eight case reports combined this with urological interventions; in the other three reports, it was combined with only oncological management. A meta‐analysis by the American Urological Association found that three of four patients treated by leukapheresis had resolution of priapism compared to only three of 15 patients treated with chemotherapy alone [8]. Leukapheresis can rapidly reduce the number of leukocytes compared to chemotherapy to improve the microcirculation, and is reported to reduce leukocytes count up to 10%– 70% [77]. However, leukapheresis comes with high costs and requires specialized equipment, trained personnel, and need of a central venous catheter, which can cause a delay in treatment. Another disadvantage is the loss of red blood cell and platelets, so its suitability in patients with low Hb or platelets levels is limited [80]. However, we state that the disadvantages do not outweigh the benefits of leukapheresis. Leukapheresis can decrease leukocyte count rapidly in approximately 1.6 sessions, and minimize complications caused by hyperviscosity and leukocyte aggregation in microcirculations [65]. Secondly, leukapheresis could decrease the occurrence of tumor‐lysis syndrome in leukemia patients [81]. In case of hyperviscosity, we recommend to start therapeutic leukapheresis alongside systemic therapy to lower leukocytes as quickly as possible. In waiting time for the leukapheresis, start of chemotherapy should not be postponed.

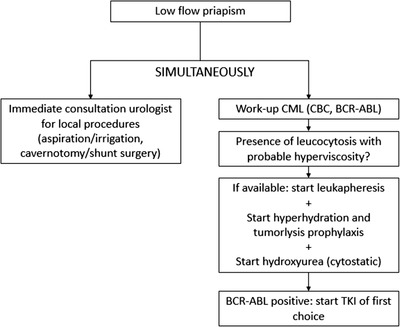

The primary goal of treating priapism in CML is to achieve detumescence as quickly as possible to preserve erectile function. Therefore, we state in accordance with the American Urological Association guideline of treating priapism and a recently published review, that treatment of CML should be a combination of oncological treatment alongside urological treatment, and neither treatment modality should be used as only treatment [8]. When presenting with malignant priapism, immediate intracavernous treatment is required and should be administered in a step‐wise fashion until detumescence is achieved; first therapeutic aspiration, followed by injection of sympathomimetics, and after multiple trials of penile injection, shunt surgery should be considered. Treating the underlying hyperviscosity caused by CML can decrease WBC and further accelerate resolution. When CML is suspected, we advise to start therapeutic leukapheresis when no other contraindications are present. Simultaneously, patients should be started on cytoreductive therapy and this should not be postponed when waiting to start leukapheresis (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Proposed workflow in low flow priapism

5.1. Limitations

Some limitations of these recommendation should be noted. Due to the relatively rare condition, literature concerning treatment and outcomes is scarce. This recommendation is therefore solely based on case reports, reviews, and expert opinions. The primary goal of treating priapism, not only in CML patients, is to resolve the erection as soon as possible to prevent ED. Detumescence, time to detumescence, and presence of ED at follow‐up are the main outcomes to evaluate different treatment modalities. However, presence of ED was not reported in 60% of the included case reports, which complicates the interpretation of the results and clinical relevance of these treatments. Furthermore, we only included articles published after 2000 because of the introduction of TKIs as a gold standard of CML treatment. With the use of TKIs, treatment results greatly differ from previously used methods, which could bias results and might not reflect the true value of leukapheresis.

6. CONCLUSION

Priapism can be the first manifestation of a previously unknown CML. Priapism is an urological emergency and when untreated can result in ED. The treatment of priapism in CML should be multidisciplinary; we highlight the importance of local urological therapy combined with systemic therapy for CML. Therapeutic leukapheresis should be applied when available and in case of no other contraindications, next to both other treatment modalities to accelerate the lowering of WBC and therefore resolution of priapism.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: Marleen van der Velde, Sanne Tiellemans, Heleen de Lil, and Laurens Nieuwenhuizen. Acquisition of data: Marleen van der Velde and Sanne Tiellemans. Analysis/interpretation of data: Marleen van der Velde, Sanne Tiellemans, Heleen de Lil, and Laurens Nieuwenhuizen. Drafting of the manuscript: Marleen van der Velde and Sanne Tiellemans. Critical revision of the manuscript: Heleen de Lil and Laurens Nieuwenhuizen. This manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics approval was not sought because the data used is from previous published studies in which informed consent is obtained by primary investigators.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

This work was published with consent of the described patient.

Supporting information

Supplementary appendix 1: Search method

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank Eugenie Delvaux, biomedical information specialist of the Máxima MC, for her help in establishing the syntaxes for the PubMed search.

van der Velde MGAM, Tiellemans SMB, de Lil H, Nieuwenhuizen L. The value of leukapheresis for treatment of priapism as presenting feature of chronic myeloid leukemia—Case report and review of literature. eJHaem. 2022;3:1100–1115. 10.1002/jha2.545

Marleen G.A.M. van der Velde and Sanne M.B. Tiellemans contributed equally to this paper.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rodgers R, Latif Z, Copland M. How I manage priapism in chronic myeloid leukaemia patients. Br J Haematol. 2012;158(2):155–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Faderl S, Talpaz M, Estrov Z, O'Brien S, Kurzrock R, Kantarjian HM. The biology of chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(3):164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shaeer OK, Shaeer KZ, Abdel Rahman IF, El‐Haddad MS, Selim OM. Priapism as a result of chronic myeloid leukemia: case report, pathology, and review of the literature. J Sex Med. 2015;12(3):827–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ganguly S, Lakshmaiah KC, Jacob LA, Babu S, Dasappa L, Govind Babu KS. Performance of Sokal and Eutos scores for predicting cytogenetic and molecular response in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia‐chronic phase patients on imatinib. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfusion. 2017;33(1):82–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ali E, Soliman A, De Sanctis V, Nussbaumer D, Yassin M. Priapism in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML): a systematic review. Acta Bio‐Med. 2021;92(3):e2021193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marcu D, Iorga L, Mischianu D, Bacalbasa N, Balescu I, Bratu O. Malignant priapism—what do we know about it? In Vivo. 2020;34(5):2225–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Montague DK, Jarow J, Broderick GA, Dmochowski RR, Heaton JP, Lue TF, et al. American Urological Association guideline on the management of priapism. J Urol. 2003;170(4):1318–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Levey HR, Segal RL, Bivalacqua TJ. Management of priapism: an update for clinicians. Ther Adv Urol. 2014;6(6):230–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O'Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, Gathmann I, Baccarani M, Cervantes F, et al. Imatinib compared with interferon and low‐dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic‐phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(11):994–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chisick L, Seftel M, Kumar R. Algorithm for initial management of priapism in chronic myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2012;159(2):250–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Atas U, Meydanal YE, Iltar U, Ulas T, Salim O, Undar L. Priapism—a rare presentation of chronic myeloid leukaemia. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2019;13. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Castagnetti M, Sainati L, Giona F, Varotto S, Carli M, Rigamonti W. Conservative management of priapism secondary to leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51(3):420–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dhanju AS, Tyagi P, Dhaliwal SS, Paul S, Singh R, Singh J, et al. Priapism: a rare presentation in chronic myeloid leukemia. J Int J Adv Med. 2019;6(6):3 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kumar P, Rahman K, Kumari S, Singh MK, Gupta R, Nityanand S. Priapism as a rare presentation of chronic myeloid leukemia. J Cancer Res Therap. 2018;14(6):1442–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Musa A, Ndakotsu M, Abubakar S, Agwu P. Chronic myeloid leukemia with an initial presentation as ischemic priapism: a case report and review of literature. Arch Int Surg. 2017;7(2):68–72. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ocheni S, Ibegbulam O, Olusina D, Oyekunle A, Durosinmi M. Chronic myeloid leukaemia presenting as priapism: a report of 2 cases and review of literature. Int J Med Health Dev. 2010;15(2):76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Veljković D, Kuzmanović M, Mićić D, Šerbić‐Nonković O. Leukapheresis in management hyperleucocytosis induced complications in two pediatric patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Transf Apher Sci. 2012;46(3):263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Becerra‐Pedraza LC, Jiménez‐Martínez LE, Peña‐Morfin I, Nava‐Esquivel R, Villegas‐Martínez JA. Priapism as the initial sign in hematologic disease: case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;43:13–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gupta A, Seth T, Gupta A. Successful use of terbutaline in persistent priapism in a 12‐year‐old boy with chronic myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;26(1):70–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morano SG, Latagliata R, Carmosino I, Girmenia C, Dal Forno S, Alimena G. Treatment of long‐lasting priapism in chronic myeloid leukemia at onset. Ann Hematol. 2000;79(11):644–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gaye O, Thiam NM, Cassell A, Gueye SM, Sow Y, Fall B, et al. Unusual presentation of priapism associated with acute and chronic myeloid leukemia in two patients: emergency management. Case Rep Urol. 2020;2020:4982432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hazra SP, Priyadarshi V, Gogoi D, Sharma PK, Pal DK, Chakraborty SC. Pediatric priapism: a rare first manifestation of leukemia. APSP J Case Rep. 2013;4(3):39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huei TJ, Lip HT, Shamsuddin O. A rare presentation of chronic myeloid leukaemia with priapism treated with corporoglandular shunting. Med J Malaysia. 2018;73(6):420–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mishra K, Jandial A, Singh V, Radotra BD, Malhotra P. Priapism in chronic myeloid leukemia: meeting at the crossroads and heading in different directions. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2020;41:418. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Purohit AH, Sarangi S, Kumar D, Bohra GK, Saha S, Pandey H. Is priapism a common presentation of chronic myeloid leukemia in an adolescent patient? Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2021;21(2):147–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27. Sossa Melo CL, Orozco CA, Peña Castellanos AM, Rueda Perea MA, Porras Bueno CO, Romero Diaz CI, et al. Priapism as the first manifestation in chronic myeloid leukemia: a case report and focused review of literature. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9(11):e04901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Syarif, KK , Palinrungi MA, Syahrir S, Azis A, Arfan M. Priapism due to chronic myelocytic leukemia. Urol Case Rep. 2021;40:101946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abd El Salam MA, Ibrahim NH, Hassan S. Discontinuation of treatment in a chronic myeloid leukemia patient caused priapism: a case report. J Human Androl. 2019;9(1):21–3. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Avci AE, Kurtulus F, Fazlioglu A, Keskin S, Güçtaş Ö, Cek M. Priapism as an initial presentation of chronic myelogenous leukemia: a case report. UHOD. 2005;15:153–5. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chang MW, Tang CC, Chang SS. Priapism—a rare presentation in chronic myeloid leukemia: case report and review of the literature. Chang Gung Med J. 2003;26(4):288–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clark AJ, Hsu P, Darves‐Bornoz A, Tanaka ST, Mason EF, Katzenstein HM. Case 3: priapism in a 13‐year‐old boy. Pediatr Rev. 2018;39(12):617–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dhar J, Dhar J, Chhabra G, Khandelwal L, Khandelwal L, Batra A, et al. Priapism as a debut presentation of chronic myeloid leukemia. J College Physicians Surg. 2019;29(1):78–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dogra PN, Kumar P, Goel R, Dash SC. Long duration priapism in blast crisis of chronic myeloid leukemia. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ervie M, Boongaling DC, Rose S, Mortel C, Deala RP. Priapism as a rare presentation of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Philippine J Inter Med. 2015;53:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Farhan S, Anjum F, Al‐Qahtani F, Al‐Anazi KJ. Chronic myeloid leukemia presenting with priapism. J Leukemia. 2015;3.

- 37. Gupta A, Agrawal P, Aggarwal V, Sathi S. Priapism in CML. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2008;29(3):30–1. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jameel T,Mehmood K. Priapisman unusual presentation in chronic myeloid leukaemia: case report and review of the literature. Biomédica. 2009;25:197. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Khan A, Shafiq I, Shah MH, Khan S, Shahid G, Arabdin M. Chronic myeloid leukaemia presenting as priapism: a case report from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. J Pak Med Assoc. 2018;68(6):942–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Manuel MB, Leak A, Carroll SA. Priapism in the oncology setting. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11(1):23–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Minckler MR, Conser E, Figueroa JJ, Scott AJ, Gaither J, Amini R. The semantics of priapism and the first sign of chronic myeloid leukemia. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2017;2017:2656203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Narendra R, Shankar LJ, Sandeep J, Bardia MR. Priapism in teenager chronic myelogenous leukemia; a rare occurence. Asian J Pharm Health Sci. 2011;1(4). [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nerli RB, Magdum PV, Hiremath SC, Patil AY, Pai SV, Handigund RS, et al. Priapism—a rare presentation in chronic myeloid leukemia: case report. Urol Case Rep. 2016;4:8–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rajabto W, Djianzonie JAC, Pratisthita LB, Shatri H. Priapismus as leukostasis manifestation in chronic myeloid leukemia. Acta Med Indones. 2020;52(4):420–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patil PSK, Katariya P, Gaikwad N. Priapism—a rare presentation in chronic myeloid leukemia. Vidarbha J Inter Med. 2016;21:50–1. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ponniah A, Brown CT, Taylor P. Priapism secondary to leukemia: effective management with prompt leukapheresis. Int J Urol. 2004;11(9):809–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Qu M, Lu X, Wang L, Liu Z, Sun Y, Gao X. Priapism secondary to chronic myeloid leukemia treated by a surgical cavernosa‐corpus spongiosum shunt: case report. Asian J Urol. 2019;6(4):373–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sachdeva P, Kalra M, Thatikonda KB, Aggarwal SK, Sachdeva D, Sachdeva A. Stuttering priapism in a teenage boy: lesson to be learnt. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2021;43(8):e1118–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Swapna Y, Narmada B. Emergency leukapheresis in chronic myeloid leukemia presenting with priapism. Asian J Pharmaceutical Health Sci. 2017;7:1701–4. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Thakur P, Verma V, Fotedar V, Singh K. Priapism in a pediatric chronic myeloid leukaemia patient: unusual presentation of a rare disease in children. Clin Cancer Invest J. 2019;8(2):76–8. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wajih Ullah M, Rehman A, Cheeti A, Siddiq W, Latif WA, Prasai K, et al. Priapism and chronic myelogenous leukemia. Int J Adv Res. 2018;6:144–6. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Almaeena W, Azzuz S. Undiagnosed chronic myelogenous leukemia presented by priapism. Int J Acad Sci Res. 2020;4:20–1. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ammouri Z, Mouhaoui M. Priapism a rare and unusual presentation in chronic myeloid leukemia (a case report). AMMUR. 2019;3:36. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Htun T, Dublin N, Parameswaran M, Razack A, CJJoH Chua, Chronic myeloid leukaemia presenting as priapism “how should we treat these”. J Health Translat Med. 2008;11(1):27–9. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sareen R, Kapil M, Malpani BK. Priapism: a rare presentation of CML. J Hematol Oncol Forecast. 2018;1:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sun HH, Zhang JH, DeWitt‐Foy M, Waldron M, Mukherjee S, Montague DK. Urologic management of priapism secondary to chronic myeloid leukemia. Urology. 2019;125:24–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tazi I. Priapism as the first manifestation of chronic myeloid leukemia. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29(5):412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chowdhury ZZ, Al‐Asad H, Rahman MH et al. Management of priapism with chronic myeloid leukaemia—a rare presentation and our experiences. Haematol J Bangladesh. 2020;3:39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ekeke O, Omunakwe H, Nwauche C. Chronic myeloid leukaemia presenting as priapism. Int Surg. 2015;100:552–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jandial A, Mishra K, Sandal R, Lad D, Prakash G, Khadwal A ea. CML patients presenting with priapism: is there any disparity in outcome? J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15). [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kumar M, Garg G, Sharma A, Pandey S, Singh M, Sankhwar SN. Comparison of outcomes in malignant vs. non‐malignant ischemic priapism: 12‐year experience from a tertiary center. Turk J Urol. 2019;45(5):340–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kurosawa H, Tanizawa A, Tono C, Watanabe A, Shima H, Ito M, et al. Leukostasis in children and adolescents with chronic myeloid leukemia: Japanese pediatric leukemia/lymphoma study group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(3):406–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Nabi G, Dogra PN. Chronic myeloid leukaemia presenting as priapism in children: need for multidisciplinary approach. East Afr Med J. 2000;77(10):576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pal DK, Biswal DK, Ghosh B. Outcome and erectile function following treatment of priapism: an institutional experience. Urol Ann. 2016;8(1):46–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tendulkar AA, Jain PA, Gupta A, Sharma N, Navkudkar A, Patle V. Therapeutic leukocyte reduction for acute and chronic myeloid leukemias: a 4‐year experience from an oncology center in India. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2017;11(2):156–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ergenc H, Varım C, Karacaer C, Çekdemir D. Chronic myeloid leukemia presented with priapism: effective management with prompt leukapheresis. Nigerian J Clin Pract. 2015;18(6):828–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kumar P, Rahman K, Kumari S, Singh M, Gupta R, Nityanand S. Priapism as a rare presentation of chronic myeloid leukemia. J Cancer Res Therap. 2018;14(6):1442–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hazra S, Priyadarshi V, Gogoi D, Sharma P, Pal D, Chakraborty S. Pediatric priapism: a rare first manifestation of leukemia. APSP J Case Rep. 2013;4(3):39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Huei T, Lip H, Shamsuddin O. A rare presentation of chronic myeloid leukaemia with priapism treated with corporoglandular shunting. Med J Malaysia. 2018;73(6):420–2. [PubMed]

- 70. Rinaldi I, Sari RM, Tedhy VU, Winston K. Leukapheresis does not improve early survival outcome of acute myeloid leukemia with leukostasis patients—a dual‐center retrospective cohort study. J Blood Med. 2021;12:623–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ciftciler R, Haznedaroglu IC. Tailored tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) based on current evidence. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(24):7787–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Geelen IGP, Thielen N, Janssen J, Hoogendoorn M, Roosma TJA, Willemsen SP, et al. Treatment outcome in a population‐based, ‘real‐world’ cohort of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2017;102(11):1842–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Adams BD, Baker R, Lopez JA, Spencer S. Myeloproliferative disorders and the hyperviscosity syndrome. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2009;27(3):459–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Porcu P, Cripe LD, Ng EW, Bhatia S, Danielson CM, Orazi A, et al. Hyperleukocytic leukemias and leukostasis: a review of pathophysiology, clinical presentation and management. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;39(1–2):1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Tan D, Hwang W, Goh YT. Therapeutic leukapheresis in hyperleukocytic leukaemias—the experience of a tertiary institution in Singapore. Ann Acad Med. 2005;34(3):229–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Singh N, Singh Lubana S, Dabrowski L, Sidhu G. Leukostasis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e924798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hölig K, Moog R. Leukocyte depletion by therapeutic leukocytapheresis in patients with leukemia. Transf Med Hemother. 2012;39(4):241–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Malkan UY, Ozcebe OI. Leukapheresis do not improve early death rates in acute myeloid leukemia patients with hyperleukocytosis. Transfus Apher Sci. 2017;56(6):880–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Pryor J, Akkus E, Alter G, Jordan G, Lebret T, Levine L, et al. Priapism. J Sexual Med. 2004;1(1):116–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zhang D, Zhu Y, Jin Y, Kaweme NM, Dong Y. Leukapheresis and hyperleukocytosis, past and future. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:3457–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Oberoi S, Lehrnbecher T, Phillips B, Hitzler J, Ethier MC, Beyene J, et al. Leukapheresis and low‐dose chemotherapy do not reduce early mortality in acute myeloid leukemia hyperleukocytosis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Leuk Res. 2014;38(4):460–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary appendix 1: Search method

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.