Abstract

Background

People experiencing financial burden are underrepresented in clinical trials.

Objective

Describe the prevalence of cost-related considerations influential to trial participation and their associations with person-level characteristics.

Design

This cross-sectional study used and assessed how three cost-related considerations would influence the decision to participate in a hypothetical clinical trial.

Participants

A total of 3682 US adult respondents to the Health Information National Trends Survey

Main Measures

Survey-weighted multivariable logistic regression estimated associations between respondent characteristics and odds of reporting cost-related considerations as very influential to participation.

Key Results

Among 3682 respondents, median age was 48 (IQR 33–61). Most were non-Hispanic White (60%), living comfortably or getting by on their income (74%), with ≥ 1 medical condition (61%). Over half (55%) of respondents reported at least one cost-related consideration as very influential to trial participation, including if usual care was not covered by insurance (reported by 42%), payment for participation (24%), or support for participation (24%). Respondents who were younger (18–34 vs. ≥ 75, adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 4.3, 95% CI 2.3–8.1), more educated (high school vs. <high school, aOR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1–4.1), or with lower perceived income (having difficulty vs. living comfortably, aOR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1–3.8) had higher odds of reporting any cost-related consideration as very influential to trial participation. Non-Hispanic Black vs. non-Hispanic White respondents had 29% lower odds (95% CI 0.5–0.9) of reporting any cost-related consideration as very influential to trial participation.

Conclusions

Cost-related considerations would influence many individuals’ decisions to participate in a clinical trial, though prevalence of these concerns differed by respondent characteristics. Reducing financial barriers to trial participation may promote equitable trial access and greater trial enrollment diversity.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-022-07801-0.

KEY WORDS: clinical trials, financial hardship, cost of care, health care access

BACKGROUND

Clinical trials provide the evidence-base for new medical, surgical, and behavioral therapies. Demographically and clinically diverse participants, including those of minoritized racial and ethnic groups, those of sexual and gender groups, or those with comorbid conditions, are necessary to ensure clinical trial results are generalizable at the population level and do not widen existing health disparities.1 Individuals who more often experience financial burden are another population group systematically underrepresented in clinical trials, potentially due to their associated costs.2–4 Underrepresentation of economically vulnerable individuals in clinical trials may exacerbate existing disparate outcomes due to associations with health care access issues.1 Recent policy efforts have sought to diversify clinical trial participation by improving coverage of routine clinical care costs associated with participation.5 However, trial participants are still faced with non-routine care costs, such as those for treating trial-related symptoms or side effects, transportation, lodging, meals, child or elder care, and productivity losses.6 Little is known about how these cost-related considerations influence trial participation among US adults.

Understanding cost-related influences on trial participation is key to informing policy and trial design efforts aimed at promoting more diverse and representative clinical trial enrollment. Therefore, this study describes the prevalence of cost-related considerations influential to clinical trial participation using a large sample of US adults. Additionally, we explore associations between these cost-related considerations and person-level characteristics related to clinical trial participation in previous studies, including race or ethnicity, household income, geographic residence, education, and insurance status.3,7

METHODS

Study Design and Sample

This cross-sectional study used data from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) 5 Cycle 4, collected February through June 2020 via mailed questionnaires. HINTS is a publicly available, cross-sectional, nationally representative survey of civilian, non-institutionalized US adults that assesses knowledge of, attitudes toward, and use of health-related information.8, 9 Respondents’ return of the completed survey indicated consent to participate. HINTS data are deidentified and thus exempt from review by the US National Institutes of Health Office of Human Subjects Research Protections.

Outcome: Cost-Related Considerations for Hypothetical Participation in Clinical Trials

After reading a plain language definition of clinical trials, with a drug trial and behavioral intervention provided as examples, respondents were asked to imagine being invited to participate in a clinical trial for a health issue (Supplemental Figure 1). Respondents then rated the extent to which (1) receiving payment for participation (“I would get paid to participate”), (2) support for participation (”I would get support to participate such as transportation, childcare, or paid time off from work”), and (3) if usual care was not covered by insurance (“If the standard care was not covered by my insurance”) would influence their decision to participate. Responses were captured on a 4-point scale (a lot, somewhat, a little, not at all) and then dichotomized for analysis using top-box scoring as “a lot” versus the combined scores of “somewhat,” “a little,” and “not at all” to differentiate the most influential cost-related considerations on decision to participate in a clinical trial.10–12

Covariables

Demographic variables included age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, objective household income, subjective feelings about present income, marital status, rural/urban residence,13 census region, employment status, and health insurance status. Medical histories included number of diagnosed medical conditions, self-reported health, and annual health care visits.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were weighted to estimate nationally representative estimates using complex survey methodology with jackknife replicate weights for accurate standard errors.8 Respondent demographic and clinical characteristics were described for three groups: (1) overall sample, (2) respondents who reported at least one cost-related consideration as very influential to trial participation, and (3) respondents who reported no cost-related considerations as very influential. Survey-weighted medians, interquartile ranges, frequencies, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated as appropriate. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% CIs from an exploratory, survey-weighted logistic regression model estimated associations between respondent characteristics and odds of reporting a cost-related consideration as very influential to trial participation. Covariable multicollinearity was examined using the variance inflation factor (range=1.0–3.6). Sensitivity analyses estimated associations between respondent characteristics and cost-related considerations dichotomized using bottom-box scoring (a lot/somewhat/a little vs. not at all), and individual cost-related consideration as separate outcomes. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

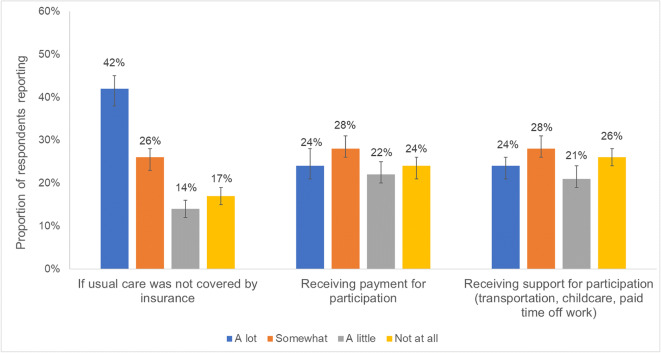

RESULTS

A total of 15,347 HINTS 5 Cycle 4 surveys were mailed, 3865 were returned and eligible for analysis (37% weighted response rate), and 3682 with complete information on cost-related considerations for trial participation were included in our sample. The median age of respondents was 48 (IQR 33–61), most were non-Hispanic White (60%), employed (58%), living comfortably or getting by on their present income (74%), and had ≥ 1 medical condition (61%; Table 1). Over half (55%, 95% CI 51–59%) of respondents reported at least one cost-related consideration as very influential to trial participation (vs. somewhat/a little/not at all). Of cost-related considerations, respondents most often reported usual care uncovered by insurance as very influential to participation (42%, 95% CI 38–45%), followed by receiving payment for participation (24%, 95% CI 21–28%), and receiving support for participation (24%, 95% CI 21–26%; Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Multivariable Exploratory Analysis of Reporting at Least One Cost-Related Consideration as Influential to Hypothetical Clinical Trial Participation by Respondent Demographic, Clinical, and Health Behavior–Related Characteristics (N=3682)

| Total, N=3682 | Reported cost-related consideration, n=1897 | Did not report cost-related consideration, n=1785 | Adjusted odds of reporting at least one cost-related consideration vs. none, N=3682 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (weighted %) | n (weighted %) | n (weighted %) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Age (weighted median, IQR) | 48 (33–61) | 45 (31–57) | 52 (37–65) | |

| 18–34 | 479 (26.0) | 308 (64.1) | 171 (35.9) | 4.28 (2.26–8.14) |

| 35–49 | 688 (25.2) | 423 (62.4) | 265 (37.6) | 4.00 (2.16–7.41) |

| 50–64 | 1110 (27.2) | 566 (50.9) | 544 (49.1) | 2.18 (1.24–3.84) |

| 65–74 | 820 (11.3) | 379 (44.8) | 441 (55.2) | 1.51 (1.03–2.21) |

| ≥ 75 | 487 (8.0) | 181 (33.5) | 306 (66.5) | 1 [Reference] |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1507 (48.0) | 737 (54.0) | 770 (46.0) | 0.84 (0.63–1.12) |

| Female | 2102 (50.3) | 1132 (56.4) | 970 (43.6) | 1 [Reference] |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2087 (59.7) | 1142 (58.2) | 945 (41.8) | 1 [Reference] |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 456 (10.3) | 237 (53.1) | 219 (46.9) | 0.71 (0.52–0.97) |

| Hispanic | 515 (14.1) | 246 (50.3) | 269 (49.7) | 0.62 (0.41–0.95) |

| Other race/multiracial | 317 (9.3) | 155 (52.1) | 162 (47.9) | 0.67 (0.43–1.03) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 244 (7.6) | 80 (33.6) | 164 (66.4) | 1 [Reference] |

| High school degree | 655 (21.4) | 304 (53.1) | 351 (46.9) | 2.12 (1.10–4.06) |

| Some college | 1046 (38.6) | 550 (57.6) | 496 (42.4) | 2.26 (1.19–4.29) |

| College graduate or higher | 1627 (30.0) | 917 (58.8) | 710 (41.2) | 2.17 (1.08–4.34) |

| Annual household income | ||||

| $0–$19,999 | 582 (13.7) | 278 (50.0) | 304 (50.0) | 1 [Reference] |

| $20,000–$34,999 | 428 (10.4) | 218 (56.5) | 210 (43.5) | 1.25 (0.67–2.31) |

| $35,000–$49,999 | 444 (11.6) | 209 (55.3) | 235 (44.7) | 1.26 (0.76–2.12) |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 575 (16.9) | 305 (55.0) | 270 (45.0) | 1.13 (0.62–2.08) |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 397 (11.6) | 216 (56.0) | 181 (44.0) | 1.05 (0.55–2.02) |

| ≥ 100,000 | 905 (28.1) | 525 (58.0) | 380 (42.0) | 1.16 (0.58–2.32) |

| Feelings about present income | ||||

| Living comfortably on present income | 1393 (34.6) | 696 (50.2) | 697 (49.8) | 1 [Reference] |

| Getting by on present income | 1379 (39.5) | 715 (56.6) | 664 (43.4) | 1.38 (1.00–1.89) |

| Finding it difficult on present income | 507 (15.1) | 282 (59.5) | 225 (40.5) | 1.70 (1.14–2.52) |

| Finding it very difficult on present income | 211 (6.2) | 127 (63.2) | 84 (36.8) | 2.08 (1.14–3.82) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/living as married | 1921 (53.5) | 998 (54.0) | 923 (46.0) | 1 [Reference] |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 1025 (13.5) | 490 (49.0) | 535 (51.0) | 0.93 (0.72–1.22) |

| Single, never married | 623 (30.3) | 364 (59.9) | 259 (40.1) | 1.00 (0.72–1.39) |

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | 292 (8.2) | 142 (51.2) | 150 (48.8) | 0.84 (0.54–1.33) |

| Urban | 3390 (91.8) | 1755 (55.4) | 1635 (44.6) | 1 [Reference] |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 547 (17.5) | 274 (54.0) | 273 (46.0) | 1 [Reference] |

| Midwest | 620 (20.9) | 337 (56.1) | 283 (43.9) | 1.06 (0.65–1.72) |

| South | 1644 (38.0) | 847 (54.8) | 797 (45.2) | 1.10 (0.79–1.52) |

| West | 871 (23.6) | 439 (55.4) | 432 (44.6) | 1.15 (0.79–1.68) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 1832 (58.0) | 1049 (60.3) | 783 (39.7) | 1 [Reference] |

| Retired | 1135 (18.1) | 501 (41.8) | 634 (58.2) | 0.83 (0.56–1.23) |

| Unemployed/disabled | 322 (9.8) | 173 (56.4) | 149 (43.6) | 0.99 (0.63–1.57) |

| Other | 288 (11.7) | 127 (48.9) | 161 (51.1) | 0.66 (0.37–1.18) |

| Health insurance status | ||||

| Private/employer sponsored | 1517 (48.2) | 867 (58.5) | 650 (41.5) | 1 [Reference] |

| Medicare | 1124 (18.8) | 502 (45.2) | 622 (54.8) | 1.37 (0.88–2.12) |

| Medicaid | 329 (11.3) | 179 (56.4) | 150 (43.6) | 0.95 (0.57–1.59) |

| Dual eligible | 225 (3.9) | 98 (39.8) | 127 (60.2) | 0.87 (0.41–1.81) |

| Other* | 254 (7.7) | 138 (64.1) | 116 (35.9) | 1.53 (1.03–2.27) |

| Uninsured | 192 (9.0) | 94 (54.9) | 98 (45.1) | 0.93 (0.44–1.98) |

| Number of medical conditions | ||||

| 0 | 1121 (38.4) | 595 (56.9) | 526 (43.1) | 1 [Reference] |

| 1 | 1141 (30.8) | 589 (55.0) | 552 (45.0) | 0.96 (0.69–1.34) |

| 2 | 796 (18.9) | 413 (57.0) | 383 (43.1) | 1.16 (0.74–1.80) |

| ≥ 3 | 592 (11.5) | 291 (47.3) | 301 (52.7) | 0.93 (0.56–1.55) |

| Self-rated health | ||||

| Excellent/very good | 1741 (50.0) | 945 (57.8) | 796 (42.2) | 1 [Reference] |

| Good | 1340 (35.8) | 655 (52.1) | 685 (47.9) | 0.88 (0.67–1.16) |

| Fair/poor | 585 (13.9) | 291 (53.5) | 294 (46.5) | 1.01 (0.64–1.62) |

| Saw provider in last year | ||||

| Yes | 3185 (83.0) | 1687 (56.4) | 1498 (43.6) | 1.52 (1.10–2.08) |

| No | 471 (16.4) | 203 (48.9) | 268 (51.1) | 1 [Reference] |

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

*Includes coverage by the VA, TRICARE/other military health care, Indian Health Service, or a response of “any other type of health insurance or health coverage plan”

Figure 1.

Respondent reporting of the extent to which cost-related considerations would influence hypothetical participation in clinical trials (N=3682).

In descriptive comparisons, respondents more often reporting at least one cost-related consideration as very influential to trial participation were younger (64% aged 18–34 years vs. 34% aged ≥ 75 years), more educated (59% college graduate or higher vs. 34% < high school education), employed compared to retired (60% vs. 42%), enrolled in private or employer-sponsored health insurance compared to dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid (59% vs. 40%), or had lower perceived income (63% finding it difficult vs. 50% living comfortably on their present income; Table 1).

Associations between reporting cost-related considerations as very influential to trial participation and respondent characteristics were seen in multivariable model results (Table 1). Compared to those aged 75 and older, younger respondents had higher odds of reporting any cost-related considerations as very influential to clinical trial participation (aged 18–34 aOR 4.28, 95% CI 2.26–8.14; aged 35–49 aOR 4.00, 95% CI 2.16–7.41; aged 50–64 aOR 2.18, 95% CI 1.24–3.84; aged 65–74 aOR 1.51, 95% CI 1.03–2.21). Non-Hispanic Black respondents had 29% lower odds (95% CI 0.52–0.97) and Hispanic respondents 38% lower odds (95% CI 0.41–0.95) of reporting cost-related considerations as very influential to trial participation when compared to non-Hispanic White respondents. Respondents with a high school education or more had two-times higher odds of reporting cost-related considerations as very influential to trial participation compared to those with less than a high school education (high school degree aOR 2.12, 95% CI 1.10–4.06; some college aOR 2.26, 95% CI 1.19–4.29; college graduate or higher aOR 2.17, 95% CI 1.08–4.34). Subjective income also showed associations with hypothetical trial participation, with respondents getting by on their present income having 38% higher odds (95% CI 1.00–1.89), respondents finding it difficult on their present income having 70% higher odds (95% CI 1.14–2.52), and respondents finding it very difficult on their present income having 108% higher odds (95% CI 1.14–3.82) of reporting cost-related considerations as very influential to trial participation compared to those living comfortably on their present income. Respondents who saw their health care provider in the previous year also had 52% higher odds of reporting a cost-related consideration as very influential compared to those who did not (95% CI 1.10–2.08). Sensitivity analyses showed similar associations and directionality to the multivariable model results (Supplemental Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Over half of respondents to this nationwide survey reported at least one cost-related consideration as very influential in their decision to participate in a hypothetical clinical trial. Respondents most often reported usual care not covered by insurance would influence participation, followed by receipt of payment or support for participation. Furthermore, cost-related considerations influential to trial participation differed by person-level characteristics. Respondents who were younger, non-Hispanic White, more educated, not living comfortably on their present income, or who saw their health care provider in the previous year had higher odds of reporting at least one cost-related consideration as influential to participation in a hypothetical clinical trial. Our results are unique, since data on cost-related considerations associated with clinical trial participation are rarely captured in disease agnostic patient samples, yet are needed for government and payer reimbursement policies to address all disease settings. Our results also point to the importance of including socioeconomically diverse patients for clinical representativeness, as well as the potential to increase trial enrollment for individuals who are financially sensitive by addressing perceived and actual cost-related barriers for a wide range of patients.

Financial barriers to clinical trial participation are prevalent, with 55% of our survey respondents reporting a cost-related consideration as influential to trial participation. This suggests future work should test strategies focused on reducing financial barriers to participation. Reimbursement for direct and indirect costs (e.g., travel, parking, lodging, caregiving expenses) is one potential strategy that could aid in reducing the financial burden experienced by participants and allow for more generalizable trial samples. Reimbursement for trial-related travel and lodging costs was shown to increase cancer clinical trial enrollment for younger, lower income patients experiencing financial burden.14 It is important to note the difference between reimbursement for actual trial-related expenses and undue influence of financial incentives or coercion, which is cited as an ethical concern associated with payment or support for clinical trial participation. From the patient perspective, current clinical trial participants believed monetary reimbursement would not coerce individuals to participate if they found the trial protocol unacceptable at enrollment, and would instead act as beneficial compensation reflecting the time, inconvenience, and risks related to participation.15 Researchers have also postulated that Institutional Review Boards should consider whether reimbursements for research participation are high enough to protect against patient exploitation or overburden.16 This stance is emphasized by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which does not consider payment for research participation as a benefit for research participation, but rather a “just and fair” practice.17 The American Society of Clinical Oncology echoes this viewpoint and includes removal of “impediments to ethically appropriate financial compensation for trial-related out-of-pocket costs” and eliminating the perception of patient financial support as undue influence as one of its four policy recommendations to decrease financial barriers to cancer clinical trial participation.4 These stances were recently reflected at the state levels in enacting legislation which provides patient expense reimbursement for cancer clinical trial participation. However, as Largent and Lynch argue, these laws should be expanded to all states and to include all areas of clinical research to ensure equitable trial access and increased trial enrollment for individuals with and without financial burden considering participation.18

Our results showed increasing odds of reporting a cost-related consideration influential to trial enrollment as age decreased. Younger respondents may face more financial barriers related to employment, including productivity loss or lost wages due to time off work to receive trial-related care, when compared to older, potentially retired respondents. Our descriptive results support this hypothesis, since respondents who were employed more often reported a cost-related consideration as very influential to trial participation compared to retired adults. In a study of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms, 21% reported having missed more workdays while on trial compared to if they had not participated, and 12% reported they would not have participated if they had known about the associated financial consequences.19

However, few studies have explored how concerns about potential employment disruptions, including lost wages, lost productivity, and job loss, influence clinical trial participation. Likewise, patient-level data collected during clinical trials typically do not capture adverse employment outcomes due to trial participation or trial therapy-related side effects, complications, or adverse events. The FDA has recently recommended collecting employment-related outcomes for individuals enrolled in cancer clinical trials.20 Collecting employment-related outcomes during trial screening, enrollment, and monitoring could aid health care organizations and clinicians in understanding how to decrease employment-related barriers to trial participation. Furthermore, scheduling care around a patient’s work schedule, proactively managing work-limiting side effects, receiving reimbursement for lost wages, or receiving paid time off work could increase younger adult participation in clinical trials.

Our descriptive results revealed respondents enrolled in private or employer-sponsored health insurance more often reported cost-related considerations as very influential to trial enrollment when compared to respondents enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, dually enrolled, or even those uninsured. Though this association was not seen in multivariable models, it is still important since considering insurance enrollment only may mask differences in actual insurance coverage. Clinical trials are commonly offered to patients with chronic and costly health conditions, and trial participation increases interactions with the health care system. Thus, patients with private, high deductible plans could face substantial out-of-pocket trial-related expenses before insurance covers care costs. Though insurers cover costs related to routine care received during the trial, research costs not covered by the trial sponsor, such as the trial treatment itself, trial-related labs, imaging, or procedures, or out-of-network trial-related care is at the expense of the patient.21, 22 For example, individuals interested in a cancer clinical trial often receive trial treatment at a National Cancer Institute (NCI)–designated cancer center, yet only 41% of Affordable Care Act Marketplace plans include an NCI-designated cancer center in-network.23 It is therefore important to ensure potential trial enrollees do not incur high out-of-pocket costs associated with trial participation due to their health insurance coverage status.

In our study, respondents not living comfortably on their present income had 38–108% higher odds of reporting a cost-related consideration influencing trial participation compared to those living comfortably on their income. Interestingly, no associations were found between measures of objective annual household income and report of cost-related considerations in our study. This contrasts with other studies, where individuals earning <$50,000 of annual household income had 32% lower odds of cancer clinical trial participation compared to those earning higher incomes.2 Our results may point to the importance of differentiating between cost and affordability when assessing financial barriers to trial participation. Potential participants may have similar incomes, but unequal participation affordability due to the number of people being supported on their household income, household expenses, or differences in trial participation costs such as transportation or childcare. Thus, clinicians should consider collecting both subjective and objective measures of patient-reported income data as part of their research since both measures may be important to clinical trial participation.

Non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic respondents had lower odds of reporting a cost-related consideration as very influential to trial participation compared to non-Hispanic White respondents in our study. Few data exist on the association between race and ethnicity and cost-specific barriers to clinical trial participation. One study found that patients who are African American or Hispanic discuss trial treatment costs more frequently than non-Hispanic White patients. However, it is unclear how these discussions affect participation.24 We can hypothesize that other factors related to trial participation, such as trust in the health care system or their provider,25 may be more influential in the decision to participate compared to cost.

Our results also showed associations between higher education levels or more frequent interactions with the health care system and reporting cost-related considerations as very important to trial participation. These results may be secondary to a patient’s level of activation, defined as the knowledge, skills, and confidence to manage one’s health.26, 27 We hypothesize that respondents with higher levels of activation may have higher levels of education and more frequently utilize the health care system, and thus have more awareness of the costs related to trial participation. Likelihood of trial participation increased for patients with cancer involved in a demonstration project sponsored by the Education Network to Advance Cancer Clinical Trials, which utilized patient navigators to aid in increasing patient activation and trial-related education.6 However, it is unknown if and how trial cost discussions were incorporated into the activation and education strategies. More research is needed to understand associations between education, health care use, and cost-related considerations for clinical trial participation to tailor interventions which drive increases in trial participation.

The results of our study should be considered within the context of several limitations. Selection or response bias may exist due to HINTS survey methods and response rates.28 However, the complex survey methodology used when analyzing HINTS data adjusts for non-responders based on the measured characteristics of HINTS sample members known to be related to response propensity, which minimizes non-response bias. Model misspecification may exist based upon omitted variable bias due to the use of secondary survey data, overfitting due to including an irrelevant covariable, or potential covariable measurement error. Questions surrounding cost-related considerations for clinical trial participation were based on hypothetical trial participation, which may differ from respondent considerations when making actual trial participation decisions. Because this survey was fielded in Spring 2020, results may also be influenced by increased awareness of trials or financial issues faced by American public due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, proportions of respondents reporting cost-related considerations to trial participation were similar for surveys returned both before and after March 11, 2020, the date the pandemic was declared.

CONCLUSION

Cost-related considerations were influential in the hypothetical decision to participate in a clinical trial, with 55% of survey respondents reporting at least one consideration. These results suggest that financial barriers to trial participation are one of many important factors to consider in assessing participation equity and can inform clinical trial decision-makers at multiple levels. Policy makers and payers should consider creating trial cost policies that are easily accessible and straightforwardly conveyed to individual enrollees. Trial sponsors should consider reimbursement for non-medical costs related to trial participation. Health care systems and clinicians who offer trials should be aware of trial-related costs, and clearly communicate these potential costs to eligible and interested patients. Finally, trial decision-makers should work to better quantify trial-related costs, including out-of-pocket medical and non-medical costs, employment outcomes, and how costs may differ for various patient sociodemographic groups, to better understand the financial impact of trial participation. Because our results suggest cost-related considerations influencing clinical trial participation may differ in their appeal to particular patients, more empirical evidence is needed to test cost-offsetting mechanisms, which could aid in increasing trial participation, and thus improve socioeconomic equity in access to trials and increase socioeconomic generalizability from clinical trials to a broader range of participants.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 405 kb)

Data Availability

The Health Informatics National Trends data are publicly available from the National Cancer Institute, https://hints.cancer.gov/.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimers

The observations and conclusions expressed in this article are those of the authors and this material should not be interpreted as representing the official viewpoint of the US Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, or the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Prior presentations:

This study was presented as part of a symposium at the Society of Behavioral Medicine’s 43rd Annual Meeting & Scientific Sessions, April 6–9, 2022.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Diversity & Inclusion in Clinical Trials. National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health. https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/resources/understanding-health-disparities/diversity-and-inclusion-in-clinical-trials.html. Accessed July 2022.

- 2.Unger JM, Hershman DL, Albain KS, Moinpour CM, Petersen JA, Burg K, et al. Patient income level and cancer clinical trial participation. 2013;31(5):536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Chino F, Zafar SY. Financial toxicity and equitable access to clinical trials. 2019(39):11-8. 10.1200/edbk_100019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Winkfield KM, Phillips JK, Joffe S, Halpern MT, Wollins DS, Moy B. Addressing financial barriers to patient participation in clinical trials: ASCO policy statement. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(33):3331-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Clinical Treatment Act, Stat. 913 (December 22, 2020, 2019). https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/913/all-info.

- 6.Nipp RD, Hong K, Paskett ED. Overcoming barriers to clinical trial enrollment. 2019;39:105-14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Williams CP, Senft Everson N, Shelburne N, Norton WE. Demographic and health behavior factors associated with clinical trial invitation and participation in the United States. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(9):e2127792-e. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.27792 %J JAMA Network Open. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Health Information National Trends Survey. National Cancer Institute. https://hints.cancer.gov/. Accessed 6 Nov 2020.

- 9.Finney Rutten LJ, Blake KD, Skolnick VG, Davis T, Moser RP, Hesse BW. Data resource profile: the national cancer institute’s health information national trends survey (HINTS). Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49(1):17-j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, Goldstein E, Lehrman W, Hambarsoomians K, Beckett MK, et al. Effects of survey mode, patient mix, and nonresponse on CAHPS® hospital survey scores. 2009;44(2p1):501-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Jurdi ZR, Crosby JFJ. Key patient experience drivers that result in exemplary overall provider performance ratings in the ambulatory environment: a quantitative study. J Ambul Management. 2022;45(3):182–90. doi: 10.1097/jac.0000000000000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abid MH, Lucier DJ, Hidrue MK, Geisler BP. The effect of standardized hospitalist information cards on the patient experience: a Quasi-Experimental Prospective Cohort Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2022. 10.1007/s11606-022-07674-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. United States Department of Agriculture. 2016. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/.

- 14.Nipp RD, Lee H, Powell E, Birrer NE, Poles E, Finkelstein D, et al. Financial burden of cancer clinical trial participation and the impact of a cancer care equity program. Oncologist. 2016;21(4):467-74. 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Breitkopf CR, Loza M, Vincent K, Moench T, Stanberry LR, Rosenthal SL. Perceptions of reimbursement for clinical trial participation. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics : JERHRE. 2011;6(3):31–8. doi: 10.1525/jer.2011.6.3.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Largent EA, Lynch HF. Paying research participants: the outsized influence of “Undue Influence”. IRB. 2017;39(4):1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Payment and Reimbursement to Research Subjects. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/payment-and-reimbursement-research-subjects. Accessed March 2022.

- 18.Largent EA, Lynch HF. Addressing Financial Barriers to Enrollment in Clinical Trials. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(7):913-4. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0492. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Goel S, Paoli C, Iurlo A, Pereira A, Efficace F, Barbui T, et al. Socioeconomic burden of participation in clinical trials in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Eur J Haematol. 2017;99(1):36-41. 10.1111/ejh.12887. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Core Patient-Reported Outcomes in Cancer Clinical Trials: Guidance for Industry. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2021. https://fda.report/media/149994/Core-Patient-Reported-Outcomes-in-Cancer-Clinical-Trials_508ed.pdf. Accessed March 2022.

- 21.Health Insurance Coverage of Clinical Trials. American Society of Clinical Oncology, Cancer.Net. 2018. https://www.cancer.net/research-and-advocacy/clinical-trials/health-insurance-coverage-clinical-trials. Accessed March 2022.

- 22.Insurance Coverage and Clinical Trials. In: Cancer Treatment. National Cancer Institute. 2020. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials/paying/insurance. Accessed March 2022.

- 23.Kehl KL, Liao K-P, Krause TM, Giordano SH. Access to accredited cancer hospitals within federal exchange plans under the affordable care act. Journal of Clinical Oncology : Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(6):645-51. 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.9835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Perez EA, Jaffee EM, Whyte J, Boyce CA, Carpten JD, Lozano G, et al. Analysis of population differences in digital conversations about cancer clinical trials: advanced data mining and extraction study. 2021;7(3):e25621. 10.2196/25621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D, et al. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2010;21(3):879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Greene J, Hibbard JH. Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(5):520-6. 10.1007/s11606-011-1931-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Hamel LM, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Heath E, Gwede CK, Eggly S. Barriers to clinical trial enrollment in racial and ethnic minority patients with cancer. Cancer Control : Journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2016;23(4):327-37. 10.1177/107327481602300404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Maitland A, Lin A, Cantor D, Jones M, Moser RP, Hesse BW, et al. A nonresponse bias analysis of the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). J Health Commun. 2017;22(7):545-53. 10.1080/10810730.2017.1324539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 405 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The Health Informatics National Trends data are publicly available from the National Cancer Institute, https://hints.cancer.gov/.