Abstract

Background

Despite persistent racial disparities in maternal health in the USA, there is limited qualitative research on women’s experiences of discrimination during pregnancy and childbirth that focuses on similarities and differences across multiple racial groups.

Methods

Eleven focus groups with Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI), Black, Latina, and Middle Eastern women (N = 52) in the USA were conducted to discuss the extent to which racism and discrimination impact pregnancy and birthing experiences.

Results

Participants across groups talked about the role of unequal power dynamics, discrimination, and vulnerability in patient-provider relationships. Black participants noted the influence of prior mistreatment by providers in their healthcare decisions. Latinas expressed fears of differential care because of immigration status. Middle Eastern women stated that the Muslim ban bolstered stereotypes. Vietnamese participants discussed how the effect of racism on mothers’ mental health could impact their children, while Black and Latina participants expressed constant racism-related stress for themselves and their children. Participants recalled better treatment with White partners and suggested a gradient of treatment based on skin complexion. Participants across groups expressed the value of racial diversity in healthcare providers and pregnancy/birthing-related support but warned that racial concordance alone may not prevent racism and emphasized the need to go beyond “band-aid solutions.”

Conclusion

Women’s discussions of pregnancy and birthing revealed common and distinct experiences that varied by race, skin complexion, language, immigration status, and political context. These findings highlight the importance of qualitative research for informing maternal healthcare practices that reduce racial inequities.

Keywords: Discrimination, Maternity care, Pregnancy, Birthing, Focus groups

Introduction

Racial and ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related outcomes are an enduring problem in the USA [1, 2]. The role of racial bias in patient-provider experiences contributes to racial disparities in maternal health but can also serve as levers for change in policies aimed at reducing healthcare inequalities [1, 3–5]. However, there is little qualitative research examining women’s experiences of racism and discrimination in the context of pregnancy and birthing, and even fewer studies present perspectives from multiple racial and ethnic groups. Moreover, most studies were developed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which may not reflect contemporary experiences. Our study addresses this gap in the literature by synthesizing experiences of racism during pregnancy and birthing across four different racial/ethnic groups of women from across the USA.

The term “obstetric racism” describes the differential treatment of childbearing people based on race or ethnicity [6]. Research on this topic builds on medical racism research, which focuses on the mistreatment of people of color in clinical settings. For instance, a study examining a multi-ethnic sample of 2700 birthing women found that one in six women had experienced mistreatment by healthcare providers, but mistreatment varied by race/ethnicity—greater proportions of Indigenous (38%), Hispanic (25%), and Black (22.5%) women reported experiencing mistreatment compared to White women (14.1%) [7]. Importantly, women of color were twice as likely as White women to report that a healthcare provider had ignored, refused, or delayed treatment [7], which is particularly problematic because the delayed clinical response is associated with maternal mortality [4, 7]. Moreover, although racial disparities in birth outcomes, such as fetal deaths, stillbirths, or maternal deaths during hospitalizations, remained consistent with pre-COVID-19 levels [8, 9], women of color reported increased challenges in access to obstetric and mental healthcare compared to White women [10, 11]. Visitor restriction policies were more strictly enforced for women of color compared to White women, which isolated them from the social support systems that provided a source of advocacy and protection against discriminatory treatment by healthcare workers [12]. These findings highlight the importance of centering on women’s experiences of racism during pregnancy and birthing, with a more nuanced focus on the factors impacting different racial groups.

Much of the qualitative work on obstetric racism has focused on Black mothers’ experiences with racism during pregnancy and childbirth. Black women experience racialized pregnancy stigma—stereotypes that devalue Black pregnancies and motherhood—in everyday interactions, healthcare settings, and social services [13]. Stereotypes include the assumption that Black women are low-income, dependent on government resources like welfare, single, and have multiple children, regardless of their socioeconomic or marital status [13–15]. Within institutional settings, Black women report being ignored, having their experiences of pain dismissed, being treated by trainees disproportionately more than physicians, feeling like they received a different recommendation based on race, and feeling judged by social service providers [13, 16, 17]. In their gendered roles as nurturers, Black mothers and mothers-to-be cite the need to protect their children from the stressors of racism [13, 18, 19]. The stress of racism even impacts the decision to have children, with many Black women expressing fear of getting pregnant because of stories of trauma during the delivery they heard from other Black mothers [16].

Although Black mothers’ pregnancy-related health disparities have been the focus of the majority of the research [20, 21], revealing higher rates of anxiety, inflammatory response, and sleep disturbances in Black compared to White mothers [22, 23], research has also demonstrated disparities across minority racial groups in other pregnancy-related complications. For instance, research has demonstrated higher rates of intracerebral hemorrhage during pregnancy and postpartum in Black, Hispanic, and Asian mothers compared to White mothers [24]. Differences in health disparities observed between minority race populations can be attributed to a myriad of historical, political, and societal factors that individuated the experiences of racism across racial and ethnic groups. For example, language barriers in patient-provider interactions contribute to reductions in healthcare delivery for patients who do not speak the majority language, conferring a unique challenge for racial groups with large immigrant populations (e.g., Latina and Asian women in the USA) [10, 25], while policies leading to higher rates of incarceration are more specific to low-SES, Black birth outcomes [26]. In general, there is limited qualitative research on the experiences of racism for AAPI and Middle Eastern women, specifically during pregnancy and delivery. Thus, examining the lived experiences of pregnancy and birthing from women of different racial/ethnic backgrounds addresses a critical gap in order to better inform practices that can reduce maternal health disparities.

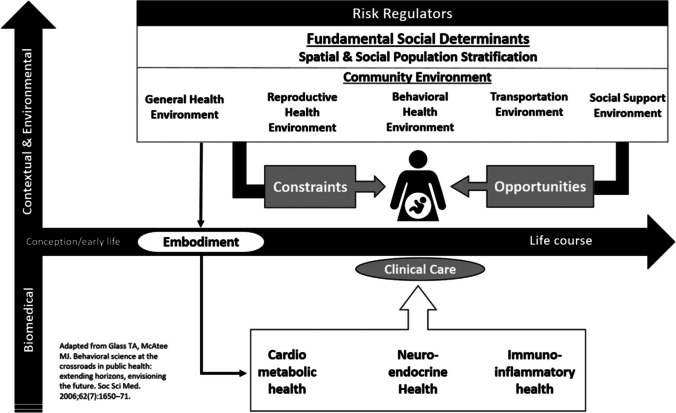

For the current paper, we adopted the health equity conceptual framework by Kramer and colleagues [27] (Fig. 1), which shifts focus from conventional clinical risk factors to provide a more holistic account of the challenges faced by women of color. This framework was originally used to explain racial and geographic disparities in maternal mortality, but the framework can be applied to reproductive health broadly. Under this conceptual framework, there are two dimensions that situate the birthing person. The first dimension focuses on the life course and health trajectory of the birthing person and the accumulation of exposures over the lifespan. The other dimension represents the multilevel determinants of health, from biomedical conditions and health services environment to social support and community environment. Racism in this model is considered a social determinant of health. We sought to understand the constraints and opportunities of women’s reproductive health environment toward a better understanding of how racism works as a determinant of their reproductive health.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework for reproductive health. Reprinted from Kramer et al. Changing the conversation: applying a health equity framework to maternal mortality reviews. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:609.e1-609.e9. with permission from Elsevier

Qualitative research can provide an in-depth understanding of the human experience and provide insight into the “how” and “why” of a specific phenomenon and perspective [28]. The objective of the present paper is to explore the influence of racism on pregnancy, birthing, and child-rearing experiences from the perspectives of AAPI, Black, Latina, and Middle Eastern women. We also seek to gain an understanding of policies and programs that could support and promote maternal and child health from the perspectives of our racially and ethnically diverse focus group participants.

Methods

We recruited a purposive sample of 52 participants for eleven focus groups by posting flyers via social media (Twitter and Facebook) and by contacting student and community organizations (e.g., YMCA, Korean American Community Foundation NY, and Chicana Latina Foundation). Eligibility criteria included women who were at least 18 years old, use social media (Twitter, Facebook, etc.), have had children or are open to having children in the future, and self-identified as Black, Latina, Middle Eastern, Asian, or Pacific Islander and were available to participate in a 90-min focus group via Zoom. All participants received a $50 gift card. We conducted race- and ethnic-specific focus groups. Those interested were invited to complete a brief online survey to collect basic demographic information, including race, region of residence, contact information, and their availability to participate at the scheduled times.

Focus Group Guide Development

We used a semi-structured focus group guide developed based on a review of the literature and our research aims. The research questions necessitated that we include specific topics such as the extent to which racism and discrimination impact pregnancy and birth experiences, the influence of racism on mental and physical health during pregnancy, and whether there are policies or programs to help protect people from the impact of racism during pregnancy and birthing. Specific questions included the following: “Do you think racism and discrimination impact pregnancy and birth experiences? Why or why not? If so, how?”; “Are there any kinds of policies or programs that you think could help protect people from how racism impacts their pregnancy and birthing experiences?”; “What are some steps you have taken to protect yourself or somebody else from the impact of racism?”.

Data Collection and Analysis

The 90-min focus group sessions were audio-recorded, later transcribed, translated into English (if conducted in another language), and de-identified. Two study team members attended each focus group to provide support. We utilized rev.com for the transcription services. We had two transcripts that needed translation, which was conducted by study team members—one fluent in Spanish and the other fluent in Vietnamese. Those transcripts maintained the original language along with the English translation in order to be able to compare and clarify meaning when needed. The initial codebook was based on topics from the developed focus group guide. We evaluated the codebook through consensus-building discussions to ensure the accuracy and clarity of code definitions. We used Nvivo, a qualitative data analysis software package, to code the data based on the codebook. The team discussed coding disagreements and came to a consensus for all coding to prepare the data for theme development. The NVivo coding reports were a compilation of the focus groups based on race, with one report for the AAPI, Black, Latina, and Middle Eastern participants. We analyzed the NVivo coding reports through a series of team meetings to establish themes and connections within and across the focus groups for the different racial/ethnic groups. Throughout the process, we sought to maintain data trustworthiness, adhering closely to the transcripts from the participants for interpretations by using the constant comparison approach [19]. This approach involves the continuous interplay of comparing and contrasting textual data points to other data points in the dataset in order to discern conceptual similarities and solidify themes [29, 30]. We also utilized multiple data analysts with different racial/ethnic backgrounds. This study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board (18–24,593).

Results

Focus group participants included 15 Black, 21 Asian and Pacific Islander, 8 Middle Eastern, and 8 Latina women. The mean age was 35 years old. Most participants (75%) had a bachelor’s or graduate degree. The majority of focus group participants had children (75%), and of those with children, most had two children (71%). Of the focus group participants who did not have children, the majority stated that they planned to have children within 5 years (61%). Participants resided in the Western (n = 19), Northeastern (n = 16), and Southern (n = 17) USA.

Three themes related to experiences of racism during pregnancy and birthing emerged: (1) vulnerability and voice in pregnancy and birth experiences, (2) mental and physical health, and (3) representation and advocacy for appropriate care. We describe these themes in more depth below and provide some quotes as examples. Additional illustrative quotes are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Themes with illustrative examples

| Vulnerability and voice in pregnancy and birth experiences |

| “As well as just the subtle inherent racism that was part of every day of just the questions and assumptions that were made around what kind of job I had. Did I have this type of insurance? What did my spouse do? What was his role when he showed up? Questions that really… I don't know why they're pertinent to my medical history anyway but those types of conversations happened and were part of it. And I will fully acknowledge going out to that mental part. And then the inability to check folks because you're vulnerable to them in those moments” (Black FG 1) |

| “I’m sorry. I’m actually the opposite. I will check you. And I feel like I have to let you know, of course in a right way, I have to let you know. I had an incident when my son was born. He was in NICU. And we had a pretty traumatic birth experience. And I remember one of the main doctors on the floor being very rude and condescending to me and he was breaking down things but it was in a condescending manner. …It was just so inappropriate. And I remember checking him as well as going up the ladder so much so that I didn’t see him anymore for the rest of our stay. He was not there at all. And I made sure to let them know I don’t want him around my child. I don’t even want to see him when I come and visit. And they made that happen. They took it seriously” (Black FG 1.) |

| Vulnerability from the stigma related to being Muslim |

| I think something at that large of a scale, for the entire nation to say, ‘Hey, you guys are banned,’ is a free pass for everyone and every group and agency and department, to say, ‘Okay, we’re banning you too in some kind of way. We’re not banning you, verbatim we say you’re banned. We’re going to treat you as such and make you feel as such, because our entire country is giving us a free pass to do that.’ You can feel that everywhere. You can feel that walking into a store. You’re going to for sure feel it in a medical space as well” (Middle Eastern FG 9) |

| Fear of mistreatment in hospital setting |

| “I used to work for a project that was helping Latino women who had a baby or were pregnant… and a lot of those participants were experiencing fear in being in immigrant related situations, to being worried and everything related to their mental health. And one of the worries they had was if they were going to be accepted in hospital, if they were going to have trouble or what’s going to happen. They were uncertain to go to a hospital even” (Latina FG 11) |

| Another participant from the Spanish-speaking focus group revealed her thoughts about entering the healthcare setting: “Will they judge me when I go to the doctor? The receptionist is going to look at me with a bad face. They won’t understand me when I go to get the medicines.’ All that has an effect. Also, something that at least I would feel, that worries me a lot…” (Latina FG 10, translated) |

| “Ma’am, I’ve had two C-sections, I wanted to get in and I wanted to get out. So I wanted to get the care I needed, but didn’t want to labor it, I didn’t want to hang in there…and have my baby in the nursery kind of thing. I wanted to take advantage of the services, but I also wanted to come out of there because I know that there are or there is potentially, just being treated differently because you are a Black female or a brown person” (Black FG 2) |

| Differences in treatment |

| “My daughter’s father is white, and so I noticed difference in treatment by staff, and just in the world, I think, when I had been with him versus when I was not. In spaces where you would totally just be ignored, you realize there's a difference, like,” “Oh. They are acknowledging me now. They are speaking to me now. I am actually here, and they see me, and they’re treating me with a little bit more visibility than otherwise” (Middle Eastern FG 9) |

| “Just for example, in the same hospital where I gave birth to my daughter, I recommended that hospital for other women who were going to have their babies, and she was traumatized, and she was a non-English speaking person. She didn’t have someone that looked like my ex [who is white], and didn’t have anyone to advocate for her, or felt like they could advocate for her, and so she was treated horribly. She left, or stayed, in that space in tears because of staff basically almost verbally abusing her. And I was just so shocked and surprised by that treatment, as compared to mine” (Middle Eastern FG 9) |

| “I would say that every time I go into the hospital with a brown and black person, and see the level of condescension and just being pushed around and bullied and coerced into doing things in the hospital. I would say it impacts me negatively. I feel like I have vicarious trauma and a lot of rage, so watching that happen, and it's compounded by the fact that, because I have light skin and the ability to just code switch, and also channel my inner white lady to step up in these spaces that it highlights the injustice that all it takes is to be able to code switch or look a certain way to be able to navigate the hospital” (Pacific Islander FG 6) |

| Another participant reported the discriminatory treatment based on skin color: “I want to say my prenatal experience being a brown woman and trying to utilize general hospital… I just felt like I wasn’t treated with a lot of respect or value, and so… Just often, I wasn’t receiving the support that I needed” (Pacific Islander 6) |

| Positive health care experiences |

| “I feel very lucky that during the time that I was pregnant with my baby, my doctor was Vietnamese. When I delivered my baby, the entire doctor team was White and were very kind and motivated me through the process. When I said that I am not fluent in English, they went to find me a translator. The way they treated me made me feel loved and respected so I was very thankful and grateful to them” (Vietnamese FG5, translated) |

| Mental and physical health |

| “I think something that keeps coming up to mind is if I want to bring a child into the world that’s going to experience systematic oppression. …I know that these stressors that I’ve experienced the last 5, 10 years are stressors that more than likely will continue and will affect not only my physical well-being and mental well-being, but also my child’s wellbeing… I think it’s really fear-inducing to think about being pregnant or getting pregnant, if I would continue to deal with the same stressors that I have now…I think it would take a major toll on me” (Latina FG 11) |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

| “I have had a lot of friends who have babies during the COVID, so I’ve had seen how they were doing during this COVID, and I think they had a lot of difficulties. For example, they cannot go to the hospital with their husband… And usually, they are all Korean friends, so their parents can come to take care of them after giving birth, but they cannot have that. So I guess at COVID, they had a lot of difficulties carrying the baby and giving birth. And after that, they also had a lot of limited experience when they were having a birth. So some of my friends got vaccinated, but some people who weren't or who didn’t want get vaccinated, they were just staying home for nine months. And then after birth, they still had to stay in home for babies, so I think definitely COVID has impacted pregnancy experiences for women a lot” (Korean FG 4) |

| Representation and advocacy for appropriate care |

| “I just delivered a baby around 8 months now. When I was pregnant, I did see the doctor and the baby was a bit big so many doctors refused to see me, only the Vietnamese doctor agreed to see me. At that moment, I realized that the Vietnamese people care for me and my baby while doctors of other nationalities refused” (Vietnamese FG5, translated) |

| “I think representation matters. …Hospitals and healthcare facilities need to recruit folks, even from high school, like black and brown people, to get into the healthcare industry” (Middle Eastern FG 9) |

| Doulas and pregnancy groups |

| “…a doula that may be able to be right there with you and educate you and share experiences with you. Someone to be right there in the process from beginning to end” (Black FG 1) and “[The formal group] was only for black women who were pregnant, who are delivering around the same time. We all were going through the same thing and we’d be able to meet every week and share our experiences” (Black FG 3) |

| “…in which pregnant mothers can talk about their feelings and situations and receive resources, support…and speak English the way it comes, because you know that you are not the only person who is experiencing that situation” (Latina FG 10, translated) |

| Abortion and financial services |

| “I mean I think one thing that I think of is, who has access to abortion and not just who has access to abortion, but also in some places, there are a lot of women who have that option and maybe don’t actually want to have an abortion, but choose to do so because they don’t have the financial means to support a child…a social policy that I think is really useful is just making sure that people can afford living and having a home and food and knowing that. That is a guaranteed right” (Middle Eastern, FG8) |

| Mental health services and empathy |

| “Programs that help people who can see their mental health compromised, especially for pregnant women. I also think that it is very important to educate the alleged aggressor… Creating empathy, creating classes at school that open that universe to you as a person, how to be empathetic to the reality of others, that you know that there is a world beyond [the US]” (Latina FG 10, translated) |

| Empathy classes for children: “it could be something social where they teach you to have empathy for others and value what is empathy, consideration. It is not only from the face to the outside, but it really increases those values and in a certain way also incorporates the parents in those things, because what today’s children learn is what they see at home” (Latina FG 10, translated) |

| “Respectfully, I'm not referring to y’all, but just in general, we look at band-aid solutions to this really big problem. I think doula programs are great, having staffers or interpreters that are there that can understand culturally, linguistically as well, the patient… I work in a school district, we have a lot of these ABAR trainings, that are called anti-racist, anti-Blackness workshops in order to help promote inclusion and diversity and all the equity and things like that. Even with that, I still also think it’s a band-aid solution, but that can also be helpful for healthcare workers to try to understand and listen, you know what I mean? I think each healthcare institution can have a panel… can listen to the community, and kind of see where they are demographically and understand that these are people, even if they were lower income, even if they might not understand you, they’re also people, they bleed like you, and these are their needs, and this is where they came from." (Middle Eastern, FG 9) |

Vulnerability and Voice in Pregnancy and Birth Experiences

Many of the participants across focus groups reported the role of unequal power dynamics within the patient/provider relationship. As a result, women described feeling vulnerable and feeling that their voice had limited power, particularly in responding to discrimination. One participant shared a very uncomfortable situation while being examined:

“The first person who asked me about the [baby’s] name, literally had a wand in my vagina doing the sonogram. [The doctor asks,] ‘What are you thinking about naming your child?’ And when I said, David. “Oh good, a nice normal name.’ …So it catches me off guard sometimes because I wasn’t expecting it to happen or to come up again in these spaces… “I’m not going to check you and say, ‘You shouldn’t have said that’s a nice, normal name.’ Because I don’t know what you’re going to do next...” (Black FG 1).

In the Latina focus groups, participants reported that much of their vulnerability stemmed from their immigration status and speaking a different language. Middle Eastern participants expressed increased vulnerability from the stigma related to being Muslim after the Muslim ban, which was viewed as an informal signal that discrimination is permitted. Participants shared their fears about going to the hospital, whether they would be accepted or what treatment they would receive, which influenced their healthcare decisions. One participant discussed how concerns and fears around potential mistreatment in the medical system impacted her decision to have elective C-sections.

“Ma’am, I’ve had two C-sections, I wanted to get in and I wanted to get out. So I wanted to get the care I needed, but didn’t want to labor it, I didn’t want to hang in there…and have my baby in the nursery kind of thing…because I know that there are or there is potentially, just being treated differently because you are a Black female or a brown person” (Black FG 2).

A Black participant responded directly to discriminatory experiences in the hospital by making it known that she did not want the provider near her or her child after the provider was rude and condescending. However, this kind of direct response was rare.

Focus group participants shared how experiences in the health care setting can vary based on race/ethnicity, skin color, and language. One participant observed that she receives better treatment when her ex-partner, who is White, accompanies her to her medical visits. While she had a positive delivery experience, when she recommended the hospital to a non-English speaking woman, she stated the woman “did not have anyone to advocate for her” and was “treated horribly.” Participants in the Pacific Islander focus group reported how treatment varies based on skin complexion, with darker-skinned women receiving worse treatment. A participant who was light-skinned shared that she witnesses poorer treatment: “every time I go into the hospital with a Brown and Black person, and see the level of condescension and just being pushed around and bullied and coerced into doing things in the hospital” (Pacific Islander, FG 6).

Mental and Physical Health

Participants reported that racism took a toll on their mental and physical well-being before, during, and after their pregnancy. Latina and Black participants expressed how chronic racism-related stress created a constant worry for the well-being of oneself and one’s child. Compounding the existing racism-related stress, many of our participants reported that they experienced pregnancy during hospital lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which was marked by periods of isolation away from friends and family members during pregnancy, labor and delivery, and the postpartum period. This isolated them from sources of support and advocacy.

Vietnamese participants reported, “Vietnamese people need to have a happy mindset so the baby can be born healthy" (Vietnamese FG 5, translated). Another participant shared how racism could negatively impact the mom and baby through the mindset: “I think there is a small impact if their relatives or themselves experience racism since the mother will not be happy and that will somewhat affect the baby” (Vietnamese FG 5, translated).

Despite the racism-related mental health concerns, most participants across focus groups stated they would not change their decision for future children based on the presence of racism, though some participants shared that racism would impact where they raised their children. A South Asian participant said,

“The only thing it may trigger in the future is geography, whether it’s high racism against my culture or race is a place I would want to bring up a child. But apart from that, whether I would want to have a child in this world based on racism, my race, is not a factor” (South Asian, FG7).

Representation and Advocacy for Appropriate Care

Participants across racial and ethnic groups emphasized the importance of culturally and racially concordant care. One Vietnamese participant shared that while many doctors refused to see her because her baby was estimated to be large, she was able to find a Vietnamese doctor who agreed to see her. Black participants reported how a non-Black physician stated that her son had jaundice, while her Black physician did not think the baby had jaundice by responding, ‘No. We’re yellow.’… I wonder how many times he’s had that conversation. But yeah, representation really does matter. It matters that we see ourselves reflected in the services that are provided to us in all walks of life” (Black, FG1).

Other Black participants warned that racism could still be present within the medical system, even if they had a Black doctor. One participant said,

“Every time I talked to somebody and I was just like, ‘I don’t think you all do this to White women.’ I can’t guarantee, but I feel in my body and my soul that this is something you’re doing and these are Black physicians who I cherish, but they’ve been steeped. I'll use that word in White medical education, just like me…. Even in the midst of having Black providers, there still ways for that racism to creep in there" (Black FG 3).

In addition to a discussion about representation, focus group participants saw the value of doulas and pregnancy groups for providing resources, guidance, and social support. A Middle Eastern participant emphasized the need to go beyond doula programs and anti-racist workshops, which she viewed as “band-aid solutions to this really big problem [racism].”

Multiple Vietnamese participants said that they were not aware of any pregnancy and birth support or programs. One participant said, “I only know to call 911.” (Vietnamese FG5, translated). Some participants (from the Latina and Middle Eastern focus groups) mentioned the need for increased access to abortion services and financial support services. The need for mental health services for pregnant women was also expressed. Women in the Middle Eastern and Latina focus groups discussed ways to increase empathy. A Latina participant recommended empathy courses for children that would also incorporate participation from parents. A Middle Eastern participant recommended that hospitals have a panel to listen to the community to understand “they bleed like you, and these are their needs, and this is where they came from."

Discussion

The current study provided nuanced insights about differences and similarities in the types of discrimination experienced during pregnancy and birthing from the perspectives of women from four different racial and ethnic groups. We apply Kramer and colleagues’ [27] conceptual framework to understand our findings by focusing on the social-contextual contributors to racial disparities. One of the two dimensions of the conceptual framework is the life course and health trajectory of the birthing person. Women in our study reported chronic experiences of racism even prior to their pregnancy and discussed the toll of this stress on their and their children’s well-being. The framework examines racism as a fundamental social determinant of health, systematically determining the risk, constraints, and opportunities across the life course.

Women in our study discussed their health environment and how their identities interacted with the broader social and cultural context to influence their healthcare interactions and daily life experiences. Spoken language and immigration status were more prominent factors influencing treatment for Latina women compared to Black women. The Muslim ban increased experiences of vulnerability and discrimination for Middle Eastern women in any public space they entered, including the healthcare setting. For some women, the geographic location where they chose to raise their children was impacted by whether they felt the area was welcoming to their cultural or racial identity.

In addition to the constraints of their environment, the women also highlighted opportunities or protective factors to support a positive birthing experience. Related to representation and advocacy for appropriate care, participants shared the importance of having healthcare providers that represented their racial/ethnic identity, while others pointed out the importance of addressing systemic racism within the medical system. Our study provides support for Kramer et al.’s [27] conceptual framework in highlighting the role of social determinants of health and the socio-spatial context in shaping the reproductive health of birthing people.

Several studies indicated that minoritized women are mistreated at greater rates in the clinical setting [6, 7, 31], from physicians yelling at patients [7] to withholding treatment plans [31]. This included another qualitative study conducted by the study team utilizing Twitter data to conduct a content analysis of tweets related to COVID-19 vaccines and race/ethnicity. That study had a theme of medical racism that included both subtle and overt examples [32]. In the current study, there was also a wide spectrum of perceptions and experiences described by the women that included both subtle and more overt experiences of racism. Our study participants described a nuanced perspective on mistreatment. For instance, as described above, one participant described how her physician remarked about her baby’s name. While this may have appeared subtle, she described being in the vulnerable position of having a vaginal examination. The combination of the physical proximity, the power dynamics of the physician–patient relationship, and the words culminated in a threatening situation for our participant, compounded by her perceived powerlessness. Chronic worry about racial discrimination has been found to partially explain Black-White disparities in preterm birth [33].

Medical mistrust was common among the study participants. Medical mistrust is defined as a lack of confidence in the intentions and work of medical systems and providers, stemming from a long history of racism in the healthcare system as well as personal experiences of discrimination and maltreatment [14, 34, 35]. Research has found medical mistrust negatively influences the utilization of healthcare services [34]. This was evidenced in our study by participants’ experiences in clinical settings, some who emphasized that they just wanted to “get in… and get out.” These findings align with the literature on the experiences of many Black women, whose mistrust of healthcare providers led to suspicion of medical treatment and a reluctance to seek care [14, 36]. A study among Hmong women and men, another ethnic and cultural minority group, found that medical trust generally stemmed from unfamiliarity with Western medicine, a fear of being studied, and, relevant to our study findings, negative experiences with providers [37]. A recent review of literature by Ho et al. [35] found a paucity of research on medical mistrust among Asian Americans, and especially Arab Americans. Our study adds to the research examining how anti-Arab and anti-Muslim climates affect healthcare experiences and medical mistrust. The study findings here suggest that while there are similarities across racial and ethnic groups, there are also unique concerns.

Literature on racism within the health care setting emphasizes the centrality of patient-centered care to improve patient experiences [16]. For instance, one study of Black patients and their non-Black physicians at a primary care clinic found that non-Black physicians’ racial biases, as well as Black patients’ history of racial discrimination, were associated with talk times in provider-patient interactions [38]. Other research shows that many Black women feel powerless when interacting with physicians, specifically gynecologists and obstetricians, and that they participate less in decision-making [14]. Participants in a study of Black women in the South reported avoiding health care or no longer asking questions during visits because healthcare providers dismissed or did not believe their health concerns [16]. Experiences of racialized pregnancy stigma cause reduced access to and quality of health care services, social support, and other resources [6, 13]. In contrast, women who had non-judgmental interactions with their providers felt more comfortable sharing relevant health information, such as risk factors important for predicting maternal and infant outcomes [13]. Prior studies have also emphasized that collaborative communication was associated with better medication adherence for patients without racially/ethnically concordant care [39].

Participants in our study emphasized particular aspects of their identities that influenced their perceived quality of health care. For example, Pacific Islander participants spoke about how appearing “lighter-skinned” or having a White or English-speaking advocate seemed to act as protective factors against the mistreatment of mothers of color. Other literature also found that participants perceived that lighter skin or higher education influenced the quality of healthcare they received [40]. Our study also emphasized the difficulty and vulnerability introduced by speaking a different language and the fear of being judged by physicians or other healthcare workers based on appearance. Prior research has found that language barriers often cause miscommunication between care providers and women and may increase the risk of negative obstetric outcomes [41].

Many participants in our study emphasized the importance of racially/ethnically concordant and culturally competent care, including having doctors, interpreters, and advocates like doulas of the same race. One Black participant highlighted how a Black physician was able to identify health issues better based on sharing the same race as the patient. Racial congruence is a key element to building trusting relationships between patients and providers, particularly as physicians of color tend to be more aware of and impacted by structural racism; thus, they are able to understand the struggles of patients and provide a sense of community in the medical environment [40]. However, participants also noted that racial and ethnic concordance does not guarantee anti-racism and should not be the only solution.

Prior research noted the disparity between the general population of Blacks, Latinxs, and American Indians or Alaska Natives and the number of physicians of that race/ethnicity [42]. As of 2019, Black individuals have 11 times fewer physicians and 6 times fewer OB/GYN options of the same race compared to their White counterparts [43]. Currently, there is no publicly available database that lists the race/ethnicity of maternal health providers in a patient’s area [43]. Our study helps to highlight the potential value of such a resource. This lack of representation is related to the sense of vulnerability addressed in our study between patient and provider.

However, some studies have found factors other than racial concordance to be more predictive of patient outcomes [44]. Factors such as age, education, and patient-centered communication influenced perceptions of similarity to their providers. Perceived personal similarity led to more trust in the physician, satisfaction with care, and stronger intention to adhere to recommendations [44]. Patient-centered behavior was central to the patient’s belief that the physician shared a common understanding of their health conditions [44].

Participants mentioned the systemic nature of racism within health care and highlighted the need to go beyond “band-aid” approaches. In recent years, there have been changes to the Medicaid program, which is the health insurer for 45% of total births in the country [45]. Many states have adopted support for different models of prenatal and delivery care, including support for interdisciplinary teams of health workers, doulas, and midwives and adopting person-centered models of care like group prenatal care and pregnancy medical homes. In addition, some state Medicaid policies have changed reporting requirements to increase data collection and disaggregate these data by race to understand disparities in maternal and birth outcomes for race-specific interventions [46]. These policy changes are consistent with some of the suggestions voiced by the participants.

Study Strengths and Limitations

Examining the lived experiences of pregnancy and birthing from women of different racial/ethnic backgrounds addresses a critical gap in order to better inform practices that can reduce maternal health disparities. However, our study had some limitations. For some focus groups, we encountered challenges in recruitment. For example, within the AAPI group, there were only two Pacific Islander women; yet these two women were considered leaders in their community and were able to provide an in-depth perspective. In addition, not all US areas were represented, as there were no participants from the Midwest. Our sample was also highly educated, with 75% of participants having a college or graduate degree, compared to 38% of the US population having a college degree, so they may not be representative of US women [47].

Conclusion

Pregnancy represents a critical time period in the life of a mother and her baby. Pregnancy and birth complications can have long-lasting effects on maternal and child mortality and morbidity. Despite this, little is known about the experiences of birthing women of color within the healthcare setting. Our study sheds light on some of the commonalities in experiences across racial and ethnic groups, as well as some of the unique experiences faced by women of distinct racial and ethnic groups. The women tell us of experiences within and outside of the healthcare setting that facilitates or inhibits feeling supported and heard during this time. These experiences varied by race, ethnicity, skin complexion, language, immigration status, and historical and current political context. Our study helps to provide a deeper understanding of the complexities of racism across several races/ethnicities and their impact on provider-patient interactions. Understanding the problems and solutions from the perspective of birthing women is a key process in creating an optimal and patient-centered healthcare environment.

Author Contribution

Thu T. Nguyen: funding acquisition, conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, review, and editing; Shaniece Criss: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, review, and editing; Melanie Kim: writing—original draft preparation, review, and editing; Monica M. De La Cruz: writing—original draft preparation, review, and editing; Nhung Thai: writing—original draft preparation, review, and editing; Junaid S. Merchant: review and editing; Yulin Hswen: review and editing; Amani M. Allen: review and editing; Gilbert C. Gee: review and editing; Quynh C. Nguyen, PhD: conceptualization, review, and editing.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities [R00MD012615 (TTN), R01MD015716 (TTN), and R01MD016037 (QCN)] and the National Library of Medicine [R01LM012849 (QCN)]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Data Availability

Focus group transcripts are housed with the corresponding and senior authors.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board (18–24593).

Consent to Participate

All study participants provided consent to participate in this study.

Consent for Publication

The authors consent to the publication of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Artiga S, Pham O, Orgera K, Ranji U. Racial disparities in maternal and infant health: an overview - issue brief [Internet]. KFF. 2020. Available from: https://www.kff.org/report-section/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-an-overview-issue-brief/. Accessed 2 Nov 2022.

- 2.Leonard SA, Main EK, Scott KA, Profit J, Carmichael SL. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity prevalence and trends. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;33:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powe NR, Cooper LA. Disparities in patient experiences, health care processes, and outcomes: the role of patient-provider racial, ethnic, and language concordance [Internet]. Commonw. Fund. 2004 [cited 2022 Sep 26]. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2004/jul/disparities-patient-experiences-health-care-processes-and.

- 5.Meints SM, Cortes A, Morais CA, Edwards RR. Racial and ethnic differences in the experience and treatment of noncancer pain. Pain Manag Future Med. 2019;9:317–334. doi: 10.2217/pmt-2018-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis D-A. Obstetric racism: the racial politics of pregnancy, labor, and birthing. Med Anthropol. 2019;38:560–573. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2018.1549389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, Rubashkin N, Cheyney M, Strauss N, et al. The giving voice to mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health. 2019;16:77. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molina RL, Tsai TC, Dai D, Soto M, Rosenthal N, Orav EJ, et al. Comparison of pregnancy and birth outcomes before vs during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2226531. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.26531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janevic T, Glazer KB, Vieira L, Weber E, Stone J, Stern T, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in very preterm birth and preterm birth before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e211816. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emeruwa UN, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Miller RS. Health care disparities in the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States: a focus on obstetrics. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2022;65:123–133. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masters GA, Asipenko E, Bergman AL, Person SD, Brenckle L, Moore Simas TA, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, access to care, and health disparities in the perinatal period. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;137:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altman MR, Eagen-Torkko MK, Mohammed SA, Kantrowitz-Gordon I, Khosa RM, Gavin AR. The impact of COVID-19 visitor policy restrictions on birthing communities of colour. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77:4827–4835. doi: 10.1111/jan.14991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehra R, Boyd LM, Magriples U, Kershaw TS, Ickovics JR, Keene DE. Black pregnant women “get the most judgment”: a qualitative study of the experiences of Black women at the intersection of race, gender, and pregnancy. Womens Health Issues Elsevier. 2020;30:484–492. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenthal L, Lobel M. Explaining racial disparities in adverse birth outcomes: unique sources of stress for Black American women. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:977–983. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenthal L, Lobel M. Gendered racism and the sexual and reproductive health of Black and Latina Women. Ethn Health Taylor Francis. 2020;25:367–392. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2018.1439896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson TM, Young Y-Y, Bass TM, Baker S, Njoku O, Norwood J, et al. Racism runs through it: examining the sexual and reproductive health experience of Black women in the south. Health Aff (Millwood). Health Aff. 2022;41:195–202. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Sacks TK. Invisible visits: Black middle-class women in the American healthcare system. New York, NY: Oxford Univ Press; 2019.

- 18.Jackson FM, Phillips MT, Hogue CJR, Curry-Owens TY. Examining the burdens of gendered racism: implications for pregnancy outcomes among college-educated African American women. Matern Child Health J. 2001;5:95–107. doi: 10.1023/A:1011349115711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nuru-Jeter A, Dominguez TP, Hammond WP, Leu J, Skaff M, Egerter S, et al. “It’s the skin you’re in”: African-American women talk about their experiences of racism. An exploratory study to develop measures of racism for birth outcome studies. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:29–39. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0357-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alhusen JL, Bower KM, Epstein E, Sharps P. Racial discrimination and adverse birth outcomes: an integrative review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61:707–720. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burris HH, Hacker MR. Birth outcome racial disparities: a result of intersecting social and environmental factors. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:360–366. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Catov JM, Flint M, Lee M, Roberts JM, Abatemarco DJ. The relationship between race, inflammation and psychosocial factors among pregnant women. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:401–409. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1522-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalmbach DA, Cheng P, Sangha R, O’Brien LM, Swanson LM, Palagini L, et al. Insomnia, short sleep, and snoring in mid-to-late pregnancy: disparities related to poverty, race, and obesity. Nat Sci Sleep. 2019;11:301–315. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S226291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meeks JR, Bambhroliya AB, Alex KM, Sheth SA, Savitz SI, Miller EC, et al. Association of primary intracerebral hemorrhage with pregnancy and the postpartum period. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e202769. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al Shamsi H, Almutairi AG, Al Mashrafi S, Al KT. Implications of language barriers for healthcare: a systematic review. Oman Med J. 2020;35:e122–e122. doi: 10.5001/omj.2020.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallace ME, Mendola P, Liu D, Grantz KL. Joint effects of structural racism and income inequality on small-for-gestational-age birth. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1681–1688. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kramer MR, Strahan AE, Preslar J, Zaharatos J, St Pierre A, Grant JE, et al. Changing the conversation: applying a health equity framework to maternal mortality reviews. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:609.e1–609.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.08.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams V, Boylan A-M, Nunan D. Qualitative research as evidence: expanding the paradigm for evidence-based healthcare. BMJ Evid-Based Med. 2019;24:168–169. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2018-111131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, Pölkki T, Utriainen K, Kyngäs H. Qualitative content analysis: a focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open. SAGE Publications; 2014;4:2158244014522633.

- 30.Pawluch, D. Qualitative Analysis, Sociology. In: Kempf-Leonard K, editors. Encyclopedia of Social Measurement. New York: Elsevier; 2005. pp 231–236.

- 31.Wang E, Glazer KB, Sofaer S, Balbierz A, Howell EA. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity: a qualitative study of women’s experiences of peripartum care. Womens Health Issues Elsevier. 2021;31:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2020.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Criss S, Michaels EK, Solomon K, Allen AM, Nguyen TT. Twitter fingers and echo chambers: exploring expressions and experiences of online racism using Twitter. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8:1322–1331. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00894-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braveman P, Heck K, Egerter S, Dominguez TP, Rinki C, Marchi KS, et al. Worry about racial discrimination: a missing piece of the puzzle of Black-White disparities in preterm birth? PLOS ONE. Public Libr Sci. 2017;12:e0186151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Tekeste M, Hull S, Dovidio JF, Safon CB, Blackstock O, Taggart T, et al. Differences in medical mistrust between Black and White Women: implications for patient–provider communication about PrEP. AIDS Behav. 2019;23:1737–1748. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2283-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho IK, Sheldon TA, Botelho E. Medical mistrust among women with intersecting marginalized identities: a scoping review. Ethn Health. Taylor & Francis. 2021;0:1–19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Hswen Y, Hawkins JB, Sewalk K, Tuli G, Williams DR, Viswanath K, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in patient experiences in the United States: 4-year content analysis of Twitter. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e17048. doi: 10.2196/17048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thorburn S, Kue J, Keon KL, Lo P. Medical mistrust and discrimination in health care: a qualitative study of hmong women and men. J Community Health. 2012;37:822–829. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9516-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hagiwara N, Penner LA, Gonzalez R, Eggly S, Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, et al. Racial attitudes, physician–patient talk time ratio, and adherence in racially discordant medical interactions. Soc Sci Med. 2013;87:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kolar SK, Wheldon C, Hernandez ND, Young L, Romero-Daza N, Daley EM. Human papillomavirus vaccine knowledge and attitudes, preventative health behaviors, and medical mistrust among a racially and ethnically diverse sample of college women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2:77–85. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Altman MR, Oseguera T, McLemore MR, Kantrowitz-Gordon I, Franck LS, Lyndon A. Information and power: women of color’s experiences interacting with health care providers in pregnancy and birth. Soc Sci Med. 2019;238:112491. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Binder P, Borné Y, Johnsdotter S, Essén B. Shared language is essential: communication in a multiethnic obstetric care setting. J Health Commun Taylor Francis. 2012;17:1171–1186. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.665421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Talamantes E, Henderson MC, Fancher TL, Mullan F. Closing the gap — making medical school admissions more equitable. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:803–805. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1808582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okpa A, Buxton M, O’Neill M. Association between provider-patient racial concordance and the maternal health experience during pregnancy. J Patient Exp. SAGE Publications Inc; 2022;9:23743735221077520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Street RL, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, Haidet P. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Markus AR, Andres E, West KD, Garro N, Pellegrini C. Medicaid covered births, 2008 through 2010, in the context of the implementation of health reform. Womens Health Issues Elsevier. 2013;23:e273–e280. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khanal P, McGinnis T, Zephyrin L. Tracking state policies to improve maternal health outcomes [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Sep 17]. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/tracking-state-policies-improve-maternal-health-outcomes.

- 47.Schaeffer K. 10 facts about today’s college graduates [Internet]. Pew Res. Cent. 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 12]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/04/12/10-facts-about-todays-college-graduates/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Focus group transcripts are housed with the corresponding and senior authors.

Not applicable.