Abstract

Researchers from different fields have studied the causes of obesity and associated comorbidities, proposing ways to prevent and treat this condition by using a common animal model of obesity to create a profound energy imbalance in young adult rodents. However, to confirm the harmful effects of consuming a high-fat and hypercaloric diet, it is common to include normolipidic and normocaloric control groups in the experimental protocols. This study compared the effect of three experimental diets described in the literature – namely, a high-fat diet, a high-fat and high-sucrose diet, and a high-fat and high-fructose diet – to induce obesity in C57BL/6 J mice with the standard AIN-93G diet as a control. We hypothesize that the AIN diet formulation is not a good control in this type of experiment because this diet promotes weight gain and metabolic dysfunctions similar to the hypercaloric diet. The metabolic data of animals fed the AIN-93G diet were similar to those of the high-calorie groups (development of steatosis and hyperlipidemia). However, it is important to emphasize that the group fed a high-fat diet had a higher percentage of total fat (p = 0.0002) and abdominal fat (p = 0.013) compared to the other groups. Also, the high-fat group responded poorly to glucose and insulin tolerance tests, showing a picture of insulin resistance. As expected, the intake of the AIN-93G diet promotes metabolic alterations in the animals like the high-fat formulations. Therefore, although this diet continues to be used as the gold standard for growth and maintenance, it warrants a reassessment of its composition to minimize the metabolic changes observed in this study, thus updating its fitness as a normocaloric model of a standard rodent diet.

Keywords: Obesity, Experimental animal models, Insulin resistance, Blood glucose, Metabolomics

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Composition of diet and texture can affect rodent food intake.

-

•

The AIN-93G diet promotes weight gain and liver fat deposits similar to HF-diet.

-

•

Could it be time to reformulate the standard AIN 93 Normocalorica diet?

1. Introduction

Obesity is a public health issue characterized by an imbalance in food intake and energy expenditure, which leads to accumulation of body fat (World Health Organization, 2014). This disease is growing worldwide at alarming levels, with overweight/obesity affecting 39% of the adult population and being a leading cause of death (World Health Organization, 2017). Many research groups worldwide have been working to elucidate the mechanisms by which obesity induces physiological dysfunctions has been done extensively using animal models (Nascimento et al., 2008). Although different types of animal models, mainly rodents, develop obesity from genetic mutations, inducing obesity via diet seems to be the most appropriate approach, especially considering that such a model should be as close as possible to humans (Kleinert et al., 2018).

Dietary habits have a substantial impact on health and consequently on various chronic complications. For example, eating meals containing generous portions of fruits and vegetables has been associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and low overall mortality (Bray et al., 2017). On the other hand, increased industrialization, technological development, globalization, and easy access to food have contributed to significant changes in dietary patterns, with increased consumption of caloric, low-cost food that are rich in saturated fat, sodium, and in some cases low in essential nutrients (Buettner et al., 2007).

While a protective effect in the vegetable-rich diet may be related to the amount of potassium and dietary fiber or to lower bioaccessibility of phosphorus in the protein fraction (Nascimento et al., 2008), ingesting diets high in fat and simple sugar is related to obesity, insulin resistance (IR), increased adipose tissue mass, development of inflammation, and atherosclerotic plaque formation (Kleinert et al., 2018). Studies also show that diets rich in simple carbohydrates contribute to metabolic abnormalities that are often accompanied by hypertriglyceridemia, which is associated with insulin resistance (Martins et al., 2015).

Hypercaloric and hyperlipidic diets are two of the most commonly used approaches in experimental studies due to their similarity to the eating habits currently observed in the population (Martins et al., 2015). Most diets used in the studies are either purified diets or diets modified by adding or removing ingredients to achieve a hyperlipidic and hypercaloric profile, as described by the American Institute of Nutrition (AIN-93) (Reeves et al., 1993). However, no standardization can be found for the formulation of obesogenic diets and the duration of experimental trials – variables that hinder comparing the results obtained between the studies (Buettner et al., 2007).

To assess the damage caused by the ingestion of these hyperlipidic and hypercaloric diets, a parallel normocaloric and normolipidic control group is often used. Since the AIN-93G diet is used as a basis to produce hyperlipidic diets, the use of its original formulation as a control seems to be something interesting. However, animals fed this standard diet have shown hepatic steatosis and hyperlipidemia, leading researchers to question whether this type of formulation would be the best option for use as a lean control group (Silva et al., 2008; Ataíde et al., 2009; Farias Santos et al., 2015). We hypothesize that ingestion of normocaloric diet AIN-93G promotes weight gain and metabolic dysfunctions similar to the hypercaloric diet, raising the possibility of using it as a control. As such, this study investigates the effects of the low-fat purified diet (AIN-93G) compared with different experimental hypercaloric diets on mice.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals and diet

Five-week-old C57BL/6 J male mice (n = 36) obtained from the Multidisciplinary Center for Biological Research of the Laboratory Animal Science (CEMIB) at UNICAMP were housed in individual cages under controlled temperature (21 ± 2 °C), humidity (60–70%), and light/dark cycle (12-12 h) conditions. The mice had free access to water and the standard commercial diet for one week. After acclimation, the animals were randomized into four experimental groups fed 12 weeks with the following diets: 1) AIN group: considered low-fat diet; 2) HF group: High-fat diet; 3) HFHS group: High-fat and High-sucrose diet; 4) HFHF group: High-fat and High-fructose diet. The experimental diets were formulated following the AIN-93G formulation, but some modifications in lipids source and carbohydrates were made to provide a high-fat and high-sugars diets. All diets formulations are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Diet composition (g/kg) per group.

| Ingredient | AIN | HF | HFHS | HFHF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casein | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 |

| Cornstarch | 452.5a | 172.5a | 112.5a | 112.5a |

| Dextrinized cornstarch | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 |

| Sucrose | 100 | 100 | 300 | – |

| Fructose | – | – | – | 300 |

| Soybean oil | 70 | 40 | 210 | 210 |

| Lard | – | 310 | – | – |

| Cellulose | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Mineral Mix | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Vitamin Mix | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| L-Cystine | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Choline bitartrate | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| TBHQ | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.014 |

| Calories (% provided by fat) | 15.8 | 58.3 | 40.2 | 40.2 |

| Calories (kcal)b |

3999.9 |

5399.9 |

4699.9 |

4699.9 |

|

Proximate composition | ||||

| AIN | HF | HFHS | HFHF | |

| Moisture (%) | 10.6 ± 0.19a | 5.4 ± 1.05b | 8.1 ± 0.25c | 3.5 ± 0.15d |

| Ash (%) | 2.3 ± 0.04b | 2.6 ± 0.06ab | 2.4 ± 0.03b | 2.7 ± 0.11a |

| Protein (%) | 12.2 ± 0.50b | 12.0 ± 0.97b | 13.6 ± 0.23ab | 14.1 ± 0.34a |

| Lipids (%) | 7.8 ± 0.34d | 32.7 ± 0.52a | 17.0 ± 0.39c | 21.1 ± 1.82b |

| Carbohydrate (%) | 67.1 | 47.3 | 59.0 | 58.56 |

AIN - composition recommended by the American Institute of Nutrition AIN-93G diet (normolipidic and normocaloric); HF - hyperlipidic/hypercaloric and hypercaloric diet with added lard; HFHS - hyperlipidic, hyperlipidic and hypercaloric diet with increased concentration of soybean oil and sucrose; HFHF - hyperlipidic and hyperlipidic, high-fat and hypercaloric diet with increased concentration of soybean oil and added fructose.

The carbohydrates ingredients in the diet were changed according to the addition of soybean oil; and soybean oil was changed according to the sucrose and fructose content.

Calorie content of the diet was estimated by protein and carbohydrate content multiplied by 4 and lipids by 9.

Food intake was controlled three times a week, calculating the difference between food supply and leftover feed in the cages. After this 12-week period, the mice fasted for 6 h, were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (300/30 mg/kg) and euthanatized by exsanguination (cardiac puncture). After blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture, some tissues (liver, heart, epididymal and inguinal adipose tissue, and brown adipose tissue) were weighed and stored for further analysis. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the National Council for Animal Experiment Control (CONCEA) and approved by the Ethics and Animal Research Committee of the University of Campinas (Brazil) (protocol 4592-1/2017 and 4474-1/2018).

2.2. Body composition

Body weight gain was assessed once a week and food intake three times a week. Body compositions were evaluated at week 9 of the experiment under light sedation (100 mg/kg ketamine hydrochloride, 10 mg/kg xylazine hydrochloride) using a computerized microtomography system (SkyScan 1178, Bruker, Massachusetts, EUA), as described by Doucette et al. (2015).

Image acquisition was performed according to the following parameters: 240 ms exposure time, 0.720 rotation step, 0.5 mm aluminum filter, 47 kV voltage source, 150 μA current source, 360° camera rotation, and 84.60 μm image pixel size. Scans lasted approximately 2 min and 40 s per animal. The 3D reconstructions were performed using the NRecon program (version 1.7.1.0, Bruker microCT, Massachusetts, EUA). Volume of interest (VOI) related to total fat was identified in the image by 605 slices above the acetabulum, while abdominal fat, our area of interest, was defined between the L1 to L6 vertebrae region. Fat distribution was illustrated using a single slice as a landmark, corresponding to the region between the L4 and L5 vertebrae in DataViewer (v1.5.4.6, Bruker microCT). A black and white scale was used to differentiate the muscle and fat regions, with the white border representing the subcutaneous fat deposits, and the more central white part representing the visceral fat deposits located in the abdominal region of the mice. Both the analysis and the illustrations were performed using the CT Analyzer (v1.16.4.1 Bruker microCT) based on method note MN_092.

2.3. Glucose homeostasis

Glucose tolerance was assessed at week 10 using an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) after 6 h of fasting. Fasting blood glucose was measured briefly and immediately followed by gavage of glucose solution (2 g/kg) at 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. Insulin sensitivity was assessed at week 11 using the insulin tolerance test (ITT) after 2 h of fasting. Fasting blood glucose was measured briefly and immediately followed by an insulin bolus (0.5 U/kg, Novolin R, Novo Nordisk Bagsvaerd, Denmark) at 15, 30, 45, and 60 min. Blood glucose of the mice in both tests was monitored by tests collected through the tail vein using a Free Lite G-Tech® glucometer (Infopia Co., Ltd; South Korea).

2.4. Biochemical parameters

Total cholesterol, triglycerides, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured by serum samples using LaborLab® commercial enzyme kits (LaborLab, Guarulhos/São Paulo, Brazil).

2.5. Liver lipid deposition

Total hepatic lipid content was assessed in accordance with Folch et al. (1957), followed by quantification of total cholesterol (TC) and triglycerides (TG) in lipid content extracted with Laborlab® commercial kits. Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) in hepatic tissue were quantified according to Ohkawa et al. (1979), using 1.1.3.3-tetraethoxypropane as a standard curve, with the results expressed as nmol MDA (malondialdehyde)/mg of tissue. For the histological evaluation of structural changes, liver samples were collected and fixed in 4% formalin (v/v). After dehydration in alcohol with different concentration gradients, the samples were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5–7 μm. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and classified according to Kleiner et al. (2005) using a Leica DMI 4000 B microscope (Switzerland). Histological evaluations were performed blindly (without identifying the group or diet) by a pathologist and a biologist.

2.6. Metabolic data

2.6.1. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS)

Hepatic metabolites were extracted according to the methodology proposed by Liu et al. (2018), with minor modifications. After 50 mg of liver tissue was weighed, 1 mL of extraction solution (chloroform-methanol: water, 2: 5: 2, v/v/v) was added for homogenization and the mixture was centrifuged at 17,741×g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatant aliquots (600 μL) were collected and transferred to previously identified microtubes, and then dried at 30 °C for 2 h and 30 min in a vacuum centrifuge before derivatization, which was conducted according to Liu et al. (2018). For each derivatized sample, 1 μL was injected in splitless mode into the HP 5890 Series II gas chromatography coupled to an HP 5970 Series Quadrupole Mass Selective Detector mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Chromatographic separation was performed using an HP5-MS capillary column (Agilent Technologies) with the following dimensions: 30 m length (plus 10 m guard column), 0.25 mm inner diameter, and 0.25 μm film thickness. Helium was used as carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.1 mL/min and injector temperature at 250 °C. Initial oven temperature was 60 °C, where it was held for 1 min and then increased to 310 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min. The mass spectrometer coupled to quadrupole mass analyzer was operated at 70 eV in the EI ionization source, and spectra were acquired over a 40–500 Da mass range at three scans per second. The quadrupole was operated at a temperature of 180 °C and the ionization source at 280 °C. A solvent cut-off of 5.9 min was applied. To monitor data quality and variation, a Quality Control (QC) sample was prepared to contain equal small aliquots of all other extracted samples. Moreover, the order of preparation and injection of the samples used was randomized to avoid systematic biases. Peak detection, alignment and integration were performed using XCMS software (Smith et al., 2006).

After processing the GC-MS data, a table was generated with the integrated area values for all the different variables extracted and then subjected to statistical analysis using the online platform MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (www.metaboanalyst.ca), according to Xia and Wishart (2016). To correct for any deviations in intensities that might occur between injections, the data were normalized by the sum (analogous to Total Ionic Current normalization) and the liver sample mass and scaled using Pareto scaling. Multivariate statistical analysis and univariate ANOVA were performed using the Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA), and variables with p <0.05 were considered significant. Data quality was assessed by observing the behavior of the instrumental replicas of the QC sample injections. Compound identity was attributed by NIST 2008 Mass Spectral Library and peak retention time using the AgilentFiehn GC/MS Metabolomics RTL Library version A.01.00 library.

2.6.2. Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS)

Hepatic metabolites were extracted in accordance with Wang et al. (2015), with minor modifications. Extracts were prepared using the same quantity of tissue and extraction solution as in the 2.6.1 section. The samples were then vortexed for 2 min, incubated for 30 min at 4 °C, and finally centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. A supernatant aliquot (600 μL) was collected from each sample, transferred to the corresponding microtubes, and dried in a vacuum centrifuge. Samples were then reconstituted in 250 μL (125 μL water and 125 μL acetonitrile) and centrifuged for 3 min at 13500 rpm. Two hundred microliters of each sample were transferred to their respective inserts. A QC sample was prepared as described above. LC-MS analyses were performed on a 1290 Infinity Liquid Chromatograph (Agilent Technologies). Chromatographic separation was performed using a 100 × 2.1 mm Poroshell 120 EC-C18 (Agilent) column and 2.7 μm particle size. Acetonitrile (phase B) and water with 0.1% formic acid (v/v) (phase A) were used as mobile phase in positive and negative mode. Gradient elution was applied at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min, and 3 μL of each sample was injected. The segmented gradient was applied as follows: from 0 to 6 min, 5–60% of B; from 6 to 8 min, 60–95% of B maintained for 5 min; from 13 to 16 min returning to initial conditions, maintaining it for 4 min. Mass spectra were acquired in centroid mode in the 100–1700 Da range using a 6550 QTOF mass spectrometer (Agilent). The samples were analyzed in both positive and negative ionization mode, according to the following instrumental parameters: VCap of 3,500 V for positive mode and 2,800 V for negative mode; 175 V fragment voltage, 60 V Skimmer voltage, 750 V OCT 1 RF Vpp, nebulizer gas temperature of 260 °C, sheath gas temperature of 300 °C, drying gas of 12 L/min and sheath gas flow rate of 12 L/min.

After loading the data files in the XCMS software, the obtained data matrix was normalized and scaled as described in section 2.6.1. Univariate ANOVA and multivariate data analysis were carried out using Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA), and variables with p-value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data normalization, scaling, and univariate and multivariate statistical analyses were performed using MetaboAnalyst 5.0. Data quality was assessed by observing the behavior of the instrumental replicas of the QC sample injections as described above. Statistically significant metabolites were annotated and identified by comparing the exact compound mass and fragmentation profile with the available databases (METLIN, Lipid Maps, and KEGG). Metabolite identity was assigned according to the Metabolomics Standards Initiative criteria classifications (Sumner et al., 2007; Salek et al., 2013).

2.7. Statistical analysis

The results obtained in the biological assay were expressed as mean ± standard error. Parametric results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA test for variance analysis, followed by Tukey's test for comparison of means, with 5% significance level. Non-parametric results were analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA, USA).

3. Results and discussion

Since the goal of a hypercaloric diet is to develop obesity, we evaluated the body weight gain between the normocaloric and hypercaloric groups but found no statistical difference (Table 2). The weight gain is the first point to be evaluated regarding using the standard AIN-93G diet as a control. Other studies have also reported no statistical difference between the weight of HF-fed mice compared to the normocaloric and normolipidic control diet group (Ramalho et al., 2017; Kakimoto and Kowaltowski, 2016; Klurfeld et al., 2021), probably due to its composition or texture.

Table 2.

Weight gain and dietary intake after 12 weeks.

| AIN | HF | HFHS | HFHF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial body weight (g) | 20.0 ± 1.00 | 19.9 ± 1.71 | 20.6 ± 1.33 | 20.6 ± 1.61 |

| Final body weight (g) | 29.0 ± 0.97 | 28.9 ± 1.02 | 28.7 ± 0.63 | 28.4 ± 0.63 |

| Total weight gain (g) | 9.03 ± 0.83 | 8.98 ± 0.86 | 8.12 ± 0.57 | 8.39 ± 0.35 |

| Total food intakea(g) | 344.6 ± 10.9a | 235.6 ± 5.98c | 328.6 ± 7.36ab | 308.6 ± 5.09b |

| Total energy intakea(kcal) | 1378.4 | 1272.2 | 1544.4 | 1544.4 |

AIN = standard diet group AIN-93G; HF = High Fat Diet Group; HFHS = High Fat High Sucrose Diet Group; HFHF = High Fat High Fructose Diet Group. Results are represented as mean ± standard error (n = 9 animals/group). Different letters on the same row mean statistical difference (p <0.05) between groups.

Total food and energy intake represent all food ingestion during the experimental protocol.

Body fat distribution is an important factor in understanding the relationship between obesity and metabolic disorders (Timmers et al., 2011). Despite the evidence that increased adipose tissue alone can offset inflammation, diet composition, especially the type of fat and carbohydrate used, may also be a key factor in triggering this process (Magne et al., 2010). Fig. 1 shows the qualitative assessment of abdominal fat composition (visceral and subcutaneous), a representative image obtained by microtomography of the mice in the different experimental groups. We clearly observe a higher accumulation of fat in the abdominal region in the HF group compared with the other experimental groups. Interestingly, the intake of AIN-93G, a diet used as a normocaloric standard, appears to deposit more fatty tissue than the HFHF diet. It was expected that consuming a diet rich in fructose would increase the accumulation of the fatty acid because of its impact on lipogenesis (Herman and Samuel, 2016); however, the control diet was worse than the HFHS diet. This result is another indication that the AIN-93G could not be a good option as a control diet.

Fig. 1.

X-ray images of abdominal fat obtained after microtomography of C57BL/6 J mice. (A) AIN group, (B) HF group, (C) HFHS group, and (D) HFHF group (n = 9/group). Images were collected in the same area of the lumbar region in all experimental groups. Areas indicated in white correspond to visceral and subcutaneous fats, while the areas in black correspond to muscle tissue of the animals.

The relationship between abdominal visceral fat accumulation and mortality is well established in the literature, as is the contribution of this type of fat deposition to developing insulin resistance and hypertension, both criteria for metabolic syndrome (Nauli and Matin, 2019; Ribeiro Filho et al., 2006; Wajchenberg, 2000). It is unquestionable that the higher lipid intake in the HF diet contributed to the higher lipid absorption compared with the other groups. But the differences among AIN, HFHS, and HFHF in visceral abdominal fat deposits observed in the images are more subtle, although both hypercaloric diets provided 2.2 and 2.7 times more lipids than AIN, respectively.

Studies show that many variables contribute to weight gain; in our study, however, the mice showed no differences in the amount of dietary intake, except the HF group, which ingested more calories than HFHS and HFHF (Table 2). Besides, the animals received no stimulus to engage in physical activity, indicating that diet composition, digestion, and nutrient absorption had a greater impact on the observed results.

We observed no difference in fasting glucose between the AIN group and the mice fed high-fat diets, which does not represent that the animals do not have alterations in carbohydrate metabolism since we observed a similar metabolic profile between the groups. To elucidate the impact of the diets on the serum lipid profile, we evaluated serum TC and TG and found that the intake of high-fat diets did not change the mice's TG level when compared to the control diet (Table 3). This is another point that highlights the doubt about using the AIN diet as a control because there are expected differences in the lipid profile and glucose tolerance among the lean group compared to the fat group. Therefore, to elucidate the real impact of this diet on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism alterations, an experiment comparing the intake of the AIN diet and other types of normocaloric and normolipidic diets should be performed. It is important to emphasize that the HF group had the highest TC level, followed by AIN and HFHS, corroborating the study by Dias et al. (2014), which observed that saturated fat sources might not be significantly associated with increased blood lipid levels. Moreover, Muniz et al. (2019) noted that although a rich lard diet promotes weight gain, dyslipidemia was observed in the animals only when cholesterol was added to the diet.

Table 3.

Serum and hepatic lipid profile of C57BL/6 J mice according to experimental group.

| AIN | HF | HFHS | HFHF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum lipid profile | ||||

| TG (mg/dL) | 61.56 ± 5.79 | 50.97 ± 1.41 | 53.63 ± 3.47 | 52.26 ± 4.18 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 148 ± 8.24ab | 152.8 ± 5.32b | 139.2 ± 10.5ab | 119 ± 7.07a |

| Hepatic lipid profile | ||||

| Total lipids (%) | 6.8 ± 0.47ab | 8.5 ± 1.01ab | 10.8 ± 0.92a | 6.6 ± 0.80b |

| TG (mg/g) | 13.8 ± 0.81 | 12.7 ± 0.54 | 13.3 ± 0.63 | 13.3 ± 0.67 |

| TC (mg/g) | 5.1 ± 0.78 | 3.6 ± 0.52 | 3.8 ± 0.41 | 3.7 ± 0.40 |

| TBARS (nmol MDA/mg of tissue) | 0.09 ± 0.035 | 0.08 ± 0.013 | 0.08 ± 0.005 | 0.08 ± 0.017 |

AIN = standard diet group AIN-93G; HF = High Fat Diet Group; HFHS = High Fat High Sucrose Diet Group; HFHF = High Fat High Fructose Diet Group; TG = Triglycerides; TC = Total Cholesterol. Results are represented as mean ± standard error (n = 9 animals/group). Different letters on the same row mean statistical difference (p <0.05) between groups.

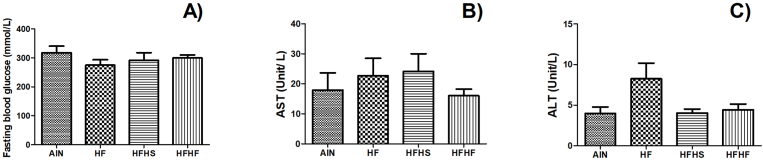

Fructose intake has been associated with obesity due to its differential intestinal absorption compared with glucose, since the transporter (GLUT-5) is regulated according to fructose bioaccessibility (Stanhope et al., 2018; Noelting and DiBaise, 2015). Besides, the increasing use of high fructose corn syrup by the food industry has raised the interest of the scientific community to elucidate the real impact of this high fructose intake on health. In the present study, adding fructose to the high-fat diet, at 25.5% of energy content, did not promote changes in body weight gain, serum, and hepatic TG levels, or fasting glucose when compared with the other HF groups (Table 2, Table 3, Fig. 2). However, HFHF intake exhibited lower serum cholesterol compared to HF (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Effects of diets on (A) fasting glucose, (B) aspartate aminotransferase, and (C) alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in serum of C57BL/6 J mice. Results are represented as mean ± standard error (n = 9/group). Different letters represent statistical difference (Anova followed by Tukey's test; p <0.05).

Velázquez et al. (2019) showed the impact of prolonged consumption of a high-fat diet in the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. In the present study, however, eating high-fat diet for a 12-week period did not alter some liver markers, such as plasma transaminases (alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase), when compared with the normocaloric and normolipidic control groups (Fig. 2B and C). We observed no changes in the hepatic total lipid content (Table 3 and Fig. 3). In agreement, it is observed in the literature that the intake of saturated fatty acids can upregulate non-alcoholic liver disease pathways, contributing to intrahepatic triglyceride accumulation in the tissue and the development of insulin resistance (Parks et al., 2017).

Fig. 3.

Microscopic evaluation of lipid accumulation and hepatic damage. Qualitative analysis of ballooning and steatosis between the animals (n = 9/group).

Qualitative histological assessment of the liver tissue (Fig. 3, Fig. 4) showed incidence of hepatocytes ballooning in all experimental groups – one of the first histological findings of the lesion, although it is reversible. However, only the AIN, HF, and HFHS diets showed incidence of hepatic steatosis. These findings confirm the damaging effect of AIN diet on lipid accumulation in the liver. It also highlights a conflicting point about the established pattern of the AIN diet, considered normocaloric and normolipidic that also caused fatty liver in the mice.

Fig. 4.

Hematoxilin and Eosin (H&E) staining of a representative histological liver evaluation (n = 9/group). Magnification: 200x and 400x.

Among obesity-related metabolic disorders, insulin resistance is the most common (Hegarty et al., 2003). High-fat diets impairs insulin response likely by reducing fat oxidation, which results in lipid accumulation, increasing macrophage infiltration and releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines that contribute to reduced insulin signaling (Hirabara et al., 2010; Nauli and Matin, 2019).

Among the three high-calorie diets used in the present study, the diet prepared with 31% lard had the worst response (although the difference was not statistically significant), indicating the development of insulin resistance compared with the HFHS and HFHF groups (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT – A and B) and insulin tolerance test (ITT – C and D) in C57BL/6 J mice fed different diets. OGTT – fasting mice for 6 h and ITT fasting for 2 h. Data expressed as mean ± standard error (n = 9/group). Different letters represent the statistical difference (Anova followed by Tukey's test; p <0.05).

Studies show that an HF diet decreases insulin sensitivity in the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue of rodents (Turner et al., 2007). Our data, however, show that not only the calories but also diet composition is responsible for insulin resistance development. Regarding lipid content in liver tissue, we observed a statistically significant difference only between the HFHS and HFHF groups (Tabela 3).

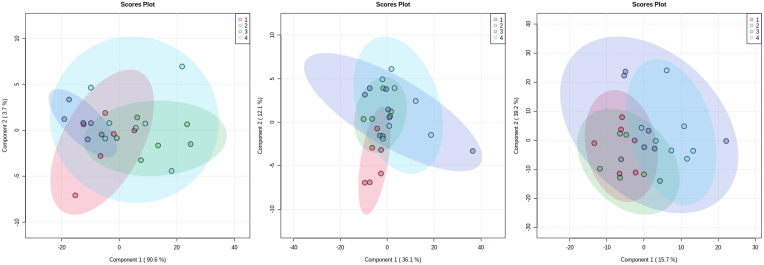

To verify if the intake of the different experimental diets would promote metabolic changes in the mice, we investigated the metabolic profile of the groups by GC-MS and LC-MS using liver samples (Fig. 6). We built PLS-DA models for each analysis (GC-MS and LC-MS) and performed univariate statistical analyses (Fig. 7). We carried out a metabolic pathway analysis by itemizing the metabolites in Fig. 8, listed in Table 4. We noted that the metabolic pathways found were classified according to exact mass and database search (level 3) and according to their mass and fragmentation profile (level 2) (Table 4). These data associated with body weight gain provide relevant information on the effects of the AIN formulation on the mice's health, since they showed a similar metabolic profile to animals fed the hypercaloric diet. Based on the data observed in the metabolic profile analysis, we believe that a dietary strategy for the lean control groups could be the use of commercial diets, with different composition and normocaloric profile.

Fig. 6.

Liver metabolomic analysis of C57BL/6 J mice fed different experimental diets. AIN (1-black) = standard diet group AIN-93G; HF (2-red) = High Fat diet group; HFHS (3-dark blue) = diet group High Fat High Sucrose; HFHF (4-light blue) = High Fat High Fructose diet group; CHOW (5-green) = data not shown (n = 9/group). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 7.

Analysis of the main liver component of C57BL/6 J mice fed different diets. (A) PLSDA graph for GC-MS data analysis of all groups, (B) PLSDA graph for LC-MS positive mode data analysis of all groups, and (C) PLSDA graph for LC-MS negative mode data analysis of all groups, where 1: AIN-93G; 2: HF diet; 3: HFHS diet; and 4: HFHF diet (n = 9/group).

Fig. 8.

Pathway Analysis of C57BL/6 J mice fed different experimental diets showing impacted metabolic pathways.

Table 4.

Metabolites found in the different groups by GC-MS and LC-MS analysis.

| Name | RT (s) | mz (Da) | Adduct | p-value | Source | Compound | Formula | Level of identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M165T38 | 38 | 165.0429 | [M-H]- | 0.006522 | LCMS (-) | Homocysteinesulfinic acid | C4H9NO4S | 3 |

| M462T60 | 60 | 462.0688 | [M-H]- | 0.021363 | LCMS (-) | Adenylosuccinate | C14H18N5O11P | 3 |

| M1030T264 | 264 | 1029.586 | [2 M-H]-515.298 | 0.004425 | LCMS (-) | Taurocholic acid | C26H45NO7S | 3 |

| M534T460 | 460.1824 | 534.296 | [M+K]+ 495.332 | 0.001767 | LCMS (+) | LysoPC(16:0) | C40H80NO8P | 3 |

| M570T426 | 426.3977 | 570.2827 | [M+H]+569.275 | 0.002561 | LCMS (+) | PS(22:6/0:0) | C28H44NO9P | 3 |

| M464T60 | 59.85675 | 464.0817 | [M+H] | 0.000646 | LCMS (+) | Adenylosuccinate | C14H18N5O11P | 3 |

| M387T364 | 363.673 | 387.1803 | [M+H] | 0.000755 | LCMS (+) | Isogingerenone B | C22H26O6 | 3 |

| M225T311 | 311.3911 | 225.149 | [M+H] | 0.003404 | LCMS (+) | 13-Oxo-9,11-tridecadienoic acid | C13H20O3 | 3 |

| M81T580 | 580.2942 | 80.51164 | N/A | 0.018187 | GCMS | [5951] L-serine 1 [9.706] | C3H7NO3 | 2 |

| M101T952 | 951.7138 | 101 | N/A | 8.87E-06 | GCMS | [754] glycerol 1-phosphate [16.056] | C3H9O6P | 2 |

| M100T1474 | 1473.879 | 100.215 | N/A | 0.004091 | GCMS | [6255] maltose 1 [24.702] | C12H22O11 | 2 |

The most important strength of our study is that we could prove that AIN intake promotes similar metabolic alterations to the consumption of a hyperlipidic and hypercaloric diet. On the other hand, the study limitation was missing a group fed with a commercial (chow) diet to demonstrate differences in weight gain.

4. Conclusion

Although the AIN formulation had been revised in recent years, our findings suggest that further reformulation might be needed, focusing on the ingredients selected to formulate the diet. Several research groups in the area have already used commercial feed as a control in obesity experiments, but we believe that formulating a more precise diet concerning the ingredients used would facilitate comparisons in the observed effects. The ingredients used to manufacture commercial diets are very different from those used in formulating experimental diets.

In addition to diet composition, consistency may be an important parameter influencing the results. Finally, the data present in this study suggests that the AIN diet might not be the best control diet to be used in diet-induced obesity protocol. Therefore, we suggested that new diet formulations should be designed to be used as a control (normocaloric and normolipidic) and also perform new protocols to compare the effects of AIN-93G intake and some commercial fed on animals' carbohydrate and lipid metabolism.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lais Marinho Aguiar: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Manuscript Writing. Carolina Soares de Moura: Investigation. Cintia Reis Ballard: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Aline Rissetti Roquetto: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Juliana Kelly da Silva Maia: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Gustavo H.B. Duarte: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Larissa Bastos Eloy da Costa: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Adriana Souza Torsoni: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Jaime Amaya-Farfan: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Mário R. Maróstica Junior: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Cinthia Baú Betim Cazarin: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Obesity and Comorbidity Research Center of the Biology Institute, UNICAMP for the use of the microtomography computerized system (SkyScan 1178, Bruker) – FAPESP multiuser equipment. This study was partially funded by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES), financing code 001. LMA and ARR acknowledges CNPq for the scholarship grant (130635) and (140542/2015-9), respectively. MRMJ acknowledges CNPq (403328/2016-0; 301496/2019-6) and FAPESP (2015/50333-1; 2018/11069-5; 2015/13320-9, 2019/13465-8) and CBBC acknowledges FAEPEX-UNICAMP (Grant 2979/17) for the financial support. CSM acknowledges FAPESP 16/06630-4 for the PhD fellowship. MRMJ acknowledges Red Iberomericana de Alimentos Autoctonos Subutilizados (ALSUB-CYTED, 118RT0543). The authors thank Espaço da Escrita – Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa - UNICAMP - for the language services provided.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Ataíde T.D.R., De Oliveira S.L., Da Silva F.M., Vitorino Filha L.G.C., Tavares M.C.D.N., Sant’ana A.E.G. Toxicological analysis of the chronic consumption of diheptanoin and triheptanoin in rats. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2009;44:484–492. [Google Scholar]

- Bray G.A., Kim K.K., Wilding J.P.H. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes. Rev. 2017;18:715–723. doi: 10.1111/obr.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buettner R., Schölmerich J., Bollheimer L.C. High-fat diets: modeling the metabolic disorders of human obesity in rodents. Obesity. 2007;15:798–808. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias C.B., Garg R., Wood L.G., Garg M.L. Saturated fat consumption may not be the main cause of increased blood lipid levels. Med. Hypotheses. 2014;82:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2013.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucette C.R., Horowitz M.C., Berry R., Macdougald O.A., Anunciado-Koza R., Koza R.A., Rosen C.J. A high fat diet increases bone marrow adipose tissue (MAT) but does not alter trabecular or cortical bone mass in C57BL/6J mice. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015;230:2032–2037. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farias Santos J., Suruagy Amaral M., Lima Oliveira S., Porto Barbosa J., Rego Cabral C., Jr., Sofia Melo I., Bezerra Bueno N., Duarte Freitas J., Goulart Sant'ana A., Rocha Ataide T. Dietary intake of ain-93 standard diet induces fatty liver with altered hepatic fatty acid profile in Wistar rats. Nutr. Hosp. 2015;31:2140–2146. doi: 10.3305/nh.2015.31.5.8597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J., Lees M., Sloane Stanley G.H. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty B.D., Furler S.M., Ye J., Cooney G.J., Kraegen E.W. The role of intramuscular lipid in insulin resistance. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2003;178:373–383. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman M.A., Samuel V.T. The sweet path to metabolic demise: fructose and lipid synthesis. Trends Endocrinol. Metabol. 2016;27:719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirabara S.M., Curi R., Maechler P. Saturated fatty acid-induced insulin resistance is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2010;222:187–194. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakimoto P.A., Kowaltowski A.J. Effects of high fat diets on rodent liver bioenergetics and oxidative imbalance. Redox Biol. 2016;8:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner D.E., Brunt E.M., Van Natta M., Behling C., Contos M.J., Cummings O.W., Ferrell L.D., Liu Y.C., Torbenson M.S., Unalp-Arida A., Yeh M., Mccullough A.J., Sanyal A.J. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313–1321. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinert M., Clemmensen C., Hofmann S.M., Moore M.C., Renner S., Woods S.C., Huypens P., Beckers J., De Angelis M.H., Schurmann A., Bakhti M., Klingenspor M., Heiman M., Cherrington A.D., Ristow M., Lickert H., Wolf E., Havel P.J., Muller T.D., Tschop M.H. Animal models of obesity and diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018;14:140–162. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klurfeld D.M., Gregory J.F., Iii, Fiorotto M.L. Should the AIN-93 rodent diet formulas be revised? J. Nutr. 2021;151:1380–1382. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F.-J., Liang D., Miao L.-Y., Li P., Li H.-J. Liver-specific metabolomics characterizes the hepatoprotective effect of saponin-enriched Celosiae Semen extract on mice with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Funct.Foods. 2018;42:185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Magne J., Mariotti F., Fischer R., Mathe V., Tome D., Huneau J.F. Early postprandial low-grade inflammation after high-fat meal in healthy rats: possible involvement of visceral adipose tissue. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2010;21:550–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins F., Campos D.H.S., Pagan L.U., Martinez P.F., Okoshi K., Okoshi M.P., Padovani C.R., Souza A.S.D., Cicogna A.C., Oliveira-Junior S.A.D. High-fat diet promotes cardiac remodeling in an experimental model of obesity. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2015;105:479–486. doi: 10.5935/abc.20150095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muniz L.B., Alves-Santos A.M., Camargo F., Martins D.B., Celes M.R.N., Naves M.M.V. High-lard and high-cholesterol diet, but not high-lard diet, leads to metabolic disorders in a modified dyslipidemia model. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2019;113:896–902. doi: 10.5935/abc.20190149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento A.F., Sugizaki M.M., Leopoldo A.S., Lima-Leopoldo A.P., Luvizotto R.A., Nogueira C.R., Cicogna A.C. A hypercaloric pellet-diet cycle induces obesity and co-morbidities in Wistar rats. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2008;52:968–974. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302008000600007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauli A.M., Matin S. Why do men accumulate abdominal visceral fat? Front. Physiol. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noelting J., Dibaise J.K. Mechanisms of fructose absorption. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2015;6 [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa H., Ohishi N., Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1979;95:351–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks E., Yki-Järvinen H., Hawkins M. Out of the frying pan: dietary saturated fat influences nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2017;127:454–456. doi: 10.1172/JCI92407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho L., Da Jornada M.N., Antunes L.C., Hidalgo M.P. Metabolic disturbances due to a high-fat diet in a non-insulin-resistant animal model. Nutr. Diabetes. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/nutd.2016.47. e245-e245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves P.G., Nielsen F.H., Fahey G.C., Jr. AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J. Nutr. 1993;123:1939–1951. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.11.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro Filho F.F., Mariosa L.S., Ferreira S.R.G., Zanella M.T. Gordura visceral e síndrome metabólica: mais que uma simples associação. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2006;50:230–238. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302006000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salek R.M., Steinbeck C., Viant M.R., Goodacre R., Dunn W.B. The role of reporting standards for metabolite annotation and identification in metabolomic studies. GigaScience. 2013;2 doi: 10.1186/2047-217X-2-13. 13-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva M.A.F.D., Ataide T.D.R., Oliveira S.L.D., Sant'ana A.E.G., Cabral Júnior C.R., Balwani M.D.C.L.V., Oliveira F.G.S.D., Santos M.C. Efeito hepatoprotetor do consumo crônico de dieptanoína e trieptanoína contra a esteatose em ratos. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2008;52:1145–1155. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302008000700011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.A., Want E.J., O'maille G., Abagyan R., Siuzdak G. XCMS: processing mass spectrometry data for metabolite profiling using nonlinear peak alignment, matching, and identification. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:779–787. doi: 10.1021/ac051437y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanhope K.L., Goran M.I., Bosy-Westphal A., King J.C., Schmidt L.A., Schwarz J.-M., Stice E., Sylvetsky A.C., Turnbaugh P.J., Bray G.A., Gardner C.D., Havel P.J., Malik V., Mason A.E., Ravussin E., Rosenbaum M., Welsh J.A., Allister-Price C., Sigala D.M., Greenwood M.R.C., Astrup A., Krauss R.M. Pathways and mechanisms linking dietary components to cardiometabolic disease: thinking beyond calories. Obes. Rev. 2018;19:1205–1235. doi: 10.1111/obr.12699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner L.W., Amberg A., Barrett D., Beale M.H., Beger R., Daykin C.A., Fan T.W.M., Fiehn O., Goodacre R., Griffin J.L., Hankemeier T., Hardy N., Harnly J., Higashi R., Kopka J., Lane A.N., Lindon J.C., Marriott P., Nicholls A.W., Reily M.D., Thaden J.J., Viant M.R. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis chemical analysis working group (CAWG) metabolomics standards initiative (MSI) Metabolomics. 2007;3:211–221. doi: 10.1007/s11306-007-0082-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers S., De Vogel-Van Den Bosch J., De Wit N., Schaart G., Van Beurden D., Hesselink M., Van Der Meer R., Schrauwen P. Differential effects of saturated versus unsaturated dietary fatty acids on weight gain and myocellular lipid profiles in mice. Nutr. Diabetes. 2011;1 doi: 10.1038/nutd.2011.7. e11-e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner N., Bruce C.R., Beale S.M., Hoehn K.L., So T., Rolph M.S., Cooney G.J. Excess lipid availability increases mitochondrial fatty acid oxidative capacity in muscle: evidence against a role for reduced fatty acid oxidation in lipid-induced insulin resistance in rodents. Diabetes. 2007;56:2085–2092. doi: 10.2337/db07-0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez K.T., Enos R.T., Bader J.E., Sougiannis A.T., Carson M.S., Chatzistamou I., Carson J.A., Nagarkatti P.S., Nagarkatti M., Murphy E.A. Prolonged high-fat-diet feeding promotes non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and alters gut microbiota in mice. World J. Hepatol. 2019;11:619–637. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i8.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajchenberg B.L. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: their relation to the metabolic syndrome. Endocr. Rev. 2000;21:697–738. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.6.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.Y., Luo J.P., Chen R., Zha X.Q., Pan L.H. Dendrobium huoshanense polysaccharide prevents ethanol-induced liver injury in mice by metabolomic analysis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015;78:354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . WHO Document Production Services; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. World Health Statistics 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2017. Noncommunicable Diseases Progress Monitor. (Geneva, Switzerland) [Google Scholar]

- Xia J., Wishart D.S. Using MetaboAnalyst 3.0 for comprehensive metabolomics data analysis. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 2016;55(14 10 1) doi: 10.1002/cpbi.11. 14 10 91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.