Abstract

In experimental visceral leishmaniasis, in which the tissue macrophage is the target, in vivo responsiveness to conventional chemotherapy (pentavalent antimony [Sb]) requires a T-cell-dependent mechanism. To determine if this mechanism involves gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-induced activation and/or specific IFN-γ-regulated macrophage leishmanicidal mechanisms (generation of reactive nitrogen or oxygen intermediates, we treated gene-deficient mice infected with Leishmania donovani. In IFN-γ gene knockout (GKO) mice, Sb inhibited but did not kill intracellular L. donovani (2% killing versus 76% in controls). Sb was active (>94% killing), however, in both inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) knockout (KO) and respiratory burst (phagocyte oxidase)-deficient chronic granulomatous disease (X-CGD) mice. Sb's efficacy was also maintained in doubly deficient animals (X-CGD mice treated with an iNOS inhibitor). In contrast to Sb, amphotericin B (AmB) induced high-level killing in GKO mice; AmB was also fully active in iNOS KO and X-CGD animals. Although resolution of L. donovani infection requires iNOS, residual visceral infection remained largely suppressed in iNOS KO mice treated with Sb or AmB. These results indicate that endogenous IFN-γ regulates the leishmanicidal response to Sb and achieves this effect via a pathway unrelated to the macrophage's primary microbicidal mechanisms. The role of IFN-γ is selective, since it is not a cofactor in the response to AmB. Treatment with either Sb or AmB permits an iNOS-independent mechanism to emerge and control residual intracellular L. donovani infection.

In the susceptible host, control of visceral leishmaniasis revolves around the state of activation of the tissue mononuclear phagocyte. Unstimulated resident macrophages of the liver, spleen, and bone marrow, the target cells in this disseminated intracellular infection, initially support parasite replication. However, if an experimentally well-characterized T-cell (primarily Th1-cell)-dependent, multicytokine-mediated response emerges (reviewed in reference 14), the same macrophages and tissue-homing blood monocytes develop sufficient leishmanicidal activity to control and largely resolve the infection without chemotherapy. Of several key antileishmanial cytokines (14), gamma interferon (IFN-γ) plays a particularly prominent macrophage-activating role (33, 40, 45) which extends to the priming of macrophages to secrete leishmanicidal molecules. In experimental infection, the latter include inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)-derived reactive nitrogen intermediates (RNI) and respiratory burst-derived reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) (12, 20, 24, 27, 30, 40).

Prompt, unimpeded activity of this or a similar immune response may also explain why the majority of otherwise healthy individuals infected with visceralizing Leishmania organisms remain asymptomatic or spontaneously resolve oligosymptomatic disease without treatment (reviewed in reference 14). In patients who do develop a fully established infection (kala-azar) and require therapy, this T-cell-dependent mechanism has failed by definition. Nevertheless, in this setting, two observations suggest that even though suboptimally developed or actively suppressed (14, 17) T cells still serve the infected host by regulating responsiveness to conventional antileishmanial chemotherapy, pentavalent antimony (Sb). First, while Sb exerts potent microbicidal effects in Leishmania donovani-infected euthymic mice (15), it is entirely inactive in T-cell-deficient athymic (nude) mice (21). Second, although Sb cures >90 to 95% of immunocompetent infected individuals with in the Mediterranean, as many as 40 to 50% or more of the CD4 cell-depleted patients from the same region with AIDS-related kala-azar fail to show an initial response to Sb treatment (reviewed in reference 13).

Although these latter two observations point to endogenous host mechanisms which regulate the response to Sb in visceral leishmaniasis, it is worth noting that responses to amphotericin B (AmB), now an increasingly used alternative antileishmanial agent (36), differ. For example, AmB is fully active in nude mice (18) and limited data suggest satisfactory initial effects in AIDS-related kala-azar (13).

To extend related analyses of both immunochemotherapy and immunodeterminants of the host response to antileishmanial chemotherapy (15, 21, 38), this report focuses on the parasitized target cell (the visceral macrophage) and examines the effects of the IFN-γ-induced activated state and IFN-γ-regulated macrophage leishmanicidal mechanisms on the outcome of experimental infections treated with Sb or AmB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

IFN-γ gene knockout (GKO) mice, bred on a C57BL/6 background, were obtained from Charles Rivers Laboratories (Wilmington, Mass.) (40). Respiratory burst-deficient gp91phox−/− (X-linked chronic granulomatous disease [X-CGD]) mice with a targeted disruption of the gp91phox subunit of the NADPH-oxidase complex (phox) (20) were derived from a C57BL/6 × 129/Sv background and provided as breeders by M. Dinauer (Indiana University Medical Center, Indianapolis). Normal C57BL/6 mice (Charles Rivers Laboratories) were used as controls for both GKO and X-CGD mice (20). iNOS−/− knockout (KO) mice (C57BL/6 × 129/Sv) (7) were provided by C. Nathan (Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, N.Y.); wild-type+/+ littermates served as controls (20). Mice were 8 to 15 weeks old when challenged with L. donovani; both males and females were used in a random fashion, except for control C57BL/6 mice (all female).

Visceral infection.

Groups of 4 to 6 mice were injected via the tail vein with 1.5 × 107 hamster spleen-derived L. donovani amastigotes (1 Sudan strain) (20). Visceral infection was monitored microscopically by using Giemsa-stained liver imprints in which liver parasite burdens (in Leishman-Donovan units [LDU]) were determined by multiplying the number of amastigotes per 500 cell nuclei by the liver weight (micrograms) (20).

Antileishmanial treatment.

Two weeks after infection (day 0), liver parasite burdens were determined and mice then received no treatment, a single intraperitoneal injection of Sb, or three alternate-day intraperitoneal injections of AmB as in previous studies (15, 18, 21). Sb (sodium stibogluconate [Pentostam]; Wellcome Foundation Ltd., London, United Kingdom) was given on day 0 at either 500 or 100 mg/kg (15). Suboptimal-dose Sb (100 mg/kg) was used to detect possible subtle defects in the response to treatment. AmB (Gensia Laboratories Ltd., Irvine, Calif.) was used at an optimal dose of 5 mg/kg and given on days 0, +2, and +4 (18). On day +7 (1 week after treatment was started), mice were sacrificed and liver parasite burdens were measured. Day +7 and day 0 parasite burdens were compared to determine percent parasite killing (15); differences between mean values were analyzed by a two-tailed Student t test.

In separate experiments designed to test the durability of the response to treatment, groups of iNOS KO mice infected 2 weeks earlier were treated with Sb or AmB as described above and liver parasite burdens were determined at both 1 and 9 weeks after treatment. In these experiments, a smaller challenge inoculum (107 amastigotes) was used because of the enhanced susceptibility of iNOS KO mice to L. donovani (20).

AG treatment.

In some experiments, X-CGD mice were also treated continuously with aminoguanidine (AG; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), which was used as an iNOS inhibitor (20, 40). Starting 1 day after infection and continuing for the next 3 weeks (up to and throughout treatment with Sb or AmB), 2.5% (wt/vol) AG was present in the animals' acidified drinking water, which was changed twice weekly; controls received acidified water alone (40).

RESULTS

Treatment response of IFN-γ GKO mice.

Sensitized T cells are required for leishmanial antigen-induced secretion of IFN-γ, a cytokine which activates macrophages in vitro and in vivo to kill L. donovani (12, 14). In a prior study carried out to determine if low levels of endogenous IFN-γ could explain why L. donovani-infected, T-cell-deficient nude mice failed to respond to Sb (21), euthymic animals were treated with anti-IFN-γ serum and then with Sb (16). We anticipated that the result would be inhibition of Sb's activity since IFN-γ and Sb act synergistically in vivo (15, 38), and providing nude mice with exogenous IFN-γ partially restored Sb's efficacy (21). However, the leishmanicidal response to Sb in anti-IFN-γ serum-treated normal mice was not impaired (16).

The subsequent availability of GKO mice, which proved considerably more susceptible to L. donovani than anti-IFN-γ serum-treated mice (33, 40), provided the opportunity to reexamine this question in a host actually devoid of IFN-γ. As shown in Table 1, normal C57BL/6 controls responded to Sb at 100 and 500 mg/kg with leishmanicidal activity (45 and 76% killing of liver amstigotes, respectively). In contrast, GKO mice showed no response to Sb at 100 mg/kg, and while treatment with 500 mg/kg inhibited parasite replication, this treatment failed to induce killing. This latter result identified endogenous IFN-γ as a required regulatory cofactor in the host leishmanicidal response to Sb. (This result also suggested that our original findings with anti-IFN-γ serum-treated mice (16) most likely reflected incomplete cytokine neutralization.) Despite the failure to respond to Sb, however, GKO mice proved fully responsive to AmB (85% killing; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Antileishmanial treatment responses of GKO, iNOS KO, and X-CGD micea

| Mice and treatment (dose [mg/kg]) | Mean liver parasite burden (LDU) ± SEM

|

% Killingb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day +7 | ||

| C57BL/6 | |||

| None | 2,488 ± 220 | 2,386 ± 178 | 4 |

| Sb (100) | 1,374 ± 98 | 45 | |

| Sb (500) | 599 ± 49 | 76 | |

| AmB | 334 ± 73 | 88 | |

| GKO | |||

| None | 3,366 ± 328 | 4,565 ± 433 | 0 |

| Sb (100) | 5,129 ± 385 | 0 | |

| Sb (500) | 3,302 ± 318 | 2 | |

| AmB | 489 ± 123 | 85 | |

| X-CGD | |||

| None | 4,482 ± 259 | 4,150 ± 227 | 7 |

| Sb (100) | 2,217 ± 234 | 51 | |

| Sb (500) | 270 ± 50 | 94 | |

| AmB | 150 ± 51 | 97 | |

| Wild type | |||

| None | 1,560 ± 185 | 1,721 ± 153 | 0 |

| Sb (100) | 411 ± 69 | 74 | |

| Sb (500) | 210 ± 65 | 87 | |

| AmB | 6 ± 4 | 99 | |

| iNOS KO | |||

| None | 2,731 ± 213 | 3,678 ± 390 | 0 |

| Sb (100) | 587 ± 63 | 79 | |

| Sb (500) | 102 ± 16 | 96 | |

| AmB | 78 ± 22 | 97 | |

Two weeks after L. donovani challenge (day 0), parasite burdens were determined and mice received no treatment or a single dose of Sb (100 or 500 mg/kg) or three injections of AmB (5 mg/kg) on alternate days. One week after treatment had started (day +7), all of the mice were sacrificed. Normal C57BL/6 mice served as controls for GKO and X-CGD animals; wild-type littermates served as controls for iNOS KOS. Results are for two or three experiments with 8 to 18 mice per group.

Percent killing = [(day 0 LDU − day +7 LDU)/day 0 LDU] × 100. In all five groups of AmB-treated mice and in all groups of Sb-treated mice, except GKO mice, mean day +7 values are significantly lower than day 0 values (P < 0.05).

Treatment response of mice deficient in IFN-γ-regulated macrophage leishmanicidal mechanisms.

While multiple cytokines and factors prime macrophages for enhanced production of RNI and ROI (14, 20, 23, 24, 27, 30), IFN-γ is thought to play a central role in the upregulation of both microbicidal mechanisms (12, 20, 23, 24, 27, 30, 33, 40, 45). In vitro, IFN-γ-activated mouse peritoneal macrophages kill ingested L. donovani amastigotes by generating either iNOS-derived RNI or respiratory burst-derived ROI (11, 12, 27); studies with iNOS KO and X-CGD mice have also confirmed that these mechanisms operate in vivo and that early on they act together to limit initial visceral parasite replication (20). To determine if the defective response of GKO mice to Sb reflects impaired activity in either of these primary leishmanicidal pathways, X-CGD and iNOS KO mice infected 2 weeks earlier were treated with Sb. Sb (500 mg/kg) remained highly active, however, and killed 94 to 96% of the liver parasites in the absence of either phox or iNOS (Table 1); the response to a suboptimal dose of Sb (100 mg/kg) was similarly preserved. Both iNOS KO and X-CGD animals also responded normally to AmB.

Effects of Sb and AmB on X-CGD mice treated with an iNOS inhibitor.

Since iNOS KO mice produce ROI normally (7) and X-CGD mice show normal RNI secretion (20), it was still possible that one IFN-γ-regulated mechanism is sufficient to support responsiveness to chemotherapy. Therefore, infected X-CGD mice were treated continuously with AG to inhibit iNOS activity (20) and then injected with Sb. In two experiments with these mice doubly deficient in macrophage leishmanicidal mechanisms (20), liver parasite burdens were reduced from 5,220 ± 251 LDU on day 0 (n = 8) to 2,632 ± 331 LDU by treatment with Sb at 100 mg/kg (n = 8 mice; 50% killing) and to 1,241 ± 143 LDU by a single injection of 500 mg/kg (n = 12 mice; 76% killing) on day +7. Corresponding Sb-induced parasite killing in X-CGD mice treated with acidified water alone (n = 8 or 9 mice per group) was 55 and 88%, respectively (data not shown). These values of percent killing were not significantly different (P > 0.05) from those in AG-treated X-CGD mice. Thus, Sb maintained its efficacy in mice apparently deficient in both phox and iNOS.

Experiments using AmB in AG-treated mice, however, proved unsuccessful because of toxicity. Although 100% of AG-treated X-CGD mice given Sb survived, 15 of 18 such animals given AmB died by the time of or within 3 days after the third injection of AmB. In one of the three experiments performed, three of six mice treated with AG plus AmB remained healthy and appeared to show an intact response to AmB: liver parasite burdens declined by 86%, from 4,936 ± 349 LDU on day 0 (n = 6 mice) to 702 ± 57 LDU on day +7 (n = 3 mice). While we are uncertain why most of these animals died, it is worth noting that infected X-CGD mice tolerate weeks of treatment with AG alone (20) and that there were no deaths among X-CGD or iNOS KO mice treated with AmB alone. In a separate follow-up experiment (n = 8 mice per group), infected C57BL/6 controls and both infected and uninfected X-CGD animals were treated in the same fashion with AG and then AmB; all of the mice in each of these three groups died during or shortly after AmB administration. Thus, neither the deficient respiratory burst in X-CGD mice nor the additional presence of L. donovani explained the acute lethal effect of combining AmB with AG.

Response to treatment in the absence of tissue granuloma formation.

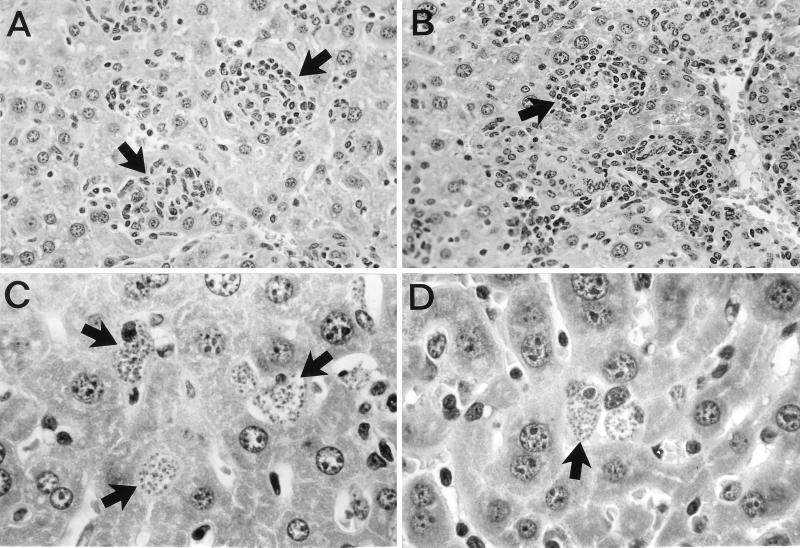

In addition to inducing macrophage leishmanicidal activity in this L. donovani model, endogenous IFN-γ also serves to attract mononuclear cells to parasitized visceral foci and regulates their assembly into granulomas (14, 33, 40). The apparent correlation in both nude and GKO mice between Sb unresponsiveness and the failure to form granulomas (Fig. 1) (14, 35, 40) raised the possibility that Sb's leishmanicidal efficacy in the tissues was granuloma dependent. However, granulomas were also essentially absent in iNOS KO and X-CGD mice at this early stage of infection (Fig. 1) (20) and these mice responded to Sb (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Histologic appearance of livers 2 weeks after infection, when treatment was begun, showing early granuloma formation at parasitized foci (arrows) in normal C57BL/6 mice (A) and wild-type controls for iNOS KO mice (B) but no cellular reaction at infected Kupffer cells (arrows) in GKO (C) or iNOS KO (D) mice. The appearance of livers from X-CGD mice infected 2 weeks before was similar to that shown for iNOS KO mice. Magnifications: A and B, ×200; C and D, ×500.

Outcome after initial response to treatment.

To complete these experiments, we examined the long-term effects of treatment and selected iNOS KO mice for study because, in addition to permitting unrestrained parasite replication early on, these animals also fail to resolve a visceral infection (20). (Neither of the other two types of mutant mice was suitable for testing, since after initial heightened susceptibility, X-CGD mice control L. donovani via a pathway which involves iNOS [20] and GKO mice reduce their parasite burdens after week 8 via a late-acting [tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated, iNOS-associated] mechanism [40].)

Although iNOS KO mice were fully responsive to Sb and AmB during treatment (Table 1), we anticipated that the absence of leishmanicidal RNI in iNOS KO mice would permit surviving parasites to resume replication once the drug effect had dissipated. As indicated in Table 2, visceral infection increased during the 12-week period in untreated iNOS KO mice (albeit at lower overall levels, presumably reflecting the reduced size of the challenge inoculum used in these experiments [see Materials and Methods]). In one of the experiments in Table 2, liver parasite burdens were also determined at week 8, as well as at week 12. These results (1,955 ± 232 LDU [n = 6] at week 8 versus 3,176 ± 361 LDU [n = 7] at week 12) confirmed that infection had increased throughout the 12-week period.

TABLE 2.

Long-term outcome of treated infections of iNOS KO micea

| Treatment of iNOS KO mice | Mean liver parasite burden (LDU) ± SEM

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wk 2 | Wk 3 | Wk 12 | |

| None | 1,578 ± 159 | 2,177 ± 224 | 2,905 ± 307 |

| Sb | 198 ± 14b | 310 ± 74b | |

| AmB | 132 ± 41b | 30 ± 12b | |

Two weeks after challenge with a reduced L. donovani inoculum (see Materials and Methods), iNOS KO mice received no treatment, a single injection of Sb (500 mg/kg), or three alternate-day injections of AmB (5 mg/kg). Liver parasite burdens were determined just before (week 2) and 1 (week 3) and 9 (week 12) weeks after treatment. Results are from two experiments with 10 to 15 mice per group. In untreated wild-type controls challenged in parallel, liver parasite burdens were 888 ± 71 and 51 ± 9 LDU at weeks 2 and 12, respectively (n = 8 mice per time point).

P < 0.05 versus untreated control mice.

As shown in Table 2 and as expected, both Sb and AmB initially induced >90% killing in treated animals. Surprisingly, however, during 9 weeks of posttreatment observation, residual hepatic infection declined further in AmB-treated mice and increased only modestly in Sb-treated animals. These findings suggested that in treatment-modified versus unmanipulated visceral infection (20) (Table 2), an iNOS-independent mechanism had emerged to prevent or limit reactivation of intracellular infection.

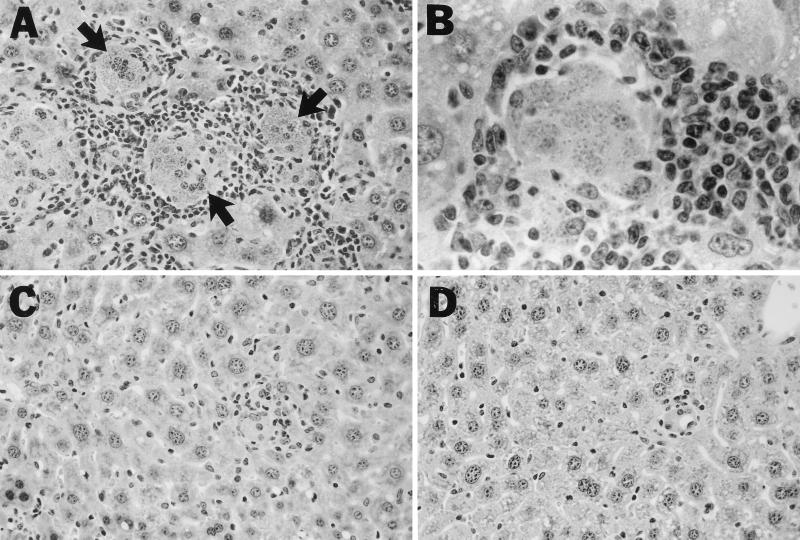

Histologic examination of the livers of untreated mice 12 weeks after infection (Fig. 2) showed macrophages heavily laden with replicating amastigotes surrounded by the intense (albeit ineffective) granulomatous response which eventually develops in iNOS KO mice (20). At the same time point (9 weeks after drug administration), examination of livers of treated mice not only confirmed the presence of few intracellular amastigotes but also demonstrated nearly complete resolution of the inflammatory response.

FIG. 2.

Photomicrographs of livers of untreated and treated iNOS KO mice 12 weeks after L. donovani infection. Untreated mice (A and B) show heavily parasitized foci (arrows) surrounded by an intense but ineffective granulomatous response. In contrast, in mice treated 9 weeks earlier with Sb (C) or AmB (D), few amastigotes are visible and tissue inflammation has nearly entirely resolved. Magnifications: A, C, and D, ×200; B, ×500.

DISCUSSION

Sb exerts intracellular leishmanicidal activity when applied to macrophages parasitized by L. donovani, and this in vitro effect does not require either T cells or exogenous cytokines (15, 21). Nevertheless, despite this direct activity and high-level efficacy in euthymic mice (15), Sb is entirely inactive in T-cell-deficient nude mice (21). Together with the capacity of T cells to reconstitute a response to Sb in nude mice (21), it seems clear that an intervening T-cell-dependent mechanism is required for optimal in vivo responsiveness to this therapeutic agent. The results of the present study identify endogenous IFN-γ as the likely host T-cell-derived cofactor which regulates the in vivo expression of Sb's killing effect.

At the same time, these results also demonstrate that full-dose Sb (500 mg/kg) can still achieve some antileishmanial effect in GKO mice, albeit suboptimal (leishmanistatic). Since lower-dose Sb (100 mg/kg) induced neither parasite killing nor inhibition in GKO mice while inducing ∼50% killing in C57BL/6 controls (Table 1), there appears to be a dose threshold above which Sb can inhibit parasite replication in the absence of endogenous IFN-γ. However, this leishmanistatic effect, too, requires a separate host mechanism, since up to three Sb injections of 500 mg/kg (rather than one injection) fails to induce even leishmanistatic activity in nude mice (21). Other than that it is T cell dependent (21), the nature of this additional mechanism is unknown.

In presence of macrophages, the efficacy of Sb is augmented, and this in vitro-documented effect can be enhanced still further by first activating the macrophages (1, 4, 15, 31, 32). To begin to understand which of IFN-γ's pleiotropic host defense effects permitted the in vivo expression of Sb's killing activity, we focused on the tissue macrophage, which represents not only the target cell for Leishmania but also a principal target for IFN-γ-induced activation (12, 14, 33, 45). Specifically, we examined what role that either or both of the macrophage's primary leishmanicidal mechanisms, regulated by IFN-γ (12, 20, 23, 24, 27, 30, 33, 40, 45), might play. Sb retained its efficacy, however, in tissues devoid of iNOS-derived RNI or phox-derived ROI, indicating that neither mechanism by itself influences Sb's action. Moreover, the leishmanicidal effect of Sb was also not significantly impaired in mice rendered deficient in both killing mechanisms. Thus, it appears that endogenous IFN-γ regulates the response to Sb by an action(s) unrelated to the activity of these two basic macrophage microbicidal mechanisms.

In addition to inducing macrophage activation (12), IFN-γ is also required in this model for mononuclear cell recruitment to parasitized sites and for granuloma formation, the tissue correlate of acquired resistance (33, 40). Therefore, we also considered that the absence of granuloma assembly and a circumscribed inflammatory microenvironment might explain the failure of GKO mice to respond properly to Sb. However, both iNOS KO and X-CGD mice showed an intact response to Sb at a time when these hosts were also granuloma deficient (20).

While the nature of the IFN-γ-dependent mechanism which acts as a regulatory cofactor for Sb remains to be identified, other macrophage-associated effects are possible, including enhancement of an antimicrobial pathway unrelated to RNI or ROI (20, 29) or the increased accumulation of Sb demonstrated in IFN-γ-treated macrophages in vitro (15). A third possible role for endogenous IFN-γ in its interaction with Sb is separate activating effects on T cells (33), including maintenance of a pro-host defense Th1-cell-associated immune response which may counterbalance a simultaneously induced, suppressive Th2-cell mechanism (9, 17, 37). In response to cutaneous L. major infection, for example, GKO mice default to such a Th2-cell-associated mechanism (44) which is capable of inhibiting T-cell function and cytokine release, deactivating macrophages, and promoting progressive infection (9, 14, 22, 44). However, despite a vigorous Th2-cell response, L. major-infected mice respond to Sb during the period in which the drug is administered (22). In our preliminary studies, mice manipulated to react to L. donovani with a disease-exacerbating Th2-cell mechanism (17) also retained responsiveness to Sb during treatment (unpublished observations).

Provoked by the growing clinical problem of Sb treatment failures in India (6, 36, 39) and in human immunodeficiency virus-coinfected patients elsewhere (13), the use of alternative antileishmanial agents, primarily AmB, has increased appreciably (36). AmB differs from Sb in not sharing a requirement for host T cells for its vivo effect (18) and, as documented here, does not require endogenous IFN-γ or the IFN-γ-activated macrophage or its primary microbicidal mechanisms for killing of visceral L. donovani.

The preserved efficacy of AmB in GKO, X-CGD, and iNOS KO mice is relevant to note for other reasons as well. AmB has well-recognized intrinsic immunomodulatory actions (5, 8, 25, 43, 47) which may mediate some of its intracellular antifungal effects (10, 25, 46). Such actions include stimulation of cytokine gene expression and/or release (3, 28, 41, 49) and, in conjunction with IFN-γ, enhancement of iNOS induction and/or ROI production by macrophages (10, 46). Our results obtained with L. donovani suggest that neither of the latter two mechanisms nor the presence of IFN-γ is required for AmB's in vivo intracellular activity, albeit toward a protozoan rather than a pathogenic fungus. The observation that GKO mice infected with Histoplasma capsulatum are also fully responsive to AmB therapy (2, 48), however, lends support to the preceding conclusion.

AmB also induces macrophages to release TNF-α (3, 41), another inflammatory cytokine with well-defined antileishmanial effects (27, 42) which include acting alone (40) or with IFN-γ to increase the production of RNI or ROI (24, 27, 30). Nevertheless, in preliminary experiments, AmB's leishmanicidal activity was not impaired in TNF-α KO mice (unpublished data). Thus, the in vivo action of AmB against L. donovani may well prove to be independent of regulation by host antileishmanial immune mechanisms and therefore entirely direct.

Finally, it is worth commenting on the observation that residual infection in treated iNOS KO mice remained largely suppressed for a prolonged period after brief treatment with AmB or Sb, respectively. This finding was unexpected for three reasons: (i) in the same type of experiment carried out with nude mice, visceral infection predictably relapsed in the absence of host T cells within 8 weeks of near eradication induced by AmB (19); (ii) like T cells, iNOS is also required for resolution of visceral infection in this model (20); and (iii) in a separate model, treatment with an iNOS inhibitor led to prompt reactivation of a previously healed local cutaneous infection caused by L. major (34). Nonetheless, our results appear clear (Table 2 and Fig. 2) and suggest that under the parasite burden-reducing effects of even short-course chemotherapy, a mechanism unrelated to iNOS emerges to maintain control over residual visceral amastigotes. Since infection in AmB-treated nude mice relapses (19), this still-to-be-characterized and perhaps novel iNOS-independent antileishmanial response is likely to be T cell dependent and probably cytokine mediated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Mary Dinauer and Carl Nathan for originally providing the X-CGD and iNOS KO mice.

This research was supported by NIH research grant AI 16963.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adinolfi L, Bonventre P. Enhancement of Glucantime therapy of murine Leishmania donovani infection by a synthetic immunopotentiating compound (CP-46,665-1) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1985;34:270–277. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1985.34.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allendoerfer R, Deepe G S. Intrapulmonary response to Histoplasma capsulatum in gamma interferon knockout mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2564–2569. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2564-2569.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chia J K S, Pollack M. Amphotericin B induces tumor necrosis factor production by murine macrophages. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:113–116. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibrahim M, Hag-Ali M, El-Hassan A, Theander T, Kharazim A. Leishmania resistant to sodium stibogluconate: drug-associated macrophage-dependent killing. Parasitol Res. 1994;80:569–574. doi: 10.1007/BF00933004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin H-S, Medoff G, Kobayashi G S. Effects of amphotericin B on macrophages and their precursor cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977;11:154–160. doi: 10.1128/aac.11.1.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lira R, Sundar S, Makharia A, Kenney R, Gam A, Saraiva E, Sacks D. Evidence that the high incidence of treatment failures in Indian kala-azar is due to the emergence of antimony resistant strains of Leishmania donovani. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:564–567. doi: 10.1086/314896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMicking J D, Nathan C, Hom G, Chartrain N, Fletcher D S, Trumbauer M, Stevens K, Xie Q, Sokol K, Hutchinson N, Chen H, Mudgett J S. Altered responses to bacterial infection and endotoxic shock in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase. Cell. 1995;81:641–650. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medoff G, Brajtburg J, Kobayashi G S, Bolard J. Antifungal agents useful in therapy of systemic fungal infection. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1983;23:303–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.23.040183.001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miralles G D, Stoeckle M Y, McDermott D F, Finkelman F D, Murray H W. Induction of Th1 and Th2 cell-associated cytokines in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1058–1063. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.1058-1063.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mozaffarian N, Berman J W, Casadevall A. Enhancement of nitric oxide synthesis by macrophages represents an additional mechanism of action for amphotericin B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1825–1829. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.8.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray H W. Cell-mediated immune response in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. II. Oxygen-dependent killing of intracellular Leishmania donovani amastigotes. J Immunol. 1982;129:351–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray H W. Effect of continuous administration of interferon-gamma in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:992–994. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray H W. Kala-azar as an AIDS-related opportunistic infection. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 1999;13:459–465. doi: 10.1089/108729199318183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray H W. Granulomatous inflammation: host antimicrobial defense in the tissues in visceral leishmaniasis. In: Gallin J I, Snyderman R, Fearon D T, Haynes B F, Nathan C F, editors. Inflammation: basic principles and clinical correlates. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. pp. 977–994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray H W, Berman J D, Wright S D. Immunochemotherapy for intracellular Leishmania donovani infection: interferon-γ plus pentavalent antimony. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:973–979. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.5.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray H W, Granger A M, Mohanty S K. Response to chemotherapy in experimental visceral leishmaniasis: T cell-dependent but interferon-γ- and interleukin-2-independent. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:622–624. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.3.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray H W, Hariprashad J, Coffman R L. Behavior of visceral Leishmania donovani in an experimentally-induced Th2 cell-associated response model. J Exp Med. 1997;185:867–374. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray H W, Hariprashad J, Fichtl R E. Treatment of experimental visceral leishmaniasis in a T-cell-deficient host: response to amphotericin B and pentamidine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1504–1505. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.7.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray H W, Hariprashad J, Fichtl R. Models of relapse of experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1041–1043. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.4.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray H W, Nathan C F. Macrophage microbicidal mechanisms in vivo: reactive nitrogen vs. oxygen intermediates in the killing of intracellular visceral Leishmania donovani. J Exp Med. 1999;189:741–746. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray H W, Oca M J, Granger A M, Schreiber R D. Successful response to chemotherapy in experimental visceral leishmaniasis: requirement for T cells and effect of lymphokines. J Clin Investig. 1989;83:1254–1259. doi: 10.1172/JCI114009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nabors G S, Farrell J P. Successful chemotherapy in experimental leishmaniasis is influenced by the polarity of the T cell response before treatment. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:979–986. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.4.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nathan C. Inducible nitric oxide synthase: what difference does it make? J Clin Investig. 1997;100:2417–2423. doi: 10.1172/JCI119782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nathan C F, Hibbs J B. Role of nitric oxide synthesis in macrophage antimicrobial activity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1991;3:65–70. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(91)90079-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perfect J R, Granger D L, Durack D T. Effects of antifungal agents and gamma interferon on macrophage cytotoxicity for fungi and tumor cells. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:316–323. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.2.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollock J D, Williams P A, Gifford G, Li L L, Du X, Fisherman J, Orkin S H, Doershuck C M, Dinhauer M C. Mouse model of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, an inherited defect in phagocyte superoxide production. Nat Genet. 1995;9:202–208. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roach T I A, Kiderlen A F, Blackwell J M. Role of inorganic nitrogen oxides and tumor necrosis factor alpha in killing Leishmania donovani amastigotes in gamma interferon-lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages from Lshs and Lshr congenic mouse strains. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3935–3944. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.3935-3944.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogers P D, Jenkins J K, Chapman S W, Ndebele K, Chapman B A, Cleary J D. Amphotericin B activation for human genes encoding for cytokines. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1726–1733. doi: 10.1086/314495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiloh M U, MacMicking J D, Nicholson S, Brause J E, Potter S, Marino M, Fang F, Dinauer M, Nathan C. Phenotype of mice and macrophages deficient in both phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Immunity. 1999;10:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiloh M U, Nathan C F. Antimicrobial mechanisms of macrophages. In: Gordon S, editor. Phagocytosis and pathogens. Greenwich, Conn: JAI Press, Inc.; 1999. pp. 407–439. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sodhi S, Ganguly N, Malla N, Mahajan R. Lymphokine mediated microbicidal activity of peritoneal macrophages from Leishmania donovani infected and drug treated BALB/c mice. Jpn J Exp Med. 1989;59:103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sodhi S, Kaur S, Mahajan R, Ganguly N, Malla N. Effect of sodium stibogluconate and pentamidine on in vitro multiplication of Leishmania donovani in peritoneal macrophages from infected and drug-treated BALB/c mice. Immunol Cell Biol. 1992;70:25–31. doi: 10.1038/icb.1992.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Squires K E, Schreiber R D, McElrath M J, Rubin B Y, Anderson S L, Murray H W. Experimental visceral leishmaniasis: role of endogenous interferon-γ in host defense and tissue granulomatous response. J Immunol. 1989;143:4244–4249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stenger S, Doinhauser N, Thuring H, Rollinghoff M, Bogdan C. Reactivation of latent leishmaniasis by inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1501–1514. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stern J, Oca M, Rubin B Y, Anderson S, Murray H W. Role of L3T4+ and Lyt-2+ cells in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1998;140:3971–3976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sundar S, Agrawal N K, Sinha P R, Horwith G S, Murray H W. Short-course, low-dose amphotericin B lipid complex therapy for visceral leishmaniasis unresponsive to antimony. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:133–137. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-2-199707150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sundar S, Reed S G, Sharma S, Mehrota A, Murray H W. Circulating Th1 cell- and Th2 cell-associated cytokines in Indian patients with visceral leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:522–526. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sundar S, Rosenkaimer F, Lesser M, Murray H W. Immunochemotherapy for a systemic intracellular infection: accelerated response using interferon-γ in visceral leishmaniasis in India. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:992–997. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sundar S, Singh V P, Sharma S, Makharia M K, Murray H W. Response to interferon-γ plus pentavalent antimony in Indian visceral leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1117–1119. doi: 10.1086/516526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor A, Murray H W. Intracellular antimicrobial activity in the absence of interferon-γ: effect of interleukin 12 in experimental visceral leishmaniasis in interferon-γ gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1231–1239. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tokuda Y, Tsuji M, Yamazaki M, Kimura S, Abe S, Yamaguchi H. Augmentation of murine tumor necrosis factor production by amphotericin B in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2228–2230. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.10.2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tumang M, Keogh C, Moldawer L L, Teitelbaum R F, Hariprashad J, Murray H W. The role and effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1994;153:768–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vecchiarelli A, Verducci G, Perito S, Puccetti P, Marconi P, Bistoni F. Involvement of host macrophage in the immunoadjuvant activity of amphotericin B in a mouse fungal infection model. J Antibiot. 1986;39:846–855. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.39.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Z, Reiner S L, Sheng S, Dalton D K, Locksley R M. CD4+ effector cells default to the Th2 pathway in interferon-γ-deficient mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1367–1371. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson M E, Sandor M, Blum A M, Younbag B, Metwali A, Elliot D, Lynch R G, Weinstock J V. Local suppression of IFN-γ in hepatic granulomas correlates with tissue-specific replication of Leishmania chagasi. J Immunol. 1996;156:2231–2239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolf J E, Massof S E. In vivo activation of macrophage oxidative burst activity by cytokines and amphotericin B. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1296–1300. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1296-1300.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamaguchi H, Abe S, Tokuda Y. Immunomodulating activity of antifungal drugs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;685:447–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb35905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou P, Miller G, Seder R S. Factors involved in regulating primary and secondary immunity to infection with Histoplasma capsulatum: TNF-α plays a critical role in maintaining secondary immunity in the absence of IFN-γ. J Immunol. 1998;160:1359–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou P, Sieve M C, Tewari R P, Seder R A. Interleukin-12 modulates the protective immune response in SCID mice infected with Histoplasma capsulatum. Infect Immun. 1997;65:936–942. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.936-942.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]