Abstract

Sex Ratio chromosomes in Drosophila pseudoobscura are selfish X chromosome variants associated with 3 nonoverlapping inversions. In the male germline, Sex Ratio chromosomes distort the segregation of X and Y chromosomes (99:1), thereby skewing progeny sex ratio. In the female germline, segregation of Sex Ratio chromosomes is mendelian (50:50), but nonoverlapping inversions strongly suppress recombination establishing a 26-Mb haplotype (constituting ∼20% of the haploid genome). Rare crossover events located between nonoverlapping inversions can disrupt this haplotype, and recombinants have sometimes been found in natural populations. We recently reported on the first lab-generated Sex Ratio recombinants occurring at a rate of 0.0012 crossovers per female meiosis. An improved experimental design presented here reveals that these recombination events were at least 4 times more frequent than previously estimated. Furthermore, recombination events were strongly clustered, indicating that the majority arose from mitotic exchange in female germline stem cells and not from meiotic crossing-over in primary oocytes. Finally, asymmetric recovery of complementary recombinants was consistent with unequal exchange causing the recombination-induced viability defects. Incorporating these experimental results into population models for Sex Ratio chromosome evolution provided a substantially better fit to natural population frequencies and allowed maintenance of the highly differentiated 26-Mb Sex Ratio haplotype without invoking strong epistatic selection. This study provides the first estimate of spontaneous mitotic exchange for naturally occurring chromosomes in Drosophila female germline stem cells, reveals a much higher Sex Ratio chromosome recombination rate, and develops a mathematical model that accurately predicts the rarity of recombinant Sex Ratio chromosomes in natural populations.

Keywords: Drosophila pseudoobscura, mitotic exchange, Sex Ratio, germline stem cells

Introduction

Selfish sex chromosomes are a special class of segregation distorters found in organisms with chromosomal sex determination (Burt and Trivers 2006). Because nonmendelian transmission of the sex chromosomes skews the ratio of female to male offspring, these chromosomal variants are called Sex Ratio chromosomes. Sex Ratio (XSR) chromosomes are found in 16 species of Drosophila (an XY sex-determination system) where they are typically associated with multiple inversions of the X chromosome (Jaenike 2001; Courret et al. 2019). In Drosophila pseudoobscura, all necessary and sufficient genes for the strong sex ratio distortion phenotype are linked to 3 nonoverlapping inversions of the right arm of the metacentric X chromosome (Fig. 1a) (Dobzhansky and Epling 1944; Wallace 1948).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation for recombination experiments with metacentric X chromosomes of D. pseudoobscura. a) Centromeres are depicted as centrally placed circles and the 3 nonoverlapping inverted regions of the Sex Ratio chromosomes are shown in dark gray on the X chromosome right arm. Physical dimensions of Sex Ratio haplotype and colinear region are listed above the chromosome, below chromosomes are the genetic map position for the visible markers. b) Summary of Fuller et al. (2020) recombination experiment with raw counts provided in parentheses, the asymmetry of this result was very unexpected under a reciprocal-exchange model of meiotic crossing-over .

In natural populations of D. pseudoobscura, the 3 inversions of XSR chromosomes are found in near perfect linkage disequilibrium generating a single, large, highly differentiated 26-Mb Sex Ratio (SR) haplotype (Lewontin 1964; Fuller et al. 2020). Rare recombinant chromosomes that disrupt the 3-inversion 26-Mb SR haplotype have been observed in natural population surveys, but only 5 instances have been found in cumulative sampling of greater than 10,000 X chromosomes (Wallace 1948; Beckenbach 1996; Fuller et al. 2020). Cytogenetic analysis confirms that these rare recombinants did not arise from ectopic exchange between D. pseudoobscura XSR and Y chromosomes; and more generally, brachycerous Dipterans have achiasmate male meiosis (Gethmann 1988; Beckenbach 1996). However, further detailed phenotypic study of recombinant XSR chromosomes has historically been complicated by their rarity and difficult maintenance in the lab (Wallace 1948).

We recently reported rare recombination (on the order of 1 in 1,000 female meioses) occurring in the 6.6-Mb colinear region located between the medial and terminal inversions for heterozygotes of Sex Ratio and Standard X chromosomes (XSR/XST) (Fig. 1b) (Fuller et al. 2020). Segregation assays of recombinant chromosomes revealed that the X-linked genetic architecture of the strong sex ratio distortion phenotype consists of at least 2 loci: a distorter gene in the proximal half of the right arm and a modifier gene in the distal half of the right arm. Using a simple model of gametic phase disequilibrium, we inferred that strong epistatic selection must counteract recombination to maintain approximately 20% of the haploid genome as the single, highly differentiated SR haplotype observed in nature (Fuller et al. 2020). However, this conclusion was based on a model that did not account for the X-linked inheritance of SR haplotype, female-limited recombination or male-specific segregation distortion, and was highly sensitive to the experimentally determined recombination rate.

The recombination experiment reported in Fuller et al. (2020) followed standard testcross protocol by mass crossing 20 female XSR/XST heterozygotes to 20 tester strain males in 6 fl. oz milk bottles (Bridges and Brehme 1944). For logistical reasons, only male progeny were scored for the recombination of X-linked visible markers before being discarded. Twelve of the nearly 10,000 males scored were recombinants; however, all 12 males exhibited the same marker combination (indicating a recombinant carrying only the terminal inversion of XSR chromosomes, denoted XTO) and we observed none of the complementary recombinant XSR chromosome (carrying both the basal and medial inversions but without the terminal inversion, denoted XBM). Under a reciprocal-exchange model of meiotic crossing-over, this was a very rare and unexpected result . Further screening (>10,000 individuals) demonstrated that stable XBM stocks could indeed be established, and polytene chromosome squashes confirmed that the recombination events occurred in the 6.6-Mb colinear region located between the medial and terminal inversions of the SR haplotype [see photomicrograph in Supplementary Fig. 7 of Fuller et al. (2020)].

In the Fuller et al. (2020) experimental design, the short1 mutation marked the absence of the terminal inversion of XSR chromosomes. Only male progeny were scored for recombination due to incomplete penetrance of the wing vein mutation short1 in female homozygotes. Any residual penetrance problems in hemizygous males could have caused incorrect classification of the missing recombinant XBM chromosomes as nonrecombinant wildtype XST chromosomes. Furthermore, if the missing recombinant XBM chromosomes have strong recessive viability defects, then these recombinants would not have been detected in hemizygous male progeny. Finally, in a 10,000 fly experiment, other rare events (e.g. gene conversion or somatic mutation) could have inflated the estimated crossover rate. To address these potential sources of bias, a new recombination experiment was conducted using single-female crosses, scoring both male and female progeny with improved marker penetrance, and retaining recombinant progeny for confirmation testcrosses.

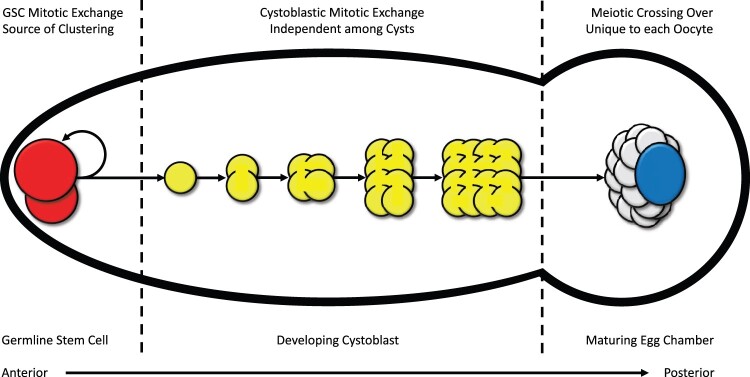

Beyond the potential design artifacts listed above, the rare XSR/XST recombinants may not have been the product of meiotic crossing-over but rather arose from mitotic exchange in the female germline stem cells (GSCs) prior to meiosis. This biological source of variation would confound normal meiotic crossover rate estimation with a recombination process that precedes meiosis. In Drosophila, ovaries are divided into 16–20 ovarioles, each containing 2–3 GSCs occupying a niche in the anterior region of the ovariole (i.e. the germarium, as shown in Fig. 2). Self-renewing GSCs divide asymmetrically to produce a differentiating cystoblast, which undergoes 4 rounds of mitosis with incomplete cytokinesis to form a 16-cell cyst [reviewed in McLaughlin and Bratu (2015)]. In a well-studied determination process, only one of these 16 cells will develop into an oocyte and undergo meiosis while the other 15 cells become nurse cells that do not transmit genetic material to the next generation [reviewed in Huynh and St Johnston (2004)]. Therefore, recombinant progeny resulting from canonical meiotic crossing-over (reciprocal exchange) in each oocyte are causally independent of meiotic crossing-over in other oocytes. In contrast, mitotic exchange occurring in self-renewing stem cells has the potential to create clusters of nonindependent (clonal) recombinant progeny, all originating from a single GSC mitotic event (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Cartoon sequence of germarium and single egg chamber development in anterior region of Drosophila ovariole. Mitotic exchange in GSCs (red on the far left) with their asymmetric division and self-renewal (reflexive arrow) can cause clustering in recombination datasets. Mitotic exchange in developing cystoblast (yellow in the center) cannot cause clustering as only 1 of 16 nuclei will develop into the oocyte (blue on the far right), with the other 15 becoming nurse cells (gray on the far right). Meiotic crossing-over in oocyte (blue) only occurs after development of the 16-cell cyst (yellow) and are causally independent among oocytes. Therefore, clustering of recombination events must originate from mitotic exchange in GSC or earlier in development. Cartoon does not represent a proportional scale but is meant to illustrate the sequential events allowing for interpretation of clustering in recombination data.

Mitotic exchange in the female germline cells is difficult to measure because crossing-over in prophase of meiosis I masks this signal under normal conditions (Ashburner et al. 2004). Nevertheless, 18% of X-Y exchanges from compound chromosome C(1)RM/Y in the female germline were attributed to GSC mitotic exchange (Neuhaus 1936), and rates of female GSC mitotic exchange have been elevated by X-ray irradiation (Bateman and Chandley 1965). In D. pseudoobscura XSR/XST heterozygotes, the nonoverlapping inversions of XSR chromosomes strongly suppress meiotic crossing-over on the entire right arm of the X chromosome; thereby presenting a unique opportunity to measure spontaneous mitotic exchange in female GSCs for naturally occurring X chromosomes under normal conditions. In this specific context, GSC mitotic exchange can be detected statistically by the clustered distribution (i.e. overdispersion) of recombination events.

In this study, an improved experimental design revealed that recombination events were substantially more frequent than previously estimated. Statistical analysis rejected the hypothesis that meiotic crossing-over generated the present recombination dataset. Three distinct types of clustering in recombination events indicated that the nonindependence in this dataset arose from unequal mitotic exchange in the female GSCs. To understand the implications of these experimental results for natural populations, the Edwards (1961) population genetic model of Sex Ratio was extended to incorporate recombination in Appendix A. Modeling unequal mitotic exchange in the Sex Ratio system provided a substantially better fit to natural population frequencies of XSR chromosomes in D. pseudoobscura and, despite the higher recombination rate, the model was able to explain the relative rarity of recombinant XBM and XTO chromosomes in the wild.

Materials and methods

Live-stock construction

The 3 focal Sex Ratio (XSR) chromosomes were identified from natural population collections in Zion National Park, UT, USA, in September 2013 and Kaibab National Forest, AZ, USA, in September 2017. Subsequently, in 2018, the base XSR stocks were created by the reisolation of XSR chromosomes and 20 generations of backcrossing to 3 different highly inbred stocks (F > 0.99), each with a multiply marked standard arrangement X chromosome (XST). The resulting 9 stocks (3 XSR chromosome isolates on each of 3 different backgrounds) were segregating for an unmarked XSR and a marked XST on a homozygous genetic background.

The visible markers of the XST chromosomes spanned the whole right arm of the metacentric X chromosome; and in combination, the mutations yellow1 (y1, 1–74.5), sepia1 (se1, 1–156.5), lanceolate1 (ll1, 1–182.6), snapt1 (sp1, 1–200.3), short1 (sh1, 1–225.9), and tilt1 (tt1, 1–228.2) allowed detection of rare XSR recombinant events (Orr 1995; Fuller et al. 2020). The marker penetrance of sh1 in this study was significantly improved through 2 additional years of inbreeding and marker selection subsequent to the Fuller et al. (2020) experiments. To further improve marker reliability and eliminate any inbreeding effects, the visible mutation combinations se1 sh1, and independently se1 sp1 tt1, were introgressed onto the nearly isogenic (F > 0.99) D. pseudoobscura reference genome background to generate 2 independent tester strains for use in outcrossing procedures in experiments identifying recombination events. A full list of XSR stocks, XST inbred lines, the visible mutations they carry, and the National Drosophila Species Stock Center identification for their genetic background is provided in Table 1 and as a reagent table in Supplementary File 1.

Table 1.

A complete list of lines used.

| Visible markers | Genetic background | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex Ratio (XSR) segregating stocks | ||

| Sex Ratio isolate KBNP2 | y1, se1, sh1 | 14011-0121.06 |

| Sex Ratio isolate KBNP2 | se1, ll1, sp1, tt1 | 14011-0121.08 |

| Sex Ratio isolate KBNP2 | se1, sh1 | Lab Line 2020 |

| Sex Ratio isolate Z8 | y1, se1, sh1 | 14011-0121.06 |

| Sex Ratio isolate Z8 | se1, ll1, sp1, tt1 | 14011-0121.08 |

| Sex Ratio isolate Z8 | se1, sh1 | Lab Line 2020 |

| Sex Ratio isolate Z6 | y1, se1, sh1 | 14011-0121.06 |

| Sex Ratio isolate Z6 | se1, ll1, sp1, tt1 | 14011-0121.08 |

| Sex Ratio isolate Z6 | se1, sh1 | Lab Line 2020 |

| Standard arrangement (XST) inbred lines | ||

| Standard inbred line 1 | y1, se1, sh1 | 14011-0121.06 |

| Standard inbred line 2 | se1, ll1, sp1, tt1 | 14011-0121.08 |

| Standard inbred line 3 | se1, sh1 | Lab Line 2020 |

| Standard arrangement (XST) tester strains | ||

| Standard tester strain 1 | se1, sh1 | 14011-0121.94 |

| Standard tester strain 2 | se1, sp1, tt1 | 14011-0121.94 |

All lines have highly inbred genetic backgrounds with National Drosophila Species Stock Center identifier listed. Inbred lines and tester strains are homozygous for standard arrangement X chromosomes. Sex Ratio stocks are segregating for the inverted arrangement unmarked XSR and standard arrangement multiply marked XST.

Recombination experimental design

To test for recombination in the 6.6-Mb colinear region located between medial and terminal inversions of D. pseudoobscura XSR chromosomes, a single-block, fully coded, randomized design was conducted with the experimenter blinded to genotypic treatment. The factorial design incorporated 3 independent XSR chromosome isolates, each on 3 independent autosomal genetic backgrounds, and 3 independent multiply marked XST chromosomes on those same 3 autosomal genetic backgrounds . Experimental F1 female heterozygotes (XSR/XST) were generated by performing all pairwise crosses, excluding genotypes that would produce inbred genetic backgrounds , for a total of 18 unique outbred experimental genotypes (Supplementary Table 1 in Supplementary File 2). Figure 3 provides the factorial experimental design and a color-coded crossing scheme to produce the outbred F1 experimental genotype, the experimental cross itself, and confirmatory testcross of any recombinant F2 progeny (crossing scheme for all 18 unique F1 experimental genotypes is given in Supplementary File 3).

Fig. 3.

Factorial design matrix and crossing scheme for recombination experiments. The design produced 18 unique F1 XSR/XST genotypes with 9 inbred genotypes excluded. Color-coded crossing scheme shows Cross 1, see Supplementary File 3 for all 18, depicting full D. pseudoobscura karyotype consisting of a metacentric X chromosome, J-shaped Y chromosome, 3 acrocentric autosomes, and 1 pair of dot chromosomes. F2 recombinants are only illustrated as female, but both F2 sexes were scored and backcrossed to confirm recombinants.

A total of 180 F1 experimental virgin females and 900 tester strain males were collected within 12 h of eclosion over a 3-day period. Females and males were aged in separate vials for an additional 3-day period. Using light CO2 anesthesia, 10 females for each genotypic treatment were then individually mated to 5 tester males possessing an independent genetic background (from the D. pseudoobscura reference genome) and the respective X-linked markers (se1 sh1 or alternately se1 sp1 tt1). The 180 single-female crosses (18 genotypic treatments with 10 replicates each) were allowed another 3-day CO2 recovery period, during which all experimental crosses were coded and randomized. Experimental crosses were maintained at 21°C, 65% relative humidity, and 14:10 h light:dark cycle. The single-female crosses were individually tap transferred onto experimental food for a 3-day egglaying period that occurred when all flies were minimally 1 week and no older than 2 weeks posteclosion. Experimental food was standard cornmeal molasses Drosophila media seeded with live yeast. After 3 days, the parental adult was removed under CO2 anesthesia and the food was hydrated as needed with 0.5% v/v propionic acid.

Both male and female F2 progeny were scored daily for visible mutations (se1, sh1 or alternately se1, sp1, tt1) until adult flies stopped emerging, for a total of 17,604 progeny. However, scoring recombination between se1 and sp1 tt1 in female progeny was confounded by the presence of ll+ in the tester strain’s colinear region that altered the penetrance of wing vein mutations sp1 and tt1. Therefore, the 6 genotypic treatments that used the se1, sp1, tt1 marker system could not be reliably scored and were excluded from analysis.

When a putative F2 recombinant was identified, this individual was isolated and mated to multiply marked individuals (se1, sh1) of the opposite sex to establish a temporary stock. Confirmation that the individual carried a true recombinant X chromosome was provided by the transmission and detection of that same marker combination in the subsequent generation. Initial F2 screening identified 102 recombinants among 11,808 progeny scored for visible markers se1 and sh1. Confirmation tests of these 102 recombinants revealed 10% resulted from errors in scoring the wing vein marker sh1. Rates of misclassification for sh1 as wild-type sh+ (3/24, exact binomial 95% confidence interval 0.03–0.36) were statistically indistinguishable from the rate of misclassifying sh+ as a mutant sh1 (7/78, exact binomial 95% confidence interval 0.03–0.18).

Statistical analysis of recombination

An ANOVA with type II sum of squares was conducted testing XSR chromosome isolate effect and genetic background effect on the observed recombination rate. First, any putative recombinant that was not confirmed in subsequent generations was recoded in the dataset. Second, the recombination rate was calculated as the number of confirmed recombinants divided by the total number of progeny scored for each single-female cross. Third, this proportion was arcsine-transformed () to fit ANOVA’s error term normality assumption (Sokal and Rohlf 1995). The linear model analyzed was ; where is the effect of the ith XSR chromosome isolate, is the effect of the jth genetic background, and represents the error term. Because no statistically significant effects related to XSR chromosome isolate or genetic background were detected, all subsequent analyses did not subdivide the dataset based on these factors.

To investigate whether the observed data were consistent with meiotic crossing-over, the count of recombinants per single-female cross was compared to the Poisson distribution. Assuming meiotic recombination events were rare and occur independently, then the probability of observing a given number of recombinants for single-female cross with offspring is , where is the experiment-wide rate of recombination. The probability distributions for each single-female cross were combined to generate an experiment-wide distribution accounting for differences in offspring number among crosses. To evaluate the full observed dataset, a goodness-of-fit test with 4 degrees of freedom was conducted with expected values given by the experiment-wide distribution. The probability of observing a single-female cross with more than 4 recombinants in this design is always less than 0.01. Therefore, the few crosses that produced 5, 6, and 9 recombinants were pooled into a single class consisting of recombinants (this is a statistically conservative procedure for this dataset).

To further investigate whether the observed data were consistent with reciprocal-exchange model of meiotic crossing-over, the proportion of recombinants per single-female cross carrying only the terminal inversion (XTO), and not the basal or medial inversions (XBM), was compared to the binomial distribution. Assuming recombination events were independent with an equal probability of transmitting either complementary recombinant X chromosome to progeny , then the probability of observing a given number of recombinants for single-female cross carrying only the terminal inversion is binomially distributed , where is the number of recombinants from cross with total progeny scored. The probability distribution for each single-female cross producing 2 or more recombinants was binned to generate an experiment-wide distribution that controlled for differences in recombinant numbers among crosses. The observed data were then compared to the binned expected distribution with a goodness-of-fit test with 4 degrees of freedom.

Finally, to investigate whether sex of the progeny scored for recombination had an effect on the chances of observing complementary recombinant X chromosomes, a contingency table was analyzed. Under a reciprocal-exchange model of meiotic crossing-over with no effect of progeny sex on detection probability, all 4 classes (i.e. females with XBM, males with XBM, females with XTO, and males with XTO) were expected to occur with equal frequency. The observed data were compared to this expectation (discrete uniform distribution) using a goodness-of-fit test with 3 degrees of freedom.

Population genetic modeling

To understand the natural population consequences of the experimentally detected deviations from a reciprocal-exchange meiotic crossing-over, I incorporated recombination into the classical model of Sex Ratio evolution (see Appendix A for detailed derivation). Briefly, Edwards (1961) developed a sex-specific, genotypic model for Sex Ratio because X-linked meiotic drivers cause sustained difference in allele frequencies between the sexes. The extended model in this study used a mating table as a transition matrix to convert the 40 possible mating types (4 male genotypes 10 female genotypes) to the next generation’s 14 genotypic frequencies (4 male genotypes and 10 female genotypes). The full 40 14 mating table is provided as Supplementary File 4 and is rewritten in Appendix A as a system of recursion equations with 14 variables representing the frequency of each genotype. This is a discrete generation model, where the genotypic frequencies in the next generation are a function of the frequencies in the previous generation and parameters vi,j for relative viability, fi,j for relative fertility, ki for transmission in the male germline, and ci,j for the recombination rate of double heterozygotes in the female germline [Equation (A1) assuming recombination is “meiotic crossing-over” and Equation (A2) assuming recombination is “mitotic unequal exchange”].

I parameterized the extended model of Edwards (1961) with experimental data on viability, fertility, distortion, and recombination (Curtsinger and Feldman 1980; Fuller et al. 2020; this study). Making the additional assumption that fitness effects in recombinants were both recessive and proportional to the fraction of 26-Mb SR haplotype retained after recombination, experiment-based estimates for all 34 parameters in this extended population genetic model were provided (Table A1). Under these conditions, the equilibrium frequencies of all 14 genotypic variables were solved for by iterating the system of equations with a range of different initial frequency combinations spanning 0.01–0.99. Finally, the modeled equilibrium frequencies assuming recombination occurred as “meiotic crossing-over” or alternately under conditions of “mitotic unequal exchange” were compared to the gold standard of Beckenbach’s (1996) direct cytological observation of SR inversion complement for 694 X chromosomes sampled from Tucson and Bear Creek, AZ, USA.

Results

After adjusting for false positives, the observed experiment-wide recombination rate was 0.00779 (92 recombinant chromosomes observed in 11,808 progeny). Substantial heterogeneity among the single-female crosses was observed in recombination rates (for raw counts see Supplementary File 5). The dataset was generated under common garden conditions as a single-block, fully randomized, factorial experimental design with the investigator blinded to treatment, such that the observed heterogeneity was not likely an artifact of design. To investigate the biological sources of recombination rate heterogeneity, and to test the null hypothesis that a reciprocal-exchange model of meiotic crossing-over produced this pattern of heterogeneity, the distribution of observed data was subjected to further statistical analysis.

No genetic variation for recombination rate

To investigate whether the XSR chromosome isolate or genetic background affected recombination, a type II ANOVA was conducted on arcsine-transformed rate data. No statistically significant effects were detected for the 3 XSR chromosome isolates or the 3 genetic backgrounds (Table 2). In addition, no statistically significant effects were detected in sex-stratified analysis of the rate data (Supplementary Table 2). Therefore, all subsequent analyses did not subdivide dataset based on XSR chromosome isolate or genetic background.

Table 2.

Recombination rate ANOVA table.

| Source of variation | df | SS | MS | Fs | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XSR chromosome isolate | 2 | 19.95 | 9.98 | 0.57 | 0.57 |

| Genetic background | 2 | 29.16 | 14.58 | 0.84 | 0.44 |

| Residuals | 115 | 2,005.82 | 17.44 | ||

| Total | 119 | 2,054.93 |

No genetic variation for recombination rate was detected when analyzing the effect of 3 XSR chromosome isolates and 3 heterozygous genetic backgrounds with type II ANOVA.

Recombination events were clustered among single-female crosses

To investigate whether the data were consistent with meiotic crossing-over (i.e. independence of recombination events among single-female crosses), the observed count of recombinants per single-female cross was compared to the Poisson distribution using the experiment-wide recombinant frequency as the rate parameter λ (Fig. 4a). A goodness-of-fit test with 4 degrees of freedom revealed that the observed recombination events were not independent (Table 3). Substantially more single-female crosses produced either no recombinants or multiple recombinants than were expected assuming independence of recombination events. The coefficient of dispersion differed with statistical significance from the Poisson distribution’s expected value of 1 , indicating that the data were strongly clustered. The same pattern of overdispersion (clustering) was present in sex-stratified analysis of observed data (Supplementary Table 3). Strong clustering of observed data rejects the null hypothesis that reciprocal exchange in meiosis produced this dataset and suggests that multiple recombinant X chromosomes recovered from the same experimental F1 single-female cross were clonal.

Fig. 4.

Observed versus expected distribution of recombination events. a) Observed recombination events (red) were clustered among single-female crosses when compared with Poisson expectations (blue) based on experiment-wide recombination rate (see Table 3). b) Proportion of recombinants carrying XTO were clustered within single-female crosses when compared with expected proportions from the binomial distribution. Multiple recombinants from single-female crosses (red) were more likely to all be XTO than expected by chance (blue) (see Table 4). c) Recovery rates of complementary recombinants were neither equivalent between nor independent of F2 progeny sex. The observed data (red) differed from uniform discrete expectations (blue) with statistical significance (see Table 5). A deficit of both complementary recombinants (XTO and XBM) was detected in the hemizygous (male) state and was particularly severe for XBM.

Table 3.

Recombination events were not independent among F1 single-female crosses.

| Category | Expected | Observed | (Obs − Exp)2/Exp |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 recombinants | 56.44 | 70 | 3.26 |

| 1 recombinant | 41.87 | 33 | 1.88 |

| 2 recombinants | 16.24 | 6 | 6.46 |

| 3 recombinants | 4.36 | 7 | 1.60 |

| ≥4 recombinants | 1.09 | 4 | 7.83 |

|

| |||

| χ2 = 21.03 | |||

The number of recombination events per single-female cross, if events were independent, should be Poisson distributed. A goodness-of-fit test revealed the observed recombination events per single-female cross differed with statistically significance from Poisson expectations using an experiment-wide recombination rate . Clustering was even more extreme than the test indicates due to conservative procedure of binning crosses producing 4 or more recombinants (see Fig. 4a).

Multiple recombination events were clustered within single-female crosses

To investigate whether the observed data were consistent with meiotic crossing-over (i.e. independence of recombination events within a single-female cross), the proportion of recombinants carrying XTO within the progeny from a single-female cross was compared to the binomial distribution (Fig. 4b). A goodness-of-fit test revealed multiple recombinants from a single-female cross differed with statistical significance from binned expectations assuming independence (Table 4). The same pattern of clustering was present in sex-stratified analysis of data, indicating that hemizygous fitness effects were not solely responsible for this deviation from independence (Supplementary Table 4). Multiple recombinants from a given single-female cross were more likely to carry the same inversion complement than expected by chance, again rejecting the null hypothesis of meiotic reciprocal exchange and further suggesting that multiple recombinant X chromosomes recovered in from the same experimental F1 single-female cross were clonal.

Table 4.

Multiple recombination events were not independent within F1 single-female crosses.

| Category | Expected | Observed | (Obs − Exp)2/Exp |

|---|---|---|---|

| q = 0.0 | 2.44 | 1 | 0.85 |

| 0.0 < q ≤ 0.3 | 3.69 | 1 | 1.96 |

| 0.3 < q ≤ 0.6 | 4.74 | 0 | 4.74 |

| 0.6 < q ≤ 0.9 | 3.69 | 1 | 1.96 |

| q = 1.0 | 2.44 | 14 | 54.79 |

|

| |||

| χ2 = 64.30 | |||

Proportion of recombinants carrying one inversion complement (XTO) in single-female crosses producing multiple recombinants via meiotic crossover should be binomially distributed. A goodness-of-fit test revealed statistically significant deviation from these expectations . Multiple recombinants from single-female crosses (predominantly XTO) were much more likely to carry the same inversion complement than expected by chance (see Fig. 4b).

Recovery rates of recombinants were neither equivalent nor independent of sex

To investigate whether the sex of progeny scored for recombination had an effect on the probability of observing a recombinant (i.e. recombination events in F1 female germline were independent of F2 progeny sex), the observed data were compared to a discrete uniform distribution (Fig. 4c). The observed data differed from expectations with statistical significance (Table 5). These results demonstrated that recovery of recombinant X chromosomes was strongly dependent on the F2 sex in which they were detected, with the most noticeable deficit occurring in the male XBM class.

Table 5.

Recovery rates of complementary recombinants were not equivalent among F2 progeny sex.

| Category | Expected | Observed | (Obs − Exp)2/Exp |

|---|---|---|---|

| XBM, female | 23 | 20 | 0.39 |

| XBM, male | 23 | 1 | 21.04 |

| XTO, female | 23 | 51 | 34.09 |

| XTO, male | 23 | 20 | 0.39 |

|

| |||

| χ2 = 55.91 | |||

The observed recombinants classified by sex and inversion complement differed from uniform discrete expectations with statistical significance (see Fig. 4c). Observation of complementary recombinants was strongly dependent on the F2 sex in which they were detected, with the most noticeable deficit occurring in the male XBM class.

The observed recovery rates for XBM recombinants in both males and females were much lower when compared to the complementary recombinant XTO. tests of independence failed even when different rates of production were estimated from the data for complementary recombinant classes (Supplementary Table 5). There was also a deficit of both complementary recombinants (XTO and XBM) detected in the hemizygous (male) state compared to the protected heterozygous (female) state. Again, tests of independence failed after different rates for both sexes and complementary classes were estimated from the data (Supplementary Table 5). Even after these corrections, the most noticeable deficit was still due to the hemizygous (male) XBM class, a genotype with notably reduced viability in the laboratory (Wallace 1948; Fuller et al. 2020). The process of recombination itself causing asymmetric recessive viability defects is consistent with a model of mitotic exchange generating a chromosomal deletion for XBM, and a complementary duplication for XTO, via unequal crossing-over in the female GSC.

Experimental results predict recombinant rarity in the wild

The natural population consequences of these experimental results are not intuitive; therefore, I explored their effect with the classical model of Sex Ratio evolution extended to include recombination (Edwards 1961). This is a sex-specific, genotypic model for Sex Ratio with viability, fertility, and transmission parameters drawn from published experimental data (Curtsinger and Feldman 1980; Fuller et al. 2020). Evolution of all 14 genotypes formed from XST, XSR, XBM, and XTO chromosomes was investigated by iterating a system of equations generated from the full 40 14 mating table provided in Supplementary File 4 (see Appendix A for detailed derivation and system of equations).

First, “meiotic crossing-over” conditions were investigated by assuming XSR/XST recombination was due to meiotic crossing-over with an experiment-wide recombination rate while making the additional assumption that fitness effects in recombinants are both recessive and proportional to the fraction of 26-Mb SR haplotype retained after recombination (Table A1). The equilibrium frequencies of all 14 genotypes, with a range of initial frequency combinations between 0.01 and 0.99, all converged on values reported in Table 6 (column “meiotic crossing-over”).

Table 6.

Numerical solutions for equilibrium genotypic frequencies in D. pseudoobscura Sex Ratio system.

| Genotype | Frequency notation | Meiotic crossing-over | Unequal mitotic exchange |

|---|---|---|---|

| XSTY | x1 | 3.5 × 10−1 | 3.5 × 10−1 |

| XSRY | x2 | 3.6 × 10−2 | 4.6 × 10−2 |

| XBMY | x3 | 1.6 × 10−2 | 4.1 × 10−5 |

| XTOY | x4 | 2.7 × 10−3 | 1.2 × 10−3 |

| XSTXST | x1,1 | 4.1 × 10−1 | 4.3 × 10−1 |

| XSTXSR | x1,2 | 1.2 × 10−1 | 1.6 × 10−1 |

| XSTXBM | x1,3 | 4.8 × 10−2 | 9.5 × 10−4 |

| XSTXTO | x1,4 | 6.4 × 10−3 | 5.0 × 10−3 |

| XSRXSR | x2,2 | 5.8 × 10−3 | 9.8 × 10−3 |

| XSRXBM | x2,3 | 5.3 × 10−3 | 1.6 × 10−4 |

| XSRXTO | x2,4 | 8.4 × 10−4 | 8.8 × 10−4 |

| XBMXBM | x3,3 | 1.1 × 10−3 | 1.1 × 10−7 |

| XBMXTO | x3,4 | 3.8 × 10−4 | 5.7 × 10−6 |

| XTOXTO | x4,4 | 2.2 × 10−5 | 1.0 × 10−5 |

The equilibrium frequencies are listed for all genotypes (4 male hemizygous states, 4 female homozygous states, and 6 female heterozygous states) in the recombination extensions of Edwards (1961) model of Sex Ratio evolution. Full system of 14 equations is derived in Appendix A by assuming recombination was either reciprocal exchange caused by meiotic crossing-over in the primary oocyte or alternately caused by unequal mitotic exchange in female GSCs. Under alternate assumptions, the largest differences all involve the genotypes with XBM and are highlighted in bold.

Summing across genotypes, the modeled equilibrium frequencies of recombinant X chromosomes under “meiotic crossing-over” conditions were 0.045 (XBM) and 0.0065 (XTO), with SR inversion linkage disequilibrium (Fig. 5a and Table 7). These results can be evaluated by comparison to the gold standard of Beckenbach’s (1996) direct cytological observation of SR inversion complement for 694 X chromosomes sampled from Tucson and Bear Creek, AZ, USA. The SR population genetic model assuming “meiotic crossing-over” conditions when compared to direct natural population observations reveals: (1) incorrect prediction of the rank order of recombinant X chromosomes, (2) inaccurate estimates of the natural population XSR, XBM, and XTO frequencies, and (3) a large discrepancy in linkage disequilibrium of SR inversions (Table 7).

Fig. 5.

Modeled evolutionary trajectories for X chromosome variants in D. pseudoobscura. Change in population frequency of XST (black), XSR (yellow), XBM (red), and XTO (blue) chromosomes with initial frequencies ranging from 0.01 to 0.99. For comparison, Beckenbach’s (1996) observations from AZ, USA are given as color-coded points on the far right with exact binomial 95% confidence intervals. a) Extension of Edwards (1961) population genetic model assuming recombination is reciprocal-exchange “meiotic crossing-over.” b) The same model incorporating experimentally determined asymmetries in recombination due to “unequal mitotic exchange.” The Edwards (1961) model incorporating unequal mitotic exchange is a much better fit to the frequencies observed in the wild (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Observed and modeled D. pseudoobscura X chromosome variant frequencies and linkage disequilibrium of SR haplotype inversions.

|

Direct cytological observations |

Decay model of inversion LD |

SR model assuming meiotic crossover |

SR model with unequal mitotic exchange |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XST | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.84 | 0.85 |

| XSR | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| XBM | 0.001 | 0.16 | 0.045 | 0.001 |

| XTO | 0.003 | 0.16 | 0.007 | 0.004 |

| r2 | 0.97 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 0.97 |

Direct cytological observations of Beckenbach (1996) were compared to the modeled frequencies and linkage disequilibrium from the decay model of Fuller et al. (2020) as well as the recombination extensions of Edwards (1961) derived in Appendix A. The best fit to natural population frequencies of XST and XSR chromosomes, their recombinants XBM and XTO, and linkage disequilibrium (r2) of SR haplotype inversions was the model for Sex Ratio evolution incorporating unequal mitotic exchange through experimentally determined asymmetries in recombination.

Second, “mitotic unequal exchange” conditions were investigated where XSR/XST recombination was modeled by calculating independent complementary recombinant class-specific rates ( and ) from experimental data in the protected heterozygous state (i.e. from F2 female progeny only in Fig. 4c) . Similarly, hemizygous relative viabilities for the complementary recombinants were calculated as the experimentally observed proportional deficit of recombinants observed in F2 male versus F2 female progeny in Fig. 4c. All other parameters remained identical to the “meiotic crossing-over” conditions. Solving the new system of equations [Equation (A2)], with new parameter values based experimentally observed asymmetries in recombination, revealed that the largest changes in equilibrium frequencies all involve genotypes containing XBM (bold values in Table 6).

Incorporating the experimentally observed XSR/XST recombination asymmetries in this manner, and summing across genotypes, the modified model described above produced equilibrium frequencies of 0.00072 (XBM) and 0.0044 (XTO), both of which are within the 95% confidence intervals of Beckenbach’s (1996) sampled frequencies (Fig. 5b). Further benchmarking against Beckenbach (1996) demonstrated that the SR population genetic model under “unequal mitotic exchange” conditions could: (1) correctly predict rank order of recombinant X chromosome frequencies, (2) improve fit to natural population XSR, XBM, and XTO frequencies, and (3) closely match SR inversion linkage disequilibrium in the wild (Table 7). The close match of D. pseudoobscura natural population observations and modeled equilibrium frequencies of XSR, XBM, and XTO chromosomes under the “unequal mitotic exchange” conditions both explains the rarity of SR recombinants in the wild and nullifies our previous conclusion that epistatic selection must act to maintain the 26-Mb SR haplotype (Fuller et al. 2020).

Discussion

The present results demonstrate that recombination events located between nonoverlapping inversions of Sex Ratio chromosome heterozygotes in D. pseudoobscura were not as rare as previously estimated. Importantly, the recombination events exhibited strong clustering both among and within single-female crosses. The hypothesis that canonical meiotic crossing-over (reciprocal exchange) generated this recombination dataset was unambiguously rejected (Fig. 4). At least 17 of 50 single-female crosses that produced recombinants can be statistically attributed to mitotic exchange in female GSCs or an earlier stage in development (Fig. 2). As a result, at least 64% of the total recombinant progeny observed in this experiment (59/92) originated from female germline mitotic exchange. The remaining 36% of recombinants occurred in single-female crosses that produced only one recombinant in the 3-day egglaying period and therefore provided insufficient information to determine whether their origin was due to mitotic exchange or meiotic crossing-over. Thus, while 92 recombinant chromosomes were observed in 11,808 progeny scored, these 92 recombinants may be the product of as few as 50 unique recombination events.

The observed experiment-wide recombination rate of 92 recombinant chromosomes per 11,808 progeny scored (0.00779) was within the expected range if a single XSR/XST heterozygous GSC was converted via mitotic exchange per single-female cross (expected range 0.00417–0.00781, calculated assuming 2–3 GSCs per ovariole, 16–20 ovarioles per ovary, 2 ovaries per female). In principle, mitotic exchange may occur after asymmetric division of GSCs in the cystoblast; but because each cyst only yields one oocyte, any mitotic exchanges subsequent to differentiation from GSCs cannot be the source of clustering (Fig. 2). Conversely, the most extreme single-female recombination rates observed in this experiment (e.g. 6/47 and 9/122) may be caused by mitotic exchange in primordial germ cells prior to their development into GSCs, therefore leading to a subpopulation of clonal GSCs with the converted genotype. Based on the close match with the expected range, the large majority of the observed recombination events appear to have occurred as mitotic exchange in female GSCs rather than in an earlier stage.

The statistical approach of this study cannot provide direct evidence of unequal mitotic exchange, but asymmetric patterns in the dataset (i.e. specific deficit of XBM recombinants or deficit of hemizygous recombinants more generally) were consistent with unequal exchange. The most parsimonious explanation for the different recovery rates of complementary recombinants, and the observed recombination-induced recessive viability defects, is unequal exchange generating a chromosomal deletion for XBM and a complementary duplication for XTO. However, it is possible that more complex chromosomal aberrations stemming from the mitotic exchange may have caused the disproportionate deficit of hemizygous XBM recombinants observed in Fig. 4c. In future studies, identification of recombination breakpoints with long-read sequencing could provide direct evidence for this scenario’s predictions that: (1) clustered recombinants had clonal origins, (2) repetitive genetic elements mediated ectopic exchange, and (3) deleted and/or duplicated regions at breakpoints caused the observed fitness defects. Sequencing-based insights into mechanism may also help establish if the recombination rate represents a normal baseline of mitotic exchange in the genome or is due to unique structural features of the 6.6-Mb colinear region of XSR chromosomes.

Mitotic exchange in Drosophila female GSC is not entirely unknown but remains understudied because, under normal circumstances, its signal is swamped by the noise of meiotic crossing-over (Ashburner et al. 2004). Indeed, the previous evidence of GSC mitotic exchange comes from extreme conditions such as X-ray irradiation or compound X and Y chromosomes in the female germline (Neuhaus 1936; Bateman and Chandley 1965). However, if low levels of female GSC mitotic exchange are universal, then it is interesting to speculate that they are (at least in part) responsible for the unpatterned residual recombination observed in mutants of Drosophilamelanogaster’s minichromosome maintenance complex (mei-MCM) that regulates meiotic crossover formation (Liu et al. 2000; Kohl et al. 2012; Hartmann et al. 2019).

Extending this same logic, mitotic exchange in the female germline provides a convenient explanation for the counter-intuitive results implicating Bloom syndrome helicase (Blm) as an anticrossover factor in mitosis but pro-crossover factor in meiosis (Hatkevich and Sekelsky 2017). Blm mutants elevate mitotic exchange due to failed synthesis-dependent strand annealing and double-Holliday junction dissolution when repairing double-strand breaks that occur outside of meiosis (Adams et al. 2003; McVey et al. 2007). Blm mutants also exhibit unpatterned, mei-9-independent, large residual “meiotic” recombination (∼70% of wild-type rates compared to ∼10% residual recombination of mei-MCM mutants) (Hatkevich et al. 2017). Rather than postulating 2 different functions of Blm, it is possible that the high residual recombination rate assumed to be “meiotic” was instead just a compounded product of elevated exchange in the mitotic divisions of the female germline. Tests of this and other mitotic exchange hypotheses can be conducted as sensitized assay with meiotic mutants (Zwick et al. 1999), does not require sequence-based analysis, and can be readily disproven with statistical analysis of clustering in single-female crosses.

Modeling recombinant rarity in natural populations

Returning to the specific case of Sex Ratio system in D. pseudoobscura, the higher recombination rate observed in this study intuitively suggests that recombinant Sex Ratio chromosomes should be more frequent in the wild (greater than 10% of X chromosome variants at equilibrium). However, both XTO and XBM are still quite rare (less than 1%) in natural population samples with only 5 instances known from greater than 10,000 X chromosomes tested (Sturtevant and Dobzhansky 1936; Wallace 1948; Beckenbach 1996; Fuller et al. 2020). To investigate whether the properties of unequal mitotic exchange could explain the low frequencies of XTO and XBM in the wild, it was necessary to introduce recombination into the Edwards (1961) population genetic model of Sex Ratio in D. pseudoobscura (see Appendix A for model extension).

The extended model of Sex Ratio evolution in D. pseudoobscura was explored under 2 recombination scenarios “meiotic crossing-over” and “unequal mitotic exchange.” Comparison of Fig. 5a and b and examination of Table 7 reveal that the “unequal mitotic exchange” model was a better predictor of both natural population frequencies and the observed pattern of SR inversion linkage disequilibrium. Importantly, the alternative scenario of “unequal mitotic exchange” simply replaces the standard assumption that all recombination events are (1) independent, (2) reciprocal exchange, and (3) do not directly cause deleterious fitness effects, with parameter values reflecting the experimentally observed recombination asymmetries. Thus, the “unequal mitotic exchange” conditions do not rely on any specific theoretical model of recombination, and the use of this nomenclature is based the parsimonious explanation of the data and used as a convenient short-hand description to differentiate these conditions from the standard reciprocal-exchange model of “meiotic crossing-over.”

Whereas the statistical analysis of the experimental data strongly rejects the null hypothesis that “meiotic crossing-over” generated the recombination dataset (Fig. 4), it is the modeling of natural population frequencies that reveals adopting the alternative hypothesis of “unequal mitotic exchange” is important for understanding the evolutionary dynamics of the D. pseudoobscura SR system (Fig. 5). Of the 3 main experimental results, (1) higher recombination rates, (2) clustered recombination events, and (3) asymmetric recovery of complementary recombinant classes, it appears that the last of these has the greatest importance in explaining the equilibrium frequencies of X chromosome variants in natural populations. This analysis suggests that incorporating the experimentally determined deficit of hemizygous recombinants into the population model in the form of recombination-induce viability defects is sufficient to explain XBM and XTO rarity in the wild, thereby eliminating the need to invoke additional epistatic selection to maintain the highly differentiated 26-Mb SR haplotype.

Implications for meiotic drive and mitotic drive

The causal mechanism for D. pseudoobscura Sex Ratio segregation distortion, and the underlying genetic basis, remains unknown. The results of this study have major implications for the frequency of recombinant Sex Ratio chromosomes in natural populations, and therefore, the population genetic inference on historical selection regimes maintaining the highly differentiated 26-Mb SR haplotype. However, the experimental results presented here do not alter our current understanding of the genetic architecture of the Sex Ratio segregation distortion phenotype. Thus, the model in Fuller et al. (2020) of: (1) a causal, but weak, distortion locus residing in the proximal half of the right arm of the XSR chromosome and (2) a modifier locus in the distal half of the same chromosome arm that strengthens distortion to nearly 100%, but is incapable of distorting on its own, is not altered by this study.

In contrast, the discovery that female germline mitotic exchange is the major source of Sex Ratio chromosome recombination in D. pseudoobscura does potentially have implications for mitotic drive. Mitotic drive, as a population genetic mechanism, describes the outcome of competition among lineages in GSCs where asymmetric division and self-renewal can lead to differential transmission to the next generation. For mitotic drive to impact natural population allele frequencies requires: (1) genetic differentiation among lineages in the germline and (2) that genetic differentiation must confer a systematic proliferative advantage (via increased division, increased longevity, or some other mechanism). Interestingly, mitotic drive has been demonstrated in D. melanogaster where induced chinmo mutant lineages selectively evict nonmutant lineages by remodeling the extra cellular matrix in the male GSC niche (Tseng et al. 2022). While mitotic exchange in XSR/XST heterozygotes of D. pseudoobscura did generate new genetic lineages in GSCs (fulfilling the first condition) and there was greater overall representation of XTO than XBM in the progeny (the pattern of mitotic drive), there is no evidence to suggest that this result was due to a proliferative advantage of XTO in the GSC niche of F1 experimental females. Instead, I have favored the simpler explanation that unequal exchange causes reduced F2 viabilities that are reflected in the asymmetric patterns in the dataset (i.e. specific deficit of XBM recombinants and deficit of hemizygous recombinants more generally).

Conclusion

The recombination rate in the 6.6-Mb colinear region of D. pseudoobscura XSR/XST heterozygotes was revised upward to 0.00779 (92 recombinant chromosomes in 11,808 progeny) using an improved experimental design. Statistical analysis of rate heterogeneity revealed that the majority of these recombination events did not occur as independent meiotic crossover events in primary oocytes, but rather they were clustered in a manner consistent with unequal mitotic exchange in the female GSCs. Incorporating the experimentally observed asymmetries in recombination into a sex-specific, genotypic models of Sex Ratio evolution provided a substantially better fit to natural population frequencies and thereby eliminates the need to invoke any additional selection to maintain the 26-Mb SR haplotype in D. pseudoobscura.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Nitin Phadnis, Sarah Gross, and Shelley Reich of the University of Utah for helpful suggestions in preparation of the article.

Funding

Data analysis and manuscript preparation was performed at Stowers Institute for Medical Research where the author was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences NRSA fellowship NIH F32 GM134707 awarded to SK. The experiment was performed at University of Utah where the author was supported with funds provided from National Institute of General Medical Sciences NIH 1R01 GM115914 awarded to Nitin Phadnis. Research funders had no role in design, execution, analysis, interpretation, and reporting of this study.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Appendix A: Population genetic modeling

To determine the implications of the experimental results for natural populations, the Edwards (1961) model of Sex Ratio (SR) in Drosophila pseudoobscura was extended to include recombination. Following the original model, female genotypes for standard arrangement X chromosomes and the multiply inverted SR chromosome variants are XST/XST, XST/XSR, and XSR/XSR with frequencies denoted by , , and , respectively. The male genotypes are XST/Y and XSR/Y with respective frequencies and , such that . Let the relative viabilities of these 5 genotypes be , , , , , with relative fertilities , , , , where the subscript denotes the corresponding genotype. To model X-linked segregation distortion, male genotypes produce a proportion of female offspring , with representing mendelian transmission of XST chromosomes and representing complete distortion of XSR chromosomes.

To incorporate recombination into the Edwards (1961) model, let exchange in the 6.6-Mb colinear region located between medial and terminal inversions of SR chromosomes occur with frequency in the double heterozygotes XSR/XST. Exchange in the colinear region generates 2 new recombinant X chromosomes: XBM, with basal and medial inversions and approximately two-thirds of the 26-Mb Sex Ratio haplotype, and XTO, which carries the terminal inversion only and about one-third of the 26-Mb Sex Ratio haplotype. Male genotypic frequency of XBM/Y and XTO/Y is denoted and , respectively, with corresponding relative viabilities and relative fertilities of , and , . Following this notation, the female genotypes XST/XBM, XST/XTO, XSR/XBM, XSR/XTO, XBM/XBM, XBM/XTO, and XTO/XTO have frequencies , , , , , and corresponding relative viabilities , , , , , and relative fertilities , , , , , . All genotypes, genotypic frequencies, and their corresponding parameters (relative viability, relative fertility, male germline X chromosome transmission, and female germline X chromosome recombination) are given in the mating table provided in Supplementary File 4.

To calculate genotypic frequencies in the next generation, a mating table was created that lists all genotypic frequencies of offspring produced from all 40 mating types (4 possible male genotypes 10 possible female genotypes). The full table (40 parental mating types generating 14 offspring genotypes) is given in Supplementary File 4. After correcting for the frequency and fertility of each parental mating type, as well as relative viability of each offspring class, the genotypic frequencies of reproductively mature adults in the next generation are given by system of equations:

| (A1) |

where is the sum of the right side of the system of equations and the next generation’s genotypic frequencies are denoted with primes. Iteration of this single generation system allows graphical analysis of short-term evolution of D. pseudoobscura Sex Ratio system.

The behavior of this model was examined with experimentally determined parameters and several simplifying assumptions. First, relative viability and fertility for genotypes involving XST and XSR were taken from direct measurements in Curtsinger and Feldman (1980) and are assumed to be recessive such that . Second, relative viabilities and fertilities were assumed to be products of multiplicative fitness effects; such that when the 26-Mb SR haplotype was disrupted by recombination, then and . Furthermore, relative viability and fertility of recombinant X chromosomes in the homozygous state was proportional to the fraction of the 26-Mb SR haplotype retained, such that , , , and . Following the same logic for hemizygote, relative viability and fertilities were and . All full list numerical values for viability and fertility parameters are given in Table A1. Third, the X-linked segregation distortion (male genotype-specific proportion of female offspring sired) was , , , and based on experimental estimates. Here, an averaged was used to account for polymorphic autosomal suppressors in natural populations that can alter the distortion strength of XBM. Finally, recombination rates were based on the experimental results reported in this study; however, 2 different models of recombination [reciprocal exchange due to meiotic crossing-over and unequal mitotic exchange in female germline stem cells (GSCs)] were investigated.

Meiotic crossing-over was modeled as reciprocal exchange using the experiment-wide rate of 0.00779 events per offspring for both directions of recombination (producing XBM and XTO) and (producing XST and XSR). The “back” recombination rate (heterozygous XBM/XTO females generating XST or XSR progeny) has not been experimentally estimated. However, the relevant female genotype only occurs on the order of 1 in 1,000,000 individuals in the natural population. Meiotic crossing-over produces system of Equation (A1) derived above.

Unequal mitotic exchange in the female GSCs was modeled by substituting the “forward” recombination rate ( producing XBM and XTO from XST/XSR female heterozygotes) with complementary class-specific rates (generating only XBM) and (generating only XTO) into the relevant columns of the mating table. Complementary class-specific rates ( and ) were calculated from experimental recovery rates in the protected heterozygous state (i.e. from female progeny only). The “back” recombination rate was not altered as the relevant genotype was exceedingly rare. Finally, relative viability of hemizygous XBM and XTO was estimated by deficit of recombinant male versus female progeny observed in experimental data ( and ). Therefore, the modified system of equations for unequal mitotic exchange was:

| (A2) |

where, as before, is the sum of the right side of equations, primes denote next generation’s genotypic frequencies, and the altered terms are bolded for convenience.

Thorough equilibrium and stability analysis of the full 14 variable population genetic model is beyond the scope of this article. Instead, equilibrium frequencies were solved for by iteration of the system of recursion equations. Initial genotypic frequencies were taken from Beckenbach’s (1996) direct cytological observation of SR inversion complement for 694 X chromosomes sampled from Tucson and Bear Creek, AZ, USA. The equilibrium frequencies are reported in Table 6. This procedure was then repeated with a range of initial allele frequencies (0.01–0.99) for XSR, XBM, and XTO under both alternative scenarios: meiotic crossing-over in oocyte or unequal mitotic exchange in GSCs. In all cases, the genotypic frequencies converged on the same values in less than 1,000 generations (Fig. 5).

Table A1.

Viability and fertility parameter values for the recombination extension of Edwards (1961) model.

| Viability |

Fertility |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Parameter | Estimate | Method | Parameter | Estimate | Method |

| XSTY | v1 | 1.02 | Empirical | f1 | 1.00 | Empirical |

| XSRY | v2 | 0.71 | Empirical | f2 | 1.03 | Empirical |

| XBMY | v3 | 0.80 | Calculated | f3 | 1.02 | Calculated |

| XTOY | v4 | 0.89 | Calculated | f4 | 1.01 | Calculated |

| XSTXST | v1,1 | 1.24 | Empirical | f1,1 | 0.87 | Empirical |

| XSTXSR | v1,2 | 1.00 | Defined | f1,2 | 1.00 | Defined |

| XSTXBM | v1,3 | 1.07 | Calculated | f1,3 | 0.95 | Calculated |

| XSTXTO | v1,4 | 1.15 | Calculated | f1,4 | 0.91 | Calculated |

| XSRXSR | v2,2 | 0.55 | Empirical | f2,2 | 0.68 | Empirical |

| XSRXBM | v2,3 | 0.67 | Calculated | f2,3 | 0.77 | Calculated |

| XSRXTO | v2,4 | 0.82 | Calculated | f2,4 | 0.88 | Calculated |

| XBMXBM | v3,3 | 0.72 | Calculated | f3,3 | 0.73 | Calculated |

| XBMXTO | v3,4 | 1.00 | Calculated | f3,4 | 1.00 | Calculated |

| XTOXTO | v4,4 | 0.95 | Calculated | f4,4 | 0.80 | Calculated |

Parameter is classified as “defined” if its value is set by the modeling framework, “empirical” if directly measured in Curtsinger and Feldman (1980), and “calculated” if based on the proportional division of Curtsinger and Feldman (1980) values.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material. D. pseudoobscura stocks listed in Table 1 and further described in reagent table in Supplementary File 1 are available upon request. The author affirms that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions of the article are present within the article, figures, and tables. Raw counts from the recombination experiments are provided in Supplementary File 5.

Supplemental material is available at G3 online.

Literature cited

- Adams MD, McVey M, Sekelsky JJ.. Drosophila BLM in double-strand break repair by synthesis-dependent strand annealing. Science. 2003;299(5604):265–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Golic KG, Hawley RS.. Drosophila: A Laboratory Handbook. Cold Spring Harbor, NY (USA): Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman AJ, Chandley AC.. Effects of X-rays on female germ cells of Drosophila melanogaster II. Crossing-over in the X-chromosome. Mutat Res Mol Mech Mutagen. 1965;2(6):506–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckenbach AT. Selection and the “sex-ratio” polymorphism in natural populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura. Evolution. 1996;50(2):787–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CB, Brehme KF.. The Mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Washington, DC (USA): Carnegie Institution of Washington; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Burt A, Trivers R.. Genes in Conflict. Cambridge, MA (USA): Harvard University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Courret C, Chang C-H, Wei KH-C, Montchamp-Moreau C, Larracuente AM.. Meiotic drive mechanisms: lessons from Drosophila. Proc Biol Sci. 2019;286(1913):20191430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtsinger JW, Feldman MW.. Experimental and theoretical analysis of the “sex-ratio” polymorphism in Drosophila pseudoobscura. Genetics. 1980;94(2):445–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobzhansky T, Epling C.. Contributions to the Genetics, Taxonomy, and Ecology of Drosophila pseudoobscura and Its Relatives. Washington, DC (USA): Carnegie Institution of Washington; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AWF. The population genetics of “sex-ratio” in Drosophila pseudoobscura. Heredity. 1961;16(3):291–304. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller ZL, Koury SA, Leonard CJ, Young RE, Ikegami K, Westlake J, Richards S, Schaeffer SW, Phadnis N.. Extensive recombination suppression and epistatic selection causes chromosome-wide differentiation of a selfish sex chromosome in Drosophila pseudoobscura. Genetics. 2020;216(1):205–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gethmann RC. Crossing-over in males of higher Diptera (Brachycera). J Hered. 1988;79(5):344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M, Kohl KP, Sekelsky J, Hatkevich T.. Meiotic MCM proteins promote and inhibit crossovers during meiotic recombination. Genetics. 2019;212(2):461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatkevich T, Kohl KP, McMahan S, Hartmann MA, Williams AM, Sekelsky J.. Bloom syndrome helicase promotes meiotic crossover patterning and homolog disjunction. Curr Biol. 2017;27(1):96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatkevich T, Sekelsky J.. Bloom syndrome helicase in meiosis: pro‐crossover functions of an anti‐crossover protein. Bioessays. 2017;39(9):1700073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh J-R, St Johnston D.. The origin of asymmetry: early polarisation of the Drosophila germline cyst and oocyte. Curr Biol. 2004;14(11):R438–R449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenike J. Sex chromosome meiotic drive. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 2001;32(1):25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl KP, Jones CD, Sekelsky J.. Evolution of an MCM complex in flies that promotes meiotic crossovers by blocking BLM helicase. Science. 2012;338(6112):1363–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin RC. The interaction of selection and linkage. I. General considerations; heterotic models. Genetics. 1964;49(1):49–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Jang JK, Graham J, Nycz K, McKim KS.. Two genes required for meiotic recombination in Drosophila are expressed from a dicistronic message. Genetics. 2000;154(4):1735–1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin JM, Bratu DP.. Drosophila melanogaster oogenesis: an overview. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1328:1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVey M, Andersen SL, Broze Y, Sekelsky J.. Multiple functions of Drosophila BLM helicase in maintenance of genome stability. Genetics. 2007;176(4):1979–1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus MJ. Crossing-over between the X- and Y-chromosomes in the female of Drosophila melanogaster. Z Indukt Abstamm Vererbungsl. 1936;71(1):265–275. [Google Scholar]

- Orr HA. A new linkage map of the Drosophila pseudoobscura X chromosome. Dros Inf Serv. 1995;76:127–128. [Google Scholar]

- Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ.. Biometry: The Principles and Practice of Statistics in Biological Research. New York, NY (USA): W. H. Freeman and Company; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant AH, Dobzhansky T.. Geographical distribution and cytology of “sex ratio” in Drosophila pseudoobscura and related species. Genetics. 1936;21(4):473–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng C-Y, Burel M, Cammer M, Harsh S, Flaherty MS, Baumgartner S, Bach EA.. chinmo-mutant spermatogonial stem cells cause mitotic drive by evicting non-mutant neighbors from the niche. Dev Cell. 2022;57(1):80–94.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace B. Studies on ‘sex-ratio’ in Drosophila pseudoobscura. I. Selection and ‘sex-ratio’. Evolution. 1948;2(3):189–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwick ME, Salstrom JL, Langley CH.. Genetic variation in rates of nondisjunction: association of two naturally occurring polymorphisms in the chromokinesin nod with increased rates of nondisjunction in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1999;152(4):1605–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material. D. pseudoobscura stocks listed in Table 1 and further described in reagent table in Supplementary File 1 are available upon request. The author affirms that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions of the article are present within the article, figures, and tables. Raw counts from the recombination experiments are provided in Supplementary File 5.

Supplemental material is available at G3 online.