Abstract

Introduction

ß-pancreatic cells are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection and replication; this could lead to infection-related diabetes or precipitate the onset of type 1 diabetes. This study aimed to determine the severity at diagnosis, analyzing clinical and epidemiological features at debut in children under 16 years of age in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Material and methods

A retrospective observational multicenter study was carried out in 7 hospitals of the public health network located in the south of our community. The severity at debut is compared with that of the two previous years (2018 and 2019). The level of statistical significance is set at p < 0.05.

Results

In 2020, 61 patients debuted at the 7 hospital centres. The mean age was 10.1 years (SD: 2.6), 50.8% older than 10 years. The clinical profile at diagnosis was ketoacidosis in 52.5% compared to 39.5% and 26.5% in the previous two years (p < 0.01). The mean pH (7.24 vs 7.30/7.30) and excess of bases (−11.9 vs −7.43/−7.9) was lower than in the previous two years, and the glycated haemoglobin higher (11.9 vs 11/10.6), p < 0.05. At least 10% of the patients had a positive history of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Conclusions

There has been an increase in the frequency of diabetic ketoacidosis in type 1 diabetes onset during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Type 1 diabetes, Diabetic ketoacidosis, Children, Adolescent, COVID-19

Abstract

Introducción

Las células ß-pancreáticas son susceptibles a la infección y replicación de SARS-CoV-2, lo que podría conducir a una diabetes relacionada con infección o precipitar el debut de una diabetes tipo 1. El objetivo de este estudio ha sido determinar la gravedad al diagnóstico, analizando características clínicas y epidemiológicas en el contexto de la pandemia por SARS-CoV-2 en menores de 16 años.

Material y métodos

Se lleva a cabo un estudio multicéntrico observacional retrospectivo en7 hospitales de la red pública de sanidad ubicados en el sur de nuestra comunidad. Se compara la gravedad al debut con la de los dos años previos (2018 y 2019). Se fija el nivel de significación estadística en una p < 0,05.

Resultados

En 2020 61 pacientes debutaron en los 7 centros hospitalarios. La edad media fue 10.1 años (DE: 2.6), 50.8% mayores de 10 años. La forma clínica del debut fue cetoacidosis en el 52.5% frente al 39.5% y 26.5% en los dos años previos (p < 0.01). El pH medio (7.24 vs 7.30/7.30) y exceso de bases (−11.9 vs −7.43/−7.9) fue menor que en los dos años anteriores y la hemoglobina glicada mayor (11.9 vs 11/10.6), p < 0.05. Al menos el 10% de los pacientes tenían antecedentes positivos de infección por SARS-CoV-2.

Conclusiones

Durante el primer año de pandemia COVID-19 ha habido un aumento en la frecuencia de cetoacidosis diabética como forma de debut.

Palabras clave: Diabetes tipo 1, Cetoacidosis, Niños, Adolescente, COVID-19

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes (T1DM) is an autoimmune disease involving different triggering factors: genetic, socioeconomic and environmental.1 Against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, several studies showing the susceptibility of pancreatic beta cells to SARS-CoV-2 infection and replication have been published,2 which could lead to infection-related diabetes according to the WHO classification or precipitate the onset of T1DM.3

Ketoacidosis is one of the most severe complications of T1DM that is especially prevalent in the paediatric population, particularly children under five years of age.4 Global incidence rates vary widely from country to country and range between 15% and 80% for newly-diagnosed T1DM.5 In Spain, data published to date show a frequency of 40% of newly-diagnosed patients under 15 years of age.6 In Germany and Italy7 an increased incidence of ketoacidosis in children and adolescents at the onset of T1DM has been reported.8 Some publications in Spain suggest the same findings.9 Some of the hypotheses proposed to explain this phenomenon are the relationship with the strict lockdown imposed in the first few months of the pandemic, the fear of the population going to medical centres, or the role the infection itself could have in acting as an accelerator or trigger.10, 11

This study aimed to determine the clinical severity of patients under 16 years of age at the onset of diabetes against the backdrop of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and to compare this with the two previous years as any possible relationship with COVID-19 infection.

Material and methods

A retrospective, observational, multicentre study was conducted to determine the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of patients <16 years of age with new-onset T1DM in 2020, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic. Severity at onset was compared with the two previous years (2018 and 2019). Seven public hospitals located in the south of the Community of Madrid took part: Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada, Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa (Leganés), Hospital Universitario de Móstoles, Hospital Universitario Rey Juan Carlos (Móstoles), Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Hospital Universitario del Tajo (Aranjuez) and Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina (Parla).

The first case of COVID-19 in Spain was reported on 31 January 2020 and in the Community of Madrid on 25 February 2020.

Inclusion criteria

-

-

Being under 16 years of age at the onset of T1DM.

-

-

Living in the catchment area of the participating sites in the 3 months before onset.

-

-

Clinical follow-up at any of the study's participating sites.

Exclusion criteria: not meeting any of the inclusion criteria.

Age, severity and clinical form of presentation, time since onset of cardinal symptoms, lab test parameters (blood insulin, C-peptide, haemoglobin A1c and venous pH), association with other autoimmune diseases and SARS-CoV-2 infection (PCR and/or IgG and IgM serology) were analysed upon admission.

The criteria for the diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis were taken from the ISPAD Consensus Guidelines12 (blood glucose >200 mg/dl, venous pH < 7.13 or bicarbonate <15 mmol/l, ketonaemia [blood ß-hydroxybutyrate ≥3 mmol/l] or moderate or severe ketonuria).

Three age groups were established: 0−4 years, 5−9 years and 10−15 years.

The software EPIDAT 4.0. was used. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation. If the variable does not fit a normal distribution, it is expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Qualitative variables are expressed as frequencies. Quantitative variables were compared using the Student's t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). In contrast, qualitative variables were compared using the Chi-squared test and applying Fisher's exact test when required. The level of statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

The study was approved by the Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada Independent Ethics Committee and seconded by the Principal Investigator.

Results

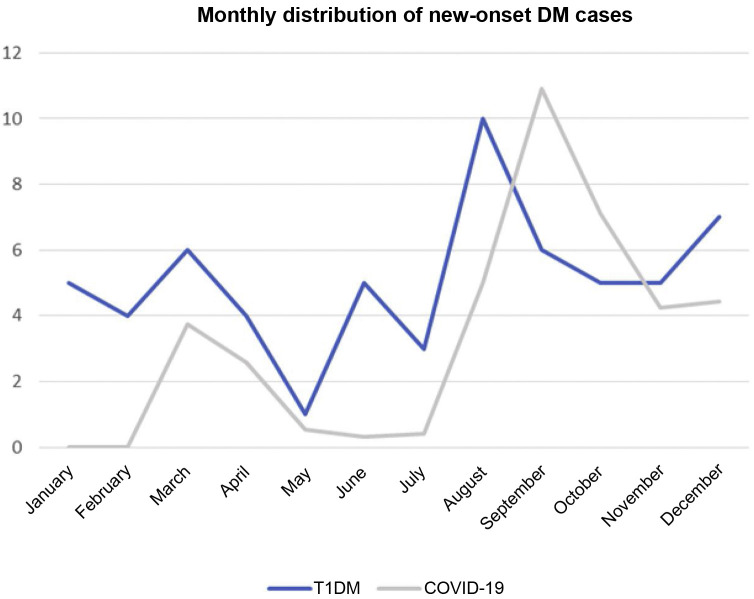

In 2020, 61 patients were diagnosed with T1DM at the seven hospitals. Some 24.6% of the patients came from a single centre. The mean age was 10.1 years (SD: 2.6; IQR: 7.2–13.5). Regarding age group, 36.1% of patients were aged 0–4 years, 13.1% 5–9 years and 50.8% >10 years. In total, 54.1% of the study population were female. Overall, 75.4% were of Spanish origin, 11.5% from North Africa, 6.5% from Eastern Europe and one patient was from Latin America. Some 31.1% of cases occurred in the third quarter of the year and 24.6% in the first (Fig. 1 ).

Figure 1.

Monthly distribution of new-onset T1DM cases and new COVID-19 cases in the Community of Madrid (new cases × 104).

In 2018 and 2019, data were collected from 43 and 34 patients, respectively, with a mean age of 8.7 years (SD: 3.9) and 8.8 years (SD: 3.8), which was lower than the mean age recorded in 2020 (p < 0.05). In total, 69.8% and 79.4%, respectively, were of Spanish origin.

Signs and symptoms

The most common symptom was polyuria (83.6%), followed by polydipsia (80.3%). In both cases, approximately half of patients reported a time since onset of 2 weeks or less (51% and 55%, respectively). Some 59.2% reported weight loss; the least common symptom (34.4%) was polyphagia.

The initial clinical form was ketoacidosis in 52.5% of patients and ketosis without acidosis in 32.8%. In total, 16.4% required admission to the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU), with no significant differences in presentation between the different age groups (Table 1 ). However, in contrast to the findings for previous years ketoacidosis was reported in just 39.5% and 26.5% of patients respectively (p < 0.01). Table 2 details the initial clinical forms in 2020 and the previous two years.

Table 1.

Severity of presentation by age group.

| 2020 | 0−4 years (n = 8) | 5−9 years (n = 22) | 10−15 years (n = 31) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ketoacidosis | 75% | 54.5% | 45.2% |

| Mean pH (SD) | 7.16 (0.21) | 7.24 (0.12) | 7.23 (0.14) |

| ICU | 37.5% | 13.6% | 12.9% |

SD, standard deviation; ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 2.

Form of presentation (comparison by year).

| 2018 (n = 43) | 2019 (n = 34) | 2020 (n = 61) | Stat. sig. (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketoacidosis | 17 (39.5%) | 9 (26.5%) | 32 (52.5%) | p = 0.008 |

| Ketosis | 14 (32.6%) | 14 (41.2%) | 21 (34.4%) | |

| Hyperglycaemia | 12 (27.9%) | 9 (26.5%) | 3 (4.9%) | |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 2 (5.9%) | 5 (8.2%) |

Stat. sig., Statistical significance.

In total, 34.4% received subcutaneous insulin from the onset, and in those who required IV infusion, the mean time was 13 h (SD: 9.3 h). It was maintained for >24 h in 9.8% of patients.

In 2018 and 2019, the most common symptom was also polyuria, reported by 95.3% and 91.2% of patients, respectively. Time since onset was 2 weeks or less in 45.2% and 55% of cases. Table 3 details the symptoms and time since onset.

Table 3.

Cardinal symptoms and time since onset.

| Polyuria |

Polydipsia |

Polyphagia |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 (n = 61) | 2019 (n = 34) | 2018 (n = 43) | 2020 (n = 61) | 2019 (n = 34) | 2018 (n = 43) | 2020 (n = 61) | 2019 (n = 34) | 2018 (n = 43) | |

| No | 6 (9.8%) | 3 (8.8%) | 2 (4.7%) | 9 (14.7%) | 9 (26.5%) | 9 (21%) | 36 (59.1%) | 15 (44.1%) | 19 (44.2%) |

| Yes 0−2 | 51 (83.6%) | 31 (91.2%) | 41 (95.3%) | 49 (80.3%) | 25 (73.5%) | 34 (79%) | 21 (34.4%) | 16 (47.1%) | 24 (55.8%) |

| weeks | 26 (51%) | 14 (45.2%) | 22 (55%) | 27 (55.1%) | 14 (56%) | 19 (55.9%) | 15 (71.4%) | 8 (50%) | 11 (45.8%) |

| 2−4 weeks | 16 (31.4%) | 8 (25.8%) | 9 (21.9%) | 14 (28.6%) | 5 (20%) | 7 (20.6%) | 3 (14.3%) | 5 (31.2%) | 4 (16.7%) |

| 1−2 months | 7 (13.7%) | 5 (16.1%) | 8 (19.5%) | 5 (10.2%) | 4 (16%) | 7 (20.6%) | 2 (9.5%) | 1 (6.2%) | 8 (33.3%) |

| >2 months | 0 | 2 (5.9%) | 2 (6.4%) | 0 | 1 (4%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 | 1 (6.2%) | 1 (4.2%) |

Clinical chemistry, autoimmunity and related conditions

Acid-base balance at diagnosis: in 2020, the mean pH was: 7.24 (SD: 0.01), the mean bicarbonate was 14.7 mEq/l (SD: 7.4) and the mean base excess was –11.9 (SD: 9.33). The mean glycated haemoglobin (DCCT) was 11.9% (SD: 2.2) and the mean C-peptide was 0.62 ng/mL (SD: 0.5; median 0.5 ng/mL and IQR: 0.3−0.7) (see Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Acid-base balance and pancreatic reserve.

| 2018 (n = 43) | 2019 (n = 34) | 2020 (n = 61) | Stat. sig. (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean pH (SD) | 7.30 (0.11) | 7.30 (0.15) | 7.24 (0.01) | p = 0.002 |

| Mean bicarbonate mEq/l (SD) | 17.5 (6.74) (n = 42) | 16.99 (7.74) (n = 31) | 14.7 (7.4) (n = 54) | p = 0.14 |

| BE mEq/l (SD) | (n = 41) –7.9 (7.9) | (n = 29) –7.43 (9) | (n = 53) –11.9 (9.33) | p = 0.035 |

| Mean HbA1c % (SD) | (n = 32) 10.6 (2.8) | (n = 39) 11 (2.5) | (n = 57) 11.9 (2.2) | p = 0.04 |

| Mean C-peptide ng/mL (SD) | (n = 42) 0.78 (0.55) | (n = 30) 0.8 (0.47) | (n = 53) 0.62 (0.5) | p = 0.192 |

BE, base excess; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; SD, standard deviation; Stat. sig., statistical significance.

In 2020, the mean pH at diagnosis was lower than in the previous two years (p < 0.01), as was the mean base excess (p < 0.05), while mean glycated haemoglobin was higher (p < 0.05).

T1DM-related antibodies were positive in all cases except one, in which they were not measured. Around 10% of patients (6/61) also had thyroiditis at diagnosis, while three patients had coeliac disease-related antibodies.

Coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome

Fig. 1 shows new-onset diabetes cases, and the incidence of COVID-19 in the Community of Madrid superimposed.

In total, the onset of 85.2% (n = 52) of patients diagnosed in 2020 was after the first reported case of COVID-19 in the Community of Madrid. An RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 was performed in 40 patients upon admission, which was positive in three cases. Of those patients with negative RT-PCR, one had positive IgG serology, and in another case, both parents were infected at the time. Therefore, five patients (9.6%) had a positive history.

Discussion

2020 saw an increase in the severity of the onset of T1DM in children under 16 years of age (higher frequency of ketoacidosis, lower pH, lower base excess [BE] and higher glycated haemoglobin), as has been reported in other countries.13, 14 Although the association with lockdown and the fear of going to medical centres has been one of the hypotheses proposed to explain this8 the time since onset of symptoms was <2 weeks in slightly more than 50% of cases, with no differences compared to the previous years, suggesting that there was no delay in receiving health care, which leads us to believe that there must be other factors involved in this greater severity at onset. Moreover, no differences have been found in symptom duration between patients presenting with or without ketoacidosis.4 One feature of healthcare in the Autonomous Community of Madrid was the partial closure of primary care during the first months of the pandemic to support the care of patients with COVID-19 at the Hospital de Emergencias Enfermera Zendal, as well as the subsequent restriction of face-to-face consultations in favour of telephone appointments. This lack of primary care15 could have affected aspects such as severity of presentation.16

Although no significant differences were found, there was a tendency in our study towards lower C-peptide values in 2020 compared to the two previous years (0.62 vs 0.78/0.8) (ng/mL), a finding that goes hand in hand with the higher incidence of ketoacidosis17 and would translate into a lower residual capacity for endogenous insulin production.

During the months of March, April and May (21 March to 6 May), emergency paediatric care was redistributed to two main hospitals in the Community of Madrid. However, some patients continued to go to their nearest referral hospital. More cases in our population were recorded in 2020 than in 2018 or 2019. Patient displacement to other hospitals could be one of the reasons why the mean age of our patients was greater in 2020 than in the two previous years (10.1 years versus 8.7 and 8.8 years; p < 0.05) 9 even though other series have recorded a younger age at diagnosis during the COVID-19 pandemic.18

Children under five years of age are the most susceptible to ketoacidosis and the most likely to require intensive care, which was confirmed by our data (75% ketoacidosis). However, no significant differences were found due to the small sample size.

Data from the literature regarding SARS-CoV-2-precipitated T1DM in children and adolescents are contradictory.7, 19, 20 In our series, of the 40 patients with onset during the COVID-19 pandemic and who underwent some kind of diagnostic test for SARS-CoV-2 infection, up to 12.5% of cases were in some way associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. In December 2020, the overall prevalence in Spain among 16-year-old adolescents was around 5%, according to the ENECOVID seroprevalence study21 almost half the figure obtained from our sample. Although it is impossible to conclude the small sample size and specific geographical area, we believe these data should be analysed as part of the national figures to confirm this result. Contrary to this finding, no parallelism was observed between the COVID-19 incidence graphs in the Community of Madrid and newly-diagnosed T1DM (Fig. 1). One aspect to analyse in future studies is the severity of T1DM cases in patients with a history of infection. Owing to the small number of cases, this could not be evaluated in our study.

The limitations of this paper are those characteristic of a retrospective study, namely lost and/or missing data. The time since the onset of initial symptoms is not very precise due to the subjective and retrospective nature of the data collection. It is also impossible to confirm whether these symptoms may have gone unnoticed, been attributed to lockdown, or even been detected earlier due to stricter control. Even so, given that most of the variables analysed are biochemical parameters, interpretation and selection bias can be ruled out, rendering these results valid. We cannot determine the incidence of new-onset T1DM as some diagnosed cases will have been seen at other centres, meaning that these data are not real and may underestimate the actual incidence.

Conclusions

In 2020, 52.5% of patients had ketoacidosis at onset, representing an increase in this form of presentation and therefore an increase in severity.

Between 10% and 12.5% of patients had a positive history of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A national registry of newly-diagnosed T1DM cases, their severity and their possible association with SARS-CoV-2 infection are just one of the measures that need to be implemented as part of the ketoacidosis prevention policies.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rewers M., Ludvigsson J. Environmental risk factors for type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2016;387(10035):2340–2348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30507-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lima-Martínez M.M., Carrera Boada C., Madera-Silva M.D., Marín W., Contreras M. COVID-19 and diabetes: a bidirectional relationship. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2021;33(3):151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.arteri.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Müller J.A., Groß R., Conzelmann C., Krüger J., Merle U., Steinhart J., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infects and replicates in cells of the human endocrine and exocrine pancreas. Nat Metab. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00347-1. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33536639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Usher-Smith J.A., Thompson M.J., Sharp S.J., Walter F.M. Factors associated with the presence of diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of diabetes in children and young adults: a systematic review. BMJ. 2011;7:d4092. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Große J., Hornstein H., Manuwald U., Kugler J., Glauche I., Rothe U. Correction: incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis of new-onset type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents in different countries correlates with Human Development Index (HDI): an updated systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Horm Metab Res. 2018;50(3):e2. doi: 10.1055/a-0584-6211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oyarzabal Irigoyen M., García Cuartero B., Barrio Castellanos R., Torres Lacruz M., Gómez Gila A.L., González Casado I., et al. Ketoacidosis at onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus in pediatric age in Spain and review of the literature. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2012;9(3):669–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabbone I., Schiaffini R., Cherubini V., Maffeis C. Scaramuzza A and the diabetes study group of the italian society for pediatric endocrinology and diabetes. Has COVID-19 delayed the diagnosis and worsened the presentation of type 1 diabetes in children? Diabetes Care. 2020;43(11):2870–2872. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamrath C., Mönkemöller K., Biester T., et al. Ketoacidosis in children and adolescents with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. JAMA. 2020;324(8):801–804. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Güemes M., Storch-de-Gracia P., Enriquez S.V., Martín-Rivada Á, Brabin A.G., Argente J. Severity in pediatric type 1 diabetes mellitus debut during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2020;33:1601–1603. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2020-0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boddu S.K., Aurangabadkar G., Kuchay M.S. New onset diabetes, type 1 diabetes and COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(6):2211–2217. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gentile S., Strollo F., Mambro A., Ceriello A. COVID-19, ketoacidosis, and new-onset diabetes: might we envisage any cause-effect relationships among them? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:2507–2508. doi: 10.1111/dom.14170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfsdorf J.I., Glaser N., Agus M., Fritsch M., Hanas R., Rewers A., et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: diabetic ketoacidosis and the hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Pediatric Diabetes. 2018;19(Suppl 27):155–177. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loh C., Weihe P., Kuplin N., Placzek K., Weihrauch-Blüher S. Diabetic ketoacidosis in pediatric patients with type 1- and type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Metabolism. 2021;122 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregg E.W., Sophiea M.K., Weldegiorgis M. Diabetes and COVID-19: population impact 18 months into the pandemic. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(9):1916–1923. doi: 10.2337/dci21-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albañil Ballesteros M.R. Pediatría y COVID-19. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2020;22:125–128. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGlacken-Byrne S.M., Drew S.E.V., Turner K., Peters C., Amin R. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is associated with increased severity of presentation of childhood onset type 1 diabetes mellitus: a multi-centre study of the first COVID-19 wave. Diabet Med. 2021;38(9) doi: 10.1111/dme.14640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szypowska A., Skórka A. The risk factors of ketoacidosis in children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatric Diabetes. 2011;12:302–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2010.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dilek S.Ö, Gürbüz F., Turan İ, Celiloğlu C., Yüksel B. Changes in the presentation of newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes in children during the COVID-19 pandemic in a tertiary center in Southern Turkey. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2021;34(10):1303–1309. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2021-0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domínguez J.A., Tello M.V., Tasayco J., Coronado A. Cetoacidosis diabética severa precipitada por COVID-19 en pacientes pediátricos: reporte de dos casos. Medwave. 2021;21(3):e8176. doi: 10.5867/medwave.2021.03.8176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Messaaoui A., Hajselova L., Tenoutasse S. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in new-onset type 1 diabetes in children during pandemic in Belgium. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2021;34(10):1319–1322. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2021-0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollán M., Pérez-Gómez B., Pastor-Barriuso R., Oteo J., Hernán M.A., Pérez-Olmeda M., (ENE-COVID Study Group), et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE-COVID): a nationwide, population-based seroepidemiological study. Lancet. 2020;396(10250):535–544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31483-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]