Abstract

Background

Food-related quality of life (FRQoL) encompasses the psychosocial elements of eating and drinking. The FRQoL of children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease has not yet been assessed. This study aimed to evaluate the utility of the validated FR-Qol-29 instrument in children with Crohn’s disease (CD).

Methods

Children diagnosed with CD, a shared home environment healthy sibling, and healthy control subjects 6 to 17 years of age were recruited to this single-center, prospective, cross-sectional study. Children or their parent or guardian completed the FR-QoL-29 instrument. Internal consistency was assessed by completing Cronbach’s α. Construct validity was established by correlating the CD FR-QoL-29 sum scores with the Physician Global Assessment and Pediatric Crohn Disease Activity Index scores. The discriminant validity was analyzed using a 1-way analysis of variance, and a Spearman’s correlation coefficient test was completed to identify any correlations associated with FRQoL.

Results

Sixty children or their parent or guardian completed the FR-QoL-29 instrument (10 children in each subgroup). The internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach’s α = 0.938). The mean FR-QoL-29 sum scores were 94.3 ± 27.6 for CD, 107.6 ± 20 for siblings, and 113.7 ± 13.8 for control subjects (P = .005). Those with higher disease activity had worse FRQoL (Physician Global Assessment P = .021 and Pediatric Crohn Disease Activity Index P = .004). Inflammatory bowel disease FR-QoL-29 sum scores correlated with weight (P = .027), height (P = .035), body mass index (P = .023), and age (P = .015).

Conclusions

FRQoL is impaired in children with CD. Healthy siblings also have poorer FRQoL than control subjects. Several clinical factors are associated with poorer FRQoL in children with CD including age and level of nutritional risk (weight, height, and body mass index). Further research is required validate these findings and to develop strategies for the prevention or treatment of impaired FRQoL in children with CD.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic incurable inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract, with Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis being the 2 main phenotypes.1 The prevalence of IBD continues to increase worldwide, including in children and adolescents.2 IBD developing in children typically impacts adversely on growth, nutritional status, quality of life (QoL), and school attendance.3 Malnutrition is common in pediatric CD, with up to 60% being underweight at the time of diagnosis.4,5 Linear growth can also be adversely affected by disease activity,6 with a reported incidence of growth failure at diagnosis between 15% and 40% in pediatric-onset CD.7,8 Weight loss or poor weight gain may reflect reduced oral intake, early satiety, or excess gastrointestinal losses.9

Food not only is a source of nutrients for the growing child, but also performs important psychosocial functions, such as socialization and peer learning, and food is at the center of many celebrations (eg, birthdays, religious festivals) and cultural identities, and is widely used in child reward.10 Parents of children with IBD may restrict their child’s diet irrespective of medical indications or objective reasons, and children with IBD may subsequently have differing diets from their healthy peers.11 Consequent to the alterations in diet in children with IBD, these important psychosocial functions of food and eating can be disrupted, as they may miss socialization and enjoyment around food: this might lead to feelings of exclusion from social interactions involving eating and drinking, resulting in stress and anxiety.12 This has relevance in children and adolescents with IBD, as children build lifelong relationships and learn about socialization with their peers. In turn, this may contribute to the increased rates of depression and anxiety noted in young people with IBD,13 as has been observed in children with type 1 diabetes 14-17.

Validated malnutrition screening tools18-21 and health-related QoL tools22-25 are used clinically in children; however, there are no tools that specifically target the broader psychosocial factors of eating and drinking and the impact on quality of life in children with IBD. Food-related QoL (FRQoL) can be measured in adults using the FR-QoL-29 instrument.26 This instrument was developed from qualitative interviews with adults with IBD26 and was validated in a large population of adults with IBD.27 Studies utilizing this tool show that FRQoL is commonly reduced in adults with IBD and is associated with frequent relapse, IBD-related distress, higher disease activity, and lower intake of some nutrients.28,29

There are currently no data concerning the impact of IBD on FRQoL of children. The aims of the current study were to evaluate the utility of the FR-QoL-29 instrument in children with CD and to use this instrument to measure FRQoL of children with CD, healthy siblings (who share a food environment but do not have CD), and healthy control subjects (who share neither a food environment nor CD). It was hypothesized that the group of children with CD would score lowest on FR-QoL-29 due to the effect of IBD on FRQoL; that healthy siblings would score higher, as they do not have disease but share the food environment; and that healthy control subjects would score highest in the absence of IBD. Given that the FR-QoL-29 was specifically developed and validated for use in adults with IBD, further analyses were completed to ascertain the suitability of the tool to children.

Methods

Participants

Three cohorts of children 6 to 17 years of age living within the Canterbury region of New Zealand were recruited: children diagnosed with CD, their healthy siblings, and healthy unrelated children. A goal of 60 participants (20 in each subgroup) was set as the recruitment sample size.

Cases were included in this study if they had a confirmed diagnosis of CD30 at least 4 months prior to recruitment and if they were eating a “normal” habitual diet. Healthy siblings were eligible if they resided in the same household as their sibling with CD, to ensure that food exposure and environment was the same. Healthy unrelated children were included as control subjects who neither shared the same food environment nor had CD.

Exclusion criteria for children with CD included those currently receiving treatment with exclusive enteral nutrition or parenteral nutrition support, as this would not reflect a “normal” diet and prevent accurate assessment of their FRQoL. Any participants with underlying chronic medical conditions or comorbidities including obesity, diabetes, or celiac disease, which might impact on FRQoL, were excluded. Siblings who resided between split households were excluded due to lack of a shared food environment.

Children with CD and their healthy siblings were recruited at the time of their routine IBD clinic appointment. Healthy control subjects were invited to participate via email or verbal initiation and included colleagues of the research team and parents from the local community. Verbal and written information was provided to children prior to participation. Consent was obtained for children <10 years of age by the child’s parent or guardian, and those over 10 years of age provided independent consent to participate. The study was approved by University of Otago Health Ethics Committee reference H17/146.

FR-QoL-29 Instrument

The FR-QoL-29 is a unidimensional scale that measures FRQoL. It was developed using verbatim quotes from adults with IBD and validated against a cohort of healthy adults and adults with asthma.26 The FR-QoL-29 consists of 29 questions with a 5-point Likert response scale ranging from 1 (definitely agree) to 5 (definitely disagree). The maximum FR-QoL-29 sum score of 129 indicates superior FRQoL, whereas a score of 45 represents the poorest FRQoL. The FR-QoL-29 encompasses general FRQoL and cognitive and affective aspects of FRQoL, with items referring to concentration, frustration, and not knowing which foods will affect symptoms; the positive aspects of eating and drinking; and eating foods that triggered symptoms.26 Completed surveys were scanned and returned via email to the study investigator for analyses.

The FR-QoL-29 instrument was distributed to all consenting participants or their parent or guardian in an unaltered version26 at the time that consent was obtained to take home and complete later, to prevent disruption to the routine clinic, or they were sent home with the parent or guardian of the healthy control subjects. Siblings and healthy control subjects were given the FR-QoL-29 unIBD instrument,26 which was adapted to measure the same constructs of FRQoL as the FR-QoL-29 but with all mentions of IBD removed.

A readability test on the FR-QoL-29 instrument was completed using Microsoft Word to determine an appropriate age for children to be able to independently complete the FR-QoL-29 instrument without adult guidance. The readability score was 10.2 years. Given that the FR-QoL-29 was created specifically for adult patients, it was decided that children under 10 years of age would likely require assistance from their parent or guardian to complete the instrument and that children over 10 years of age would be able to complete this independently. This was discussed with the participant or parent or guardian at the time of survey distribution and was left to the discretion of the family to decide who completed the survey.

A separate questionnaire asked participants to provide feedback on the applicability of the FR-QoL-29 for children. Participants were asked to provide feedback on the overall instrument (in free text), any specific questions that they found difficult, and what they would do to improve the instrument.

Anthropometry

Participants and their parents were asked to report the participant’s height and weight at the time of survey completion. Each child’s body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) was calculated and converted to Z scores using the World Health Organization (WHO) anthropometry cutoff values.31 Nutritional risk was defined using the WHO BMI Z-score index for 5 to 19 years of age: “healthy weight/low risk”>-1 to <+1 SD, “thinness/moderate risk” <-2 SD, and “severe thinness/high risk” <-3 SD.

Disease Activity

Disease activity at the time of recruitment was determined by the clinical team. Disease activity was recorded using both the Physician Global Assessment (PGA) 32 and the Pediatric Crohn Disease Activity Index (PCDAI).33 The PGA provided an overall assessment of disease activity using a 0 to 3 scale (0 = nonactive disease; 1 = mild disease activity; 2 = moderate disease activity; 3 = severe disease activity). The PCDAI provided a specific assessment of disease activity, measured with a 0 to 100 scale (<10 indicating remission, 100 indicating the most severe grade of activity).33

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). The internal consistency of the questionnaire items was assessed by correlating each item with every other item. A Cronbach’s α of >0.7 was used as the cutoff for good internal consistency.34 Construct validity was established by comparing FR-QoL-29 sum scores with PGA and PCDAI scores to assess the relationship between FRQoL and disease activity. This was undertaken for the CD group only, and was performed by correlating (Spearman’s) sum scores of FR-QoL-29 with the PGA and PCDAI, and by comparing the sum scores of those in remission (PGA 0, PCDAI <10) with those with any degree of disease activity (PGA ≥1, PCDAI ≥10).

Discriminant validity was measured by comparing FR-QoL-29 sum scores of the CD, sibling, and healthy control groups using 1-way analysis of variance. A pairwise comparison t test was completed to compare FRQoL scores between groups. Results were considered statistically significant at the .05 level. Spearman’s nonparametric correlation coefficient test was completed to determine any relationships between FR-QoL-29 sum scores and age, sex, weight, height, and BMI.

Feedback statements were qualitatively assessed using content analysis,35 whereby participant responses were categorized into 3 groups corresponding with the 3 questions from the feedback survey. These were tallied and individual responses were reported.

Results

Study Participants

Sixty children and adolescents 6 to 17 years of age were recruited. Twenty children with CD, 20 of their healthy siblings living in the same household, and 20 healthy control subjects completed the FR-QoL-29 questionnaire. Sixteen (80%) children with CD, 17 (85%) healthy siblings, and 20 (100%) healthy control subjects completed the FRQoL-29 themselves. The remaining FR-QoL-29 instruments were completed by parents.

The study cohort included more females than males, and 5 children in the CD group were at “nutritional risk” (Table 1). The 3 groups did not differ according to age, sex, or BMI (P >.05 for all tests) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 3 study participant groups

| Children With Crohn’s Disease (n = 20) | Siblings (n = 20) | Control Subjects (n = 20) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 10.9 ± 3.6 | 11.9 ± 3.0 | 11.2 ± 3.0 |

| Male | 8 (40) | 9 (45) | 9 (45) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 17.7 ± 2.6 | 18.4 ± 2.9 | 18.7 ± 3.1 |

| Nutritional risk | |||

| Low risk | 15 (75) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) |

| Medium risk | 3 (15) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| High risk | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Previous IBD surgery | 2 (10) | – | – |

| Years since diagnosis | 2.4 (1.9-6.3) | – | – |

| PGA score | |||

| 0 (remission) | 13 (65) | – | – |

| 1 (mild) | 3 (15) | – | – |

| 2 (moderate) | 3 (15) | – | – |

| 3 (severe) | 1 (5) | – | – |

| PCDAI score | |||

| <10 (remission) | 15 (75) | – | – |

| 10-25 (mild) | 3 (15) | – | – |

| 25-40 (moderate) | 1 (5) | – | – |

| >40 (severe) | 1 (5) | – | – |

| Concurrent therapies | |||

| Infliximab | 1 (5) | – | – |

| Thiopurines | 15 (75) | – | – |

| Maintenance | 4 (20) | – | – |

| Enteral nutrition only | – | – | |

| Other | |||

| Prior resection | 1 (5) | – | – |

| >1 disease flare since 2018 | 1 (5) | – | – |

Values are mean ± SD, n (%), or mean (range). BMI was defined using the World Health Organization standard indices. Nutritional risk was defined by the World Health Organization BMI Z score for individuals 5-19 years of age.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; PCDAI, Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index; PGA, Physician Global Assessment.

Internal Consistency

Internal consistency was excellent for the FR-QoL-29 (Cronbach’s α = 0.938).

Discriminant Validity

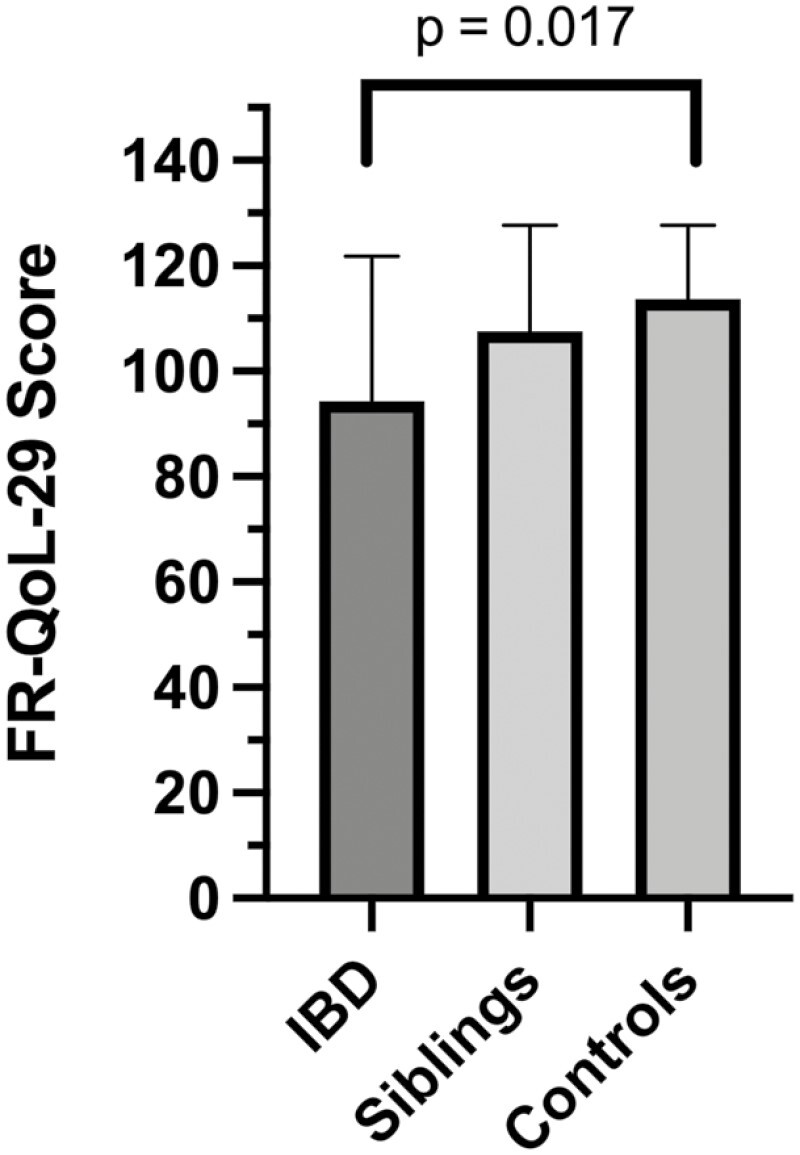

FR-QoL-29 was significantly different across the CD, sibling, and healthy control groups (P = .017). Following pairwise comparisons, FRQoL was lower in patients with CD (mean 94.3 ± 27.6) compared with both the sibling (mean 107.6 ± 20; P = .052) and healthy control subjects (mean 113.7 ± 13.8; P = .005). There were no differences between healthy siblings and healthy control subjects (P = .368) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean ± SE FR-QoL-29 sum scores for patients with Crohn’s disease, siblings, and healthy control subjects. Mean ± SD FR-QoL-29 sum score differences between groups were 94.3 ± 27.6 for the CD group compared with both the sibling group (107.6 ± 20; P = .052) and healthy control subject group (113.7 ± 13.8; P = .005). IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

If a child selected “neither agree nor disagree” as their answer to a question on the FR-QoL-29 instrument, a value of 3 would still be generated as their score for this question. In this study, this option was selected, on average, 2.8 times out of the 29 questions in the FR-QoL-29, leading to a possible sum score fluctuation of 8.4 on average.

There were no observed differences between FRQoL and the number of years since the child was diagnosed with CD (P = .204) or sex (P = .784). In the CD group, there was a significant correlation coefficient between CD FR-QoL-29 sum scores and weight (Spearman’s ρ = 0.493, P = .027), height (Spearman’s ρ = 0.474, P = .035), BMI (Spearman’s ρ = 0.506, P = .023), and age (Spearman’s ρ = 0.534, P = .015).

Construct Validity

Patients with more active disease had worse FRQoL when assessed by the PGA (Spearman’s ρ = -0.511, P = .021) or PCDAI (Spearman’s ρ = -0.617, P = .004). Using PCDAI scores, FRQoL was worse in the 5 children with moderate or high disease activity (68.50 ± 17.5) compared with the 15 children in remission or with low disease activity (105.29 ± 23.4; P = .003).

Participant and Parental Feedback

A total of 31 feedback statements were received from 17 (85%) cases, 6 (30%) siblings, and 8 (40%) control subjects. Of these, 9 comments suggested that the FR-QoL-29 should be shortened for children, and 3 statements reported that participants found the questions repetitive in nature. Large, the comments suggested that question 16 (Q16) (“I have had to concentrate on what food I buy because of my IBD”) was “not applicable” to children.

Two children with CD commented that Q1 (“I have regretted eating and drinking things which have made my IBD symptoms worse”) and Q2 (“My enjoyment of a particular food or drink has been affected by the knowledge that it might upset my digestion”) were difficult to understand. Q19 (“I have felt that I need to know what is in the food I am eating due to my IBD”) and Q29 (“I have had to work hard to fit my eating habits in around my activities during the day”) were also specifically addressed as being difficult to answer.

Regarding the time frame of the FR-QoL-29 questions, 2 people suggested that the time frame of the questionnaire should be expanded from “in the past 2 weeks” to “in the past 4 weeks.” The remaining comments were positive and included 4 comments that suggested that participants were excited about this ongoing research and grateful that this area of research was being assessed.

Discussion

This is the first study to assess FRQoL in children with CD using the FR-QoL-29 instrument. The FR-QoL-29 instrument was developed to measure the magnitude of the psychosocial factors relating to food in the lives of adults with IBD.26 However, it was not known whether children with IBD have these same concerns. The current study has shown that the FR-QoL-29 effectively measured FRQoL in a group of children with CD and that children with CD have lower FRQoL than their siblings and healthy children.

Previous research has indicated that children with IBD may self-restrict their food-intake due to their IBD-related symptoms or out of fear that certain foods may trigger symptoms.6,36 A recent cross-sectional study used the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) to compare food intake in a group of 68 children with IBD with others without IBD.36 They showed that food intake is inadequate for nutrients in children with IBD without the use of supplements including carbohydrates (75% of RDA), calcium (49% of RDA), and several micronutrients, which together may have negative impacts on a child’s normal growth and development. However, there is currently a paucity of data to assess the reasons why children with IBD have different dietary habits compared with those children without IBD and whether these differences may be partially attributed to psychosocial or disease factors.

The previous FR-QoL-29 validation study in adults showed that this instrument has excellent discriminant validity, suggesting that this instrument is measuring a phenomenon related to living with IBD, rather than related simply to experiencing a long-term condition.26 The direction and magnitude of the correlations between the FR-QoL-29 and several food-related, generic, and disease-specific QoL measures indicated excellent concurrent validity in a previous study in adults.26 Previous studies have shown a significant relationship between worse disease activity and lower FR-QoL-29,26-29 and this was also seen in the present study. The strong correlations indicate that a construct like, but unique from, disease activity is being measured by the FR-QoL-29 in children with IBD.

There were significant correlations between FR-Qol-29 sum scores and weight, height, age, and BMI for the children with CD in the current study, which suggests that nutritional screening may be a useful clinical indication of FRQoL given that those with lower weights, shorter stature, and subsequently lower BMI had lower scores on the FR-QoL-29 instrument. Furthermore, as age increased in this study cohort, so did FR-QoL-29 sum scores, indicating that older children may develop improved coping strategies in relation to food and their dietary intake over time. This phenomenon has been observed in other chronic diseases such as type 1 diabetes mellitus37 in which older children more frequently use techniques such as wishful thinking and cognitive restructuring, distraction, social support, problem solving, and emotional regulation. Thus, the psychosocial aspects of eating and drinking have additional impacts on nutrition in a range of chronic diseases.37

Although the present study showed that the FR-QOL-29 measured the same constructs in children as it does in adults with IBD, parental feedback suggested that particular questions may be less applicable to children or may be worded in a way that children may find difficult to understand. The participant and parental feedback expressed concerns that the FR-QoL-29 was too long for children and that certain questions were less relevant to children. Other statements suggested that children found it difficult to relate their emotions with eating experiences, and others found the wording of certain questions difficult to interpret. Children are developing their emotional intelligence,38 and subsequently, certain FR-QoL-29 questions may be too advanced or complicated for a child’s emotional capacity and level of development.

Previous research indicates that both the nutritional and the psychosocial aspects of eating and drinking are important to adults with IBD.39,40 It has been conveyed that family celebrations and religious occasions are “no longer joyful” because of food restrictions related to fear of relapse.26 Furthermore, the anxiety related to the impact of eating on bowel function can restrict travel and autonomy due to the perceived need to be near a toilet.41 This study showed similar results with lower FR-Qol-29 sum scores for children with CD than for healthy control subjects. It is likely that low FRQoL in children with IBD may continue into adulthood, suggesting that FRQoL could be a target for interventions from an early age.

Prior research investigating generic QOL has determined that children with CD have poorer QoL compared with healthy children, owing to disease symptoms.42 These symptoms may affect the psychological well-being of children with CD through a lack of social integration and poor social functioning.43 A child with CD often has difficulty maintaining social activities44 due to both the psychological burden of disease and gut symptoms. Moody et al45 reported that 60% of children have regular school absences, 60% are often unable to leave the house, 70% are not able to participate in routine sports, 40% are concerned about going on holidays, and 50% are unable to regularly be social or play with their friends. All these difficulties may have serious adverse effects on the QoL of these children. Therefore, the inclusion of items on the FR-QoL-29 relating to socializing and the cognitive and emotional factors related to eating and drinking in IBD allows for these important constructs to be measured in a valid way.

This study had several limitations. First, the sample size of 60, of whom only 20 had CD, is relatively small. No prior data were available to support a sample size calculation. Despite this number of respondents, the data arising demonstrated clear differences between groups. Second, only children with CD were recruited into this study; therefore, the FRQoL in children with ulcerative colitis is unknown. Third, as the current study evaluated FRQoL at 1 time point, the longitudinal effects of disease or treatments upon FRQoL were not ascertained. Last, no data on socioeconomic status of the study cohorts were collected; therefore, this may potentially confound FR-QoL-29 sum scores within and between groups. However, this was the first study to use the FR-QoL-29 instrument in children with CD and make FRQoL comparisons with relevant control groups.

Conclusions

This is the first study to assess FRQoL in children with CD using the IBD-specific and validated FR-QoL-29 instrument. The FR-QoL-29 instrument successfully measured the FRQoL in these children with CD, their siblings, and healthy children. Children with CD have significantly lower FRQoL than both their healthy peers and their siblings with whom they share a food environment. Children’s age and nutritional risk were correlated with poorer FRQoL. There is a pressing need to clinically acknowledge the psychometric consequences of disease imposed on children with IBD so that they may be offered appropriate management options. Further studies are required to evaluate the FR-Qol-29 instrument in wider groups of children with CD, and if the FR-QOL-29 instrument is to be used with children, validation of a “child friendly” version may be necessary.

Contributor Information

Stephanie C Brown, Department of Paediatrics, University of Otago Christchurch, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Kevin Whelan, Department of Nutritional Sciences, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom.

Chris Frampton, Department of Medicine, University of Otago Christchurch, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Catherine L Wall, Department of Medicine, University of Otago Christchurch, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Richard B Gearry, Department of Medicine, University of Otago Christchurch, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Andrew S Day, Department of Paediatrics, University of Otago Christchurch, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Funding

This work was supported by Canterbury Medical Research Foundation Grant No. 002.

Conflicts of Interest

None disclosed.

References

- 1. Lemberg DA, Day AS.. Crohn’s disease and colitis in children: an update for 2014. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51:266–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carroll MW, Keunzig ME, Mack DR, et al. The impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada 2018: children and adolescents with IBD. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2019; 2:49–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi FE, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017:2769–2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kleinman R, Baldassano RN, Caplan A, et al. Nutrition support for pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a clinical report of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sawczenko A, Sandhu BK.. Presenting features of inflammatory bowel disease in Great Britain and Ireland. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:995–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diederen K, Krom H, Koole JC, et al. Diet and anthropometrics of children with inflammatory bowel disease: a comparison with the general population. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1632–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Griffiths AM. Specificities of inflammatory bowel disease in childhood. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:509–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heuschkel R, Salvestrini C, Beattie RM, et al. Guidelines for the management of growth failure in childhood inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:839–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Forbes A, Escher J, Hébuterne X, et al. ESPEN guideline: clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:321–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. James A, Kjørholt AT, Tingstad V.. Introduction. In: Children, Food and Identity in Everyday Life. Palgrave Macmillan; 2009:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pituch-Zdanowska A, Kowalska-Duplaga K, Jarocka-Cyrta E, et al. Dietary beliefs and behaviors among parents of children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Med Food. 2019;8:817–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reed-Knight B, Mackner LM, Crandall WV, et al. Psychological aspects of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. In: Mamula P, Grossman A, Baldassano R, Kelsen J, Markowitz J, eds. Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Springer; 2017:615–623. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Keethy D, Mrakotsky C, Szigethy E.. Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease and depression: treatment implications. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2014;26:561–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seiffge-Krenke I. Adolescent, parental, and family coping with stressors. In: Seiffge-Krenke I, ed. Diabetic Adolescents and Their Families: Stress, Coping, and Adaptation. Cambridge University Press; 2001:85–117. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nielsen S. Eating disorders in females with type 1 diabetes: an update of a meta-analysis. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2002;10:241–254. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rodin G, Olmsted MP, Rydall AC, et al. Eating disorders in young women with type 1 diabetes. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:943–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Herpertz S, Wagener R, Albus C, et al. Diabetes mellitus and eating disorders: a multicentre study on the comorbidity of the 2 diseases. J Psychosom Res. 1998; 44:503–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gerasimidis K, Keane O, Macleod I, et al. A four-stage evaluation of the Paediatric York- hill Malnutrition Score in a tertiary paediatric hospital and a district general hospital. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:751–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McCarthy HMH, Dixon M, Eaton-Evans MJ.. Nutrition screening in children - the validation of a new tool. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2008;21:395–396. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hulst JM, Zwart H, Hop WC, et al. Dutch national survey to test the STRONGkids nutritional risk screening tool in hospitalized children. Clin Nutr. 2010;29:106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sermet-Gaudelus I, Poisson-Salomon AS, Colomb V, et al. Simple pediatric nutritional risk score to identify children at risk of malnutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morrow AM, Quine S, Heaton MD, et al. Assessing quality of life in paediatric clinical practice. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010;46:323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sintonen H. The 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: properties and applications. Ann Med. 2001;33:328–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Apajasalo M, Sintonen H, Holmberg C, et al. Quality of life in early adolescence: a sixteen-dimensional health-related measure (16D). Qual Life Res. 1996;5:205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Otley A, Smith C, Nicholas D, et al. The IMPACT questionnaire: a valid measure of health-related quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35:557–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hughes LD, King L, Morgan M, et al. Food-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: development and validation of a questionnaire. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2016;10(2):194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Czuber-Dochan W, Morgan M, Hughes LD, et al. Perceptions and psychosocial impact of food, nutrition, eating and drinking in people with inflammatory bowel disease: a qualitative investigation of food-related quality of life. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2020;33:115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Whelan K, Murrells T, Morgan M, et al. Food-related quality of life is impaired in inflammatory bowel disease and associated with reduced intake of key nutrients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113:832–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Day AS, Yao CY, Costello S, et al. Food-related quality of life in adults with inflammatory bowel disease is associated with restrictive eating behaviour, disease activity and surgery: a prospective multicentre observational study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2022;35:234–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, et al. ECCO-ESGAR guideline for diagnostic assessment in IBD part 1: initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:144–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. World Health Organization. BMI growth reference range 5-19. 2018. Accessed July 1, 2020.http://www.who.int/growthref/who2007_bmi_for_age/en. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bartholomeusz FD, Shearman DJ.. Measurement of activity in Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1989;4:81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hyams JS, Ferry GD, Mandel FS, et al. Development and validation of a pediatric Crohn’s disease activity index. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991;12:439–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bland JM, Altman DG.. Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ. 1997;314:572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bengtsson M. How to plan and perform qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open. 2016;2:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hartman C, Marderfeld L, Davidson K, et al. Food intake adequacy in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63:437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rathner G, Zangerle M.. Coping strategien bei Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Diabetes mellitus Die deutschsprachige Version des KIDCOPE. Z Klin Psychol Psychiatr Psychother. 1996;44:49–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Saxena MK, Aggarwal S.. Developing emotional intelligence in children - role of parents. Int J Educ Allied Sci. 2010;2:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Prince A, Whelan K, Moosa A, et al. Nutritional problems in inflammatory bowel disease: the patient perspective. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:443–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jamieson AE, Fletcher PC, Schneider MA.. Seeking control through the determination of diet: a qualitative investigation of women with irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nurse Spec. 2007;21:152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Daniel JM. Young adults’ perceptions of living with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2002;25:83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cohen RD. The quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1603–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Engstrom I, Lindquist BL.. Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: a somatic and psychiatric investigation. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991; 80: 640–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rabbett H, Elbadri A, Thwaites R, et al. Quality of life in children with Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996;23:528–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Moody G, Eaden JA, Mayberry JF.. Social implications of childhood Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:S43–S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]