Abstract

The Lazarus effect is a rare condition that happens when someone seemingly dead shows signs of life. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) represents a target in the fatal neoplasm glioblastoma (GBM) that through a series of negative clinical trials has prompted a vocal subset of the neuro-oncology community to declare this target dead. However, an argument can be made that the core tenets of precision oncology were overlooked in the initial clinical enthusiasm over EGFR as a therapeutic target in GBM. Namely, the wrong drugs were tested on the wrong patients at the wrong time. Furthermore, new insights into the biology of EGFR in GBM vis-à-vis other EGFR-driven neoplasms, such as non-small cell lung cancer, and development of novel GBM-specific EGFR therapeutics resurrects this target for future studies. Here, we will examine the distinct EGFR biology in GBM, how it exacerbates the challenge of treating a CNS neoplasm, how these unique challenges have influenced past and present EGFR-targeted therapeutic design and clinical trials, and what adjustments are needed to therapeutically exploit EGFR in this devastating disease.

Keywords: Biological therapy, glioblastoma, molecular heterogeneity, precision oncology, tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Gliomas are the most common malignant primary brain tumors in adults and comprise a diverse group of diseases. Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most aggressive glioma and has median survival of less than 15 months from initial diagnosis.1 Current standard-of-care therapy consists of maximal safe surgical resection, fractionated radiation therapy (XRT), and concurrent and adjuvant temozolomide (TMZ).1 However, recurrence is inevitable as these tumors diffusely invade the normal brain. While GBM has historically been diagnosed by histological criteria alone, the current World Health Organization (WHO) 2021 Classification of Central Nervous System (CNS) Tumors requires integrated histological and molecular diagnoses.2,3 GBM is now defined exclusively as a high grade (CNS WHO grade 4) glioma harboring wild-type isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1 and IDH2) genes. Despite this uniform molecular classification, large scale multi-omic studies such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA) have revealed extensive inter- and intra-tumor heterogeneity.4–7

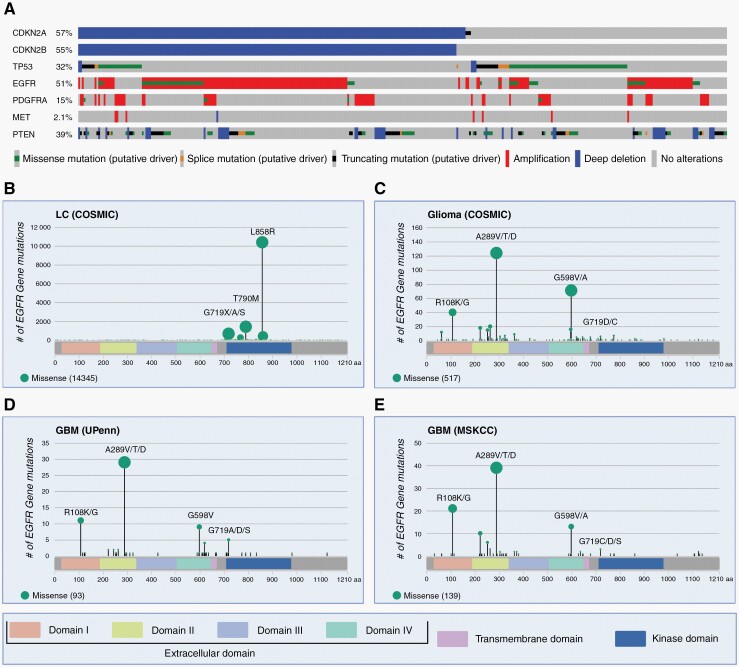

Heterogeneity between tumors, within the same tumor, and temporally contribute to the challenges of treating GBM with precision oncology-based approaches. Early studies such as TCGA revealed significant inter-tumoral heterogeneity among different patients by sequencing random tumor samples (Figure 1A). These studies identified core pathways involved in driving the disease, quantified mutational frequencies and co-occurrence patterns, and classified tumors based on transcriptional profiles into three reproducible subtypes: proneural, classical, and mesenchymal.4,8 Subsequent studies profiled multiple samples from the same tumor or used single cell sequencing to reveal significant intra-tumoral heterogeneity, illustrating that a single tumor can have multiple transcriptional profiles that correlate with the anatomical region of the sampled tumor or plasticity associated with transitional cellular states.5,6,9–12 Temporal heterogeneity has also been observed, as Barthel et al.13 identified significant changes in driver mutations between paired primary and recurrent GBM tumors. Thus, previous precision approaches based on one or two targets failed to take into account the vastly different cell populations that can be present within and between tumors. Further characterization of the mechanisms responsible for this considerable molecular heterogeneity will be critical for developing novel therapeutic approaches and combatting drug resistance.14

Fig. 1.

Molecular profile of GBM and GBM-specific EGFR variants. (A) Oncoprint from cBioPortal showing mutational frequencies of CDKN2A, CDKN2B, TP53, EGFR, PDGFRA, MET, and PTEN from the GBM Pan Cancer Atlas cohort (n = 378). Altered samples only with mutants of known significance are shown.15–17 (B) Lollipop plots of EGFR missense mutations made in R version 4.2.0 with package “g3viz” version 1.1.4.18 The extracellular domains (ECD), transmembrane domain, and the intracellular kinase domain (KD) of EGFR are shown. EGFR missense mutations in lung carcinoma (LC) from COSMIC are concentrated in the KD.19 The top three mutant amino acid (AA) sites are shown: L858R (72.4%), T790M (9.9%), and G719X/A/S (4.8%) with a total n = 14,345. AA sites with multiple AA changes are listed in descending order of frequencies. Interestingly, mutations in the G719 site are also seen in GBM, albeit in lower frequencies. (C) EGFR missense mutations in gliomas from COSMIC concentrate in the ECD.19 Common mutant sites in the ECD include: A289V/T/D (23.9%), G598V/A (13.7%), and R108K/G (7.7%) with a total n = 517. In the KD, G719D/C (1.2%) mutants are observed. (D) EGFR mis-sense mutations in glioblastoma (GBM) from an updated (2020) UPenn institutional cohort study.20 Common mutant sites in the ECD include: A289V/T/D (31.2%), R108K/G (11.8%), and G598V (9.7%) with a total n = 93. In the KD, G719A/D/S (5.4%) mutants are observed. (E) EGFR mis-sense mutations in GBM from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in cBioPortal.15,16,21 Common mutant sites in the ECD include: A289V/T/D (28.1%), R108K/G (15.1%), and G598V/A (9.4%) with a total n = 139. In the KD, G719C/D/S (2.2%) mutants are observed.

Receptor Tyrosine Kinases in GBM

Many of the mutated genes in GBM function in three core intracellular signaling pathways that govern multiple cancer hallmarks: the G1-S cell cycle checkpoint, the TP53 pathway, and receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling via downstream mitogen activated protein (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3K) kinases.4,22 Genetic alterations in RTK oncogenes, including EGFR, PDGFRA, and MET, are common in GBM and thus represent promising therapeutic targets (Figure 1A).23 Over 63% of GBM in the TCGA PanCancer atlas cohort (n = 378) have amplification or gain of function mutations in at least one of these RTK.4,15–17 The majority (86%) harbored alterations in a single RTK.15–17 However, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies have shown that the remaining tumors can harbor mosaic amplification of multiple RTK alterations, with EGFR and PDGFRA amplifications found in tumor cells from spatially distinct regions.23 Mosaic amplification of EGFR and MET was noted in spatially co-mingled tumor cells, while rare tumor cells harbored 2 or more of these amplified RTK oncogenes.24 Spatial distribution analysis of RTK subclones in a single patient tumor showed that EGFR and PDGFRA amplifications were localized to the main tumor core, while only EGFR amplification was detected in the infiltrating tumor edge.

EGFR Precision Oncology in Other Neoplasms as a Model for GBM Therapy

Precision oncology seeks to give the right drug to the right patient at the right time. Functionally, this involves matching driver oncogenes with targeted inhibitors. This strategy has had notable success in a variety of mutated kinase-driven neoplasms, including BCR/ABL-driven CML with imatinib and EGFR- or ALK-driven lung cancers with gefitinib/erlotinib or crizotinib, respectively.25,26 Success in EGFR-mutant lung cancer and the prevalence of oncogenic EGFR alterations in GBM spurred clinical trials in the mid-2000s with EGFR TKIs repurposed from non-CNS neoplasms.27–31 These trials failed to improve overall survival outcomes in GBM patients. However, a newfound understanding of EGFR biology in GBM has emerged over the past 15 years that highlights issues with early clinical trials that run contrary to the principal tenets of precision oncology. Some of these issues include poor blood brain barrier (BBB) penetrance of the drugs examined, lack of patient stratification based on EGFR mutation status, and studies that were performed primarily in the recurrent disease setting. These issues, together with novel insights into EGFR biology in GBM vis-à-vis other EGFR-driven solid neoplasms (e.g., NSCLC) and the over 50% prevalence of EGFR mutations in GBM, suggest that it should not be relegated to the dust heap of molecular drug targets.17,32

The success of personalized oncology for EGFR-driven solid malignancies outside the CNS and its failure to date for GBM collectively highlight the importance of understanding the unique biology of EGFR in specific clinical contexts. EGFR-driven NSCLC is particularly instructive, as it exemplifies oncogene addiction from a biological perspective and personalized oncology from a clinical perspective. Tyrosine kinase (TK) domain mutations such as L858R in the active, ATP binding site of the receptor have been shown to drive tumorigenesis in inducible, genetically engineered mouse models of NSCLC. In these models, tumors regress upon signal termination and regrow upon its reconstitution.33 Clinically, molecular testing for EGFR mutations has always been a prerequisite for targeted drug therapy with gefitinib, erlotinib, afatinib, and more recently, osimertinib. NSCLC harboring classical TK domain mutations, specifically deletions in exon 19 or the exon 21 L858R missense mutation, were originally treated with first (gefitinib and erlotinib) and second (afatinib) generation TKI. However, intrinsic and acquired resistance to these drugs is common via a genetic mechanism: tumor cells harboring or acquiring the TK domain gatekeeper mutation T790M drive tumor progression via restored oncogenic EGFR signaling.34 Third-generation TKI were specifically designed to target these EGFRT790M driven tumors and one, osimertinib, is now clinically indicated to overcome this genetic resistance mechanism.35

A subsequent crystal structure-function study has shown that EGFR mutations in NSCLC can be divided into four groups based on their impact on the drug binding pocket: classical-like, T790M-like, exon 20 loop insertion (Ex20ins-L), and P-Loop αC-helix compressing (PACC).36 This grouping is more predictive of drug sensitivity and patient outcomes than exon-based categorization. The classical-like variants (e.g., L858R and exon 19 deletions) induce alterations distal to the drug binding pocket and respond well to 1st, 2nd, and 3rd generation TKI. T790M-like variants typically co-occur with other TK domain mutations in the hydrophobic core of the drug binding pocket, yielding structures with increased ATP affinity compared to classical-like mutations. Two T790M-like subgroups were evident based on their differing sensitivity to 3rd generation TKI. Ex20ins-L variants altered the C-terminal loop of the αC-helix, had substantial impact on drug binding, and could be divided into two subgroups based on location and sensitivity to 2nd generation TKI. PACC mutations (e.g., G719X) displaced the P-loop and/or αC-helix, impacted drug binding, and rendered cells sensitive to 2nd gen TKI.36

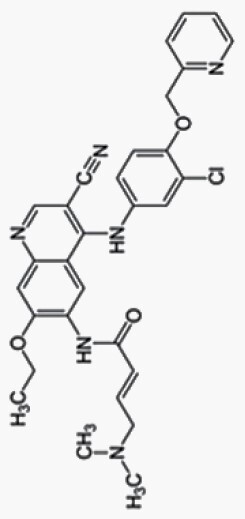

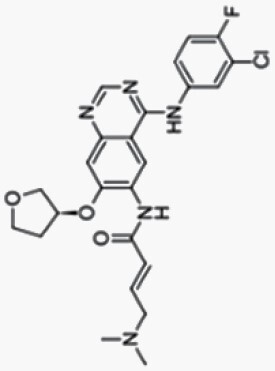

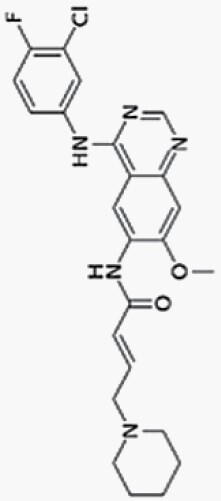

Precision oncology for GBM has failed not only for lack of molecular stratification in clinical trials, but due to fundamental differences in its EGFR biology relative to other EGFR-driven neoplasms. Decades of work has shown that EGFR-mutant GBM (e.g., EGFRvIII) rely on sustained signaling to drive tumor initiation and maintenance (proliferation, growth, survival, and metabolism).37,38 We and others have found that the mutational distribution in EGFR in GBM is distinct from NSCLC.32,39 NSCLC harbor TK domain mutations (Figure 1B) and their molecular detection by random biopsy sampling is sufficient to establish the diagnosis of EGFR-mutant NSCLC and guide therapy with TKI. In contrast, multiple different oncogenic EGFR variants, both deletions and mis-sense mutations, typically co-exist with EGFR amplification in GBM.32 These mutations are almost always localized to the extracellular domain (ECD) (Figure 1C–E) and are not homogenously distributed: results of biopsy-based molecular detection can change based upon regional sampling.11 Moreover, key biological experiments required to demonstrate oncogene addiction have yet to be performed for GBM EGFR missense mutations, and no gatekeeper EGFR mutations (e.g., T790M) have been described.38,40,41 While a detailed structure-function study was recently published, it focused on ligand biases and downstream signaling rather than drug sensitivity.42 Taken together, these findings suggest alternative mechanisms may be involved in EGFR TKI response in GBM vs NSCLC.

Heterogeneity of EGFR–Ligand Interactions

EGFR is initially translated as a 1210 amino acid immature polypeptide that is cleaved at the N-terminus to form its mature 1186 amino acid transmembrane receptor. EGFR can be activated by a variety of ligands which induce either homo- or hetero-dimerization with other ERB-B family tyrosine kinases, including ErbB2 (HER2), ErbB3, and ErbB4.43 Binding of high- and low-affinity ligands produces distinct wild-type (EGFR) dimerization structures and preferentially activates distinct downstream effector pathways, including MAPK, PI3K, and STAT3, by auto-phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in its cytoplasmic domain (Figure 2A). EGF, a high-affinity ligand, induces stable receptor dimerization, while the low-affinity ligands epiregulin (EREG) and epigen (EPGN) induce unstable dimers. Despite their unstable structures, weak ligands induce more sustained receptor auto-phosphorylation at tyrosine sites Y845, Y1086, and Y1173 compared to EGF.44 Moreover, differential activation of the three downstream signaling pathways is ligand dependent.45,46 Future studies are required to elucidate how ligand-induced structural interactions are linked with differential effector pathway signaling and drug sensitivity.

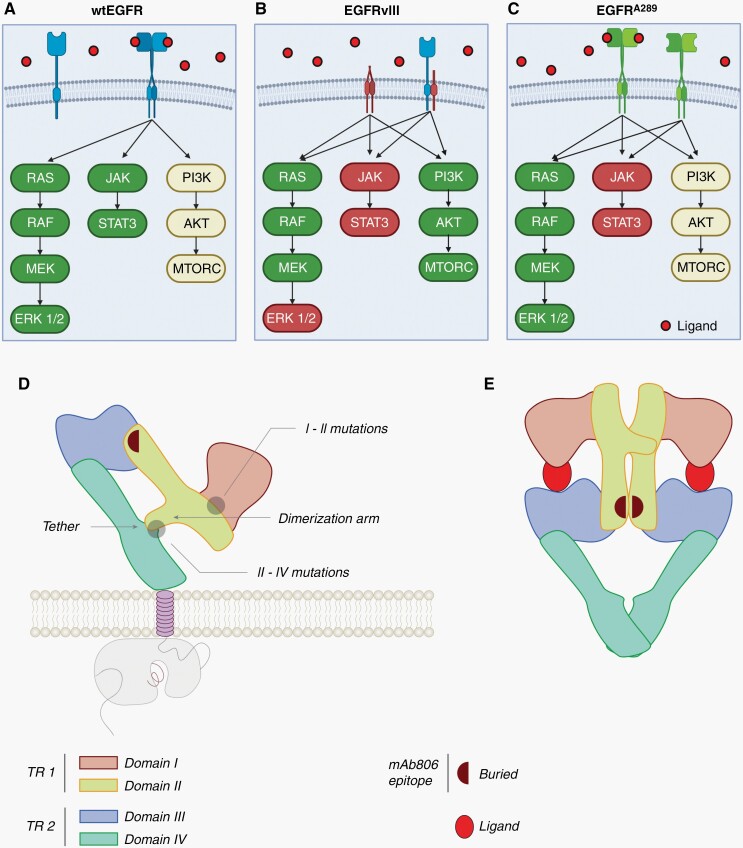

Fig. 2.

EGFR variant specific downstream signaling and structural convergence. (A) wtEGFR is activated upon ligand binding by receptor homo- or hetero-dimerization. Once activated, wtEGFR strongly signals via the MAPK and STAT3 pathways and intermediately signals via the PI3K pathway.47 (B) EGFRvIII has a truncated extracellular domain (ECD) and is unable to bind ligands. However, EGFRvIII can initiate downstream signaling via homo-dimerization or hetero-dimerization with wtEGFR. EGFRvIII signals strongly via the PI3K pathway and weakly via the STAT3 pathway. Interestingly, EGFRvIII strongly activates early MAPK signaling components but this is not translated to ERK signaling.47 (C) EGFRA289 activation and dimerization can be induced by ligand binding, but this mutant also has constitutive, ligand independent signaling. EGFRA289 has strong signaling through the MAPK pathway, intermediate signaling through the PI3K pathway, and weak signaling through the STAT3 pathway. Figure adapted from Huang et al. and Binder et al.20,47 Reprinted with permission from AAAS. (D) EGFR has 4 ECDs (domains I–IV) arranged as two tandem repeats (TR1 and TR2). Domains II and IV interact to form a tether when EGFR is in the inactive conformation.48 (E) Binding of a ligand, like EGF, induces receptor dimerization to the active conformation and removal of the domains II–IV tether. In both the inactive (D) and active (E) states, the cryptic epitope is hidden and unable to be recognized by mAb 806. Adapted and modified from Orellana et al.48 Reprinted with permission from PNAS.

Inter-tumor EGFR Heterogeneity

Large scale sequencing studies in GBM have found that the most commonly mutated form of the receptor, amplification of wtEGFR, generally co-occurs with in-frame deletion or mis-sense mutations in the ECD. EGFRvIII and EGFRvII harbor deletions of exon 2–7 and exon 14–15 and occur in approximately 25% and 15% of gliomas, respectively.19,32 Common missense mutations include EGFRR108G/K, EGFRA289V/T/D, and EGFRG598V and occur in 2.2%, 5.9% and 1.8% of all IDH wild-type GBM cases, respectively, in an updated institutional cohort from the University of Pennsylvania.20 Mutations in EGFR have consequences for ligand binding affinity and downstream signaling that are linked via structural differences in receptor dimerization.42 Studies focused on these receptor variants have begun to elucidate signaling pathway preferences and some are associated with distinct clinical phenotypes.20

EGFR Extracellular Domain (ECD) Deletion Variants

EGFRvIII is the most common deletion variant in GBM: exon 2–7 deletion removes 267 amino acids (AA) from the ECD, results in a novel glycine residue at the junction of exons 1 and 8, and exposes a cryptic neo-epitope recognizable by monoclonal antibodies.48–50 While unable to bind its typical ligands, the altered ECD of EGFRvIII results in low level constitutive activation of downstream signaling comparable to ~ 10% of ligand activated wtEGFR.47 EGFRvIII is hypo-phosphorylated at Y1045 relative to wtEGFR, precluding internalization and subsequent ubiquitin mediated degradation. Phosphorylation studies of the cytoplasmic domains of EGFRvIII and wtEGFR showed quantitative differences in downstream signaling specificity, a likely explanation for preferential PI3K signaling by EGFRvIII compared to MAPK and STAT3 for wtEGFR (Figure 2B).47

EGFRvII is the second most common deletion variant in GBM: an exon 14–15 deletion removes 83 AA from the ECD.48 It was initially identified three decades ago but has only recently been shown to have oncogenic effects.51,52 Phosphorylation studies showed that it is constitutively active without ligand induction and preferentially triggers downstream PI3K signaling via AKT phosphorylation.52 EGFRvII driven tumors developed slower in vivo and exhibited oligodendroglial histology compared to EGFRvIII driven tumors, suggesting that EGFR ECD deletion variants impact clinically-relevant phenotypic tumor characteristics.52

EGFR ECD Mis-sense Mutants

Mis-sense mutations in the EGFR ECD are less common than deletion variants. Together, they constitute ~10% of gliomas in the TCGA PanCancer cohort.15–17 In a multi-institutional cohort study of GBM patients, Binder et al.20 found the mis-sense mutants EGFRA289V/T/D, EGFRR108G/K, and EGFRG598V in 6%, 3%, and 2% patients, respectively, and confirmed that these mis-sense mutations commonly co-occur with wtEGFR amplification. Patients with EGFRA289V/T/D have a significantly lower median overall survival (OS) compared to patients with alanine at EGFR289 site. Advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows features that may be indicative of increased proliferation and invasion in EGFRA289V/T/D mutant patients, again when compared to patients with alanine at EGFR289. EGFRA289V is constitutively active and signals through an ERK/MMP1 axis to promote cellular proliferation and invasion (Figure 2C). In contrast, EGFRR108G/K and EGFRG598V do not show significant differences in OS. EGFRR108G/K is, however, associated with MGMT methylation status, a known predictive marker of TMZ response and a potentially confounding variable for determining association with OS.20

Hu et al. performed structure-function studies on wtEGFR and two common, GBM-associated ECD mutants (EGFRR108K and EGFRA289V) and found that the latter fail to discriminate between typical EGFR-activating ligands. In wtEGFR, strong ligands induce symmetrical homo-dimerization and transient signaling to promote proliferation, while weak ligands induce asymmetrical homo-dimerization and sustained signaling to promote cellular differentiation. EGFRR108K and EGFRA289V mutations lose their ability to distinguish between strong or weak ligands via distinct structural alterations. While EGFRR108K increased EREG affinity by “symmetrizing” the dimer, EGFRA289V strengthened asymmetrical dimerization.42 These studies highlight the fact that deletion and missense alterations in the EGFR ECD have distinct structure–function relationships as well as biology. Interestingly, despite their differences, some variants structurally converge to expose a common epitope.

Structural Convergence of EGFR Variants

The EGFR monomer has four ECDs (domains I–IV) arranged as two tandem repeats (TR1 and TR2) and interact with three inter-domain interfaces: I–II, II–IV and, II–III (Figure 2D). The domain II–IV interaction forms a self-inhibitory tether in the ECD when EGFR is in the inactive monomer state (Figure 2D). Upon activation, the ECD of EGFR dimerizes to become an untethered, ligand-bound, active receptor (Figure 2E). During the transition from the inactive to active conformation of EGFR, rotation of the N-terminal residues (6–273) of the TR1 (N-TR1) fragment exposes a cryptic epitope consisting of a short cysteine loop (AA 287-302) that is recognized by monoclonal antibody (mAb) 806. Deletion variants, EGFRvII and EGFRvIII, and assorted EGFR missense variants, EGFRG63R, EGFRR108K, EGFRA289V, and EGFRG598V structurally converge to constitutively expose this cryptic epitope by removing steric hinderance in the N-TR1 fragment. EGFRvII, EGFRvIII and the four aforementioned EGFR missense variants either delete the II-IV inter-domain tether, delete the N-TR1 fragment, or increase TR1 flexibility and untethering, respectively. Structurally, the N-TR1 fragment (absent in EGFRvIII) in these mutants is unable to maintain EGFR as a tethered monomer in the inactive state, thus constitutively exposing the 806 epitope. Interestingly, amplified expression of wtEGFR results in presentation on the cell membrane of an immature, high-mannose form of the receptor that, like EGFRvIII, is untethered and recognized by mAb 806.53

Taken together, it can be inferred that EGFR variants recognized by mAb 806 are oncogenic. Structural convergence of these oncogenic EGFR variants via constitutive exposure of the cryptic 806 epitope may provide an avenue for therapeutic exploitation. These limited studies have provided some insight into the differences and similarities of GBM-specific EGFR variants in terms of structure and function. However, our understanding of these variants, particularly in terms of drug sensitivity, pale in comparison to our understanding of variants specific to other diseases, particularly NSCLC. Future studies focused on elucidating the linkage among genetic sequence, structure, function, and drug response are imperative for designing effective targeted inhibitors specifically for GBM indications.

Intra-tumor EGFR Heterogeneity

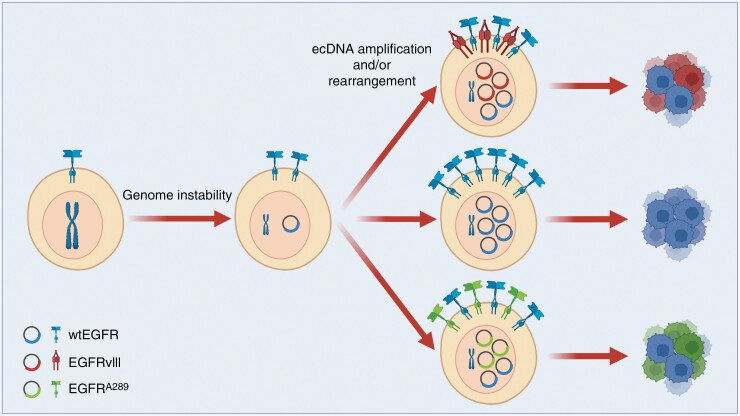

Genome instability is an early event in GBM tumorigenesis and is likely induced via frequent genetic alterations in CDKN2A and/or TP53 (80% of GBM in TCGA Pan-Cancer Atlas).15–17,24 In contrast, mathematical modeling suggests that EGFR amplification and/or mutations are late events.54 Over 74% of GBM in the TCGA PanCancer cohort harbored concurrent CDKN2A loss-of-function mutations and EGFR amplification and/or mutations and this pattern of co-occurrence was statistically significant.4,15,16,55 Genome instability-induced amplification generates significant intra-tumoral EGFR heterogeneity and has been linked clinically and experimentally to improved tumor cell fitness.56,57

Extra-chromosomal DNA (ecDNA) amplifications refers to copy number gains of DNA fragments that are not contiguous with the twenty-three canonical chromosomes. These small, acentric, circular DNA molecules, derived as a consequence of genome instability, are capable of autonomous replication and are largely responsible for intra-tumoral heterogeneity due to their unequal segregation during cell division.58 ecDNA serves as a common source of oncogene amplification in many cancers, such as MYCN in neuroblastoma, DHFR in colon cancer, and EGFR in GBM.59 In addition to serving as a source of amplified oncogenes, ecDNA can also serve as mobile enhancers via ultra-long-range chromatin interactions.60 Understanding how ecDNA generates intra-tumoral EGFR heterogeneity will be important for developing effective EGFR-targeted therapeutics and for understanding clonal evolution.

Genome instability can lead to chromothripsis, an event that causes massive focal chromosomal rearrangements and/or amplifications that can drive generation of ecDNA (Figure 3).61 Indeed, EGFR amplification via ecDNA is likely initiated as a single event where genomic regions overlapping the EGFR gene are joined via non-homologous end joining and are subsequently clonally amplified.62 From single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis, EGFRvIII appears to derive from amplified full-length EGFR and is associated with chromosome 7 rearrangements.57 While all EGFRvIII variants feature the same genomic deletion of exons 2–7, multiple different break points within introns 1 and 7 can generate this deletion.57 EGFRvIII breakpoint variants can be created by different DNA repair mechanisms, including non-homologous end joining, fork stalling and template switching, microhomology-mediated break-induced repair, and microhomology-mediated end joining. These DNA repair mechanisms can form a breakpoint junction between upstream and downstream segments with or without microhomology.57

Fig. 3.

ecDNA generation and contribution to intra-tumoral heterogeneity. Genome instability can lead to EGFR oncogene amplification via generation of extra-chromosomal DNA (ecDNA). Further amplifications and genome rearrangements of EGFR-containing ecDNA leads to intra-tumoral EGFR heterogeneity.61,63

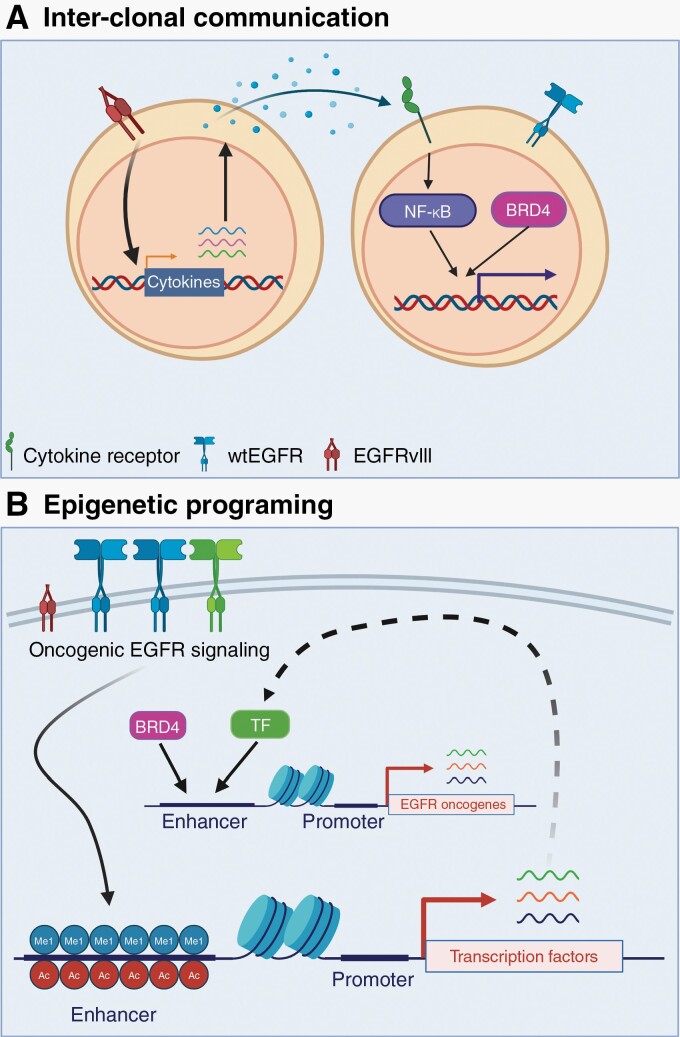

EGFRvIII expression on ecDNA can be dynamic over the life span of the tumor. Indeed, Van den Bent et al.64 found that patients with matched recurrent versus primary GBM lost EGFRvIII expression during the course of standard therapy while retaining wtEGFR amplification. This extensive EGFR heterogeneity in GBM helps contribute to tumoral fitness through inter-clonal cross-talk.56 Despite its known pro-tumorigenic properties, EGFRvIII-expressing cells generally constitute a minority of tumor cells, with most expressing amplified wtEGFR. In vivo studies with established cell lines show that a mixed population of cells harboring amplified wtEGFR intermingled with EGFRvIII-expressing cells generated significantly larger tumors compared to pure populations.56 Cross-talk between the two cell populations, initiated by EGFRvIII-positive cells via the cytokine IL-6, leads to wtEGFR activation in a ligand independent manner (Figure 4A).56 Further studies into this cross-talk showed that IL-6 drives NF-κB signaling leading to induced expression of pro-survival genes via an epigenetic mechanism mediated by bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4).65 These pro-survival genes not only enhance proliferation and migration, but confer resistance to EGFR TKI, indicating that cross-talk between EGFR variant-expressing subclones must be considered in EGFR precision oncology approaches.66

Fig. 4.

EGFR contributions to tumoral fitness. (A) EGFRvIII signaling induces expression of the cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6). Through paracrine signaling, IL-6 induces NF-κB signaling in wtEGFR-expressing cells. NF-κB cooperates with bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) to induce expression of pro-survival genes such as survivin (BIRC5). (B) We propose that oncogenic EGFR variants induce a malignant epigenetic program. For example, Liu et al. found that EGFRvIII signaling deposits H3K4me1 and H3K27ac at enhancers. Importantly, this drives expression of transcription factors (TF) that cooperate with BRD4 to activate expression of EGFR-associated oncogenes.67 Further studies are needed to determine if other oncogenic EGFR variants can induce similar epigenomic alterations.

Interestingly, clonal oncogenic variants of EGFR are also capable of driving epigenetic programing without cross-talk (Figure 4B). Indeed, in U87 cells, EGFRvIII over-expression drives deposition of activating H3K4me1 and H3K27ac marks in over 2000 enhancers, of which 40 are associated with transcription factors (TF) such as SOX9 and FOXG1.67 Gene ontology (GO) analysis showed that SOX9- and FOXG1-activated EGFR-regulated genes and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) showed enrichment in MYC (c-Myc) pathway genes. These studies suggest that oncogenic EGFRvIII expression induces programming of a malignant epigenetic state that promotes tumor cell growth.67 These novel insights into EGFR heterogeneity within a single tumor and cross-talk between co-occurring variants serve as an investigational roadmap for other less studied GBM-specific EGFR variants.

EGFR-Targeted Therapeutics

The prevalence of EGFR alterations and the dependence on EGFR signaling for gliomagenesis make EGFR an attractive target for GBM precision oncology. Indeed, since the mid-2000s, there have been multiple clinical trials focused on EGFR using both pharmacological and biological approaches. The first clinical trials targeting EGFR in GBM utilized EGFR TKI that had been repurposed largely from EGFR-driven NSCLC. Clinical trials with biological inhibitors, including antibodies, peptide vaccines, and chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR T) cells, have followed. Unfortunately, these clinical trials have yet to yield significant improvements in patient outcomes.68,69 They have, however, provided key lessons about the unique biology of EGFR in GBM that should influence design of improved targeted therapeutic approaches in the future. Clinical trials and their implications for the future of EGFR-targeting in GBM are discussed further below.

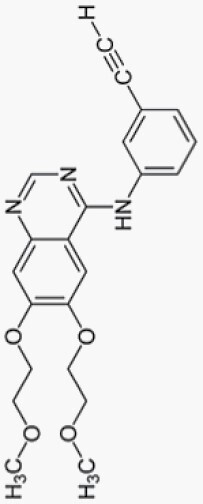

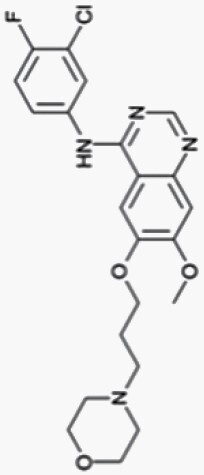

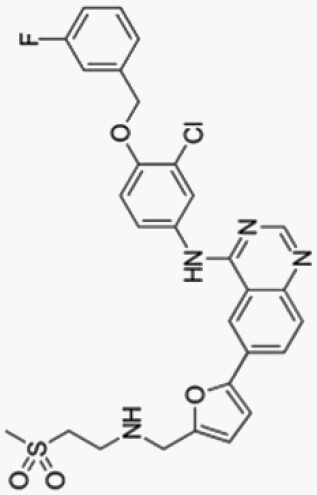

EGFR TKI

One key distinction that may explain the lack of response of current EGFR TKI in GBM is the differing oncogenic variants of EGFR found in GBM compared to those found in NSCLC. As discussed, in NSCLC, mutations in the EGFR coding sequence are concentrated in the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) (Figure 1B).70 Conversely, in GBM, EGFR mutations are primarily localized to the ECD and include in-frame deletions and/or missense mutations (Figure 1C–E).71 Moreover, a considerable number of GBM display amplification of wtEGFR with no other activating mutations present.32 Intriguingly, despite the oncogenic dependencies that these distinct EGFR alterations confer to GBM cells, GBM-specific EGFR alterations display differential sensitivity to EGFR TKIs originally developed for TKD domain EGFR-mutant NSCLC (Table 1).39,72,73 For example, Type I EGFR TKIs, which include gefitinib and erlotinib, show affinity for activated wtEGFR as well as TKD mutants.39 Conversely, Type II TKIs, which include lapatinib and neratinib, display higher affinity for ECD mutant than activated wtEGFR.39 Given the co-occurrence of both amplified wtEGFR and ECD mutants, these findings suggest that a TKI that inhibits both wtEGFR and ECD mutant signaling would be required for successful therapy of EGFR-driven GBM.

Table 1.

Pharmacology of Selected EGFR TKI

| Drug | Clinical dose | Steady state concentration ng/ml | nM at steady state | % Plasma protein binding | IC50 | Molecular weight | Unbound plasma nM | Kp, brain | kpuu, brain | Predicted unbound brain nM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erlotinib | 150 mg | 120074 | 3050 | 9575 | 91 nM (LoVo)76 2 nM (Cell-Free)77 |

0.39 | 153 | 14 (rat)78 | 0.05 (mouse)79 0.084 (rat)78 |

12.8 |

| Gefitinib | 500 mg | 15380 | 342 | 9781 | 22 nM (NR6wtEGFR)82 21 nM (NR6W)82 27-33 nM (Cell-Free)77 3 nM (Millipore Assay) |

0.45 | 10 | 12 (rat)78 | 0.02 (mouse)83 0.0092 (rat)78 |

0.205 |

| Lapatinib | 750 mg bid | 243039 | 4182 | 9984 | 11 nM (Cell-Free Assay)77 | 0.58 | 42 | 0.03 (mouse)85,86 | 0.04 (mouse)79 | 1.67 |

| Neratinib | 240 mg | 81.587 | 146 | 99a | 92 nM (Cell-Free)77 | 0.56 | 1.5 | 0.079b (mouse) | ||

| Afatinib | 40 mg | 42.788 | 88 | 9589 | 15 nM (LoVo)76 0.2-0.7 nM (Cell-Free)77 3 nM (Millipore Assay) |

0.49 | 4.4 | 0.2 (rat)78 | 0.006 (rat)78 | 0.0272 |

| Dacomitinib | 45 mg | 58.590 | 120 | 98c | 12 nM (LoVo)76 6 nM (Cell-Free)77,91 |

0.47 | 2.4 | 0.76d (rat)78 | 0.030c (rat)78 0.493 (mouse)183 |

0.959 |

| Osimertinib | 80 mg | 317.5 | 63592 | 95e | 480 nM (LoVo)76 184 nM (Millipore Assay) Kp, brain: 6.09(rat)78 |

0.50 | 32 | 6.09(rat)78 | • 0.21 (rat)78 • 0.39 (mouse)83 |

12.4 |

Steady state concentration is calculated by taking steady state concentration (ng/mL) divided by molecular weight (g). Unbound plasma concentration is calculated by multiplying the ratio of free drug in plasma (100—% plasma protein binding) with the steady state trough concentration (ng/mL). Predicted unbound brain concentration is calculated by multiplying the unbound plasma concentration by the unbound brain-to-plasma ratio (Kpuu).

Abbreviations: bid, twice daily.

aProduct Information: NERLYNX(TM) oral tablets, neratinib oral tablets. Puma Biotechnology, Inc (per FDA), Los Angeles, CA, 2017.

cProduct Information: VIZIMPRO(R) oral tablets, dacomitinib oral tablets. Pfizer Labs (per FDA), New York, NY, 2018.

dTime points taken to 7 h, see referenced study for full details.

eProduct Information: TAGRISSO(R) oral tablets, osimertinib oral tablets. AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP (per FDA), Wilmington, DE, 2017.

For individual EGFR TKI, drug affinity for specific EGFR variants may be associated with structural changes in the EGFR ECD. Crystal structures of the ligand binding domains of EGFR bound to relevant ligands show that EGFR can adopt different receptor conformations dependent on the activation/inactivation state of the receptor and the strength of ligand binding.42,93 Oncogenic alterations destabilize alternative structural conformations and may help coerce the receptor to adopt a specific conformational state revealing the cryptic 806 epitope.42,48,94 This forced structural change of EGFR in various TKD mutants affects the ability of EGFR TKI to displace ATP from the TKD binding site, modulating their sensitivity to different EGFR TKI.39,94 This finding is consistent with a separate study suggesting kinase site occupancy and the rate of dissociation of EGFR TKI underlies differential sensitivity between EGFR-driven lung and brain cancers.95 Together, these distinct conformational states that result from unique EGFR mutants (e.g., ECD vs TKD) may partially explain why drugs developed for NSCLC are not able to robustly modulate mutant EGFR signaling in GBM.

The impact of distinct genetic alterations in EGFR on TKI affinity is further complicated by EGFR intra-tumoral heterogeneity.52 Most notably, in patient tumors with the EGFRvIII mutations, over-expression of wtEGFR is invariably present.96 Approximately 25% of patients with GBM have amplification of EGFR with no mutations, suggesting overexpressed wtEGFR may drive gliomagenesis in a subset of GBM patients.32 In support of this idea, numerous preclinical studies have demonstrated that pharmacological and/or genetic ablation of EGFR leads to growth inhibition and cell death in patient-derived wtEGFR amplified GBM models.72,97,98 This dependency on overexpressed wtEGFR for tumor growth is consistent with previous work showing that ectopic introduction of wtEGFR on its own has transforming properties.99 Additionally, studies have shown that cross-talk among wtEGFR and EGFRvIII cells in a single tumor occurs via paracrine or direct physical interactions to stimulate tumor growth and survival.56,65,96 Accordingly, an EGFR TKI that has the ability to target both wtEGFR and ECD mutant EGFR may be necessary to successfully modulate growth of EGFR-mutant GBM tumor cells.

One potential concern about targeting amplified wtEGFR is the potential for “on target, off tumor” toxicity within organs harboring high endogenous EGFR expression, such as the skin and gastrointestinal track.100 Yet, EGFR TKIs with high potency against wtEGFR are tolerated in cancer patients (e.g., erlotinib, gefitinib) and have shown promising clinical activity in non-CNS cancers with wtEGFR amplification.101 Thus, for effective treatment of CNS brain malignancies expressing wtEGFR, like GBM, there is a need for highly brain penetrant drugs to gain sufficient brain exposures for therapeutic effect while also keeping within tolerable levels of “off tumor” toxicity.

Finally, a substantial limitation of current EGFR TKI, including those tested in unsuccessful GBM clinical trials, is their inability to achieve adequate brain exposure (Tables 1 and 2).83 The BBB is selectively permeable to drugs that contain specific physicochemical properties—including low molecular weight, low polar surface area, and a low number of rotatable bonds. Consequently, this physical barrier prevents the passage of > 98% of small molecule drugs.102 Although GBM have areas of BBB disruption, considerable evidence suggests that a large fraction of the tumor is protected by an intact BBB.103 Thus, the low unbound drug exposures of EGFR TKI previously tested in GBM may have also contributed to their therapeutic failure in patients. Pharmacokinetic studies with these TKI have shown that most drugs, except for erlotinib and lapatinib, fail to reach steady state plasma concentrations in patients that would be sufficient to inhibit cell proliferation in vitro. Additionally, early generation TKI have poor brain exposures as suggested by their concentration ratio of unbound drug in brain to blood (Kpuu) (Table 1). While newer TKI such as dacomitinib and osimertinib are theoretically more brain penetrant based on Kpuu, their predicted free drug exposures in patient CNS tumors still fall short of that required to inhibit cell proliferation in vitro.

Table 2.

Clinical Trials of Selected EGFR TKI

| Drugs | Phase | Study type | Dose | Marker | n | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Erlotinib

|

II | rGBM single arm, multi-institution104 | 150 mg for patients not taking EIAEDs 300 mg for patients taking EIAEDs |

No | 48 | ORR 8.4% PFS6 20% mOS 9.7 months |

| II | rGBM randomized, multi-institution30 | 150->200 mg for patients not on EIAEDs 300-> 500 mg for patient on EIAEDs |

No | 110 | Erlotinib arm: ORR 3.7% PFS6 11.4% mOS 7.7 months Control arm: ORR 9.6% PFS6 24.1% mOS 7.3 months |

|

| II | 1st line GBM single arm, single institution with TMZ29 | 100 mg/day of erlotinib during XRT and 150 mg/day after XRT on EIAED and 200 mg/day of erlotinib during XRT and 300 mg/day after XRT taking EIAED |

No | 65 | mOS 19.3 months | |

| I/II | Post Hoc tissue PD/PK, single arm, multi-institutional28 6 Patients one week into erlotinib initiation and 10 on drug around time of progression |

150 mg/day | N/A | 16 | Total drug brain tumor to plasma ratio 0.50 Unable to convincingly determine ↓pEGFR or impact on downstream signaling |

|

Gefitinib

|

II | rGBM single arm, single institution, single agent27 | 500 mg daily dose escalation to 750 mg then 1,000 mg if on EIAED |

No | 57 | ORR 0% PFS6 13% mOS 9 months |

| I/II | 1st line GBM, single arm, multi-institutional, combination (no TMZ)105 | 500 mg daily if not on EIAED 750 mg if on EIAED |

No | 147 | mOS 11.5 months | |

| II | PK/PD rGBM, single arm, multi-institutional, single agent, historical cohort comparison80 | 500 mg daily | No | 22 | Total drug brain tumor to plasma ratio 22 Median tumor concentration 4.1 µg/g ↓pEGFR, no impact on downstream signaling |

|

Lapatinib

|

II | rGBM single arm, multi-institution, single agent106 | 750 mg bid | No | 17 | ORR 0% PFS6 17.6% |

| rGBM, single arm, multi-institutional, single agent, PK/PD39 | 750 mg bid | No | 44 | Estimated PFS6 3% Total drug brain tumor to plasma ratio 0.44 Median tumor concentration 497 nM ↓pEGFR, no impact on downstream signaling |

||

Neratinib

|

II | 1st line GBM unmethylated, randomized, multi-institutional (INSIGhT)107 | No Marker Status known |

74 | ITT population: mPFS 6.0 vs 4.7 months (HR 0.75; P = .12) mOS 13.8 vs 14.7 months (HR 1.01; P = .75) EGFR Activated population: mPFS 6.3 vs 4.6 months (HR 0.58; P = .04) mOS 14.4 vs 15.3 months (HR 0.97; P = .94) |

|

Afatinib

|

II | rGBM randomized, multi-arms, multi-institution108 Afatinib(A) vs Afatinib/TMZ(A/TMZ) vs TMZ |

40 mg/day with or without TMZ (75 mg/day) |

No | 119 | A: ORR 2.4% PFS6 3% mOS 9.8 months A/TMZ: ORR 7.7% PFS6 10% mOS 8 months TMZ: ORR 10.3 % PFS6 23% mOS 10.6 months A = 41 pts A/TMZ = 39 pts TMZ = 39 pts |

Dacomitinib

|

II | rGBM Phase 2 multi-center, single arm, single agent109 | 45 mg/day | EGFR amp (n = 30) EGFR amp and EGFRvIII (n = 19) |

49 | Total: ORR 6.1% PFS 6 10.6% mOS 7.4 months EGFR amp only: ORR 6.6% PFS6 13.3% mOS 7.8 months EGFR amp/EGFRvIII: ORR 5.3% PFS6 5.9% mOS 6.7 mo |

| II | rGBM Phase 2 single center, 3 arms, single agent110 A. PK arm, avastin naïve B. 1st recurrence avastin naïve C. any recurrence, prior avastin |

45 mg/day | EGFR amp | 56 | Arm B only: ORR 3% PFS6 17% mOS 10.0 months Arm A = 10 pts Arm B = 30 pts Arm C = 10 pts Total drug brain tumor to plasma ratio 8.2 Median tumor concentration 478.5 nM |

|

Osimertinib

|

II | rGBM Phase 2 single center, single arm, single agent111 | 240 mg for 3 days followed by 160 mg/day | EGFR amp/p53 wt | 12 | ORR 0% PFS6 0% mOS 5.5 months Average spot trough total drug level 400 nM 48 h pre/post FDG ‐3.2% uptake of FDG |

Abbreviations: bid, twice daily; EIAEDs, enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs; FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose; IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration; KP, brain (brain-to-plasma ratio); KPUU, brain (unbound brain-to-plasma ratio); mo, months; mOS, median overall survival; ORR, objective response rate; pEGFR, phosphorylated-EGFR; PFS6, progression-free survival at 6 months; rGBM, recurrent glioblastoma; TMZ, temozolomide.

Given the lack of durable TKI exposure in the brain, pharmacodynamic studies in clinical trial patients with these TKIs in GBM have yielded variable results. Several clinical trials (Table 2) have also analyzed EGFR TKI pharmacodynamics (PD) in vivo. Lassman et al. compared EGFR activity in resected erlotinib/gefitinib treated tumors with untreated control tissue. EGFR activity was determined via immunoblots for phosphorylated-EGFR (pEGFR) and its downstream signaling mediators, phosphorylated ERK (pERK) and phosphorylated AKT (pAKT). Unfortunately, no association was found between sensitivity to erlotinib or gefitinib and EGFR signaling activity.28 In contrast, Hegi et al. found a significant decrease in pEGFR in gefitinib treated (n = 22) compared to untreated patients (n = 12). However, an increase in pERK was seen in treated patients. While this study showed that gefitinib may inhibit EGFR phosphorylation in vivo, it did not modulate downstream EGFR signaling.80 A multi-center clinical trial with lapatinib also found lower pEGFR in treated tumors.39 These limited PD studies show that some TKI may reduce EGFR phosphorylation in patient tumors, but their ability to modulate downstream MAPK, PI3K, and STAT3 signaling or other functional pathways linked to meaningful target inhibition remain unclear. Collectively, these studies suggest that existing EGFR TKI, developed for non-CNS malignancies and repurposed for GBM, are unable to reach diffusely invasive CNS tumor cells at biologically active concentrations and fail to yield a strong, durable therapeutic effect (Table 1). These pharmacokinetic failures support the argument that development of EGFR TKI specifically for CNS tumor indications is warranted.

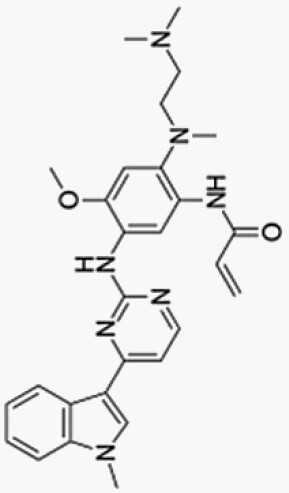

As EGFR TKI developed for NSCLC are neither sufficiently brain penetrant nor capable of targeting the unique forms of altered EGFR found in GBM, EGFR TKI specific for GBM need to be developed with these challenges in mind. Work from our group and others has recently identified a series of EGFR TKI that appear to fulfill these criteria in preclinical GBM models. For example, the prototype compound JCN037 is an EGFR TKI that displays over 200% brain to plasma penetration (>100% unbound levels), is highly potent against hyperactivated wtEGFR as well as ECD mutant EGFR (e.g., EGFRvIII), and improves survival of orthotopic EGFR-altered xenografts better than both lapatinib and erlotinib.79 Based on the combined activity and brain-penetrating properties of JCN037, this scaffold was used to develop ERAS-801 as a clinical candidate which is now in Phase 1 trials for GBM patients (NCT05222802). Similarly, BDTX-1535 is an EGFR TKI that was designed to potently target ECD mutant EGFR as well as achieve high CNS penetration (55% unbound levels in rats). Preclinical data of BDTX-1535 in an orthotopic GBM PDX model support its ability to inhibit in vivo tumor growth and prolong survival. Given these encouraging preclinical data, BDTX-1535 has advanced to early clinical trials in GBM and lung cancer patients (NCT05256290). Although these novel drugs appear to address the unique challenges of EGFR-driven GBM relative to NSCLC, it remains to be seen if ERAS-801, BDTX-1535 or other newly developed EGFR TKI display efficacy in GBM patients.

EGFR TKI Resistance

In addition to challenges associated with the exposures of EGFR TKI, preclinical studies of GBM have shown that EGFR TKI can induce several adaptive cellular and molecular mechanisms that may drive therapeutic resistance in the clinic. These can typically be categorized clinically as either primary (lack of objective clinical response), or secondary (recurrence following initial response).154 However, these designations do not address the cellular and molecular dynamics of targeted therapeutic resistance, which can be classified as either intrinsic or acquired. Intrinsic resistance refers to selection and clonal outgrowth of cells harboring bona fide resistance mutations.155 Conversely, acquired resistance may result from the acquisition of de novo mutations, or adaptive transcriptional and signaling alterations, via epigenetic alterations and changes in protein dynamics, respectively.155 Historically, much of the focus in the field has been on genetic drivers of resistance. A classic example is the EGFRT790M gatekeeper mutation in EGFR-driven NSCLC. In a patient-derived cell line, Sharma et al.156 demonstrated that this mutation emerged from both the clonal outgrowth of pre-existing cells harboring this mutation (intrinsic resistance) as well as from a population of slow growing, drug tolerant persister (DTP) cells that emerged following treatment with EGFR TKI (acquired resistance). Interestingly, despite the heterogeneity of GBM EGFR variants, a genetic mechanism for intrinsic or acquired resistance to EGFR TKI has not been identified. However, EGFR TKI studies with EGFR-driven GBM have identified adaptive mechanisms in response to EGFR TKI.

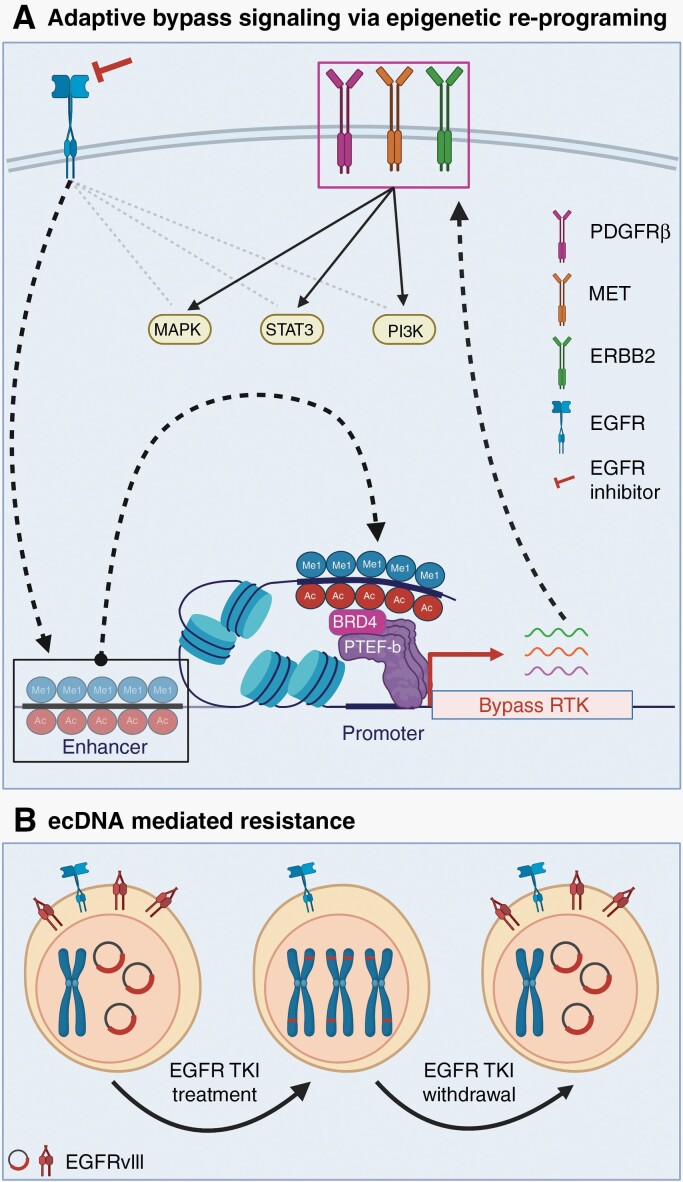

One adaptive mechanism of response to EGFR TKI includes transcriptional de-repression of alternative RTKs, such as PDGFRβ and MET, to facilitate adaptive bypass signaling.157,158 This adaptive kinome response is likely regulated by epigenetic alterations, which have been shown to be involved in kinase inhibitor resistance in other cancers (Figure 5A).159 Indeed, Liu et al.67 found that expression of EGFRvIII in U87 cells induces a malignant epigenetic state via expression of transcription factors that cooperate with the chromatin reader BRD4 to remodel the active enhancer landscape and drive tumorigenesis (Figure 4B). Therapeutic inhibition of oncogenic EGFR signaling likely re-programs the malignant epigenetic state through enhancer remodeling, constituting one possible mechanism of adaptive response to EGFR TKI in GBM (Figure 5A). These preclinical studies suggest that targeting epigenetic mechanisms driving adaptive response to EGFR TKI is a promising avenue for combination therapeutic approaches.

Fig. 5.

Resistance mechanisms to EGFR inhibition. (A) Proposed model: adaptive bypass signaling to EGFR inhibitors via epigenetic re-programing. EGFR inhibition leads to alternate activation of RTK, including PDGFRβ, MET, and ERBB2, potentially via enhancer remodeling-induced adaptive transcription.157,158,160 Enhancer remodeling is driven by the deposition or removal of activating marks (H3K4me1 and H3K27Ac). BRD4 binds these marks and recruits the transcription elongation complex (P-TEFb) to promote transcription pause release.161 (B) EGFRvIII expression in GBM is typically mediated through extra-chromosomal DNA (ecDNA). EGFR TKI treatment of tumors co-expressing wt EGFR and EGFRvIII leads to loss of EGFRvIII ecDNA and mutant receptor expression. EGFRvIII translocates onto chromosomes as homogenous staining regions (HSRs). After withdrawal of EGFR TKI, EGFRvIII ecDNA and mutant receptor expression is restored.63

EGFR Heterogeneity-Mediated Resistance to TKI

Intra-tumoral heterogeneity also contributes to resistance to EGFR-targeted therapeutics. As discussed earlier, GBM have extensive intra-tumoral heterogeneity in EGFR variants. Analysis of GBM patient-derived xenografts (PDX) showed that there are distinct high EGFRvIII-expressing cells (EGFRvIIIhigh) and cells lacking detectable EGFRvIII expression (EGFRvIIIlow) in a single tumor, a difference that is mediated by ecDNA.63 Interestingly, EGFRvIIIhigh cells have increased sensitivity to EGFR TKI compared to EGFRvIIIlow cells. Indeed, treatment with erlotinib, a first-generation EGFR TKI, shifted the tumor composition towards EGFRvIIIlow cells.63 However, EGFRvIIIhigh cells re-emerged after treatment was withdrawn. FISH studies showed that ecDNA harboring EGFRvIII translocate onto cellular chromatin as homogeneous staining regions (HSR) during erlotinib treatment (Figure 5B).63 However, the ecDNA population was regenerated within 72 h of drug withdrawal.63 This suggests that dynamic modulation of EGFR variant heterogeneity contributes to the tumoral fitness of GBM and may promote acquired drug resistance. In another study, Zanca et al.65 found that inter-clonal communication between EGFRvIII and wtEGFR induced expression of genes that attenuate sensitivity to EGFR TKI. EGFRvIII-expressing U87 cells secreted IL-6, which activated NF-κB in wtEGFR-expressing cells. NF-κB cooperated with BRD4 to induce expression of the pro-survival protein survivin (BIRC5), thus attenuating sensitivity to EGFR TKI.65 These preclinical studies show that intra-tumoral EGFR heterogeneity is a significant hurdle to targeted therapeutics and must be considered in the design of future precision oncology regimens for GBM.

Biologics Targeting EGFR

While early clinical trials involved TKI, biologics targeting EGFR quickly followed. These include monoclonal antibodies, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, and peptide vaccines (Table 3). mAb 806, initially raised against EGFRvIII, detects an epitope that is exposed due to the untethered, locally mis-folded state of this mutant receptor or when the wild-type receptor is over-expressed via gene amplification.49,162–164 Initial studies showed that mAb 806 specifically targeted tumor-associated EGFR in animal models and humans.165,166 Given these encouraging results, both a humanized form of mAb 806 (ABT-806), and an antibody-drug (monomethyl auristatin F) conjugated (ADC) form (ABT-414, Depatux-M) have been tested and shown to specifically target primary brain tumors and elicit therapeutic effects in multi-center, prospective trials.117,118,166

Table 3.

Selected Clinical Trials with EGFR Biologics

| Drug | Phase | Study type | Dose | n | Population details and marker selection | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chAb806 | I | Multiple tumor types, single institution, single arm, single agent, single dose, dose escalation112 NCT00291447 |

5–40 mg/m2 5 mg/m2 for AA patient |

8 | 1 AA with EGFRvIII Other patients were non-CNS, EGFR+ |

SD 5 patients PD 3 patients AA patient had SD |

| ABT-806 | I | Multiple tumor types, multi-institution, dose escalation (2 studies combined for PK analysis)113 NCT01255657 NCT01472003 |

2–24 mg/kg q2w for dose escalation | 61 | 11 patients with glioma No biomarker selection |

Not stated |

| I | Multiple tumor types, 2 arm, single agent, dose escalation (DE did not include GBM patients), recurrent tumors114 NCT01255657 |

2–24 mg/kg q2w for dose escalation 24 mg/kg q2w for all GBM patients |

49 | 26 in dose escalation cohort 23 in expanded safety cohort 11 with GBM EGFR high or EGFRvIII-expressing |

No objective responses minimal activity in GBM |

|

| ABT-806i | I | Multiple tumor types, multi-institution, 2-cohort, single agent115 NCT01406119 NCT01472003 |

18 mg/kg (24 mg/kg for some cohort 2 patients none were glioma) Single dose in cohort 1 for initial study, then enrolled into extension study |

18 | 6 in cohort 1 2 with HGG |

Cohort 1: All patients had SD after 1 dose 5/6 had PD after extension study (both HGG patients) high uptake in brain, no quantification |

| Depatuxizumab mafodotin (ABT-414) |

I | Multiple tumor types, multi-institution116 3 arm: ABT-414 ABT-414 + TMZ ABT-414 + TMZ + RT |

0.5–4 mg/kg 0.5–4 mg/kg + TMZ 0.5–4 mg/kg + TMZ + RT |

|||

|

|

I | Multi-institution117 NCT01800695 3 arm: ABT-414+RT+TMZ in 1st line GBM ABT-414+TMZ after RT in 1st line or rGBM ABT alone in rGBM, dose escalating |

Arm A: concurrent phase: 0.5–3.2 mg/kg (for dose escalation) 2 mg/kg (for expansion) q2w + 60 Gy in 30 fractions + 75 mg/m2/day TMZ maintenance phase: 0.5–3.2 mg/kg (for dose escalation) 2 mg/kg (for expansion) q2w + 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle |

45 | 45 patients in Arm A 29 in dose escalation 16 in expansion no biomarker selection |

Arm A only: Total: mPFS 6.1 months EGFR amplified patients: mPFS 5.9 months |

| I | Multi-institution118 NCT01800695 3 arm: ABT-414 + RT + TMZ in 1st line GBM ABT-414+TMZ after RT in 1st line or rGBM ABT alone in rGBM, dose escalating |

Arm B: 0.5–1.5 mg/kg q2w + 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle Arm C: 1.25 mg/kg q2w for dose escalation |

38 | 38 patients 29 in Arm B 9 in Arm C no biomarker selection |

Arm B only: Total: mPFS 3.7 months rGBM: mPFS 17.9months Arm C only: Total: mPFS 2.3 months rGBM: mPFS 7.2 months |

|

| I | Multi-institution119 NCT01800695 3 arm: ABT-414 + RT + TMZ in 1st line GBM ABT-414 + TMZ after RT in 1st line or rGBM ABT alone in rGBM, dose escalating |

0.5–1.5 mg/kg q2w + 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle for dose escalation 1.25 mg/kg + 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle for expansion cohort |

60 | 60 patients 9 in dose escalation cohort 51 in expansion cohort EGFR amplified and/or EGFRvIII rGBM |

ORR 13.8% mPFS 2.1 months mOS 7.4 months |

|

| I | Multi-institution120 NCT01800695 3 arm: ABT-414 + RT + TMZ in 1st line GBM ABT-414 + TMZ after RT in 1st line or rGBM ABT alone in rGBM, dose escalating |

1.25 mg/kg q2w | 66 | 66 patients EGFR amplified rGBM |

Total: mPFS 1.7 months mOS 9.3 months EGFRvIII: mPFS 1.6 months |

|

|

|

I/II | Multiple tumor types, multi-institution, 2 arm, single agent121 NCT01741727 |

1–4 mg/kg q3w or 1–1.5 mg/kg weekly for 2 out of every 3 weeks | 56 | 56 patients unclear if any are glioma EGFR high only |

N/A |

| I/II | Multi-institution122 NCT02590263 2 arm: rGBM: Phase 1: ABT-414 dose escalation, Phase 2: ABT-414 maintenance + TMZ 1st line GBM: ABT-414 dose escalation or maintenance + TMZ + RT |

rGBM: Phase 1: 0.5–1.25 mg/kg q2w dose escalation Phase 2: 1 mg/kg + 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle 1st line GBM: 1–2 mg/kg q2w + 75 mg/m2/day TMZ + 60 Gy in 30 fractions RT for dose escalation 1.5 mg/kg q2w + 75 mg/m2/day TMZ + 60 Gy in 30 fractions RT for maintenance dose |

53 | 53 Japanese patients 9 in rGBM DE arm 29 in rGBM maintenance arm 9 in 1st line GBM DE arm 6 in 1st line GBM maintenance arm 25% grade 3 75% grade 4 no biomarker selection |

rGBM: total: mPFS 2.1 months, mOS 14.7 months EGFR+: mPFS 2.1 months, mOS 14.1 months EGFR-: mPFS6.3 months |

|

| II | Multi-institution, randomized, open label123 NCT02343406 3 arm: ABT-414 + TMZ, ABT-414, lomustine or TMZ at 1st recurrence GBM |

1.25 mg/kg q2w + 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle 1.25 mg/kg q2w 110 mg/m2 lomustine or 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle |

260 | 260 patients 88 in ABT-414 + TMZ arm 86 in monotherapy arm 86 in control arm EGFR amplified rGBM |

QoL did not differ between treatment groups | |

| Observational, multi-institution, single arm, rGBM124 | 1.25 mg/kg q2w + 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle | 36 | 36 patients EGFR amplified rGBM |

mPFS 2.1 months mOS 8.04 months |

||

| Observational, single institution, single arm, rGBM125 | 1.5 mg/kg q2w + 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle | 15 | 15 patients EGFR amplified rGBM |

Corneal side effects present in all patients | ||

| Observational, single institution, single arm, rGBM126 | 1.5 mg/kg q2w + 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle | 10 | 10 patients EGFR amplified rGBM |

Not stated | ||

|

|

I | Multi-institution127 NCT01800695 3 arm: ABT-414 + RT + TMZ in 1st line GBM ABT-414+TMZ after RT in 1st line or rGBM ABT alone in rGBM, dose escalating |

Concurrent phase: 0.5–3.2 mg/kg (for dose escalation) 2 mg/kg (for expansion) q2w + 60 Gy in 30 fractions + 75 mg/m2/day TMZ maintenance phase: 0.5–3.2 mg/kg (for dose escalation) 2 mg/kg for expansion) q2w + 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle |

202 | 202 patients 45 patients in Arm A 82 patients in Arm B 75 patients in Arm C No biomarker selection |

Arms A and B: tumors < 25 cm3 mOS 2.0 years tumors > 25 cm3 mOS 0.8 years |

| II | Multi-institution, randomized, open label128 NCT02343406 3 arm: ABT-414 + TMZ ABT-414 lomustine or TMZ at 1st recurrence |

1.25 mg/kg q2w + 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle 1.25 mg/kg q2w 110 mg/m2 lomustine or 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle |

260 | 260 patients 88 in ABT-414 + TMZ arm 86 in monotherapy arm 86 in control arm EGFR amplified rGBM |

EGFR SNVs associated with response to ABT-414 + TMZ vs. control | |

| II | Multi-institution, randomized, open label129 NCT02343406 3 arm: ABT-414 + TMZ ABT-414 lomustine or TMZ at 1st recurrence |

1.25 mg/kg q2w + 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle 1.25 mg/kg q2w 110 mg/m2 lomustine or 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle |

260 | 260 patients 88 in ABT-414 + TMZ arm 86 in monotherapy arm 86 in control arm EGFR amplified rGBM |

Combo: mPFS 2.7 months mOS 9.6 months Monotherapy: mPFS 1.9 months mOS 7.9 months Control: mPFS 1.9 months mOS 8.2 months |

|

| III | Multi-institution, randomized, double blind130 NCT02573324 2 arm: ABT-414 + TMZ + RT Placebo + TMZ + RT |

2.0mg/kg q2w during RT then 1.25 mg/kg q2w + 75mg/m2 QD during RT then 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle + 60 Gy in 30 fractions Placebo + TMZ + RT |

639 | 638 patients EGFR amplification 323 in ABT-414 +TMZ RT 316 in placebo + ABT-414 + TMZ |

With ABT-414: mPFS 8.0 months mOS 18.9 Without ABT-414: mPFS 6.3 months mOS 18.7 significant difference in mPFS (P = .029) but not mOS |

|

| Nimotuzumab (h-R3) | I/II | Multi-institution, single arm, concurrent radiotherapy131 | 200 mg mAb weekly + 1.8–2 Gy daily (5 days/week) for 5–6 weeks | 29 | 29 patients 16 GBM 12 AA 1 AOD no biomarker selection |

ORR 37.9% ORR 31.3% for GBM mOS 22.17 months mOS 17.47 months for GBM detected in brain, no quantification |

| III | Multi-institution, randomized, open label, 1st line GBM132 NCT00753246 |

400 mg weekly for 12 weeks then q2w + 60 Gy in 30 fractions + 75 mg/m2/day TMZ then 150 mg/m2 TMZ for 6 cycles 60 Gy in 30 fractions + 75 mg/m2/day TMZ then 150 mg/m2 TMZ for 6 cycles |

142 | 142 patients 71 in each arm 1st line GBM no biomarker selection |

With nimotuzumab: mPFS 7.7 months mOS 22.3 months Control: mPFS 5.8 months mOS 19.6 months no significant difference |

|

| Single arm, 1st line GBM133 | 200 mg weekly for 6 weeks + 60 Gy in 30 fractions + 75 mg/m2/day TMZ for 40–42 days then 150–200 mg/m2/day TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle | 26 | 26 Chinese patients no biomarker selection |

mPFS 10 months mOS 15.9 months EGFR did not correlate with PFS or OS |

||

| II | Multi-institution, randomized, double-blind134 | 200 mg weekly for 6 weeks then q3w for 1 year + 180–200 cGy/day (5 days/week) for 5–6 weeks Placebo weekly for 6 weeks then q3w for 1 year + 180–200 cGy/day (5 days/week) for 5–6 weeks |

70 | 70 patients 29 GBM: 15 placebo, 14 nimotuzumab 41 AA: 23 placebo, 18 nimotuzumab no biomarker selection |

All patients: With nimotuzumab: mOS 17.76 months Control: mOS 12.63 months AA only: With nimotuzumab: mOS 44.56 months Control: mOS 17.56 months GBM: With nimotuzumab: mOS 8.4 months Control: mOS 8.36 months |

|

| 188Re-labeled nimotuzumab | I | Multi-institution, single arm, dose escalation, grade 3 and 4 recurrent glioma135 | 3 mg labeled with 370–555 MBq intracranially radiolabel dose escalation |

9 | 9 patients 8 GBM 1 AA EGFR over-expression recurrent glioma |

Not stated |

| ior egf/r3 | I | Single institution, single arm, single agent, recurrent or unresectable brain tumors136 | 40 mg, 80 mg, or 120 mg q4d for 4 doses | 9 | 9 patients 1 meningioma 3 GBM 5 other HGG no biomarker selection |

2 patients alive at 4 years detected in brain no quantification |

| I/II | Multi-institution, single arm, single agent, radiolabeled Ab for tumor detection137 | 3 mg/50 mCi single 99mTc-labeled dose | 148 | 148 patients 8 glioma no biomarker selection |

Study was meant to detect tumors, not treat Detected in brain, no quantification |

|

| I/II | Single institution, single arm, single agent, single dose138 | 1 mg or 3 mg mAb single 99mTc-labeled dose | 9 | 9 patients 1 GBM 1 suspected GBM |

Study was meant to detect tumors, not treat | |

| Losatuxizumab vedotin (ABBV-221) |

I | Multiple tumor types, multi-institution, 12 dose cohorts, recurrent tumor, dose escalation139 NCT02365662 |

0.3–2.25 mg/kg q3w 2–3 mg/kg 2 weeks on, 1 week off 4.5–6 mg/kg weekly 25 mg week 1, 50 mg week 2, 2 mg/kg weekly week 3+ |

45 | 45 patients 5 GBM no biomarker selection |

mPFS 1.4 months |

| AMG-595 | I | Multi-institution, single arm, dose escalation, rGBM140 NCT01475006 |

0.5–5 mg/kg q3w | 32 | 32 patients 30 GBM 2 AA EGFRvIII-positive rGBM |

PR 2 patients SD 15 patients trough plasma concentrations > 4990 ng/mL with doses of ≥ 1 mg/kg |

| Cetuximab (C225) | I | Single arm, single dose141 NCT01884740 |

mannitol + 15 mg/kg bevacizumab + 200 mg/m2 cetuximab |

13 | 13 juvenile patients 2 GBM 1 HGG 10 DIPG no biomarker selection |

6/10 patients had symptomatic improvement |

| I | Multiple tumor types, single arm, dose escalation142 NCT02095054 |

80–120 mg/day regorafenib + 200 mg/m2 cetuximab then 150 mg/m2 weekly cetuximab | 27 | 27 patients 1 GBM no biomarker selection |

PR 1 SD 16 |

|

| II | Multi-institution, stratified, 2 arm143 NCT01044225 |

400 mg/m2 cetuximab on week 1 then 250 mg/m2 weekly | 55 | 55 patients 33 primary GBM 22 secondary GBM 28 with and 27 without EGFR amplification rHGG |

EGFR amplified: PR 2 SD 10 mPFS 1.8 months mOS 4.8 months EGFR nonamplified: PR 1 SD 7 mPFS 1.9 months mOS 5 months |

|

| II | Single arm, rGBM144 | 5–10 mg/kg bevacizumab + 340 mg/m2 irinotecan (for patients on EIAEDs) or 125 mg/m2 (for patients not on EIAEDs) + 400 mg/m2 cetuximab followed by 250 mg/m2 cetuximab weekly for 1 month | 43 | 43 rGBM patients no biomarker selection |

CR 2 PR 9 SD 17 mPFS 16 weeks mOS 30 weeks |

|

| EGFRvIII CAR T scFv (2173) |

I | Single institution, single arm, rGBM145 | 1 CAR T infusion | 10 | 10 rGBM patients varying levels of EGFRvIII |

mOS 247 days |

|

|

I | Single institution, single arm, rGBM146 NCT02209376 |

1.75 × 108–5 × 108 cells, 4.8–25.6% T cells transduced | 10 | 10 rGBM patients varying levels of EGFRvIII |

mOS 251 days |

| EGFRvIII CAR T scFv (139) |

I | Single institution, single arm, dose escalation, rGBM147 NCT01454596 |

60 mg/kg cyclophosphamide for 2 days, then 25 mg/m2 fludarabine for 5 days, then 1 × 107–6 × 1010 CAR T cell infusion, followed by 72000 IU/kg IL-2 q8h 0–10 times | 18 | 18 patients EGFRvIII+ rGBM |

mOS 1.3 months no OR by MRI |

| Rindopepimut (CDX-110) | II | Multi-institution, double-blind, randomized, 2 arm, rGBM148 NCT01498328 |

500 µg rindopepimut + 150 µg GM-CSF on days 1, 15, and 29 then monthly + 10 mg/kg bevacizumab q2w 100 µg keyhole limpet hemocyanin on days 1, 15, and 29 then monthly + 10 mg/kg bevacizumab q2w |

73 | 73 patients 36 treatment 37 control rGBM, EGFRvIII+ |

Treatment: mPFS 3.7 months 24m survival 20% Control: mPFS 3.7 months 24m survival 3% |

| II | Multi-institution, single arm, 1st line GBM149 NCT00458601 |

500 µg rindopepimut + 150 µg GM-CSF on days 1, 15, and 29 then monthly + 200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle | 65 | 65 patients 1st line EGFRvIII+ GBM |

mPFS 9.2 months mOS 21.8 months |

|

| II | Multi-institution, 2 arm150 | Rindopepimut on days 1, 15, 29 then monthly | 21 | 21 patients 18 in analysis EGFRvIII+ |

Treatment:mPFS 14.2 months, mOS 26 months Control: mPFS 6.3 months, mOS 15 months |

|

| I | Single institution, dose escalation, single arm, 1st line GBM151 | 2.3 × 107–1 × 108 rindopepimut-loaded DC on days 1, 15, and 29 | 12 | 12 patients 1st line GBM no biomarker selection |

mPFS (from diagnosis) 10.2 months mOS (from diagnosis) 22.8 months |

|

| II | Multi-institution, 2 arm, 1st line GBM152 | Rindopepimut + 150 µg GM-CSF on days 1, 15, 29 then monthly + 200 mg/m2/day TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle for STD Rindopepimut + 150 µg GM-CSF on days 1, 15, 29 then monthly + 100 mg/m2/day days 1–21 of 28-day cycle for DI |

22 | 22 patients 12 in STD (day 1-5 TMZ) 10 in DI (day 1–21 TMZ) 1st line EGFRvIII+ GBM |

STD: mPFS 15.9 months (from surgery) mOS 21 months (from surgery) DI: mPFS 14.9 months (from surgery) mOS > 18.9 months (from surgery) Historic control: mPFS 6.3 months (from surgery) mOS 15 months (from surgery) |

|

| III | Multi-institution, double-blind, randomized, 2 arm, 1st line GBM153 NCT01480479 |

500 µg rindopepimut + 150 µg GM-CSF + 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle 100 µg keyhole limpet hemocyanin on days 1, 15 then monthly + 150–200 mg/m2 TMZ days 1–5 of 28-day cycle |

745 | 745 patients 371 rindopepimut + TMZ 374 control + TMZ 1st line EGFRvIII+ GBM |

Rindopepimut: mOS 20.1 months Control: mOS 20.0 months |

Abbreviations: AA, anaplastic astrocytoma; AOD, anaplastic oligodendroglioma; DIPG, diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma; GBM, glioblastoma; Gy, gray; HGG, high grade glioma; MBq, megabecquerel; mCi, millicurie; mOS, median overall survival; mPFS, median progression-free survival; ORR, objective response rate; PD, progressive disease; q2w, every 2 weeks; QoL, quality of life; RT, radiotherapy; SD, stable disease; TMZ, temozolomide.

In the INTELLANCE-2/EORTC phase II trial, glioblastoma patients prescreened for EGFR amplification were randomized and treated at first recurrence.123 While the study did not meet its primary endpoint at the initial analysis, there was a trend toward a survival advantage for the Depatux-M arm when combined with TMZ. Statistical significance (P = .017) was indeed reached in the long-term analysis with 2-year survival in the combination arm 19.8%, the Depatux-M monotherapy arm 10%, and the control arm 5.2%. However, one caveat in this multicenter trial is that patients were screened for EGFR status with tissue from initial diagnosis, not at recurrence when patients were enrolled in the study. Furthermore, the attached toxin, monomethylauristatin-F, limited the maximum Depatux-M dose due to ocular toxicity, which likely affected treatment outcomes.64 Except for reported visual disorders, Depatux-M had no impact on HRQOL and NDFS.123 Similarly, in a multi-center, international phase I clinical trial (M12-356) designed as above, Depatux-M in combination with temozolomide displayed an objective response rate of 14.3%, a 6-month progression-free survival rate of 25.2%, and a 6-month overall survival rate of 69.1%. Once again, the most common adverse event was ocular toxicity (63%).119

Early promising results from the INTELLANCE-2 trial with recurrent GBM and unexpected patient accrual in a planned Phase II/III prompted a study redesign to a Phase III trial that utilized Depatux-M in the newly diagnosed setting.130 GBM patients with EGFR amplification were randomized to Depatux-M versus placebo along with radiotherapy and temozolomide after an initial diagnostic surgery. A statistically significant increase (P = .029) in median progression-free survival was found in patients treated with Depatux-M (8 months vs. 6.3 months). Subgroup analysis found that this increase concentrated in patients with EGFRvIII mutation (8.3 months vs. 5.9 months, P = .002). However, no difference in overall survival between the treatment groups was found regardless of EGFRvIII mutational status.130

These results warrant testing of next-generation ABT-806 ADCs, such as ABBV-321, which incorporate a potent pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) dimer that manifests toxicity by DNA-crosslinking and has potential for bystander cell killing due to demonstrated cell permeability.167,168 In support of the continued refinement of EGFR-directed ADCs, a preclinical study by Anami and colleagues169 recently showed that homogeneity of drug conjugation to antibody showed improved payload delivery to brain tumors in animal models, leading to substantially improved tumor growth suppression. In contrast, they also demonstrated that overly drug-loaded antibodies in heterogenous conjugates were particularly poor at crossing the BBB.

EGFR has proven to be a viable target for CAR T cell therapies in GBM. Tumor-specific and immunogenic alterations in an extracellular target are ideal for adoptive T cell therapies. Several completed and ongoing clinical trials, in both adult and pediatric GBM, make use of EGFR as a target (NCT02209376, NCT01454596, NCT03726515, and NCT03638167).146,147 While none have been powered to demonstrate a survival benefit, examination of tumor tissue post-EGFRvIII targeting CAR T infusion has shown both the ability of the peripherally-delivered CAR T cells to penetrate the tumor and to cause antigen editing, with significant loss of EGFRvIII-positive tumor cells.146 Additionally, a long-term survivor from the first EGFRvIII CAR T trial had detectable levels of CAR T cells in circulation roughly three years post-infusion, suggesting long-term tumor control is feasible.170 Building on these encouraging results, current work is focused on expanding the repertoire of CAR T cells that target distinct EGFR variants. 171–173

Taking advantage of the novel EGFRvIII splice junction sequence, rindopepimut, a 14 amino acid EGFRvIII peptide conjugated to the carrier protein keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH), was developed as a pulsed-dendritic cell vaccine approach against GBM.151 It reached Phase II in recurrent GBM (ReACT) and Phase III in newly diagnosed GBM (ACTIV).148,153 While neither trial reached statistical significance for primary endpoints, an exploratory cohort analysis in ACTIV of the subgroup of patients with significant residual disease prior to vaccine administration (as defined by ≥ 2 cm2 of residual enhancing tumor on the post-chemoradiation imaging) did reach significance when comparing the 2-year overall survival rate. Patients receiving the vaccine had a 2-year overall survival of 30% compared to 19% in the control group (P = .029). This finding, although not from the primary endpoint, has since fueled the discussion over the need for target-positive residual tumor in immune-based therapeutic approaches.

Taken together, the EGFR-targeting biological studies prove feasibility of these approaches in GBM. While limitations remain, the existing body of work has identified the necessary hurdles to overcome for more successful treatment approaches. In particular, CAR T work has focused on the dual limitations of target heterogeneity and immunosuppressive microenvironment. Efforts are underway to broaden CAR T targeting ability with clinical trial implementation anticipated soon.174,175 Combination of CAR T cells with immune checkpoint blockade has shown preclinical efficacy in ameliorating the immunosuppressive response.176

Conclusion

We hope that this review serves as a guide to highlight lessons learned from past and current EGFR based precision oncology approaches in GBM. Considering these lessons, it would be scientifically premature to abandon EGFR as a therapeutic target given the prevalence and diversity of EGFR mutations in GBM. Past failures in targeting EGFR in GBM parallel the failures of targeting RAS-driven neoplasms beginning over 40 years ago. Indeed, repeated failures to target RAS and its associated genes led many in the scientific community to declare RAS “undruggable”.177,178 However, in 2013, the RAS Initiative was announced by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to organize government, academic, and industrial researchers to directly challenge this belief.177,179,180 Significant advancements have since been made to understand the biology of RAS, which ultimately led to the development and FDA approval of sotorasib for KRAS G12C driven lung cancers.181,182 Similar to how the Lazarus-like target RAS was resurrected as “druggable” despite decades of setbacks, the current shortcomings with EGFR based precision oncology approaches in GBM provide lessons that could serve to re-invigorate the neuro-oncology field.

Knowledge of EGFR biology and therapeutic design from other EGFR-driven neoplasms can serve as an investigational roadmap but cannot be generalized to every type of disease. In GBM, the unique mutational spectrum concentrated in the ECD and the extensive EGFR heterogeneity drive the biology of this devastating disease. Better EGFR drugs need to be developed to not only address the challenges brought about by inter- and intra-tumoral heterogeneity and ecDNA, but also by the BBB. Additionally, clinical biomarkers of vulnerability need to be developed to identify likely responders. These biomarkers will prove critical for design of early phase, window of opportunity trials that examine pharmacodynamic drug effects as well as biological and clinical responses. To date, clinical trials have not shown sustained inhibition of EGFR and its downstream effectors, which is likely required for durable therapeutic effects. The wealth of preclinical knowledge on potential EGFR resistance mechanisms, such as dynamic regulation of ecDNA and adaptive bypass signaling, indicates that the neuro-oncology community is prepared to address challenges downstream of drug discovery, particularly the development of novel drug combinations for use in the newly diagnosed disease setting. These advances have spurred new drug discovery and development programs in both academia and industry to pursue new precision oncology approaches for the Lazarus-like target EGFR in GBM.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Laura Orellana for her thoughtful insights, as well as providing original artwork for (Figure 2D–E). Figures 2D and E are adapted from Orellana et al. 2019 and reprinted with permission from PNAS. Figures 2A–C are adapted from Huang et al. 2009 with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Several figures were created with BioRender.com.

Contributor Information

Benjamin Lin, Department of Pathology, Division of Neuropathology, Heersink School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Julia Ziebro, Department of Pathology, Division of Neuropathology, Heersink School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Erin Smithberger, Department of Pathology, Division of Neuropathology, Heersink School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Pathobiology and Translational Sciences Program, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Kasey R Skinner, Department of Pathology, Division of Neuropathology, Heersink School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Neurosciences Curriculum, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Eva Zhao, Department of Molecular and Medical Pharmacology, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Timothy F Cloughesy, Department of Neurology, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Zev A Binder, Department of Neurosurgery and Glioblastoma Translational Center of Excellence, Abramson Cancer Center, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Donald M O’Rourke, Department of Neurosurgery and Glioblastoma Translational Center of Excellence, Abramson Cancer Center, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

David A Nathanson, Department of Molecular and Medical Pharmacology, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Frank B Furnari, Department of Medicine, Division of Regenerative Medicine, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, USA; Ludwig Cancer Research, San Diego, California, USA.

C Ryan Miller, Department of Pathology, Division of Neuropathology, Heersink School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Funding

BL is funded by the Medical Scientist Training Program at UAB Heersink School of Medicine through T32GM008361. JZ is funded by the AMC21 Scholars Program from UAB Heersink School of Medicine and by a NextGen Scholars grant from the UAB O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center. KRS is funded by the National Cancer Institute (F31 CA247177). DAN and TFC are funded by the Uncle Kory Foundation, Kurland Family Foundation, National Brain Tumor Society, Spiegelman Family Foundation in Memory of Barry Spiegelman, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS121319) and the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA227089, R01 CA213133, P50 CA211015). DMO is funded by The Templeton Family Initiative in Neuro-Oncology, The Maria and Gabriele Troiano Brain Cancer Immunotherapy Fund, The Herbert & Diane Bischoff Fund, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01 NS042645). FBF is funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01 NS080939, R01 NS116802). DMO, FBF, and CRM are funded by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA258248). CRM is also funded by the UAB O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center through the National Cancer Institute (P30 CA013148).

Conflict of Interest.