Key Points

Question

Can scalable approaches to nudge clinicians, patients, or both increase initiation of a statin prescription during primary care visits?

Findings

In this cluster randomized clinical trial of 4131 patients from 28 primary care practices, nudges to clinicians using electronic health record active choice prompts and monthly peer comparison feedback significantly increased statin prescribing by 5.5 percentage points relative to usual care. Nudges to patients by text message before the visit did not significantly increase statin prescribing, but the combination of nudges to clinicians and patients significantly increased statin prescribing by 7.2 percentage points relative to usual care.

Meaning

Electronic health record–based nudges can be an effective and scalable approach to change prescribing behavior.

This cluster randomized clinical trial in a single health care system investigates the effectiveness of patient and clinician nudges to increase statin prescribing.

Abstract

Importance

Statins reduce the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events, but less than one-half of individuals in America who meet guideline criteria for a statin are actively prescribed this medication.

Objective

To evaluate whether nudges to clinicians, patients, or both increase initiation of statin prescribing during primary care visits.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cluster randomized clinical trial evaluated statin prescribing of 158 clinicians from 28 primary care practices including 4131 patients. The design included a 12-month preintervention period and a 6-month intervention period between October 19, 2019, and April 18, 2021.

Interventions

The usual care group received no interventions. The clinician nudge combined an active choice prompt in the electronic health record during the patient visit and monthly feedback on prescribing patterns compared with peers. The patient nudge was an interactive text message delivered 4 days before the visit. The combined nudge included the clinician and patient nudges.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was initiation of a statin prescription during the visit.

Results

The sample comprised 4131 patients with a mean (SD) age of 65.5 (10.5) years; 2120 (51.3%) were male; 1210 (29.3%) were Black, 106 (2.6%) were Hispanic, 2732 (66.1%) were White, and 83 (2.0%) were of other race or ethnicity, and 933 (22.6%) had atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. In unadjusted analyses during the preintervention period, statins were prescribed to 5.6% of patients (105 of 1876) in the usual care group, 4.8% (97 of 2022) in the patient nudge group, 6.0% (104 of 1723) in the clinician nudge group, and 4.7% (82 of 1752) in the combined group. During the intervention, statins were prescribed to 7.3% of patients (75 of 1032) in the usual care group, 8.5% (100 of 1181) in the patient nudge group, 13.0% (128 of 981) in the clinician nudge arm, and 15.5% (145 of 937) in the combined group. In the main adjusted analyses relative to usual care, the clinician nudge significantly increased statin prescribing alone (5.5 percentage points; 95% CI, 3.4 to 7.8 percentage points; P = .01) and when combined with the patient nudge (7.2 percentage points; 95% CI, 5.1 to 9.1 percentage points; P = .001). The patient nudge alone did not change statin prescribing relative to usual care (0.9 percentage points; 95% CI, −0.8 to 2.5 percentage points; P = .32).

Conclusions and Relevance

Nudges to clinicians with and without a patient nudge significantly increased initiation of a statin prescription during primary care visits. The patient nudge alone was not effective.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04307472

Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally.1 Statins, or hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, significantly reduce the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events, including coronary events and stroke,2,3 across a wide range of ages and cardiovascular risk.4,5,6 Despite these benefits, less than 50% of Americans who meet guideline indications for a statin are actively prescribed this medication.7 In addition, appropriate statin prescription varies across practice sites and patient racial and demographic characteristics.8,9

Initiating statin therapy involves both clinician and patient factors. The clinician must recognize that a patient could benefit from a statin and then discuss it with the patient. Patients must understand the benefits and risks associated with a statin and be amenable to taking it. Barriers can exist at each of these steps, presenting opportunities to intervene and improve statin prescribing rates.

Nudges are subtle changes to the way information is framed or choices are offered that can have an outsized impact on behavior.10 In previous work, nudges to primary care clinicians increased statin initiation from 2.6% in the control group to 8.0% in the intervention group when an active choice prompt was combined with monthly peer comparison feedback, but these interventions were implemented outside the electronic health record (EHR).11 An active choice prompt reminds the clinician of a patient’s statin eligibility and requires them to accept or decline a prescription order.12,13 Peer comparison feedback informs clinicians of how their statin prescribing patterns compare with other clinicians within the same health system.11 Both approaches can be automated and delivered through the EHR. In a clinical trial among cardiologists, an active choice prompt in the EHR increased statin prescribing among patients with clinical ASCVD by 3.8 percentage points relative to the control group.12 These previous studies demonstrated the potential impact of these approaches and prompted further research on their integration within a larger primary care network.

More research has been performed on how to improve statin adherence14,15 than on how to improve statin initiation, but nudges for other conditions may serve as a guide. In previous work, nudges delivered to patients by text message in the days preceding a primary care visit significantly increased influenza vaccination.16 This automated approach could be tested to prime patients for a discussion about statins during primary care visits.

A systematic review of randomized trials for increasing statin prescribing revealed that most common interventions have focused on patient education, indicating an opportunity to test the use of nudges to target patient motivation.17 The review also found that patient-targeted approaches were more effective when combined with decision-support tools in the EHR.

The objective of this cluster randomized clinical trial was to evaluate the effect of nudges to clinicians, patients, or both on the initiation of statin prescriptions during primary care visits. These interventions were automated through the EHR, representing a scalable approach to nudge behavior. We hypothesized that both patient and clinician nudges would significantly increase initiation of statin prescriptions and that the combination would be most effective relative to usual care.

Methods

Study Design

This cluster randomized clinical trial was a pragmatic, 4-arm study of 28 primary care practices in urban and suburban Pennsylvania and New Jersey. The trial included a 1-year preintervention period (October 19, 2019, to October 18, 2020) and a 6-month intervention period (October 19, 2020, to April 18, 2021). Analyses were conducted between April 20 and May 25, 2021. The trial compared nudges to clinicians, patients, or both to increase initiation of guideline-directed statin prescriptions during primary care visits. The trial protocol was approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s institutional review board (Supplement 1). Informed consent by both clinicians and patients was waived because the study was a pragmatic evaluation of a health system initiative that posed minimal risk to participants. Neither clinicians nor patients were compensated for their participation. This trial followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Participants

Eligible primary care clinicians at Penn Medicine included attending physicians within the specialties of internal and family medicine who delivered general primary care. Clinicians were excluded if they saw fewer than 10 patients eligible for a new statin prescription during the 12-month preintervention period.

Patients were eligible if they had a routine visit (in-person or telemedicine) with their primary care clinician during the study period and had no EHR documentation of being prescribed a statin. Patients were eligible for statin therapy on the basis of US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines for primary prevention,18 presence of a clinical ASCVD condition, or history of familial hyperlipidemia as indicated by diagnosis code or low-density lipoprotein laboratory value. These criteria were adopted by the health system across primary care practices before the start of the study. US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines include patients aged 40 to 75 years with at least 1 cardiovascular risk factor (dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, or smoking) and a 10-year ASCVD pooled cohort risk equation risk score of 10% or greater.18 Patients were excluded if they had EHR documentation of an allergy to statins, statin intolerance or adverse reaction, severe kidney insufficiency defined as a glomerular filtration rate of less than 30 mL/min or on dialysis, history of rhabdomyolysis of any etiology, history of hepatitis, current pregnancy or breastfeeding, hospice care or at the end of life, or currently on a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor for lipid-lowering therapy.

Patients in all study groups were enrolled in the trial 4 days before a scheduled appointment (the time at which patients in the patient nudge groups would be sent a text message) to ensure a balanced comparison across groups. Patients who cancelled or did not show up to the visit were included in the sample and classified as not having a statin initiated unless one was prescribed within the 72-hour window before the visit.

Data Collection

The Clarity reporting database (Epic Systems) was used to obtain data on patients, clinicians, and practices.11,12 Patient data included clinical encounters; sex, age, and race and ethnicity; insurance; comorbidities; and baseline measures including ASCVD 10-year pooled cohort equation risk score, clinical ASCVD diagnoses, laboratory results, and body mass index. Clinician and practice data included clinician sex, practice location, and statin prescriptions. Data on clinician race and ethnicity were not available. Patient income was imputed from US Census zip code–level median annual household income. Pharmacy dispensing data within 30 days of the visit were available through Clarity via Surescripts software (Surescripts).

Randomization

The 28 practice sites were stratified into 7 groups of 4 practices on the basis of mean statin prescribing rate. Within each stratum, the practices were electronically randomized to 1 of 4 study groups. All study investigators, statisticians, and data analysts were blinded to group assignments until the trial and all analyses were completed.

Interventions

Before initiation of the trial, primary care clinicians and practice managers in all arms were sent an email describing the overall goals of the study and description of the interventions for their specific practice (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Primary care clinicians in the usual care group received no other interventions.

The clinician nudge included 2 components. First, clinicians received an active choice prompt in the EHR (a BestPractice Advisory in Epic), which was triggered when a clinician entered the EHR ordering section. The design of this nudge was adapted from previous work and clinician input.11 The active choice prompt described the guideline criteria for statin therapy, included a calculated 10-year ASCVD risk score, and provided options for a statin dose, with a high dose or regular dose option preselected based on clinical criteria, with alternative options available. The prompt also provided information on statin intensity for easy clinician reference. Examples of the active choice prompt are available in eFigure 1 in Supplement 2. Second, clinicians received monthly peer comparison feedback in the form of a 3-month rolling average of the percentage of their eligible patients prescribed a statin and how that compared with peer clinicians at Penn Medicine. These reports were sent by an EHR message to the clinician’s inbox. The design was adapted from previous work and clinician input.11 Clinicians whose prescribing rate was below the median were compared with the median. Clinicians whose prescribing rate was above the median but below the 90th percentile were compared with top performers, defined as the 90th percentile. Clinicians performing above the 90th percentile were told that they were top performers. Examples of peer comparison feedback are available in eFigure 2 in Supplement 2.

Patient nudges were sent by text messages starting 4 days before their appointment, reminding them of the upcoming appointment and informing them of an important message about their heart health. They were told that text messaging is not 100% secure and that message and data rates may apply (language required by our legal team). Patients had to reply to confirm their willingness to communicate by text, and if so, they were told that “guidelines indicate you should be taking a statin to reduce the chance of a heart attack” and about the benefits of lowering cholesterol and the rare adverse effects that go away upon stopping the medication. Patients were told that “at Penn Medicine, it is standard of care to prescribe a statin to patients like you.” Patients were asked to reply “Y” if they were interested in taking a statin or reply “?” if they were unsure or had questions for the physician. Patients replying “Y” were told to remember to discuss the statin during their visit and sent a link to a shared decision-making tool on statin therapy (Healthwise, Inc). Patients replying with a “?” were told to write down their questions or concerns and share them with their physician at the visit. Patients were sent an additional message 15 minutes before their appointment time: “As a reminder, speak with your doctor about taking a statin medication to reduce your risk of a heart attack.” The text message script is available in eFigure 3 in Supplement 2.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was initiation of a statin prescription by the end of the day of the primary care visit. In exploratory post hoc analyses, we also explored whether a statin was dispensed by a pharmacy within 30 days of the visit.

Statistical Analysis

A priori power calculations used data from Penn Medicine’s EHR and estimated that a sample of 3000 patients among 189 clinicians would provide at least 90% power to detect a difference of 5 percentage points in statin prescribing rates for clinician and patient main effects and at least 80% power to detect a change of 8 percentage points in the clinician-patient interaction effects, each relative to usual care.

All randomly assigned practice sites were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. We evaluated each patient’s first visit during the preintervention and intervention periods. In unadjusted analyses, we calculated the percentage of patients in each period with a statin prescribed during the visit.

We fit mixed-effects models for the outcomes of statin prescription and statin dispensing. The main model adjusted for study group, preintervention statin prescribing rate at the clinician level, calendar month for the intervention period, and random effects to allow for clustering at the clinician and practice level. To test the robustness of our findings, we fit a fully adjusted model that also adjusted for patient age, sex, race and ethnicity, insurance, annual household income, visit type (in person or telemedicine), and Charlson Comorbidity Index. To obtain the adjusted difference among study groups in percentage points and 95% CIs, we used the bootstrap method, resampling patients 1000 times. As in previous work,11,12,19 resampling of patients was conducted by clinician to maintain clustering at the clinician and practice site level (each clinician belonged to only 1 practice).

The main analysis controlled for multiple testing by using a structured testing approach designed for 2 × 2 factorial trials, which prioritizes testing for main effects followed by interaction effects.20 This structure involved first testing the null hypothesis of a main effect of neither clinician nudge nor patient nudge at α = .05. If that test was rejected, then we tested (1) the null hypothesis of no main effect of clinician nudge and (2) the null hypothesis of no main effect of patient nudge at α = .05. If both those tests were rejected, we tested for an interaction at α = .05. This sequential structured testing procedure controlled the familywise type I error rate at a level of 0.05.20 In a secondary analysis at the study group level, we compared each intervention arm with usual care and used a Bonferroni correction with α = .0167. Safety analyses were conducted by reviewing each patient’s EHR for documented adverse events related to statins and then reviewing these events with the data and safety monitoring board. All analyses were conducted using Python, version 3.7.9 software and the statsmodels package, version 0.12.2 (Python Software Foundation).

Results

Study Sample

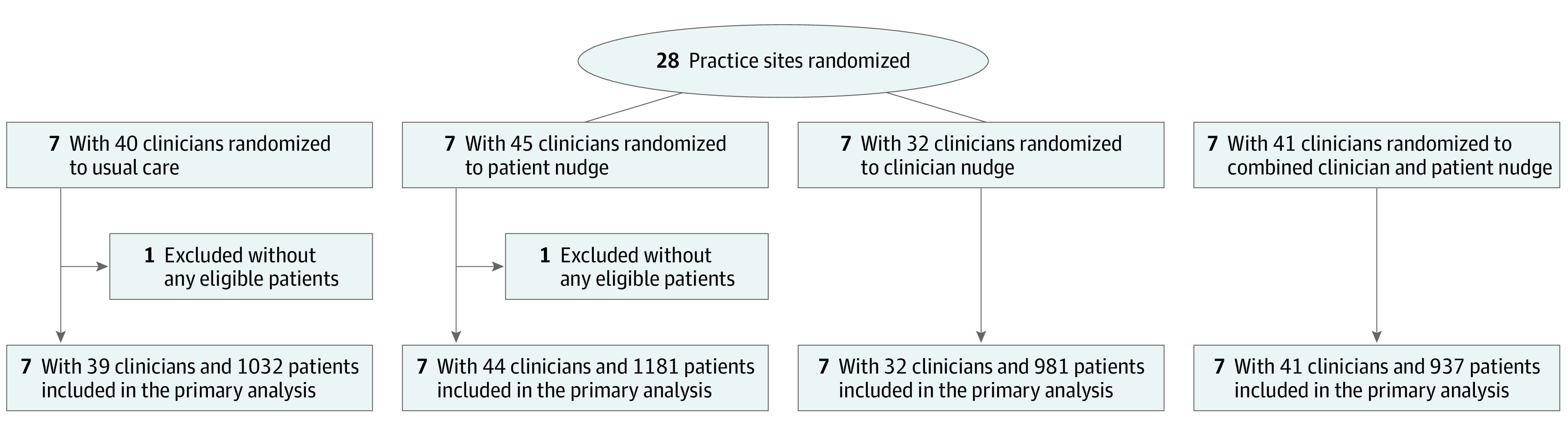

The trial included 158 primary care clinicians from 28 primary care practice sites (Figure). Clinicians included 74 men (46.8%) and 84 women (53.2%); 101 (63.9%) were trained in internal medicine and 57 (36.1%) were trained in family medicine (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). During the intervention period, the sample included 4131 patients with a mean (SD) age of 65.5 (10.5) years; 2120 [51.3%] were men and 2011 [48.7%] were women; 1210 [29.3%] were Black, 106 [2.6%] Hispanic, 2732 [66.1%] White, and 83 [2.0%] of other race or ethnicity, and 933 patients (22.6%) had a diagnosis of ASCVD (Table 1). Most patients had return visits with their primary care clinician (1022 [99.0%] usual care, 1156 [97.9%] patient nudge, 963 [98.2%] clinician nudge, 918 [98.0%] combined nudge). Characteristics of patients during the preintervention period were similar (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Figure. Flow Diagram of Practice Intervention Assignment.

All groups received an email notification about the study. The usual care group received no other interventions. The combined group received both the patient nudge and the clinician nudge interventions.

Table 1. Patient Characteristicsa.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (n = 1032) | Nudge | |||

| Patient (n = 1181) | Clinician (n = 981) | Combined (n = 937) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 64.6 (10.0) | 66.0 (10.6) | 65.6 (10.6) | 65.6 (10.8) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 481 (46.6) | 595 (50.4) | 479 (48.8) | 456 (48.7) |

| Male | 551 (53.4) | 586 (49.6) | 502 (51.2) | 481 (51.3) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Black | 395 (38.3) | 292 (24.7) | 209 (21.3) | 314 (33.5) |

| Hispanic | 18 (1.7) | 26 (2.2) | 26 (2.7) | 36 (3.8) |

| White | 600 (58.1) | 843 (71.4) | 721 (73.5) | 568 (60.6) |

| Otherb | 19 (1.8) | 20 (1.6) | 25 (2.5) | 19 (1.9) |

| Insurance | ||||

| Commercial | 421 (40.8) | 510 (43.2) | 444 (45.3) | 397 (42.4) |

| Medicare | 536 (51.9) | 634 (53.7) | 518 (52.8) | 499 (53.3) |

| Medicaid | 75 (7.3) | 37 (3.1) | 19 (1.9) | 41 (4.4) |

| Annual household income | ||||

| <$50 000 | 327 (31.7) | 206 (17.4) | 135 (13.8) | 230 (24.5) |

| $50 000-$100 000 | 468 (45.3) | 729 (61.7) | 548 (55.9) | 534 (57.0) |

| >$100 000 | 232 (22.5) | 235 (19.9) | 289 (29.5) | 165 (17.6) |

| Missing | 5 (0.5) | 11 (0.9) | 9 (0.9) | 8 (0.9) |

| Practice specialty | ||||

| Family medicine | 534 (51.7) | 456 (38.6) | 376 (38.3) | 185 (19.7) |

| Internal medicine | 498 (48.3) | 725 (61.4) | 605 (61.7) | 752 (80.3) |

| Encounter type | ||||

| In-person visit | 787 (76.3) | 997 (84.4) | 805 (82.1) | 809 (86.3) |

| Telehealth visit | 245 (23.7) | 184 (15.6) | 176 (17.9) | 128 (13.7) |

| Visit type | ||||

| New | 10 (1.0) | 25 (2.1) | 18 (1.8) | 19 (2.0) |

| Return | 1022 (99.0) | 1156 (97.9) | 963 (98.2) | 918 (98.0) |

| Clinical measures | ||||

| Clinical ASCVD | 201 (19.5) | 273 (23.1) | 246 (25.1) | 213 (22.7) |

| ASCVD risk score, mean (SD)c | 16.9 (8.9) | 16.6 (8.61) | 16.2 (8.0) | 17.4 (8.7) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD)d | 29.9 (7.0) | 29.4 (6.4) | 30.0 (6.5) | 29.6 (6.9) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) |

Abbreviation: ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Data are for patients in the intervention period from October 19, 2020, to April 18, 2021.

Other category included American Indian, East Indian, Pacific Islander, left blank, declined to answer, other, and unknown.

ASCVD risk score is only among patients without clinical ASCVD.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Statin Prescribing Outcomes

In unadjusted analyses during the preintervention period, statins were prescribed to 5.6% of patients (105 of 1876) in the usual care group, 4.8% (97 of 2022) in the patient nudge group, 6.0% (104 of 1723) in the clinician nudge group, and 4.7% (82 of 1752) in the combined group. During the intervention period, statins were prescribed to 7.3% of patients (75 of 1032) in the usual care group, 8.5% (100 of 1181) in the patient nudge group, 13.0% (128 of 981) in the clinician nudge group, and 15.5% (145 of 937) in the combined nudge group. Unadjusted changes in statin prescribing from preintervention to intervention by study group are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Adjusted Prescribing Outcomesa.

| Usual care | Nudge | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Clinician | Combined | ||

| Unadjusted prescribing rates | ||||

| Preintervention, No./total No. (%) | 105/1876 (5.6) | 97/2022 (4.8) | 104/1723 (6.0) | 82/1752 (4.7) |

| Intervention, No./total No. (%) | 75/1032 (7.3) | 100/1181 (8.5) | 128/981 (13.0) | 145/937 (15.5) |

| Unadjusted difference in percentage points from pre- to postintervention (95% CI) | 1.7 (0.1 to 3.2) | 3.7 (2.1 to 5.2) | 7.0 (5.1 to 9.0) | 10.8 (8.8 to 12.8) |

| Main adjusted model b | ||||

| Difference in percentage points relative to usual care (95% CI) | NA | 0.9 (−0.8 to 2.5) | 5.5 (3.4 to 7.8) | 7.2 (5.1 to 9.1) |

| P value relative to usual care | NA | .32 | .01 | .001 |

| Fully adjusted model c | ||||

| Difference in percentage points relative to usual care (95% CI) | NA | 0.6 (−1.1 to 2.2) | 5.5 (3.2 to 8.1) | 7.0 (4.9 to 9.0) |

| P value relative to usual care | NA | .46 | .02 | .001 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Statin prescribing by the end of the day of the primary care visit.

Adjusted for study arm, calendar month for the intervention period, preintervention statin prescribing rates at the clinician level, and random effects at the clinician and practice level.

Also adjusted for patient age, sex, race and ethnicity, insurance, annual household income, and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Main Effects Analysis

In the main effects analysis of statin prescribing relative to usual care, there was a significant increase in statin prescribing for the clinician nudge (5.5 percentage points; 95% CI, 3.9 to 7.8 percentage points; P < .001) but not for the patient nudge (0.9 percentage points; 95% CI, −0.8 to 2.3 percentage points; P = .24). Because there was no significant change in the patient nudge arm, we did not test for an interaction effect, in keeping with the prespecified testing procedure. There were no significant differential main effects by patient sex, race and ethnicity, insurance, or annual household income (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

Study Arm–Level Analysis

In the main adjusted analyses of each intervention relative to usual care, the clinician nudge significantly increased statin prescribing alone (5.5 percentage points; 95% CI, 3.4 to 7.8 percentage points; P = .01) and when combined with the patient nudge (7.2 percentage points; 95% CI, 5.1 to 9.1 percentage points; P = .001) (Table 2). The patient nudge alone did not change statin prescribing relative to usual care (0.9 percentage points; 95% CI, −0.8 to 2.5 percentage points; P = .32). Results were similar in the fully adjusted model (Table 2).

Exploratory Analysis

Statin prescribing rates by clinical ASCVD status and ASCVD risk by study group are listed in eTable 4 in Supplement 2. Among intervention groups, the largest-magnitude increases in statin prescribing were among patients with higher ASCVD risk scores. In analyses of statin dispensing, changes between intervention groups and usual care were similar to that of prescribing, but only the combined nudge group was significantly different than usual care (7.2 percentage points; 95% CI, 5.2-9.2 percentage points; P < .001) (Table 3).

Table 3. Adjusted Dispensing Outcomesa.

| Usual care | Nudge | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Clinician | Combined | ||

| Unadjusted dispensing rates | ||||

| Preintervention, No./total No. (%) | 149/1876 (7.9) | 141/2022 (7.0) | 148/1723 (8.6) | 136/1752 (7.8) |

| Intervention, No./total No. (%) | 98/1032 (9.5) | 121/1181 (10.2) | 129/981 (13.1) | 162/937 (17.3) |

| Unadjusted difference in percentage points from pre- to postintervention (95% CI) | 1.6 (−0.3 to 3.4) | 3.3 (1.5 to 5.0) | 4.6 (2.5 to 6.6) | 9.5 (7.4 to 11.7) |

| Main adjusted model b | ||||

| Difference in percentage points relative to usual care (95% CI) | NA | 1.0 (−0.7 to 2.6) | 3.6 (1.5 to 5.7) | 7.2 (5.2 to 9.2) |

| P value relative to usual care | NA | .29 | .07 | <.001 |

| Fully adjusted model c | ||||

| Difference in percentage points relative to usual care (95% CI) | NA | 0.8 (−1.0 to 2.5) | 3.8 (1.6 to 6.2) | 7.3 (5.2 to 9.2) |

| P value relative to usual care | NA | .33 | .07 | <.001 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Statin dispensing within 30 days after the primary care visit.

Adjusted for study arm, calendar month for the intervention period, preintervention statin prescribing rates at the clinician level, and random effects at the clinician and practice level.

Also adjusted for patient age, sex, race and ethnicity, insurance, annual household income, and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Text Message Interactions

Among patients receiving the text message nudge, 33.5% (710 of 2118 patients) consented to receive the intervention message. Among those who consented, 13.8% (98 of 710) texted back that they were interested in taking a statin, and 43.1% (306 of 710) texted back that they were unsure or had questions.

Safety Analysis

Among the 4131 patients in the trial, there were 3 adverse events (0.1%) possibly related to the trial and 5 adverse events (0.1%) related to the trial. Among the 3 possibly related events, 2 were reported as diarrhea and 1 reported as the patient feeling “off.” Among the 5 related events, 3 were reported as myalgia and 2 as increased creatinine levels. There were no serious adverse events reported in the trial.

Discussion

In this cluster randomized clinical trial among 28 primary care practices, clinician nudges alone and combined with patient nudges significantly increased the initiation of a statin prescription during primary care visits. Patient nudges alone were not effective. To our knowledge, this study is one of the largest clinical trials testing nudges to clinicians and patients. Because these interventions were automated through the EHR, they provide a scalable template that can be used by health systems more broadly to improve patient care.

This trial yields 4 main insights. First, the combination of nudges to clinicians and patients had the largest effect. It increased the initiation of a statin prescription during the visit by 10.8 percentage points from preintervention to intervention and by 7.2 percentage points more than usual care. These findings are similar to previous work that found that financial incentives led to greater improvement in lipid management when delivered to both patients and clinicians than to either patients or clinicians alone.21

Second, the clinician nudge alone was effective at increasing statin prescribing. In a previous clinical trial, members of our group found that active choice with peer comparison feedback led to larger increases in statin prescribing than active choice alone,11 which may be because the 2 approaches nudged clinicians in different ways. Peer comparison feedback uses norms to motivate clinicians toward the benchmarks set by their colleagues, and information is delivered at regular intervals but not specific to an individual patient or visit.22 The active choice intervention is patient specific and triggered when the clinician enters the orders section of the EHR, typically during a patient visit. This latter approach may have facilitated action that reinforced the norms set by the regular feedback. Both interventions were delivered through the EHR, likely fitting better within clinician workflow than approaches outside the EHR and facilitating scaling elsewhere. In exploratory analyses of statin dispensing, the clinician nudge alone was not effective. This finding warrants further study and may indicate that this approach might benefit from additional interventions to increase statin dispensing.

Third, the active choice prompt in the EHR to clinicians was codesigned by leadership and frontline clinicians in the health system, which may have improved its utility and adoption. Compared with previous work,11,12 we made several important changes to the prompt’s design. The patient’s indication for a statin and the ASCVD 10-year risk score were displayed within the alert, which may have improved clinicians’ understanding of the need for a statin and their trust in the alert. Timing of the alert was changed from when clinicians open a patient’s chart to when they enter the orders section, which may be a better time for clinicians to discuss statins with the patient. Finally, statin orders were preselected on the basis of the patient’s risk (moderate or high intensity), and a full chart with dosing options was made available in case a clinician wanted to select another statin. Design details like these are often critical to intervention success.23 Future studies could evaluate the durability of these approaches as additional changes are made to the EHR.

Fourth, the patient nudge alone was not effective. Only one-third of patients agreed to receive the text message, dampening its overall effect. Among those who did agree, approximately one-third did not interact with the messaging. In previous work using a similar approach, interactive text messaging was less effective at increasing vaccination than text messaging that simply pushed information to patients.16 Future research could try other communication channels, different consent processes, or less interactive text messaging designs.

Overall, even with nudges, statin prescribing was low. It is important to recognize that approximately 70% of primary care patients eligible for statins in these practices already had the medication prescribed. This trial targeted the remaining cohort of patients. Because 98% of these patients had return visits with their primary care clinician, this may not have been the first opportunity to discuss statins. It is possible that many of these patients were resistant to statins in the past, which could have created a ceiling effect for prescribing rates. Nonetheless, some of the interventions were effective at nudging prescribing in this cohort of patients.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the trial was conducted within a single health system. This health system was an academic medical center and had high baseline rates of statin prescribing; therefore, findings from this trial may not be generalizable to other health systems with different characteristics. Second, we could not disentangle the effects of the 2 interventions within the clinician nudge group; nevertheless, most practice-based interventions are compound, and in this pragmatic trial, we were aiming to find effects more than to identify narrow mechanisms of action. Third, the trial occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, although by the time the trial started in October 2020, many patients had returned to in-person visits.24 Fourth, this study did not evaluate changes in statin dosing or intensity, patient adherence to statins, or changes in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels.

Conclusions

In this cluster randomized clinical trial, a clinician nudge alone and when combined with a patient nudge significantly increased initiation of a statin prescription during primary care visits. Nudges to patients alone were not effective. These findings demonstrate the potential benefit and scalability of using nudges to change prescribing behavior through automated processes within the EHR.

Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Email Describing the Goals of the Study and the Active Choice Prompts in the Electronic Health Record

eFigure 2. Example of Peer Comparison Feedback to Clinicians in the Electronic Health Record

eFigure 3. Text Messaging Script for the Patient Nudge Arm

eTable 1. Clinician Sample

eTable 2. Patient Sample in Preintervention Period

eTable 3. Subgroup Analyses

eTable 4. Prescribing Rates by Clinical Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) and ASCVD Risk Score

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(10):e177-e232. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. ; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators . Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1267-1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al. ; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration . Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration . Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):407-415. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31942-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, et al. ; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators . The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;380(9841):581-590. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60367-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Collins R, et al. ; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators . Efficacy of cholesterol-lowering therapy in 18,686 people with diabetes in 14 randomised trials of statins: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371(9607):117-125. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60104-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salami JA, Warraich H, Valero-Elizondo J, et al. National trends in statin use and expenditures in the US adult population from 2002 to 2013: insights from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(1):56-65. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.4700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nanna MG, Navar AM, Wang TY, et al. Practice-level variation in statin use and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol control in the United States: results from the Patient and Provider Assessment of Lipid Management (PALM) registry. Am Heart J. 2019;214:113-124. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2019.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nanna MG, Navar AM, Zakroysky P, et al. Association of patient perceptions of cardiovascular risk and beliefs on statin drugs with racial differences in statin use: insights from the Patient and Provider Assessment of Lipid Management Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(8):739-748. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel MS, Volpp KG, Asch DA. Nudge units to improve the delivery of health care. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(3):214-216. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1712984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel MS, Kurtzman GW, Kannan S, et al. Effect of an automated patient dashboard using active choice and peer comparison performance feedback to physicians on statin prescribing: the PRESCRIBE cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(3):e180818. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adusumalli S, Westover JE, Jacoby DS, et al. Effect of passive choice and active choice interventions in the electronic health record to cardiologists on statin prescribing: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(1):40-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keller PA, Harlam B, Loewenstein G, Volpp KG. Enhanced active choice: a new method to motivate behavior change. J Consum Psychol. 2011;21(4):376-383. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2011.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rash JA, Campbell DJ, Tonelli M, Campbell TS. A systematic review of interventions to improve adherence to statin medication: what do we know about what works? Prev Med. 2016;90:155-169. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bond Z, Scanlon T, Judah G. Systematic review of RCTs assessing the effectiveness of health interventions to improve statin medication adherence: using the behaviour-change technique taxonomy to identify the techniques that improve adherence. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(10):1282. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9101282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milkman KL, Patel MS, Gandhi L, et al. A megastudy of text-based nudges encouraging patients to get vaccinated at an upcoming doctor’s appointment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(20):e2101165118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2101165118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sparrow RT, Khan AM, Ferreira-Legere LE, et al. Effectiveness of interventions aimed at increasing statin-prescribing rates in primary cardiovascular disease prevention: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(11):1160-1169. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.3066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316(19):1997-2007. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.15450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manz CR, Parikh RB, Small DS, et al. Effect of integrating machine learning mortality estimates with behavioral nudges to clinicians on serious illness conversations among patients with cancer: a stepped-wedge cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(12):e204759. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.4759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Small DS, Volpp KG, Rosenbaum PR. Structured testing of 2x2 factorial effects: an analytic plan requiring fewer observations. Am Stat. 2011;65(1):11-15. doi: 10.1198/tast.2011.10130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asch DA, Troxel AB, Stewart WF, et al. Effect of financial incentives to physicians, patients, or both on lipid levels: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(18):1926-1935. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.14850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navathe AS, Emanuel EJ. Physician peer comparisons as a nonfinancial strategy to improve the value of care. JAMA. 2016;316(17):1759-1760. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.13739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox CR, Doctor JN, Goldstein NJ, Meeker D, Persell SD, Linder JA. Details matter: predicting when nudging clinicians will succeed or fail. BMJ. 2020;370:m3256. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mizuno A, Patel MS, Park SH, Hare AJ, Harrington TO, Adusumalli S. Statin prescribing patterns during in-person and telemedicine visits before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14(10):e008266. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.008266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Email Describing the Goals of the Study and the Active Choice Prompts in the Electronic Health Record

eFigure 2. Example of Peer Comparison Feedback to Clinicians in the Electronic Health Record

eFigure 3. Text Messaging Script for the Patient Nudge Arm

eTable 1. Clinician Sample

eTable 2. Patient Sample in Preintervention Period

eTable 3. Subgroup Analyses

eTable 4. Prescribing Rates by Clinical Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) and ASCVD Risk Score

Data Sharing Statement