Abstract

Study Objectives:

Scoring a polysomnogram is an essential skill for sleep medicine trainees to meet Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Sleep Medicine Milestones. Appraisal is based on faculty evaluation rather than objective competency assessment. We developed a computer-based polysomnogram scoring curriculum, utilizing the mastery learning method, then compared achievement of competency using the new curriculum against standard institutional training.

Methods:

The scoring program consisted of a pretest assessment, sequential acquisition of knowledge utilizing online modules, a posttest, and competency assessment. Fellows needed to demonstrate mastery of each module before moving ahead. Competency was demonstrating ≥ 90% on interscorer reliability assessment on 5 studies (out of up to 10 attempts). Participating fellows were assigned to Mastery Learning Participants (MLP) or Traditional Learning Participants (TLP) groups and completed the program within the first 1–3 months of training.

Results:

Of 87 fellows enrolled in the program, 75 participants completed the program (40 MLP and 35 TLP). Among completers, there was no difference in the proportion that achieved competency (MLP 90.0% vs TLP 97.1%; P = .36) or studies needed to achieve competency (MLP 7.25 ± 1.3 vs TLP 7.41 ± 1.3; P = .60). Pretest scores were not significantly different between groups (MLP 61.2% ± 15.9 vs TLP 57.6% ± 16.6; P = .35), but MLP posttest scores were higher than TLP (MLP 80.9% ± 8.8 vs TLP 76.4% ± 9.8; P = .04).

Conclusions:

We demonstrated similar outcomes utilizing a novel, computer-based modular interactive course compared to traditional methods of teaching polysomnogram scoring. We used a mastery learning paradigm and set specific objective competency levels for this skill.

Citation:

Epstein LJ, Plante DT, Rosen IM. Mastery learning program to teach sleep study scoring. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18(12):2745–2750.

Keywords: polysomnogram, scoring, mastery learning, competency

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Current sleep study scoring training is institution dependent and uses subjective rather than objective competency assessments.

Study Impact: We introduced a modular mastery learning curriculum and demonstrated equivalent outcomes with traditional training using an objective competency assessment. This program provides a method to standardize training and competency assessment for this foundational skillset.

INTRODUCTION

Scoring a polysomnogram (PSG) is an essential skill for board-certified sleep medicine physicians. One of the required Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Sleep Medicine Milestones for sleep medicine fellows is “Interpretation of Physiologic Testing in Sleep Medicine Across the Lifespan (Patient Care 4)”1 and scoring and interpreting PSGs is considered a core patient care skill.2 Currently, assessment of acquisition of this skill is based on faculty evaluation that the fellow has met the milestone and has scored at least 25 PSGs.2 No specific competency levels or time frame have been set for the scoring skill, other than by the end of the 12-month fellowship.

Rules for scoring a PSG are established by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) and set forth in The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications.3 It is possible to quantify mastery of scoring using interscorer reliability testing, comparing a person’s scoring of a sleep study against a gold standard version. While this method4 has been utilized in many sleep centers for quality assurance purposes, it has not been used as a competency assessment in a learning program.

We have developed a computer-based curriculum that utilizes the mastery learning method5 to teach the skill of sleep study scoring. Mastery learning is a form of competency-based education that utilizes a standardized procedure (see Table 1) with measurable outcomes to assure that all learners accomplish the educational objectives. In our case, sleep fellows must reach a predetermined proficiency utilizing interscorer reliability testing to mark achievement of competency. In this study, we compare utilization of this new standardized curriculum against the standard method to achieve competency in sleep study scoring.

Table 1.

Features of a mastery learning program.

| Baseline or diagnostic assessment. |

| Clear learning objectives, sequenced as units of increasing difficulty. |

| Educational activities focused on reaching the objectives. |

| A fixed minimum passing standard for each educational unit. |

| Formative assessment with specific feedback for each unit. |

| Advancement to the next unit only once the mastery standard is surpassed. |

| Continued practice or study on a unit until the mastery standard is reached. |

From: McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Barsuk JH, Wayne DB. A critical review of simulation-based mastery learning with translational outcomes. Med Educ. 2014;48:375–385.

METHODS

The sleep scoring mastery learning program utilizes initial baseline skill assessment, sequential acquisition of knowledge utilizing interactive online modules and assessment of competency. The modules combine video instruction with hands on scoring tasks that provide feedback on participant responses (see Figure 1). The program includes modules on signal acquisition, waveforms, sleep staging, and event recognition (arousal, respiratory and movement events), a total of 16 modules with an average of 13 questions per module (ranging from 6 to 35 questions). Each module builds on the prior modules and the learner must demonstrate competency by getting a score of ≥ 80% to move onto the next level. Final competency is demonstrated by achieving a ≥ 90% score on interscorer reliability assessment on 5 studies drawn from the Inter-Scorer Reliability Assessment System of the AASM.4,6

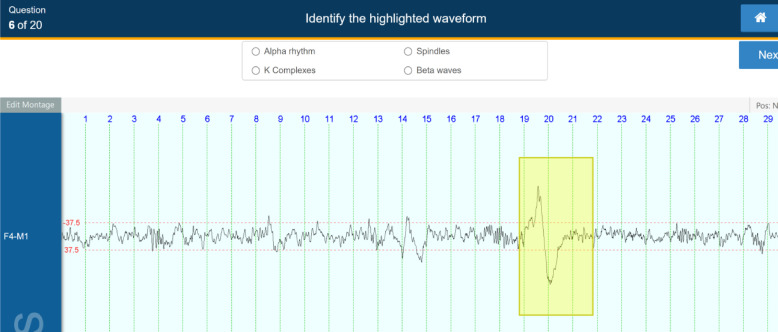

Figure 1. Sample MLP module question.

Following completion of a video on a given topic, in this case waveforms, participants work through module questions, which provide feedback on the proper response. MLP = mastery learning participant.

Participants were recruited from programs participating in the AASM’s Advancing Innovation in Residency Education Pilot Program and fellowship programs represented on the AASM Innovative Fellowship Models Advisory Panel. Details of AASM’s Advancing Innovation in Residency Education program were previously described.7 The competency levels were assigned by consensus of the program directors on the Innovative Fellowship Models Advisory Panel who collectively have over 75 years of sleep fellowship training experience.

Participants were assigned to 1 of 2 groups, Mastery Learning Participants (MLP) or Traditional Learning Participants (TLP). The Advancing Innovation in Residency Education fellows were assigned to the MLP group, while other fellows in their programs were assigned to the TLP program. Other participating programs were randomly assigned to either the MLP or TLP program. Both groups took a baseline pretest knowledge assessment. The MLP fellows then completed the mastery learning program while the TLP fellows received usual institutional training, consisting of didactic and experiential instruction from program faculty. Both groups took a posttest exam to assess their understanding of the subjects, provide the fellows with feedback, and provide Program Directors (PDs) with data on information acquisition. To demonstrate achievement of competency, they then completed the interscorer reliability assessments, with an opportunity to score up to 10 sleep studies to hit the preset competency level. The goal of the program was achievement of competency.

The study was run over 2 academic years. The first group of fellows was instructed to complete the assigned sleep scoring learning program within the first 3 months of the academic year. Upon completion of the trial, feedback surveys were sent to the MLP fellows and their PDs. Based on this feedback, minor modifications were made to the MLP, with addition of short scoring trials prior to the competency testing phase and reduction of the completion time to 1 month.

Statistical analysis utilized Fisher’s exact test to compare proportions and Student’s t-test to compare continuous data. Threshold for statistical significance was set at P = .05 (2-sided) for all comparisons.

RESULTS

We compared achievement of competency on interscorer reliability assessment between the MLP and TLP. We also compared absolute scores on the pretest and posttest and number of studies to achieve competency in each training condition.

Eighty-seven fellows enrolled in the study, 40 in year 1 and 47 in year 2. Forty-six fellows participated in the active MLP group, while 41 participated in the TLP condition. Overall, when considering all fellows enrolled in the study, there was no significant difference between the proportion of MLP vs TLP who reached threshold of scoring competency (80.4% MLP vs 82.9% TLP; P = .79) during their first attempt through the program. One MLP fellow achieved the competency threshold on scoring modules but did not complete the posttest. Also, there was no difference in the proportion of fellows completing the sleep scoring learning program by condition (MLP 87.0% vs TLP 85.4%; P > .99). The fellows averaged 2.0 ± 0.5 attempts/module to achieve competency and took an average of 14.3 minutes (range 4 to 35 minutes) to complete each module.

Table 2 presents the results from the 75 participants who completed their assigned sleep scoring learning program. Among completers, there was no difference in the proportion that achieved competency on the interscorer reliability assessment (MLP 90.0% vs TLP 97.1%; P = .36) or number of studies needed to achieve competency (MLP 7.25 ± 1.3 vs TLP 7.41 ± 1.3; P = .70). Scores on the pretest knowledge assessment were not significantly different between groups (MLP 61.2% ± 15.9 vs TLP 57.6% ± 16.6; P = .35); however, posttest scores were higher among the MLP condition compared to TLP (MLP 80.9% ± 8.8 vs TLP 76.4% ± 9.8; P = .04).

Table 2.

Competency and test results.

| MLP | TLP | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 40 | n = 35 | ||

| Achieving competency [n (%)] | 36 (90.0%) | 34 (97.1%) | .37 |

| #Studies to achieve competency | 7.25 (± 1.3) | 7.41 (± 1.3) | .70 |

| Pretest scores | 61.2 (± 15.9) | 57.6 (± 16.6) | .35 |

| Posttest scores | 80.9 (± 8.7) | 76.4 (± 9.8) | .04 |

Pretest and posttest results are displayed for the MLP and TLP groups who completed all aspects of the training program as well as the number in each group achieving competency and how many studies were required to achieve competency. MLP = mastery learning participants, TLP = traditional learning participants.

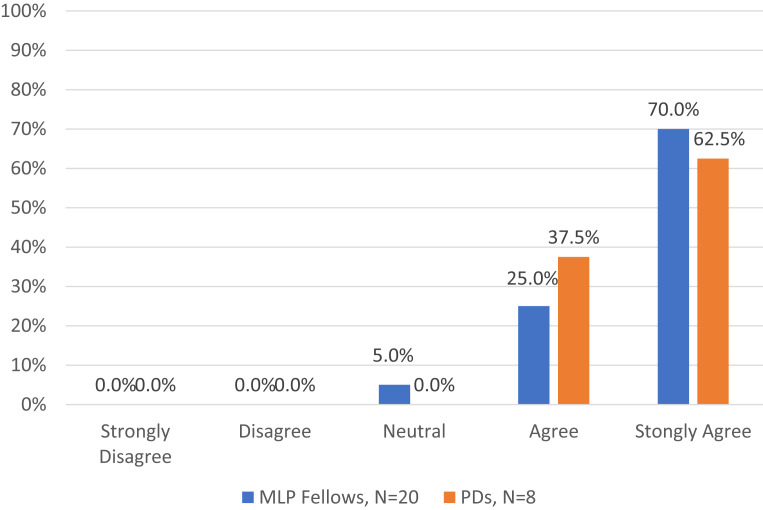

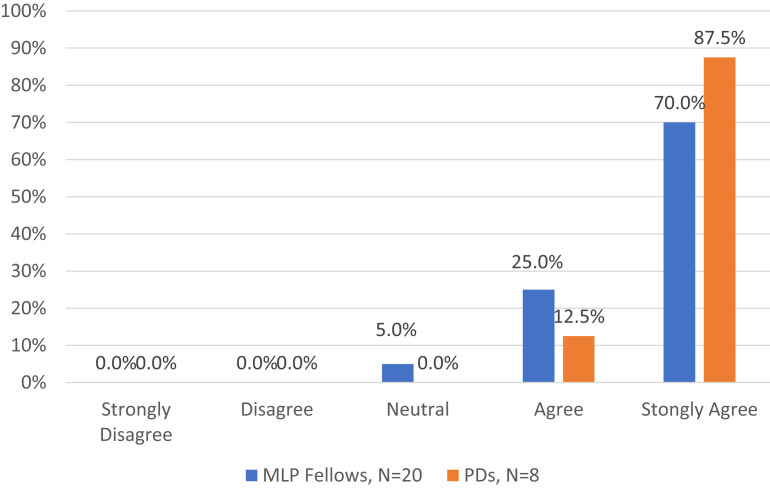

Twenty of the 46 MLP fellows (43%) and 8 of 13 PDs with MLP fellows (62%) completed the postcourse surveys. Overall, 100% of PDs and 95% fellows agreed or strongly agreed with the statement: “The resource helped the fellow understand how to score a PSG.” Similarly, 100% of PDs and 95% fellows agreed or strongly agreed with the statement: “I would recommend using this resource to help Sleep Medicine Fellows gain competency in scoring a PSG.” (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2. Survey results: understand how to score.

This figure shows the MLPs and the PDs responses to the question: The resource helped me/the fellow understand how to score a PSG. MLP = mastery learning participant, PD = program director.

Figure 3. Survey results: recommend resource.

This figure shows the MLPs and the PDs responses to the question: I would recommend using this resource to help Sleep Medicine Fellows gain competency in scoring a PSG. MLP = mastery learning participant, PD = program director.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated similar outcomes utilizing a novel, computer-based modular interactive sleep study scoring course compared to traditional methods of teaching the skill of PSG scoring. This was done using a mastery learning paradigm and, for the first time, setting a specified objective competency level for this task, achieving a predetermined competency level on interscorer reliability assessment of sleep stage and event scoring. Sleep medicine fellows were able to achieve and demonstrate competency in acquisition of the skill within the first 1–3 months of training.

The scoring course was a form of simulation education, in which a person, device or set of conditions are used to present authentic training situations requiring the student to respond as they would under natural circumstances.8 Medical simulation training is used commonly and has been validated as an effective method of education and evaluation. An Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence Report, which reviewed published studies of medical simulation, found that the evidence pointed to the effectiveness of simulation training, especially for psychomotor skills (eg, procedures or physical examination techniques) and communication skills.9

This simulation course utilized the 7 features of mastery learning:10 (1) baseline assessment (pretest); (2) clear learning objectives for each module, sequenced as units increasing in difficulty; (3) engagement in educational activities focused on each objective (educational videos, interactive skills practice, feedback with corrective data); (4) a fixed minimum passing standard for each unit (≥ 80%); (5) assessment with specific feedback of achieving the minimum passing standard for mastery; (6) advancement to the next educational unit only when achievement at or above the mastery standard is demonstrated; and (7) continued practice or study on an educational unit until the mastery standard is reached (> 90% interscorer reliability agreement on a total of 5 studies).

The goal of mastery learning is to ensure that all learners accomplish all educational objectives with little or no variation in outcome. The time to mastery may vary but not the final skill set. Mastery learning has been shown to be successful in medical education, with multiple studies showing simulation-based mastery learning is as effective, and often superior to traditional medical education in achieving specific clinical skill acquisition goals.11

In addition to the objective demonstration of competency, advantages of this type of program include standardization of training objectives and content, ability of the trainees to work at their desired pace, and ability of trainers to shift from didactic to interactive teaching. PDs and fellows participating in this pilot reported they found this a valuable teaching tool that enhanced the fellow’s training and they would recommend incorporating it into training programs.

Medical education is switching from experiential and time-based assessment of learning to competency-based assessment, with the need for trainees to demonstrate mastery of specific objective milestones. This is the basis for the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s utilization of outcomes-based educational milestones to assess and track resident performance. Sleep medicine introduced milestones for assessment of sleep medicine fellows in 2015.12 While the most recent Sleep Medicine Milestones1 calls for assessment of fellows’ ability to interpret physiologic testing in sleep medicine and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Sleep Medicine2 calls for clinical competence in scoring and interpreting PSGs and scoring of at least 25 PSGs during fellowship training, neither define competency in the skill. We set an objective definition of competency in sleep scoring, determined by a consensus of sleep medicine PDs on the Innovative Fellowship Models Advisory Panel. The objective competency level was greater than the one used to measure the competency level of sleep technologists, who score most sleep studies, as mandated by accreditation standards.13 Sleep fellows were able to achieve this level of competency at a high rate using both the scoring course and traditional instructional methods. This standard could serve as a model for all sleep training programs.

There are potential limitations of this study worthy of consideration. First, since this study was a preliminary investigation of a novel mastery learning program, the study was not powered a priori to demonstrate superiority of the program to traditional methods. Rather, similarity of outcomes and acceptability of the program were considered of greater relevance in this stage of its development. The perceived value of the MLP as measured by PD and fellow evaluations was quite high. However, there was not universal response to the survey, which could bias the results toward those who found it of value. The need to adapt the program based on feedback resulted in 2 different time periods for completion of the course (1 month and 3 months in years 1 and 2, respectively). Since both allowable intervals had similar outcomes, an optimal time for completion cannot be established by these data. The composition of the groups could also be a potential source of bias. All of the Advancing Innovation in Residency Education fellows were in the MLP, which could introduce selection bias if there are differences between them and fellows in the traditional pathway. Additional measures of success, such as fellow’s board scores and sleep medicine milestones data, as well as full randomization of all participants, will be needed to assure the value of the standard set for scoring competency. This assessment was designed as a minimum level of competency, additional scoring experience may be required for the fellows to acquire the highest level of mastery as well as ability to interpret the results of the study. Interpretation of sleep studies requires not only learning how to score sleep stages and recognize events but also to integrate the scoring with the patient’s history to make a clinical diagnosis.

The potential for this mastery learning scoring course is not limited to sleep medicine fellows. It could also be used to train sleep technologists, sleep researchers with limited clinical training, and experienced board-certified sleep medicine physicians looking to review or refresh sleep scoring skills. The course can be modified as needed to reflect revisions to the AASM scoring manual and used to update physicians to the changes.

In conclusion, an interactive computer-based sleep scoring course, based on mastery learning principles, achieved similar results to traditional methods in teaching the foundational skills of scoring a PSG. This program was also judged to be useful and was recommended for use by both trainees and PDs. Fellows had to demonstrate an objective level of competency, measured against an established field-level gold standard, and were able to achieve competency as early as the first month of fellowship training. This mastery learning program will be of high value in graduate medical education for sleep medicine by standardizing training and competency assessment of this foundational skillset.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have seen and approved this manuscript. This study was funded by an American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) Advancing Innovation in Residency Education grant. Dr. Epstein is a consultant for the AASM, AIM Specialty Health, eviCore Healthcare, and Somnoware Healthcare Systems. Dr. Plante has served as a consultant for Teva Pharmaceuticals Australia, a consultant for Harmony Biosciences, and consultant/medical advisory board member for Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Plante has also received unrelated research support from the AASM Foundation, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Nursing Research, the Great Lakes Center for Occupational Health and Safety, and the Madison Educational Partnership. Dr. Rosen reports unrestricted educational grant funding from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, royalties from UpToDate, Inc for co-authorship on a card on oxygen delivery and consumption, and consultancy for and medical advisory board member of Huxley Medical, Inc.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the staff of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine for their support in creating the scoring course software and infrastructure, particularly Andrew Sampson, Jacob Davidson, Mary Square, Jason Wilbanks, Sally Podolski, Catherine Elliott, and Steve Van Hout. We also acknowledge the contributions, participation, and support of the AASM’s Innovative Fellowship Models Advisory Panel Committee: Susan Dunning, MD; Barry Fields, MD; Divya Gupta, MD; Vishesh Kapur, MD; Meena Khan, MD; Anita Shelgikar, MD; Sheila Tsai, MD; and Ian Weir, MD.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AASM

American Academy of Sleep Medicine

- MLP

mastery learning participants

- PDs

program directors

- PSG

polysomnogram

- TLP

traditional learning

REFERENCES

- 1. Bagai K , Doo L , Dredla B , et al. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education . Sleep medicine milestones. 2019. . https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/PDFs/Milestones/SleepMedicineMilestones2.0.pdf?ver=2019-12-12-095426-920&ver=2019-12-12-095426-920 .

- 2. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) . ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in sleep medicine. 2021. . https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/520_sleepmedicine_2022.pdf .

- 3. Berry RB , Quan SF , Abreu AR , et al. for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine . The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. Version 2.6 . Darien, IL: : American Academy of Sleep Medicine; ; 2020. . [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rosenberg RS , Van Hout S . The American Academy of Sleep Medicine inter-scorer reliability program: respiratory events . J Clin Sleep Med. 2014. ; 10 ( 4 ): 447 – 454 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McGaghie WC , Issenberg SB , Barsuk JH , Wayne DB . A critical review of simulation-based mastery learning with translational outcomes . Med Educ. 2014. ; 48 ( 4 ): 375 – 385 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosenberg RS , Van Hout S . The American Academy of Sleep Medicine inter-scorer reliability program: sleep stage scoring . J Clin Sleep Med. 2013. ; 9 ( 1 ): 81 – 87 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Plante DT , Epstein LJ , Fields BG , Shelgikar AV , Rosen IM . Competency-based sleep medicine fellowships: addressing workforce needs and enhancing educational quality . J Clin Sleep Med. 2020. ; 16 ( 1 ): 137 – 141 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McGaghie WC , Siddall VJ , Mazmanian PE , Myers J ; American College of Chest Physicians Health and Science Policy Committee . Lessons for continuing medical education from simulation research in undergraduate and graduate medical education: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Educational Guidelines . Chest. 2009. ; 135 ( 3, Suppl ): 62S – 68S . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marinopoulos SS , Dorman T , Ratanawongsa N , et al . Effectiveness of continuing medical education . Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2007. Jan(149) : 1 – 69 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McGaghie WC , Harris IB . Learning theory foundations of simulation-based mastery learning . Simul Healthc. 2018. 13 ( 3S , Suppl 1 ): S15 – S20 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McGaghie WC , Issenberg SB , Cohen ER , Barsuk JH , Wayne DB . Does simulation-based medical education with deliberate practice yield better results than traditional clinical education? A meta-analytic comparative review of the evidence . Acad Med. 2011. ; 86 ( 6 ): 706 – 711 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Internal Medicine . The Sleep Medicine Milestones Project. January 2015. . https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/PDFs/Milestones/InternalMedicineSubspecialtyMilestones.pdf .

- 13. AASM . Facility Standards for Accreditation. August 2020. ; https://aasm.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/AASM-Facility-Standards-for-Accreditation-8.2020.pdf .