Abstract

Purpose of review:

Amyloid beta (Aβ) plaque accumulation is a hallmark pathology contributing to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and is widely hypothesized to lead to cognitive decline. Decades of research into anti-Aβ immunotherapies provide evidence for increased Aβ clearance from the brain, however this is frequently accompanied by complicated vascular deficits. This article reviews the history of anti-Aβ immunotherapies, clinical findings, and provides recommendations moving forward.

Recent findings:

In 20 years of both animal and human studies, anti-Aβ immunotherapies have been a prevalent avenue of reducing hallmark Aβ plaques. In both models and with different anti-Aβ antibody designs, amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) indicating severe cerebrovascular compromise have been common and concerning occurrence.

Summary:

ARIA caused by anti-Aβ immunotherapy has been noted since the early 2000’s and the mechanisms driving it are still unknown. Recent approval of aducanumab comes with renewed urgency to consider vascular deficits caused by anti-Aβ immunotherapy.

Keywords: Vascular, Alzheimer’s disease, aducanumab, amyloid, immunotherapy, biomarkers

Introduction

The accelerated approval of aducanumab under the FDA in June 2021 as an anti-Aβ immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has reinvigorated the field to understand if a reduction in amyloid burden in the brain results in cognitive changes in humans, and further, what causes the detrimental side effects known as amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIA). Decades of anti-Aβ immunotherapy research has resulted in a clear dichotomy of researchers and clinicians that support or oppose the use of these drugs. This review will detail both the findings that paved the way for anti-Aβ immunotherapies in trials today and evaluate key considerations moving forward.

Preclinical history of Aβ-immunotherapy research

Nuances and characterization of the Aβ peptide

Methods to remove Aβ from the brain have been investigated for over 20 years. While amyloid plaques were identified and described by Dr. Alois Alzheimer in 1906, it was the association of the mutation in amyloid precursor protein, APP, which relayed an autosomal dominant mode of AD inheritance that led to the later ‘amyloid cascade hypothesis’ [1-4]. Experiments starting in the mid-90s began to parse out the characteristics of the Aβ peptide that led to it being the hallmark pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Early studies revealed that N-terminal deletions resulted in the formation of Aβ into β-pleated sheets and showed increased aggregation [5]. Additionally, Iwatsubo et al. identified the Aβ peptide’s solubility as a key determinant in pathological toxicity, highlighting that the C-terminus of Aβ is hydrophobic, and longer C-termini (Aβ42) results in more, and earlier Aβ deposition in the brain versus shorter isoforms [6]. Today we understand this to be the insoluble Aβ1-42 peptide which is the primary form of deposited plaques while Aβ1-40 is found around the vasculature in cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) pathology [7, 8].

Mechanisms to clear Aβ

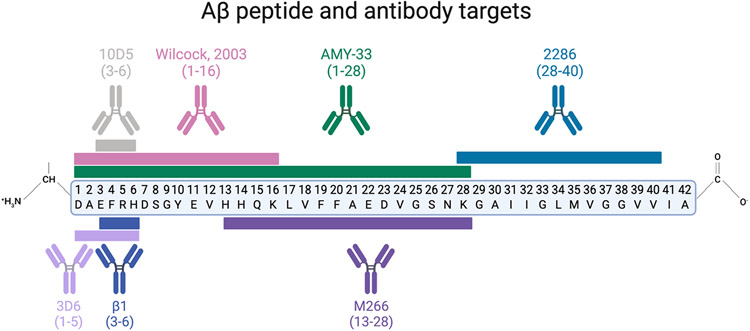

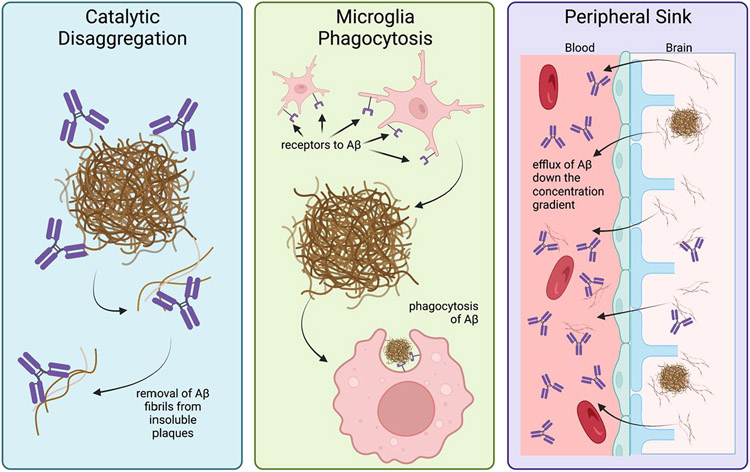

Studies examining mechanisms of aggregation of Aβ found that a site-directed antibody targeting the N-terminus (Aβ1-28), named AMY-33, resulted in the blockage of β-sheet formation of Aβ plaques and led to the idea that there are ‘aggregation epitopes’ within the Aβ peptide chain that disrupt aggregation (Figure 1) [9]. In 1997, Solomon and colleagues published work describing that anti-Aβ monoclonal antibodies bind and revert Aβ aggregates back to non-toxic forms in vitro [10]. These findings led to the first mechanistic hypothesis in 1997: catalytic disaggregation, or the usage of antibodies to block the aggregation of Aβ into fibrils and oligomers [10].

Figure 1:

Anti-Aβ antibodies tested for immunotherapy efficacy targeting various residues of the Aβ peptide

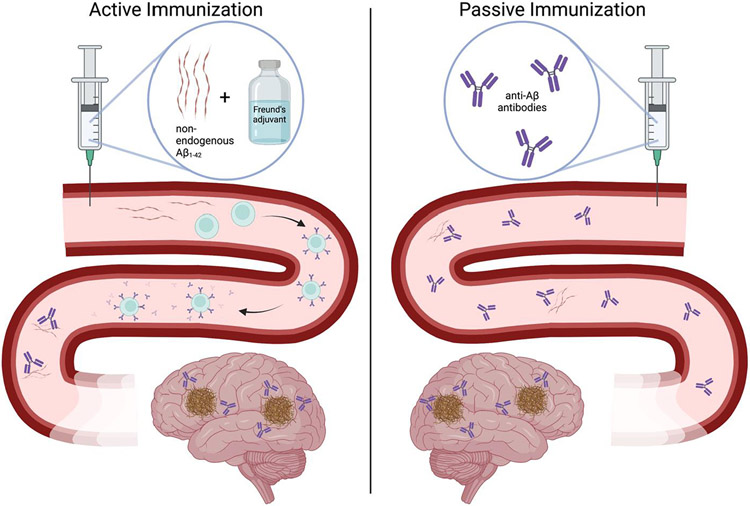

These experiments, led by Dr. Beka Solomon and team, highlighted the early mechanisms of antibody targeting of Aβ; however, the idea for utilization of antibody immunotherapy targeting Aβ for Alzheimer’s disease came about in 1999 [11]. Active immunization was the first approach used to develop antibodies targeting Aβ for a reduction in amyloid plaque pathology. Active immunization involves an injection of the protein of interest combined with an adjuvant to elicit a more intense immune response (Figure 2). This active immunization approach relies on the body’s adaptive immune system to create antibodies, in this case, antibodies against the Aβ peptide.

Figure 2:

Active vs. Passive Immunization.

In the amyloidogenic PDAPP transgenic mouse model, Schenk et al. showed the prevention of Aβ plaque formation, diminished neuritic plaques, and a marked reduction in astrogliosis in PDAPP mice after 11 months of active Aβ1-42 immunization using Freund’s adjuvant [11], with immunizations starting prior to amyloid deposition (starting at 6 weeks).These findings suggested that active immunization with Aβ1-42 could be a preventative measure to mitigate hallmark AD pathology later in life. Others utilized the active immunization paradigm of Aβ1-42 and Freund’s adjuvant on different amyloidogenic mouse models such as the transgenic TgCRND8 and APP/PS1 (a cross between Tg2576 and PS1(M146L) strains), and showed improved cognition across amyloidogenic mutations [12, 13]. In Morgan et al., active immunizations began at 7.5mo in the APP/PS1 strain, with radial arm water maze (RAWM) cognitive assessments at baseline (6mo), 4mo into treatment (11.5mo- 5 inoculations) and 8mo after treatment (15.5mo – 9 inoculations). No cognitive benefits of the active Aβ and Freund’s adjuvant were seen 4mo into treatment, however cognitive benefit was seen 8mo after treatment, with control injected transgenic mice showing significantly more errors in finding the hidden platform [12]. Similarly, in Janus et al., TgCRND8 transgenic mice were immunized with Aβ1-42 with Freund’s adjuvant at 6, 8, 12, 16, and 20 weeks old as the cognitive phenotype in this strain appears very early at 12 weeks of old [13, 14]. Unlike Morgan et al., Janus et al. performed the Morris water maze reference memory task at just over 1mo, 2mo, 3mo, and 4mo after first inoculation. Results revealed that the Aβ1-42 immunized transgenic mice remembered the platform location better than the control injected transgenic mice; however, memory wasn’t restored to the level of the non-transgenic littermate control mice [13]. These data suggested a partial reference memory restoration with Aβ1-42 active immunization. These pivotal in vivo studies began the quest to transform anti-Aβ antibodies into the curative immunotherapy for AD.

Passive Antibody Administration as a new method to target Aβ

While some scientists were examining active immunotherapeutic approaches, others tried passive vaccinations. Passive immunization is the administration of antibodies, in this case, anti-Aβ antibodies. This approach bypasses the adaptive immune system to create antibodies; however, since the immunity is coming from an external source, upkeep (usually repeated inoculations) is needed to maintain antibody titers in the body (Figure 2). In 2000, it was established that peripheral administration of N-terminus Aβ targeting antibodies (10D5 and 3D6, Figure 1) can cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) and decorate existing Aβ plaques in the PDAPP mouse brain [15]. Due to the BBB’s selective permeability, experiments confirming anti-Aβ antibody decorated plaques in the cerebral cortex were critical for peripheral administration as a potential immunotherapeutic avenue.

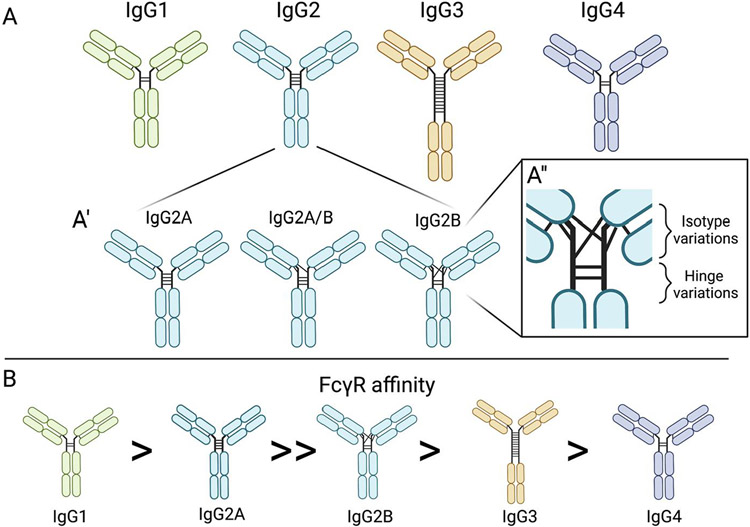

Further, Bard et al. published evidence of a second mechanism by which anti-Aβ antibodies can reduce Aβ plaque load: microglia mediated phagocytosis. This method was observed through immunofluorescence of Aβ inside microglia, followed by ex vivo experiments showing anti-Aβ antibody specific microglial activation [15]. In order to validate this was not due to the resultant immune response to the IgG-based antibody, others performed research into different antibody IgG backbones, characterized by varying hinge joins and disulfide bonding patterns, providing similar results (Figure 3) [16, 17]. Bacskai et al. showed that an equivalent microglial response occurs after three days of topical brain treatment of anti-Aβ antibodies with both IgG1 and IgG2b backbones, as seen in the 10D5 (targeting Aβ3-6) and 3D6 (targeting Aβ1-5) antibodies, respectively (Figures 1 and 3) [18]. Both the IgG1 and IgG2b backbones cleared Aβ plaques, suggesting that although the two IgGs trigger different inflammatory machinery (i.e. IgG1 does not stimulate the endogenous complement cascade), there may be multiple mechanisms resulting in Aβ clearance (Figure 3) [18-20]. Wilcock et al. confirmed the triggering of microglial activation due to anti-Aβ antibody targeting Aβ1-16 in 2003; and further teased out a time dependence component of microglial Aβ clearance, showing no microglial activation within 24 hours after intracranial antibody injection, suggesting other microglia independent mechanisms responding to the anti-Aβ antibody [21]. This biphasic clearance indicates that other cells may respond more immediately. These two groups also independently showed that Aβ F(ab’) fragments (Aβ antibodies lacking the Fc portion) were unable to trigger the same microglial response, yet resulted in similar clearance of diffuse Aβ plaques, but not compact Aβ plaques, when compared to the complete antibodies [18, 22].

Figure 3:

IgG isotypes, isomers, and FcγR affinities. (A) Four structures of IgG antibody subtypes characterized by variations in hinge disulfide bonds between the two heavy chains. (A’) Three of the IgG2 isomers characterized by the variations in heavy and light chain disulfide bonds. (A’’) Highlight of the regions where isotypes and hinges vary. (B) IgG isotypes identified by Fcγ receptor affinity.

While some were experimenting with microglia mediated clearance of Aβ, others looked towards different cell types. Before much of the aforementioned evidence for microglial phagocytosis of Aβ, DeWitt and colleagues showed in 1998 that astrocytes can mediate microglial phagocytosis [23]. In hypothesizing that microglia play a role in the removal of Aβ plaques, in particular the dense cores of Aβ plaques, they figured out that in vitro, microglia co-cultured with astrocytes reduce uptake of Aβ, suggesting astrocytes may slow microglial phagocytosis [23]. Another group showed that astrocytes actually retain the ability to degrade amyloid themselves [24]. In vitro astrocytes were shown to incorporate Aβ through recognizing and binding MCP-1, a chemokine found in Aβ plaques, and were also able to remove a significant amount of Aβ from the cell culture medium in 3 hours, with almost all Aβ1-42 peptide degraded by 48 hours [24]. Together, these results suggest that astrocyte-microglia crosstalk is critical in the targeting of Aβ plaques.

Concurrently, in 2001, monoclonal antibody, m266, directed at the central domain of the Aβ peptide (Aβ13-28, Figure 1) revealed that Aβ follows a concentration gradient [25]. As reported in an in vitro model of CSF dialysis and an in vivo PDAPP amyloidogenic transgenic mouse model, m266 sequestered CSF Aβ between compartments, altering the equilibrium and acting as an ‘Aβ sink’. This concept of peripheral anti-Aβ antibody administration causing an efflux of CNS Aβ to the periphery was further tested and confirmed, providing ample evidence for the peripheral sink hypothesis [26]. All three mechanisms of Aβ clearance described are depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4:

Three mechanisms of Aβ clearance

Evidence of anti-Aβ antibody induced vascular pathologies

As researchers focused on clearance mechanisms of Aβ, a significant adverse effect of anti-Aβ antibodies also became evident – cerebrovascular dysfunction. Such dysfunction was noted as early as 2002 in a short one page publication revealing that APP23 transgenic mice passively immunized with an anti-Aβ immunotherapy called β1, induced vascular compromise [27]. Starting with males at 21 months old, weekly peripheral injections for 5 months of antibody targeting Aβ3-6 (β1), resulted in persistent CAA and was accompanied by increased incidence of Perls’ Berlin Blue ferric iron pathology, indicating microhemorrhages [27]. Wilcock et al. confirmed this pathology in passively immunized ~19 month old Tg2576 derived mice, using a mouse monoclonal anti-human Aβ28-40 antibody called 2286, finding that indeed there was increased vascular Aβ load that corresponded with a reduction in parenchymal Aβ plaque load [28]. It was also noted that the number of microhemorrhages increased throughout the 5 months of anti-Aβ immunotherapy treatment, suggesting that the immunotherapy was either directly or indirectly disrupting cerebrovascular integrity [28]. In 2005, Racke et al substantiated these results, publishing that N-terminal directed 10D5 and 3D6 antibodies administered to PDAPP mice, both crossed the blood brain barrier, and bound CAA, while mid-Aβ targeting m266 did not bind CAA [29]. Additionally, they validated the results from Pfeifer et al., showing that 3D6 increased microhemorrhages associated with CAA in the 3D6 immunized mice. Together, these highlighted papers, alongside others at the time, spanning multiple mouse models and Aβ region targets, all urge that the anti-Aβ mediated clearance triggers a catastrophic breakdown of the blood brain barrier causing neurotoxic hemorrhages. While in the early 2000s, microhemorrhages were not well understood in AD cases specifically, we know now that microvascular pathology is a frequent occurrence in AD diagnosed individuals and vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID) are major contributors to clinical dementia [30, 31]. Though likely initiated by various pathways, it is clear these early observations noted cerebrovascular deficits, such as increased CAA and microhemorrhages, are exacerbated by anti-Aβ immunotherapy.

Clinical translation of Aβ-immunotherapy confirms cerebrovascular complications

AN-1792 – the first evidence of off target effects anti-Aβ immunotherapy in humans

The first human clinical trial, AN-1792, used an active immunization approach. Detailed in a publication by Schenk et al in 2002, AN-1792 was terminated in Phase IIa due to off target effects, namely 6% of patients showed signs of meningoencephalitis [32]. Scientists believed that this result was due to an overactive T-cell proinflammatory response to the Aβ1-42 peptide [33, 34]. After detecting meningoencephalitis by MRI and markers of increased inflammation in the CNS, the trial was halted. It was later shown through autopsy results of several AN-1792 participants, that while Aβ plaque load was greatly reduced, there was evidence of: 1) persistent CAA in areas devoid of parenchymal Aβ plaques, 2) diffuse abnormalities on MRI scans localized to reduced white matter, and 3) persistent microglial Aβ phagocytosis, as well as many other findings [35, 36]. Follow up studies of more patients focused on the cerebrovascular outcomes, showing that immunized patients had between 7 and 14 times as many vascular deposits in the leptomeninges and cortex, despite lowering parenchymal Aβ [37]. Interestingly, in addition to microhemorrhages, there was evidence of both Aβ40 and Aβ42 at the vascular wall, in contrast to naturally occurring CAA that is predominantly the Aβ40 species. These findings support the hypothesis that AN-1792 caused reduction of parenchymal Aβ plaques, and that one method of Aβ removal is hypothesized to be through the cerebrovasculature.

Bapineuzumab – solidification of vascular adverse events

Despite the adverse events halting the AN-1792 trial, researchers, clinicians, and patients maintained hope for the anti-Aβ antibody immunotherapy approach. To avoid the hypothesized T-cell response that halted the AN-1792 trial passive immunotherapy was utilized. The first of such agents to be tested in clinical trials was an antibody targeting only the N-terminus called bapineuzumab. A murine monoclonal antibody sharing the target epitope of bapineuzumab called 3D6 showed efficient Aβ plaque clearance in various amyloidogenic mouse models, paving the way for clinical trials. Starting in 2005, a phase II study testing safety and tolerability of bapineuzumab resulted in no significant differences in the primary efficacy outcomes of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) and the Disability Assessment for Dementia (DAD) assessment in the four doses tested versus the placebo [38]. The report highlights the incidence of vasogenic edema on MRI in 12/124 patients in the bapineuzumab cohort (Table 1). The study also detailed that the MRI detected vasogenic edema was more pronounced in APOEε4 carriers, suggesting APOE genotype may interact with bapineuzumab. Despite the lack of statistical significance in the primary outcomes, progress to phase III trials was not hindered. Additionally, this trial necessitated further study of APOE and immunotherapy interactions.

Table 1:

Reported ARIA incidence for Bapineuzemab, Aducanumab, Donanemab, and Lecanemab in APOEε4 carriers and non-carriers. ARIA incidences above 10% in the patient population are highlighted in red.

| Antibody name | Characteristics | Dosage | ARIA incidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOEε4 carriers | APOEε4 non-carriers | |||

| % affected | % affected | |||

| Bapineuzumab | N-terminal Aβ antibody | 0.5mg/kg | 15.30% | 4.20% |

| 1.0mg/kg | NA | 9.40% | ||

| 2.0mg/kg | NA | 14.20% | ||

| Placebo | 0.20% | 0.20% | ||

| Aducanumab | N-terminal Aβ antibody | 3mg/kg | 30% | NA |

| 6mg/kg | 38% | 18% | ||

| 10mg/kg | 43% | 20% | ||

| Placebo | 2% | 4% | ||

| Donanemab | AβpE3 (pyroglutamate-Aβ) | 20mg/kg | 35% | 11% |

| Placebo | 1% | 0% | ||

| Lecanemab | Soluble Aβ | 2.5mg/kg (biweekly) | 3% | 0% |

| 5mg/kg (monthly) | 3% | 0% | ||

| 5mg/kg (biweekly) | 4% | 0% | ||

| 10mg/kg (monthly) | 10% | 7% | ||

| 10mg/kg (biweekly) | 14% | 8% | ||

| Placebo | 1% | 0% | ||

In 2007, phase III studies for bapineuzumab administration over 18 months were started in the United States and Canada with patient populations stratified by APOEε4 genotype. With studies split into APOEε4 carriers (Study 302: NCT00575055) and non-carriers (Study 301: NCT00574132) in mild to moderate cases of AD, two clinical trials sought to evaluate changes in cognitive and functional outcomes. These clinical trials were started in parallel to evaluate long term safety and efficacy. In 2008, two more similarly designed clinical trials started with APOEε4 carriers (Study 3001: NCT00676143) and APOEε4 non-carriers (Study 3000: NCT00667810), however these had global representation. These global trials were aborted in 2012 when futility analyses showed no significant benefits in studies 301 and 302. While PIB-PET scan was only performed on a small subset of trial 301 and 302 participants, evidence from these scans suggested bapineuzumab attenuated Aβ plaque deposition in immunized APOEε4 carriers, but the effects did not translate to cognitive benefits [39]. The primary adverse event in the 301 and 302 trials was amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with edema diagnosed by MRI scans (Table 1)[39]. Although the trial remained unfinished, amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with edema were also the more frequent adverse event in the 3000 and 3001 global study [40].

Other antibody safety studies reported similar results [41, 42]. Eli Lilly’s solanezumab, another anti-Aβ immunotherapy passing through similar clinical trials at the time, showed no evidence of vasogenic edema or microhemorrhages that were seen with bapineuzumab [43]. This could be due to the central Aβ epitope targets, ultimately causing the antibody to target soluble and monomeric Aβ. Although solanezumab did not present with the same vascular deficits as bapineuzumab, it missed clinical endpoints in phase III trials and was also discontinued.

In 2010, before termination of bapineuzumab and solanezumab trials, an FDA sponsored roundtable workgroup coined the vascular pathologies seen in anti-Aβ antibody immunotherapy studies as amyloid related imaging abnormalities, or ARIA (Table 1) [44]. The cerebrovascular response manifesting as ‘vasogenic edema’ and ‘microhemorrhages’ seen in MRI scans of immunized patients were then termed ARIA-E and ARIA-H, respectively. This review panel weighed and established the frequent occurrence of the adverse effects seen in preclinical and ongoing trials and noted these terms are not limited to only two vascular pathologies but a spectrum of cerebrovascular dysfunctions. Although researchers did not know the cause of ARIA due to anti-Aβ antibody immunotherapy, this report led future clinical trials to require frequent MRI scans to detect ARIA and withdraw treatment, allowing ARIA to resolve, often with the cessation of anti-Aβ antibody treatment.

Aducanumab – First AD modifying treatment approved

Aducanumab by Biogen was the first disease modifying treatment approved for AD [45]. While all other anti-Aβ drugs have failed to meet primary endpoints in their clinical trials, two of which are mentioned prior, aducanumab was granted ‘accelerated approval’ from the FDA on June 7th, 2021. Aducanumab, an IgG1 backboned antibody targeting residues 3-7 of the Aβ peptide, was derived from B-cells of healthy aged humans. Libraries of aged healthy human B-cells were tested for binding and reactivity to aggregated Aβ [46]. Aducanumab was developed from this initial screen, creating an antibody that would target only amalgamated Aβ, thus sparring monomeric Aβ. It was clear at this point in the late 2000’s that N-terminus anti-Aβ showed Aβ removal properties when transgenic mice were immunized, of which, aducanumab showed this same promise in mouse models [47]. A phase Ib clinical trial consisting of 165 participants, called PRIME, examined a placebo-based control against a fixed dose of 1mg/kg, 3mg/kg, 6mg/kg, and 10mg/kg intravenously administered aducanumab monthly for a year. Interim results from PRIME’s (NCT01677572) secondary measures revealed many positive outcomes. There was evidence of significantly reduced Aβ in the brain as assessed by florbetapir-PET scans after 3, 6, and 10mg/kg administration of aducanumab after one year, and lower CDR and MMSE changes in the high 10mg/kg dosing group after a year, suggesting preserved cognition [47]. The main adverse effect noted in the PRIME trial was ARIA, occurring more frequently in a dose dependent manner (Table 1) [47]. In August 2015, two identical phase III studies, EMERGE (NCT02484547) and ENGAGE (NCT0247780) were sponsored globally in approximately 3,200 total patients with MCI or mild dementia or positive Aβ PET scans, to test the efficacy and safety of aducanumab. Using a three arm 1:1:1 approach to evaluating the effect of a low, high, and placebo dose of aducanumab, participants were administered intravenous infusions monthly for 76 weeks. Importantly, participants were stratified based on APOEε4 carriage, with APOEε4 carriers receiving lower doses than non-carriers. The primary outcome tested was whether aducanumab was successful in reducing cognitive impairment due to AD in the form of CDR-SOB. This cognitive test is based on interviews with the patient and informant (participant’s primary caregiver), assessing memory, orientation, problem solving, community affairs, hobby engagement, and self-care [48]. Interim analyses for these clinical trials ascertained that while EMERGE was ‘trending positive’, ENGAGE did not appear to meet the primary endpoints. There were multiple disconcerting differences between the two identically designed studies, prompting questions about factors not due to natural variation [49]. For example, though the dosages were the same, there was a greater reduction in Aβ plaques detected by PET imaging, in the EMERGE trial than the ENGAGE trial in the patients receiving high dose of aducanumab, which was partially address in the FDA prepared package for approval [46, 49, 50]. In March 2019, the trials were terminated due to futility. Seven months later, re-analysis with the addition of data acquired after the interim checkpoint showed positive results, prompting Biogen to pursue regulatory approval of aducanumab [49]. Concerning subsequent analysis showed aducanumab-induced ARIA-E and ARIA-H in a high percentage of both APOEε4 carrier and non-carrier populations in a dose dependent manner (Table 1).

Moving forward - Important vascular considerations

Aducanumab – stratification of the patient population

Aducanumab passed a great milestone as the first FDA approved drug to modify one of the hallmark AD pathologies hypothesized to contribute to cognitive decline. With this, much scrutiny also arose, citing non-replicated results (between EMERGE and ENGAGE), bias in post-hoc statistical analysis, and inability to claim efficiency [45]. Regardless of one’s stance on the controversy that emerged from the approval of aducanumab, vascular consequences must be considered for anti-Aβ immunotherapy target populations and clinical trial designs moving forward. From the earliest studies in transgenic mice, to two halted phase III clinical trials, the cerebrovascular damage due to several anti-Aβ antibodies shows extreme consistency and requires immediate concern.

To address this, the dosage design for EMERGE and ENGAGE stratified participants based on APOEε4 genotype status [50]. Due to the numerous studies showing APOEε4 carriers are more susceptible to both ARIA-E and ARIA-H after anti-Aβ immunotherapy, Biogen separated APOEε4 carriers, who went on to receive a ‘lower’ dose, titrating to 3mg/kg, rather than the originally designed ‘low’ dose at 6mg/kg[50]. Across both EMERGE and ENGAGE, approximately 65% of participants were APOEε4+, creating not a subset of the population but a newfound group being tested. Results stating ‘low dose’ versus ‘high dose’ have approximately equal percentages of APOEε4 positive participants; however, the dosing regimen referred to is not the same. While it was wise to subset the ARIA-susceptible APOEε4 carriers from the more resistant APOEε4 non-carriers, clearly delineating the groups in analysis and future reports is critical and responsible. Further, it is of the utmost importance to understand how APOEε4 creates a more-ARIA-susceptible environment for drug administration using anti-Aβ immunotherapy to continue. Examinations of the APOEε4 heterozygous status versus the APOEε4 homozygous status need to be investigated as well.

Biomarkers

The major attempt to combat ARIA in clinical trials is the inclusion of multiple MRI scans throughout treatment. In 2011, as ARIA was first identified as a reoccurring adverse event in these anti-Aβ clinical trials, a roundtable workgroup consisting of both academics and industry representatives responded by defining ARIA-E and ARIA-H, detailing posited risk factors for ARIA, as well as providing several recommendations on the standardization, frequency, and interpretation of MRI scans in trial design [44]. The published comments ended with an emphasis on investigating the mechanisms by which anti-Aβ immunotherapy induces ARIA, using both animal models and future human clinical trials. More recently, the “Aducanumab: Appropriate Use Recommendations” and “Aducanumab: Appropriate Use Recommendations Update” written by experts in AD research, clinical trials, drug development, and patient care, also focuses on improving clinical biomarkers through the use of MRI scans to mitigate potential adverse effects of aducanumab [51, 52].

In addition to MRI, clinical studies sought to use CSF-based biomarkers to determine target engagement and efficacy of the anti-Aβ immunotherapy. In ENGAGE and EMERGE, participant samples of CSF were tested for Aβ42, total-Tau, and p-Tau. However, multiple other CSF and plasma biomarkers have been shown to be extremely efficient in characterizing cerebrovascular dysfunction. Adding vascular biomarkers to these CSF panels, as well as including plasma draws at patient visits during clinical trials would greatly improve diagnostic research and identify participants that may be active in early stages of anti-Aβ induced vascular deficits that lead to ARIA. Markers such as MMP9, VEGF, PlGF, and CSF to plasma albumin ratio are a few examples of sensitive biomarkers that can indicate ongoing vascular damage.

The combinatorial use of plasma, CSF, and imaging biomarkers can help future studies stratify participants. While this might seem counter-intuitive, it has been widely established that there are multiple etiologies of dementia, and this is also true within AD itself. The first sub-classification of AD has already occurred- when research supported and outlined differences between genetically driven early-onset AD (EOAD) and the genetic and environmental factors contributing to sporadic late-onset AD (LOAD). Unfortunately, even within these subgroups there are further differences as research investigates the early and ongoing pathologies of community and clinical based cohorts. In these cases, using plasma and CSF protein biomarkers to establish subgroups of vascular-event susceptible AD participants may be advisable in future clinical trials. This comes in addition to using these less invasive tools to help identify potential adverse effects of anti-Aβ immunotherapy in the clinical follow ups – helping to paint a more complete prognostic picture of those that may be falling ill to ARIA and vascular dysfunction.

Research recommendations

Evaluate plasma and CSF biomarkers that can further stratify participant populations that may be at risk for vascular complications due to anti-Aβ immunotherapy

Fund and emphasize animal and human research into the mechanisms by which anti-Aβ immunotherapy contributes to ARIA

Research how ARIA evolves and resolves to better understand the precise mechanisms and cell types responsible for anti-Aβ induced vascular deficits

Conclusions

Since the early 1990’s, massive strides have been made in understanding the biophysics and biochemistry of the hallmark AD APP gene and Aβ peptide. There have been multiple attempts to reduce parenchymal Aβ plaques, with many techniques showing clear efficacy. However, vascular deficits also frequently accompany these approaches. Throughout murine studies and human clinical trials, vascular deficits resulting in ARIA, have been observed with anti-Aβ antibody immunization, one of the most utilized methods aimed to clear Aβ from the brain. Unfortunately, while targeting and removing Aβ from the brain appears feasible, ARIA incidence cannot be ignored. If there is any hope in mitigating adverse events due to the vascular deficits induced by anti-Aβ immunotherapy, research needs to focus on the causes and mechanisms by which ARIA arises and resolves to create a more feasible and safe functional disease modifying compound.

Footnotes

Funding and/or Conflicts of interests/Competing interests.

The authors do not have existing conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hippius H, Neundorfer G. The discovery of Alzheimer's disease. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2003;5(1):101–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goate A, Chartier-Harlin M-C, Mullan M, Brown J, Crawford F, Fidani L, et al. Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1991;349(6311):704–6. doi: 10.1038/349704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256(5054):184–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease: a central role for amyloid. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1994;53(5):438–47. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199409000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pike CJ, Overman MJ, Cotman CW. Amino-terminal Deletions Enhance Aggregation of β-Amyloid Peptides in Vitro. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(41):23895–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.23895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y. Visualization of A beta 42(43) and A beta 40 in senile plaques with end-specific A beta monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is A beta 42(43). Neuron. 1994;13(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niwa K, Carlson GA, Iadecola C. Exogenous Aβ1–40 Reproduces Cerebrovascular Alterations Resulting from Amyloid Precursor Protein Overexpression in Mice. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2000;20(12):1659–68. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomis M, Sobrino TS, Ois A, MilláN MN, RodríGuez-Campello A, De La Ossa NPR, et al. Plasma β-Amyloid 1-40 Is Associated With the Diffuse Small Vessel Disease Subtype. Stroke. 2009;40(10):3197–201. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.109.559641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon B, Koppel R, Hanan E, Katzav T. Monoclonal antibodies inhibit in vitro fibrillar aggregation of the Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1996;93(1):452–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon B, Koppel R, Frankel D, Hanan-Aharon E. Disaggregation of Alzheimer beta-amyloid by site-directed mAb. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(8):4109–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *11. Schenk D, Barbour R, Dunn W, Gordon G, Grajeda H, Guido T, et al. Immunization with amyloid-beta attenuates Alzheimer-disease-like pathology in the PDAPP mouse. Nature. 1999;400(6740):173–7. doi: 10.1038/22124. This paper is the first article showing effective immunization procedures to clear Aβ plaques in mice.

- 12.Morgan D, Diamond DM, Gottschall PE, Ugen KE, Dickey C, Hardy J, et al. Aβ peptide vaccination prevents memory loss in an animal model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2000;408(6815):982–5. doi: 10.1038/35050116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janus C, Pearson J, McLaurin J, Mathews PM, Jiang Y, Schmidt SD, et al. Aβ peptide immunization reduces behavioural impairment and plaques in a model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2000;408(6815):979–82. doi: 10.1038/35050110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chishti MA, Yang DS, Janus C, Phinney AL, Horne P, Pearson J, et al. Early-onset amyloid deposition and cognitive deficits in transgenic mice expressing a double mutant form of amyloid precursor protein 695. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(24):21562–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100710200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *15. Bard F, Cannon C, Barbour R, Burke RL, Games D, Grajeda H, et al. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid beta-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2000;6(8):916–9. doi: 10.1038/78682. The authors show the first murine demonstration that peripheral immunization of anti-Aβ antibodies can cross the cerebrovasculature to mitigate Aβ plaque.

- 16.Vidarsson G, Dekkers G, Rispens T. IgG subclasses and allotypes: from structure to effector functions. Front Immunol. 2014;5:520. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Taeye SW, Rispens T, Vidarsson G. The Ligands for Human IgG and Their Effector Functions. Antibodies. 2019;8(2):30. doi: 10.3390/antib8020030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bacskai BJ, Kajdasz ST, McLellan ME, Games D, Seubert P, Schenk D, et al. Non-Fc-mediated mechanisms are involved in clearance of amyloid-beta in vivo by immunotherapy. J Neurosci. 2002;22(18):7873–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bard F, Barbour R, Cannon C, Carretto R, Fox M, Games D, et al. Epitope and isotype specificities of antibodies to β-amyloid peptide for protection against Alzheimer's disease-like neuropathology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100(4):2023–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0436286100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lightle S, Aykent S, Lacher N, Mitaksov V, Wells K, Zobel J, et al. Mutations within a human IgG2 antibody form distinct and homogeneous disulfide isomers but do not affect Fc gamma receptor or C1q binding. Protein Science. 2010;19(4):753–62. doi: 10.1002/pro.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilcock DM, DiCarlo G, Henderson D, Jackson J, Clarke K, Ugen KE, et al. Intracranially administered anti-Abeta antibodies reduce beta-amyloid deposition by mechanisms both independent of and associated with microglial activation. J Neurosci. 2003;23(9):3745–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilcock DM, Munireddy SK, Rosenthal A, Ugen KE, Gordon MN, Morgan D. Microglial activation facilitates Abeta plaque removal following intracranial anti-Abeta antibody administration. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15(1):11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeWitt DA, Perry G, Cohen M, Doller C, Silver J. Astrocytes regulate microglial phagocytosis of senile plaque cores of Alzheimer's disease. Exp Neurol. 1998;149(2):329–40. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wyss-Coray T, Loike JD, Brionne TC, Lu E, Anankov R, Yan F, et al. Adult mouse astrocytes degrade amyloid-beta in vitro and in situ. Nat Med. 2003;9(4):453–7. doi: 10.1038/nm838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeMattos RB, Bales KR, Cummins DJ, Dodart JC, Paul SM, Holtzman DM. Peripheral anti-A beta antibody alters CNS and plasma A beta clearance and decreases brain A beta burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(15):8850–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151261398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeMattos RB, Bales KR, Cummins DJ, Paul SM, Holtzman DM. Brain to plasma amyloid-beta efflux: a measure of brain amyloid burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Science. 2002;295(5563):2264–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1067568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfeifer M, Boncristiano S, Bondolfi L, Stalder A, Deller T, Staufenbiel M, et al. Cerebral hemorrhage after passive anti-Abeta immunotherapy. Science. 2002;298(5597):1379. doi: 10.1126/science.1078259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilcock DM, Rojiani A, Rosenthal A, Subbarao S, Freeman MJ, Gordon MN, et al. Passive immunotherapy against Abeta in aged APP-transgenic mice reverses cognitive deficits and depletes parenchymal amyloid deposits in spite of increased vascular amyloid and microhemorrhage. J Neuroinflammation. 2004;1(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Racke MM, Boone LI, Hepburn DL, Parsadainian M, Bryan MT, Ness DK, et al. Exacerbation of cerebral amyloid angiopathy-associated microhemorrhage in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice by immunotherapy is dependent on antibody recognition of deposited forms of amyloid beta. J Neurosci. 2005;25(3):629–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4337-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jellinger KA. Alzheimer disease and cerebrovascular pathology: an update. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2002;109(5–6):813–36. doi: 10.1007/s007020200068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janota C, Lemere CA, Brito MA. Dissecting the Contribution of Vascular Alterations and Aging to Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecular Neurobiology. 2016;53(6):3793–811. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schenk D Amyloid-β immunotherapy for Alzheimer's disease: the end of the beginning. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3(10):824–8. doi: 10.1038/nrn938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buckwalter MS, Coleman BS, Buttini M, Barbour R, Schenk D, Games D, et al. Increased T Cell Recruitment to the CNS after Amyloid beta1-42 Immunization in Alzheimer's Mice Overproducing Transforming Growth Factor-beta1. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(44):11437–41. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2436-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrer I, Rovira MB, Guerra MLS, Rey MJ, Costa-Jussá F. Neuropathology and Pathogenesis of Encephalitis following Amyloid β Immunization in Alzheimer's Disease. Brain Pathology. 2004;14(1):11–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicoll JAR, Wilkinson D, Holmes C, Steart P, Markham H, Weller RO. Neuropathology of human Alzheimer disease after immunization with amyloid-β peptide: a case report. Nature Medicine. 2003;9(4):448–52. doi: 10.1038/nm840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicoll JAR, Barton E, Boche D, Neal JW, Ferrer I, Thompson P, et al. Aβ Species Removal After Aβ42Immunization. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. 2006;65(11):1040–8. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000240466.10758.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boche D, Zotova E, Weller RO, Love S, Neal JW, Pickering RM, et al. Consequence of Abeta immunization on the vasculature of human Alzheimer's disease brain. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 12):3299–310. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salloway S, Sperling R, Gilman S, Fox NC, Blennow K, Raskind M, et al. A phase 2 multiple ascending dose trial of bapineuzumab in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73(24):2061–70. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0b013e3181c67808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salloway S, Sperling R, Fox NC, Blennow K, Klunk W, Raskind M, et al. Two Phase 3 Trials of Bapineuzumab in Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer's Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(4):322–33. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1304839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vandenberghe R, Rinne JO, Boada M, Katayama S, Scheltens P, Vellas B, et al. Bapineuzumab for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease in two global, randomized, phase 3 trials. Alzheimer's Research & Therapy. 2016;8(1). doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0189-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Black RS, Sperling RA, Safirstein B, Motter RN, Pallay A, Nichols A, et al. A Single Ascending Dose Study of Bapineuzumab in Patients With Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2010;24(2):198–203. doi: 10.1097/wad.0b013e3181c53b00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rinne JO, Brooks DJ, Rossor MN, Fox NC, Bullock R, Klunk WE, et al. 11C-PiB PET assessment of change in fibrillar amyloid-beta load in patients with Alzheimer's disease treated with bapineuzumab: a phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled, ascending-dose study. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(4):363–72. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doody RS, Thomas RG, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, et al. Phase 3 Trials of Solanezumab for Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer's Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(4):311–21. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1312889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sperling RA, Jack CR Jr., Black SE, Frosch MP, Greenberg SM, Hyman BT, et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in amyloid-modifying therapeutic trials: recommendations from the Alzheimer's Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(4):367–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tampi RR, Forester BP, Agronin M. Aducanumab: evidence from clinical trial data and controversies. Drugs in Context. 2021;10:1–9. doi: 10.7573/dic.2021-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Food and Drug Administration, Biogen. Peripheral and Central Nervous System (PCNS) Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sevigny J, Chiao P, Bussière T, Weinreb PH, Williams L, Maier M, et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2016;537(7618):50–6. doi: 10.1038/nature19323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khan TK. Chapter 2 - Clinical Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. In: Khan TK, editor. Biomarkers in Alzheimer's Disease. Academic Press; 2016. p. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- **49. Knopman DS, Jones DT, Greicius MD. Failure to demonstrate efficacy of aducanumab: An analysis of the EMERGE and ENGAGE trials as reported by Biogen, December 2019. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2021;17(4):696–701. doi: 10.1002/alz.12213. This paper outlines the timeline of clinical trials for aducanumab and FDA statements as well as highlights the areas where outcome measures fell short statistically and translationally. This subjective piece details the need for a third clinical trial since EMERGE and ENGAGE failed to provide evidence of efficacy.

- 50.Haeberlein SB, Von Hehn C, Tian Y, Chalkias S, Muralidharan KK, Chen T, et al. Emerge and Engage topline results: Phase 3 studies of aducanumab in early Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2020;16(S9). doi: 10.1002/alz.047259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cummings J, Aisen P, Apostolova LG, Atri A, Salloway S, Weiner M. Aducanumab: Appropriate Use Recommendations. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2021;8(4):398–410. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2021.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **52. Cummings J, Rabinovici GD, Atri A, Aisen P, Apostolova LG, Hendrix S, et al. Aducanumab: Appropriate Use Recommendations Update. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022;9(2):221–30. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2022.34. This article updates the appropriate use of aducanumab in the clinic. The authors outline the recommendations of patient population selection and clinical safety monitoring of ARIA events.