Abstract

We examined the formation of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte rosettes using parasite isolates from placental or peripheral blood of pregnant Malawian women and from peripheral blood of children. Five of 23 placental isolates, 23 of 38 maternal peripheral isolates, and 136 of 139 child peripheral isolates formed rosettes. Placental isolates formed fewer rosettes than maternal isolates (range, 0 to 7.5% versus 0 to 33.5%; P = 0.002), and both formed fewer rosettes than isolates cultured from children (range, 0 to 56%; P < 0.0001). Rosette formation is common in infections of children but uncommon in pregnancy and rarely detected in placental isolates.

Under in vitro conditions, Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes (P. falciparum-IE) may show rosette formation, the adherence of two or more uninfected erythrocytes to an erythrocyte containing a mature-stage parasite. Rosette formation has been associated with severity of malarial disease in young children in some studies (4, 10, 12, 15, 18, 20), but not all (1, 17), and has been proposed to contribute to microvascular obstruction in organs such as the brain (9). It was reported to be rare in isolates from pregnant Cameroonian women (11).

In regions of malaria endemicity, pregnant women are more susceptible to malaria infection than their nonpregnant counterparts (3). Placental malaria infection is clearly of major importance in the pathogenesis of malaria in pregnancy, with mature-stage IE frequently found in the placental intervillous spaces. Only a proportion of placental IE appear to be adherent to the syncytiotrophoblast (23, 24), and many of the erythrocytes in the intervillous spaces are uninfected. We postulated that placental accumulation of IE may result in part from rosette formation, which could lead to disturbances in blood flow (22). We therefore compared rosette formation by parasites cultured from peripheral blood of children and pregnant women with that of P. falciparum isolates obtained from placental blood at delivery.

Peripheral and placental blood samples were collected from pregnant women and peripheral blood was collected from children at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Blantyre, Malawi, after obtaining informed consent. Peripheral blood was processed and cultured as described previously, in medium supplemented with 10% human blood group AB serum (2). Placental blood was collected from the cut maternal surface of the placenta, diluted to 5% hematocrit in complete medium supplemented with 10% AB serum, and examined for rosetting after incubation at 37°C for a minimum of 60 min. Rosetting assays were performed by staining IE with acridine orange and by examination with combined light and fluorescence microscopy, as previously described (16). A rosette was defined as two or more uninfected erythrocytes adherent to an IE. Each isolate was tested in duplicate, and a minimum of either 200 trophozoite-containing IE or 100 high-power (40× objective) fields were examined, and samples with one or more rosettes identified were classed as rosetting isolates. Rosette formation is reported as a percentage of all trophozoite-containing IE in rosettes.

Pearson's χ2 test and the Kruskall-Wallis test were used to compare qualitative and quantitative variables, respectively, by using Stata version 5.0 (Stata Corp., College Park, Tex.). Ethical approval was obtained from the College of Medicine Research Committee, University of Malawi.

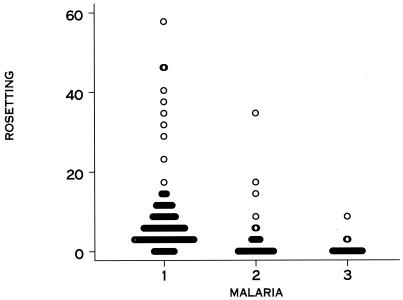

Twenty-three of 38 isolates cultured from the peripheral blood of pregnant women and 5 of 22 isolates from placental blood examined ex vivo formed rosettes, whereas 136 of 139 isolates from children examined over the same period formed rosettes (Table 1). The percent rosette formation (the percentage of IE from a given sample found to be in rosettes) was lower for placental blood isolates than for maternal peripheral blood isolates (P = 0.002) and lower for maternal peripheral or placental blood isolates than for isolates from children (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). The prevalence of rosetting isolates (proportion of isolates with any rosettes detected) was also significantly lower for placental blood isolates than for peripheral maternal blood isolates (P = 0.013) and for placental or peripheral maternal blood isolates than for isolates from children (P < 0.001). Prevalence and degree of rosette formation in pregnant women did not differ with age and gravidity, and isolates from women in the Antenatal Clinic or in labor showed similar rosetting characteristics (Table 1). For 12 women, we were able to compare rosetting by isolates from matched peripheral and placental blood. For 7 women, there were no rosettes in cultured peripheral or placental blood, and for 5 women, there was a low degree of rosetting (range, 0.25 to 3%) in peripheral blood but no rosetting in placental blood. This suggests that circulating parasites may comprise different populations, including some that sequester in the placenta and do not rosette and others that sequester elsewhere and form rosettes to some degree. Some isolates were also tested for adherence to purified receptors (2). Of 10 peripheral maternal blood isolates, 4 bound to chondroitin sulfate A (CSA) and 2 others bound to CD36; of 9 placental isolates, 7 bound to CSA and 1 also bound to CD36. In most instances parasites expressed functional adherence proteins on the IE surface but did not rosette.

TABLE 1.

Rosetting by isolates from pregnant women and children

| Isolate group | No. of isolates | Median (IQR) level of rosette formationa | No. (%) of rosetting isolates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placental | 23 | 0 (0–0) | 5 (21.8) |

| Maternal peripheral | 38 | 0.25 (0–4) | 23 (60.5) |

| Antenatal | 24 | 0.5 (0–4) | 15 (62.5) |

| In labor | 14 | 0.25 (0–3) | 8 (57.7) |

| Children | 139 | 5 (2.8–9.0) | 136 (99.2) |

Values are the percentages of IE in rosettes. IQR, interquartile range.

FIG. 1.

Rosette formation (%) by IE cultured from children's peripheral blood (1), cultured from maternal peripheral blood (2), or isolated from placental blood (3).

Lack of rosetting by placental isolates did not appear to be attributable to reversible inhibitors, such as antibodies, present in placental blood: in some instances, IE were washed repeatedly before incubation in culture medium, and in others, they were incubated in culture medium overnight, without changes in rosetting (data not shown). Some placental isolates were adapted to ongoing culture, yet rosetting levels did not change appreciably (data not shown).

Placental blood isolates differed from peripheral blood isolates in that they were not cultured. Culturing could result in the selection of subpopulations of parasites with different adhesive properties. However, our results suggest that the lack of rosetting in placental blood isolates is not a function of their different processing. Rosette formation (mostly at high [>20%] levels) has previously been noted in uncultured isolates from the peripheral blood of Thai adults with severe malaria whose circulating parasites included mature asexual stages (21).

Our findings suggest that rosetting is not important in the development of placental malaria, whereas it has been implicated in the pathogenesis of malaria disease in children (4, 16, 18). Our results are supported by the findings of Maubert et al., who examined parasites from the placentas of 23 Cameroonian women, none of whose parasites formed rosettes (11). In comparison, cryopreserved peripheral blood parasites (which may change phenotype after thawing [14]) from 1 of 12 women in labor and from 8 of 12 nonpregnant adults showed rosette formation. We could not test parasites from nonpregnant adults for rosetting, but children examined over the same period were almost always infected with rosetting parasites, and other studies suggest that P. falciparum rosetting is similar in adults and children (7, 8, 11, 15).

Placental infection may develop in part through adhesion to a ligand(s) such as CSA on the syncytiotrophoblast lining of the intervillous spaces, although not all isolates from pregnant women bind to CSA (2, 6). Our results suggest that parasites from the placenta have different adherence and antigenic characteristics from those infecting children (2). Both rosette formation and adhesion to CSA have been ascribed to P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (5, 13, 19). A possible explanation for the relative lack of rosetting in CSA binding parasites from pregnant women and the scarcity of CSA binding in isolates from children (17) would be that CSA binding and rosetting are mutually incompatible properties of parasitized erythrocytes. This possibility remains to be proven.

In conclusion, pregnant women are not commonly infected with parasites that form rosettes, and rosetting parasites are rarely found in the placenta, indicating that rosette formation is not a major factor in the pathogenesis of malarial infection of the placenta.

Acknowledgments

S.J.R. is the recipient of a Career Development Fellowship, and M.E.M. is the recipient of a Research Leave Fellowship in Clinical Tropical Medicine from the Wellcome Trust. J.G.B. was awarded an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Medical Postgraduate Scholarship and received generous support from the District 9680 Rotary Against Malaria Programme, Sydney, Australia.

We thank the staff of the Antenatal Clinic and Labour Ward of the Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Blantyre, Malawi, for friendly cooperation, and we thank all the women who participated. We are grateful for the enthusiastic support of V. Lema, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, College of Medicine, University of Malawi; Terrie Taylor, Michigan State University; and Graham Brown, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Yaman F, Genton B, Mokela D, Raiko A, Kati S, Rogerson S, Reeder J, Alpers M. Human cerebral malaria: lack of significant association between erythrocyte rosetting and disease severity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:55–58. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90658-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beeson J G, Brown G V, Molyneux M E, Mhango C, Dzinjalamala F, Rogerson S J. Plasmodium falciparum isolates from infected pregnant women and children are each associated with distinct adhesive and antigenic properties. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:464–472. doi: 10.1086/314899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brabin B J. An analysis of malaria in pregnancy in Africa. Bull W H O. 1983;61:1005–1016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson J, Helmby H, Hill A V S, Brewster D, Greenwood B M, Wahlgren M. Human cerebral malaria: association with erythrocyte rosetting and lack of anti-rosetting antibodies. Lancet. 1990;336:1457–1460. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93174-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Q, Barragan A, Fernandez V, Sundstrom A, Schlichtherle M, Sahlen A, Carlson J, Datta S, Wahlgren M. Identification of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) as the rosetting ligand of the malaria parasite P. falciparum. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fried M, Duffy P E. Adherence of Plasmodium falciparum to chondroitin sulfate A in the human placenta. Science. 1996;272:1502–1504. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5267.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Handunnetti S M, David P H, Perera K L, Mendis K N. Uninfected erythrocytes form “rosettes” around Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocytes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:115–118. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho M, Davis T, Silamut K, Bunnag D, White N J. Rosette formation of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes from patients with acute malaria. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2135–2139. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.2135-2139.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaul D K, Roth E, Jr, Nagel R L, Howard R J, Handunnetti S M. Rosetting of Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells with uninfected red blood cells enhances microvascular obstruction under flow conditions. Blood. 1991;78:812–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kun J F J, Schmidt-Ott R J, Lehman L G, Lell B, Luckner D, Greve R, Matousek P, Kremsner P G. Merozoite surface antigen 1 and 2 genotypes and rosetting of Plasmodium falciparum in severe and mild malaria in Lambarene, Gabon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:110–114. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(98)90979-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maubert B, Fievet N, Tami G, Boudin C, Deloron P. Plasmodium falciparum-isolates from Cameroonian pregnant women do not rosette. Parasite. 1998;5:281–283. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1998053281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newbold C I, Warn P, Black G, Berendt A, Craig A, Snow B, Msobo M, Peshu N, Marsh K. Receptor-specific adhesion and clinical disease in Plasmodium falciparum. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:389–398. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeder J C, Cowman A F, Davern K M, Beeson J G, Thompson J K, Rogerson S J, Brown G V. The adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to chondroitin sulfate A is mediated by PfEMP1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5198–5202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reeder J C, Rogerson S J, Al-Yaman F, Anders R F, Coppel R L, Novakovic S, Alpers M P, Brown G V. Diversity of agglutinating phenotype, cytoadherence and rosette-forming characteristics of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Papua New Guinean children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:45–55. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ringwald P, Peyron F, Lepers J P, Rabarison P, Rakotomalala C, Razanamparany M, Rabodonirina M, Roux J, Le Bras J. Parasite virulence factors during falciparum malaria: rosetting, cytoadherence, and modulation of cytoadherence by cytokines. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5198–5204. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5198-5204.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogerson S J, Chaiyaroj S C, Reeder J C, Al-Yaman F, Brown G V. Sulfated glycoconjugates as disrupters of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte rosettes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:198–203. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogerson S J, Tembenu R, Dobano C, Plitt S, Taylor T E, Molyneux M E. Cytoadherence characteristics of Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocytes from Malawian children with severe and uncomplicated malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:467–472. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowe A, Obeiro J, Newbold C I, Marsh K. Plasmodium falciparum rosetting is associated with malaria severity in Kenya. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2323–2326. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2323-2326.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowe J A, Moulds J M, Newbold C I, Miller L H. P. falciparum rosetting mediated by a parasite-variant erythrocyte membrane protein and complement-receptor 1. Nature (London) 1997;388:292–295. doi: 10.1038/40888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Treutiger C J, Hedlund I, Helmby H, Carlson J, Jepson A, Twumasi P, Kwiatkowski D, Greenwood B M, Wahlgren M. Rosette formation in Plasmodium falciparum isolates and anti-rosette activity of sera from Gambians with cerebral or uncomplicated malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46:503–510. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.46.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Udomsangpetch R, Pipitaporn B, Krishna S, Angus B, Pukrittayakmee S, Bates I, Suputtamongkol Y, Kyle D E, White N J. Antimalarial drugs reduce cytoadherence and rosetting of Plasmodium falciparum. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:691–698. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahlgren M, Fernandez V, Scholander C, Carlson J. Rosetting. Parasitol Today. 1994;10:73–79. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(94)90400-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walter P R, Garin Y, Blot P. Placental pathologic changes in malaria. A histologic and ultrastructural study. Am J Pathol. 1982;109:330–342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamada M, Steketee R, Abramowsky C, Kida M, Wirima J, Heymann D, Rabbege J, Breman J, Aikawa M. Plasmodium falciparum associated placental pathology: a light and electron microscopic and immunohistologic study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;41:161–168. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.41.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]