Hospitalisations due to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections largely decreased after social distancing measures were introduced to control the COVID-19 pandemic. Lifting these measures resulted in out-of-season RSV activity, sometimes exceeding the incidence of hospitalisations observed in regular seasons.1, 2, 3 Declining immunity due to reduced exposure to the virus may contribute to this altered epidemiology.1, 4, 5 Bardsley and colleagues1 showed that the combination of laboratory, clinical, and syndromic data capture the impact of RSV activity, yet did not provide insight into the proposed decline in immunity. To investigate this effect, we analysed sera of 558 randomly selected participants of a prospective nationwide study in the Netherlands for changes in IgG antibody concentrations to the RSV post-fusion F protein.6 Participants were 1–89 years of age (mean age 48 years [SD 20·7]). 236 (42·3%) were male; 245 (43·9%) were female; and 77 (13·8%) were other, missed the question, or did not disclose this information. Samples of the same people were collected in June, 2020 (timepoint 1, several months after the introduction of social restrictions), February, 2021 (timepoint 2, approximately 1 year after the end of the last typical RSV season), and June, 2021 (timepoint 3, the month when social restrictive measures were lifted in the Netherlands and the out-of-season RSV epidemic started; figure 1A ). Concentrations were log10 transformed for all statistical analyses. The repeated-measures general linear model (SPSS version 28; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to compare antibody concentrations between sampling timepoints of the same subjects and between age groups. p values, adjusted to Bonferroni and Benjamini-Hochberg procedures, are reported for timepoints and age-group differences respectively. Student's t test was used to compare the 2020 IgG concentrations of the people who showed at least a twofold increase in RSV-specific IgG from 2020 to 2021 (n=9) and those who did not (n=549).

Figure.

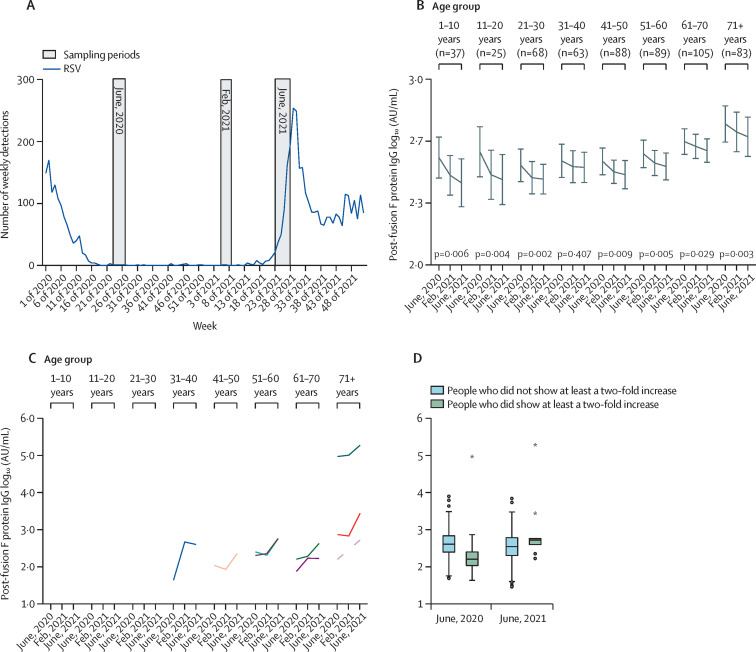

Changes in IgG concentrations to the post-fusion F protein from 2020 to 2021, relative to notification of RSV infections

(A) Weekly RSV surveillance by the Dutch Working Group for Clinical Virology of the Dutch Society for Medical Microbiology and National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (blue line), and sampling periods in June, 2020, February, 2021, and June, 2021 (in grey). (B) Median IgG concentrations in the different age groups of all 558 individuals. General linear models for repeated measurements were used on log10-transformed data to test the decay of antibodies over time (p<0·001), for all age groups except age 31–40 years, and differences between age groups (p<0·001). (C) Individuals (n=9) showing at least a twofold increase in RSV-specific IgG from 2020 to 2021. Each of the individuals that showed at least a twofold increase are represented by a different coloured line. (D) Stratification of people showing at least a twofold increase in IgG, which is indicative of exposure to the virus, and those who did not. The difference in antibody concentrations between the two groups in 2020 was assessed with student's t test on log10-transformed concentrations. The boxplot shows medians and quartiles. AU=arbitrary units. RSV=respiratory syncytial virus. *Outliers.

Post-fusion F IgG antibody concentrations declined from 2020 to 2021 (p<0·001) and increased with age (p<0·001; figure 1B). The decrease was greatest for the 1-year interval between timepoints 1 and 3 (p<0·001) when compared with the decrease between timepoints 1 and 2 (p<0·001) and between timepoints 2 and 3 (p=0·182). The decrease in antibodies was significant in all age groups, except for participants aged 31–40 years. Across the 3 timepoints, the age group of 71 years and older had higher antibody concentrations than participants aged 1–10 years (p=0·019), 21–30 years (p<0·001), 31–40 years (p=0·021), 41–50 years (p<0·001), and 51–60 years (p=0·034). In our analysis, we did not find evidence of differences in decay rates between age groups. We found 9 individuals (1·6%) with antibody boosting of at least two-fold during this period, indicative of exposure to the virus (figure 1C). These individuals were all adults of at least 30 years of age, and since two adults showed elevated IgG before the increase in clinical reports of RSV infections, these findings might indicate that circulation initiated in the adult population. On average, these individuals had lower IgG concentrations in 2020 (p=0·028) than those not showing a rise in IgG concentrations (figure 1D).

These data support the assumption that RSV-specific antibody concentrations declined during the COVID-19 pandemic in all age groups and are in line with a previous report showing decay of antibodies to RSV.5 We do not have data on RSV-specific antibody kinetics in our cohort before the pandemic and there are relatively large variations between individuals, so the effect on susceptibility to RSV is not clear yet. Antibodies to the F protein, especially in pre-fusion confirmation, have an important role in the neutralisation of RSV and were previously shown to correlate well with virus neutralisation.7 However, the degree to which virus neutralisation is affected and the exact correlation with immune protection are yet to be determined.8 Following this preliminary analysis, additional timepoints, including follow-up samples, are being investigated to support and extend these findings. In conclusion, monitoring changes in antibody concentrations could identify populations susceptible to RSV infection.

The study was funded by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sports. The funder had no role in the generation of the data or writing of the manuscript. ACT received funds from the Respiratory Syncytial Virus Consortium in Europe and Preparing for RSV Immunisation and Surveillance in Europe consortium for grants and travel costs. All other authors declare no competing interests. We thank all study participants, the Dutch Working Group on Clinical Virology from the Dutch Society for Clinical Microbiology, and all participating laboratories for providing the virological data from the weekly laboratory virological report.

References

- 1.Bardsley M, Morbey RA, Hughes HE, et al. Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in England during the COVID-19 pandemic, measured by laboratory, clinical, and syndromic surveillance: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00525-4. published online Sept 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delestrain C, Danis K, Hau I, et al. Impact of COVID-19 social distancing on viral infection in France: a delayed outbreak of RSV. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56:3669–3673. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eden J-S, Sikazwe C, Xie R, et al. Off-season RSV epidemics in Australia after easing of COVID-19 restrictions. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2884. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30485-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Billard M-N, Bont LJ. Quantifying the RSV immunity debt following COVID-19: a public health matter. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00544-8. published online Sept 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reicherz F, Xu RY, Abu-Raya B, et al. Waning Immunity against respiratory syncytial virus during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Infect Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac192. published online May 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berbers G, Mollema L, van der Klis F, den Hartog G, Schepp R. Antibody responses to respiratory syncytial virus: a cross-sectional serosurveillance study in the Dutch population focusing on infants younger than 2 years. J Infect Dis. 2020;224:269–278. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schepp RM, de Haan CAM, Wilkins D, et al. Development and standardization of a high-throughput multiplex immunoassay for the simultaneous quantification of specific antibodies to five respiratory syncytial virus proteins. mSphere. 2019;4:e00236–e00319. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00236-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kulkarni PS, Hurwitz JL, Simões EAF, Piedra PA. Establishing correlates of protection for vaccine development: considerations for the respiratory syncytial virus vaccine field. Viral Immunol. 2018;31:195–203. doi: 10.1089/vim.2017.0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]