Abstract

Background

Given the speculation that political participation is causing an epidemic of depression, this study examined how participation in political and non-political groups influenced depressive symptoms among older adults in Taiwan.

Methods

The 11-year follow-up data from the Taiwan Longitudinal Study on Ageing, covering 5334 persons aged 50 years and older, were analysed using random-effects panel logit models.

Results

Engagement in social groups reduced the likelihood of depression (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.64–0.80). However, there was a greater likelihood of depressive symptoms among older adults who were engaged in political groups when compared with those who were engaged in non-political groups (AOR: 1.87, 95% CI: 1.31–2.65). For older adults who remained politically engaged, participation in a greater number of non-political group types was associated with a lower likelihood of depression (e.g. at 1: AOR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.30–0.91; at 2+: AOR: 0.35, 95% CI: 0.18–0.67); this numbers-based effect was not prevalent among those who were solely engaged in non-political groups.

Conclusions

Political group attendance can result in negative mental health outcomes among older adults. Our findings suggest that reducing the prevalence of depression through social participation is conditional to the engagement type.

Keywords: depression, older adults, political groups, social engagement, Taiwan

Introduction

Geriatric depression is associated with medical illness, cognitive disorders, disability, mortality and suicide.1 Depression is the leading cause of disease burden in older adults: 10–15% of older adults have clinically significant depressive symptoms. Antidepressants were effective treatment reported; however, it might pose risk for adverse events among older adults due to polypharmacy.2 It is therefore increasingly important to identify the potential causes and any other interventions that may prevent depression among older persons.

The broader literature confirms that lower social participation in old age is associated with increased depressive symptoms.3–12 Social participation is defined as a person’s involvement in groups or organizations that provide interaction with others in the society.13 Participating in a social group tends to enhance social support networks, thus creating greater levels of attachment among participants in the same communities. The more groups a person belongs to, the more likely it is that he or she will have access to resources that support healthy ageing.14 More specifically, studies have found that active participation in community friendship groups,15 religious organizations,16 sports and hobby clubs11 and volunteer groups7 is associated with better mental health.

Few studies have examined how political participation influences mental health among older adult populations. Further, previous studies have contrastingly interpreted the association between political participation and depression, while the empirical evidence used for those hypotheses is also inconsistent.7,16,17 Several points thus merit further discussion. First is the claim that political participation results in a stronger sense of community and enhances social identity by providing opportunities to voice opinions through larger social networks, thereby reducing depressive symptoms.17 Nevertheless, this may be conditioned on the presence of a government that can build inter-partisan trust. Next, insights from the effort–reward balance theory indicate that low levels of reciprocity between the efforts spent and rewards received from long-term political engagement are associated with increased depression,16 but this neglects the given political context. As for the operationalization of political participation, previous research has examined political activities7,17 and/or participation in both political and community organizations16 rather than solely focusing on political group involvement. In addition, there is a lack of research comparing older adults engaged in political organizations with their non-political counterparts in regard to the association between political participation and depression. Finally, the scope of such an analysis should include nascent democracies, but most research has been limited to mature democracies16,17 or non-democratic regimes.7

The aim of this study was to examine the influence of participation in political and non-political groups on depressive symptoms among older adults in Taiwan, a relatively young democracy. In addition, we investigated the influence of participation in multiple groups on depression among the same study sample.

Methods

The unit of analysis was ‘individuals-year’. This study used data collected from the Taiwan Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TLSA), which was conducted by the Health Promotion Administration of Taiwan, thus offering a nationally representative sample of the Taiwanese population. This longitudinal study was based on a three-stage equal probability sampling design using household registration data and information collected during face-to-face interview. Data were collected across a total of six waves from 1989 to 2007. We collected a sample of 15 053 pooled time-series and cross-sectional observations from four of six survey rounds; that is, in 1996, 1999, 2003 and 2007.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using 10 items from the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Respondents rated how frequently each item applied to them over the course of the preceding week. Ratings were based on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). This short form of the CES-D thus generated total individual scores ranging from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. A dummy variable was created so that 1 = ‘respondents with depressive symptoms’ (≥10 points) and 0 = ‘otherwise’ (0–9 points).

As for the independent variables representing the level and type of engagement in social groups, participants were asked to indicate whether they were members of community friendship groups, religious groups, business associations, political groups, volunteer groups, clan associations and/or senior groups (0 = ‘no’; 1 = ‘yes’). Scores ranged from 0 to 7, with higher scores indicating higher levels of engagement in social groups. We also created a dummy variable so that 1 = ‘respondents participating in at least one group’ and 0 = ‘otherwise’. Finally, a list of binary variables was included for specific types of group participation.

Individual-level characteristics were set as control variables, including gender (binary, 1 = ‘male’), age, education level (0, 1–6, 7–9, 10–12 and ≥13 years), frequency of exercise (0, 1–2 and ≥3 times per week), and current living status (binary, 1 = living alone). Further, chronic diseases (hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, cancer, lung disease, arthritis and hepatobiliary disease) were recorded based on self-reported data. A count of conditions was created based on the total number of chronic conditions for each participant (ranging from 0 to 8), whereas the number of morbidities was treated as a categorical variable (0: ‘absence of disease’, 1-4: ‘mild to moderate’ and ≥5: ‘severe’). Older adults were also asked to indicate if financial difficulties had occurred in their family during the past 12 months (i.e. answers of ‘no’, ‘somewhat difficult’ and ‘very difficult’). Finally, self-rated economic situations were obtained using the item ‘In general, are you satisfied with your current economic status?’ This was answered on a 5-point Likert scale (very satisfied = 1, satisfied = 2, neither = 3, unsatisfied = 4 and very unsatisfied = 5, with options 1 and 2 were combined into ‘satisfied’ and options 4 and 5 combined into ‘not satisfied’). Table S1 summarizes characteristics of study participants in the total sample.

The vast majority of older adults changed very little or not at all across time (3504 participants with a sample of 9727 observations presenting all positive or negative mental health outcomes). Because the lack of variability within subjects indicates that the standard errors from fixed-effects models may be too large to tolerate, this study applied a random-effects panel logit model. For robustness tests, we changed the cutoff score for the determinant of depression from 10 to 9 or 11. Further, participants were asked to provide additional information on whether they were members of learning clubs for older adults from the 1999 survey in order to code the level and type of social group engagement. The literature also shows that some personality traits are linked to the susceptibility for depression, whereas others appear to be independent of mood state.18 Participants displaying all positive or negative mental health outcomes during each of the four survey rounds likely had certain traits that were not influenced by depressive episodes. This analysis thus excluded such participants and applied conditional logit fixed-effects models to estimate within-individual differences while controlling for unobserved individual heterogeneity that may have been correlated with the explanatory variable. Finally, individuals were excluded from analysis if they were unsatisfied with their current economic status, experienced serious financial hardship or reported at least five chronic diseases. This was because they were both more prone to depression and less likely to engage in social groups; to allege that social group engagement affects depression implies a spurious interrelationship.

Results

Respondents who lived alone (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 1.68, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.40–2.01), were not satisfied with their current economic status (AOR: 4.81, 95% CI: 4.02–5.76), experienced serious financial hardship (AOR: 3.28, 95% CI: 2.64–4.07) and reported at least five chronic diseases (AOR: 11.35, 95% CI: 8.02–16.07) were more likely to develop depression (Table S2). Further, increased age was associated with an increased likelihood of mental health problems (AOR: 1.05, 95% CI: 1.04–1.06). Contrastingly, male (AOR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.52–0.69) and more educated (AOR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.42–0.83) participants were less likely to report depressive symptoms. Respondents who engaged in physical exercise more than three times per week had a 51% lower likelihood of being depressed (AOR: 0.49, 95% CI: 0.44–0.56). See Tables S3 and S4 for similar results.

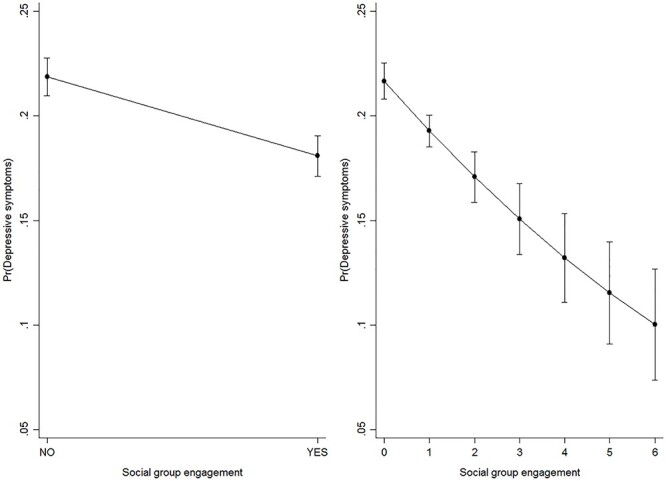

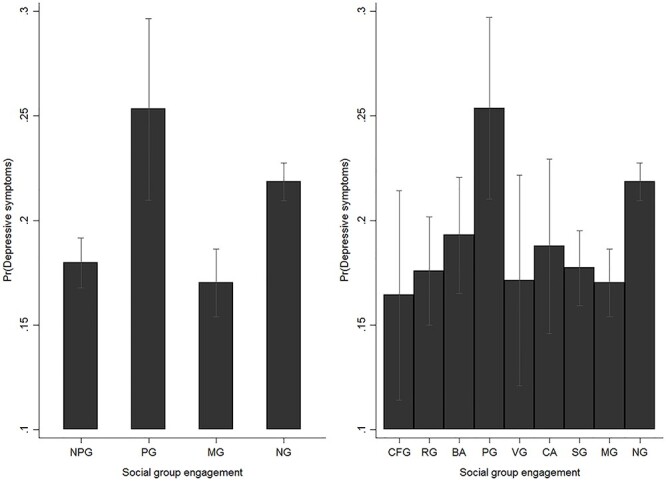

The level and type of social group engagement were related to significant reductions in depressive symptoms. Participating in at least one social group was associated with a lower likelihood of depression (AOR: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.64–0.80) (Fig. 1), whereas an increase in social group engagement of 1 resulted in a 19% lower such likelihood (AOR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.76–0.87). However, not all types of group participation reduced the symptoms of major depression. Indeed, respondents in political groups were more likely to report depressive symptoms than those in non-political groups (AOR: 1.87, 95% CI: 1.31–2.65) (Fig. 2). Respondents who reported engagement in non-political groups also had a lower likelihood of depression than those who did not participate in social groups (AOR: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.62–0.81). These results held even when the analysis divided non-political groups into community friendship groups, religious groups, business associations, volunteer groups, clan associations and senior groups.

Fig. 1.

The effects of social group engagement on the probability of depression among older adults, by levels, Taiwan, 1996–2007. Note: all results were based on random-effects panel logit models. Results correspond to model 1 and 2 of Table S2, supplementary material. Source: the author.

Fig. 2.

The effects of social group engagement on the probability of depression among older adults, by types, Taiwan, 1996–2007. Note: NPG: non-political groups, PG: political groups, MG: multiple groups, NG: no groups, CFG: community friendship groups, RG: religious groups, BA: business associations, VG: volunteer groups, CA: clan associations, SG: senior groups. All results were based on random-effects panel logit models. Results correspond to model 1 and 2 of Table S3, supplementary material. Source: the author.

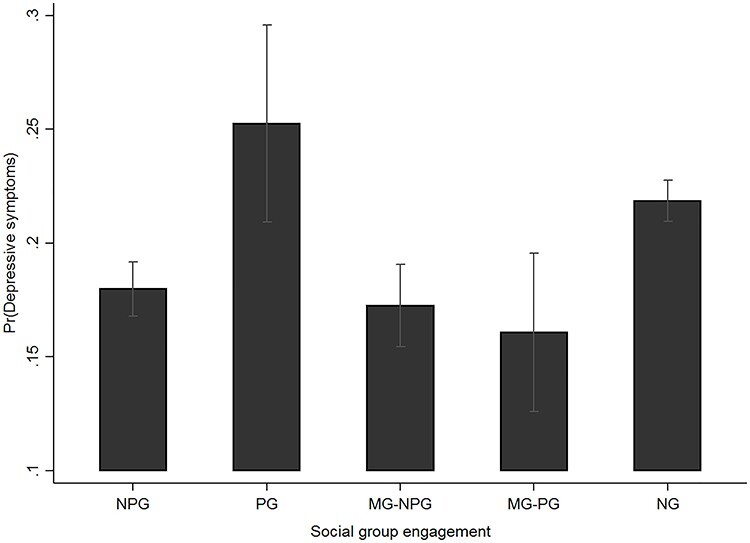

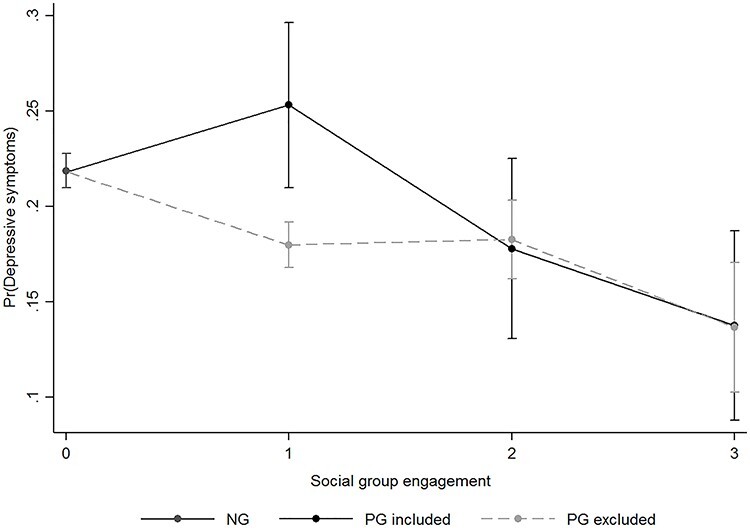

Respondents in both political and non-political groups were less likely to be depressed than those who were only engaged in political groups (AOR: 0.45, 95% CI: 0.28–0.72) (Fig. 3). Further, there were no statistically significant differences in depression likelihood between those engaged in both types and those in non-political groups only (AOR: 1.13, 95% CI: 0.76–1.67). Figure 4 shows the interplay between the level and type of engagement in social groups and the effects on depression likelihood. For those in political groups, participation in a greater number of non-political group types was associated with a lower likelihood of depression (e.g. at 1: AOR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.30–0.91; at 2+: AOR: 0.35, 95% CI: 0.18–0.67). For those engaged in non-political groups, the effects of engagement level on depression likelihood were not prevalent, that is, a 3% higher depression likelihood from 1 to 2 (not statistically significant) (AOR: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.82–1.28) and 36% lower depression likelihood from 1 to 3+ (AOR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.42–0.96). Table S5 shows the results of the robustness tests.

Fig. 3.

The effects of social group engagement on the probability of depression among older adults, by types, Taiwan, 1996–2007. Note: MG-NPG: multiple groups, excluding political groups, MG-PG: multiple groups, including political groups. All results were based on random-effects panel logit models. Results correspond to model 1 of Table S4, supplementary material. Source: the author.

Fig. 4.

The effects of social group engagement on the probability of depression among older adults, by levels and types, Taiwan, 1996–2007. Note: PG included: political groups are included, PG excluded: political groups are not included. All results were based on random-effects panel logit models. Results correspond to model 2 of Table S4, supplementary material. Source: the author.

Discussion

Main finding of this study

This study examined how participation in political and non-political groups influenced depressive symptoms among older adults in Taiwan. First, there was a greater likelihood of depressive symptoms among older adults who were engaged in political groups when compared with those who were engaged in non-political groups. Second, for older adults who remained politically engaged, participation in a greater number of non-political group types was associated with a lower likelihood of depression; this numbers-based effect was not prevalent among those who were solely engaged in non-political groups.

What is already known on this topic?

It is universally accepted that social participation benefits mental health for older adults. However, most studies have examined whether the level of social engagement3–12 or various forms of social participation3,7,11,15,16 explain mental health in older adulthood. There is dearth of literature on a consideration of both the level and type of group participation in regard to depression likelihood. Further, the literature is inconsistent about whether political participation exerts a positive impact on mental health in older age.7,16,17

What this study adds

This is the first study to examine how older adults in political organizations could influence mental health in a new democracy. Results showed that political group attendance could worsen mental health. Reasons for this are related to intense interparty competition that tends to weaken community belonging and contributes to a lack of meaning and purpose in life. New democratic governments face exceptionally strong distributive pressures. These are exerted both by groups that are re-entering the political arena after long periods of repression and established interest groups that are demanding reassurances.19 A new democratic government also frequently faces competition for political power from elites that were active in old regimes. In such an environment, competitive pressures tend to drive the government and its oppositional counterparts to indoctrinate their ideologies. This includes the conversion of party identifiers (especially partisans) into ‘true believers’, thereby leading to polarized expressions of support for certain political values.20 Further, individuals who identify with a given political party tend to positively evaluate their co-partisans while negatively assessing opposing partisans.21–23 Thus, institutionalized competition for political power creates party-based trust biases,24 which may hamper the individual sense of self among citizens. Many individuals may also attack major ideological differences held by friends or family members, which results in a weaker sense of political community that can trigger depression. Indeed, evidence shows that the sense of community is a crucial determinant for depression, anxiety and stress.25–27 A government that is rife with opposing ideologies also reflects a general departure from the concept of long-standing individual political beliefs, thus contributing to personal losses of meaning and purpose. In this context, a growing body of evidence supports the resulting phenomenon of ‘political depression’.28–30

Taiwan is a relatively young democracy, where competition between two electorally dominant parties has intensified since democratization. Because older people have stronger feelings of psychological attachment to an ideological in-group upon accepting relevant cues,31 we expected that in Taiwan, older adults who engaged in political groups were more likely to develop depression when compared with those who engaged in non-political groups. Empirical evidence confirms the arguments. Future research should analyse the effects of political group engagement on mental health across population groups and compare similar cases for providing the strongest basis for generalization.

Other types of social engagement (e.g. community friendship, religious and volunteer groups) were also associated with lower depression likelihood, which is consistent with previous research.3,7,15,16 We further found that such activities reduced the likelihood of depression among older adults who remained politically engaged. There are several possible explanations. First, this may help older adults in political groups reconnect with others through social relationships, allowing social benefits to accrue. Connecting with other members of a social group allows people to receive social support and to contribute positively to the lives of others, an important protective factor against loneliness and hopelessness.32 Research evidence indicates that social support enables older adults to create a positive self-image,33 exchange emotional intimacy34 and buffer against the deleterious effects of stressful life events,35 thereby reducing depression.

Second, intergroup contact tends to reduce perceptions of both outgroup hate and disconnectedness from political communities, thus combating mental health problems. Contact can help to reappraise how one thinks about outgroup members, open one’s heart to experience the abundance of diversity and generate affective ties and friendships, thus diminishing negative emotions including anxiety and depression. It is likely that other areas of social participation such as volunteering and religious involvement can increase the chances of contact with members of a political outgroup and, accordingly, reduce negative cross-partisan feelings.36 Participation in such activities can also result in perceived commonality between the self and the political outgroup, which is a remedy to affective polarization and interparty hostility.37

Third, such engagement may provide older people with a life purpose, thus reducing the risk of depression. Group membership helps the person to understand who they are, where they belong and how they make sense of the world, thus enhancing a person’s sense of purpose, belonging and self-worth. When individuals have a primary motivational force to achieve personal aims and living objectives, psychological distress declines. A review of the literature certainly shows a significant inverse relationship between purpose in life and depression among the old population.38,39

Notably, the effects of engagement level on depression likelihood were not prevalent among older adults in non-political groups. It appears arbitrary to argue that ‘over-engagement’ can have negative consequences for mental health. A literature review on preventive occupational health suggests that excessive time and effort spent in group participation leads to sustained activation with negative side effects, including psychological distress.40 Future studies should re-examine whether engagement level has a positive relationship with mental health.

We confirmed the differential effects of both the type and level of social participation on depression likelihood among older adults, thus suggesting that the type of social engagement is a more important predictor of mental health. This also highlighted a potential difficulty when measuring the level of social participation, that is, totalling scores for responses to questionnaire items about participation in certain categories of social activity and organization.3–10

Empirical evidence does not support the argument that members of political groups who report a higher likelihood of depression, compared with members of other types of social groups, complete less regular exercise, live alone or worry about their financial situation (Table S6). Thus, within this subset of individuals, it is probable that political group affiliation, rather than additional factors such as living alone, influences the likelihood of depression. However, this study suggests that factors such as frequency of exercise may link group participation status, rather than political group affiliation, to the likelihood of depression (Table S7).

Limitations of this study

This study had several limitations. First, more types of social engagement (e.g. sports clubs and cultural groups) were used to examine the predicted relationship.11 However, TLSA data (the most comprehensive available for social group engagement) allowed us to analyse the given group types. Second, participants were simply asked to indicate their involvement in each of the listed groups. There was no assessment of the time amounts spent on each group, thus causing bias. Future research should test the validity of the proposed arguments using additional measurements. Third, no data exist for unpacking the pathway underlying how political group engagement would not exert a positive impact on mental health outcomes. More detailed data may enable the examination of theoretical expectations. Finally, 1879 participants who completed the questionnaire after 1996 were lost to follow-up due to death. Those who were more likely to die were older, male, less educated, with multi-morbidities and less likely to participate in social groups. Thus, selection bias due to follow-up loss threatened the internal validity of estimates derived from the longitudinal data. Nevertheless, inverse probability weighting models accounting for the participants lost to follow-up revealed robust results (Table S8).

Research ethics and patient consent

The use of data in the study was exempted from Institutional Review Board approval of the Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University and Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan (CMUH-109REC1-154).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

For their comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this article, we would like to thank Dr Yu-Hung Chang (Department of Public Health, China Medical University) and anonymous reviewers.

Yu-Chun Lin, Visiting Staff

Huang-Ting Yan, Academia Sinica Postdoctoral Scholar

Contributor Information

Yu-Chun Lin, Department of Chinese Medicine, China Medical University Hospital, 40447 Taichung City, Taiwan, ROC; Graduate Institute of Integrated Medicine, China Medical University, 40447 Taichung City, Taiwan, ROC.

Huang-Ting Yan, Institute of Political Science, Academia Sinica, 115 Taipei City, Taiwan, ROC.

Funding

China Medical University Hospital [grant number: DMR-110-164].

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Casey DA. Depression in older adults: a treatable medical condition. Prim Care 2017;44:499–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kok RM, Reynolds CF. Management of depression in older adults: a review. JAMA 2017;317:2114–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Amagasa S, Fukushima N, Kikuchi Het al. Types of social participation and psychological distress in Japanese older adults: a five-year cohort study. PLoS One 2017;12:E0175392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bourassa KJ, Memel M, Woolverton Cet al. Social participation predicts cognitive functioning in aging adults over time: comparisons with physical health, depression, and physical activity. Aging Ment Health 2017;21:133–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chiao C, Weng LJ, Botticello AL. Social participation reduces depressive symptoms among older adults: an 18-year longitudinal analysis in Taiwan. BMC Public Health 2011;11:E292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Glass TA, Mendes De Leon CF, Bassuk SSet al. Social engagement and depressive symptoms in late life: longitudinal findings. J Aging Health 2006;18:604–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guo Q, Bai X, Feng N. Social participation and depressive symptoms among Chinese older adults: a study on rural–urban differences. J Affect Disord 2018;239:124–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee KL, Wu CH, Chang CIet al. Active engagement in social groups as a predictor for mental and physical health among Taiwanese older adults: a 4-year longitudinal study. Int J Gerontol 2015;9:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lou VWQ, Chi I, Kwan CWet al. Trajectories of social engagement and depressive symptoms among long-term care facility residents in Hong Kong. Age Ageing 2013;42:215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Niedzwiedz CL, Richardson EA, Tunstall Het al. The relationship between wealth and loneliness among older people across Europe: is social participation protective? Prev Med 2016;91:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tomioka K, Kurumatani N, Hosoi H. Positive and negative influences of social participation on physical and mental health among community-dwelling elderly aged 65–70 years: a cross-sectional study in Japan. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:E111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bonsdorff MB, Rantanen T. Benefits of formal voluntary work among older people. A review. Aging Clin Exp Res 2011;23:162–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levasseur M, Richard L, Gauvin Let al. Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: proposed taxonomy of social activities. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:2141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jetten J, Branscombe NR, Haslam SAet al. Having a lot of a good thing: multiple important group memberships as a source of self-esteem. PLoS One 2015;10:E0124609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Min J, Ailshire J, Crimmins EM. Social engagement and depressive symptoms: do baseline depression status and type of social activities make a difference? Age Ageing 2016;45:838–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Croezen S, Avendano M, Burdorf Aet al. Social participation and depression in old age: a fixed-effects analysis in 10 European countries. Am J Epidemiol 2015;182:168–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim BJ, Auh E, Lee YJet al. The impact of social capital on depression among older Chinese and Korean immigrants: similarities and differences. Aging Ment Health 2013;17:844–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Klein DN, Kotov R, Bufferd SJ. Personality and depression: explanatory models and review of the evidence. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2011;7:269–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haggard S, Kaufman RR. The Political Economy of Democratic Transitions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goren P, Federico CM, Kittilson MC. Source cues, partisan identities, and political value expression. Am J Polit Sci 2009;53:805–20. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carlin RE, Love GJ. Political competition, partisanship and interpersonal trust in electoral democracies. Br J Polit Sci 2018;48:115–39. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parker MT, Janoff-Bulman R. Lessons from morality-based social identity: the power of outgroup “hate,” not just ingroup “love”. Soc Justice Res 2013;26:81–96. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weisel O, Böhm R. “Ingroup love” and “outgroup hate” in intergroup conflict between natural groups. J Exp Soc Psychol 2015;60:110–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brewer MB. The psychology of prejudice: ingroup love and outgroup hate? J Soc Issues 1999;55:429–44. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fowler K, Wareham-Fowler S, Barnes C. Social context and depression severity and duration in Canadian men and women: exploring the influence of social support and sense of community belongingness. J Appl Soc Psychol 2013;43:S85–96. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Handley TE, Rich J, Lewin TJet al. The predictors of depression in a longitudinal cohort of community dwelling rural adults in Australia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2019;54:171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thomas VJ, Bowie SL. Sense of community: is it a protective factor for military veterans? J Soc Serv Res 2016;42:313–31. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pitcho-Prelorentzos S, Kaniasty K, Hamama-Raz Yet al. Factors associated with post-election psychological distress: the case of the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Psychiatry Res 2018;266:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Simchon A, Guntuku SC, Simhon Ret al. Political depression? A big-data, multimethod investigation of Americans’ emotional response to the Trump presidency. J Exp Psychol Gen 2020;149:2154–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tashjian SM, Galván A. The role of mesolimbic circuitry in buffering election-related distress. J Neurosci 2018;38:2887–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Devine CJ. Ideological social identity: psychological attachment to ideological in-groups as a political phenomenon and a behavioral Influence. Polit Behav 2015;37:509–35. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Haslam C, Steffens NK, Branscombe NRet al. The importance of social groups for retirement adjustment: evidence, application, and policy implications of the social identity model of identity change. Soc Issues Policy Rev 2019;13:93–124. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gyasi R, Phillips D, Abass K. Social support networks and psychological wellbeing in community-dwelling older Ghanaian cohorts. Int Psychogeriatr 2019;31:1047–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Choi E, Han KM, Chang Jet al. Social participation and depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older adults: emotional social support as a mediator. J Psychiatr Res 2021;137:589–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wolff JK, Lindenberger U, Brose Aet al. Is available support always helpful for older adults? Exploring the buffering effects of state and trait social support. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2016;71:23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Warner BR, Villamil A. A test of imagined contact as a means to improve cross-partisan feelings and reduce attribution of malevolence and acceptance of political violence. Commun Monogr 2017;84:447–65. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wojcieszak M, Warner BR. Can interparty contact reduce affective polarization? A systematic test of different forms of intergroup contact. Polit Commun 2020;37:789–811. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Van der Heyden K, Dezutter J, Beyers W. Meaning in life and depressive symptoms: a person-oriented approach in residential and community-dwelling older adults. Aging Ment Health 2015;19:1063–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Volkert J, Härter M, Dehoust MCet al. The role of meaning in life in community-dwelling older adults with depression and relationship to other risk factors. Aging Ment Health 2019;23:100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shimazu A, Schaufeli WB, Kubota Ket al. Is too much work engagement detrimental? Linear or curvilinear effects on mental health and job performance. PLoS One 2018;13:E0208684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.