Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the current research was to identify the influence of university students' personality traits on their fear of COVID-19 and psychological resilience levels.

Design and methods

A cross-sectional trial was completed with 690 students. Descriptive statistics and correlations were calculated, and a path analysis was employed with the objective of assessing the model fit and investigating direct and indirect impacts.

Findings

Among personality traits, conscientiousness and neuroticism were observed to affect fear of COVID-19, and conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience had an effect on psychological resilience. The tested model has a good fit and explains the direct effects of the study variables.

Practice implications

Nurses should improve university students' psychological resilience by supporting them with protective and improving factors. The role of the psychiatric nurse is important in providing conscious and need-oriented support in extraordinary events such as pandemics.

Keywords: COVID-19, Fear, Nursing, Personality traits, Psychological resilience, University student

Introduction

Human beings have faced many epidemics in the historical process, and COVID-19 has been the last epidemic they must fight (Cucinotta & Vanelli, 2020). Human beings, who have been confronted with many social and individual limitations with the declaration of the disease a pandemic by the WHO because of the rapid spread of the virus worldwide, have experienced new circumstances, which they have not experienced in the recent past. In addition to the risk of virus transmission and death, the pandemic has also brought about an intense psychological pressure due to reasons such as deterioration of the routine functioning of life, feeling of uncertainty, fear of death, and fear of losing relatives. People's anxious and fearful state of mind originating from their fear of being infected with COVID-19 is defined by the concept of “fear of COVID-19” (Ahorsu et al., 2020). There is a lot of research in the literature indicating that fear of COVID-19 leads to mental, cognitive, and behavioral problems in people of all ages (Alici & Copur, 2021; Fitzpatrick et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020; Yue et al., 2020; Feng et al., 2020; Evren et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Thus, fear of COVID-19 can be said to lead to significant psychological problems as well as health problems (Gundogan, 2021).

While trying to protect themselves from the disease, people are also trying to stay psychologically healthy during this period (Karal & Biçer, 2020). The concept of psychological resilience is described as a set of characteristics and protective mechanisms that facilitate the individual's successful adaptation to the existing process in the face of difficult conditions (Gundogan, 2021). Psychological resilience has been suggested to protect against fear of COVID-19, which manifests itself as a mental outcome of the pandemic, and studies have shown that people with high psychological resilience experience less depression, stress, and anxiety related to COVID-19 (Albott et al., 2020; Barzilay et al., 2020; Labrague & De los Santos, 2020). Therefore, psychological resilience can be considered an important component in coping with the fear resulting from COVID-19 (Albott et al., 2020).

Although the pandemic usually affects the whole society, the severity and intensity of reactions vary from person to person. Meanwhile, there are personal differences with respect to psychological resilience (Polatcı & Tınaz, 2021). The most important reason for individual differences is the individual's personality, which makes him/her unique among billions of people. Personality, which includes the traits that the individual brings from birth and acquires through his/her life experiences, can be defined as “the unique pattern of factors affecting feelings, thoughts, and ways of behavior that distinguish a person from others.” Due to these traits, the mental reactions in this traumatic process caused by the pandemic take place at different levels individually (Baymur, 2017; Polatcı & Tınaz, 2021). Particularly university students who try to complete their adolescent development processes and adapt to developmental duties specific to adulthood, on one hand, and face academic and social requirements in the university environment, on the other hand, are a more fragile group in this process. Research in the literature has stated that the negativities caused by the pandemic affect the young population more, and university students are the group at risk (Brooks et al., 2020; Kaya, 2020; Luo et al., 2020; Torales et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Xiao, 2020). In addition to their anxiety (Khodabakhshi-koolaee, 2020) and social problems arising from the quarantine, university students were also adversely affected by the sudden and radical changes in their daily lives. With the closure of universities and the transition to distance education, many of them had to move to the houses of their families, working students lost their jobs, and even some of them had to discontinue their education. It is crucial to monitor the mental health of university students, who will carry the effects of the pandemic from today to the future and form social memory, during the pandemic period (Yorguner et al., 2021; Zhai & Du, 2020; Alici & Copur, 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to common fear and anxiety due to the nature of the pandemic. The fear induced by this traumatic life experience in people and the psychological resilience levels that represent their coping skills will differ within the scope of personality traits (Ahorsu et al., 2020; Kaya, 2020; Xiao, 2020). Although there are studies in the literature examining the correlation between fear of COVID-19 and psychological resilience, the predictive role of personality traits has not been investigated. It is thought that determining how these factors are associated with each other will contribute to the literature regarding the management of mental health outcomes. In this respect, the research was done to reveal the effects of university students' personality traits on their fear of COVID-19 and psychological resilience levels.

Materials and methods

Aim

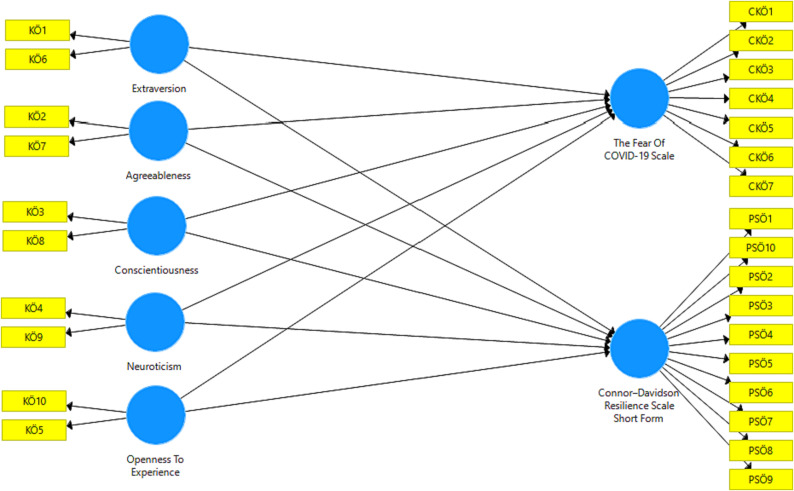

The current research has the following objectives: (a) to identify the impacts of personality traits of students studying in two state universities in the Marmara and Western Black Sea regions of Turkey on their fear of COVID-19 and emotional resilience levels, and (b) to examine the relationships between the relevant results through a path analysis. The hypothesized model is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized path model of the correlation between fear of COVID-19 and emotional resilience in accordance with personality traits.

Therefore, our initial hypotheses were as follows:

H1a

The extraverted personality trait of university students positively affects their fear of COVID-19.

H1b

The agreeable personality trait of university students positively affects their fear of COVID-19.

H1c

The conscientious personality trait of university students positively affects their fear of COVID-19.

H1d

The neurotic personality trait of university students positively affects their fear of COVID-19.

H1e

University students' openness to experience positively affects their fear of COVID-19.

H2a

The extraverted personality trait of university students positively affects their emotional resilience.

H2b

The agreeable personality trait of university students positively affects their emotional resilience.

H2c

The conscientious personality trait of university students positively affects their emotional resilience.

H2d

The neurotic personality trait of university students positively affects their emotional resilience.

H2e

University students' openness to experience positively affects their emotional resilience.

Design and sampling

The current research had a cross-sectional design. In the research, the sample size was computed at a 95 % confidence level by utilizing the “G. Power-3.1.9.2” software. According to the analysis, the standardized effect size was found to be 0.160 at the level of α = 0.05 based on previous research (Lü et al., 2014), and the minimum total number of samples was calculated as 501 with 0.95 theoretical power.

Participants

The study population consisted of all students studying at Sakarya University and Karabük University. For this cross-sectional study, 720 students were accessed and grouped with the stratified sampling method. Thirty participants were excluded because of missing data. Therefore, the study sample comprised 690 university students. The inclusion criteria were determined in the following way: (a) Volunteering to participate in the research, (b) Speaking and understanding Turkish well.

There are health units (MEDIKO-Social Center) within the scope of both universities where the study was conducted, and counseling and support was provided by psychologists to university students who requested during the pandemic process in these units.

Data collection

Because of the COVID-19 outbreak, data collection was carried out via Google Forms. The survey was shared in the electronic environment by utilizing Google Drive's online service system (https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSdNKpYaOABW4woORu5RQZiQyIG6k8ETzuH4MBnjKMO08E8SAw/viewform?usp=sf_link) and then on Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram. It was published between October 5 and November 22, 2021, for 7 weeks. Individuals with access to the survey link responded to the questions. Filling out the scales took about 10–15 min. The data were downloaded in the CSV format, and their analysis was performed after their revision and standardization.

Data collection tools

The online survey was prepared by the researchers by making use of available studies (Polatcı & Tınaz, 2021; Nazari et al., 2021) and comprised five parts. In the first part, the purpose, scope, and stages of the study were explained. In the second part of the survey, 10 questions were asked about the descriptive characteristics of the participants, including age, gender, department and class, catching COVID-19 infection, and vaccination status. In the third part, the Big Five Personality Traits Scale was used. The 10-item Big Five Personality Traits Scale developed by Rammstedt and John (2007) was adapted to Turkish by Horzum et al. (2017). The scale comprises five sub-dimensions: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience, and there are a total of two items for each dimension, one of which is reverse. These two items are combined to form the sub-dimension score. It was revealed that Cronbach's alpha internal consistency values for the sub-dimensions of the scale ranged between 0.81 and 0.90, and the composite reliability coefficients ranged between 0.73 and 0.85. Scale assessment was performed according to the sub-dimensions. As the scores for each sub-dimension increase, the characteristics of that dimension increase in the individual (Horzum et al., 2017). The fourth part includes the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. This scale, which was developed by Ahorsu et al. (2020) to determine individuals' levels of fear of coronavirus, was adapted to Turkish by Ladikli et al. (2020). Cronbach's alpha internal consistency coefficient of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale is 0.86. High scores acquired from the scale demonstrate that individuals have high fear of coronavirus. In the last part, the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale was benefited from. The 10-item short version of the 25-item resilience scale developed by Connor and Davidson (2003), which was applied to university students by Campbell-Sills and Stein (2007) for testing, was employed. The scale's Turkish validity and reliability study was carried out by Kaya and Odacı (2021). The scale's internal consistency coefficient is 0.81. The 10-item scale contains five-point Likert-type scoring. High scores acquired from the scale are considered to demonstrate high psychological resilience.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were utilized to address the study hypotheses. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 24 software (IBM Corporation) and SmartPLS. Descriptive statistics (mean, median and standard deviation [SD]) were employed to show the distribution of the study variables in the overall sample (n = 690).

The path analysis was conducted to test our conceptual model that associates fear of COVID-19 and psychological resilience with the personality traits of university students (e.g., extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience) (using SmartPLS software).

Within the framework of the measurement model, the composite reliability (CR) value was calculated for composite reliability, the average variance extracted (AVE) value was computed for convergent validity, and the Fornell-Larcker criterion and HTMT (Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio) values were calculated for discriminant validity (Doğan, 2019: 82).

Data analysis for the research uses the following guideline: firstly, confirmatory factor analysis is conducted to measure the reliability and validity of the research instrument. A Smart PLS path model analysis is conducted for the purpose of testing the three hypotheses of the present study. The results of the mentioned test will clearly show whether significant relationships exist between the independent variables and the dependent variable. Whereas the R2 value is utilized as an indicator for the overall predictive strength of the model according to these values, the value of 0.67 is considered substantial, 0.33 moderate, and 0.19 weak (Hair et al., 2017; Henseler et al., 2009). Whereas the f2 value is employed as a measure to establish the effect size of predicting variable in the model based on these values, the value of 0.35 is considered as large, 0.15 as medium, and 0.02 as weak (Hair et al., 2017). Finally, if the Q2 value for a dependent variable is above zero, it shows that the model has predictive relevance. The reported statistical significance was two-sided and set at the 5 % level. In our model, we assumed that students' personality traits had direct and indirect impacts on their fear of COVID-19 and psychological resilience (see Fig. 1).

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was received from the Health Ethics Committee of Sakarya University (Date: 17.09.2021 Issue: E-71522473-050.01.04-64314419). Institutional permission was acquired from the universities where the study was carried out. Furthermore, written permission was received from the Republic Ministry of Health, General Directorate of Health Services, Scientific Research Platform. The current research was done in line with the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The consent form was on the survey's first page. The participants were assured that they had the right to refuse to take part in the study and that all information to be given would be kept confidential. The students who participated in the research stated that they had read, understood, and agreed to take part on a voluntary basis by marking the “I agree” option, then completed the other parts of the questionnaire. Google Forms has privacy standards that involve protecting, not using, data; not sharing data without permission; and not selling personal information.

Results

Of the participants, 42.9 % are between 20 and 21 years of age, and 64.2 % are female. When the distribution of the participants in accordance with their scientific fields is reviewed, it is observed that 34.5 % study Science, 33.9 % study Social Sciences, and 31.4 % study Health Sciences. Of the participants, 91.7 % did not have any chronic disease, 24.9 % had a history of COVID-19 infection (diagnosed with PCR), and 90.2 % had two doses of vaccine. Families of 47.4 % had had COVID-19, and 23.5 % had losses in their families due to COVID-19.

The validity and reliability findings of the data collection tools are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Validity and reliability of the measures.

| Factor Load | CR | AVE | Cronbach's alpha | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraversion | K1 | 0.791 | 0.820 | 0.696 | 0.818 |

| K6 | 0.875 | ||||

| Agreeableness | K2 | 0.930 | 0.753 | 0.614 | 0.719 |

| K7 | 0.604 | ||||

| Conscientiousness | K3 | 0.735 | 0.817 | 0.693 | 0.807 |

| K8 | 0.920 | ||||

| Neuroticism | K4 | 0.972 | 0.757 | 0.626 | 0.700 |

| K9 | 0.554 | ||||

| Openness to experience | K5 | 0.551 | 0.723 | 0.582 | 0.676 |

| K10 | 0.927 | ||||

| Fear of Covid-19 | CKÖ1 | 0.661 | 0.904 | 0.574 | 0.905 |

| CKÖ2 | 0.708 | ||||

| CKÖ3 | 0.875 | ||||

| CKÖ4 | 0.742 | ||||

| CKÖ5 | 0.735 | ||||

| CKÖ6 | 0.754 | ||||

| CKÖ7 | 0.810 | ||||

| Psychological resilience | PSÖ1 | 0.598 | 0.871 | 0.509 | 0.870 |

| PSÖ2 | 0.726 | ||||

| PSÖ3 | 0.402 | ||||

| PSÖ4 | 0.642 | ||||

| PSÖ5 | 0.482 | ||||

| PSÖ6 | 0.724 | ||||

| PSÖ7 | 0.632 | ||||

| PSÖ8 | 0.718 | ||||

| PSÖ9 | 0.737 | ||||

| PSÖ10 | 0.650 | ||||

An evaluation of the measurement model is presented in Table 1. For all constructs, Cronbach's alpha (varying between 0.700 and 0.905) indicates good reliability over 0.60. Moreover, as shown in Table 1, all factor loadings are above 0.4, and the CR value for all constructs (ranging from 0.723 to 0.904) is >0.7 and higher than the relevant AVE, which indicates good construct reliability and convergent validity. AVEs are >0.5 for all constructs.

As observed in Table 2 , the correlation coefficients of the variables are lower than the square root of AVE values, and the Fornell-Larcker criteria are met. Furthermore, when the values in the table are reviewed, it is observed that the HTMT values are lower than the threshold value (<0.90). According to the findings in Table 2, discriminant validity can be said to be provided.

Table 2.

Fornell-Larcker Criterion Analysis and Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) Ratio.

| Fear of Covid-19 | Openness to experience | Extraversion | Neuroticism | Psychological resilience | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fornell-Larcker criterion | |||||||

| Fear of Covid-19 | 0.758 | ||||||

| Openness to experience | −0.019 | 0.763 | |||||

| Extraversion | −0.074 | 0.263 | 0.834 | ||||

| Neuroticism | 0.267 | −0.234 | −0.247 | 0.791 | |||

| Psychological resilience | −0.410 | 0.356 | 0.482 | −0.535 | 0.713 | ||

| Agreeableness | −0.103 | 0.111 | 0.256 | −0.226 | 0.310 | 0.784 | |

| Conscientiousness | −0.145 | 0.259 | 0.438 | −0.192 | 0.511 | 0.348 | 0.833 |

| Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio | |||||||

| Fear of Covid-19 | |||||||

| Openness to experience | 0.043 | ||||||

| Extraversion | 0.071 | 0.276 | |||||

| Neuroticism | 0.289 | 0.223 | 0.239 | ||||

| Psychological resilience | 0.423 | 0.366 | 0.482 | 0.564 | |||

| Agreeableness | 0.100 | 0.106 | 0.258 | 0.275 | 0.314 | ||

| Conscientiousness | 0.144 | 0.282 | 0.447 | 0.184 | 0.502 | 0.361 | |

The Varience Inflation Faktor (VIF) values related to personality traits sub-dimensions are presented in Table 3 . All values are below the critical value (<3). This shows that there is no linearity between the relevant variables.

Table 3.

The VIF values related to personality traits sub-dimensions.

| VIF values | |

|---|---|

| Extraversion | 1.921 |

| Agreeableness | 1.460 |

| Conscientiousness | 1.842 |

| Neuroticism | 1.408 |

| Openness to experience | 1.353 |

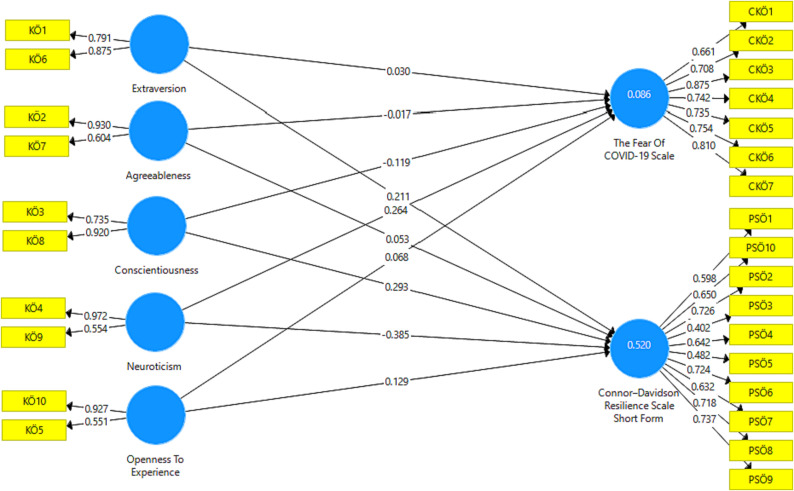

When the model analysis results are examined in Table 4 and Fig. 2 , conscientiousness and neuroticism are seen to have a statistically significant impact on fear of COVID-19 (p < 0.05). When the R2 values of the model are examined, conscientiousness and neuroticism explain 8.6 % of the change in fear of COVID-19. Conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness to experience and extraversion are seen to have a statistically significant impact on psychological resilience (p < 0.05). When the R2 values of the model are examined, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience are revealed to explain 52 % of the change in psychological resilience.

Table 4.

Model analysis results.

| Hypotheses | β | t | p | f2 | R2 | Q2 | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraversion➔ Fear of Covid-19 | 0.030 | 0.635 | 0.526 | 0.001 | 0.086 | 0.040 | ✖ |

| Agreeableness➔ Fear of Covid-19 | −0.017 | 0.204 | 0.839 | 0.000 | ✖ | ||

| Conscientiousness ➔ Fear of Covid-19 | −0.198 | 2.046 | 0.041⁎ | 0.011 | ✔ | ||

| Neuroticism➔ Fear of Covid-19 | 0.264 | 5.125 | 0.000⁎ | 0.070 | ✔ | ||

| Openness to experience➔ Fear of Covid-19 | 0.068 | 1.375 | 0.170 | 0.004 | ✖ | ||

| Extraversion ➔ Psychological Resilience | 0.211 | 4.391 | 0.000⁎ | 0.069 | 0.520 | 0.189 | ✔ |

| Agreeableness ➔ Psychological Resilience | 0.053 | 1.368 | 0.172 | 0.005 | ✖ | ||

| Conscientiousness ➔ Psychological Resilience | 0.293 | 6.517 | 0.000⁎ | 0.129 | ✔ | ||

| Neuroticism ➔ Psychological Resilience | −0.385 | 8.874 | 0.000⁎ | 0.276 | ✔ | ||

| Openness to experience ➔ Psychological Resilience | 0.129 | 3.226 | 0.001⁎ | 0.031 | ✔ |

p < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Path model of the study.

In accordance with the observed results and the comparison of fit indices with the required criteria, the said model can be considered a fit model. As observed in Fig. 2, hypotheses (except H1a, H1b, H1e, H2a, and H2b) were accepted. Of the five personality traits, agreeableness has no significant and direct influence on fear of COVID-19 and emotional resilience.

Discussion

The findings of the current study, which was conducted to reveal the impacts of personality traits on fear of COVID-19 and psychological resilience levels in university students, show that conscientious and neurotic personality traits have a statistically significant effect on fear of COVID-19 and psychological resilience.

It is crucial to concentrate on the mental health of university students during crises and pandemics (Fuentes et al., 2021). Studies indicate a substantial increase in psychological problems in young people during the COVID-19 pandemic (McGinty et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020). A study conducted with 1653 participants aged 18 years and over from 63 countries showed that young age groups were more vulnerable to mental health problems, e.g., anxiety, stress, and depression, during the COVID-19 pandemic and needed more support (Varma et al., 2021). Students may experience more stress during the pandemic due to interruptions in education, concerns about personal or family health, and social isolation. The above-mentioned changes can lead to increased behavioral changes, concentration problems, and the use of negative coping strategies (Fuentes et al., 2021). With the effect of some factors such as personality traits, differences are observed in the way each individual copes with negative situations and their attitudes and behaviors toward circumstances.

In this study, whose sample consisted of university students, the conscientious personality trait was revealed to have a reducing impact on fear of COVID-19. The conscientious personality trait refers to being planned, attentive, and showing a degree of resulting self-control. Conscientious individuals have the ability to control their impulses (Horzum et al., 2017). During this period, when people are faced with the threat of COVID-19, conscientiousness improves individuals' compliance with the rules and taking precautions. A study by Mula et al. (2021) involving university students elucidated that the threat of COVID-19 increased conscientiousness (Mula et al., 2021). There are other studies showing the influence of high conscientiousness on buffering the negative effect of the pandemic (Li et al., 2020; Rodriguez et al., 2021; Schnell & Krampe, 2020). Considering the findings of the studies, fear of COVID-19 may decrease as conscientiousness increases, and conscientiousness may increase with the effect of the threat and stress of COVID-19. The relationship between these factors may not be the same as in the early days when there was more uncertainty about the pandemic. People's reactions may change over time because of adaptation to big adverse life experiences. In a study from Slovakia, behavioral and emotional data were collected during the first and second waves of the pandemic, and it was observed that the influence of personality traits and fear of COVID-19 decreased statistically significantly (Kohút et al., 2021). It is believed that the perception of the situation may also evoke responses or behaviors stimulated by some personality traits (Zajenkowski et al., 2020).

The neurotic personality trait is associated with the individual's emotional balance. Due to the problems experienced in ensuring emotional balance, these individuals are prone to experiencing negative emotions, e.g., depression and anxiety. They feel anxious, restless, and upset and cope with stress poorly (Horzum et al., 2017). In the current research, a positive association was determined between neuroticism and fear of COVID-19. According to this result, fear of COVID-19 rises as the level of neuroticism increases. In the literature, studies also support this result (Fink et al., 2021; Kohút et al., 2021). Neuroticism is thought to increase fear of COVID-19 due to the tendency to experience negative emotions including anxiety, anger, and depression and weak coping power.

In a study, which involved 50 male participants aged 18–25 years, took 4.5 years, and was completed with 28 participants who were evaluated before, during, and after military service, one of the stressful life experiences, an increase was observed in neuroticism in participants during military service. After military service, however, there was a decrease in neuroticism (Magal et al., 2021). This situation coincides with the assumption that the effect of life experiences on personality traits may be temporary (Ormel et al., 2017). To test this assumption in the processes experienced during the COVID-19 period, there is a need for studies on the same group to research the relationships before, during, and after the pandemic.

Psychological resilience means the ability to withstand difficulties and positive adaptation in the face of difficulties (Lutha & Cicchetti, 2000). In a study analyzing university students' psychological resilience during COVID-19 restrictions, Serrano Sarmiento et al. (2021) revealed that psychological resilience levels were usually high (highest in men and those over 25 years of age), and students studying Health Sciences had a higher ability to adapt to change and overcome the difficulties brought by the pandemic (Serrano Sarmiento et al., 2021). Conscientiousness, a stable personality trait, is described as the ability to regulate, direct, or control a person's impulsive thoughts, emotions, and behaviors (Telzer et al., 2011). Assuming that there is a supportive positive correlation between conscientiousness and psychological resilience based on the aforesaid characteristics, the findings of this research, which indicate an increase in psychological resilience as conscientiousness increases, are considered to be consistent.

In a study performed on nursing students, the rate of neuroticism was found to increase in women and as age decreased (17–24 years) (Cuartero & Tur, 2021). A high level of neuroticism is correlated to a negative or excessively uncontrolled emotional approach, poor coping, and impulsive problems. Therefore, it is an expected result that it has a negative effect on psychological resilience. In the literature, there are studies indicating that neuroticism is associated with decreased psychological resilience (Findyartini et al., 2021) or that there is no association (Kocjan et al., 2021). The findings of the current research support the findings of studies in the literature indicating that neuroticism is correlated to decreased psychological resilience.

Openness to experience, which is accepted as a positive personality trait, contains sensitive, flexible and creative features, while, extraversion is a personality trait that has features such as being lively, cheerful, sociable and social (Erkuş & Tabak, 2010; Karduz & Şar, 2019). In a study conducted with university students, extraversion and openness to experience were found to have a positive effect on resilience (Polatcı & Tınaz, 2021), and there are similar studies in different groups in the literature (Eroğlu, 2022, Yazıcı Çelebi, 2021).

During the COVID-19 period, children and adolescents aged 18 years and under are also vulnerable groups at high risk of being adversely affected. A systematic review revealed that children and adolescents aged 18 years and under, who were affected by the pandemic, experienced fear, anxiety and disruptions in their daily routines but exhibited resilience with the right support (Berger et al., 2021). In this process, factors such as the way parents, healthcare providers, and the media reflect the event, previous experiences and support are considered to affect the fear experienced by children and the developing resilience (Berger et al., 2021). Psychological resilience is a significant variable to decrease and prevent the adverse impacts of the pandemic. It contributes to post-traumatic positive development (Finstad et al., 2021). Some personality traits such as extraversion are seen to be associated with post-traumatic development during the COVID-19 period with the effect of social support and coping strategies (Xie & Kim, 2022).

Conclusion

In the current results, conscientiousness, one of the personality traits of university students, adversely affects fear of COVID-19, and neuroticism has a positive and direct influence on fear of COVID-19. Meanwhile, neuroticism was observed to adversely affect psychological resilience, and conscientiousness and openness to experience to have a positive direct impact on psychological resilience.

Implications for nursing practice

The COVID-19 outbreak leads to numerous physical and mental health conditions in different groups. It is an undeniable fact that, among these groups, university students are exposed to the stress induced by the pandemic. The present research emphasizes that nurses, who play a role in maintaining and improving physical mental health, should plan their approaches considering the personal differences regarding university students' psychological resilience. Nurses should support and improve university students' psychological resilience with protective and improving factors. Nurses in health centers of universities and health personnel in health research and application councils should implement activities to strengthen psychological resilience by adopting a student-centered approach according to students' personality traits. Our current students will form the adult memory of the future. Therefore, nurses play an important role in raising their awareness and supporting them in their needs during the pandemic period. In addition, interventions to increase psychological resilience should be added to emergency measures to be prepared for extraordinary crisis situations such as pandemics and natural disasters. It can be said that psychological support activities should be increased and psychological counseling centers should be made more active in order to reduce the negative effects on university students, especially in crisis situations. It is the responsibility of educational institutions to employ psychologists, nurses and social workers in order to provide adequate service with the arrangements to be made in this regard.

Limitations

The data in this study were analyzed cross-sectionally. The correlational relationships among the variables do not imply cause and effect. There is also a need for studies investigating the long-term, causal effects of personality traits on fear of COVID-19 and psychological resilience levels. The findings are based on data acquired from self-report measures with the risk of bias. Despite the said limitations, the research findings provide useful data to health professionals who deal with the mental health problems of university students arising from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

The conception and design of the study: NÇ, GH, AE, ÖKS; acquisition of data: AE, ÖKS, GH; analysis and interpretation of data: C; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: NÇ, GH, AE, ÖKS; final approval of the version to be submitted: NÇ, GH, AE, ÖKS.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Ethics Committee of Sakarya (17.09.2021 Issue: E-71522473-050.01.04-64314419).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahorsu D.K., Lin C.Y., Imani V., Saffari M., Griffiths M.D., Pakpour A.H. The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2020;1–9 doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albott C.S., Wozniak J.R., McGlinch B.P., Wall M.H., Gold B.S., Vinogradov S. Battle buddies: Rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2020;131:43–54. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alici N.K., Copur E.O. Anxiety and fear of COVID-19 among nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A descriptive correlation study. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2021;58:141–148. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilay R., Moore T.M., Greenberg D.M., DiDomenico G.E., Brown L.A., White L.K., Gur R.C., Gur R.E. Resilience, COVID-19-related stress, anxiety and depression during the pandemic in a large population enriched for healthcare providers. Translational Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-00982-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baymur F.B. s:275. İnkılap Kitabevi; İstanbul: 2017. Genel psikoloji (26. Baskı) [Google Scholar]

- Berger E., Jamshidi N., Reupert A., Jobson L., Miko A. Review: The mental health implications for children and adolescents impacted by infectious outbreaks - A systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2021;26(2):157–166. doi: 10.1111/camh.12453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L., Stein M.B. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the connor–davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2007;20(6):1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor K.M., Davidson J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) Depression and Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuartero N., Tur A.M. Emotional intelligence, resilience and personality traits neuroticism and extraversion: Predictive capacity in perceived academic efficacy. Nurse Education Today. 2021;102(2021):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104933. 104933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucinotta D., Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis. 2020;91(1):157. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doğan D. Zet Yayınları; Ankara: 2019. SmartPLS ile veri analizi. 89. Sayfa. [Google Scholar]

- Erkuş A., Tabak A. Beş Faktör Kişilik Özelliklerinin Çalışanların Çatışma Yönetim Tarzlarına etkisi: Savunma sanayiinde bir Araştırma. Atatürk Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi. 2010;23(2):213–242. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/atauniiibd/issue/2696/35515 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Eroğlu M. The effect of features of personal features of workig women and factors such as age, education status, income level on psychological resistance levels. International Journal of Primary Education Studies. 2022;3(1):34–42. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ijpes/issue/70020/1048503 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Evren C., Evren B., Dalbudak E., Topcu M., Kutlu N. Measuring anxiety related to COVID-19: A turkish validation study of the coronavirus anxiety scale. Death Studies. 2020;1–7 doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1774969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L.S., Dong Z.J., Yan R.Y., Wu X.Q., Zhang L., Ma J., Zeng Y. Psychological distress in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic: Preliminary development of an assessment scale. Psychiatry Research. 2020;291(2020):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findyartini A., Greviana N., Putera A.M., Sutanto R.L., Saki V.Y., Felaza E. The relationships between resilience and student personal factors in an undergraduate medical program. BMC Medical Education. 2021;21(1):113. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02547-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M., Bäuerle A., Schmidt K., Rheindorf N., Musche V., Dinse H., Moradian S., Weismüller B., Schweda A., Teufel M., Skoda E.M. COVID-19-fear affects current safety behavior mediated by neuroticism-results of a large cross-sectional study in Germany. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.671768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finstad G.L., Giorgi G., Lulli L.G., Pandolfi C., Foti G., León-Perez J.M., Cantero-Sánchez F.J., Mucci N. Resilience, coping strategies and posttraumatic growth in the workplace following COVID-19: A narrative review on the positive aspects of trauma. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(18):9453. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick K.M., Harris C., Drawve G. Fear of COVID-19 and the mental health consequences in America. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(S1):17–21. doi: 10.1037/tra0000924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes A.V., Jacobs R.J., Ip E., Owens R.E., Caballero J. Coping, resilience, and emotional well-being in pharmacy students during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Mental Health Clinician. 2021;11(5):274–278. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2021.09.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundogan S. The mediator role of the fear of COVID-19 in the relationship between psychological resilience and life satisfaction. Current Psychology. 2021;40(12):6291–6299. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01525-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Hult G.T.M., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. 2nd ed. Sage Publications Inc; United States of America: 2017. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J., Ringle C.M., Sinkovics R.R. The use of the partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. New Challenges to International Marketing Advances in International Marketing. 2009;20(1):277–319. doi: 10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horzum M.B., Ayas T., Padır M.A. Beş faktör kişilik ölçeğinin Türk kültürüne uyarlanması adaptation of big five personality traits scale to turkish culture. Sakarya University Journal of Education. 2017;7(2):398–408. doi: 10.19126/suje.298430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karal E., Biçer B.G. Salgın hastalık döneminde algılanan sosyal desteğin bireylerin psikolojik sağlamlığı üzerindeki etkisinin incelenmesi. Birey ve Toplum Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi. 2020;10(1):129–156. doi: 10.20493/birtop.726411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karduz F.F.A., Şar A.H. The effect of psycho-education program on increase the tendency to forgive and five factor personality properties of forgiveness tendency. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies. 2019;6(3):89–105. doi: 10.17220/ijpes.2019.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya B. Pandeminin ruh sağlığına etkileri. Klinik Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2020;23(2):123–124. doi: 10.5505/kpd.2020.64325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya F., Odacı H. Connor-Davidson Psikolojik Sağlamlık Ölçeği Kısa Formu: Türkçe’ye uyarlama, geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. HAYEF: Journal of Education. 2021;18(1):38–54. [Google Scholar]

- Khodabakhshi-koolaee A. Living in home quarantine: Analyzing psychological experiences of college students during Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Military Medicine. 2020;22(2):130–138. doi: 10.30491/JMM.22.2.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kocjan G.Z., Kavčič T., Avsec A. Resilience matters: Explaining the association between personality and psychological functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2021;21(2021):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.08.002. 100198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohút M., Kohútová V., Halama P. Big five predictors of pandemic-related behavior and emotions in the first and second COVID-19 pandemic wave in Slovakia. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;180 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrague L.J., De los Santos J.A.A. COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: Predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. Journal of Nursing Management. 2020;28(7):1653–1661. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladikli N., Bahadir E., Yumuşak F.N., Akkuzu H., Karaman G., Türkkan Z. The reliability and validity of Turkish version of coronavirus anxiety scale. International Journal of Social Science. 2020;3(2):71–80. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/injoss/issue/56160/774887 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Li J.B., Yang A., Dou K., Cheung R. Self-control moderates the association between perceived severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health problems among the Chinese public. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(13):4820. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lü W., Wang Z., Liu Y., Zhang H. Resilience as a mediator between extraversion, neuroticism and happiness, PA and NA. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;63:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Chua C.R., Xiong Z., Ho R.C., Ho C.S. A systematic review of the impact of viral respiratory epidemics on mental health: An implication on the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11:1–21. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.565098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutha S.S., Cicchetti D. The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12(4):857–885. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magal N., Hendler T., Admon R. Is neuroticism really bad for you? Dynamics in personality and limbic reactivity prior to, during and following real-life combat stress. Neurobiology of Stress. 2021;15(2021):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2021.100361. 100361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty E.E., Presskreischer R., Han H., Barry C.L. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and april 2020. JAMA. 2020;324(1):93–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mula S., Di Santo D., Gelfand M.J., Cabras C., Pierro A. The mediational role of desire for cultural tightness on concern with COVID-19 and perceived self-control. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazari N., Safitri S., Usak M., Arabmarkadeh A., Griffiths M.D. Psychometric validation of the ındonesian version of the fear of COVID-19 scale: Personality traits predict the fear of COVID-19. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2021;1–17 doi: 10.1007/s11469-021-00593-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J., VonKorff M., Jeronimus B.F., Riese H. 9-set-point theory and personality development: Reconciliation of a paradox. Personality Development Across the Lifespan. 2017:117–137. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-804674-6.00009-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce M., Hope H., Ford T., Hatch S., Hotopf M., John A., Kontopantelis E., Webb R., Wessely S., McManus S., Abel K.M. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet. Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polatcı S., Tınaz Z.D. The effect of personality traits on psychological resilience abstract. OPUS International Journal of Society Researches. 2021;17(36):2890–2917. [Google Scholar]

- Rammstedt B., John O.P. Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41(1):203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J.E., Holmes H.L., Alquist J.L., Uziel L., Stinnett A.J. Self-controlled responses to COVID-19: Self-control and uncertainty predict responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychology. 2021;1–15 doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02066-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell T., Krampe H. Meaning in life and self-control buffer stress in times of COVID-19: Moderating and mediating effects with regard to mental distress. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.582352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano Sarmiento Á., Sanz Ponce R., González Bertolín A. Resilience and COVID-19. An analysis in university students during confinement. Education Sciences. 2021;11(9):533. doi: 10.3390/educsci11090533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer E.H., Masten C.L., Berkman E.T., Lieberman M.D., Fuligni A.J. Neural regions associated with self control and mentalizing are recruited during prosocial behaviors towards the family. NeuroImage. 2011;58(1):242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torales J., O'Higgins M., Castaldelli-Maia J.M., Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2020;66:317–320. doi: 10.1177/0020764020915212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma P., Junge M., Meaklim H., Jackson M.L. Younger people are more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression during COVID-19 pandemic: A global cross-sectional survey. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2021;109(2021):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., McIntyre R.S., Ho C.… A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;87:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C. A novel approach of consultation on 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID19) related psychological and mental problems: Structured letter therapy. Psychiatry Investigation. 2020;17(2):175–176. doi: 10.30773/pi.2020.0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C.S., Kim Y. Post-traumatic growth during COVID-19: The role of perceived social support, personality, and coping strategies. Healthcare. 2022;10(2):224. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10020224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazıcı Çelebi G. Analysis of the relationship between women’s personality traits and psychological resilience levels. Mavi Atlas. 2021;9(1):132–146. doi: 10.18795/gumusmaviatlas.832657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yorguner N., Bulut N.S., Akvardar Y. COVID-19 salgını sırasında üniversite öğrencilerinin karşılaştığı psikososyal zorlukların ve hastalığa yönelik bilgi, tutum ve davranışlarının incelenmesi. Noro-Psikyatri Arsivi. 2021;58(1):3–10. doi: 10.29399/npa.27503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue J., Zang X., Le Y., An Y. Anxiety, depression and PTSD among children and their parent during 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in China. Current Psychology. 2020;1–8 doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01191-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajenkowski M., Jonason P.K., Leniarska M., Kozakiewicz Z. Who complies with the restrictions to reduce the spread of COVID-19?: Personality and perceptions of the COVID-19 situation. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;166(2020):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110199. 110199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Y., Du X. Addressing collegiate mental health amid COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Research. 2020;288(113003) doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.X., Wang Y., Rauch A., Wei F. Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: Health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Research. 2020;288(112958) doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]