Abstract

We included 852 patients in a prospectively recruiting multicenter matched case-control study in Germany to assess vaccine effectiveness (VE) in preventing COVID-19-associated hospitalization during the Delta-variant dominance. The two-dose VE was 89 % (95 % CI 84–93 %) overall, 79 % in patients with more than two comorbidities and 77 % in adults aged 60–75 years. A third dose increased the VE to more than 93 % in all patient-subgroups.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccine effectiveness, Hospitalization, Case-control study, SARS-CoV-2, Delta

1. Background

In spring 2021, a new variant of concern (VOC), the highly contagious SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant, was identified and gained global dominance by summer 2021. As of August 2021, the weekly incidence in Germany steadily increased, reaching more than 300,000 newly infected persons per week by November 2021. A combination of non-pharmaceutical interventions and a booster vaccination campaign (three vaccine doses) led to decreasing case numbers until the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 took over in 2022 [1].

High efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines has been demonstrated in randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials (73 % for vector vaccines and 85 % for mRNA vaccines in meta-analyses) [2], yet real world data may differ depending on population characteristics and the dominant viral strain during the observation period. In addition, heterologous vaccination schemes i.e. using a vector vaccine for the first and an mRNA vaccine for the second injection, or vice versa, commonly occurred. For booster vaccination, only mRNA vaccines (Comirnaty®, Spikevax®) were recommended in Germany. Furthermore, there is limited data on the duration of protection under the Delta-variant [3], [4], [5].

Early in 2021, we set up a study in 13 hospitals across Germany to analyze the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines in Germany in preventing COVID-19 associated hospitalization in the adult population. In addition, we aimed to perform subgroup analyses for vaccine effectiveness (VE) by age, sex, severity of disease, underlying comorbidities and time since vaccination. Here we present VE results assessed during the Delta-variant wave.

2. Methods

COViK is a prospectively recruiting matched case-control study in Germany that is led by Germany's Public Health Institute (Robert Koch Institute, RKI). Study sites are 13 hospitals in Berlin, Hamburg, Wuppertal, Duesseldorf, Erfurt and Chemnitz. The study was commenced on 1 June 2021 and is expected to end in June 2023.

We here present an interim analysis based on the data of patients recruited from 1 June 2021 until 31 January 2022. A case was defined as an adult aged 18 to 90 years who had a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test and was hospitalized in one of the 13 study hospitals. To be included, cases had to be either hospitalized due to a severe COVID-19 infection or COVID-19 complications, or with a severe nosocomial COVID-19 infection (see supplementary material). Controls were hospitalized patients who were tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR and were recruited at surgical, orthopaedical, urological and gynecological wards, preferably with acute diseases (e.g. fracture, tendon rupture). Two controls per case were recruited from the same hospital that the respective case was admitted to, or, if not available, from a hospital in the same city (1:2 matching). Controls were matched to cases based on their hospital admission date (+/- 14 days), age (+/- 10 years) and sex. All study nurses were trained by the COVIK study centre team regularly. Repeated on-site visits and quality controls were performed to ensure adherence to the study protocol.

Cases and controls with a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection were excluded from the analysis to avoid misclassification (e.g. risk of infection, indication for vaccination; Supplementary Material Table 1).

A current SARS-CoV-2 infection was identified through a positive result of a SARS-CoV-2-real-time PCR performed on a naso-oropharyngeal swab [6]. The virus variant was determined by sequencing using the AmpliCoV protocol [7], or by PCR typing assays if RNA load was too low for sequencing. In addition, antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses were determined and virus-neutralization tests were performed for future immunological analyses.

Data on basic socio-demographic factors (e.g. age, sex, level of graduation), COVID-19 disease (e.g. previous infection, date of symptom onset), COVID-19-vaccination (e.g. vaccination status, vaccine type and number of vaccine doses administered), risk factors for COVID-19 infection and for severe course of disease (e.g. comorbidities) were collected in individual interviews conducted by research nurses. Clinical and laboratory data were extracted from medical records (e.g. sequencing results, admission to an intensive care unit (ICU)). All participants (or their legal guardians) provided a written informed consent to participate in the study.

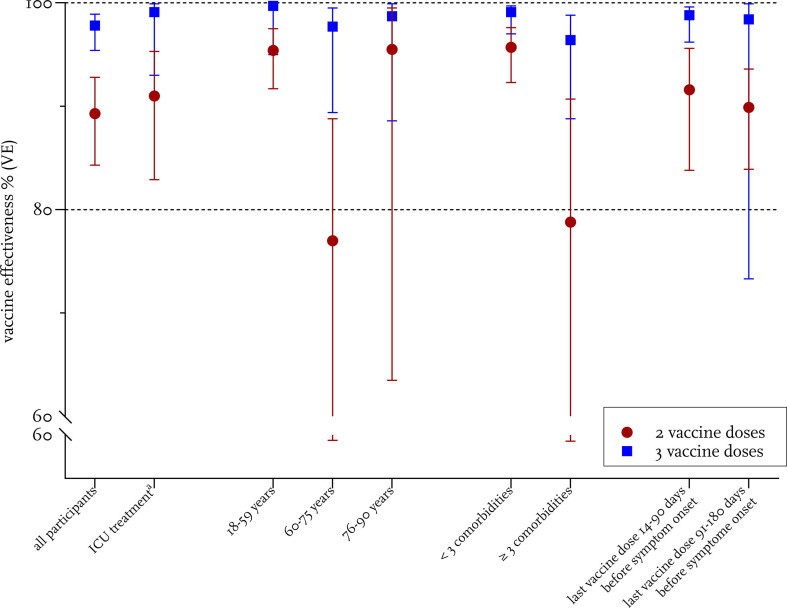

For this first pre-specified interim analysis, we computed the 2-dose and 3-dose VE regardless of the individual matching for the following subgroups: males and females, aged 18–59, 60–75, and 76–90 years, with < 3 or ≥ 3 pre-existing comorbidities, last vaccine dose administered in the past 3 months or 3–6 months ago, admitted to intensive care or not (Fig. 1 , Supplementary Table 3). Patients vaccinated only once were excluded from the analysis of vaccine effectiveness. The analysis was restricted to cases infected with the Alpha or Delta variant.

Fig. 1.

Vaccine effectiveness for two and three vaccination doses, endpoint severe COVID-19 (hospitalization). Vaccine effectiveness for all participants and subgroups is shown. Calculation of VE was performed as described in the Supplementary Methods. aICU treated cases versus controls with no ICU treatment.

Based on logistic regression modeling, we determined VE, adjusted for age, education and pre-existing comorbidities. Variable selection was performed on the basis of predictive accuracy, the AIC and context-related information. Confounder variables taken into consideration were age, age group, comorbidities (general, of the immune system, with high risk for severe course of disease), educational level, sex, region, time period, profession, housing situation, contact to COVID-19 positive persons, activities without mask, self-estimated probability of infection, close contact to persons with high risk for severe course of disease and compliance with infection protection measures; see Supplementary Material).

Comparison of the case and control groups in Supplementary Table 2, was performed with appropriate significance tests (t-tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables; see Supplementary Material).

Data were analyzed using the statistical software R, version 4.1.2.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin (EA1/063/21) and was registered at “Deutsches Register Klinischer Studien” (DRKS00025004).

3. Results

During the study period, 852 participants were recruited, including 244 cases and 608 matched controls.

Median age of cases was 57 years (interquartile range 45–70 years), median age of controls was 59 years (interquartile range 48–72 years), 45 % of cases and 43 % of the controls were female. Cases had a lower education status than controls (42 % of cases vs 28 % of controls with nine or less school years, (p < 0.05)). The majority of the cases was infected with the Delta variant (79 %), and 5 % of them were infected with the Alpha variant (missing information 16 %). Nearly a quarter of the cases (n = 56, 23 %) was admitted to the ICU and 13 patients (5,3 %) deceased (Supplementary Table 2).

Cases were significantly less often vaccinated against COVID-19 than controls: More than half of the cases (58 %, n = 142/244) were not vaccinated at all, compared to 11 % of the controls. Nearly a third (30 %, 73/244) of the cases and more than half of the controls (53 %, 323/608) had received two vaccine doses (first vaccination series) and 9/244 cases (4 %) and 192/316 controls (32 %) had received a third dose (booster dose). Additionally, three controls had received a fourth vaccine dose.

The most frequently administered vaccine among study participants was Comirnaty® (Biontech/Pfizer), 1119 doses, followed by Vaxzevria® (Astra-Zeneca, 151 doses) and Spikevax® (Moderna, 141 doses), while Jcovden® (Johnson& Johnson/Janssen) was administered 28 times.

Without further adjustment, the two-dose VE was 89 % (95 % CI 84–93 %) overall and a third dose increased the VE to more than 93 % in all patient-subgroups (Fig. 1). The VE in the group who received the last vaccine dose three to six month before hospital admission was similar 89.9% (83.9-93.6 % for two doses) and 98.8% (93.3-99.9% for three doses). After adjustment for age, education and pre-existing comorbidities, overall VE (all groups) was 93.5 % (CI 89.1 – 96.2 %) after two vaccine doses and 99.4 % (CI 98.1–99.9 %) for three doses.

VE after two vaccine doses was significantly lower for adults with three or more pre-existing comorbidities as compared to adults with less than three comorbidities (95.7 % vs 78.7 %), while VE after three vaccine doses was similar for both groups (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 3).

The VE was lower among adults aged 60–75 years but this reduction was again compensated when a third dose was administered. When the individual matching of the pairs was considered, similar results were obtained (Supplementary Table 4).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study in Germany that assessed the VE of COVID-19 vaccines in the Delta wave. We decided to use a case control design instead of test negative design because we assumed that recruiting controls with respiratory symptoms would be difficult due to strict infection protection measures (e.g. lock down) and these controls might not be representative, e.g. bedridden patients with endogenous pneumonia due to microaspiration. Furthermore, the advantage of avoiding selection bias for health care seeking, that is important in influenza VE calculations with outpatients, is not as relevant in our study, as the endpoint (hospital admission) is less likely influenced by health care seeking behavior. Our choice of study design is supported by a recent study showing that syndrome-negative and test-negative controls result in comparable VE [8]. Our analysis suggests that the COVID-19-vaccines licensed in the European Union were highly effective in preventing hospitalization due to COVID-19.

The vaccine effectiveness was 93.5 % after two vaccine doses and 99.4 % after three doses. Recently, studies from Canada, the UK and others have reported comparably high VE after two doses against hospitalization [4] with a slow decrease in protection against hospitalization over time. Importantly, waning of protection especially affected clinically vulnerable groups [9]. We found that vaccination protected from severe disease for at least six months, with a VE of 90% for two doses and 99% for three doses.

Patients between 60 and 75 years of age had a significantly reduced two-dose effectiveness. This group benefitted in particular from a third dose. The reduced VE in this group may be due to a weaker immune response upon vaccination compared with younger people but could be also a chance finding as patients older than 75 years showed a higher VE in comparison. Furthermore the comorbidities in the control group (usually surgery) might be documented less carefully compared to the case group (internal medicine). Almost a quarter of our study participants was admitted to an ICU. However, this number may underestimate the ratio of very severe cases as some patients, e.g. elderly people, may refuse ICU treatment.

A main advantage of our study design stems from the ability to collect detailed high-quality information in a prospective manner. Every COVID-19 diagnosis was confirmed by clinical records and -if necessary- by direct consultation of the attending physician. Only patients requiring hospitalization due to COVID-19 were included. Many post-deployment studies rely on clinical data registries, resulting in fast reporting which is valuable to guide policy decisions during a pandemic. However, not all patients are included in such registries and their main diagnosis may not be COVID-19. Unlike many other studies, we explicitly examined the pre-existing immunity by serology early in the course of infection and excluded all participants with pre-existing antibodies or with a previous laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. The detailed verification leads to a better data quality: With relying on patient’s information only we would have excluded six patients due to previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, the antibody test revealed 24 further cases. Participants with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection were excluded from the analysis to avoid a biased analysis as previous infections potentially prevent subsequent infections and vaccination was not recommended at least for three months after SARS-CoV-2 infection in Germany. Furthermore, we determined the virus variant for each patient.

A limitation of our study is the low number of participants. We could not gain precise results for matched pairs and triplet analysis for some subgroups for this reason. A potential source of bias might be a higher likeliness of study participation for vaccinated patients. Here, we took countermeasures such as incentivation and we recorded the response rates of cases and controls and reasons for non-participation. No bias was visible when comparing cases and controls. We will continue to carefully assess this as unvaccinated persons may form a special group in settings of high vaccination coverage. This first interim analysis provides encouraging results and warrants follow-up analyses to assess the evolving COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness, in a changing epidemiologic landscape in terms of circulating variants, available vaccines, and increasing population-wide immunity. In the future course of the study, we plan to analyze the Omicron wave, combinations of natural infection and vaccination, longer time intervals since vaccination, long-term COVID-19 symptoms in vaccinated vs unvaccinated individuals (long COVID), and the immune response after COVID-19 breakthrough infections.

5. Conclusion

The COVID-19 vaccines were highly protective against hospitalization in real-world settings in Germany during the Delta-variant predominance. Reduced vaccine effectiveness observed in subgroups after two doses was compensated after three doses. This finding would support efforts to maximize vaccine uptake to three doses among vulnerable populations.

6. Funding

This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Health [2520COR416].

7. Meetings where this study has been previously presented.

-

1.

Joint Annual Meeting DZIF/DGI 2022, June 1-3, 2022, Stuttgart, Germany.

-

2.

7. Nationale Impfkonferenz, June 14-15, 2022, Wiesbaden, Germany.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: S. G. received payment/honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche Pharma and Berlin Chemie, this had no influence on this work; all other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all study nurses for the valuable contribution, namely Sawsanh Al-Ogaidi, Nancy Beetz, Belgin Esen, Rola Khalife, Marie-Kristin Kusnierz, Katja Lange, Luise Mauer, Antje Micheel, Marlies Schmidt, Yvonne Weis, Franziska Weiser, Aysete Yencilek. We thank Wiebke Hellenbrand for her important contribution in designing and setting up the study as well as Anna Meier, Swetlana Muminow, Richard Schensar, Ellen Busch, Hanna Buck, and Moritz Gehring for their support in organizing the project and Vincent Stoliaroff-Pépin for support with R.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.11.065.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Robert-Koch-Institute. Wöchentlicher Lagebericht des RKI zur Coronavirus-Krankheit-2019 (COVID-19). 2022; Available from: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Situationsberichte/Wochenbericht/Wochenberichte_Tab.html.

- 2.Sharif N., et al. Efficacy, Immunogenicity and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.714170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skowronski D.M., et al. Two-dose SARS-CoV-2 vaccine effectiveness with mixed schedules and extended dosing intervals: test-negative design studies from British Columbia and Quebec. Canada Clin Infect Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feikin D.R., et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet. 2022;399(10328):924–944. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00152-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahumud R.A., et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 Vaccines against Delta Variant (B.1.617.2): A Meta-Analysis. Vaccines (Basel) 2022;10(2) doi: 10.3390/vaccines10020277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michel J., et al. Resource-efficient internally controlled in-house real-time PCR detection of SARS-CoV-2. Virol J. 2021;18(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12985-021-01559-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinkmann A., et al. AmpliCoV: Rapid Whole-Genome Sequencing Using Multiplex PCR Amplification and Real-Time Oxford Nanopore MinION Sequencing Enables Rapid Variant Identification of SARS-CoV-2. Front Microbiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.651151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turbyfill C., et al. Comparison of test-negative and syndrome-negative controls in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine effectiveness evaluations for preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations in the United States. Vaccine. 2022;40(48):6979–6986. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrews N., et al. Duration of Protection against Mild and Severe Disease by Covid-19 Vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):340–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2115481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.