Abstract

Aim

The aim of this study was to explore key informants’ views on and experiences with Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy in a Dublin community with a high concentration of economic and social disadvantage and to identify feasible, community-centred solutions for improving vaccination acceptance and uptake.

Methods

Qualitative, semi-structured interviews were carried out at a local community-centre and a central hair salon. Twelve key informants from the target community were selected based on their professional experience with vulnerable population groups: the unemployed, adults in recovery from addiction, the elderly, and Irish Travellers. Inductive thematic framework analysis was conducted to identify emergent themes and sub-themes.

Results

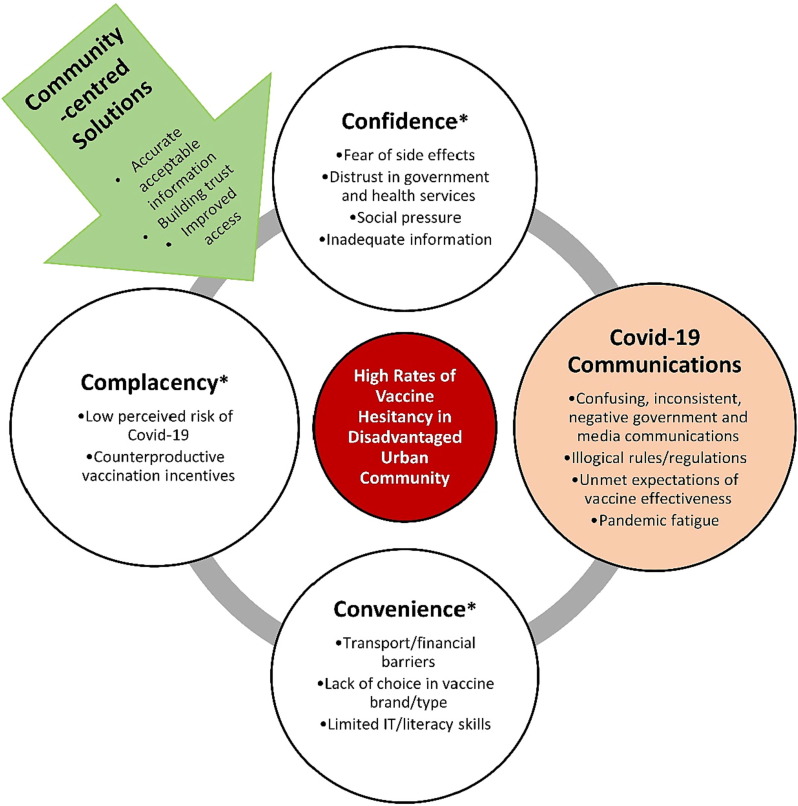

Drivers of vaccine hesitancy identified by key informants largely fell under the WHO ‘3Cs’ model of hesitancy: lack of confidence in the vaccine and its providers, complacency towards the health risks of Covid-19, and inconvenient access conditions. Covid-19 Communications emerged as a fourth ‘C’ whereby unclear and negative messages, confusing public health measures, and unmet expectations of the vaccine’s effectiveness exacerbated anti-authority sentiments and vaccine scepticism during the pandemic. Community-specific solutions involve the provision of accurate and accessible information, collaborating with community-based organizations to build trust in the vaccine through relationship building and ongoing dialogue, and ensuring acceptable access conditions.

Conclusions

The proposed Confidence, Complacency, Convenience, Covid-19 Communications (‘4Cs’) model provides a tool for considering vaccine hesitancy in disadvantaged urban communities reacting to the rapid development and distribution of a novel vaccine. The model and in-depth key informants’ perspectives can be used to compliment equitable vaccination efforts currently underway by public health agencies and non-governmental organizations.

Keywords: Covid-19, Vaccine hesitancy, Hesitancy drivers, Qualitative, Low-SES community, Socioeconomic disadvantage

1. Introduction

Vaccine hesitancy refers to delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services. It is complex and context specific, varies across time, place and vaccines, and is influenced by factors such as complacency, convenience and confidence [1]. Though not a new phenomenon [2], a variety of factors have fuelled an increase in Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy specifically, including concerns about rapid production and use of new messenger RNA (mRNA) technology and potential side effects [3]; the propagation of misinformation and disinformation on social media [4]; disapproval of Covid-19 mitigation measures implemented by the government [5]; and confusion about natural immunity, vaccine effectiveness and the need for repeat vaccination [6], [7], [8]. Resulting hesitancy or refusal to be vaccinated can and does have dire consequences. Covid-19 mortality over a 2-year period is up to eight times higher in populations with high vaccine hesitancy compared to those with an ideal vaccination uptake [9]. An individual who is fully vaccinated with a messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine is up to 90 % less likely to get infected [10], 94 % less likely to be hospitalized [11], and 90 % less likely to die from Covid-19 [12].

Concentrated disadvantage – the phenomenon of spatial clustering of economically or socially disadvantaged individuals within a set of neighbourhoods and the resulting feedback effects that exacerbate the problems of poverty and poor health [13] – is associated with vaccine hesitancy [14]. Individual predisposing and behavioural factors intersect with place-based economic, social and health inequalities and hinder vaccination willingness and uptake [15], [16], resulting in that the communities most vulnerable to Covid-19 are more likely to have low vaccination coverage [14], [15]. Vaccine hesitancy may be particularly consequential in urban settings where factors such as overcrowded housing, large numbers of essential workers, and exposure to air pollution increase residents’ risk of Covid-19 infection and severe outcomes [17], [18], [19], [20]. Experts have called for the prioritisation of densely populated deprived areas during Covid-19 vaccination rollout [21]. However, ensuring equitable vaccination first requires understanding and addressing challenges associated with vaccination willingness and uptake in disadvantaged urban communities [22].

In the Republic of Ireland, 91 % of the eligible population were fully vaccinated for Covid-19 as of January 2022, and 56 % had received a booster vaccine [23]. Nevertheless, an estimated third of the adult population had experienced some Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy, and 9 % were opposed to the vaccine, with trends in resistance steadily increasing as the pandemic progressed [24], [25]. As reported internationally, adults in Ireland who are vaccine hesitant are more likely to live in urban settings and be in a lower income bracket [24], the same areas at increased risk for Covid-19 incidence and comorbidities [21].

Interventions to address vaccine hesitancy are most successful if they are based on empirical data and situational assessment, and adapted to a specific target group in a culturally sensitive manner [26]. Preliminary findings on the drivers of Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy in Ireland show that national trends match those found internationally [24], [26]: vaccine hesitant individuals in Ireland are more likely to have conspiracy beliefs; lower levels of trust in scientists, health care professionals, and the state; and to consume significantly less information from formal information sources and more from social media [24]. Nevertheless, at the onset of the national Covid-19 booster campaign, lower reported vaccination coverage in Irish urban centres [27] highlighted a need to consult disadvantaged urban community residents on local drivers of vaccine hesitancy in order to tailor the design and rollout of interventions to those disproportionately at risk of declining a highly effective vaccine [28].

The aim of this study was to explore key informants’ views on and experiences with Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy in a Dublin community with a high concentration of economic and social disadvantage and to identify feasible, community-centred solutions for improving vaccination acceptance and uptake. Key informants were individuals from the target community working with population groups identified as disproportionately vulnerable to Covid-19: the socioeconomically disadvantaged and/or unemployed, adults in recovery from addiction, the elderly, and Irish Travellers, an indigenous ethnic minority group [29].

2. Methods

2.1. Defining the target community

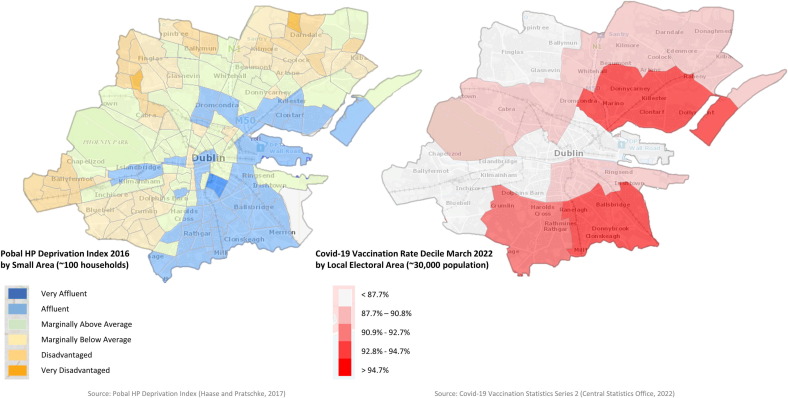

We used an area-based approach to identify a densely populated, disadvantaged Dublin community with low relative rates of vaccination (Fig. 1 ). In Ireland, area deprivation is measured by the 2016 Pobal HP Deprivation Index which considers three dimensions of affluence/disadvantage: demographic profile (e.g., population loss, social and demographic effects of emigration), social class composition (e.g., social class composition, education, housing quality), and labour market situation (e.g., unemployment, lone parents, low skills base) [30]. Each Small Area (SA) – the smallest spatial units for which population data is available in Ireland (∼100 households) – receives a Relative Index Score ranging from ‘Very Affluent’ to ‘Very Disadvantaged’. Our target community was a cluster of eight ‘Disadvantaged’ SAs with below average rates of vaccination as of autumn 2021 constituting a population of approximately 30,000. The eight SAs, hereinafter referred to as the target community, are linked by a central community partnership organization charged with implementing government-funded Social Inclusion and Community Activation Programmes [31]. Our research team met with representatives from this organization in September 2021 who confirmed lingering hesitancy towards the Covid-19 vaccine in the target community and the need to better understand and address its drivers

Fig. 1.

Comparison of Pobal HP Deprivation Index 2016 rankings and Covid-19 Vaccination Rates by national decile as of March 2022 in Dublin, Ireland. Note: The target community is a cluster of eight ‘Disadvantaged’ Small Areas (SA) within a Local Electoral Area (LEA) in the lowest decile for national vaccination rates. In Ireland, Covid-19 vaccination rates are not publicly available in spatial units smaller than LEAs.

The target community is also home to a high concentration of population subgroups experiencing social disadvantage as a result of a particular theme or issue which is common between them (e.g., Irish Travellers, low-income workers, the unemployed, adults in recovery from addiction). We sought to explore the barriers to vaccination specific to diverse groups served by the community partnership organization, as well as how place-based vulnerabilities shared across the target community (i.e., poverty, hardship, and social exclusion) related to vaccine hesitancy.

2.2. Study design and setting

Qualitative, semi-structured interviews were carried out in collaboration with (1) the community partnership organization that addresses long-term unemployment and poverty through education and social inclusion initiatives, and (2) a long-standing hair salon located on the target community’s main road. These specific collaborations were formed to enhance understanding of vaccine hesitancy through community-based organizational representatives’ knowledge of local social and cultural dynamics [32], and the fact that clients regularly disclose information about health and identity to hairdressers [33]. A semi-structured interview format was selected to allow participants to freely express themselves while providing reliable, comparable data [34]. The study’s qualitative methodology was preregistered on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/n5jch).

2.3. Sample and recruitment

A non-probability purposive sampling method was used to identify potential key informants from the two partnering organizations that met the following criteria: knowledge of and experience with community vaccine hesitancy based on their professional role and having lived and/or grown up in the target community; ability to communicate that knowledge to the researchers; and willingness to take part in the study [35], [36]. To ensure diversity of opinion, key informants of various ages, genders, and occupational roles were selected.

Prior to participant recruitment, the researchers met with managers of the respective establishments to introduce themselves and explain the study objectives. After agreeing to the research collaboration, managers identified and invited eligible staff members to participate in semi-structured interviews. A first round of twelve in-depth interviews were scheduled and completed, at which point the researchers found that no new information relevant to the study objectives was emerging and data saturation was achieved [37].

2.4. Data collection

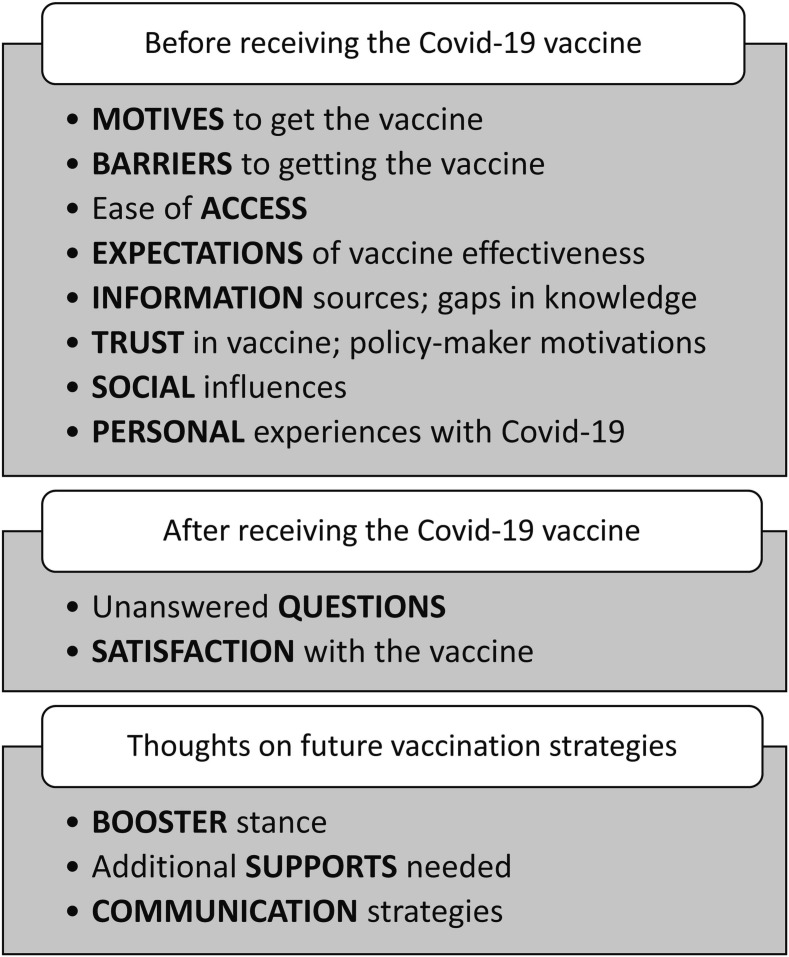

Semi-structured interviews were conducted at the hair salon on 17 September 2021, and at the community partnership on 19 November 2021, in private rooms provided by management. Interviewers had formal qualitative research training (CI, MR) and were accompanied by an undergraduate research intern from the local community acting as a liaison between the researchers and collaborating organizations (LP). Participants were presented with an information sheet and gave informed oral consent in the full knowledge that interviews would be audio recorded, transcribed, and anonymized as approved by the researchers’ institutional Human Research Ethics Committee (UCD-HREC-LS-E-21–222). Interviews lasted around 20 min and followed a set of research questions developed through consultation with community representatives and review of existing literature on Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy in Ireland [24], [29]. Both individual and community perspectives were sought on (1) attitudes towards the vaccine, (2) thoughts on the current pandemic situation given widespread first-round vaccinations, and (3) attitudes towards the booster (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Covid-19 vaccine topics included in the semi-structured interview guide. Note: key informants were asked about their own perceptions and experiences as well as those of the wider community.

2.5. Data analysis

Data were coded and analysed using an inductive thematic framework method according to the following recommended stages of trustworthy, thematic analysis [38], [39]:

-

•

Transcription: Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by two researchers (CI, VD).

-

•

Familiarisation: Two researchers (CI,VD) familiarized themselves with the data by re-listening to audio recordings and re-reading the transcripts. Each researcher recorded analytical notes, thoughts, and impressions in the transcript margins.

-

•

Initial coding: The same researchers independently coded three transcripts line by line, identifying potential themes and subthemes relating to vaccine hesitancy through an ‘open coding’ process. Once results were compared and an initial coding framework constructed, CI completed line by line open coding of the remaining nine transcripts. This allowed for further revision before the research team met to discuss, refine, and agree to a working thematic framework. During peer debriefing, researchers recognized that key themes largely fell under the World Health Organization’s (WHO) ‘3Cs’ model of vaccine hesitancy [26]. Thus, determinants of hesitancy were re-categorized under Confidence, Complacency, Convenience and – unique from the WHO model – Covid-19 Communications and Community-Centred Solutions, as defined in Fig. 3 .

-

•

Applying the thematic framework: The working thematic framework was systematically applied to all transcripts by CI using Nvivo software V.11. Overlapping themes were combined, and necessary refinements made until three layers of distinct themes were finalized and approved by all researchers.

-

•

Charting and interpreting the data: A matrix was used to summarize data for each participant, code, and theme. Connections within and between codes and cases were made in order to fulfil the original research objectives and highlight findings generated through inductive analysis.

Fig. 3.

‘4Cs’ Model of Covid-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in a disadvantaged urban community: inductive analysis results from key informant interviews, Dublin, Ireland 2021. *From the WHO SAGE Working Group 3Cs model of Vaccine Hesitancy [26]. Covid-19 Communications emerged through inductive analysis as a separate theme driving hesitancy.

3. Results

3.1. Key informant demographics and personal views on the vaccine

The study sample (n = 12) was made up of three key informants from a central hair salon and nine from a local community centre including: two guidance counsellors for adults in recovery from addiction, three working with job seekers and/or those on social welfare, one community health officer working with the local Irish Traveller population, two administrators, and one centre manager. Key informants’ characteristics and their personal stances on Covid-19 vaccination and booster shots are described in Table 1 . Five key informants were completely accepting of Covid-19 vaccines, citing motivators such as personal safety and that of loved ones, returning to normalcy and going on holidays, and being adequately informed. Of the seven key informants who experienced little to great vaccine hesitancy, fear of side effects, especially in the case of underlying health conditions, and guilt at receiving the vaccine before those more vulnerable were the most-cited barriers. Only two key informants were entirely accepting of the booster shot. Those who were resistant (n = 5) were largely discouraged by unmet expectations of vaccine efficacy.

Table 1.

Key informant characteristics and stances on the Covid-19 vaccine and booster shot: Dublin, Ireland, 2021.

| Key Informant ID | Key Informant Employment | Age | Gender | Vaccine Received | Stance on Vaccine | Explanation | Stance on Booster | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hair Salon 1 | Hairdresser in a centrally located salon | 30–39 | F | Pfizer | No hesitancy | F: Watching other, older people go first without bad side effects. | N/A | |

| Hair Salon 2 | Hairdresser in a centrally located salon | 50–59 | F | Pfizer | No hesitancy | F: Wanted to get back to work. Everybody else was doing it. | N/A | |

| Hair Salon 3 | Hairdresser in a centrally located salon | 50–59 | F | Pfizer | Some hesitancy |

B: Worried about reaction with underlying health condition. F: Found information online, at vaccination centre. |

N/A | |

| Adults in Recovery 1 | One-on-one education, guidance, and support for adults in recovery from alcohol or substance abuse | 40–49 | M | Astra Zeneca | Some hesitancy | B: Worried about reaction with underlying health condition. Unanswered questions. | Unsure |

B: Not as fearful of Covid as before. F: Will get the booster if it’s an organizational policy. |

| Management 1 | Manages team providing business services, education supports, pre-employment and personal development courses, and health programs for Travellers | 30–39 | F | Astra Zeneca | Little hesitancy |

B: Guilt at receiving vaccine before those more vulnerable. F: Personal safety as a front facing worker. |

No hesitancy | F: Best way out of Covid in the long term. |

| Employment Services 1 | Guidance counsellor for job seekers and those on social welfare | 20–29 | M | Astra Zeneca | No hesitancy | F: Safety of older parents. Going on holidays. | Some hesitancy | B: People with underlying health conditions should have first access. |

| Community Health Officer 1 | Promotes health services within local Traveller community | 20–29 | F | Pfizer | Some hesitancy |

B: Fear of side effects. Lack of information. F: Going on holidays. Reduced risk of severe infection. |

Great hesitancy |

B: Fatigue. “How many times do we have to keep doing it, you know?” |

| Employment Services 2 | Guidance counsellor for job seekers and those on social welfare | 40–49 | F | Astra Zeneca | No hesitancy | F: Return to normalcy. Personal safety as front facing worker. | N/A | |

| Admin 1 | Front facing community center employee | 40–49 | F | Pfizer | Great hesitancy |

B: Unanswered questions. Inability to make an informed decision. F: Paid to meet with a GP and got desired info. |

Great hesitancy |

B: Unmet expectations of vaccine effectiveness. |

| Adults in Recovery 2 | One-on-one education, guidance, and support for adults in recovery from alcohol or substance abuse | 20–29 | F | Pfizer | Some hesitancy |

B: Fear of side effects. F: No reports of allergic reactions in the news or through HSE. |

No hesitancy | F: Trusts the science and government intentions. |

| Employment Services 3 | Guidance counsellor for job seekers and those on social welfare | 40–49 | M | Astra Zeneca | No hesitancy | F: Return to normalcy. Safety of children. | N/A | |

| Admin 2 | Community centre receptionist | 30–39 | F | Astra Zeneca | Some hesitancy |

B: Belief that others deserved to go first. F: Needed access to hospital services. Obtention of vaccine passport. |

Great hesitancy | B: Unmet expectations. Belief that the booster will do no good. |

*B = barrier. F = facilitator. GP = general practitioner.

3.2. Community context

Key informants believed community Covid-19 vaccination rates to be in line with national rates at the time of data collection (∼90 % of the eligible population). Though the local population was broadly accepting of the vaccine, participants noted “very strong anti-vaccination feelings in a small number of people” (Management 1). Two participants commented on a pattern of resistance whereby ‘anti-vaxxers’ tended to be ‘anti-maskers’ and harbour conspiracy beliefs.

Stances on the vaccine varied by population group. Middle-aged and older clients of the hair salon were “very happy to get it done [and] get back out” (Hair Salon 2 and 3). Attitudes of unemployed community centre clients met “an absolute extreme on both sides, and in the middle” (Employment Services 3), though Employment Services 2 found that many clients who “moaned” about the vaccine still got it eventually. A genuine resistance was noted amongst community centre clients in recovery from addiction; whereas in the Traveller community, vaccine acceptance was possible under the right conditions (e.g., Pfizer instead of Johnson and Johnson vaccine, seeing others be vaccinated first, increased convenience for everyday life, the disease being “on the doorstep”).

3.3. The 4Cs

In the following sections, we focus on four main themes explaining Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy in the disadvantaged Dublin community. The first three – Confidence, Complacency, Convenience – are in line with the WHO ‘3Cs’ model of Vaccine Hesitancy [26]. A separate theme of Covid-19 Communications emerged through inductive analysis to explain local hesitancy, as did Community-Centred strategies for improving vaccination willingness and uptake. Sample quotes for each theme and sub-theme are presented in Table 2 . Because key informants are themselves members of the target community, reported results integrate their insights into community perceptions of the vaccine with their own vaccination experiences.

Table 2.

Key informants’ perceptions on drivers of Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy in a disadvantaged Dublin community by theme and sub-theme.

| Theme/Sub-theme | Sample Quote(s) |

|---|---|

| Confidence | |

| Fear of side effects | |

| Novelty, speed of development | “There's a bit of hesitancy towards it amongst some of the clients that I would have encountered. They would have kind of been like, ‘Oh, I'm not getting a vaccine that's after coming around that fast. I wouldn't know what they're going to be putting into our bodies.’” (Employment Services 2) |

| Underlying health conditions | “My daughter wasn't going to get it because she was a bit concerned 'cause she's epileptic.” (Hair Salon 2) “I have asthma and obviously we’re all aware of the difficulty of respiratory illness or whatever, so, I wanted to kind of see would that impact me in any way.” (Adults in Recovery 1) |

| Close proximity to negative vaccination experience | “I mean the odds were so low. But I suppose it’s been such an unusual couple of years that I think anxiety levels are probably heightened anyway. Then a good few had very bad side effects the day after so that didn’t help matters either.” (Management 1, speaking on Ireland’s pause of the AstraZeneca jab in March 2021 following reporting of blood clots) |

| Cultural norms | “For Traveller women, being infertile was a huge concern because a Traveller woman sees her life made when she’s married and has children. There’s a lot of women in the local Traveller community that aren’t vaccinated as a result and trying to talk them out of that is very difficult. Very, very difficult.” (Community Health Officer 1) |

| Distrust in government and health services | |

| Feeling like the world is against you | “They just think it's all a big scam. You know, we work in a disadvantaged area and there's a lot of people that have grown up feeling that the world is against them, that the government is against them. So, they already have that kind of mentality and mindset and are very easily swayed as to go against the grain while they're living in disadvantage and poverty.” (Employment Services 3) |

| Fear of conspiracy | “An article came out from the government saying that they’re gonna vaccinate homeless people and Travellers with Johnson & Johnson vaccine because it’s more practical for people that move around. Very common sense, but this was seen as an ethnic cleansing. That’s basically the way they saw it. Then a public figure came out and said ‘they’re trying to get rid of us Travellers’ and it was a nightmare trying to debunk that. The only thing we could do was offer other vaccines.” (Community Health Officer 1) |

| Social pressure | |

| Community pressure | “At the time it was Pfizer that was being given out [instead of Johnson and Johnson] and a lot of other people ended up jumping on. But there's a huge secrecy around it. You know, you’re standing in the garden and getting called in on the side, ‘Hey, can you get me a vaccine? But don’t tell anyone. I don’t want people knowing that I took it.’ So, I think in that kind of mob mentality, people are afraid to say, ‘No, actually, I did take it and I’m grand.’ That’s what we’re dealing with a lot.” (Community Health Officer 1) |

| Family pressure | “There was a family I was working with where the son wanted it but his Mam was completely anti-vaxx so he felt like he couldn't get it because he'd be going against her.” (Community Health Officer 1) |

| Inadequate information | |

| Exposure to misinformation | “I don’t think people are coming at it from a negative perspective necessarily. I think they’re getting bad information. And it’s making them very, very anxious and worried.” (Management 1) |

| Lack of accurate information (individual) | “I had a lot of questions that I wanted answered and they weren't answered, so I wasn't going to actually go and have something that I didn't know what I was dealing with.” (Admin 1) “I contacted my GP who was very unwilling to give me information and directed me to the HSE website… but specific information around my asthma was not there. I actually had to go on Google the NHS website and find out more information.” (Adults in Recovery 1) |

| Lack of accurate information (GP) | “I was having a conversation with people yesterday who were asking ‘Why would we have to get a third, like that's ridiculous.’ I was just saying it wears off, it's probably not as effective, you know. That's the only reason I can give people at the minute as a healthcare worker because I really don't know myself to be honest.” (Community Health Officer 1) “I don’t know why my GP was reluctant to give information. My own opinion is that there’s a lack of knowledge on their end as well. I don’t think they had the answers.” (Adults in Recovery 1) |

| Complacency | |

| Low perceived risk of Covid-19 | |

| Lack of first-hand experience with severe Covid-19 | “There was quite high incidence of Covid in [this community] at one stage, so I think generally they could have maybe known a lot of people that would have had Covid. But maybe the people that they knew weren't in hospital… so it could be based on a little bit of that. Because the people that they knew didn't have bad symptoms. Therefore, they feel that they don't need a vaccine to protect them from Covid.” (Employment Services 1) “[The local Traveller community] hasn’t been hugely impacted by Covid. There’s been one or two people that had it. One person was in hospital but a few days later was out standing in his garden. I think it’s just not taken seriously, whereas there was an outbreak of Hepatitis, and it was affecting children. So, there was an immediate response at the time. People were petrified.” (Community Health Officer 1, explaining high community uptake of hepatitis vaccine) |

| Feeling less at-risk than others | “I wouldn't be in a rush to get [the booster] because I feel like there is other like more vulnerable people that would benefit from it probably more than me.” (Employment Services 1) |

| Reduced fear over time | “For me the fear of Covid, it’s kind of, I’m not as fearful as I would have been maybe in April May, June of 2020. So, would take the booster if I had an option? If It was an organizational policy and I had to get it, I would get it.“ (Admin 2) |

| Counterproductive vaccination incentives | |

| Resistance to vaccine passports | “They might have missed the boat on [motivating people to be vaccinated]. You know, like the flu jab came out every year and you’d say to your friend, ‘Are you getting the jab? No? Grand.’ Every-one moves on, nobody is penalized. Where now this roll out is pushed in people’s faces, like they can’t go to McDonald’s. They can’t go and have a meal because they don’t have the Covid cert. So, I don’t think we can turn it around.” (Admin 2) |

| Prioritizing freedom of choice | “I do feel it is a little bit forced. Like, I know you still have an option whether to get it or not, but it restricts you a lot if you don't get it. I think it has to be, at this point, it has to be personal responsibility anyway. I don't think they should be telling us what to do.” (Admin 2) |

| Unsuitable, divisive incentives | “There are people who don't need a [vaccine certificate]. There are people out there who probably will not travel because they don't have the means. They don’t have the luxury of going on holiday or to a foreign country. We're a certain kind of cohort of the population that needs this certificate to function in daily life. We need it go for a meal, as I said, but there are people out there who don’t need it. Then for people that don't work, there's no incentive, there's no pressure for them to get [the vaccine], you know…Some of those people have already got health complications as well. So, they're saying to themselves, ‘well, I’ll be fine.’“ (Employment Services 1) “I think they’ve managed it very poorly with the Covid passports. I mean, there’s a 2-tier society going on, you know, and I think that pisses people off more than brings people with. You need to bring people with you, rather than get two sides kind of fighting against each other.” (Employment Services 3) |

| Convenience | |

| Access barriers | |

| Transport/financial barriers | “My mother is a family support worker with the HSE. One of the families she goes to is a lady that is on her own with four or five children, so she wouldn’t have the means for a car or anything like that. And one of her children actually had symptoms of Covid and the GP had suggested that they get her to go to [the HSE testing and vaccination centre] to have the child tested. Now, first of all, she has children that she couldn’t get minded. Her only means of getting to [the centre] was through a taxi. You know, she didn’t have the money for that.” (Admin 1) |

| Lack of access to preferred vaccine | “I know within this population there was a lot of like discourse over the right vaccine to get. One individual didn’t want the Astra Zeneca, just straight up refused to get vaccinated up until a couple weeks ago where he could actually go in and get Pfizer.“ (Adults in Recovery 1) |

| Lack of IT/literary skills | “I see a lot of clients that don’t have good literacy or IT skills, so they might not have the skills to go online and register on the vaccine portal, like a lot of older members of the community.” (Employment Services 1) |

| Communications | |

| Communications breakdown | |

| Mixed messages | “There's too many leaders saying too many different things. If they got one person to speak… I find they were saying different things throughout Covid, and that was confusing, especially a lot of the older people were very confused.” (Hair Salon 3) |

| Confusing statistics | “You know, NPHET is supposed to be the backbone of the pandemic. And I'm sorry but the muppet show… And I don't mean to be smart, I know they're well-educated men but, you know, the statistics and stuff they put up, a lot of people wouldn't get what that means.” (Admin 1) |

| Overreporting of case numbers | “People do watch the news and have radios on and all they’re hearing is case numbers. And I think that’s a massive problem because they’re not seeing any improvement. They’re just saying, ‘What’s the point?’ and I don’t blame them.” (Employment Services 2) |

| Lack of encouragement | “You ask any old person what they do on a daily basis. Sit down with their cup of tea and watch the 6o'clock news, and they've been like that for 40–50 years. And there was all this information that didn't necessarily need to be [communicated] to them. Where information on how well people were doing on the vaccine, or how the vaccine was going to help people, or you know the benefits of it, didn't happen, unfortunately.” (Admin 1) |

| Illogical rules and regulations | |

| Public health measures without explanation | “Closing nightclubs at 12:00o'clock when they only open at 11. Does Covid only come out at 12:01? All this stuff drives me bloody crazy. Like all these rules make no sense. You could go to a pub last year and you could stay there if you bought a meal because the meal saved you from COVID. Like it's just crazy, none of it makes sense.” (Admin 2) |

| Disjointed approach | “You've so many different stakeholders, my impression of it is that they're trying to please every-one and achieving nothing, you know, and I think that comes out in the communications. I just don't think there is a singular vision for how we’re going to get out of this. Or perhaps there is, but it's just not coming across, you know, so I think that's really damaging…I think if we do get it to a point where we have to reintroduce restrictions or anything like that, I think they’ll really struggle with it this time around.“ (Management 1) |

| Unmet expectations | |

| Sense that the vaccine doesn’t work | “I suppose they've always been telling us 'get as many people vaccinated as possible’ and now, I think over 90 % the population over 16 is vaccinated and obviously the case numbers are spiking again. So, it’s frustrating and I think probably for the people that were hesitant about getting a vaccine in the first place, it's maybe adding to their suspicions or concerns about it now that they see that all these people are vaccinated but they're still getting Covid, and the case numbers are still going up.” (Employment Services 1) |

| Being sold the wrong story | “I just think that perceptions were kind of wrong. People thought that the vaccine was going to stop people getting the virus, which it actually doesn't. It just stops people getting really sick from the virus and I'm not sure that message was put across properly.” (Employment Services 2) |

| Scepticism stemming from false hope | “How many times were we told, ‘two weeks to flatten the curve’? And, ‘just another two weeks’? It's been a while now at this stage and it's hasn’t flattened. So, I think there is probably a sense that maybe people don't know what they're doing at government level… I think it's harder to convince people to make sacrifices in their own lives when they don't actually feel like it's really going to have an impact.” (Management 1) |

| Pandemic fatigue | |

| Wanting to move on | “I think it's a lot more difficult this time with the boosters, 'cause we were sold a story that we'd be grand once we're all vaccinated, and we're not. So, it is going to be harder. People are Covid-fatigued, and just tired after the last few years. I think it will be hard enough to hit the numbers that we need. But, I mean, just keep a consistent message I think would be a good way forward.” (Management 1) |

*HSE = Health Service Executive Ireland. NHS = National Health Service England.

3.4. Confidence

“There’s probably-two reasons why people are hesitant. One: being genuinely afraid of putting something into their body, and two: being anti-establishment.” (Employment Services 2).

3.4.1. Fear of side effects

Participants acknowledged that lack of trust in the effectiveness and safety of vaccines, and lack of trust in the system and authorities that deliver them were primary drivers of hesitancy in the community. Fear surrounding the vaccine’s safety stemmed from how “fast” (Adults in Recovery 1, Employment Services 1) it was rolled out, and its perceived “trial” status (Hair Salon 1). Safety concerns were heightened in individuals with underlying health conditions and those who witnessed and/or heard reports of serious side effects. In the Traveller community, fear of infertility was a concern amongst women due to the cultural weight placed on having a family.

3.4.2. Distrust in government and health services

Anti-establishment sentiments and distrust in government and health services stemming from economic disadvantage further impeded Covid-19 vaccine uptake. Key informants working in employment services noted that clients felt “left behind”, “angry” (Employment Services 2), “poorly treated by government departments”, and that “the government doesn’t care” (Employment Services 3). Though some clients simply needed space to “rant” (Employment Services 2) before getting vaccinated, for others, the consequences of “paranoia” and “lack of trust in the government” (Adults in Recovery 2) were further reaching. Some would not engage with health services as a result or did not have a good relationship with their general practitioner (GP). A history of social inequities and poor community health outcomes left clients feeling that a vaccine wasn’t “gonna change much” (Employment Services 3).

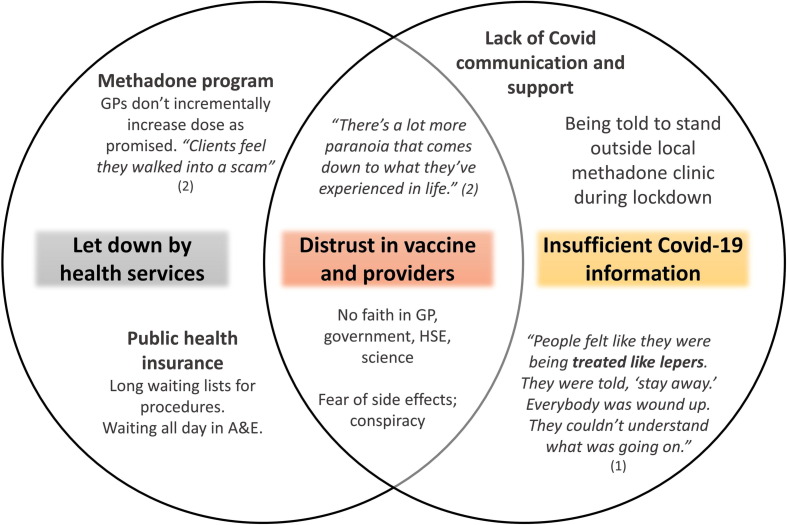

Combining anecdotes from Adults in Recovery 1 and 2, a picture emerges of how a history of being let down by health services compiled with lack of information on Covid-19 has created distrust towards the vaccine and its providers amongst former drug users (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Drivers of vaccine resistance amongst adults in recovery from drug addiction as reported by community centre Guidance Counsellors (1) and (2): 19 November 2021, Dublin. *GP = General Practitioner. A&E = Accident and emergency department. HSE = Health Service Executive Ireland.

In some instances, distrust went as far as to instil fear of conspiracy. Hair salon 2 and 3 both heard rumours circulating in the community of microchip injections, noting a “genuine fear” (Hair salon 3). Community Health Officer 1 outlined the extent to which local Travellers feared malicious intent: the single dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine, prioritised over two dose vaccines for vulnerable groups to support efficiency and coverage in complex environments [29], was believed to be a means of ethnic cleansing.

3.4.3. Social pressure

When describing fears circulating in the Traveller community, Community Health Officer 1 spoke of a tendency towards “mob mentality.” Travellers based their vaccination stance on that of trusted community leaders who spoke out against the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. Those who disagreed were afraid to speak out against popular opinion. The phenomenon of “jumping on the bandwagon” to be “outwardly against something” was observed by Employment Services 3, crediting the tendency for negative stories to gather more weight than positive stories. This type of social pressure affected families. Three participants mentioned instances of a parent discouraging their adolescent child to be vaccinated: two participants heard of adult children discouraging elderly parents.

3.4.4. Inadequate information

Five participants emphasized the role that misinformation spread via social media and word-of-mouth played in fuelling fears of side effects and conspiracy. They noted that community members may lack the resources to challenge misinformation shared by trusted personal contacts. Participants themselves found it difficult to debunk rumours and make informed decisions due to a lack of accessible, accurate information. Adults in Recovery 1 and Admin 1 found no information on the Health Service Executive Ireland (HSE) website on how the vaccine would react with their underlying health conditions and turned to their GPs for answers. Adults in Recovery 1 never got an appointment: Admin 1 paid 60€ for one. Even healthcare professionals lacked adequate information. Community Health Officer 1 never received specific training on Covid-19 as part of their healthcare role, relying on independent research and, in some instances, “literally just assuming.”

3.5. Complacency

“People have relaxed a little bit and I don’t think there’s that same sense of life and death that was there very early on.” (Management 1).

3.5.1. Low perceived Covid-19 risk

Complacency refers to factors supporting a view that the risks of Covid-19 are low, and vaccination is not considered a necessary preventive action. Employment Services 1 explained that low perceived risk manifested in the community early in the pandemic because most people had experienced and/or witnessed only mild cases of Covid-19. Conversely, participants noted how a first-hand experience with severe Covid-19 or other illness amplified perception of risk and increased vaccination uptake. Four participants thought their personal level of risk did not merit receiving the Covid-19 vaccine before other more vulnerable people, expressing guilt at going before those who needed it more.

Participants felt that fear of Covid-19 had waned over the course of the pandemic, acknowledging that people “weren’t scared anymore” (Admin 2), had grown “complacent” (Management 1), and “were just getting on with it” (Admin 2).

3.5.2. Counterproductive vaccination incentives

The theme of complacency emerged indirectly in attitudes towards the vaccine that implied low perceived risk of the virus. At the time of data collection, a vaccine certificate (i.e., proof of full vaccination or recovery from Covid-19) was required for indoor hospitality and events, and for most international travel [40]. The restrictions led many community members to be vaccinated out of social or professional convenience rather than as a necessary preventive action.

Participants highlighted potential push back from those who disagreed with restrictions for the unvaccinated, emphasizing people’s right to and preference for making their own medical decisions. Of five participants who mentioned feeling pressurized to get the vaccine either through work or in order to avoid restrictions, none were planning on getting a booster shot at the time of data collection. For many, with fear of Covid-19 waning over time, upholding freedom of choice took precedence over worries about the virus and its health consequences.

Relying on non-health related incentives for Covid-19 vaccination may also inadvertently discourage immunization in disadvantaged community members who are frustrated by divisive social and occupational restrictions.

3.6. Convenience

“Her only means of getting to [the vaccination centre] was through a taxi. You know, she didn't have the money for that.” (Admin 1).

3.6.1. Access barriers

At the time of data collection, the closest HSE vaccination centre was located approximately 20 min on public transport from the local area. This could pose a challenge for elderly people who remained “nervous about getting on a bus” (Hair salon 3), and/or for those without the financial means for a taxi or to have children minded. Some community members were unable to access their preferred vaccine; others had trouble registering for an appointment online due to limited IT and/or literacy skills.

Community Health Officer 1 spoke of a one-day mass vaccination campaign initiated for the local Traveller community. Beyond this, participants were unaware of vaccination campaigns being brought to the local area.

3.7. Covid-19 Communications

“There’s hostility and fear there because of the lack of communication, and lack of support, and a lack of trying to get people to understand what’s going on here, why this is happening.” (Adults in Recovery 1).

3.7.1. Communications breakdown

While identified subthemes generally fell under the WHO 3cs framework for vaccine hesitancy, a separate theme emerged relating to government and media communications. Participants shared a view that communication failures reinforced local vaccine hesitancy during the pandemic. A breakdown of communication was described whereby “mixed messages”, “lack of clarity” (Employment Services 3), and “contradictions” (Community Health Officer 1) from the government and media led to “hostility”, “fear” (Adults in Recovery 1) and “damaged trust” (Management 1) in the community. Contradictory messages from multiple leaders, and the tendency to use big words and statistics were confusing for local community members.

Participants attributed some of the communications breakdown to the pandemic’s increasing complexity over time and the dilution of accurate messages due to the quantity of false information on social media. Nevertheless, they felt that unsatisfactory government and media communications, particularly the overreporting of case numbers and lack of encouraging vaccination updates, further deterred vaccine hesitant individuals from seeking out immunization.

3.7.2. Illogical rules and regulations

More than half of participants were frustrated by a sense that some public health measures – for example, a closing time of midnight instead of 2am for all on-licensed premises in November 2021 and a requirement that pubs serve a meal of the value of €9 per customer in order to reopen in June 2020 – “made no sense.” (Admin 2). The lack of clarity behind specific approaches “planted seeds in people’s heads” (Admin 1) that they needn’t follow restrictions. One participant made a direct connection between diminished trust in the government’s ability to lead due to confusing regulations and struggling to get every-one “on board” (Admin 1) with vaccination.

3.7.3. Unmet expectations of vaccine effectiveness

Unsatisfactory communications also led to unmet expectations of the vaccine’s effectiveness. Ten of twelve participants believed that the pandemic situation would be under control once vaccinations were rolled out and expressed disappointment that case numbers were rising at the time of data collection. Participants described how confusion, frustration, and anger due to perceived lack of effectiveness of the vaccine led to the entrenchment of community scepticism. For those who had been initially accepting of the vaccine, unmet expectations contributed to Covid-19 booster resistance as participants and community members were left with a feeling of, “what’s the point?” (Adults in Recovery 2, Admin 2).

Examples of miscommunications that led to disillusionment with the vaccine included selling the vaccine as preventive against all Covid-19 infection, rather than severe Covid-19 infection, and creating false hope by continuously reassuring the population that things would improve in “just another few weeks.” (Hair salon 1).

3.7.4. Pandemic fatigue

The culmination of unmet expectations, confusing regulations, and a general breakdown of communication was a sense of community-wide fatigue. Participants described a sense of “apathy” (Admin 1), being “fed up” (Employment Services 1), and “wanting to move on” (Admin 2) with the pandemic. These sentiments had negative implications for the local booster campaign. Some community members that had their two vaccinations felt they had “done their duty” (Admin 1) and weren’t having any more.

3.8. Community-centred solutions

3.8.1. Providing accurate, accessible information

To establish confidence in the vaccine and address complacency, participants underlined the importance of providing communities with “the right information to make an informed choice” (Employment Services 2) through conversation and upscaled Covid-19 information resources.

Recommended information providers varied by population group. Generally, participants found that conversations with health professionals can “put minds at ease” (Hair Salon 3). For the elderly, public health nurses and community registered general nurses providing in-home care were identified as effective providers of Covid-19 information. For populations with distrust in health professionals, “it would be useful to appoint someone independent with a scientific background to a Covid response role where they go around to different community centres and answer peoples’ questions.” (Adults in Recovery 2).

Setting up information stands, providing leaflets at the local chemist, implementing a Covid-19 helpline, and – for the digitally literate – conducting informational zoom meetings, webinars, and podcasts in understandable language came up as feasible ways to improve local knowledge and acceptance of the vaccine.

3.8.2. Building trust in the vaccine and its providers

Participants suggested bringing regular Covid-19 question and answer sessions and vaccine campaigns into the community via trusted community-based organizations like youth groups and medical charities. Specific trust-building techniques emerged through inductive analysis:

-

•

Ongoing dialogue: “Bringing people together to ask questions and get answers” (Management 1) and “having conversations about initial concerns or reservations in [understandable language].” (Employment Services 1)

-

•

Relationship building: “Building a rapport with people who may feel backed into a corner and are used to fighting” (Employment Services 3) by “identifying specific goals”, shifting from a “one-size-fits-all” approach to address individual concerns, and “actively listening” (Adults in Recovery 1).

-

•

Erasing preconceptions: “Becoming familiar with vaccine concerns” (Employment Services 1), “being empathetic”, “not talking [down] to people that are not vaccinated” (Management 1), and “understanding it’s a process, that you can’t flip a switch” (Employment Services 3).

-

•

Communicating effectively: “Providing real evidence to debunk misinformation” (Adults in Recovery 1), and “letting [community members] know what you’re aiming for, how you’re trying to do it, and being honest and upfront” (Employment Services 3).

3.8.3. Improving vaccine access

Along with upscaling local vaccination campaigns and awareness efforts, participants recommended “being more inclusive of communities where general and digital literacy are an issue” (Employment Services 1). Providing marginalized community groups (i.e., Travellers, adults in recovery from addiction) with a choice of vaccine and facilitating private vaccination requests to overcome social pressure and vaccine stigmatization could also improve vaccine uptake.

To reduce viral transmission and, by slowing the spread of Covid-19 in the local community, improve perceptions of the vaccine’s effectiveness, two participants suggested simultaneously expanding access to affordable antigen tests.

4. Discussion

This qualitative study was the first to examine drivers of Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy in Ireland through consultation with community representatives. While results confirmed that drivers of hesitancy in a disadvantaged urban community largely fell under the WHO Confidence, Complacency, Convenience model [26], the Irish government and media’s handling of Covid-19 communications emerged as a novel barrier to vaccination acceptance and uptake. Prior to Covid-19 vaccination roll-out in Ireland, Murphy et al. (2021) suggested that public health messaging should be clear, direct, repeated, and positively orientated to target the psychological characteristics of those prone to vaccine hesitance or resistance [24]. Our study outlines how pandemic communications missed these objectives, contributing to the entrenchment of anti-authority sentiments and offering one explanation for increased resistance to Covid-19 vaccination in Ireland during the pandemic [25].

While vaccine-safety related concerns have been identified as the main determinant of vaccine hesitancy in Europe and the UK [41], [42], key informants identified anti-established sentiments stemming from a history of being let down by the government and health services as a primary local challenge. Barriers to vaccination uptake specific to adults in recovery from addiction were foreshadowed in a 2019 review on methadone treatment protocol in Ireland [43]. Service users described negative program aspects including patient lack of choice, humiliating experiences consuming methadone in a public space, engaging with uncaring service providers, and being treated with a one size fits all approach [43]; all identified in this study as drivers of Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy. Complacency may also prevent uptake in this group. The primary barrier to vaccination amongst 872 surveyed people who inject drugs in Australia was lack of perceived vaccine utility [44]. Identified barriers to Covid-19 vaccine uptake amongst Irish Travellers (e.g., cultural concerns about vaccines offered during pregnancy, misinformation spread via social media and ‘word of mouth’) have been cited in relation to other vaccines, as have potential facilitators including sufficient understanding of the vaccine and trust in health professionals [45]. The reported negative reaction of the Traveller community towards receiving a single rather than double dose Covid-19 vaccine underlines the importance of applying key informants’ recommendations for trust-building (e.g. ongoing dialogue, erasing pre-conceptions) before the implementation of well-intentioned public health measures, as well as after.

Participants expressed negative community sentiments and resistance towards non-health related vaccination incentives and ‘being told what to do’. This is in line with findings from a UK study demonstrating that vaccine passports may induce a lower vaccination inclination in socio-demographic groups that are less confident in Covid-19 vaccines [46]. Social and professional restrictions make those who already intend to get vaccinated even more inclined to do so, potentially explaining surges in vaccination following implementation of a national vaccine passport policy [46], [47]. But research shows, as do our own study findings, that pressurizing those with doubts about the vaccine to vaccinate reinforces resistance, particularly for those who are economically deprived and/or unemployed [46]. Prioritisation of education and outreach initiatives to combat vaccine scepticism and misinformation emerges as a better-suited strategy for encouraging vaccination in disadvantaged communities.

Encouragingly, results from this study confirm the effectiveness of many strategies already used by the HSE and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) for ensuring equitable vaccination in Ireland. The HSE’s comprehensive vaccine approach for vulnerable groups, including Travellers and those in addiction settings, recommends a hands-on approach using trusted sources within each population group to listen, alleviate individual concerns, and encourage vaccine participation [29]. Our study findings suggest that this type of ‘champion’ – or someone with a scientific background appointed to a Covid response role, as suggested by one key informant – would be of value at the wider community level in disadvantaged areas. Vaccine communication plans for vulnerable groups are in progress at the HSE, who has called for targeted approaches for meeting information needs [29]. Key informants’ perspectives can again be of value: strategies like Q&A sessions with scientists, healthcare professionals and community representatives that facilitate relationship building and ongoing dialogue should be prioritized. GPs, pharmacists, and community health care workers working with disadvantaged populations should receive additional training on Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness and potential side effects, and on how to communicate this knowledge effectively and empathetically to individuals with limited trust and/or health literacy.

Irish NGOs are leading crucial community-level vaccination initiatives in collaboration with the HSE. Pavee Point, an NGO addressing Traveller issues and promoting Traveller rights, has an online ‘Travellers Take the Vaccine’ page with community member video testimonies addressing many of the vaccine fears and concerns outlined in this research study and linking viewers with the HSE website and vaccine helpline [49]. The medical charity Safetynet’s Covid Cluster Rapid Response Teams facilitate pop-up testing, vaccination, and health promotion clinics. Coordinating outreach and communication between federal, state, and local partners such as these will enhance trust in the national vaccination strategy and prevent the breakdown of communication described by key informants [50]. Expanding access to tailored Covid-19 information resources – local helplines, leaflets in familiar language, information sessions conducted in community centres— can ensure that members of disadvantaged communities who are prone to vaccine scepticism understand what makes the vaccine safe and protective. The success of expanded vaccine information efforts will require bolstering trust in the government’s ability to lead during this and future pandemics. Considerations include accompanying new public health measures with clear explanations of the scientific rational behind them; creating realistic expectations of vaccine effectiveness; and expanding access to supplementary preventive resources like antigen tests in disadvantaged communities. During ongoing and future public health crises, communications from government and health officials should not be overly reassuring or foster false illusions of certainty that further erode trust.

4.1. Public health implications

The proposed ‘4Cs’ model of Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy provides a tool for considering vaccine hesitancy in disadvantaged urban areas in Ireland in the context of Covid-19 and future pandemics requiring the rapid development and distribution of a novel vaccine. The model can be tested, adapted, and validated in comparative sites nationally and internationally, particularly in high-income countries experiencing community-level Covid-19 vaccine disparities and stalled booster campaigns (e.g., United States, United Kingdom, France). Validation within specific marginalised communities at risk of vaccine hesitancy will also be important (e.g., individuals experiencing homelessness, people with disabilities, ethnic minority groups, migrants).

Study findings demonstrate a need for transparent and targeted communication about first-round and repeated Covid-19 vaccination at the local and national level. Whilst overcoming Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy is critical for ensuring that vulnerable communities are adequately protected from the ongoing pandemic and its consequences, preventing future vaccine inequalities and related health disparities will require addressing the systemic neglect and marginalisation experienced by economically and socially disadvantaged individuals. As one small step in this process, our research team aims to conduct community-based participatory research with this study’s target community to facilitate ongoing dialogue on priority health needs and to strengthen relationships between health care providers, researchers, and marginalised community members.

4.2. Limits

This study holds potential for information bias as the views of key informants regarding community perceptions on vaccine hesitancy may be influenced by their own experiences with and feelings toward the Covid-19 vaccine. As well, a relatively small number of key informants were interviewed to represent all vulnerable population groups in the community. Nevertheless, the fact that testimonies were similar enough across participants to achieve data saturation after a first round of interviews, and that identified community drivers of hesitancy closely reflected findings from international research efforts [26] confirm the internal and external validity of the study.

5. Conclusion

This qualitative study was the first to gather empirical evidence on Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy in a disadvantaged urban community in Ireland. A Confidence, Complacency, Convenience, Communications (‘4Cs’) model of Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy emerged through inductive analysis of key informant interviews. While many drivers of hesitancy in the disadvantaged Dublin community fell under the WHO ‘3Cs’ model, Covid-19 Communications emerged as a separate theme whereby unclear messages, confusing public health measures and unmet expectations of the vaccine’s effectiveness entrenched vaccine scepticism and distrust in the government’s ability to lead during the pandemic. Community-centred strategies for improving information resources, rebuilding trust, and expanding vaccine access were identified by key informants. The emergent ‘4Cs’ model of hesitancy provides key insights and strategies for tackling vaccine hesitancy in disadvantaged urban communities and can be used to compliment equitable vaccination efforts currently underway by public health agencies and NGOs.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Carolyn Ingram: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Mark Roe: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Vicky Downey: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Lauren Phipps: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Carla Perrotta: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to management and staff of the collaborating community partnership organization and hair salon, without whom this research project would not have been possible.

Funding

This work was supported by Science Foundation Ireland [grant number 20/COV/8539].

Ethical approval

Informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all participants. All participants were 18 years of age or older. All methods were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved for exemption from full ethical review by the University College Dublin Human Research Ethics Committee – [Sciences (HREC-LS)]. Research Ethics Exemption Reference Number (REERN): UCD-HREC-LS-E-21-222-Perrotta

Data availability

The authors do not have permission to share data.

References

- 1.MacDonald N.E. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33:4161–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riedel S. Edward Jenner and the History of Smallpox and Vaccination. Baylor University Medical Center Proc. 2005;18:21–25. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leong C., Jin L., Kim D., Kim J., Teo Y.Y., Ho T.-H. Assessing the impact of novelty and conformity on hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccines using mRNA technology. Commun Med. 2022;2:1–6. doi: 10.1038/s43856-022-00123-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mascherini M., Nivakoski S. Social media use and vaccine hesitancy in the European Union. Vaccine. 2022;40:2215–2225. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weitzer J., Birmann B.M., Steffelbauer I., Bertau M., Zenk L., Caniglia G., et al. Willingness to receive an annual COVID-19 booster vaccine in the German-speaking D-A-CH region in Europe: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Regional Health – Europe. 2022:18. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg Y., Mandel M., Bar-On Y.M., Bodenheimer O., Freedman L., Haas E.J., et al. Waning Immunity after the BNT162b2 Vaccine in Israel. N Engl J Med. 2021;385 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2114228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhong D., Xiao S., Debes A.K., Egbert E.R., Caturegli P., Colantuoni E., et al. Durability of antibody levels after vaccination with mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in individuals with or without prior infection. JAMA. 2021;326:2524–2526. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.19996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrews N., Stowe J., Kirsebom F., Toffa S., Sachdeva R., Gower C., et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 booster vaccines against COVID-19-related symptoms, hospitalization and death in England. Nat Med. 2022;28:831–837. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01699-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imperial College London. Report 43 - Quantifying the impact of vaccine hesitancy in prolonging the need for Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions to control the COVID-19 pandemic. 2021.

- 10.Thompson MG. Interim Estimates of Vaccine Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 Vaccines in Preventing SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among Health Care Personnel, First Responders, and Other Essential and Frontline Workers — Eight U.S. Locations, December 2020–March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Tenforde MW. Effectiveness of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna Vaccines Against COVID-19 Among Hospitalized Adults Aged ≥65 Years — United States, January–March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7018e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Sheikh A., Robertson C., Taylor B. BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine effectiveness against death from the delta variant. NEJM. 2021;385:2195–2197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2113864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jargowsky PA, Tursi NO. Concentrated Disadvantage. In: Wright JD, editor. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd Ed. Oxford: Elsevier; 2015, p. 525–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.32192-4.

- 14.Crane M.A., Faden R.R., Romley J.A. Disparities in county COVID-19 vaccination rates linked to disadvantage and hesitancy. Health Aff (Millwood) 2021;40:1792–1796. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bucyibaruta G., Blangiardo M., Konstantinoudis G. Community-level characteristics of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in England: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s10654-022-00905-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaughan C.H., Razieh C., Khunti K., Banerjee A., Chudasama Y.V., Davies M.J., et al. COVID-19 vaccination uptake amongst ethnic minority communities in England: a linked study exploring the drivers of differential vaccination rates. J Public Health. 2022:fdab400. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ingram C., Min E., Seto E., Cummings B., Farquhar S. Cumulative Impacts and COVID-19: implications for low-income, minoritized, and health-compromised communities in King County, WA. J Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01063-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen L.M., Harden S.R., Sugg M.M., Runkle J.D., Lundquist T.E. Analyzing the spatial determinants of local Covid-19 transmission in the United States. Sci Total Environ. 2021;754 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulu H., Dorey P. Infection rates from Covid-19 in Great Britain by geographical units: a model-based estimation from mortality data. Health Place. 2021;67 doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh B, Redmond P, ESRI, Roantree B, ESRI. Differences in risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19 across occupations in Ireland. ESRI; 2020. https://doi.org/10.26504/sustat93.

- 21.Madden J.M., More S., Teljeur C., Gleeson J., Walsh C., McGrath G. Population mobility trends, deprivation index and the spatio-temporal spread of coronavirus disease 2019 in Ireland. Int J Environ. 2021;18:6285. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webb Hooper M., Nápoles A.M., Pérez-Stable E.J. No populations left behind: vaccine hesitancy and equitable diffusion of effective COVID-19 vaccines. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2130–2133. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06698-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Government of Ireland, Ordnance Survey Ireland. Vaccinations 2020. https://covid-19.geohive.ie/pages/vaccinations (accessed January 8, 2022).

- 24.Murphy J., Vallières F., Bentall R.P., Shevlin M., McBride O., Hartman T.K., et al. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat Commun. 2021;12:29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20226-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hyland P., Vallières F., Shevlin M., Bentall R.P., McKay R., Hartman T.K., et al. Resistance to COVID-19 vaccination has increased in Ireland and the United Kingdom during the pandemic. Public Health. 2021;195:54–56. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. 2014.

- 27.Central Statistics Office. COVID-19 Vaccination Statistics Series 2. https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/fp/fp-cvac/covid-19vaccinationstatisticsseries2/ (accessed October 3, 2022).

- 28.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Catalogue of interventions addressing vaccine hesitancy. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2017.

- 29.Fitzgerald D.M., McKenna J.-A. HSE Vaccine Approach for Vulnerable Groups in Ireland. Health Services Ireland. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haase T., Pratschke J. The 2016 Pobal HP Deprivation Index for Small Areas (SA) Pobal. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Department of Rural and Community Development. Social Inclusion & Community Activation Programme Requirements 2018-2022. 2017.

- 32.Israel B.A., Schulz A.J., Parker E.A., Becker A.B. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Page S.M., Chur-Hansen A., Delfabbro P.H. Hairdressers as a source of social support: a qualitative study on client disclosures from Australian hairdressers’ perspectives. Health Soc Care Community. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Semi-structured Interviews 2008. http://www.qualres.org/HomeSemi-3629.html (accessed June 29, 2021).

- 35.Palinkas L.A., Horwitz S.M., Green C.A., Wisdom J.P., Duan N., Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42:533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marshall M.N. The key informant technique. Fam Pract. 1996;13:92–97. doi: 10.1093/fampra/13.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bradley E.H., Curry L.A., Devers K.J. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gale N.K., Heath G., Cameron E., Rashid S., Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nowell L.S., Norris J.M., White D.E., Moules N.J. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16:1–13. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Department of the Taoiseach, Department of Health. Public health measures in place right now 2021. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/3361b-public-health-updates/ (accessed January 8, 2022).

- 41.Adel Ali K., Pastore Celentano L. Addressing vaccine hesitancy in the “Post-Truth” Era. Eurohealth. 2017;23:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freeman D., Loe B.S., Chadwick A., Vaccari C., Waite F., Rosebrock L., et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol Med. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delargy I., Crowley D., Van Hout M.C. Twenty years of the methadone treatment protocol in Ireland: reflections on the role of general practice. Harm Reduct J. 2019;16:5. doi: 10.1186/s12954-018-0272-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Price O., Dietze P., Sullivan S.G., Salom C., Peacock A. Uptake, barriers and correlates of influenza vaccination among people who inject drugs in Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;226 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jackson C., Dyson L., Bedford H., Cheater F.M., Condon L., Crocker A., et al. UnderstaNding uptake of Immunisations in TravellIng aNd Gypsy communities (UNITING) A qualitative interview study. Health Technol Assess Rep. 2016;20:1–176. doi: 10.3310/hta20720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Figueiredo A., Larson H.J., Reicher S.D. The potential impact of vaccine passports on inclination to accept COVID-19 vaccinations in the United Kingdom: Evidence from a large cross-sectional survey and modeling study. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;40 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGarvey E. Covid-19: Irish vaccine passports “accelerated” jab uptake. BBC News. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pavee Point. Travellers Take the Vaccine 2021. https://www.paveepoint.ie/travellers-take-the-vaccine/ (accessed January 11, 2022).

- 50.Hunter C.M., Chou W.-Y.S., Webb Hooper M. Behavioral and social science in support of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: National Institutes of Health initiatives. Transl Behav Med. 2021;11:1354–1358. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibab067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.