Abstract

We searched a database of single-gene knockout (KO) mice produced by the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC) to identify candidate ciliopathy genes. We first screened for phenotypes in mouse lines with both ocular and renal or reproductive trait abnormalities. The STRING protein interaction tool was used to identify interactions between known cilia gene products and those encoded by the genes in individual knockout mouse strains in order to generate a list of “candidate ciliopathy genes.” From this list, 32 genes encoded proteins predicted to interact with known ciliopathy proteins. Of these, 25 had no previously described roles in ciliary pathobiology. Histological and morphological evidence of phenotypes found in ciliopathies in knockout mouse lines are presented as examples (genes Abi2, Wdr62, Ap4e1, Dync1li1, and Prkab1). Phenotyping data and descriptions generated on IMPC mouse line are useful for mechanistic studies, target discovery, rare disease diagnosis, and preclinical therapeutic development trials. Here we demonstrate the effective use of the IMPC phenotype data to uncover genes with no previous role in ciliary biology, which may be clinically relevant for identification of novel disease genes implicated in ciliopathies.

Subject terms: Cell biology, Organelles, Molecular medicine, Ciliogenesis

Introduction

The pathophysiology of ciliopathies reflects abnormalities in the function of both primary and motile cilia. Primary cilia dyskinesia (PCD) is a multi-syndromic disorder caused by defects in motile cilia, including chronic otosinopulmonary disease, situs abnormalities, and male infertility. PCD results from an inability of motile cilia to transport mucus through the respiratory tract and nasal sinuses resulting in persistent infection1. Situs abnormalities are characterized by lack of normal left–right axis asymmetry. Within the embryonic node there are monociliated cells that beat, moving extracellular fluid and morphogens in order to establish normal left–right axis asymmetry. These developmental abnormalities are also a result of altered cilia motility2. Male infertility is caused by an abnormal flagellum, itself a modified motile cilia, that affects the progressive and non-progressive motility of sperm3,4. Male infertility can also be caused by loss of motile ciliary action within the efferent ductules of the testes and/or the ciliated epithelial lining of efferent epididymal ductules that are responsible for moving spermatozoa to the epididymis for final maturation5.

Two hallmark features of abnormal structure and function of primary cilia include aberrant kidney function and retinal degeneration6. Each renal tubular epithelial cell contains a single primary cilium that can act in mechano- and chemo-sensation. Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) and nephronophthisis (NPHP) are diseases in which normal renal architecture is replaced by cysts caused by abnormalities in the primary cilium of renal epithelial cells7. Mutations of proteins that are components of the primary cilium, for example PKD1, PKD2, and PKHD1, are associated with PKD, while mutations of the ciliary proteins NPHP1 and INVS are associated with NPHP6.

Ciliopathies that commonly have symptoms of retinal degeneration include Leber Congenital Amaurosis (LCA), NPHP, Senior-Loken Syndrome (SLS), Joubert Syndrome (JBTS), and Bardet–Biedl Syndrome (BBS)8. While single gene mutations exist that are unique to each syndrome, several syndromes can share a single genetic basis. For example, CEP290 has been linked to NPHP, BBS, SLS, and JBTS8–12. CEP290 is a known centrosomal protein that is found in renal epithelial cells and retinal photoreceptors13. Outside of retinal and renal phenotypes, skeletal anomalies such as polydactyly can also develop as is the case with the ciliopathy Meckel–Gruber syndrome (MGS)14. The clinical spectrum of ciliopathies can include hydrocephalus, intellectual disability, craniofacial defects, cardiac anomalies, lung disease, skeletal abnormalities, liver and pancreatic cysts, kidney disease, and reduced or total infertility.

Considerable effort has been directed toward understanding the scope of proteins interacting with cilia, both directly and through secondary protein interactions, in order to more fully understand potential disease causing mutations that encompass ciliopathies15–17. These studies have shed light on new disease-causing or disease-contributing genes associated with ciliopathies15–17. However, in the discovery of such genes it is useful to validate predicted ciliopathy proteins or interacting proteins in an in vivo model system. Knockout mice that express a null “loss of function” allele for a gene can determine if mutations in predicted genes lead to the expected phenotype and are useful diagnostically in clinical cases of human ciliopathies, including forms of pediatric ophthalmic pathology.

The International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC) is a mouse and phenotype data resource for single gene knockout (KO) mouse lines. Since its inception it has expanded to 20 research centers with expertise in high throughput KO mouse production and phenotyping18. To date, production and comprehensive phenotyping has been completed for 6,440 unique genes in IMPC data release 11.0 queried 29 April 2020. Cohorts of KO mice (at least 7 female and 7 male mice per gene) are analyzed and studied using a sequential set of phenotyping tests starting at 4 weeks of age and a set of terminal tests at 16 weeks of age that includes necropsy, tissue collection, and histology using standardized protocols19,20. Standardization and harmonization of testing protocols and data analysis are performed by the IMPC Data Coordination Center (DCC) to identify and confirm phenodeviants21,22. Given the characteristic presentation of ciliopathies with functional or morphological abnormalities in eyes, kidneys, and reproductive tract, we queried the IMPC database for all mouse lines with abnormal ocular traits and at least one other ciliopathy-associated system: renal or reproductive.

We present novel genes in KO mouse lines that exhibit phenotypes consistent with ciliopathies. Further, we present evidence indicating how loss-of-function mutations in these genes are related to the dysfunction of primary or motile cilia. Candidate ciliopathy genes presented here are of potential interest for further investigation of their association to the cilium and to confirm their association with clinical ciliopathies, particularly those responsible for pediatric eye disease.

Results

Query of the IMPC database for abnormal traits associated with ciliopathies

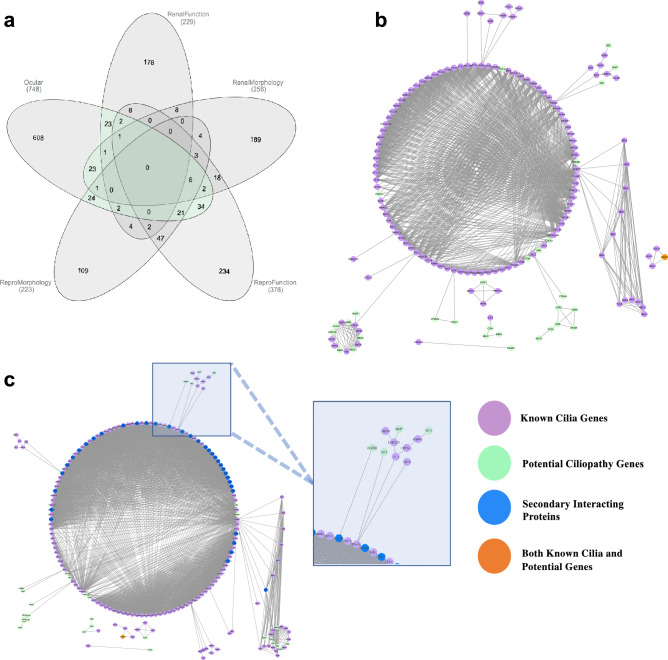

The IMPC database contained KOs for 748 genes which exhibited abnormal ocular phenotype(s) identified by eye examination, optic imaging, and/or histopathology (“ocular genes”). Of these, 256 demonstrated abnormal renal morphology at necropsy (“kidney morphology genes”). 132 had abnormal values for blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and 110 had abnormal plasma creatinine (CRE); collectively (“renal function genes”). Of the total 229 renal function genes, 13 were found to have altered levels of both BUN and CRE. Abnormal reproductive tract morphology was identified at necropsy and/or histopathology (“reproductive morphology genes”) in 223 lines. Abnormal reproductive phenotypes was identified by fertility analysis (“reproductive function genes”) in 378 lines. These groups are summarized in Fig. 1a.

Figure 1.

Identification of potential ciliopathy genes and protein network interactions of potential ciliopathy genes and known ciliopathy proteins. (a) Venn diagram showing intersection of IMPC genes associated with various phenotype subgroups, those highlighted in green outline have ocular and one or more other concomitant renal or reproductive trait abnormality and are subsequently considered “Potential ciliopathy genes” (b) STRING interaction map of known ciliopathy genes with potential ciliopathy genes. Proteins are shown as nodes on the map where green is indicative of a potential ciliopathy gene, purple shown known or gold standard ciliopathy genes, orange are those that were identified to be potential ciliopathy genes and are previously known as ciliopathy genes. Each line represents a STRING interaction score of greater than or equal to .9 based on 5 pieces of evidence: “experiments,” “databases,” “co-expression,” “neighborhood,” “gene fusion,” and “co-occurrence.” 24 of the 140 potential ciliopathy genes are shown to be directly interacting with known ciliopathy genes. (c) Incorporation of additional proteins or nodes into the network where blue nodes are genes not found in either gold standard or potential ciliopathy genes. Highlighted is an interacting oculorenal gene WDR62 which is predicted to interact with known ciliopathy genes through an additional protein CEP63.

Identification of potential ciliopathy genes

Query of the IMPC database for five different categories of traits associated with ciliopathies led to five distinct gene sets: “ocular genes”, “kidney morphology genes”, “kidney function genes”, “reproductive tract morphology genes”, and “reproductive tract function genes”. To identify “potential ciliopathy genes” with a particular focus on those associated with congenital blindness syndromes, all “kidney morphology genes”, “kidney function genes”, “reproductive tract morphology genes”, and “reproductive tract function genes” were then assessed for concomitant ocular trait abnormalities. If a line had one ocular and any renal or reproductive system abnormality then it was considered to be a “potential” ciliopathy gene. A total of 140 unique potential ciliopathy genes were identified (Fig. 1a, listed in Supplementary Table S2). Phenotypes associated with each gene can be found in Table S2. Of these 140 lines, clinically relevant morphological or functional traits in all three systems (ocular, renal and reproductive) included a total of 31 genes: Abce1, Abhd11, Abi2, Ap4e1, Aplnr, Atp8b1, Bambi, Chsy3, Cops7a, Dnase1l2, Edc3, Fndc3b, Folr1, Gcgr, Gkn1, Gpa33, Ica1, Mink1, Mmachc, Nacc1, Pgbd1, Ptp4a1, Pygo2, Rspo1, Rxfp2, Sik3, Spred3, Sra1, Sun1, Tmem160, Tmem30b, and Wdr62. Detailed phenotype abnormalities can be found in Table S2.

Comparison of potential ciliopathy genes with preexisting cilia gene databases

From the IMPC 11.0 release, queried 29 April 2020, 5284 mouse lines had completed all phenotyping and were analyzed. Of these, 5190 lines had a corresponding human ortholog: 235 IMPC 11.0 genes were found in the 830 CiliaCarta genes17. 85 of the 217 Syscilia database genes were found in the IMPC 11.0 release. The 235 CiliaCarta genes and the 85 Syscilia genes that have complete data in the IMPC 11.0 release were analyzed for presence of phenotypic abnormalities consistent with ciliopathies. This data is summarized in Table S3. Of our 140 potential ciliopathy genes only 2 were found in the CiliaCarta database, Mapt and Myo7a. One of the potential ciliopathy genes from our analysis was also found in the list of known cilia genes based on the Syscilia database, Myo7a. (Fig. 1b,c).

Identification of candidate ciliopathy genes by protein–protein interaction analysis

We sought to determine if any of the 140 potential ciliopathy genes protein product interacted with known ciliopathy proteins. For the gold standard or known ciliopathy protein list 217 genes identified by Boldt et al.15 as part of the Syscilia were used. Figure 1b shows that of the 140 potential ciliopathy genes protein products, 24 are predicted to interact directly with known cilia proteins. Mouse genes were transposed to their human orthologs for the analysis. The human orthologs of the 24 corresponding mouse genes, Abi2, Ap4e1, Cdc42, Cdk4, Celsr1, Cops7a, Cyba, Dtnbp1, Dync1li1, Ehmt1, Folr1, Herc1, Klhl5, Mapt, Mib2, Myo7a, Prkab1, Ptp4a1, S1pr3, Sik3, Sugp1, Ube2a, Wsb2, and Xbp1, were each predicted to interact directly known cilia proteins. To further test if any of the potential ciliopathy genes had known interactions with ciliopathy proteins, 35 interacting proteins predicted by StringDB but not part of either of our 140 potential ciliopathy genes list nor the known 217 cilia gene list were incorporated into the interaction network. This analysis revealed one additional oculorenal gene predicted to interact with the cilium through secondary protein interactions, Wdr62, shown in Fig. 1c. In addition, 7 genes had primary interactions with the 24 directly interacting potential ciliopathy genes and thus had secondary interactions with known cilia proteins: Aplnr, Casr, Gcgr, Grm6, Med1(or Mbd4), Mlh1, and Rxfp2 (Fig. 1b). In total the 32 genes with evidence to have either primary or secondary interactions with known ciliopathy proteins and were considered to be “candidate ciliopathy genes” summarized in Table S1.

Candidate ciliopathy genes and literature review

The 32 candidate ciliopathy genes were reviewed for a previously published role in cilia biology in vertebrates or known association with ciliopathy in humans. Seven of the 32 have been previously identified as ciliopathy genes in vertebrates. However, only one gene of the 32 has been shown to have function in human cilia, leaving 31 candidate human ciliopathy genes and 25 genes with a previously undescribed role in ciliary biology. The summary of the literature review can be found in Table S1.

Histologic evidence of knockout mouse strains with concomitant abnormal ocular and renal or reproductive phenotypes

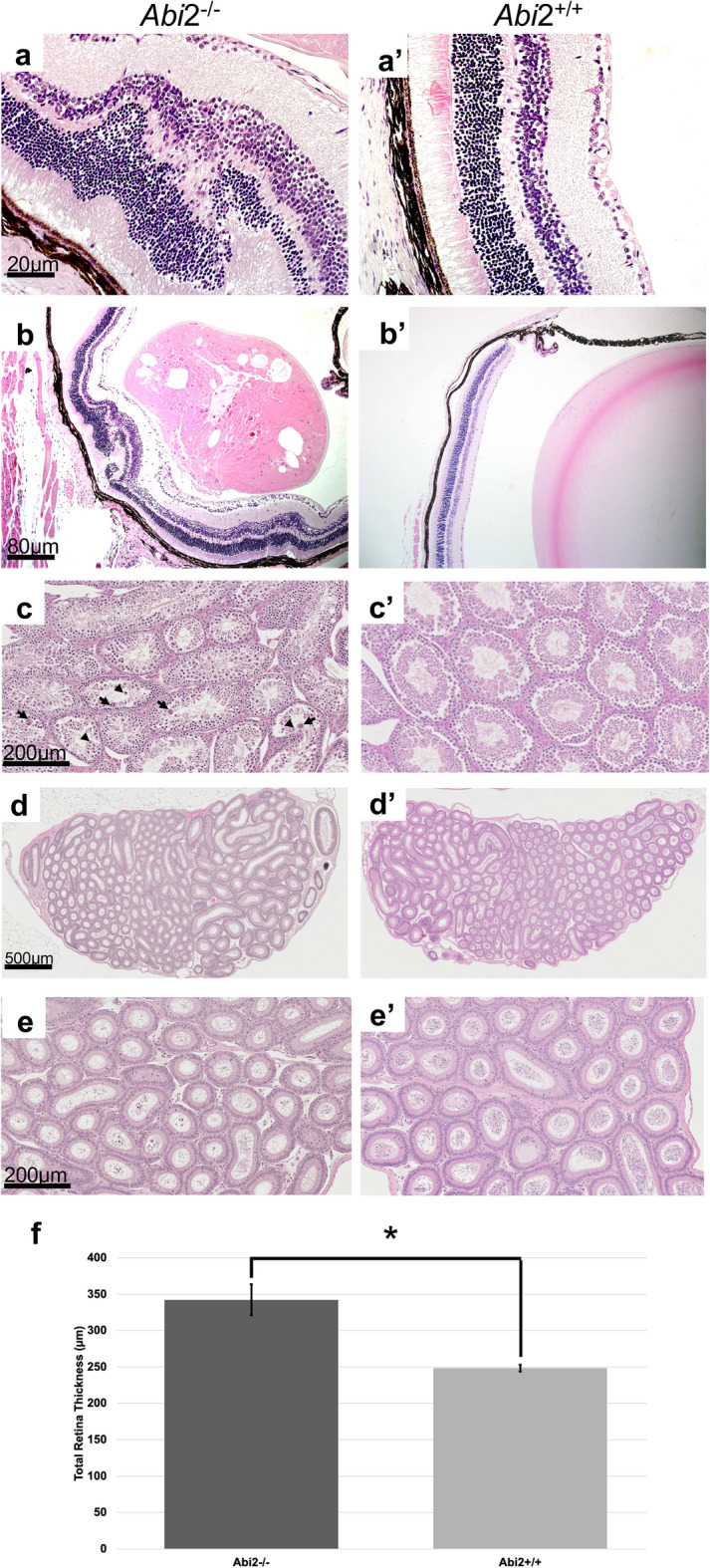

Five examples of the 32 candidate ciliopathy genes are presented. Mice with a homozygous KO of Abi2 show both eye and male reproductive abnormalities consistent with ciliopathies. The ophthalmic abnormalities seen in Abi2 null mice involve both the retina and the lens. Specifically, marked, chronic, multifocal localized retinal dysplasia characterized by multiple clusters of external nuclear structures are present within the outer plexiform layer of the retina. The lens features include cortical cataract with marked, chronic, focally extensive swollen and disrupted lens fibers with abnormally retained nuclei (balloon cells), as well as capsular thickening and wrinkling in the cortical region of the lens (Fig. 2a,b). Necropsy identified small testis, which on histopathology were characterized by testicular degeneration, marked, chronic, bilateral, multifocal vacuolation of the seminiferous tubules with hypocellularity, sparse spermatids, and very few spermatozoa. (Fig. 2c,d). The epididymis showed marked chronic hypospermia. All segments of epididymal ducts contain round bodies in the lumen with few spermatozoa (Fig. 2e). Quantitative analysis of the retinas of Abi2−/− mice revealed a total increased retinal thickness consistent with the noticeable dysplasia. (Fig. 2f).

Figure 2.

Abi2−/− mice had eye and male reproductive tract abnormalities consistent with ciliopathy compared to controls. (a) Marked, chronic, multifocal localized retinal dysplasia characterized by multiple clusters of external nuclear structures within the outer plexiform layer. (b) Cortical cataract is present with marked, chronic, focally extensive swollen and disrupted lens fibers with abnormally retained nuclei (balloon cells) with capsular thickening and wrinkling in the cortical region of the lens. (c) 20 × magnification histopathology showed testicular degeneration, marked, chronic, bilateral, multifocal vacuolation of the seminiferous tubule epithelia with primary and secondary spermatocyte and spermatid hypocellularity, with very few spermatozoa. Apoptotic bodies (arrowheads) and multinucleated giant cells (arrows) were frequent. (d) On magnification (5 ×), the epididymis showed marked hypospermia. Epididymal ducts in all segments of the epididymis (caput, corpus, cauda) contained cell and protein debris in the lumen with few mature spermatozoa. (e) Magnification (20 ×) of (d). (f) Quantitative measurement of average total retina thickness, where Abi2+/+ n = 12, average = 342.35 µm, SE = 4.88 and Abi2−/− n = 9, average = 342.35 µm, SE = 21.35 p-value = 0.0190. All error bars represent standard error of the mean, * indicates p-value < .05 result of student’s two-tailed t-test.

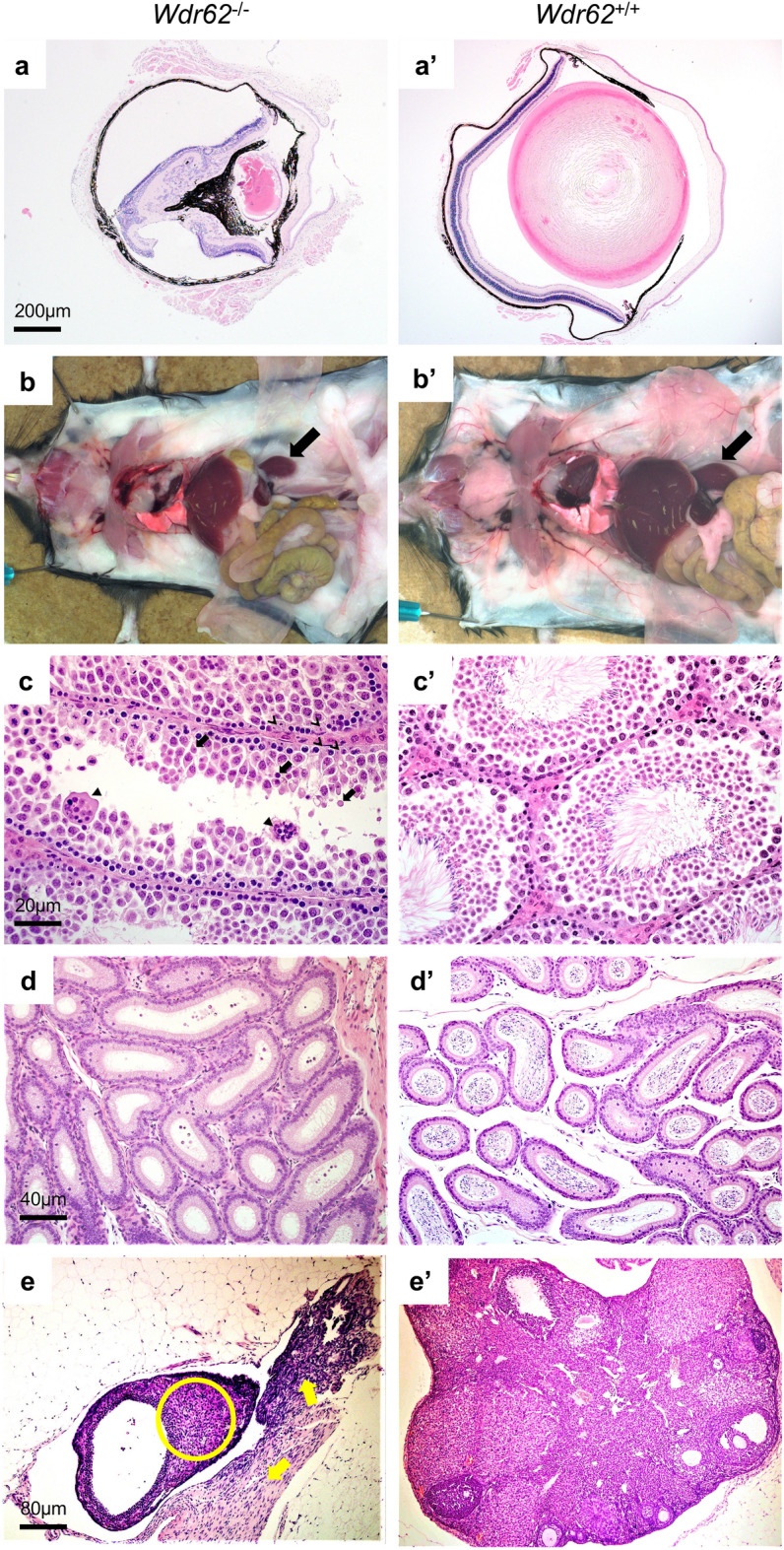

Wdr62 homozygous KO mice had ocular, renal, and reproductive organ abnormalities consistent with ciliopathy. The eyes demonstrated microphthalmia with undeveloped lens and residual lens vesicle remnant in the vitreous cavity. The ocular contents were small, malformed, and disorganized (Fig. 3a). The kidneys were small at necropsy, but constitutively unremarkable histologically (Fig. 3b). In the testes there was defective spermatogenesis with aspermia. There were numerous spermatogonia and spermatocytes, but rare spermatids and mature spermatozoa in seminiferous tubules of testes. Sertoli cells were prominent in the interstitium and seminiferous tubules contained degenerated cells with irregular dense nuclei. Overall, there was decreased testis size, reductions in spermatocyte and spermatid number, increased apoptosis of meiosis I spermatocytes, and multinucleated syncytia (Fig. 3c). Epididymal ducts also show defects with scattered cell debris and no spermatozoa (Fig. 3d). Homozygous deletion of Wdr62 also had effects on female reproductive organs. The ovaries were hypoplastic with no apparent folliculogenesis. The ovaries and ovarian bursa were very small dominated by fibrous connective tissue stroma with spindle shaped cells. Germinal epithelium, oocytes, and follicles were absent. The fibrous stroma contained immature solid tubular structures representing mesonephric remnants and interstitial hyperplasia (Fig. 3e).

Figure 3.

Wdr62−/− mice have ocular, renal, and reproductive organ abnormalities consistent with ciliopathy. (a) Microphthalmia with undeveloped lens and residual lens vesicle remnant in the vitreous cavity. The ocular contents are small, malformed, and disorganized. (b) Small kidneys at necropsy (arrow), but histologically normal in appearance (data not shown). (c) Testis with seminiferous tubule degeneration characterized by defective spermatogenesis and aspermia with increased apoptosis of meiosis I spermatocytes (arrow), and multinucleated syncytia (solid arrowhead). There are numerous spermatogonia and spermatocytes, but rare spermatids and mature spermatozoa. Sertoli cells are prominent (line arrowhead) and seminiferous tubules contain degenerated cells with irregular dense nuclei. (d) Epididymal ducts containing scattered cell debris and no spermatozoa. (e) Ovaries are small, hypoplastic with no detectable folliculogenesis. The ovarian bursa is hyperplastic, dominated by fibrous connective tissue stroma with spindle shaped cells (solid yellow arrows) and rare immature solid tubular structures (yellow circles) representing mesonephric remnants in the ovary. Germinal epithelium, oocytes, and follicles are absent.

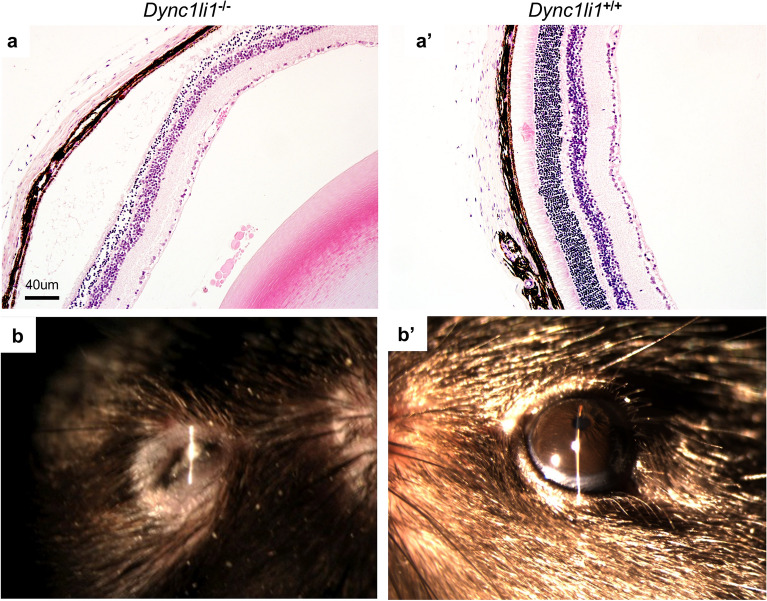

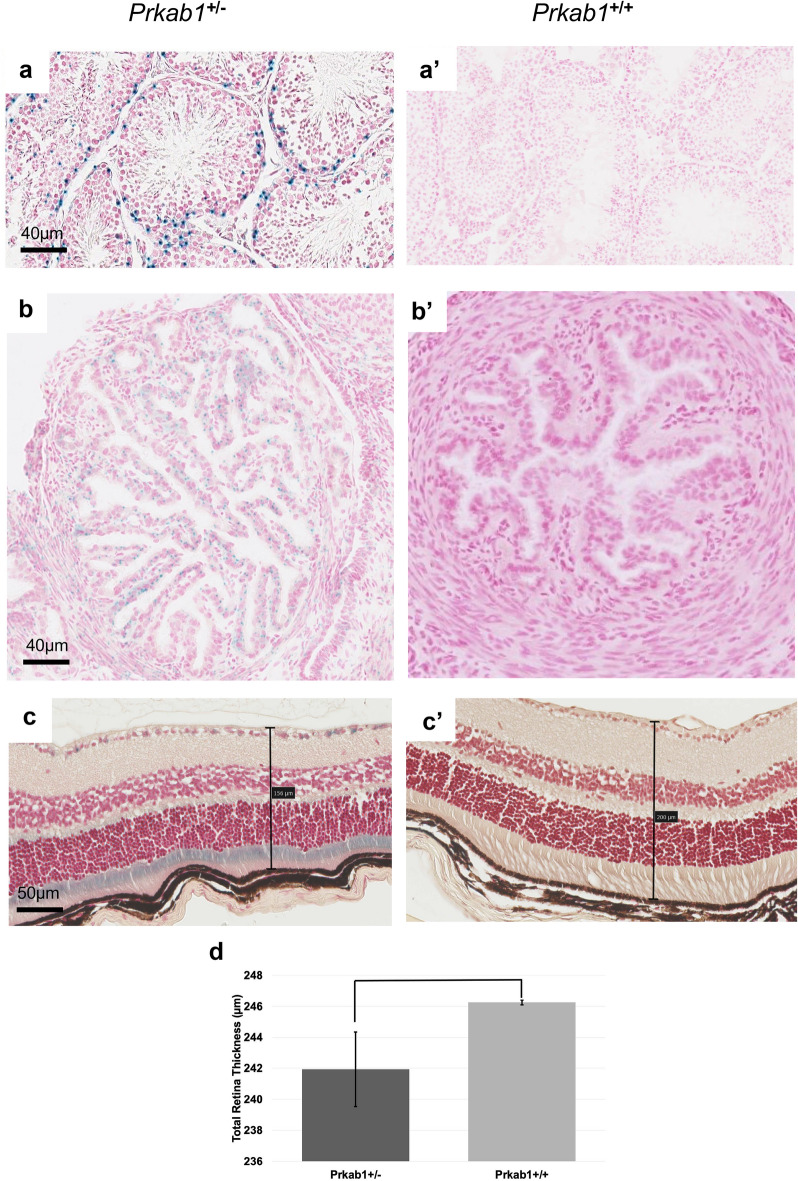

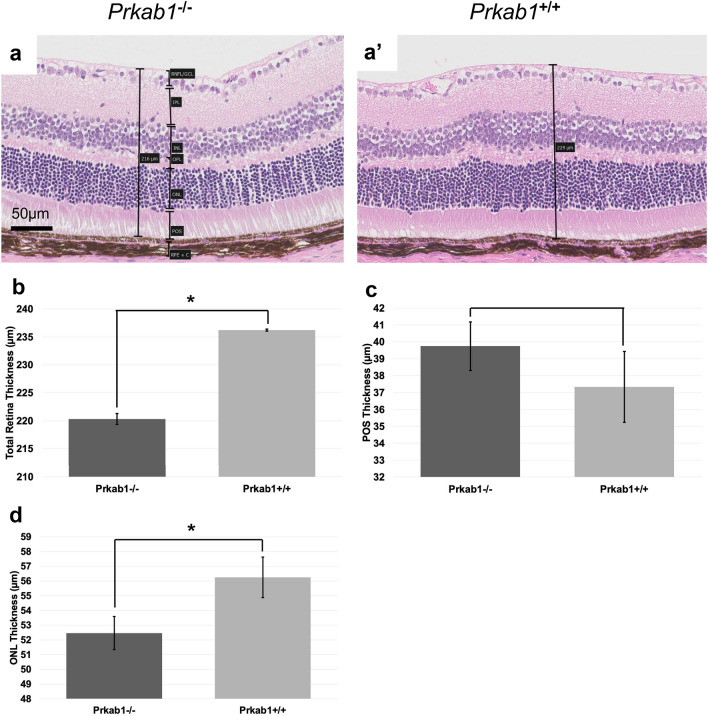

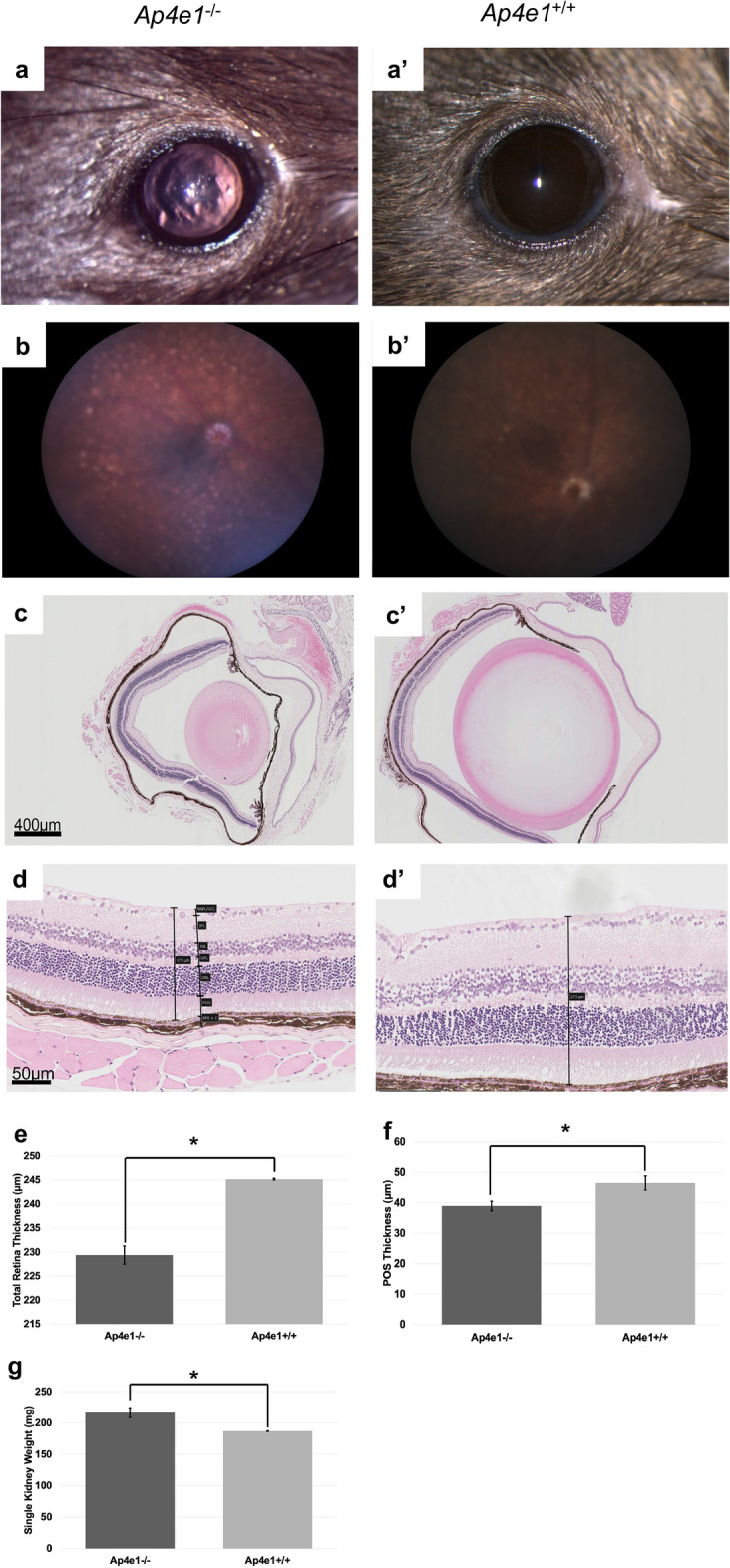

Ap4e1−/− mice had ocular abnormalities in the retina, cornea, and lens. Corneal epithelia irregularity can be appreciated on gross exam of the eye (Fig. 4a). There is extensive multifocal retinal hypopigmentation on color fundus photography (Fig. 4b). There is abnormal lens morphology, decreased total retinal thickness, and reduced thickness of the photoreceptor outer segment layer, (Fig. 4c–f). On gross examination Ap4e1−/− mice were noted as having abnormal kidney morphology, quantitative analysis of the kidneys revealed a decrease in overall weight. (Fig. 4g). Dync1li1 homozygous KO mice are microphthalmic (Fig. 5b) and demonstrate a decreased total thickness and extensive retinal hypoplasia and atrophy with cellular disorganization across all layers of the retina histologically (Fig. 5a). Mice heterozygous for Prkab1 (Prkab+/−) showed expression of LacZ under control of the Prkab1 promoter in the photoreceptor outer segments (Fig. 6c) LacZ expression under control of the Prkab1 promoter in male Prkab1+/− mice reproductive tract is found in seminiferous tubule epithelium (Fig. 6a). Female reproductive tract has scattered lacZ expression present in the oviduct. (Fig. 6b). Mice homozygous null for Prkab1 (Prkab−/−) have a decreased total retinal thickness (Fig. 7a,b) however do not have a reduction in size of the photoreceptor outer segment (Fig. 7c). Prkab−/− do have a reduction in the thickness of the outer nuclear layer (Fig. 7d).

Figure 4.

Ap4e1−/− mice have ocular abnormalities in the retina, cornea, lens, and have small kidneys. (a) Corneal epithelial irregularity on gross examination of the eye, focally extensive corneal epithelial squamous hyperplasia. (b) Extensive retinal hypopigmentary lesions on color fundus photography. (c) Abnormal lens morphology. (d) Decreased total retinal thickness. Retina layers labeled where RNFL/GCL, retinal nerve fiber layer/ganglion cell layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; POS, photoreceptor outer segments; RPE, retinal pigmented epithelium; C, choroid. (e) Quantitative measurement of average total retina thickness, where Ap4e1+/+ n = 3861, average = 245.20 µm, SE = 0.164 and Ap4e1−/− n = 45, average = 229.39 µm, SE = 1.89, p-value = 7.78 × 10–11. (f) Quantitative measurement of POS layer thickness. Where Ap4e1+/+ n = 8, average = 46.54 µm, SE = 2.35 and Ap4e1−/− n = 16, average = 38.99 µm, SE = 1.58, p-value = 0.019 . (g) Quantitative measurement of single kidney weight where Ap4e1+/+ n = 3629, 187.18 mg, SE = 0.581 and Ap4e1−/− n = 29, 217.54 mg, SE = 7.85, p-value = 0.00085. All error bars represent standard error of the mean, * indicates p-value < .05 result of student's two-tailed t-test.

Figure 5.

Dync1li1−/− mice have ocular abnormalities in the retina and microphthalmia. (a) Extensive retinal hypoplasia, atrophy, and cellular disorganization across all layers of the retina. In addition, the retina has decreased total thickness compared to control. (b) Microphthalmia evident on slit lap examination compared to control.

Figure 6.

Prkab1+/− LacZ expression under Prkab1 promoter is found in multiple reproductive tissues and photoreceptor outer segments of the retina. (a) lacZ reporter shows expression in the spermatogonia layer of the testis. (b) lacZ reporter expression under the control of the Prkab1 promoter in the oviduct shows faint scattered expression. (c) lacZ reporter expression under the control of the Prkab1 promoter shows strong signal in the wavy and disorganized photoreceptor inner and outer segments. (d) Quantitative measurement of average total retina thickness, where Prkab1+/+ n = 3698, average = 246.25 µm, SE = .148 and Prkab1+/- n = 28, average = 241.93, SE 2.40, p-value = 0.084. No significant difference was found in total retinal thickness based on student’s two-tailed t-test. All error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Figure 7.

Prkab1−/− mice have decreased total retinal thickness and reduced thickness of the ONL. (a) Prkab1−/− mice retinas show decreased total thickness with evidence of reduced thickness in the ONL. (b) Quantitative measurement of average total retina thickness, where Prkab1+/+ n = 6567, average = 236.21 µm, SE = 0.19 and Prkab1−/− n = 85, average = 220.29 µm, SE = .998. p = 1.078 × 10–27 (c) Quantitative measurement of POS layer thickness where Prkab1+/+ n = 9, average = 37.33 µm, SE = 2.09 and Prkab1−/− n = 14, average = 39.74 µm, SE = 1.43 p-value = .357 (d) Quantitative measurement of ONL thickness where Prkab1+/+ n = 11, average = 56.24 µm, SE = 1.37 and Prkab1−/− n = 14, average = 52.57 µm, SE 1.12 p-value = .039. All error bars represent standard error of the mean, * indicates p-value < .05 result of student’s two-tailed t-test. Retinal layers abbreviated as above.

Discussion

Ciliopathies are diseases of cilia, a cellular organelle in many eukaryotic cells. There are two distinct types of cilia; primary cilia and motile cilia, though all cilia have a microtubule-based axoneme structure covered by a plasma membrane that extends into the extracellular space. In humans, primary cilia enable cells to sense the environment. Motile cilia beat in a coordinated fashion to move cells or fluid external to cells. Primary cilia are found one per cell and are histologically distinct from motile cilia. The axoneme differs between primary and motile cilia. Primary cilia have a 9-microtubule doublet structure without central microtubules or a “9 + 0 structure”, while motile cilia have 9-microtubule doublets surrounding a two-microtubule “9 + 2 structure”. Motile cilia have dynein arms that connect the 9 microtubule doublets and allow the cilia to move through dynein motor activity23.

The phenotypic spectrum of ciliopathies reflect the function of both immotile and motile cilia24. The hallmark features of abnormal motile cilia are chronic respiratory conditions due to defective mucociliary clearance, infertility due to abnormal sperm motility or maturation25, and hydrocephalus as a result of defects in the ependymal cells that line the ventricles of the brain and are functionally responsible for normal production, resorption, and flow of cerebrospinal fluid25. Shared with both motile and immotile ciliopathies are situs abnormalities and congenital cardiac abnormalities. Motile and immobile cilia are expressed at the embryonic node during development and are responsible for determining left–right asymmetry by movement of morphogens26. Phenotypes unique to immotile or primary ciliopathies are broad and reflect the diverse environmental sensing and signaling function of the organelle. Renal and ocular abnormalities, specifically retinal abnormalities, are a common feature of ciliopathies. However, defects of the primary cilia can also include anosmia, hearing loss, obesity, skeletal anomalies, genital anomalies, various neurological disorders, craniofacial abnormalities, and liver disease24.

Ciliopathies affecting the eye typically result in retinal degeneration and include LCA, NPHP, SLS (a syndrome with main features of NPHP and LCA), JBTS, and BBS8. LCA is a retinal dystrophy that presents in infants. In humans, mutations in ciliary proteins RPGRIPL1 and CEP290 are linked to LCA and to several other ciliopathies1. NPHP commonly progresses to chronic kidney diseases within the first 30 years of life and is also associated with retinopathy resulting in SLS27. BBS has hallmark features of retinitis pigmentosa and kidney failure. Sixteen genes are thought to be associated with BBS and 8 of these make up an octameric complex of the ciliary basal body28. JBTS results in a cerebellar vermis hypoplasia and enlarged superior cerebellar peduncles along with mental retardation. Individuals with JBTS can also have retinal dystrophy and renal failure with nephronophthisis, which can result in normal or reduced kidney size29,30. Mutations of the same gene within the cilia can manifest with a varying constellation of clinical signs. For example, NPHP1 is a gene that can be mutated in either NPHP31, SLS32, or JBTS33. It has been localized to the connecting cilium of the photoreceptor and its normal function is thought to be protein transport along the photoreceptor. Mice with mutations in Nphp1 have abnormal intraflagellar transport along the cilia and have protein sorting defects along the inner and outer segments of the photoreceptor34.

Twenty-four of the 140 potential ciliopathy genes were identified as being direct cilia interactants (Abi2, Ap4e1, Cdc42, Cdk4, Celsr1, Cops7a, Cyba, Dtnbp1, Dync1li1, Ehmt1, Folr1, Herc1, Klhl5, Mapt, Mib2, Myo7a, Prkab1, Ptp4a1, S1pr3, Sik3, Sugp1, Ube2a, Wsb2, and Xbp1) based on STRING protein interaction analysis (Fig. 1b). Eight of the 140 potential ciliopathy genes had predicted secondary interaction with gold standard cilia proteins, Aplnr, Casr, Gcgr, Grm6, Med1(or Mbd4), Mlh1, Rxfp2, and Wdr62. (Fig. 1b,c). In total we identified a list of 32 candidate ciliopathy proteins, summarized in Table S1.

Retinal dysplasia, as seen in the Abi2 KO mice, has been previously noted in the description of the ocular manifestations of Meckel syndrome35,36. Abi2 KO mice have previously been shown to have defects in lens development, specifically abnormalities in secondary lens fiber migration37,38. Here we reproduce that Abi2 may have a role in lens development. The IMPC Abi2 homozygous KO mice had focally extensive swollen and disrupted lens fibers with abnormally retained nuclei (balloon cells) with capsular thickening and wrinkling in the cortical region of the lens (Fig. 2a). Abi2 is thought to have a role in cytoskeleton remodeling at epithelial cell–cell junctions and dendritic spines37. The developing lens fiber cells have polarized primary cilia, but they are not thought to play an essential role in directing the formation of the lens39. Mutations in genes that are known ciliopathy genes such as Bbs4 and Bbs8 do not have an essential role in coordinating lens alignment40. ABI2 or Abi2 has not been shown to have any association with ciliopathies in humans nor links to retinal abnormalities characteristic of ciliopathies.

Human male and female infertility have been reported in ciliopathies. There are several cilia in the male reproductive system: sperm flagella, multiple motile cilia of the efferent ducts of the testis (rete testis) and efferent ductules of the epididymis and primary cilia of the testis, rete testis, epididymis, and prostate41. Furthermore, the multiple motile cilia of the efferent ductules of the epididymis have been shown to be important for clearing fluid and moving sperm by keeping them in suspension in fluid, failure of which leads to clogging and back flow of sperm into the testis42. The Abi2 KO mice had small testes, which on histopathology showed testicular degeneration, marked, chronic, bilateral, multifocal vacuolation of the seminiferous tubular epithelium with hypocellularity, sparse spermatids, and very few spermatozoa tubular lumens. Apoptotic bodies and multinucleated giant cells were frequent. The epididymis showed marked chronic hypospermia. All segments of the epididymal ductules (caput, corpus, cauda) contained round bodies in the lumen with few spermatozoa. This suggests a failure in the maturation of sperm and subsequent immune mediated degradation of the sperm leading to testicular atrophy (Fig. 2c–e).

Ap4e1 KO mice have been shown to specifically have retinal abnormalities of marked reordering of the outer plexiform layer. Other retinal abnormalities of Ap4e1 KO mice include reduced responses in both the scotopic a-wave, which represents photoreceptor function, as well as the scotopic b-wave on ERG38. Here we recapitulate a different retinal phenotype for Ap4e1 mutants consisting of decreased POS thickness (Fig. 4f) and decreased total retinal thickness (Fig. 4e), as well as abnormal lens morphology (Fig. 4c). Additionally, mutations in the human gene result in a pale optic disc. Other abnormalities include cerebral palsy, microcephaly, and intellectual disability43. This gene at the cellular level is a part of a heterotetrametric complex that mediates vesicle formation and sorting44. Though Ap4e1 does not have an established role in cilia, the predicted protein interaction with OCRL1 is suggestive that Ap4e1 may be involved in ciliary assembly as OCRL1 is known to be involved in primary ciliary assembly and mutations in OCRL1 result in congenital cataracts, renal abnormalities, and learning disabilities, a ciliopathy syndrome called Lowe syndrome45.

Wdr62 has evidence of being a novel second order ciliopathy gene through its interaction with an intermediary protein CEP63 (Fig. 1c). Wdr62 KO mice had testicular degeneration (Fig. 3c) and epididymal hypospermia. All segments of epididymal ducts contained round bodies in the lumen with few spermatozoa (Fig. 3d). The retinal abnormalities, multifocal localized retinal dysplasia (Fig. 3a), along with the testes and epididymides changes are highly suggestive of defective ciliary function since both infertility and retinal abnormalities can be considered hallmarks of either motile or immotile ciliopathies14. A previously published Wdr62 KO mouse strain established its role in centriole biogenesis46 and oocyte meiotic initiation47. WDR62 is a centriole associated protein and has been noted previously in the literature to interact with CEP63 as part of centriole duplication and when mutated can result in microcephaly46. The centrioles are responsible for forming the base of the axoneme, the “skeleton” or case that the cilia will grow out into48,49. Here we present evidence that Wdr62 mutations can result in defective formation of the motile cilia as manifest by IMPC Wdr62 homozygous KO mice with both aspermia and several malformations of the lens of the eye (Fig. 3a,c,d).

Dync1li1 has a previously described KO mouse that reported a role for Dync1li1 in both retinal and ciliary biology. These Dync1li1 KO mice were reported to have increased photoreceptor degradation and a described role in stabilization of dynein during ciliogenesis. Dync1li1 normally functions to promote Rab11-vesicle trafficking and efficient OS protein transport from Golgi to the basal body50. Here we confirm that Dync1li1 KO mice have retinal defects and photoreceptor degradation demonstrated by atrophy at various levels of the retina (Fig. 5a). In addition, DYNC1LI1 may have a role in human cilia since it is predicted to interact with several known human cilia proteins (Fig. 1b).

Prkab1 heterozygous KO mice have no previous described role in ciliary biology in vertebrates or humans (Table S1). A previously reported Prkab1 KO mouse had splenomegaly, anemia, and erythrocyte morphologic abnormalities; a cluster of pathologies consistent with hemolytic anemia51. Prkab1 is a part of the beta subunit of serine/threonine AMP-activated protein kinase, a heterotrimeric complex containing a catalytic alpha subunit paired with beta and gamma regulatory subunits. This protein complex is thought to be an essential regulator of cellular energy balance52. Expression was observed of the lacZ reporter under Prkab1 native promoter throughout the male and female reproductive tracts in the testis and oviduct. (Fig. 6a–b) Further, expression was observed in the outer segments of the photoreceptor cells. (Fig. 6c). Prkab1 homozygous KO mice show decreased total retina thickness (Fig. 7b), although the outer segment of the photoreceptor showed no difference in thickness compared to control. (Fig. 7c) Prkab1 homozygous KO do show a reduction in the outer nuclear layer thickness. (Fig. 7d). Given that the outer nuclear layer contains the cell bodies of the photoreceptor cells53. Taken with the evidence of expression of the lacZ reporter under Prkab1 native promote in the outer segments of the photoreceptor cells, this may suggest a role for Prkab1 in development of the structure of the outer nuclear cell layer.

The results here provide both biologic and bioinformatic evidence of candidate ciliary disease genes that have mouse KO data to suggest a role in eye, kidney, and reproductive biology. The IMPC serves as a valuable resource of standardized KO mouse production and phenotyping to identify gene function. This approach can facilitate discovery of novel genes potentially associated with human disease, particularly those with multiple organ system involvement as each mouse undergoes comprehensive analysis of every major organ system. In combination with protein–protein interaction analysis, the IMPC data set provided us with a powerful tool for predicting gene function, multi-system disease processes, and biological processes based on predicted binding partners. However, this type of research has significant limitations. The pathologies present in a mouse KO may not be representative of human disease states due to species differences, which may negate disease relevance in humans. Also, the ability of the IMPC’s phenotyping pipeline to detect abnormalities is limited to the panel of tests that are used, and thus, phenotypes will be missed. Furthermore, interactions between proteins may be context dependent in a cell-type specific manner and may not be representative of the cellular function in every organ system. Mechanistic biochemical studies are required to confirm the ciliopathy candidates in this report and despite the overlapping ocular, renal, and reproductive abnormalities attributed to each knockout line in this study, direct validation of each candidate protein should be confirmed in primary cilia.

In summary, we present in vivo analytical findings for 32 candidate ciliopathy genes based on phenotypic changes identified in KO mice and predicted protein–protein interactions with known human cilia genes. One of the 32 has been shown previously to have function in human cilia, leaving 31 new candidate human ciliopathy gene candidates. Twenty-five of these are previously undescribed candidate vertebrate ciliary genes. Five of these genes predicted to have ciliary interaction (Abi2, Wdr62, Ap4e1, Dync1li1, and Prkab1) had abnormal morphological features detected by imaging that are consistent with the spectrum of phenotypes observed in ciliopathies. Wdr62 and Dyncli1 have previously described roles in vertebrate ciliary biology, while Abi2, Ap4e1, and Prkab1 do not. Abi2, Ap4e1, and Prkab1 therefore have strong evidence to be novel candidate ciliopathy genes. These candidate genes require validation in unsolved human cases with systemic features pertinent to ciliopathy. If relevant in human disease, these mouse KO may serve as valuable models for study of this group of ciliopathies.

Materials and methods

Knockout strain production

Detailed methods for mutant mouse production has been published previously20. For those lines generated from homologous recombination in ES cells, a lacZ reporter was integrated into the gene targeting vector to enable tissue-specific expression under the control of the endogenous promoter54. Phenotyping data was generated by the analysis of sex-balanced cohorts of homozygous (or heterozygous if embryo lethal) adult knockout female (n ≥ 7) and male (n ≥ 7) mice between 4 and 16 weeks of age and compared to contemporaneous data on age, sex (n = 2 male and n = 2 female), and genetic background (C57BL/6 N)-matched wildtype control mice. Strict ethical review and guidelines of accrediting authorities were followed by all International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC) centers specific to their national and regional legislation and local institutional guidelines (Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committees, Regierung von Oberbayern, Com’Eth, Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Bodies, RIKEN Tsukuba Animal Experiments Committee, and Animal Care Committee). The IMPC Consortium collects data from international member institutes who collect phenotyping data guided by their own ethical review panels, licenses, and accrediting bodies that reflect the national and/or geo-political constructs in which they operate. We have captured this data via an ethical and funding survey from each contributing institute, this can be found at http://www.mousephenotype.org:8858/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/EthicalInfo2014.pdf. A comprehensive overview of the IMPC mouse phenotyping protocol consistent with ARRIVE guidelines55 can be found at https://www.mousephenotype.org/about-impc/animal-welfare/arrive-guidelines/ and is published previously21.

Phenotyping

A comprehensive ophthalmic examination was performed on both eyes of each mouse at 15–16 weeks of age by experienced technical staff using ocular imaging equipment overseen by lead site scientists and/or expert ophthalmologists. Examiners were trained to identify and annotate background lesions (e.g., retinal dysplasia) commonly but inconsistently observed in the C57BL/6 N strain56. Fertility testing of both sexes was performed at 8–14 weeks, renal morphology was assessed during necropsy at 16 weeks, and clinical chemistry testing was done on a serum sample collected prior to termination.

As described in prior publications from the IMPC, phenotyping of mice was performed in a randomized fashion and technicians were blinded to the genotype (mutant or wildtype) of mice before and during examination57. Irises were pharmacologically dilated with 2.5% phenylephrine HCl (Akorn Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA): 1% tropicamide (Bausch & Lomb Inc., Tampa, FL, USA) to facilitate eye examinations. A 0.1 mm slit beam at the highest intensity setting was used to evaluate the anterior segment including cornea, anterior chamber, and lens followed by assessment of the posterior segment including the vitreous chamber. The fundus was examined via indirect ophthalmoscopy using a 60 diopter double aspheric handheld lens (Volk Optical Inc, Mentor, OH, USA).

OCT imaging was performed (machine dependent on institution), after dilatation with both tropicamide 1% and phenylephrine 2.5%. Thickness of the total retina, inner nuclear layer, outer nuclear layer, were manually measured at a distance of ~ 0.2 mm from each side of the optic nerve using calipers in ImageJ software. Measurements from both sides of the optic nerve head and between left and right eyes were averaged for each animal.

Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine concentrations were analyzed on ~ 160–200 μl of plasma separated from whole blood collected by retro-orbital puncture in a gel tube containing lithium heparin after centrifugation for 10 min at 5000×g at 8 °C. Plasma samples were analyzed optimally on the day of collection in a clinical chemistry analyzer either Beckman Coulter AcT Diff, Siemens Advia 2120 or Hemavet Multispecies Hematology Analyzer HV950FS (Drew Scientific, CT, U.S.A.).

Specimen collection

A complete necropsy was performed and all abnormal findings were recorded and annotated using the standardized IMPC Gross Pathology ontology56. Macroimages were captured of abnormal gross findings when possible. All fresh tissue samples collected at necropsy were immediately immersed in fixative (typically 10% neutral buffered formalin) and prepared for histopathological examination by a veterinary pathologist. Mild to moderate focal retinal dysplasia observed by histopathology were considered incidental background strain changes attributed to C57BL/6 N background and were excluded from genotype-associated phenotype calls. Parasagittal sections of eyes were sectioned at 5 µm, and stained with hematoxylin–eosin (H&E). Retinal layer measurements were taken of total retina, nerve fiber layer, retinal ganglion cell layer, inner plexiform layer, inner nuclear layer, outer plexiform layer, outer nuclear layer, photoreceptor outer segment, retinal pigmented epithelium, and choriod were manually measured at a distance of ~ 0.2 mm from each side of the optic nerve using calipers in NDP.view2. (U12388-01) (Hamamatsu, NJ, USA).

Imaging

When possible at some centers with the requisite instrumentation, advanced imaging techniques were used to document suspected abnormalities for follow-up and evaluation. In these cases, mice were first anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/midazolam (50–75/1–2 mg/kg) and their eyes dilated using topical tropicamide 1% and phenylephrine 2.5% drops and lubricated with artificial tears containing methylcellulose. Anterior segment and fundus images were acquired with a Micron III or IV retinal imaging microscope (Phoenix Research Laboratories, City, USA).

Query of the IMPC database to identify potential ciliopathy genes

The IMPC website’s data release 11.0 was queried for five common abnormalities in human ciliopathy syndromes: abnormal ocular traits, abnormal renal morphology, abnormal renal function, abnormal reproductive morphology, and abnormal reproductive function. For “abnormal ocular traits” the term “abnormal ocular phenotypes” was used to search the database. Abnormal renal morphologies were identified by searching “abnormal kidney/renal phenotypes”. Abnormal renal function was identified by searching for “abnormal blood urea nitrogen (BUN)” or “abnormal blood creatinine (CRE)”, both commonly used lab values to assess kidney function in clinical practice58. Abnormal reproductive morphology was identified by query of the database for “abnormal reproductive morphology”. Abnormal reproductive function was identified by searching for “infertility” and its synonym “abnormal fertility/fecundity”.

To identify genes with the potential for being associated with a ciliopathy, all genes associated with abnormal renal morphology, abnormal renal function, abnormal reproductive morphology, and abnormal reproductive function were then assessed for any concomitant abnormal ocular traits. Each gene set for the aforementioned systemic trait abnormalities was compared for intersection, or overlapping genes, using Interactive Venn59 (Fig. 1a and Table S2). This list of genes with both ocular and renal or reproductive trait abnormalities are referred to as “potential ciliopathy genes”.

To provide quantitative data relating to retinal thickness, the current release of the IMPC 16.0 was queried on 6/1/2022 for the retina thickness data of Ap4e1 and Prkab1 heterozygote and homozygous KO mice.

Bioinformatic analysis

To determine if the protein products of the “potential ciliopathy genes” interacted directly with any of the existing known ciliopathy genes, the mouse genes were transposed to their human orthologs. The gene list of 217 known human ciliopathy genes was previously generated, Boldt et al.15 reported a list of 217 proteins, where 124 of the 217 are Syscilia gold standard proteins16, 91 of the 217 are ciliopathy-associated proteins, and 80 of the 217 are proteins with predicted ciliary function, with genes overlapping between the three categories60. Protein interaction networks were built using the functional protein association network tool STRING-db61 version 1.5.1 built in Cytoscape 3.8 App, StringApp62. The “potential ciliopathy genes” and “known ciliopathy genes” were analyzed for protein–protein interactions using a confidence threshold of 0.9 (Fig. 1b). To further test if any of the “potential ciliopathy genes” had interactions with “known ciliopathy genes”, 35 interacting proteins predicted by StringDB which were not part of either of the “potential ciliopathy genes” list nor the 217 “known ciliopathy genes” list were included in the analysis (Fig. 1c).

Literature review of candidate ciliopathy genes

Potential ciliopathy genes that had a predicted protein interaction with known ciliopathy genes either directly or through a secondary protein were considered to be “candidate” ciliopathy genes. All candidate ciliopathy genes were individually queried (www.pubmed.gov and www.google.com/scholar) with a search term (“kidney” “renal” “eye” “ocular” “retina” “reproductive” and “infertility”) to determine previous association between the respective trait abnormalities. The search was further modified to determine whether a KO mouse had been previously generated and analyzed. For candidate ciliopathy genes, gene names and the search terms “cilia” or “ciliopathy” were queried for previous implication in ciliary biology. In addition, MalaCards63 database was queried for each gene; those with publications supporting disease associations are summarized in Table S1.

Statistical analysis

Protein interaction networks were built using the functional protein association network tool STRING-db61 version 1.5.1 built in Cytoscape 3.8 App, StringApp62. The “potential ciliopathy genes” and “known ciliopathy genes” were analyzed for protein–protein interactions using a confidence threshold of 0.9. Confidence threshold calculations done are a setting in the version 1.5.1 built in Cytoscape 3.8 App, StringApp.

Phenotyping data was generated by the analysis of sex-balanced cohorts of homozygous (or heterozygous if embryo lethal) adult knockout female (n ≥ 7) and male (n ≥ 7) mice between 4 and 16 weeks of age and compared to contemporaneous data on age, sex (n = 2 male and n = 2 female), and genetic background (C57BL/6 N)-matched wildtype control mice. Detailed methods for mutant mouse production has been published previously20.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Strict ethical review and guidelines of accrediting authorities were followed by all International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC) centers specific to their national and regional legislation and local institutional guidelines (Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committees, Regierung von Oberbayern, Com’Eth, Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Bodies, RIKEN Tsukuba Animal Experiments Committee, and Animal Care Committee).

Consent for publication

All authors have agreed to the publication of this article.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors profoundly apologize for not be able to name all these individuals due to space limitations. The authors wish to acknowledge the full list of IMPC members that were crucial to the success of this study, listed as co-authors in the SI Appendix. IMPC Consortium members listed in the main authorship block may also be found in SI Appendix.

Abbreviations

- BBS

Bardet–Biedl Syndrome

- BUN

Blood urea nitrogen

- CRE

Blood creatinine

- DCC

IMPC Data Coordination Center

- HCl

Hydrogen Chloride

- IMPC

International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium

- JBTS

Joubert Syndrome

- KO

Knockout

- LCA

Leber Congenital Amaurosis

- MGS

Meckel–Gruber syndrome

- NPHP

Nephronophthisis

- PCD

Primary cilia dyskinesia

- PKD

Polycystic kidney disease

- SLS

Senior-Loken Syndrome

- RNFL/GCL

Retinal nerve fiber layer/ganglion cell layer

- IPL

Inner plexiform layer

- INL

Inner nuclear layer

- OPL

Outer plexiform layer

- ONL

Outer nuclear layer

- POS

Photoreceptor outer segments

- RPE

Retinal pigmented epithelium

- C

Choroid

Author contributions

K.H. performed gene analysis, created the figures, and wrote the manuscript. B.A.M. performed gene analysis and was involved in ocular phenotyping and data procurement. A.M. conceived the project, directed and performed gene analysis, created the figures, and wrote the manuscript. C.M. and K.C.K.L. were involved with study conception, ocular phenotyping, data procurement, and helped create the figures. D.C. was involved with data procurement. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors thank all the various funding agencies supporting the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium. The authors gratefully acknowledge their funding sources, including the Government of Canada through Genome Canada/Ontario Genomics OGI-051 (CM), NIH K08EY027463, NIH R03OD032622 (AM). NIH U54HG006364, U42OD011175, 5UM1OD02322, and UM1OD023321 (KCKL and CM). Hands-on mouse IMPC phenotyping has been carried out by a large number of laboratory staff with superb experimental skills and unsurpassed dedication.

Data availability

Materials Availability All mice generated are available from the IMPC. See impc.org for more details.

Code availability

All raw data is available at impc.org, no original code was generated during the research.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A list of authors and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

Contributor Information

Colin McKerlie, Email: colin.mckerlie@sickkids.ca.

Ala Moshiri, Email: amoshiri@ucdavis.edu.

The IMPC Consortium:

Arthur L. Beaudet, Bob Braun, Natasha Karp, Ann-Marie Mallon, Terrence Meehan, Yuichi Obata, Helen Parkinson, Damian Smedley, Glauco Tocchini-Valentini, and Sara Wells

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-19710-7.

References

- 1.Waters AM, Beales PL. Ciliopathies: An expanding disease spectrum. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2011;26:1039–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1731-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartoloni L, et al. Mutations in the DNAH11 (axonemal heavy chain dynein type 11) gene cause one form of situs inversus totalis and most likely primary ciliary dyskinesia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:10282–10286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152337699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ichioka K, Kohei N, Okubo K, Nishiyama H, Terai A. Obstructive azoospermia associated with chronic sinopulmonary infection and situs inversus totalis. Urology. 2006;68:204.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inaba K, Mizuno K. Sperm dysfunction and ciliopathy. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2015;15:77–94. doi: 10.1007/s12522-015-0225-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenfeld CS. Male reproductive tract cilia beat to a different drummer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019;116:3361–3363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1900112116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eley L, Yates LM, Goodship JA. Cilia and disease. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2005;15:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kathem SH, Mohieldin AM, Nauli SM. The roles of primary cilia in polycystic kidney disease. AIMS Mol. Sci. 2014;1:27–46. doi: 10.3934/molsci.2013.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerdes JM, Davis EE, Katsanis N. The vertebrate primary cilium in development, homeostasis, and disease. Cell. 2009;137:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.den Hollander AI, et al. Mutations in the CEP290 (NPHP6) gene are a frequent cause of Leber congenital amaurosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;79:556–561. doi: 10.1086/507318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leitch CC, et al. Hypomorphic mutations in syndromic encephalocele genes are associated with Bardet–Biedl syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:443. doi: 10.1038/ng.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sayer JA, et al. The centrosomal protein nephrocystin-6 is mutated in Joubert syndrome and activates transcription factor ATF4. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:674–681. doi: 10.1038/ng1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valente EM, et al. Mutations in CEP290, which encodes a centrosomal protein, cause pleiotropic forms of Joubert syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:623–625. doi: 10.1038/ng1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang B, et al. In-frame deletion in a novel centrosomal/ciliary protein CEP290/NPHP6 perturbs its interaction with RPGR and results in early-onset retinal degeneration in the rd16 mouse. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:1847–1857. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware SM, Aygun MG, Hildebrandt F. Spectrum of clinical diseases caused by disorders of primary cilia. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2011;8:444–450. doi: 10.1513/pats.201103-025SD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boldt K, et al. An organelle-specific protein landscape identifies novel diseases and molecular mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11491. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Dam TJ, et al. The SYSCILIA gold standard (SCGSv1) of known ciliary components and its applications within a systems biology consortium. Cilia. 2013;2:7. doi: 10.1186/2046-2530-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Dam TJP, et al. CiliaCarta: An integrated and validated compendium of ciliary genes. bioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.1101/123455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown SDM, Moore MW. Towards an encyclopaedia of mammalian gene function: The International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium. Dis. Model. Mech. 2012;5:289–292. doi: 10.1242/dmm.009878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown SDM, Moore MW. The International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium: Past and future perspectives on mouse phenotyping. Mamm. Genome. 2012;23:632–640. doi: 10.1007/s00335-012-9427-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koscielny G, et al. The International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium Web Portal, a unified point of access for knockout mice and related phenotyping data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D802–D809. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karp NA, et al. Applying the ARRIVE guidelines to an in vivo database. PLoS Biol. 2015;13:e1002151–e1002151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurbatova N, Mason JC, Morgan H, Meehan TF, Karp NA. PhenStat: A tool kit for standardized analysis of high throughput phenotypic data. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0131274–e0131274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bisgrove BW, Yost HJ. The roles of cilia in developmental disorders and disease. Development. 2006;133:4131–4143. doi: 10.1242/dev.02595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiter JF, Leroux MR. Genes and molecular pathways underpinning ciliopathies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;18:533–547. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horani A, Ferkol TW, Dutcher SK, Brody SL. Genetics and biology of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2016;18:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchison HM, Valente EM. Motile and non-motile cilia in human pathology: From function to phenotypes. J. Pathol. 2017;241:294–309. doi: 10.1002/path.4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ronquillo CC, Bernstein PS, Baehr W. Senior-Loken syndrome: A syndromic form of retinal dystrophy associated with nephronophthisis. Vis. Res. 2012;75:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin H, et al. The conserved Bardet–Biedl syndrome proteins assemble a coat that traffics membrane proteins to cilia. Cell. 2010;141:1208–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, et al. Sclt1 deficiency causes cystic kidney by activating ERK and STAT3 signaling. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017;26:2949–2960. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arts HH, Knoers NVAM. Current insights into renal ciliopathies: What can genetics teach us? Pediatr. Nephrol. 2013;28:863–874. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2259-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hildebrandt F, et al. A novel gene encoding an SH3 domain protein is mutated in nephronophthisis type 1. Nat. Genet. 1997;17:149–153. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caridi G, et al. Renal-retinal syndromes: Association of retinal anomalies and recessive nephronophthisis in patients with homozygous deletion of the NPH1 locus. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1998;32:1059–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(98)70083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parisi MA, et al. The NPHP1 gene deletion associated with juvenile nephronophthisis is present in a subset of individuals with Joubert syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;75:82–91. doi: 10.1086/421846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang S-T, et al. Essential role of nephrocystin in photoreceptor intraflagellar transport in mouse. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:1566–1577. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams NA, Awadein A, Toma HS. The retinal ciliopathies. Ophthalmic Genet. 2007;28:113–125. doi: 10.1080/13816810701537424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacRae DW, Howard RO, Albert DM, Hsia YE. Ocular Manifestations of the meckel syndrome. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1972;88:106–113. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1972.01000030108028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grove M, et al. ABI2-deficient mice exhibit defective cell migration, aberrant dendritic spine morphogenesis, and deficits in learning and memory. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:10905–10922. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.24.10905-10922.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Albrecht NE, et al. Rapid and integrative discovery of retina regulatory molecules. Cell Rep. 2018;24:2506–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sugiyama Y, et al. Secreted frizzled-related protein disrupts PCP in eye lens fiber cells that have polarised primary cilia. Dev. Biol. 2010;338:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugiyama Y, et al. Non-essential role for cilia in coordinating precise alignment of lens fibres. Mech. Dev. 2016;139:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Girardet L, Augière C, Asselin M-P, Belleannée C. Primary cilia: Biosensors of the male reproductive tract. Andrology. 2019;7:588–602. doi: 10.1111/andr.12650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuan S, et al. Motile cilia of the male reproductive system require miR-34/miR-449 for development and function to generate luminal turbulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019;116:3584–3593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1817018116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moreno-De-Luca A, et al. Adaptor protein complex-4 (AP-4) deficiency causes a novel autosomal recessive cerebral palsy syndrome with microcephaly and intellectual disability. J. Med. Genet. 2011;48:141–144. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.082263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dell’Angelica EC, Mullins C, Bonifacino JS. AP-4, a novel protein complex related to clathrin adaptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:7278–7285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coon BG, et al. The Lowe syndrome protein OCRL1 is involved in primary cilia assembly. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:1835–1847. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jayaraman D, et al. Microcephaly proteins Wdr62 and Aspm define a mother centriole complex regulating centriole biogenesis, apical complex, and cell fate. Neuron. 2016;92:813–828. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou Y, et al. Wdr62 is involved in female meiotic initiation via activating JNK signaling and associated with POI in humans. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bettencourt-Dias M, Hildebrandt F, Pellman D, Woods G, Godinho SA. Centrosomes and cilia in human disease. Trends Genet. 2011;27:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoerner C, Stearns T. Remembrance of cilia past. Cell. 2013;155:271–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kong S, et al. Dlic1 deficiency impairs ciliogenesis of photoreceptors by destabilizing dynein. Cell Res. 2013;23:835–850. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cambridge EL, et al. The AMP-activated protein kinase beta 1 subunit modulates erythrocyte integrity. Exp. Hematol. 2017;45:64–68.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Föller M, et al. Regulation of erythrocyte survival by AMP-activated protein kinase. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2009;23:1072–1080. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-121772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bujakowska KM, Liu Q, Pierce EA. Photoreceptor cilia and retinal ciliopathies. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017;9:a028274. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Skarnes WC, et al. A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function. Nature. 2011;474:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Percie du Sert N, et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLOS Biol. 2020;18:e3000411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moore BA, et al. Identification of genes required for eye development by high-throughput screening of mouse knockouts. Commun. Biol. 2018;1:236. doi: 10.1038/s42003-018-0226-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dickinson ME, et al. High-throughput discovery of novel developmental phenotypes. Nature. 2016;537:508–514. doi: 10.1038/nature19356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Uchino S, Bellomo R, Goldsmith D. The meaning of the blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio in acute kidney injury. Clin. Kidney J. 2012;5:187–191. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfs013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heberle H, Meirelles GV, da Silva FR, Telles GP, Minghim R. InteractiVenn: A web-based tool for the analysis of sets through Venn diagrams. BMC Bioinform. 2015;16:169. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0611-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gherman A, Davis EE, Katsanis N. The ciliary proteome database: An integrated community resource for the genetic and functional dissection of cilia. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:961–962. doi: 10.1038/ng0906-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Szklarczyk D, et al. STRING v11: Protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;47:D607–D613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Gorodkin J, Jensen LJ. Cytoscape StringApp: Network analysis and visualization of proteomics data. J. Proteome Res. 2019;18:623–632. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rappaport N, et al. MalaCards: An integrated compendium for diseases and their annotation. Database (Oxford) 2013;2013:bat018. doi: 10.1093/database/bat018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Materials Availability All mice generated are available from the IMPC. See impc.org for more details.

All raw data is available at impc.org, no original code was generated during the research.