Abstract

Aims

Aortic stenosis (AS) and cardiac amyloidosis (CA) are typical diseases of the elderly. Up to 16% of older adults with severe AS referred to transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) have a concomitant diagnosis of CA. CA‐AS population suffers from reduced functional capacity and worse prognosis than AS patients. As the prognostic impact of TAVR in patients with CA‐AS has been historically questioned and in light of recently published evidence, we aim to provide a comprehensive synthesis of the efficacy and safety of TAVR in CA‐AS patients.

Methods and results

We performed a systematic review and meta‐analysis of studies: (i) evaluating mortality with TAVR as compared with medical therapy in CA‐AS patients and (ii) reporting complications and clinical outcomes of TAVR in CA‐AS patients as compared with patients with AS alone. A total of seven observational studies were identified: four reported mortality with TAVR, and four reported complications and clinical outcomes after TAVR of patients with CA‐AS compared with AS alone patients. In patients with CA‐AS, the risk of mortality was lower with TAVR (n = 44) as compared with medical therapy (n = 36) [odds ratio (OR) 0.23, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.07–0.73, I 2 = 0%, P = 0.001, number needed to treat = 3]. The safety profile of TAVR seems to be similar in patients with CA‐AS (n = 75) as compared with those with AS alone (n = 536), with comparable risks of stroke, vascular complications, life‐threatening bleeding, acute kidney injury, and 30 day mortality, although CA‐AS was associated with a trend towards an increased risk of permanent pacemaker implantation (OR 1.76, 95% CI 0.91–4.09, I 2 = 0%, P = 0.085). CA is associated with a numerically higher rate of long‐term mortality and rehospitalizations following TAVR in patients with CA‐AS as compared with those with AS alone.

Conclusions

TAVR is an effective and safe procedure in CA‐AS patients, with a substantial survival benefit as compared with medical therapy, and a safety profile comparable with patients with AS alone except for a trend towards higher risk of permanent pacemaker implantation.

Keywords: Cardiac amyloidosis, Aortic stenosis, Transcatheter aortic valve replacement, Transthyretin amyloidosis, Light‐chain amyloidosis

Introduction

Amyloidosis is a systemic disease characterized by the extracellular accumulation of amyloid fibrils within organs, often also involving the heart, resulting in cardiac amyloidosis (CA). 1 The two most common types of CA are light‐chain amyloidosis (AL), related to the accumulation of immunoglobulin light chains secondary to haematologic malignancies, and transthyretin (TTR) amyloidosis, due to the accumulation of a mutant form of TTR or wild‐type TTR. 2 The latter form has a prevalence that increases with age, being reported in up to 25% of people older than 80 years of age. 3 Similarly, aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common degenerative valve disease worldwide and affects 3% of patients aged more than 75 years. 4 Despite this similar epidemiologic pattern, the awareness of the high frequency of concomitant CA and AS and their interplay gradually raised only in the last decade: up to 16% of patients referred to transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) have a concomitant diagnosis of CA, thus identifying CA‐AS as a frequent clinical entity. 5

Of note, CA‐AS patients have worse functional capacity and show a trend towards higher mortality than AS patients, if left untreated. 6 , 7 Thus, prognostic impact of aortic valve replacement in patients with CA‐AS has been historically questioned, 8 , 9 , 10 until recent evidence suggested a beneficial impact of TAVR as compared with medical therapy alone in CA‐AS patients. 7

In order to provide a comprehensive synthesis of the efficacy and safety of TAVR in CA‐AS patients, we performed a systematic review and meta‐analysis of studies evaluating mortality with TAVR as compared with medical therapy in CA‐AS patients and studies reporting complications and clinical outcomes of TAVR in CA‐AS patients as compared with patients with AS alone.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Three authors (F.C., G.P., and A.V.) independently searched PubMed for all studies published from inception to 14 March 2021 using combinations of the following search keywords: ‘amyloid’ or ‘amyloidosis’ and ‘aortic stenosis’ or ‘aortic valve’ or ‘aortic valve replacement’ or ‘aortic valve implantation’ or ‘aortic replacement’ or ‘aortic implantation’. Papers were initially screened by title and abstract content. In addition, we used backward snowballing (i.e. a review of references from identified articles and pertinent reviews) to identify any additional citations. Studies were considered eligible if they fulfilled one of these criteria: (i) studies reporting outcomes after TAVR in patients with severe AS and CA as compared with medical therapy; (ii) studies reporting outcomes and complication rates after TAVR in patients with AS and CA as compared with patients with AS alone. Case reports and studies not clearly reporting the outcomes were excluded from the analysis. Three investigators (F.C., G.P., and A.V.) independently extracted data on study design, measurements, patient characteristics, and outcomes, using a standardized data extraction form. Data extraction conflicts were discussed and resolved with the other main investigators (M.C. and G.G.S.). When extracting data regarding the outcomes of TAVR in patients with severe AS and CA as compared with medical therapy, patients with moderate AS were excluded from the analysis. Three authors (M.C., G.P., and A.V.) independently assessed the quality of studies and risk of bias according to the ROBINS‐I tool. 11 All included studies had appropriate ethical oversight and approval. Search strategy, study selection, data extraction, and data analysis were performed in accordance with the Cochrane Collaboration and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses guidelines. This study is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021245737).

Study outcomes

The primary endpoint was all‐cause death. Further endpoints extracted from the studies reporting outcomes and complication rates of TAVR in CA‐AS patients as compared with patients with AS alone were as follows: all‐cause death, permanent pacemaker implantation, stroke, vascular complications, acute kidney injury, more than mild aortic regurgitation, life‐threatening bleeding, and rehospitalizations.

Statistical analysis

Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using the DerSimonian and Laird random‐effects model, with the estimate of heterogeneity being taken from the Mantel–Haenszel method. The number of patients needed to treat to prevent one event was calculated from weighted estimates of pooled ORs from the random‐effects meta‐analytic model. The hypothesis of statistical heterogeneity was tested by means of the Cochran Q statistic and I 2 values. I 2 values of less than 25%, 50%, or more than 50% indicated low, moderate, or substantial heterogeneity, respectively. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 (two‐sided). The presence of publication bias was investigated by visual estimation with funnel plots. Sensitivity analyses with fixed‐effect models and with hazard ratio and 95% CI as effect estimates were performed to assess consistency with the main analysis. Meta‐regression analyses with a random‐effects model were performed to evaluate the presence of an interaction between each of the following potential effect modifiers and treatment (i.e. TAVR vs. medical therapy) in patients with CA‐AS for the primary endpoint: median follow‐up, overall prevalence of atrial fibrillation, low‐flow state, low‐flow low‐gradient AS, and paradoxical low‐flow low‐gradient AS. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata (Version 16; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

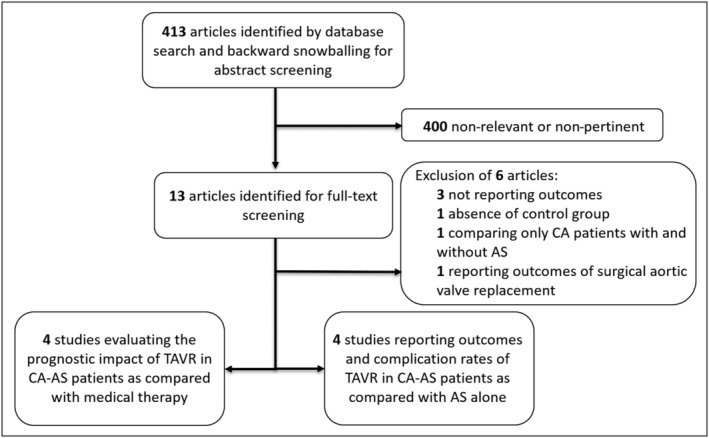

A total of seven observational studies were identified, four reporting mortality with TAVR, 6 , 7 , 12 , 13 and four reporting complications and clinical outcomes of CA‐AS compared with AS alone patients after TAVR. 6 , 10 , 14 , 15 One study 6 was included in both meta‐analyses. Figure 1 summarizes the study selection process.

Figure 1.

Flow‐chart of the study selection process. *One study 6 is employed in both meta‐analyses. AS, aortic stenosis; CA, cardiac amyloidosis; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

TAVR vs. medical therapy in CA‐AS patients

The key features of included studies and patients are presented in Table 1 . A total of 80 patients with CA‐AS, treated with either TAVR (n = 44) or medical therapy (n = 36), were analysed. 6 , 7 , 12 , 13

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of cohorts included in the meta‐analysis

| First author, year (Ref. #) | Galat et al., 2016 12 | Cavalcante et al., 2017 7 | Chacko et al., 2020 13 | Nitsche et al., 2021 6 , a | All studies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAVR | Medical therapy | TAVR | Medical therapy | TAVR | Medical therapy | TAVR | Medical therapy | TAVR | Medical therapy | |

| Number of patients | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 16 | 35 | 11 | 44 | 36 |

| Modality of CA diagnosis | EMB or DPD scintigraphy | CMR | EMB or DPD scintigraphy | DPD scintigraphy | — | |||||

| Age | 84 (79–84) | 88 (±6) | — | 85.4 (80.2–89.1), 86.6 (84.1–91.8) | — | |||||

| Ejection fraction | 52 (37–55) | 40 (29–52) | — | 55 (35.0–61.0), 51 (42.0–64.0) | — | |||||

| Follow‐up (months) | 10 (8–33) | 3 (2–7) | 32 (±18) b | 20.4 (15.6–31.2) | — | |||||

| Stroke volume index (mL/m2) | 25 (22–25) | 27.5 (19–33.5) | — | 33.2 (30.0–39.1), 35.8 (27.4–44.0) | — | |||||

| Low flow–low gradient | 25% | 62% | 50% | 25% | 35.2% | |||||

| Paradoxycal low flow–low gradient | 40% | 25% | — | 27% | 27.6% | |||||

| AVA (cm2) | 0.86 (0.81–0.9) | 0.6 (0.45–0.75) | — | 0.7 (0.6–0.8), 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | — | |||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 60% | 63% | — | 50% | 52.7% | |||||

AVA, aortic valve area; CA, cardiac amyloidosis; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; DPD, 99mtechnetium‐labelled 3,3‐diphosphono‐1,2‐propanodicarboxylic acid bone scintigraphy; EMB, endomyocardial biopsy; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Values are %, or median (interquartile range) or mean (standard deviation), where appropriate or as reported in the original studies.

Quantitative variables from Nitsche et al., 2021 are shown stratified according to the degree of DPD scintigraphy positivity (1 vs. 2/3), as reported in the original study.

Refers to the entire cohort of Chacko et al.

Bisphosphonate scintigraphy was the most common modality of diagnosis for CA, (n = 72). Cardiac magnetic resonance was the modality of choice only in one study, (n = 8). 7 All the included studies were observational in nature, and treatment allocation (TAVR vs. medical therapy) was left at the discretion of the treating physician.

The median age of included patients ranged from 84 to 88 years. Median left ventricular ejection fraction ranged from 40% to 55%. The median aortic valve area was reported to be between 0.6 and 0.86 cm2. Low‐flow low‐gradient AS was found in 12% to 62% of patients included, while paradoxical low‐flow low‐gradient AS was present in 25% to 40% of patients. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation ranged from 50% to 63%.

Patients were followed up for a median of 3 to 32 months after either diagnosis of CA or referral for TAVR.

All included patients with CA‐AS suffered from TTR‐CA, except for one patient who had AL‐CA and underwent TAVR. 6

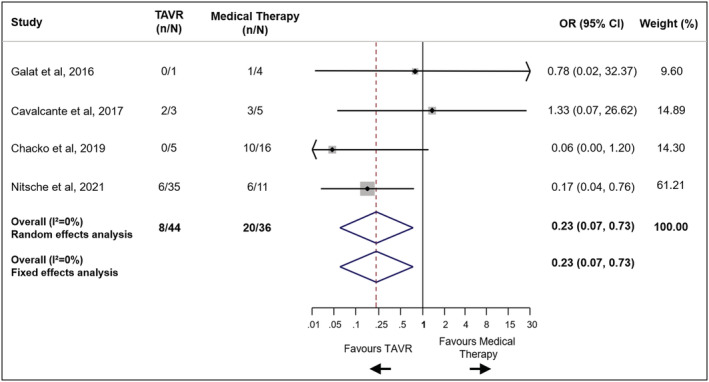

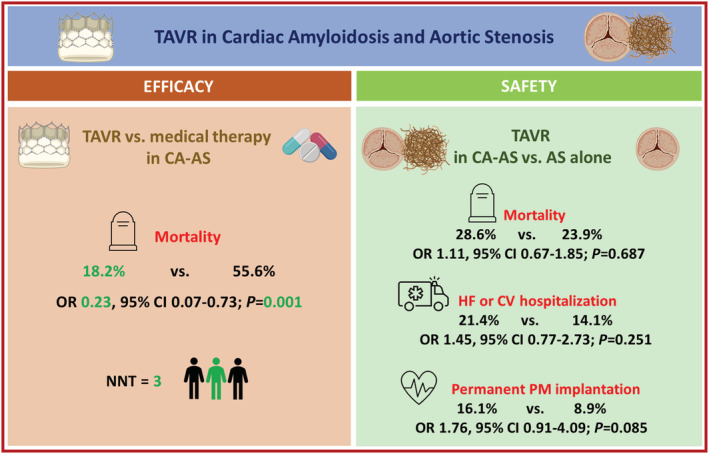

The risk of all‐cause mortality was lower in patients who underwent TAVR as compared with patients treated with medical therapy (OR 0.23, 95% CI 0.07–0.73, I 2 = 0%) without evidence of heterogeneity (Figures 2 and 3 ). The number needed to treat to prevent one death with TAVR was 3 patients. The treatment effect of TAVR on mortality in CA‐AS patients was consistent with fixed‐effect model (OR 0.23, 95% CI 0.07–0.73, I 2 = 0%) and with hazard ratio as effect estimate (HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.28–0.89, I 2 = 64%).

Figure 2.

Mortality in patients with severe aortic stenosis and cardiac amyloidosis undergoing TAVR vs. medical therapy. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Figure 3.

Clinical outcomes in CA‐AS according to treatment strategy and in AS with or without CA after TAVR. AS, aortic stenosis; CA, cardiac amyloidosis; CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; NNT number needed to treat; OR, odds ratio; PM, pacemaker; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Meta‐regression analyses did not show any significant interaction between each of the following potential effect modifiers and treatment effect for the primary endpoint: overall prevalence of atrial fibrillation, low‐flow state, low‐flow low‐gradient AS and paradoxical low‐flow low‐gradient AS and median follow‐up (Supporting Information, Figures S1–S5). Funnel plot distribution of the primary endpoint indicated the absence of publication bias and small study effect (Figure S6).

The overall risk of bias was low for one study 13 and moderate for the other three studies 6 , 7 , 12 (Table S2).

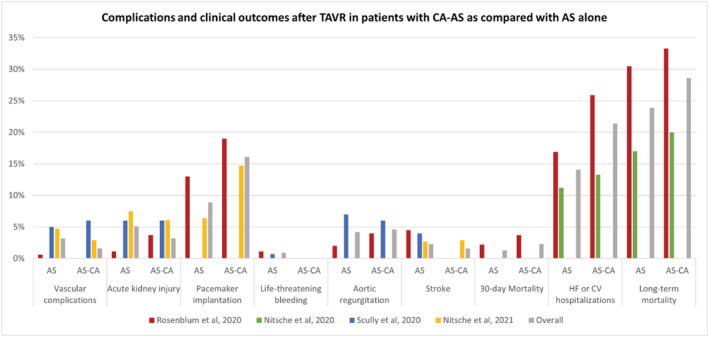

TAVR in patients with CA‐AS or AS alone

The main features of included studies and populations are presented in Table 2 . A total of 536 patients with AS treated with TAVR were compared with 75 patients with CA‐AS treated with TAVR. Thirty‐day and long‐term mortality and procedural complications are shown in Figures 3 and 4 and in Table S1 . Patients from Scully et al. 10 and Nitsche et al. 2020 15 are included in Nitsche et al. 2021, 6 and were counted only for the endpoints not reported from the latter pooled cohort. Procedural complications were defined using the Valve Academic Research Consortium‐2 16 criteria in three studies. 6 , 10 , 14

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of cohorts included in the descriptive meta‐analysis evaluating outcomes and complications of TAVR in CA‐AS patients as compared with AS alone

| First author, year (Ref. #) | Rosenblum et al., 2020 14 | Nitsche et al., 2020 15 , c | Scully et al., 2020 10 , a , c | Nitsche et al., 2021 6 , a , c | All studies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | CA‐AS | AS | CA‐AS | AS | CA‐AS | AS | CA‐AS b | AS | CA‐AS | |

| Number of patients | 177 | 27 | 175 | 16 | 174 | 26 | 359 | 48 | — | — |

| Age (years) | 82 ± 10 | 86 ± 5 | 82 (77–85) | 84 (81–89) | 85 ± 5 | 88 ± 5 | 84 (72–88) | 85.4 (80.2–89.1), 86.6 (84.1–91.8) | 83.3 | 86 |

| STS score | 6.5 ± 3.5 | 7 ± 4.6 | 3.5 (2.5–5.1) | 4.7 (3.5–5.7) | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Euroscore II | — | — | 4.2 (3.9–4.7) | 4.5 (4.0–4.6) | — | — | 4.2 (3.7–5.1) | 4.1 (3.6–4.6), 4.5 (3.9–5.2) | — | — |

| Diagnosis | DPD scintigraphy | Multimodality | DPD scintigraphy | DPD scintigraphy | — | |||||

| Male sex (%) | 60 | 93 | 48.3 | 62.5 | 48 | 62 | 48.2 | 60 | 52 | 72 |

| LVEF (%) | 55 ± 15 | 48 ± 17 | 62 (54–70) | 62 (44–70) | 54 ± 11 | 54 ± 14 | 58 (44–64) | 55 (35.0–61.0), 51 (42.0–64.0) | — | — |

| SVi (mL/m2) | 35 ± 10 | 31 ± 11 | 47 (29–64) | 27 (22–34) | 38 ± 11 | 34 ± 10 | 40 (31–48) | 33.2 (30.0–39.1), 35.8 (27.4–44.0) | — | — |

| LF‐LG (%) | 14 | 30 | 9.2 | 12.5 | 9 | 12 | 16.4 | 25 | 15.6 | 26.6 |

| Paradoxical LF‐LG (%) | 12 | 7 | 15.5 | 43.8 | 15 | 19 | 16.4 | 27 | 14.9 | 20 |

| AVA (cm2) | 0.76 ± 0.23 | 0.8 ± 0.15 | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 0.6 (0.5–0.9) | 0.73 ± 0.22 | 0.74 ± 0.23 | 0,7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8), 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | — | — |

| Hs‐Tn (ng/L) | 20 (10–100) hs‐TnI | 120 (80–350) hs‐TnI | 28 (20–49) hs‐TnT | 47 (24–72) hs‐TnT | 21 (14–34) hs‐TnT | 41 (25–84) hs‐TnT | 24 (15–39) hs‐TnT | 25 (23–32), 49 (33–87) | — | — |

| NT‐proBNP (pg/mL) | 352 (BNP) | 522 (BNP) | 1839 (727–5664) | 3634 (1241–6323) | 1254 (598–2769) | 3702 (1286–5626) | 1606 (640–3843) | 1632 (933–3619), 4855 (1412–7494) | — | — |

Values are %, or median (interquartile range) or mean (standard deviation), where appropriate or as reported in the original studies.

AS, aortic stenosis; AVA, aortic valve area; CA, cardiac amyloidosis; DPD, 99mtechnetium‐labelled 3,3‐diphosphono‐1,2‐propanodicarboxylic acid bone scintigraphy; hs‐Tn, high‐sensitivity troponin; LF‐LG, low‐flow low‐gradient; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; SVi, stroke volume index; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Baseline characteristics concern to patients with severe AS: only a percentage of patients in the study underwent TAVR.

Quantitative variables are shown stratified according to the degree of DPD scintigraphy positivity (1 vs. 2/3), as reported in the original study.

As specified elsewhere, patients from Scully et al. 2020 and Nitsche et al. 2020 are included in Nitsche et al. 2021.

Figure 4.

Complications and periprocedural outcomes after TAVR in patients with AS and CA as compared with AS alone (patients from Scully et al. 2020 and Nitsche et al. 2020 are included in Nitsche et al. 2021). AS, aortic stenosis; CA, cardiac amyloidosis; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

The risk of 30 day mortality did not differ between the two groups (2.4% and 1.3% in patients with CA‐AS and AS alone, respectively; OR 1.66 95% CI 0.18–15.47). Long‐term mortality was 28.6% in patients with CA‐AS and 23.9% in those with AS alone, resulting in similar risk in the two groups (OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.67–1.85, P = 0.687). A higher incidence of hospitalizations for heart failure during the follow‐up period emerged in patients with CA‐AS (26% vs. 19%) 14 ; while a substantially comparable incidence of cardiovascular hospitalizations after TAVR in the two groups was reported (12% vs. 11%). 15 The difference between the two groups in terms of cardiovascular rehospitalizations was not statistically significant (21.4% vs. 14.1%; OR 1.45, 95% CI 0.77–2.73). After TAVR, a non‐significant trend for higher risk of need for permanent pacemaker implantation in patients with CA‐AS than in AS alone patients was observed (16.1 vs. 8.9%, CA‐AS and AS alone, respectively; OR 1.76, 95% CI 0.91–4.09; P = 0.085).

Stroke occurred in less than 4% of patients, without significant differences among patients with CA‐AS or with AS alone (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.18–5.65).

Similarly, no differences were noted in patients with CA‐AS and with AS alone in terms of vascular complications (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.15–4.91), acute kidney injury (OR 1.16 95% CI 0.31–4.44), and life‐threatening bleeding (OR 1.81, 95% CI 0.19–16.78), as well as for the risk of more than mild aortic regurgitation (OR 1.22, 95% CI 0.26–5.70).

Discussion

The main findings of this systematic review and meta‐analysis can be summarized as follows:

TAVR is associated with improvement in survival in patients with severe symptomatic CA‐AS as compared with medical therapy;

CA appears not to be associated with an increased risk of periprocedural complications in patients undergoing TAVR, except for a numerically increased risk of permanent pacemaker implantation.

the risk of long‐term mortality and rehospitalizations following TAVR in patients with CA‐AS resulted only numerically higher than in patients with AS alone.

TAVR has completely changed the management and prognosis of patients affected by symptomatic severe AS. Indeed, in the last decade, TAVR has shown to confer a clear benefit over medical therapy alone in inoperable and high‐surgical‐risk patients. 17 , 18 , 19 According to the results from the latest trials, the indication for TAVR has expanded to intermediate and low surgical risk patients. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 Nevertheless, trials population often does not reflect real‐world population.

In recent years, more attention has been given to patients with CA, in particular to TTR‐CA, due to the improvement of diagnostic tools and to the improved knowledge of the disease. 24 , 25 Few trials have produced encouraging results for the treatment of this condition, which previously was limited to supportive care. 26 The prevalence of CA increases with age, and, according to recent observational studies, up to 16% of elderly affected by AS and referred for TAVR have a concomitant diagnosis of CA. 5 The identification of CA patients in a relevant percentage of patients with severe AS produced great interest in the diagnostic field. Some clinical, electrocardiographic, and echocardiographic features have been shown to be specific for CA pattern among AS patients. 27 , 28 However, there is still paucity of data about the optimal therapeutic management for this dual pathology.

Despite new amyloid‐directed therapies emerged for CA in patients without severe AS and resulting in a clear mortality benefit, 26 no randomized evidence supports the use of aortic valve replacement in patients with CA‐AS, so far. These patients are as old as those with AS alone usually referred to TAVR, but are encumbered by the haemodynamic impact of a progressive infiltrative cardiomyopathy, and increased burden of comorbidities, frailty, and surgical risk. 6 The risk of futility of correcting aortic valve stenosis in case of CA‐AS initially emerged from observational studies, while limited by small sample size. 8 , 9 , 12

In our analysis, we evaluated the role of TAVR compared with standard supportive care in patients with CA‐AS. Our analysis shows a clear survival benefit of patients undergoing TAVR and demonstrates that the hemodynamic benefit of TAVR persists even in patients with CA‐AS. CA generates a restrictive cardiomyopathy with elevated filling pressures and low stroke volume, and the presence of concomitant severe AS results in increased afterload and subsequent synergistic detrimental effect on filling pressures and decompensation risk. 2 Guideline‐directed medical therapy for heart failure is often poorly tolerated in these patients, in light of the increased risk of hypotension or atrioventricular blocks. As a matter of fact, supportive treatment in CA‐AS patients merely consists only in diuretic therapy to minimize the risk of congestive decompensations. In this setting, TAVR could remove the valvular barrage and restore normal afterload conditions with an immediate haemodynamic relief and, potentially, a long‐term survival advantage. In our analysis, the survival benefit emerged despite the inclusion of only four studies with a relatively limited sample size. 6 , 7 , 12 , 13

In patients with CA‐AS, the pathological deposition of amyloid fibrils endures following TAVR, with a progression of infiltrative cardiomyopathy. 8 To evaluate the prognostic impact of CA following TAVR, we sought evidence on overall mortality and hospitalizations for heart failure in patients with CA‐AS undergoing TAVR compared with those with AS alone. The rate of mortality after TAVR in patients with CA‐AS and AS alone is in line with the results from the largest pivotal trials on high and intermediate‐surgical‐risk patients, 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 while limited data can be extrapolated from previous studies as regard heart failure hospitalization after TAVR in these patients. The rate of hospitalization for HF after TAVR has been reported to be higher in patients with CA‐AS than in those with AS alone, 14 likely due to the intrinsic features of CA. Indeed, as mentioned before, the clinical history of CA is characterized by progressive heart failure, caused by amyloid deposition with myocardial stiffening and toxicity. 2 Whether these patients could benefit from amyloid‐directed therapies following TAVR is unknown yet, and new evidence are warranted.

As it relates to the need for permanent pacemaker implantation, we found a numerically higher risk in patients with CA‐AS than in those with AS alone, but this comparison is based only on two studies and a small sample size (sample size: 536 patients; number of events: 52). 6 , 14 This finding, however, is in line with the pathophysiology of this infiltrative disorder: CA has a direct impact on conduction system degeneration, increasing the risk of atrioventricular blocks with subsequent need for permanent pacemaker implantation. Hence, it is not surprising that the concomitant presence of CA increases this risk in patients undergoing TAVR. Nevertheless, our findings in CA‐AS patients are consistent to the data from pivotal trials on patients with lone AS after TAVR. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 Whether the use of prosthesis with lower radial forces and supra‐annular position, or the adoption of new implantation techniques (e.g. cusp overlap technique) might be translated in lower risk for permanent pacemaker implantation is still unknown and deserves further investigation.

Comorbidities, an increased frailty, and the cardiomyopathy itself in patients with CA‐AS undergoing TAVR could theoretically lead to a higher risk of procedural complications than patients with AS alone. Comparing the rate of procedural complications and short‐term adverse events among patients with CA‐AS vs. AS alone undergoing TAVR did not result in any differences in the risks of stroke, acute kidney injury, vascular complications, life‐threatening bleeding, or 30 day mortality. These results suggest that CA‐AS patients could be referred for TAVR without additional safety concerns. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21

Our findings have particular relevance in consideration of the future outlook of the management of CA. 24 New medical therapies are available for CA patients, irrespective of the presence of AS, and others will be in the upcoming years, resulting in the need to treat patients with a longer life expectancy. Furthermore, despite most of CA‐AS patients suffer from wild‐type TTR‐CA, the hereditary form will also be diagnosed more easily in the future, possibly enlarging the cohort of younger patients affected by severe AS requiring valve replacement. Our findings indicate that TAVR may be considered as a safe and effective treatment option also for these patients.

Limitations

The present study should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, this is a study‐level meta‐analysis that provides only average treatment effects. The lack of patient‐level data prevents us from assessing the effect of baseline clinical characteristics on TAVR prognostic impact. However, we performed meta‐regression analyses with available data to unveil any significant interaction between some potential effect modifiers and effect estimates of TAVR in CA‐AS patients. Moreover, the sample size of pooled studies is relatively small, resulting in effect estimates with wide CIs that limit our ability to provide precise risk estimates and increasing the risk of type II error. Then, the prognostic impact of TAVR in patients with CA‐AS (number of patients needed to treat with TAVR to prevent a death: 3) may be less significant than reported in the present analysis. These limitations notwithstanding, the beneficial treatment effects of TAVR emerged at sensitivity analyses. Finally, complications and periprocedural outcomes after TAVR were not consistently and homogeneously assessed by all the included studies, and outcomes were not defined according to standardized and validated definition in all studies.

Conclusions

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement has been considered futile by preliminary studies on CA patients with severe AS. Our analysis rejects this hypothesis of futility, showing that TAVR is associated with a strong survival benefit in CA‐AS patients as compared with medical therapy. Moreover, our findings indicate that CA‐AS patients may undergo TAVR with a procedural risk substantially comparable with patients with AS alone, except for a trend towards a higher incidence of permanent pacemaker implantation. Large‐scale randomized studies are still needed to fully elucidate the impact of TAVR in CA‐AS patients.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Stefanini has received a research grant (to the institution) from Boston Scientific and speakers fees from Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular and Pfizer/BMS. All other authors report no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Funding

This work is supported by a research grant from the Italian Ministry of Education (PRIN 2017N8K7S2 to G.G.S).

Supporting information

Table S1. Complications and outcomes after TAVR, stratified by presence of ATTR‐CA.

Table S2. PRISMA checklist.

Table S3. Risk of Bias assessment with the ROBINS‐I tool.

Figure S1. Meta‐regression analysis: impact on mortality of low‐flow state.

Figure S2. Meta‐regression analysis: impact on mortality of low‐flow low‐gradient.

Figure S3. Meta‐regression analysis: impact on mortality of median follow‐up.

Figure S4. Meta‐regression analysis: impact on mortality of atrial fibrillation prevalence.

Figure S5. Meta‐regression analysis: impact on mortality of paradoxical low‐flow low‐gradient.

Figure S6. Funnel plot for primary outcome.

Cannata, F. , Chiarito, M. , Pinto, G. , Villaschi, A. , Sanz‐Sánchez, J. , Fazzari, F. , Regazzoli, D. , Mangieri, A. , Bragato, R. M. , Colombo, A. , Reimers, B. , Condorelli, G. , and Stefanini, G. G. (2022) Transcatheter aortic valve replacement in aortic stenosis and cardiac amyloidosis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. ESC Heart Failure, 9: 3188–3197. 10.1002/ehf2.13876.

Francesco Cannata, Mauro Chiarito, and Giuseppe Pinto contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1. Wechalekar AD, Gillmore JD, Hawkins PN. Systemic amyloidosis. Lancet 2016; 387: 2641–2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ruberg FL, Grogan M, Hanna M, Kelly JW, Maurer MS. Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy: JACC state‐of‐the‐art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 73: 2872–2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tanskanen M, Peuralinna T, Polvikoski T, Notkola IL, Sulkava R, Hardy J, Singleton A, Kiuru‐Enari S, Paetau A, Tienari PJ, Myllykangas L. Senile systemic amyloidosis affects 25% of the very aged and associates with genetic variation in alpha2‐macroglobulin and tau: a population based autopsy study. Ann Med 2008; 40: 232–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez‐Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population‐based study. Lancet 2006; 368: 1005–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Castaño A, Narotsky DL, Hamid N, Khalique OK, Morgenstern R, DeLuca A, Rubin J, Chiuzan C, Nazif T, Vahl T, George I, Kodali S, Leon MB, Hahn R, Bokhari S, Maurer MS. Unveiling transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis and its predictors among elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Eur Heart J 2017; 38: 2879–2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nitsche C, Scully PR, Patel KP, Kammerlander AA, Koschutnik M, Dona C, Wollenweber T, Ahmed N, Thornton GD, Kelion AD, Sabharwal N, Newton JD, Ozkor M, Kennon S, Mullen M, Lloyd G, Fontana M, Hawkins PN, Pugliese F, Menezes LJ, Moon JC, Mascherbauer J, Treibel TA. Prevalence and outcomes of concomitant aortic stenosis and cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021; 77: 128–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cavalcante JL, Rijal S, Abdelkarim I, Althouse AD, Sharbaugh MS, Fridman Y, Soman P, Forman DE, Schindler JT, Gleason TG, Lee JS, Schelbert EB. Cardiac amyloidosis is prevalent in older patients with aortic stenosis and carries worse prognosis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2017; 19: 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ternacle J, Krapf L, Mohty D, Magne J, Nguyen A, Galat A, Gallet R, Teiger E, Côté N, Clavel MA, Tournoux F, Pibarot P, Damy T. Aortic stenosis and cardiac amyloidosis: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 74: 2638–2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Treibel TA, Fontana M, Gilbertson JA, Castelletti S, White SK, Scully PR, Roberts N, Hutt DF, Rowczenio DM, Whelan CJ, Ashworth MA, Gillmore JD, Hawkins PN, Moon JC. Occult transthyretin cardiac amyloid in severe calcific aortic stenosis: prevalence and prognosis in patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 9: e005066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scully PR, Patel KP, Treibel TA, Thornton GD, Hughes RK, Chadalavada S, Katsoulis M, Hartman N, Fontana M, Pugliese F, Sabharwal N, Newton JD, Kelion A, Ozkor M, Kennon S, Mullen M, Lloyd G, Menezes LJ, Hawkins PN, Moon JC. Prevalence and outcome of dual aortic stenosis and cardiac amyloid pathology in patients referred for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur Heart J 2020; 41: 2759–2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, Carpenter JR. ROBINS‐I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in nonrandomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016; 355: i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Galat A, Guellich A, Bodez D, Slama M, Dijos M, Zeitoun DM, Milleron O, Attias D, Dubois‐Randé JL, Mohty D, Audureau E, Teiger E, Rosso J, Monin JL, Damy T. Aortic stenosis and transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: the chicken or the egg? Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 3525–3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chacko L, Martone R, Bandera F, Lane T, Martinez‐Naharro A, Boldrini M, Rezk T, Whelan C, Quarta C, Rowczenio D, Gilbertson JA. Echocardiographic phenotype and prognosis in transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Eur Heart J 2020; 0: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rosenblum H, Masri A, Narotsky DL, Goldsmith J, Hamid N, Hahn RT, Kodali S, Vahl T, Nazif T, Khalique OK, Bokhari S, Soman P, Cavalcante JL, Maurer MS, Castaño A. Unveiling outcomes in coexisting severe aortic stenosis and transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Eur J Heart Fail 2021; 23: 250–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nitsche C, Aschauer S, Kammerlander AA, Schneider M, Poschner T, Duca F, Binder C, Koschutnik M, Stiftinger J, Goliasch G, Siller‐Matula J, Winter MP, Anvari‐Pirsch A, Andreas M, Geppert A, Beitzke D, Loewe C, Hacker M, Agis H, Kain R, Lang I, Bonderman D, Hengstenberg C, Mascherbauer J. Light‐chain and transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis in severe aortic stenosis: prevalence, screening possibilities, and outcome. Eur J Heart Fail 2020; 22: 1852–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Généreux P, Piazza N, van Mieghem NM, Blackstone EH, Brott TG, Cohen DJ, Cutlip DE, van Es GA, Hahn RT, Kirtane AJ, Krucoff MW, Kodali S, Mack MJ, Mehran R, Rodés‐Cabau J, Vranckx P, Webb JG, Windecker S, Serruys PW, Leon MB. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the valve academic research consortium‐2 consensus document. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2403–2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR, Brown DL, Block PC, Guyton RA, Pichard AD, Bavaria JE, Herrmann HC, Douglas PS, Petersen JL, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Wang D, Pocock S. Transcatheter aortic‐valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 1597–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR, Williams M, Dewey T, Kapadia S, Babaliaros V, Thourani VH, Corso P, Pichard AD, Bavaria JE, Herrmann HC, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Wang D, Pocock SJ. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic‐valve replacement in high‐risk patients. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 2187–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Popma JJ, Adams DH, Reardon MJ, Yakubov SJ, Kleiman NS, Heimansohn D, Hermiller J Jr, Hughes GC, Harrison JK, Coselli J, Diez J, Kafi A, Schreiber T, Gleason TG, Conte J, Buchbinder M, Deeb GM, Carabello B, Serruys PW, Chenoweth S, Oh JK, CoreValve United States Clinical Investigators . Transcatheter aortic valve replacement using a self‐expanding bioprosthesis in patients with severe aortic stenosis at extreme risk for surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63: 1972–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ, Kleiman NS, Søndergaard L, Mumtaz M, Adams DH, Deeb GM, Maini B, Gada H, Chetcuti S. Surgical or transcatheter aortic‐valve replacement in intermediate‐risk patients. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 1321–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, Makkar RR, Svensson LG, Kodali SK, Thourani VH, Tuzcu EM, Miller DC, Herrmann HC, Doshi D, Cohen DJ, Pichard AD, Kapadia S, Dewey T, Babaliaros V, Szeto WY, Williams MR, Kereiakes D, Zajarias A, Greason KL, Whisenant BK, Hodson RW, Moses JW, Trento A, Brown DL, Fearon WF, Pibarot P, Hahn RT, Jaber WA, Anderson WN, Alu MC, Webb JG. Transcatheter or surgical aortic‐valve replacement in intermediate‐risk patients. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 1609–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, Mumtaz M, Gada H, O'Hair D, Bajwa T, Heiser JC, Merhi W, Kleiman NS, Askew J, Sorajja P, Rovin J, Chetcuti SJ, Adams DH, Teirstein PS, Zorn GL 3rd, Forrest JK, Tchétché D, Resar J, Walton A, Piazza N, Ramlawi B, Robinson N, Petrossian G, Gleason TG, Oh JK, Boulware MJ, Qiao H, Mugglin AS, Reardon MJ, Evolut Low Risk Trial Investigators . Transcatheter aortic‐valve replacement with a self‐expanding valve in low‐risk patients. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 1706–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, Makkar R, Kodali SK, Russo M, Kapadia SR, Malaisrie SC, Cohen DJ, Pibarot P, Leipsic J, Hahn RT, Blanke P, Williams MR, McCabe JM, Brown DL, Babaliaros V, Goldman S, Szeto WY, Genereux P, Pershad A, Pocock SJ, Alu MC, Webb JG, Smith CR. Transcatheter aortic‐valve replacement with a balloon‐expandable valve in low‐risk patients. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 1695–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Garcia‐Pavia P, Rapezzi C, Adler Y, Arad M, Basso C, Brucato A, Burazor I, Caforio ALP, Damy T, Eriksson U, Fontana M, Gillmore JD, Gonzalez‐Lopez E, Grogan M, Heymans S, Imazio M, Kindermann I, Kristen AV, Maurer MS, Merlini G, Pantazis A, Pankuweit S, Rigopoulos AG, Linhart A. Diagnosis and treatment of cardiac amyloidosis: a position statement of the ESC working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J 2021; 42: ehab072–ehab1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gillmore JD, Maurer MS, Falk RH, Merlini G, Damy T, Dispenzieri A, Wechalekar AD, Berk JL, Quarta CC, Grogan M, Lachmann HJ, Bokhari S, Castano A, Dorbala S, Johnson GB, Glaudemans AWJM, Rezk T, Fontana M, Palladini G, Milani P, Guidalotti PL, Flatman K, Lane T, Vonberg FW, Whelan CJ, Moon JC, Ruberg FL, Miller EJ, Hutt DF, Hazenberg BP, Rapezzi C, Hawkins PN. Nonbiopsy diagnosis of cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Circulation 2016; 133: 2404–2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maurer MS, Schwartz JH, Gundapaneni B. Tafamidis treatment for patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 1007–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. González‐López E, Gagliardi C, Dominguez F, Quarta CC, de Haro‐del Moral FJ, Milandri A, Salas C, Cinelli M, Cobo‐Marcos M, Lorenzini M, Lara‐Pezzi E, Foffi S, Alonso‐Pulpon L, Rapezzi C, Garcia‐Pavia P. Clinical characteristics of wild‐type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: disproving myths. Eur Heart J 2017; 38: 1895–1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Longhi S, Lorenzini M, Gagliardi C, Milandri A, Marzocchi A, Marrozzini C, Saia F, Ortolani P, Biagini E, Guidalotti PL, Leone O, Rapezzi C. Coexistence of degenerative aortic stenosis and wild‐type transthyretin‐related cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol Img 2016; 9: 325–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Complications and outcomes after TAVR, stratified by presence of ATTR‐CA.

Table S2. PRISMA checklist.

Table S3. Risk of Bias assessment with the ROBINS‐I tool.

Figure S1. Meta‐regression analysis: impact on mortality of low‐flow state.

Figure S2. Meta‐regression analysis: impact on mortality of low‐flow low‐gradient.

Figure S3. Meta‐regression analysis: impact on mortality of median follow‐up.

Figure S4. Meta‐regression analysis: impact on mortality of atrial fibrillation prevalence.

Figure S5. Meta‐regression analysis: impact on mortality of paradoxical low‐flow low‐gradient.

Figure S6. Funnel plot for primary outcome.